INTRODUCTION

A distinctive role of family care defines the Southern European welfare

models. Several

studies have highlighted the functional overload for families with children under three years

old, in which

unpaid work is mainly provided by women (even when they work full time), in a context in which

the public and

private childcare provision is insufficient to meet families' needs. In addition, the impact of

the so-called

new social risks (Taylor-Gooby, 2004; Bonoli, 2007)

has hit these

societies particularly hard because of the characteristics of their welfare models (Marí-Klose

& Moreno-Fuentes, 2013), which also expose the middle classes to difficulties in

ensuring economic

security (Ranci et al., 2021). In this context, the COVID-19 pandemic in

southern Europe

magnified existing inequalities in care, exacerbating the gendered differences in the provision

of unpaid work

within families. For mothers with young children, the school and nursery closures due to the

first lockdown

implied a further effort in care, usually compensated with leaves or a reduction in working

hours (Maestripieri, 2021).

A few years ago, demand for 0-3 childcare in Barcelona began to be partially

covered by the

emergence of grassroots initiatives that created communities of care made up of parents and

educators.

Communities of care are informal communities made of parents and educators that gather around

socially

innovative projects of early childhood education and care; parents and educators are involved

personally in the

functioning of these initiatives, which propose educational projects based on free education.

These projects,

working at the boundaries between the loving environment offered by families and the

institutionalised care

provided by nurseries, are particularly valued by both the participating families and the public

institutions

for their capacity to propose alternative solutions to the market and the public sector and to

act as agents

that promote alternative pedagogies —e.g., Montessori, Waldorf, and Pikler—. In addition, they

offer an

environment open to the participation of parents in the care of their young children, reducing

the distance

between care in the home and caring institutions thanks to the capacity of care offered by the

communities that

sustain these projects, made up of both parents and educators.

This article aims to investigate to what extent participation in social

innovation was a

resource used by families during the first COVID-19 outbreak in March-June 2020 in Barcelona

when nurseries and

schools closed. We argue that social innovation could constitute a valuable resource, offering

community support

in times of need to working mothers when lockdown suddenly deprived them of the help of their

primary networks

(because of social distancing) and public services (because of school closures). At the same

time, however, the

economic precariousness suffered by these projects and the lack of institutional acknowledgement

have exposed

these projects to the harshest consequences of the pandemic, putting their survival seriously at

risk. But the

same community worked to help them survive, thanks to solidarity mechanisms established between

families and

educators. The research questions addressed in this study are the following: what were the

consequences of

COVID-19 on the work-life balance of the mothers who participated in social innovation? What was

the impact of

the school lockdown on socially innovative projects? Could the communities of care established

around socially

innovative projects constitute a resource to cope with the social isolation and economic turmoil

caused by the

pandemic?

Stemming from the Primera Infància research project (2018-2021), this article

presents a

follow-up investigation on the social innovation projects and their families: it analyses what

happened between

March and June 2020 when schools were closed in Barcelona.

1

It considers three types of projects that we define as socially innovative because of their

community

organisation, because they stem from citizen initiatives, and because they apply free-education

pedagogical

principles. These projects are llars de criança (childminders), espais de criança

(free-education

nurseries) and grups de criança (community care groups) (see section 4 for further

explanation). This

article applies a mixed-method approach and uses different qualitative and quantitative data

collected between

June 2020 and May 2021. It analyses qualitative interviews with mothers (June 2020),

representatives from the

associations that bring together these projects (June 2021), online structured interviews with

educators working

in these projects (June 2020), and a live survey conducted with mothers of children from 0 to 3

years old in

Barcelona (July-October 2020). Results demonstrate the resilience of these projects and the

support given by the

community around them during the worst phase of the pandemic in Spain.

The article is structured as follows. The next section presents the main

characteristics of

the southern European welfare model in terms of the gendered distribution of paid and unpaid

work. We also

review the main consequences of the COVID-19 crisis on gender equality in southern Europe.

Section 3 presents

the mixed-method approach applied, while the subsequent sections show the main results, focusing

respectively on

the pre-COVID-19 childcare situation in Barcelona (§ 4), the consequences of COVID-19 on

families (§ 5), and its

repercussions on socially innovative childcare projects (§ 6). The last section discusses the

empirical evidence

in light of the debate on the southern European welfare model and draws the preliminary

conclusions on the role

that social innovation can play as a resilience agent.

THE SOUTHERN EUROPEAN MODEL AND ITS RESILIENCE IN THE FACE OF THE COVID-19

PANDEMIC

The development of southern European countries’ welfare regimes (SEC)

-namely, those in

Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain- was inextricably linked to transitions to democracy

starting in the 1970s and

Europe-led welfare policy diffusion processes. In contrast to other European welfare states,

the SEC models

emerged and consolidated over the 1980s in a context of profound, ongoing structural changes

that have led to

welfare state retrenchment and recalibration from the 1990s to the present day (Gallego et

al., 2005, Gallego & Subirats, 2011, 2012).

The initial characterisation of the SEC welfare model in the mid-1990s

presented an

analytical challenge to the mainstream theory of Esping-Andersen (1990),

who included SECs in

the conservative cluster because of their work-based protections. However, authors such as

Ferrera (1996) contested this categorization. According to him, the

welfare states of SECs

included features similar to the conservative model of social protection and employment,

although less advanced.

They were defined by relatively high unemployment rates and relatively low female

participation in the labour

market, and a clear insider/outsider division based on their relationship with an employment

regime that

developed slowly but eventually became rigid and highly protective. While work-related

income maintenance

schemes are at the core of public welfare, non-contributory programmes and services for

beneficiaries such as

orphans, widows, or the disabled are weak and poorly coordinated.

In fact, SEC social protection system foresees a labour policy approach

that protects the

work of the male breadwinner as much as possible, to the detriment of more marginal groups

in the labour market.

