Intangible Cultural Heritage and Education: Analysis of the UNESCO Safeguarding Good Practices Register

Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial y Educación: Análisis del Registro de Buenas Prácticas de Salvaguarda de la UNESCO

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2025-407-655

Marc Ballesté Escorihuela

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9422-2020

Universitat de Lleida

Sofia Isus Barado

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8212-8443

Universitat de Lleida

Anna Solé-Llussà

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2921-5956

Universitat de Lleida

Ares Fernandez Jové

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2916-053X

Universitat de Lleida

Abstract

With the approval of the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2003, UNESCO promoted several initiatives to facilitate the safeguarding of this type of property. In this sense, it created a Register of Good Practices for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, which includes all those programmes that meet the criteria of the aforementioned Convention. One of the aspects that is valued is the field of education, formal and non-formal, since it recognises in it a great potential for the development of actions that contribute to knowledge, assessment and transmission of intangible cultural heritage. This study analyses the educational initiatives included in the UNESCO Register of Good Safeguard Practices programmes, in order to identify trends and facilitate the development of future projects. A content analysis and a statistical-descriptive treatment of the data have been carried out. The results show that education is present in all the registry programmes in terms of the non-formal context, although only half have a defined educational design. Formal education is the area least explored, with primary education being the level towards which the most activities are directed. A lack of participation of educational institutions, families and communities is also identified. In short, education is present in all the projects included in the Register of Good Safeguard Practices of UNESCO, although not as specific or for diverse audiences and ages in all areas. A broader, systematised approach would enable us to achieve more beneficial results for intangible cultural heritage and communities that transmit and enjoy it.

Keywords: heritage education, intangible cultural heritage, UNESCO, educational practices of reference, safeguarding of heritage, content analysis.

Resumen

Con la aprobación de la Convención para la Salvaguarda del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial del 2003, la UNESCO impulsó diversas iniciativas para facilitar la salvaguarda de esta tipología de bienes. En este sentido, creó un Registro de Buenas Prácticas de Salvaguarda del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial, en el que se incluyen todos aquellos programas que cumplen con los criterios de la citada Convención. Uno de los aspectos que se valora es el ámbito de la educación, formal y no formal, puesto que en ella se reconoce un gran potencial para el desarrollo de acciones que contribuyen al conocimiento, valoración y transmisión del patrimonio cultural inmaterial. El presente estudio analiza las iniciativas educativas incluidas en los programas del Registro de Buenas Prácticas de Salvaguarda de la UNESCO, con el fin de identificar tendencias y facilitar el desarrollo de futuros proyectos. Se ha llevado a cabo un análisis de contenido y un tratamiento estadístico-descriptivo de los datos. Los resultados muestran que lo didáctico está presente en todos los programas del registro en lo que a contexto no formal se refiere, aunque solo la mitad disponen de un diseño educativo definido. La educación formal es el ámbito menos explorado, siendo la primaria la etapa a la que más actividades se dirigen. Se identifica también una falta de participación de las instituciones educativas, familias y comunidades. En definitiva, la educación está presente en todos los proyectos inscritos en el Registro de Buenas Prácticas de Salvaguarda de la UNESCO, aunque no en todos los ámbitos, con el mismo grado de concreción, ni para los diferentes públicos o edades. Un enfoque más amplio y sistematizado permitiría alcanzar resultados más beneficiosos para el patrimonio cultural inmaterial y las comunidades que lo transmiten y disfrutan.

Palabras clave: educación patrimonial, patrimonio cultural inmaterial, UNESCO, buenas prácticas educativas, salvaguarda del patrimonio, análisis de contenido.

Introduction

In October 2003, the General Conference of UNESCO at its 32nd session in Paris adopted the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, which aims to safeguard, respect, raise awareness, as well as to provide cooperation and assistance for Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) (UNESCO, 2010). The agreements include the creation of three lists at an international level: the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding and the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices. The latter, in accordance with approved criteria and at the proposal of the states, annually selects and disseminates programmes, projects, and activities that reflect the principles of the Convention.

At a time when lists of good practices are on the rise, it is of interest to look closer at these in order to detect trends and clarify any possible gaps. The case of the register managed by UNESCO, which provides information and examples of actions developed at an international level, can provide us with an approximation of the most common currents or practices regarding the management of an intangible cultural expression. Consequently, it can also provide us with an indication of what has been achieved from an educational stance, one of the core principles of the international institution.

Heritage education has been linked to UNESCO since 1972 by including chapters dedicated to training or pedagogy in the different conventions or recommendations developed over the subsequent years (Fontal & Ibáñez, 2017). It was in 2003 that this link was established as regards to intangible cultural heritage.

This study aims to analyse what has been done in different territories in terms of pedagogy included in the UNESCO register of good practices, in order to facilitate the design and development of new actions that help to safeguard expressions, traditions or festivals, whether or not they are on the representative list of ICH.

Theoretical basis

Since its creation in 1945, UNESCO has placed education at the centre of its mission, as a tool for peace and sustainable development. In 1972, with the World Cultural and Natural Heritage Convention, education is strongly linked to heritage (UNESCO, 1972). Subsequent texts or measures of the same entity refer to educational programmes as a guarantor of respect for heritage. At a European level, progress is also being made in this direction and recommendations are defined around heritage education and its innovative approach (Fontal & Ibáñez, 2017).

