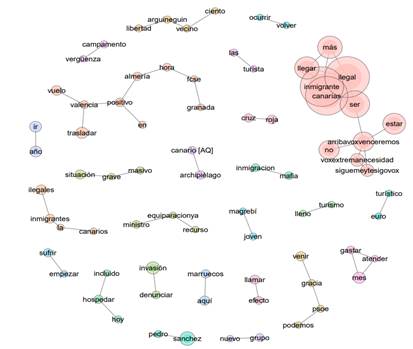

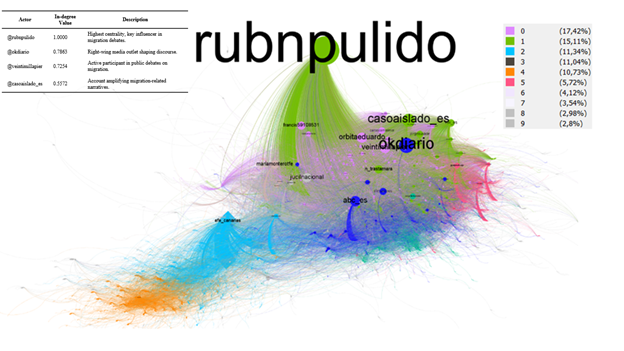

Remarkable Tweets:

@rbnpulido: “50.000 euros diarios que nos están suponiendo los 7.000

inmigrantes ilegales alojados a pensión completa en varios complejos turísticos de Canarias.

@rbnpulido: “Ya quisieran muchos de los españoles que están esperando a

cobrar el ERTE los 50 € diarios que están costando los más de 7.000 inmigrantes ilegales -NO

refugiados- que están alojados a pensión completa en hoteles y barracones militares de

Canarias. - 350.000 €/día y subiendo”.

@rbnpulido: “Una pareja de nórdicos denuncia un intento de robo en su

apartamento de Canarias. El autor fue un adolescente que huyó tras ser sorprendido hacia la

zona de #Arguineguín donde están alojados los inmigrantes ilegales llegados a Gran Canaria.

¿Casualidad?”

@ casoaislado_es “Mientras la inseguridad sigue disparada en Canarias, con

peleas, robos y delitos sexuales, las pateras repletas de inmigrantes ilegales siguen

llegando a nuestras costas. Aquí tenemos a otro grupo de ilegales que se graban poniendo

rumbo a España. Con porro incluido.

@veintimillapier: O el Gobierno frena el efecto llamada, o nos invaden por

Canarias, por las costas de Levante, o nos saltan las vallas de Ceuta y Melilla. Han

convertido España un coladero de inmigrantes ilegales.

@rbnpulido “Señal de peligro Detenidos en Valencia 16 inmigrantes ilegales procedentes de

Canarias tras detectarse 2 positivos. Los positivos han sido derivados a un hospital de

Alicante y los restantes al hospital de campaña para guardar cuarentena. ¿La cumplirán?”

@rbnpulido: “⚠️ Más de 100 inmigrantes «asistidos» por Salvamento en 24 h.

➕ de 600 km para recoger a invasores en zonas cercanas a los puertos controlados por las

mafias de la inmigración ilegal. ‼️ Ya son 735 las llegadas ilegales registradas en

Canarias. + 130% (2020) + 1.700% (2019)”

@rbnpulido:El #EfectoInvasión continúa. Más de 200 inmigrantes ilegales

llegan hoy a Canarias. Las llegadas a costas andaluzas no cesan y el CATE de Almería ya se

encuentra por encima de su capacidad. ⚠️ Casi 1.000 inmigrantes ilegales en lo que llevamos

de semana.

@okdiario: “Invasión de pateras en Canarias: la llegada de inmigrantes

ilegales pasa en un año de 1.497 a 16.760.”

@casoaislado_es: “Cruz Roja está siendo clave en el traslado de los

inmigrantes ilegales de Canarias a la Península. Esta ONG, subvencionada con decenas de

millones de euros, está ayudando al Gobierno de Sánchez a dispersar a los inmigrantes

ilegales por la Península. Debe ser investigada.”

@casoaislado_es: La Justicia debe investigar inmediatamente estos

movimientos de Salvamento Marítimo. ¡Están recogiendo inmigrantes ilegales en aguas

internacionales a más de 170 km de Canarias! ¿Colaboración con las mafias?

@rbnpulido:“La situación en Canarias es caótica. En plena pandemia, más de 8.000

inmigrantes ilegales han llegado en las últimas 4 semanas. FCSE, Salvamento,

sanitarios, protección civil, y ahora, también el Ejército. Para un bloqueo naval,

NO. Para alojarles a pensión completa, SÍ

.