This model of social policy considers women as the main ones responsible for the unpaid work

within families. In

contrast, women’s labour market participation is regarded as an additional (and thus

expendable) income to the

main income of their male partner (Vesan, 2015). In this context,

economic slowdowns and

labour deregulation reforms have had a particularly negative impact on layers of the

population with weak

connections to the labour market - temporary contracts, seasonal employment, freelance work,

and work in the

underground economy. All these situations are suffered more frequently by women than by men

(Marí-Klose & Moreno-Fuentes 2013).

Thus, this welfare model is marked by its low levels of social spending

-corresponding to

late industrialisation and modernisation- and by the relevance of the traditional family

model, based on the

figure of the male breadwinner and the gender roles that this entails (Castles, 1995; Esping-Andersen, 1999). Some studies

highlight the importance of religion and culture in

explaining the survival of traditional family values (Castles, 1994; Van

Kersbergen & Manow, 2009). Despite the emphasis placed on the role of the

family, social policies do

not reinforce the family's capacity as a provider of well-being in the absence of

institutional help. The

familialist scheme has continued to compensate for the weakness and fragmentation of social

assistance and

social care policies and the social exclusion derived from the lack of policies to support

young people leaving

the parental home, care for dependents or the transformations of the labour market.

Given this context, the emergence and impact of new social risks

(NSR) have been

particularly disruptive in southern European societies. NSR refer to difficult situations

people may face due to

the transition to a post-industrial society (Bonoli, 2007). They include

inadequate welfare

protection stemming from labour market precarity in numerous situations: low-paid work

either for unskilled or

over-qualified workers; long-term unemployment because of obsolete skills; unstable jobs or

careers; elderly or

child dependents; difficulties in making paid and unpaid family work compatible, etc.

Although some policy

schemes to combat NSR follow EU regulations, they differ considerably across southern

European welfare regimes

and regions with devolved powers, which have each developed different welfare regimes since

the 1980s (Gallego et al., 2003). Leftist governments and expansive

economic periods lead to a higher

investment in policies that supports citizens against NSRs, but, especially in SEC

countries, these types of

policies remain unstable, intermittent, and often reversible (Bonoli,

2005). NSR have placed

the family "pillar" of the Mediterranean welfare model under unsustainable stress and

pressure: the family can

no longer perform its traditional "shock absorber" role. Middle-class households have been

increasingly exposed

to financial insecurity and vulnerability in southern Europe, putting into question the

capacity of the welfare

model in this area to protect against risks (Ranci et al., 2021).

Studies have shown

how citizens have been forced to resort to new care strategies outside the traditional

family provider model (Caïs & Folguera, 2013).

Further analyses point at profound transformations since the 2000s in

these countries,

prompted by several factors shaking up the SEC welfare model. First, European integration

and the 2008 global

crisis forced fiscal austerity and cost-containment policies, together with the retrenchment

and calibration of

income-maintenance and service provision policies to counteract population ageing. Second,

the sharp transition

to a post-industrial society, with a service-based economy and family and gender relations

much closer to the

neighbouring northern European countries, has sparked unprecedented challenges for SEC

welfare regimes (Marí-Klose & Moreno-Fuentes 2013). The rise of

female employment, on the one hand, and the

expansion of job precariousness, on the other hand, have accentuated the impact of the

institutional weaknesses

of the southern welfare model. In fact, in recent years, thanks to the promotion of European

cohesion policies,

investment in early childhood policies has also grown in southern European countries and is

considered key for

obtaining more female participation in the labour market (Guillén & León,

2011).

Nevertheless, women are still those mainly responsible for unpaid work. Quite frequently,

the birth of a child

implies that women leave the labour market or permanently reduce their working hours (Maestripieri, 2015).

There is no doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic has put further stress on the

social protection

weaknesses of the southern European welfare regimes. The closure of essential services, the

2020 spring

lockdown, and job losses or furloughs deepened traditional class and gender inequality

cleavages and exacerbated

the insider/outsider divide. They also strongly highlighted the debate over NSR. The

pandemic exposed just how

much the economic security of the middle class has been at risk over the last decades (Ranci et

al., 2021; Bertogg & Koos, 2021). The outbreak increased the

need for care provision

suddenly and unprecedentedly, both inside and outside the home (Craig,

2020). Since women

have traditionally assumed a disproportionately high share of this unpaid work, projections

pointed to the risk

that they would take on most of these increased responsibilities. Empirical evidence shows

that consequences

were particularly severe for vulnerable groups, such as single-parent families or those at

risk of social

exclusion. Women with caregiving responsibilities saw their well-being and career prospects

greatly affected (Blaskó et al., 2020; Maestripieri,

2021). The most recent research on the

impact of the lockdown on gendered roles shows that inequalities persisted in temporal and

spatial workplace

constraints (Craig, 2020). The present pattern of job losses and

furloughing from the

pandemic appears to be gender-neutral (Hupkau & Petrongolo, 2020).

However, women have

suffered more significant pressure than men to reduce their working hours or stop working

temporarily, causing

an increase in the paid working hours gender gap (Collins et al., 2020;

Craig &

Churchill, 2020; Dias et al., 2020).

The gendered effects of the pandemic are stronger in institutional

contexts - such as

southern European countries - where the proportion of the population exposed to the new

social risks is higher,

and there is a weaker institutional environment (Maestripieri, 2021). In

the case of Spain,

the spring 2020 lockdown was one of the strictest in Europe. It substantially impacted the

labour market,

causing many job losses, especially in non-essential sectors where teleworking was not an

option. Job losses

mainly regarded temporary jobs and struck low-skilled workers. The probability of losing a

job was slightly

higher for women than for men. The increased need for childcare and housework derived from

lockdown, school

closures and the impossibility of outsourcing was taken on mainly by women. In this context,

the government did

not put forward any emergency benefits to help families face the widespread school lockdown

(Koslowski et al., 2020). Consequently, the burden of parental care

mainly was taken on by

women. The pandemic, therefore, increased gender inequality in both paid and unpaid work (Farré

et al., 2020). However, men slightly increased their participation in these tasks.

