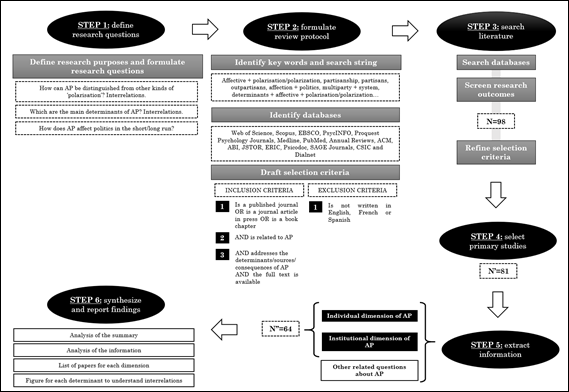

As a first step, our systematic review begins by outlining the main research questions of our work. In this respect, questions such as “How can AP be distinguished from other kinds of polarisation?”, “Which are the determinants/sources of AP?”, and “How does AP affect political decisions?” formed the basis for the selection of the literature for inclusion in our database.

In a second step, a list of descriptors thereupon was considered in order to identify related articles that included any of the chosen terminologies in the title, abstract, or keywords. In this respect, multiple searches were carried out using terms such as “affective polarisation”, “partisanship”, “partisans”, “out-partisans”, “affection and politics”, and “multiparty system”. Due to the aforementioned multidisciplinary approach of this topic, a search for full publications was made principally in areas such as Sociology, Political Science, Psychology, Economics and Communication. As shown in Figure 1, identical searches were conducted in six databases with broad coverage: ISI Web of Science (WOS), Scopus, EBSCO, PsycINFO, Annual Reviews, and JSTOR.

On the basis of the results obtained, the selection criteria were outlined as follows: (1) The literature included in this first round had to come from an academic journal, be published in the press, or be part of a book chapter. (2) The selected cases had to be connected to AP, the determinants, sources, and consequences of AP. Moreover, the full text had to be published in the period 1970-2022, since the study of animosity becomes significant in the nineteen seventies (Brody & Page, 1973; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). (3) The publications had to be written in English, French or Spanish.

In the third step, the procedure was applied, and searches were conducted on title/abstract/keywords to enable a replication of the search procedures in all databases. The search and selection of the work by applying the inclusion-exclusion criteria were carried out by two people independently, in an effort to ensure precision in the process. This procedure provided information of 98 papers (see Step 3 in Figure 3).

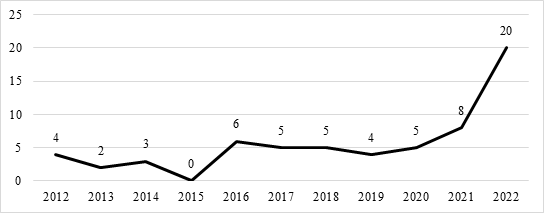

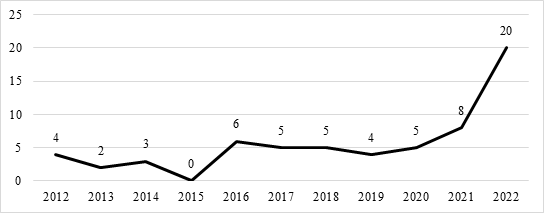

The fourth step consisted of capturing the literature that was relevant to our research interest. The selected criteria were further refined and the number of selected papers in this stage (N’) was reduced to 81. In the fifth step, these 81 papers were then classified into three groups related to the following issues: (1) individual dimension of AP; (2) institutional dimension of AP; and (3) papers that were linked to the topic of this review but did not explicitly analyse issues relating to the individual and institutional dimension of AP (Gough, 2012). Hence, although this third group was not part of the systematic review, these papers contributed towards delving into the issue at hand and, consequently, they have been referenced in Figure 1. Accordingly, the spectrum of the literature review is based on the first two aforementioned groups, which together hold a total number of 64 articles (N’’=64). Compiling and interpreting the existing literature thereon reveals a growing interest in the topic over the last decade (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Publications on AP in Scopus and Wos between 2012 and 2022

Furthermore, Table 1 categorises the selected papers (N’’=64) on key elements such as the dimensions of AP and the methodologies employed for their analyses. Table 1 allows us to codify and synthesise the literature presented in the next two sections, which correspond to the body of this article. Surprisingly, 50% of the selected papers refer to the institutional dimension of AP, as well as in the case of the individual dimension of AP, with 50% of the total of publications. Regarding the methodology used in the selection, the most common is the combination of theory and empirical techniques (mixed methods). This is followed by empirical articles and conceptual papers.

