Introduction

Youth is central in cultural and political change, often associated with social mobilization and countercultural movements. While research on activism has primarily focused on youth’s progressive political engagement, conservative and liberal-humanist alignments have received comparatively less attention. However, the recent rise of radical right-wing parties has sparked growing interest in this phenomenon, as an increasing number of young voters across Europe and the U.S. seems to align with more conservative ideologies.

Journalists, political analysts, and social scientists have reported on this shift in the media, with figures like Naomi Klein (2024) suggesting that young people's attraction to the radical right may be partly attributable to a reaction to the left’s rigid stance on social justice issues. Outlets such as Project Syndicate (Bröning, 2022) and Politico (Cokelaere, 2024) have identified similar trends in France, Germany, and other European nations, where younger voters are increasingly supporting right-wing parties, challenging the notion that youth inherently align with progressive positions. In the U.S., the American Survey Center (Cox, 2023) has also reported a growing shift among young men toward conservative views, highlighting the broader political implications of this trend.

In Spain, a report by El País (Silió, 2024) highlights a growing openness among university students-particularly future engineers, lawyers, and economists-toward right-wing views, while this shift is less pronounced among those in the humanities, experimental sciences, and health sciences. This trend reflects a widening political spectrum among Spanish youth being part of a broader, eclectic, cultural change (García Barnés, 2025). Furthermore, political scientist Pablo Simón (2024), in his El País opinion piece The New Clash of Sex -similar to political scientist Eva Anduiza in the same newspaper (2025) or the web of Spain's national state-owned public television (Caballero, 2025)- argues that young men’s rejection of feminism is a key factor that is driving their conservative shift, as young women surpass them in educational attainment and professional success. This outperformance is also observed by data journalist John Burn-Murdoch in the Financial Times in different countries, including Spain (2024b).

Burn-Murdoch’s article A New Global Gender Divide is Emerging (2024a) underscores the ideological gap between young men and women across countries such as South Korea, the U.S., Germany, and the UK, where young women increasingly identify as progressive, while young men are leaning conservative. This growing gendered divide in political ideology raises questions about whether media portrayals accurately capture the complexities of this trend or oversimplify the interplay of complementary factors.

Theoretical frameworks

A growing body of research has sought to explain these ideological shifts among younger generations, especially the increasing appeal of conservatism for young men in recent years. While much attention has been given to the youth’s historical association with progressive movements (Flacks, 1971; Bell, 1976; Melucci, 1989, 1994; Earl et al., 2017; Johnston, 2019; Della Porta, 2020), recent studies highlight the need to analyze the mechanisms driving conservative identification. Economic insecurity, cultural backlash, and gendered political socialization have been proposed as key drivers of this trend. The relative weight of these factors and their interactions remain the subject of debate. Exploring the ideological realignment of youth in Western democracies requires situating the phenomenon within broader theoretical discussions, drawing on key academic frameworks.

Generational and gendered divides

Scholars have long emphasized generational divides in politics (Mannheim, 1993 [1928]; Bell, 1976; Inglehart, 1991; Putnam, 2000; Dalton, 2008). Regarding the rise of authoritarian populism in Europe and the United States, Norris & Inglehart (2019) highlight significant intergenerational differences in support for radical right-wing populist parties. Younger generations, who tend to embrace post-materialist values, have traditionally shown the least support for these parties.

However, some case studies suggest that young people in some countries are beginning to align with more conservative positions than adults. Lorente & Sánchez-Vítores (2022) analyze the relationship between political ideology and age in Europe, finding that whereas young people are still more left-leaning than adults, this gap is narrowing. Adults are shifting toward the left while younger generations are moving to the right, a trend attributed to cohort or generational effects due to different political socializations. Earlier generations exhibited more progressive ideological profiles, whereas today’s youth appear less progressive than their predecessors, as suggested by research on Italy (Corbetta et al., 2013) and the U.S. (Twenge, 2023).

Moreover, some studies suggest that these political divides are also profoundly gendered (Inglehart & Norris, 2000). As Mudde (2007) observed over a decade ago, older generations with a more traditional and materialist outlook as well as individuals-predominantly men-with lower levels of education and from rural areas are more likely to support these parties. More recently, Mudde (2019) suggested that economic instability, resistance to social changes, and perceived erosion of traditional gender roles may make younger men more receptive to nationalist and anti-immigration messaging from these parties.

The intersection of gender and economic precarization deepens the complexity of these trends. The incapacities of a nation-state dealing with large-scale problems, such as the financialization of the economy and new patterns of production and consumption derived from technological applications in production and decision-making, have resulted in greater individual responsibility, weaker social protection, and increased labor precarity (Beck, 1992; Sennett, 2000).

These structural transformations affect young men, who have historically relied on stable industrial employment as a foundation for adult life. With the erosion of these pathways, many experience frustration, which makes them more likely to align with conservative and traditionalist ideas (Hochschild, 2016; Vance, 2016). These analyses suggest that segments of society may be moving toward more conservative positions, especially as younger men influenced by radical party narratives show increasing receptiveness to them.

Frustration and politics in the erosion of the transition to adulthood

The traditional model of transitioning to adulthood has become increasingly unstable. Young people now experience more individualized life paths (Giddens, 1991; Beck et al., 1994; Furlong, 2013), moving through phases in a non-linear trajectory. The loss of stable reference points -such as family, education, and labor market integration (Dubet & Martuccelli, 2000; Bauman, 2001; Beck & Beck-Gernsheim, 2001)- has contributed to growing uncertainty and dissatisfaction. This scenario may be linked to a shift toward more conservative or moderate political positions among young people in recent decades, particularly in contrast to generations that experienced more predictable and linear life-cycle patterns.

This perspective aligns with broader patterns of conservatism that have historically emerged in response to rapid societal change (Bell, 1963; Huntington, 1968). However, this contribution also draws inspiration from thinkers such as Raymond Aron or Michael Oakeshott as a conceptual lens to approach and interpret how young people identifying with liberal-conservative currents in Spain over the last two decades may have understood politics and public affairs.

