INTRODUCTION

Latin America witnessed a resurgence of social movements and protests during the

1990s and early 2000s (Almeida, 2007; Silva, 2015). While in the 1980s citizens demanded

the end of military rule and the reestablishment of democracy, in the 1990s mobilizations

targeted the political elites who had endorsed the neoliberal doctrine of the Washington

Consensus. In several countries, citizens took to the streets to challenge the privatization

and liberalization of pensions, healthcare and education and to manifest their discontent

with rising inequalities and poverty rates. This situation began to change in the decade of the

2000s when the region experienced a period of sustained social policy expansion intended to

increase social protection for the many social groups outside of formal employment and not

covered by contributory social insurance (Garay, 2016). The magnitude of change was striking,

and several authors have described this period as a turn toward universalism (Franzoni &

Sánchez-Ancochea, 2016; Pribble, 2013). Almost every country in the region introduced some

form of basic social assistance, healthcare, pension and education (Cecchini & Atuesta, 2017).

Between 2002 and 2014 poverty rates in the region fell from 45.9 percent to 30.7 percent and

the Gini index decreased on average 5 percent (Comisión Económica para América Latina y

el Caribe [CEPAL], 2018).

Did popular mobilization influence the “turn toward universalism” in Latin America?

Social policy analyses have rarely considered the effect of protests and social movements

on social policy reforms. For this literature, the key factors in the study of policy change

fall in the institutional arena, in particular in the dynamics of electoral competition and

the political ideology of political parties. However, an emerging strand of the literature

has shown an influence of social organizations and protest campaigns on the creation

of programmes for vulnerable social groups. Case studies demonstrate a significant

involvement of trade unions and organizations of the unemployed throughout the process

of inception and design of the Renta Dignidad in Bolivia (2008) and the Plan Jefes y Jefas

de Hogar in Argentina (2001) (Anria & Niedzwiecki, 2016; Garay, 2007). This literature shows

that innovation in social policy was driven by popular movements, and that the alignment

of popular demands and government’s agenda was a difficult and time-consuming process

involving negotiations both within and outside political institutions.

Latin American countries have a long, recurring history of popular movements demanding

greater equality, inclusion and democratization (Almeida, 2007). The latest of such protest

waves occurred at the turn of the century. Scholars of the left turn in Latin America have

focused on the electoral victories of left-wing parties and coalitions across the region

started with the election of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela in 1998, relating these outcomes with

widespread social discontent towards the liberalization of the 1990s (Arditi, 2008; Beasley-

Murray, Cameron, & Hershberg, 2009b; Levitsky & Roberts, 2011; Silva, 2009). Some authors

have interpreted this period as the struggle for (re)incorporation of those groups that

suffered exclusion during the heyday of neoliberalism (Rojas, 2018; Rossi, 2017), while others

have seen the governments of the left turn as more willing to undertake social welfare roles

(Levitsky & Roberts, 2011). Overall, the main goal of this literature was either to explain a

certain political outcome –the electoral victories of the Left– or political process –the rise of

grassroots movements–, but the social policy dimension was not central or was regarded as

a by-product of political change.

The aim of this paper is to extend current theoretical frameworks used to explain the

inclusive turn in Latin American social policies by incorporating protest. We argue that social

policy reform is shaped by the broader configuration of the polity, in particular by the ways

in which contentious and institutional politics interact and shape each other (Fourcade &

Schofer, 2016). Thus, we do not contend the relevance of electoral dynamics and political parties, but rather that differences in the ways in which institutional and contentious politics

combine affect the policy process and the very chances of some reforms to be considered

and implemented. The paper is organized as follows: first it elaborates on the mechanisms

linking protest and expansive social policy reforms; it proceeds by presenting empirical data

on contention in the region in the period 1990-2010 and the relationship between protest, the

strength of the left and social policy outputs in healthcare and social assistance (conditional

cash transfers and non-contributory pensions). The final section offers concluding remarks

about the role of protest in the politics of social policy reform in the region.

