INTRODUCTION. ‘SECOND POLITICAL INCORPORATIONS’ IN LATIN AMERICA

DURING THE PINK TIDE – AND THEIR CONSEQUENCES

In their classic work, Ruth and David Collier (1991) defined the concept of ‘workingclass

incorporation’ as ‘the first sustained and at least partially successful attempt by the

state to legitimate and shape an institutionalized labor movement’ (p. 783). The ways in

which such incorporation occurred (either through state structures or through mass-party

organisations) produced different and long-lasting effects on the conformation of the

party systems, on party-society relations and on socio-economic models of development.

Federico Rossi (2015; 2018) forcefully argued that Latin American ‘Pink Tide’ can be

functionally interpreted as a ‘second wave of incorporation’ of the popular sectors in the

polity domain after their ‘disincorporation’ and/or exclusion by authoritarian regimes and/

or neoliberal reforms. According to Rossi, in such ‘second wave’, the social actors that acted

as the main representative of those sectors looking for incorporation were territory-based

social movements, instead of function- or class-based trade unions, as it occurred in the

‘first wave’.

The hypothesis animating this research is that the extent to which such actors

provide an encompassing representation of ‘excluded sectors’ is key to understand how

different forms of political incorporation shaped different ‘social blocs’ either supporting

or contrasting progressive political projects in Latin America, and eventually created

the conditions, in the medium term, for the electoral rise of right-wing opponents. This

contribution proposes a comparative analysis of the Bolivian and Argentinean ‘second

incorporations through the movements’, by relying on primary data collected through fiftyfive

in-depth interviews, conducted in March-June 2017 in the four Bolivian major cities - La

Paz, El Alto, Cochabamba, Santa Cruz – as well as Buenos Aires.

Castillo and Barrenechea (2016) define ‘political incorporation’ as ‘a process through

which a previously excluded actor acquires policy benefits and (new forms of) representation

in the state’. Such ‘new forms of political representation’ can take three different forms:

partisan (through a political party), corporatist (‘a form of interest representation in which

organized interests that are officially recognized have direct access to voice or decisionmaking

spaces within the state’, as Castillo and Barrenechea [2016, p. 7] put it) and

personalistic (which stands for ‘non-institutional’ representation of the excluded actor by a

charismatic leader). I rely on such definition for the purposes of this article, with one (major)

difference: I argue that we should refer to excluded sectors, instead of actors. The former

(excluded sectors) are constituencies lacking political representation and thus lacking

political resources to defend their interests, vis-à-vis better-organised constituencies. The

latter (excluded actors) are organisations claiming to represent some excluded sectors and

looking for entering the polity domain. The concrete ability or capacity, by excluded actors,

of positioning themselves as encompassing representatives of excluded sectors depend

on organisational strength, but also on some forms of political recognition (‘from above’)

of their status of ‘legitimated representative’ of those sectors.

This article first discusses how ‘second incorporations’ in Latin America took different

forms, and then analyses, through primary and secondary sources, Bolivian and Argentine

‘second incorporations’, in which social movements played key (albeit different) roles. In

Bolivia, encompassing well-organised movements provided the resources to ‘incorporate’

the peasantry and other constituencies mostly occupied in the informal economy. The

gradual loss of political initiative constrained the movements to play a (still relevant)

role of intermediation between State and society, with some opaque consequences that

reduced governmental support, particularly amongst middle-upper classes and salaried

workers in formal economy. In Argentina, ‘incorporating’ movements were much less encompassing than Bolivian ones, and tended to rely on particularistic arrangements

with Peronist-Kirchnerist political machinery. Such peculiar form of incorporation made

right-wing arguments attacking ‘welfarist’ measures increasingly resonant even amongst

growing segments of the popular sectors, thus benefitting Mauricio Macri’s candidacy in

view of 2015 elections.

