eISSN: 1989-9742 © SIPS.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2025.48.06

http://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/PSRI/

Versión en español: https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/PSRI/article/view/117333/85876

Hari-katu: basque as language, emotion, and community

in residential care homes for children and adolescents

in the protection system

Hari-katu: el Euskera como lengua, emoción y comunidad en hogares del sistema de protección a la infancia y a la adolescencia

Hari-katu: o basco como língua, emoção e comunidade num lar de apoio a crianças e adolescentes no sistema de protecção

Odei GUIRADO  https://orcid.org/0009-0007-5205-4595

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-5205-4595

Joana MIGUELENA  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7467-1291

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7467-1291

María DOSIL-SANTAMARÍA  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8805-9562

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8805-9562

Aintzane RODRÍGUEZ  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0959-6547

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0959-6547

Euskal Herriko University UPV/EHU

Received date: 18.VII.2025

Reviewed date: 28.IX.2025

Accepted date: 14.X.2025

CONTACT WITH THE AUTHORS

Odei Guirado: Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, UPV/EHU. Departamento de Ciencias de la Educación. Tolosa Hiribidea, 70, 20018 Donostia, Gipuzkoa. E-mail: odei.guirado@ehu.eus

|

KEYWORDS: Minority languages; translanguaging; organised leisure; informal speech; residential care. |

ABSTRACT: This article presents the results of the Hari-Katu programme, implemented in eleven residential care homes in Gipuzkoa with 66 children and adolescents aged between 8 and 15, eleven social educators, and two Pedagogy Specialist. The initiative promoted the relational use of Basque in non-formal settings through the Emotional and Conscious Translanguaging (ECT) approach, which builds on the linguistic repertoires of each participant and integrates organised leisure and play-based activities. The main objective was to examine the impact of the programme on motivation and attachment to Basque, as well as the pedagogical and linguistic implications for the educational team. A mixed-methods design was employed, with qualitative and quantitative data collected concurrently through Likert-scale questionnaires, evaluation journals, focus groups, interviews, and field notes. The findings demonstrate a positive effect on motivation, language attachment, and the spontaneous use of Basque, as well as greater engagement of the educational team in supporting the language. |

|

PALABRAS CLAVE: Lenguas minoritarias; translanguaging; ocio organizado; habla informal; acogimiento residencial. |

RESUMEN: Este artículo presenta los resultados del programa Hari-Katu, desarrollado en once hogares de acogimiento residencial de Gipuzkoa con 66 niñas, niños y adolescentes de entre 8 y 15 años, once educadores y educadoras y dos pedagogos. La iniciativa ha impulsado el uso relacional del euskera en contextos no formales mediante el Translanguaging Emocional y Consciente (TEC), que parte de los repertorios lingüísticos de cada participante e integra ocio organizado y actividades lúdicas. El objetivo principal ha sido analizar el impacto del programa en la motivación y el apego hacia el euskera, así como sus implicaciones pedagógicas y lingüísticas para el equipo educativo. Se ha empleado un diseño mixto con recogida simultánea de datos cualitativos y cuantitativos a través de cuestionarios Likert, cuadernos de valoración, grupos focales, entrevistas y notas de campo. Los resultados evidencian un efecto positivo en la motivación, el apego lingüístico y el uso espontáneo del euskera, así como en la implicación del equipo educativo en su promoción. |

|

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Línguas minoritárias; translanguaging; lazer educativo; fala informal; acolhimento residencial. |

RESUMO: Este artigo apresenta os resultados do programa Hari-Katu, desenvolvido em onze lares de acolhimento residencial em Gipuzkoa com 66 crianças e adolescentes entre 8 e 15 anos, onze educadores e educadoras sociais e dois pedagogos. A iniciativa promoveu o uso relacional do basco em contextos não formais por meio do Translinguismo Emocional e Consciente (TEC), que parte dos repertórios linguísticos de cada participante e integra lazer organizado e atividades lúdicas. O objetivo principal foi analisar o impacto do programa na motivação e no apego ao basco, bem como as suas implicações pedagógicas e linguísticas para a equipa educativa. Adotou-se um desenho metodológico misto, com recolha simultânea de dados qualitativos e quantitativos através de questionários tipo Likert, cadernos de avaliação, grupos focais, entrevistas e notas de campo. Os resultados evidenciam um efeito positivo na motivação, no apego linguístico e no uso espontâneo do basco, assim como no envolvimento da equipa educativa na sua promoção. |

1. Introduction

Residential Care Homes (RCH) provide care for children and adolescents in situations of vulnerability. These minors have been separated from their families after experiencing various forms of violence, such as physical or sexual abuse, neglect, or abandonment (Montserrat et al., 2021; Sala-Roca, 2019). The purpose of these facilities is to ensure the affective, educational, and material needs necessary for full development, while safeguarding their rights as minors, including linguistic rights (Miguelena et al., 2025).

In Gipuzkoa1, RCH operate within the context of a minority language. Although Basque is an official language, children and adolescents are not guaranteed the right to be socialised in it. The absence of linguistic competence requirements for educational staff, combined with the lack of obligation to promote the language, limits opportunities for socialisation in Basque. This, in turn, hinders inclusion in the Basque-speaking community (Miguelena et al., 2024), whose revitalisation depends on participation and community bonds (Iurrebaso & Goikoetxea, 2025).

In response to this situation, and building on Guirado et al. (in press), this article presents the results of the Hari-Katu (HK) programme, implemented in eleven RCH in Gipuzkoa with children and adolescents aged 8-15. The programme is based on educational leisure, informal speech, linguistic and emotional repertoires, and critical sociolinguistic reflection. Following an Emotional and Conscious Translanguaging (ECT) approach, it combines affective and critical dimensions with flexibility in the use of linguistic repertoires. It connects Basque with the languages of the children, not to replace their L1 or family language, but to legitimise them in dialogue with Basque (Guirado et al., 2025a). This approach strengthens community bonds from a decolonial and intersectional perspective (Dovchin, 2025; Meighan, 2025).

The underlying premise of this study is that RCH can serve as educational spaces for promoting the use of Basque. Previous research has shown that non-formal education can foster motivation and language attachment. This is particularly true for new speakers–those who have not acquired the language through family transmission–as it recognises them as active agents of revitalisation through emotionally positive experiences (Guirado, 2025; Guirado y Rua, 2023; Guirado y Santos, 2024; Guirado et al., 2025b).