THE CONTENTIOUS POLITICS OF SOCIAL POLICY REFORMS

Studies of the inclusive turn of the 2000s in Latin America stress the importance of a

combination of economic, institutional and political factors, in particular the increase in

governments’ resources due to the rise in commodity prices and the strength of the Left across

the region (Huber & Stephens, 2012; Levitsky & Roberts, 2011). These factors are important

but only look at political dynamics within the electoral arena. In this section we make a case

for expanding these theoretical frameworks to incorporate the influence of protest on the

decision of governments to expand social protections for marginalized social groups.

Social policy reforms are the outcomes of power relations and political struggles. Political

parties are crucial actors in policymaking, and parliaments are one of the main settings

where social conflict is mediated, popular demands accommodated and diverging interests

negotiated. However, formal institutions are not the only arena of political exchange, and

Latin America provides strong evidence of the power of contentious politics (Almeida, 2007;

Silva, 2015). It is not uncommon in the region for protests to scale up into large episodes of

unrest (e.g. the uprising in Chile of October 2019, the December 2001 protests in Argentina,

or the water wars in 2000 in Bolivia). These can undermine the capacity of authorities to

govern and might lead to systemic impacts such as transformations of the party system.

Furthermore, groups such as the poor, the young, the unemployed and those in the informal

economy are often comparatively less inclined to vote and to join political parties, thereby

reinforcing a trend of underrepresentation of their interests in political institutions (Offe,

2013). Compared to electoral politics, the protest arena is more open to political actors

who lack regular access to institutional channels, and thus enhances political participation

among traditionally excluded constituencies (Kriesi, Koopmans, Duyvendak, & Giugni, 1995).

As such protest is an important channel for outsiders to make demands for more egalitarian

social policies.

Drawing on studies on the outcomes of social movements, we identify a two-way

relationship between collective mobilizations and social policy (Amenta, Caren, Chiarello,

& Su, 2010; Giugni, 2008). On the one hand, social policies create categories of people

(the beneficiaries of a programme, those excluded from social security). Over time these

categories can solidify in collective identities and organizations which mobilize to further

their interests. On the other hand, scholarship suggests a number of mechanisms through

which protesters can force governments to take their demands on board. Governments can

be induced to negotiate with protesters because they have an interest in reducing social

conflict and maintaining peaceful societies. Protests also serve as signals that indicate

pressing, unresolved issues that must be addressed by governments. Governments will

be more open to consider these issues either because of their ideological proximity to

protestors, or because they mount an electoral threat – by withdrawing electoral support

or by endorsing political challengers (Ciccia & Guzman-Concha, 2018; Hutter & Vliegenthart,

2016). The extent to which these effects occur depends on the size and frequency of the

protests, but also on the capacity of protesters to sway public opinion in their favour, forge alliances with institutional actors (e.g. trade unions, political parties), develop coalitions with

other civil society organizations, and sustain and expand these linkages over times1.

The policy impact of protest can be direct, indirect or deferred. By direct impact, we refer

to short-term responses of authorities such as changes in the policy agenda of political

parties, the adoption of new measures by governments, the inclusion of representatives

of social movement organizations in the policy process (e.g. in parliamentary hearings or

committees overseeing policy implementation) (Amenta et al., 2010; Giugni, 2008). While

protest can sometimes produce short-term impacts, many effects of protest on policymaking

take time to materialize. By indirect impact, we refer to effects that occur in the middle to

long-term as a result of protests disrupting patterns of electoral competition. In relatively

consolidated democracies, social movements can become threats for officeholders and/or

improve the chances of challengers. Other indirect effects concern cultural changes produced

by protesters as a results of them entering into public opinion battles –with protestors using

their visibility and legitimacy to persuade growing numbers of people (Giugni, 2008). Indirect

impacts also include potential spill-overs effects whereby protests initially targeting a specific

policy sector (e.g. education, poverty relief) produce changes in other sectors or a larger

impact on the whole system of social protection. Finally, deferred impacts refer to policy

changes that occur long after the initial unrest was initiated. These effects can be gauged

through the historical processes of co-transformation of protestors and the political milieu

in which they act. Some of these effects occur because activists transform existing parties

from within by taking its agenda and/or leadership (Skocpol & Williamson, 2016), or enter the

political arena with their own political platforms, thus securing a stable, autonomous voice in

the institutional arena (Anria, 2018; Della Porta, Fernández, Kouki, & Mosca, 2017).