While Aron (1962) criticizes ideological dogmatism and warms about its dangers, underling the importance of political moderation, Oakeshott (2017 [1956]) is suspicious of abstract rationalism and rationalistic social engineering and proposes that individuals prefer the familiar over the unknown, the tried over the untried, and gradual adaptation over radical transformation. In this light, Oakeshott’s conservative skepticism (1962, 1975, 2017 [1956]), for example, becomes particularly illuminating since prioritizes practical knowledge over rigid theoretical constructs and dogmatism, values tradition and liberal institutions, favors gradual changes rather than sweeping reforms, and upholds individuality and civil association over utopian collective movements and herd mentality.

From another theoretical lens, some scholars argue that in late capitalism, success and failure are increasingly framed as personal responsibilities rather than structural outcomes (Boltanski & Chiapello, 2005; Han, 2012; Fisher, 2017; Berlant, 2020). Cabanas & Illouz (2019) suggest that the rise of positive psychology and self-help culture further reinforces this shift, placing the burden of well-being on individuals while depoliticizing structural inequalities. As a result, economic hardship is often perceived as a personal failure rather than a systemic issue. Young men in particular tend to internalize the meritocratic discourse that legitimizes inequality (Littler, 2018; Sandel, 2020), interpreting their economic instability as a reflection of personal shortcomings rather than broader socioeconomic structures.

Thus, the emotional and psychological dimensions of masculinity are also supposed to shape political behavior, constructing manhood around self-reliance and emotional detachment (Blais and Dupuis-Déri, 2011; Kimmel, 2017; Ging, 2017; Nagle, 2017; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). Economic precarity means that autonomy is a desire more than a reality (Sennet, 2000), prompting contradictions in emotional expectations (Standing, 2011). These contradictions lead to different ideal types of political responses: while some young disengage entirely and withdraw from mainstream politics (Putnam, 2000; Bauman, 2001), others become aware of social injustices and go on to engage in new forms of alternative activism, albeit often in precarious and fragmented ways (Norris, 2003; Dalton, 2008; Monticelli & Bassoli, 2017; Della Porta, 2020).

Finally, young men are presumed to express their frustration through more reactionary political engagement, particularly when confronted with narratives of cultural decline and perceived loss of status. In such cases, resentment toward democracy and progressive values may be mobilized. These dynamics unfold in increasingly polarized contexts, where social media amplifies frontlash-backlash cycles among youth as counter-responses to progressive narratives-and vice versa (Alexander, 2019; Alexander & Díez García, 2021).

Beyond stereotypes: rethinking youth political trends in the XXI century

Academia has reopened classical theoretical debates, shedding light on these new political trends. Drawing on classical approaches, Eatwell & Goodwin (2018), as well as Fukuyama (2019) for example, analyze the intersection of class politics and status politics (Lipset, 1963; Hofstadter, 1963), arguing that support for national populism, on both the left and right, against liberal democracy reflects not only an objective economic disadvantage but also status anxiety: the fear of future marginalization and relative downward mobility (Bell, 1963; Díez García et al., 2021).

This sense of insecurity, coupled with discontent toward political elites, has fueled the rise of nationalist populism as both a reaction to and a challenge against liberal democracy. This apprehension is particularly acute among less-educated men, who may perceive themselves as excluded from the meritocratic promise and overlooked by progressive elites, prompting social justice claims centered on critical theories of race and gender (Pluckrose & Lindsay, 2020), thereby shifting the focus away from material concerns (Guilluy, 2019; Piketty, 2019).

In an increasingly de-institutionalized world where education, employment, and starting a family no longer follow a linear pattern, the media often portrays young women as champions of social progress, personal autonomy, professional success, and advocacy for equality, minority rights, and climate action. Conversely, young men are repeatedly depicted as apathetic, resistant to change, or even as reactionary and adherents of misogynistic or toxic ideas (Kimmel, 2017; Ging, 2017; Nagle, 2017).

Gendered political divides are also reported in Spain, where men and women within the same generational cohort often exhibit distinct ideological orientations in the media or among academics (Anduiza, 2025; Caballero, 2025). However, framing these trends in oppositional terms - although useful in illustrating contemporary social tensions-risks oversimplifying the sociological complexity of youth who identify with non-progressive politics.

More concerning is the potential for self-fulfilling prophecies. Labeling these individuals may contribute to their disengagement from mainstream politics, inadvertently pushing them toward more radical positions. The widespread use of taxonomies such as "far-right," “new far-right,” or “fascism” may have this unintended effect, particularly when reinforced by sectors of the academic community. The alternative and complementary analytical framework proposed argues that in the first two decades of the 21st century, younger generations have exhibited a liberal-conservative temperament consistent with the classical features of both traditions.

Segments of both young men and women identifying with right-wing politics seem to incorporate elements of economic and political liberalism alongside traditionalist attitudes and religiosity, while maintaining openness to postmaterialist values prioritizing personal fulfillment and individual rights. Examining how young Spaniards have defined and inhabited conservative identities is crucial within a socio-economic and political context that is undergoing profound transformations that challenge life opportunities, which were exploited in the last decade by populist forces to mobilize potential followers.

Although much of the media narrative and academic literature emphasizes a rightward shift, the conceptual frameworks used to analyze it often focus on extreme actors and radical discourses on the right or stereotyped pictures, which may no longer fully capture the ideological articulations operating among younger generations for decades. Particularly relevant is the increasing use of labels such as “liberal” and “conservative” in a segment of youth organizations' public discourses (Díez García & Rollón, 2024) or sometimes in the media (Silió, 2024; García Barnés, 2025), which make them valuable sensitizing concepts illuminating social inquiry (Blumer, 1954), as discussed in the next section.

Drawing on Mannheim’s insights into the situational nature of political generations, Aron's distrust of ideological dogmatism and reductionism in political thought, and Oakeshott's skepticism, this contribution considers the “liberal-conservative view” as a practical formula or heuristic framework for approaching this youth political space, moving beyond straightforward translations of ideological coherence. While acknowledging the normative dimension of Oakeshott’s and Aron’s political thought, this work draws on their conceptual tools from political theory and philosophy to offer richer interpretations of empirical phenomena

1

.

The methodological section further addresses this theoretical ambiguity and its implications for operationalization. Drawing on liberal and conservative thinkers does not imply the formulation of testable empirical hypotheses derived directly from their political or philosophical doctrines. Together with other theoretical frameworks, these liberal-conservative perspectives help to sensitize major concepts within such traditions of thought, guiding empirical observation without imposing closed or verifiable theories.