Some studies have

detected changes in the distribution of household and caring tasks compared with the

pre-pandemic situation (Sevilla and Smith, 2020). These changes vary from

country to country, but also according to

existing axes of inequality - gender, educational and socio-economic levels, ethnicity - and

other emerging

ones, such as the mothers' or fathers' possibility of teleworking or not.

Most research up to now has focused on the difficulties of the state, the

market and the

family spheres to provide their share of welfare responsibilities since the onset of the

pandemic. However, a

fourth sphere or pillar also contributes to the configuration of a welfare regime, with

responsibilities and

functions regarding individual and collective well-being: the community formed by social and

associative

networks in local contexts (Gallego et al., 2003, 2005; Gallego & Subirats, 2011, 2012). This community sphere includes a

diverse and complex configuration of civil society initiatives of variable degrees of

formalisation, from ad hoc

neighbourhood networks to well-established non-governmental organisations. These

experiences, sometimes called

non-profits or third sector, emphasise that they do not belong either to the public or the

market sectors.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, and particularly during the lockdown periods, some social

groups heavily depended

on the actions of both informal and formal community networks. This study will focus on

socially innovative

projects in early childhood education and care in the city of Barcelona during the pandemic.

METHODS

The empirical evidence stems from the Primera Infància research project

(2018-2021),

financed by the private RecerCaixa foundation. The project's scope was to investigate to

what extent the choice

of a particular model of 0-3 care influences mothers' participation in the labour market,

partly focusing on the

socially innovative projects based on collaborative practices between parents and educators.

Specifically, the

research objects in this article are the mothers involved in socially innovative early

childhood education and

care projects. We investigated the constraints mothers must face when making employment

decisions; therefore,

the study does not involve fathers. The project uses a mixed-method design, in which the

qualitative data

collection preceded and informed the quantitative data collection. The questions proposed in

the survey were

developed out of the analysis previously done on the qualitative interviews, constituting a

sequential and

equivalent mixed-method design as defined by Leech (2009).

The complexity of social innovation poses a challenge to the

operationalisation of this

concept in our research on early childhood education and care. We selected projects that

respected the following

criteria for this research work: initiatives that i. were led by citizens; ii. foster

cooperative and horizontal

relationships among the participants; iii. generate alternatives to childcare services

offered by public

institutions or the market, following the definitions of social innovation previously

mentioned (Blanco & León, 2017). Under these conditions, we identified

three types of projects:

childminders (llars de criança or mares de dia), care groups (grups de

criança), and

free-education nurseries (espais de criança) (see the next section for more details

on the projects

involved).

The COVID-19 pandemic broke out during the data collection phase, notably

after the

semi-structured interviews with mothers and educators of the socially innovative projects

and before the survey

with mothers of children under three in Barcelona, scheduled for April-June 2020. The

outbreak of the pandemic

disrupted our planned schedule. Still, at the same time, it offered us the opportunity to

investigate lively

what the consequences of closing schools were on social innovation in 0-3 childcare. To

gather empirical

evidence on the impacts of the first lockdown, in June 2020 we contacted again the 15

educators and 18 mothers

we had interviewed before the pandemic (May 2019-January 2020). Of the 15 educators, we

collected ten structured

interviews through a Microsoft Forms questionnaire, one WhatsApp voice message and one

telephonic follow-up

(reaching 12/15 of the pre-Covid interviewees). These sources allowed us to collect

information regarding the

economic impact of the pandemic on the projects and the strategies that educators put in

place to cope with the

worst consequences of the spring 2020 lockdown. Of the 18 mothers, we collected one

follow-up by Skype and nine

follow-ups by WhatsApp voice message. Two more mothers answered by email (reaching 12/18 of

the pre-Covid

interviewees). In the case of the mothers, the main interest of the follow-up regarded the

strategies they put

in place to cope with the closure of the childcare services, including the distribution of

unpaid work with

their partners and their commitment to paid work during the months in which schools were

closed. Mothers could

not rely on primary networks nor on private childcare help because of social distancing

measures (March-June

2020). In May 2021, at the end of the first year of living with the pandemic, we conducted

three interviews with

representatives from the main associations of socially innovative projects in Barcelona to

complete the picture

of what had happened over the previous school year. Interviews and voice messages have been

transcribed verbatim

and analysed with Atlas-ti, except for one educator who refused recording during the

telephonic follow-up. We

coded qualitative materials for detailed content analysis, and the following sections will

present selected

extracts to sustain the results of our analysis empirically.

Regarding the quantitative data, we organised an online live survey which

was open for

answers from June 2020 to November 2020. We collected 520 responses from mothers with

children born between 2016

and 2019 residing in Barcelona at the moment of the survey. The questionnaire collected

information related to

each mother's career and childcare choices. Although it was not a longitudinal survey, the

questionnaire

structure included retrospective questions that allowed us to reconstruct information on

work and childcare from

the child's birth up to the present. It also reported information on the partner's job (if

present), the

socio-economic condition of the household, and attitudes towards social innovation.

