What has become of Podemos? The elites of a radical left party and their evolving dynamics of recruitment

¿Qué ha sido de Podemos? Las élites de un partido de izquierda radical y la evolución de sus dinámicas de reclutamiento

ABSTRACT

In recent years, a growing body of literature has analyzed radical left parties in Europe. However, internal party life and the sociology of party elites have remained an understudied topic, mostly dominated by non-systematic accounts on party leaders. This article offers an empirical exploration of the sociology of Podemos party cadres, based on a prosopography of the elected members of the Consejo Ciudadano Estatal and the Consejo de Coordinación, its main internal institutions, since 2014. This research questions Podemos’ status of “outsider” in the partisan landscape by quantifying three fundamental dimensions of its cadres’ public image: their links with social movements, academia and Latin America. By measuring the social and biographical characteristics of Podemos’ elites as they institutionalize, this article offers a new scientific lens to analyze the trajectory of radical left parties, and provides a method to test common hypotheses on contemporary political forces after the Great Recession.

Keywords: Podemos, Radical Left Parties, Party Cadres, Party Institutionalization, Spanish Politics, Latin America.

RESUMEN

En los últimos años, un creciente número de publicaciones ha analizado los partidos de izquierda radical en Europa. Sin embargo, la vida interna de los partidos y la sociología de sus élites han seguido siendo un tema poco estudiado, dominado en su mayor parte por relatos no sistemáticos sobre los líderes más mediáticos. Este artículo propone una exploración empírica de la sociología de los cuadros del partido Podemos, basada en una prosopografía de los miembros electos del Consejo Ciudadano Estatal y del Consejo de Coordinación, sus principales instituciones internas, desde 2014. Esta investigación cuestiona la condición de «outsider» de Podemos en el panorama partidista cuantificando tres dimensiones fundamentales de la imagen pública de sus cuadros: sus vínculos con los movimientos sociales, la academia y América Latina. Al medir las características sociales y biográficas de las élites de Podemos a medida que se van institucionalizando, este artículo ofrece un nuevo enfoque científico para analizar la trayectoria de los partidos de izquierda radical, y proporciona un método para poner a prueba hipótesis comunes sobre las fuerzas políticas contemporáneas tras la Gran Recesión.

Palabras clave: Podemos, Partidos de Izquierda Radical, Cuadros partidarios, Institucionalización partidaria, Política Española, América Latina.

INTRODUCTION[Up]

In recent years, several radical left parties (RLPs) have emerged on the West and South European political scenes. The post-2008 Great Recession fuelled an important wave of protest among European democracies, which was followed by the electoral successes of pre-existing parties such as Syriza in Greece and the Bloco de Esquerda in Portugal, and provided an impulse for the creation of new political organisations such as Podemos in Spain (2014) or La France Insoumise (2016). Many of these parties quickly accessed a high number of seats in national and local representation, conquered governmental power (e.g. Greece in 2015) or managed to become important partners of government coalitions (e.g. Portugal in 2015 and Spain in 2019), an unprecedented phenomenon in the history of the post-communist radical left, defined as left by its commitments to equality and internationalism and radical by its orientation toward a ‘“root-and-branch” change of the political system” (March 2011).

This political evolution has been analysed by a growing body of literature, covering aspects as diverse as ideology and the growing appeal of the populist rhetoric within the left (Gomez, Morales, and Ramiro 2016; Katsambekis and Kioupkiolis 2019; Ramiro and Gomez 2017; Visser et al. 2014), political platforms and communication (Casero-Ripollés, Sintes-Olivella, and Franch 2017; Krause 2020), membership (Gomez and Ramiro 2019; Tsakatika and Lisi 2013) and electoral dynamics (March and Rommerskirchen 2015) of RLPs. To the date however, party organization and internal party life remain some of the main shortcomings in RLP research (March and Keith 2016; Lourenço 2021; March 2017) and, in particular, almost no systematic study has been undertaken on the sociology of these parties’ elites. This may be linked to a series of recent but dominant political and scientific framings of new RLPs: these new political forces have tended to be analysed as “movement parties” (Della Porta et al. 2017) or as plebiscitarian machines of power (Cervera-Marzal 2021). A large part of the literature thus discusses the adequateness of these two labels with national or cross-national studies, either by assessing the participative and/or new dynamics of grassroots activism (Chironi and Fittipaldi 2017; Petithomme 2020) or by focusing on the confiscation of intra-organizational power by a reduced political oligarchy (Gerbaudo 2021; de Nadal 2021a; Vittori 2022).

In order to start filling this gap on the sociology of RLP elites, this article focuses on the case of Podemos and analyses the social and political profiles of its national cadres, the party in central office (Katz and Mair 1993), by using a new scientific lens: a systematic prosopographic study of members of the Consejo Ciudadano Estatal [State Citizen Council] (CCE), the equivalent of a party parliament, and of the Consejo de Coordinación [Coordination Council] (CC)[1], the equivalent of a party executive, since 2014. This focus on Podemos in the European radical left landscape appears relevant for at least two reasons. First, Podemos has been the most studied non-governing European radical left party in recent scientific literature (Lourenço 2021, 765), making the lack of research on its party cadres particularly striking. Second, Podemos’ relative transparency as regards internal power distribution procedures makes a systematic exploration possible — which is not necessarily the case for other major radical left parties, where co-optation and informality make systematic data collection on such matters more difficult.

Well-known theories on middle-ranking elites, such as May’s law of curvilinear disparity (May 1973), have emphasized the interest of working on intermediary strata of party organization, as they are organized around distinct ideological and social characteristics if compared to top elites and to grassroots members. These are important elements to analyze the party at large, and to avoid oversimplified accounts on party “identity”. In that perspective, we ambition to open the “Party in Central Office” box by comparing some attributes of distinct segments of RLP elites. By following up that lead, this study fulfils two main research objectives. First, synchronically, by confronting established accounts on Podemos elites with systematically collected data on top-of-the-top (CC) and intermediary (CCE) Podemos elites, it delves into the sociology of Podemos’ cadres when the party structures were created. Second, diachronically, by reformulating and testing existing hypotheses on the evolutions of Podemos’ cadres sociology with solid data, it analyses the evolution of these elites in the process of party institutionalization and normalization Podemos has undergone since then.

In the next pages, I first discuss the available literature on RLP cadres and formulate a set of expectations on Podemos party cadres’ sociology and trajectories in terms of party institutionalization. I then describe the data and method used in the analysis and give a brief overview of the history of Podemos party congresses since 2014, providing a few milestones to understand the evolution of the CCE and CC. I subsequently describe the main tendencies observed with this new dataset. Finally, in the discussion section, I assess the accuracy of my starting expectations on the institutionalization of Podemos, and discuss possible comparative extensions of this study to other contemporary RLP cases.

THE SOCIOLOGY OF RADICAL LEFT PARTY ELITES AND PARTY INSTITUTIONALIZATION[Up]

In the overwhelming amount of scholarship on RLPs, the intermediate level of party cadres has somehow been neglected. Yet, this dimension often appears as a central aspect of public discourse on new RLPs and is also an essential element of parties’ anti-establishment communication strategies, which regularly claim to renew representative democracy by opening professional politics to “ordinary” citizens (Kioupkiolis and Katsambekis 2018; Nez 2022). This issue, however, is only marginally taken into consideration in empirical political research, and usually tackled with limited and impressionist accounts on party cadres’ sociology, which do not serve as a core research issue but rather as contextual elements nourishing more in depth accounts of ideological and strategic choices. The connection between ideology and sociology of party members is thus one of the blind spots of RLP research. Three dimensions in particular are often highlighted here: the connection of RLPs with social movements — partly displacing traditional party affiliation as a source of internal legitimacy (Chironi 2018); the connection of RLPs with academia and the growing importance attributed to academic expertise — as opposed to the progressive de-intellectualization and professionalization of European social-democratic parties (Bortun 2019; Rioufreyt 2016); the connection of RLPs with Latin-American “pink-tide” leftist governments of the 2000s, especially in Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador (Compagnon 2017; Dominguez 2017). Taken together and applied to the sociology of party elites, these elements of party identity delineate an ideal-typical image of the RLP cadre as an outsider to both traditional politics (through social movement and academic linkages) and European left traditions (through the influence of Latin America). The literature on new RLPs thus provides a set of hypotheses on party elites composition and evolution, whose salience varies in each organization but is nonetheless observable in most RLP studies. However, there is a lack of empirical and quantitative research offering a general overview on RLP cadres, and a theoretical gap remains when it comes to developing systematic tests for these hypotheses.