Karl Mannheim's concept of ideology consists of two different conceptions: ‘total’ and ‘particular’. Both are grounded in distrust regarding what the other is or says as a political opponent. This does not allow “to reach an understanding of his real meaning and intention”, putting the individual aside and trying to understand “what is said by the indirect method of analyzing the social conditions of the individual or his group” (1954 [1936], p. 49). However, the ‘particular’ conception of ideology, while denoting skepticism toward the ideas and representations advanced by our opponent, is also related to other sociological approaches that focus on analyzing ‘frames of reference’ (interpretative schemata that people use to simplify and condense social life (Goffman, 1974).

Surveys typically include the political self-placement scale used in this study, where respondents position themselves along a left-right spectrum. The aggregate data obtained enables researchers to determine the average ideological position of groups or collectives using statistical indicators, allowing for conclusions about their political orientation. However, the researcher shifts from a ‘particular’ conception of ideology to a ‘total’ one. This contribution does not emphasize a ‘total’ conception of ideology but rather examines the elements and traits that shape a liberal-conservative perspective, helping to simplify and condense the ‘particular’ ways in which youth identify with right-wing politics.

This liberal-conservative view suggests that younger generations in Spain who have gravitated toward liberal-conservative ideas may not merely react against progressive politics but instead have long been embracing a cautious, pragmatic skepticism toward politics and public affairs. Their political orientation can be understood as a form of pragmatic temperament, shaped by a recognition of uncertainty and status anxiety, yet marked by a distrust of imposed policies and social discourses. This echoes liberal and conservative thinkers, such as Aron and Oakeshott’s critique of dogmatism and the defense of moderation and tradition as a foundation that may offer a degree of stability for young individuals to be themselves and shape their identities, alongside support for small government and liberal institutions.

This view implies that political preferences for right politics among younger generations in Spain are linked to economic conditions and cultural trends, burn also reflect a disposition toward politics that prioritizes individual experience over ‘total’ conceptions of ideology (Mannheim, 1954 [1936]), through a lens of practical skeptic temperament rather than radical transformation.

Objective, research questions, and methodology

This article aims to contribute to the growing body of research on the political dynamics of younger generations in Spain over the last two decades, with a focus on youth identification with liberal-conservative ideas. The study seeks to move beyond simplistic stereotypes and binary categorizations, offering a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the youth political landscape since the turn of the century.

Instead of focusing on extreme cases -such as the rise of far-right movements, radical populist parties, or specific electoral outcomes- this article adopts a broader perspective on political identification, considering a continuum of ideological positioning over a wider temporal scope. Specifically, it explores the intersection of the political categories “liberal” and “conservative” as sensitizing concepts, offering a sense of reference and guidance in approaching empirical instances (Blumer, 1954)

2

. Rather than treating them as normative political theories or ‘total’ conceptions of ideology (Mannheim, 1954 [1936]), these are approached as operational and sensitizing constructs, as justified later, to shed light on the proposed research questions.

Research questions and hypotheses

The study focuses on two main research questions, including specific hypotheses that address concrete aspects discussed in the theoretical section. These are:

RQ. 1: How has the ideological landscape of Spanish youth evolved over the past two decades?

Hypothesis 1.1: Spanish youth have experienced a shift toward the right in their political self-placement over time.

Hypothesis 1.2: There is a gender gap in the ideological evolution, with men and women exhibiting different patterns in the rightward shift.

RQ. 2: What socioeconomic, political, and cultural factors have contributed to the increasing identification of Spanish youth cohorts with liberal-conservative positions over the past two decades?

Hypothesis 2.1: Greater support for economic liberal policies (e.g., less government intervention to reduce income differences) and higher satisfaction with Spanish democracy are associated with a more liberal-conservative positioning.

Hypothesis 2.2: Traditional socialization values (e.g., the importance of doing what is told and following rules) and higher religiosity are positively associated with liberal-conservative identification, even when individuals express openness to postmaterialist values (e.g., satisfaction with life).

Hypothesis 2.3: Skeptical attitudes toward minorities (e.g., support for gays and lesbians’ way of life), immigration, and nature and the environment are associated with more liberal conservative identification.

Hypothesis 2.4: Higher relative household income and periods of GDP contraction (i.e., economic downturn) have contributed to a shift toward liberal-conservative positioning over the past two decades.

Hypothesis 2.5: Gender differences and the passage of time interact with these political, economic, and cultural factors in shaping liberal-conservative positioning.

These research questions and hypotheses build on the theoretical discussion to examine the political identity of Spanish youth, particularly their identification within the liberal-conservative spectrum over the last twenty years. The methods and data analysis are detailed below, followed by a justification of the ‘liberal-conservative’ synthesizing concept and its operationalization. Within the Results section, the ideological shifts from 2002 to 2023 are examined first, highlighting the gender gap in this respect. Second, significant political, cultural, and socio-economic variables influencing trends in identifying with these political positions are analyzed to outline youth liberal-conservatives' traits.

Methodology and data analysis

The article incorporates two types of data sources. The primary source consists of aggregate data from the ESS, covering rounds 1 (2002) to 11 (2023)

3

. The first question is addressed by comparing the political self-placement of young respondents aged 18 to 29 at the beginning of the century and at the start of the current decade, H.1.1, with differences analyzed by gender for H.1.2

4

.

A factorial ANOVA has been estimated to examine the combined effects of gender and survey waves as independent variables on the dependent variable of political self-placement

5

, with accompanying graphical representations of mean values and the distribution of political positioning percentages by year and gender. This approach enables observing potential interactions between both factors, identifying whether the gender gap in self-placement varies over time.

After that, a multiple linear regression analysis addresses the second issue: which economic and political views, values, attitudes, and socio-economic factors contribute to a higher youth liberal-conservative identification?

6

. Taking political self-placement as the dependent variable leaves the door open to breaking down which features lie behind it, with the intention of the emphasis not being placed on a ‘total’ conception of ideology (Mannheim, 1954 [1936]), but more on particular components underlying the positioning of young people.

The decision to pool data from all available ESS rounds (2002-2023) is based on several methodological considerations. First, combining multiple waves substantially increases the sample size, enhancing the statistical power and robustness of the estimates. Second, using data across different time points allows for capturing individual-level and period-specific effects, helping to distinguish patterns from contextual fluctuations. To account for the temporal dimension, survey rounds, or years, are included as dummy variables ―from 2004 to 2023, with 2002 as the reference category― alongside the GDP growth rate as a single independent variable and a relative household income measure by wave.

