In the last two decades, Spain has seen an increase in the role and relevance of social movements studies, although not without some delay compared to other European countries (Romanos & Aguilar, 2016; Fillieule & Accornero, 2016). This process has gone hand in hand with three other developments: first, the introduction of the topic by previously internationalized Spanish researchers; second, the late arrival of the New Social Movements (NSM) on the Spanish socio-political scene derived from the existence of a dictatorial political regime that curtailed protests and organizations demanding social change; and third, a significant increase in this research subject since the turn of the century. Progressively, and especially in the past two decades, social movements studies have constituted a specific field of study in Spain and is on its way to being consolidated thanks to the various contributions emerging from academic conferences, doctoral theses and published research (Romanos, 2011).

The present paper comes from the need to establish the state of the art regarding a field of knowledge that, as we elaborate below, has grown rapidly and has diversified into interdisciplinary lines of enquiry throughout the past two decades. From an academic point of view, theories have been refined via the juxtaposition and integration of different theoretical paradigms. From a geographical point of view, national academic cultures have become internationalized and have contributed beyond their own borders through significant theoretical approaches and case studies. From a sociological perspective, the increasing complexity of politics, societies and cultures has provided the basis for the development of sound theoretical understandings.

With this contribution, we aim to reflect on the evolution of social movements studies in Spain. We seek to further the understanding of this new academic field and to explore its genealogy. Exhaustive and up-to-date articles on this new field and its specificities with respect to other countries are still lacking, except for introductions to the subject (Romanos, 2011; Romanos & Aguilar, 2016) or reviews and analysis limited to particular aspects of the field (Morán & Rodríguez, 2022).

The work presented here thus investigates the configuration of this discipline in Spain through secondary sources (exhaustive bibliographic reviews, bibliographic databases both in Spanish and English, documentary analysis) and primary sources (semi-structured interviews with some pioneers of the field in Spain). Our discussion is located in the debate concerning Spain’s position, concerning the center-periphery axis, present in the social movement studies literature (Romanos, 2011).

SOCIAL MOVEMENTS STUDIES IN SPAIN. CONTEXT ANALYSIS OF A COUNTRY IN THE ACADEMIC SEMI-PERIPHERY

Although social movements studies in Europe cannot be considered a distinctive field of study before the 1990s (Diani and Císař, 2014), European social movements scholars have focused their works on structural factors different to those of their American counterparts. The global cycle of protests that began in May 1968 led to an interest in how the cultural changes produced by the rapid economic development of late capitalist societies fostered new values and identities that, in turn, transformed the actors and demands that dominated the social movements field (Inglehart, 1977). The work of the first proponents of the so- called "European identity paradigm" (Accornero & Fillieule 2016), such as Alain Touraine (1981) and his disciple Melucci (1989) , are of significant relevance. This approach appeared from efforts to understand the growing importance of social movements such as peace and environmental movements. New Social Movement scholars argued that the economic development of Western societies resulted in new cultural attitudes that gave birth to new claims and mobilizations. As more and more people saw their material needs being met, they began to pay attention to other struggles, thus fostering new collective identities and new types of social movements in which the role of working classes lessened.

International exchanges beginning in the mid-1980s and 1990s and the establishment of social movement studies as a subfield of its own caused the discipline to grow exponentially (Rucht, 2016). As a result, it is impossible for the limited space of this section to account for its overall development. Scholars began to pay more attention to the meso-dynamics of protests. During the 2000s, two lines of research were especially productive in the Global North. First, a group of scholars opened the debate on the “structural bias of political process theory” (Goodwin & Jasper, 1999) and of social movements research in general, while furthering the study of the micro-foundations of mobilization. These scholars developed comprehensive theories regarding the importance of emotions experienced by individuals in relation to their complaints, as well as during the mobilization process (Goodwin et al., 2009).

As we explain below, Spanish scholarship was not absent from these debates. Given the wealth of international networks and the theoretical interests found in Spanish academic circles, the country's scholars have managed to develop a diverse theoretical and methodological corpus in the recent decades. Nonetheless, they did so with some delay compared to their European counterparts. Indeed, during the last decades, social movement studies in Spain (and about Spain) have grown in depth and complexity.

Simultaneously, the integration of Spanish scholars into international academic networks and the perfectioning of theories have led the discipline to evolve from being a minor subject to one of the country’s most important fields of study. Moreover, the importance of Spanish mobilizations in two of the main contention cycles of recent decades has provided rich material for study (Tejerina & Perrugorría, 2018). The leading role of the alter-globalization movement, in which demonstrations against the Iraq war in 2003 were key, and the 15M/Indignados cycle of protests, which began in 2011, legitimized the study of social movements’ action in Spain (Jiménez & Calle, 2007; Romanos & Aguilar, 2016). These events sparked an interest in social movement studies across numerous disciplines such as Sociology, Political Science, Anthropology and Contemporary History.