Table 1 Dimension of AP and methodology used in the selected articles (N’’=64)

| Strands of literature on dimensions of AP |

Number of articles |

| Individual dimension of AP |

32 |

| Institutional dimension of AP | 32 |

| Methodology | Number of articles |

| Conceptual | 12 |

| Mixed methods | 33 |

| Empirical | 19 |

Finally, in the sixth step, in line with the review methodology that integrates both strategies (Suri, 2013), we used mainly a synthesis and report approach, in which the key findings of the target papers were analysed and a figure for each determinant was created to aid in the understanding of interrelations in the studies. The literature is interpreted and discussed, but not from conducting any quantitative meta-analysis of numerical results found in the empirical evidence since this would be impossible due to the differences in the issues addressed, in the data sources used, and the methodological approaches employed in the literature (Suri, 2013).

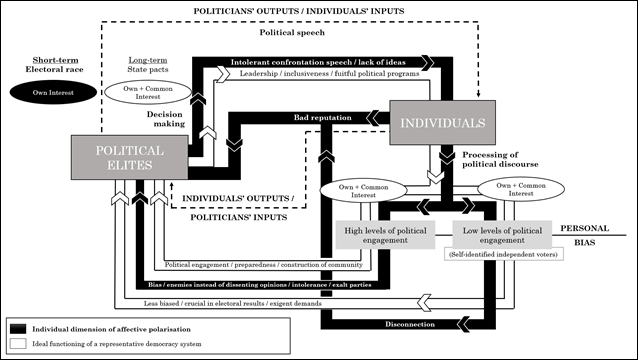

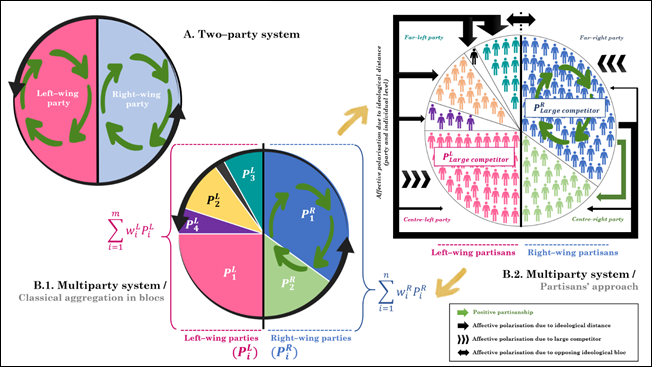

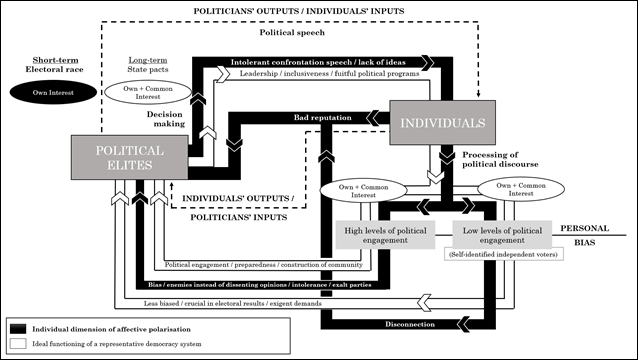

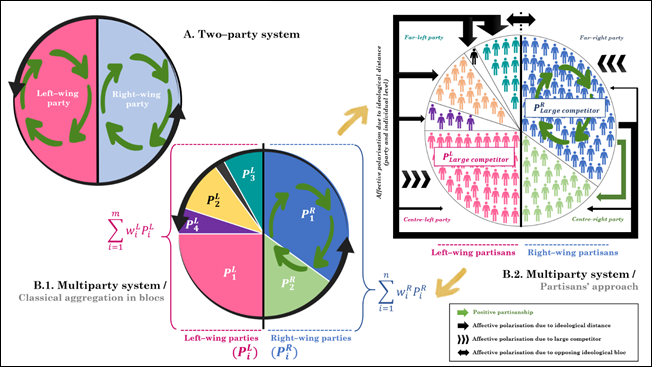

Regarding the process of creation of the figures, Nicol & Pexman (2003) and Rougier et al. (2014) present a clear way to design effective figures for systematic review papers through the interpretation and discussion of the results. In this paper, Figures 3 and 4 aim to synthesise and interpret the individual and institutional dimensions of AP, respectively. Figure 3 describes a circuit to highlight the effects of AP on individual vote decisions. To this end, different tones of grey have been employed to create visual contrast while simultaneously maintaining the simplicity of the figures (Nicol & Pexman, 2003). The black-line circuit represents how AP fuels animosity among individuals in contrast to an idealistic scenario in which voters are not polarised in an affective sense. Figure 4 presents the different ways to conceive AP in multiparty systems, for which pie charts have been utilised in which the hypothetical parties have obtained different shares in the elections. The relationship between them allows us to represent the various channels through which AP is transmitted. In Figure 4, various colours represent the electoral scope and a legend has been created that summarises the different transmission channels of AP. Each transmission channel is represented by a different type of arrow.

Individual dimension of affective polarisation

1

The analysis of the studies focused on the individual dimension of AP outlines two main topics. On one hand, there is the conception that individuals have of the political elites and their interaction with the citizens during electoral campaigns. In this respect, elements such as campaign tone and content constitute crucial factors when studying AP (Sood & Iyengar, 2016). On the other hand, the second main topic relates to the psychological elements of affective evaluations and, consequently, the different voters’ profiles that can be observed (Lelkes & Westwood, 2017). Although certain authors argue that AP alters neither political choices nor mutual respect (Broockman et al., 2022), there is strong empirical evidence of the role that social diversity and individual idiosyncrasy play when analysing the effects of AP on political behaviour (Reiljan, 2020; Ondercin & Lizotte, 2021). Furthermore, as outlined below, this factor entails significant consequences in terms of respectful coexistence and of political fruitfulness (Druckman et al., 2022).