Hence, the primary aim of the study is to analyse the impact of the HK programme on linguistic socialisation, motivation, and attachment to Basque among children and adolescents in RCH in Gipuzkoa. The research places identities and linguistic repertoires of these children at the centre of the pedagogical process. It also examines the pedagogical and linguistic implications for educational teams, focusing on their role as linguistic and emotional referents in daily interactions.

Consistent with international frameworks and the 2030 Agenda, this study aligns with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 4 (Quality Education), 5 (Gender Equality), 10 (Reduced Inequalities), and 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions).

1.1. Residential Care Homes in Gipuzkoa: Speech Communities and Linguistic Socialisation

Children and adolescents living in RCH constitute a group that has experienced complex and adverse life situations. These include neglect, abandonment, or violence, which hinder their socialisation, weaken affective bonds, and often result in insecure attachments (Lazpiur et al., 2025; Okland & Oterholm, 2022).

In this context, socio-educational action in RCH must support children and adolescents in developing a stable identity, meaningful relationships, and a sense of belonging (Emond, 2014). This group usually has a limited social network, which makes it difficult to build positive communities and genuine connections with their environment. Such connections are essential for safety, recognition, and personal development (Negård et al., 2020). Consequently, the educational team plays a crucial role as an emotional, social, and linguistic reference (De-Juanas et al., 2022; Moreno & García, 2009).

If language is understood as a social, emotional, and educational dimension, RCH in Gipuzkoa provide a particularly favourable environment for fostering linguistic socialisation in Basque. Children and adolescents with different home languages, such as Basque, Spanish, Arabic, or Wolof, live together in these centres. Most attend Model D2 schools, which guarantee a basic level of competence in Basque. This facilitates a more natural and conscious informal use of Basque than that typically found in school settings (Guirado et al., 2025a).

These contexts replicate the dynamics of speech communities (Singer, 2018), where informal and emotional registers reduce social distance and reinforce the sense of belonging (Koppen et al., 2019). Promoting socialisation in shared spaces beyond family transmission is essential for minority languages (Kasares, 2023). Belonging to a speech community entail establishing an emotional bond with the group, which is reinforced by the collective emotional ties of the group (Guirado & Rua, 2023).

From this perspective, RCH can be conceived as linguistic ecosystems, located between the family and school domains. They offer a supportive and affective environment that facilitates Basque usage and learning while simultaneously promoting the multilingual sociocultural inclusion of children and adolescents (Miguelena et al., 2024).

1.2. Emotional and Conscious Translanguaging (ECT): A Proposal for Non-formal Basque-language Contexts

Within minority-language settings, it is necessary to rethink multilingualism and multiculturalism from a logic of reciprocity. This approach moves beyond a merely functional view of language and recognises new speakers as active agents in their linguistic and community socialisation (Burdelski, 2020; Guirado & Rua, 2023).

Translanguaging has been understood as a practice based on individual linguistic repertoires (L1), which values identity and communicative resources regardless of age or context (Orcasitas-Vicandi & Perales, 2020; Reckmeyer, 2023). Within this field, two main approaches are distinguished: one is pedagogical and planned, and the other spontaneous, characteristic of everyday life. Over time, the latter has gained recognition and support in international academic and scientific discourse (Prado-Pereira, 2024).

In minority-language contexts such as Basque, Cenoz and Gorter (2023) argue that translanguaging must be applied strategically. This ensures the creation of “breathing spaces” that encourage the use and development of the minority language in contrast to hegemonic languages, rather than reinforcing their dominance.

In this regard, Guirado et al. (2025a) proposed the ECT as a planned linguistic strategy for non-formal contexts in which minority languages coexist within multilingual environments. In the present paper, it is applied to the Basque context to strengthen social use of the language and reinforce emotional and community bonds.

Pedagogically, ECT is framed as an intersectional and decolonial tool. It promotes equitable epistemic participation by challenging inherited linguistic hierarchies and placing the linguistic identity of each child at the centre, alongside the revitalisation of minority languages (Meighan, 2025; Prado-Pereira, 2024). Educators play a critical role within this framework, planning and accompanying activities with both linguistic and relational objectives, thereby generating emotionally positive pedagogical spaces (Dewaele & Sanz-Ferrer, 2022).

From an emotional perspective, ECT draws on studies linking translanguaging with positive emotions (Sah et al., 2025) and play environments (translanguaging playworlds) (Oakley et al., 2025). Repeated practice in real contexts is shown to strengthen the social value of the language (Dat et al., 2024; Germain & Netten, 2012) and reduce communicative anxiety (Masruroh et al., 2025).

The social dimension of ECT places the human bond at the centre of educational practice. It integrates language and emotion to foster linguistic socialisation in minority languages such as Basque within RCH. ECT is proposed as a holistic practice uniting body, culture, and relationships within the framework of social education (Planella, 2014).

1.3. Educational Leisure and Sociolinguistic Pedagogy in RCH

Play, guided by intrinsic motivation, also has cultural significance, as it generates bonds, emotions, and symbolic worlds (Huizinga, 1938/2012; Shimomura, 2023). Through leisure, play and shared-living activities, RCH can provide a safe space for socialisation and emotional well-being (Gallardo-Masa et al., 2023), as well as for fostering connections with the minority language (Guirado & Rua, 2023).

Nevertheless, children and adolescents in vulnerable situations often have limited access to such experiences, which can restrict their overall development (Ismoyo et al., 2024; García-Castilla et al., 2018). Working on Basque and linguistic competences through play and educational leisure can strengthen its social value while supporting children’s rights to leisure, language, and comprehensive education (Miguelena et al., 2024, 2025).

Play has been shown to promote motivation, reduce communicative anxiety, and encourage oral and emotional expression. This is particularly the case when it is orientated towards shared linguistic goals (Ramos & Maya, 2022; Díaz, 2012; Rodríguez, 2021) in non-formal educational settings (Guirado & Santos, 2024).