With the 2003 Convention, education in all its fields is presented as an essential element for the knowledge, appreciation, and transmission of ICH. The subsequent ratification of the Convention by the various states leads to new laws and national safeguarding plans that call for educational measures. Spain, for example, ratified the Convention in 2006 and developed the National Plan for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (IPCE, 2011), the National Plan for Education and Heritage (IPCE, 2013), as well as Law 10/2015, for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Heritage education is no longer an emerging area of knowledge, it is now an important discipline at academic, social and institutional levels, as it has the capacity to generate research, programmes, and laws (Fontal et al., 2015). UNESCO’s register of good practices for the safeguarding of the ICH is a reflection of this, as it provides numerous examples related to pedagogy.

The educational potential of heritage has been identified for several decades. In 1996, Arendt already mentioned that in tradition “we find the key to interpreting the past and reflecting on the future” (p.104). It helps us understand where we have come from and provides us with tools for future action. It is a “resource for gaining knowledge of the social, cultural and natural environment” (Estepa et al., 2005, p. 21) that facilitates the understanding of past and present societies, and contributes to the conscious understanding of our identity (Cuenca et al., 2011).

Contact with heritage can “promote a sense of relevance and involve young people in the construction of their knowledge and their present and future action” (Pinto et al., 2015, p. 125). In the case of the ICH, it also offers the possibility to enhance sociability and active participation in festivals and traditions. In short, it helps to value “one’s own identity and the understanding that every individual is a cultural subject” (Santacana & Llonch, 2016, p. 147).

Working with it also allows us to analyse the local elements and then move on to the universal ones, thus establishing possible relations between the local and global elements, making use of the concept of “glocality” (Gil and Vilches, 2004). When seeing what is distant, heritage contributes to the recognition of diversity, cultural and individual, and therefore to the respect and defence of heterogeneity (Cuenca et al., 2011).

Beyond the knowledge of heritage, it facilitates the construction of moral autonomy and critical thinking, forming citizens capable of decoding information, interpreting it and intervening (Estepa et al., 2005). Citizens who value social heritage will protect it when necessary. If we assume that the correct safeguarding of heritage is not limited to having specialists, but rather it must essentially include educational action, thus ensuring its future.

As Fontal and Martínez (2016) point out, pedagogy brings us closer to tradition, in the case of the ICH, it allows us to know, understand and value it, and therefore enabling its appropriation for the purpose of caring, preserving and transmitting it. Such a chaining is key to the awareness and sustainable management of cultural expressions; “education is not just another glance, but rather it illuminates the rest, because it is in education where we work on the relationship between assets and people” (Fontal, 2010, p. 267).

This process of knowledge-understanding-assessment-appropriation-care-enjoyment of heritage can take place inside and outside the classroom, in formal and non-formal education, with links to institutions or independently. As Estepa et al. (2007) point out, heritage education seems to be more typical of non-formal education, and despite the presence of terms such as heritage, culture, memory, or identity in official curricula, “there is a gap between the didactic potential of heritage and its presence” (Pinto and Molina, 2015, p. 104) both in laws and in the activities taught in schools.

There is also an imbalance between the types of heritage worked on, since there are, for example, more didactic experiences related to tangible heritage than to ethnological heritage (Cuenca et al., 2011; Yáñez et al., 2023). With this being the closest heritage in time, yet it does not have the same prominence. In reality, it seems that teachers grant a lower identification to ethnological elements and a greater appreciation for natural and historical-artistic ones, with their most frequent teaching activity being a visit to a heritage site (Estepa et al., 2007; Yáñez, 2023), which is difficult to specify in the case of ICH.

Despite this shortcoming, it is worth insisting on the potential of heritage within schools and high schools, given that it allows working on much more than the acquisition of knowledge related to history, nature, festivals, or traditions; as it is capable of being treated not only as an object of study, but also as a pedagogical resource (Fontal & Ibáñez, 2017). Heritage can be the vehicle for achieving cross-curricular objectives in different subjects (Ibarra et al., 2014). It can be an interdisciplinary reference, establishing links between science, society, and the environment.

The training bias of professionals, the fragmentation of the academic curriculum, as well as the specialisation of museums and centres (Cuenca et al., 2011), all inherited from a society that has compartmentalised disciplines, does not help to make heritage an element with many possibilities for the teaching-learning process. The textbook, as a basic resource for teaching practice, presents heritage with a disciplinary and anecdotal character that does not allow for its relationship with societies (Estepa et al., 2011). Teaching staff also have a fragmentary view of heritage. Heritage managers, on the other hand, have a more holistic perception (Estepa et al., 2007), however this does not translate into a much greater number of integrated transdisciplinary, social and identity-based educational practices. Whether or not in the school framework, it is important to define the purpose of why heritage is taught, what training is needed to promote and how it is developed, overcoming the obstacles that distance it from teaching and bringing it closer to the citizens’ education (Cuenca et al., 2011). In terms of the ICH, moreover, pedagogical action should be considered not only necessary but essential, as these are processes that involve relationships and experiences, which are elements inherent to education (Fontal and Martínez, 2017).

