Are they finally talking about European Politics? Analysis of the issues discussed by the parties in the 2019 EP election as signs of politicization

¿Hablan por fin de política europea? Análisis de los temas tratados por los partidos en las elecciones al PE de 2019 como evidencias de politización

ABSTRACT

Recent studies point to a progressive politicization of the European Union, after years of being considered a project of the political elites that received little attention from European citizens. The aim of this article is to find evidence of the progress in the process of politicization of the European project. For this purpose, an analysis of all the tweets published during the 2019 election campaign by all political parties in Germany, France, Italy and Spain has been carried out. The topics addressed and the number of parties speaking on those topics are studied, in order to trace two of the elements necessary to consider an issue politicized: its visibility and the diversity of voices. The article addresses an issue that has been the subject of previous research using a new methodology and at a particularly relevant moment in history; the first elections held after Brexit. The research provides results that can be interpreted as evidence of a growing politicization of EU policy on issues such as climate or social policy.

Keywords: European Parliament, Twitter, salience, politicization, European Union, social media, political communication.

RESUMEN

Estudios recientes apuntan a una progresiva politización de la Unión Europa, después de que durante años se considerase un proyecto de las élites políticas que apenas recibía atención por parte de la ciudadanía europea. El objetivo del presente artículo es encontrar pruebas sobre el avance en el proceso de politización del proyecto europeo. Para ello, se ha realizado un análisis de todos los tuits publicados durante la campaña electoral de 2019 por todos los partidos políticos de Alemania, Francia, Italia y España. Se estudian los temas tratados y el número de partidos que hablan sobre esos temas, para rastrear dos de los elementos necesarios para considerar un asunto politizado: su visibilidad y la diversidad de voces. El artículo aborda una cuestión que ha sido objeto de investigaciones anteriores empleando una nueva metodología y en un momento especialmente relevante de la historia; las primeras elecciones que se celebran tras el Brexit. La investigación aporta resultados que pueden ser interpretados como evidencias de una creciente politización de la política comunitaria en asuntos como la política climática o social.

Palabras clave: Parlamento Europeo, Twitter, visibilidad, politización, Unión Europea, medios sociales, comunicación política.

1. INTRODUCTION [Up]

Over the past decades, much research has been carried out on the process of politicization of the European Union. Initially, it was considered to belong only to the realm of the political elite and received little attention from society at large. Already many years after the first European Parliament elections were held, many studies confirm the validity of the so-called “second-order election” model, according to which European elections remain secondary to national elections (Hix and Marsch, 2007; Van der Brug et al., 2016). That is, citizens vote in Europe in a national key. This is related to citizens’ weak connection to EU policy issues and, to a greater or lesser degree depending on the country, translates into disaffection towards participation in European elections.

Some more recent studies point to a process of progressive politicization of the EU, albeit incomplete and full of gaps. These studies highlight the need for further research along these lines as the process of European integration continues and intensifies. Taking this into consideration, it might be felt that election campaigns would be a good time to contribute to the politicization of the European project, although so far it seems that this opportunity has not been taken advantage of. Previous research points out that political parties barely discuss the content of European policies during election campaigns, “making it difficult for voters to give policies an electoral mandate” (Van der Brug et al., 2016).

The present study examines the contribution of political parties to the politicization of the European Union during the 2019 elections. To this end, the study focuses on the issues regarding the EU most frequently raised during the May 2019 European Parliamentary election campaign, bearing in mind the political priorities defined by the European Union. Are issues related to EU political activity politicized? Are social issues politicized? Or is politicization, as some previous studies have found, linked to issues relating to the wider debate on the degree of European integration? What differences in the process are detected between countries?

The study investigates the issues discussed in the EU Parliamentary election campaign by analysing social network based political communication, tracking the Twitter accounts of the total of 51 parties represented in the European Parliament from the four countries with the greatest demographic weight in the European Union: Germany, France, Italy and Spain. From their analysis of both the issues “raised by the parties” and the “agenda” of the elections, previous investigations have concluded that during the electoral period, political parties are the main agenda-setters. It is these parties that set the media agenda, and not the other way around (Jansen et al., 2019). Twitter is one of the preferred channels for political parties to communicate ideas and priorities. The issues then raised by the media and the various “frameworks” built into their discourse influence the process by which the public interpret the elections, not merely absorbing them passively, but actively seeking out alternative information sources (Shamir et al., 2015).

The present study further contributes to research on this issue in a particularly relevant moment in history: the first EU elections following the start of the Brexit process. According to several analysts, this process could be expected to accentuate debates regarding the advisability of belonging to the EU within other countries with Eurosceptic parties or allow them to move past such debates and unite the community bloc by demonstrating the costs of being outside the Union.

Following the link made by Hutter and Grande (2014), between increases in the degree of politicization and peaks in the debate on integration (meaning Eurosceptic parties have paradoxically contributed to the construction of Europe), it is now possible to assess whether closing the Brexit chapter will help to politicize other issues within the EU, such as the green agenda. De Wilde et al. (2014) found that “citizens express themselves clearly as more critical of the EU than party actors, with party actors making more affirmative European arguments and citizens making more diffuse eurosceptic arguments”. Recently, data from the 2019[1] Eurobarometer survey reflected that up to 45% of citizens have a positive image of the EU (compared to 17% who have a negative image) and that 63% are optimistic about the future of the Union. There is also a growing perception of the importance of the voice of citizens in the EU, with a majority of Europeans (56%) considering that their voice counts, a figure that increases to in excess of 80% of citizens in countries such as Sweden or Denmark. This trend should contribute to overcoming the idea that the EU project is democratically deficient and a “matter for political elites”. “If citizens become aware that Europe can do something for them in the short term and not just the long term, then elections to the EuropeanParliament would be more than mere contests to judge whether voters care about Europe, but rather elections about what European citizens really want” (Rauh, 2015). The politicization of the day-to-day affairs of European politics would make advances in that direction possible.

In order to contribute to the body of academic research on the politicization of the European project, this article presents a review of previous research focused on European elections from the disciplines of Political Science and Political Communication, that serve as a state of the question and review the concept of politicization on which the research is based. The research questions are then posed, and the methodology detailed and justified. Finally, the main results and the most significant conclusions are presented.

2. EUROPEAN ELECTIONS, NATIONAL ELECTIONS? [Up]

Several authors (Van der Brug et al., 2016) have investigated what citizens understand to be the differences between national and European elections. Some authors highlight the difficulty of equating national elections with elections to the European Parliament, due to the complexity of the European governance framework (Van der Brug et al., 2016). Until 2014 there was no connection between elections to the European Parliament and the composition of the European Commission, its main executive body, with many of the decisions ultimately taken by the European Council, made up of the heads of state of the different member countries, elected in their respective national elections.

Until 2007, most research into European Parliament elections confirmed that it was necessary to understand these elections in a national context (as a form of midterm before each countries’ general elections) rather than a truly European one. Although evidence was found that a party’s position on the EU might have some effect on its gains or losses of votes (Hix and Marsh, 2007). According to these authors, it cannot be said that the second order model is fully valid today, but Europe remains a minor element.

A previous study, focusing on the 2004 elections that took place after 10 new countries joined the EU, argued that although the second-order European election model still had considerable appeal, over time the growing divergence of the patterns of participation in 2004 suggested that European issues might have a significant influence on voting in some countries, thus invalidating a reading of the results or participation in a purely national context. “Turning to the bigger picture, there has been a dramatic increase in the power of the European Parliament in the last two decades, and there is growing evidence that politics inside this assembly is highly competitive and partisan” (Hix et al., 2006).

Braun et al. (2016) found evidence that European issues are much more salient in the partisan offer than what it is often assumed, supporting the idea that European issues are increasingly playing a more important role. Most studies, however, do not reflect these findings. After six rounds of direct elections to this institution, the “electoral connection” between citizens and MEPs remains extremely weak. “Citizens do not primarily use European Parliament elections to express their preferences on the policy issues on the EU agenda or to reward or punish the MEPs or the parties in the European Parliament for their performance in the EU. Put another way, European Parliament elections have failed to produce a democratic mandate for governance at the European level, and there are few signs that further increases in the powers of the European Parliament would be sufficient to change this situation” (Hix and Marsh, 2007).