On a more theoretical ground, these three pre-stated features (links to social movements, academia and Latin America) of RLPs can all be described as party-external sources of legitimation, using Panebianco’s classical framework for the analysis of party organization. They are typical of non-institutionalized parties and subject to important evolutions in the course of party institutionalization:

“In regard to internal ‘opportunity structures’, a strong institution tends to create an internal inequality system which is very autonomous and independent from the societal one (its inequalities being primarily dictated by the division of labor in its bureaucratic structure); a weak institution will have a less autonomous internal inequality system. Greater institutionalization means greater autonomy from the environment; thus the criteria defining a highly institutionalized party’s internal inequalities tend to be primarily endogenous, specific to a given organization. In the case of weak institutions, such criteria are at least in part exogenous, i.e. externally imposed. […] The less institutionalized a party, the more the internal participation tends to be of the ‘civil’ type, i.e. a transfer within the organization of external resources controlled by people well placed in the societal inequality system. In other words the weaker the institution, the more ‘important notables’ and the fewer ‘political professionals’ we find in its internal hierarchy, in the elected positions, etc.” (Panebianco 1988, 61)

Following Panebianco, external sources of legitimation can be opposed to internal sources of legitimation (such as length of activism in the party), and to the professionalization of party leadership around autonomous hierarchies — hence downplaying the impact of environmental linkages on organizational dynamics. Replacing external by internal sources of legitimation, and replacing amateurs by professionals would thus both contribute to party institutionalization, that we can define as a “process by which organizations and procedures acquire value and stability” (Huntington 1968, 12). In the case of contemporary RLPs, links to social movements, academia and Latin America can thus be used as proxy indicators of the alleged low institutionalization of the party, in order to test: 1) the adequateness of simplified visions of new RLP elites with the actual sociology of party cadres taken as a group; 2) the stability or instability of these characteristics over time.

This approach also offers a base for further comparative analyses on the evolution of alleged “movement-parties” and new parties in general. The political science literature has indeed highlighted different paths of institutionalization a party might undergo (Harmel, Svåsand, and Mjelde 2019), dealing with issues as different as charismatic authority patterns, fluctuating electoral results or access to government positions. This article focuses on a relatively understudied dimension in that perspective: external legitimation sources of party elites, whose dimensions may be context-specific (such as the probably sui generis links of Podemos with Latin America) yet can be integrated in a broader and cross-national research agenda, through a more comprehensive conception of party institutionalization. External legitimation sources are indeed at the crossroads of two of the main aspects of party institutionalization that are usually considered separately (Bolleyer 2023; Randall and Svåsand 2002): value infusion (i.e. when party actors give value to the organization as such, not only as an instrument to achieve a set of meta-organizational goals) and autonomy (i.e. the organization’s ability to define its goals free from the influence of external actors). Frequently associated with either internal or external dimensions of party institutionalization, both value infusion and autonomy are however at stake when it comes to closing or opening the boundaries of the elite recruitment market to the environment surrounding the party.

Based on these theoretical premises, we can formulate four interconnected expectations on the sociology of RLP elites applied to the study of Podemos:

#H1: The three main socio-biographical features that characterize public discourse on RLPs when created (links to social movements, pre-eminence of academics and links to Latin America) should be reflected in the individuals recruited to the highest internal party institutions when they are launched.

Hence we expect to find a high number of individuals with these three characteristics among Consejo de Coordinación and Consejo Ciudadano Estatal members selected during Podemos’ first Citizen Assembly in 2014.

#H2: These external sources of legitimation should work as an asset in internal competition, and favour the access of individual party cadres to the highest positions in the party when it is created — hence creating a gap between different levels of party leadership.

We thus expect to find a gap between the CC and the CCE of Podemos in 2014, with higher proportions of party cadres with links to social movements, academia and Latin America in the CC.

#H3: The consolidation of party organization should be reflected in a downward trend of the three indicators, implying a reduction in the outsider profile of most members of the party elite over time.

Hence we expect to observe a decreasing proportion of Podemos cadres with links to social movements, academia and Latin America in both the CC and CCE after 2014.

#H4: The gap between intermediary and top-ranking party elites as regards external legitimacy assets should also diminish over time, reflecting an increasingly autonomous system of internal hierarchies.

Hence after 2014 we expect to observe diminishing differences among CC and the CCE members as regards links to the three pre-stated features.

DATA AND METHODS[Up]

The choice of Podemos as a case-study is dictated by its paradigmatic nature in the landscape of European RLPs in at least two aspects. First, unlike several European RLPs whose newness could be discussed, since a large part of these “new” parties are based on the transformation of pre-existing party structures that were and remained central (such as Synapsismos in Syriza, or the Parti de Gauche in La France Insoumise), or even originated in splits within social-democratic parties (such as Die Linke), Podemos appears as a purer form of new organization, a priori offering greater space for outsiders to partisan politics. Second, in comparison with its European counterparts, the growth in electoral support and access to public office was particularly quick for Podemos, thus facing the organization with immediate challenges in terms of institutionalization of its party structure. For all these reasons, Podemos appears as a perfect case-study to analyse the transformations of elite recruitment during this relatively short period of time during which RLPs obtained historical scores in multiple European elections.

This study thus relies on a prosopographic database that includes all individuals (n=189) who were ever elected to the Consejo Ciudadano Estatal of Podemos, and among which members of the Consejo de Coordinación were then coopted[2]. The elections took place online during the Citizen Assemblies of 2014 (62 elected members + the Secretary General), 2017 (62 elected members + the Secretary General), 2020 (89 elected members + the Secretary General) and 2021 (97 elected members + the Secretary General). Officially, the CCE and the CC are Podemos’ main internal institutions, although their role may actually be considered as rather formal — especially during Pablo Iglesias’ terms as Secretary General between 2014 and 2021. Nevertheless, their composition can be considered a reflection of Podemos’ intended image towards the public sphere: it shows how certain types of profiles are highlighted or devaluated at different points in time. This is true for the party executive, but also for the party parliament: unlike Unidas Podemos’ parliamentary group (the party in public office), the CC and CCE composition are less dependent on external factors; the internal electoral and cooptation process (except in the case of the 2017 Citizen Assembly) are a mere reflection of a leading group pre-established choice. Both the CC and the CCE are thus an interesting starting point for a sociological inquiry into Podemos’ elites’ evolving characteristics. We however hypothesize that the profile of CCE members can be distinguished from that of the main popular and mediatic leaders of the organization, gathered in the CC, therefore introducing more complexity in our understanding of top-elites in general, and of Podemos elites in particular.

Table 1.

Information sources

| Type of repository | Sources |

|---|---|

| State institutions | Spanish Chamber of deputies Spanish Senate Autonomous communities’ parliaments |

| Podemos | Podemos transparency portal National Citizen Assemblies portals Legislative primary portals Local Citizen Assemblies portals |

| Press | National press Local press |

| Personal | Personal blogs Publicly accessible social media (e.g. Twitter) |

The data was collected using different types of publicly available sources: biographies of CCE members published on Podemos’ transparency portal; biographies and declarations of interest uploaded by candidates to the dedicated websites of each national Citizen Assembly as well as to the dedicated websites of Podemos’ successive legislative primaries or local citizen assemblies elections; biographies or CVs uploaded to other publicly accessible websites (e.g. website of the Spanish parliament, personal blogs, etc.); press coverage of CCE members in the national and local newspapers. The resulting database comprises several types of variables (socio-demographic, political trajectory, connections to Latin America, etc.)[3]. In the subsequent analysis, I will use three sets of variables that help analyse: 1) the former political trajectory of CCE members; 2) their connections to Latin America; 3) their professional background and connections to academia. Descriptive statistics for all the variables used in the analysis are shown in Table 2 and Table 3 in the Appendix section.

In order to identify the previous political trajectory of party elites, I use four sorts of variable: 1) the proportion of former activists of any social or political organization other than Podemos; 2) the proportion of former members of the Spanish Communist Party (Partido Comunista de España, PCE) and its Catalan branch (Partido Socialista Unificado de Cataluña, PSUC), the Communist youth (Unión de Juventudes Comunistas de España, UJCE) or the Catalan Communist Party (Partit dels i les Comunistes de Catalunya, PCC) and its youth branch (Juventud Comunista de Cataluña, JCC)[4]; 3) the average number of former organizations individual members included in the database were ever part of. The counting method used for these three variables raises two sorts of challenges. First, social movement activism does not necessarily formalize into organizational membership (in a labour-union or NGO for instance), and is thus quite elusive. This is the main reason why, when discussing political trajectories of CCE members, this article stresses the evolving proportion of former communist activists rather than the hard-to-catch proportion of non-institutional social movement activists (and its attached political culture), which are often presented as zero-sume-game realities — an assumption that should itself be explored by research. Second, it should also be acknowledged that previous experience in political organizations is also difficult to track: our census mainly relies on individual declarations, cross-checked by analysing past social media involvement, activist websites and press archives — which are more abundant in the case of national and local personalities. Some data may thus be missing: however, there is no particular reason to believe this would significantly affect rough estimates and, more importantly, diachronic evolutions observed in the analysis. I also use the standard age and age groups of CCE members in each election year as a fourth variable in this section.

In order to identify the influence of Latin-American “veterans” among party cadres, I use three sorts of variable: 1) “Latin-American connection” identifies individuals with some sort of public connection with Latin America (family, studies, work experience, etc.); 2) “Bolivarian connection” identifies individuals with some sort of public connection with either Venezuela, Bolivia or Ecuador; 3) “CEPS” identifies individuals publicly involved in the Centro de Estudios Políticos y Sociales, a foundation that realized training and consulting missions for left-leaning political forces in Latin-America in the 1990s and 2000s.

In order to identify the influence of academics within party elites and compare it to other groups’ influence, I use three types of variable: 1) the “academics” variable identifies any sort of people involved in university or research, including people whose main occupation is not teaching or research; 2) the education variable, which is expressed as a categorical variable divided as follows: no higher than secondary education, professional diploma, university studies no higher than Bachelor or equivalent, no higher than Master, PhD; 3) the “type of occupation” variable, which is a categorical variable divided as follows: knowledge workers (merging students, teachers, lecturers, professors or researchers); legal professions; remunerated politicians (either elected representatives, parliamentary assistants or party employees); other.

