INTRODUCTION

The reconciliation of work with personal and family life is an established

theme in the field of social sciences. Gender differences and the distinct roles played by

women and men in professional and domestic life are among the most covered subjects in

recent literature, with most studies pointing to the persistence of gender disparities, in

which women take on the greatest share of reproductive work (Rashmi &

Kataria, 2022). These differences are largely due to gendered social representations

that attribute responsibilities to men in the public sphere and care and domestic roles to

women (Amâncio, 1994; Monteiro et al., 2015). Likewise,

there has been an increase in the number of articles on family-friendly policies

-particularly studies on the role of mothers-, focusing on the potential of public policies

to either reduce or reinforce inequalities (Li & Zhang, 2023).

In fact, public policies, mainly established at the national level, can

play a major role in determining satisfactory standards of work-life reconciliation and

promoting more egalitarian gender relations, although a change in attitudes, particularly

regarding gender equality, can also take place independently of public policies (Ramos et al., 2019). Therefore, although the relationship between work

and family is significantly influenced by the legal and institutional framework of each life

and work context, the dominant social and cultural norms in each country are a key factor in

understanding the variations in social policies and the way these are perceived at the

individual level (Pfau-Effinger, 2023).

This article presents the results of a quantitative survey of local public

administration employees from the Portuguese region of Cávado, specifically the

intermunicipal community (CIM) of Cávado. The CIM of Cávado is composed of six

municipalities: Amares, Barcelos, Braga, Esposende, Terras de Bouro, and Vila Verde. It is

situated in the northern region of the country, occupying an area of 1246 km2 (INE, 2022), and is a diverse territory, including coastal

municipalities, such as Esposende, and rural mountain municipalities with low population

density, such as Amares or Terras de Bouro, as well as densely populated urban

municipalities, such as Braga (CIM Cávado, 2024). The aim of the CIM is

to create synergies between the different municipalities and to find solutions to shared

problems.

The questionnaire was conceived within the scope of a project aimed at

promoting work-life reconciliation and gender equality through local public policies. The

project began with a diagnosis, in which we carried out the questionnaire survey that

underlies the analysis presented in this article. In addition to indicators on professional

and domestic practices, the survey included questions on gender attitudes, under the

assumption that attitudes towards gender equality have repercussions on the way policies

promoting it are received both by the population at large and within a particular work

organization (Coron, 2020).

In Portugal, female employment patterns display particular qualities

within the European context. The country combines high full-time employment rates for women,

a predominantly dual-earner model based on an “early return to full-time work” (Escobedo & Wall, 2015) and low salaries, with signs of what has come

to be considered a traditional gender culture (Tavora & Rubery,

2013). This traditional gender culture coexists with a strong state orientation

towards the development of public policies promoting equality (Marques et

al., 2021).

On the one hand, the predominance of high female employment and full-time

work, as well as egalitarian legislation, challenge more traditional views of gender. On the

other hand, the entry of women into the labour market was not accompanied by enough care

structures and equipment, or an equivalent entry of men into the domestic and care sphere.

Thus, the strong presence of women in employment, especially those with younger children,

often gives rise to “contradictory and guilt-inducing” attitudes (Ramos et

al., 2019) that hinder defamilization (Perista et al., 2016; Marques et al., 2021).

This is the context on which our research is grounded, together with the

specific features of employment in local public administration. In 2022, the public sector

in Portugal employed 742194 individuals, representing around 15% of total employment -

approximately 75% of public administration workers are employed in central administration,

with the remainder distributed across regional and local administrations (Direção Geral de Administração e Emprego Público [DGAEP], 2023). This

workforce shows a marked aging trend, with a high concentration of employees in older age

groups. Between 2011 and 2022 the number of public administration workers declined across

all age groups under 55, with the most significant decreases in the 25-34 and 35-44 age

groups, representing approximately 11% and 22% of this workforce in 2022, respectively. This

trend is pronounced among local public administration workers - in 2022, 36.2% of local

public administration employees were aged 55 or over, compared to 31.5% in central public

administration (DGAEP, 2023). A strong presence of women is

characteristic of the public employment sector, which - in spite of the changes it has

undergone - offers more favourable working conditions than the private sector, not only in

terms of salaries, but also in terms of working time arrangements and measures to support

work-life balance (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and

Working Conditions [Eurofound], 2020). In Portugal, as well as the work-life

measures that are available to all workers (namely paid and unpaid leaves), public sector

workers are legally entitled to flexible work arrangements and continuous working days,

which may or may not be possible in the private sector. However, public employment is highly

diverse, including occupational disparities that are relevant to understand variations in

attitudes towards reconciliation, especially at local level.

In Portuguese public administration, women represent 61.8% of the total

number of workers (DGAEP, 2023). There are three main occupational

categories in the local public sector and a strong correspondence with specific educational

levels: senior officers (professionals with higher education, such as legal experts,

engineers, economists, HR managers); technical assistants (technical and administrative

occupations, usually with non-tertiary education); and operational assistants (support staff

in areas such as cleaning, gardening or maintenance, with basic educational levels). In

2022, around 55% of public administration workers held higher education degrees, while 27%

and 18% had secondary and basic education, respectively - these distributions differ in

local public administration, where 30.0% held higher education, 31.5% secondary, and 38.5%

basic education (DGAEP, 2023). Women are overrepresented among senior

officers (68.7%) and technical assistants (73.2%). They are also predominant in middle

management positions (56.9%), but most top management positions are still occupied by men

(55.7%). There is also a strong occupational gender segregation in specific sectors: for

instance, men represent 80.3% of local police agents and 95.9% of fire workers (DGAEP, 2023). The sector is therefore subject to logics of labour market

segregation, both horizontal and occupational, as well as vertical (Burchell,

1996; Mora & Ruiz-Castillo, 2004; Monteiro et

al., 2015).

This article begins by presenting the Portuguese context. In the following

sections, we focus on the methodology, results and their discussion. We finish with the main

conclusions and limitations of the study.

