Migrant children’s well-being depends largely on their integration process and the opportunities in place to promote positive legal, economic, educational, and psychosocial outcomes (Harttgen & Klasen, 2009). Children and young people, with a joint share of approximately 17%, represent a fair portion of the European international migrant population (UNDESA, 2020). In this context, European states are increasingly taking into account the benefits of this diversity for their socioeconomic functioning and social cohesion, as well as acknowledging the current and potential contribution that migrant children can make to the sustainable development of their host countries and their countries of origin (European Commission, 2017; Kuschminder et al., 2018)

The challenge of migrants’ effective integration has become a pillar of European politics and governance explicitly expressed in the European Union’s strategic goals for sustainable development (European Commission, 2020). In practice, targeting migrant children’s effective integration has meant formulating broad policy frameworks that define actions to improve children’s well-being through cross-cutting interventions influencing educational inclusion, socio-emotional development and social cohesion (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2019). Consequently, policymakers have relied upon researchers to investigate the most efficient mechanisms to foster these children’s integration and obtain key clues for promoting positive personal and social development (European Commission, 2022). However, research on migrant children’s well-being and integration is not exempt from challenges.

The scientific knowledge on child well-being (CWB) and integration is usually not well enough connected, and the studies with migrant children tend to focus on either integration or CWB outcomes, disregarding essential theoretical and empirical contributions from one another (Harttgen & Klasen, 2009). On the one hand, the literature about CWB focusing on migrant children is largely dedicated to the adverse mental health outcomes of forced migration on refugee and asylum-seeking children in traditional migration-receiving countries (Bajo Marcos et al., 2021a). Some empirical studies in this area have nonetheless documented the impact of migration on the well-being of children and adolescents more generally, and how integration programs (or their absence) impact migrant children’s well-being outcomes in particular (Chang, 2019; Hadfield et al., 2017; Ost et al., 2004). On the other hand, the literature about migrant children’s integration still presents significant gaps relative to the absence of common theoretical frameworks, available data, and insufficient coverage of migrant children’s heterogeneity (Bajo Marcos et al., 2021a). The area is nevertheless living a critical breakthrough: with the adoption of more child-centred approaches, the literature has passed from prioritising adult-focused dimensions - such as the families’ economic and labour processes, culture and identity aspects - to pay more attention to children’s outcomes in education, satisfaction with life or relationships and belonging, as equally relevant dimensions of children’s integration (Martin et al., 2019).

This paper aims to provide a theoretical framework explaining migrant children’s well-being and integration based on a narrative review of the state-of-the-art research in migrant children’s well-being and integration. In so doing, we adopt a) the Convention on the Rights of the Children’s definition of a child as “every human being below the age of eighteen years unless, under the law applicable to the child, the majority is attained earlier” (United Nations, 1989); and b) the IOM definition of a migrant as an umbrella term, generally referring to every human being moving away from their place of residence 1 (IOM, 2019). We present current models that meaningfully influence research in each area and consider the commonalities and potential links between both bodies of literature with an applied perspective. Finally, we provide a theoretical framework that structures the main theories explaining the interaction of well-being and integration processes of migrant children and their application in current research.

Methodology

Narrative reviews or non-systematic reviews are a specific type of review design that provides a comprehensive synthesis of the knowledge about a subject, delving into the theoretical constructs and contextualizing the evidence derived from contrasting methodological approaches (Baumeister & Leary, 1997). Best practice recommendations on review designs encourage authors to conduct narrative reviews, justifying their pertinence to inform research with an in-depth qualitative synthesis of a particular topic that outperforms the specific nature of systematic reviews (Siddaway et al., 2019). Typically, narrative reviews present a broad approach and the source’s identification, selection, screening, and eligibility of sources is based on the expertise of the authors.