Taking into consideration the trajectory of heritage education in recent decades and the reflections raised, it is interesting to study which programmes of the UNESCO Intangible Heritage Safeguarding Register carry out activities in the field of formal and non-formal education and compare that with similar analyses that deal with the same typology of heritage, such as those developed by Fontal and Martínez in 2017 in Spain.

The register was launched in 2009 by the Intergovernmental Committee at its fourth session in Abu Dhabi. That year it selected three of the five programmes submitted, in line with the principles and objectives of the 2003 Convention. In subsequent years, new projects from different countries have been added to the list, with an average acceptance rate of 57.2% of the applications submitted (Table I).

TABLE I. Programmes proposed and approved in the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices

Year |

Proposals (N) |

Approved (N) |

Percentage (%) |

2009 |

5 |

3 |

60 |

2010 |

- |

- |

- |

2011 |

12 |

5 |

41.6 |

2012 |

2 |

2 |

100 |

2013 |

2 |

1 |

50 |

2014 |

4 |

1 |

25 |

2015 |

- |

- |

- |

2016 |

7 |

5 |

71.4 |

2017 |

4 |

2 |

50 |

2018 |

2 |

1 |

50 |

2019 |

3 |

2 |

66.7 |

Source: Compiled by the authors based on UNESCO data (n.d.).

According to UNESCO (2010), programmes, projects, or activities must meet nine criteria relating to the safeguarding concept expressed by the agency, their contribution to the viability of relevant ICH, the involvement of carriers, the capacity to being considered a model, their potential for evaluation, as well as their appropriateness to the needs of the country or countries where they are implemented.

This study does not attempt to identify the adoption of these criteria by the programmes, nor whether they can represent a model for other practices. Its main objective is to analyse the educational actions of the mentioned programmes, included in the Register of Good Practices for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, whether formal or non-formal, as well as the knowledge of the target audience, the possible existence of an educational design and an evaluation system or the actors involved, in order to determine trends and assess if what is shared can be a practical and useful tool, as intended by UNESCO.

Methodology

Sample

Twenty-two practices registered during the first ten years of the register’s existence have been analysed, specifically from 2009 to 2019, and those being from eighteen different countries. The subject of the projects or activities is very diverse: crafts, music, traditional games, dance, performing arts or construction methods, among others; and they can have a very broad scope of action, with research, transmission and dissemination actions, or be focused on a specific aspect such as pedagogy or ICH management (Table II).

TABLE II. Programmes registered in the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices from 2009 to 2019, accompanied by the countries that submitted the relevant application

Year |

Country |

Project |

2009 |

Spain |

Centre for Traditional Culture - School Museum of Pusol pedagogic project |

2009 |

Bolivia, Chile and Peru |

Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage of Aymara communities in Bolivia, Chile and Peru |

2009 |

Indonesia |

Education and training in Indonesian Batik intangible cultural heritage for elementary, junior, senior, vocational school and polytechnic students, in collaboration with the Batik Museum in Pekalongan |

2011 |

Belgium |

A programme of cultivating ludodiversity: safeguarding traditional games in Flanders |

2011 |

Brazil |

Call for projects of the National Program of Intangible Heritage (PNPI) |

2011 |

Brazil |

Fandango’s Livings Museum |

2011 |

Spain |

Revitalization of the traditional craftsmanship of lime-making in Morón de la Frontera |

2011 |

Hungary |

The Táncház method: a Hungarian model for the transmission of intangible cultural heritage |

2013 |

Spain |

Methodology for inventorying intangible cultural heritage in biosphere reserves: the experience of Montseny |

2013 |

Mexico |

Xtaxkgakget Makgkaxtlawana: the Centre for Indigenous Arts and its contribution to safeguarding the intangible cultural heritage of the Totonac people of Veracruz |

2013 |

China |

Strategy for training coming generations of Fujian puppetry practitioners |

2014 |

Belgium |

Safeguarding the carillon culture: preservation transmission, exchange and awareness-raising |

2016 |

Austria |

Regional centres for craftsmanship, a strategy for safeguarding the cultural heritage of traditional handicraft |

2016 |

Bulgaria |

Festival of folklore in Koprivshtitsa, a system of practices for heritage presentation and transmission |

2016 |

Croatia |

Community project of safeguarding the living culture of Rovinj/Rovign, the Batana ecomuseum |

2016 |

Hungary |

Safeguarding of the folk music heritage by the Kodály concept |

2016 |

Norway |

Oselvar boat, reframing a traditional learning process of building and use to a modern context |

2017 |

Bulgaria |

The Bulgarian Chitalishte (Community Cultural Centre): practical experience in safeguarding the vitality of the intangible cultural heritage |

2017 |

Uzbekistan |

Margilan Crafts Development Centre, safeguarding of the atlas and adras making traditional technologies |

2018 |

Sweden |

Land-of-Legends programme, for promoting and revitalising the art of storytelling in the Kronoberg region |

2019 |

Venezuela |

Biocultural programme for the safeguarding of the tradition of the Blessed Palm |

2019 |

Colombia |

Safeguarding strategy of traditional crafts for peace building |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Procedure

In order to analyse these programmes, a strictly qualitative content analysis was carried out of all the nomination reports registered in the UNESCO Register of Good Safeguarding Practices, and a subsequent statistical-descriptive study of the results of the first analysis (López, 2002), extracting frequencies and percentages of the different elements analysed. When necessary, due to lack of information, additional programme documentation has been used, always sourced from the aforementioned reports. The example of research already developed for the evaluation of educational programmes on ICH (Fontal and Martínez, 2017) has been followed.