This approach mitigates cohort and period effects, allowing a better understanding of how political orientation responds to economic and political cycles over time. Acknowledging that other contextual factors may influence these dynamics and require complementary analyses to address unobserved heterogeneity, the included variables offer a reasonably robust approach to answering the two research questions and addressing the hypothesis.

The 20 independent variables in the model are grouped into two main dimensions. The first includes individual socio-economic and well-being variables, such as gender and relative household income by wave (decile-based)

7

, as well as religious sentiment and life satisfaction

8

. The second category considers two key themes: i) views on authority compliance, economic redistribution, and institutional performance

9

; and ii) civil rights, freedoms, and attitudes toward nature and the environment

10

. Finally, the two contextual variables are considered: the ESS rounds, or years, and their associated GDP growth rate

11

.

Both dimensions employed with contextual variables capture the structural conditions that influence shifting political self-placement and the personal belief systems and values shaping political worldviews. They reflect the intersection between status politics, which underlies cultural backlash mechanisms (Hochschild, 2016; Vance, 2016; Fukuyama, 2019; Norris & Inglehart, 2019), class politics, particularly concerning economic inequality and redistribution (Guilluy, 2019; Piketty, 2019), and the emergence of national populism (Eatwell & Goodwin, 2018; Vance, 2016). These dynamics also shape the divides between post-materialist and materialist values (Inglehart, 1991) and gender differences (Inglehart & Norris, 2000).

Table 1 summarizes the independent variables used in the statistical analyses, grouped by analytical dimensions. Each variable is grounded in the literature discussed in the theoretical section and may be linked to one or more of the study’s hypotheses. The table aims to offer an operationalization guide and analytical framework map, rather than providing an exhaustive list of authors' perspectives and theories to test empirically.

Table 1 Operationalization guide and analytical framework map

| Dimension | Variable | Related theoretical frameworks (non-exhaustive) | Hypotheses |

|---|

| A. Socio-economic & well-being. Include contextual variables | Gender (Dichotomic) | Gendered political socialization, increasing ideological gap: younger men show growing alignment with conservative views as a reaction to shifts in education, status, and feminism (Inglehart & Norris: gender gap; Mudde: traditionalism and resentment) | H.1.2

H.2.5 |

| Relative household income (Decile-based scale) | Income-based status politics: higher-income youth tend to support economic liberalism and status-preserving (Bell, Eatwell & Goodwin: relative socio-economic status; Piketty, Guilluy: material concerns, elites; Sandel: meritocratic illusion) | H.2.4

H.2.5 |

| Satisfaction with life (11-point scale) | Postmaterialist well-being and depoliticization (Inglehart: postmaterialist value shift, where personal fulfillment overtakes redistribution demands; Cabanas & Illouz: emotional individualism and the privatization of distress) | H.2.2

H.2.5 |

| Religious sentiment

(11-point scale) | Traditional values and conservative alignment: Religiosity reinforcing authority, hierarchy, and opposition to values change (Inglehart & Norris: value stability; Mudde: identity defense; Huntington: religion as civilizational marker) | H.2.2

H.2.5 |

| ESS wave 2002-2023 (Scale, ANOVA; Dummy, Linear regression) | Period and cohort effects reflect ideological shifts linked to socio-political transitions (Lorente & Sánchez-Vítores: generational trends; Beck, Giddens: late modernity; Mannheim: generations & ideology). | H.1.1

H.2.5 |

| GDP growth (Numerical: percentage) | Economic insecurity and ideological realignment: economic cycles influencing insecurity perception and political trust. Recessions and conservative realignment (Eatwell & Goodwin: populism; Vance: precarity narratives; Hochschild: emotional politics) | H.2.4

H.2.5 |

| B. Political & economic opinions, attitudes, and values | Importance of obeying and following the rules (6-point scale) | Authority compliance and cultural orientation reflecting values placed on stability and order (Bell, Huntington: conservatism & rapid societal change; Oakeshott’s emphasis on practical knowledge and skepticism toward radical change) | H.2.2

H.2.5 |

| Satisfaction with the country’s democracy (11-point scale) | System legitimacy, and confidence in democratic institutions (Norris: democratic support; Eatwell & Goodwin: national populism; Alexander: civil sphere; Oakeshott, Aron: liberal institutions) | H.2.1

H.2.5 |

| Attitude toward income differences reduction (5-point scale) | Rejection of economic intervention: liberal economic beliefs, meritocratic justifications (Fukuyama: individualism; Oakeshott, Aron: liberal institutions; Sandel: meritocratic illusion; Boltanski & Chiapello: new spirit of capitalism). | H.2.1

H.2.5 |

| Attitudes toward nature & the environment (6-point scale) | Environmental concern and postmaterialist values, rejection of sweeping reforms (Inglehart: values shift; Oakeshott: resistance to abstraction and support for gradual changes). | H.2.3

H.2.5 |

| Attitudes toward immigration (11-point scale) | Cultural backlash and status anxiety: immigration as an economic and cultural threat, triggering nationalist backlash (Mudde: nationalism, identity defense; Hochschild: deep stories; Eatwell & Goodwin: status anxiety, national populism) | H.2.3

H.2.5 |

| Attitudes toward gays and lesbians (5-point scale) | Traditionalism, moral values, perceived cultural loss, cultural backlash, status anxiety (Kimmel: masculinity crisis; Norris & Inglehart: cultural backlash) | H.2.3

H.2.5 |

By integrating these variables and perspectives, this analytical strategy acknowledges the multi-dimensional nature of political identification. Instead of treating ideology as a fixed trait, it aligns with Mannheim’s (1954 [1936]) classic conception of ideology as a product of historical context and a set of lived experiences shaped by particular social positions and political learning.

Finally, the study incorporates quantitative data from the Center for Sociological Research (2023, ES3409) to complement the ESS analysis, particularly to justify the use of the liberal-conservative category as an operative analytical construct rather than a pre-defined political label. This allows the analysis to remain sensitive to the shifting content and contested meaning of liberal conservatism in contemporary Spain, acknowledging its strategic and contingent nature.