Political elites, hate speech, and negative campaigning

When it comes to explaining the rise of AP in contemporary politics, the negative connotation that voters give to other parties’ elites is considered a major factor (Druckman & Levendusky, 2019). According to Fiorina (2017) , AP is partially explained by how citizens regard the behaviour of certain politicians with displeasure and feel deficiently represented by them. Hetjerington & Rudolph (2015) go further and indicate that the identification of parties with elites undermines governments’ credibility since people do not talk about ideas or political reforms but about leaders. In this respect, Levendusky & Malhotra (2016) and Padró-Solanet & Balcells (2022) indicate that individuals who watch political debates on television usually report feelings such as anger, sadness, and hopelessness when they listen to leaders from other parties they would never vote for. Furthermore, Mason (2013) supports the idea that this rejection of the political elites’ practices towards other parties and their empty words constitute some of the main causes of the rise of uncivil discourse regarding out-partisans.

When analysing the elite’s political discourse, animosity has undoubtedly become a key point in political campaigns and ideas have been put on the back burner (Lelkes & Westwood, 2017). According to Fowler et al. (2016) and Rodríguez et al. (2022) , we now live in ‘the era of the negative campaigning’, whereby political opponents are portrayed as the opposite of what the country, region, city or town needs, no matter the content of the speech. In this respect, Berry & Sobieraj (2014) depict a society that treats out-partisans as if they were Nazis, and explain how animosity towards political dissidence plays a central role in contemporary political campaigns.

According to Iyengar et al. (2012) , territories that are less exposed to political campaigning are less polarised in an affective sense. Furthermore, citizens seem to be more polarised when political campaigns finish in comparison to when they start (Sood & Iyengar, 2016). However, this statement is not shared by Ridout et al. (2018) nor by Hernández et al. (2021) , who study the correlation between animosity in the United States’ campaign for the presidential elections in 2014 and people’s exposure to political advertising. They found that there is a negative correlation between these two variables. Moreover, Fowler et al. (2016) , Benkler et al. (2018) , and Madariaga & Riera (2022) highlight the importance of campaign tone and campaign content when it comes to determining the relationship between AP and people’s exposure to negative campaigning.