This review adopted a broad approach, including different types of sources spanning journal articles, books and book chapters, official operative reports from institutions and political resolutions committing the international community. Eligible documents could involve theoretical and empirical research and no time limit was enforced. The criteria for inclusion for theoretical appraisal was based on a) the coverage and link to the targeted topics (child well-being and integration of children with a migrant background) and b) the relevance of their contribution to theory, empirical application, or policy development. Coverage was defined based on the intersection of the topics as “full” if the source tackled both topics, “partial” if only covered one and “out of the focus” if it provided foundational knowledge influencing current research in either one of the topics without specifically focusing in neither of them. Relevance was operationalised based on the theoretical and/or applied contribution of each source in a scale from “very low” to “very high”, in which the sources with both theoretical and applied contribution and with a broad applied scope were the most highly considered. The impact was analysed categorising from “low” to “extremely high” impact the number of cites of each document in google scholar, as it is the only database available capturing citations from different kinds of sources. The year of publication was also taken in account, considering that earlier publications usually take two to three years to cumulate citations (Soldati, 2023).

In total 103 documents were selected for appraisal following these criteria and ultimately contributed to the narrative review and the development of the theoretical framework. Most of them (n=72) are pertinent and (highly) relevant, and around the half of them fully cover the topics (n=47) (Table 1). The fact that around a half of the sources appraised were published within the last five years accounts for the growing interest in these areas and specialised topics (Table 2).

Table 1 Summary of selected sources for discussion

Table 2 Impact and years passed from publication

Current models of CWB and migrant children

There is no consensus for a unique and operationalised definition of well-being. The term cross-cuts with other closely related constructs (e.g., happiness, health, quality of life, etc.), usually relying upon the definition of constituent domains and dimensions rather than providing a holistic understanding of what it means “to be well” for people. In this regard, well-being definitions tend to differ depending on the level of analysis adopted by the authors (Dodge et al., 2012). Macro perspectives tend to consider well-being from a more structural approach. The concept of well-being under these perspectives usually refers to a proxy of the aggregated conditions in which the individual lives and consider material well-being as a continuum from poverty (or ill-being) to well-being (Kern et al., 2015). Consequently, the measures of well-being under these perspectives are multi-component and composed of objective indicators such as household income, consumption, deprivation, housing quality, etc. (Holder et al., 2011). Alternatively, micro perspectives of well-being tend to adopt humanist approaches, emphasising the need to incorporate people’s perceptions of their own lives as well as the effect of the environment on the individual’s physical, mental and social functional state (Diener et al., 2018; Ryff, 2014). These perspectives tend to accept holistic definitions of well-being, such as the constructs of (hedonic) subjective well-being (Diener et al., 1999) or (eudaimonic) psychological well-being (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). Accordingly, the measures of well-being under these perspectives tend to incorporate subjective and self-reported indicators about life satisfaction, positive and negative affect, social support, etc. (Seligman, 2018). As a result, the more influential theoretical definitions of well-being have been proposed for adults from intradisciplinary perspectives and without an in-depth analysis of the influence of the proximal communities at a midrange level.

CWB literature has outgrown these definitions by incorporating a bio-ecological and rights-based conceptual framework (Ayala-Nunes et al., 2018). Authors have reached an agreement emphasising how well-being emerges across interactions at different ecological levels and the influential role of children’s agency in these exchanges (Ben-Arieh & Attar-Schwartz, 2013). This developmental and ecological perspective is a distinctive aspect of the CWB literature that contrasts with the general literature on well-being and contributes to filling the research gaps at the meso-level analysis by attending to the role of communities and caregivers in the CWB outcomes (Minkkinen, 2013). Additionally, the contributions in terms of children’s participation and empowerment from childhood studies and child indicators research helped to address the social needs of children and to better define the real conditions and opportunities for children’s functioning and capability building (Ben-Arieh et al., 2014; Bradshaw & Richardson, 2009). Consequently, CWB literature has thereby reached a consensus to conceptualise well-being of children as holistic, multidimensional, dynamic and addressing the children’s capabilities for developing and engaging appropriately with their environment (Raghavan & Alexandrova, 2015).