The intersection of theory and method: sensitizing concepts and operationalization

Using the traditional political self-placement scale to represent rightward positions within the liberal-conservative analytical framework presents a significant theoretical and methodological challenge. Alternative instruments, such as political identification categories, could offer analytical advantages in defining political identity configurations. However, this contribution does not adopt that approach due to the limitations of the ESS, which does not include variables that allow for the classification of respondents into political categories such as progressive, social democrat, liberal, conservative, Christian democrat, ecologist, or feminist.

Therefore, the traditional left-right scale is used here as an analytical tool to analyze identification with ‘particular’ ideological values and ideas (Mannheim, 1954 [1936]), particularly within the liberal-conservative spectrum. This enables a clearer analysis of the political landscape since the turn of the century, as the determinants that shape this spectrum provide opportunity for a more nuanced approach.

In Spain, both political categories are often classified as right-wing from a political-professional perspective. Nevertheless, the conventional left and right categories may obscure or oversimplify the social processes inherent in the study of political identification (Laraña, 1994; Díez García & Laraña, 2017). These categories carry different meanings for individuals, making it difficult to ascribe them to an objective and universal significance (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas [CIS], 2011; Lorente, 2019).

For this reason, analyzing different variables contributing to a stronger identification with rightward positions can help clarify underlying intersected factors shaping political identities. As outlined in the theoretical section, these positions may incorporate liberal traits, conservative or traditionalist ideas, and attitudes, but a certain openness to post-materialist values. To capture this, the article proposes a broader “liberal-conservative” conception.

Liberalism and conservatism have distinct historical and philosophical roots, which represent different traditions within political theory

12

. This contribution treats them as sensitizing concepts drawn in public discourses to analyze youth political identities. Although there are differences, this approach allows for a comprehensive representation of these political orientations within the Spanish context. Along with others like “far right”, both are framed in media, politics, or activism as shorthand for stances opposing left-leaning positions, such as progressivism, socialism, social democracy, or the social justice agenda.

Despite the lack of an exact meaning correspondence between the left-right axis and the progressive-conservative spectrum, the use of the latter (like the liberal-conservative conception( remains narratively faithful to public discourse. It also maintains a degree of commensurability with people's experience (Snow & Benford, 1988) when discussing politics. This practical coherence underlies public discourse and everyday experience while reflecting a degree of empirical alignment.

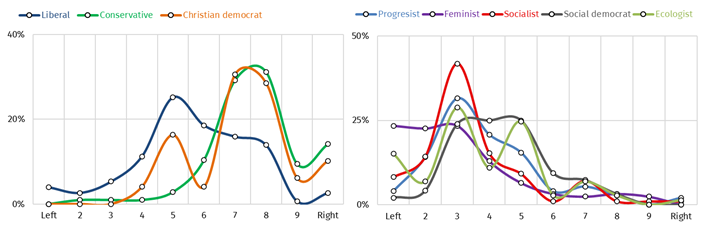

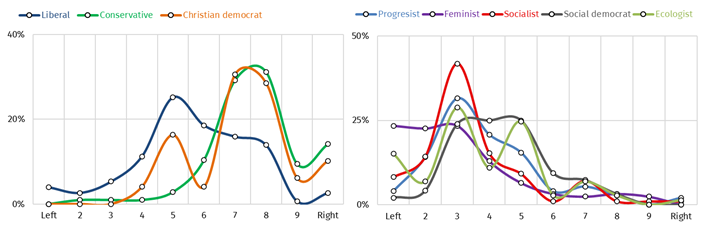

This alignment is reflected in data collected by the CIS (2023), as shown in Figures 1 and 2. These figures illustrate the distribution of various political categories along the left-right continuum among young people aged 18 to 29

13

, showing that self-identified liberals and conservatives tend to concentrate in the upper half of the left-right scale (positions 5 to 10, Right). Specifically, 76.8% of young respondents who identify as liberal place themselves between positions 5 and 10, with a notable 51.6% leaning toward more right-leaning positions (6-10, Right).

This pattern is even more pronounced among those who self-identified as conservatives, with 95% occupying these higher positions. In contrast, explicitly left-leaning identities, such as feminist, socialist, or social democrat, cluster primarily at the lower end of the scale

14

.

Figures 1and 2 Distribution of political categories across the left-right continuum, 2023

Source: Center for Sociological Research, ES 3409. Own elaboration

This empirical overlap between the liberal-conservative distinction and the upper end of the left-right continuum supports its relevance as an analytical tool, but it suggests its conceptual autonomy. Liberal and conservative do not fully map onto left and right; they are partially overlapping but not identical categories. In other words, while most conservatives are right-leaning, not all right-leaning youth identify as conservative, and the same applies to liberals. This is particularly relevant for younger generations, and the multidimensional phenomenon of youth shifting rightward, as they may exhibit traits aligned with different political ideas.

Moreover, from a methodological perspective, the political self-placement scale serves two key purposes. First, it captures more granularity in political identification by allowing for a graded, continuous positioning along a meaningful political dimension. This approach avoids artificially dichotomizing into one-dimensional categories: left vs. right, progressive vs. conservative, liberal vs. non-liberal, or feminist vs. anti-feminist. It also recognizes internal variation within a comprehensive liberal-conservative spectrum. Second, it allows for a more flexible model incorporating different underlying factors, ranging from economic grievances and cultural anxieties to religious beliefs, satisfaction with democracy, or post-materialist traits.

This strategy aligns with recent scholarly debates on the multi-dimensional evolution of youth’s ideological landscape in fragmented, media-saturated political contexts. Political labels have become floating signifiers, with their meaning shaped through discursive struggles rather than fixed ideological blueprints (Lorente, 2019). Shifting from rigid binary approaches to a broader liberal-conservative conception via the political self-placement scale acknowledges these complexities. It aims to capture the political, cultural, and economic dimensions of youth positioning, rather than forcing them into predefined ideological categories.

Reality is not black or white but rather exists in shades of gray. The role of academia is to explore these complexities instead of promoting partisan and media narratives. Adopting this liberal-conservative framework aims to treat ideology not as a timeless doctrine, but as a practical orientation people adopt to make sense of their social and political worlds (Mannheim, 1954 [1936]).

Results

RQ.1. How has the ideological landscape of Spanish youth evolved?