METHODS AND RESEARCH DESIGN

In order to offer a clear overview of the evolution of social movement studies in Spain, we combine both quantitative and qualitative data. Quantitatively, we present descriptive statistics regarding the number and type of publications from scholars interested in social movement studies in Spain (both Spanish and international).

Publication-related data is extracted from the Dialnet and Web of Science databases. These bibliographic databases were selected for their accessibility and for offering the most information on academic publications referring to the Spanish context. While Dialnet is the main bibliographical source for Social Sciences literature in Spanish, Web of Science is its equivalent for publications in English. We used the former to analyse books, book chapters, doctoral theses and articles in academic journals, given that they represent the most common type of publication in this field. However, in the Web of Science case, a preliminary analysis showed that very few books exist on the Spanish case yet. Therefore, we limited our selection to publications in scientific journals indexed in said database2.

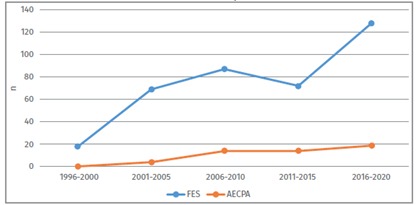

Furthermore, we draw on complementary data from the Spanish Federation of Sociology (FES by its Spanish acronym) and from the Spanish Association of Political Sciences and Administration (AECPA by its Spanish acronym) to account for paper presentations referring to social movements, as well as scholarly contributions to those conferences. These periodic scientific gatherings are of special importance since they constitute strategic research events in which different works and general progress in the discipline are presented and discussed (Fernández-Zubieta, 2022). We also analyse the contributions of academics and activists on the main developments of Spanish social movements collected into the Betiko Social Movements Yearbook. Published each year between 1999 and 2019, this yearbook is connected to militant research. Overall, this data set allows us to trace the evolution of the field of social movement studies in Spain from the 1980s to the last decade.

The qualitative input builds on semi-structured interviews conducted with pioneering researchers in this field of study in Spain, from different disciplines. This “expert” profile - defined as pioneering scholars in their respective disciplines - has been the central criterion in the interview sampling. The identification of historical periods constituted a complementary criterion to ensure a minimum representation of experts for each period that we analyse (from the 1980s to the 2010s onwards). Following this sampling, we ensured a diversity of informants who, given their central position in their respective disciplines, possess accumulated knowledge allowing us to approach the socio-historical reality of this field of knowledge through orality (Table 1).

Table 1. Sample of qualitative interviews conducted with pioneers in these studies.

Additionally, we conducted documentation of reflections, interviews and biographical notes on these pioneers. As these written testimonies contained reflections on how the field had been configured, accessing them was key in order to design the interviews and to identify the different patterns that shaped the field throughout these decades. The Table 2 displays the layout of sources and data used in the present article.

Table 2. Design of the type of sources and quantitative data analysed.

RESULTS. THE EMERGENCE AND CONSOLIDATION OF SOCIAL MOVEMENTS STUDIES IN SPAIN

Similarly, to other countries, social movement studies in Spain are highly influenced by the evolution of Spanish politics. Spain’s late democratization, compared to other European and American countries, delayed the research on key aspects that make up open societies, such as civil society and social movements (Laraña, 1999). Furthermore, the underground nature of progressive movements under the Franco regime and the important presence of the Spanish Communist Party, anarchist groups and unions in these networks caused a late arrival of NSM, otherwise growing in Europe in the late sixties (Romanos, 2011). It is not until the 1990s that the discipline begins to garner attention in academic circles thanks to the efforts of some scholars. Subsequently, the strength of the Global Justice Movement at the turn of the century provided fertile ground for the growth of social movements and protest as a research field. The 2011 15M/Indignados movement and the burst in protest and social movements that unfolded also led to an impressive increase in academic research on social movements. Such a burst reaches beyond sociology, at times even beyond social sciences, and permeates other disciplines.

We now proceed to present a chronology of the evolution of social movements studies in Spain. The following sections detail the influence of political events on the evolution of these studies in Spain, as well as the key figures in the growth and internationalization of the discipline. In order to do this, we draw on academic publications data and on our interviewees’ narratives.