In their analysis of the 2014 elections, Schmitt and Toygür (2016) concluded that national electoral cycles are still very influential in European elections, thus validating the model of second-order elections. Van der Brug et al. (2016), analysing 11 articles of a special edition on those same elections, concluded that despite the attempts of the EU institutions to make the 2014 elections different, it had not been achieved. The introduction of the Spitzenkandidat had not been enough.

Along similar lines, Adam et al. (2017), linked the visibility of campaigns about European issues with the degree of polarization of national politics, stating that “Media coverage and party communications on EU issues differ extensively in our seven EU member countries. The salience of EU issues in political campaigns is linked to the levels of polarization”. For their part, Jansen et al. (2019) consider that conflicts reduce the visibility of Europe related issues, stating that “The absence of conflict enables campaigning by all parties on EU issues and high levels of conflict lead to more nation-centred campaigns” (Jansen et al., 2019). Therefore, a scenario in which national policy is less polarized would be more conducive to the emergence of EU issues.

3. SHALL WE TALK ABOUT EUROPEAN POLITICS?[Up]

The concept of politicization has been approached from academia in the field of political science. De Wilde (2011) understands it to be a process of increasing polarization of opinions, interests or values and the extent to which they publicly advance towards the formulation of policies within the EU. Adam et al (2017) establish three necessary conditions for politicization of the European question within a country to be present (a) salience is attached to the issue of EU integration; (b) parties enter a common debate about the same aspects of EU integration and (c) polarized opinions are voiced. Adam et al. (2017) link the strategic behaviour of parties to the politicization of the EU within a country as follows. Firstly, a party makes a strategic decision whether to address the broader issue of EU integration, or not (in effect silencing it). Second, the party selects specific aspects within the broader issue of EU integration, decides what position to adopt and whether when discussing the issues to mention their direct link to the EU.

The present research draws from the similar approaches to the concept of politicization proposed by Hutter and Grande (2014) and Adam et al. (2017). According to these authors, there are three dimensions to politicization: the “salience” of an issue or its visibility in the public debate, the broadening of the debate on that issue to include different actors (not just political parties, but also organizations and civil society), and a polarization of opinions. Hutter and Grande (2014) agree with Green-Pedersen (2012) in that the most basic dimension in the debate about politicization is the first, the visibility or “salience” of the issue, in which political parties play a decisive role.

As pointed out above, various studies have found that the politicization of the EU, although growing, is still incomplete and contains many gaps. Messages transmitted to the public by political parties exert a great influence on participation and in the orientation of the vote (Van Spanje and De Vreese, 2014). Such messages are fundamentally focused on legislative issues and on the distribution of powers among the countries of the European Union (Grill and Boomgaarden, 2017). A study focused on Twitter highlights that, despite signs of a transnationalisation of the debate, nothing approaching a common European public sphere exists on social networks. To date, debates on EU issues in individual countries, using local hashtags, remain dominant (Nulty et al, 2016).

Political parties are important actors in the emergence of a new sphere of common public communication resulting from integration sought since the emergence of mass digital communication (Schlesinger, 1999). This is not only due to their influence on public opinion, especially during election campaigns, but above all because of the qualitative improvement in the production and digital circulation of messages to voters. To date, only the fundamentals of European integration have achieved political relevance for most citizens, while the day-to-day activities of the EU remain largely non-politicized (Hurrelmann et al., 2015). Election campaigns are a good moment for a comprehensive process of politicization to occur, as it is during such campaigns that political parties attempt to reach out to the public.

This study aims to contribute to the investigation into the politicization of the European Union by means of an analysis of tweets published by political parties.

Previous research found that peaks of politicization occurred at the following times: when transfer of sovereignty from individual states to the EU required approval, when it came to advancing towards greater integration, especially in countries with a deeper tradition of Euroscepticism and reluctance to commit to closer political unity such as the United Kingdom, during the signing of the Maastricht and Lisbon Treaties, and also during the crisis in the Euro zone (Hutter and Grande, 2014). The increase in politicization that accompanied the rise of Euroscepticism was also noted in the 2014 elections (Van der Brug et al., 2016).

Analysing the 2009 elections, De Wilde et al. (2014) conclude that online media tends to amplify diffuse euroscepticism while pro-European arguments are less likely to become salient on the Internet, and they argue that “all this constitutes a major challenge to those who would like to transform the EU while taking public opinion about the EU polity seriously”.

The 2014 elections were a turning point for various reasons: the introduction of the Spitzenkandidat, the context of economic crisis and the growing Euroscepticism in many countries. However, studies such as those of Schmitt and Toygür (2016) found that during the EU elections the national electoral cycle retained significant influence. Thus, despite signs of growing politicization they could still be understood in terms of second-order elections.

Of the EU related topics, only the fundamental issues of integration and positions in favour of or opposed to membership made gains in terms of communication space, while the day-to-day activities of the EU remained largely non-politicized (Hurrelmann et al., 2015).

Research by Fazekas et al. (2020) on 2014 elections supports the idea of limited EU issue expansion and, studying interaction between candidates and public, found that the public, on average, was somewhat less responsive to EU issues in comparison to non-EU issues. They also pointed out that “EU content presented in an engaging manner is a rare sight in most countries: politicians use less engaging communication style when talking about EU issues”.

Research conducted by Nulty et al. (2016) found that the debates on how to deal with the financial crisis in the eurozone, migration policies and other regulatory issues, combined with the introduction of Spitzenkandidat, might have awakened the “sleeping” giant of EU politics (Van der Eijk and Franklin, 2004) as a political issue (Nulty et al., 2016). Despite not being able to confirm the emergence of a common European public sphere, as parallel discussions on European topics predominated, these authors did find signs of a transnationalization of the debate.

The aim of this research, and more specifically of RQ1a and RQ1b, connects with the distinction proposed by Braun et al. (2016) between constitutive and policy-related European issues. These authors argue that, in contexts characterized by less polarized conflicts over European integration, all parties are more likely to emphasize discussion about EU policies.

Brexit turned the 2019 elections into a key moment. International policy analysts state that when this chapter is closed it will be time for the remaining countries to decide what kind of EU they want. This context may lead policy-related European issues gain visibility over constitutive-related European matters. By necessity, this will occur in an international scenario of increasing complexity and challenges such as climate change that have led the European Union to make the transformation to a green economy a political priority, a priority that has not changed despite the crisis caused by Covid-19, since the aid fund to countries is conditional on investments in the green and digital economy.

The current research takes up some issues addressed in previous research but does so in the context of a changed Europe and employing different methodology: an analysis of all the tweets published by all the political parties of the 4 countries with the most demographic weight among the 27 member states to answer the following questions:

RQ1a Following Brexit, are there signs of the politicization of other more specific issues beyond the integration debate in the 2019 elections?

RQ1b: What issues have become politicized during the campaign in the countries studied?

The adoption of an issue by a larger number of authors (despite them all being political parties) could be understood as evidence of a degree of politicization of the terms employed. With this in mind, to pay attention to the diversity of voices speaking on the same topic, we ask ourselves:

RQ2: How many different parties have talked about the most frequently debated issues during the election campaign?

4. METHODOLOGY[Up]

Various methodological approaches have been employed in research into the degree of politicization of the European project. In their 2016 study, Schmitt and Toygür analysed the results of national and European elections, comparing the votes obtained by political parties in both elections. In addition to their strategies in the face of the Eurosceptic challenge, Adam et al. (2017) investigated the contribution of pro-European parties to the politicization of the EU, by means of an analysis of party press releases. Adam et al. (2017) analysed what strategies were adopted, if issues were silenced or built up by putting on them on the table, and in the case of the latter, what positions were taken. There is also recent research on the degree of polarisation in citizenship, such as the work of Serrano-Contreras et al. (2020), which looks at user interactions in news-related videos on YouTube.

Research such as that carried out by Nulty et al. (2016) or Fazekas et al. (2020) used Twitter as a corpus to investigate the issues voiced and the communication patterns of the parties or political actors during the 2014 election, a time in which there was an increase in political communication. The present research is also based on the analysis of political party tweets and focuses on what issues are made visible in relation to the European Union within the four countries studied in the weeks prior to the 2019 elections.

