Deconstructing geopolitics in the classroom. Grasping geopolitical codes through active learning

Deconstruyendo la geopolítica en el aula. La comprensión de los códigos geopolíticos a través el aprendizaje activo

ABSTRACT

This article describes an activity I designed to allow students to grasp critical approaches in Geopolitics better. The activity is focused on the deconstruction of the US’ geopolitical code regarding the 2003 intervention in Iraq. The article describes the activity, and then evaluates students’ learning through four different kinds of review and assessment. Overall, the different assessments show that students managed to achieve the main learning outcomes of the activity —i.e., being able to reflect on this geopolitical code as a social construction legitimizing military action. These assessments also show that students are able to apply what they learned in this specific activity to other geopolitical discourses —thus showing how the activity helps them develop critical thinking outside the classroom. In this sense, the article concludes that active learning can be helpful for instructors teaching critical approaches in International Relations or other similar fields. Having students working with their knowledge allows learners to understand better how to produce critical analyses and to grasp their political weight.

Keywords: active learning, Geopolitics, critical pedagogy, critical approaches in IR, geopolitical codes.

RESUMEN

Este artículo describe una actividad que diseñé para que los alumnos comprendieran mejor los enfoques críticos de la geopolítica. La actividad se centra en la deconstrucción del código geopolítico de Estados Unidos en relación con la intervención de 2003 en Irak. El artículo describe la actividad y, a continuación, evalúa el aprendizaje de los alumnos mediante cuatro tipos diferentes de revisión y evaluación. En general, las distintas evaluaciones muestran que los alumnos lograron alcanzar los principales resultados de aprendizaje de la actividad; es decir, ser capaces de reflexionar sobre este código geopolítico como construcción social que legitima la acción militar. Estas evaluaciones también muestran que los estudiantes son capaces de aplicar lo aprendido en esta actividad específica a otros discursos geopolíticos, mostrando así cómo la actividad les ayuda a desarrollar un pensamiento crítico fuera del aula. En este sentido, el artículo concluye que el aprendizaje activo puede ser útil para los instructores que enseñan enfoques críticos en relaciones internacionales u otros campos similares. Hacer que los estudiantes trabajen con sus conocimientos permite a los alumnos comprender mejor cómo producir análisis críticos y captar su peso político.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje activo, geopolítica, pedagogía crítica, enfoques críticos en RRII, códigos geopolíticos.

CONTENTS

- ABSTRACT

- RESUMEN

- INTRODUCTION

- APPROACHING THE WORLD DIFFERENTLY: ESSENTIALIST AND CRITICAL GEOPOLITICS EXPLAINING GEOPOLITICAL CODES

- CRITICAL PEDAGOGY AS A PEDAGOGICAL APPROACH

- DECONSTRUCTING GEOPOLITICS IN THE CLASSROOM: THE 2003 US GEOPOLITICAL CODE

- CONCLUSION

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- NOTES

- References

- ANNEX

INTRODUCTION [Up]

In International Relations (IR), Geopolitics, and other related fields of study, constructivist and critical approaches may be challenging to understand for students, because of the different ontologies and epistemologies that underpin them and their focus on ideational elements (Ishiyama et al., 2015). Starting from this reflection, in this article, I argue that active learning may be a useful tool for instructors when teaching postpositivist approaches in IR, Geopolitics, or related fields. By leading students to work with their knowledge and apply it, active learning allows them to grasp ideational and discursive elements of politics and reflect on how they work together to shape international relations (Lamy, 2007). Therefore, this article describes an activity I conducted with my students and, by doing so, reflects and assesses students’ learning through active learning methodologies.

Specifically, the participants were 4th year students of a double BA in International Relations and Global Communication at the Universidad Pontificia Comillas. Therefore, they had a solid background in IR and an interest for political discourses and communication. The activity I elaborated focused on the 2003 US’ intervention in Iraq as a geopolitical code (Li, 2020). Through the activity, they were guided to reflect on the 2003 US’ geopolitical code as an active discursive construction of Iraq and the Middle East at the bases of the legitimization of the military intervention. The activity was conducted in my module on Geopolitics, but, because of this intersection of different discourses, it may be suited for different IR modules that deal with constructivist and critical approaches to foreign policies, the WOT, or military interventions and international security (Campbell, 1998; Jackson, 2005).

Furthermore, the learning outcomes are in line with one that is usually included in many IR Syllabi —i.e., developing students’ critical thinking (Khan and Gabriel, 2018). Broadly speaking, in IR and Geopolitics, developing students’ critical thinking implies guiding students to questioning and challenging the main categories used to make sense of international politics (and reality) and to help them engage with what is presented as natural, neutral, and objective and question its political consequences (id.). In this sense, the deconstruction of the discourses shaping the 2003 US’ geopolitical code is in line with this broader objective.

The article is divided into a theoretical and a practical section. In the former, I start with a discussion of essentialist and critical approaches in Geopolitics and IR and a description of “geopolitical codes” as a theoretical tool. I then discuss critical pedagogy to illustrate the bottom-line pedagogical approach I adopt in my teaching. Here, I explain how Critical Pedagogy focuses on challenging students’ naturalized views of the world and reality, and on giving them the tools to identify and problematize the power relations that structure politics (Díaz Sanz and Ferreiro Prado, 2021; Khan and Gabriel, 2018; Giroux, 2012). After some methodological remarks, the second part of the article illustrates the activity and the results obtained from the students. And, a last section offers some general conclusions.

APPROACHING THE WORLD DIFFERENTLY: ESSENTIALIST AND CRITICAL GEOPOLITICS EXPLAINING GEOPOLITICAL CODES[Up]

My module on Geopolitics is a ten sessions course —therefore, a very short one. Overall, I plan the module with the objective of bringing students to question naturalized geopolitical categories and reflect on their political consequences. To achieve this goal, each session raises, little by little, the critical engagement required. The module ends with the activity described because this allows students to apply the knowledge they acquired and consolidate it. Also, the activity allows me to assess whether they have acquired critical thinking skills and whether they are able to apply them independently from my guidance —and thus, outside the narrow context of the classroom. Therefore, throughout the module, I simplify and summarize scholarly debates and structure my teaching around the two main theoretical approaches that shape Geopolitics —i.e., essentialist and critical understandings of (geo-)politics (Dodds, 2019). To allow students to grasp these approaches better, I guide them to link them with their broad knowledge of IR theories —i.e., positivist and constructivist approaches in IR.

On the one hand, I explain that mainstream Geopolitics mostly understands that countries’ international political behavior is shaped and molded by their geographical and territorial characteristics (Dodds, 2019; Ó Tuathail, 1998a, 1998b, 1996; Agnew, 1998). Geopolitically speaking, this means that its geographical characteristics influence its international behavior and shape it in a very specific way (Dodds, 2019; Díaz Sanz, 2019). From this perspective, resounding with mostly Neorealist understandings in IR, the state is considered a rational actor that rationally formulates its foreign policies and decides on its international political behavior —also influenced by its geopolitical position.

