Artificial intelligence (AI) systems are and will continue to be extensively utilized for text generation across domains, including scientific research publications. The more quickly academia acknowledges this reality, the greater our capacity will be to adapt to and effectively leverage AI technologies. Researchers now have immediate and virtually cost-free access to numerous AI tools that enable writing in unfamiliar languages, organizing ambiguous concepts into precise paragraphs, reviewing extensive literature within hours, and analyzing quantitative data without statistical software expertise. The advent of generative AI, with ChatGPT leading the transformation, is disrupting established academic structures and competencies-challenging the significance of dissertations, faculty hierarchies, meticulous literature reviews, peer evaluation processes, and traditional writing proficiency.

Nevertheless, a fundamental limitation exists in current AI tools such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude. Generative AI lacks sensory engagement with the external world through social interactions and cannot access human contextualization derived from emotions, cultural frameworks, personal narratives, and intangible human capacities like intuition and empathy. Consequently, AI cannot replace the core function of sociological inquiry: directly engaging with people about their thoughts, behaviors, preferences, and interpreting their perspectives, emotions, and social organizations. Social research extends to realms inaccessible to AI-'the neighborhood corner'-capturing and interpreting the complex interplay between humans and their environments. While AI substantially augments researchers' and academics' capabilities, it simultaneously generates uncertainty by disrupting established work patterns, cognitive processes, and knowledge accessibility.

This article examines AI's impact on research and academic practice by defining and characterizing generative artificial intelligence, presenting research-supportive AI tools, analyzing potential future scenarios based on AI accessibility and acceptance, and proposing strategic responses. Our analysis contributes to emerging discussions concerning the future of research methodologies, scholarly publications, and scientific journal management.

What is generative artificial intelligence

The concept of artificial intelligence (AI) is often employed as a marketing buzzword to enhance technological appeal or drive digital product sales. Our initial AI expectations were shaped by science fiction depictions -self-driving vehicles, humanoid companion robots, or futuristic terminators. Notably, none of these cinematic AI applications have fully materialized- neither truly autonomous vehicles, multifunctional robots, nor time-traveling machines. Instead, the AI that has generated significant media attention, commercial interest, and workforce disruption is generative artificial intelligence, which produces texts, images, audio, and video content.

AI encompasses computational learning and prediction systems that make decisions based on training data and ongoing usage inputs. An autonomous vehicle determines navigation parameters using extensive stored datasets and real-time camera inputs. Similarly, YouTube's recommendation algorithms utilize multi-dimensional data sources -viewing patterns across users, content metadata, engagement metrics- while prioritizing strategic objectives such as maximizing viewing duration through longer videos or promoting higher-quality content with substantial user engagement. However, these systems remain primarily responsive rather than genuinely creative.

Generative AI represents a specialized category designed to create original content across various media formats. Early developmental milestones include Eliza, a natural language processing program from the 1960s that simulated therapeutic conversations. The 1980s witnessed significant advancement in artificial neural networks, which now underpin most contemporary AI systems. A neural network works as an interconnected node system, each performing specific mathematical operations-analyzing word classifications, sentiment patterns, or symbolic relationships. When presented with a task (prompt), these nodes collaborate, transmitting information and combining computational capabilities to generate solutions. Neural networks organize these nodes into specialized layers. The initial layer processes input information, then transmits results to subsequent layers with different analytical capabilities, continuing until the final layer produces the output response. Similar to human neurological development, neural networks improve performance through experiential learning, adjusting connections and mathematical functions as they process additional data. Multi-layered neural networks enable deep learning - a machine learning subset characterized by complex task capabilities through extensive hierarchical processing structures.

The transformer architecture, introduced by Google researchers in 2017, revolutionized neural network design by implementing an “attention” mechanism allowing selective focus on contextually relevant information. This innovation overcame previous architectural limitations in language processing, enabling parallel computation and more efficient handling of extended data sequences. GPT (Generative Pretrained Transformer) models, including ChatGPT, employ modified transformer architectures with numerous processing layers trained on vast textual corpora to identify intrinsic linguistic relationships. These systems excel in natural language processing applications including text generation, translation, information retrieval, and content classification. ChatGPT's output decisions derive from its training dataset parameters and input instructions, generating probabilistic text continuations. The stochastic nature of ChatGPT explains its variable responses to identical prompts. Rather than consistently selecting highest-probability terms, it samples from probability distributions when determining word sequences. Additionally, language models incorporate adjustable “temperature” parameters that regulate generative randomness-higher settings produce more creative, diverse outputs while lower settings generate more predictable, structured content.

