Introduction. Crises and rural vulnerabilities

The growth in social discontent has brought territorial vulnerability to European

political agendas owing to the disparities in accessing the opportunities, services and resources that

shape welfare. The challenge of socio-territorial cohesion gained fame in the light of the 2008 financial

capitalism crisis, when many of the regions that are far from major urban centres throughout the continent

deepened their youth decapitalisation as well as their economic and demographic decline (Danson and de Souza, 2012; Fischer-Tahir and Naumann, 2013; Kühn, 2015). The perception of abandonment and subordination to policies oriented by

external interests became widespread in those places that seemed to have ceased to matter (Rodríguez-Pose, 2017; Guilluy, 2019) and this often ended up

projected in the support for populist political programmes (Mamonova and Franquesa,

2020). However, as Walsh (2012) discovered in the United States, this rural

awareness responded to an experience of inequality that went far deeper than its simplification as a

“resentment vote”.

The issue facing these regions, small cities and rural districts has been theorised by

Kühn (2015) as a phenomenon of “peripheralisation”. He uses the term to emphasise

their condition as a process, as opposed to the statism suggested by the category of periphery. The

proposal is interested in the dynamics of this configuration as a result of economic, political and

communicative relationships that therefore can also be modified by social stakeholders.

Herein we explore this process on a local scale and as the product of the distancing

and erosion of rural welfare. Such an effect has persisted since the neoliberal policies at the end of the

last century (Cloke, 1995; Shucksmith and Chapman, 1998; Farrington and Farrington, 2005; Woods, 2005) and has now extended

throughout the recent crises, where our analysis is contextualised. In fact, for authors such as Milbourne (2016) , the austerity policies defined the model of “how social and other

public services would be delivered in rural areas in the upcoming decades” (p. 455).

Adjustment criteria had a notable impact on the infrastructure that makes up rural

welfare. This is particularly so in southern European economies, due to cutbacks in public employment,

social policies and services, as well as the reorganisation of their territorial administrations (Guillen and Pavolini, 2015; Döner et al., 2020). Against this

background, the subsequent collapse due to the pandemic has required urgent social coverage to be deployed

without reducing disparities. This exceptionality has also reinforced other logics, such as acceleration

in the digitalisation and dematerialisation in how services are provided, which showed a premature

abandonment of the rural world (Alloza et al., 2021). Financial exclusion, for instance,

affects over half of Spain’s municipalities (Posada, 2021).

The main challenges of rural vulnerability are intrinsically intertwined with welfare

and accessibility. The European Commission document entitled A long term Vision for EU Rural Areas Report,

based on specific public consultation, highlights accessibility as the largest problem, as mentioned by

44% of those interviewed (European Commission, 2021, p. 3). At least one in five

interviewees perceived access to health, care, training and services as being the main drawback of those

territories. In other words, the difficulties involved in being able to enjoy, as the Commission specified

in another document, “all those services and activities which represent common facilities for people

living in urban centres (such as schools, hospitals, sports and cultural facilities)” (European Commission, 2008, p. 5).

Furthermore, the distancing from employment, services and opportunities requires a

growing need to hybridise rural life with urban centres and is accompanied by continual intensification in

car use (Osti, 2010; Oliva, 2010; Milbourne and

Kitchen, 2014). Commutes and the distances travelled are multiplying at the same time as car

dependence emerges as a particularly interesting research line for studying inequality (Mattioli, 2017; Brovarone et al., 2021; Camarero and

Oliva, 2021).

However, in most rural policies, this role of mobility in the access to and the

provision of welfare remains somewhat invisible. Even for sociology, as recalled by Urry

(2007) , mobility has traditionally been a sort of “black box”. It is a shadow zone that the

paradigm of mobilities seeks to illuminate in order to account for the coercion that they exert on the

material production of social life and the territory. This perspective, “forces us to pay attention to the

economic, social and cultural organisation of distance, and not merely the physical aspects of movement”

(Urry, 2007, p. 54).

The aim of the present work is to analyse and understand the socio-territorial

relationships that emerged from this combination of crises and rural changes that have accumulated in the

last decades. We shall therefore delve into their impact in specific local settings that are facing the

risk of becoming peripheral. The social experience of the groups who live with this distancing of welfare

provides an essential source of information to understand how rural vulnerability is configured. Our

approach additionally seeks to account for the rationalities with which the socio-territorial

marginalisation and the awareness of inequality operate, using fieldwork carried out in two rural

representative remote (Pyrenees) and peri-urban (Middle Zone) areas in Navarre. Based on rural studies,

the research addresses this reality which does not fit well into the modern-day concepts of the average

citizen, and who ends up being continuously relegated to a peripheral fragility.

