INTRODUCTION

Corruption is a serious global phenomenon that is widely observed in developed and

developing countries. Surveys show that countries with a democratic socio-economic

structure and institutional arrangements are likely to experience less corruption and

that corruption is predominantly in non-democratic countries and with less controlling

institutions (Doorenspleet, 2019). Thus, the problems of corruption in societies, especially

developing countries, and its impact on the legitimacy and efficiency of political systems

have been the focus of academics and professionals (Barkemeyer et al., 2018; Desta, 2019).

In this regard, some scholars regard corruption as a general disease of the political

community that can destroy the social and cultural-political structure of societies (Terziev

& Petkov, 2017). Others argue that corruption distorts public policy and leads to uneven

allocation of economic resources (Dincer & Gunalp, 2012). According to Transparency

International’s report, corruption is the abuse of public power for personal gain

(Budsaratragoon & Jitmaneeroj, 2020). Corruption refers to “the deliberate neglect or

neglect of a recognized duty, or the unjustified exercise of power, with the motive to gain

advantage” (Ledeneva, 2009).

Jancsics (2014) examined corruption from three views: the first is the micro view

according to which corruption is the result of the rational decisions of individual actors.

This view understands corrupt individuals in the organization as rational actors who

have perpetrated corruption based on their interests (Ashforth et al., 2008; Kish-Gephart

et al., 2010). The second is the macro view which focuses on social norms and structural

arrangements that facilitate corruption. According to the macro view, corruption is a

phenomenon that is embedded in a larger social structure (Nuijten & Anders, 2007). Based

on this approach, people from countries with high levels of corruption tend to be more likely

to break the law (Barr & Serra, 2010; Fisman & Miguel, 2008). The third is the relational view

that examines social interactions and networks between actors in corruption. According

to this view, corruption is the product of the informal exchange network behind the formal

organizational structure (Jaskiewicz et al., 2013; Granovetter, 2007).

Although some scholars believe that corruption acts as the “wheel oil” of development

in developing countries, it appears that the political and social consequences of corruption

- the subject of this study - can be undesirable (Chen et al., 2007). In this regard, many

scholars have pointed to the negative effects of the perception of corruption on political

phenomena, including political distrust and diminished citizen support for ideology and

governing structures (Wang, 2016; Etzioni-Halevy, 2013; Anderson & Tverdova, 2003). But

such research has been less common in Middle Eastern societies.

The significance of the Middle East is that a lot of its countries are first and foremost

oil-leasing ones, and secondly, such economic structures, together with the absence of civil

society institutions, create a more favorable environment for corruption. This seems to have

caused most citizens in the Middle East to have a strong political distrust of the rulers and

structures in their country and to respond occasionally to violent uprisings. Accordingly,

one of the countries where corruption in the Middle East has caused many problems in

different fields is Iraq (Abdullah, 2017; Sawaan, 2012). As reports released by the Corruption

Perceptions Index (CPI) show, Iraq is ranked 168th in the world in 2018with corruption

perceptions score as 18. Based on existing theories it may probably affect citizens’ views of

institutions. And political ideologies will have a negative effect. Importantly, Iraq has many

similarities in terms of economic, historical, and cultural structures with other countries

in the region, making it likely that the findings of this study may be generalizable to other

countries in the Middle East.

This article is organized as follows: In the first section, it examines the theoretical

approach to the study of political corruption perceptions, trust, and ideology of political

Islam. Next, it describes the data and the method used to do the empirical analysis. In the

next step, after presenting and interpreting the results of the tested models, it discusses

the crucial significance of our findings. Finally, it summarizes the results and provides some

questions and suggestions for future research.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Experimental studies show that corruption undermines the legitimacy of the political

system by directly affecting government efficiency, affecting the quality of government,

trust, public support, satisfaction, and ultimately the stability of democracy. Corruption

distorts economic decision-making and processes, poses a threat to trust, and endangers

the legitimacy of the political system (Gray & Kaufman, 1998; Mauro, 1995; Morris & Klesner,

2010; Rothstein & Eek, 2009). Activists see the corrupt system and abuse of power; this

increases the demand for illegal and corrupt practices, so corruption is a threat to trust.