On the other hand, I present Critical Geopolitics as an approach that is closer to constructivism in IR. While not rejecting the importance of geography, this approach focuses on the social construction of reality and, in turn, on the social interpretations of politics (Dodds, 2019; Ó Tuathail, 1998a, 1998b, 1996; Agnew, 1998). Among other things, Critical Geopolitics looks at geopolitics and its categories as social constructions that, among other elements, are produced, maintained, and legitimized through political discourses and practices (Díaz Sanz, 2019: 40). Geopolitics, therefore, can be understood as a discourse about the world that permits the exercise of power (Agnew, 1998). A part of Critical Geopolitics works, thus, focus on the deconstruction of political discourses and hegemonic geopolitical categories —that produce and reproduce relations of power (Dodds, 2019; Ó Tuathail, 1998a; 1998b; 1996; Agnew, 1998). To illustrate this theoretical reflection with a practical example, I invite students to collectively reflect on the geopolitical category of the “Middle East”.

Studying the Middle East from an essentialist and a critical perspective [Up]

Using the “Middle East” as an example, the students and I reflect together and try to pinpoint what could be the differences in approaching this area of the world from these two perspectives. Essentialist geopolitics would usually focus on the Middle East as a —not too problematic— existing geopolitical category (Bilgin, 2004). Overall, they would aim to produce regional analyses, formulate politics and policies toward the region and its future (Dodds, 2019).

On the other hand, Critical Geopolitics mostly focuses on deconstructing the category of the Middle East and problematizing its naturalization (Díaz Sanz, 2019; Cairo Carou, 2016; Culcasi, 2010; Bilgin, 2004). Critical geopolitics reflects on the political consequences of this social construct while destabilizing and denaturalizing it (Díaz Sanz, 2019; Cairo Carou, 2016). Here, critical geopolitics is interested in how these narratives allow the exercise of power relations and thus shape political practices. Linking it also to constructivist and postcolonial approaches in IR, my session focuses on how the category of the Middle East is a social construct with Eurocentric roots —thus embedded in geo-political relations of power from the very moment in which it was coined (Bilgin, 2004; Said, 1978). Scrutinizing it as a social construct allows the group to reflect on the homogenizing consequences this category has (Said, 1978) —i.e., on how it (re)produces a certain understanding of these countries and region (Cairo Carou, 2016; Culcasi, 2010).

Here, students reflect on how the discursive construction of the Middle East —e.g., as a dangerous, conflict-ridden region governed mostly by authoritarian rulers— allows and legitimizes certain political postures and practices towards the region (Li, 2020; Jackson, 2005; Campbell, 1998). At the same time, as constructivist and postcolonial approaches in IR remind us, they also reflect on how these discourses construct the Middle East as the “Other”, while also shaping the formation of the “Self” —i.e., in this case, the West (Culcasi, 2010; Said, 1978)— and reifying and legitimizing both categories. Therefore, this part of the module marks the beginning of the reflection on foreign policies as an active process of construction of the region. The session that follows deals with geopolitical codes.

Geopolitical codes [Up]

Taylor and Flint define geopolitical codes as “the manner in which a country orientates itself towards/in the world” (Flint and Taylor, 2018: 62; Flint, 2017: 52). Put it differently, “geopolitical codes” is a theoretical tool used to identify the geopolitical considerations at the basis of a country’s formulation of its foreign policies (id.). Flint and Taylor describe five calculations that are at the basis of each country’s foreign policy decision:

-

Who are our current and potential allies?

-

How can we maintain our allies and nurture potential allies?

-

Who are our current and potential enemies?

-

How can we counter enemies and emerging threats?

-

How do we justify the four calculations above to our public and to the global community?

Here, students learn that the essentialist-critical debate is reproduced (Flint and Taylor, 2018). Essentialists understand that the formulation of a country’s geopolitical code is a rational process based on specific calculations driven by political and strategic interests and, for example, alliances (Flint, 2017: 52). Geopolitical codes, thus, “reflect national interests” and can be analyzed as rational processes of decision-making (Flint and Taylor, 2018: 62; Flint, 2017: 52). Contrastingly, critical scholars understand them as social and discursive constructions. These are mostly produced by political leaders, military leaders, intellectuals and other social actors, but, as discourses, they also circulate in societies and intersect with other discourses in society —e.g., the ones constructing geopolitical categories (Agnew, 1998; Flint and Taylor, 2018).

Ó Tuathail argues that geopolitical codes are geopolitical practices, discourses, and narratives and, as such, they are “political and cultural ways of describing, representing, and writing geography and international politics” (Ó Tuathail, 1998a: 3). He adds that friends and enemies are never given, but they are the result of a discursive process of identification and construction, and it is this same process that legitimizes, justifies and proscribes the implementation of certain politics and policies over others (Ó Tuathail, 1998a: 3; 1998b). Furthermore, discourses are key gears of the geopolitical mechanisms of identity formation, and as such, they (re)articulate the categories of “I/we” vs “they/the Other” (Ó Tuathail, 1996: 14). Therefore, among other tasks, critical scholars analyze and deconstruct geopolitical discourses and the meanings these discourses (re)articulate to, for example, legitimize the designation of friends and enemies and the “political action plan” to follow. In this case, a critical approach to geopolitical codes would ask different questions that I have summed up for students in the following way:

-

How are friends described and represented? What adjectives are used to talk about friends? What are the categories used to discursively construct friends as friends?

-

What are the political consequences of these representations? What is the action plan to be adopted/that is legitimized here? What and how are politics and policies justified and legitimized through these representations?

-

How are enemies described and represented? What adjectives are used to talk about enemies? What are the categories used to discursively construct enemies as enemies?

-

What are the political consequences of these representations? What is the action plan to be adopted/that is legitimized here? What and how are politics and policies justified and legitimized through these representations?

Therefore, broadly speaking, critical approaches in IR and Geopolitics focus on deconstructing political discourses and their political consequences, also shedding light on the power relations they are embedded in but also reproduce. It is because of these reasons that I consider that critical approaches allow students to develop their critical thinking. It is also because of this reason that I position my pedagogical approach to education within the Critical Pedagogy framework, as I discuss below.

CRITICAL PEDAGOGY AS A PEDAGOGICAL APPROACH[Up]

Critical Pedagogy is a pedagogical approach that aims to develop students’ critical thinking with the overall goal of social emancipation (Khan and Gabriel, 2018; Deardoff, 2013). In other words, instructors that understand that developing their students’ critical thinking involves bringing them to question the naturalization of power relations in the social world may align themselves with the intellectual, practical, and political pedagogical approach proposed by Critical Pedagogy. Here, education is understood both as a locus of reproduction of these power relations and as a sphere where these can be countered and, overall, a locus where it is possible to work for societal transformation and emancipation (Khan and Gabriel, 2018; Giroux, 2012).

In order to achieve this, it is essential to understand the teacher-student role as horizontally as possible (Khan and Gabriel, 2018; Deardoff, 2013). In other words, the role of the instructor is understood mostly as a facilitator of the learning experience as Critical Pedagogy is an approach to learning that builds on Social Constructivism in Pedagogy —i.e., the comprehension that learning is a dynamic, active, and social process that happens in various ways through collaborations that are embedded in social contexts such as the classroom (Devlin, 2006; Bonwell and Eison, 1991). Learners construct their own knowledge through a wide variety of processes and interactions, and they are active masters in building their own knowledge. Therefore, lectures are decentered from the instructor to the students (id.), and learning methods are active —what the students do is key because it is by doing that they construct their own knowledge (McCarthy and Anderson, 2000).

