Efectos diferenciales de la estimulación cognitiva computarizada y las actividades de ocio estimulantes sobre el estado de ánimo y la cognición global en adultos con deterioro cognitivo subjetivo y leve: Ensayo controlado aleatorizado

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.23938/ASSN.1136Palabras clave:

Deterioro Cognitivo Leve, Quejas Subjetivas de Memoria, Estimulación Cognitiva Computerizada, Actividades de Ocio Estimulantes, Atención PrimariaResumen

Fundamento. El deterioro cognitivo leve (DCL) se caracteriza por deterioro cognitivo subjetivo y objetivo con funcionamiento diario relativamente preservado, mientras que el deterioro cognitivo subjetivo (DCS) implica percepción de deterioro cognitivo sin déficits medibles. Este estudio evalúa los efectos de un programa personalizado de estimulación cognitiva computarizada frente a actividades de ocio estimulantes en adultos con DCL y DCS.

Métodos. Ensayo controlado aleatorizado simple ciego realizado en Atención Primaria con participantes de ≥50 años, con DCL o DCS, asignados aleatoriamente a dos grupos de intervención (GI1, GI2) y a un grupo control (GC). El GI1 realizó estimulación cognitiva computarizada personalizada 30 minutos/día, 5 días/semana, durante 8 semanas. El GI2 participó en 2-5 actividades de ocio estimulantes/semana durante el mismo periodo. El resultado principal fue la cognición global y los secundarios memoria, fluidez verbal, funcionamiento diario y estado de ánimo.