Uslaner (2005) showed that corruption leads to government inefficiencies, tax evasion,

sluggish economic growth, widespread inequality, and political instability.

Some studies indicate that political confidence is declining in the United States and

Western Europe. Similarly, political confidence in emerging democracies has also been

declining in recent decades. The decline in political confidence can indicate a decline in

the health of the political system so that the decline in the health of the political system

as part of the reasons for political cynicism and civil indifference can affect the quality

of global democracy (Putnam, 2000). In this regard, many scholars have addressed the

causes of political distrust. But one of the theoretical explanations in this regard is the

institutional theories that discuss the origin of political trust. Institutional theory, as

opposed to other theories, including cultural theories, views political trust as inward as

a result of institutional functioning. The institutional approach is based on a rational

choice perspective and recognizes that political confidence stems from individuals’ wise

responses to the performance of political institutions. Proponents of this theory emphasize

the importance of government performance and the results of their policymaking. To

increase political confidence, governments must be able to provide good and meaningful

policymaking to the people (Mishler & Rose, 2001).

In this regard, it seems that corruption in three ways can create political distrust in

society. First, current research suggests that government performance can affect political

trust. Studies reveal that the political and economic performance of governments is

the major factor in increasing or decreasing political confidence. Good government

performance leads to higher levels of trust, whereas weak performance leads to lower

levels of trust (Coleman, 1990; Hetherington, 1998; Hudson, 2006). It should be noted, of

course, that people’s assessment of government performance can explain the variance of

political trust, but we should not neglect the role of probity as an influential variable on

political trust.

Several studies show that corruption within governments, and in particular the political

one, can permanently reduce political confidence. The reason is that political corruption

undermines the proper functioning of political institutions. Lee (1994) indicates how

people’s perceptions and thinking can influence their behavior towards politicians and

political trust. If people feel that politicians are incompetent and failing to fulfill their

responsibilities, a negative attitude towards them will develop. Corruption diminishes

confidence in the regime’s ability to respond to citizens’ concerns (Morris & Klesner, 2010). Michael Seligson (2006) examined the cost of corruption in four Latin American countries

by examining the relationship between corruption and the legitimacy of political systems

in these countries and has shown that the spread of corruption reduces the legitimacy of

governments and affects the relationship between people and the level of public trust.

Corruption perceptions harm trust in political institutions, while the experience of

corruption undermines public confidence in national institutions. Also, corruption perceptions

reinforce the lack of trust and lack of trust undermines the government’s efforts to mobilize

society to fight corruption and discredits the promise of fighting corruption. Therefore,

there is a strong interplay between the perception of corruption and trust in political

institutions. Anderson and Tverdova (2003) examined the effect of corruption on people’s

attitudes to the government in 16 democracies and found that people in the countries with

higher levels of corruption rated the performance of the political system more negatively.

La Porta and et al. (2000) argued that corruption impedes state action and diminishes

citizens’ trust in the governments’ ability to address their demands. Corruption both distorts

the public interest and focuses resources and administrative activities on areas where

the peripheral benefits of corruption are greatest. Morris and Kelsner (2010) discovered

a strong reciprocal causality between perceptions of corruption and trust in political

institutions, using American Barometer Survey Political Trust Data and Perception and

Survey of Corruption Experience. They showed that participation in corruption is the only

predictor of lower levels of interpersonal trust. In their findings, when interpersonal trust

is considered as the dependent variable, none of the independent variables (experience

and perception of corruption) predict the interpersonal trust. But there is a negative and

negative relationship between corruption perceptions and political trust.

Moreover, the lack of trust in political institutions may contribute to the emergence of

populist and/or extremist political forces. If citizens identify democracy with incompetence,

injustice, and corruption, they are likely to undermine the value of democracy and may

be inclined to adopt alternative forms of undemocratic government approach (Choi, 2014).