Portugal: Between traditionalism and embracing gender equality

Portugal is a particular case with regard to gender equality in the EU

context: while it shares traditional values and representations with some countries from the

south of Europe (particularly, Italy

1

), whether specifically concerning gender or with a consequence for gender equality, it

shares other practices with countries from the north of Europe, such as the widespread

presence of women in the labour market. In Portugal, the female employment rate for women

between the ages of 15 and 64 was 74.0% in 2022, i.e. above the EU-27 average of 69.5% (Eurostat, 2022). Women are more widely represented in the Portuguese

labour market than in other countries from the south of Europe, such as Italy or Greece

(with employment rates for the same year of 56.4% and 61.4%, respectively) and mainly work

full-time, as opposed to countries from the north of Europe. In Portugal, only 7.2% of

employed people work part-time, in contrast with 17.8% of employed people in the European

Union (Eurostat, 2023a).

However, the significant presence of women in the Portuguese labour market

cannot be immediately attributed to more egalitarian gender attitudes, but instead to the

fact that Portugal is also one of the Western European countries where people receive some

of the lowest work-related income, representing a fourth of the income earned in Nordic or

Central European countries (Leão et al., 2024). The need for an income

from work results in maternity not having its usual impact of diminishing the presence of

women in the labour market, although it still influences career progression and exacerbates

inequalities in care work (Leão et al., 2024). Portugal is the European

country where women spend most time (more than four hours a day) on household chores or

childcare, and where the difference between women and men is the greatest (European

Institute for Gender Equality [EIGE], 2022a). The participation of men in household and care

responsibilities is a gender equality dimension that is still found to be lacking, with

care, reproductive and unpaid work being ensured by women through the “second shift” in the

domestic sphere (Blair-Loy et al., 2015; Hochschild &

Machung, 1989). As demonstrated by several studies, Portuguese women combine their

active participation in the labour market with a domestic and care workload, which continues

to be mainly taken on by them (Amâncio & Correia, 2019; Perista et al., 2016; Rodrigues et al., 2015; Wall et al., 2016), with repercussions on women’s mental health and

wellbeing (Guerreiro & Carvalho, 2007).

In terms of values, according to the World Values Survey (2017-2022), and

taking the Inglehart-Welzel world cultural map as reference, Portugal appears close to 0.5

on the axis of survival (with emphasis on economic and physical security) vs.

self-expression values (support for post-materialistic values, including gender equality),

therefore already qualifying for the latter, albeit still somewhat tentatively (Haerpfer et al., 2022). Within the axis that measures traditional

(including traditional family values) vs. secular values (distance from traditional family

values and support for egalitarian gender roles), Portugal continues to appear in the

former, although close to 0.0. Therefore, we seem to be facing a changing society (Torres et al., 2013), which is becoming more open and supportive of

diversity and gender equality, although still situated within traditional values,

characteristic of weaker economies, where families rely more heavily on the state (Haerpfer et al., 2022). This is probably a consequence of the nearly

fifty-year-long dictatorship that promoted different roles for women and men both inside and

outside the family (Wall et al., 2016), and which only came to an end in

1974 with the Carnation Revolution.

When analysing indicators directly linked with gender equality, there are

also signs of more traditional views coexisting with more progressive approaches. According

to data from the Eurobarometer (European Commission, 2017), Portugal and

Sweden have the greatest consensus in EU-28 countries in totally agreeing that the promotion

of gender equality is important to ensure a fair and democratic society (98.0). However,

Portugal is close to the EU-28 average in the gender stereotype index (7.3), scoring 7.2,

while Sweden scores 3.0 (EC, 2017).

Ever since the restoration of democracy in 1974, there has been

significant development at legislation level, as well as progress in public policies

promoting gender equality or affecting gender equality. In the Social Institutions and

Gender Index (Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD],

2023), Portugal gets a score of “very low” for gender discrimination. However, in

the EU’s Gender Equality Index, more anchored in measuring practices than legislation,

Portugal scored 67.4 in the same year, below the EU-27 average of 70.2 (EIGE,

2022b).

Policies to promote gender equality

Although at a less immediate pace than legislation, public policies

promoting gender equality have been developing in Portugal and were initially driven by the

country’s accession to the then European Economic Community in 1986. In 1997, the first

Global Plan for Equality was approved (Resolution of the Council of Ministers 49/97), with

the aim of combating discrimination, promoting equal participation of women and men in the

different spheres of live, and ensuring work-life reconciliation for both men and women.

Successive national plans followed until the launch of the current National Strategy for

Equality and Non-Discrimination 2018-2030 (Resolution of the Council of Ministers 61/2018).

Important policy measures to tackle gender disparities in the family

sphere and in care have also been developed and implemented in the country, namely

recognition of the right to work-life reconciliation for all workers (since 1997);

compulsory parental leave to be used exclusively by the father (since 1999); incentives for

shared parental leave; and the terminology employed, since 2009, determining the use of the

expression “parental leave”, as opposed to “maternity” or “paternity”.

Portugal’s administrative structure is highly centralized, with policies

being determined mostly by the central government. However, concrete efforts have been made

to emphasize the role of municipalities in the promotion of gender equality, namely the

creation of the Municipal Plans for Equality, coordinated by municipal councils. Recently,

the National Strategy for Equality and Non-Discrimination 2018-2030 encouraged widespread

implementation of these in all 308 Portuguese municipalities, as well as the creation of

intermunicipal plans for equality. These plans should include measures to promote gender

equality internally, such as the implementation of flexible working time arrangements, or

incentives to using parental leave, and others aimed at the promotion of gender equality

externally, in areas such as education, health, social services, urban planning, or

environment. However, at the time of our study, none of the municipalities involved in our

research had an equality plan in place.

Methodology

Procedures

To meet the objectives of the study, a questionnaire survey was

conducted with local public administration employees from the Cávado’s CIM in Portugal.

The questionnaire was specifically designed for this study and

included attitude indicators and scales previously validated in the literature. The

pre-test questionnaire was applied during the month of July 2021 to approximately thirty

employees, who formed a diverse sample in terms of gender, age, schooling, professional

category and work department. Once the necessary changes were made, the survey was

conducted between the months of September 2021 and January 2022, both online and in

person, to ensure participation from employees with less access to technology.

