Texto escrito en el marco de la Unidad

de excelencia

científica FiloLanb-UGR. Este artículo forma parte de los proyectos de investigación

"Institución y

Constitución de la Individualidad: Aspectos Ontológicos, Sociales y de Derecho"

(InCOn)(PID2020-117413GA-I00) y "Desacuerdo en actitudes. Normatividad, desacuerdo

y polarización

afectiva" (PID2019-109764RB-I00).

INTRODUCTION

This article has two main parts: the reading of the courses that Pierre Bourdieu (2013) dedicates to Manet, which shows us a model for symbolic

revolutions, and the

analysis of one of these revolutions in the contemporary Spanish intellectual field, which

justifies some

nuances and a clarification of Bourdieu's model in relation to the academic role in these

revolutions. For the

first part, we will highlight everything that contributes to a sociology of philosophy in

Bourdieu's courses: in

the development of his lessons, Bourdieu uses examples derived from philosophical discourse and

the challenges

that arise from confronting it sociologically. The parallelism with the sociology of philosophy,

therefore, is

imposed by the author himself. In the second part, we will broaden the perspective by including

examples of our

own research on contemporary Spanish philosophy.

One key aspect in the article is the effect of the academic institutions on

the cultural

production. We will try to clarify how Bourdieu’s Manet helps us to understand

fundamental aspects of the

genesis and functioning of the scholastic attitude in art and philosophy. This work should be

read in continuity

with three further works (Moreno Pestaña, 2013 and 2016;

Costa Delgado, 2019) in which another (not scholastic) model of practicing

the history of

philosophy was explored, fundamentally by discussing Ortega y Gasset’s works from the 1940s and

1950s and the

Generation of ‘14. Specifically, in regard to Bourdieu in particular and to the sociology of

culture in general,

a series of parallelisms is reconstructed. The first section helps to understand the material

conditions for any

symbolic revolution, and it shows how Bourdieu applies the same scheme that he used for other

processes of

cultural creativity. After that, we analyze what Bourdieu means by scholasticism and what

characteristics a

scholastic disposition has in cultural production, particularly in painting and philosophy, to

expose, in the

third section, a specific reading of the intellectual creator on the basis of Bourdieu. Thus, we

will see how a

creator can break with scholasticism and revolutionize the way of understanding painting or

philosophy. The last

three sections, dedicated to the Generation of ‘14 in Spain, will show how the features of

symbolic revolutions

can vary according to the historical context, what will help us nuance the model of symbolic

revolution and the

notion of scholasticism constructed by Bourdieu based on Manet’s case.

THE SYMBOLIC REVOLUTION

Bourdieu (2003, p. 131) states that there is a general model for all symbolic

revolutions. We

are going to explore it by referring to the study dedicated to Manet, his most specific work (Bourdieu, 2013). He has reflected on that question at least since 1971,

although the topic is

already present in his early work on Algeria and the economy of symbolic goods (Sapiro, 2016, pp.

91-92 ). In a fundamental work for his perspective, Bourdieu (1971a, p.

334) points out

the difference between political revolutions and revolutions that modify the way of judging and

perceiving the

world: the symbolic ones. Although the former need the latter, they do not always integrate

them. We find

identical statements in later works, for example regarding the difference between economic and

symbolic

transformation (Bourdieu, 2012, p. 234). Symbolic revolutions know different

scales ranging

from localized spaces -for example, pedagogical relations (Bourdieu, 2012, p.

274)- to

structures of enormous historical scope, such as the modern state (Bourdieu,

2012, p. 226) or

the crisis of the family related to the feminist or gay movement (Bourdieu, 2003,

pp. 152-153;

Bourdieu, 2016, p. 228).

All fields do not have the same logic, which is why we will refer below to

certain specific

features of the philosophical field as opposed to the field of painting or literature. In The

Rules of

Art, Bourdieu studies the literary field, but at the same time he affirms that this

study supposes a model

that can be extrapolated to other fields, obviously prior empirical work, which in our case

refers to the study

of the Generation of '14. But before going into more detail, let us present the central features

of the symbolic

revolution.

Bourdieu begins to analyze demographic changes. The increased number of

students produced a

transformation of audiences that had been previously restricted. The bohemians were, in France,

an artistic

entity shaped by factors genuine to the Hexagon: political history (with the joint effect of the

Revolution, the

Restoration and the Empire) brought about a turnover of administrative staff, who seized power

at a relatively

young age. Furthermore, France’s centralization imposed the concentration of aspirants in Paris:

the capital is

the place where cultural capital -among others- is accumulated. The political elites, on the

other hand, were

strongly prevented against the social mobility produced by culture and the deleterious effects

of the Arts and

Humanities on the perspectives of the middle classes: Frédéric’s trajectory, the hero of

Sentimental

Education, unforgettably described by Bourdieu (1998, pp. 19-81) in

The Rules of

Art, is an ideal type of this period. The ambitious youth of the middle classes, unable

to settle for

their position, shifting from politics to art, represent a wind of social Fronde,

although very

politically ambiguous (Bourdieu, 2013, pp. 243-246; 2016, pp.

584-585).

Bourdieu does not mention it, but he seems to use Norbert Elias’s model

(1989, p. 71) in The Civilizing Process as a reference. Elias described, during

the

18th century, the exclusion of the German intelligentsia by their national elite,

which stood in

contrast with the centripetal character of the French Court. The 19th century in

France, however,

witnessed how the expectations -stirred up because of political changes on the turnover of

cultural and

administrative staff- were brutally shut out and the situation started to look like the one in

Germany in the

previous century. The dramatic growth in the cohorts that could access the educational system

confronted

graduates with their dashed hopes and, just like in May 1968, those who held the greatest

expectations were the

ones who experienced it the most. Just like Randall Collins (2009, pp. 791-797)

, Bourdieu

considers that scholastic repetition only works when the material foundations (economic,

institutional,

disciplinary) remain unaltered. When these get out of place -for instance, with the arrival of

not integrated

candidates-, there is a possibility of intellectual novelties breaking in.

What did the world of dashed hopes invent? The pseudo-proletarian

intelligentsia (Max

Weber) or a basic layer of the lumpenproletariat (in a note of 18 Brumaire, Marx included

bohemians

there, as Bourdieu recalls). Rejected, they did not go home; quite on the contrary: the

rejection triggered an

enormous process of multiplication of instances of academic consolation (schools, publishers,

journals,

colloquiums…). Such parallel symbolic markets went by their own momentum against an art that was

fully

controlled by the State, which worked as an apparatus. A mass audience was also born, as the

school system

provided for more producers and consumers. Bourdieu does not attribute any features of salvation

to this new

audience. Bohemians represent the empire of opportunists, of the rejected by the Salon and the

Academy who wish

they could have entered, of the mandarins who sense changes and switch sides…

This audience did not understand that Manet explored low-prestige themes,

since the power of

the norm lies in saying what is susceptible of being art and what is not, what is a big theme

and what isn’t,

what is, on a different level, an important philosopher and what isn’t, what is a fundamental

historic event and

what is a bagatelle: bohemians, despite their turbulent character, could still defend the canon

(claiming to be

better than the ones who were in it) or replace the privileged poles while maintaining the

hierarchical system.

Spaces opened up, audiences changed, France’s political history generated a political apparatus

too centralized

and distrustful. In Manet, the state always appears linked to a routine norm that

introduces heteronomy

into the artistic field, although this is not the only logical and empirical possibility: on

other occasions, a

state intervention can reinforce the autonomy of a specific social field. We will show how

fractions of the

field of state, also influential in the intellectual field and linked to processes prior to

themselves, promoted

the symbolic revolution in the Generation of '14.

However, bohemians by themselves, they don’t explain it all. Replete with

loose cannons,

speculators and tricksters, Manet could not rely on this group to build an alternative instance

of consecration.

Because this is exactly what any creator needs: someone who assures him that he is not mad, that

he is not an

impostor pretending to be cursed. Bourdieu always insisted that social conditions enable a

symbolic revolution,

but do not determine it absolutely (Bourdieu, 2013, pp. 389-396; Bourdieu,

2017, p. 615): it is necessary to understand the specific logic of the production space

in which the

author in question is located and what the author transforms in it. In the next sections, we

will try to provide

an answer to that question: what conditions does intellectual autonomy possess according to

Bourdieu and what

allows it to resist academicism?

SCHOLASTICISM: THE INFLUENCE OF SYSTEMATIC INSTITUTIONS ON CULTURAL CREATION

Bourdieu is confronted with the scholastic attitude because, even in its best

versions, it

is the main obstacle to a historical sociology of art. What do we understand by scholasticism?