Alesina and Angeletos (2005) argue that when income inequality and injustice are created

by corruption, the poor advocate a redistribution policy that seeks to create inequality

and injustice, and that the rich can support it because they can extract more rent from

subsidy policies. Clientelist systems spread out corruption in society by expanding illegal

political and administrative relations. In these systems, lobbying, bribery, extortion, and

embezzlement are increasing in society. Some political groups that have more political

influence over the government have more opportunities to earn rents, which undermines

democratic values and thus reduces citizens’ trust in the ruling political institutions

(Nelson, 2012; Posada & Walter, 1996).

In addition to the main political issues, there is also a relationship between trust

in political input and economic issues. One of the most well-known arguments is that

the reason people are willing to pay taxes is that they trust the government to provide

services and public goods. Entrepreneurs’ willingness to invest and participate in various

types of economic activity depends partly on their trust in the government for executing

contracts and punishing offenders (Kuokstis, 2012). Kuokstis (2012) examined the financial

performance of Estonia and Lithuania over the years 2007–2008 and found that higher

tax collection efficiency in Estonia was created by high public confidence in government

performance.

The second way is the effect of citizens’ corruption perceptions on their political distrust

through the creation of barriers to democratic culture. Corruption can harm democracies

by undermining the fragile balance between institutions, laws, and norms that provide

the system with trust and legitimacy. Moreno (2002) showed that the permissibility of

corruption- known as the tendency to justify acts of corruption in society- is negatively

correlated with democratic attitudes and political trust.

Choi (2014) indicated that political corruption and political trust affect each other and

they in turn influence citizens’ beliefs about democratic values and processes. Drapalova

(2019) believed that corruption in five ways can affect democracy. According to him,

corruption first infects the democratic electoral system and thus attacks the heart of

democracy. Others also argued that corruption in the form of electoral fraud and votebuying

is one of the most widespread forms of political corruption that some corrupt

political officials try to remain in power in this way (Ziblatt, 2009). Second, corruption can

prevent some people from engaging in political participation by increasing discrimination

against minorities, social classes, and women (Goldberg, 2018). Third, corrupt governments,

especially in contexts of impunity, disregard civil rights, sometimes even humiliating civil

liberties, and thus invade the public sphere and rob citizens of their rights. (Andersen,

2018). Fourth, when citizens are put in a corrupt system, they will feel that they are not

treated equally, and by the law. For this reason, they will resort to bribery, corruption,

or clientelism to gain political influence or gain their rights (Rose & Peiffer, 2015). This

may undermine the spread of corruption and the rule of law in society (Rose-Ackerman &

Palifka, 2016).

Finally, Chayes (2015) argues that corruption undermines the ability of governments

to maintain security for all citizens. The corrupt political and administrative environment

makes it possible for terrorist and religious fundamentalist groups to make the most of this

space to achieve their goals. Thus, all of these factors reduce the public’s confidence in the

democratic system to solve society’s problems. In other words, the spread of corruption in

society initially makes elected governments unable to fulfill their assigned tasks, and this

creates a kind of political culture in people who do not believe in the form of democratic

governance and that distrust. Democracy also causes citizens to have little confidence in

elected governments and political agents (You, 2005).

The third way that people’s perceptions of corruption are influenced by political distrust

comes from subjective and psychological factors. Researchers believe that democracy is

likely to arise when political authorities can build and maintain public trust at the community

level (Goodsell, 2006). Citizens lose confidence in democracy or democratically elected

government when the country’s political and public authorities are corrupted (Seligson,

2002). Surveys in some countries show that they lose trust in civil and public authorities

only in countries where there is a high level of corruption (Anderson & Tverdova, 2003).

Thus, several scholars have examined the political system of countries and concluded

that the type of policymaking of countries is one of the important factors that can

influence political distrust by spreading or reducing corruption. Corruption, especially

political corruption, can cause laws to benefit a certain segment of society, such as elites,

politicians, or specific groups, so that others may incur costs. When this happens, ordinary

citizens may conclude that the likelihood of problems being solved by the government in

society is reduced (Caillier, 2010).