Furthermore, Critical Pedagogy is based on emancipatory agenda of denaturalizing power relations (Devlin, 2006; Bonwell and Eison, 1991). This does not imply that the teaching needs to focus on class, gender, and race or, as in this case, Orientalist constructions of the Other. Rather, the teaching needs to create the space for students to encounter these dynamics while focusing on the various topics that compose the module (Khan and Gabriel, 2018). Here, the instructor guides students through a process of mutual “coming to awareness” of power dynamics that students will be able to take away “from the classroom” into “the real world” (Giroux, 2020: 7).

It is with this in mind that I designed the specific activity described hereunder with the intention to guide students to challenge the construction of the geopolitical codes used to legitimize the intervention in Iraq in 2003 (Li, 2020) —an activity that led students to question and challenge hegemonic constructions that reproduce power relations in geopolitics.

DECONSTRUCTING GEOPOLITICS IN THE CLASSROOM: THE 2003 US GEOPOLITICAL CODE[Up]

This part focuses mostly on describing and evaluating the active learning session. The activity was carried out in the first semester of the academic year 2020/2021, therefore, it took place through a blended teaching modality because of the pandemic. This means that half of the group was present in the classroom, while the other half was following the lecture in streaming.

Whether the blended modality of teaching and had an impact on the development of the activity and students’ work is something that goes beyond the scope of this article. The activity was never carried out in a different format, so a real comparison is not possible. However, whether the blended or face-to-face modality affect its development and students’ learning could be an interesting line for future, comparative research in teaching innovation.

Overall, I was concerned about the impact the blended modality could have on students’ involvement and engagement —as online dynamics can be sometimes alienating for BA students and more challenging to manage for the instructor (Deardoff, 2013). Therefore, I decided to have the whole class working together in breakout rooms in Blackboard collaborate (interacting through the chat and video calls) and they shared the results on Moodle.

This dynamic was chosen to give the “feeling of the classroom” to students working from home and mitigate the alienation students following the lecture online may experience (Mills and Alexander, 2013). This solution seemed to work well as students in the classroom encouraged participation from the ones online —something that for the lecturer may reveal more challenging because of the power relations shaping the instructor-student relation. Here, students in the classroom took the lead on the technical aspects —e.g., in some cases, even managing the virtual room— and guided the discussion to include students online and, thus, returning very smooth groups’ work dynamics.

In this section, I detail the pedagogical reasoning beyond the structure of the activity and, in the second part, I evaluate whether the activity was effective. The session was structured around the OPAR pillars —i.e., Orienting, Presenting. Activity, Review (Petty, 2022). See also Annex 1.

Aims of the session and intended learning outcomes [Up]

As said, throughout the module, my main aim is to guide students to question the main geopolitical categories and thinking present in politics nowadays and to reflect on their political weight. More specifically, the intended learning outcomes (ILOs) for the activity build on Bloom’s taxonomy as revised by Anderson (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001) and are:

-

ILO1: Identify and analyze the US’ geopolitical code in relation to Iraq (2003) in Bush’s political discourses from an essentialist and critical perspective.

-

ILO2: Understanding the differences between essentialist and critical analyses in Geopolitics.

-

ILO3: Evaluate the political consequences of the discourse.

Intended outcomes 1 and 2 are focused on the activity and, overall, the module. However, ILO 3 is ILO of a higher order (id.) —i.e., students are required not only to draw on what they learned in the lecture but to actively use their knowledge to make judgments beyond what they have been exposed to in the classroom. Therefore, ILO1 and ILO2 are mostly designed to assess learning. Contrastingly, ILO3 evaluates whether they are able to reflect on the political weight of specific construction and if they will be able to critically reflect on political discourses and constructions in general —beyond the immediacy of the activity (id.).

Orienting —Orienting students and activating prior knowledge [Up]

The session starts with the activation of students’ prior knowledge so as to situate students within the broad —political and theoretical— debate (Ambrose et al., 2010). I start the session by asking students, “What is the War on Terror? Where was it fought? Why? Who were the US’ friends and enemies?”. The activity is brief because research suggests that “even small instructional interventions can activate students’ relevant prior knowledge to positive effect” (ibid.: 16). I want students to be able to make the connection between what we will study and where these discourses are outside of the classroom; this will help the new knowledge to “stick” better (ibid.: 15) and, even after the activity, it will help students to see where these discourses are.

I chose the WOT as a case study focusing specifically on Bush’s speeches because of its notoriety. I know that, at this stage of their studies, students will have both the declarative and the procedural knowledge (ibid.: 18) both on the theoretical debates —which they have learned about in my module— and on the WOT —because of its notoriety. Both kinds of knowledge are activated through these questions (id.).

Presenting —Presenting information in a clear, engaging way [Up]

Before this specific session, students have already been presented with the theoretical tools of “geopolitical codes”, and they have been assigned readings on geopolitical codes for preparation (chapter 3, Flint, 2017). Now, the presenting part of the session is centered on the WOT. To engage students in the activity, I show them a short video of Bush’s speech launching the intervention in Iraq[1]. I then introduce them to the two main speeches they need to analyze. These are his ultimatum to Saddam Hussein and his speech on Iraq and the Middle East Peace Process[2]. I then recall the five considerations composing a country’s geopolitical code and present the activity.

Activity —What will students be doing? [Up]

Students are asked to form small groups so as to encourage participative dynamics (Mills and Alexander, 2013). At this stage, they are asked to produce groups’ hand-in to submit on Moodle at the end of the session. They are invited, to first identify the US geopolitical code in Bush’s speeches —i.e., to apply an essentialist approach. After this, we proceed with the first round of results sharing. Though there is the risk that this may break the group dynamics, it is important to generate a space of collective formative feedback so that the instructor can correct issues that may have emerged and the whole class can be reassured of the work they are doing. Students are then asked to proceed with the critical analyses. Eventually, another collective sharing of the results is carried out (see annex for the structure of the activity).

Review of learning —How will you check students’ progress and understanding? [Up]

Assessments and reviews are a key part of the process of learning. They do not only give instructors the chance to monitor students’ learning but they also provide students with the opportunities to engage, review, and reflect on their learning (Woods, 2015; Nicol and Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006; Hutchings, 1993). Formative assessment usually takes different forms. On the one hand, there is what Clark names as “assessment for learning”, where instructors gather data to monitor on the competencies acquired by the students (Clark, 2012). On the other hand, there is what Rawlins and Leach call “assessment as learning” where students —and instructors— learn through the process of reflection and assessment of the learning process (Rawlins and Leach, 2014).

As Moon argued, real learning happens through reflection on experiences (Moon, 2005). Therefore, it is key to give the students enough space to monitor their own progress and reflect on their learning and to provide them with some activities that will help them to reflect and that will guide them through their own evaluation of their learning (Woods, 2015; Cleary and Zimmerman, 2004). After the concrete experience of encountering new material, students need to reflect critically on what they learned because it is by drawing conclusions that they will be able to develop the skills acquired for future applications inside and outside the classroom (Moon, 2005; Hutchings, 1993).