How political parties communicate with their audiences has undergone significant changes over the last quarter of a century, becoming a form of hybrid communication (Chadwick, 2013; Hamilton, 2016; Wells et al., 2016) with new narratives (Gander, 1999; Jenkins, 2003; Shin and Biocca, 2017) and languages (García-Orosa and López-García, 2019) and above all, being used to further the goal of citizen engagement. Social networks, especially Twitter, have occupied a prime position in this process of change (Dodd and Collins, 2017). Twitter has become the main channel of political communication in election campaigns (Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripollés, 2018) and one of the most analysed (Dodd and Collins, 2017; Gálvez-Rodríguez et al., 2018; Obholzer and Daniel, 2016).

Twitter stands out as the primary platform for the dissemination of political ideas (López-Meri et al., 2017; Nulty et al., 2016). Not only do political parties speak directly to their voters on Twitter, albeit with a reduced level of interactivity (Aragón et al., 2013), but we also find tweets being used as sources for political journalism (Justel-Vázquez et al., 2018).

It is during election campaigns that social networks have the maximum relevance for political parties, with candidates making greatest use of them to offer information about their campaign, activities, and links to their websites (Jungherr, 2016).

From the analysis of both the issues “raised by the parties” and the “agenda” of the elections, previous investigations have concluded that during the electoral period, political parties are the main agenda-setters. It is these parties that set the media agenda, and not the other way around (Jansen et al., 2019). The issues then raised by the media and the various “frameworks” built into their discourse influence the process by which the public interpret the elections, not merely absorbing them passively, but actively seeking out alternative information sources (Shamir et al., 2015).

Taking this scenario as a starting point, Twitter is therefore a good channel to use to examine the contribution of political parties to the politicization of the European Union in the latest European Parliamentary election campaign held in May 2019.

The research analyses the frequency of words used by the parties in their tweets. The database is composed of 49.101 tweets published on Twitter the month prior to elections, from April 26th to May 26th, by the 51 political parties of Spain, Germany, Italy and France with a presence in the European Parliament, the four countries with the most demographic weight in the European Union (leaving aside the United Kingdom as it was immersed in Brexit). Data extraction took place on June 7th, using R package twitteR, which allowed the extraction of the last 3.200 tweets for each Twitter account. All tweets were saved to ensure that it will be possible to review or replicate the study, even if the material is modified, or no longer available online.

A first data cleaning consisted of discarding tweets that did not refer to European policies —as, in Spain, the European elections coincided with local and regional elections, the parties were immersed in two simultaneous electoral campaigns, so it was necessary to discard all the messages not related to the European elections. To this end, only tweets containing explicit references to Europe in each of the languages of the four countries were selected, also taking into account their acronyms —Europa, Europe, EU, UE, euro—. After this first filtering using the tiditext R package (Silge and Robinson, 2017), those tweets that, despite including any of these patterns, did not refer to Europe —for example, if the word “euros” was used to refer to a monetary amount— were manually discarded by the research team. The final result of this process, as shown in Table 1, produced a corpus of 9.883 tweets out of the total 49.101 tweets initially retrieved.

Table 1.

Number of tweets with explicit references to Europe from total retrieved tweets (per party, per country and globally)

| Country | Party name | Twitter account | Retrieved tweets | Selected tweets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | 24.659 | 2.821 | ||

| Atarrabia Taldea | N/A | |||

| Barcelona en Comú | @bcnencomu | 1.532 | 36 | |

| Bloque Nacionalista Galego | @obloque | 758 | 135 | |

| Catalunya en Comú | @CatEnComu | 482 | 33 | |

| Ciudadanos — Partido de la Ciudadanía | @CiudadanosCs | 1.956 | 230 | |

| Coalición Canaria | @coalicion | 2.140 | 60 | |

| Compromiso por Galicia | @Compromiso_gal | 87 | 30 | |

| Demòcrates Valencians | @DemocratesVAL | 517 | 104 | |

| Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya | @Esquerra_ERC | 2.160 | 231 | |

| Euskal Herria Bildu | @ehbildu | 1.758 | 101 | |

| Euzko Alderdi Jeltzalea — Partido Nacionalista Vasco | @eajpnv | 1.762 | 164 | |

| Izquierda Unida | @iunida | 1.553 | 261 | |

| Junts per Catalunya | @JuntsXCat | 1.971 | 357 | |

| Partido de los Socialistas de Cataluña | @socialistes_cat | 1.086 | 139 | |

| Partido Popular | @populares | 1.170 | 119 | |

| Partido Socialista Obrero Español | @PSOE | 1.610 | 169 | |

| Partit Demòcrata Europeu Català | @Pdemocratacat | 1.476 | 248 | |

| Proposta per les Illes Balears | @ElPi_IB | 405 | 12 | |

| Unidas Podemos | @ahorapodemos | 1.190 | 254 | |

| VOX | @vox_es | 1.046 | 138 | |

| France | 9.553 | 3442 | ||

| Agir | @agir_officiel | 187 | 93 | |

| Europe écologie-Les verts | @EELV | 1.077 | 327 | |

| France insoumise | @FranceInsoumise | 1.980 | 365 | |

| La Republique En marche! | @enmarchefr | 473 | 263 | |

| Les Républicains — Union de la droite et du centre | @lesRepublicains | 1.246 | 475 | |

| Mouvement Democrate | @MoDem | 787 | 373 | |

| Mouvement radical, social et libéral | @MvtRadical | 112 | 44 | |

| Nouvelle Donne | @Nouvelle_Donne | 755 | 437 | |

| Parti Socialiste | @partisocialiste | 1.041 | 370 | |

| Place publique | @placepublique_ | 294 | 191 | |

| Radicaux de Gauche | @Radicaux2Gauche | 101 | 46 | |

| Rassemblement national | @RNational_off | 1.500 | 458 | |

| Italy | 5.989 | 1.173 | ||

| Forza Italia | @forza_italia | 1.771 | 425 | |

| Fratelli d'Italia | @FratellidItaIia | 1.740 | 368 | |

| Lega Salvini Premier | @LegaSalvini | 988 | 92 | |

| Movimento Cinque Stelle | @Mov5Stelle | 578 | 64 | |

| Partito Democratico | @pdnetwork | 908 | 221 | |

| Südtiroler Volkspartei (Partito popolare sudtirolese) | @SVP_Suedtirol | 4 | 3 | |

| Germany | 8900 | 2447 | ||

| Alternative für Deutschland | @AfD | 323 | 47 | |

| Bündnis 90/Die Grünen | @Die_Gruenen | 171 | 81 | |

| CDU/CSU (coalition) | CDU_CSU_EP | 1 | 0 | |

| Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands | @CDU | 1.174 | 592 | |

| Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern e.V. | @CSU | 471 | 221 | |

| Die linke | @dieLinke | 557 | 145 | |

| Familien-Partei Deutschlands | N/A | |||

| Freie Demokratische Partei | @fdp | 633 | 128 | |

| Freie wähler | @FREIEWAEHLER_BV | 28 | 14 | |

| Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei | @oedppresse | 167 | 58 | |

| Partei für Arbeit, Rechtsstaat, Tierschutz, Elitenförderung und basisdemokratische Initiative | @DiePARTEI | 266 | 33 | |

| Partei mensch umwelt tierschutz | @Tierschutzparte | 209 | 24 | |

| Piratenpartei Deutschland | @Piratenpartei | 1.159 | 214 | |

| Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands | @spdde | 2.972 | 636 | |

| VOLT | @DeutschlandVolt | 769 | 254 | |

| Total | 49.101 | 9.883 |

Source: Own elaboration based on the tweets retrieved.

The list of words that would make up the final corpus of the study was then drawn up. The list was compiled by taking into account, on the one hand, the nouns and adjectives that appear in the list of EU government priorities published on the European Commission’s website. On the other hand, the 20 words that appeared most frequently in the selected tweets from each of the countries —after discarding stop words— were included —if they were not already on the list. The list was closed with 121 keywords (available in Appendix 1), which appeared in 4,758 of the 9,983 tweets with messages related to the European Union.

The analysis of the frequency of each of the terms makes it possible to determine which issues are given visibility (salience), while the diversity of voices (parties) talking about an issue can be viewed as the second step in the process of politicization.

5. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION[Up]

5.1. Salience of European political issues [Up]

This subsection answers RQ1a (Following Brexit, are there signs of the politicization of other more specific issues beyond the integration debate in the 2019 elections?) and RQ1b (What issues have become politicized during the campaign in the countries studied?) by showing the results of the word frequency analysis in the different countries, both separately and together.