VARIETIES OF ‘SECOND INCORPORATIONS’ IN LATIN AMERICA

Roberts (2014) showed how neoliberal reforms during the phase of the Washington

Consensus produced major social turmoil in those countries (such as Argentina, Uruguay,

Brazil, Bolivia and Venezuela) based on a ‘state-centered matrix’ (Filgueira et al., 2012),

as a heritage of the ISI1 phase of development. Roberts showed that where left-of-centre

or labour-based parties (Levitsky, 2003) took the responsibility of implementing marketfriendly

reforms, new ‘populist’ challengers – such as Hugo Chávez, Néstor Kirchner and Evo

Morales, but also Rafael Correa – exploited the window of opportunity opened by severe

economic crises and occupied the political vacuum on the Left. In contrast, in Uruguay

or Brazil – where neoliberal reforms were implemented by conservative actors – existing

social-democratic alternatives strengthened.

In most countries where populist challengers aroused, we observed the emergence of

protest cycles animated by contentious, anti-neoliberal social movements anticipating

changes at the political level (Silva, 2009). Populist challengers developed different kinds

of relationship with such movements, also because of the varying strengths achieved

by the latter in different contexts. In Ecuador, when Correa’s candidacy began attracting

widespread support, indigenous movements, environmental organisations and radical

unions, which for a while had formed a powerful alliance network, were in evident decline,

mainly due to divisions and loss of social support following their support to the unpopular

Gutiérrez government (Van Cott, 2005; Becker, 2013). In Venezuela, social protests against

neoliberal reforms during the nineties appeared extremely fragmented, across sectorial,

territorial and class divides (López Maya, 1999; Levine, 2002; García-Guadilla, 2007). While

Correa’s governmental style has been labelled ‘technocratic’ (Becker, 2013) and increasingly

alienated the support of the movements (De La Torre, 2013), Hugo Chávez notoriously spent

many energies and public resources to create and consolidate his own organised support

amongst Venezuelan popular sectors (Wilpert, 2007; Ellner, 2011). Said this, nor in Ecuador,

nor in Venezuela, autonomous movements played any relevant political or organisational

role within Correa’s and Chávez’s populist projects, at least during their early phase.

Things went much differently in Bolivia and Argentina. Morales’ party MAS-IPSP has

been aptly categorised as a ‘movement-based party’ (Van Cott, 2005; Anria, 2014), a sort of

‘electoral arm’ of three major peasant social movements (the so-called trillizas, ‘triplets’)

and of cocaleros (coca leaf croppers) (Zuazo, 2008). The MAS-IPSP is little more than an

‘electoral brand’ (BO5; BO21), without autonomous organisational structures, which instead

overlap with those of the ‘founding movements’ and with other urban, indigenous or

sectorial organisations that joined the MAS-IPSP throughout the years and that have the

control, at least formally, and with some exceptions, of the candidate selection process

(Anria, 2014). The trillizas, particularly since the nineties, were able to lead and consolidate a

wide alliance network of indigenous, rural and urban movements (Yashar, 2005; Silva, 2009)

that animated a long and successful anti-neoliberal protest-cycle paving the way for the

landslide victory of Evo Morales in the 2005 presidential elections. Despite the relevance

of personalistic incorporation of peasant and indigenous people from Bolivian Highlands,

through the own figure of Morales, partisan and corporatist forms of incorporations were preeminent. Due to the peculiar organisational structure of the MAS-IPSP, such forms

of incorporations were closely intertwined. In addition, and crucially, such a corporatist

incorporation occurred through highly encompassing and deep-rooted social movements

and organisations.

The Argentine contentious cycle instead began mounting in the mid-nineties, when

Menem’s neoliberal reforms provoked severe social and economic negative effects.

Unemployed workers, first in remote Argentine provinces affected by privatisations and

job reduction in the public sector, and then in Buenos Aires Province, made use of extensive

road-blockages (piquetes) to force the state to distribute conditional subsidies (planes).

The piquetero movement evolved as a complex and fragmented constellation of groups,

movements and organisations, located in different neighbourhoods, municipalities and

provinces, and highly heterogeneous in terms of ideological inspirations, spamming from

Trotskyist and revolutionary organisations – often linked to small radical Left parties - to

left-wing Peronist, Catholic, and anti-Peronist centre-Left movements (Pereyra & Svampa,

2003; Boyanovsky, 2010). Piquetero movements dominated Argentine ‘street politics’ under

De La Rúa (1999-2001) and Duhalde (2002-2003) presidencies by showing very high mobilising

capacity and, consequently, strong blackmail potential to force national and provincial

governments to respond through targeted and discretionary social schemes (Rossi, 2015).