Generative AI content has become effectively undetectable. Despite the emergence of detection applications designed to differentiate between human and AI-generated text, the rapid adaptability of AI tools consistently overcomes identification methods. Attempting to restrict academic ChatGPT usage through detection mechanisms represents an unwinnable challenge, particularly given the availability of sophisticated paraphrasing applications that produce untraceable content. Rather than implementing technological barriers against this academic paradigm shift, a more productive approach involves developing comprehensive understanding of both the capabilities and limitations of these powerful systems.

AI tools for research

Researchers face the challenge of mastering multiple competencies: research design methodology, theoretical conceptualization, quantitative and qualitative analytical techniques, interpretive frameworks, innovative approaches, and advanced written communication skills-including English language proficiency. This comprehensive skill set represents an exceptionally high standard that few scholars fully attain across all dimensions. Traditionally, researchers have addressed these challenges through strategic outsourcing, either by contracting specialized services or incorporating additional collaborators with complementary expertise.

While AI tools do not offer comprehensive solutions to all research challenges, they significantly expedite specific tasks such as enhancing writing in non-native languages or facilitating understanding of sophisticated theoretical frameworks and complex statistical outputs. Integrating AI into research workflows allows scholars to allocate greater cognitive resources toward interpretive analysis, critical reflection, and conceptual innovation, rather than focusing on stylistic phrasing, exhaustive literature identification, or database management. However, excessive reliance on AI technologies potentially compromises fundamental cognitive capabilities, potentially reducing critical reading engagement or fostering technological dependency. The academic discourse surrounding AI's benefits and limitations has intensified, yet consensus regarding appropriate implementation strategies remains elusive.

Research-relevant AI tools can be categorized into five functional domains: text generation, literature review facilitation, reading and summarization assistance, data analysis and visualization, and manuscript evaluation systems.

The most widely recognized and utilized text-generating AI systems are conversational interfaces such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude. These platforms generate content with customizable stylistic parameters, tonal variations, and language preferences, though they occasionally produce “hallucinations”. In AI terminology, hallucination refers to the generation of plausible but factually incorrect or contextually inappropriate content. When soliciting ChatGPT's assistance for scientific manuscript preparation, the system might fabricate non-existent citations, authors, or institutional affiliations. However, specialized scientific writing tools offer enhanced accuracy-notably Scite and Elicit. Scite represents a generative AI text platform that responds to queries by incorporating verifiable citations and references to published research. Unlike more general AI systems, Scite conducts targeted searches for citations that either substantiate or challenge specific arguments. While limited to producing concise text segments of three to four paragraphs, this constraint enables it to function effectively as an evidential complement to scholarly manuscripts.

Literature review processes benefit from various specialized AI tools. Elicit stands as a comprehensive research assistant platform, offering multifaceted functionality: identifying relevant scholarly publications, synthesizing principal findings, generating draft paragraphs, operationalizing theoretical constructs, proposing causal relationships, and formulating research questions. While the training methodology for general platforms remains proprietary, Elicit's knowledge base explicitly incorporates scientific literature. This comprehensive functionality effectively positions Elicit as a simultaneous collaborator, co-author, and research assistant.

Inciteful provides another valuable literature review resource with a distinctive methodological approach. Unlike conventional academic search engines such as Scopus or Google Scholar that rely primarily on keyword matching, Inciteful employs citation pattern analysis. Beginning with researcher-selected source materials, the platform examines citation networks across referenced publications. This approach generates a sophisticated interconnected article network, identifying conceptually similar publications, seminal works, comprehensive reviews, highly-cited contributions, recent developments, influential authors, and relevant journals.

Reading comprehension and summarization tasks are enhanced through platforms like SciSpace, which processes and responds to queries regarding uploaded scholarly materials. As its promotional tagline indicates -“The fastest way to read and understand scientific literature”- this AI system provides comprehensive summarization, targeted question answering, and explanatory analysis of statistical tables and mathematical formulations. While traditional critical engagement with a scholarly article typically requires significant time investment, this technology enables rapid comprehensive document processing.