Research also highlights the importance of incorporating a sociolinguistic perspective into organised leisure and play activities that foster minority-language revitalisation–in this case, Basque (Guirado, 2025; Guirado et al., 2025b). This approach encourages reflection on linguistic phenomena from an affective and community-based perspective, promoting an integrated understanding of the relational worlds constructed through languages (Ortega, 2024; Silva & Borba, 2024).

This perspective aligns with the ECT approach, which places emotional connection, linguistic diversity, Basque, and social justice at the core of pedagogical action (Guirado et al., in press). From this standpoint, educational leisure, through play, becomes both a linguistic driver and a space for transformation, promoting a more inclusive, affective, and emancipatory education (Oakley et al., 2025).

2. Objectives of the Study

Drawing on the literature review and previous research, this study pursues the following objectives:

– (i) Analyse the impact of the Hari-Katu programme from the perceptions of children and adolescents, considering possible variations by age and gender.

– (ii) Identify the linguistic strategies most valued by children and adolescents so as to inform future pedagogical proposals.

– (iii) Evaluate the role of the educational team as a linguistic model together with its contribution to motivation and attachment to Basque.

3. Methodology

This research was carried out within a pragmatic paradigm, using a concurrent mixed methods design in which qualitative and quantitative data were collected and analysed simultaneously, giving equal weight to both approaches. The results were triangulated to facilitate comprehensive understanding (Zhao and Xu, 2024). The perceptions of the participating children and adolescents were prioritised, placing them at the centre of the study to give voice to their experiences in the programme. The perspectives of the educational team were also included, given their role in providing support and acting as linguistic referents.

3.1. Context, Participants, and the HK Programme

The HK programme was implemented over eight weeks in eleven RCH within the basic programme of Gipuzkoa. It involved eleven social educators, two Pedagogy Specialist, and an initial group of 72 children and adolescents aged between 8 and 15. Six cases were excluded due to incomplete participation, resulting in a final sample of 66 participants. The main objective was to strengthen motivation and language attachment to Basque among children and adolescents through weekly two-hour sessions in each RCH. The programme adopted an intercultural and multilingual perspective that recognises the minority status of the language within its sociolinguistic context.

The HK programme combined play-based activities, emotional dynamics, and games in Basque. It was supported by pedagogical materials from HeziZerb Elkartea, particularly the game EmoziOn! All activities were designed to develop emotional and communicative competences through the ECT approach, starting from the L1 and L2 languages of the participants.

Within this framework, emotional expressions in the L1 and L2 languages of participants were explored, with new ones created in Basque when literal translations were unsuitable, and familiar ones adopted for use in games. Children and adolescents were encouraged to move between languages to reduce communicative anxiety and foster motivation and attachment to Basque. This allowed them to progressively incorporate the language into their interactions with peers and the educational team.

The programme also sought to strengthen peer networks, build a shared collective imagination, and encourage reflection on Basque as a minority language in relation to other minority languages present in the Basque Country. The final session was dedicated to a joint evaluation and concluded with a gathering of the eleven RCH, where participants shared games and experiences, reinforcing the emotional and linguistic community of the HariKatutarrak.

Table 1 presents the linguistic profiles, age, school model, and information about the educational team

|

Table 1. Children and Adolescents and Professionals Participating in the Research and Their Linguistic Profile |

||||

|

Age range |

Participants (N) |

Linguistic profile |

School model |

Resource |

|

8-11 |

40 |

– L1 Spanish and Basque: 7 – New speakers (Basque as L2/L3): 33 |

Model D |

HAR |

|

12-15 |

26 |

– New speakers (Basque as L2/L3): 26 |

||

|

Total (N) |

66 (33 boys and 33 girls) |

|||

|

Educators |

N |

Linguistic profile |

|

Profile |

N |

Linguistic profile |

|

Pedagogy Specialist |

2 |

Speak Basque fluently |

|

Social educators |

11 |

Speak Basque fluently: 6 Have basic competence: 3 Do not speak Basque: 3 |

|

Note: Children and adolescents were asked about their gender. Source: own elaboration |

||

3.1.1. Ethical Procedure

The research adhered to relevant ethical principles, with informed consent obtained from the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa (PCG), the managing entities, the children and adolescents, and the professional teams. Participation was voluntary and altruistic, and the study received a favourable report from the Ethics Committee of the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU).

3.2. Instruments and Data Collection

The EEMA measurement instrument (Esku-hartzeek sustatutako Euskararekiko Motibazioa eta Atxikimendua) was used for the collection of quantitative data (N = 66). Aligned with the theoretical framework, this instrument focused on variables related to motivation, language attachment, and communicative anxiety, taking into account the role of play, spaces, and sociolinguistic reflection in these processes. The questionnaire scale, previously employed in earlier studies (Guirado et al., 2025), demonstrated significant reliability (α = .85; ω = .86) and appropriate internal consistency. It consists of eight Likert-type items (1-5) and was assessed in three rounds by a committee of nine experts. The purpose of this process was to refine the pertinence of the items and adapt them to the context.

Qualitative data were collected through reflection notebooks completed by the children and adolescents at the end of each session in response to the question “What did you feel today?” (66 notebooks; 528 notes). This technique made it possible to gather immediate emotions and perceptions from the participants, directly linked to the objective of analysing the impact of the programme from their lived experiences.

For the educational team, direct observation was conducted using field notebooks completed by thirteen professionals. These documented daily interactions and the educators’ role as linguistic and emotional role models. In addition, five semi-structured interviews lasting 20-25 minutes were conducted, examining perceptions of the impact of the programme on the children and adolescents and their own processes of linguistic engagement.

Predefined categories were used to organise the information gathered. These were based on studies examining the impact of systematic work with informal Basque speech in non-formal settings, in which organised leisure and play activities were employed as pedagogical tools to foster linguistic motivation and attachment (Guirado, 2025; Guirado & Rua, 2023; Guirado & Santos, 2024; Guirado et al., 2025). Using these categories and instruments designed around the same objectives and variables ensured coherence among tools and facilitated data triangulation (Lukas and Santiago, 2016).

3.3. Data Processing and Analysis

Quantitative data were processed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted on the questionnaire items to assess the relationships between them. Of the 28 possible correlations, 25 (89.3 %) were statistically significant, with values ranging from r = .290 to r = .654. These results demonstrate acceptable consistency among the items and confirm the conceptual validity of the questionnaire.