Although social movements mobilise to achieve their goals, reforms can be blocked by

other groups who see their interests or goals threatened. Also, issues might lose relevance

over time, and unforeseen events such as economic downturns can reduce governments’

room for manoeuvre and increase competition for available resources. This highlights

how the effect of protests on social policy reforms is mediated, i.e. it depends on other

components of the political environment (Amenta et al., 2010). Therefore, the shape and

extent of social policy reforms is dependent upon changes in the sites of decision-making,

including governmental offices, parliaments, corporatist institutions and policy communities.

Protest movements are more likely to obtain concessions when they are able to produce

significant changes in the existing balance of power. In Latin America power holders tend

to see social movements more as threats than as signals of unresolved social problems.

Partly, this can be attributed to problems of democratic consolidation, and to a longstanding

tradition of strong presidentialism, which poses obstacles to the development of the

civil sphere (Alexander & Tognato, 2018). Scholars have noticed that presidential regimes

exacerbate political polarization and instability (Linz, 1990) and might radicalize protests as

movements can avail of fewer points of access to the state (Kriesi et al., 1995).

PROTEST, THE LEFT AND SOCIAL POLICIES IN 18 LATIN AMERICAN COUNTRIES

In this section, we show trends in contention across the region in the 1990s and 2000s

and present an exploratory analysis of the relationship between protest, the strength of the

Left and the adoption of reforms expanding social protection for previously excluded groups.

We focus on three policies – healthcare, conditional cash transfers and non-contributory

pensions – which have been the object of intensive legislative activity aimed at extending the

coverage of social protection in the 2000s.

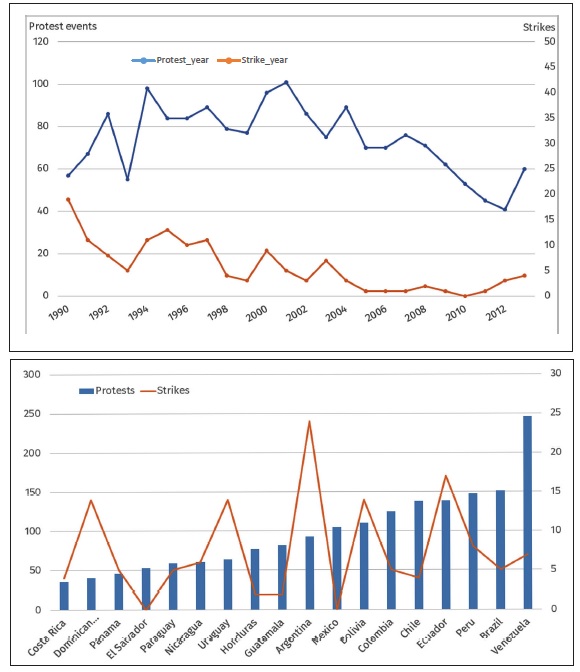

Figure 1 summarizes trends in protests and strikes between 1990 and 2013. We observe

that the number of protests grew all through the decade of the1990s and started to decline

in the second half of the 2000s. The 1990s were probably the most convulsed years, but in

several countries (Venezuela, Brazil, Colombia and Argentina) levels of contentions remained

high across the two decades, while in others such as Chile discontent became apparent only

in the 2000s with the rise of student protests (Guzman-Concha, 2012). The number of strikes

in turn followed a descending trajectory throughout the period. Every peak after 1990 locates

at a lower level than the preceding one. Trade unions in many Latin American countries are

traditionally weak and similarly to other regions their strength has been further declining in

the last decades.