In the first phase, related to content review, all the projects were studied, and an inventory sheet was drawn up detailing the practice, its main actions, promoters, and beneficiaries. Specifically, this consists of three main sections with different dimensions and categories:

- Programme identification

- Programme description

- Programme actions

- Historical and ethnological research

- ICH transmission

● Formal education

● Non-formal education

● Divulgation and informal education

- Promotion of and access to ICH

For this study, the information in the sections on programme identification and description have been used, as well as the first two headings of the section on “Knowledge transfer”. The rest of the data has been used for other academic investigations that does not have education as its sole focus. The information gathered under the above headings has been categorised for its appropriate evaluation and statistical analysis. In the first instance, these categories were established deductively, in accordance with the first phase analysis, and non-exclusively; subsequently, with the detailed content analysis, they were established inductively. The resulting categories amounted to a total of 31:

- Formal education:

- Typology:

- Educational project

- Learning methodologies and techniques

- Materials or educational activity

- Apprenticeships

- Recipients:

- Infant Education

- Primary Education

- Secondary Education

- Higher Education

- Typology:

- Non-formal education:

- Typology:

- Workshops

- Trainings or courses

- Conferences, seminars, or congresses

- Exchange of experiences

- Demonstrations

- Competitions

- Recipients:

- Children

- Young people

- Teachers or cultural facilitators

- General public

- ICH stakeholders

- Typology:

- Educational design

- Yes

- No

- Assessment

- Yes

- No

- Involvement in the programme:

- Institutions or companies

- Associations and NGOs

- ICH stakeholders

- Schools or high schools

- Families and communities

- Universities and researchers

Likewise, in order to specify some categories, some conditioning factors have been defined, based on theoretical references or previous analyses. In this sense, formal education has been considered as those activities carried out in schools and formal educational centres that provide an official certificate, and non-formal education as those non-curricular actions carried out outside the school environment (Cuadrado, 2008). As regards the former, the typologies of activities in this area have been categorised as follows:

- Educational project: It is interdisciplinary being developed at different levels and/or subjects and even in different educational centres, with defined objectives and programme.

- Learning methodologies and techniques: Designed for learning a tradition, art, or technique.

- Materials or educational activity: Resources for the teaching team or individual classroom actions, such as workshops, visits, etc.

- Apprenticeships: Apprenticeships conducted with the carriers in order to learn a tradition or technique.

Finally, an activity with a defined educational design is one that includes a justification, objectives, contents, counselling, strategies, timing, and evaluation (Fontal and Martínez, 2017).

Results

Educational field

All the programmes analysed include some sort of educational activity; in some of them, as previously mentioned, it is the main function to be carried out. However, looking at the field of action, this repetition is only maintained in non-formal education, which is present in all projects. On the other hand, formal education activities are only included in 63.6% of the reports, almost all of which have a defined educational design. Only two projects operate in a school context without a clear design, i.e. without clear justification, objectives, contents.... Overall, 50% of the programmes have a delimited design.

Typology of activities and levels of education in formal education

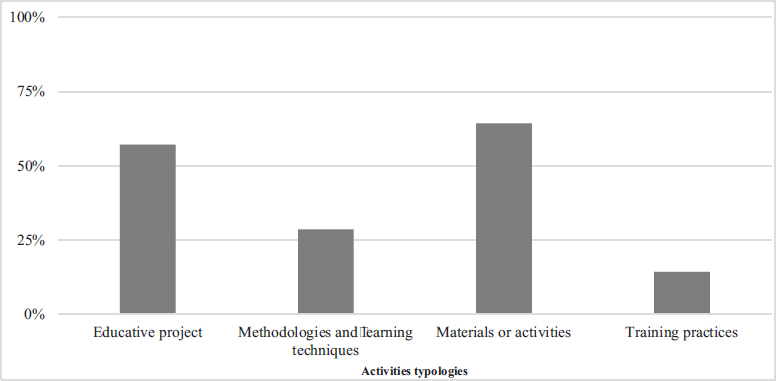

In terms of the type of actions carried out in the field of formal education, according to all the programmes included in the aforementioned 63.3%, the design and use of educational resources or sporadic classroom activities is the most frequent option (64.3%), followed by the development of educational projects with clear programming and objectives (57.1%), the definition of learning methodologies or techniques (28.6%) and finally by the execution of training practices (14.3%) (Graph I).

GRAPH I. Typology of activities in the field of formal education

Source: Compiled by the authors.

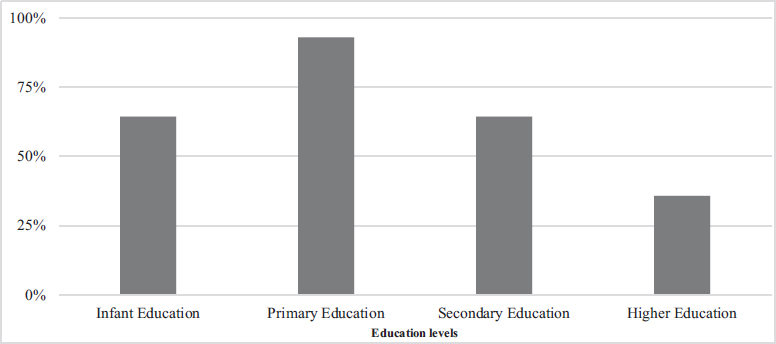

Remaining in the formal sphere, with the programmes included in it as the total number of data, 64.3% of the projects have an impact on infant and secondary education, 92.9% on primary education and 35.7% on higher education (Graph II).

