A COLOMBIAN PARADOX: RIGHT-WING PARTIES AND PROTEST

The recent election of right-wing populist presidents in several Latin American countries

presents a change from left-leaning populist leaderships considered to constitute a “left-wing

block” in the subcontinent. Yet, this trend is not fully generalizable across the subcontinent,

as illustrated by the case of Colombia, which has, since independence, never been governed

by a left-wing government. Not only has the left not been in power in Colombia, but the use of

particular repertoires through which dissent is usually expressed by left-wing organizations,

such as nationwide protests, has remained limited until recently.

The absence of nationwide protests in Colombia relates to the stigma that has portrayed

protests as subversive and criminal (Archila Neira, 2012). Surprisingly, the rise to power of

right-wing populism in 2002 presented a shift in which protests and the support of protest

movements became instrumental to those politicians in power. As right-wing organizations

and populist politicians started to call for and support protests and strikes, the political space

for protests widened. This widening was an unexpected consequence of the instrumental use

of protests by politicians in Colombia.

Protests can take different forms. The forms in which protests manifested in the literature

are referred to as repertoires of contention or as forms of collective action. Following Taylor

& Van Dyke, protests are understood in this paper as “sites of contestation in which bodies,

symbols, identities, practices, and discourses are used to pursue or prevent changes in

institutionalized power relations [in a particular state]” (Taylor & Van Dyke, 2004, p. 268).

Colombia thus presents an interesting counterexample to the regional rise of right-wing

populism within Latin America and in the world more broadly. The arrival of President Iván

Duque (a right-wing politician) to power in 2018 was preceded by the centre-right government

of Juan Manuel Santos (2010–2018) and the right-wing populist government of Álvaro Uribe

(2002–2010). In the years during which several countries in South America elected left-leaning

populist presidents, Colombia consistently remained positioned at the other end of the

political spectrum. Yet, despite this inclination towards the right, the presence and legitimacy

of protests has widened since 2002.

Despite Uribe’s authoritarian style and hostility towards protests that criticized or

opposed his government, he supported protests that buttressed his policies and gave him

political capital. The period between 2010 and 2018 saw a centre-right government in power

that was more open to protest and undertook a peace negotiation with guerrillas. The farright

used protests as a means to oppose the peace negotiations and the peace accords.

Protests supported or called for by politicians from the right helped to consolidate the

legitimacy of protests as a valid repertoire of contestation. Though historically supported by

left-wing political parties, support for protests from right-wing parties has helped shift the

perception of protests and protest movements among conservative segments in the country

and the establishment.

The consolidation of protests as a valid repertoire is also due to protest movements’

persistence in mobilizing citizens, despite the risks faced by protestors (Romero Zúñiga,

2012). The use of non-violent tactics, harnessing of social media, and organizational skills by

protest organizations’ enabled them to take advantage of the small window of opportunity

provided by the Santos government (2010–2018) to consolidate protests as legitimate. Now,

protests are seen as legitimate expressions of discontent: 77% of Colombians were supportive

of protests before the emergence the mass protests which took place since November 2019

(GALLUP, 2019a), and were supported by 74% of the population GALLUP, 2019b). Yet, this

process of the widening of the right to protests has taken place in parallel with attempts

at political closure and the reduction of different actors’ rights. For example, while the use

of protests by the right has contributed to the increased credibility of protests, some of the demands made by these mobilizations are in fact exclusionary, aiming to limit the rights of

different groups in society, illustrated by the threat to the rights of the LGBTI community

posed by some charismatic Christian church protests (Cosoy, 2018).

To discuss these ideas, the article presents a brief history of mobilization and protests

in Colombia, highlighting the limited space for social mobilization in the country between

1948 and 2002 (section two), and then offers an analysis of protests during Uribe’s presidency

(section three). The emergence of social movements in 2010 with the arrival of Santos in

power and the use of protests by populist politicians from both the right and left, leading

to the “normalization” of protests, is discussed in section four. The widening of the right to

protests in Colombia takes place in the age of social media and fake news, as politicians can

more effectively mobilize citizens to pressure governments and change particular policies.

These mobilizations rely on the right to protest, yet have the possibility of constraining

others’ rights and the ability to protest, a tension within democracies.

A HISTORY OF FEAR AND SILENCING: 1948–2002

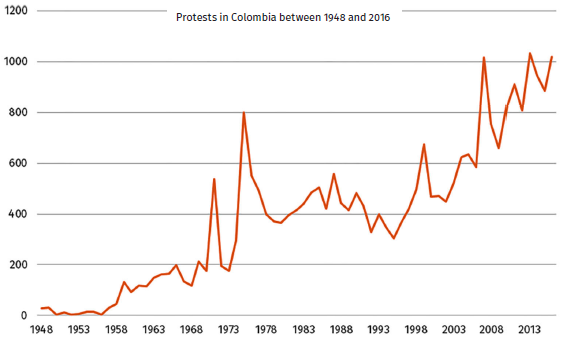

Despite high levels of violence related to the Colombian armed conflict, protests have

consistently taken place in Colombia (see Figure 1). Armed conflict and protests have

coexisted, and have often been assumed to be the same due to the use of “the conflict”

category to describe the political turmoil in Colombia after the civil war began in 1948.