Figure 1. Cumulative frequency of protests and strikes in 18 Latin American countries, 1990-2013

Source: Own elaboration based on Clark and Regan (2019) and Banks and Wilson (2016)

Despite these common trends, not all countries exhibited similar trajectories of social

conflict. As many as 14 per cent of 1,825 total events of protest occurred in Venezuela, which

experienced a very convulsed quarter of century in the aftermath of the Caracazo of 1989.2

According to Lopez-Maya (2003), this “was a turning point in Venezuela’s political history,

producing an irrevocable change in the relationship between state and society, above all

in the way Venezuelans gave expression to their demands and feelings of malaise”. It is

also worth noticing that Chile exhibited rather high levels of protest despite being often

depicted as an exemplar of stability in the region because of sustained economic growth and

its successful transition to democracy (Haggard & Kaufman, 2008). Other countries with a

relatively high frequency of protests are Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia, Mexico. The

lowest levels of contention (below 3 percent) are instead found in countries located in Central

American and the Caribbean (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Dominican Republic and Panama).

As shown in figure 1, countries with a low (or high) frequency of protest do not generally

coincide with those with low (or high) frequency of strikes (correlation=0.04). Comparing the

number of strikes and protests shows that unions have retained a central role as initiators

of large-scale collective mobilization against political authorities in Argentina, Uruguay

and Dominican Republic. The case of Argentina is emblematic of this phenomena. The

country shows a relatively low number of protest but one of the highest number of strikes

in the region. In the second half of the 1990s, community and territorial associations and

organizations of unemployed workers developed close relationships with labour unions

(Niedzwiecki, 2014). Garay (2016) talks about the emergence of social movement unions to

refer to cross-sector alliances between social movements and labour unions which led to

the formation of alternative labour-union confederations. By contrast, in countries such

as Ecuador, Bolivia and Nicaragua, unions have shared centrality with other civil society

organizations, in particular with associations of indigenous people and rural workers.

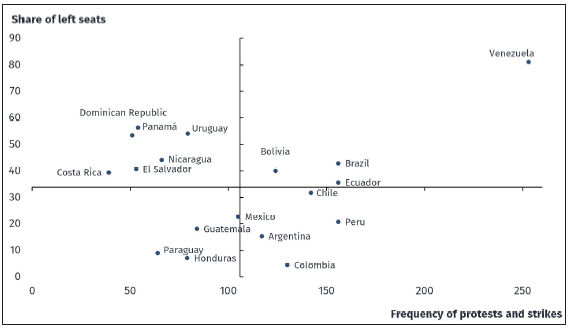

We now turn to the political contexts of protests. The political ideology of governments

has been shown to play an important role in determining their responsiveness to protest

(Ciccia & Guzman-Concha, 2018; Hutter & Vliegenthart, 2016). Figure 2 shows the relationship

between the relative power of the Left and levels of contention in the period of emergence

and consolidation of the left turn in Latin America. We include information on protests and

strikes over a longer period of time (nearly two decades) because the effect of protest on

policymaking is generally cumulative and indirect and dependent on other characteristics

of the political environment. Conversely, strong parliamentary groups can directly initiate

reforms which, if successful, will manifest their effects in the short- to medium- period

depending on political and legislative processes.

Figure 2 shows four main groups. The first pattern is characterized by the presence of

a strong Left and relatively low levels of contention (Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El

Salvador, Nicaragua, Panama and Uruguay). The second group includes countries (Brazil,

Bolivia, Venezuela and Ecuador) with high levels of contention and a strong presence of

the Left in parliament. This group includes some of the most paradigmatic cases of the left

turn in the region. Contention levels were high also in Colombia, Argentina, Peru and Chile

where the Left was relatively weak. Finally, Paraguay, Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico show

relatively low levels of contention and a weak Left in parliament.

Figure 2. Contention (1990-2008) and left-wing seats in parliament (1998-2008)

Source: Own elaboration based on Clark and Regan (2019) and Huber and Stephens (2012)

To explore the relationship between protest, the prevalence of the Left and social policies,

we looked at two sectors: healthcare and social assistance. The data on protest does not

allow to assess direct effects since it does not distinguish events based on the type of issue

raised. However, the cumulative frequency of protests provides indication about the extent

to which contention represented a regular feature of political participation across countries,

and how this affected trajectories of policy reform.