Corruption, therefore, is the cause of collapse because it puts government policies at

odds with the interests of the majority and wastes national resources. Corruption also

diminishes the effectiveness of governments in directing affairs, thereby exacerbating

citizens’ frustration with existing political processes and the country’s future course. In

this way, it weakens national trust in the state apparatus system and confronts it with a

crisis of legitimacy and acceptance.

Hypothesis 1: Government performance (Ha), Disappointment about the future of the

country (Hb), and democratic culture (Hc) mediate the relationship between corruption and

political trust.

Corruption perception reduces trust in the government’s ability to meet the needs of

citizens and decreases public satisfaction with the government (Wang, 2016). World Bank

research shows corruption corrupts public trust and social capital as gradual accumulation

Violation of seemingly small regulations slowly destroys political legitimacy (World Bank,

1997). When a citizen pays a bribe to get a public service or to avoid punishment for violating

the law, there are two types of reactions that may occur depending on how you look at the

bribe. Moreover, bribery may be seen as the cost of operating, just like those who want to

cross a road or use a resort and willingly pay for services, tolls, and fees. Those who pay

these costs may find such payments a legitimate deal and have no negative impact on

their assessment of the legitimacy of the political system. Another group receiving such

bribes may have a completely different reaction, calling it a lucrative and rent-seeking

move. Renting is possible only because the person applying for such rent has both formal

and informal government’s permission to do so. Therefore, it can be predicted that

the experience of these cases of corruption harms one’s view of government (Rabiei &

Normohammadi, 2016).

Thus, there appear to be two types of views on the political implications of the perception

of corruption in society. The first view is a positive and optimistic one. Proponents of this

perspective believe that corruption acts as a kind of “grease the wheels” in developing

societies and that by removing many bureaucratic obstacles, citizens’ support for the

political system will increase (Merton & Merton, 1968). This group of scholars argues that

corruption acts as a tool to connect different parts of society, which is desperately needed

in developing societies (Leys, 1965). Huntington (2006), emphasizing the inefficiency of laws

and institutions in developing countries, regarded corruption as a way of overcoming the

inefficiency of laws and regulations, and referred to it as a positive thing. Becquart (1989)

also argued that corruption in authoritarian countries protects certain areas of freedom on

the one hand. Political corruption redistributes public resources in society through parallel

tools available to previously disadvantaged social groups.

The other tradition in political science focuses mainly on the darker side of corruption

and emphasizes the detrimental effects of corruption on political realms. In this regard,

Etzioni-Halev (2013) and Johnston (1979) argue that corruption in the form of increased trust

between the client and the customer in the community leads to a loss of confidence in the

political system. This results in a decrease in citizens’ support for the existing political

principles and rules in the country. Other studies suggest that corruption is a major cause

of political distrust among citizens, leading to a crisis of legitimacy and a decline in people’s

support for political systems (Booth & Seligson, 2009; Seligson, 2002).

Investigating eight Latin American countries, Booth and Seligson (2009) indicated that

the experience of corruption undermines public confidence in the government, which in

turn reduces public support for the political system. Similarly, using East Asia Barometer

data, Chang and Chu (2006) found that political corruption harms people’s perceptions

of existing political rules in the country by destroying political trust and government

legitimacy. Corruption diminishes the legitimacy and effectiveness of governments as

far as it can put governments and political systems in a serious crisis of legitimacy and

acceptance.