This child-centred approach balances the emphasis on the children's material, social and personal resources and their interplay with the environment, focusing on them as a special population (Ben-Arieh, 2008a). For instance, Veenhoven (2005) discusses the implications of social inequality on the national outcomes of children’s happiness deeply; Camfield et al. (2009) also discuss the influence of poverty in youths’ well-being results carrying out longitudinal research that highlighted the critical role of the minors’ views of their own well-being; finally, Minkinnen (2013) proposed a structural model pointing to actual mechanisms underlying child well-being across interactions at all ecological levels. In conclusion, the study of CWB in the last decades has revealed the crucial contribution of children’s subjectivity to understanding how well-being emerges as a functional outcome of the interaction between the individual and its context, which is to highlight the dynamic, interactive and social-constructive nature of well-being (Minkkinen, 2013).

However, the applicability of the previous models is yet to be assessed with migrant children’s populations (Fattore et al., 2019). Besides, applied to migrant children, understanding CWB involves considering how integration processes and the acculturation experience intersect for them (Schachner et al., 2017). Although previous empirical studies have provided some evidence about this relationship, they do not adhere to a common theoretical framework explaining the connections between integration processes and CWB (Correa-Velez et al., 2010; Perreira & Ornelas, 2011). Despite this lack of common theoretical grounds, a similar range of outcome measures is nonetheless consistently used across both streams of studies with this population, frequently including variables of interest within the psychological well-being construct such as subjective well-being, social well-being, self-esteem, sense of belonging, happiness, etc. (Bajo Marcos et al., 2021a).

Current models of the integration of migrant and refugee minors in Europe

European sociologists have broadly defined integration as “the process of becoming an accepted part of society” (Penninx & Martiniello, 2006, p. 127). Still, the understanding of integration processes is a contested matter 2 that can be nuanced by looking at who are the parties involved, which are the relations in place, and which is its function (Zisakou & Figgou, 2021). This way, integration can be understood as a process emerging from intergroup relations that encompasses recognising two differentiated groups: natives and migrants. The relationships between these two groups engage the natives and migrants in a transformative interaction that bilaterally shapes their social categorisation, memberships 3 , and (ultimately) identities, whether collectively between their own groups or individually between members from the same group (IOM, 2019). These processual elements account for the more psychosocial aspects of integration. On the one hand the social nature of the process relates to achieving a sense of social cohesion among the individuals, their communities and the institutions that invest in building trustful, solidary, and accepting bonds in inter and intragroup relationships (Dragolov et al., 2014). On the other hand, the psychological nature of the process relates to the individual adjustment over time and to the processes of acculturation and identity formation in the new society (Berry et al., 2006; van Doeselaar et al., 2018).

The function of integration is to incorporate new members into a given society; it is, therefore, a cooperative process aimed at negotiating differences and the inequality derived from it and making available to newcomers equal opportunities, rights and resources to become full members of the host society (Council of European Union the, 2004). In this way, integration is always dynamic and contextualised in space, time and culture, affecting individual, sociocultural, economic, and political spheres (Pastore & Ponzo, 2016). These functional elements relate to the institutional aspects of the integration process and its political implications in terms of the rights, commitments and obligations acquired by each part. This means, in the first place, that integration is an uneven interaction due to the differential power and roles that determine the results of the integration process, and in the end, that the receiving societies are the ones creating the opportunities and operative courses of action that migrants can undertake (Penninx, 2019). An example of this aspect in European countries is that they operate differential pathways for the integration of European citizens migrating within Europe vs. Third Country Nationals (TNCs).