In the following section we shall discuss the analysis lines that enable us to examine

the rural gap and socio-territorial vulnerability. Subsequently, we will consider the erosion in welfare

in rural areas and its relationships with mobility. After that, the methodological strategy adopted and

the observation contexts chosen as case studies are presented. The following sections detail the battle

against the erosion of local services and the mediation of private mobility in the access to and provision

of welfare. Finally, the conclusions reflect on the results obtained and suggest the incorporation of a

broader view of the risk that these imbalances in rural policies entail.

Socio-territorial peripheries of the rural gap

The Welfare State is something that we normally take for granted; this prevents us

from appreciating the broad deployment that it acquires in our daily lives (Milbourne,

2010). It is only when it seems uncertain or in doubt, as occurred in the last crises, do we realise

its true importance. But going beyond the debate on its nature (Marshall, 1965, Rawls, 1971) and the peculiarities it acquires in different countries, its priorities

were considerably redefined by neoliberalism from the end of the past century (Peck,

1998, 2001; Esping-Anderson, 1990; Pieterson,

1998) with formulae that would later inspire the austerity policies implemented in the aftermath of

the 2008 crisis (Martinelli et al., 2017).

As Milbourne (2016) warned, many countries did not regulate their

financial sector, but did cut back on social policies, with speeches blaming the financial elites being

replaced by other comments repeating how the Welfare State was unsustainable. Programmes thus became

“moral and political projects that reformulated rights and responsibilities” (Milbourne,

2016, p. 7). This pressure to make the costs of work, social spending and reorganising the

territorial administration cheaper (Guillén and Pavolini, 2015) had far-reaching

repercussions on local powers, which were the front line in service provision (Matthies et

al., 2011; Clelland, 2021).

However, its transcendence in the rural setting cannot be understand if we ignore the

previous weaknesses that these societies already felt in some countries (European

Commission, 2008) and reflected their elderly demographic structures, the proportion of unskilled

labourers, and poor quality employment (European Commission, 2011b; European Observation Network for Territorial Development and Cohesion [ESPON], 2017; Congress of Local and Regional Authorities, 2017; European Commission,

2021). This fragility was even more eloquent in southern Europe, with Greece and Spain heading up

the indices of rural population at risk of poverty, in the old 15-country European Union (European Commission, 2011a).

The peripheral condition of numerous territories throughout Europe was at that time

related with circles of cumulative causation derived from disinvestments, selective migrations and labour

precariousness (Danson and de Souza, 2012; Fisher-Tahir and Naumann,

2013). In rural areas, these processes were associated with the neoliberal model of deagrarisation

and the support of populist political programmes (Mamonova and Franquesa, 2020), the

issue of the “interior peripheries” and accessibility planning (Brovarone, 2022), as

well as unequal regional structures of opportunities (Bernad et al., 2023).

At this point we would like to highlight the discussion developed by Kühn (2015) on the categories of periphery and peripherisation, to suggest the open

approach of the latter, as “the dynamic processes through which peripheries really emerge to become the

focus of attention” (Kühn, 2015, pp. 3-4). Such an approach enables us to explore the

configuration of rural peripheries as a process, taking the mechanisms that concur in their formation at a

local scale and as an effect of the distancing from welfare. That is to say, as a result of the erosion of

opportunities, resources and services that precedes and accompanies depopulation. This is something that

requires, on the one hand, the recognition of its political condition as a social process and, on the

other hand, the visualisation of the underlying dynamics in these forms of exclusion and disconnection.

In the case of Spain, part of the cost of austerity was passed on to the

municipalities through the 2013 Law for Rationalisation and Sustainability in Local Administration, which

eliminated services that were considered “unsuitable” or “duplicated” according to the rationality of

economic adjustment. It also prevented the creation of new municipal entities and the remuneration of

mayors in municipalities with fewer than 1,000 inhabitants. In parallel, regional administrations further

extended the cutbacks to emergency medical services, health centres and rural schools. They also reduced

the transfers of municipal funding applied with a finalist sense to a broad variety of social services

(sheltered housing for the elderly, day-care centres, social work, nursery schools, adapted taxis,

oncology and school buses, etc.). Private services joined in this withdrawal and dismantling of rural

welfare infrastructures. For instance, the closure of bank branches increased the proportion of rural

municipalities without banking services from 48% in 2008 to 59% in 2020 (Banco de España,

2021, p. 285), with others suffering the distancing in terms of reductions in their opening days and

hours, the replacement of branches for ATMs or itinerant bank-buses.