In 2002 Néstor Kirchner, backed by Duhalde’s Peronist electoral machine, won the

presidential elections with an extremely weak popular support (22 percent of the voters).

Once in office, Kirchner immediately began building his own social and political base of

support, through a leftist-populist strategy, the so-called Transversalidad (Ostiguy &

Schneider, 2018). He assumed courageous positions against foreign creditors and the

military, pushed for redistributive measures through the governmental support towards

unions’ demands (Etchemendy & Collier, 2007) and gradually ‘freed’ himself from Duhalde’s

political control. Crucially, Kirchner began a sort of ‘selective incorporation’ of the

piquetero’s movement, through the concession of governmental (secondary) positions and

the access to (limited) public resources to those organisations that proved to be pragmatic

enough to dialogue with the Peronist machinery (Rossi, 2015). By doing this, Kirchner steadily

constrained more radical, ideologised or less pragmatic groups to political isolation and,

at the same time, he was able to achieve ‘governability’ through the appeasement of most

piquetero’s movements, which provided both militancy and ‘social peace’. Thus, as I will

further detail below, the ‘political incorporation’ of excluded sectors under Kirchnerism

occurred mostly through corporatist (and particularistic) arrangements with fragmented

and non-encompassing social actors, as well as through partisan representation, nurtured

by the notorious identification of popular sectors with Peronism (Levitsky, 2003; Lupu et

al., 2018).

BOLIVIAN ‘SECOND INCORPORATION’. ENCOMPASSING SOCIAL MOVEMENTS

AND CORPORATIST ARRANGEMENTS

Bolivian trillizas are extremely deep-rooted organizations enrolling hundreds of

thousands of small (and very small, more often than not) landowners throughout the

country (García Linera et al., 2004). This made them perfectly fit for the task of developing

an ‘electoral arm’ that was gradually joined by other social organisations, either territorybased

(such as urban juntas de vecinos) or sectorial-based (such as guilds representing

street vendors, self-employed informal workers, or mineworkers affiliated to cooperatives)

of the hyper-organised Bolivia society (see Figure 1). One could think of the MAS-IPSP as

a movement-based party that was dominated by some ‘core’ organisations (trillizas and

cocaleros) and joined by a constellation of organisations, typically representing self employed workers in the informal economy (Tassi et al., 2012), which obtained the right of

participating in the processes of candidate selection and agenda setting through complex

and informal bargaining with the rest of the actors belonging to the masista coalition.

These ‘non-core’ organisations in some cases acted as veto players within the party and,

since Morales’ victory, within the government (Zegada & Komadina, 2011).

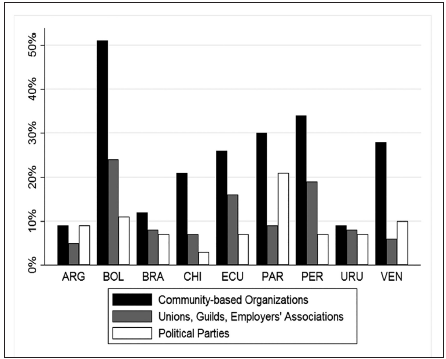

Figure 1. Percentage of citizens declaring to be affiliated to political parties,

trade unions and civic organisations in South American countries

Source: Author’s Elaboration from 2012 LAPOP Survey

To affirm that the MAS-IPSP is a movement-based party does not imply that it is

movement-controlled. The own process of inclusion of organisations other than the trillizas

and the cocaleros diminished the control of the ‘core organisations’ over their ‘instrument’

(García Yapur et al., 2014), while assigning to the party leadership (i.e., to Morales and his

inner circle) a crucial mediatory role between potentially conflicting interests. Until the

end of Morales’ first presidential term (2009), the movements still retained a high capacity

of influencing the political and strategic agenda of the MAS-IPSP in government (BO1;

BO9; BO21), particularly during the complex process leading to the elaboration of the new

Constitution. Nevertheless, some changes in the role of the social movements became

visible since the creation, in 2008, of the CONALCAM (‘National Commission for Change’),

a sort of umbrella group, for mobilising and electoral purposes, of pro-governmental

movements and organisations (Mayorga, 2010): the ‘government of the social movements’

gradually became the ‘government through the social movements’.