The European Union represents a singularly unique and complex context in which integration policy and operational pathways are multi-level and multi-stakeholder (Caponio & Jones-Correa, 2017). From a comparative perspective, the European Union represents an exceptional international actor that has managed to achieve a sustained evolution of expansion, integration and institutionalisation over fifty years. In this context, intercultural dialogue is essential to foster social cohesion by sustaining positive interactions between the welcoming society and migrants (Council of Europe, 2008). Not in vain, the European Union creation responded to the aim of promoting peace-building, social cohesion and prosperity of its citizens in reminiscence of the devastation caused by the Second World War (Amato et al., 2019). The adoption and promotion of these foundational European values is part of the own success history of sustainability of the European project that makes it different from other comparable international initiatives: the integration strategy of the Union relies on interculturalism, the diffuse power exertion through the acceptance of its normative agenda and the attraction of EU membership (Haukkala, 2008).

Intercultural models of integration typically adopt dynamic conceptions of culture and societies, acknowledge diversity, and consider it a valuable resource and a strength. However, the most significant feature of interculturalism is that it seeks to promote the creation of liminal spaces of exchange and interaction among people as assets of potential transformative social processes (Barrett, 2013). Hence in terms of integration policy (and processes) at the European level, interculturalism is a central mechanism for social cohesion and resides in the core of its values, identity, and purpose.

Research about how integration policies contribute to positive integration processes in Europe highlights the need to consider other policy frameworks regulating broader institutions and social services, and the need to foster an organised and flexible implementation in practice (Penninx & Garces Mascarenas, 2016). These results are, if possible, even more relevant in the case of migrant children. As migrants and children, they cannot be appropriately understood regardless of their educational and developmental contexts, the orientation towards the inclusion of their proximal communities and the more extensive processes and structures of the society in which they live (Jalušič & Bajt, 2022). As a result, recent research on migrant children’s integration is leaning upon adopting more child-centric frameworks with the double aim of on the one hand understanding the different needs 4 to be addressed from a policy-making and governance approach, and of developing practical courses of action leading to positive integration and well-being outcomes on the other hand (Adserà & Tienda, 2012).

Migration policies are usually formulated from the point of view of receiving states, thus putting first the countries’ interests in terms of border control and social provision. Conversely, adopting a more child-centric approach to integration allows connecting with the children’s individual needs and rights, better allocating political drive and effective integration measures to crucial aspects that ease their inclusion in the host society (Gornik, 2020). Specialised research with this child-centred approach has revealed that, in this specific population, the results of the integration process are best observed across five dimensions of children’s outcomes: access to rights, language and culture, subjective well-being and social connectedness, and educational achievement (Serrano Sanguilinda et al., 2019). These results are in line with the worldwide strategies for mental health promotion which underline considering the cultural background of migrant and refugee children and respecting their resilience mechanisms as prerequisites that affect national well-being and quality of life outcomes (WHO, 2005). Additionally, they have permitted to clarify and better link the overlap in defining migrant and refugee children’s integration and socio-educational inclusion (Bajo Marcos et al. , 2021b).

Conceptual bridges across literature: a child-centred approach to the matter

Addressing migrant children’s inclusion while still safeguarding their well-being requires adopting a comprehensive perspective towards children. The trends in both research areas converge into adopting a child-centred approach that effectively puts them in centre of the social analysis and research inquiry (Sedmak et al., 2021). Child-centredness has a long tradition in pedagogy, especially in the western contexts, where the notion of children as autonomous creative learners whose development should be stimulated to reach their top potential is a fundamental cornerstone for instruction and education. This approach stems from pedagogical postulates of the late nineteenth century and nurture from social constructivist perspectives of child development proposed in the twentieth century (Ang, 2016). In line with the philosophical postulates of child-centredness, a child-centred approach applied to the integration and well-being of migrant children builds upon three pillars: being holistic, intersectional, and change-responsive.