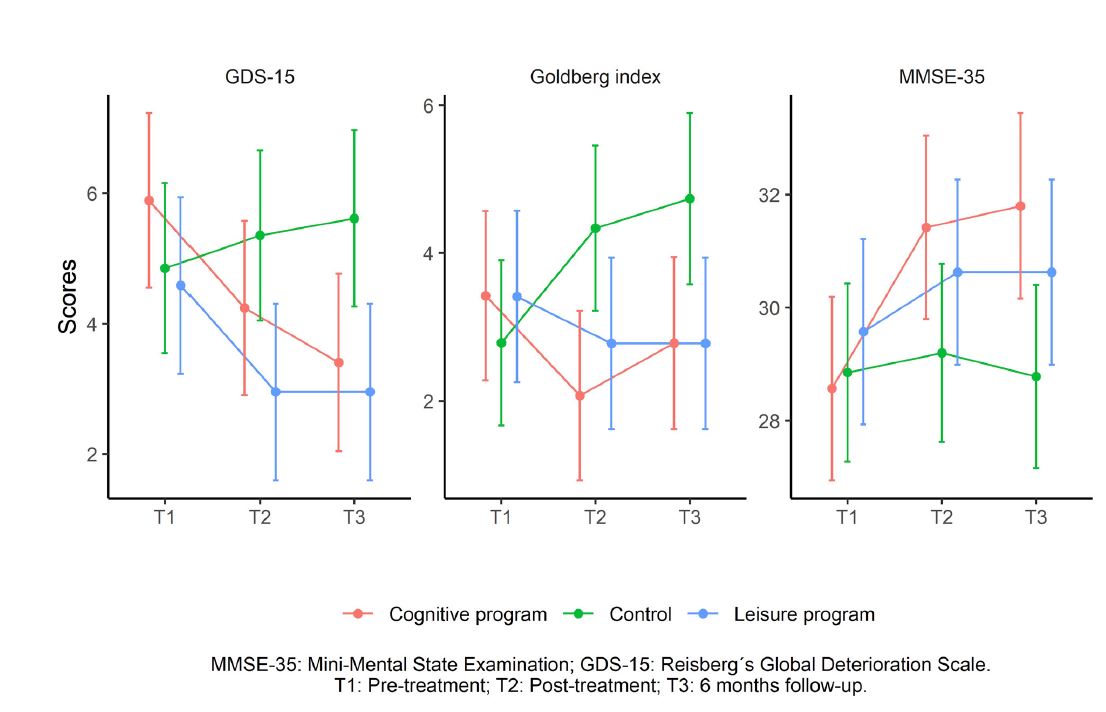

Resultados. Se reclutaron 59 participantes, 15 con DCL. Frente al GC, el GI1 redujo más la ansiedad post-intervención (2,074; IC95%: 0,927-3,222 vs. 4,338; IC95%: 3.22-5.456) y los síntomas depresivos a los 6 meses (3,407; IC95%: 2,047-4,767 vs. 5,615; IC95%: 4,262-6,968), mientras que el GI2 mejoró la cognición global tanto post-intervención (29,2; IC95%: 27,625-30.776) como a los 6 meses (28,782; IC95%: 27,163-30,402) respecto del GC (30,626; IC95%: 28,987-32,265).

Conclusión. La estimulación cognitiva computarizada personalizada redujo los síntomas ansiosos y depresivos, mientras que las actividades de ocio estimulantes mejoraron la cognición global en adultos con DCS y DCL no institucionalizados, sugiriendo beneficios complementarios de ambos enfoques.

Descargas

Citas

1. MITCHELL E, WALKER R. Global ageing: Successes, challenges and opportunities. Br J Hosp Med 2020; 81 (2): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2019.03772

2. Jessen F, Amariglio RE, Buckley RF, van der Flier WM, Han Y, Molinuevo JL et al. The characterisation of subjective cognitive decline. Lancet Neurol 2020; 19(3): 271-278. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30368-0

3. BRADFIELD NI. Mild Cognitive Impairment: Diagnosis and Subtypes. Clin EEG Neurosci 2023; 54(1): 4-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/15500594211042708

4. WINBLAD B, PALMER K, KIVIPELTO M, JELIC V, FRATIGLIONI L, WAHLUND LO et al. Mild cognitive impairment - Beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med 2004; 256 (3): 240-246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x

5. ZHOU Y, HAN W, YAO X, XUE JJ, LI Z, LI Y. Developing a machine learning model for detecting depression, anxiety, and apathy in older adults with mild cognitive impairment using speech and facial expressions: A cross-sectional observational study. Int J Nurs Stud 2023; 146: 104562.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2023.104562

6. GUO Y, PAI M, XUE B, LU W. Bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and mild cognitive impairment over 20 years: Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study in the United States. J Affect Disord 2023; 338: 449-458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.06.046

7. ROSTAMZADEH A, BOHR L, WAGNER M, BAETHGE C, JESSEN F. Progression of Subjective Cognitive Decline to MCI or Dementia in Relation to Biomarkers for Alzheimer Disease: A Meta-analysis. Neurology 2022; 99 (17): E1866-E1874. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000201072

8. JESSEN F, AMARIGLIO RE, VAN BOXTEL M, BRETELER M, CECCALDI M, CHÉTELAT G et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement 2014; 10 (6): 844-852. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000201072

9. PINYOPORNPANISH K, BUAWANGPONG N, SOONTORNPUN A, THAIKLA K, PATEEKHUM C, NANTSUPAWAT N et al. A household survey of the prevalence of subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment among urban community-dwelling adults aged 30 to 65. Sci Rep 2024; 14: 7783. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58150-3

10. HILL NL, MOGLE J, WION R, MUNOZ E, DEPASQUALE N, YEVCHAK AM et al. Subjective cognitive impairment and affective symptoms: A systematic review. Gerontologist 2016; 56 (6): e109-127. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw091

11. DESAI R, WHITFIELD T, SAID G, JOHN A, SAUNDERS R, MARCHANT NL et al. Affective symptoms and risk of progression to mild cognitive impairment or dementia in subjective cognitive decline: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev Internet 2021; 71: 101419. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2021.101419

12. SILVA R, BOBROWICZ-CAMPOS E, SANTOS-COSTA P, CRUZ AR, APÓSTOLO J. A home-based individual cognitive stimulation program for older adults with cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. Front Psychol 2021; 12: 1-13.