Smith (2010) suggested that perceived corruption is a key factor that negatively mediates

the relationship between distributive justice norms and beliefs about social legitimacy and

ultimately plays an important role in reducing the legitimacy of the social stratification

system. Therefore, perceived corruption can have a major impact on the legitimacy and even

viability of the existing economic system, stratification, and political systems as systems

of justice. Mishler and Rose (2001) argued that when they saw a contradiction between

government practice and political ideology, citizens are more influenced by government performance and their understanding of government performance than by doctrines and

ideologies. That exists. The higher the level of perception of corruption and the weaker the

government performance seems to be, the more supportive of state ideology supporting

political structures will be affected. Hetherington (1998) pointed out that political trust

affects people’s perceptions of the functioning of political institutions. When political

confidence declines, people will have a negative assessment of political institutions as

well as legitimate ideologies. According to Inglehart (1990), political distrust causes one to

reject the existing political system as strongly as possible, and to support extreme right or

left political structures.

Some of the main reasons for the negative impact of the perception of corruption on

people’s support for the prevailing ideology appear to be: Firstly, political and economic

corruption creates cultural corruption so that government officials are not required to

respond to their actions. In corrupt systems the laws that are formulated on paper are

not guaranteed. So what is at stake is not the law, but the acquaintance with individuals

and the bribe, that is, relationships take the place of rules. Therefore, people who do not

have access to high levels of government cannot address their demands to the government

elite (Cerutti et al., 2013). Second, in corrupt systems, legislators adopt policies and

regulations that are not appropriate for politics and economics. These policies benefit

only a few individuals who have close relationships with decision-makers or those who

bribe government officials in favor of legislation that discriminates against other citizens

(Uslaner, 2008). Third, corruption reduces the income of the poorest class of society, as

it destroys private-sector job opportunities and also promotes inequality in society by

limiting public sectors service costs such as access to health care and education (Justesen

& Bjørnskov, 2014). Fourth, to succeed in creating a democratic society, countries need to

create and nurture institutions that promote transparent policymaking. In corrupt systems,

it is difficult to build healthy institutions with a proper structure. Corrupt government

officials responsible for reform do not take measures to deprive them of the benefits of

bribery and accountability. Corruption undermines the legitimacy of government positions

and undermines the democratic process because people are not encouraged to participate

(Sandholtz & Koetzle, 2000). This causes discontent among the middle class in society.

Finally, corruption contributes to political instability as citizens tend to dismiss corrupt

leaders and those who do not defend the public interests (Farzanegan & Witthuhn, 2017).

Thus corruption appears to hurt citizens’ satisfaction with the ruling political structures

and undermine the legitimacy of the political system and ideological structures from the

people’s perspective (Anderson & Tverdova, 2003).

The ideology that governs Iraq seems to be political Islamism. Paragraph 1 of Article 2

of the Constitution of the Republic of Iraq (2005) states: “Islam is the official religion of the

State”. As a result, it is immediately stated in Part A of this Article: “law may be enacted that

contradicts the established provisions of Islam”. This is probably why Ayatollah Sistani and

other religious authorities are easy to comment on and intervene in political matters. Even

in many cases the leadership of political parties and groups in Iraq is the responsibility of

the ayatollahs and religious clerics (Sayej, 2018). Therefore, given that most of the political

structures in Iraq are owned by Islamist political groups or parties close to this ideology,

the second research hypothesis is that:

Hypothesis 2: Perceptions of corruption indirectly diminish citizens’ support for political

Islam in Iraq by increasing political distrust.

METHOD

Data and methods

For the present study, the data collected through the Arab Barometer Wave V EN data

provided during 2018–2019, conducted in collaboration with the universities of Michigan,

Princeton, and other universities and research centers in the MENA region. the Arab

Barometer Wave V EN data includes a survey of attitudinal and behavioral attitudes,

especially in the political, cultural and social spheres, of citizens of Arab countries in wave

V of 12 countries (Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine,

Sudan, Tunisia, and Yemen).

Based on the data extracted from the latest Barometer Arab Data Wave, the present

study surveyed 26,780 citizens of the 12 Arab countries mentioned above, including 24,600

Iraqi citizens.

In the present study, run in AMOS, SEM was used to analyze data and hypotheses.