The first pillar, understanding children in a holistic way, means acknowledging that humans are biopsychosocial beings whose individual outcomes are shaped by their interaction with the social structure in which they live (Minkkinen, 2013). Applying this principle to conceptualising the integration and well-being of migrant children means considering multidimensional and multi-level factors (Amerijckx & Humblet, 2014). Firstly, regarding personal variables, previous studies have pointed at some personal traits as internal dispositions leading to better adjustment and fostering positive integration and well-being outcomes, such as self-esteem, resilience, sense of control or self-reliance, (Bartlett et al., 2017; Correa-Velez et al., 2010; Khawaja & Ramirez, 2019; Samara et al., 2020; Schwartz et al., 2015). However, sociodemographic features like age at arrival, gender or country of origin are found to be relevant as well (Closs et al., 2001; DeJong et al., 2017; Samara et al., 2020). Secondly, regarding the interactions of the children with their close environment, individual skills, adaptative coping strategies and having positive relationships with the caregivers and other close attachment figures, seem to foster well-being and integration (Buchegger-Traxler & Sirsch, 2012; Hamilton, 2013; Pejic et al., 2017). In this sense, schools represent key spaces of structural integration as meeting points where children begin to establish meaningful relationships with the host society and engage with locals, which have the potential to promote their resilience mechanisms and well-being (Horgan & Kennan, 2021). The relationships with peers, teachers, neighbours etc. have been widely examined, showing the role of friendships and social support in building individual and group identities, but also in developing a sense of purpose and belonging (Bartlett et al., 2017; Correa-Velez et al., 2010; Mohamed & Thomas, 2017). In fact, the longitudinal study from Correa-Velez et al. (2010, p. 1406) points at the “sense of belonging, feeling at home and being able to flourish and become part of the new host society” as the best predictors of youths’ well-being. Finally, regarding external sociocultural structures, many studies have presented evidence about the influence of having adequate access to appropriate legal advice and support, education, leisure activities and healthcare services is crucial to all migrant children’s well-being (DeJong et al., 2017; Deveci, 2012; Hamilton, 2013; McCarthy & Marks, 2010). The prevalent cultural representations of childhood and migration and how much the children’s agency and rights are considered, are also reflected in the policies and practices in place, affecting ultimately their integration and well-being outcomes (Gornik, 2020). Additionally, many studies have remarked the need to enforce anti-discrimination policies due to the pervasive effects of prejudice, stigma and discrimination in migrant children’s life trajectories (Binstock & Cerrutti, 2016; Brabant et al., 2016; Correa-Velez et al., 2015; Liebkind & Jasinskaja-Lahti, 2000; McMichael et al., 2011; Schwartz et al., 2015).

The second pillar, adopting an intersectional approach, means acknowledging how the challenges to migrant children’s rights and capabilities interact differentially based on axes of social categorisation and memberships. In this regard, their age, gender, race and ethnicity, or social class, have being pointed as potential sources of vulnerability in terms of well-being and integration results (Kern et al., 2020). Previous research shows the need of further nuance sources of variability, inequality and risks to well-being among different profiles of migrant children and non-migrant-background children (Table 3) (Adserà & Tienda, 2012). In this regard, several studies have remarked the pervasive effect of multiple discriminations that impact the integration paths and well-being of migrant children (Bešić et al., 2018; CREAN, 2014)

Table 3 Summary of migrant minors’ profiles classified from different perspectives

| Focus on reasons for migration (Harttgen & Klasen, 2009). | Focus on children’s origin (OECD/EU, 2018) | Focus on children and family in migration (Adserà & Tienda, 2012) | Focus on status in the host country (UNHCR, 2019) |

| Broadly voluntary vs forced migrant children: Economic migrants Family reunification International protection International students | First-generation migrant children Second-generation migrant children Native | Family migration Left behind Child migration Stayers (non-migrants) | Regular/Irregular migrant minor Unaccompanied/separated minor Refugee/asylum seeker Human trafficking/smuggling |

[i] Source: Authors elaboration based on previous definitions from different sources (Adserà & Tienda, 2012; Harttgen & Klasen, 2009; OECD/EU, 2018; UNHCR, 2019)