Rural populations were not passive recipients of the cutbacks and this gave rise to

continual mobilisations and resistance (Farmer et al., 2011; Sanz and

Oliva, 2020). As Farmer et al. (2011) explained, when the rural population

protests because of the loss of a nurse they are doing so because it also means the dissolution of a whole

set of resources implicit in their access to health, human capital and local vitality. Examples of the

dismantling and distancing of rural welfare include the disappearance of numerous municipal jobs

(educators, technicians, cultural agents, social workers, firefighting crews), as well as losing potential

local residents.

These underlying disparities in the rural gap and which are present as deficits in

access to education, health or employment (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development [OECD], 2006; Committee of the Regions, 2014) can be analysed as a

minoritised version of citizenship (Camarero and Oliva, 2019). On the whole they refer,

as explained by Shucksmith et al. (1994) , to “the incapacity of individuals or

households to take part in lifestyles open to the majority” (p. 345). The authors link that condition to

exclusion because it does not come from the individual, as the neoliberal rethinking of welfare would

imply, but from the power relation structured in the territory. Therefore, it is necessary to examine in

greater depth what this distancing from welfare means and how it characterises the rural world’s current

fragility.

Distancing from welfare and rural mobility

The different socio-technical configurations of the territory and infrastructures have

an important role in the production of socio-territorial peripheries. The analysis by Graham and Marvin (2002) on this research line demonstrated how the devaluation of the

paradigm of modern infrastructures, where the idea that resonated was of services spread out like a

capillary network throughout all the territory and society, has given way to another fragmented and

privatised model (fast trains, toll access, premium connections), which disconnects groups and redundant

spaces. Their perspective offers a special optic for understanding rural vulnerability and the exclusion

that ensues from the incapacity of certain groups and territories to equip themselves with the

accessibilities predominating in that moment (Cass et al., 2005).

Putting the focus on the material production of the territory facilitates

understanding the risk of marginalisation in rural villages under market efficiency criteria. As Salemink et al. (2017) observed about the policies implemented to develop rural

connectivity to internet, “governments have only been able to react to market and society developments,

rather than anticipate them (…) and to define the new technologies as public services” (p. 367). Bank of

Spain studies have revealed a landscape of disparities that is unparalleled in Europe (Posada, 2021; Alloza et al., 2021), and that only 50% of rural

households had broadband access, compared to the European average of 87% (European

Commission, 2021, p. 5).

The aspect that best highlights rural disparity and the costs of welfare deprivation

is the need to travel to access basic services. For instance, people in rural areas of Spain have to

travel a mean distance of 12.4 kilometres to do so, compared to 7.6 kms in French and 4.7 kms in Italian

rural areas (Alloza et al., 2021, p. 8).

Cresswell (2014) stressed that in the supposedly uniform world of spatial interaction,

we come across the “friction of distance” (p. 109) and the policies that selectively regulate its effects.

These unequal relationships with distance have led it to be considered a determining factor in rural

settings (Young, 2006) , where the global connections of production chains often

coexist with the local disconnection of secondary places and groups.

But these effects of welfare distancing and the friction caused by distance need to be

made visible. For example, they emerge clearly in studies that uncover phenomena such as “health poverty”

which is characteristic of rural areas, owing to the limited public transport, scant health services and

personnel, as well as the digital divide (Manthorpe and Livsey, 2009; Douthit et al., 2015). They are also illustrated by the effect known as “distance decay”

whereby seeking help decreases when the services are perceived as being far away (Manthorpe

and Livsey, 2009, p. 17). As a consequence, in rural areas, “the problems of transport, access to

services and social isolation are considered more important in the experience of marginality than in urban

areas” (Clelland, 2021, p. 162).

Rural studies have identified this poverty as not fitting in with policies designed

from urban generalist criteria (Cloke, 1995; Farrington and Farrington,

2005) and that it is more vulnerable to the processes that we are analysing. Unlike in cities,

poverty in rural areas, as Milbourne (2016) summarised, “remains largely hidden in the

physical, political and socio-cultural fabric of rural space” (p. 452). In these territories it is

dispersed, isolated and its sociological profiles are less associated with unemployment but rather with

job insecurity, elderly persons living alone, and poverty of accessibility.

Rural poverty is therefore strategically linked to mobility, as social capital (Kaufmann et al., 2004) which enables hybridisation of residing locally with the distant

opportunities and services. But ultimately this capital ends up becoming eroded such as when elderly

people who give up driving lose their autonomy, and they go from being an asset in family mobility to

being people requiring care and travel (Ahern and Hine, 2015; Sanz and

Oliva, 2021).

In the same sense, the relevance acquired by mobility for young rural adults to enter

the job market has been highlighted by Binder and Matern (2020) as “an important

cornerstone of the daseinsvorsorge (ensuring existence)” for these groups in Germany. Black

et al. (2019) also described the fragility of life projects with the deterioration of public rural

transport caused by cutbacks in the United Kingdom, which ultimately affect family resources and thus

entail a “secondary impact of austerity” (p. 273) derived from social class.