The results obtained allow us to answer RQ1a in the affirmative: the analysis of the tweets demonstrates that other issues that form part of the political priorities of the EU were addressed in the 2019 European Parliament election campaign.

The visibility of issues connected with EU political activity is higher in Germany, France and Spain, with Italy demonstrating somewhat different dynamics that will be discussed at the end of this section.

Table 2 shows the frequency of words found in the tweets. The analysis of the words most frequently repeated indicates that political parties voiced matters of European politics that ranged beyond the debate on integration, encompassing issues such as freedoms, rights, social policy, security, and employment. Notably, climate (linked to climate policies and climate change) stands out as one of the main topics of the electoral campaign on Twitter.

The majority of the messages fall into two broad categories: those that refer to EU principles of identity (freedom, rights, solidarity, economy, peace, etc.), and those that deal with more specific issues (climate, Spitzenkandidat, borders, etc.) or make proposals (in terms of tax policy, investments, etc.).

The repetition of terms in numerous tweets would be indicator of their salience. If we take the definition used by Hutter and Grande (2014) as a starting point, establishing the need for an issue to be spoken about publicly as a first principle in the politicization of that issue, salience could be interpreted as a first step on the process of politicization.

Table 2.

Most repeated words (in each country and globally)

| Spain | Freq. | Germany | Freq. | France | Freq. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Politics | 132 | Social | 120 | Social | 133 |

| Rights | 132 | Spitzenkandidat | 108 | Climate | 111 |

| Freedom | 102 | People | 86 | Leftist | 65 |

| Social | 93 | Peace | 82 | Rights | 49 |

| Solidarity | 93 | Climate | 81 | Frontier | 41 |

| Democratic | 65 | Strong | 74 | Bank | 38 |

| Future | 59 | Future | 64 | Future | 38 |

| Democracy | 55 | Freedom | 52 | Citizens | 37 |

| Fair | 53 | Security | 48 | Protection | 32 |

| Economy | 34 | Populist | 47 | Market | 31 |

| Italy | Freq. | Globally | Freq. | ||

| Change | 154 | Social | 355 | ||

| Employment | 33 | Climate | 217 | ||

| Economy | 28 | Rights | 206 | ||

| Future | 26 | Future | 187 | ||

| Growth | 22 | Change | 187 | ||

| Citizens | 21 | Freedom | 168 | ||

| Austerity | 16 | Solidarity | 135 | ||

| Investment | 14 | Politics | 132 | ||

| Youth | 11 | Citizens | 127 | ||

| Leftist | 10 | Strong | 125 | ||

Source: Own elaboration based on the tweets retrieved.

The word that is most often repeated in absolute terms in political party messages is “social” (see Table 2). This is the case for the total of the four countries, but also for Germany and France, where the word occupies the first position, with 120 and 133 repetitions, respectively. In Spain it occupies fourth place, with 93 repetitions.

The term social is used in numerous tweets to talk about the model of Europe proposed by political parties. The article focuses on making a frequency analysis to assess the degree of salience and diversity of voices, but does not make a qualitative analysis of the tweets. Nevertheless, Figure 1 shows some examples containing the term social which illustrate how parties use the term in tweets.

The results also point to the emergence of climate change as one of the issues with the greatest presence in the campaign (examples in Figure 2), occupying second position in the global results. In France, the word climate ranks second (being used in 111 tweets) and in Germany, fifth (almost tied with third, with 81 mentions). In Spain (22) and in Italy (3) mentions of this matter are much less frequent.

Although it was not the objective of the present research to delve into this area, signs of polarization of the debate around certain issues (detected in an explorative analysis of the tweets, figure 3) are also an indicator of politicization. This would be an interesting focus for future research.

Other issues that go beyond the debate on integration, related to citizens’ rights or migration policy and security, have also had visibility in the EU election campaign. The term rights (with 206 mentions, often used to accompany a proposal for the parties preferred model of Europe) takes third place on the list (Table 2).

The term freedom is the sixth most frequent word on the global list (168), as one of the values with which the parties identify the European project.

Migration (31), immigration (38), migrants (29) and asylum (18) also appear on the list of terms cited by parties, which are signs of salience of the migration policy and the refugee crisis. Although it was not the objective of the present research to delve into this area, signs of polarization of the debate around certain issues (detected in an explorative analysis of the tweets, figure 3) are also an indicator of politicization. This would be an interesting focus for future research.

Regarding economic issues, tweets were found that refer to proposals with a higher level of specificity, for example related to EU tax policy there are 78 mentions of the term “taxes”.

As noted at the beginning of this section, the visibility of issues connected with EU political activity is higher in Germany, France and Spain, with Italy demonstrating different dynamics.

In the case of Italy, the most frequent word is change, which at 154 mentions (Table 2 and Figure 5), is significantly more common than the next most frequently mentioned word. The frequency with which Italy uses the word change makes it the fifth most repeated, giving it a total across the four countries of 187 mentions. An explanation for these results might be the vital debate about the European model, fomented by the weight of Eurosceptic parties in Italy. It is significant, however, that this debate was articulated on Twitter without questioning membership of the EU: allusions were made to changing Europe from within, not abandoning the community project.

Figure 5.