The beginnings: the early studies during the Transition to Democracy and in the Eighties

How did social movements studies start within Spanish scholarship? In truth, historians had always studied social movements, but in a way limited to historiographical studies on very specific movements and protests: classic movements, generally workers movements, but also rural or nationalist movements framed within certain periods of Spanish contemporary history (Pérez Ledesma & Cruz, 1997; Ortiz de Orruño & Castillo, 1997; Cruz, 2009).

The study of mobilization patterns and strategies, as well as the profile of these movements, began to garner interest in the 1980s. This is when the so-called NSM began to gain momentum and when social sciences disciplines that traditionally research social movements developed the capacity and interest to study social conflicts and movements (Durán, 2001; Romanos & Aguilar, 2016). It is worth noting that the development of NSM in Spain takes place in circumstances affected by the country’s history. The political turmoil during the transition to democracy prevented the independent appearance of the NSM. Instead, they evolved hand in hand with workers’ unions and other movements that were part of the same extra-institutional push for democracy (Alonso & Ibáñez, 2011).

The progressive consolidation of the sociological study of social movements paralleled the evolution of the NSM. And if the evolution of the New Social Movements is more delayed, this is also the case with studies on this issue as can be seen in empirical evidence in the form of contributions to conferences (as seen below), articles in scientific journals or books published on the issue (Romanos & Aguilar, 2016; Betancor et al., 2019).

One of the most outstanding and studied movements was the civil and urban movements present in the main Spanish cities during Late Francoism and the Transition. In what constituted the first successful internationalization of Spanish social movement studies, this movement was especially studied and theorized by Manuel Castells (1972) . Based on his work on neighbourhood struggles in Madrid, and later incorporating a transnational comparative perspective, this author theorized urban social movements as proactive agents in the realm of collective consumption and as problematizing new everyday life issues (new social contradictions and conflicts, housing and transport demands, access to collective services). Drawing on a then neo-Marxist approach, he conceived them as particular historical expressions of that moment: political struggle and urban problems are tightly intertwined, developing new social contradictions at the core of our daily life (Castells, 1983). He opened a line of research on urban movements as “city producers”, later complemented in the eighties and nineties by the participatory methodologies approach, to encourage the participation of citizens and neighbour movements in urban planning (Villasante, 1994).

Within the Political Science discipline, and except for some sporadic studies, social movements were not considered a line of research until the 1990s. In large part, this change resulted from the work of Pedro Ibarra (Universidad del País Vasco) as a precursor to these studies. The previous situation largely came from Spanish mainstream Political Science’s conceptualization of political behaviour being focused on the institutional, thus disregarding civil society and social movements (I 8). Political Science’s “conservative configuration of the academic hierarchy” at that time also contributed to this (I 4).

As a result, these studies were isolated in Spain in comparison to the situation in the United States and the rest of Europe. However, the legacy of Marxist thought was maintained through the incorporation of European neo-Marxist approaches and existing studies were thus closer to the movements’ claims themselves and, in that sense, less “institutionalized” (Rucht, 2016). This denotes a specific feature of early social movement studies scholars in Spain. According to several interviewees (I3; I5; I8; I9), these scholars were closely related to activism and their interest in theorizing and analysing movements came rather from their own political activity than from a purely academic interest. As one informant pointed out:

“That also meant that the people who were there, who studied social movements at that time, were coming from the most traditional left-wing pattern (…). And it seems to me that this also resulted in bias. For instance, there was a line [of research] on social intervention, which was the most activist line. This line turned its back to the North American development (...). I am quite critical of these beginnings because I believe they were very much activist discourses and writings. So, I think this bias prevented it from being a more powerful academic movement, with some exceptions” (I 3).

Following democratization and institutional stability in Spain, some researchers were able to conduct visiting exchanges abroad during this period from which they imported new theoretical paradigms that would end up being key later. These research visits represented the early stages of the constitution of international networks between Spanish scholars and their American, European and Latin American colleagues3. These stays allowed researchers to slowly but increasingly insert themselves in the debate of the most analytical and sophisticated approaches from the US, and to combine them with the action and identity approaches predominant in Europe (I 5). Likewise, researchers combined stays abroad with research at the now-defunct Center for Advanced Studies in Social Sciences (CEACS for its Spanish acronym). The latter, although based in Spain, was an international environment in itself (international professors, visiting stays, and access to many specialized resources...) (I 9). Pioneering research - among which we can cite Sampedro (1997) , Jiménez (2005) , Calvo (2009) and Trujillo (2009) - was conducted in this center and would later be published and be key to opening lines of research within these studies.