THE SELECTION PROCESS OF PODEMOS CCE AND CC MEMBERS SINCE 2014: A BRIEF OVERVIEW[Up]

Podemos was launched as a political movement in January 2014. After organizing open primaries which gave the lead to Pablo Iglesias, a young political science professor and TV presenter, Podemos carried out a remarkably successful electoral campaign, and collected 7,98% of the vote and 5 seats in the European Parliamentary elections of May 2014.

The first Citizen Assembly of Podemos took place in October 2014 to define the organizational principles of the party. Pablo Iglesias’ platform, Claro que podemos [Of course we can], which gave more power to the Secretary General, collected 80% of the internal vote. Sumando podemos [Adding up we can], the organizational platform supported by Pablo Echenique and the anticapitalist sector of the party, Izquierda Anticapitalista, which gave more power to local circles, was chosen by only 12% of voters. The power of grassroots activists was thus downplayed to build an electoral “war machine” around the charismatic leadership of Pablo Iglesias. This result was followed by the election of the first Consejo Ciudadano Estatal of Podemos, composed of the Secretary General, 62 members elected by the citizen assembly and the regional coordinators of the party. Only one list, led by Iglesias, ran for this election. 12 CCE members were coopted to form the Consejo de Coordinación, together with the Secretary General.

In December 2015, in the general election, Podemos received 20,7% of the vote and obtained 69 seats out of 350, becoming the third largest party in the Spanish parliament. In the following weeks, Podemos refused to join a coalition government with PSOE and the centre-right party Ciudadanos, and no majority came out of this elected parliament. New elections were thus held in June 2016, for which Podemos formed a coalition with Izquierda Unida (IU), a political organization dominated by the Partido Comunista de España [Spanish Communist Party] (PCE), under the label Unidos Podemos [United we can], and received 21,2% of the vote. The results in this second election were considered disappointing, since the PSOE leadership over left-wing voters was not overthrown and the IU-Podemos coalition obtained worse results than both parties when they ran separately in the previous election.

Internally, Podemos started experiencing a growing conflict over ideological positioning and party alliances. Two of the main founding members, Iñigo Errejón and Pablo Iglesias started to confront each other publicly: the former promoted a left populist agenda, based on the original identity of Podemos and a rejection of the IU-Podemos coalition, while the latter defended a left unitarian agenda, with a more traditional left discourse. These two positions confronted in the second citizen assembly of Podemos in October 2017. Iglesias won this internal contest, securing around 60% in the election and 37 seats in the newly elected CCE. The errejonista sector arrived second, with 37% and 23 seats, while the anticapitalistas, who had run on an independent list, obtained 2 seats and 3% of the vote. 15 CCE members were coopted to form the new CC, together with the Secretary General.

The subsequent history of Podemos combines a decline in electoral support, an affirmation of Iglesias’ stranglehold at all the levels of party structure and several waves of “exit” of internal opponents. After 2019, Podemos and PSOE signed a government pact, several members of Podemos became ministers and Iglesias was appointed vice-president of government. In the meantime, both the errejonista and the anticapitalista sectors had left the party, either formally or informally. The third citizen assembly of may 2020 confirmed Iglesias’ leadership over Podemos, and renewed the CCE membership with 90 appointed seats, all of them secured by Iglesias’ list, with a 92% of the vote. 20 CCE members were coopted to form the CC, together with the Secretary General.

In March 2021, Iglesias resigned from the vice-presidency of government to run for the Madrid regional election to take place in May. After acknowledging the disappointing results in this contest, Podemos arriving only fifth (with 7,2 % and 10 seats), he resigned from both his responsibilities as MP and as Secretary General of Podemos. In June 2021, a fourth citizen assembly was organized to elect a new Secretary General and renew the CCE, bringing Ione Belarra to the head of the party. Her list obtained all the 97 CCE seats to be filled, with 88% of the vote. 25 CCE members were coopted to form the new CC, together with the Secretary General (Plaza-Colodro and Ramiro 2023).

PODEMOS, A PARTY OF OUTSIDERS?[Up]

This section describes the evolutions of elite recruitment in Podemos since 2014 based on our prosopographic data. To this purpose, the three main sources of external legitimacy usually associated with radical left parties (links with social movements in previous activist trajectories, influence of Latin America, over-representation of academics) are assessed. For each dimension, we first provide an empirical state of the art related to Podemos before presenting our findings.

Activist trajectories [Up]

Podemos’ connections to social movements have been a strong focus of attention in the literature, often interested in the environmental linkages of RLPs (Lisi 2019). Recent scholarship on RLP-social movement linkages has indeed highlighted the partly successful strategy of Podemos genesis as regards organizational innovation, and pointed at its originality in the European RLP landscape, contradicting a global tendency towards “organizational conservatism” (Keith and March 2016, 364). The organization itself has promoted a discourse presenting it as a heir to the 2011 Indignados movement, a dimension that has been widely explored (and contested) in research (Barberà, Barrio, and Rodríguez-Teruel 2019; Calvo and Álvarez 2015; de Nadal 2021b; Petithomme 2021). Among the top founding personalities in Podemos, Pablo Iglesias and Iñigo Errejón had an extensive experience in social movement activism, through anarchist groups (Errejón 2021) and the Global Justice Movement (Iglesias Turrión 2009), and a conflicting relationship with institutionalized political parties on the left (Chazel and Fernández Vázquez 2020). According to official narratives, the refusal of IU, the dominant radical left coalition in Spain since the 1980s, to promote a new type of political strategy less rooted in traditional left symbols, triggered the creation of Podemos in 2014 (Iglesias 2015). The founding networks of Podemos were thus nurtured by experienced anti-institutional activist networks, distanced from the PCE, with the important input of the Trotskyist organization Izquierda Anticapitalista (Anticapitalist Left, IA) in the structuring of the first electoral campaign (Anticapitalistas En Podemos : Construyendo Poder Popular, 2016; Dain, 2020). Strongly attached to Podemos’ self-promoted image of a ‘movement-party’, the rejection of the ideological and organizational traditions of the PCE was thus an important feature of Podemos’ foundation in 2014. It is nonetheless frequently stated that communists and former communists’ influence started to grow progressively, especially after the framing of Unidas Podemos in 2016. From that moment on, former PCE members are often said to have increased their power positions within Podemos, leading to a progressive change in the organization’s political culture — disconnecting it from social movements and civil society while strengthening ideological conservatism, bureaucratic procedures and favouring internal purges (Scheltiens Ortigosa 2021; Villacañas 2017). However, the magnitude of this internal shift, its impact on party morphology and its actual contrast with the organization’s original profile remain only vaguely addressed in research.

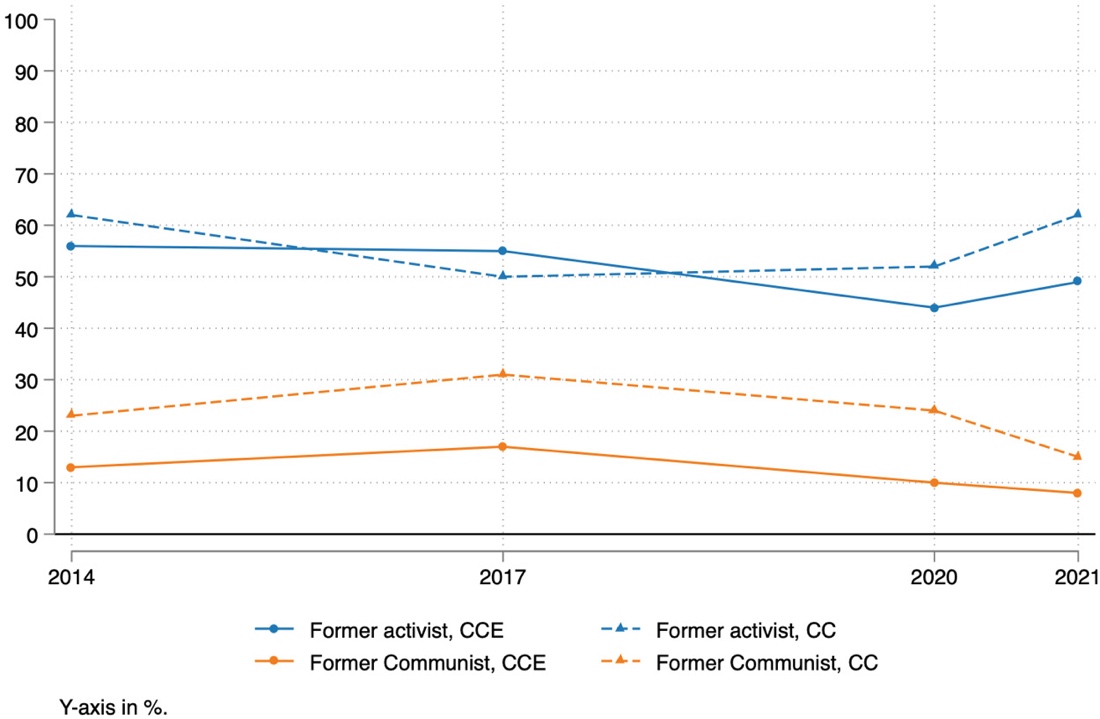

Our prosopographic study shows that, as expected, former members of a communist organization were a minority among Podemos’ elites in 2014: only 13% of Consejo Ciudadano Estatal members and 23% of Consejo de Coordinación members had ever belonged to either the Partido Comunista de España, Partido Socialista Unificado de Cataluña, Unión de Juventudes Comunistas de España or the Juventud Comunista de Cataluña. This figure should be contrasted with their overall activist experience, which was strong: in 2014, 56% of CCE members and 62% of CC members already had an organizational experience in a labour-union, an NGO or a political party (mostly far-left anti-institutional parties or intra-party currents such as Espacio Alternativo or Izquierda Anticapitalista) before they joined Podemos. Even among these experienced activists, less than a quarter (for the CCE) and roughly one third (for the CC) had ever belonged to a communist organization. In 2014, Podemos national cadres were thus no new comers to politics, but their activist experience had mostly taken place outside institutional and/or communist parties.