Affective evaluations and the voters’ profile

According to Brody & Page (1973) , Tajfel & Turner (1979), and Miller et al. (1986) , affective evaluations are much more subjective than are voting decisions. While in the second case, individuals support one politician over another, in affective evaluations people tend to choose one candidate in rejection of the other. In order words, people do not decide their vote after reading the electoral programs, but as an impulsive response to the options they detest, no matter whether what they have chosen actually represents their particular interests. This irrationality in vote decisions has been widely studied from the perspective of the Theory of Public Choice as a failure of this branch of Economics (Pressman, 2004). Although there are empirical studies that prove that AP increases political turnout, not every voter responds in the same way to a rise in AP. Hence, the study of the voters’ profile seems to be relevant when analysing the effects of AP in a holistic way.

In this respect, Rogowski & Sutherland (2016) and Serani (2022) state that high levels of political engagement create positive externalities in the community. This fact is also linked to the rise of animosity among individuals. In relation to this issue, Sniderman & Stiglitz (2012) consider that extreme affective engagement to a particular political option can blind people’s loyalty to individual leaders and parties, thereby making them ideologically biased and eroding social debate with the rest of the political options (Kingzette et al., 2021).

The existing literature also identifies a self-identified independent group of voters (Klar & Krupnikov, 2016). This group is not ideologically neutral, since it votes according to its own preferences. However, voters who self-identify as ‘independents’ are more likely to change their vote in comparison to voters showing high levels of political engagement (Sniderman & Stiglitz, 2012). Although a number of authors believe that the self-identified independent group of voters shows higher levels of rationality in comparison to those who experience intense engagement towards a specific party (Klar, 2013), the central finding relating to this group is that they tend to disconnect from politics when they perceive a highly polarised environment (Sniderman & Stiglitz, 2012). This disconnection leads to new approaches and perspectives when analysing the channels of AP from an individual perspective (Rodon, 2022). Finally, the trend of political inaction of this group of voters could explain why many centre-left and centre-right parties have lost strength in countries that are highly polarised in an affective sense (Reiljan, 2020).

A holistic interpretation of affective polarisation from the individual dimension

Following Nicol & Pexman (2003) and Rougier et al. (2014) , Figure 3 presents a diagram that synthesises and interprets the existing academic literature on the individual dimension of AP. By compiling the aforementioned ideas, Figure 3 shows how AP is incrementally fuelled in a vicious cycle by the interaction between political elites and individuals. Firstly, political elites use AP in their speeches for electoral purposes (black line in Figure 3). Although they may achieve this goal, citizens reject politicians’ behaviour since these citizens value other non-existent elements in such speeches, such as fruitful policy programs and the search for peaceful coexistence (white line in Figure 3). The lack of mention of these elements increases politicians’ bad reputations (Hetjerington & Rudolph, 2015).

Secondly, AP has a second-round effect depending on the type of individual (Sniderman & Stiglitz, 2012; Klar & Krupnikov, 2016). On one hand, in the case of self-identified independent voters, AP disengages and disconnects them from political elites and public affairs. This contributes towards increasing their disappointment in regard to political elites’ behaviour. On the other hand, for individuals who experience high levels of political engagement, the impact of AP is translated into biased arguments, hate towards out-partisans and the exaltation of their leader, who is hardly ever questioned (Sniderman & Stiglitz, 2012). This scenario inevitably generates an opportunity cost (i.e., an efficient representative democracy system, in which politicians’ decisions are nurtured by people’s feedback), which is ideally depicted by the white line circuit in Figure 3.