The suitability of the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was supported by a KMO value of .810, indicating good adequacy of the data for factor analysis. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ²(28) = 186.86, p < .001), confirming acceptable correlations among items. Cronbach’s alpha (α = .839) and McDonald’s omega (ω = .841) were calculated to assess internal coherence and reliability, both showing positive values which indicate the high reliability of the results (Rodríguez and Reguant, 2020).

Univariate analysis was subsequently performed, followed by normality and homoscedasticity tests. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (p > .05) confirmed normal distribution of the data. Independent sample tests were then conducted using Levene’s test and Student’s t-test to analyse differences by age group (8-11 / 12-15 years) and gender, as well as a stratified analysis by gender within each age group. In all cases, the effect size (Cohen’s d) was calculated to measure the magnitude of the difference.

Manual thematic coding was applied for qualitative analysis, combining inductive and deductive approaches. The deductive dimension ensured coherence across the various instruments and was based on categories used in previous research and aligned with the theoretical framework (Guirado et al., 2025). The inductive dimension was developed, reflecting both the non-formal context of the RCH and the specific profile of the children and adolescents. Data from each instrument were integrated into this process.

The same analytical procedure was followed for data obtained from the educational team, taking the interpretations of the children and adolescents as a starting point.

Overall interpretation involved cross-analysis conducted by two professionals. To ensure consistency, 20 % of the material was double-coded, achieving a high level of agreement (85 %). This initial consensus guided the application of categories to the remaining data, with revisions made when necessary. Thus, following the validation recommendations of Creswell and Creswell (2018) and understanding coding as a decision-making process (Elliott, 2018), the procedure also constituted a form of inter-rater reliability which reinforced the consistency and transparency of the analysis.

Table 2 presents the categories defined from the fieldwork.

|

Table 2. Categories Defined to Organise and Analyse the Collected Data |

||

|

Meta-Categoría |

Categorías |

Subcategorías |

|

Linguistic Motivation and Attachment: – Children and Adolescents Living in the RCH of the Gipuzkoa Child Protection System |

Emotional and Conscious Translanguaging (ECT) |

Perceived linguistic level |

|

Use of informal emotional expressionses |

||

|

Socio-educational context (RCH) |

Regulation of communicative anxiety |

|

|

Less communicative anxiety and higher motivation outside the homes |

||

|

Community bonds |

Support network with shared values |

|

|

Common linguistic and playful codes |

||

|

Sociolinguistic awareness |

Awareness of linguistic diversity and inclusion |

|

|

Educational leisure and recreational activities |

Enjoyment and positive emotions |

|

|

Gender |

– |

|

|

Age range |

||

|

Educational role models |

Importance of their role as references |

|

|

Impact of socio-educational action on the educational team |

||

|

Note: The category “gender” was included because of evidence of stronger emotional attachment to Basque among girls (Martínez de Luna et al., 2023). Source: own elaboration |

||

4. Results

To assess the impact of the programme on all participating children and adolescents, a comparative analysis was conducted by age group (8-11 and 12-15 years) and gender (participants identified themselves as girls or boys). The aim was to determine whether the perceived effect on motivation and language attachment to Basque was consistent across groups or if differences existed. No statistically significant differences were observed, either by age (t(64) = 1.121, p = .267) or by gender (t(64) = 1.071, p = .289), although slightly higher trends were observed among girls and within the younger group (d = .279; 95 % CI [-.211, .765] and d = .264; 95 % CI [-.224, .748]). The stratified analysis by age and gender confirmed this pattern, with non-significant differences and very small effect sizes (d = -.141; d = -.046). Overall, the data indicate that the perceived impact of the programme was largely homogeneous across the studied profiles.

O1: Motivation, language attachment, and RCH as Socio-educational Spaces

The EEMA questionnaire results show a highly positive evaluation from the children and adolescents, with mean scores above 3.9 across all items. This suggests a positive impact of the socio-educational action on the motivation and attachment to Basque (see Table 3).

Testimonies from the interviews confirm these findings. One educator reflected on the children’s engagement: “They clearly enjoyed themselves; they were looking forward to your visits, and they no longer perceived Basque as something negative or an obstacle. It simply came out naturally, depending on how close you were to them”.

O2: Participant Experiences and the Effectiveness of the Strategies Implemented

The impact of play (M = 4.56), the playful use of the language (M = 4.47), and the sense of belonging (M = 4.64) were particularly notable. These findings confirm the effectiveness of the playful and community-based approach (see Table 3).

In the notebooks of the children and adolescents, over 300 references were recorded relating to enjoyment, the spontaneous use of Basque, and the creation of community. The final meeting was experienced as a space of cohesion and collective pride. One of the girls commented: “Even though it is hard for me to speak it, I understand well, and we played a lot. We are all part of the Basque group”.

In individual interviews, participants highlighted the value of the community created and the experience of sharing both games and language. One girl remarked: “We all know the same words in Basque, and we play the same games-it is cool!”

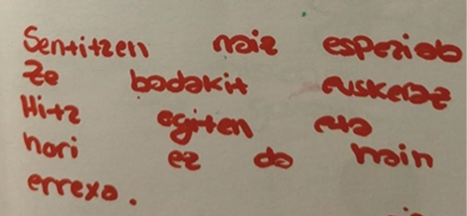

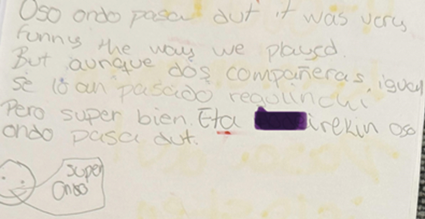

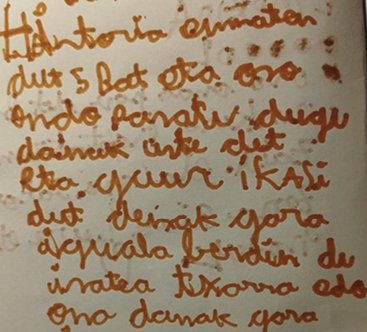

Figures 1 and 2 present excerpts from participant notebooks illustrating community value and their knowledge of Basque (see Figures 1 and 2).