Therefore, my session closes with different kinds of reviews of their learning because the ILOs belong to different orders, and they are aimed at training different skills. The first two reviews are assessing mostly ILO 1 and they represent the evaluative assessment —and assessment for learning— phase. The second two activities assess mostly ILO 2 and 3 and they represent the formative assessment —and assessment for learning— phase. Clearly, this is an artificial division because students’ learning and achievement of the ILOs happens throughout the whole process simultaneously (Moon, 2005; Rawlins and Leach, 2014). Overall, the session will be successful if the review activities show that the ILOs have been, at least in part, achieved. To illustrate this, the next sections report students’ results. Methodologically, I have analyzed their hand-ins with Nvivo11 and coded results with similar meaning under the same node —i.e., following the percepts of Discourse Analysis (Dunn and Neumann, 2016) and Content Analysis.

a) Evaluative assessment 1. Students’ classroom work[Up]

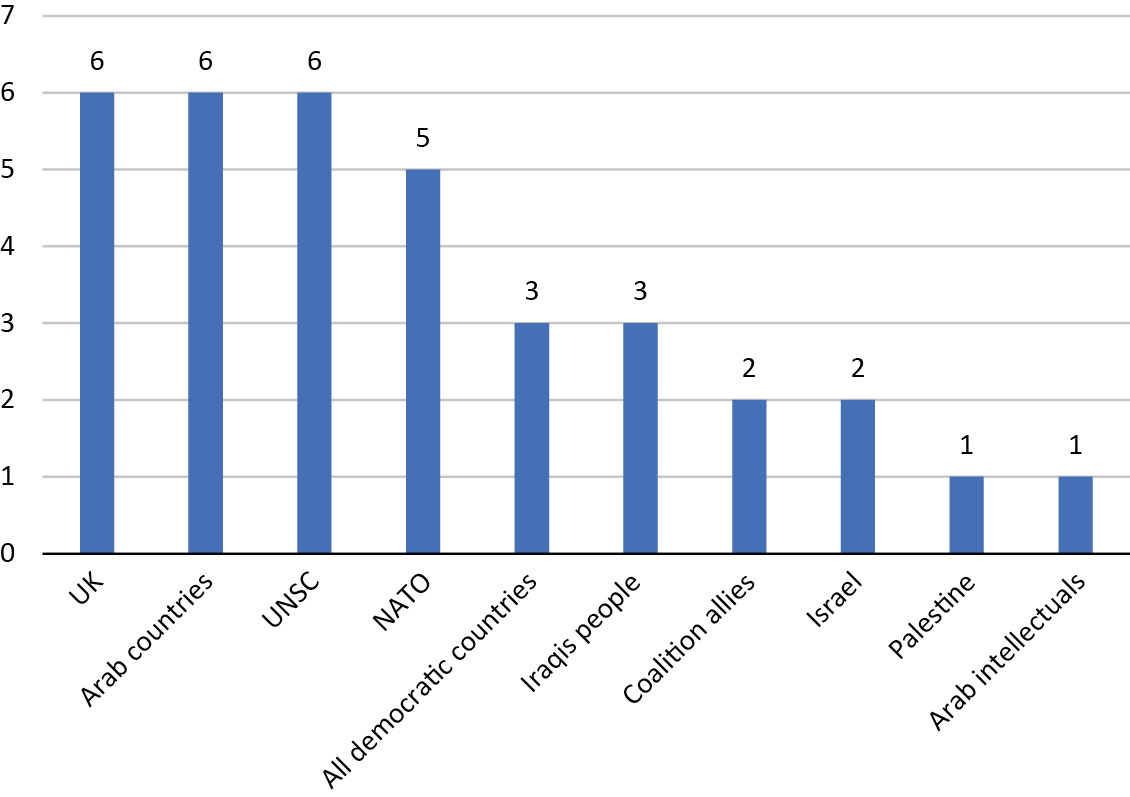

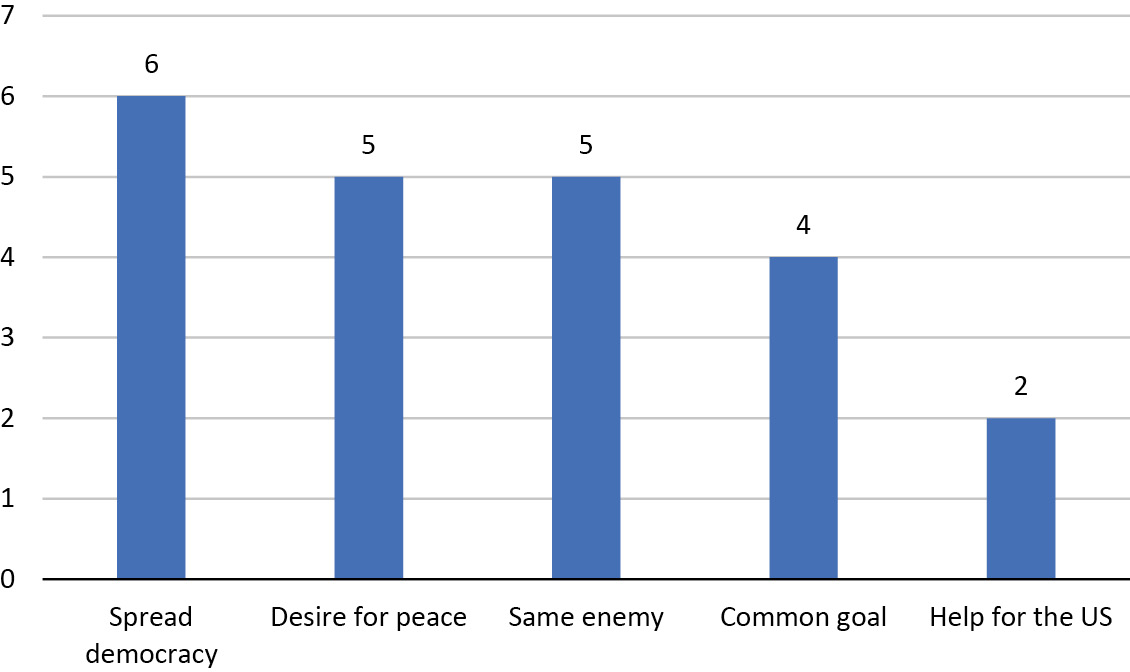

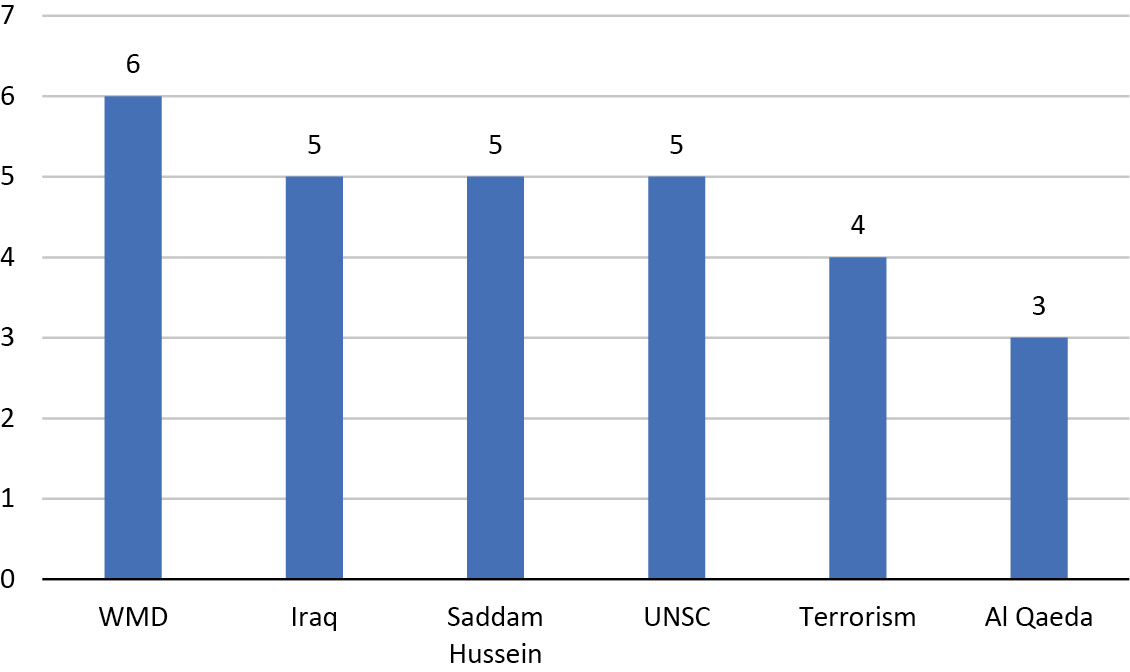

At the end of the activity, students were asked to upload on Moodle their analyses. Here, 28 students worked in groups of 4. Results for the essentialist and critical analyses are reported hereunder (see table 1 and 2 and figures 1, 2, and 3). Their analyses, overall, show that they achieved ILO1 —i.e., they managed to “Identify and analyze the US’ geopolitical code in relation to Iraq (2003) in Bush’s political discourses from an essentialist and critical perspective”. Overall, they show that students were able to identify the 2003 US geopolitical code and, specifically, the designation of the friends and the enemies and the political justification provided in Bush’s speeches both from an essentialist and critical perspective.

Table 1.

Students’ results for the essentialist analysis

| Geopolitical code | Categories identified by the students |

|---|---|

| US’ Friends | “UK”, “NATO”, “the Security Council”, “the West”, “democratic countries around the world”, “Iraqi people that should join the fight against Hussein”, “Arab intellectuals against Hussein” |

| Justifications for friendship | “the desire for peace and freedom allies share”, “the desire to spread democratic values”, “the common goal of eliminating Hussein and authoritarianism”. |

| US’ Enemies | “Iraq”, “Saddam Hussein”; “WMDs”; “international terrorism”, “Al-Qaeda”; “the UN Security Council (if the intervention is vetoed)” |

| Justifications for enmity | “these are threats” [sic.], “these are threats to the US and to the free world”, “they are threats to international peace and security”, “Saddam is a threat to the world” |

| Action plan | “preventive war”, “war as last resort”, “intervention”, “finding allies in the Middle East”, “the freeing of Iraq”, “the avoiding of the emergence of potential enemies by preventing the insurgence of other authoritarian leaders, against the Wester leaders [sic.]”. |

Source: Own elaboration.

Students also managed to conduct a critical analysis, as they not only identified the US friends’ and enemies’ depictions and constructions but also their political consequences, as table 2 illustrates.

Table 2.

Students’ results for the critical analysis

| Construction of the geopolitical code | Categories identified by the students |

|---|---|

| Adjectives and categories used to construct US’ friends | “democratic”, “peaceful”, “free/freedom”, “liberal or liberation”, “civilised world”,