Given that we conducted the live survey after the first COVID-19 lockdown,

we also could ask

what impact COVID-19 was having on the households' economic security and mothers' work. That

said, we did not

design the survey to be representative of mothers with children under three in Barcelona,

since there was no

random sampling conducted for participating in the survey. We circulated the survey

primarily via schools,

social networks (Facebook and Twitter), and the primary networks of the researchers. To

collect as many social

innovation cases as possible, we asked the previously interviewed mothers and educators to

circulate the survey

within the analysed projects. We also asked the main associations of social innovation

projects to distribute it

among their members. In September-October 2020, to recalibrate the sample to better cover

families from lower

socio-economic backgrounds and who had been under-represented in the first wave of data

collection (June-July

2020), we performed 75 phone surveys using contacts that primary schools gave us. Data

includes 89 participants

that had participated - at least occasionally - in a socially innovative project. Survey

data have been

primarily analysed at a descriptive level and compared with the findings emerging from the

analysis of the

content of the previously mentioned interviews.

The empirical material collected was analysed by using a mixed-method

approach. We

integrated the qualitative and quantitative data from different sources to comprehensively

understand the

empirical case under investigation (Bryman, 2009). The extracts we

collected from the various

types of follow-up interviews were analysed under a content analysis and compared with the

information emerging

from the survey. Many of the interviewed mothers also answered our survey. This fact

facilitated the integration

of data from different sources in a nested design (Small, 2011); however,

we could not match

qualitative and quantitative responses as the answers in the survey were fully anonymous.

Part of the content of

the structured interviews was categorised and analysed quantitatively. Given the reduced

numbers we had in our

samples, we do not have the ambition of reaching a statistical representativity.

We rely on different data to answer the research questions we presented in

the introduction:

we used the empirical material collected from mothers involved in the projects (including

interviews, WhatsApp,

email and the survey) to analyse the consequences of COVID-19 on the work-life balance of

the mothers who

participated in social innovation; we used the empirical material collected with the

educators working in the

projects (the structured interviews, WhatsApp message, the phone interviews and the

semi-structured interviews

with the three key informants) to investigate the impact of the school lockdown on socially

innovative projects.

We used the joint analysis of the two corpora of empirical materials to analyse the role of

the communities of

care (composed of the mothers and the educators who participate in the social innovation

projects). All

materials thus concurred to answer our third research question: could the communities of

care established around

socially innovative projects constitute a resource to cope with the social isolation and

economic turmoil caused

by the pandemic?

The following findings section was organised by focusing on two different

units of analysis:

the mothers of children who attended socially innovative projects (section 5) and the

socially innovative

projects themselves (section 6). Section 4 presents the three cases that we studied in our

project.

SOCIALLY INNOVATIVE 0-3 CARE IN PRE-COVID-19 BARCELONA

Over the last two decades, Barcelona has experienced a robust growth in

the

institutionalised 0-3 childcare services. The "escola bressol" model (EBM) is solid and

based on the

construction of municipal public nurseries, which have consolidated their reputation for

offering high-quality

services over the years. Currently, there are 102 EBMs distributed evenly around the city,

with a capacity to

school 8,500 children. Despite their growth, there are only enough public places (around

14,000) to serve a

fraction of those who apply for the service; these places serve about the 21% of the

children under three who

are residents in the city (38,377 children in 2020), while around 24% attend private

nurseries. However, in its

latest strategic plan for early childhood education and care (dated April 2021), the

municipality itself

recognises that an institutionalised care model can only partially cover the increasing

multiculturality and

diversity of the families applying for the service and its growing differentiation of needs

(Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2021).

Socially innovative projects have stemmed from citizens' initiatives to

cope with these

increasingly diverse needs. On the one side, families and educators were unsatisfied with

public and private

institutionalised services' high ratios (one educator per every 8 children under one year

old, one educator per

every 13 children under two, and one educator per every 20 children under three; art. 12.1,

DECRET 282/2006,

Generalitat de Catalunya). On the other side, social innovators criticised the

institutionalisation of such

young children. They wished to create an environment more akin to being cared for in the

home (llars de

criança) or playgroups (espais/grups de criança).

"The attention given in traditional nurseries is not the

same quality as in

care groups. Already assuming that the ratio is much lower. In traditional

kindergartens, the ratio for a

class of under-ones is 12 children per adult. And there's a second adult that rotates

between several classes.

But, during the day, there are 12 or 13 children who are alone with one person. One

person on their own will

not attend to their needs in the same way, emotionally and practically, and manage the

children's conflicts as

to when there's an adult per 4 or 5 children. So, in the care groups, the ratio is very

low, 4 or 5 children

per adult." [Mother, free-education nursery]

"And so, what kind of differences are there...? Well,

what we talked about a

little earlier about it not being an institution but a home. And that's the difference

for families and for

the children. When things change, they're tiny, right? Going from their mothers into the

world should be taken

little by little. Maybe they've been with a babysitter or their grandmothers for one

day. So before arriving

at a kindergarten with 25 children, an educator and a structure, an institution, so,

they come through here,

it's a familiar world where there's free play, and where someone other than your mother

or father takes care

of them, in another environment, with other children. They still need to adapt, and,

here too, we adapt things

slowly, it's different. I believe that for babies so young, this step is huge. So, going

straight from your

mother's house to the kindergarten, well, I think that's a huge shock." [Educator,

childminder]

Three main types of projects emerged as alternatives to the EBMs and the

private nurseries.

Although different in their functioning, the projects we have included all have things in

common: small ratios

(three to five children per adult), small groups (maximum 20 children) and a community

organisation with the

parents' direct involvement in their everyday functioning. The first model studied in this

article is the

llars de criança or mares de dia, in which an educator (or two) opens their

houses to welcome the

youngest children in a home-like environment. Although public institutions have not formally

recognised them as

an alternative 0-3 care service, they have established an association (Llars de Criança, in

2010) and a

cooperative (Cooperativa de Mares de Dia, in 2017), which constitute a point of reference

for educators,

offering training and counselling. The projects are usually relatively small since the

maximum ratio per

educator is three to four children, and one or two educators typically manage them. In this

model, the educators

run the pedagogical project, while community involvement is limited to food preparation and

social activities

with other families.