As mentioned in Brody & Page (1973) and Miller et al. (1986) , each political decision entails a personal bias for individuals, and hence both the black line and the white line are processed by each person for which their background, personality, culture, etc. Furthermore, while the upper part of the circuit can be interpreted as the input that individuals receive from politicians (using political discourse and campaigning as the main tools), the lower part of the figure depicts individuals’ reactions which are considered inputs that political elites should bear in mind for their speeches

2

and actions. Since heterogeneous voters are considered here, the idiosyncrasy of each individual (highly engaged with politics vs. self-identified independent voter), their personal bias, and the individual decisions they make regarding how they process political speeches will affect their levels of AP (Sniderman & Stiglitz, 2012; Klar, 2013; Klar & Krupnikov, 2016). At the same time, politicians can choose which part of the feedback received is included in their political speech and policies, thereby contributing more or less towards increasing AP.

Finally, both lines represent a different way of conceiving politics and public leadership: on one hand, politicians can pursue a myopic strategy (Brown & Lewis, 1981), focusing on polarising society in an affective sense (black line) as a way to achieve their own short-term objectives (i.e., maximise their electoral credit). This decision leads to an incremental vicious circle of AP in which, although politicians can gain votes from their political opponents by confronting individuals before the election day, they find it difficult to achieve broad parliamentary consensus after the elections since they have depicted out-partisans as enemies. This factor leads to unproductive legislatures in which the introduction of long-term policies that need a broad parliamentary consensus (state pacts) are postponed or cancelled due to the use of animosity as a political tool.

However, politicians can also choose to reduce AP (as represented by the white line in Figure 3), by adapting their speeches to address a wider scope of citizens. They can also put their efforts into the identification of the main contemporary socio-economic challenges and promote a consensus-building culture capable of designing and implementing the appropriate policies in order to tackle the aforementioned stakes (Dias & Lelkes, 2022; Santoro & Broockman, 2022). In the individuals’ case, only the decisions represented by the white line allow them to achieve their personal and collective interests, since it has been proved that, with high levels of AP, people cannot pursue their personal motivations, even when they believe that they are being loyal to their principles (Pressman, 2004). In this respect, Clark (2023) indicates that civic education experiences, such as community service and pedagogy classrooms, play a crucial role when explaining citizens’ attitudes towards the aforementioned inputs.

Figure 3 Individual dimension of affective polarisation

Institutional dimension of affective polarisation

3

The institutional dimension of AP is related to the dynamics of political parties. This section needs to be understood as a complementary approach to the individual dimension of AP, in that it completes the picture of how AP is boosted and transmitted. As shown below, political parties are crucial actors in the construction process of individual identity. In fact, the confrontation of identities and sensibilities by political parties seems to explain the rise of animosity, even more than do ideological differences on socio-economic issues (Dinas, 2013). It is shown below how the atomisation of the political spectrum leads to a situation in which conflict and the lack of dialogue among political groups prevail over political consensus, which leads to a situation of institutional deadlock.

Identities and parties: the complexity of a multiparty system

When studying how people choose their political candidates, parties have always been a crucial actor to consider, since they provide a common ideological umbrella under which partisans hold a strong in-group affection (Greene, 1999; Huddy, 2001; Johnston, 2006). There is a wide range of academic literature on the role of parties and the consolidation of individual social identity (Bankert et al., 2016; Kalin & Sambanis, 2018). It is commonly believed that partisan ties are normally defined during early adulthood (Huddy, 2001). If these ties remain constant over life, they sometimes lead to stable electoral decisions and stable political opponents (Niemi & Jennings, 1991; Dinas, 2013). While the study of political outgroups is not new (Greene, 1999; Dalton et al., 2000; Brewer, 2001), current studies highlight the importance of revisiting the trends of in-group and out-group polarisation in this new multiparty scenario (Iyengar et al., 2012; Iyengar et al., 2019; Wagner, 2021; Harteveld, 2021; Knudsen, 2021; Torcal & Carty, 2022).

According to Renström et al. (2021) , AP demonstrates clear links to social identity divisions rather than to disagreements on the policies defended by the different parties. Confrontation based on identities is commonly fuelled by parties in order to gain votes as they need to self-differentiate from the rest of the political options that compete for the same political space (Stephan & Stephan, 2017). In a context of political atomisation therefore, AP is linked to the aforementioned identity conflict, which can be understood in a broader differentiation strategy with a view to maximising votes by opposing sensibilities (Miller, 2020). All in all, the rise of party competition due to multiparty systems tends to promote social confrontation instead of confronting ideas as a way to obtain electoral credit. This differentiation strategy consists of indicating ‘the bad ones’ (out-partisans) in contrast to ‘the good ones’ (partisans) (Kekkonen et al., 2022). This idea connects to the individual dimension of AP, in which political speech is regarded as a tool to fuel animosity among individuals.