“just, and strongest and stable nations”, “better”, “moral”. “They are described, or more specifically self-described, as saviours and heroes. Risking their lives and their own security for the ‘greater good’”. “The vigilante that aims to fight for the ‘innocent’ and subjugated Iraqi people at the hands of dictator Saddam Hussein”. “They are also represented as saviours of democracy vs authoritarian regimes”. “Friends are represented ‘Democratic (then legitimate) and moral’”. “they have a common desire for peace”, |

| Consequences of the construction of the friends | “The US’s friends are represented as charitable and as members who want to help the

USA promote the democratic values and to ensure peace”. “They are described and represented as stable and free countries who will bring peace and security to the region”. “They are described as states that defend humanity and defend mankind”. “They are strong and capable to do so [intervene militarily]”, “they are described in an absolute way as the best option for Iraq, equalizing democracy and peace to the United States”. “These representations build a message of power”. “These positions express a role for the US of dominance and aggressiveness and put into context it looks like the ‘hero’ is here to save the day from the “bad guy”. “Hence, they [these representation] also acts as a moral shield where the result is justifying the means used. By doing this they are seeing themselves as ‘the good ones’”. “It is a Hero VS Villain rhetoric… where we also have the victims, the Iraqi population and the victims of terrorism Thus, the role of the US and its allies is to protect these victims (and must do whatever is necessary, even war)”. “By using these adjectives, Bush emphasizes the necessary alliance between the US and its friends”. |

| Adjectives and categories used to construct US’ enemies (Saddam Hussein) | “Enemies of liberty and democracy”, “tyrant”, “dying regime”, “brutal dictator”, “lawless man”, “threatening and horrific”, “outlaws”, “violent and destructive”, “dangerous”, “aggressive”, “terrorist”, “authoritarian and immoral”, “barbarism, civilized vs uncivilized”, “irrational actor that doesn’t know what he’s doing”, “peaceful measures have not worked and that is why they are irrational and negotiation is not the best way to deal with them. They are so barbaric they attack their own population [Hussein and his forces]”, “Hussein represents the triumph of hatred and violence” and “[he] intimidates the civilized world”. |

| Consequences of the construction of the enemies | “The consequences of representing enemies as such is that for example that they segregate

making a distinction between ‘them’ and ‘us’ by consequence, as the enemy portrays

all the negative features possible it justifies the intervention” [sic.]. “Through identifying themselves as guardians of democratic stability and balance, they accomplish their purpose of their enemies being perceived as enemies of mankind globally”. “Hero VS Villain rhetoric: Hussein is viewed as the villain and thus its actions are completely delegitimized”. |

| Justification of the “action plan” | “It [this representation] pushes for military intervention”. “They (the US) frame the intervention on the means of democracy, freedom and peace which is derived from the dichotomy of good and evil previously constructed hence, they justify their intervention by framing Iraq as the evil threat to the world and also to its own civil society”. “They (the US) frame Hussein as a threat, and not the population, and thus the invasion is legitimized because the mission is to protect the citizens from Hussein”. “(it) creates a division between ‘the morals’ (the US), which justifies every type of behavior from it, and ‘the immorals’, the uncivilized or the evil”, where these last ones need to be intervened in order to restore peace in the territory (not only in Iraq specifically but also all the other countries ‘Iraq has corrupted’) [sic.]”. “The only alternative is the use of force for the greater good”. |