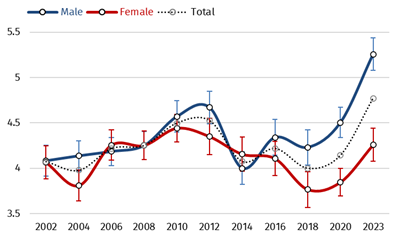

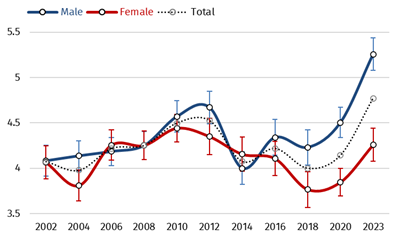

Although the evolution of youth ideology from 2002 to 2023 shows relative homogeneity around a moderate position with most means clustering around 4, a closer examination reveals noteworthy changes over time (Figure 3). In particular, descriptive statistics indicate that while earlier rounds yielded overall mean scores between 4 and 4.5, 2023 exhibits a rightward shift, with the overall mean rising to 4.77 (see Annex I).

This trend is more pronounced among males, whose mean increased from 4.38 across all waves to 5.26 in 2023, compared to females, despite also shifting upward from an overall mean of 4.12 to 4.26 in 2023, remained consistently lower. Hence, gender differences have emerged in the last few years, with young men tending to position at higher values than women. However, the final three rounds reflect at the same time a gender gap and an upward trend among women since 2018.

Figure 3 Mean youth political self-placement evolution by gender

15

Source: ESS 1 to 11. Own elaboration

The factorial ANOVA (Table 2) confirms these patterns, revealing significant main effects for the survey year (F = 3.743) and gender (F = 12.592). There is also a significant interaction between the two factors (F = 1.957), suggesting that the influence of gender on political self-placement varies by year, although the effect is relatively small. The low adjusted R² value indicates that other factors may influence.

Table 2 Factorial ANOVA results. Youth political self-placement by year and gender

16

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F |

|---|

| Corrected Model | 303.312 | 21 | 14.443 | 3.354*** |

| Intercept | 55373.509 | 1 | 55373.509 | 12858.262** |

| ESS_year | 161.171 | 10 | 16.117 | 3.743*** |

| Gender | 54.228 | 1 | 54.228 | 12.592*** |

| ESS_year * gender | 84.264 | 10 | 8.426 | 1.957* |

| Error | 13487.813 | 3132 | 4.306 | |

| Total | 70756.000 | 3154 | | |

| Corrected Total | 13791.125 | 3153 | | |

| R2 = .022 (Adjusted R2 = .015)

|

|

* p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001; n.s. for non-significant differences

|

Moreover, pairwise comparisons and post-hoc tests highlight: i) a general but unsteady rightward shift among youth

17

, ii) greater divergences between genders, especially since 2018, and iii) steadier political positioning among young women

18

. Taken together, the evidence supports H.1.1, indicating a statistically significant rightward shift, and H.1.2 by showing a gender gap within the political evolution landscape.

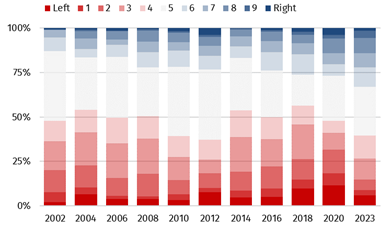

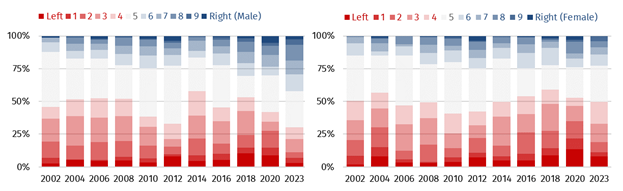

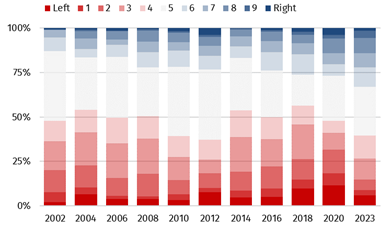

However, the longitudinal trends graphically observed in more detail in the following figures nuance this general trend. Figure 4 illustrates the consolidation of liberal-conservative positions, while those under 5 continue to hold a substantial portion of the political spectrum. Throughout these two decades, the positions Left to 4 constituted approximately 1 of every 2, except for 2010, 2012, and 2023. These two first exceptions are notable. Despite the broad mobilization frame opened by the 15M movement in 2011 due to the political and economic crisis, a significant segment of youth identified with either the “centrist” mode position or a rightward stance.

By the end of the period, although the left-leaning positioning continues to command a considerable presence, there is an established liberal-conservative alignment, with a significant and sustained rise from 13% to 33% in the proportion of those identifying with positions 6 to Right -seven out of ten considering 5 to Right, 2023.

Figure 4 Political self-placement scores compared, 2002 to 2023

Source: ESS 1 to 11. Own elaboration

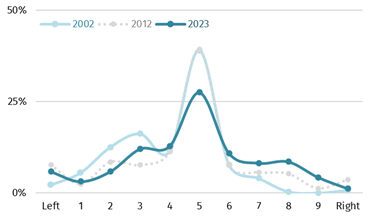

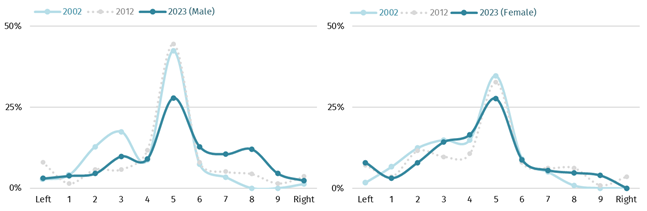

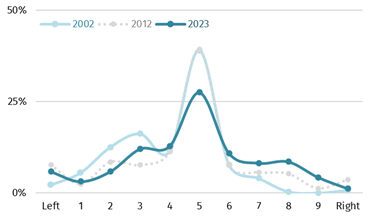

These trends might suggest a gradual move towards a more balanced ideological distribution across the whole political spectrum among young people in Spain, with a steady acceptance of liberal and conservative interests and values. At the turn of the two decades, Figure 5 shows an increasing polarization, with the middle position displaying signs of diversification. Positions 6 to 9 increase and positions 1 to 3 decrease.