@veintimillapier: Vecinos de Canarias convocan patrullas vecinales para

protegerse de los inmigrantes ilegales: ¡Nos han vendido!

rbnpulido: “El 2020 finalizó con más de 23.000 inmigrantes ilegales

llegados a Canarias. La gran mayoría, llegaron durante los últimos cuatro meses del año.

El Gobierno data en 6.000/7.000 los alojados. Más de 16.000 están en ¿paradero

desconocido?”

@ casoaislado_es: “En las últimas horas han llegado 8 pateras con más de 300

inmigrantes ilegales a Canarias. Solo en octubre y noviembre llegaron más de 13.500

ilegales. ¿La solución del Gobierno? Gastar otros 12,4M€ para cubrir sus

necesidades. Mientras tanto, muchos españoles pasando hambre.”

@okdiario: “Invasión de pateras en Canarias: la llegada de inmigrantes

ilegales pasa en un año de 1.497 a 16.760

“Este es un gobierno de mierda, hermano, pero esto se

va a acabar. A partir de mañana vamos a salir de caza. Grupo de cuatro o cinco moros

juntos: palizote”, "This is a shitty government, brother, but this is going to

end. From tomorrow we will go hunting. Group of four or five Moors together: palizote",

(Miquel Ramos y Eduardo Robaina 2021, la marea.es)

“Estamos armados hasta arriba. Los moros van a morir, te lo digo así de

claro”.

We are armed to the top. The moors are going to die, I tell you that clearly." (Miquel

Ramos y Eduardo Robaina 2021, la marea.es)

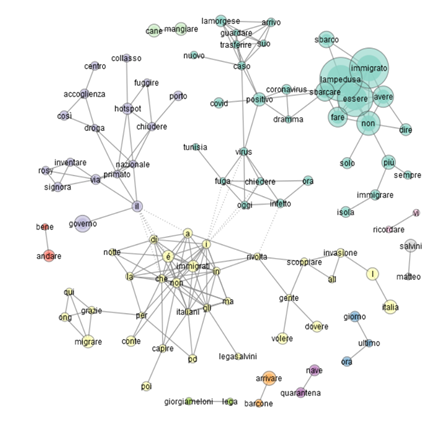

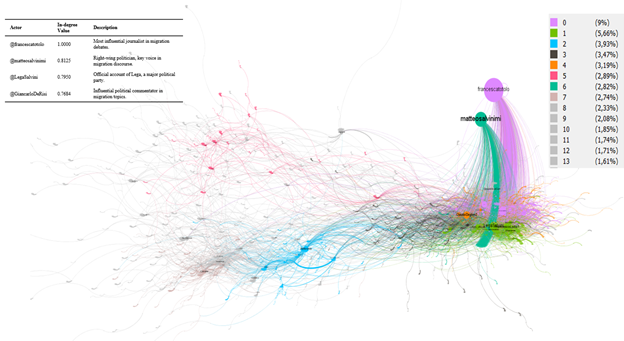

@francescatotolo: Uno dei barconi di #migranti sbarcato ieri a

#Lampedusa.In soli tre giorni, 1.559 immigrati sbarcati, nonostante il #Viminale sia a

conoscenza delle infiltrazioni terroristiche.

@matteosalvinimi: Dopo la Ong tedesca, con un carico di oltre 200

immigrati clandestini, ecco in azione la nave dei centri sociali, che torna in mare e ne va

subito a raccogliere 70 non lontano da Lampedusa. Avanti, c’è posto, tanto il governo non

muove un dito

@francescatotolo: 'Dopo i suoi reportage a #Pozzallo e #PortoEmpedocle,

@ChiaraNews sta ricevendo insulti e minacce da immigrati, soprattutto tunisini, come è già

successo alla sottoscritta.Noi non ci fermiamo, ma rilanciamo partendo per #Lampedusa

@francescatotolo: A Soufli, in #Grecia, i residenti hanno beccato,

facendoli arrestare, 29 immigrati clandestini che avevano rubato i loro animali per

mangiarseli.Quindi non sono leggende di #Lampedusa?

@francescatotolo: Un #migrante esce tranquillamente dall’hotspot di

#Lampedusa.Come ci spiega un residente, gli immigrati vanno e vengono, peraltro buttando

immondizia e facendo bisogni ovunque

@matteosalvinimi: Arrivati da Lampedusa e trasferiti a Cori (Latina), i

“turisti per sempre” come ringraziamento adesso azzannano anche le Forze dell’Ordine. Cosa

ancora piú preoccupante perché in quella struttura sono stati trovati 12 immigrati positivi

al Virus.

@francescatotolo 'Un gruppo di immigrati tunisini, fuggito dall’hotspot di

#Lampedusa, è stato rintracciato dalle Forze dell’Ordine.#clandestini #immigrazione

@francescatotolo È arrivata questa mattina all’alba la nave quarantena

#GnvAzzurra, che ospiterà buona parte degli immigrati clandestini che nelle ultime settimane

hanno letteralmente invaso #Lampedusa.