The analytical domain includes specialized tools such as Code Interpretation, a ChatGPT plugin capable of executing statistical and network analyses on structured datasets. ChatGPT's modular architecture incorporates supplementary functionality through add-on plugins-auxiliary components enabling diverse operations including mathematical computation, bibliographic searching, and multimedia interaction. Code Interpretation facilitates natural language interaction with databases, allowing users to request specific analytical operations and visualizations without programming expertise. For instance, researchers can request complex statistical procedures such as “perform multiple linear regression with this dependent variable and these explanatory variables”, and the system will generate both regression coefficients and interpretive analysis. This capability extends to various statistical methods, including factorial analysis, ANOVA, and network analysis with corresponding visualizations and centrality metrics (Cárdenas, 2023). This technological advancement represents a paradigm shift in quantitative analysis and methodology instruction, potentially reorienting pedagogical emphasis from software operation toward results interpretation.

Peer review using AI?

If researchers utilize AI tools-and they will-should scientific journals incorporate artificial intelligence in their evaluation processes? Would scholars accept AI-assisted assessment of their manuscripts? Various AI-based systems, including those employing neural networks, are already integrated into journal workflows for plagiarism detection, reviewer identification, statistical validation, structural analysis, and contribution assessment. But can an AI tool act as a peer reviewer?

Previous empirical investigations support measured implementation of these technologies. Checco et al. (2021) demonstrated that AI assistance in peer review processes is particularly effective for evaluating formatting adherence and plagiarism detection, moderately valuable for assessing article relevance, but considerably less reliable for evaluating methodological rigor, conceptual originality, and scholarly contribution. Yuan et al. (2022) developed a specialized natural language processing model that generated more comprehensive reviews but with diminished constructive value due to inadequate critical engagement with substantive limitations. More recently, AcademicGPT emerged as a specialized assessment tool evaluating argumentative strength, conceptual coherence, and intellectual originality. As a GPT-derived application, it offers particular utility for critiquing scholarly writing quality and conceptual clarity.

Critics of AI implementation in scholarly assessment highlight significant concerns regarding large language models (LLM), particularly their operational opacity-training datasets remain undisclosed-and inherent biases derived from historical data patterns. Conversely, proponents advance two principal arguments. First, AI systems dramatically reduce evaluation timelines through computational efficiency that far exceeds human processing capabilities. Second, human reviewers inevitably possess partial or potentially outdated domain knowledge, whereas specialized AI systems can potentially conduct more comprehensive evaluations by leveraging extensive scientific databases.

The scholarly manuscript review process presents well-documented challenges: it requires substantial time investment, depends heavily on professional altruism from faculty and researchers, and relies on inherently subjective assessment criteria. Submission volumes have increased dramatically across disciplines-the Spanish Journal of Sociology (RES) experienced nearly 200% growth from under 100 manuscript submissions in 2017 to approximately 300 in 2023.

Editorial workflow typically involves initial quality screening followed by peer review for potentially publishable manuscripts. Decision timelines frequently extend to two months, with final acceptance requiring 3-5 months from initial submission. These extended timelines create significant professional challenges when employment opportunities or compensation structures depend on publication metrics. Journals maintain exceptionally low acceptance rates-only 10-17% of submissions receive favorable decisions in prominent publications. The combination of intense competition, protracted evaluation periods, and stringent quality standards frequently generates frustration within the research community.

This environment has facilitated the emergence of alternative publication models exemplified by publishers like Frontiers or MDPI journals such as the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (IJERPH) and Sustainability, which offer expedited review processes (10-15 days), higher acceptance probabilities, and rapid online publication (20-30 days) following payment of substantial processing fees (approximately 2,500 euros). IJERPH notably became Spanish scholars' predominant publication venue during 2020-2022, with MDPI receiving an estimated 10 million euros from Spanish authors' publication fees. However, quality concerns emerged when Web of Science removed IJERPH from its index in 2023 for failing to meet core quality standards. Similarly, Repiso et al. (2021) documented that most Sustainability articles by Spanish authors lacked substantive connections to sustainability subject matter.