All participants were informed of the objectives of the study - the

application of the survey was preceded by information sessions about the project, during

which workers were encouraged to participate. Participation was voluntary, the anonymity

of all employees was ensured, and prior consent was required before answering the

questionnaire.

Sample

The universe of the study consists of 3708 local public administration

employees from the CIM of Cávado. All employees from the six municipalities were invited

to participate in the study by email, letter, or through their direct superiors. A total

of 2375 valid responses were obtained, corresponding to a response rate of 64%. Although

the questionnaire was distributed to the entire population, participation was voluntary

and based on self-selection. Therefore, the sample is considered non-probabilistic, as

no random selection process was applied. Nevertheless, we have obtained a statistically

robust sample which ensures a high degree of statistical representativeness.

Measures

To analyse gender representations among the study population, we used

a variable including 10 statements, in relation to which participants had to express

their agreement or disagreement on a four-point Likert scale, where 1 meant “totally

agree” and 4 “totally disagree”. We gave priority to the use of measures already

validated in international surveys and applied in Portugal (Monteiro et

al., 2015; Wall et al., 2016; Leite et al.,

2016) - International Social Survey Programme (ISSP Research

Group, 1988, 2012); European Social Survey [ESS] (2004); European Values Study [EVS] (1999); we also used a statement of our

own, adapted from a previous study (Saleiro & Sales Oliveira,

2018):

-

When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job

than women (ESS, 2004)

-

A husband’s job is to earn money. A wife’s job is to look

after the home and family (ISSP Research Group, 1988, 2012)

-

It’s better to have a man as your boss than a woman (Leite et al., 2016; Monteiro et al.,

2015)

-

All in all, family life suffers when the woman has a

full-time job (ISSP Research Group, 1988, 2012; Monteiro et al., 2015)

-

In the organization where I work, there are jobs that

should be done only by men and others only by women (Leite et

al., 2016; Monteiro et al., 2015)

-

In a couple, the man and woman should share the household

chores equally (ISSP Research Group, 2012; Wall et al., 2016)

-

The father is just as capable as the mother of looking

after a baby under the age of one (ISSP Research Group,

1998, 2012; EVS, 1999)

-

Children suffer when fathers are not involved in childcare

(ISSP Research Group, 2012; Wall et al.,

2016)

-

Women already have the same opportunities as men in

professional life (Leite et al., 2016)

-

Inequality between men and women is a thing of the past

(Saleiro & Sales Oliveira, 2018)

Considering the strong social desirability pressure of the topic, and

the likelihood of respondents showing socially acceptable behaviour, the original scales

were adapted to four-point measures to avoid misuse of the midpoint and to force a

choice (Chyung et al., 2017). Data analysis included an initial

exploratory review (distributions and missing values), descriptive comparisons of

agreement levels by gender, and a principal component analysis (PCA with varimax

rotation) to reduce dimensionality and identify components underlying gender attitudes.

These components were tested for internal consistency and used in bivariate analysis

(t-test and one-way ANOVA), conducted separately for women and men, to assess

differences by age, education, geographic area, and parenthood. The results were

significant at 0.05. Data was analysed with the SPSS (Statistical Package for Social

Sciences, IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.0).

Results

Description of the sample

Table 1 presents the main sociodemographic characteristics of the

sample by gender. In line with the gender distribution in Portuguese public

administration, the sample is mainly composed of women (62.7%). Ages range between 20

and 69 and the average age is approximately 48 (SD=9.6). The most represented age group

is 45-54-year-olds (36.9%), followed by 35-44-year-olds (24.0%). Just as with the

current age distribution in Portuguese public administration, where there is a

pronounced ageing trend (DGAEP, 2023), older employees are more represented than younger

ones. Men are more represented in the 55 and over age group, which is a legacy of the

more recent massive entry of women into the formal labour market in Portugal.

Most of the respondents completed secondary education (International

Standard Classification of Education, ISCED 3) (40.3%), and the percentage of those with

higher education (31.1%) is virtually the same as those who only completed basic

education (ISCED 2) (28.6%). The large proportion of less qualified workers reflects not

only the levels of formal schooling in the country, where most of the population has

received less education (Eurostat, 2023b), but also in municipal

public administration, where, as previously mentioned, the percentage of workers with

higher education still falls short of that in central public administration (DGAEP,

2023). However, as a recent trend in Portuguese society, women are more qualified than

men and are more represented in secondary education (45.3% of women and 32.0% of men)

and in higher education (32.4% and 28.9% respectively). Men are still significantly more

represented in primary education (39.1% of men and 22.3% of women).

The majority of workers are concentrated in urban areas, which are

more densely populated, and most of them are women. Regarding parenthood, most

respondents have children (80.2%), although more women than men have children.