SEM predicts a set of multiple regression equations by specifying the structural model

used in the statistical program in AMOS software and is, therefore, more accurate for

testing hypotheses than the linear regression used in SPSS. Also, given that the research

hypotheses address the indirect effects of perceptions of corruption on political distrust

and support for political Islamism. So the SEM method can test the hypotheses better than

other methods. However, before testing the structural model of the research, the research

measurement models were examined. In this regard, in some measurement models, items

with a factor load below 0.30 were omitted (Kline, 2015).

Measurement variables and descriptive statistics

Considering the theoretical framework and hypotheses, this paper uses six variables,

the characteristics of which are obtained from the items in the Arab Barometer wave V. In

this regard, the measured variables are:

1. Corruption Perceptions: Corruption perception refers to citizens’ feelings about the

abuse of the public sector and public institutions by the interests of individuals in society

(Olken, 2009). Corruption perceptions were measured by responders’ self-evaluations

according to a 4-point Likert scale. In this regard, two items were used to measure

perceptions of corruption: To what extent do you think that there is corruption within the

national state agencies and institutions in your country? (1= To a large extent, 4= Not at all,

Mean= 1.32; Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.41) [reversed]; (2) How widespread do you

think corruption is in your local/municipal government? (1= Hardly anyone is involved, 4=

Almost everyone is corrupt, Mean= 2.89; Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.41).

2. Poor government performance: One of the preconditions for development in any

society is the good performance of its government and the efficiency of government

institutions. However, sometimes citizens find the quality of service provided by

government institutions inappropriate and inadequate. Five items were used to measure

government performance in which the individual evaluates the current performance of the

government in his country in the following ways: (1) The educational system (1= Completely

satisfied, 4= Completely dissatisfied, Mean= 3.14; Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.44);

(2) The healthcare system (1= Completely satisfied, 4= Completely dissatisfied, Mean= 2.99;

Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.45); (3) Creating employment opportunities (1= Very

good, 4= Very bad, Mean= 3.61; Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.35); (4) Narrowing the

gap between rich and poor (1= Very good, 4= Very bad, Mean= 3.34; Corrected Item-Total

Correlation= 0.34); and (5) Providing security and order (1= Very good, 4= Very bad, Mean=

2.46; Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.32).

3. Wrong direction of the country: For development, countries adopt different policies,

and based on the type of policy, citizens can have positive or negative views on them.

Three items were used to assess people’s views on the correctness or inaccuracy of country

policies. In this regard, the measured items are: (1) In general, do you think that things in Iraq

are going in the right or wrong direction? (1= Going in the right direction, 3= Going in the wrong

direction, Mean= 1.84; Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.27); (2) How would you evaluate

the current economic situation in your country? (1= Very good, 4= Very bad, Mean= 3.11;

Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.31); (3) What do you think will be the economic situation

in your country during the next few years (2-3 years) compared to the current situation? (1=

Much better, 5= Much worse, Mean= 2.77; Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.33).

4. Support for democracy: Some researchers believe that the perception of high

levels of corruption in society can weaken democracy by undermining people’s trust in

their political regime, hence reducing people’s support for democratic political systems

(Seligson, 2006). In this regard, the degree of support for or disapproval of democracy was

measured by 4 items on a 4-point Likert scale, including: (1) Under a democratic system,

the country’s economic performance is weak (1= I strongly agree, 4= I strongly disagree,

Mean= 2.42; Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.52); (2) Democratic regimes are indecisive

and full of problems (1= I strongly agree, 4= I strongly disagree, Mean= 2.42; Corrected Item-

Total Correlation= 0.53); (3) Democratic systems are not effective at maintaining order

and stability (1= I strongly agree, 4= I strongly disagree, Mean= 2.32; Corrected Item-Total

Correlation= 0.55); and (4) Democratic systems may have problems, yet they are better than

other systems (1= I strongly agree, 4= I strongly disagree, Mean= 2.01; Corrected Item-Total

Correlation= 0.21) [reversed].