The first momentum: the nineties

The first point of consolidation of these movements in Spain is their official recognition in the discipline of sociology. The Research Committee on Social Movements of the Spanish Federation of Sociology, promoted by Enrique Laraña, was created during the 1992 Spanish Congress of Sociology (Fernández-Zubieta, 2022). This Committee was fundamental in these first steps towards academic institutionalization as the first academic group in Spain bringing together scholars working within this line of research or similar ones (I 1). This milestone is worth highlighting because such a recognition would take many more years in other Spanish disciplines such as Political Science or Anthropology.

From this decade onwards, a sound theoretical dialogue began with regard to this academic discipline. This debate drew on a multitude of theoretical reflections, case studies and comparative studies, and was often linked to rapid changes happening on the street. Some crucial books were translated for the first time, cementing the literature on social movements (Laraña & Gusfield, 1994; McAdam et al., 1999) and the first reader coming from Spanish scholarship was published (Ibarra & Tejerina, 1998). Additionally, case studies and lines of research were progressively normalized, still within close proximity to political sociology (Funes, 2007) (I3; I9).

At the same time, the theoretical debate imported from Europe and the United States begins to take place (Rutch, 2016) between structuralist approaches of resource mobilization and political process on the one hand - being dominant at that time (Ibarra and Tejerina, 1998: Tejerina et al., 1995) - and identities-oriented and constructivist approaches on the other. In this sense, Enrique Laraña is a central figure in importing US constructivist approaches and putting them in dialogue with identity approaches from Europe, conducting a significant amount of empirical work with NSM in Spain (Laraña & Gusfield, 1994).

Likewise, research from the Basque Country and on Basque society also opens up an important line of research because it constitutes a particular social laboratory where contextual specificities influence the action of social movements: nationalist cleavage, ETA terrorist violence, significant associative fabric, and an earlier entry into postmaterialist society (thus allowing a new type of social demands). According to an informant, conducting militant research in a hyper-mobilized society such as the Basque Country led to certain difficulty in studying issues contrary to the positions of movements close to the Basque nationalist left (Abertzale) (I 5) (see Figure 1).

As far as theoretical and empirical publications and contributions are concerned, it is at the end of the 1980s and in the 1990s - when the NSM literature entered the scene and when case studies were diversified - when theoretical debates started flourishing. As an informant pointed out, this is when the dialogue between different approaches started in Spain:

“you could feel that there is going to be a fusion of the different approaches. For example, efforts were already being made to connect all approaches based on political process, on the structure of political opportunities, with all the literature on frame analysis” (I 9).

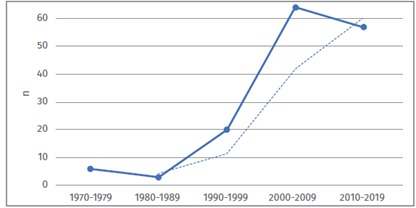

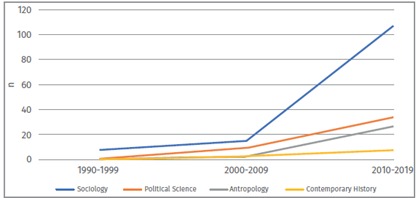

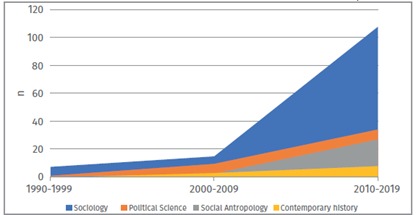

Figure 1 also reveals a quantitative increase in articles compared to the previous decade. This burst occurs in a similar way regarding published books on social movements (figure 2).

The theoretical import of different scholars was also boosted in two ways that can even be complementary: research stays abroad and thesis supervisors’ influence. Moreover, this is the first academic generation scholarly socialized in studying social movements, whereas the previous one studied them as part of the Political Transition’s conflict or social change rather than as an object in itself (I 7; E 8).

The early institutionalization of the discipline and the international stays of some Spain-based researchers contributed to this increase in academic production on social movements:

“ it is from the 90s, which is about when the Spanish researchers’ system opens up, in the social sciences field, because somehow they manage to gain a presence abroad. And many doctors begin to be trained through stays abroad. Networks with other researchers in Europe start to be established” (I 9).