GRAPH II. Impact of the programmes at different levels of education

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Type of activities and target groups in non-formal education

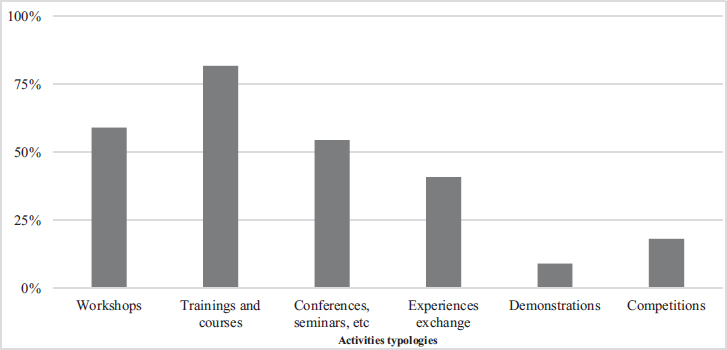

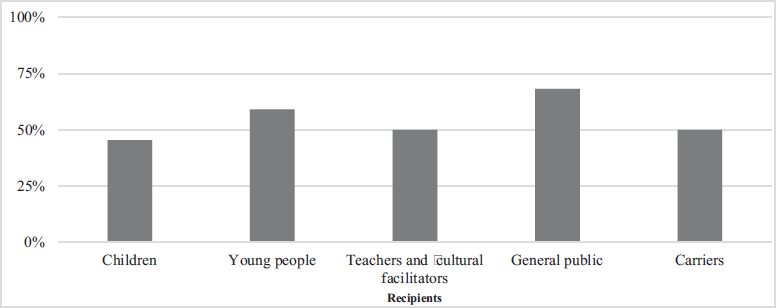

Concerning non-formal education, which is present in all the programmes, 81.8% propose training or courses, 59.1% workshops, 54.5% conferences, seminars or congresses, 40.9% exchanges of experiences, 18.2% competitions of various natures and 9.1% demonstrations by the carriers (Graph III). These activities are aimed at the general public 68.2% of the time, 59.1% at young people, 50% at teachers or cultural facilitators, 50% at carriers and 45.5% at children (Graph IV).

GRAPH III. Type of activities in the field of non-formal education

Source: Compiled by the authors.

GRAPH IV. Target group for non-formal activities

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Evaluation, groups involved and countries

Considering evaluation, i.e. the existence of tools to validate the functioning and results of the programme, only 22.7% of the reports state that they have a clear and defined system.

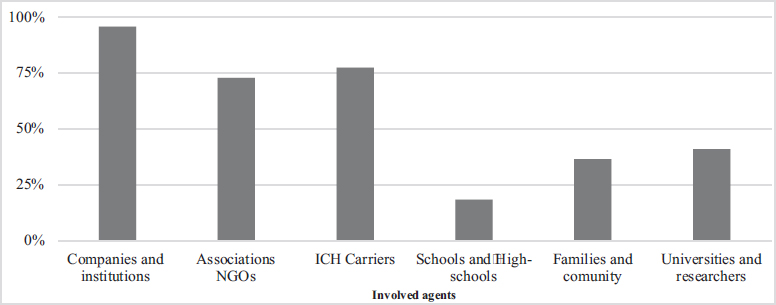

As far as involvement in the design and implementation of the projects is concerned, in practically all cases some institution or company has been involved (95.5%), in a smaller percentage carrier participate (77.3%), associations and NGOs (72.7%), universities and researchers (40.9%), families or communities (36.4%) and in fewer cases schools and high schools (18.2%) (Graph V).

GRAPH V. Actors involved in the design and implementation of the programmes

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Finally, considering the variable of country of origin, we find some repeated presences and many absences, since, as will be discussed in the following section, this is a list that is constructed by registration. Spain stands out with three approved programmes, followed by Belgium, Brazil, Hungary, and Bulgaria with two, and Bolivia, Chile, Peru, Indonesia, Mexico, China, Austria, Croatia, Norway, Uzbekistan, Sweden, Venezuela and Colombia, with one.

Discussion

The analysis of the projects included in the UNESCO register of good practices confirms what has been highlighted by other authors regarding the preponderance of non-formal education in terms of heritage education. In 2005, Estepa already expressed that the revaluation of heritage had converged in initiatives in the non-formal sphere and minor changes in the formal context. Pinto and Molina (2015), drawing on the same author, wrote something similar about curricula, stating that heritage education should no longer be seen “as something no longer inherent (if not exclusive) to non-formal education” (p.106). In this case, 100% of the reports include some kind of activity carried out in a non-school environment and 63.6% in a formal environment. This percentage difference is in line with the trend reported by Fontal and Martínez (2017).