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of female and male workers

|

|

n |

% |

Women

|

Men |

| Gender

2

|

Women |

1488 |

62.7 |

| Men |

886 |

37.3 |

| Total |

2374 |

100.0 |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| Age |

≤ 34 |

202 |

9.8 |

133 |

10.0 |

69 |

9.5 |

| 35 - 44 |

493 |

24.0 |

322 |

24.2 |

170 |

23.5 |

| 45 - 54 |

757 |

36.9 |

511 |

38.4 |

246 |

34.0 |

| 55 - 59 |

322 |

15.7 |

201 |

15.1 |

121 |

16.7 |

| ≥ 60 |

280 |

13.6 |

162 |

12.2 |

118 |

16.3 |

| Total |

2054 |

100.0 |

1329 |

100.0 |

724 |

100.0 |

| Education |

Basic |

673 |

28.6 |

330 |

22.3 |

342 |

39.1 |

| Secondary

|

950 |

40.3 |

670 |

45.3 |

280 |

32.0 |

| Tertiary

|

733 |

31.1 |

480 |

32.4 |

253 |

28.9 |

| Total |

2356 |

100.0 |

1480 |

100.0 |

875 |

100.0 |

| Geographical area |

Urban |

1821 |

77.2 |

1169 |

79.2 |

652 |

73.9 |

| Rural |

538 |

22.8 |

307 |

20.8 |

230 |

26.1 |

| Total |

2359 |

100.0 |

1476 |

100.0 |

882 |

100.0 |

| Children |

Yes |

1888 |

80.2 |

711 |

47.8 |

391 |

44.1 |

| No |

467 |

19.8 |

777 |

52.2 |

495 |

55.9 |

| Total |

2355 |

100.0 |

1488 |

100.0 |

886 |

100.0 |

Attitudes towards gender roles

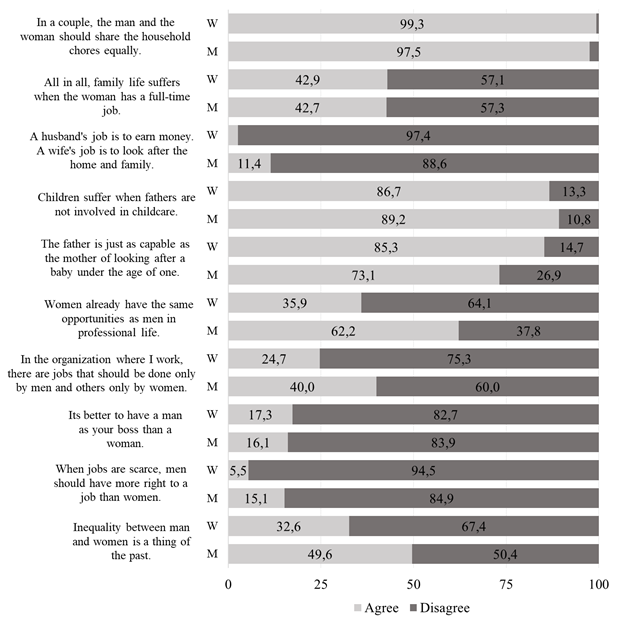

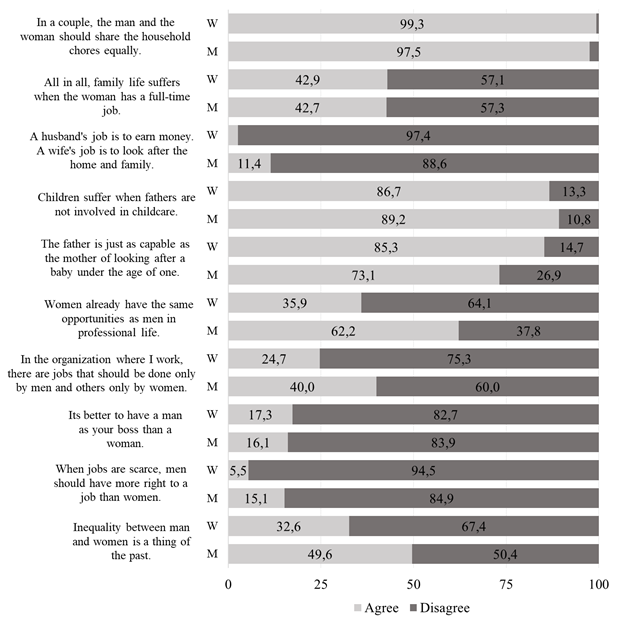

Considering each of the statements individually and merging the

totally agreement/totally disagreement and the agreement/disagreement levels, results

show tendentially egalitarian gender attitudes, although these are more evident in the

group of women (Figure 1).

The statement that points towards a stereotyped view of gender roles,

where men are expected to be the economic providers of the family and women are expected

to care for the home and family, has the highest levels of disagreement. For women, this

disagreement is almost consensual, while for men, 11.4% still agree with the statement.

The statement with the highest level of agreement is that which indicates the need for

an equal division of household chores between women and men, with the highest level of

consensus both for men and for women.

Figure 1 Attitudes of female workers and male workers towards gender equality

(%)

Source: Questionnaire survey "Equality and reconciliation of personal,

family and professional life" in the NUTSIII Cávado (2021/22). Own elaboration.

To reduce multidimensionality and increase the interpretability of

data, a principal component analysis (PCA) with orthogonal rotation (varimax) was

conducted. The adequacy of the data for PCA was confirmed by the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin

test, with a score of 0.768 - above the usually considered acceptable 0.6 (Reis, 2001) -, and by the Bartlett’s test of sphericity, which was

significant (X

2

(45)=3460.292, p<0.05). The analysis of eigenvalues indicates that

three factors meet the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalue>1) and explain 54.7% of the total

variance. The scree plot also showed inflections retaining three factors. Based on these

statistical results and existing literature, three principal components were retained

(Table 2).

Component 1 - gender attitudes in the work-family interface -

includes statements that point towards stereotyped gender views concerning the role that

women and men should play in employment, in organizations and in the family, and

specifically, in the way of reconciling work and family. Component 2 - gender

attitudes in housework and care - includes statements referring to egalitarian

social representations in terms of the division of household and care responsibilities

between women and men. Component 3 - perceptions of the evolution of gender

equality - includes views on gender equality at a global level, indicating

attitudes of gender blindness or gender (un)awareness. Among the three, component 2 is

associated with the most egalitarian attitudes, followed by component 1, and then

component 3.

Based on these components, we created composite variables by

calculating the mean of employees’ responses to the items with the highest loadings in

each dimension. For component 2, item scores were reversed to ensure that higher values

consistently correspond to more egalitarian attitudes (i.e. 4 = highest level of

agreement).

To assess the internal consistency of each component, we calculated

Cronbach’s alpha, the Spearman-Brown coefficient, and the average of inter-item

correlations. Component 1 proved to have adequate consistency [α = 0.699; average of

inter-item correlations = 0.47, i.e. within the 0.15-0.50 range recommended by Clark and Watson (1995)]. Component 2 presented a lower alpha (α =

0.500); although values below 0.6 are usually considered to reflect poor reliability,

they are not necessarily unacceptable - particularly in exploratory research or when

components include a small number of items, as is the case here (George

& Mallery, 2003). Moreover, the average inter-item correlation for this

factor was 0.51, suggesting a strong internal relationship between the items. Component

3 obtained an alpha of 0.618 and an inter-item correlation of 0.45, which is considered

acceptable within the context of exploratory analyses.