Therefore, social movement studies in Spain begin to receive institutional recognition in the 1990s. Enrique Laraña launched the first research network focused on the study of social movements, then officially recognized by the Spanish Federation of Sociology (FES) during its 1992 national congress. The Research Network on Social Movements of the Spanish Federation of Sociology becomes the first official group to bring together scholars interested in the topic and constitutes the first step in the discipline’s institutional recognition. Laraña contributed to the field with important theoretical developments. However, this period was still marked by a certain stigma being attached to social movements studies within Spanish academia due to the existing links between the field and the movements themselves - in a manner similar to the connections between these studies’ theoretical developments and engagement with (and in) the NSM in Europe (Rucht, 2016). As can be seen in the case of the FES Committee of Social Movements: “the Committee of Social Movements was something that had certain stigma, it was less academic somehow and, in turn, was more advocate” (I 3).

In parallel to Laraña’s constructivism in Madrid, the Basque Country’s specific reality encouraged researchers to develop their own lines of research. The cleavage around nationhood and a highly mobilized society around it, as well as the terrorist violence of ETA, influenced social movement scholars who wrote extensively on these issues from the perspective of resource mobilization and political process theories (Tejerina et al., 1995; Casquete, 1996; Ibarra et al., 1998; Funes, 1998). Additionally, the Basque Country’s reality influenced social mobilizations in the rest of Spain, with some of the largest demonstrations of the nineties being those opposing ETA's terrorism (Laraña, 1999; Adell, 2000).

Moreover, the normalization of protest in Spain during the 1990s gathered attention beyond the academic sphere (Jiménez, 2011). It was at that time that public institutions began to publish statistics on demonstrations and participation numbers. As Adell points out, “institutional interest in the systematic study of mobilization begins when it is established that once the democratic process had started the mobilizing pressure does not decrease, but it increases” (Adell, 2000, p. 2).

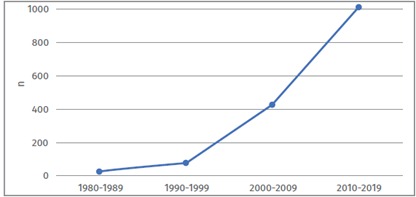

Figure 1. Number of articles on social movements published in Spanish (1980-2019).

Source: own elaboration based on Dialnet data.

Figure 2. Number of books on social movements published in Spanish (1980-2019).

Source: own elaboration based on Dialnet data.

The institutionalization of the field in the early 2000s. An Europeanization of the research agenda?

Edward Shils suggested three basic indicators to determine whether a discipline is being institutionalized: an increase in students; an increase in dedicated research institutes; an increase in journals disseminating findings and discussing theoretical approaches (Shils, 1971, p. 39 onwards). Following this criterion, the institutionalization of social movement studies in Spain can be located at the end of the 2000s. At that time, there were research centers and institutes, contributions to journals, and more and more students (of both master's and doctorate) interested in these lines of research.

In this first decade of the 21st century, lines of research really began to be diversified beyond the political process vs. collective identity debate that had dominated the field up to that point. The changes brought by the Global Justice Movement and the progressive Europeanization of Spanish social movements led to a broadening of research foci. As such, this constitutes a convergence with European mobilizations and protest hotspots. Important and high-quality works are being produced and presented in international fora. As Benjamín Tejerina pointed out:

“The distance that existed in the '80s and '90s in our works, in relation to other works in this field in other European countries, has progressively been shortened. Not only because we now almost use very similar bibliographies, but because mobility means that there are elements of hybridization, which are very interesting” (in Betancor et al., 2019, p. 205 ).

Already in the mid-2000s, some scholars suggest that this current is going through a process of maturation within Spanish sociology. “Irregular, barely institutionalized and above all personal contacts are maintained with researchers from similar international organizations” (Adell et al., 2007, p. 488 ). Regarding research topics, a burst in the study of NMS is observed and “in many cases, the main task has been to try and reach an agreed definition of social movement, its typology, its characteristics, or to study its repertoire” (Adell et al., 2007, p. 491).

On the basis of this paradigm shift following the Spanish participation in the Global Justice Movement, Manuel Jiménez and Ángel Calle (2007) argue that the evolution of social movements in Spain is marked by a progressive configuration of cohesive and transversal identities and by an increase of interorganizational coordination. This represented a major change towards a new model of social movement progressively being Europeanized (network structuring, collaborative mobilization agendas, etc.) (Romanos, 2011). This paradigm shift also crystallizes in works published with prestigious editorials that analyse civil disobedience as a tactic of one of the most relevant movements of the nineties, as is the anti-militarist movement (Ajangiz, 2003).

These changes in the study of social movements in Spain bring with them a Europeanization of the research agenda, as well as of researchers’ networks. Authors are increasingly engaging with international debates and case studies, and international scholars are increasingly interested in the dynamics taking place in Spain. Additionally, a growing number of comparative studies include Spanish cases (Rootes, 2004), and ever more individual case studies approach and locate Spanish movements within the broader European context (Jiménez & Calle, 2007; Calvo, 2009).