It is essential that the heritage aspect is emphasised in educational activities and that the ethnological aspect is valued by teaching staff. The role played by the school also entails the transmission of culture. It can help to consolidate ICH in urban areas, for example, where it is often more blurred by other phenomena. In secondary school, moreover, it is highly interesting, as it is the stage of development in which many aspects of personality and identity are formed (Santacana & Llonch, 2016). One way to facilitate such formal incorporation is specific training for teachers in their higher and ongoing education, as well as a strong presence of ICH in official curricula.

In any case, it is worth highlighting the integration of education in all the programmes analysed. We note a clear interest in pedagogy in relation to the safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage, in line with UNESCO’s recommendations. With a somewhat lower percentage than the activities carried out in the formal sphere, 50% have a clear or complete educational design, thus placing them at levels close to those identified in similar studies (Fontal & Martínez, 2017). However, no project acting solely in the non-formal context with a complete educational design is identified. It would be good to rethink why and to accept that every pedagogical activity can be susceptible to a structure, justification, objectives, contents, orientation, strategies, timing, etc.

With regard to the formal sphere and the different types of actions, 40.9% of all the programmes provide teaching resources or isolated activities and 36.4% have an educational project that brings together various actions with a clear structure. Sporadic work is seen to be the most common. In this case, it differs from the trends resulting from the analyses carried out in Spain (Fontal & Martínez, 2017), in which there is a predominance of programmes, projects and didactic designs. One possible explanation could be that the reports analysed in this study include education as an additional safeguarding action; it is not considered the main objective.

There are also projects that encompass as their backbone a learning methodology or technique, such as the Táncház method or the Kodály concept, both focused on Hungarian music and dance (Hungarian State Secretariat, 2011; Hungarian State Secretariat, 2016); and initiatives that offer training apprenticeships, as in the Colombian case of learning handicrafts (Colombian Ministry of Culture, 2019).

In line with other analyses (Fontal & Martínez, 2017), 92.9% of the recipients of what is developed in the formal context are primary school pupils. The percentage in pre-primary and secondary education coincides (64.3%), but is somewhat lower, which evidences a lack of interest or difficulty in incorporating ICH at the earliest or final levels of compulsory education. In this sense, the teaching team supports the need for initiatives, materials, and heritage training for all levels (Castro and López, 2019). As far as university level is concerned, the analysed programmes are only present in the aforementioned Hungarian learning methods, which involve all grades and ages, and in three initiatives offering activities and courses at universities or vocational training centres (Austrian Federal Chancellery, 2016; Swedish Ministry of Culture and Democracy, 2018; Colombian Ministry of Culture, 2019).

This last activity is precisely the one most frequently repeated among non-formal actions (81.8%), training and courses, followed by a similar one, workshops (59.1%), as well as seminars or congresses (54.5%) and exchanges of experiences (40.9%). Although they are not educational programmes, all of them consider it appropriate to include some kind of knowledge transfer initiative, with training courses being the most highly valued, even if they do not have a clear design, as specified above. One of the projects analysed, related to safeguarding culture of the Belgian carillon, incorporates practically all the typologies analysed, thus demonstrating the educational potential of heritage and the interest of pedagogy in culture. Heritage should be valued as more than a didactic resource for social sciences, and institutions should consider education as a fundamental part of sustainable management of expressions.

The target groups of the activities in the non-formal context are the general public (68.2%), closely followed by young people (59.1%), teachers and cultural facilitators (50%), carriers (50%) and children (45.5%). It is interesting to note that in the programmes of the last few years, the initiatives are aimed at all or almost all typologies, a fact that demonstrates an awareness on the part of the promoters. Although the percentage of carriers is not very high, this should not be a cause for concern, as there are future tradition carriers among young people and the general public.

As mentioned in the previous section , few programmes have an evaluation system, which would allow for the assessment of results and progressing towards future projects. In one of the most recent reports, regarding the art of legend telling in Sweden, for example, the responsible association evaluates and adapts the project regularly and even hires outsiders for better assessment (Swedish Ministry of Culture and Democracy, 2018). This tool is useful not only for pedagogical purposes, but for all actions, as it studies all aspects of research, transmission, and promotion.

With regard to the agents involved in the design and implementation of good practices, there is a clear need to have one or more institutions, companies, or associations involved in the project. In all cases they have one or more examples. It is also noteworthy that 77.3% of the reports cite the carriers as being involved, whether or not they are the direct recipients, which complies with the recommendation of UNESCO and ICH scholars in that any action should be developed with the knowledge, permission, and participation of the protagonists. This relationship improves the approach and content, and ultimately the quality of the educational project (Ballesté et al., 2021; Ballesté et al., 2022).

There is still a lack of greater involvement of schools, which appear in 18.2% of the programmes, as well as families and the community (36.4%). The intervention of these agents would also improve the quality of the initiatives, not only for the processes of heritage and identity building (Fontal & Gómez-Redondo, 2016), but also at a pedagogical level, as it would allow for working with learning communities (Wenger, 2002).

Finally, looking at the country of origin of the programmes, we see that Spain has three registrations, Belgium, Brazil, Hungary, and Bulgaria have two, and thirteen other countries from different continents have one. However, this is a variable that cannot be assessed to a large extent, as the register of good safeguarding practices operates on a registration basis. The adoption of the 2003 Convention by UNESCO member states, as well as the development of national plans or laws, will undoubtedly condition the submission of nominations. In addition, some states prioritise submitting nominations on the other two lists, especially if it is the one that involves urgent safeguarding measures and, therefore, a financial investment by the international institution.