Table 2 Gender attitudes. PCA with varimax rotation

| |

Principal components

|

| Variables

|

Gender

attitudes in the work-family interface |

Gender

attitudes in housework and care |

Perceptions

of the evolution of gender equality |

| When jobs

are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women. |

0.736 |

-0.211 |

0.251 |

| A husband’s

job is to earn money. A wife’s job is to look after the home and family.

|

0.695 |

-0.224 |

0.197 |

| It's better

to have a man as your boss than a woman. |

0.690 |

-0.044 |

0.045 |

| All in all,

family life suffers when the woman has a full-time job. |

0.622 |

0.042 |

-0.109 |

| In the

organization where I work, there are jobs that should be done only by

men and others only by women. |

0.580 |

-0.076 |

0.172 |

| In a couple,

the man and woman should share the household chores equally. |

-0.145 |

0.730 |

-0.077 |

| The father

is just as capable as the mother of looking after a baby under the age

of one. |

-0.207 |

0.691 |

0.147 |

| Children

suffer when fathers are not involved in childcare. |

0.055 |

0.685 |

-0.168 |

| Women

already have the same opportunities as men in professional life. |

0.069 |

-0.050 |

0.848 |

| Inequality

between men and women is a thing of the past. |

0.205 |

-0.044 |

0.791 |

| % variance

explained |

23.4 |

15.9 |

15.5 |

| α (average

inter-item correlation) |

0.699(0.47)

|

0.500(0.51)

|

0.618(0.45)

|

Subsequently, and to understand to what extent the independent

variables of the study explain the existence of significant differences in each of the

components, we conducted several bivariate analyses, performing t-tests for the

differences between means and analyses of variance (one-way ANOVA), in two subsamples:

women and men.

Gender attitudes in the work-family interface

Table 3 shows the results of the statistical tests carried out for the

first dimension, where higher mean scores reflect more egalitarian gender attitudes.

Overall, workers tend to reveal egalitarian social representations regarding gender

division in employment (M=3.12, SD=0.526).

Table 3 Gender attitudes of female workers and male workers regarding

employment

| |

|

Mean |

SD |

Statistic

|

Mean

Difference |

| Gender |

Women |

3.175 |

0.467 |

t(1303.376)=6.210***

|

|

| Men |

3.018 |

0.602 |

|

|

|

Women

|

| Age |

≤ 34 |

3.515 |

0.388 |

F(4.1198)=24.016***

|

≤ 34 ≠

35-44*** |

| 35 - 44 |

3.240 |

0.427 |

|

≤ 34 ≠

45-45*** |

| 45 - 54 |

3.184 |

0.441 |

|

≤ 34 ≠

55-59*** |

| 55 - 59 |

3.105 |

0.453 |

|

≤ 34 ≠ 60 or

more *** |

| ≥ 60 |

3.020 |

0.509 |

|

55-59 ≠

35-44* |

| |

|

|

|

≥ 60 ≠

35-44*** |

| |

|

|

|

≥ 60 ≠

45-54*** |

| Education |

Basic |

2.947 |

0.474 |

F(2.1309)=94.273***

|

Basic ≠

Secondary** |

| Secondary

|

3.122 |

0.427 |

|

Basic ≠

Secondary*** |

| Tertiary

|

3.387 |

0.425 |

|

Secondary ≠

Tertiary*** |

| Geographical area |

Urban |

3.175 |

0.470 |

t(1304)=0.424

|

|

| Rural |

3.162 |

0.456 |

|

|

| Children |

Yes |

3.130 |

0.461 |

t(1308)=-7.350***

|

|

| No |

3.363 |

0.449 |

|

|

|

Men

|

| Age |

≤ 34 |

3.232 |

0.698 |

F(4.658)=14.639***

|

55-59 ≠ ≤

34* |

| 35 - 44 |

3.246 |

0.524 |

|

55-59

≠35-44*** |

| 45 - 54 |

3.093 |

0.535 |

|

≥ 60 ≠ ≤

34*** |

| 55 - 59 |

2.918 |

0.553 |

|

≥ 60 ≠

35-44*** |

| ≥ 60 |

2.773 |

0.582 |

|

≥ 60 ≠

45-54*** |

| Education |

Basic |

2.708 |

0.597 |

F(2.758)=102.675***

|

Basic ≠

Secondary*** |

| Secondary

|

3.032 |

0.488 |

|

Basic ≠

Tertiary*** |

| Tertiary

|

3.389 |

0.497 |

|

Secondary ≠

Tertiary*** |

| Geographical area |

Urban |

3.079 |

0.586 |

t(760)=5.228***

|

|

| Rural |

2.819 |

0.607 |

|

|

| Children |

Yes |

2.985 |

0.591 |

t(759)=-3.049**

|

|

| No |

3.148 |

0.630 |

|

|

| *p<0.05

**p<0.01 ***p<0.001 |

The analysis shows significant differences between men and women,

indicating that, on average, women (M=3.175, SD=0.467) hold more egalitarian

attitudes than men (M=3.018, SD=0.602) concerning gender attitudes in the

work-family interface [t(1303.376) = 6.210, p = 0.000].

There are also significant differences in terms of age groups for

women [F(4.1198) = 24.016, p = 0.000] and for men [F(4.658) =

14.639, p = 0.000]. In the sub-sample of women, younger individuals (until the

age of 34) present the most egalitarian social representations (M=3.515,

SD=0.388), whereas older ones present the least egalitarian views (M=3.020,

SD=0.509). As we progress along the age groups, mean scores decrease. Significant

differences were found between the group of younger workers and all the other age

groups, as well as between the older age groups (55-59 years old and 60 or older) and

the groups immediately preceding them (35-44 years old and 45-54 years old). However, in

the sub-sample of men, workers aged 35-44 years show relatively more egalitarian

attitudes (M=3.246, SD=0.524) than the youngest ones (M=3.232, SD=0.698).

Significant differences were found between the oldest age group and the three age

categories immediately preceding, and between those aged 55-59 years and the two

youngest age groups.