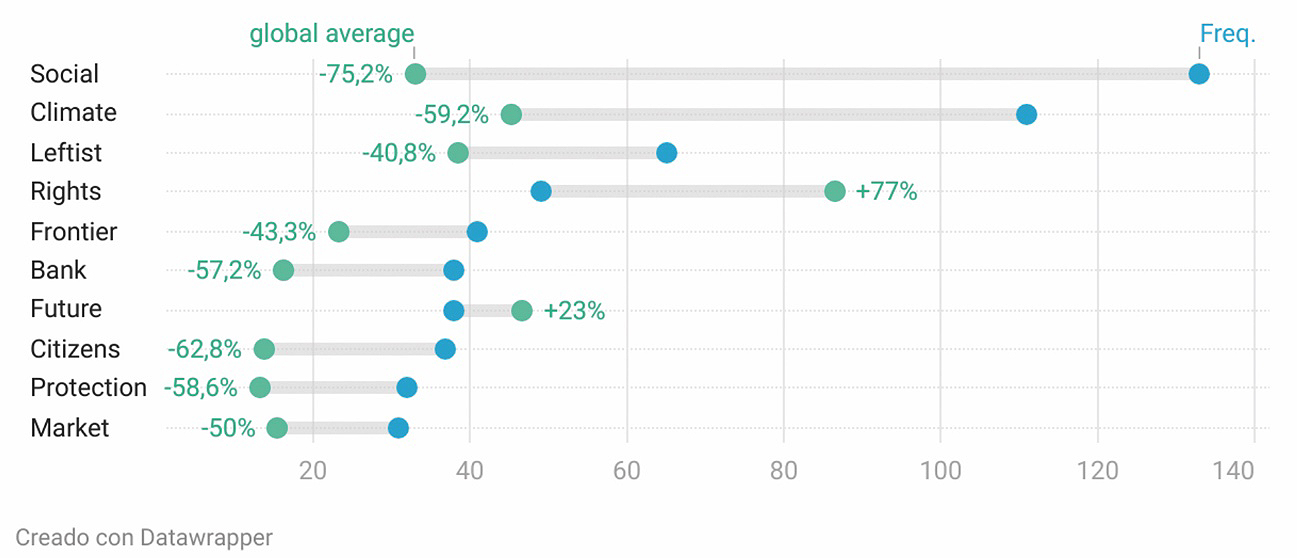

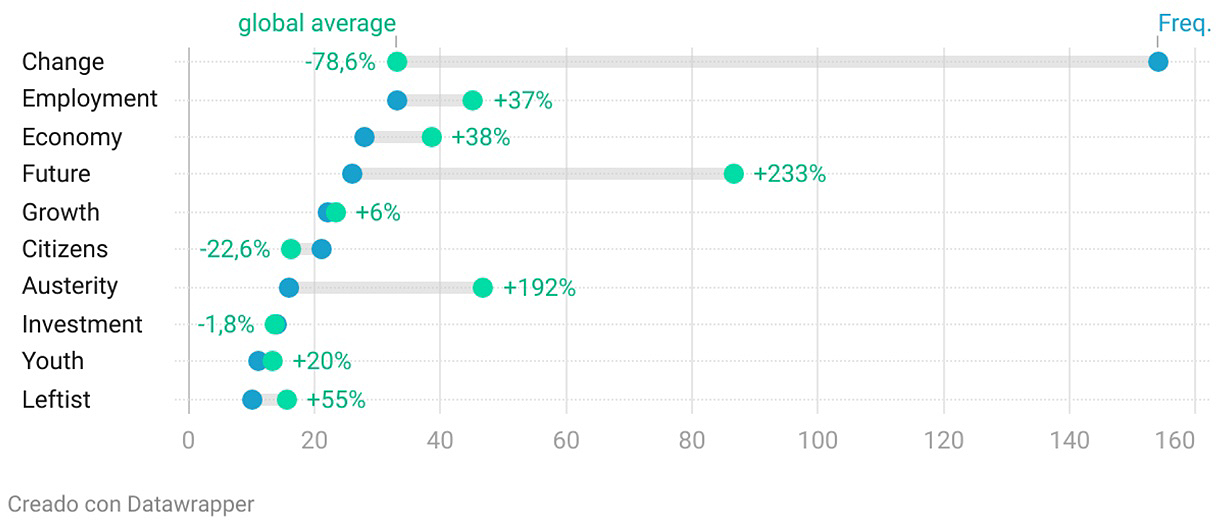

Ten most frequent words in Italy versus average frequency among the countries analyzed

Source: authors.

In Italy, the frequency with which terms, other than change, are repeated is notably lower than that detected in the other three countries (see detail in Figure 5). That is, they had less visibility and therefore there would be less evidence of their politicization (if we accept the definition of politicization in which one of the main requirements for a term to be considered politicized is its presence in the public debate). The prominence of the word change and that the next words on the list in terms of frequency are employment, economy, future, growth, citizens, and austerity, could be a consequence of the weight still given in Italy to the public debate about the management of the euro zone economic crisis of 2008.

It does not necessarily follow from these data that a lesser degree of politicization of the EU exists in Italy, but less level of politicization around terms that have had more visibility in other countries. As pointed out by previous studies, Eurosceptic parties and the debate on integration have also contributed to politicizing the European project. Hutter and Grande (2014) detected significant increases in the politicization index of European Integration in the United Kingdom, in the years following the approval of the Maastricht Treaty. Both conflict at the national level and the high levels of polarization influenced the debate about belonging to the EU. According to the authors, at the same time the politicization of the European project in continental countries such as Germany or France was significantly lower.

However, the present research aims to detect signs of politicization of issues beyond the debate on integration by means of the visibility they have been given in the election campaign. And, at this point, the results in Italy indicate that topics beyond integration are awarded less visibility. For example, the issue of climate change has minimal presence compared to the other three countries. Only the terms already mentioned such as employment, economy, future, growth, citizens and austerity have some salience.

As previously mentioned, Adam et al. (2017) stated: “The salience of EU issues in political campaigns is linked to the levels of polarization” in each country. Italy has had 66 different governments since World War II, and perhaps this greater political polarization could explain the smaller voice given to more specific European issues. The absence of conflict enables campaigning on EU issues by all parties and high levels of conflict lead to more nation-centred campaigns (Jansen et al, 2019). The question of the polarization of national politics could also explain the relative lack of politicization of other more specific terms in Spain with respect to France and Germany.

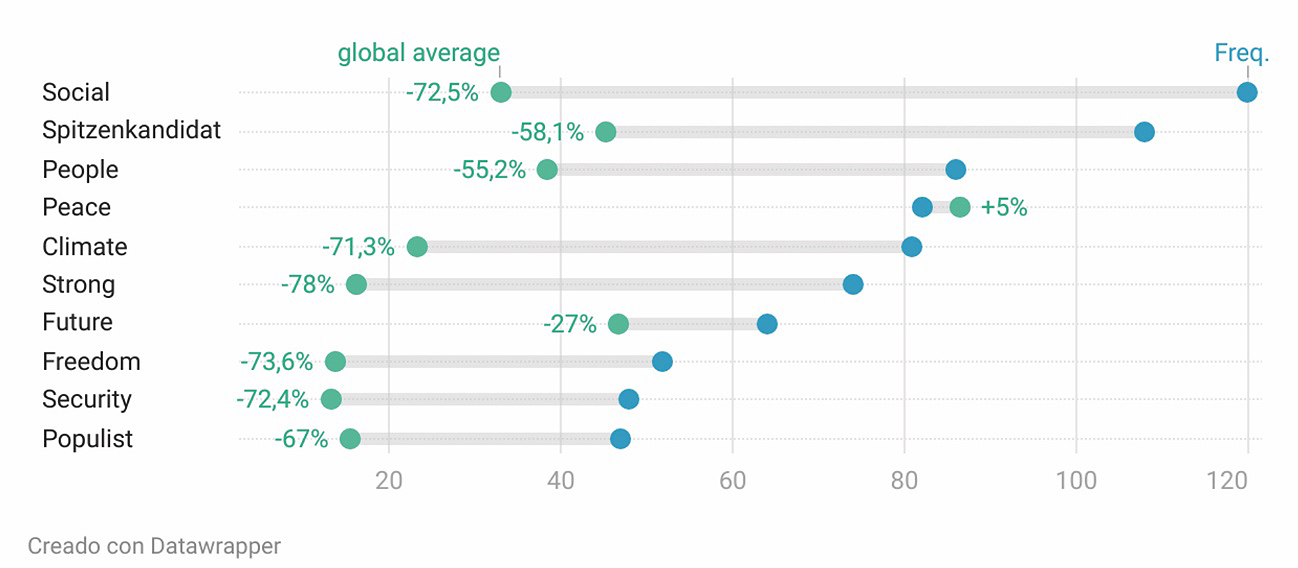

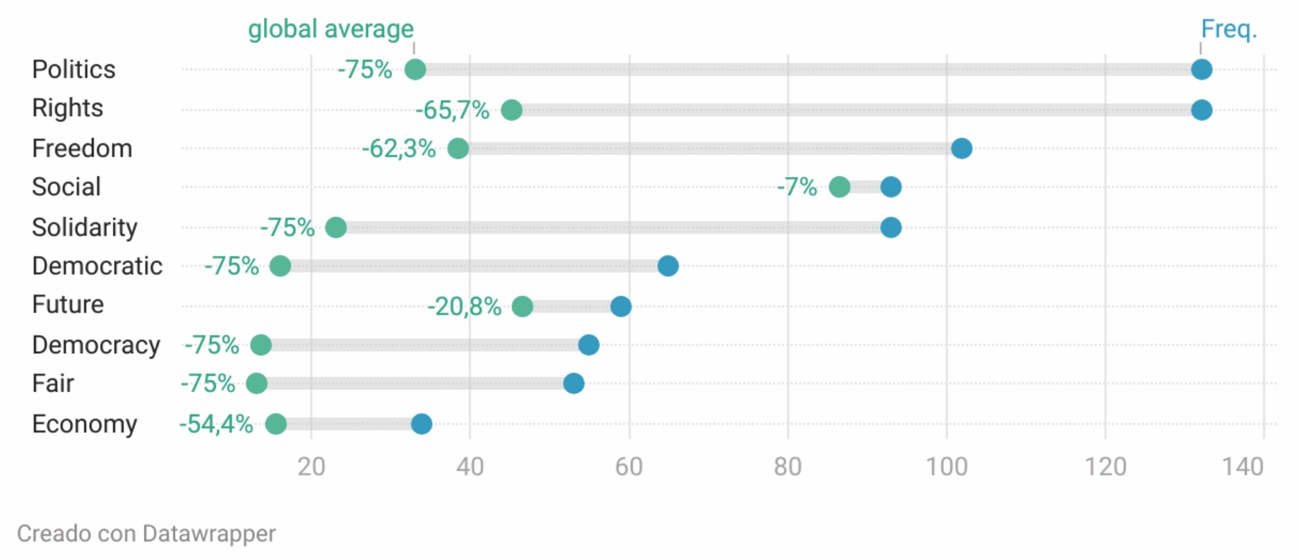

Figures 6, 7 and 8 also show the deviation of the most frequent words in each country with respect to the mean value of the frequency considered for the 4 countries aggregated.

We can see that in France and Germany the tweets that stand out are those that talk about social policy, climate or people/citizens. Spain also has a high frequency of the term social.