Conclusions

Considering everything, this research has allowed for identifying didactic trends in terms of the programmes registered in the UNESCO Register of Good Practices for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, the way in which they comply with the organisation’s advice, as well as their similarity with the results of other initiatives.

UNESCO’s guidelines for the 2003 Convention recommend promoting and integrating ICH into formal and non-formal education (UNESCO, 2010). However, in this study, it has been found that the formal is still less present in the projects. Looking towards the future, it should be seen as a necessary area and incorporated into initiatives, despite structural and educational difficulties. It is also possible to go beyond the development of isolated resources or activities and develop educational projects for different levels, not only for primary education, with a variety of actions. This would help in the chain of teaching and learning about heritage, which begins with knowledge and understanding, continues with appreciation and identification, and ends with preservation, enjoyment, and transmission (Fontal and Martínez, 2016).

Regarding the non-formal sphere, there is a guaranteed presence, with different types of activities aimed at different audiences. However, a clear pedagogical structure, i.e., a complete educational design that ensures the correct approach and development of the actions and, ultimately, a better teaching-learning process, has yet to be incorporated into these.

These results, those of both contexts, coincide with the trends identified so far, also with regard to the monitoring system of the programmes, as few of them have a systematised evaluation, and therefore do not have the tools to guarantee their improvement.

Finally, the adequate involvement of institutions, associations, and carriers in the design and development of the actions analysed should be emphasised. All that remains is to engage or include universities and researchers, as well as schools, families and communities, in order to achieve better quality and more efficient programmes. Promoting participation in heritage education would help with the ultimate goal of any programme, the recognition, respect, and appreciation of the ICH (UNESCO, 2010) and the formation of critical, respectful people with a connection to culture and idiosyncrasy.

Limitations and prospects

As mentioned in previous sections, entry in the UNESCO Register of Good Safeguarding Practices is by application, thus programmes that have been unwilling or unable to initiate a process of capitalisation of their results are not taken into consideration. This limitation constrains the present study and does not allow it to analyse additional good practices of possible interest even beyond the member states of the organisation.

On the other hand, the reports presented do not allow an assessment of whether educational initiatives have adaptations for people with functional diversity or the degree of use of ICTs, two aspects that are on the rise in terms of pedagogical research (Fontal and Martínez, 2017). In short, these reports, as Royuela (2023) points out, have a reductionist structure, so it would be necessary to complete them with additional data.

In summary, this research could be extended with other similar registers from other institutions or international administrations, or the programmes already analysed could be studied in more depth using other methodologies, such as fieldwork, in order to obtain more information on educational practices.

From another perspective, the study could be repeated in the year 2029, when another ten years will have passed, thus providing a new review of the baseline projects and understanding what patterns have been maintained over time and what significant changes have occurred.

Bibliographical references

Arendt, H. (1996). Entre el pasado y el futuro; ocho ejercicios sobre la reflexión política. Península.

Austrian Federal Chancellery (2016). Regional centres for craftsmanship, a strategy for safeguarding the cultural heritage of traditional handicraft (Nº 01169). UNESCO. https://ich.unesco.org/es/BSP/estrategia-para-salvaguardar-el-patrimonio-cultural-de-la-artesana-tradicional-los-centros-regionales-artesanos-01169?Art18=01169

Ballesté, M., Solé-Llussà, A., & Isus, S. (2021). Educación y Patrimonio UNESCO: una propuesta didáctica interdisciplinar en Educación Primaria. En J.C. Bel, J.C. Colomer y N. de Alba (Eds.), Repensar el currículum de Ciencias Sociales: prácticas educativas para una ciudadanía crítica (pp. 477-486). Tirant Lo Blanch.

Ballesté, M., Solé-Llussà, A., Fernández, A., & Isus, S. (2022). The Solstice Fire Festivals in the Pyrenees: Constructing a Didactic Programme for Formal Education along with the Educational and Bearer Communities. Heritage, 5, 2519-2533. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5030131

Castro, L., & López, R. (2019). Educación patrimonial: necesidades sentidas por el profesorado de infantil, primaria y secundaria. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 94 (33.1), 97-114. https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/RIFOP/article/view/72020

Colombian Ministry of Culture (2019). Safeguarding strategy of traditional crafts for peace building (Nº 01480). UNESCO. https://ich.unesco.org/es/BSP/estrategia-de-salvaguardia-de-la-artesana-tradicional-para-la-construccin-de-la-paz-01480?Art18=01480

Cuadrado, T. (2008). La enseñanza que no se ve: educación informal en el siglo XXI (v. 7). Narcea Ediciones.

Cuenca, J., Estepa, J., & Martín, M. (2011). El patrimonio cultural en la educación reglada. Revista de Patrimonio Cultural de España, 4, 45-58.

Estepa, J., Ávila, R. M., & Ruiz, R. (2007). Concepciones sobre la enseñanza y difusión del patrimonio en las instituciones educativas y los centros de interpretación. Estudio descriptivo. Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales, 6, 75-94.