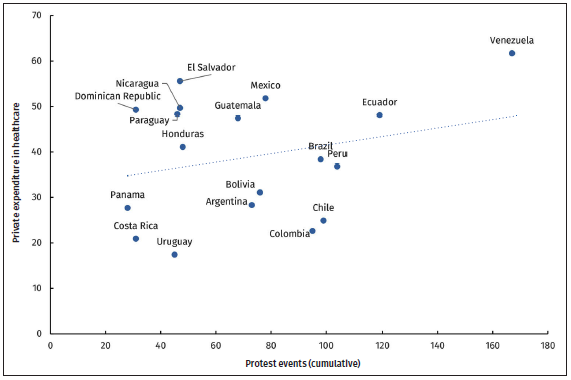

In much of the literature on outsiders in advanced economies, a pessimistic view prevails

on their ability to engage in coordinated action and influence national policies. In the face

of extensive mobilizations in several Latin American countries, it is important to identify

conditions which favours the emergence of such movements. One such condition is the

presence of social programmes that create grievances and provide a common target for

demands across societal sectors (Garay, 2016). Widespread mobilization is more likely to

coalesce around universalistic programmes such as healthcare. Therefore, we first looked

at the relationship between the cumulative frequency of protests and the share of private

health expenditure at the beginning of the period to see if social policy legacies influenced

levels of contention. Out-of-pocket expenditures have traditionally been the most important

source of financing healthcare, suggesting both insufficiency and inequity of provision

(Mesa-Lago, 2008). Figure 3 provides some evidence that several countries with higher levels

of private health expenditure have experienced more frequent protests (r=0.26).

Figure 3. Relationship between share of out-of-pocket expenditure in healthcare

(1998) and frequency of protests in 18 Latin American countries, 1990-2009

Source: Own elaboration based on Clark and Regan (2019) and CEPAL (2019b)

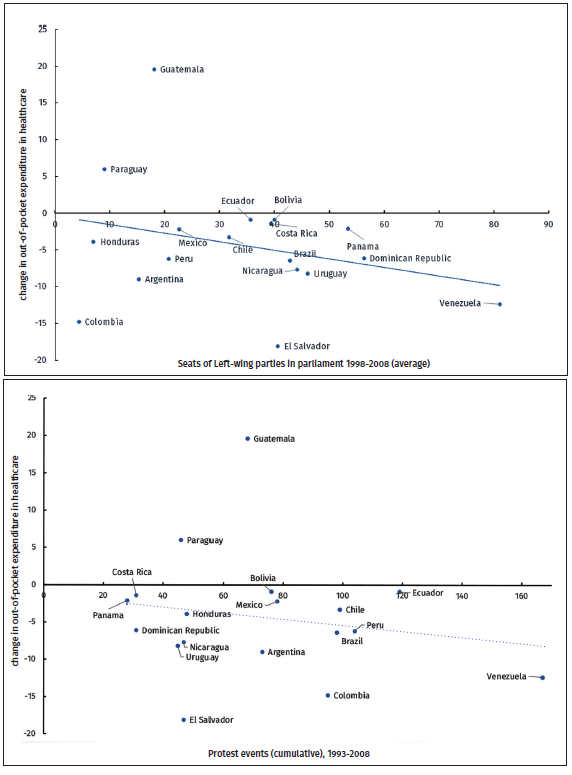

By 2008 sixteen countries had successfully reduced the share of private health expenditure,

and only in Paraguay and Guatemala it had risen (respectively, +6.0 and +19.6 percent). In Costa

Rica the healthcare system already offered universal coverage to all citizens (including illegal

migrants), which explains the small reduction in private expenditure (Franzoni & Sánchez-

Ancochea, 2016). Bivariate analysis suggests that both protest (r= –0.21) and the share of

left-wing parties (r= –0.28) in parliament were positively associated with larger reductions in

private expenditure in healthcare between 1998 and 2008 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Relationship between protests and left-wing seats in parliament and change

in share of out-of- pocket expenditure in healthcare, 2010

Source: Own elaboration based on Clark and Regan (2019) and Huber and Stephens (2012)