Figure 5 Political self-placement scores compared, 2002, 2012 and 2023

Source: ESS 1, 6, and 11. Own elaboration

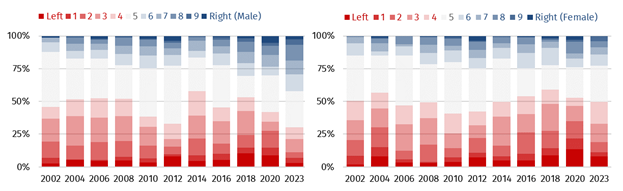

Regarding the division by gender, an overall approach to the graphs in Figure 6 suggests a consolidation of liberal conservatism in young men and women; this trend has been more pronounced among men in recent years. Meanwhile, women maintained a stronger left-leaning trend in contrast to males, with comparatively higher proportions in categories Left to 4, mainly in the last two years.

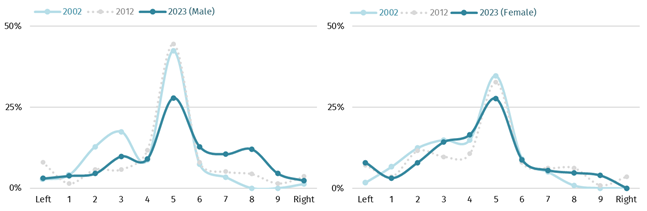

In both cases, the space for moderation seems to have progressively shrunk over the past ten years (Figure 7). Young women show more defined political positions, both in moderate left-wing positions and in the far Left, with reduced identification at the center position and a broader distribution across the spectrum. Meanwhile, among men, the contraction of moderation was accompanied by a notable expansion of positions 6 to 8.

Figure 6 Political self-placement scores compared by sex, 2002 to 2023

Source: ESS 1 to 11. Own elaboration

Figure 7 Political self-placement scores compared by sex, 2002, 2012, and 2023

Source: ESS 1 and ESS 10. Own elaboration

RQ.2. What factors have contributed to a higher identification with liberal-conservative positions in the past two decades?

Table 3 presents a statistical model that analyzes how young people have shifted toward liberal-conservative positions in the political spectrum. An adjusted R² of 0.190 explains approximately 19% of the variance in political self-placement, indicating that the included factors are influential, although other unobserved variables may also play a role. Despite this, the model provides valuable insights into the research questions

19

.

The strongest predictor in the model is religiosity, suggesting that religious individuals have tended to align with liberal-conservative positions over the past two decades. Other significant predictors include disagreement with the idea that the government should reduce income inequality, disapproval of the statement that “immigrants make the country a better place to live,” and support for traditional values, such as following the rules.

Table 3 Linear regression model. Factors contributing to the trend toward liberal-conservative positions in the political continuum

| | β (Std. Error)

| Standardized β |

β positive scores mean:

|

|---|

| Reduce income differences | .369 | (.034) | .169*** |

Disagree

|

| Gays & lesbians free to live life as wished | .173 | (.039) | .072*** |

Disagree

|

| Attitudes towards immigrants | -.166 | (.014) | -.185*** |

Make a better place to live

|

| Do what is told and follow the rules | -.144 | (.024) | -.096*** |

Do not identify at all

|

| Care for nature and the environment | .097 | (.0319) | .048** |

Do not identify at all

|

| Satisfied with life | .058 | (017) | .053*** |

Satisfied

|

| Satisfied with democracy in Spain | .051 | (.014) | .061*** |

Satisfied

|

| Religious | .163 | (.011) | .237*** |

Very religious

|

| Gender | -.199 | (.060) | -.051*** |

Female

|

| Relative household incomes | .167 | (.080) | .032* |

Relatively high incomes

|

| 2004 | -.167 | (.138) | -.025

n.s.

|

Yes

|

| 2006 | .133 | (.140) | .021

n.s.

|

Yes

|

| 2008 | .008 | (.118) | .001

n.s.

|

Yes

|

| 2010 | .382 | (.124) | .058** |

Yes

|

| 2012 | .458 | (.131) | .061*** |

Yes

|

| 2014 | .298 | (.137) | .042* |

Yes

|

| 2016 | .498 | (.147) | .068*** |

Yes

|

| 2018 | .279 | (.150) | .036

n.s.

|

Yes

|

| 2023 | .701 | (.144) | .097*** |

Yes

|

| GDP growth rate | -.030 | (.010) | -.063** |

Positive GDP growth

|

|

Constant

|

3.186***

|

|

| R2

| 0.194

|

|

| Adjusted R2

| 0.190

|

|

| N | 3591

|

|

|

* p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001;

n.s.

for non-significant differences

|

Life satisfaction and satisfaction with Spanish democracy also play a role, with higher levels correlating with a stronger alignment toward liberal-conservative stances. Additionally, being a young man remains significant when other variables are introduced.

The analysis of time-fixed effects suggests that generational and contextual factors influence political positioning. Using 2002 as the baseline, 2010 to 2016 and 2023 show significant shifts toward liberal-conservative positions, while other years exhibit non-significant variations. This indicates that broader political and economic dynamics may moderate these trends.

Additionally, due to an extremely high correlation (r = 0.99) between 2020 and the 10.9% decline in GDP growth due to the pandemic, the former was excluded from the model to avoid multicollinearity issues. Correlation indicated that the variable for 2020 was deemed redundant and provided no additional unique information beyond GDP growth.

In sum and concisely addressing the proposed research questions, disagreement with government intervention to reduce income inequalities (suggesting openness to economic liberal policies( is associated with stronger liberal-conservative positioning, as well as greater satisfaction with the country’s democracy (H.2.1). Regarding traditional values and religiosity (H.2.2), adherence to rule-following and religious beliefs are linked with liberal-conservative stances, coexisting with openness to postmaterialist issues, such as higher life satisfaction (H.2.2). However, skeptical views towards minorities' lifestyles, or on immigration and environmental care (H.2.3) align with the liberal-conservative youth stance.

Economic factors (H.2.4) indicate that young individuals with higher household incomes within their cohort tend to hold more liberal-conservative views during periods of GDP contraction. Lastly, gender differences and the passage of time (H.2.5) continue to shape political placement. Young men exhibit stronger liberal-conservative inclinations, and specific years (2010-2016 and 2023) show significant shifts influenced by broader political and economic contexts.

Discussion

This long-term empirical approach reveals a more intricate interplay of factors than typically acknowledged by media narratives and simplistic overviews. The debate on the so-called “rightward shift” among youth is nuanced, as the findings indicate an unstable yet moderate shift toward liberal-conservative stances, particularly among young men (Figure 3). These shifts tend to coincide with periods of crisis and conservative governments (2010-2016) or moments of intense polarization, such as the pandemic and its aftermath (2020 and 2023)(see Table 3.