In principle, it

is the set of dispositions generated by academic experience and, very remarkably, the liberation

from practical

urgencies

1

. This liberation from the demands of daily life comes with the submission to the

exclusively academic

demands and tends to be projected towards all the works of culture and, in general, to the view

on the social

world.

Nonetheless, Bourdieu leaves some questions open in his identification of

scholasticism. On

the one hand, in a specific sense connected with the production of academic habits, he

identifies as scholastic

the art dependent on a school (Bourdieu, 2012, p. 168). In more general

terms, he considers

the dehistoricized reading that characterizes commentators as scholastic (Bourdieu, 2012, p.

106). Bourdieu rotates between explanations without being clear: sometimes he seems to

preach the

academy’s scholasticism; then, scholasticism is equated with dehistoricized commentary, which

only pays

attention to the works and to whatever can be deemed worthy or unworthy in them with respect to

the canon.

The doubt could be resolved by trying to clarify Bourdieu himself, which is

always a risk.

We could get out of the problem by pointing out that scholastic criticism entails an

intellectual reading of all

practices: obviously, those practices arising from the academic institution itself, but also

other practices

that have nothing to do with it and even break away from it, philosophical and artistic

practices that are

different from commenting philosophical texts or exhibiting one’s mastery on the canvas. There

is an identical

anxiety underpinning the young philosopher who wishes to guarantee his status by comparing

Merleau-Ponty with

Husserl (though without studying the ideological and intellectual crisis of Catholic

philosophical societies in

the 1930s) and the reader of Manet who only allows himself to talk about the Venus of Urbino

(but not about the

socio-demographic shifts of the symbolic revolution): not tarnishing the canon with social or

historical

problems which are by definition excluded from it. These practices share a similar disposition

to that of

artists or philosophers who reproduce dogmatic patterns in their works dictated by an

institution which,

protected by tradition, ignores the social and historical genesis that gives meaning to the

practices that are

transmitted.

An important difference, however, can be established between academic art and

the artistic

field: in the latter, the specifically aesthetic skill is increasingly valued. This can also be

said of the

philosophical field in a certain sense, but in a much less explicit way. In academia, both in

philosophy and

painting, the norm stemming from the scholar universe is irresistibly established, to the point

that it ends up

conceptually wasting art itself or creative philosophies. When an academic writer reads a work

or commentates a

painting, he will always look for specific features: whether its finish is good, whether the

author is competent

according to the dominating pattern, whether the historical references are correct… But what

does he forget? The

fact that an innovative work harbors a tradition, but it also alters what was transmitted of it

and the uses by

means of which it was transmitted, connecting it with new uses or sensitivities, or even

recovering the living

richness of a tradition as opposed to its reificated version caused by academic routine (Bourdieu, 2012, pp. 355-364 ). Therefore, he proposes a new way to read

history, a new way to

define the finish of works, a new way, in sum, to define the artistic, literary or philosophical

skill. In this

sense, as Bourdieu reminds us, when Manet sought to be admitted in the painting canon, he

intended something

impossible: for the canon to accept what was going to destroy it. In sum, in order to be loyal

to authentic

iconological or conceptual innovation, the history of artistic and philosophical creation needs

to invoke much

more than just icons or concepts. Manet’s symbolic revolution was indigestible for scholar and

scholastic

reading devices (Bourdieu, 1998, p. 172).

READING DIFFERENTLY, WITHOUT SCHOLASTIC MUTILATION. BEYOND THE QUESTION OF

BREAK AND

CONTINUITY

Bourdieu’s argument about the symbolic revolution reminds us of a thesis by

Randall Collins (2009, pp. 150-151). After comparing Greece and China between

500-300 BCE, Collins

confirms the existence of twelve creative generations in the former and a shorter sequence in

China. Chinese

authoritarian patterns imposed legitimation in a way that Athens never did, where Plato could

develop his

philosophy without trouble, despite it being completely hostile to democracy. In the case of

France, the

creation of alternative markets allowed for the survival of intellectuals in conflict with the

norm. England,

with its arriviste and submissive artists, draws analogies with the case of China’s Confucian

unification,

although in a more decentralized way. Paris and Athens have two things in common: the

concentration of the space

of attention and the possibility of a competitive intellectual market not severely monopolized

by any political

institution, which facilitate ties between schools, debates and rivalries. Without them,

intellectual life can

perish due to dispersion and to the absence of a critical mass.

But we still have the problem of what revolutionizes the revolutionary. In the

first place,

revolutionaries do not reject tradition: rather, they proof that orthodoxy misunderstands it.

Manet had the

history of painting embedded in himself and therefore, he was able to rescue Velázquez against

the art

pompier of his time. His contemporaries, who boasted of upholding tradition, actually

ignored it; in fact,

they only knew about it what the school administered, and the school always captures the past in

a biased way.

Bourdieu devises a magnificent formula: Manet proposed “a mobilization of the technical capital

that had

accumulated over the history of painting, but had been mutilated by academic selection” (Bourdieu, 2012, p. 355). Wherever there is a norm, continuities, consecrated

genealogies… the

revolutionary proposes new syntheses. At that moment, the academy loses its symbolic support

because, with its

actions, the revolutionary accuses it of separating what should not be apart and of uniting what

should be

separated.

In support of his thesis, Bourdieu (2012, p. 285) appeals

to the

description of Heidegger’s attack to the neo-Kantians. Although the analogies between the

philosophical field

and the artistic field come from Bourdieu himself, the peculiarities of the former must be

established. The

philosophical field, whose existence Bourdieu (2003, p. 34) traces back to the

fifth century

BC is characterized in the contemporary world by the constant loss of its own objects, which

have been

monopolized by specialized disciplines. In this sense, the philosophical field must always refer

to such lost

knowledge, to a large extent demonstrating its unacknowledged debts to philosophy (Bourdieu, 2003,

pp. 43-47). The relationship of philosophy with its tradition is not identical to the

logic of permanent

revolution that characterizes the fields of restricted production in art, where producers

produce for a public

of creators, with the inevitable mediation of intermediaries: critics, editors, gallery

owners... (Bourdieu, 1998, pp. 208-209). The specifically philosophical

activity consists much more in a

permanent rereading of tradition in order to confront present conflicts (Bourdieu, 2016, p.

571). Certainly, Bourdieu considers that any great creator knows the history of his

field. In philosophy

this is shown in a more intense and academically guaranteed way. In fact, it has been pointed

out that a

condition of belonging to the field is still the competence in the history of philosophy (Pinto,

2007, p. 65). This is something that is well verified in the case of Heidegger.

In Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics, Heidegger showed the primacy of

Aesthetics

and the intuition about the logical categories of knowledge and the foundations of science.

Time, which is

constitutive of imagination, lays the foundations for the subject of knowledge; therefore,

science is not

embedded in logic, but in a deeper experience: the specific, existential temporality (Bourdieu,

1988, p. 71 ). Similar to what Manet did with Velázquez with regard to the

pompier academia,

Heidegger proved neo-Kantians that they did not know their prince of thought. He also avoided

Jünger-like

essayism like the plague. Where Jünger -equivalent to the Parisian bohemians- invoked Nietzsche,

Heidegger went

back to the pre-Socratics (Bourdieu, 1988, pp. 47-48). Therefore, the symbolic

revolutionaries, like Heidegger and Manet, know the tradition but without its academic

mutilation, and precisely

because they know it, they distinguish themselves from the false revolutionaries, who are in

truth amateur

critics of academia (and this will always have an easy time to disqualify them).

Let us recapitulate: we have the crisis of the institution, with its plethora

of aspirants

who do not find their space and step forward to contest the mandarinate; in addition, we find

the creation of

new markets where to find support and, subsequently, we find a revolutionary who is particularly

well-educated

in the history of the field, be it Manet or Heidegger. And something enigmatic: we find a

tradition mutilated by

academia that allows the revolutionary to overcome orthodoxy (by precisely, using its forte: the

“sources”) and

to distinguish himself from the resentful criticism made by those expelled without much

competence (Bourdieu, 2012, p. 455 ).