Because of this false assumption, protests have been read by different governments as

the projection of political force by armed organizations, rather than as a political expression

of discontent in a society in which an armed conflict also takes place. Because of this,

Colombian governments have largely ignored the presence of protests, protest movements

and protesting organizations, ignoring the importance of protests in providing feedback to

the political system. The neglect of protests has reinforced the importance of armed conflict

within the politics of the country.

The emergence of armed conflict in Colombia is usually traced to 1948,1 following the

assassination of the populist leader Jorge Eliecer Gaitán. His assassination triggered protests

and riots across the country along party lines that fuelled the already existing violence

between the liberal and conservative parties (Comisión Histórica del Conflicto y sus Víctimas,

2015). The violence that unfolded afterwards involved the use of armed conflict as a modus

operandi by self-defence organizations, liberal guerrillas and regional elites.

In an attempt to stabilize the country, military rule was established between 1953 and

1958. The dictatorial regime led to a reduction in violence, but also limited the space for

protest movements. The end of the dictatorship in 1958 saw a power-sharing agreement

being reached between the liberal and conservative parties: the National Front (“el Frente

nacional”).

The National Front provided political stability between 1958 and 1974, reducing violence

along party lines, but limiting the entrance of new voices beyond the political duopoly

between the conservative and liberal parties (Archila Neira, 1997). The emergence of

new armed groups in Colombia in the three subsequent decades informed a discursive

justification for the limitation of protests. Although the space for protests was limited due

to the emergence of guerrillas and different armed groups, protests increased during these

decades (see Figure 1). The state has met this increase in protests mostly with repression,

particularly between 1978 and 1982, illustrated by civilians being judged in military courts

and the limitation of human rights (Jiménez Jiménez, 2009).

Figure 1. Number of battle-related deaths and protests in Colombia between 1948 and 2016

Source: For the number of protests see Cruz Rodríguez (2017) and Archila Neira (2002).

Despite the frequent use of repression, the space for political participation and protests

has been conditioned also by the possibility of ending armed conflict via peace negotiations.

Yet, despite different peace processes and the demobilization of several armed organizations,

the stigma around protests has remained as armed conflict has continued even after the new

constitution in 1991 recognized the right to protest.

The political openings by new constitutions and peace processes have been limited by

the violent response from armed groups and elites that either were not part of these peace

processes or opposed reforms. These groups have limited the implementation of different

peace agreements.

While armed conflict stifled the emergence of protests, by the end of the 1990s protests

increased again despite an escalation of armed conflict.

The escalating violence made peace a central objective for the government assuming

office in the late 1990s. A failed peace process with the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de

Colombia- Ejército del Pueblo (FARC-EP) took place between 1998 and 2002 as armed conflict

continued. Despite the continuing violence, protests increased during these years as well.

Some of the biggest protests during this time were those against the FARC-EP and other

armed actors between October and November 1999. These protests mobilized millions of

citizens across the country (Rohter, 1999). Protests remained central in the new millennium,

reflecting public discontent following the failed peace process with FARC-EP, the economic

crisis and the escalation of violence in the early 2000s, which preceded the election of a

right-wing populist president to office.

ENTER THE POPULIST RIGHT WING: 2002–2010

The Uribe governments (2002–2006 and 2006–2010) undertook a peace process with

paramilitary groups, remaining adversarial to protests and strikes by social organizations,

while deploying a populist discourse. In several ways, Uribe resembled Alberto Fujimori’s

populist style and rise to power: the use of folk symbols, popular gatherings resembling town

hall meetings, capitalizing on citizens’ distrust of political parties after a decade of violence

and economic crisis.

Uribe’s rise to power illustrates how populism is not only deployed by politicians from the

left in Colombia. Once in power, Uribe used populism as a way to mobilize public support for

his policies when political support from political parties was insufficient. For Uribe, populism

was a tool to leverage his policy proposals.

Although Uribe undertook a peace process with right-wing paramilitaries (Pizarro

Leongómez & Valencia, 2009), peace negotiations did not mean the government accepted

protests or mobilizations for peace. Protests that aimed to pressure the government to

negotiate with left-wing guerrillas, or that demanded the fulfilment of the mandates of the

1991 constitution, were denounced as subversive or illegal. As the government securitized the

state, the space for political dissent was limited (Fierro, 2014).

Several organizations and unions staged protests across the country. Despite the crossfire

between paramilitaries, guerrillas and stigmatization and repression by the government

institutions, organizations took to the streets under different banners (Archila Neira, 2012).

Approximately 643 protests took place annually during Uribe’s first term (see Figure 1) (García

Segura, 2013).

As Uribe initiated his re-election campaign for presidency, a series of protests against

his possible re-election took place across the country. Despite the great number of protests

taking place during his government, the increased perception of security across the country

and support from elites enabled Uribe to be easily re-elected for a second term in 2006.