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1. Note from a participant referring to community. Translation: Long live the Hari-katu community! |

Figure 2. Note from a participant about speaking Basque and feeling special. Translation: I feel special for being able to speak Basque, as it is not easy |

|

|

Source: own elaboration |

||

ECT and Organised Leisure

The focus group confirmed the usefulness of the ECT approach. Its emotional dimension was evident in everyday expressions in different languages that served to create new forms in Basque and incorporate them into the linguistic repertoire: “Jaitsi bi!” (Come down, you two!), “Zure aurpegian!” (In your face!), “Kaka zaharra!” (Old rubbish!), “Hoi makina!” (You’re amazing!)

Children and adolescents also emphasised the central role of emotions. One educator summarised it as follows: “Emotions are the key. It is interesting how you bring them to Basque from that place without saying anything to them”.

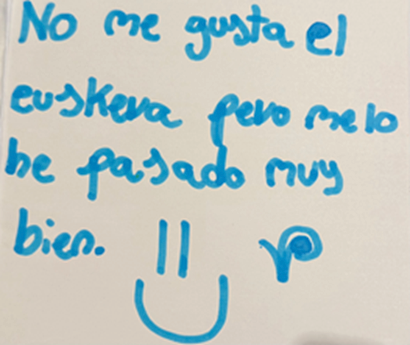

In the same vein, the reflection notebooks (Figures 3 and 4) illustrate the use of translanguaging to express enjoyment and value participants’ own languages. They also show how the programme generated positive experiences among those who were initially reluctant to use Basque.

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 3. Note for children and adolescents: enjoyment, translanguaging. |

Figure 4. Note for children and adolescents: enjoyment and happiness. |

|

|

Source: own elaboration |

Socio-educational Spaces

Several participants noted that playing outdoors helped them to feel more confident in Basque and reduced communicative anxiety. One participant explained: “When you play, it goes away; you feel happier, freer”. Questionnaire responses supported this perception, reflecting greater ease in using Basque in outdoor spaces while playing.

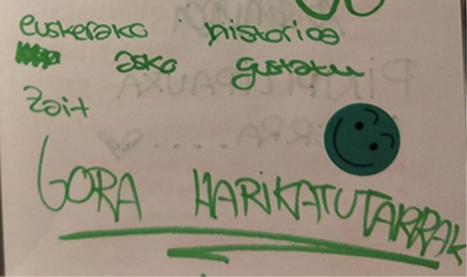

Sociolinguistic Pedagogy and the HK Community

The sociolinguistic dimension emerged spontaneously in the interviews and in 35 participant notebook entries. One boy remarked: “We have to try to make sure Basque does not suffer anymore, nor any other small language”. Another reflected on Wolof: “I had never played or thought about anything from my own language”, due to his family’s concern that he might forget his own language when learning Basque.

Overall, the reflections of the children and adolescents reveal a sociolinguistic awareness linked to enjoyment, community, and equality (see Figures 5 and 6).

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 5. Participant note: sociolinguistics and community. |

Figure 6. Participant note: sociolinguistics, enjoyment, and values of equality. |

|

|

Source: own elaboration |

||

O3: Impact of the Programme on the Educational Team

The interviews, notebooks, and field notes of the educational team highlighted “the games” and the shared experience of Harikatutarrak. Team members particularly valued the connection created, the motivation, and the progressive increase in the spontaneous use of Basque. One educator summarised this impact: “Most of us have become more aware, and it has been interesting to see how those of us who did not know Basque were reminded by the children and adolescents how to say certain expressions”.

Nevertheless, the field notes also revealed differences in professional engagement. In some cases, a lack of emotional support and an authoritarian style were observed, whereas in others, a committed attitude fostered enthusiasm and pride among the participants. These contrasts underline the important role the educators play as well as their pedagogical perspective in the development of the programme.

Although linguistic competence was not formally assessed, both the educational team and the children and adolescents perceived greater ease and fluency in the spontaneous use of Basque. These perceptions suggest an enrichment of the informal linguistic repertoire and a reduction in communicative anxiety, contributing positively to motivation and attachment to the language.

5. Discussion

The results demonstrate the positive impact of the Hari-Katu programme on the children and adolescents. It has fostered emotionally meaningful experiences around the Basque language and enhanced motivation and language attachment through shared enjoyment, affective expression, and a sense of community. These findings are consistent with previous studies by Guirado et al. (2025a, 2025b) and Miguelena et al. (2024).

Among the strategies implemented, the creation of a linguistic and emotional community–the Harikatutarrak–was especially valued. This network promoted group cohesion through affective bonds, shared linguistic codes, and collective games (Guirado & Rua, 2023; Koppen et al., 2019). The results also suggest that the socio-educational experience has contributed to establishing new peer reference relationships, thereby providing a strong foundation for future interventions aimed at strengthening the social networks that are so essential for this group (Emond, 2014; De-Juanas et al., 2022).

As highlighted in previous studies (Guirado, 2025; Guirado & Santos, 2024; Guirado et al., 2025), organised leisure has created affective spaces for the use of Basque, acting as both an emotional and linguistic driver. Outdoor play has helped to reduce communicative anxiety through positive emotions and increased motivation (Ramos and Maya, 2022). The results obtained in the RCH of Gipuzkoa represent a novel contribution, as no similar research has been identified within the child and adolescent protection system (Miguelena et al., 2024, 2025) outside this research framework (Guirado et al., in press).

The ECT approach has helped the children and adolescents to express themselves through their own linguistic and affective repertoires (Guirado et al., in press). It creates safe and emotionally positive spaces that are essential for learning and for the internalisation of the L2 (Dewaele and Sanz-Ferrer, 2022; Sah et al., 2025).

The testimonies and evaluation notes indicate that this approach integrates body, culture, and relationships through a sensitive pedagogy that pays attention to the senses and emotions during educational guidance (Planella, 2014). Consequently, these residential care units, positioned between formal education and informal family education, can serve as conducive spaces for fostering minority language, in this case, Basque (Miguelena et al., 2024; Guirado et al., 2025a, 2025b).

In this framework, the L1s of the participants were recognised and legitimised. By placing them in dialogue with Basque, the programme has promoted both linguistic justice and community cohesion from a decolonial and intersectional perspective (Dovchin, 2025; Meighan, 2025). Similarly, the perspective of sociolinguistic pedagogy (Silva and Borba, 2024; Ortega, 2024) provided an appropriate framework for promoting linguistic and identity awareness, as illustrated by one participant’s reflection on Wolof (Guirado et al., 2025).