The other two types of projects (espais and grups de

criança) have a more

substantial communitarian nature. They are bigger (around 15-20 children) and involve

slighter older children

(one to six years old). In these cases, parents and educators collaborate in the project's

management and the

definition of its goals, usually renting a private space or, less frequently, occupying an

abandoned building or

being assigned a space by the municipality. Families share running costs, and the management

is self-organised

through assemblies, where participants contribute according to their abilities. The main

difference between

these two projects regards educational projects: in the case of espais, the educators

take the lead and

decide how to organise learning activities with the children; in the case of grups,

parents take the lead

and usually participate directly in the care by supporting one or two educators, hired by

the association, in

their work. Both types of projects have Xell as their reference association. This

association was founded

in 2003, and promotes free-education practices, supports home-schooling and offers training

and counselling to

projects and families. However, there is no specific requirement in formal education to

participate in these

projects: many educators joined the free-education movement when they became parents and

ended up running a

project after their children grew up and started primary school. As in the case of llars

de criança,

public institutions do not formally acknowledge these projects as alternative services for

the care of the

under-threes. But, unlike the llars de criança, their association is not eager to

receive formal

acknowledgement of their educational activities, since regulation could impede the freedom

of education and

management that characterise these projects.

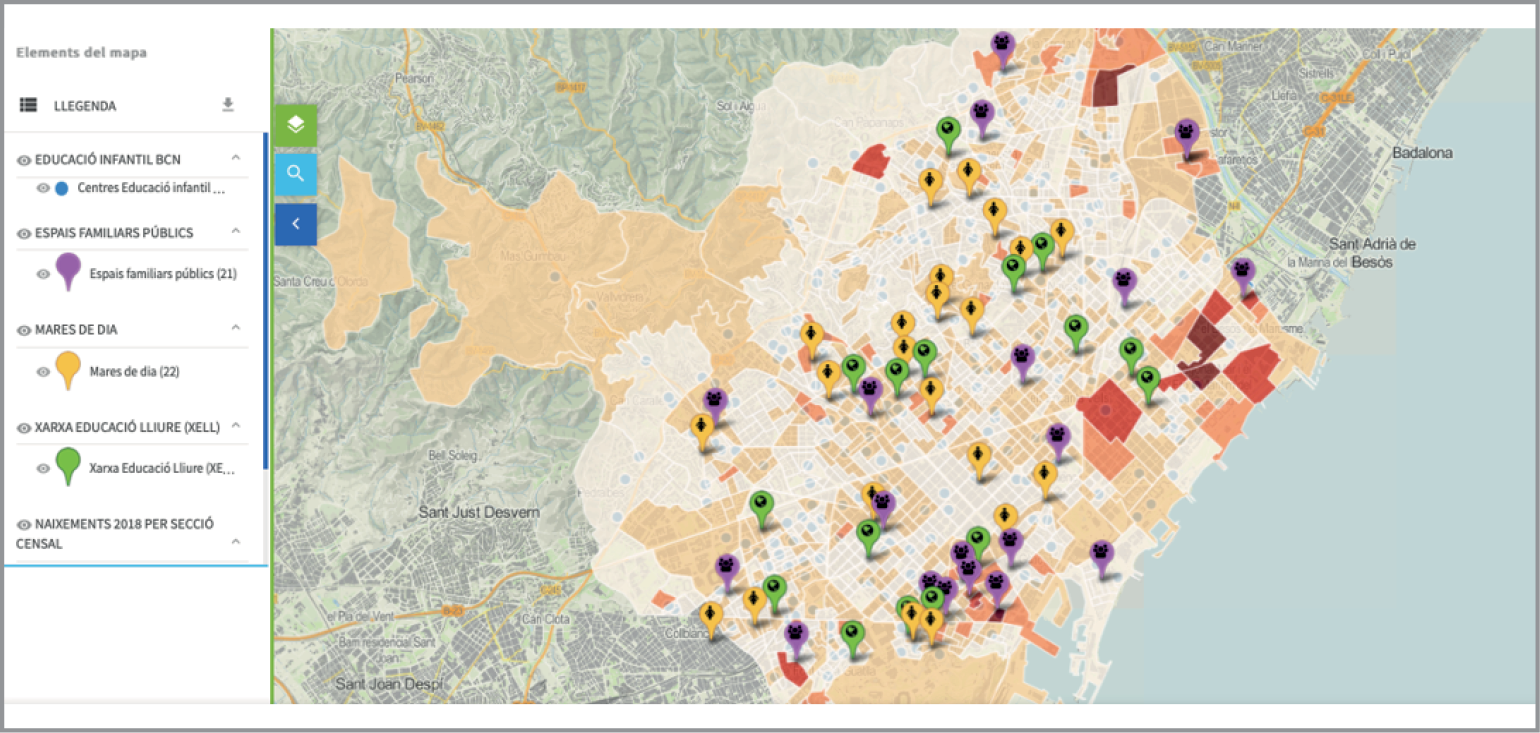

In 2021, there are 29 llars de criança and 19 espais and

grups de criança

in total in Barcelona. Given the reduced ratios that characterise these projects and the

consequent higher

costs, it is not surprising that only a few hundred children across the city can access

these types of childcare

services. Furthermore, they are not evenly distributed across the city. Still, they tend to

concentrate in

currently gentrifying and affluent neighbourhoods such as Gràcia or Poble-Sec, areas where

professionals tend to

live and where a lively civil society favours the emergence of citizen-led initiatives (Cruz

et al., 2017).

In the survey conducted within the project, about 17.1% of our sample

(corresponding to 89

cases) was involved at least once in a social innovation project. Only around 6% of the

sample used social

innovation regularly in each of the three age spans we analysed in our survey (see Table 1).