It is also true, as stated by many commentators, that there was an increasing influence of former communists within Podemos between 2014 and 2017, as shown by Figure 1. After the 2017 internal election, 17% of CCE members and 31% of CC members had personal experience in a communist organization, an increase of respectively 31% and 35%. However this evolution can hardly be considered a structural change in the organizational profile of Podemos. First, because the increase of former communist members was not dramatic: for instance, the 2017 CCE included 10 former communist members (out of 63), while the 2014 CCE included 7. Second, because this evolution was not confirmed in the 2020 and 2021 elections, where former communists only represented 10 and 8% of CCE members respectively, as well as 24% and 15% of CC members, as it is pointed out in Figure 1. This does not necessarily contradict the idea that top-ranking elites of Podemos with previous political experience in communist organizations, such as Irene Montero, Rafael Mayoral or Juan Manuel del Olmo may have had an increasing role in strategic party decisions. However, it somehow tempers accounts of a massive shift in political cultures between 2014 and 2017, since this alleged impulse of former communists in post-2014 Podemos did not translate into major changes as regards CCE and CC recruitment.

It would be more accurate to point that, after the 2017 shift, and looking at standard ages of the individuals in the database, a new generation of activists integrated the party elites (see Tables 2 and 3 in the Appendix). Indeed, between 2014 and 2017 (i.e. within only three years), CCE members had grown 6 years older on average, and 5 years older for CC members — which can be linked to the integration of a wave of traditional left veterans in the second internal party elections. After 2017 however, there was a relative rejuvenation of party elites: overall, the standard age of CCE and CC members stopped increasing. This is partly due to the integration of new and younger members in 2020 and 2021. This new generation of activists brings new characteristics. First, in the CCE, it has a more limited activist experience than Podemos’ founders: in many cases, its activist socialization relies solely on Podemos or, in some cases, on its newly founded youth organization, Rebeldía [Rebellion], created in 2019. This explanation is consistent with the following figures: since 2020, less than half of CCE members have other organizational experiences outside of Podemos (44% in 2020, 49% in 2021), a drop of nearly 13% compared to 2014. Moreover, when current CCE members have an activist experience outside Podemos, it is usually more limited if compared to 2014 CCE members. This is reflected in the average number of former organizations CCE members have ever been involved in: around 1,2 in 2014 and 2017, it is now around 1. As regards CC members however, generational trends are less linear and fluctuations in average former activism appear to be trendless (with numbers alternating between 62, 50 and 52% between 2014 and 2020, and going back to 62% in 2021). General conclusions on this matter should also be carefully formulated since, taking a closer look at age groups instead of standard age, rejuvenation tendencies appear less clearly: we rather observe a greater distribution of CCE and CC members across all age groups, with the only exception of the 18-24 category.

If we look at Podemos’ CCE, the party can thus be said to have evolved from a political platform in which diverse activist profiles converged, into a political party with its own socializing spaces. This tendency seems less clear when considering CC members. In both institutions however, former communists may have played a significant role in the organization’s trajectory, but this does not imply that Podemos has turned into a crypto-communist party devoid of autonomous culture. Among Podemos cadres, former communists have been and have remained a tiny minority.

Influence of Latin-American veterans [Up]

Podemos’ connections to Latin America have also been an object of scientific and public attention. One of the alleged assumptions of Podemos’ founding members was that Southern Europe was experiencing a “Latino-Americanisation” process (Tarragoni 2019), in which the economic and institutional crisis paved the way for a new type of charismatic and populist political strategy, inspired by the Latin-American examples of “pink-tide” citizen revolutions and Bolivarian governments of the 2000s (Iglesias 2015). This diagnosis was based both on the academic investigations led by Iñigo Errejón prior to founding Podemos (Errejón Galván 2012; Errejón and Mouffe 2015) and, more importantly, on the experience of the Centro de Estudios Políticos y Sociales (CEPS), in which many of the leading Podemos personalities had a work experience (Alcántara Sáez and Rivas Otero 2019; Chazel 2019). The CEPS foundation (created in 1992 and dissolved around 2015) operated as a political consulting agency, which recruited Spanish scholars and activists for temporary missions in support of left-leaning governments and political forces in Latin America, especially in Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador (Martínez Dalmau 2019). This interest for Latin America triggered an extensive media coverage of Podemos’ connections to Venezuela, and even led to financial scandals around the possible illegal funding of Podemos by Hugo Chávez’s and Nicolás Maduro’s governments. Accounts on the relations of Podemos’ top leading figures with Latin America are thus a commonplace of scientific and media discussions but, again, the extent to which these connections have been a defining feature of the organization as a whole remains difficult to estimate. Indeed, what has prevailed here is a top-down approach that focuses only on a few individuals to offer a general narrative on Podemos’ “Latin-American roots” (Cabrera 2015; Schavelzon and Webber 2018). However, the reality of these interactions among party cadres remains under-researched, a blank that this paper helps filling.

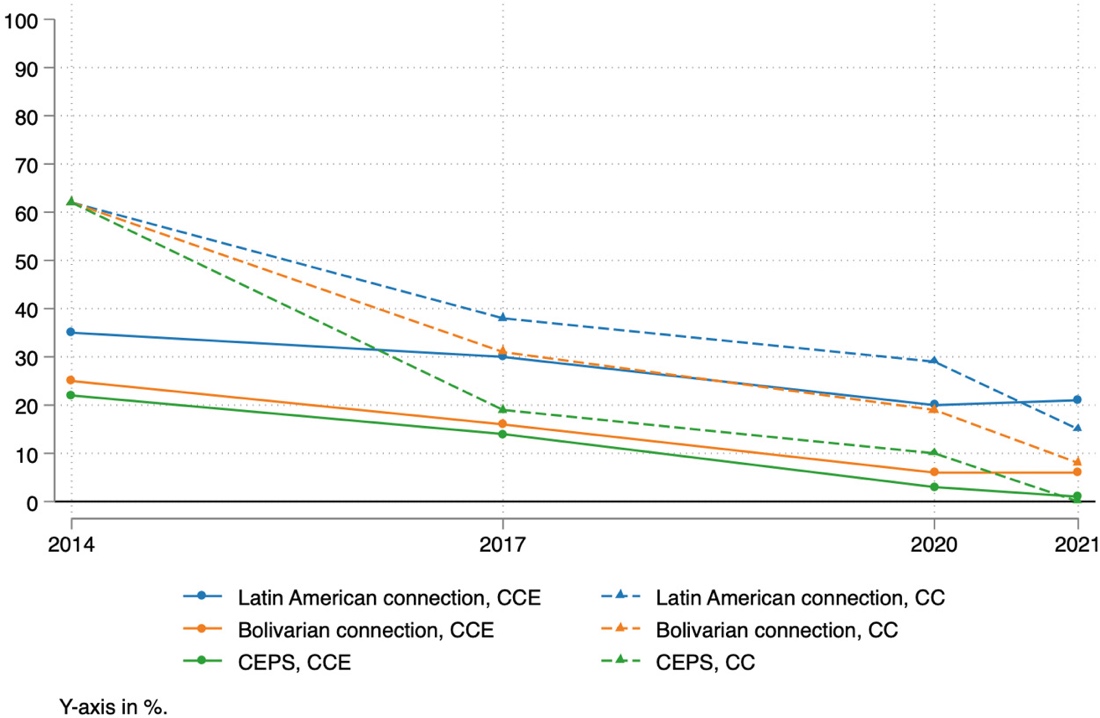

The strong proportion of Latin-American veterans among Podemos cadres in 2014 shown by our prosopographic study is in no way surprising, given the importance of Latin America in European Left imaginaries in general (Andréani 2013; Compagnon 2017). However, the strength of this tendency is striking: Figure 2 (and Tables 2 and 3 in the Appendix) shows that 35% of the Consejo Ciudadano Estatal and 62% of the Consejo de Coordinación founding members had either family ties or had spent a few months/years studying or (in most cases) had a professional experience (from a few weeks to several years) in Latin America.

More interestingly, it can be noted that most of these Latin-American experiences (25% in the CCE), and even all of them in the CC (62%), were concentrated in either Bolivia, Ecuador or Venezuela (which is shown by the “Bolivarian connection” variable), that have or used to have “Bolivarian” governments identified with the radical Left. In the same line, we can confirm that participation in the CEPS was indeed a strong common point not only of Podemos’ top leaders in the CC (62% as well), but also of a significant part (22%) of its intermediate national executives gathered in the CCE.