Although the linguistic competence of the participants was not directly assessed, the EEMA questionnaire and the testimonies suggest that the programme has enriched their linguistic repertoires (Orcasitas-Vicandi y Perales, 2020). In this line, the results highlight the value of organised leisure and non-formal education in developing informal speech in Basque (Guirado y Rua, 2023; Guirado y Santos, 2024).

Previous studies have reported a stronger attachment to the Basque language among girls (Martínez de Luna et al., 2023), yet no significant differences in terms of age or gender were observed in this study regarding motivation or linguistic attachment. This suggests that the experience was perceived as positive and inclusive by all participants (Guirado et al., 2025). The results reflect the intersectional and decolonial perspective underpinning the programme (Prado-Pereira, 2024). This approach addresses individual needs and promotes equity among the participants, regardless of gender, identity, cultural background, or socioeconomic status, the latter being a shared characteristic of the group (Dovchin, 2025; Meighan, 2025; Prado-Pereira, 2024).

Finally, the findings highlight the importance of the educational team, particularly its affective involvement and conscious guidance in the well-being and development of participants (De-Juanas et al., 2022; Moreno & García, 2009), and in their linguistic socialisation (Burdelski, 2020; Kasares, 2023). The centrality of the reference team is also emphasised, as it lies at the heart of the pedagogical action (Fernández-Simo & Cid, 2017) and plays a key role as a linguistic model (Guirado & Rua, 2023).

6. Limitations and Future Lines

The geographical dispersion of the RCH, the diversity of ages, and the complex emotional situations made data collection challenging, although these same factors also enriched the sample. The spontaneous responses and testimonies revealed a genuine connection with Basque and the community as well as a sense of belonging.

Among the main limitations, the demands of the ECT approach are noteworthy, as it requires professionals trained in educational leisure, linguistic games, and a high level of pedagogical awareness. This makes implementation difficult in contexts with less preparation or weaker attachment to Basque.

As a future line of work, a stable plan for linguistic socialisation is proposed, based on organised leisure and positive emotions, reinforcing both the right to leisure and linguistic inclusion. This pathway opens up new opportunities for research in RCH within the Basque Autonomous Community (BAC) and in other leisure programmes for minority languages, including experimental studies that quantify impact beyond perception.

Nevertheless, not pursuing this route in the present study was a conscious decision, aimed at giving voice to participants’ experiences and avoiding the influence of uncontrollable variables in a pre-post test design.

7. Conclusions

The Hari-Katu programme has offered a meaningful socio-educational experience in which Basque has been approached as a language, an affective bond, and a community practice. Organised leisure, the ECT approach, and the involvement of the educational team have encouraged its spontaneous use and reduced communicative anxiety.

Children and adolescents of different ages and genders experienced this process positively, reinforcing its value as an inclusive and intersectional proposal. The experience has also had a positive impact on the educators, strengthening their linguistic and emotional awareness as well as their role as role models in social education.

Taken together, these results show that RCH can serve as valuable environments for promoting Basque through affectivity, supporting holistic development, and fostering the social inclusion of children and adolescents within the Basque-speaking community. In this process of linguistic socialisation, children and adolescents have emerged as active agents in the revitalisation of the language.

Contributions (CRediT Taxonomy)

|

Contributions |

Authors |

|

Conceptualisation and design of the study |

Author 1 |

|

Literature review |

Author 1 |

|

Data collection |

Author 1 y Author 4 |

|

Data analysis and critical interpretation |

Author 1, Author 2 y Author 3 |

|

Results |

Author 1 |

|

Discussion |

Author 1 |

|

Revision and approval of versions |

All authors |

Financing

This project has been awarded and financially supported by the Euskaltzaindia (Royal Academy of the Basque Language).

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We express our deepest gratitude to the Department for Child and Adolescent Protection of the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa, as well as to the organisations managing the residential care homes, for their invaluable support; to Euskaltzaindia (Royal Academy of the Basque Language) for its endorsement and promotion of this research project; to the association HeziZerb for its collaboration through the EmoziOn! educational materials and the training provided; and, above all, to the children, adolescents, and educators who participated, whose commitment and dedication have made this research possible.

Bibliographical References

Artetxe M., Bereziartua, G., & Burreso, N. (2024). Oral language competence in the informal context and the use of language among family and friends: a quantitative study in the university context of young college students, Euskera Ikerketa Aldizkaria, 69(1), 49-78. https://doi.org/10.59866/eia.v1i69.274.

Burdelski, M. (2020). Emotion and affect in language socialization. In S. Ervin-Tripp, J. Fenigsen, y J. M. Wilce (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language and emotion (pp. 28-48). Routledge.

Caillois, R. (1992). Les jeux et les hommes. Folio Essais.

Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2023). Second language acquisition and minority languages: An introduction. In J. Cenoz y D. Gorter (Eds.), The minority language as a second language (pp. 1-15). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003299547

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Dat, M. A., Guedat-Bittighoffer, D., & Starkey-Perret, R. (2024). L’acquisition formelle de l’oral spontané en L2 des locuteurs débutants. SHS Web of Conferences, (168), 10005. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/202419110005

De-Juanas Oliva, Á., Díaz-Esterri, J., García-Castilla, F. J., & Goig-Martínez, R. (2022). La influencia de la preparación para las relaciones socioafectivas en el bienestar psicológico y la autonomía de los jóvenes en el sistema de protección. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, (40), 51-66. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2022.40.03

Dewaele, J.-M., & Sanz Ferrer, M. (2022). Three entangled foreign language learner emotions: Anxiety, enjoyment and boredom. ELIA: Estudios de Lingüística Inglesa Aplicada, (22), 237-250. https://doi.org/10.12795/elia.2022.i22.08

Díaz, I. G. (2012). El juego lingüístico: una herramienta pedagógica en las clases de idiomas. Revista de Lingüística y Lenguas Aplicadas, (7), 97-102. https://doi.org/10.4995/rlyla.2012.947

Dovchin, S. (2025). Beyond linguistic racism: Linguicism and intersectionality among Mongolian-background postgraduate female students in Australia. Urban Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420859251331555

Elliott, V. (2018). Thinking about the coding process in qualitative data analysis. The Qualitative Report, 23(11), 2850-2861. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2018.3560

Emond, R. (2014). Longing to belong: Children in residential care and their experiences of peer relationships at school and in the children’s home. Child y Family Social Work, 19(2), 194-202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2012.00893.x

Fernández-Simo, D., & Cid, X. M. (2017). Repensar la calidad en el proceso de acompañamiento socioeducativo con infancia y adolescencia en protección: Retos pendientes desde la Educación Social. RES. Revista de Educación Social, (25), 284-300.