The rural population’s car dependence (Mattioli, 2017; Brovarone et al., 2021) paradigmatically condenses their peripheral separation from

welfare. As a predominantly private resource, it also adds exclusion and disadvantage defined as “mobility

poverty”, which is an issue of particular interest in European Union institutions, where more research on

the interrelations between poverty, inequality and rural mobility is sought in order to design truly

effective policies. (Kiss, 2022).

Efficient socio-territorial cohesion policies require these processes to be studied in

specific risk scenarios, by fieldwork to profile the vulnerable groups and how the dynamics are

articulated which shape the periphery as a marginalisation process. As Bertaux (2005)

proposed in his recommendations for ethnomethodological analysis, when one such pattern appears

recurringly in research, we have a need to name it and thus “it is distinguished from the background where

too many processes intertwine, it is born and appears in sociological discourse, it is transformed into a

subject of thought” (Bertaux, 2005, p. 111).

Methodological approach

The information analysed has been produced in two projects within the Spanish State

R&D Plan which combines the study of rural policies with fieldwork in two districts that make up our

case studies in Navarre (Figure 1). On the one hand, the MOVIDIVERSOS project

(CSO2012-37540) explored the role of mobility in the resilience of rural areas under the austerity

policies. On the other hand, the RURAL ACCESS project (PID2019-111201RB-I00) examined the rural gap in

welfare access in the pandemic years.

The methodological approach adopted covers several moments. Firstly, types of

scenarios were identified (rural remote and rural peri-urban) as contexts for observing socio-territorial

vulnerability. Their characteristics were contrasted in special sessions at international congresses and

seminars with social institutional agents during the first of the two projects, in which fieldwork was

carried out in the Pyrenees as well as in the Gran Vega of the metropolitan area of Seville and in the

parish of Sao Jacinto in the conurbation of Aveiro in Portugal. These analyses assisted in the choice of

scenario for the “rural peri-urban district” in Navarre, specifically in the district of the Middle Zone,

southeast of the regional capital city. The observation contexts were therefore chosen intentionally

because of their significance for analysing socio-territorial vulnerability. Some of the indicators

elaborated for this research that summarise their appropriateness for this objective are presented in Table 2 in the following section.

Secondly, the fieldwork was carried out from face-to-face semi-structured interviews

and seeking to complete qualitative samples iteratively until strategic saturation was achieved; in each

case this was after around 20 interviews. Table 1 provides the general characteristics

of the fieldwork and the final Annex details the people who were interviewed. Scripts were followed by

means of open-ended questions and a listening attitude which enabled interviews that lasted from 50 to 90

minutes, conducted in the chosen people’s homes and workplaces, spaces provided by local councils, and by

the Public University of Navarre.

Examination of the corpus of interviews was inspired in sociological discourse

analysis (Ibañez, 1985; Alonso, 1998) typically used in rural studies

(González et al., 1985; Gray et al., 2006; Walsh,

2012) and in the ethnomethodological criteria suggested by Bertaux (2005) , in

which the fieldwork builds up an interpretive model of the phenomena observed in a joint elaboration of

hypotheses and concepts.

The interviews with experts and key informers (mayors, grassroots social service

technicians, teachers, development agents, health service staff, family workers, etc.) gather together

specialised views and verify observations from the analysis and from the field work. They also identify

vulnerable groups, the effects of the crises impacts, and the professional performance in welfare services

(dysfunctions, limitation, improvisations needed on a day-to-day basis). Additionally, the sociological

profiles chosen according to family characteristics, generational and gender conditions (households with

dependents, elderly persons, transfrontier workers, migrants), reveal in their narratives the experience

of welfare distancing, the social perceptions of marginalisation and the right to welfare.

The strategic sampling deliberately considered habitat criteria to ensure enough

interviews were undertaken in small municipalities (fewer than 200 inhabitants in the Pyrenees and fewer

than 500 inhabitants in the Middle Zone). Contact was made through the social media of the research team

in the study areas; snowball methodology; and letters presenting the project. Interviews were conducted in

a total of 22 municipalities: Abaurrea Alta, Urzainki, Aria, Vidangoz, Burgui, Esparza, Jaurrieta, Izal,

Ochagavía, Roncal, Isaba and Espinal for the Pyrenees case study; and Artariain, Amatriain, Caparroso,

Carcastillo, Leoz, Olite, Miranda, Pitillas, Tafalla and Ujué for the Middle Zone case study.