As several interviewees put it, after the winning in 2009 general elections, the ‘organic’

movements firmly expected that ‘their turn’ for ‘receiving dividends’ had come (BO5; BO13;

BO20; BO21). The trillizas and the other ‘non-core’ organisations gradually became a sort of

intermediaries between the government of the new Plurinational State and rural and urban

communities to guarantee the access to public resources (mainly in terms of infrastructural

works and productive investments) to the latter, while assuring electoral support to the

former.

In the first Morales’ cabinet (2005), Ministries with a ‘social movement background’ were

69% (10 out of 16). Two years later, this percentage fell to 44%, and, nine years later, to 15%

(Oikonomakis and Espinoza, 2014: 19). Such loss of political influence in strategic decisions

was accompanied by the development of a kind of ‘corporatist’ system, which assured to

the encompassing movements joining the proceso de cambio (each of them representing

quite specific sector- and territory-based constituencies of the complex Bolivian society)

an effective ‘voice’ in the political exchanges internal to the governmental socio-political

coalition. Morales and his government thus began acting as a ‘chamber of compensation’

for the different popular demands coming from the organisations forming part of the

masista coalition. In the words of the leader of the CSCIOB:

‘In the past, who cared about us? To approve a bill, a project, a decree, who dialogued with

us? Nobody. […] The government now goes to hear even the furthest Bolivian community;

it receives many proposals. For instance, yesterday, I had a meeting with the President. I

advanced, political, productive claims. And I am sure that all the social organisations do this.

Through these reunions, the ‘Patriotic Agenda’ was drafted. It is not true that the ‘Patriotic

Agenda’ comes from the government. This is the rhetoric of the Right. They want to divide the

government from us’.

Such system of interest aggregation contributed to define a peculiar political economy

of masista Bolivia. As it has been explicitly theorised by Minister of Economy Arce Catacora

(2015), the public participation in extractive sectors, generating high revenues but little

employment, would provide public resources to be reinvested in social policies (such as

several, and highly popular, conditional cash transfers) and to foster productivity in labourintensive

sectors, in an attempt of ‘formalising’ Bolivian economy. Nevertheless, income

redistribution, infrastructural works and stimulus towards export-oriented agriculture

have been accompanied by the ‘protection’ of informal sectors and the creation of an

‘indigenous bourgeoisie’ with strong influence within the MAS-IPSP (Crabtree & Chaplin,

2013), in detriment of labour-intensive secondary sectors (McNelly, 2019a). Albeit initially

included as ‘full members’ within the masista coalition, indigenous movements have

gradually been either controlled by the government or pushed to the opposition camp,

because of the governmental extractivist agenda (see Paz, 2011; BO1). In a similar vein,

the COB, i.e. the historical Bolivian peak union confederation, traditionally dominated by

salaried mineworkers, has seen its role reduced to subordinated ally, with little influence

on governmental economic strategies, uncapable to recuperate its traditional political

weight – also because of the ongoing diminution of the size of formal salaried sectors -

and prey of (often successful) attempts of co-optation by the government (McNelly, 2019b).

The support of the trillizas to such socioeconomic model of development is well

captured by this extract from my interview with CSUTCB’s leader in 2017:

‘Our goals are freedom and social justice; thus we do not fight for small things […]We do not

care about doble aguinaldo [the compulsory ‘second bonus’ introduced by Morales for formal,

salaried workers], we don’t care about the salary, because the salary could end, a job could

end, a mine could end, but our work will never end. Therefore, our claims, as peasants, have

more to do with productive issues, something that we were not allowed to discuss with the

neoliberal governments. Now we can talk about a lot, a lot, a lot of projects and programmes

related with production, irrigation, roads, genetic improvements that we are discussing now…’

(BO4).