As Figure 2 points out, after 2017 all these figures show a steady decline: the experience of “left populism” in government ceases to be a defining feature of CCE and CC members’ personal trajectories. Latin-American connections remain high all along (30% in 2017, 20% in 2020 and 21% in 2021 in the CCE; 38% in 2017, 29% in 2020 and 15% in 2021 in the CC), but the relationship is much less intense than it used to be in 2014 (especially in the CC). More specifically, Bolivarian connections decrease steadily in 2017 (16% in the CCE, compared to 25% in 2014; 31% in the CC, compared to 62% in 2014), become very marginal after 2020 in the CCE (6%) and in 2021 in the CC (8%). This decline is even more radical as regards former CEPS members: they used to be decisive when Podemos was founded and have now practically disappeared from the CCE (3% in 2020, 1% in 2021), and totally disappeared from the CC since 2021.

Personal connections to Latin America remain important among party elite members, but this may not be a defining feature of Podemos anymore. In this perspective, Podemos has probably gotten closer to any other Left political organization — especially in Spain, where (for historical, linguistic and cultural reasons) ties with Latin America are stronger than in any other country in Europe, not only among Leftists but in general (Youngs 2000).

Influence of academics [Up]

Podemos’ connections with academia have also been omnipresent in the contextualizing discourse of most research on this organization. The main public figures of the party at its foundation (Pablo Iglesias, Iñigo Errejón, Juan Carlos Monedero, Carolina Bescansa, Luis Alegre, to name just a few) indeed held PhDs in social sciences from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, a traditional centre of left-wing activism in the capital of Spain. Some of them were either full professors (Monedero, Bescansa) or held precarious positions as lecturers in either Spanish (Iglesias) or foreign universities (as was the case of Pablo Bustinduy). Many of the existing work on Podemos devotes at least one section to analyzing these persons’ academic trajectories before they created Podemos, and shows how this impacted on their conceptualization of political action and party strategy (Chazel and Fernández Vázquez 2020; Gómez-Reino and Llamazares 2019). Podemos’ founders are thus usually presented as scientific professionals and political amateurs who, in a context of political turmoil, have crossed sectorial borders to become political professionals — thus providing an example of Michel Dobry’s concept of “desectorization of the social space” under fluid political conjunctures (Dobry 1986). More ethnographic research has also shown that academic experience and expertise have been used as a common legitimizing asset among grassroots activists applying for local responsibilities within Podemos (Nez 2015). However, aside from the two extremes of party organization (main public figures and rank-and-file), no existing research has explored the impact of academic experience on the recruitment of party cadres. Did the social group of academics dominate Podemos’ national elites as a whole, or was their influence restricted to a few selected individuals, the most popular and powerful inside the organization? And how did the presence of academics among party cadres evolve since 2014 and the process of party institutionalization or “normalization” (Mazzolini and Borriello 2022)?

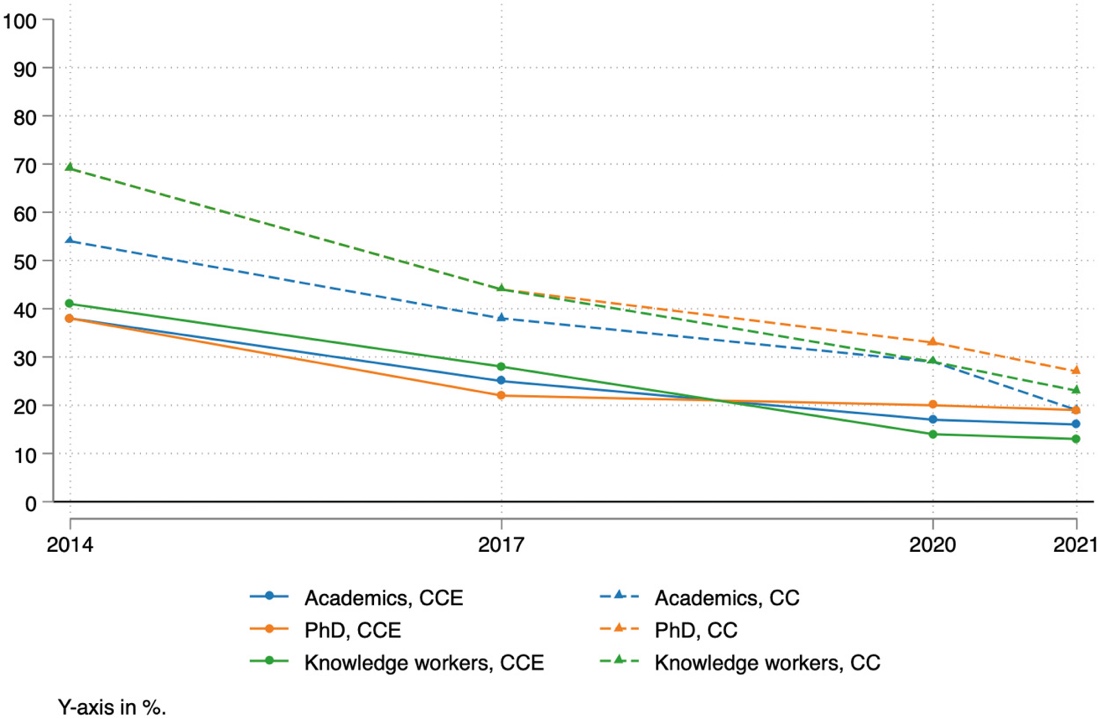

The generalized assumption that there was a strong academic impulse in the foundation of Podemos is confirmed by our prosopographic data. In 2014, as is shown by Tables 2 and 3 in the Appendix, 38% of Consejo Ciudadano Estatal members and 69% of Consejo de Coordinación members were doing or had defended a PhD. Consistently, 38% (CCE) and 54% (CC) of them also had some form of connection to academia, by publishing scientific articles and by teaching regularly or intermittently in a university.

More broadly, there was a strong presence of “knowledge workers” among CCE members, if we consider academics together with teachers (in primary or secondary schools or in other types of institutions) and students (42% in the CCE, 69% in the CC). This figure is particularly interesting if compared to two other types of professional profiles that are traditionally dominant within party elites in general, and in Spain in particular (Tarditi and Vittori 2021): legal professionals (e.g. lawyers) and remunerated politicians (e.g. members of parliament or political staffers). In 2014, these two types of occupation both accounted for only 8% of CCE members, an extremely low figure if compared to mainstream Spanish parties’ central offices (Tarditi and Vittori 2021), not to mention the 0% remunerated politicians in the 2014 CC. This was obviously linked to Podemos’ novelty: with few elected MPs or MEPs, the low proportion of professional politicians is not surprising. It nevertheless confirms the fluid-political conjuncture expectation that Podemos’ CCE composition in 2014, with its strong proportion of knowledge workers, reflected a moment of political crisis during which the field of knowledge and the field of politics became entangled (Dobry 1986). This, in turn, could help explain why these knowledge workers became rarer among Podemos elites after 2017, when both the Spanish political field and Podemos’ structures entered into a new phase of stability. Since 2021, knowledge workers represent a total of only 16% of CCE and 26% of CC members.

Figure 3 shows that there is indeed a sharp decrease in the proportion of academic CCE members, falling from 38% in 2014 to 24% in 2017, and CC members, falling from 54% to 38% in the same period. A similar tendency is observable for people doing or holding PhDs (38 to 21% among CCE members, 69 to 44% among CC members). The reduction goes on until 2021, with only 16% academics among CCE members and 19% among CC members. Actually, the decrease is even stronger than what these figures suggest, since many of those who entered the database as lecturers (and are here registered as such) later became members of the party staff or members of parliament (e.g. Pablo Bustinduy).

In parallel, we can observe interesting evolutions regarding the education variable (see Tables 2 and 3 in the Appendix). While PhDs stop being dominant among CCE members, the presence of people with lower qualifications increases progressively: from 0 to 7% for activists whose education did not exceed high school; from 3 to 7% for activists with a professional diploma (Formación Profesional). Among CC members in turn, people holding Bachelors and Masters become prevalent in 2017 (50% in total), and remain so afterwards (57% in 2020, 61% in 2021). As regards the occupational variable, what compensates for the reduction in the proportion of academics? Here, we can observe a significant increase in the proportion of remunerated politicians, which goes from 8 to 19% between 2014 and 2017 in the CCE, and then keeps rising to 30% in 2020 and 36% in 2021 — in spite of the fact that this variable is underestimated, since we do not update occupations in the database after individuals have entered it. Much more than a third of Podemos’ CCE members actually makes a living through politics (not to mention CC members). This may appear as logical given the conquest of many electoral seats with attached remunerated positions, but it still offers a striking contrast with the original party morphology. In that perspective, it should be highlighted that the increase of remunerated politicians among CCE and CC members does not parallel the increase of electoral seats won by Podemos, but rather surpasses it, since the party in public office, and in particular the number of MPs, which had grown until 2016, has experienced a significant decrease after 2019 (from nearly 70 to 35 MPs for the Unidas Podemos parliamentary group) — a decrease not compensated by the appointment of Podemos cadres as ministers or junior ministers between 2020 and 2023. In other words, the proportion of remunerated politicians has continued to increase in the CCE while their absolute number was more than probably reducing or had stagnated.