The processing of the qualitative information is inspired by the procedural

systematics of grounded research (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) (codifying, recurrent

comparative analysis) albeit without necessarily assuming the presuppositions of an external objective

reality. The codifying procedure included a combination of inductive and deductive operations. The first

fieldwork had previously identified processes that were then sought to be verified in the second fieldwork

(vulnerable profiles, family strategies, use of everyday mobility, etc.). Additionally, any issues arising

from the latter fieldwork on the experience of the rural gap and welfare access were traced and recoded in

the interviews from the former. To ensure the fidelity of the verbatims literal transcription were made,

which were checked by listening back to the audio recordings. Code labelling was applied paying special

attention to the significant fragments of conversations, ‘emic’ expressions and conceptualisations,

anecdotes that could be studied as analysers and explanations that were particularly illustrative. By

means of successive readings, a more selective recodifying was organised, oriented to making patterns of

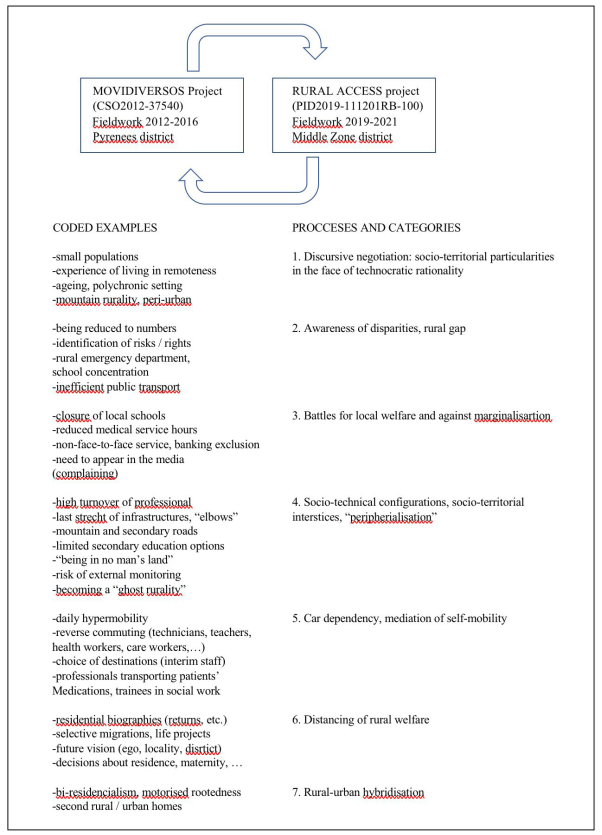

processes and interpretative categories visible (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Codifying procedure, examples and interpretive categories

Table 1 Summary of the fieldwork.

| |

Pirineo |

Zona Media |

| Fieldwork dates |

2012-2016 |

2019-2021 |

| Interviews conducted |

22 |

23 |

| Experts and key informers |

8 |

14 |

| Chosen sociological profiles |

14 |

9 |

| Women interviewed |

11 |

18 |

| Men interviewed |

11 |

8 |

| Young persons interviewed (under 35

years old) |

7 |

8 |

| Interviews in small municipalities

|

11 |

7 |

Observation contexts (case studies)

The observation contexts respond to typologies of vulnerable scenarios that can be

synthesised as examples of areas that are “rural remote” and “rural peri-urban”. Their comparison with

other international experiences reinforces the consistency of a case-based risk and fragility that is

summarised in the indicators elaborated for Table 2 following the district limits

established by the 2019 Local Administration Reform Law of Navarre.

Pyrenees district

Territorial vulnerability and accessibility acquire particular importance in

mountainous areas, which often include a border and peripheral location as well as their geographical

conditions with respect to centralised economies in many European countries (Spanish

Association of Mountain Municipalities, 2017). The district in our case study is representative of

these and other processes inherent in rural remote areas (remoteness, population dispersion, scarcity of

housing and jobs, limited services, ageing). It is made up of 30 municipalities in different valleys and

which usually comprise several population entities, and has a total population of fewer than 5,000

residents. Almost one quarter of the households are made up of people over the age of 65 living alone.

This age group accounts for over 40% of the population in nine of the municipalities. The area is also

highly masculinised, with ratios of 135 men to 100 women in the 16- to 64-year-old group in 2021.

Its demographic fragility is reflected in the loss of almost one fifth of its

registered population in 2007, and that issue is identified in the participatory processes of the

Mountain Development Consortium (Cederna-Garalur, 2012a, 2012b) as

being its main threat. In contrast to other districts in Navarre it has significantly lower poverty

rates (Laparra, 2015; Government of Navarre, 2020), a greater

proportion of its population has a university education and there are low percentages of groups from

other countries. Accessibility is sustained by the private car, with its high motorisation rates

reflecting strong dependence. The trip to the regional capital city requires travelling on mountain

roads which could entail journeys of up to one and a half hours.