Among the values that are out of the average, the visibility given in Germany to the term Spitzenkanditat (which refers to the nomination of a preferred candidate for president of the European Commission by the different political families) stands out. This is logical, considering that it is a term coined there, but it is an indication of the effective politicization of this issue.

In Spain, the value of the terms rights, freedoms and solidarity stands out (see Figure 8). Also of the terms justice, democracy and democratic. A possible hypothesis that would justify the frequency of these last terms is the complex political moment at the internal level with the Catalan question, after the declaration of independence that ended with the trial and subsequent conviction of the political leaders involved.

5.2. Diversity of voices [Up]

This subsection provides an answer to RQ2 (How many different parties have talked about the most frequently debated issues during the election campaign?) by paying attention to the number of different parties that have spoken about the terms analysed in the previous section.

Adam et al (2017) establish a second requirement for politicization to exist; that it is necessary for parties to enter a common debate about the same aspects of EU integration. Along similar lines, Hutter and Grande spoke of expanding the debate on a topic to different actors. A diversity of voices speaking on the same subject. To answer RQ2, an analysis of the total number of different parties across all four counties and by individual country, voicing the same issue was carried out. Table 3 shows the number of different parties (aggregate results for the four countries analyzed) that speak at least once on each of the topics and expresses the percentage that these parties represent out of the total number of parties contesting the elections (51).

More than 2 out of 3 parties (more than 66 %) talk about rights, social policy, the future, and the economy. At least half of the parties talk about climate, employment, solidarity, and freedom. And more than 1 in 3 (value 33 % or more, a minimum of 17 out of 51 in Table 3) contribute to the politicization of very specific terms such as borders, investments, taxes, wages and the environment. Also at least 1 in 3 parties was involved in the debate on one or more of the 31 most frequent terms.

Table 3.

Number and percentage of political parties that talk about each topic

| Term | Number of political parties | % of political parties (n=51) |

|---|---|---|

| Rights | 37 | 72,5 |

| Social | 36 | 70,6 |

| Future | 36 | 70,6 |

| Economy | 35 | 68,6 |

| Democracy | 33 | 64,7 |

| Climate | 30 | 58,8 |

| Citizens | 30 | 58,8 |

| Democratic | 30 | 58,8 |

| Employment | 30 | 58,8 |

| Solidarity | 29 | 56,9 |

| Strong | 29 | 56,9 |

| Freedom | 28 | 54,9 |

| Values | 28 | 54,9 |

| Peace | 24 | 47,1 |

| Change | 23 | 45,1 |

| Tax | 23 | 45,1 |

| Frontier | 22 | 43,1 |

| Fair | 22 | 43,1 |

| Environment | 22 | 43,1 |

| Investment | 20 | 39,2 |

| Salary | 20 | 39,2 |

| Leftist | 19 | 37,3 |

| Security | 19 | 37,3 |

| Diversity | 19 | 37,3 |

| Migration | 19 | 37,3 |

| Challenges | 19 | 37,3 |

| Politics | 18 | 35,3 |

| Open | 18 | 35,3 |

| Populist | 17 | 33,3 |

| Justice | 17 | 33,3 |

| Sustainability | 17 | 33,3 |

| Crisis | 17 | 33,3 |

| Digital | 16 | 31,4 |

| Market | 16 | 31,4 |

| Protection | 16 | 31,4 |

| Territory | 16 | 31,4 |

| Growth | 16 | 31,4 |

| World | 16 | 31,4 |

| Refugees | 16 | 31,4 |

| Bank | 15 | 29,4 |

| Energy | 15 | 29,4 |

| Youth | 14 | 27,5 |

| Progress | 14 | 27,5 |

| Immigration | 13 | 25,5 |

| Populism | 13 | 25,5 |

| Commerce | 13 | 25,5 |

| Brexit | 13 | 25,5 |

| Cultural | 13 | 25,5 |

Source: Own elaboration based on the tweets retrieved.

More than 56% of the parties addressed issues related to the following terms: rights, social, future, economy, democracy, climate, citizens, democratic, employment or solidarity.

These results show that almost all parties speak of Europe in terms of values such as democracy, future and rights, which could also be evidence of leaving behind the debate on integration and politicization of the European project around its founding values.

If detailed attention is paid to some of the most frequently used terms, such as climate, it becomes clear that this is not an issue addressed exclusively by green parties, but that many parties addressed the issue in the weeks leading up to the elections: in Spain 8 out of 19 parties (42.1%) voiced opinions about the climate, in France 9 out of 12 parties (75%) addressed the issue, and in Germany it was addressed by 11 out of 14 parties (78, 6%). This data supports the thesis that the climate is one of the issues that shows the most evidence of politicization in the campaign.

Other terms such as border were also used by up to 10 out of 12 parties in France (83.3%) and 8 out of 14 in Germany (57.1%), which could be interpreted as signs of the politicization of the immigration issue and border policy during the election campaign.

The results show that there are no significant differences between countries for the “Diversity of voices” indicator (see Table 3). Table 4 provides the data broken down by country: it shows the most frequent topics and the number of different parties talking about them in each country. The percentage expresses what that number of parties represents with respect to the number of parties running for election in each country.

The analysis by country also yields other interesting data, up to 30 of the terms selected for analysis were voiced in France by at least 50% of parties. This could be interpreted as evidence that the campaign has revolved around specific issues in which most of the parties have participated, reinforcing the evidence suggesting a growing politicization.

In Italy, terms such as Economy and Employment stand out, which were spoken of by up to 83.3% of the parties. This may be a sign (in line with the results of the previous section) that economic issues marked the Italian campaign, which could be related to the economic crisis of the euro zone in the previous years and the austerity policies applied to the southern countries.

Table 4.

Number and percentage of political parties that talk about a topic by country

| France | % n=12 | Germany | % n=14 | Italy | % n=6 | Spain | % n=19 | Global | % n=51 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austerity | 1 | 8,3 | 0 | 0,0 | 4 | 66,7 | 4 | 21,1 | 9 | 17,6 |

| Bank | 9 | 75,0 | 2 | 14,3 | 0 | 0,0 | 4 | 21,1 | 15 | 29,4 |

| Change | 5 | 41,7 | 4 | 28,6 | 5 | 83,3 | 9 | 47,4 | 22 | 43,1 |

| Citizens | 10 | 83,3 | 9 | 64,3 | 4 | 66,7 | 7 | 36,8 | 30 | 58,8 |

| Climate | 9 | 75,0 | 11 | 78,6 | 2 | 33,3 | 8 | 42,1 | 30 | 58,8 |

| Democracy | 9 | 75,0 | 9 | 64,3 | 4 | 66,7 | 11 | 57,9 | 33 | 64,7 |

| Democratic | 8 | 66,7 | 9 | 64,3 | 2 | 33,3 | 11 | 57,9 | 30 | 58,8 |

| Economy | 8 | 66,7 | 11 | 78,6 | 5 | 83,3 | 11 | 57,9 | 35 | 68,6 |

| Employment | 8 | 66,7 | 7 | 50,0 | 5 | 83,3 | 10 | 52,6 | 30 | 58,8 |

| Fair | 5 | 41,7 | 4 | 28,6 | 0 | 0,0 | 13 | 68,4 | 22 | 43,1 |

| Freedom | 8 | 66,7 | 6 | 42,9 | 1 | 16,7 | 13 | 68,4 | 28 | 54,9 |

| Frontier | 10 | 83,3 | 8 | 57,1 | 1 | 16,7 | 3 | 15,8 | 22 | 43,1 |

| Future | 11 | 91,7 | 8 | 57,1 | 4 | 66,7 | 13 | 68,4 | 36 | 70,6 |

| Growth | 3 | 25,0 | 4 | 28,6 | 4 | 66,7 | 5 | 26,3 | 16 | 31,4 |

| Investment | 6 | 50,0 | 4 | 28,6 | 3 | 50,0 | 7 | 36,8 | 20 | 39,2 |

| Leader | 0 | 0,0 | 11 | 78,6 | 0 | 0,0 | 0 | 0,0 | 11 | 21,6 |

| Leftist | 9 | 75,0 | 0 | 0,0 | 3 | 50,0 | 7 | 36,8 | 19 | 37,3 |

| Market | 9 | 75,0 | 3 | 21,4 | 0 | 0,0 | 4 | 21,1 | 16 | 31,4 |

| Peace | 9 | 75,0 | 7 | 50,0 | 1 | 16,7 | 7 | 36,8 | 24 | 47,1 |

| Populist | 4 | 33,3 | 4 | 28,6 | 2 | 33,3 | 7 | 36,8 | 17 | 33,3 |

| Protection | 8 | 66,7 | 0 | 0,0 | 1 | 16,7 | 7 | 36,8 | 16 | 31,4 |

| Rights | 9 | 75,0 | 8 | 57,1 | 4 | 66,7 | 16 | 84,2 | 37 | 72,5 |

| Security | 4 | 33,3 | 6 | 42,9 | 4 | 66,7 | 5 | 26,3 | 19 | 37,3 |

| Social | 11 | 91,7 | 9 | 64,3 | 1 | 16,7 | 15 | 78,9 | 36 | 70,6 |

| Solidarity | 6 | 50,0 | 5 | 35,7 | 2 | 33,3 | 16 | 84,2 | 29 | 56,9 |

| Strong | 8 | 66,7 | 8 | 57,1 | 0 | 0,0 | 13 | 68,4 | 29 | 56,9 |

| Youth | 0 | 0,0 | 4 | 28,6 | 3 | 50,0 | 7 | 36,8 | 14 | 27,5 |

Source: Own elaboration based on the tweets retrieved.