13. WOODS B, RAI HK, ELLIOTT E, AGUIRRE E, ORRELL M, SPECTOR A. Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2023; 2023 (1): CD005562. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005562.pub3

14. KURZ A. Cognitive stimulation, training, and rehabilitation. In: Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience: Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2019; 21: 35-42. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2019.21.1/akurz

15. DJABELKHIR-JEMMI L, WU YH, BOUBAYA M, MARLATS F, LEWIS M, VIDAL JS et al. Differential effects of a computerized cognitive stimulation program on older adults with mild cognitive impairment according to the severity of white matter hyperintensities. Clin Interv Aging 2018; 13: 1543-1554. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S152225

16. WANG HX, JIN Y, HENDRIE HC, LIANG C, YANG L, CHENG Y et al. Late life leisure activities and risk of cognitive decline. Journals Gerontol - Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013; 68(2): 205-213. http://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gls153

17. SU S, SHI L, ZHENG Y, SUN Y, HUANG X, ZHANG A et al. Leisure Activities and the Risk of Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Neurology 2022; 99(15): E1651-E1663. http://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000200929

18. CORBO I, MARSELLI G, DI CIERO V, CASAGRANDE M. The protective role of cognitive reserve: an empirical study in mild cognitive impairment. BMC Psychol 2024; 12(1): 334. http://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01831-5

19. CHUNG S, KIM M, AUH EY, PARK NS. Who’s global age-friendly cities guide: Its implications of a discussion on social exclusion among older adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(15): 8027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158027

20. GÓMEZ-SORIA I, OLIVÁN BLAZQUEZ B, AGUILAR-LATORRE A, CUENCA-ZALDÍVAR JN, MAGALLÓN BOTAYA, RM, CALATAYUD E. Effects of a personalised, adapted computerised cognitive stimulation programme versus stimulating leisure activities in younger and older adults with mild or subjective cognitive impairment. Protocol for a randomised controlled trial. An Sist Sanit Navar 2025; 48(1): e1118. https://doi.org/10.23938/ASSN.1118

21. National Institutes of Health (NIH). National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol’s effects on health. Research-based information on drinking and its impact. Consulted 2025 Feb 1. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking

22. RAHMAN MA, HANN N, WILSON A, MNATZAGANIAN G, WORRALL-CARTER L. E-Cigarettes and smoking cessation: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015; 10(3): 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122544

23. IPAQ Research Committee. Guidelines for Data Processing and Analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)-Short Form 2004. Cited January 11, 2025. https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/ukb/refer.cgi?id=540

24. KARP A, PAILLARD-BORG S, WANG HX, SILVERSTEIN M, WINBLAD B, FRATIGLIONI L. Mental, physical and social components in leisure activities equally contribute to decrease dementia risk. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2006; 21(2): 65-73. https://doi.org/10.1159/000089919

25. GÓMEZ-SORIA I.,FERREIRA C., OLIVÁN-BLÁZQUEZ B., AGUILAR-LATORRE A.,CALATAYUD E. Effects of cognitive stimulation program on cognition and mood in older adults, stratified by cognitive levels: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2023; 110: 104984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2023.104984

26. KOLLER M, STAHEL WA. Sharpening Wald-type inference in robust regression for small samples. Comput Stat Data Anal 2011; 55(8): 2504-2415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2011.02.014

27. NAKAGAWA S, SCHIELZETH H. A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods Ecol Evol 2013; 4 (2): 133-142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00261.x

28. DJABELKHIR L, WU YH, VIDAL JS, CRISTANCHO-LACROIX V, MARLATS F, LENOIR H et al. Computerized cognitive stimulation and engagement programs in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: Comparing feasibility, acceptability, and cognitive and psychosocial effects. Clin Interv Aging 2017; 12: 1967-1975. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S145769

29. VÁSQUEZ-CARRASCO E, HUENCHUQUEN C, FERRÓN C, HERNANDEZ-MARTINEZ J, LANDIM SF, HELBIG F et al. Effectiveness of Leisure-Focused Occupational Therapy Interventions in Middle-Aged and Older People with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review. Healthc 2024; 12(24): 2521. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242521

30. DOI T., VERGHESE J., MAKIZAKO H., TSUTSUMIMOTO K, HOTTA R., NAKAKUBO S. Effects of cognitive leisure activity on cognition in mild cognitive impairment: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017; 18(8): 686-691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.02.013