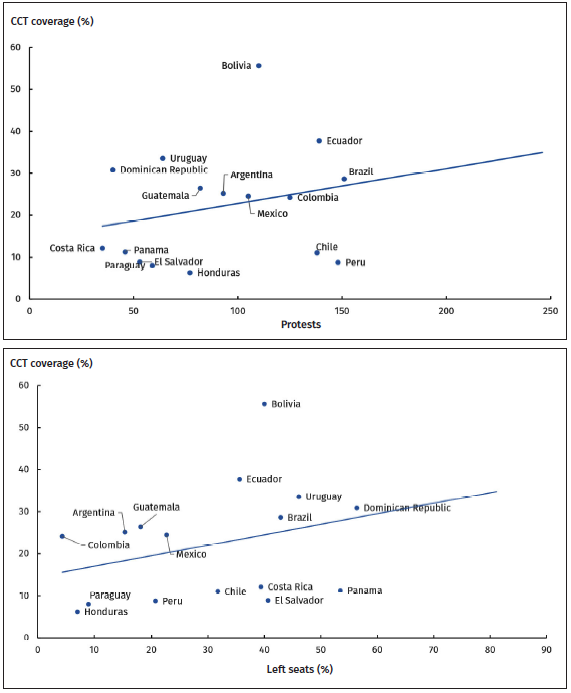

Conditional cash transfers (CCTs) are often considered the centrepiece of the inclusive

turn in Latina American social policies. CCTs combine targeting and human development

goals such as improving children access to education and health. By 2015 there were as

many as 31 such programs in the region covering 20.9 percent of the population (Cecchini

& Atuesta, 2017). Figure 5 shows that the CCTs coverage in 2010 was positively related to

both protest levels and the share of left-wing seats in parliament. Indeed, the correlation

coefficients are similar for both independent variables (0.30), which can be interpreted as

evidence that when protests are more frequent and the left controls parliament, CCTs reach

wider populations.

Figure 5. Relationship between frequency of protests 1990-2009, share of left-wing

eats 1998-2008 and coverage of CCTs, 201

Source: Own elaboration based on Clark and Regan (2019), Cecchini and Atuesta (2017) and Huber and

Stephens (2012)

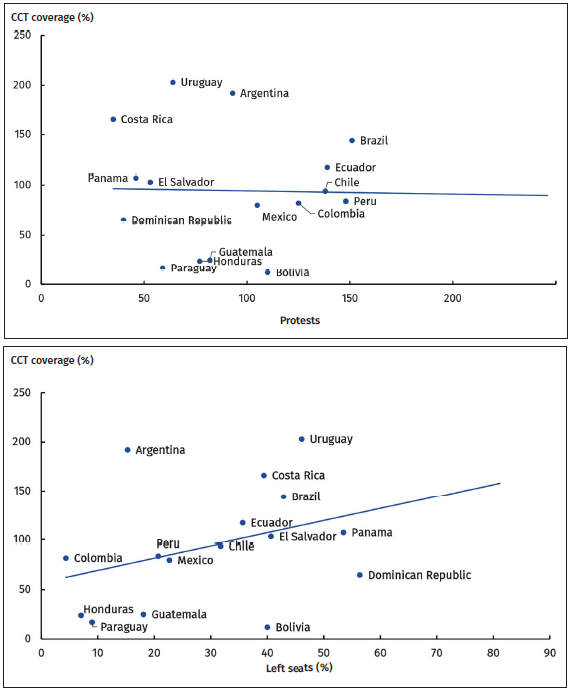

Looking at the levels of benefits (Figure 6), we observed a correlation with the share of

left-wing seats in parliament (0.35) but no relationship with the frequency of protest (-0.01).

This suggests that while protests were influential in shaping the inclusion of a higher number

of social groups (coverage), the electoral strength of the Left was an important condition

determining the generosity of CCTs. However, Uruguay, Costa Rica, Brazil, Ecuador, El Salvador,

Bolivia showed very dissimilar levels of benefit despite a similar share of left-wing seats in

parliament, indicating that further conditions were necessary to produce this outcome.