About 77% of the sample heard of such projects, but only 21.7% of people who were never

involved in the social

innovation would like to try these services.

Self-selection thus characterises the families that participate: they

usually belong to the

most socially active and well-off strata of the intellectual middle-class, as shown in Table

2. Socially innovative projects tend to be chosen more often by professionals,

high-level public sector

staff and the self-employed. Still, manual workers rarely choose this option - at least in

our survey. Most

manual workers do not even know these social innovation projects exist, confirming previous

results that point

to social innovation as mainly a middle-class phenomenon (Cruz et al.,

2017; Maestripieri, 2017). In our survey, 38 of the 89 cases with

contacts with the innovative

projects did not apply for the EBMs. This finding confirms that social innovation is not

exclusively a

second-best choice for those families who do not enter the public system, but an explicit

preference for those

against the institutionalisation of their children.

Table 1. The use of socially innovative care

|

Type of care

|

Between 4 and 12 months |

Between 12 and 24 months |

Between 24 and 36 months |

|

Family care (mother/partner) |

45% |

21.9% |

27.5% |

|

Other relatives/friends |

11.6% |

9.5% |

10.4% |

|

Social innovation (including llars de criança, grups de criança &

espais de criança) |

5.8% |

7.3% |

6.5% |

|

Public nurseries |

18.3% |

34% |

28.3% |

|

Private care (including childminders) |

19.4% |

27.3% |

27.3% |

|

Absolute values |

520 |

465 |

385 |

Table 2. The use of socially innovative care by the occupational position of

the

mother

|

Type of care

|

Experience of SI |

Would use it |

Would not use it |

Do not know SI |

|

Professional |

15.1% |

30.3% |

38.6% |

15.9% |

|

High-level public sector staff |

14.6% |

22.9% |

46.9% |

15.6% |

|

Self-employed worker |

15% |

20% |

25% |

40% |

|

Manual work |

12% |

16% |

32% |

40% |

|

Out of work mother |

19.3% |

16.7% |

38.9% |

25.2% |

|

Absolute values |

89 |

113 |

203 |

115 |

A second important element to consider is the lack of institutional

acknowledgement. This

situation makes it impossible to receive funding from public institutions for the projects'

running costs,

causing a certain economic precariousness that endangered the survival of these projects

even before the

pandemic. The precariousness is only partially compensated for by funding received by the

projects for specific

ventures. This situation does not guarantee long-term financial sustainability for projects

which depend

entirely on the fees paid by the participants.

"The current financial aid for public nurseries is for

regulated schools.

Eh... or the private nurseries that are approved by the education department. A

free-education nursery is

not... it's an association... it's something else. And you can't get help to pay for it,

no. Economically it's

very tough." [Mother, free-education nursery]

"I don't know, it's work, sometimes I work till late,

you need to. And my

colleagues... they too have extra jobs to pay the bills. So I think it's a little

precarious or quite

precarious. And that, if there were a public will to finance this type of education,

with less money than gets

allocated to a public school, we could provide an education with a better ratio and with

lots of innovation.

So it's disappointing." [Educator, community care group]

The situation before the pandemic had already revealed severe

vulnerabilities in the

projects. The small number of children involved in the projects and the educators' working

conditions led to

extreme precariousness. The financial sustainability of the projects is precarious since

they need to find a

delicate equilibrium between very high fixed costs (determined by the private rental market

in a city like

Barcelona) and the need to go beyond a pure non-profit activity for those educators

involved. The results are

fees comparable to private nurseries but, in any case, are pretty expensive for those

families that can access

public nurseries at lower sliding-scale prices. Although they constitute interesting

experiments in terms of

community practices and pedagogical innovations, an unavoidable elitism marks these socially

innovative 0-3

childcare projects. This elitism stems from a lack of public funding since public

institutions cannot support

financially projects that are not recognised as childcare services by the regulation. The

main consequence is

that part of the population is excluded for economic reasons, and these projects are not

recognised as

alternatives to EBM among working-class families (as shown in Table 2).

The financial shock

caused by the 2020 lockdown drastically affected these projects and magnified a situation of

precariousness that

was already in place, as we will see in the following section.

THE IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON FAMILIES

The COVID-19 outbreak generated various needs among social groups that are

usually not

included as needing public and community support (Bertogg & Koos,

2021). If we focus on

families with small children, the closure of nurseries and the need to maintain social

bubbles to protect older

people meant that parents were suddenly left alone to navigate the challenges of juggling

work and family within

their homes (Maestripieri, 2021).

Nevertheless, the mothers who participate in these projects usually belong

to the educated

middle class. Consistent with the literature on the social consequences of COVID-19 (Maestripieri, 2021), they have coped better with the consequences of the

pandemic. As shown in

Table 3, the mothers involved in social innovation projects are usually

medium- and

high-skilled. The majority of mothers participating in social innovation are employed

part-time since

participating in these projects requires the constant involvement of parents, a requirement

usually covered by

the mothers (64% of cases), confirming that even in these families, care is still highly

gendered. If we focus

on the consequences of the pandemic on the economic insecurity of their households, however,

families that opted

for socially innovative projects demonstrated resilience to the COVID-19 crisis. They are

the only category that

showed an increase in economic security after the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak (from 84%

to 88% of households

received unexpected aid of 700 euros monthly). The vast majority of them also do not have

experience in late

payment of utility bills, with only 8% of families first experiencing this after COVID-19

compared to 15% of

those who opt for family care, other relatives or public care.