The term climate appears in tweets from a wide range of parties in Germany and France, as well as other terms like social (social policy) or border (migration policy).

It is interesting to note that the term economy (related to some proposal or reference to economic policy) has a high percentage of diversity of voices in all countries. This could be explored as an indication of greater maturity in the process of politicization of economic issues in the EU.

Terms traditionally linked to the idea of Europe and to the founding values of the EU (such as rights, peace, freedom, solidarity) also show a great diversity of voices in almost all countries when looking at the results country by country, which would therefore reflect the already noted tendency to use these common places when campaigning in European elections and how they contribute to politicize the project around these values.

6. CONCLUSIONS[Up]

By means of analysing media coverage (Grill and Boomgaarden, 2017), news platforms and political blogs (De Wilde et al., 2014), or communication by political actors (Nulty et al., 2016; Fazekas et al., 2020), previous research has investigated the possible emergence, during electoral periods, of a public European sphere. Despite identifying some signs of a transnationalization of the debate on European issues, the overriding importance of the discussion on integration or the transfer of powers of the states issues was noted.

The present study further contributes to this line of research by analysing the topics discussed by political parties in four EU countries, to see what issues are voiced when talking about Europe in the 2019 election campaign, the first election after Brexit. We emphasize that studying the messages of the parties is important since “as long as elite communication strategies limit expansion, we cannot expect EU issues to be the decisive factor in structuring political competition across member states” (Fazekas et al., 2020).

The results show that, during the last electoral campaign, the parties addressed European policy issues beyond the integration debate, giving visibility to specific European policy-related issues. They spoke about freedoms, rights, climate policy, social policy, security, economy and employment, among others. The frequency with which these issues are referred to (beyond the debate on integration, practically absent in the campaign) was translated in this research as visibility or salience given to these issues. This evidence of salience of specific issues that go beyond the debate about integration, such as the climate and climate policy, tax policy, and migration policy, is one of the most relevant findings of this research, and it is a finding that could in turn confirm an incipient or growing politicization of the European project. The article thus contributes new data to a long-standing line of research.

That these issues are given visibility (salience) in the campaign meets the first requirement of politicization but does not provide sufficient evidence to confirm its presence. Salience is not politicization. The results also allow us to reach other relevant conclusions regarding a further dimension of the definition of politicization on which this article rests: the diversity of actors who voice an issue. The analysis of the number of parties that talk about these issues (diversity of actors/voices) also reinforces evidence of politicization. More than 1 in 3 parties (more than 33 % from total of 51 parties) voiced one or more of the 31 most frequent issues. Terms such as climate were addressed not only by green parties, but by up to 79% of parties in France and 75% in Germany. Many of the terms with high salience are also treated by a wide diversity of voices. More than 56% of the parties addressed issues related to the following terms: rights, social, future, economy, democracy, climate, citizens, democratic, employment or solidarity. This reinforces the evidence of politicization of the project around these terms.

Although the present study is not a comparative study, the results evidence the existence of differences between the four countries. The increasing politicization of European political affairs, that is the subject of this research, seems to be higher in Germany, France, and Spain than it is in Italy. In these three countries there is greater visibility, more tweets about and more signs of the politicization of a greater number of different issues (climate, taxes, borders, etc.). In Italy, on the other hand, the presence of topics related to the economy and employment stands out. As previously noted, in Italy the word most frequently repeated is change. A possible explanation could be the presence of up to two Eurosceptic parties in the country (out of a total of six contesting the European elections).

Albeit less so in the case of Italy, there are signs that could point to an increasing politicization of the European Union in all four of the countries analysed. The visibility of common terms and the number of political actors producing and disseminating messages with a common agenda allow us to confirm the existence of the trend.

Another interesting finding arising from the analysis of the tweets was the detection of conflicting positions on economic issues, immigration policy, and even climate change. Considering that many political scientists understand political polarization as the separation of partisans or elites on issues or policy spectrums (Dalton 2008; Hetherington 2001), these divergent positions can be understood as indications of polarization, making them the third dimension of politicization. However, specific research focused on analysing the polarization of the debate on the issues that have surfaced in the campaign would be necessary for this to be established.

7. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH[Up]

The present study is additionally limited by its inclusion of just 4 of the 27 member states. Although they are the 4 countries with the most demographic weight in the EU, any generalizations drawn must done so with caution.

The main objective of this research was to detect frequencies that would allow us to speak of salience and diversity of voices as evidence of politicization, and this has been achieved. After the study, the authors suggest the need for future research in upcoming elections to have a temporal perspective and research that includes qualitative analysis of tweets and explores differences, for example, between different political families.

Also, a systematic study with a comparative approach would be needed to further investigate differences detected between countries.

One limitation of the method employed in the present research is that it leaves out institutions and organisations of civil society whose voices would be interesting to consider in addition to that of political parties. This limitation could be addressed in future research focused on the messages published by other social agents.

Finally, research carried out at other times of the political cycle (and not during the electoral campaign) that might contribute to the study of the degree of politicization of the European project would also prove interesting.

References[Up]

|

Adam, Silke, Eva-Maria Antl-Wittenberg, Beatrice Eugster, Melanie Leidecker-Sandmann, Michaela Maier y Franzisca Schmidt. 2017. Strategies of pro-European parties in the face of a Eurosceptic challenge. European Union Politics, 18(2), 260-282. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1465116516661248 |

|

|

Alonso-Muñoz, Laura y Andreu Casero-Ripollés. 2018. Political agenda on Twitter during the 2016 Spanish elections: issues, strategies, and users’ responses. Communication & Society 31(3), 7-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.15581/003.31.3.7-23 |

|

|

Aragón, Pablo, Karolin E. Kappler, Andreas Kaltenbrunner, David Laniado y Yana Volkovich. 2013. Communication dynamics in twitter during political campaigns: The case of the 2011 Spanish national election. Policy & internet, 5(2), 183-206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1944-2866.POI327 |

|

|

Braun, Daniela, Swen Hutter y Alena Kerscher. 2016. What type of Europe? The salience of polity and policy issues in European Parliament elections. European Union Politics, 17(4), 570-592. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116516660387 |

|

|

Chadwick, Andrew. 2013. The hybrid media system: Politics and power. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Dalton, Russell J. 2008. The quantity and the quality of party systems: Party system polarization, its measurement, and its consequences. Comparative Political Studies, 41(7), 899-920. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0010414008315860 |

|

|

De Wilde, Pieter. 2011. No polity for old politics? A framework for analyzing the politicization of European integration. Journal of European Integration, 33(5), 559-575. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2010.546849 |

|

|

De Wilde, Pieter, Asimina Michailidou y Hans-Jörg Trenz. 2014. Converging on euroscepticism. European Journal of Political Research, 53(4), 766-783. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12050 |

|

|

Dodd, Melissa D. y Steve J. Collins. 2017. Public relations message strategies and public diplomacy 2.0: An empirical analysis using Central-Eastern European and Western Embassy Twitter accounts. Public Relations Review, 43(2), 417-425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.02.004 |