Figure 2 Location of case studies: Pyrenees and Middle Zone districts.

Source: Physical map of Navarre CC WIKI. Government of Navarre. Own elaboration.

The Middle Zone district

The typology of rural peri-urban area has been singled out due to its mixed uses

(productive, residential, infrastructures), administrative divisions, and the diversity of its

sociological makeup (Bossuet, 2006; Hoggart, 2005; Champion and Hugo, 2014). They constitute territories that have not been subject to

specific policies and are normally treated as anomalies to be resolved in the rural-urban gap (Gallent, 2006; Ravetz et al., 2010). The amalgamation of processes

and spaces ends up concentrating the risks and vulnerability of the interstices of low accessibility.

Our case study, the Middle Zone, covers a territory crossed by a toll motorway and

consisting of 19 municipalities, some of which are made up of scattered nuclei, to the south of the

regional capital city. Only four of the municipalities have more than 1,000 inhabitants and eight have

been classified as being at risk of extreme depopulation (Government of Navarre,

2021). The district has a total population of 26,332 inhabitants. Over one third of the residents

in half a dozen municipalities are aged 65 and over, and the masculinisation rate in 2021 was of 110 men

for every 100 women in the 16- to 64-year-old age group. A significant proportion of the population have

no secondary education and persons from other countries have a significant weighting there. The rate of

the poverty risk was over 25% in ten of its municipalities in 2019 (Statistics Institute

of Navarre, 2020), all of which are located in the sub-areas furthest from the toll motorway and

are dispersed (Sierra de Ujué-Pitillas, Aragón-Caparroso, and Valdorba-Barasoaín) and that we shall pay

particular attention to. The personal car is also the main means of transport, exceeding the regional

average motorisation rate.

Table 2 Basic indicators of the study districts.

| Indicator |

Pyrenees |

Middle Zone |

Navarre |

| Number of municipalities |

30 |

19 |

272 |

| Population (2021) |

4.932 |

26.332 |

661.537 |

| Density |

4,1 |

27,5 |

67,4 |

| Population variation (2001-2021)

|

-19% |

-1% |

9% |

| Population ages 65 years or older

(2021) |

33% |

23% |

20% |

| Single-person households aged 65

years or older (2019) |

22,6% |

13,6% |

11,3% |

| Population born abroad (2018) |

5,0 |

12,5 |

14,3 |

| Masculinity rate (2021) |

123 |

104 |

98 |

| Population with primary level

education (2016) |

15% |

23% |

17,3% |

| Population aged 16 years or older

with university education (2016) |

28,7% |

23% |

31,4% |

| Motorisation Index (cars per 1,000

inhabitants) (2019) |

600 |

520 |

498 |

Daily battles against marginalisation

Socio-territorial fragility demands permanently battling against the criteria of

market efficiency and rationalities of planning in spatial production processes (Lefebvre,

2013). Definitions of periphery, sustained by economic logic and demographic weight, are confronted

with habitual local resistance. In our field of analysis, regional diagnostic documents themselves, such

as the Territorial Observation of Navarre, recognise the issue when they ask, “How would the population

react to a possible merger or absorption of municipalities? How should that need be transmitted?” (Government of Navarre, 2011, p. 29).

The risk of deepening a peripheral status is the main threat facing territories that

are already seeing depopulation. The narratives gathered in the Pyrenees, for example, warn of the danger

of becoming a ghost rurality, with few permanent residents and who are increasingly monitored from afar

due to the privatisation and recentralisation of services. In the Middle Zone, processes are highlighted

that repeatedly configure the zones that are far from the toll motorway as being redundant interstices

where the interest in covering the last section of the infrastructures declines: “we are like in a sort of

hole, then, really bad, there is no cover in the village” (ZME09). As the mayor of a municipality excluded

from the gas network and broadband internet cabling explains, these areas make up “what I call the ‘elbow’

[he mentions three municipalities]” (ZME19). The same ones where a new remodelling of the emergency

medical services forces the inhabitants to travel to another clinic, in the opposite direction to the toll

motorway which finally goes to hospitals and medical specialties in the regional capital city:

“it is illogical (…) the only thing you do is to drive for kilometres”

(ZME19). The shortage of jobs and housing is complemented by the withdrawal of services and the

disconnections, dramatically reducing their capacity to retain young people and public employees in the

district. The headmaster of a secondary school with over 30 teachers confirmed: “every year 70% of the

teachers change” (ZME12).