However, in which way is tradition mutilated? To our understanding, this is

the key

question. Tradition is mutilated because it is dehistorized and it turns ancestors into

summarized and

stereotyped characters susceptible of academic transmission, into mere labels, a coherence that

ignores the

whole pragmatic effort that the creator had to deal with. We can mobilize here Ortega y Gasset

(2009, p. 730), who wonders about the temporality of thought and concludes that it

depends on pragmatic

situations and on how these -which unite thought and institutions- last through time. Bourdieu

himself states

something similar when he claims a “good use” of anachronism: when one has good general models,

the past can be

compared, always with precautions, with structural equivalents, homologous in certain

oppositions, but not in

others (Bourdieu, 2012, p. 360). This is an example of the mobilization of

tradition, but it

is a pragmatic mobilization that takes the thinker (or the artist) without removing him from his

time and

conflicts. The creator perceives the sociological and intellectual moment in which the

conjunction claims a

certain past. This, of course, is not taken from academic manuals: it requires to know more than

what they

contain, as well as knowing what in the concrete world claims a new reading of the past. The

creator is

possessed by the history of the field, as Bourdieu insists repeatedly, but he can also see the

objective

possibilities in the present. Is he an intellectual genius? Yes, but because he is a

sociological, even a

political genius. And that genius makes him a great painter or a great philosopher. Revolution

is not just

intellectual: it is also social. Otherwise, Bourdieu would take us back to the charismatic

ideology of the

creator. The creator can tell intuitively that there is an opportunity in a specific conjunction

of a new

articulation of tradition. Bourdieu (1998, pp. 222-223; 1988,

pp. 56-57)

insists that it is a collective process that cannot be made to depend on a single individual. As

Fowler (2020, p. 454) points out, Bourdieu puts forward an "anti-charismatic

conception of

social creativity" and, referring to the links between symbolic revolutions and politics, states

that "groups

create themselves by creating people who create the group". In the artistic field, Bourdieu

(1977b, pp. 5-7) argues that the value of the work depends on a circuit of agents that

go beyond the

writer or the painter. That said, there is no doubt that the creator is also an active agent who

strongly

resembles the prophet in the religious field. The prophet -or the creator- has nothing

extraordinary about him,

but he grasps the extraordinary situations and allows what was only among the virtualities of

the present to

exist (Bourdieu, 1971a, pp. 331-334). Moreover, Bourdieu (1998,

pp.

185-188) has tried to specify the social properties of the great creators: they are

subjects with a high

symbolic capital, often coming from dominant classes, but absolutely distanced from bourgeois

routines. We will

return to this question later, with regard to the collective subjetc of the symbolic revolution

in the

Generation of '14.

Thus, do we recover the theory of charisma? Not at all: the description of the

creator’s

social and financial resources shows in some way the collective work from which the individual’s

social

intuition emerges. The creator concentrates a whole network of collective work on a proper noun.

Favorable

comments about Manet’s paintings can be explained by its previous relations: he could fascinate,

indeed, but the

fascinated ones were in networks that were already well disposed to a warm reception. “The more

science

progresses, the more the charismatic myth disappears” (Bourdieu, 2013, p. 442

).

DIFFERENT WAYS OF INTERPRETING BOURDIEU'S MODEL OF SYMBOLIC REVOLUTIONS: CAN

THE ACADEMIA

CONTRIBUTE TO A RADICAL TRANSFORMATION OF CULTURAL PRODUCTION?

In the previous pages we have seen how scholasticism could appear in different

circumstances, though all of them express the discipline that some kind of external institution

imposes over the

space of cultural production. Now we would like to address one specific question: can the

academia have a

positive role in a symbolic revolution? As we have pointed out, we can find support for this in

works by

Bourdieu other than the one we have analyzed. In his course On the State, Bourdieu

remarks that the state

conditions, in collaboration or in conflict with the subjects of each field, the capitals that

function in each

social space. This can be done through the arbitrary imposition of bureaucratic rules, but also

by encouraging

the creation of autonomous environments, governed by their own rules (Bourdieu,

2012, pp.

196-197; Bourdieu, 1993, pp. 52-53). For Bourdieu, it is clear that

Manet's revolution

developed against the academy, but it is possible to think about a symbolic revolution whose

basis are supported

by a temporal institution.

For that to happen, the rules enforced by this institution should help a group

of creators

to resist the external influences threatening the authority of the very field of production to

stablish

principles of legitimacy over the system of relations of production, circulation and consumption

of the symbolic

goods that have a place in it. In order to affirm that this institutional intervention

contributes to a symbolic

revolution, in addition to supporting the autonomy of the field it must, paradoxically, promote

its

transformation and guarantee a space of relative cultural freedom.

Bourdieu (1971b, p. 50) proposes three dimensions necessary for the formation

of an

autonomous intellectual or artistic field: 1) the development of a market for symbolic goods,

which opens up the

possibility of economic independence and a principle of impersonal competitive legitimization,

free from the

tutelage of temporal authorities such as the aristocracy, the church or the state; 2) the

constitution of a

specialized group of producers and intermediaries of the symbolic goods in question; 3) the

multiplication and

diversification of specific and competitive consecration instances within the field.

Subsequently, this field is

structured in an opposition between two poles: that of restricted production, aimed at an

audience of producers,

and that of production aimed at the general public (Bourdieu, 1971b, pp.

54-55). Of course, Bourdieu (1971b, p. 49) reminds us, autonomy is

always relative and external pressures never

cease to exert their influence, although this is expressed with a variable refraction effect

depending on the

field's own categories.

We argue that these three dimensions are present in the case of Generation of

14' in Spain,

a group that played a fundamental role in a symbolic revolution that promoted the autonomy of

the intellectual

fields especially linked to the state through the university, as well as in the journalistic

field. In this

article we will focus on the philosophical field, although references to the effects of the

Generation of '14 in

other social spaces will be inevitable, given its interdisciplinary character and its active

-albeit unequal-

political involvement. In the following, we will briefly review

2

how the three dimensions of an autonomus field proposed by Bourdieu are expressed for the

philosophical

field in the Generation of '14:

Development of a market for symbolic goods: at the beginning of the 20th

century, a series

of cultural and socio-demographic transformations were observed in Spain that allow us to speak

of a significant

increase in the public of virtual consumers of symbolic goods, observable in the expansion of

access to

university and in the transformation in the mode of generation of a relevant fraction of Spanish

elites. We will

devote the next section to this, using the study by Costa Delgado (2019) .

-

Constitution of a specialized group of intermediaries and

producers: if we take

institutional recognition as a relevant indicator, since the middle of the 19th

century, the different

scientific disciplines have been breaking away from philosophy, obtaining

institutional recognition as

autonomous studies in the university: in 1857, with the creation of a "Faculty of

Exact, Physical and

Natural Sciences", and in 1900, differentiating between "philosophical studies",

"literary studies" and

"historical studies" within the faculties of "Philosophy and Letters". The process

of specialization

accelerated in the following years, especially with the Second Republic (Niño, 2013).

In addition, the mode of access to the position of university professor was also

profoundly transformed

between 1894 and 1901, limiting the interference of political power in appointments

and introducing more

specialized evaluation criteria, such as studies abroad, the requirement that the

members of the tribunal

were "professors of a subject equal or analogous to that which is the object of the

competition", or the

delivery of a "original research or doctrinal work", in addition to the program of

the subject (Martínez Neira, 2014). In general, what can be

observed up to 1936 is a tendency to

impose meritocratic criteria specific to the university, in the face of the double

threat of political

interference (political parties and the church) and "recommendations" (social

capital). And, nevertheless,

this whole process had the variable support of different fractions of the political

field, including the

numerous institutional spaces that the members of the Generation of '14 conquered

throughout their

professional and political careers.

-

The Generation of '14 prevented scholasticism by avoiding the

imposition of an

academic orthodoxy, while at the same time fought against the ideological pressure

of an authority outside

the philosophical field. To this end, the Generation of '14 contributed to

multiplying the instances of

consecration specific to the field: along with the consolidation of an increasingly

autonomous pole of

academic consecration in the university, the members of the Generation of '14

participated in other

instances aimed at diverse audiences. There are three main ones: publishing houses

oriented to the

publication of scientific works; journals oriented to an intellectual public

-although not separated by

disciplines- and the daily press. Most of the publishing projects controlled by the

generational core

3

were characterized by their pretension of specialization and intellectual

level; the desire to

stimulate the demand of a public with a certain cultural capital; the

professionalization of the staff;

the use of technical advances in terms of material, management and advertising; and,

above all, the

attempt to generate a press autonomous from politics, in contrast to the

journalistic environment

characteristic of the Restoration (Cabrera, 1994). All this did

not prevent the

existence, throughout the generational trajectory and often within the same

subjects, of a permanent

tension between the vocation to address an audience of specialists and the vocation

to create a work aimed

at a broad public, normally materialized in journalistic and political

interventions.