Gallardo-Masa, C., Sitjes-Figueras, R, Iglesias, E. & Montserrat, C. (2023). How Adolescents in Residential Care Perceive their Skills and Satisfaction with Life: Do Adolescents and Youth Workers Agree? Child Indicators Research, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-023-10090-6

García-Castilla, F. J., Melendro, M., & Blaya, C. (2018). Preferencias, renuncias y oportunidades en la práctica de ocio de los jóvenes vulnerables. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, (31), 21-32. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2018.31.02

Germain, C., & Netten, J. (2012). A new paradigm for the learning of a second or foreign language: The neurolinguistic approach. Neuroeducation, 1(1), 85-114. https://doi.org/10.24046/neuroed.20120101.85

Guirado, O. (2025). Arikala: organised leisure and the practice of informal Basque speech in a formal educational context. Euskera Ikerketa Aldizkaria, 70(2). https://doi.org/10.59866/eia.v2025i10.304

Guirado, O., Dosil-Santamaria, M., & Miguelena, J. (2025a). Emotional and conscious translanguaging in non-formal education: Linguistic socialisation in residential care homes and minority language settings. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2025.2579841

Guirado, O., Miguelena, J., & Dosil-Santamaria, M. (in press/a). Euskararen hizkera informala eta aisialdi antolatua Gipuzkoako haur eta nerabeen babeserako egoitza-harreretan; ikuspegi dekolonialetik eta intersekzionaletik abiatutako ikerketa aplikatua. Euskera Ikerketa Aldizkaria.

Guirado, O., Miguelena, J., & Dosil-Santamaria, M. (2025b). Formal education, organised leisure, and informal discourse in Basque: Improving the linguistic proficiency of second language Basque learners and fostering motivation and attachment to the language. Language, Culture and Curriculum. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2025.2516006

Guirado, O., & Rua, J. (2023). Pulunpa (e)ta Xin! reception and immersion plan for foreign students: Pedagogical intervention action study. Euskera Ikerketa Aldizkaria, 68(2), 41-86. https://doi.org/10.59866/eia.v2i68.265

Guirado, O., & Santos, A. (2024). Communication anxiety, formal education and the teaching and learning of informal Basque speech. Fontes Linguae Vasconum, (138), 587-616. https://doi.org/10.35462/flv138.7

Huizinga, J. (2012). Homo ludens. Alianza Editorial. (Trabajo original publicado en 1938).

Ismoyo, A. N., Hermawan, H. A., & Ihsan, F. (2024). Health benefits of traditional games: A systematic review. Retos, (59), 843-856. https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/retos/index

Iurrebaso, I., & Goikoetxea, G. (2025). Esnatu ala hil: Euskararen oraina eta geroa, diagnostiko baten argitan. Elkar.

Kasares, P. (2023). Intergenerational continuity of the Basque language beyond family transmission. Eusko Jaurlaritza.

Koppen, K., Ernestus, M., & Van Mulken, M. (2019). The influence of social distance on speech behavior: formality variation in casual speech. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory, 15(1), 139-165. https://doi.org/10.1515/cllt-2016-0056

Lazpiur, I., Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Dosil-Santamaria, M., Eiguren Munitis, A., & Fernández Rotaeche, P. (2025). Estudio de los patrones de apego de los niños y las niñas bajo tutela: Un análisis desde la perspectiva de educadores sociales. Educació Social. Revista d’Intervenció Socioeducativa, (85), 13-27. https://doi.org/10.60940/EducacioSocialn85id431824

Lukas, J. F., & Santiago, K. (2016). Educational evaluation. UPV-EHU.

Martinez de Luna, I., Iñarra, M., & Suberbiola, P. (2023). Language proficiency and language use in Basque as first or second language. In J. Cenoz y D. Gorter (Eds.), The minority language as a second language (pp. 1-15). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003299547

Masruroh, D., Aridah, A., & Rusmawaty, D. (2025). Foreign language anxiety and its impact on English achievement: A study of gender variations in EFL learners. Voices of English Language Education Society, 9(1), 86-95. https://doi.org/10.29408/veles.v9i1.28279

Meighan, P. J. (2025). Decolonizing language education. En C. A. Chapelle (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics (2.ª ed.). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal20412

Miguelena, J., Guirado, O., & Dosil-Santamaria, M. (2024). Reception centres in the protection system of Gipuzkoa: Basque, the experiences of formerly protected people and linguistic rights. Fontes Linguae Vasconum, (138), 563-585. https://doi.org/10.35462/flv138.6

Miguelena, J., Rodriguez, A., & Guirado, O. (2025). Trayectorias educativas de los y las adolescentes y jóvenes en el sistema de protección de Gipuzkoa: Nuevos retos. Arxius de Ciències Socials, (51), 22-41. https://doi.org/10.7203/acs.51.30331

Montserrat, C., Delgado, P., Garcia-Molsosa, M., Carvalho, J. M. S., & Llosada-Gistau, J. (2021)., &oung teenagers’ views regarding residential care in Portugal and Spain: A qualitative study. Social Sciences, 10(2), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10020066

Moreno, J. M., & Garcia, M. E. (2009). Adaptación y desarrollo lingüístico en niños víctimas de maltrato. Boletín de Psicología, (96), 17-34.

Negård, I.-L., Ulvik, O. S., & Oterholm, I. (2020)., &ou and me and all of us: The significance of belonging in a continual community of children in long-term care in Norway. Children and Youth Services Review, (118), 105352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105352

Oakley, G., Steele, C., Robinson, C., Dobinson, T., Dovchin, S., & Cumming-Potvin, W. (2025). Towards a playworld translanguaging approach in early childhood education. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1075/aral.24132.oak.