These daily battles against marginalisation are presented as a fight that is fraught

with failure. As the previous interviewee recalled: “there is a concept in Education that is a ‘centre of

difficult provision’. So, the [temporary] teachers sign up for three years (…) we have applied for that

several times and they have rejected it” (ZME12). In the Pyrenees, pre-school, primary and secondary

education were all concentrated in one school in each valley. In the subareas mentioned in the Middle Zone

they closed schools in three municipalities and in another two they managed to keep them open with the

last-minute arrival of migrant families from other countries.

But this struggle is also illustrated in a huge variety of situations, where the

people employed in public services turn to the media to highlight the shortcomings and dysfunctional

aspects of welfare in their areas. They do this to provide a specific place for the doctor’s clinic (then

shared with the leisure society) (PNE10), to include a caregiver on the school bus in the mountains

(PNE17), or to demand the construction of the promised new school building (PNE06).

On the other hand, the fieldwork revealed dynamics of cumulative causation that

concentrate vulnerability in certain social groups and territories. As found by research in other parts of

Europe, the professional qualification of younger groups in these environments supposes a transition

conditioned by the lack of local options and the absence of effective public transport, which requires

accepting it from the unequal opportunities that social class affords them. Those persons without family

resources, as a social worker summarised, “they end up in no man’s land (…) if they don’t have purchasing

power, er, they have no option” (ZME22). In these cornered areas, converted into interstices, “elbows” and

“no man’s land”, welfare is devalued as a closure of horizons. As the Headmaster of the mentioned

secondary school commented regarding these limited post-compulsory education options in the area, “there

was a girl sitting down over there, for example, who wants to study artistic subjects, and it’s totally

impossible. Because of course, either you go to live in Pamplona or (…) but she needs…, it costs a lot of

money” (ZME12).

Where proactive indignation provides evidence of more deep-seated awareness of

territorial rights and inequalities, and thus the unease is more visible, is related to health care and

schooling. Both services act as catalysts and referents that mobilise people against the erosion of

welfare. The most significant example in the case studies was undoubtedly the Popular Legislative

Initiative (PLI) promoted from the Pyrenees district against the regional reform of rural health emergency

services in 2013. A decree was issued by the Government of Navarre that reduced the number of regional

health centres from 40 down to 17 and kept just one localised team in the western Pyrenees valleys. The

councils and health care professionals in the zone then promoted a proposal for a minimum law that

received the support of 170 municipalities in Navarre. Despite not being passed by the regional

Parliament, it did nevertheless succeed in repealing the reform, and also changed the social and

institutional perception of the problem of rural welfare.

The criteria and technical discourse of the decree confronted with the proven

conditioning factors in professional performance of health services and the singularities of the

territory: “particularities of a Pyrenees zone, where we have a road, you know, a mountain road, where

very often the climate prevents us from doing what we want, where the standards, it’s no good saying 15

kilometres, it takes me 5 minutes to get there” (PNE10). The promotors of the PLI also contextualised the

risks of socio-territorial vulnerability in the important casuistry of chronic and time-dependent

pathologies (stroke, heart attack), which is combined with a dispersed habitat and the highest rate of

over-ageing in the region. As a local doctor explained: “they said, no, as they are very small villages

and the probability and the statistics are there (…) well, we go back to the localised duty. And you say,

and where is the fairness?” (PNE15).

Subsequently, the pandemic ended up showing the structural weaknesses consolidated in

these rural peripheries, due to the low replacement rates in public services under the austerity policies.

With the new scenario brought on by the health crisis, the prolonged substitution of face-to-face health

services by telephone or telematic care led to the Middle Zone municipalities mobilising. On this occasion

they demanded the recovery of opening hours, the provision of services in local clinics and maintaining

the night-time emergency clinic in the district main town: “that was the reason for the protest (…) they

take days away, and they take hours away from us, [but] we have an aged population who have to go to the

doctor a lot” (ZME19).

In parallel, the digitalisation of many services (banking, health care, applying for

aid…), which accelerated in the pandemic years, reinforced the perception of a progressive

dematerialisation and distancing of rural welfare. Its impact also then brought to light the isolated and

dispersed poverty in the territory, now made visible by processes of exclusion. As one social worker

summed up regarding the multiplication of care tasks and mediation that this double impact of the digital

divide entailed: “the work we are having in Social Services is this: attending people who have

difficulties in accessing services” (ZME08).

Mobility as a measure of rural welfare

In landscapes of distanced services and opportunities such as those we have analysed,

participation in welfare appears to be substantially conditioned by mobility. The limitations of public

transport further reduce the possibilities to only those having a personal or family car available. In

fact, without that resource, social programmes take on an exclusionary drift. One social worker warned of

this aspect with regard to the need for centres for the elderly and dependent people which tend to be

located in a district’s main towns, “daycare centre, but with transport (…) because if you have to have a

relative specifically to take them and pick them up, well, very often, that is inviable” (ZME05).