Considering the above, we propose the case of the Spanish Generation of ‘14 as

an example of

a symbolic revolution developed through the academia, and not against it. Not every symbolic

revolution is made

against the academia from the outside. And so, the rejection of a castrating academia would just

be one of the

historical possibilities in which the creative autonomy against scholasticism is expressed. As

mentioned above,

here we adopt Bourdieu's view of academia as a set of public cultural institutions promoted and

financed by the

State, with the university in a place of special relevance. Of course, as every academia, these

institutions

enforced a set of rules that modified the cultural agents' behaviour in a very significant way,

either through

submission or rejection, in many different intermediate degrees. We believe that, in the case of

Spain at the

beginning of the 20th century, these temporal institutions were capable of producing a

liberating interference

in the cultural production, reinforcing pre-existing tendencies -and at the same time as a

result of them-, as

well as reinforcing the actions of specific agents -which, in turn, modified the orientation of

these temporary

institutions, in conflict and collaboration with other agents.

The case of the Generation of '14 allows us to explore a logical possibility

that Bourdieu's

model admits, but which is not present in Manet's empirical case. In the Spanish case,

the symbolic

revolution had the support of a fraction of the state in the face of pressures fundamentally

coming from the

political field (from positions of different ideological signs, but especially from the parties

of turnism,

which controlled the political power in Spain during the Restoration) and from the church, an

institution with

an enormous influence in the Spanish educational system. But does not such support from the

state imply a form

of interference from a temporary power that questions the autonomy of the field? We believe not,

as long as such

interference reinforces the autonomy of the field by positively influencing the three dimensions

previously

mentioned (Bourdieu, 1971b). The curriculum of the republican Faculty of

Philosophy and

Letters in 1931, promoted by significant members of the Generation of '14, is a good example of

this: the state

sanctioned an official curriculum that recognized disciplinary specialization, greater freedom

for studens to

choose a personalized curriculum and greater autonomy for teachers within the subjects to be

taught. These

measures were intended to put an end to the "intellectual rigidity of the system of university

chairs and opened

up the possibility of disciplinary innovation, as well as introducing a certain degree of

competition" (Niño, 2013, p. 96 ). One part of the academia used its

institutional power against itself to

counteract the scholasticism characteristic of the university at the end of the nineteenth

century.

Let us now turn to Costa Delgado’s study (2019) , with the

systematized

data on the origin and social trajectory of a group of intellectuals and politicians involved in

the Generation

of ‘14. This will help us to deepen our understanding of the collective dimension of the

symbolic revolution and

will concretize the sociodemographic aspects mentioned above.

BRIEF METHODOLOGICAL INTRODUCTION TO THE EMPIRICAL RESEARCH ON THE GENERATION

OF ‘14 IN

SPAIN

The statistical categories used in this section require an additional

explanation, since

they are based on materials from empirical research whose selection should be justified. The

Generation of ‘14

was a group of people who conceived themselves in generational terms, tried to act in a

coordinated manner

between 1910 and 1914, and continued to maintain close bonds and common practices until the

Spanish Civil War,

with the permeability that defines any social group in a complex society where social destinies

are not fixed

legally from birth. This group was characterized, sociologically, by its high cultural capital,

its links with

Madrid, its predominantly bourgeois background, its relative youth in 1914 and, what we find

most interesting in

this article, its major role in the radical transformation of the Spanish intellectual field in

the early

20th century, which we can define as a “symbolic revolution”. In short, such a

revolution can be

characterized by a greater intellectual autonomy from the political field and from the Church,

materialized in

the three dimensions mentioned in the preceding section, and the institutional recognition of

this autonomy,

with a rationalization of public administration that was accompanied by the transformation of

the recruitment

criteria for the civil service, especially at university. Of course, all this was accompanied by

a radical

transformation of the way of understanding intellectual production in the fields that were most

affected by it:

the various scientific fields closely linked to the university and the field of journalism;

although the

symbolic revolution also produced significant changes in other fields, especially the political

one

4

.

Costa Delgado (2019, pp. 53-76) elaborated a reasoned corpus as a starting

point for his

study of the Generation of ‘14. Here, the existence of two indisputably generational manifestos

-because of

their content and signatories, in 1910 and 1913- offers many advantages: it is a wide selection

that does not

fall back into an arbitrary preselection of relevant personalities; it responds to the group’s

internal criteria

in relation to a specific social context; the manifestos are published in two important moments

of the

constitution of the group as such, and they generated significant responses and controversies

following their

publication; in short, it is the public image that the group projected when presenting

themselves in society.

As far as this article is concerned, we will mainly use the treatment by

descriptive

statistics of a selection of variables from the signatories’ available data (there were 169

signatories of the

manifestos, out of which around 100 present available data). The population of this study is a

fraction of the

Spanish elites that stands out for its cultural capital, but the study had to place it, at the

same time, in a

broader social context: in relation to other fractions of the elites -particularly those that

stand out for

their economic capital- and to those social sectors excluded from the elites -popular classes

and petite

bourgeoisie without cultural capital. Hence, the categories do not pretend to be

universal or to reflect

essential properties of the subjects, but rather combine social class criteria with professional

ocupations

whose access was mediated by the possession of cultural capital.

For the categorization of social positions, the study has been inspired by the

variables

used by Christophe Charle (2006, pp. 19-30) . We have adapted them to the

Spanish case and

considered some social sectors that he excluded for different reasons. The grouping of subjects

into categories

is not representative of the whole Spanish society of the time; rather, it is adapted to the

characteristics of

the study’s population: very nuanced in terms of the internal social divisions of the educated

elites and with

much more heterogeneous categories when it comes to economic capital and the popular classes.

The latter two

categories are in the minority -though present- among the signatories, but they are more

frequent in their

social background.

Also, 1910-13 and the Second Spanish Republic (1931-36) are generational

milestones marking

the beginning and end of the generational trajectory. The first date responds to the signing of

the manifestos

and the beginning of many of the signatories’ public presence; the second indicates the

generational social

destiny before the break and radical alteration of the political and social order that came with

the Spanish

Civil War. In addition to these two milestones, we added the signatories’ social background,

collected from the

available data from their parents’ birth certificates and the available biographical news.

THE SOCIAL CONDITIONS FOR CREATORS: A STATISTICAL ANALYSIS OF THE

SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS

OF THE GENERATIONAL BREAK

What does the case of the Generation of '14 contribute to Bourdieu's model of

symbolic

revolution?

The characterization of academia as a social space based on the distance from

necessity and

practical urgencies had a strong presence as a normative ideal in the Generation of ‘14, as it

can be observed

in the recurring opposition between university professors and journalists, which structures

important debates

within the group. However, in this case, the symbolic revolution did not occur from the outside

and against

academia, but from a dominated part of academia against the institution’s conservative sector,

relying on a

bohemian group made up of young writers and journalists and, at least during its rise, on its

dominated

counterpart in the political field: the labor and the republican movement. The complex and

variable composition

of these groups generated in turn a receptive audience in face of a creative disposition prone

to breaking the

mold of an academia that was closed in on itself. If we resume the four defining

socio-demographic factors of

symbolic revolutions previously identified, we can better compare the contexts of the Generation

of 14's and

Manet. Let’s recapitulate: (1) crisis of the institution, (2) candidates without space and prone

to rebellion,

(3) new markets, and (4) revolutionary educated in the field, who renews it by recovering

tradition in an

original way.

-

The crisis of the institution is very present in both cases, with

a very strong

criticism of its sclerotization, lack of originality and lack of capacity of

renewal, attachment to

outdated traditions and disengagement from social matters that needed to be

addressed. However, whereas

Bourdieu’s criticism of the Ateliers in Paris presents them as a homogeneous

bloc in its

academicism, the university faced by the Generation of ‘14 harbored a minority that

anticipated some of

the breaks that would characterize the symbolic revolution and even paved her way by

introducing important

changes in the recruiting of professors and in the definition of their academic

trajectory. This is one of

the factors that explain that the revolution against academia was not staged from

the outside, but from a

part of academia, with external support, against the dominating sector of it.

-

The increase in the university student population in Spain in the

early

20th century and, at the same time, the spectacular rise in the

proportion between assistant

professors and full professors generated an equivalent to the situation of shortage

in employment combined

with a large number of candidates, but with a greater capacity of integration by

academia and the State,

since the parallel process of transformation of the political field from the

parliamentary system made it

difficult for the notables to put the apparatus of the State at the service of its

client networks and, as

a consequence, made possible a larger rationalization of the administration and its

recruiting system.