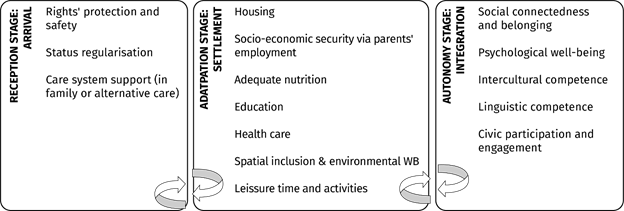

Lastly, the third pillar, about being change-responsive, means to adapt flexibly integration and well-being promotion practices and interventions accordingly to the significant changes in children’s needs. Thus, an emphasis on children’s development and the differential influence that external factors and migration trajectories have on their well-being allows considering age-specific risks and protective factors (Idele et al., 2022). Child protection is aimed at identifying the specific needs of children and designing targeted and flexible support for them (UNHCR, 2013). Though migrant children - as any developing child - present diverse emergent needs, some are more pressing at the initial stages of the integration process. Policy and governance need to acknowledge and address these changing and diverse needs to develop effective courses of action and accomplish positive personal and social outcomes (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2018). Below, a broad approximation of the basic needs of migrant children is presented based on the capabilities to address them at different stages (Figure 1). However, a caveat must be made, noticing that these needs - as any human behaviour - result from the functional interaction between individuals and their context.

Source: Authors elaboration inspired by McDonald et al. (2008) and Ortiz Duque (1996)

Figure 1 Summary of basic pressing needs to meet at different stages of the integration process

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) stresses in Art.6 children’s right to “opportunities to survive, grow and develop, within the context of physical, emotional and social well-being, to each child’s full potential”. Overcoming and meeting well-being challenges and solutions becomes an iterative process across time during integration. In this regard, the intervention models addressing migrant children’s needs oscillate accordingly from mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) interventions in crisis (IASC, 2011; UNHCR, 2013) to more stablished programs at all levels of the health care delivery systems (Lebano et al., 2020).

Discussing a new theoretical framework of integration and CWB

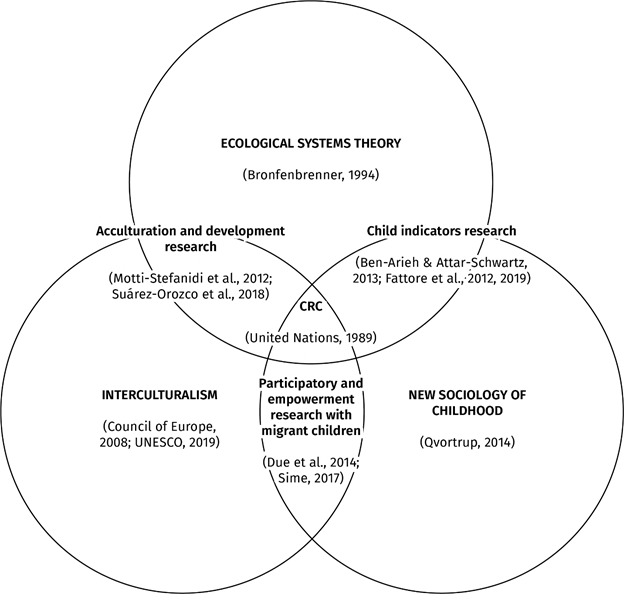

Applying a child-centred approach allows to identify three main theories that comprehensively explain the integration and CWB results of migrant children: ecological systems theory from developmental psychology (Bronfenbrenner, 1994), interculturalism from political science (Council of Europe, 2008) and the New Sociology of Childhood (NSC), that opened a new field of childhood research departing from critical social sciences (Qvortrup, 2014) (see Figure 2). Applied research areas emerge in the spaces of exchange among these theories, opening paths for intervention designing: acculturation and development research (Motti-Stefanidi et al., 2012; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2018), child well-being indicators research (Ben-Arieh & Attar-Schwartz, 2013; Fattore et al., 2012, 2019) and participatory and empowerment research with migrant (Due et al., 2014; Sime, 2017). Both theoretical and applied research of migrant children converge in the international framework established by the CRC (1989).

Figure 2 Conceptual map of theories and applied research about integration and CWB of migrant children.