Source: Own elaboration.

b) Evaluative assessment 2. Multiple-choice questionnaire[Up]

Evaluative assessment 2 and 3 were conducted autonomously, outside of the classroom in the two weeks following the activity. Assessing the knowledge acquired on critical understandings of Geopolitics and IR through a Multiple-choice questions (MCQ) survey is not easy. While MCQs are helpful in assessing “objective” knowledge on a matter, critical approaches aim to unpack “objectivity”. Nonetheless, I decided to start this part of the evaluation with a MCQs part because starting the evaluative assessment with a more structured activity gave students the sense of a “real” assessment (Rawlins and Leach 2014; Angelo and Cross 1993). I included questions that would help me observe if students were paying attention to the survey —or to the activity in class— and more general questions on the approaches and their application in Geopolitics. 28 students participated and grades oscillated between 7 and 10 (out of 10), with a class average of 9,50 —thus returning a good result for this part of the activity. The questions can be found in next table:

Table 3.

MCQ questions and students’ results

| Questions | Answer | ILOs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Questions on the class activity | % of correct answers | ||

| The US intervention in Iraq took place in: A) 2001 B) 2008 C) 2003 |

2003 | ILO1 | 100% |

| Who are the US’ enemies in the intervention in Iraq in 2003 that Bush identifies in

his speeches? A) Iraq and international terrorism B) Afghanistan and Iran C) The Soviet Union and Cuba |

Iraq and international terrorism | ILO1 | 100% |

| Questions on the identification of the geopolitical codes | % | ||

| Who are the US’ friends in the intervention in Iraq in 2003 that Bush identifies in

his speeches? A) Allies in the military coalition B) Other capitalist states C) The UK and France |

Allies in the military coalition | ILO1 (essentialist analysis) | 100% |

| For Bush, Iraq is a threat because: A) It collaborates closely with Iran, the big US enemy in the MENA B) It collaborates with international terrorism, and it has WMDs C) It has a long history of collaboration with Saudi Arabia |

It collaborates with international terrorism, and it has WMDs | ILO1 (essentialist analysis) | 96% |

| Bush is legitimizing the intervention in Iraq using: A) Metaphors of civilization and democratization B) The reasoning that Iraq is blocking oil exportation C) The fact that, otherwise, Iraq will follow Iran and try to develop nuclear weapons |

Metaphors of civilization and democratization | ILO1 (critical analysis), ILO2, ILO3 | 81% |

| Questions on the understanding of the different approaches to geopolitical codes | % | ||

| For critical scholars, it is important to study geopolitical codes: A) To see how they legitimize political action and (re)produce geographical understandings of international politics B) To understand how states fabricate lies about international politics C) So that states can formulate their foreign policies decisions |

To see how they legitimize political action and (re)produce geographical understandings of international politics | ILO2 | 85% |

| For critical scholars, geopolitical codes: A) Reflect a country’s national interests B) Are social constructions that are shaped by more elements than just rational thinking C) Should not be an object of study because they reflect and reify a state’s interests in international politics |

Are social constructions that are shaped by more elements than just states’ rational thinking | ILO2 | 96% |

| Essentialists argue that geopolitical codes: A) Are a knowledge that is created and used in statesmen’s and intellectuals’ geopolitical reasonings to B) Do not exist, are not an object of study in mainstream geopolitics C) Represent the straightforward designation of a state’s international behavior, the identification of friends and enemies in international politics that each state needs to do |

Represent the straightforward designation of a state’s international behavior, the identification of friends and enemies in international politics that each state needs to do | ILO2 | 100% |

Source: Own elaboration.

c) Formative assessment 1. Students’ formative reflections on the analysis[Up]

Formative assessment 1 is aimed at providing students with enough space to reflect on their learning process (Woods, 2015; Cleary and Zimmerman, 2004). Reflecting allows the knowledge acquired on the different approaches in geopolitics to settle in (ILO2), but also to achieve the higher order level of evaluating the political consequences of the discourse (ILO3). So, to conduct the first part of the formative assessment, I designed various questions to guide students through their personal reflection. At the very end, I added two extra questions on the Middle East representation to assess whether they were also able to tie together different topics we had dealt with through the module and think critically about geopolitics (Module aim). Students had approx. 2 weeks to hand in their reflections; 22 students participated.

Table 4.

Reflection questions

| Questions | ILOs |

|---|---|

| Questions for the reflection on the consequences of the constructions | |

| 1. In the speeches analyzed, how are the US’ enemies represented? What do you think are the political consequences of these representations? | ILO1 & ILO2 |

| Questions to assess the understanding of the different approaches | |

| 2. What is the difference between essentialist and critical analyses? How do you think they differ in their understandings of geopolitical codes? | ILO2 |

| 3. What does it mean that friends and enemies are social constructions? Do these representations of friends and enemies play a political role? And why and how do you think they do/don’t? | ILO2 & ILO3 |

| Questions on the application of previous knowledge acquired to the deconstruction of the geopolitical codes analyzed | |

| 4. How does the way Bush talks about the Middle East recall the construction studied in class? And how does this construction matter politically, in your opinion? | ILO3 Module aim |

| 5. Can you think of any way Bush’s construction of Iraq recalls the construction of the MENA studied in class? | ILO3 Module aim |

Source: Own elaboration.

Overall, students’ answers confirmed that the ILOs were mostly achieved, as next table illustrates schematically.

Table 5.

Students’ answers

| Questions | Students’ answers |

|---|---|

| Questions for the reflection on the consequences of the constructions | |

| 1. In the speeches analyzed, how are the US’ enemies represented? What do you think are the political consequences of these representations? | “They [the US] are seen as heroes because of their peaceful goals”. “This rhetoric provokes a gather around the flag effect whereby the US as well as their allies need work together to defeat the “common enemy”. “…with the deployment of this rhetoric, you are setting the stage for a war/battle between two forces: the US and its allies against the enemies”. “The main political consequence is the justification of the war on terror”. “Pre-emptive action against Iraq because Iraq is an irredeemably bad actor that leaves no room for negotiations”. “The consequence therefore is that the only way in which the west can act is by violent ways, as Iraq leaves them no alternatives”. “The use of polysyndeton and juxtapositions in Bush’s strategic rhetoric and the zoomorphism used implies that they are no longer considered humans, their moral character is discredited [sic.]”. |

| Instructor’s assessment: Overall, ILO 2 was achieved. Students were able to reflect on the political consequences sought with Bush’s speech and the depictions of the enemies. |

|

| Questions to assess the understanding of the different approaches | |

| 2. What is the difference between essentialist and critical analyses? How do you think they differ in their understandings of geopolitical codes? | “Essentialists focus on the state as the main rational actor while the critical view

focuses on the examination of —implicit and explicit —meanings, given to specific