Table 3. Type of care by socio-economic conditions

|

|

Family care |

Other relatives |

SI. |

Public care |

Private care |

|

Education

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Low skilled |

40.6% |

12.5% |

3.1% |

40.6% |

3.1% |

|

Medium skilled |

41.5% |

12.2% |

6.1% |

24.4% |

15.8% |

|

High skilled |

29.3% |

11.8% |

4.7% |

26.6% |

27.6% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Working activity

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inactive |

67.4% |

6.3% |

1% |

16.8% |

8.4% |

|

Part-Time worker |

34.8% |

9.1% |

9.1% |

25% |

21.9% |

|

Full-Time worker |

18% |

15.7% |

3.4% |

31.4% |

31.4% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Economic insecurity

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received 700€ |

73.8% |

82.3% |

84% |

76.3% |

87.3% |

|

After COVID-19 |

64.3% |

74.2% |

88% |

66.9% |

78.6% |

|

No delay in bills |

81.5% |

83.9% |

92% |

82.7% |

92.9% |

|

Delay due to COVID-19 |

14.9% |

14.5% |

8% |

14.4% |

6.3% |

Despite faring better in the economic crisis, the interviews confirm the

struggles of

families participating in socially innovative projects in terms of work-family balance. In

particular, mothers

had to juggle the re-domestication of care during the spring lockdown, which in the case of

our interviewees

implied the necessity of finding a new balance between home care and working from home.

Despite the advantages

of teleworking, mothers struggled because of the sudden lack of external support, which

included childcare and

an increased load of housework once it was no longer possible to hire external help. The

unpaid workload

increased suddenly, and couples had to find new solutions. Women struggled to cope with

remote work, care and

the impossibility of obtaining help from nannies or grandparents. The government did not put

any specific

economic measures to support families in this challenge. In contrast with the case of other

southern European

countries (such as Italy, for example), in Spain, there was no change in the usual provision

of benefits (Koslowski et al., 2020).

"Well, in the lockdown, we both started to work, both my

partner and me.

So... of course, our child was here, at home, with us, and it's true that we noticed

that there was more

housework, because of course, we had to cook more meals and go shopping more, the truth

is that we also spent

more time on that because of the queues and that it was more difficult." [Mother,

childminder group]

However, we noticed evolving dynamics between mothers and fathers. In

fact, in families

where both parents could work from home, the lockdown had an equalising effect, with care

provision balanced

between mothers and fathers - confirming what the preliminary investigations on COVID-19

published throughout

2020 ascertained (Maestripieri, 2021). For the first time, many fathers

experienced the

possibility of enjoying more time with their children: the reduction in working hours and

the possibility of

working from home meant more time to care for their children, usually a privilege culturally

reserved for

mothers. This situation aligns with recent research about fathers' changing roles in younger

generations, with

men's contribution to housework and childcare increasing significantly among the most

highly-educated profiles

(Ruspini, 2019). But even within this privileged layer of the population,

the care was

rebalanced only when fathers were forced to be at home. If they kept working in person, the

effect of the

COVID-19 emergency was to magnify the gender imbalance in unpaid work, not to reduce it.

"I think *father* is enjoying it more because he can

spend much longer with

her than he usually could. He's delighted. And he says so. Me too, eh! But it's true

that I've had the chance

of spending more time with her than *father*." [Mother, free-education nursery]

"Well, the first two weeks of the State of Alarm, both

my partner and I

worked from home. It was great (I suppose because it was also at the beginning); we took

turns teleworking,

and we were with the children more than ever, especially *partner*, who in "normal life"

on weekdays was only

with the children for a quick breakfast before work/school and when he arrived at 8 in

the evening, just to

have dinner and go to bed. But after those first two weeks that were wonderful,

*partner* had to return to

work in person, at first only in the mornings. Still, after a week, he was already doing

"normal working

hours", and I stayed (and I still am) at home with the children and telework, and it is

horrible. Before,

since *partner* was always away from home, he "did what he could", dinner, filling the

dishwasher, and little

else, so I "did the rest", a lot or a little depending on what needed to be done. We had

a girl who came to

clean the house once a week, but with Coronavirus, obviously, we asked her not to come,

and of course, I did

ALL her tasks, plus specific things like buying clothes, kindergarten registration, etc.

Before, I had a

specific time for each thing: work, home, children. Now everything's mixed together, and

being at home all

day, it gets dirtier, now we not only have breakfast and dinner. We have breakfast,

morning snack, lunch,

afternoon snack and dinner at home, so these dirty dishes are "extras". Although the

dishwasher is my

partner's job, since he's out all day, it has become "one of my tasks". He still puts

one load on, but I do

the extra one." [Mother, free-education nursery]

The situation was very different for unemployed mothers when the lockdown

started. In those

cases, they reverted to a situation where their role was to be a mother 100% of the time,

impacting other facets

of their identities. So, the pandemic was not a mechanism favouring gender equality: the

gender rebalance takes

place when women and men have the same working conditions. When women are economically

dependent on their

partners, families tend to revert to traditional gendered models of care, even though we are

usually talking

about highly educated and empowered women.

"Lockdown at the beginning was a bit... quite hard

because ehm... my partner

worked from home, but he would shut himself in, he still shuts himself in his room and

so... and so, it's not

that he can help me much and so it was me and *child* 24 hours, eh... [...] this was our

lockdown, *child* 24

hours, *partner* when he finished work, around six, seven PM. So he spent an hour with

him, the time that I

was making dinner, eh... that's all." [Mother, community care group]

In conclusion, the COVID-19 emergency has exacerbated inequalities already

present before

the outbreak. What emerges from our data is that affluent families, in which both working

members could work

remotely, could find a new equilibrium in which gendered roles could be questioned. In the

cases in which either

the partner went out to work as usual or in which mothers were not employed, school closures

were covered

entirely by the provision of women's work. In any case, in all households, the pandemic had

constituted a stress

test for the management of unpaid work when families were suddenly deprived of the external

help they usually

received from other women in the form of nannies and cleaners.