Uribe continued his security policy and populist style in his second term, ostracizing political

opponents by accusing them of supporting or being linked to armed groups (López de la

Roche, 2014).

Despite the support for Uribe by elites and the nationwide media channels, social

organizations managed to raise their voices. An example of this were the organizations

representing the victims of the conflict, which received wider public attention. They chose to

air their grievances at venues which had been created during the peace process for detailing

accounts of violence perpetrated by paramilitaries; these were leveraged by organizations to

air their grievances and mobilize demands against the state. Other organizations managed to

garner visibility due to the sheer magnitude of their mobilizations, such as in the case of the

marches across the country by indigenous nations to Bogota in 2008 (Virginie, 2010).

The “No más FARC” protests in February 2008 are also of interest. As opposed to other

protests taking place in Colombia, these mobilizations were not denounced as illegal by the

government as they provided the government with political capital. By contrast, protests led

by the victims of paramilitary forces later in the year were not supported by the government,

which accused them of being rallied by the FARC-EP (EL PAÍS, 2008).

When the Colombian Constitutional Court ruled that the second consecutive re-election

being sought by Uribe was against the Colombian Constitution, critics of Uribe and his

government were allowed and given more visibility in mass media, and the space for protests

opened up. Still, the securitization policy of the state was supported by the majority of

Colombian voters, as indicated when Uribe’s then Minister of Defence, Juan Manuel Santos,

was elected president.

THE “NORMALIZATION” OF PROTESTS BETWEEN 2010 AND 2018

When Santos was elected president, it was expected that he would continue Uribe’s vision

of the state. However, Santos differed from Uribe in two ways: Santos is no populist, nor a

right-wing politician. Santos is a darling of the establishment: part of the family that owned

the biggest newspaper in the country, cousin of a former vice president, and family to a

former president. Also, Santos is a centre-right politician. He presented a discourse more

open to protests, officially recognized the existence of an armed conflict in Colombia, and

implemented a series of measures intended to bring justice to victims of the armed conflict.

He also initiated a peace negotiation process with the FARC-EP (Nasi, 2018).

The main differences between the Santos governments and those that preceded them

was their greater openness towards dissent, leading to attempts to moderate the use of

state force against protestors, as well as the political support given by right-wing politicians

to protests. These two factors combined to consolidate an institutional avenue for protests

and dissent in Colombia. The increase in protests between 2010 and 2018 was due to

a number of reasons (Cruz Rodríguez, 2017): the wider political space for protests during

peace negotiations, the efforts of protesting organizations to consolidate their voice and the

contribution of right-wing politicians to the legitimation of protest movements.

Despite the increase in protests during his first government, Santos was re-elected.

Citizens who had protested against Santos on other matters and who still opposed some of

his government policies voted for his re-election in order to support the peace process with

the FARC-EP.

As soon as Santos initiated formal negotiations with the FARC-EP, right-wing politicians

like Uribe gave visibility and political support to protest movements and organizations

opposing either the peace negotiations or the Santos government.2 The opposition aimed

to bolster the opposition to the Santos government and affect his ability to govern, while

offering discursive political support for different protests.

The support from right-wing politicians to protests provided social organizations and

protests across the country support within a different segment of society and helped to

shift perceptions as protests and protestors were legitimized by politicians from the political

right. The peace process was also definitive in enabling the emergence of public voices. As

the peace process between the FARC-EP and the government gained momentum, violence

decreased, and protestors seized the opportunity to air their grievances. The absence of

the armed conflict of the FARC-EP could no longer be used as a straw man to delegitimize

protests and protestors.

Santos’ second term (2014–2018) was met by protests from diverse organizations. Whereas

most of the protests in Colombia could be depicted as belonging to the left and the centre

of the political spectrum, protests by the political right against the Santos administration

and the peace negotiations also took place, illustrating the embrace of protests as a political

tool and the mainstreaming of protests across the political spectre. The protests taking place

during Santos’ second government indicated the lack of legitimacy of the peace negotiation

for a segment of the Colombian population. Due to this, Santos submitted the peace accords

to a plebiscite, aiming to gain political capital to support the peace agreements (Nasi, 2018).

The plebiscite results were negative as 50.2% of voters rejected the peace agreements and

49.7% of voters supported the agreements (Díaz Pabón, 2016). In response to the rejection

of the agreements in the plebiscite, mobilizations in support of the peace agreements took

place across the country. Protests both against and in support of the peace agreements took

place during these years.

Colombia remains a country in which violence is used against representatives of

civic organizations and against actors who propose the widening or the consolidation of

democracy across the country (Díaz Pabón & Jiménez Jiménez, 2018). Despite the continuous

violence, for the first time in Colombian history, protests receive nationwide media coverage

across the political spectre (Osorio Matorel, 2018). However, the rise of right-wing populist

protests and the resilience of armed conflict presents a long-term threat to protests and

protesting organizations.