Instead, many interviewees from the COB (BO3; BO12; BO22) and from indigenous and

environmental organisations (BO20; BO25; BO32) precisely contest such evolution that

brought, as negative externalities: conflicts between the state and indigenous movements,

land concentration and benefits for exploitative export-oriented monocultures (and much

less so for microfundistas), little (if any) improvement or defense of workers’ labour rights

to appease foreign investors in industrial sectors (McNelly, 2019b), economic growth concentrated in extractive, financial and construction sectors (and poor ‘trickle-down’

effects on formal labour-intensive sectors, also damaged by competition from ‘informal’

economy: Tassi et al., 2012; BO22; BO27). Furthermore, prebendal tendencies and cooptation

of both rural and urban movements supporting the masista project contributed to alienate

much of the support of urban middle-class that Morales’ governments initially enjoyed

(BO5; BO16). At the same time, social rootedness and high representativeness of Bolivian

peasant movements encapsulated the support for the MAS-IPSP by vast constituencies

(García Yapur et al., 2014) and decisively contributed to impose a new hegemonic discourse,

in which ‘sovereignty’, defense of indigenous people, and social justice became valence

issues in the public political sphere.

Far from being mere speculations, much of these considerations may help to shed

light on the chaotic and still unclear social and political turmoil in the aftermath of the

contested presidential elections of October 2019. Without addressing any debates about

the role of the military and the police, or about the accusations of electoral frauds, it is

a fact that a broad antimasista political and social coalition was created, spamming from

conservative elites to indigenous organisations, with urban middle-class sectors as its

backbone, attacking the MAS-IPSP’s ‘system of power’. Masistas ‘core’ organisations kept

their loyalty towards Morales. Nevertheless, some ‘non-core’ masistas organisations, whose

relationship with the MAS-IPSP had always been much more instrumental, either ‘switched’

to the opposition (such as the cooperativistas mineros) or, while criticising the right-wing

opposition, suggested the ‘exit’ option to Morales (this was the early position of the COB)2.

The defections of groups that had fallen outside the masista system of political exchanges

may have been crucial to determine the (temporary?) defeat of the proceso de cambio.

ARGENTINE ‘SECOND INCORPORATION’. FRAGMENTED SOCIAL MOVEMENTS

AND PARTICULARISTIC NEGOTIATIONS

Kirchner initially appeared to be a weak president in an out-of-control country: despite a

timid economic recovery and the launch, by Duhalde’s presidency, of quite extensive social

schemes to cope with extreme poverty (such as the PJJHD, ‘Unemployed Households Plan’),

social unrest was still erupting. Kirchner’s Transversalidad allowed the new President to

acquire political autonomy from Duhalde and to gradually build a vast social and political

coalition of support. The inclusion of ‘pragmatic’ piqueteros into his coalition, as well as

ongoing economic growth, decisively contributed to reduce social conflict (Rocca Rivarola,

2006; Rossi, 2015)

‘Second incorporation’ in Argentina was pursued through the inclusion of piqueteros

leaders in the so-called ‘Piquetero Cabinet’, linked to the Presidential Secretariat and to

other functionaries belonging to other Ministries, to deal with the piquetero claims in a

conciliatory way (Boyanovsky, 2010; Natalucci, 2011; AR7; AR10; AR13). Kirchner’s strategy

offered to Piqueteros groups an unprecedented opportunity (AR7; AR13) to gain a stable

access to the distribution of funds for the communitarian projects financed by the PJJHD and

by other schemes that Kirchner created later through the Ministry of Social Development

(Rossi, 2015).

However, the amount of funds and planes directly administrated by these organisations

was not particularly high, in order not to irritate the Justicialist Party machine (Boyanovsky,

2010; AR4; AR13). In fact, Argentine ‘second incorporation’ was part of the broader process

of coalition building successfully pursued by Néstor Kirchner during his presidential term. Such coalition included both the (Peronist) main peak union confederation (the CGT, ‘General

Confederation of Work’) and the left-wing union confederation CTA (‘Argentine Workers’

Central’, with strong links to piquetero’s milieu: AR4; AR13). Argentine ‘second incorporation’

was parallel to a sort of a ‘re-incorporation’ of the salaried working-class, through both the

governmental support of the CGT in negotiations vis-à-vis the employers (Etchemendy &

Collier, 2007) and economic policies aiming at state intervention in the market to foster job

creation and the ‘formalisation’ of the productive system (Marticorena, 2014; Kulfas, 2016).