The experts interviewed repeatedly identified those immobilised profiles, with

dependent mobility, or those who suffer from mobility poverty as being the elderly, women who do not

drive, young people without resources and migrant families. These groups do not have the same

opportunities as the rest: “Maybe they have a combination to go at seven in the morning and to come back

there is one at eight in the evening. Then, a person, for example who has a medical appointment here,

wastes the whole day (…) with the physical toll that that entails” (ZME22). Not having a car can, for

example, limit the possibilities of benefitting from certain social programmes, as one social worker

illustrated with regard to a protected job list: “we have a domestic service list and we find it very

difficult to cover (…) in the most rural zones (…) you must have very, very, very open availability, (…) a

car, a driving licence” (ZME05). Similarly, a family worker contracted by the Home-Help Service [Servicio

de Ayuda a Domicilio] (SAD) who travels to different municipalities, explained the difficulties in

providing a service that is conditioned by population dispersion, orography and the forced use of her own

car: “care hours are assigned depending on the dependency (…) to get to all the villages, we waste time in

travelling between them (…) And then, the roads are not very [good]” (ZME08).

This “mobility poverty” also opens the door to “health poverty” (Douthit et al., 2015) and the effects of “distance decay” (Manthorpe and

Livsey, 2009). Depending on the burdens and makeup of the family group, access to services may even

require the participation of several teams and drivers. As the interviewee from the Navarre association

for persons with intellectual or developmental disabilities (ANFAS) noted, regarding the difficulties for

rural families to access courses and activities in the district main town, it requires to “be on the road

all day, with what that means for the child, with what that means for the parents, because it is, it is

exhausting (…) many times they have to leave work, the grandparents have to bring them” (ZME23). In this

sense, demographic ageing constitutes a significant challenge for rural welfare in the medium term. The

growing need to travel for some groups who progressively lose their autonomy (for care, medical checkups,

purchase of medicine) entails, when the family network does not exist or is not present, a major impact as

a “distance decay”.

The public services staff in these territories are often forced into a special

relationship with mobility. On the one hand, they must learn to resolve the range of unforeseen situations

in which mobility poverty manifests itself on a daily basis. For instance, they explain that they take

medicines from the pharmacy in another municipality for the families they help, transporting trainees from

social programmes or patients going to the health centre in the district main town in their cars. One

nurse expressed the need to carefully plan appointments for medical specialities in the regional capital

city for those persons of vulnerable profiles who depend on the frequency of the regular bus service: “we

have to manage the hours very well (…) the professionals have already realised this, we know who will not

be able to go in their car because they don’t have one” (PNE10). On the other hand, this mediation

established by self-mobility considerably conditions the provision of services in dispersed settings and

even the professional performance itself may require intensification. As one woman interviewed in the

Pyrenees mountains: “in one study that was done, I am the second (…) nurse who does most moving around in

Navarre” (PNE10).

For the young groups who live in these socio-territorial peripheries, car access

entails a radical change in their horizon of opportunities and possibilities of rooting. The profiles

interviewed underline this transformation that involves managing the distance, hybridising local life with

urban opportunities and resources (PNE07, ZME09, ZME10, ZME15). Some of their narratives talk of the

transition from their experience as an adolescent trapped in small unconnected environments they

considered as “prisons”, to the new accessibility and independence gained by having their own car. This

overcomes a dependent mobility that must be adapted to public transport: leaving home well in advance,

waiting for connecting bus services in the main towns or waiting for the only bus to return from the city,

as well as the availability of parents or relatives to enable them to participate in after-school and

leisure activities. As one interviewee recalled about her training stage, which required continual

commutes to the capital city: “It wears you out, and you say, (….) I could do so much more, but there is

physically no more time” (ZME09). Another young woman reiterated on the period after finishing university:

“all the job interviews (…) they are always, everything is in Pamplona and I have to move about all the

time. Then, when I didn’t have the car it was all quite, (…) you have to leave home, well six hours before

[to get there by public transport]” (ZME15).

A plan has only recently been developed in the Middle Zone to provide a skeleton

service to over a dozen places that lacked public transport (trunk lines, radial lines, on demand) (ZNE07)

as the companies contracting regular transport lines in the region had kept preferential rights to new

lines (PN19). But the municipal authorities also tried out unconventional formulae, such as subsidising

taxis on demand or the Valdorba home-care service (ZME08). Some private itinerant services (hairdressing,

chiropody or physiotherapy) are gaining prominence in the Pyrenees, such as the Eutsi cooperative, which

provides services for the elderly population with workshops in the villages and the availability of

transfers by car for those persons who have difficulties.

![]()

![]()