As is the case in other countries (Accornero & Fillieule 2016; Rucht 2016), Spanish researchers’ international mobility is key to the internationalization of social movement studies in Spain. These contacts were mostly informal, based on researchers’ personal networks rather than on institutional affiliations (Adell et al., 2007, p. 488 ). The political dynamics taking place within the Latin American left led many Spanish activists and researchers to develop transatlantic networks, thus increasing the internationalization of studies on Spanish social movements beyond the dominant Anglophone networks. A shared language facilitates the strengthening of relations in both directions. On the one hand, a significant number of Latin American scholars study and start their careers in Spain. On the other, the efforts of the Latin American School of Social Sciences (FLACSO) and of the Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO) to build solid research networks in the region have also reached many Spanish scholars, thus promoting the transmission of research interests and of academic knowledge across the Atlantic (I 6).

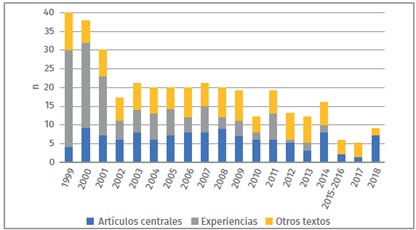

Likewise, activist research and scholarship-activism connections were increasingly significant on the back of Pedro Ibarra’s work as initiator of Betiko Foundation's Yearbook of Social Movements. This annual publication includes reports, analyses and reflections on different movements and protests within the wide thematic diversity of movements in Spain:

“There is an important question that has to do with the field’s development and that is the presence of entrepreneurs. And among those entrepreneurs Pedro Ibarra is a very important example. His contribution goes beyond his work itself, because what he does is this: to promote training, to promote a school of thought, to create research groups, to connect them with other research groups” (I 9).

The Yearbook achieves relevance especially in the first part of the decade, as it becomes an indisputable reference in terms of social movements. Its importance (and limitation) lies in the fact that it provides an in-depth overview of all the different “progressive” social movements (classical, NMS, etc.) and puts them on the social movements studies’ agenda. Most importantly, it lays the foundation for the dialogue between academia and social movements through publications and initiatives funded by the Betiko Foundation, which is dedicated to promoting and disseminating knowledge and studies regarding social movements. As a result, the Yearbook has been the reference publication for understanding the evolution of social conflicts and of collective action in Spain during the 2000s, at a time when social media and the Internet did not yet play such a prominent role in transmitting information about these events. As a space open to both academic and activist reflections, this publication is crucial to the continued growth of activist research, something that increasingly differentiates Spanish social movement studies from their European neighbours. It also contributes to close and lasting collaborations between researchers, professors, thinkers and social movements activists4 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Number of articles and texts published in the Yearbook of Social Movements (1999-2018).

Source: Betiko Foundation.

From this decade to the present days, and in a way similar to Betiko, the Traficantes de Sueños Bookstore and Publishing House has played a central role in disseminating activist culture, and in translating theoretical books about - and practical experiences of - political dissidence, new axes of social oppression, and social movements. Following the changes pertaining to each political and social context, from the Global Justice Movement to the present, its role as an infrastructure for social movements has been fundamental for the movements’ aggregative capacity and for the introduction of new debates (Betancor, 2021). Additionally, the Fundación de los Comunes, founded by this group in 2011, has served as a theoretical and practical training center for activists. Through its various annual courses on topics directly linked to social movements, it is essential if we are to understand the intersection between scholar and activist research today.

Regarding academic conferences, we observe that paper presentations on social movements at the Sociology and Political Science annual congresses increased steadily during this decade (figure 4). Clearly visible is the upheaval that the 2011 15M represents and the increase in academic contributions linked to it, which begins in 2011, especially in terms of contributions to congresses.

The last decade. The 15M cycle and the blossoming of social movements studies

Following the 15M protest cycle and the mobilizations surrounding it, the last decade has witnessed a burst in studies and thus converted Spain in the focus of international attention. At the same time, Spain was converted in object of research as well through case studies and comparative studies analysing different dimensions of the protest (I 7). The Figure 5 shows a stark increase in doctoral theses submitted in the 2010-2019 decade that displayed “social movements” among their keywords. This testifies to the research topic going mainstream, even in disciplines other than Sociology. Another significant fact is that many of these theses pertained to disciplines that had traditionally ignored this phenomenon in Spain. In particular, anthropological or political studies linked to social movements stand out.