5. Political distrust: Political distrust refers to a relational attitude that reflects the

perception of distrust of a political system as a whole or its components (Bertsou, 2019). In

this study, political distrust is the lack of trust in political institutions that was measured

via 4 items on a 4-point Likert scale. In this regard, respondents were asked how much

they trust the following institutions: Government (Council of Ministers) (1= A great deal of

trust, 4= No trust at all, Mean= 3.40; Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.63); (2) Courts and

legal system (1= A great deal of trust, 4= No trust at all, Mean= 2.88; Corrected Item-Total

Correlation= 0.50); (3) The elected council of representatives (the parliament) (1= A great

deal of trust, 4= No trust at all, Mean= 3.59; Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.57); and (4)

Local government (1= A great deal of trust, 4= No trust at all, Mean= 3.19; Corrected Item-

Total Correlation= 0.57).

6. Support for political Islam: The term refers to a variety of forms of social and political

activity claiming that public and political life should be guided by Islamic principles

(Akbarzadeh, 2012). Individuals’ acceptance or disapproval of political Islam was measured

via 4 items on a 4-point Likert scale. In this regard, respondents were asked to what

extent they agree or disagree with the following statements: Religious leaders should

not interfere in voters’ decisions in elections (1= I strongly agree, 4= I strongly disagree,

Mean= 1.88; Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.22); (2) Your country is better off if religious

people hold public positions in the state (1= I strongly agree, 4= I strongly disagree, Mean=

2.89; Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.34) [reversed]; (3) Religious practice is a private

matter and should be separated from socio-economic life (1= I strongly agree, 4= I strongly

disagree, Mean= 1.87; Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.28); and (4) Today, religious

leaders are as likely to be corrupt as non-religious leaders (1= I strongly agree, 4= I strongly

disagree, Mean= 1.97; Corrected Item-Total Correlation= 0.26).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations between the variables

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

| 1. Age |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Gender (female) |

.07 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Education |

-.17 |

-.12 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4. Income situation |

-.07 |

-.06 |

.23 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5. Corruption Perceptions |

-.02 |

-.04 |

.10 |

.03 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 6. Poor government

performance |

-.03 |

-.04 |

.16 |

.06 |

.37 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

| 7. wrong direction of country |

0.05 |

-0.05 |

0.10 |

0.02 |

0.30 |

.40 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

| 8. Democracy |

-0.00 |

-0.06 |

0.06 |

0.05 |

-0.09 |

-0.07 |

-0.06 |

1.00 |

|

|

| 9. Political distrust |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.12 |

0.11 |

0.40 |

0.46 |

0.42 |

-0.15 |

1.00 |

|

| 10. Political Islam |

-0.02 |

0.08 |

-0.15 |

-0.00 |

-0.13 |

-0.13 |

-0.09 |

0.03 |

-0.08 |

1.00 |

| Mean |

34.8 |

1.4 |

3.4 |

2.5 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

3.2 |

1.9 |

| Standard deviation |

13.8 |

0.5 |

1.5 |

0.9 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

Notes: bold numbers indicate a significant relationship between scores (p<0.05)

Table 1 provides a breakdown of the preliminary correlations between the study variables.

According to the results, except for age and gender, other variables had a significant

relationship with political distrust. While democracy has had a negative relationship with

political distrust, the relationship between education level, income status, corruption

perceptions, poor government performance, and a negative impression of the country’s

future with positive political distrust was positive. Also shown is the women were more

inclined to political Islamism than men. But the relationship between education levels,

perceptions of corruption, poor government performance, negative perceptions of the

country’s future, and political distrust have been negatively correlated with political

Islamism.

RESULTS

Considering research theories, on the one hand, corruption perception is expected

to directly affect citizens’ assessments of government performance, the direction of the

country, and support for democracy, and on the other hand, existing theories show that the

perception of corruption can, indirectly, reduce the political trust of citizens and lead them

to the ideology of political Islamism. In this regard, the research hypotheses were tested by

Amos graphics, the results of which are reported below.