The connection between animosity and the irruption of multiparty systems has been extensively documented in the United States, but it can also be extrapolated to other socio-economic situations. In fact, recent research has proven the existence of a relevant connection between the irruption of multiparty systems and interparty hostility in a wide variety of contexts (Westwood et al., 2018; Ward & Tavits, 2019; Helbling & Jungkunz, 2020; Gidron et al., 2020; Miller, 2020; Reiljan, 2020; Boxell et al., 2022; Kawecki, 2022; Torcal & Comellas, 2022).

One of the main contributors to the task of understanding AP from a multiparty approach is Wagner (2021) , who indicates that, while measuring AP in a two-party system is relatively manageable, the act of assuming the challenge of measuring AP in a multiparty system is much complex due to the number of variables, actors, relationships, and effects that need to be considered. Consequently, there is a clear need for the provision of more theoretical and empirical work on the rise of AP in multiparty systems (Medeiros & Noël, 2014; Abramowitz & Webster, 2016; Mayer, 2017; Kekkonen & Ylä-Anttila, 2021; Kekkonen et al., 2022). In this respect, one aspect that notably changes when moving from a two-party system to a multiparty system is that of partisan ties and the relationship with political outgroups. While in a two-party system it is relatively easy to identify negative and positive partisanship, affection and animosity vary when there are more than just two political options (Medeiros & Noël, 2014; Abramowitz & Webster, 2016). In fact, questions such as how many parties are disliked or how much rejection they produce are pertinent and necessary in a multiparty system (Klar et al., 2018).

In order to simplify the complexity that entails an AP analysis in a multiparty scenario, Wagner (2021) identifies two types of theoretical approaches. The first approach consists of aggregating the various political alternatives into the two classical blocs. On one hand, all right-wing parties would be grouped into one bloc. On the other hand, left-wing parties would be bundled into a second bloc. Thus, AP could be addressed from a classical point of view. Nevertheless, the act of grouping parties into ideological blocs oversimplifies the situation, and apparently reduces the explanatory potential of AP. For example, it makes it impossible to identify all degrees of AP that exist for each group of partisans (Garry, 2007). Furthermore, certain aspects, such as the size of the party, really do matter when determining the degree of AP among partisans in a multiparty system. Lastly, if individuals hold negative feelings towards a large competitor, then society becomes more polarised in an affective sense than when these individuals do not like a minor option: another fact that cannot be studied from this approach (Wagner, 2021).

Considering all the aforementioned ideas, AP in multiparty systems from a voter’s perspective could apparently be the most accurate option -this being the second approach proposed by Wagner (2021) -. In this respect, Maggiotto & Piereson (1977) show how partisans tend to hold negative views of other parties but also of the voters of other parties. When Curini & Hino (2012) depict a society in which larger political parties are more dissident in an affective sense than the smaller parties, then it is implicitly assumed that big coalitions are barely plausible. This latter consideration could encourage a return to the aggregated conception of a multiparty system, in which there are two immobile political blocs that are the result of the aggregation of different parties with a shared ideological basis (Wagner, 2021).

A holistic interpretation of affective polarisation from the institutional dimension

Given the aforementioned explanation, Figure 4 resumes and interprets the existing literature grouped in the institutional dimension of AP (Nicol & Pexman, 2003; Rougier et al., 2014). It highlights the advantages and weaknesses of the aggregated and the individual approaches when analysing AP in a multiparty scenario. In this figure, three pie charts (A, B.1, and B.2) are presented. The three depict the political spectrum of any territory at any level (national, regional, and local). Pie chart A describes the circuit of AP in a two-party system

4

. As already stated, positive partisanship is deduced from the emotional relationships and the sense of community created among partisans (green arrows). Furthermore, the outgroup affection of each party (partisans’ disaffection towards other political options) is depicted by the black arrows. However, today’s political situation is characterised by the emergence of multiple political groups (Wagner, 2021), and this obliges us to redefine the sources and effects of AP.