The remarkable market success of journals like Sustainability highlights systemic challenges in contemporary academic publishing: evaluation systems that prioritize publication quantities and citation metrics for professional advancement, continued reliance on faculty altruism for peer review, minimal professional recognition for review contributions, increasing manuscript submission volumes, difficulties balancing review responsibilities with teaching and administrative obligations, and limited scholarly impact. Research indicates that one-third (32%) of social science articles indexed in Web of Science receive zero citations within five years of publication (Larivière et al., 2009). Beyond citation metrics, sociological research receives minimal mainstream media coverage (Navarro Ardoy et al., 2021). Knowledge transfer mechanisms between academic institutions and broader society require substantial improvement. Excessive emphasis on traditional article metrics potentially undermines alternative knowledge dissemination channels including practical applications and media engagement.

Do generative AI tools offer viable solutions to these pervasive challenges in scientific publishing? Could generative AI serve as the transformative catalyst for reimagining scholarly communication? The implementation of AI in scientific review processes remains controversial, with various institutions advocating regulatory frameworks. While the European Union's comprehensive AI legislation does not specifically address research applications or manuscript evaluation, it categorizes AI-based academic performance assessment as “high-risk”, thereby imposing stringent requirements for quality assurance, transparency protocols, and human oversight mechanisms (Eur-Lex, 2021).

Analysis of potential future scenarios

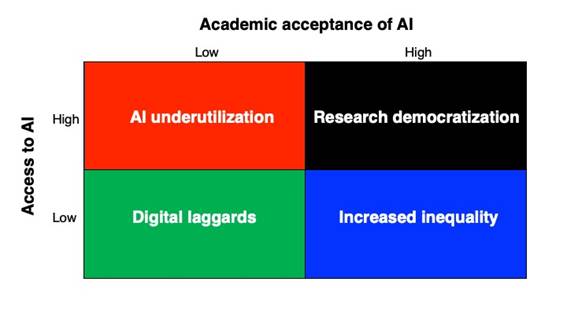

In recent years, numerous academic symposia and workshops have examined the multifaceted challenges AI presents to higher education and research institutions. Given the accelerating pace of technological advancement, developing forward-looking perspectives on AI's academic trajectory offers valuable strategic insights. Scenario analysis provides a structured methodological approach for anticipating potential developments (Rodríguez Díaz, 2020). By intersecting two critical variables, this technique generates four distinct outcome configurations. To conceptualize AI's future research impact, we examine two fundamental dimensions: access to artificial intelligence technologies and their acceptance within academic communities.

Access to AI Tools

The “access to AI tools” variable encompasses researchers' and academics' capacity to incorporate AI technologies into scholarly activities. This variable can be dichotomized into high and low access.

High access emerges when AI technologies become widely available to the research community at minimal cost, with limited regulatory constraints or institutional barriers impeding academic implementation. This environment facilitates widespread integration of AI across diverse research contexts.

Low access materializes when stringent regulations restrict AI applications in research contexts, whether motivated by ethical considerations, privacy protections, or security imperatives. These regulatory frameworks may operate at multiple levels: macro (legislative/governmental), meso (institutional/associational), or micro (journal/publication). Additionally, access remains constrained when economic barriers create prohibitive costs, particularly disadvantaging researchers at resource-limited institutions. While baseline versions of platforms like ChatGPT offer limited free functionality, advanced capabilities typically require substantial subscription commitments-approximately 20 euros monthly for premium ChatGPT access. Similarly, Midjourney, a sophisticated AI image generation platform, initially provided free services before transitioning to a 10-euro monthly fee structure. This pattern raises legitimate concerns about strategic dependency cultivation by AI developers, potentially mirroring market penetration strategies employed by e-commerce platforms like Amazon or Aliexpress.

Academic acceptance of AI

The “acceptance” variable reflects the academic community's technological literacy regarding AI systems and faculty willingness to incorporate these technologies into regular scholarly activities. This variable proves crucial because meaningful AI integration depends not only on tool availability but fundamentally on researchers' attitudinal orientation toward these technologies.

High acceptance develops when researchers demonstrate sophisticated understanding of AI capabilities and express willingness to incorporate these tools into research methodologies. This receptivity may result from comprehensive technological training programs, recognition of AI's research efficiency benefits, or institutional cultures that actively encourage technological innovation.