THE IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON SOCIAL INNOVATION

As far as educators in these projects are concerned, they have struggled

to survive

financially during closures. Although these projects are not formally recognised as

schooling activities, their

representative associations recommended following the same rules applied to schools and

nurseries. So, they also

closed for the entire spring lockdown. When schools re-opened in September, they followed

the same

recommendations for social distancing applied in public and private nurseries. It has been a

challenging year

for the educators involved in the projects. The higher costs compared to public nurseries

and the uncertainty

with which the school year began led to a fall in demand for socially innovative childcare

services in the city

of Barcelona. This situation arose since families were still working reduced schedules or

living on public

emergency help and could not afford the higher costs of these types of childcare services.

As noted in the previous section, the projects were already struggling to

make ends meet

before the COVID-19 emergency. Only families' fees and the projects' emergency funds could

pay the project's

fixed costs. Of the ten educators that answered our structured interview, only in five

projects it was possible

to cover fixed costs thanks to emergency funds saved before the pandemic; in the other

cases, the continuous

support of families during the pandemic was crucial. When the emergency broke out, the

families' fees made the

difference between the project surviving or having to close, but families stopped paying

their fees in only two

cases out of ten. In six cases, educators reported that at least a part of the families kept

paying their fees

even if they could not access the services because of the restrictions imposed by the first

lockdown. In one

case, the lockdown led to a project closing. The fact that most of the workers in these

projects were women

shows that, again, women were those who paid the higher price for the COVID-19 crisis,

losing their jobs more

frequently (or their individual incomes in this case) (Maestripieri,

2021).

"Lockdown happened halfway through the project moving,

which benefitted us

since we paid the rent for the old premises with our deposit. We established a

continuity fee, lower than

normal, to meet the expenses that almost all families paid since they wanted to

contribute. At the moment, we

have only been able to negotiate a temporary discount on the new rent until November.

Another lockdown could

endanger our fragile economy." [Educator, group of criança]

Furthermore, only five out of the ten projects we talked with directly had

the possibility

of accessing the special funds made available by the government for dependent workers.

Educators partially

compensated for the loss of their incomes thanks to the emergency transfers offered by the

government to

workers, but public support was only available to those who had a contract or were

officially self-employed.

Many projects had only been able to stay afloat pre-pandemic by offering unregulated

agreements to their

workers, so those workers were not eligible for benefits.

Thus, accessing public help was only possible for better funded, more

established projects

with sufficient resources to employ their workers with regular contracts. Although it is

impossible to say how

many of the current projects need to use informal arrangements to make ends meet, it

nevertheless meant that the

more precarious, new, or less profitable projects found it impossible to apply for

government aid. The unstable

situation has hindered the possible consolidation of new initiatives in the near future,

leading to a reduction

in the diversity of 0-3 childcare offered in the city and the potential loss of spaces for

citizen-led

initiatives. Fortunately, the projects dismissed their workers just in one case.

"Then, they closed for these five days and then well…

during the entire

state of alarm until June, the projects were closed. The problem was that the people who

were registered as

self-employed, those people received government aid, right? But well, as we always talk

about the

precariousness of our projects well, many people were working under the table without

being registered, so

these people, well, received collaborative quotas from some of the families, which

helped to support that

person a little. Still, some of them went through a pretty rough time." [Association

representative]

The communities behind the projects, however, were a fundamental resource.

The help was

two-fold: on the one hand, the educators had the flexibility to help those families that

were forced to keep

working in person, and they provided the care required directly in the families' homes,

sometimes even breaking

the rules and risking fines. In addition, families helped each other share childcare: the

flexibility of

teleworking allowed them to take turns caring for their children by creating bubbles in

which they could find

the external help they needed. Instead of resorting to the market (nannies) or the family

(grandparents), the

main welfare actor became the community behind the social innovation projects.

"And then many families found themselves needing someone

to take care of

their children. Right? Because although there was a state of alarm and you were supposed

to stay at home,

there were people who went out to work. And some childminders went to families' homes,

like babysitters. Those

families with essential jobs could have been covered. Well, I suppose this happened with

all families that

took their children to the public nurseries or the private ones too. They didn't have

that service and didn't

know who to leave those tiny children with, and they had essential jobs. Some

childminders did this."

[Association representative]

On the other hand, families kept paying their fees, and this money was

fundamental to avoid

closing down the projects in which their children participated. The trust and bond

established in the community

of care before the pandemic became the social resource that could overcome - at least, in

part - the worst

consequences of the crisis for the projects. However, solidarity in the community of care

did not always occur.

In some cases, the COVID-19 emergency also severely impacted household incomes, with many

fathers and mothers on

furlough or left without clients (in the case of self-employed workers). In other cases,

some of the

participants in the projects broke the mutual aid rule that sustained the community and

reverted to

individualistic solutions.

"We've kept paying, right? But less. […] Well, there

were people who didn't

want to pay. Well, there were families who understood it more as a collective project,

and there were families

who did not. And well, because I don't know, we, for example, thought that beyond the

circumstances... That

the idea is, maybe, if there is a family that can afford to pay more if there is one

that cannot ... That is,

let's collectivise the problem a bit because it's a project that we understand to be

like that, it's

collective. But no. Many people were more like, on their own. "I can't pay, so that I

won't pay." More

one-sided, instead of thinking "I can pay your share and then you will return it to me."

I don't know. So

well, there's been quite a bit of conflict. […] Now there are thirteen families. There

were fifteen of us and

two left. And we'll lose more." [Mother, free-education nursery]

In conclusion, our research findings show that COVID-19 hardly hit the

participants in

social innovations. Still, at the same time, they show that the community became a

fundamental resource for

coping with the emergency caused by the pandemic. Parents and educators helped each other,

sharing care and

financial resources to keep the projects going and finding new work-family balance even when

projects were still

officially closed.

![]()

![]()