To give a simple overview of Podemos’ evolution as regards the academic and professional characteristics of its cadres, it could be said that the organization, which used to be a knowledge-workers party, has now become a party of professionals. In other words, Podemos, born during a generalized political crisis which led to the creation of new forms of political organization, has undergone a process of normalization: the borders of the political field have been restructured, and the borders of partisan activism did likewise. Consequently, the logics of recruitment into the elites have changed. Entering the CCE in particular used to be a form of recompense for unpaid activists. It now constitutes a symbolic reward for Podemos’ permanent staff or is part of a strategy to involve local Podemos leaders and staffers in the national dynamics of the party — a dynamic that is also highlighted by the increasing number of autonomous communities (administrative regions) represented in the CC, and the limitation of Madrid’s over-representation in both the CC and CCE (to be compared with the overall proportion of the Spanish population living in the Madrid region: 14% according to the 2023 census) (see Tables 2 and 3 in the Appendix).

DISCUSSION[Up]

Going back to our previously formulated expectations, we find that #H1 is confirmed, while #H2, #H3 and #H4 are partly confirmed.

As regards #H1, we observe that external sources of legitimacy were strongly reflected in both the Consejo de Coordinación and the Consejo Ciudadano Estatal when Podemos was created in 2014. All the indicators here considered confirm this expectation: most members of Podemos elites’ activist experiences had taken place outside parties represented in parliament; a very high proportion among them had links with Latin America; academics were a massive minority among CCE members and a majority among CC members. All these elements thus point to a high prevalence of political-outsider profiles among Podemos party cadres in 2014.

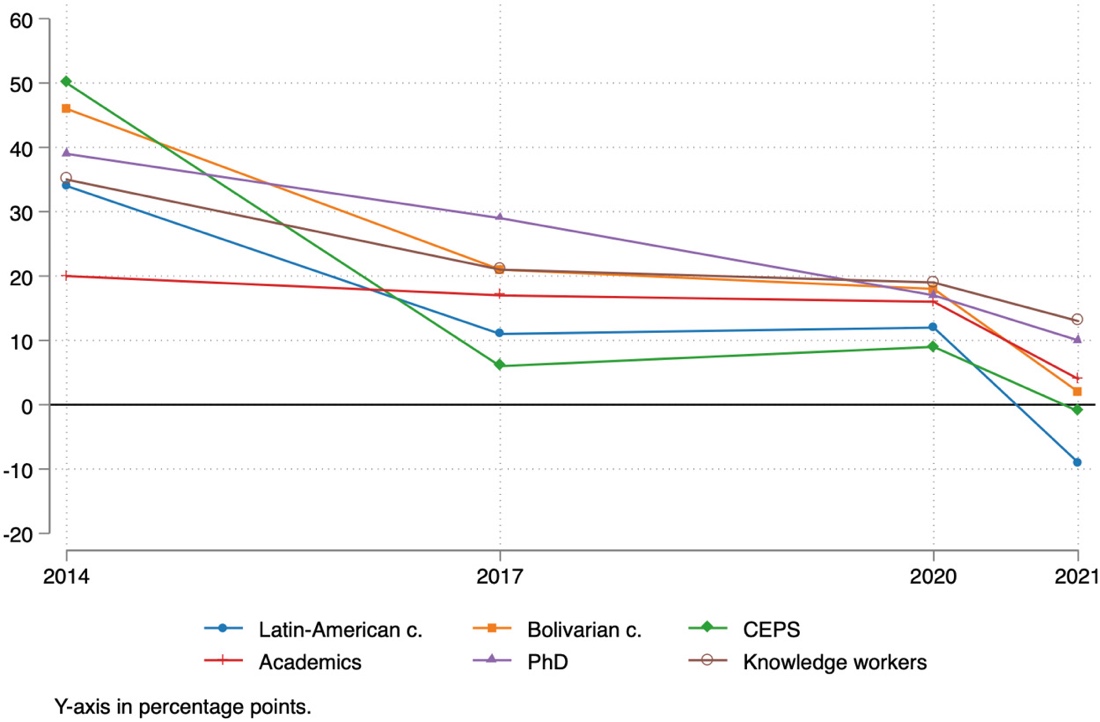

#H2 deals with the impact of external legitimacy assets in internal party promotion in 2014, measured by the difference between scores of CC members, the highest hierarchy in Podemos’ institutions, and scores of CCE members, the intermediate level of national leadership. This expectation is partly confirmed by the prosopographic dataset (see Table 4 in the Appendix): its does not provide consistent results as regards links to social movements, but shows strong correlations between access to the CC and links to academia and Latin America

#H3 deals with the institutionalization of party organization and the transformation of party elite profiles between 2014 and 2021, by analysing trends of party cadre outsider-ness during that period in both the CCE and the CC. In this perspective, party institutionalization should lead to a downward trend of outsider-ness indicators over time, a tendency that we can confirm in two out of three indicators (see Tables 2 and 3 in the Appendix). Our expectation, inconclusive as regards links to social movements, is nevertheless confirmed in relation to the two other indicators. A majority of indicators thus confirm there is a reduction in the outsider profile of Podemos’ elites between 2014 and 2021, associated with the institutionalization of the party; the interactions between elite membership and social movement linkages are more complex to assess here.

#H4, which focuses on the evolution of the gap between the CC and the CCE, is also partly confirmed by the prosopographic dataset (see Figure 4). Unsurprisingly given the confusing trend followed by social movement linkages as analysed with #H3, this indicator also provides limited results in expressing the evolution of differences between CC and CCE members over time (see Table 4 in the Appendix). If we set aside this set of variables, we however find evidence that party outsider-ness ceases being an asset in internal party competition, thus reflecting an increasingly autonomous system of party hierarchies. Indeed, two of the external sources of legitimacy that used to facilitate the access to Podemos elites have lost their influx over time, thus confirming the expectation of an institutionalization process favouring autonomous party hierarchies.

Overall, our evidence suggests that Podemos has undergone a transformation process: founded as a party of outsiders, where external legitimacy assets were strongly valued in party promotion, it has evolved into a more self-centred organization with increasingly thick borders. Value infusion and the autonomization of the party from its environment have made the access to leadership positions more and more difficult to individuals with fewer party credentials. This has made academic experience and links to Latin America less powerful in favouring party promotion, while opening the party hierarchy to more diverse professional/educational profiles and regional origins. Paradoxically, this closure of party elite has made Podemos cadres more similar to the average Spanish citizen on some aspects, while making Podemos a less “alternative” political organization at the same time, since internal promotion is now more closely associated with previous experience in the party than with other assets.

These results can be used to discuss some widely voiced concerns about Podemos after 2017, when many accused the organization of being infiltrated by former communists or even by the PCE, thus backsliding from a “true” citizen-based movement-party into an empty shell manipulated by radical-left apparatchiks, incarnating the “old politics” of the left. This evolution is not confirmed in our empirical analysis of party elite recruitment since 2014, where communists and former communists do not appear as central in the evolutions of Podemos’ cadres taken as a whole. However, our results confirm the idea that Podemos, once so exceptional in its valuing of outsider profiles, has turned more and more into a closed political market, thus displacing political amateurs from its centres of power.

Between 2014 and 2019, this institutionalization process went hand in hand with (first) a growth and (later) a stabilization of electoral support for the party, with the conquest of important positions at the city and regional level, as well as with the access to governmental positions at the national level (Barberà and Barrio 2019). On this matter, Podemos’ trajectory after 2019 has been marked by a quick and strong decay: in the context of less favourable coalition negotiations with its partners on the radical left, Podemos fell from 35 members of parliament in 2019 to only 5 in 2023, and lost all its positions in the national government — most of the city and regional positions of power had already been lost in the meantime. These evolutions raise the issue of the continued institutionalization of Podemos, especially given that our data collection stopped in 2021, when the last party congress (here called Citizen Assembly) took place. Further research on Podemos party cadres should take these evolutions of electoral support into account when analysing the results of the next party congress, which should take place in 2024. These tendencies were nevertheless partly observable since the 2020 Citizen assembly, which was already marked by the slackening of Podemos’ electoral success and a reduction of the number of its MPs (from roughly 70 to 35). However, in 2020 and 2021, this decline in electoral support and reduction of the party in public office (partly compensated by the integration of Podemos into a national governmental coalition) had not coincided with a reaffirmation of external sources of legitimacy in cadre recruitment. The 2024 Citizen assembly may thus offer an interesting viewpoint to observe the continued interactions between different aspects of party institutionalization: electoral success on the one hand, value infusion and autonomy of the party from its environment on the other hand.

These observations can also be connected to a more theoretical discussion on the effects of electoral performance on the institutionalization of political parties. The interactions between electoral success and party organization have predominantly been studied in terms of how a “good” or “strong” organization favours electoral success (Cirhan 2024; Tavits 2012). Our analysis suggests that, following previous research on party organizational strength (Aldrich 1995; Lowry 2009), taking the reverse perspective might offer interesting insights into the recent history of radical left parties, by tracking how and to what extent the fluctuations in electoral results affect party autonomy and value infusion. Good electoral performances usually provide extra resources for the party, enabling it to both offer rewards to political insiders and to integrate outsiders to its elite to maintain the “anti-party” or “party-movement” image of the organization. This is particularly true for newly formed organizations, which include fewer “insiders”, such as Podemos in 2014 and 2017. On the contrary, bad electoral performances may have two contradictory effects. First, the associated reduction in the flow of resources may reduce the ability of the party to provide rewards: it will thus tend to give priority to rewarding “organic” members of the organization over outsider profiles. This could partly account for the evolution of Podemos’ elite recruitment in 2020 and 2021 (a tendency whose coherence should be checked after the next party congress). But the reduction in the flow of resources associated with bad electoral performances may also have a second effect, by creating incentives for the party to reorganize recruitment procedures and, especially in the case of new radical left parties, to re-open the borders of internal competition to outsiders — making efforts to regenerate their original image as “alternative” political movements. Podemos’ evolution from 2014 to 2021 does not show such evolutions, but this should (again) be checked in future CCs and CCEs, since time may have non-linear effects on the strategy of parties confronted to bad electoral performances.