Low acceptance manifests when academics exhibit limited AI knowledge and demonstrate resistance toward integrating these technologies into established research practices. This resistance may stem from inadequate professional development opportunities, perceptions of AI systems as excessively complex, or conservative institutional cultures exhibiting generalized resistance to methodological innovation.

The intersection of these dimensional categories generates four distinct future scenarios (Figure 1):

Research democratization: high AI access and high acceptance

In this optimistic scenario, AI tools achieve widespread availability while academics demonstrate both proficiency and willingness to integrate these technologies. Research activities become simultaneously accelerated, multiplied, and democratized. The scholarly process accelerates as publication timelines compress, enabling increased manuscript production within compressed timeframes. Research output multiplies as scholars publish across linguistic boundaries, with traditional language barriers no longer impeding global knowledge dissemination. Democratization manifests through expanded diversity within research communities: traditional entry barriers diminish, enabling broader participation in knowledge advancement and potentially generating greater topical and methodological variation. International collaborative networks likely expand through enhanced capabilities for multilingual remote collaboration.

Scientific journals experience substantial increases in submission volumes, necessitating expanded staffing and resource allocation to manage manuscript influxes-potentially accelerating AI adoption in peer review processes and fostering emergence of rapid-evaluation publication models. Article production costs may decrease through technological efficiencies. Given the increased volume of rejected manuscripts, alternative dissemination channels such as preprint repositories gain enhanced significance. The evaluative weight of traditional research articles may diminish in personnel selection, promotion decisions, compensation determinations, and funding allocations as the partially automated nature of research and publication processes becomes widely recognized. This paradigm shift could catalyze development of alternative research evaluation frameworks emphasizing societal impact, knowledge transfer effectiveness, and contributions to educational advancement, policy development, or social transformation.

AI underutilization: high access but low acceptance

This scenario features widespread AI availability juxtaposed against persistent academic resistance. AI adoption remains limited and concentrated within a small researcher cohort. While commercial sectors and broader society embrace AI technologies, academic institutions maintain conservative resistance to methodological innovation. This divergence potentially reinforces perceptions of universities as anachronistic institutions with diminishing societal relevance.

A significant performance gap emerges between AI-adopting academics and the non-adopting majority. Scientific journals receive disproportionate submissions from the limited group of AI-utilizing researchers, who gain competitive advantages in high-impact publication venues, thereby exacerbating academic stratification. Without AI integration in editorial management systems, journals continue experiencing traditional challenges: protracted peer review timelines and elevated production costs. Moreover, both publication venues and researchers forgo opportunities for broader knowledge dissemination through AI-enhanced formats such as automated research summaries, educational multimedia content, or audio adaptations.

Increased inequality: low access but high acceptance

Despite widespread interest in AI applications, restricted access resulting from prohibitive costs and regulatory constraints creates a bifurcated academic landscape. AI adoption concentrates within well-resourced institutions possessing both financial capacity and regulatory flexibility. Academics in resource-constrained regions or operating under stringent regulatory frameworks struggle to maintain competitive parity with AI-enhanced research enterprises. Research community diversity diminishes as elevated entry barriers restrict participation in knowledge generation processes.

High demand coupled with access limitations potentially catalyzes academic activism and advocacy for regulatory reform. Early-career researchers and faculty at resource-limited institutions experience publication disadvantages. Restricted access potentially results in high-impact publication dominance by affluent institutional actors. Strategic cross-institutional collaborations might emerge specifically to share AI resources and access privileges. Underground economies for AI tool subscriptions could develop, introducing additional cybersecurity vulnerabilities. Inequality extends to journals' financial capacity to implement AI systems, creating substantial disparities in review efficiency and production timelines.

Digital laggards: low access and low acceptance

With simultaneous constraints in both access and acceptance dimensions, AI adoption in academia remains extremely limited. Methodological innovation stagnates as few academics possess both required resources and motivational willingness to reimagine established research processes. Acceptance deficits foster generalized technological skepticism, focusing discourse primarily on ethical hazards and privacy concerns, thereby reinforcing resistance to AI implementation.

Academic institutions maintain traditional pedagogical approaches as faculty predominantly lack both AI access and acceptance. University reputations potentially suffer in comparison to sectors embracing rapid technological transformation. Most scientific publications continue traditional editorial and peer review methodologies, potentially becoming increasingly disconnected from evolving research practices in adjacent sectors.