Okland, I., & Oterholm, I. (2022). Strengthening supportive networks for care leavers: A scoping review of social support interventions in child welfare services. Children and Youth Services Review, (138), 106502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106502

Orcasitas-Vicandi, M., & Perales, A. (2020). Multilingüismo e identidad: Poniendo en valor el conocimiento del alumnado. Textos de Didáctica de la Lengua y la Literatura, (90), 55-60.

Ortega, A. (2024). Sociolinguistic Awareness in Education: Preface, BAT soziolinguistika aldizkaria 131(2). 7-10. https://doi.org/10.55714/BAT-131

Planella, J. (2014). El oficio de educar. Editorial UOC.

Prado-Pereira, A. (2024). Pedagogical translanguaging: A systematic literature review of a new didactic theory and its application in primary education classrooms. Didáctica: Lengua y Literatura, (36), 191-200. https://dx.doi.org/10.5209/dill.98421

Ramos, D., & Maya, Y. (2022). Los juegos tradicionales y la motivación por el aprendizaje del idioma inglés. Sociedad y Tecnología, 5(3), 565-576. https://doi.org/10.51247/st.v5i3.265

Reckmeyer, G. (2023). Translanguaging as pedagogy on the south side of Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Potential, barriers, and next steps. Documentos de Traballo en Ciencias da Linguaxe: DTCL, (4), 83-120.

Rodríguez, J., & Reguant, M. (2020). Calculate the reliability of a questionnaire or scale using SPSS: Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. REIRE Revista d’Innovació i Recerca en Educació, 13(2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1344/reire2020.13.230048

Rodríguez, Y. (2021). Juegos verbales como estrategia para mejorar la expresión oral en el idioma inglés en estudiantes del primer año de educación secundaria. Revista Educación, (19), 165-181. https://doi.org/10.51440/unsch.revistaeducacion.2021.19.199

Sah, P. K., Mathukar, K. C., & De Costa, P. (2025). Considering emotions as entanglements in applied linguistics. International Journal of Applied Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12720

Sala-Roca, J. (2019). Professional parenting in institutional care: A proposal to improve care for children in care centers. Pedagogía Social: Journal of Research in Social Pedagogy, (34), 98-109. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2019.34.07

Shimomura, Y. (2023). The definition of play: A measurement scale for well-being based on human physiological mechanisms. Sustainability, 15(13), 10725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310725

Silva, D. N., & Borba, R. (2024). Sociolinguistics of hope: Language between the no-more and the not-yet. Language in Society, 53(5), 775-790. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404524000903

Singer, R. (2018). A small speech community with many small languages: The role of receptive multilingualism in supporting linguistic diversity at Warruwi Community (Australia). Language y Communication, (62), 102-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2018.05.002

Zhao, X., & Xu, R. (2024). Trends and challenges in mixed methods educational research: A comprehensive analysis of empirical studies. International Journal of Asian Education, 5(4), 262-273. https://doi.org/10.46966/ijae.v5i4.450

HOW TO CITE THE PAPER

|

Guirado, O., Miguelena, J., Dosil-Santamaría, M. y Rodríguez, A. (2026). Hari-Katu: basque as language, emotion, and community in residential care homes for children and adolescents in the protection system. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 48, 97-112. DOI:10.7179/PSRI_2026.48.06 |

AUTHOR’S ADDRESS

|

Odei Guirado. Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, UPV/EHU. Departamento de Ciencias de la Educación. Tolosa Hiribidea, 70, 20018 Donostia, Gipuzkoa. E-mail: odei.guirado@ehu.eus Joana Miguelena. Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, UPV/EHU. Departamento de Ciencias de la Educación. Tolosa Hiribidea, 70, 20018 Donostia, Gipuzkoa. E-mail: joana.miguelena@ehu.eus María Dosil-Santamaría. Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, UPV/EHU. Departamento de Ciencias de la Educación. Santsoena, Bizkaia, Barrio Sarriena s/n 48940. E-mail: maria.dosil@ehu.eus Aintzane Rodriguez. Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, UPV/EHU. Departamento de Ciencias de la Educación. Tolosa Hiribidea, 70, 20018 Donostia, Gipuzkoa. E-mail: aintzane.rodriguez@ehu.eus |

ACADEMIC PROFILE

|

ODEI GUIRADO https://orcid.org/0009-0007-5205-4595 Lecturer at the Faculty of Education of the University of the Basque Country / Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (UPV/EHU) and doctoral candidate in the Language, Culture and Education programme at the same university. His academic work connects non-formal education, sociolinguistics, and the defence of children’s and adolescents’ linguistic and cultural rights. He has coordinated several projects aimed at promoting the Basque language through educational leisure and has authored various scientific publications in high-impact journals. His research career has been recognised on several occasions by Euskaltzaindia (Royal Academy of the Basque Language). JOANA MIGUELENA https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7467-1291 PhD in Education and lecturer at the Faculty of Education of the University of the Basque Country / Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (UPV/EHU). She is a member of the research group IkasGaraia: Education, Culture and Sustainable Development. Her research focuses on the rights of children and adolescents, particularly those living in residential care; the transition to adulthood of those leaving protective measures; educational pathways; and social networks among young people in residential care. She has participated in various competitive, territorial, national, international, and private research projects. She is the author and co-author of publications in several high-impact journals and book chapters, and has also coordinated three edited volumes. MARÍA DOSIL SANTAMARIA https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8805-9562 Lecturer in the Department of Educational Sciences, in the section of Research Methods and Diagnosis in Education, at the Faculty of Education in Bilbao, University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU). She holds a PhD from the programme in Educational Psychology and Specific Didactics (UPV/EHU). She has participated in more than fifteen research projects and has authored over sixty publications. Her current h-index is 24. AINTZANE RODRIGUEZ POZA https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0959-6547 PhD in Education from the School, Language and Society doctoral programme and graduate in Pedagogy, she is currently a lecturer at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU). She is a member of the research group IkasGaraia: Education, Culture and Sustainable Development. Most of her scientific work focuses on the protection of children and adolescents under residential care measures, the analysis of educational pathways and the factors influencing them, and the transition to adulthood, among other topics. |