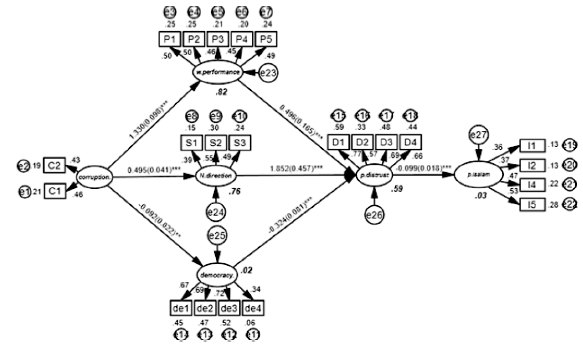

Figure 1 illustrates the empirical model of the research in the form of structural equation

modeling. Regarding the goodness of fit and coefficients of the model, it should be noted

that the research model fits the model well and the data collected support the theoretical

framework of the research: (Model goodness of fit: CMIN / DF = 3.72, RMSEA = 0.033; PCLOSE

= 1.00, CFI = 0.938, GFI = 0.972, AGFI = 0.965, TLI = 0.929, IFI = 0.939, PNFI = 0.799). Also in

this figure, nonstandard path coefficients and standard error represent the strength of the

relationships between the independent and dependent variables in the model. Also, the

above diagram shows that all standard factor loadings are above 0.30 and there is no need

to delete any of the observable variables (Kline, 2015).

Figure 1. Specified SEM shows unstandardized path coefficients with standard errors in

parentheses. Note: This theoretical model was also bootstrapped based on the standard errors

with 1,000 iterations and with a 95 percent confidence interval

Fuente: elaboración propia a partir de los datos del Diseño del III Plan Integral de

Juventud de Andalucía (2018).

Table 2. Direct and indirect standardized effects on dependent variables

| Pe |

Ne |

De |

Di |

Is |

| Direct |

Direct |

Indirect |

Direct |

Indirect |

| Co |

0.903*** |

0.870*** |

-0.136** |

|

0.714*** |

|

-0.130*** |

| Pe |

|

|

|

0.325*** |

|

|

0.325*** |

| Ne |

|

|

|

0.469*** |

|

|

0.469*** |

| De |

|

|

|

-0.097*** |

|

|

0.018** |

| Di |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.182*** |

|

| R2 |

0.82 |

0.76 |

0.02 |

|

0.59 |

|

0.03 |

Notes: *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001. In this study: Co= Corruption Perceptions; Pe= poor government

performance; Ne= wrong direction of the country; De= Democracy; Di= political distrust; and Is=

Political Islam.

Table 3 examines the direct and indirect effects of the research variables. Results of SEM

show that perception of corruption had a positive and significant effect on poor government

performance (β = 0.90, p <0.01) and negative perception of country path (β = -0.13, p <0.01).

The effect of public perception of corruption on the tendency for democracy was significant

among the citizens (β = 0.90, p <0.01) and reduced the democratic tendency among them. Also,

the effect of political distrust on support for political Islamism is negative and significant and

reduces the tendency for political Islamism in citizens (β = -0.18, p <0.01).

As shown in the table above, the indirect effects of the variables were also tested

in this study, and the Sobel test was used to determine the significance of the standard

coefficients. The standard coefficients of the study indicate that citizens ‘general perception of corruption has a significant indirect effect on political mistrust and increases individuals’

political mistrust (β = 0.71, Sobel’s z = 3.23, p <0.01). On the other hand, the indirect effect of

public perceptions of corruption on citizens’ support for political Islam is also significant,

and the results show that public perception of corruption reduces people’s support for

political Islam (β = 0.71, p <0.01). The results also show that the negative perception of the

path of the country indirectly and significantly reduces the support of people for political

Islamism (β = 0.08, Sobel’s z = -3.26, p <0.01). Poor performance by the government is

another variable that has a significant and negative effect on people’s support for political

Islamism (β = 0.05, Sobel’s z = -2.63, p <0.01). Finally, the indirect impact of democracy on

support for political Islamism is significant and positive. There seems to be no conflict

between political Islamism and democracy in Iraq (β = 0.02, Sobel’s z = -3.23, p <0.01).