The role of unions, as well as of the ‘formalisation’ of economy to deal with unemployment,

was thus much more central in Kirchnerist Argentina than in masista Bolivia (AR8).

Furthermore, another crucial part of the Kirchnerist coalition (and of the process of ‘second

incorporation’) was the Justicialist Party, which was gradually ‘reconquered’ by Kirchner

(Arzadún, 2013). The high public opinion support enjoyed by the President convinced

several major Peronist figures to gradually abandon Duhalde’s factions (as certified in 2005

legislative elections) and to offer to Kirchner the electoral base that the Peronist machine

continued to assure, thanks to enduring party identification amongst popular sectors (Lupu

et al., 2018) and to its social rootedness, often reproduced by traditional clientelistic forms

(Auyero, 2001; Brusco et al., 2004).

In sum, under Néstor Kirchner’s presidency, we witnessed both the ‘re-incorporation’

of the organised working-class and a ‘second incorporation’ involving, in terms of ‘policy

benefits’, the coexistence of job creation with highly discretionary and particularistic

social schemes that were distributed following political logics and managed by PJ’s local

intermediaries (the punteros: e.g., Auyero 2001; Levitsky, 2003) and piqueteros leaders,

in reciprocal competition. Depicting the relationship between the Kirchnerist state

and piqueteros groups as ‘clientelistic’ would be quite misleading, as it would overlook

the ‘empowering’ dimension of piqueteros’ phenomenon (Garay, 2007; Rossi, 2015; AR7;

AR10; AR12), in contrast to the asymmetrical exchanges between punteros and voters.

Nevertheless, Néstor Kirchner’s ‘second incorporation through the movements’ aimed more

at achieving ‘social peace’ than at assuring electoral support, which was mostly guaranteed

by partisan incorporation of ‘excluded sectors’ and by unemployment reduction through

formal salaried jobs and economic recovery.

Under the presidential terms of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (CFK), the process

of ‘second incorporation’ took different forms. On the one hand, CFK, as a reaction to a

difficult political conjuncture (AR8; Zarazaga, 2012), implemented a truly universalist

(and not discretionary) pro-poor social scheme, the ‘Universal Child Allowances’ (AUH).

Nevertheless, she maintained a sort of ‘division of labour’ between such universal social

scheme and other, targeted programmes to be used discretionarily for political purposes

(Zarazaga, 2012). Crucially, CFK pursued the creation of her own organised base of support –

symbolised by the consolidation of Left-Peronist organisation La Cámpora, widely favoured

in the distribution of governmental charges – instead of relying on the coalition patiently

articulated by her predecessor (Padoan, 2020). By doing so, she alienated the support of

important PJ’s factions and of the CGT, which was, on the contrary, reclaiming much more

political influence within the Peronist-Kirchnerist processes of candidate selection and

policy-making (AR1; AR8).

This evolution led, in view of the 2015 presidential elections, to the rupture between

the Kirchnerist candidate Daniel Scioli and the coalition of Peronist unions and Peronist

dissidents led by Sergio Massa, which resulted decisive for the defeat of Scioli against rightwing

neoliberal Mauricio Macri. Such rupture has been interpreted by Torre (2017), in a way

that perfectly matches the argument of this article, as structurally determined. While the

poorest sectors and the movements’ milieu remained loyal to Kirchnerism, relevant sectors of the salaried working-class – increasingly irritated by social policies schemes following

political logics and targeting ‘underserving’ constituencies – switched their vote towards

Massa’s project. Only in view of the 2019 presidential elections Kirchnerism and Peronism

rejoined their forces in a renewed and successful alliance, bringing the presidential ticket

Alberto Fernández-Cristina Fernández back to the Casa Rosada.