-

The emergence of new markets, in the Spanish case, presented

different forms linked to

that complex coalition between dominated academics, intellectual bohemians and

political opponents, but in

general it was characterized by a larger capacity to associate non-academic

audiences with a cultural

production from academia or, at least, from the academics linked to this symbolic

revolution. The

coalition took variable forms, including publishing projects which explicitly sought

-with mixed but

remarkable success- to generate new dynamics of intellectual production oriented to

large audiences,

looking for economic independence, quality and specialization of contents, formal

excellence, and an

efficient management (Cabrera, 1994).

-

The emergence of a revolutionary (in our Spanish case, a group)

educated in a field

that renews it makes a substantial difference, which is not at all present in the

French case: the

reference to Europe and cultural importation as a value in itself. The reason behind

this difference is

evident: internationally, the position of France and Spain in the symbolic hierarchy

was opposite. Whereas

France mainly competed with Germany and England as international cultural references

of the time, Spain

was part of Europe’s periphery, and its intellectual and political debates were

mediated by the

importation from metropolises. The Generation of ‘14 claimed to be importing the

European culture into a

backward Spain.

Let us now comment on the social composition of the signatories of the

generational

manifestos, with the aim of contrasting the hypotheses derived from Bourdieu’s model of symbolic

revolution. As

seen above, in order to explain the exceptional nature of the symbolic revolutionary, what we

previously termed

as “creative autonomy”, Bourdieu does not only allude to his cultural capital, but also to

“external” resources

outside the intellectual field such as his social capital -the network of previous contacts that

reacts

favorably to his production and disseminates it- and his economic capital -which allows him to

disengage from

practical urgencies and from the economic repercussion of being excluded from consecrated

spaces-. In sum, we

wonder: is it possible to imagine creative autonomy from social coordinates that are different

from Manet’s?