The level of schooling also influences individuals’ gender attitudes

for both women and men [F(2.1309) = 94.273, p = 0.000 and F(2.758)

= 102.675, p = 0.000, respectively], as significant differences were found

between all educational levels under analysis. As the level of schooling increases,

workers tend to reveal more egalitarian social representations, on average. Workers who

only completed basic education present less egalitarian attitudes than those who

completed secondary education or higher education, on average. The latter are those with

the most egalitarian social representations, both in the sub-sample of women and of men,

although women show higher levels of egalitarian views than men in all three educational

categories.

The geographic area impacted significantly the attitudes of men

(t(760) = 5.228), with those working in urban areas showing more egalitarian

attitudes (M=3.079, SD=0.586) but showed no significant impact in the group of

women.

Finally, parenthood appears to be related to less egalitarian

attitudes, as individuals without children showed more egalitarian views than those with

children, both in the subsample of women [t(1308) = -7.350, p = 0.000],

and of men’s [t(759) = -3.049, p = 0.000]. The difference between having

or not children is greater for men. Men with children show less egalitarian views

(M=2.985, SD=0.591) than women with children (M=3.130, SD=0.461), and

women without children present more egalitarian views (M=3.363, SD=0.449) than

men without children (M=3.148, SD=0.630).

Gender attitudes in housework and care

Just as in component 1, the results show significant effects between

women and men [t(1446.585) = 4.981, p = 0.000] in the component that

measures representations regarding household and care responsibilities, with women

revealing more egalitarian attitudes (M=3.380, SD=0.459) than men

(M=3.267, SD=0.526) (see Table 4).

Age also proved to be a statistically significant variable, both in

the case of women [F(4.1197) = 14.745, p = 0.000], and of men

[F(4.663) = 10.611, p = 0,000]. Overall, younger women show more

egalitarian attitudes than older women, especially in the lower age groups (until the

age of 34) (M=3.648, SD=0.402) which has a statistically significant difference

from all the others, and the group immediately after it - 35-44 years old

(M=3.416, SD=0.446), which is also significantly different from the oldest age

group, 60 and over (M=3.249, SD=0.502). The youngest men (M=3.385,

SD=0.534), on the other hand, only differ significantly from the oldest ones

(M=3.052, SD=0.521), with no significant differences from the 55-59 age group

(M=3.220, SD=0.476). The second youngest age group of men, 35-44 years old

(M=3.449, SD=0.478), in turn, differs significantly from the 55-59 age group

(M=3.220, SD=0.476).

Education also has a significant effect on the representations of

women [F(2.1314) = 23.308, p = 0.000] and men [F(2.765) = 35.528,

p = 0.000] regarding attitudes towards domestic chores and caring. Both women

(M=3.495, SD=0.465) and men (M=3.458, SD=0.492) with higher education have

more egalitarian attitudes than women and men with lower degrees, respectively. The

difference lies in the fact that in the groups of men there is also a statistically

significant difference between those with secondary education (M=3.303, SD=0.498)

and those with only basic education (M=3.086, SD=0.521).

Just as in the previous component, the geographic area impacted

significantly the attitudes of men [t(767) = 5.129, p = 0,000], with those

working in urban areas showing more egalitarian attitudes (M=3.321, SD=0.515) but

showed no significant impact in the group of women.

Finally, parenthood appears to be related to less egalitarian

attitudes for women [t(1313) = -4.245, p = 0.000], as women without

children (M=3.489, SD=0.466) showed more egalitarian views than those with

children (M=3.355, SD=0.454). However, in the sub-sample of men, this variable

showed no significant effect on this component.

Table 4 Gender attitudes of female workers and male workers regarding the

division of household and care responsibilities

| |

|

Mean |

SD |

Statistic

|

Mean

Difference |

| Gender |

Women |

3.380 |

0.459 |

t(1446.585)=4.981***

|

|

| Men |

3.267 |

0.526 |

|

|

|

Women

|

| Age |

≤ 34 |

3.648 |

0.402 |

F(4.1197)=14.745***

|

≤ 34 ≠

35-44*** |

| 35 - 44 |

3.416 |

0.446 |

|

≤ 34 ≠

45-45*** |

| 45 - 54 |

3.363 |

0.455 |

|

≤ 34 ≠

55-59*** |

| 55 - 59 |

3.335 |

0.438 |

|

≤ 34 ≠ ≥

60*** |

| ≥ 60 |

3.249 |

0.502 |

|

35-44 ≠ ≥

60* |

| Education |

Basic |

3.282 |

0.449 |

F(2.1314)=23.308***

|

Tertiary ≠

Basic*** |

| Secondary

|

3.339 |

0.443 |

|

Tertiary ≠

Secondary*** |

| Tertiary

|

3.495 |

0.465 |

|

|

| Geographical area |

Urban |

3.385 |

0.461 |

t(1307)=1.110

|

|

| Rural |

3.351 |

0.455 |

|

|

| Children |

Yes |

3.355 |

0.454 |

t(1313)=-4.245***

|

|

| No |

3.489 |

0.466 |

|

|

|

Men

|

| Age |

≤ 34 |

3.385 |

0.534 |

F(4.663)=10.611***

|

≥ 60 ≠ ≤

34** |

| 35 - 44 |

3.449 |

0.478 |

|

≥ 60 ≠

35-44*** |

| 45 - 54 |

3.295 |

0.535 |

|

≥ 60 ≠

45-54** |

| 55 - 59 |

3.220 |

0.476 |

|

55-59

≠35-44* |

| ≥ 60 |

3.052 |

0.521 |

|

|

| Education |

Basic |

3.086 |

0.521 |

F(2.765)=35.528***

|

Basic ≠

Secondary*** |

| Secondary

|

3.303 |

0.498 |

|

Basic ≠

Tertiary*** |

| Tertiary

|

3.458 |

0.492 |

|

Secondary ≠

Tertirary** |

| Geographical area |

Urban |

3.321 |

0.515 |

t(767)=5.129***

|

|

| Rural |

3.097 |

0.526 |

|

|

| Children |

Yes |

3.268 |

0.514 |

t(764)=-0.364

|

|

| No |

3.285 |

0.567 |

|

|

| *p<0.05

**p<0.01 ***p<0.001 |

Perceptions of the evolution of gender equality

In component 3, significant differences could be noticed according to

gender [t(2131) = 11.697, p = 0.000], with women presenting more awareness

of the persistence of gender inequalities (M=2.775, SD=0.731) than men

(M=2.393, SD=0.721) (see table 5).