Data points to the consolidation of these political arrangements in both young men and women. Although the centrist position (5) has lost presence, the trend is not to self-place in the lowest or highest positions on the Left (0) or the Right (10) (see Figures 5 and 7. Except for a notable percentage of young women on the far Left (0) in 2018, 8.9%, 2020, 13.4%, and in 2023, 7.9%; and the maximum percentage registered on the far Right (10) by young men, 5.1% in 2020, (2.3% in 2023) (see Figure 6,

In general terms, across 2002-2023, Spanish youth who identify with the far Left (positions 0 and 1) on average are three times more likely to do so than those who identify with the far Right (positions 9 and 10), with an average of 9.63% vs. 2.95%, respectively. Terms such as “far-right’s rise” or “fascinization” to describe rightward political shifts among youth are misleading, as very few young people identify with the most extreme positions on the right spectrum. The proportion of young people identifying with extreme left-wing positions is comparable, remaining higher than far right. In recent years, young women have been more inclined to align with radical politics on this ideological spectrum. This is probably due to the identification with the feminist political agenda associated with the left, as suggested in the section on the intersection of theory and method (Figure 2).

At the same time, a steady one-fourth of young women have aligned with liberal conservativism stances since 2016. This proportion increases among men, with one in three in 2023. This percentage is significantly higher when including the centrist position, 70% of young men and 50% of young women (see Figure 6). These data challenge the simplistic narrative that young women are regularly progressive and young men are conservative. Both genders are navigating a complex political spectrum, with young men more likely to adopt liberal-conservative positions (as the model informs( and young women more likely to remain in more leftist stances, but with significant overlap and nuances.

The regression model in Table 3 provides valuable insights into the multidimensional factors driving identification with right-wing politics among different cohorts in the last two decades. For instance, higher life satisfaction has contributed to youth identification with a liberal-conservative agenda, but also religiosity and the importance of adhering to rules. These appear to be complementary traits, including a greater satisfaction with Spanish democracy.

The interplay between increased religiosity and life satisfaction among different youth cohorts identifying with liberal conservatism presents opportunities for further research, warranting a more in-depth exploration. Some scholars in Spain are already working on this line of research (Ruiz Andrés, 2022; Ruiz Andrés et al., 2024). Additionally, the correlation between liberal-conservative identification and greater satisfaction with Spanish democracy and life challenges the notion of a widespread cultural backlash leading to political radicalism and democratic backsliding among young liberal conservatives. Rather than feeling dispossessed, these individuals seem to prefer to confront socio-economic and political uncertainty with a sense of alignment toward prevailing democratic values and institutions (Díez García & Rollón, 2024).

Significant predictors in the model include disagreement with government efforts to reduce income differences, a pessimistic view of immigration, and higher relative household income within their cohort. This triad suggests that those aligning during these two decades with liberal-conservative stances seem to prioritize personal sphere and individual responsibility over public policies aimed at (i) reducing income disparities and (ii) promoting immigration or (iii) environmental issues, which would not be a priority.

This underlying perspective could represent a conscious strategy to cope with the perceived relative socioeconomic status threats these policies might pose, favoring pragmatic approaches to safeguard their interests and values. These are policies they remain skeptical of, and when confronted with the challenges posed by social transformations, their response can be described as practical skepticism-clinging to tradition and modern-era institutions to maintain social stability, organize public affairs, and preserve their social position. This may be described as a balanced or moderate approach to politics, that prioritizes instrumental reason and pragmatism over rigid ideologies (Aron, 1962)

This aligns with the contribution of economic contextual markers to the model, as relatively higher household incomes and periods of economic decline-measured by GDP growth rate-are associated with stronger liberal-conservative tendencies. This is particularly evident when economic difficulties create a sense of insecurity, leading to more conservative responses and identification. The economic context underlines the significance of individual responsibility, personal agency, and meritocracy in navigating these challenges, which further reinforces the prioritization of self-reliance and skepticism toward government intervention, for example, on income redistribution.

On one hand, this perspective ties into Huntington’s (1968) suggestion that individuals facing rapid social change may gravitate toward traditional norms to maintain social stability. Complementarily, young people cohorts identifying as liberal conservatives over the last two decades have not rejected democratic institutions. Instead, they seems to show moderate political positions (Aron, 1962) with a practical balance between tradition, individuality, and modernity (institutions( (Oakeshott, 2017 [1956]) to cope with uncertainty, economic difficulties, and status anxiety (Giddens, 1991; Sennet, 2000; Beck & Beck-Gernsheim, 2001; Bauman, 2001).

Relative socioeconomic status anxiety does not appear to have led to a radical rejection of normative systems or political institutions (Hochschild, 2016; Vance, 2016; Eatwell & Goodwin, 2018; Norris & Inglehart, 2019). In contrast, practical reasons, embodied in liberal-conservative skeptical forms (Oakeshott, 2017 [1956]), may have encouraged the political positioning of different conservative cohorts over the past twenty years.

The alternative thesis proposes that liberal-conservative cohorts are more likely to prefer tradition and the familiar, as these provide a stronger sense of continuity, stability, and guidance for navigating social life. In contrast, unfamiliar or untested ideas often generate uncertainty, especially when new political and cultural frames around “odd topics”-such as gender identity, immigration, or climate change- are perceived as being imposed abruptly and as a source of conflict. Rather than forcing changes through partisan movements or state-driven policies, some of them may be gradually assimilated into the familiar.

Statistical models based on 2022 data from five European countries-focusing on young people aged 15 to 25-reveal that Spanish youth who identify with liberal-conservative positions show a higher degree of tolerance toward gay and lesbian lifestyles compared to their counterparts in France, Italy, and the UK. Additionally, they reveal the non-influence of gender and satisfaction with the functioning of democracy in Spain as predictors of a stronger tendency toward liberal-conservative positions

20

.

These elements warrant further exploration, raising a new research question: How are radical right parties and leaders influencing young people who identify with liberal conservatism? A more de-ideologized approach, rooted in theoretical frameworks from both liberal and conservative traditions-far from stereotypical views consonant with theories and political programs aimed at social transformation-seems to be an excellent starting point to address this.

![]()