@LegaSalvini: '#MORELLI: ⚠️⚠️⚠️ LAMPEDUSA INVASA! Più di 600 immigrati

sbarcati sull’isola in 24 ore.QUESTO GOVERNO È LA ROVINA DELL’ITALIA!!!

@GiancarloDeRisi: 'Salvini, ancora sbarchi a Lampedusa: "Governo da

mandare a processo". Stanotte sono sbarcati circa 700 immigrati: "Senza controlli è una vera

invasione. Non è solo un problema economico, ma anche sanitario"

@francescatotolo: 'Da #PortoEmpedocle è partita la nave #GnvAzzurra che

farà da hotspot galleggiante per gli immigrati sbarcati a #Lampedusa.Il costo giornaliero

sarà di più di 50 mila euro, per un totale di quasi 4,8 milioni di euro per 92 giorni.Tutto

ciò per “accogliere” #clandestini tunisini

@matteosalvinimi '‼️ PAZZESCO, IMMAGINI DI POCO FA!Il governo sposta gli

immigrati clandestini da Lampedusa su navi da crociera che costano agli italiani milioni di

euro? E a Lampedusa ricominciano gli arrivi, in un ciclo continuo

@LegaSalvini #Salvini: ‼️ PAZZESCO, IMMAGINI DI POCO FA!Il governo sposta

gli immigrati clandestini da Lampedusa su navi da crociera che costano agli italiani milioni

di euro? E a Lampedusa ricominciano gli arrivi, in un ciclo…

@francescatotolo 'Dei 350 #migranti saliti a bordo della nave quarantena

#GnvAzzurra lunedì scorso a #Lampedusa, ben 12 sono positivi al #COVID19 e 6 casi sono

incerti.Che attendibilità hanno i tamponi effettuati quando gli immigrati sono sbarcati a

Lampedusa?#Lamorgese #Conte #Speranza

@matteosalvinimi '#Salvini: Da stanotte a Lampedusa sono sbarcati 700

immigrati. Non è solo problema economico, ora anche sanitario. Non possiamo permetterci

centinaia di sbarchi ogni giorno: producono criminalità e problemi. #lariachetira'

@GiancarloDeRisi 'Ora anche il sindaco Martello accusa apertamente il

governo che ha tradito tutte le aspettative di Lampedusa e dei residenti terrorizzati dalla

possibilità di essere contagiatiLampedusa invasa da immigrati infetti: “Ora basta sbarchi”

@francescatotolo: 'A breve, io e @ChiaraNews partiremo per #Lampedusa.

Faremo un reportage unico, svelando ancora una volta il business dell’immigrazione che il

governo #Conte sta favorendo con i #portiaperti. Aiutateci a fermare la nuova invasione di

immigrati➡️

@francescatotolo: 'Dei 350 #migranti saliti a bordo della nave quarantena

#GnvAzzurra lunedì scorso a #Lampedusa, ben 12 sono positivi al #COVID19 e 6 casi sono

incerti.Che attendibilità hanno i tamponi effettuati quando gli immigrati sono sbarcati a

Lampedusa?#Lamorgese #Conte

@matteosalvinimi:'Nave Azzurra, 273 immigrati a bordo, in viaggio fra

Lampedusa, Trapani e Augusta da giorni, coi sindaci (PD e 5Stelle) che negano lo sbarco.

SEQUESTRATORI anche loro???

@GiancarloDeRisi: 'I poliziotti non ne possono più: “Lampedusa scoppia di

immigrati: il Governo si è arreso all'invasione e scarica tutto sulla polizia lasciandola

sola, in prima linea e con pochi mezzi a disposizione"

@LegaSalvini: 'PAZZESCO. IMMIGRATI INDESIDERATI O CONDANNATI TORNANO A

LAMPEDUSA, 44 ARRESTI DALL'INIZIO DEL MESE

@LegaSalvini: '🔥LAMPEDUSA, SI SONO UNITI TANTI CITTADINI E ORA PASSERANNO

LA NOTTE BLOCCANDO LA STRADA CONTRO L’INVASIONE DI IMMIGRATI CLANDESTINI

NELL’ISOLAPacificamente, gandhianamente. Onore a voi, lampedusani coraggiosi: tantissimi

italiani sono con voi!

@GiancarloDeRisi: '#Lampedusa in #rivolta, dopo gli ultimi arrivi: "Non

vogliamo più #sbarchi, non vogliamo immigrati sul nostro suolo, il vaso è colmo. Non

vogliamo più essere complici di nuovi #schiavi. Questa gente deve rimanere in Africa"

Observable change of the accounts:

2020 2025

2020 2025

![]()