Estepa, J., Ferreras, M., López, I., & Morón, H. (2011). Análisis del patrimonio presente en los libros de texto: obstáculos, dificultades y propuestas. Revista de Educación, 355, 573-588.

Estepa, J., Wamba, A., & Jiménez, R. (2005). Fundamentos para una enseñanza y difusión del patrimonio desde una perspectiva integradora de las ciencias sociales y experimentales. Investigación en la Escuela, 56, 19-26.

Fontal, O. (2010). La investigación universitaria en Didáctica del patrimonio: aportaciones desde la Didáctica de la Expresión Plástica. En II Congreso Internacional de Didácticas (pp. 267/1-7). http://dugi-doc.udg.edu:8080/bitstream/handle/10256/2790/267.pdf?sequence=1

Fontal, O., García, S., & Ibáñez, A. (2015). Educación y patrimonio. Visiones caleidoscópicas. Trea.

Fontal, O., & Gómez-Redondo C. (2016). A Quarterly Review of Education. Heritage Education and Heritagization Processes: SHEO Metodology for Educational Programs Evaluation. Interchange, 46 (1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-015-9269-z

Fontal, O., & Ibáñez, A. (2017). La investigación en Educación Patrimonial. Evolución y estado actual a través del análisis de indicadores de alto impacto. Revista de Educación, 375, 184-214. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2016-375-340

Fontal, O., & Martínez, M. (2016). Análisis del tratamiento del Patrimonio Cultural en la legislación educativa vigente, tanto nacional como autonómica, dentro de la educación obligatoria. IPCE.

Fontal, O., & Martínez, M. (2017). Evaluación de programas educativos sobre Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial. Estudios pedagógicos, 43(4), 69-89. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07052017000400004

Gil, D., & Vilches, A. (2004). Museos para la “glocalidad”: una propuesta de museo que ayude a analizar los problemas de la región dada en el marco de la situación en el mundo. Eureka, 1(2), 87-102. http://www.apac-eureka.org/revista.

Hungarian State Secretariat (2011). The Táncház method: a Hungarian model for the transmission of intangible cultural heritage (Nº 00515). UNESCO. https://ich.unesco.org/es/BSP/mtodo-tnchz-un-modelo-hngaro-para-la-transmisin-del-patrimonio-cultural-inmaterial-00515?Art18=00515

Hungarian State Secretariat (2016). Safeguarding of the folk music heritage by the Kodály concept (Nº 01177). UNESCO. https://ich.unesco.org/es/BSP/salvaguardia-del-patrimonio-folclrico-musical-mediante-el-mtodo-kodly-01177?Art18=01177

Ibarra, M., Bonomo, U., & Ramírez, C. (2014). El patrimonio como objeto de estudio interdisciplinario. Reflexiones desde la educación formal chilena. Polis, Revista Latinoamericana, 13(39), 373-391. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-65682014000300017

IPCE (2011). Plan Nacional de Salvaguarda del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial. IPCE.

IPCE (2013). Plan Nacional de Educación y Patrimonio. IPCE.

Law 10/2015, 26 may, para la Salvaguardia del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial. Boletín Oficial del Estado [BOE], 126, de 27 de mayo de 2015 (Espanya). https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2015/05/26/10/con

López, F. (2002). El análisis de contenido como método de investigación. Revista de Educación, 4, 167-179. http://rabida.uhu.es/dspace/bitstream/handle/10272/1912/b15150434.pdf?sequence1

Pinto, H., & Molina, S. (2015). La educación patrimonial en los currículos de ciencias sociales en España y Portugal. Educatio Siglo XXI, 33(1), 103-128. https://doi.org/10.6018/j/222521

Royuela, M. (2023). La gestión del patrimonio cultural inmaterial a través del Registro de Buenas Prácticas de la UNESCO. Análisis de los casos de España y México (Tesis doctoral, Universitat de Barcelona). https://www.tesisenred.net/handle/10803/31941

Santacana, J., & Llonch, N. (Ed.) (2016). El patrimonio cultural inmaterial y su didáctica. Trea.

Swedish Ministry of Culture and Democracy (2018). Land-of-Legends programme, for promoting and revitalizing the art of storytelling in Kronoberg Region (Nº 01392). UNESCO. https://ich.unesco.org/es/BSP/tierra-de-leyendas-programa-para-promover-y-revitalizar-el-arte-de-la-narracin-en-la-regin-de-kronoberg-01392?Art18=01392

UNESCO (n.d.). Decisiones del Comité Intergubernamental. https://ich.unesco.org/es/decisiones

UNESCO (1972). Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. UNESCO.

UNESCO (2010). Textos fundamentales de la Convención para la Salvaguarda del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial de 2003. UNESCO.

Wenger, E. (2002). Comunidades de práctica. Paidós Ibérica.

Yáñez, C., Fernández, A., Solé-Llussà, A., & Ballesté, M. (2023). Primary and Secondary Teachers’ Conceptions, Perceptions and Didactic Experience about Heritage: The Case of Andorra. Education Sciences, 13, 810. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13080810

Contact address: Marc Ballesté Escorihuela. Universitat de Lleida, Facultad de Educación, Psicología y Trabajo Social, Departamento de Ciencias de la Educación. Av. Estudi General, 4, 25001, Lleida. E-mail: marc.balleste@udl.cat