Significant differences by age groups were found in the sub-sample of

women [F(4.1216) = 8.420, p = 0.000], but showed no effect for men.

Younger women (until the age of 34) present more egalitarian social representations on

average than all the other age groups (M=3.096, SD=0.720). As age increases,

gender-awareness views diminish, i.e. those that recognize that there is still some room

for improvement in the current state of gender equality.

The level of schooling also has significant impact on the assessments

of the current state of gender equality in Portugal, for both women [F(2.1341) =

53.813, p = 0.000], and men [F(2.776) = 5.307, p = 0.000]. Higher

levels of schooling are associated with greater awareness of gender inequalities.

Workers with basic education are, on average, less aware than those with secondary

education, or higher education. The latter are those with greater awareness. In the

group of women, significant differences were found between all three educational levels,

while for men, these differences are only significant between basic education

(M=2.288, SD=0.671) and higher education (M=2.489, SD=0.772). Having

children or not is another element with an impact on assessments of the current

situation of gender equality in Portugal. Significant differences could be noticed

between workers with and without children, for both women and men. Women without

children (M=3.026, SD=0.674) present a less positive view of the current

situation of gender equality than women with children, on average (M=2.718,

SD=0.731). In the same line, men without children show more gender awareness

(M=2.519, SD=0.782), than those with children (M=2.368, SD=0.701).

Finally, geographic area does not seem to determine individuals’ views

of the current situation of gender equality in these groups of workers.

Table 5 Perceptions of female workers and male workers of the evolution of

gender equality

| |

|

Mean |

SD |

Statistic

|

Mean

Difference |

| Gender |

Women |

2.775 |

0.731 |

t(2131)=11.697***

|

|

| Men |

2.393 |

0.721 |

|

|

|

Women

|

| Age |

≤ 34 |

3.096 |

0.720 |

F(4.1216)=8.420***

|

≤ 34 ≠

35-44* |

| 35 - 44 |

2.851 |

0.730 |

|

≤ 34 ≠

45-45*** |

| 45 - 54 |

2.751 |

0.727 |

|

≤ 34 ≠

55-59*** |

| 55 - 59 |

2.720 |

0.685 |

|

≤ 34 ≠ ≥

60*** |

| ≥ 60 |

2.641 |

0.717 |

|

|

| Education |

Basic |

2.530 |

0.718 |

F(2.1341)=53.813***

|

Basic ≠

Secondary** |

| Secondary

|

2.698 |

0.695 |

|

Basic ≠

Tertiary*** |

| Tertiary

|

3.044 |

0.700 |

|

Secondary ≠

Tertiary*** |

| Geographical area |

Urban |

2.780 |

0.725 |

t(1336)=0.599

|

|

| Rural |

2.751 |

0.750 |

|

|

| Children |

Yes |

2.718 |

0.731 |

t(430.327)=-6.563***

|

|

| No |

3.026 |

0.674 |

|

|

|

Men

|

| Age |

≤ 34 |

2.477 |

0.757 |

F(4.669)=0.582

|

|

| 35 - 44 |

2.466 |

0.744 |

|

|

| 45 - 54 |

2.407 |

0.739 |

|

|

| 55 - 59 |

2.345 |

0.687 |

|

|

| ≥ 60 |

2.400 |

0.719 |

|

|

| Education |

Basic |

2.288 |

0.671 |

F(2.776)=5.307**

|

Basic ≠

Tertiary** |

| Secondary

|

2.416 |

0.715 |

|

|

| Tertiary

|

2.489 |

0.772 |

|

|

| Geographical area |

Urban |

2.398 |

0.747 |

t(359.198)=0.375

|

|

| Rural |

2.377 |

0.640 |

|

|

| Children |

Yes |

2.368 |

0.701 |

t(775)=-2.374*

|

|

| No |

2.519 |

0.782 |

|

|

| *p<0.05

**p<0.01 ***p<0.001 |

Discussion

In general, the representations expressed by local public administration

employees from the CIM of Cávado tend towards agreeing with equality between men and women.

This is in line with the path followed by Portuguese society over the last fifty years,

after breaking with a dictatorship opposed to changes in gender roles within families, at

work and in society at large. However, in all the components of analysis, women consistently

showed more egalitarian social representations than men. It is mainly women who feel the

effects of gender inequalities on their rights and on their well-being. In this sense, they

are much more aware that equal opportunities between men and women are still largely

unfulfilled, as shown by the results of component 3, the one with the greatest difference

between the appreciation of men and women. This difference in attitudes based on gender has

been noted in the literature, with women usually having more egalitarian attitudes in

countries that are less egalitarian, although with some country variations (McDaniel, 2008). The high rates of women’s participation in the

Portuguese labour market also influence this difference, since it is recognized that women

with paid work tend to have more egalitarian attitudes than those without (Khoudja & Fleichmann, 2018; Lietzmann &

Froderman, 2023; Preston, 2023).

The predominance of egalitarian attitudes is visible both in the sphere of

work and in the sphere of household and care responsibilities. However, in general, the most

egalitarian social representations were found regarding the participation of men in private

life. The component relating to the sharing of responsibilities for household chores and

care is the one with the least differences between the overall average for men and women and

where it is possible to notice a generational effect, with men from younger generations

presenting more egalitarian views than older ones. In line with what has been demonstrated

by Cunha et al. (2017), Escobedo & Wall (2015), or

Farré et al. (2022), for the case of Portugal and Spain, tendentially

egalitarian attitudes regarding the role of men in the family can already be seen. This is

partly due to investments in public policies, or to an openness towards having gender

equality policies implemented, even though the least egalitarian social representations

continue to come from men. Also, a result of the evolution of public policies, education

seems to have an influence on the formation of more egalitarian attitudes, both in the case

of women and men.