Returning to conferences’ papers data, a surge in research on social movements is observable from the 15M cycle onwards. Indeed, from 40 presentations on this topic in the 2010 FES Congress, numbers reached 72 in the 2013 Congress. This increase of 80% in just three years clearly illustrates the centrality that these studies were gaining, as well as the sociological importance acquired by the 15M phenomenon. As a result, the strength of the 15M - and of other movements happening during its protest cycle - placed Spain at the center of international research on social movements. Numerous researchers based in Spain and abroad grounded their research agendas on these cases. As one interviewee noted:

“Now, every extra-institutional participation is mainstream, it is everywhere. So, even in political science, people who dedicated their careers to studying other phenomena were getting interested in social movements. For example, it is precisely when protest starts to be normalized that you can begin to use surveys to analyze it. And this attracts a lot of researchers (...). The 15M, the 8M, the pensioners, are movements attracting the interest of researchers from other countries” (I 9).

Figure 5. Doctoral theses in Spain on social movements in Spain (1990-2019).

Source: own elaboration based on Dialnet data.

Another outstanding feature of this decade is the consolidation of this field of knowledge as one that most attention receives at the FES congresses. As far as authorship is concerned, the gradual incorporation of women in what is traditionally a very much masculinized field of studies stands out. In one decade, the rate of female presence in these presentations at the FES congresses went from 0.28 to 0.38 within the Social Movements Working Group. Overall, this group consolidated its position as the fourth committee with the most received presentations (see Table 3).

Some of these studies focused on the 15M and on the organizations involved in said mobilization (Flesher, 2015; 2020; Portos & Carvalho, 2019; Portos, 2021). Others examined pre-existing organizations that grew during this period and continued their struggles beyond it, such as the Platform of People Affected by Mortgages (García-Lamarca, 2017; Martínez, 2019; Romanos, 2013; Santos, 2020). The same happened around the feminist movement and the March 8th mobilizations, as examples of the new transversal mobilizations spearheading the post-15M cycle and in which the Spanish case has been an international reference (Campillo, 2018; Galdón, 2018; García & Cueli, 2021).

Table 3. Evolution of conference papers, ranking and female presence in the FES Social Movements Research Committee (1995-2016).

| Year | n contributions | Rank | I. Female pres. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 41 | 9 | 0,28 |

| 2007 | 45 | 7 | 0,28 |

| 2016 | 69 | 4 | 0,38 |

Source:Fernández-Zubieta (2022) .

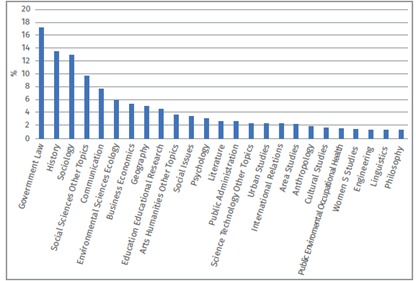

The Web of Science (WOS) data reveals that publications referring to “social movements in Spain” grew exponentially from the second half of the 2000-2010 decade. As can be seen below, more than 90% of these publications are concentrated between 2007 and 2020, 2014 being the moment when this growth was most acute (Figure 6).

The numerous contributions of researchers to international associations and journals constitute another example of the internationalization of Spanish research on social movements. Among others, some scholars stand out: Cristina Flesher in the journal Social Movement Studies; Montserrat Emperador in the Research Network on Social Movements of the Council for European Studies (CES); Benjamín Tejerina in the Social Movements, Collective Action and Social Change Research Committee of the International Sociological Association (ISA); or Eduardo Romanos in the Research Network on Social Movements of the European Sociological Association (ESA) and in the journal Social Movement Studies. Their roles and standing in these academic networks contribute to improve Spanish academia’s international profile through collaborations with international researchers, and to increase international attention on Spanish social movements through their presentations in these fora.

One of the decade’s novelty is the exponential increase in publications in English adopting various approaches and deploying both quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Regarding the former, “protest event analyses” focused solely on Spain (eg Anduiza, et al., 2014; Portos, 2021) and in comparative studies (Portos and Carvalho, 2019) have a significant impact. These studies contribute to this methodology’s consolidation among people interested in social movements in Spain, resulting in new research projects both internationally compared and financed (Disobedient Democracy, directed by Danijela Dolenec) and Spain-focused and -financed (ECOPOL, directed by Eduardo Romanos). Network studies are also being consolidated - whether focused on the 15M (González- Bailón et al., 2011) or on other types of mobilization (Ciordia, 2021) - and progress is being made in experimental methodologies (Muñoz & Anduiza, 2019).