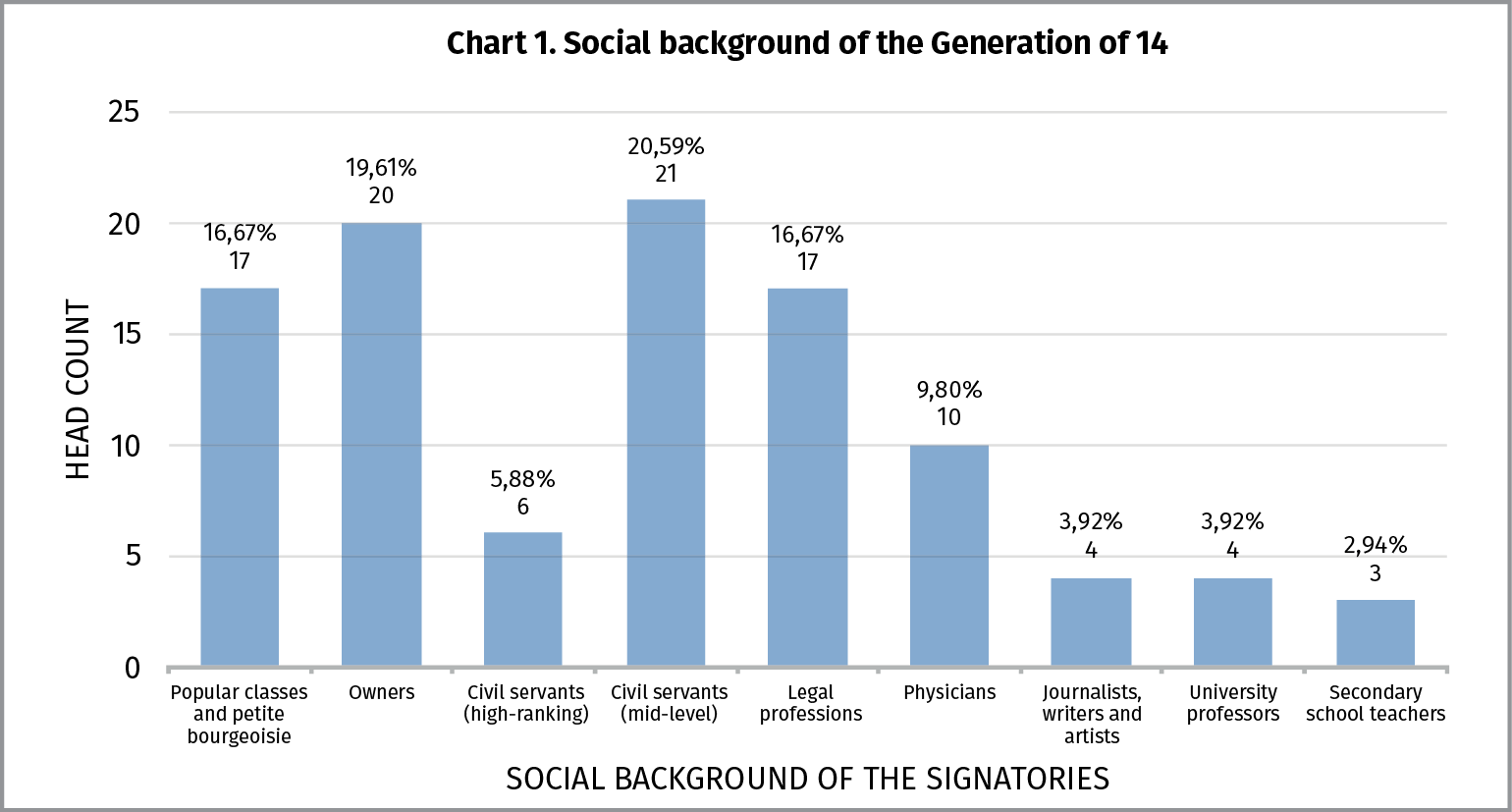

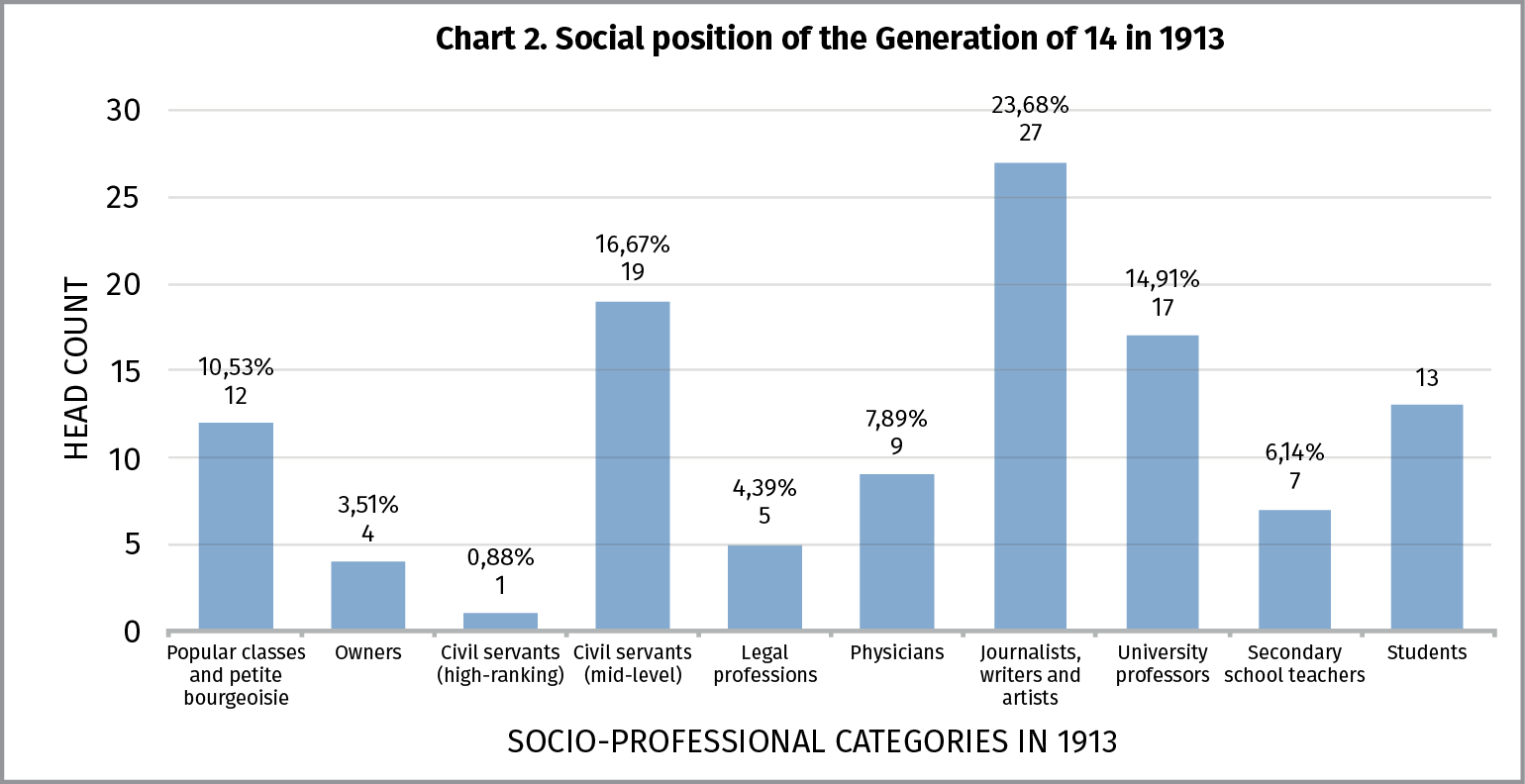

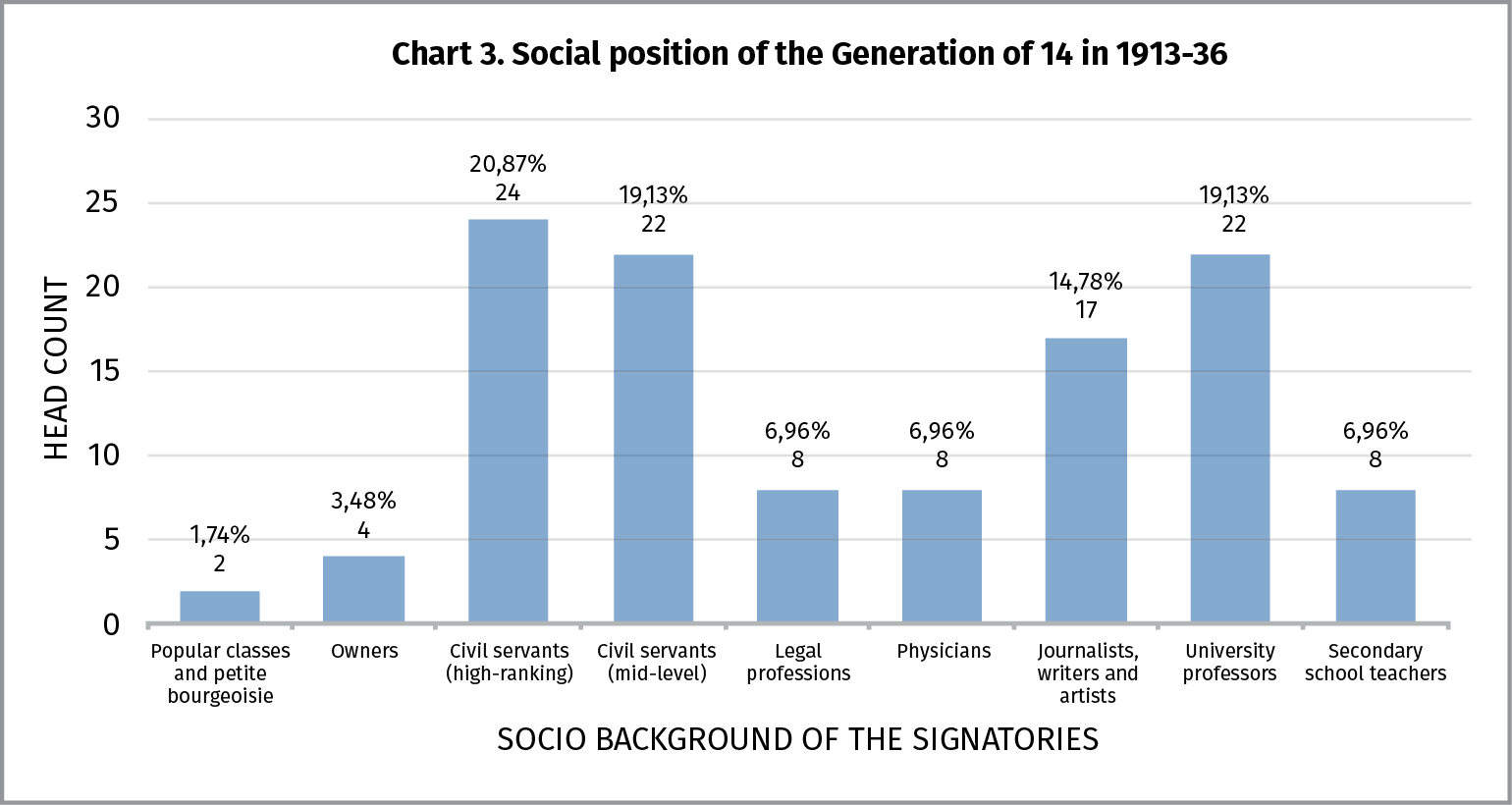

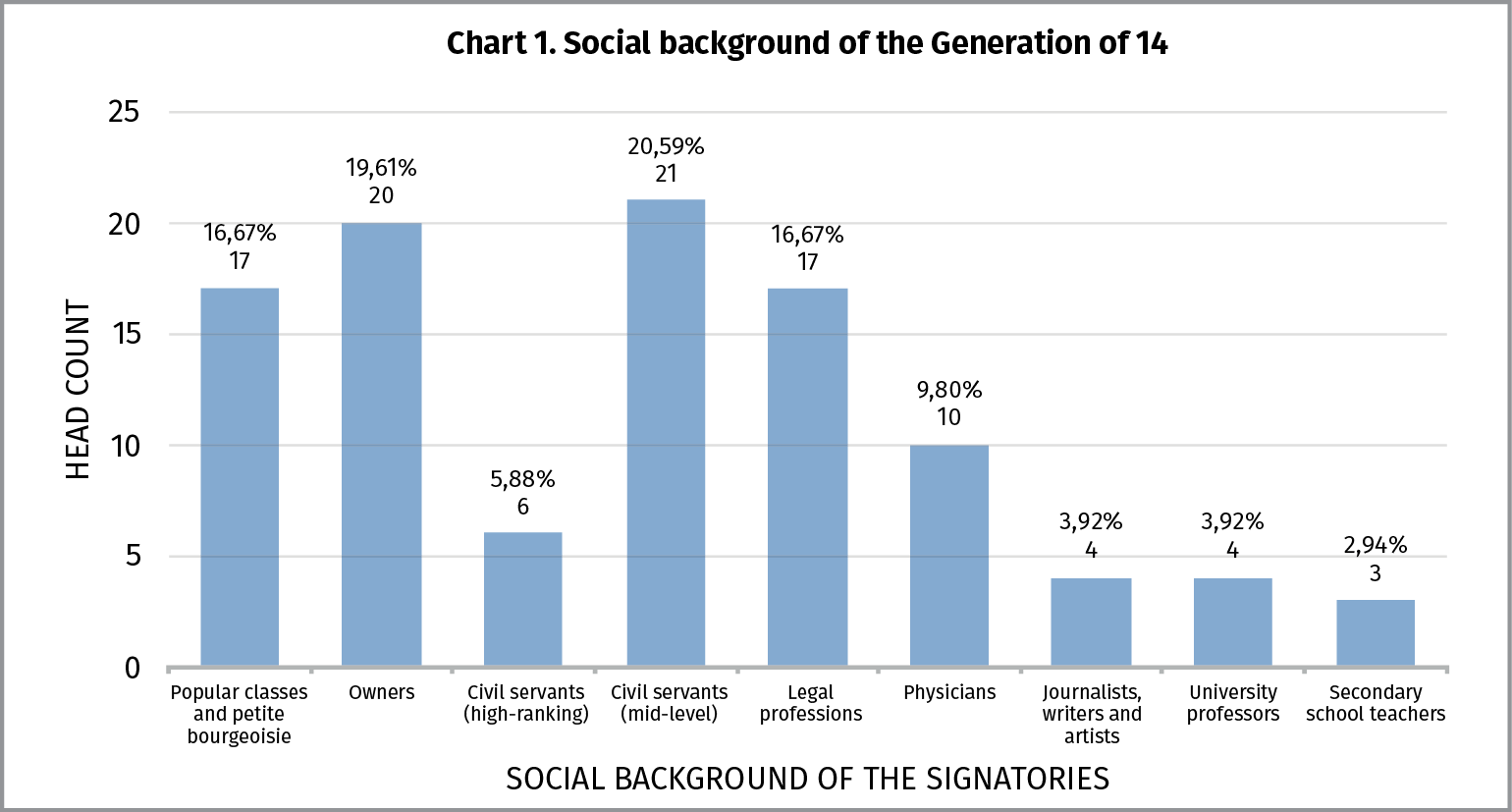

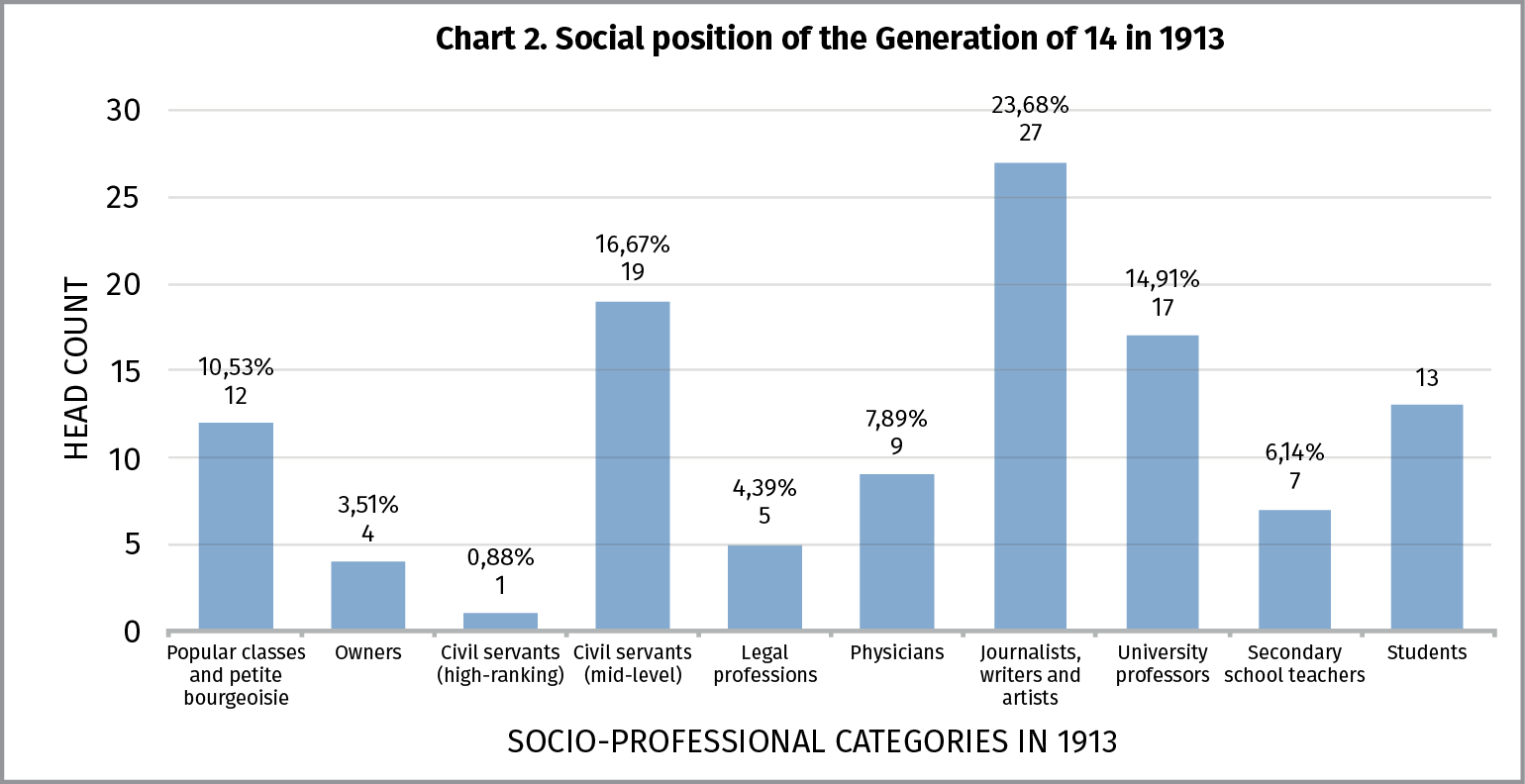

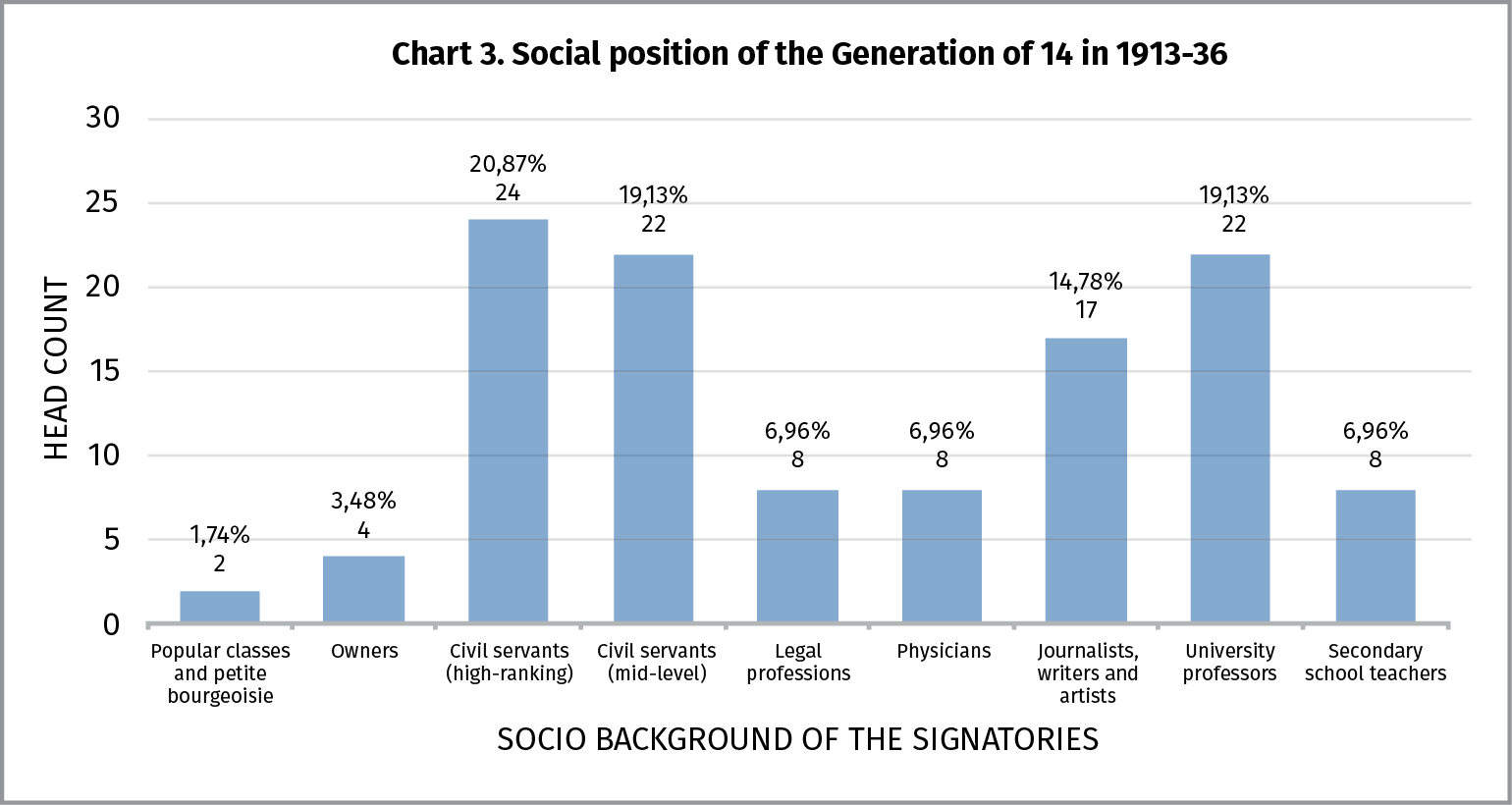

Let us look at three charts that depict the social trajectory of the

Generation of ‘14:

social background, social position in 1913 and social position during the Second Spanish

Republic (1931-1936) of

the signatories of two generational manifestos. Studying the differences between these three

milestones will

shed light on which type of social conditions were required to participate in the group and

which social changes

this concatenation of facts -which we sum up in the concept of generation- brought about to its

participants.