places to justify states’ actions in relation to foreign policies actions”. “[…] On the other hand, the critical analyses stablish that the geopolitical imaginations are representations of the world that provide legitimization for the political actions, and these are not objective but created based on the interest. The geopolitical codes are considered to be the basis of the political action, which are also constructed, created by the states and experts based on their interest and objectives. These codes permit to see the power-relations” [sic.]. “Critical geopolitics deconstruct codes and analyse the implicit and explicit meaning of specific actions. Geopolitical codes are not pre-given but a process of social construction”. “The representation of the world and politics from the mainstream analysis is far from objective and are limited depictions of world history and geography used to support policy prescriptions for states”. “Geopolitical codes frame the relations between powers according to subjective assumptions and stereotypical hypotheses”. “In the example of Iraq, an essentialist would say that Iraq poses an imminent threat because of the ideological differences, the use of terrorism and weapons of mass destruction and that as a consequence, Iraq must be invaded (in the same way they have historically countered every authoritarian regime). However, from a critical perspective, the US uses a rhetoric of us VS them/hero VS villain in order to justify their invasion of Iraq. They would say the particular narrative they have created around Iraq is what legitimizes their invasion”. |

| Instructor’s assessment: Overall, most students achieved ILO 2. Their reflections show they have understood the differences between the two approaches and can also explain the different understandings of reality behind the two approaches. |

|

| 3. What does it mean that friends and enemies are social constructions? Do these representations of friends and enemies play a political role? And why and how do you think they do/don’t? | “The terms are social constructions because due to certain characteristics of the

potential enemies or friends, alongside the nature and characteristics of ourselves

we determine who is a friend and who is not”. “These representations do play a very important political role as we as actors behave towards other actors in the bases [sic.] on what they mean for us, aka the way in which we portray different actors, as friends or enemies shapes the policies we implement towards them”. “Of course, the representation plays a political role, firstly because it is not the same to be an ally than an enemy and the role of the country differs based on the construction that the other country has deployed into it. For example, the role of China in American politics has changed since Trump declared China as an enemy. Tariffs on exports have been increasing in the latter years so as to put obstacles in the Chinese American trade. [sic.]”. “In other words, it does not follow objective or rational criteria, as explained that Iraq (enemy) and Saudi Arabia (friend) fulfil the same non-democratic characteristics, but one is a friend and the other one is not”. “It means that the organization of space and alliances is not neutral or objective. Instead, it is built by the knowledge that is created and used in reasonings. They try to explain that enemies and friends are not geographically determined but that power relations are complex and need to be explained from several points of view such as security, geography, politics…”. “These representations sure do play a political role since they have a direct relationship with power relationships between states and their political actions. By seeing friends and enemies as social constructions speeches are no longer descriptions of a geopolitical reality but a revelation of intentions, interests and alliances. Also, these constructions are frequently used to justify political actions or plans so they are intrinsically political”. |

| Instructor’s assessment This question starts guiding students towards ILO3. Answers show that students managed to understand the political importance of geopolitical codes as social constructions. Some students expanded their reflection and used examples not directly linked with the activity —thus revealing that they have acquired knowledge that they are able to use outside the module (ILO3 & module aim). However, only some students referred to power-relations rather than the sole “exercise of power” —thus showing how difficult it is for students to grasp power relations that shape politics such as Orientalist constructions. |

|

| Questions on the application of previous knowledge acquired to the deconstruction of the geopolitical codes analyzed | |

| 4. How does the way Bush talks about the Middle East recall the construction studied in class? And how does this construction matter politically, in your opinion? | “He talks about the MENA as a homogenous region, arguing that prosperity and democracy

could be established all around the region, ignoring the huge differences that exist”, “Bush mentions the chaos and the permanence of authoritarian regimes that exploit their populations. This coincides with the construction we studied in class about the ME: a region with a lack of leadership, lack of stability, and lack of organization”. “The way that bush talks about the MENA recalls the construction studied in class as many times he identifies Islam and terrorism as a homogeneous characteristic of the region. […] It is a big error from Bush’s narrative to homogenize the region”. “The construction that Bush offers have shaped the perception of the many about the Middle East and have influenced the material practices and political decisions that have been made. The negative and particular context of the Middle East has been a social construction due to the narratives that are normally in the news, social media and press. We have based our perception of this region in a context surrounded by terrorism, instability, violence, oppression and anti-Americanism”. “This construction matters politically because, if we just focus on the prevailing perception of a region, we get a misleading impression. This image will influence the way we make foreign policy. We have a negative view of the MENA just like Bush. We regard it as a region of instability and anti-western ideals. Enemies of our values become state enemies”. “In fact, the War on Terror narrative used by Bush administration can be recognized as one of the main sources for the social construction of MENA as intolerable towards liberal values, a threat to international security and highly repressive”. “By depicting it as a region of turmoil, crisis and anti-Americanism, Bush justified the political decision of launching the War on Terror. Hence, this proves that oversimplified representations and perceptions, in this case of the MENA region, can influence material practices and political decisions”. |

| Instructor’s assessment ILO3 & Module aim seemed to be achieved. Students were able to apply knowledge they acquired in other sessions to Bush’s geopolitical code. Some students reflect on the Orientalist rhetoric used by Bush and, some of them, even define the WOT as a “process of construction of the region” aimed at legitimizing military action —thus showing a broader comprehension of the module’s content and ability to apply it. |

|

| 5. Can you think of any way Bush’s construction of Iraq recalls the construction of the MENA studied in class? | “This question is linked to the question before as the Bush’s construction of Iraq

is homogenized, everyone from Iraq is a terrorist, they all belong to Islam, they

all speak Arabic, there is a lack of democracy”. “Bush construction of Iraq as a terrorist state corresponds to the generalized idea of construction of the MENA that we saw in class. Bush emphasizes how Iraq is an evil state that embraces terrorism and the end of the freedom in our countries, which continues with the erroneous idea of the MENA”. “Iraq is constructed as a troubled state, an enemy of the US with no regard of conventions or war and morality, an outlaw regime. Bush’s perception of Iraq is such because we have lumped the MENA under the same general label. When talking about Iraq and other states in the Middle East, negative connotations arise that are associated with Islamic fundamentalism, terrorism and crisis, a place where anti-Americanism reigns”. “Bush’s construction of the space recalls in many ways what we studied in class. As stated above, his construction holds negative and particularistic contexts that tend to stereotype the region. His tendency to portray them as terrorist and a violent threat recalls the relatively new idea of a region linked to fundamentalism that has been protagonist of many events like the hostage crisis or the oil crisis. Bush depicts the MENA as destructive and violent which perpetuates the common image of the region being a place of turmoil, crisis and anti-Americanism”. |

| Instructor’s assessment Students managed to point out how the discursive construction resounds with geopolitical construction of the region —therefore, for many of them, ILO3 and the module aim seem to be achieved as they have been able to apply their knowledge in broader context —i.e., not the one strictly guided by the activity. |

|

Source: Own elaboration.

d) Formative assessment 2. Debriefing and collective reflections on the activity[Up]

An effective reflection does not only involve students reflecting on what they did and what they learned but also thinking about why they did it and what it allowed them to understand (Bonwell and Eison, 1991). This was the aim of the second formative assessment: to engage students in a collective reflection on what the activity allowed them to see. The debriefing started with a discussion of the main results, so to work as an evaluative assessment, too. Then, the rest of the debriefing was articulated around different questions. First, I asked them how they found the activity. Here, students stated that “It was helpful to understand the political situation in 2003”, that they “liked it and it was interesting”, or that “it was fine, it was useful. We have been studying political communication in the past, but this was different, it was a different kind of reflection”. One particular student remarked:

It took us a while to figure out what we were doing. I think that […] once you have an activity going you need to push that threshold of laziness or “ufff, I don’t want to answer or whatever”. At first when you said that we had an activity we were like “uff” but then when you get into it you really start going and making sense of the analysis and enjoying the process. This is also why I think there is more (better) answers in our hand ins and then reflections than when you asked in class.