|

|

Fazekas, Zoltán, Sebastian A. Popa, Hermann Schmitt, Pablo Barberá y Yannis Theocharis. 2020. Elite-public interaction on twitter: EU issue expansion in the campaign, European Journal of Political Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12402 |

|

|

Gálvez-Rodríguez, María del Mar, Alejandro Sáez-Martin, Manuela García-Tabuyo y Carmen Caba-Pérez. 2018. Exploring dialogic strategies in social media for fostering citizens’ interactions with Latin American local governments. Public relations review, 44(2), 265-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.03.003 |

|

|

Gander, Pierre. 1999. Two myths about immersion in new storytelling media. Lund University Cognitive Studies, 80. http://www.pierregander.com/research/two_myths_about_immersion.pdf |

|

|

García-Orosa, Berta y Xosé López-García. 2019. Language in social networks as a communication strategy: public administration, political parties and civil society. Communication & Society, 32(1), 107-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.15581/ 003.32.1.107-125 |

|

|

Green-Pedersen, Christoffer. 2012. A giant fast asleep? Party incentives and the politicisation of European integration. Political Studies, 60(1), 115-130. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00895.x |

|

|

Grill, Christiane y Hajo Boomgaarden. 2017. A network perspective on mediated Europeanized public spheres: Assessing the degree of Europeanized media coverage in light of the 2014 European Parliament election. European Journal of Communication, 32(6), 568-582. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0267323117725971 |

|

|

Hamilton, James F. 2016. “Hybrid news practices”. In: Witschge, T.; Anderson, C.; Domingo, D. & Hermida, A. (eds.). The SAGE handbook of digital journalism. London: SAGE, 164-178. |

|

|

Hetherington, Marc J. 2001. Resurgent mass partisanship: The role of elite polarization. American Political Science Review, 95(3), 619-631. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055401003045 |

|

|

Hix, Simon y Michael Marsh. 2007. Punishment or protest? Understanding European parliament elections. The journal of politics, 69(2), 495-510. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00546.x |

|

|

Hix, Simon, Abdul Noury y Gérard Roland. 2006. Dimensions of politics in the European Parliament. American Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 494-520. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00198.x |

|

|

Hurrelmann, Achim, Anna Gora y Andrea Wagner. 2015. The politicization of European integration: More than an elite affair? Political Studies, 63(1), 43-59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12090 |

|

|

Hutter, Swen y Edgar Grande. 2014. Politicizing Europe in the National Electoral Arena: A Comparative Analysis of Five West European Countries, 1970-2010. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 52(5), 1002-1018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12133 |

|

|

Jansen, A. Severin, Beatrice Eugster, Michaela Maier y Silke Adam. 2019. Who Drives the Agenda: Media or Parties? A Seven-Country Comparison in the Run-Up to the 2014 European Parliament Elections. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 24(1), 7-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1940161218805143 |

|

|

Jenkins, Henry. 2003. Transmedia Storytelling: Moving Characters from Books to Films to Video Games Can Make Them Stronger and More Compelling. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2003/01/15/234540/transmedia-storytelling/ |

|

|

Jungherr, Andreas. 2016. Twitter use in election campaigns: A systematic literature review. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 13(1), 72-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2015.1132401 |

|

|

Justel-Vázquez, Santiago, Ariadna Fernández-Planells, MaríaVictoria-Mas e Iván Lacasa-Mas. 2018. Twitter e información política en la prensa digital: la red social como fuente de declaraciones en la era Trump. El profesional de la información, 27(5), 984-992. http://dx.doi.org/10.3145/epi.2018.sep.03 |

|

|

López-Meri, Amparo, Silvia Marcos-García y Andreu Casero-Ripollés. 2017. What do politicians do on Twitter? Functions and communication strategies in the Spanish electoral campaign of 2016. El profesional de la información, 26(5), 795-804. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.02 |

|

|

Nulty, Paul, Yannis Theocharis, Sebastian A. Popa, Olivier Parnet y Kenneth Benoit. 2016. Social media and political communication in the 2014 elections to the European Parliament. Electoral studies, 44, 429-444. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.04.014 |

|

|

Obholzer, Lukas y William T. Daniel. 2016. An online electoral connection? How electoral systems condition representatives’ social media use. European Union Politics, 17(3), 387-407. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116516630149 |

|

|

Rauh, Christian. 2015. Communicating supranational governance? The salience of EU affairs in the German Bundestag, 1991-2013. European Union Politics, 16(1), 116-138. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1465116514551806 |

|

|

Schlesinger, Philip. 1999. Changing Spaces of Political Communication: The Case of the European Union. Political Communication, 16(3), 263-279. https://doi.org/10.1080/105846099198622 |

|

|

Serrano-Contreras, Ignacio-Jesús, Javier García-Marín y Óscar Luego. 2020. Measuring online political dialogue: Does polarization trigger more deliberation? Media and Communication, 8(4), 63-72. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v8i4.3149 |

|

|

Shin, Donghee y Frank Biocca. 2017. Exploring immersive experience in journalism. New Media & Society, 20(8), 2800-2823. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461 444817733133 |

|

|

Schmitt, Hermann e Ilke Toygür. 2016. European Parliament elections of May 2014: driven by national politics or EU policy making? Politics and Governance, 4(1), 167-181. http://dx.doi.org/10.17645/pag.v4i1.464 |

|

|

Shamir, Jacob, Michal Shamir y Liron Lavi. 2015. Voter election frames: What were the elections about? Political Studies, 63(5), 995-1013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12145 |

|

|

Silge, Julia y David Robinson. 2017. Text mining with R: a tidy approach. Sebastopol (CA): O’Reilly. |

|

|

Van der Brug, Wouter, Katjana Gattermann y Claes H. De Vreese. 2016. Introduction: how different were the European elections of 2014? Politics and Governance, 4(1), 1-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.17645/pag.v4i1.591 |

|

|

Van Der Eijk, Cees y Mark N. Franklin. 2004. Potential for contestation on European matters at national elections in Europe. In: G. Marks & M. Steenbergen (Eds.), European Integration and Political Conflict (Themes in European Governance, pp. 32-50). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511492013.004 |

|

|

Van Spanje, Joost y Claes De Vreese. 2014. Europhile Media and Eurosceptic Voting: Effects of News Media Coverage on Eurosceptic Voting in the 2009 European Parliamentary Elections. Political Communication, 31(2), 325-354. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2013.828137 |

|

|

Wells, Chris, Jack Van-Thomme, Peter Maurer, Alex Hanna, Jon Pevehouse, Dhavan Shah y Erik Bucy. 2016. Coproduction or cooptation? Real-time spin and social media response during the 2012 French and US presidential debates. French politics, 14(2), 206-233. https://doi.org/10.1057/fp.2016.4 |

APPENDIX 1: LIST OF WORDS ANALYSED[Up]

| Agenda 2030 | Fair | Populist |

| Agriculture | Foreign affairs | Poverty |

| Apple | Foreign policy | Power |

| Artificial Intelligence | Freedom | Prices |

| Asylum | Freedom of speech | Progress |

| Austerity | Frontier | Progressive |

| Bank | Future | Prosperity |

| Banking union | Protection | |

| Barrier | Green | Protectionism |

| BCE | Gowth | Refugees |

| Biodiversity | Humanitarian | Religion |

| Brexit | Humanitarian aid | Renewable |

| Challenges | Immigration | Research |

| Change | Information | Rich |

| Citizens | Infrastructure | Rights |

| Climate | Innovation | Rules |

| Commerce | Integration | Safe |

| Competition | International | Salary |

| Crisis | International weight | Schengen |

| Cultural | Internet | Science |

| Data | Interrail | Security |

| Debt | Investment | Single Market |

| Democracy | Justice | Social |

| Democratic | Language | Solidarity |

| Development | Leftist | Spitzenkandidat |

| Digital | LGTBI | Stability |

| Digital single market | Linguistics | Strength |

| Dignity | Market | Strong |

| Diplomacy | Mediterranean | Sustainability |

| Discrimination | Migrants | Sustainable development |

| Diversity | Migration | Tax |

| Economy | Monetary sovereign | Technology |

| Efficiency | Money | Territory |

| Employment | Network infrastructure | Trade policy |

| Energy | Open | Transparency |

| Environment | Opening | Unemployment |

| Equity | Peace | Values |

| Euro | People | Wall |

| Exclusion | Politics | Welfare state |

| Expansion | Populism | World |

| Youth |