Figure 6. Relationship between protests 1990-2009 and left-wing seats 1998-2008

in parliament and maximum benefit per capita of CCTs, 2010

Source: Own elaboration based on Clark and Regan (2019), Cecchini and Atuesta (2017) and Huber and

Stephens (2012)

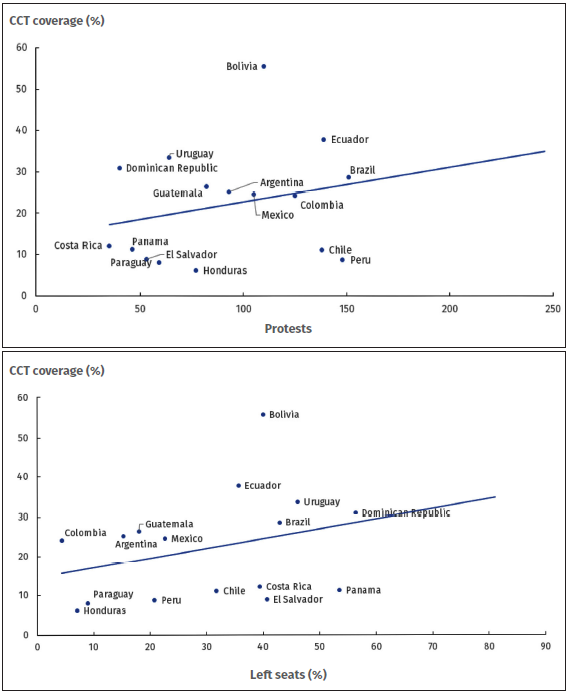

Non-contributory old-age pensions is another area where there has been considerable

policy innovation in the 2000s. Figure 7 shows that both the frequency of protests (r= 0.21)

and the share of left-wing parties in parliament (r= 0.24) had a positive influence on pension

coverage. The more frequent the protests and the higher the share of parliament held by the

left, the larger the increase in coverage. Bolivia stands out here for providing nearly universal

coverage, although other countries with similar levels of protests (Argentina) and presence of

the left in parliament (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Uruguay) presented limited coverage.

Figure 7. Relationship between protest 1990-2009 and left-wing seats 1998-2008

in parliament and coverage of non-contributory pensions, 2010

Source: Own elaboration based on Clark and Regan (2019), Huber and Stephens (2012) and CEPAL (2019a)

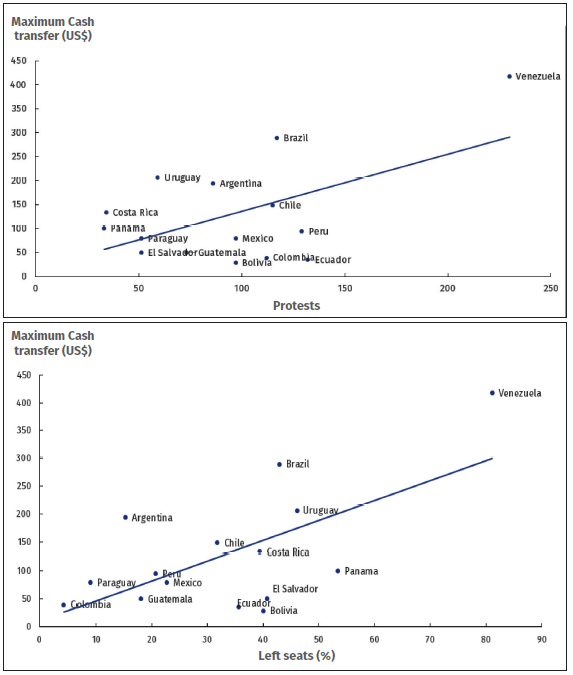

To conclude this analysis, we look at benefit levels of non-contributory old-age pensions

(figure 8). We observe a strong positive relationship between the maximum amount of

benefits and both protest levels (r= 0.55) and the share of left-wing seats in parliament

(r= 0.64). This suggests that the generosity of benefits has been generally higher in countries

where protests have been intense and parliaments exhibited a higher presence of left-wing

politicians.

Figure 8. Relationship between protest and left-wing seats in parliament and

maximum benefit per capita of non-contributory pensions, 2010

Source: Own elaboration based on Clark and Regan (2019), Huber and Stephens (2012) and CEPAL

(2019a)