Theoretical articulation of integration and well-being in migrant children

The NSC postulates that children are holistic individuals holding rights and agency to intentionally influence their social contexts (Qvortrup, 2014). This theoretical stream has deep roots in the interpretative paradigm and conceptualises children as whole subjects that must not be assimilated and misrepresented as mere parts of their family systems. In this manner, the NSC argues that children are “active agents of the social world”, which entails recognising their subjectivity, their agency and consequently, their attached rights (James & James, 2012). This theory flourished with the endorsement of the CRC (1989) and has notably developed - theoretically, methodologically and empirically - how to best articulate in practice children’s right to be heard (art.12), to express freely (art. 13) and to participate (art. 15)

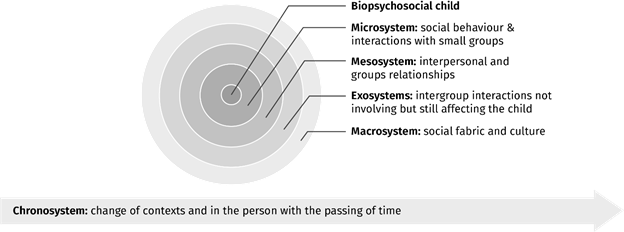

In parallel, according to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory (1994) , the engagement of children with a nested system of interaction settings influences their development. Development is described in terms of relationships between the child and the human, material, or symbolic elements present in their environment. These relationships are contingent and reciprocal interactions that progressively shape children’s growth in ways that are more complex as they learn and become more autonomous. Based on this concept of development, Bronfenbrenner defined five structured contexts of interaction influencing development across the lifespan (Figure 3). As a result, ecological theory operationalises the theoretical definition of development in a process-person-context-time (PPCT) model (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). This way, it provides conceptual grounds to understanding the changing needs of children during development structuring multiple levels of analysis across nested systems of interaction with the child.

Figure 3 Representation of the ecological systems as defined by Bronfenbrenner & Morris (2006)

As explained in previous sections, the intercultural models of integration in political science contest previous conceptions about the incorporation of migrants by recognising the cultural diversity of all societies, the opportunities and richness that this diversity involves and the right to develop multiple and intersecting identities (Ratzmann, 2019). European countries articulate the material resources, normative frameworks and the technical and operational support that derive in the national, regional and local corresponding policies, programs and practices of integration (Zuber, 2017). The intercultural dialogue is pointed in this theory as the essential mechanism that performs intercultural values into actual inclusive practices (Council of Europe, 2008). Besides, the CRC (1989) also reflects this spirit in the principle of non-discrimination across several articles protecting children’s rights irrespectively of their status (art. 2) children’s right to a nationality (art 7) or children’s right to preserve their identity (art 8).

Each of these theories provide clear contributions to theorizing and understanding integration and well-being processes of migrant children from a child-centred approach. The holistic conceptualisation of children and their context is elaborated by the NSC and the ecological theory, which delimit children as specific subjects in research and as multidimensional social agents whose individual results are influenced by their developmental context (Elliott & Davis, 2020; Kościółek, 2021). These two theories also embrace childhood as a dynamic and socially constructed entity. The change across time and contexts is underlined by the vital role that interaction plays in both theories as the mechanism that allows the mutual exchange between person-context. But more importantly, it suggests that the adjustments done within this exchange result in the positive or negative functioning leading to well-being (Amerijckx & Humblet, 2014). In this way, these theories provide a general definition of childhood as holistic, agentic, and socially constructed. Thus, they cover extensively the two pillars of the child-centred approach of holism and change responsiveness, implicitly tackling the intersectional pillar by considering the contextual nature of development and childhoods.