In this respect, pie chart B.1 represents how a multiparty scenario can be conceived as a two-party system (Wagner, 2021). The methodology consists of interpreting the right-wing and the left-wing ideological spectrum as the only two parties. This situation is depicted by the expressions

i=1

n

w

i

R

P

i

R

and

𝑖=1

𝑚

𝑤

𝑖

𝐿

𝑃

𝑖

𝐿

, in which

𝑃

𝑖

𝑅

represents one particular party from the right-wing bloc,

𝑃

𝑖

𝐿

depicts one particular party from the left-wing bloc,

𝑤

𝑖

𝑅

denotes the weight of the right-wing party 𝑖 in the right-wing bloc, and

𝑤

𝑖

𝐿

denotes the weight of the left-wing party 𝑖 in the right-wing bloc. Moreover, 𝑛 and 𝑚 correspond to the number of parties that coexist in the right-wing bloc and the left-wing bloc, respectively. However, this approach shows several limitations as explained in Maggiotto & Piereson (1977) , Garry (2007) , Curini & Hino (2012) , Medeiros & Noël (2014) , Abramowitz & Webster (2016) , Mayer (2017) , Klar et al. (2018) , and Wagner (2021). This provides the justification of the partisans’ approach, whose main conclusions are outlined in pie chart B.2.

A multiparty system conceived from the partisans’ approach focuses more on individuals’ dynamics instead of on the parties themselves (Wagner, 2021). This approach allows us to identify various circuits of AP as well as different intensities of this concept. As can be observed, starting from far-right partisans, there is, on the one hand, an AP channel (black circuit), which corresponds to the ideological distance existing between the far-right party and all the other political options. The arrows become broader as ideologies become more distant from the far-right group of voters (i.e., AP increases as political options are less similar), (Garry, 2007). Furthermore, not only is this source of AP directed towards parties, but also towards out-partisans (Maggiotto & Piereson, 1977).

On the other hand, there is another source of AP which is related to being a ‘large competitor’ (Wagner, 2021). In the hypothetical scenario depicted in Figure 4, only the far-right party and the centre-left party would be defined as large competitors, since they embody the greatest number of partisans of each semicircle (right side and left side, respectively). These parties are represented by

𝑃

𝐿𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑒 𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑝𝑒𝑡𝑖𝑡𝑜𝑟

𝑅

and

𝑃

𝐿𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑒 𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑝𝑒𝑡𝑖𝑡𝑜𝑟

𝐿

. There would therefore be an extra source of AP in these two cases. Finally, there is an extra source of AP that comes from the disaffection towards the whole opposite ideological scope (represented by the double-headed arrow over pie chart B.2). One consequence of the atomisation of the political spectrum is often the emergence of minority governments. In this context, pacts are usually signed with the closest competitor in an affective sense, and hence political decisions are interpreted as a result of the interaction of the bloc (Kekkonen et al., 2022).

In terms of positive partisanship, intra-positive affection is found (such as in pie charts A and B.1), but there is also a positive recognition of out-partisans who are close to each ideology (this fact is represented by the green arrow that connects the far-right party to the centre-right party). Finally, the yellow arrows that create a loop between chart B.1 and chart B.2 represent the idea that, although the partisans’ approach distinguishes different channels through AP is fuelled, parties operate in reality as if they constituted two blocs, making consensus almost impossible between parties of the right-wing and the left-wing blocs. All in all, pie charts B.1 and B.2 represent complementary approaches as both depict relevant aspects of the current political unfruitfulness. Finally, the aforementioned party dynamics render state pacts difficult objectives to achieve due to the fact that they need an ample parliamentary consensus that often exceeds the size of the left-wing or the right-wing bloc, even in a context of an absolute majority (Curini & Hino, 2012). Consequently, politics becomes a puzzle of supports focused on short-term interests and state pacts are commonly delayed.

Figure 4 Institutional dimension of affective polarisation

![]()

![]()

![]()