A comparison between Chart 1 and Chart 3

leaves no doubt

about the group’s evolution. In a family generation’s time, a limited upward social mobility

occurred, combined

with a conversion of economic capital into cultural capital, the latter being much more

prominent than the

former. The decrease in “Popular classes and petite bourgeoisie” compared to all the

other categories,

considering how this category is constructed in this research, shows that upward tendency in

terms of social

position. The variation in the proportion between university professors and secondary school

teachers points in

the same direction, although in this case, the social distance between both categories is much

shorter. A piece

of data that points towards the moderation of this social mobility is the fact that the

proportion between

mid-level civil servants and the sum of owners and high-ranking civil servants did not vary at

all. Changes in

legal professions and the category of “Journalists, writers and artists” are not good indicators

of social

mobility due to the great internal heterogeneity of these categories in terms of economic and

symbolic capital.

Chart 1. Social background of the Generation of 1914

Chart 2. Social position of the Generation of 1914 in 1913

Chart 3. Social position of the Generation of 1914 in 1931-36

The generational conversion of economic capital into cultural capital is

evident. The

enormous increase in university professors and secondary school teachers serves as an indicator

of the

importance of cultural capital in the social trajectory of the Generation of ‘14, which was also

very closely

associated with public administration. This can be observed in the significant reversal

-practically

symmetrical- in the number of owners and high-ranking civil servants, which shows an important

generational

shift in the way that elites were recruited: the Generation of ‘14 stood out for reverting the

inherited

financial and social capital in a determined cultural stake, thus modifying the conditions for

the symbolic

validation of economic capital. This lateral generational mobility of the elites, oriented

towards public

administration -especially towards educational and cultural institutions- is the biggest

difference between the

Generation of ‘14 and the symbolic revolution analysed by Bourdieu in Manet. The alliance

between the

revolutionary academic section and the intellectual bohemians can be clearly observed in the

trajectory depicted

in the three charts.

In terms of social background, we can see an important presence of economic

capital (owners

and a part of the petite bourgeoisie) and the cultural capital most closely linked to it

and to politics

(legal professions), although there is also a relevant link with administration, illustrated by

the 21

signatories’ fathers who were mid-level civil servants. In this regard, it is important to note

that the

symbolic revolution does not come out of the blue, it is not an absolute novelty: it recovers

potentialities

that are present in the field and rewrites them, also at the family habitus level. In

1913, the lesser

importance of the categories that we highlighted in the social background is confirmed, with the

logical

exception of mid-level civil servants. However, we also observe an important increase in those

categories

associated with intellectual bohemians (journalists, writers and artists) and academia

(professors and students,

but also a majority of mid-level civil servants linked to educational and cultural

institutions). The early

academic consecration that is shown in this second chart is accompanied in the social destiny

chart (Second

Spanish Republic, 1931-36) by an outstanding increase in high-ranking and mid-level civil

servants, as well as a

moderate growth in professors and teachers (already present in 1913). This occurred at the

expense of a part of

the intellectual bohemians who found a more stable social position, though not necessarily a

more prestigious

one, in public administration: the symbolic revolution, in this case, created an institutional

space for the

revolutionaries within the state apparatus.

The possibility of a symbolic revolution driven and sustained from academia is

therefore

demonstrated, having always in mind that, as we said before, this academia was very distant from

the one

described by Bourdieu for art in the Second French Empire. In the Spanish case, the previous

generation had

managed to introduce relevant changes in the recruitment of professors and in the access to the

civil service,

paving the way for the symbolic revolution of those who succeeded them. But what about the two

missing

requirements that, according to Bourdieu, accompany cultural capital in the symbolic

revolutionary? Does the

academic support of the Generation of ‘14 mean that social and economic capital were not as

decisive to sustain

“creative autonomy” against scholasticism?

In this aspect, the Spanish case seems to partially support Bourdieu’s claims,

although

there are two significant differences: 1. The collective and impersonal support that an academic

institution

guarantees is not exactly equivalent to the economic and social capital that a single individual

can accumulate,

even if we find a socially elitist selection in the access to the academia. 2. The fact of a

symbolic revolution

from inside the academia opens new theoretical possibilities to think this process in different

empirical

contexts and, above all, to analyze the logic of the field resulting from the symbolic

revolution. Both

differences have important sociological and philosophical implications, as discussed in the

conclusion.

About the social and economic capital, the charts do not disclose any

information beyond the

evident social selection that shows the social background of the signatories. Only 16.67%

belonged to the

category “Popular classes and petite bourgeoisie”, a markedly low percentage compared

with the

quantitative representation of this category in the Spanish society of the time. However, the

internal dynamics

of the Generation of ‘14, studied from a qualitative analysis of trajectories and variables

relative to the

political evolution of the subjects provide us with more information, at least in regard to

these three points:

-

In a society that was profoundly shaped by class differences, the

lack of economic

capital tended to result in children who had to work and contribute to sustaining

the family economy being

expelled very early from the scholar institution. In the rare cases in which such an

exclusion was late

compensated (for instance, with the support of workers’ unions and parties) there

was always a mark of

cultural illegitimacy -both subjective and objective- that pushed these subjects to

the margins of the

intellectual field (Costa Delgado, 2019, pp. 263-310). This huge

gap that separated the

instances of bourgeois legitimacy from those which were specifically for workers

also led to important

disagreements inside the “coalition” that set in motion the symbolic revolution:

there were several

rapprochements between academics and intellectual bohemians, on the one side, and

republican and labor

parties with a broad grassroots base, on the other hand; but with the exception of

some particular cases,

they were always collectively ephemeral, partly because of the little interest of

the latter in playing

the academic-intellectual game of the former.

-

Once this access limitation had been overcome, the distance from

necessity and the

urgencies of practical life tended to distribute subjects among different places

within the intellectual

field. As we have seen before, Bourdieu identifies this aspect as one of the social

foundations of

scholasticism and, undoubtedly, it is present in fundamental intragenerational

oppositions, such as the

one that confronts university professors and journalists, which becomes evident in

different exchanges and

moments of the generational trajectory and granted the latter a lower status due to

their dependence on

short-term production. Also, that scholastic dimension is revealed in many of the

signatories' perception

of what meant to be an intellectual and in their political projects. However, the

previous social

selection process (which did not make this group as univocally dependent on academia

as the intellectuals

from humble backgrounds that the Church tended to recruit), as well as the fact that

the academia of the

time included forms of recruitment and promotion partly adjusted to the patterns of

the new symbolic

revolution

5

, resulted in the academic sector of the Generation of ‘14 not being prone to

maintaining the

pre-existent academic orthodoxy. The uniqueness of the Generation of ‘14 lies in the

fact that its

processes of “creative autonomy” responded to similar principles to the ones that

drove the new academic

norm, in a wider context of reformation of the cultural institutions of the State:

this norm was, so to

speak, circumstantially functional to the symbolic revolution. Thus, this generation

can be characterized

by a scholasticism in the way of understanding the intellectual’s social place

(something that is

inevitably linked to their social and economic background, by the way), but this was

compatible with a

non-scholastic intellectual praxis promoted by academia itself. Adhering to this new

praxis was easier

from an academia that stimulated it and tended to be harder when one got away from

it and was put under

other pressures, such as the need to stick to current political affairs or the

urgency of presenting

poorly written texts for economic reasons.

-

There is a third form of exclusion that reveals itself in a very

subtle way. The

accumulation of social capital required knowing how to behave in social spaces where

a brutal classism

operated and was made evident through details, through little interactions that

selectively motivated or

discouraged the subjects who participated in them with different properties and

social resources

profoundly rooted in their habitus. Modifying the deep layers of the

habitus is an

extraordinarily difficult endeavor, which reactivates forms of exclusion homologous

to the ones described

in the first point, but not exactly the same. As demonstrated by the comparison

between the trajectories

of Tomás Álvarez Angulo and Francisco Núñez Moreno (Costa Delgado,

2019, pp. 263-310 ),

it was easier to integrate oneself into the intellectual elites that made up the

Generation of ‘14 if you

were a laborer without formal education from the center of Madrid than if you were

the son of a

cacique from a small village in Andalusia with a brilliant academic track

record: in this case, the

uneven social distance from the informal rituals required in the center of the

kingdom’s intellectual and

political life was a determining factor in order to stimulate or discourage the

integration into the

social networks that also sustained the Generation of ‘14, both within the academia

and outside of it.

In sum, academia allowed the Generation of ‘14 to have institutional support

for its

symbolic revolution, but it did not eradicate the weight of social and economic capital, as they

continued to be

an implicit part in the social recruitment of the intellectual and political elites that made up

the group. This

is different from Manet’s case, since managing a career and a creative process that are

sustained by

institutional networks does not respond to the same determinants as managing a career while

being exclusively

dependent on one’s family rent and a network of symbolically prestigious contacts. But the

institution, at least

in our Spanish case, did not remove the weight of these two factors in the possibility of

participating in a

symbolic revolution.

![]()

![]()