The participation of women in the formal labour market already has a

longer tradition in Portugal, which has one of the highest female full-time employment rates

in Europe. However, although there is broad consensus on the participation of women in the

labour market, there is less agreement on the impact that participation has on family life.

In fact, if women's pursuit of full-time employment does not go hand in hand with men

entering the spheres of work, home, and care, the quality of domestic and care work could

suffer. This is particularly true in countries like Portugal, where low salaries, especially

among lower and medium-skilled workers, leave little room for outsourcing domestic services.

There is still dissonance between the level of social representations,

tendentially egalitarian, and the level of practices, which continues to be based on

traditional views of gender roles (Amâncio & Correia, 2019; Ramos et al., 2019; Cunha & Atalaia, 2019). This

was also the finding for this same sample in the study of work-life reconciliation practices

(Barroso et al., 2024).

On the other hand, the equal participation of men and women in the labour

market does not necessarily mean they perform the same tasks, as evidenced by one of the

statements where there was less disagreement, concerning the existence, in local public

administration, of tasks preferably aimed at women and others aimed at men. In the dimension

of work, representations of horizontal and vertical segregation still prevail, as other

studies of local public administration workers have already shown (Monteiro

et al., 2015). The essentialization of the existence of jobs for men and women in

local public administration, which includes some of the most traditionally gendered

professions, especially those that are less qualified/more manual and require physical

strength or resistance to bad weather, continues to be more associated with male

stereotypes. However, in our study, and contrary to the previous survey (Monteiro et al., 2015), women also stand out as having more egalitarian

attitudes than men in this variable, which may be due to the fact that we are dealing with a

more highly qualified sample of women. Similarly, it does not mean parity at the level of

leadership roles, since women were only a majority at the level of middle managers (DGAEP, 2023). And, although much more of a minority than in previous

surveys (Monteiro et al., 2015), but here following the same trend, for

16% of men and 17% of women there is still a preference for leadership roles to be occupied

by men, which highlights the apparent greater difficulty in eradicating the naturalization

of vertical discrimination, even among women. In this sense, it can also be affirmed that

the predominance of egalitarian views regarding the participation of women in paid work

exists alongside segmented views of occupations, in a labour market that continues to be

very segregated, both vertically and horizontally.

In spite of the predominance of egalitarian views, the data confirm

variations in gender attitudes according to certain sociodemographic variables. The role of

education, which continues to be a vehicle for the promotion of egalitarian ideals (Abrantes, 2016), is noticeable in the differentiation between attitudes

according to the level of schooling, with more qualified individuals demonstrating more

egalitarian attitudes, in line with the results obtained in previous studies (Du et al., 2021; Rivera-Garrido, 2022; Wall & Amâncio, 2007). Thus, education proves to be an ally of

gender equality and of the awareness that it is not yet fully implemented. In this study,

higher education, even more than age in the case of men, was shown to have an effect on

egalitarian attitudes in all three components under analysis.

Another important variable concerns parenthood and the experience of

having children or not. The data show that more egalitarian attitudes towards work-family

reconciliation and towards gender roles in the sphere of household and care responsibilities

prevail within the group that do not have children, especially amongst women, being less

present among those who do have them. As suggested by Stone (2007) and Stone and Lovejoy (2021), there are a number of idealized expectations

that, once a child is born, collide with reality, namely at the level of the effects of

maternity on the careers of women, or of the lack of organizational or institutional support

for reconciliation, resulting in the traditionalization of gender roles (Stone, 2007; Boehnke, 2011).

Regarding the geographic area, it seems to have more impact in the group

of men, where egalitarian views are more widespread in urban areas than in rural ones. Urban

areas provide more economic opportunities for the participation of women, particularly in

education and formal employment, and more and better services, such as transport or

childcare services, combined with a more diverse context, greater possibilities for

anonymity and, therefore, less social control (Evans & UNU-WIDER,

2017; Pandey & Kumar, 2021), which can explain differences in

attitudes between urban and rural areas. Additionally, the fact that there are significant

differences between workers from rural and urban areas can mean that those very

organizations have their own gender regimes (Connell, 2006) that are not

immune to context and the way workers are influenced by that context. However, women workers

seem to be resisting it, as no significant effects of geographic area were found for women

workers.

Finally, age is also a relevant factor in explaining variations in

attitudes: overall, in our study, younger people, especially working women, have more

egalitarian attitudes than their older coworkers. When particularly analysing the

perceptions on the evolution of gender equality over time, the experience of changes that

have already taken place leads to more optimistic views of the evolution of gender equality

(Connell, 2006). Younger generations, especially women, in turn, have

greater expectations for the future and are more demanding in terms of the breadth of change

and, thus, have fewer positive views of the evolution of equality. In the specific case of

Portugal, the end of the dictatorship in 1974 is an essential milestone that explains

generational differences: while the older generations have witnessed exceptional changes in

gender roles and in the rights of women over the last 50 years, the younger generations -

especially those born after the consolidation of democracy - are less likely to value the

changes that have already taken place. This reading is not straightforward in the case of

men, reinforcing the relevance of gender-disaggregated analyses.

Moreover, the fact that older people are those with less egalitarian views

in the dimension of work and family may result in them having more modest expectations and

demands concerning what gender equality should be. In addition, women show a linear and

recurrent tendency for each new generation to have more egalitarian representations than the

previous generation, and this seems to be changing in the case of men, reinforcing again the

relevance of gender disaggregated analysis. Recent literature has, for example, studied the

electoral behaviour of men and women in Europe (e.g. Abou-Chadi, 2024),

showing a divergence between the two, especially in the case of the young population, with

men joining parties with ideologies that are adverse to gender equality (Carbonell, 2025). In line with this, the present study indicates that

younger workers attitudes (up to the age of 34) do not differ significantly from those of

the generations that precede them (particularly those aged 35-44). Significant differences

were found between younger and older workers (60 or over), but only in the first two

components. In the third component, which concerns the dimension of awareness of achieving

gender equality, age has no significant effect in the group of men, which means that they do

not differ from any previous generation, including those over 60, in the way they assess the

evolution of gender equality over time.

![]()

![]()

![]()