CONCLUSIONS[Up]

Overall, the exploration of the social and political characteristics of Podemos’ Consejo Ciudadano Estatal and Consejo de Coordinación members confirms the idea that, looking beyond the organization’s main individual leaders to take a grasp at national party cadres, this new radical left party was indeed a party with a strong proportion of outsiders when it was created in 2014. If we take aside activism in far-left protest parties with no electoral representation, only a minority among early party cadres had an experience in partisan politics before joining Podemos. Former communist activists such as Pablo Iglesias have played a significant role in party genesis at top leadership levels, but they were nevertheless a minority among national elites. In the meantime, Latin-American veterans and academics had a strong presence in the party, incarnating Podemos’ image of a new party made of outsiders and “ordinary” people, understood as non-professional politicians in particular, and of its consequences on elite recruitment. These last two sets of variables even worked as a bonus in terms of hierarchical distinction between CCE and CC members: having external sources of legitimacy such as links with Latin America and academia increased the probability of reaching top leadership positions in the party.

As regards the evolution of these characteristics, three main tendencies have been identified. First, a new generation of activists who never participated in any other organization has integrated Podemos’ elites after 2014. This reflects the creation and progressive strengthening of a self-sufficient party culture that clearly opposes Podemos’ initial anchorage in a diversity of social movements. Second, there is a decreasing proportion of Latin-American veterans among party elites. Podemos is still a party of Latin-American “nerds”, probably like any other radical left party in Europe, but not with the astonishingly high intensity observed during party genesis. Third, there is a decreasing proportion of academics and knowledge workers among party cadres, compensated by a surge in remunerated politicians, while the other professions remain stable. This can be considered the main sociological evidence of Podemos’ institutionalization or “normalization”, and of the impoverishment of its environmental links: external legitimacy sources play a decreasing role in internal party promotion.

An interesting aspect of these results is that the process of institutionalization of Podemos, here analysed in terms of value infusion and autonomy in the selection of party cadres, coincides with a deterioration of Podemos’ electoral performances. If this partly surprising correlation is to be confirmed in the next Podemos Citizen Assembly, as could be expected after the drastic reduction of Podemos’ share of MPs in the 2023 Spanish national elections, it could fuel further research on the complex interactions between different faces of party institutionalization that are often seen as convergent: electoral success and growth of the party in public office on the one hand, autonomy and value infusion on the other hand.

These reflections could also pave the way for further comparative research on new RLPs and their trajectories of institutionalization. Replicating our prosopographic approach of Podemos cadres to other organizations could help generate knowledge on the value attributed to outsider-ness within different parties, and its evolutions over time. More specifically, this comparative approach could help measure and differentiate the effect of two different variables on the evolving dynamics of elite recruitment: time and changing electoral performances. Indeed, to the extent that they show the negative effects of institutionalization on the “outsider-ness” of RLP cadres’ social profiles, our observations go beyond the simple Podemos case-study. All else being equal, it can be expected that the sociology of elites of new European RLPs will show a similar trajectory as regards linkage to social movements and academia over time, confirming hypotheses already formulated by the literature on other aspects of party life (Groz 2020; March 2017; Tsakatika and Lisi 2013). The case of Latin American influence and “veteranship” may be a little different, since its magnitude in Podemos’ formative years seems quite sui generis: ongoing research on other European parties such as La France Insoumise however tends to show this dynamic may also be observable outside Spain (Copello 2022). Further research comparing the sociology of RLP cadres could help enrich these promising insights, either by operationalizing the exact same indicators in other parties, or by using other indicators of cadre “outsider-ness” adapted to context specificities. Apart from confirming the effects of time on party closure, undertaking comparative research on RLPs could also help understand the exact role played by (good or bad) electoral performances in the shaping of party organization and the ability of the party to open its elite circles to political outsiders.

Such replications to other case-studies might however face major challenges, not so much because of local/national specificities of Podemos as regards external sources of legitimacy, but in relation with data-building possibilities. Indeed, in spite of its quick process of verticalization, Podemos has maintained transparent election processes to select its national elites, making a systematic data-based analysis possible. This is not necessarily the case in other emblematic European radical left movements such as La France Insoumise or the Parti du Travail de Belgique, with higher levels of informality, co-optation and secrecy and lower levels of synchronization in the selection of party cadres. Future systematic research into the sociology and trajectories of RLP cadres will thus be conditioned by the parties’ diverse modes of organization — a variable that is itself an element to be analysed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS[Up]

The author wishes to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier versions of this article. This paper was first presented to the Spanish Politics Specialist Group at the 2022 Political Studies Association Conference at the University of York. The comments received in this context, as well as the thorough discussions undertaken with Paul Brandily were crucial in the drafting of subsequent versions.

This work was funded by CY Generations, a programme supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR) under the French government grant: “Investissements d’avenir” #France2030 (ANR-21-EXES-0008).

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS[Up]

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

NOTES[Up]

| [1] |

Before 2020, the CC was labeled “Secretaría” [Secretariat]. However, in this article, this institution will always be referred to as CC. |

| [2] |

Except for one individual exception in 2017, all members of the CC have always been members of the CCE at the same time. |

| [3] |

The anonymised dataset is available online as supplementary material. |

| [4] |

Membership in Izquierda Unida (IU) itself was not included in our ‘Former communists’ category, since organisations with a distinct ideological profile have also been involved in that coalition, such as Espacio Alternativo (1998-2007), which had strong links with Trotskyist networks and social movements. However, all the aforementioned organisations (PCE, PSUC, UJCE and JCC) have been part of IU networks. |

References[Up]

|

Alcántara Sáez, Manuel, and José Manuel Rivas Otero, eds. 2019. Los Orígenes Latinoamericanos de Podemos. Madrid: Tecnos. |

|

|

Aldrich, John H. 1995. Why Parties? The Origin and Transformation of Political Parties in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. |

|

|

Andréani, Fabrice. 2013. “Du Nomadisme Idéologique à l’allégeance Partisane : Les Mondes Franco-Vénézuéliens de La Réélection de Hugo Chávez (2012).”Critique Internationale, no. 2: 119-32. |

|

|

Anticapitalistas En Podemos: Construyendo Poder Popular. 2016. Barcelona: Sylone. |

|

|

Barberà, Oscar, and Astrid Barrio. 2019. “Podemos’ and Ciudadanos’ Multi-Level Institutionalization Challenges.”Zeitschrift Für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 13 (2): 249-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-019-00423-7. |

|

|

Barberà, Oscar, Astrid Barrio, and Juan Rodríguez-Teruel. 2019. “New Parties’ Linkages with External Groups and Civil Society in Spain: A Preliminary Assessment.”Mediterranean Politics 24 (5): 646-64. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2018.1428146. |

|

|

Bolleyer, Nicole. 2023. “Party Institutionalisation.” In The Routledge Handbook of Political Parties, edited by Neil Carter, Daniel Keith, Gyda Sindre, and Sofia Vasilopoulou, 78-89. London: Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429263859-10/party-institutionalisation-nicole-bolleyer. |

|

|

Bortun, Vladimir. 2019. “Transnational Networking and Cooperation among Neo-Reformist Left Parties in Southern Europe during the Eurozone Crisis: SYRIZA, Bloco and Podemos.” PhD Thesis, University of Portsmouth. |

|

|

Cabrera, Luis Martín. 2015. “Podemos, El Partido Que Vino de América Latina: Balances y Desafíos de La Transformación Política En España.” Rebelión. June 25, 2015. http://www.rebelion.org/noticia.php?id=200390. |

|

|

Calvo, Kerman, and Iago Álvarez. 2015. “Limitaciones y Exclusiones En La Institucionalización de La Indignación: Del 15-M a Podemos.”RES. Revista Española de Sociología, no. 24: 115-22. |

|

|

Casero-Ripollés, Andreu, Marçal Sintes-Olivella, and Pere Franch. 2017. “The Populist Political Communication Style in Action: Podemos’s Issues and Functions on Twitter during the 2016 Spanish General Election.”American Behavioral Scientist 61 (9): 986-1001. |

|

|

Cervera-Marzal, Manuel. 2021. Le Populisme de Gauche : Sociologie de La France Insoumise. Paris: La Découverte. |

|

|

Chazel, Laura. 2019. “De l’Amérique Latine à Madrid : Podemos et la construction d’un « populisme de gauche ».”Pôle Sud 50 (1): 121-38. https://doi.org/10.3917/psud.050.0121. |

|

|

Chazel, Laura, and Guillermo Fernández Vázquez. 2020. “Podemos, at the Origins of the Internal Conflicts around the ‘Populist Hypothesis.’”European Politics and Society 21 (1): 1-16. |

|

|

Chironi, Daniela. 2018. “Radical Left Parties and Social Movements : Strategic Interactions.” Thesis, Florence: European University Institute. https://doi.org/10.2870/60973. |

|

|

Chironi, Daniela, and Raffaella Fittipaldi. 2017. “Social Movements and New Forms of Political Organization: Podemos as a Hybrid Party.”Partecipazione e Conflitto 10 (1): 275-305. |

|

|

Cirhan, Tomáš. 2024. Party Organization and Electoral Success of New Anti-Establishment Parties. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. |