Numerous qualitative international publications were similarly inspired by the 15M and other connected mobilizations. In the case of the 15M, some have explored its origins and impacts (Flesher, 2020), as well as other characteristics of the mobilizations (De Guzmán, et al., 2016; Romanos, 2016; Díez, 2017). Beyond it, scholars’ attention in international journals has also been directed to social organizations, with the Platform of People Affected by Mortgages (PAH) being particularly relevant (García-Lamarca, 2017; Martínez, 2019; Romanos, 2013; Santos, 2020).

Likewise, as can be seen in the following figure, international publications on social movements in Spain recorded in WOS are produced from different disciplines such as Political Science, History or Sociology, but also Geography, Communication Studies or interdisciplinary studies (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Articles on social movements in Spain in WOS, 1980-2020.

Source: own elaboration based on WOS data.

Figure 7. Disciplines of articles on social movements in Spain in WOS, 1980-2020.

Source: own elaboration based on WOS data.

In this sense, the Europeanization of this research agenda truly takes place in this last decade: theories and approaches are imported; Spain-based studies are presented in international settings and fora through stays abroad, theses in prestigious centers and researchers residing abroad. Another important feature that has been observed in this research is that we are witnessing the first fully internationalized generation of researchers: they read everything in English, most of them are part of important research centers, they participate of the most recent debates, they hold important positions, and they contribute to the production of texts in English and Spanish that are internationally taken into account.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we find that social movements studies in Spain are in a clear process of institutionalization. Undoubtedly, the last decade has been crucial in making it easier for researchers to conduct international studies and studies focused on the Spanish case, and in inserting them in the main international debates. As a result, social movements studies in Spain have lost the sort of academic stigma identified by Rucht (2016) according to which fellow social scientists did not consider them as a serious field. This perception has been reversed and activist research does not define Spanish research so much anymore.

From the chronology and data presented above, it seems clear that social movement studies in Spain is an emerging discipline with a promising future. The number and quality of research projects and publications have increased considerably. Moreover, these works are engaging in important national and international debates and are being recognized in global fora.

We identify four areas in which we see significant potential for advancing research on social movements in Spain. First, social movement studies in Spain would benefit from further analysis of the contexts and structures in which social movements originate. Second, the discipline could put more emphasis on quantitative and mixed methods studies. Thirdly, the growing importance of conservative and far-right movements should be reflected in a greater effort to research and understand them (Esseveld & Eyerman, 1992; Santos & Geva, 2022). Finally, social movement studies should persist in their institutionalization as a discipline and should encourage collaboration between areas of knowledge.

Although it may seem that the main current of research on social movements has swung between an emphasis on structure and the prioritization of movement-focused approaches, a comprehensive understanding of mobilization requires paying attention to different levels of analysis (Petrova & Tarrow, 2007). Except from some exceptions including meso and macro perspectives in their analyses (see Calvo 2009; Díez & Laraña, 2017; Flesher, 2020; Portos & Carvalho, 2019; Portos, 2021), most research on Spanish social movements are case studies. Movement-focused and ethnographic studies are central to our discipline. However, accompanying them with relational and interactive approaches that combine other levels of analysis will provide a more complete picture of how activists operate within the structures conditioning their collective action.

The methodological richness observed in the studies of Spanish social movement studies should be maintained. In this sense, studies of Spanish social movements should follow international trends in social sciences and further engage with mixed and multi- method approaches (eg. Terriquez, 2015). These efforts will provide a more nuanced picture of mobilization processes and mechanisms.

An exhaustive description of mobilization would also require scholars of Spanish social movements to engage with conservative and far-right movements, which have grown in importance in recent years (Álvarez-Benavides, 2018). This task often faces the challenge of accessing data. However, some researchers have gained access to this type of movement (see Greskovits, 2020; Santos & Geva, 2022) or have produced their own quantitative data (see Van Dyke & Soule, 2002). Although, in Spain as in other countries, the bias towards progressive movements is evident in social movements studies, a greater methodological effort to explore these protests will shed light on new demands and social mobilizations, as well as on how they are framed and politicized by social actors.

Finally, studies on social movements in Spain need to maintain their institutionalization process in order to formalize collaborations between researchers and disciplines. In this sense, the work of research networks and nodes such as the FES Research Committee of Social Movements together with their European counterparts (European Sociological Association Research, Network 25) or international ones (ISA, Research Committee 47 and 48; Latin American Association of Sociology, Working Group 19), or institutions such as CLACSO, are clear examples of this trend. To pursue in this direction will grant social movements studies a greater visibility and a fruitful research space for academia.