However, specific processes resulting from migration that other children do not experience intersect migrant childhoods. On top of a child-centric understanding of childhood, the role of intercultural dialogue as a specific type of interaction leading to the positive functioning and well-being of migrant children is evident (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2019). Neither integration nor well-being processes of migrant children can be fully addressed without considering how the migrant background and ethnic or cultural diversity intersect their development, fundamental rights, and subjective experience of their childhoods (Gornik & Sedmak, 2021). In this manner, intercultural theory provides proper development of the third pillar of the child-centred approach: an intersectional view of migrant children’s opportunities. The specific challenges to their capabilities and agency derived from their multiple social categorisations, puts them at higher risk of experiencing social vulnerability (Huber et al., 2012). However, the child-centred approach adopted involves acknowledging these risks without underestimating the power of communities and children (even in imbalance conditions), nor their capacity respond to this higher risk by building capacities that lead to safer and more inclusive societies (Fattore et al., 2012).

Theories into practice: applied research in integration and well-being of migrant children

The endorsement of the CRC in (1989) conveys an international framework to apply this child-centred theoretical framework into practice. The four core principles of non-discrimination, the best interests of the child, the right to life, survival and development and the respect of children’s views set the grounds for national and local intervention. Academics have provided three broad research areas, that put in dialogue the theories previously explained and hinge their roots in the principles outline in the CRC: acculturation and development (Motti-Stefanidi et al., 2012; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2018), child well-being indicators research (Ben-Arieh & Attar-Schwartz, 2013; Fattore et al., 2012, 2019) and participatory and empowerment research with (migrant) children (Due et al., 2014; Sime, 2017)

Berry (2005) defined acculturation as “the process of cultural and psychological change that follows intercultural contact”. Integration strategies are defined as a permeable interaction between the person and the host culture in which the individual can maintain his cultural heritage but also decide to transition to the host culture and adopt full membership within this new society (Berry et al., 2006). They seemingly lessen the stress related to the disruption caused by migration and appear to be the form of adaptation that accomplishes better results in terms of less acculturative stress, higher psychological adaptation and higher sociocultural adaptation (Berry, 2005). However, some authors have pointed the need to unravel more clearly the independent effects from acculturation and development, remarking the circularity of arguments and noticing how sticking to these definitions prevents a nuanced understanding of the adaptations that migrant children make (Rudmin, 2009; Sam & Oppedal, 2003).

Current acculturation and development research acknowledges the limitations from previous theoretical postulates and emphasise that migrant children face challenges unmatched by their native peers related to their legal status, culture, exposure to discrimination and development of new social identities (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2018). Additionally, these models maintain a perspective that respects the maintenance of cultural heritage and examines the impact that power asymmetries in the adaptations that migrant (and native) children undertake during integration (Motti-Stefanidi et al., 2012).

Current models of child well-being have been reviewed in the state of the art, however, the methodological and empirical research developed in parallel to this theoretical work requires due mention. Child indicators research has seen major development in the last decades (Ben-Arieh, 2008b). The converging interest of childhood studies and social indicators research led to developing welfare indicators based on child-centred approaches of well-being (Ben-Arieh, 2008a). These measures are designed for describing current well-being state of child populations, monitor policy effectiveness and predict future performance of child populations in terms of well-being (Ben-Arieh & Frønes, 2011). The growth and consolidation of this field of research is denoted by the adoption of national child statistics in countries such as the United Kingdom, Ireland or Canada, and the more ambitious efforts to conduct longitudinal research funded by the European Commission (Pollock et al., 2018)

Finally, participatory and empowerment research assumes acknowledging the importance of power dynamics, the community, and the interpersonal exchanges as critical to develop capacities that produce positive well-being outcomes (Perkins, 2010). The two topics have evolved by hand: participatory methodologies provide practical implementation for leading to promote children’s empowerment and well-being by intervening in the individual (i.e. self-efficacy, critical awareness), interactional (i.e. resource analysis, instrumental support), and behavioural components (i.e. participation in organized activities, involvement in social organizations) (Gornik & Sedmak, 2021). Current research in this area highlights the positive impact of collecting children’s voices by carrying qualitative research, and the ethical and methodological challenges that emerge in this process across research contexts (Due et al., 2014; Sime, 2017)