|

|

Compagnon, Olivier. 2017. “Le populisme en son terreau latino-américain.”Bulletin de l’Association pour le Développement de l’Histoire Culturelle, 40-46. |

|

|

Copello, David. 2022. “L’Amérique Latine Vue Par Les Militant .e.s de La France Insoumise et Podemos.” CY Cergy Paris Université. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03661127. |

|

|

Dain, Vincent. 2020. Podemos Par Le Bas : Trajectoires et Imaginaires de Militants Andalous. Nancy: Arbre Bleu éditions. |

|

|

Della Porta, Donatella, Joseba Fernández, Hara Kouki, and Lorenzo Mosca. 2017. Movement Parties against Austerity. Cambridge: Polity. |

|

|

Dobry, Michel. 1986. Sociologie Des Crises Politiques. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po. |

|

|

Dominguez, Francisco. 2017. “Latin America and the European Left.”Transform: A Journal of the Radical Left, no. 1: 25-58. |

|

|

Errejón Galván, Iñigo. 2012. “La Lucha Por La Hegemonía Durante El Primer Gobierno Del MAS En Bolivia (2006-2009): Un Análisis Discursivo.” Thesis, Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid. |

|

|

Errejón, Iñigo. 2021. Con Todo: De Los Años Veloces al Futuro. Madrid: Planeta. |

|

|

Errejón, Iñigo, and Chantal Mouffe. 2015. Construir Pueblo: Hegemonía y Radicalización de La Democracia. Barcelona: Icaria. |

|

|

Gerbaudo, Paolo. 2021. “Are Digital Parties More Democratic than Traditional Parties? Evaluating Podemos and Movimento 5 Stelle’s Online Decision-Making Platforms.”Party Politics 27 (4): 730-42. |

|

|

Gomez, Raul, Laura Morales, and Luis Ramiro. 2016. “Varieties of Radicalism: Examining the Diversity of Radical Left Parties and Voters in Western Europe.”West European Politics 39 (2): 351-79. |

|

|

Gomez, Raul, and Luis Ramiro. 2019. “The Limits of Organizational Innovation and Multi-Speed Membership: Podemos and Its New Forms of Party Membership.”Party Politics 25 (4): 534-46. |

|

|

Gómez-Reino, Margarita, and Iván Llamazares. 2019. “Populism in Spain: The Role of Ideational Change in Podemos.” In The Ideational Approach to Populism, edited by Kirk Hawkins, Ryan Carlin, Levente Littvay, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, 320-36. New York: Routledge. |

|

|

Groz, Arthur. 2020. “L’Institutionnalisation des nouveaux partis contestataires d’Europe du Sud au prisme des carrières militantes : Une étude comparée de Syriza, Podemos et la France insoumise.” Phdthesis, Université Montpellier. https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03136468. |

|

|

Harmel, Robert, Lars G. Svåsand, and Hilmar Mjelde. 2019. “Party Institutionalisation: Concepts and Indicators.” In Institutionalisation of Political Parties: Comparative Cases, edited by Robert Harmel and Lars G. Svåsand, 9-24. Colchester: ECPR Press. |

|

|

Huntington, Samuel. 1968. Political Order in Changing Societies. New Haven: Yale University Press. |

|

|

Iglesias, Pablo. 2015. “Understanding Podemos.”New Left Review, no. 93: 8-22. |

|

|

Iglesias Turrión, Pablo. 2009. “Multitud y Acción Colectiva Postnacional: Un Estudio Comparado de Los Desobedientes: De Italia a Madrid (2000-2005).” Thesis, Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid. |

|

|

Katsambekis, Giorgos, and Alexandros Kioupkiolis, eds. 2019. The Populist Radical Left in Europe. London: Routledge. |

|

|

Katz, Richard S., and Peter Mair. 1993. “The Evolution of Party Organizations in Europe: The Three Faces of Party Organization.”American Review of Politics 14: 593-617. https://doi.org/10.15763/issn.2374-7781.1993.14.0.593-617. |

|

|

Keith, Daniel, and Luke March. 2016. “The European Radical Left: Past, Present, No Future?” In Europe’s Radical Left: From Marginality to the Mainstream?, edited by Luke March and Daniel Keith, 353-79. London: Rowman & Littlefield. |

|

|

Kioupkiolis, Alexandros, and Giorgos Katsambekis. 2018. “Radical Left Populism from the Margins to the Mainstream: A Comparison of Syriza and Podemos.” In Podemos and the New Political Cycle: Left-Wing Populism and Anti-Establishment Politics, edited by Óscar García Agustín and Marco Briziarelli, 201-26. Cham: Springer International Publishing. |

|

|

Krause, Werner. 2020. “Appearing Moderate or Radical? Radical Left Party Success and the Two-Dimensional Political Space.”West European Politics 43 (7): 1365-87. |

|

|

Lisi, Marco. 2019. “Party Innovation, Hybridization and the Crisis: The Case of Podemos.”Italian Political Science Review / Rivista Italiana Di Scienza Politica 49 (3): 245-62. |

|

|

Lourenço, Pedro. 2021. “Studying European Radical Left Parties since the Fall of the Berlin Wall (1990-2019): A Scoping Review.”Swiss Political Science Review 27 (4): 754-77. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12478. |

|

|

Lowry, Robert. 2009. “The Dynamic Relationship between State Party Organizational Strength and Electoral Outcomes.” In Toronto, Ontario. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1458550. |

|

|

March, Luke. 2011. Radical Left Parties in Europe. Abingdon: Routledge. |

|

|

March, Luke, and Daniel Keith. 2016. Europe’s Radical Left: From Marginality to the Mainstream? Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield International. |

|

|

March, Luke. 2017. “Radical Left Parties and Movements : Allies, Associates, or Antagonists?” In Radical Left Movements in Europe, edited by Magnus Wennerhag, Christian Fröhlich, and Grzegorz Piotrowski, 23-42. London: Routledge. |

|

|

March, Luke, and Charlotte Rommerskirchen. 2015. “Out of Left Field? Explaining the Variable Electoral Success of European Radical Left Parties.”Party Politics 21 (1): 40-53. |

|

|

Martínez Dalmau, Rubén. 2019. “El Centro de Estudios Políticos y Sociales: Una Experiencia de Mutuo Aprendizaje.” In Los Orígenes Latinoamericanos de Podemos, edited by Manuel Alcántara Sáez and José Manuel Rivas Otero, 111-34. Madrid: Tecnos. |

|

|

May, John D. 1973. “Opinion Structure of Political Parties: The Special Law of Curvilinear Disparity.”Political Studies 21 (2): 135-51. https://doi.org/10.1111/ j.1467-9248.1973.tb01423.x. |

|

|

Mazzolini, Samuele, and Arthur Borriello. 2022. “The Normalization of Left Populism? The Paradigmatic Case of Podemos.”European Politics and Society 23 (3): 285-300. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2020.1868849. |

|

|

Nadal, Lluis de. 2021a. “Populism and Plebiscitarianism 2.0: How Podemos Used Digital Platforms for Organization and Decision-Making.”New Media & Society, no. online first. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211038763. |

|

|

Nadal, Lluis de. 2021b. “On Populism and Social Movements: From the Indignados to Podemos.”Social Movement Studies 20 (1): 36-56. |

|

|

Nez, Héloïse. 2015. Podemos, de l’indignation Aux Élections. Paris: Les Petits Matins. |

|

|

Nez, Héloïse. 2022. Démocratie Réelle : L’héritage Des Indignés Espagnols. Vulaines sur Seine: Editions du Croquant. |

|

|

Panebianco, Angelo. 1988. Political Parties: Organization and Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

|

|

Petithomme, Mathieu. 2020. “Political Innovations and Democratic Participation within Podemos in Spain.” In Innovations, Reinvented Politics and Representative Democracy, edited by Agnès Alexandre-Collier, Alexandra Goujon, and Guillaume Gourgues, 91-104. New York: Routledge. |

|

|

Petithomme, Mathieu. 2021. Génération Podemos : Sociologie Politique d’un Parti Indigné. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. |

|

|

Plaza-Colodro, Carolina, and Luis Ramiro. 2023. “Spain.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Radical Left Parties in Europe, edited by Fabien Escalona, Daniel Keith, and Luke March, 481-513. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-56264-7_17. |

|

|

Ramiro, Luis, and Raul Gomez. 2017. “Radical-Left Populism during the Great Recession: Podemos and Its Competition with the Established Radical Left.”Political Studies 65 (1_suppl): 108-26. |

|

|

Randall, Vicky, and Lars Svåsand. 2002. “Party Institutionalization in New Democracies.”Party Politics 8 (1): 5-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068802008001001. |

|

|

Rioufreyt, Thibaut. 2016. Les Socialistes Français Face à La Troisième Voie Britannique : Vers Un Social-Libéralisme à La Française (1997-2015). Grenoble: Presses Universitaires de Grenoble. |

|

|

Schavelzon, Salvador, and Jeffrey Webber. 2018. “Podemos and Latin America.” In Podemos and the New Political Cycle: Left-Wing Populism and Anti-Establishment Politics, edited by Oscar García Agustín and Marco Briziarelli, 173-299. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. |

|

|

Scheltiens Ortigosa, Vincent. 2021. “Podemos, du mouvement au parti. Chronique d’une désillusion.”La Revue Nouvelle 4 (4): 38-44. |

|

|