31. JORNKOKGOUD K, MAKMEE P, WONGUPPARAJ P. Tablet- and group-based multicomponent cognitive stimulation for older adults with mild cognitive impairment : Single-group pilot study and protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc 2025; 14(1): e64465. https://doi.org/10.2196/64465

32. DJABELKHIR-J L, WU YH, BOUBAYA M, MARLATS F, LEWIS M, VIDAL JS et al. Clinical interventions in aging dovepress differential effects of a computerized cognitive stimulation program on older adults with mild cognitive impairment according to the severity of white matter hyperintensities. Clin Interv Aging 2018; 13: 1543-1554. http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S152225

33. EAGLESTONE G, GKAINTATZI E, JIANG H, STONER C, PACELLA R, MCCRONE P. Cost-effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for mild cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review of economic evaluations and a review of reviews. PharmacoEconomics Open 2023; 7(6): 887-914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-023-00440-z

34. APÓSTOLO J, BOBROWICZ-CAMPOS E, GIL I, SILVA R, COSTA P, COUTO F et al. Cognitive stimulation in older adults: An innovative good practice supporting successful aging and Self-Care. Transl Med UniSa Internet 2019; 19: 90-94. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6581488/pdf/tm-19-090.pdf

35. SALMON N. Cognitive stimulation therapy versus acetyl cholinesterase inhibitors for mild to moderate dementia: A latter-day David and Goliath? Br J Occup Ther 2006; 69 (11): 528-530. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260606901107

36. FALLAHPOUR M, BORELL L, LUBORSKY M, NYGÅRD L. Leisure-activity participation to prevent later-life cognitive decline: A systematic review. Scand J Occup Ther 2015; 23 (3): 162-97. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2015.1102320

37. ROTENBERG S, MAEIR A, DAWSON DR. Changes in activity participation among older adults with subjective cognitive decline or objective cognitive deficits. Front Neurol 2020; 10: 1-8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.01393

38. ZHANG Y, YANG X, GUO L, XU X, CHEN B, MA X et al. The association between leisure activity patterns and the prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults. Front Psychol 2023; 13: 1080566. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1080566

39. ANGEVAARE MJ, VONK JMJ, BERTOLA L, ZAHODNE L, WATSON CWM, BOEHME A et al. Predictors of Incident Mild Cognitive Impairment and Its Course in a Diverse Community-Based Population. Neurology 2022; 98 (1): E15-E26. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000013017

40. CHIU YC, HUANG CY, KOLANOWSKI AM, HUANG HL, SHYU Y (LOTUS), LEE SH et al. The effects of participation in leisure activities on neuropsychiatric symptoms of persons with cognitive impairment: A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud 2013; 50(10) : 1314-1325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.01.002

41. YATES LA, ZISER S, SPECTOR A, ORRELL M. Cognitive leisure activities and future risk of cognitive impairment and dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Psychogeriatrics 2016; 28 (11):1791-1806. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216001137

42. LIVINGSTON G, HUNTLEY J, SOMMERLAD A, AMES D, BALLARD C, BANERJEE S et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020; 396 (10248): 413-446. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6

43. Castilla D, Suso-Ribera C, Zaragoza I, Garcia-Palacios A, Botella C. Designing icts for users with mild cognitive impairment: A usability study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17 (14): 1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145153

Publicado

Cómo citar

Número

Sección

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2025 Anales del Sistema Sanitario de Navarra

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-CompartirIgual 4.0.

La revista Anales del Sistema Sanitario de Navarra es publicada por el Departamento de Salud del Gobierno de Navarra (España), quien conserva los derechos patrimoniales (copyright ) sobre el artículo publicado y favorece y permite la difusión del mismo bajo licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional (CC BY-SA 4.0). Esta licencia permite copiar, usar, difundir, transmitir y exponer públicamente el artículo, siempre que siempre que se cite la autoría y la publicación inicial en Anales del Sistema Sanitario de Navarra, y se distinga la existencia de esta licencia de uso.

Datos de los fondos

-

Gobierno de Aragón

Números de la subvención GAIAP, B21_23R