Then I asked students about the different activities they were asked to do. Here they emphasized that the reflection questions allowed them to grasp the broader meaning of the activity. Asked about how they found the 3 different tasks, they answered that: “The quiz was ok, but the other part was more interesting because you make us focus on reflect and think so I probably preferred the other (the reflection part)”.

Another student added that: “For me it was very clear (the activity) after I analyzed everything and finished the reflection too”.

Lastly, when asked about what they felt they had learned from the activity, they said that they thought “the activity helped with fully understanding the topic. It’s a practical example” and that “The activity gives you practition [sic.]. We study the theory but this exercise puts in practices what we study in class”. They also said that “It was useful to review some main concepts” and that “It shows what the difference between essentialists and critical geopolitics is”. Referring specifically to the critical perspective, one student added “here (in other modules on IR) this perspective is a bit lost so I think it is useful to talk about these perspectives that we don’t usually see”.

Overall, 28 students were present for the debriefing. However, only some of them shared their feelings about the activity. Furthermore, their comments in the debriefing would not support the idea that students managed to achieve ILO2 and ILO3, as they did not seem to show a broad awareness of what the activity allowed them to learn. However, their personal reflections point to a full achievement of ILO2 and ILO3 —and mostly of the module aim. When asked about this gap in the debriefing, a student said that, in the classroom, it is more difficult for them to share their views, because there is always a “barrier of shyness” —thus, revealing the usefulness of conducting both kind of reflections— i.e., the written answers and oral debriefing.

CONCLUSION[Up]

Having reached this point, it is useful to recall the activity ILOs:

-

ILO1: Identify and analyze the US’ geopolitical code in relation to Iraq (2003) in Bush’s political discourses from an essentialist and critical perspective.

-

ILO2: Understanding the differences between essentialist and critical analyses in Geopolitics.

-

ILO3: Evaluate the political consequences of the discourse.

Overall, students’ results illustrated above show they were able to produce both an essentialist and a critical analysis of the 2003 US geopolitical code —thus, achieving ILO1. Moreover, most of them were able to explain the differences between the two approaches in their own words, thus showing that they achieved ILO2. ILO3 was the most challenging aim for students to achieve —as it required them an abstraction and analytical effort to understand the political consequences of the discourse. Even so, the majority of the students were able to pinpoint the power relations and the instrumentalization of the discourse, revealing that they achieved a certain level of understanding of how to conduct a critical analysis. Furthermore, the last reflections linked to ILO3 and the own students’ reflections on the activity show that the exercise helped students to achieve the three ILOs and, overall, to broaden and deepen their understandings of geopolitics.

Students’ comments on how the Middle East was discursively constructed and this construction used to legitimize military operations reveal that they were able to link the knowledge acquired throughout the module and apply it in this specific case. Furthermore, they were able to explain this kind of exercise of power and its consequences in their own words, in some cases, even drawing comparisons with other countries. Therefore, it seems that the various tasks included in the activity allowed them to think of geopolitics in a broader way and outside the classroom —as they drew from their own knowledge of politics. This was also confirmed by the students in the final debriefing where some of them highlighted the added value they found in the activity and, overall, in the tasks where they had more space to explain political processes in their own words —thus confirming students’ acquisition of knowledge and their ability in applying it outside of the instructor’s supervision.

Therefore, I consider that the activity was successful and that it could be helpful for instructors of Geopolitics but also, more broadly, IR. Overall, critical and postpositivist approaches to politics are always challenging for students to grasp. Therefore, the activity —and active learning in general— could be a useful tool to bring students to grasp the “intangibility” of political discourses.

All in all, there are ways students could have been pushed further in their encounter with power relations in these constructions. Overall, there are other relations of power —e.g., gender, race, religion, and class— that remain untouched by the activity and the module in general. There are, however, some restraints on an instructor’s choices —disciplinary frameworks, threshold concepts, institutional and policy frameworks, shared modules and shared syllabi. Therefore, instructors may not have the desired context within their classroom and, in this case, the activity had to fit within some of these frames.

I hope, however, that it will serve as an example for some instructors dealing with similar approaches to security, the war on terror, and/or the Middle East region and, more broadly, in the study of critical approaches in International Relations, Geopolitics, and similar fields. Furthermore, it should be taken into account that active learning may imply some logistics and preparatory challenges both for the instructor and for students. However, research has shown that it can be very beneficial for students’ learning (McCarthy and Anderson, 2000) and that it can be particularly useful to challenge hegemonic paradigms and practices in International Relations (Lamy, 2007). The results obtained through the activity presented and students’ own assessment of the activity seem to confirm that active learning can be very beneficial for students’ learning and, overall, the development of critical thinking.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS[Up]

The author is extremely grateful to the special issue editors, Marina Diaz and Lucía Ferreiro, for all their help and guidance. She is also grateful to the Journal editor Agustí Bosch, Elena García Guitián for their kind and helpful editorial style and Angustias Hombrado. I would also like to thank the generous feedback received by the other authors joining the special section and the reviewers for their time and for helping me develop this project. Also, I would like to express my gratitude to Pablo Biderbost for his support for this activity, to the Universidad Pontificia Comillas and, above all, to all the students of my course on Geopolitics (2020-2021) who willingly participated in the activity and gave me feedback to reflect on their learning process. Lastly, I would like to thank my Queen Mary, University of London for giving me the opportunity to take the Certificate in Learning and Teaching (CILT) and my peers and instructors on the course. Part of this project has received funding under the Juan de la Cierva-Formación scheme (FJC2020-046251-I/MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100 011033 and “NextGenerationEU”/PRTR).

NOTES[Up]

| [1] |

Bush, George W. 2003. “President Bush announces military operation in Iraq”. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2zT-ZHBbOzM [retrieved: October 10, 2020]. |

| [2] |

Bush, George W. 2003. “President George W. Bush’s Speech on Iraq and the Middle East ‘Peace Process’”, Global Policy Forum, Available at: https://www.globalpolicy.org/component/content/article/167-attack/35431-president-george-w-bushs-speech-on-iraq.html [retrieved October 27 2020]. Bush, George W. (2003), “President George W. Bush’s ultimatum to Saddam Hussein”, The Guardian, Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/mar/18/usa.iraq [retrieved October 27 2020]. |

References[Up]

|

Agnew, John. 1998. Geopolitics. Re-Visioning World Politics. London: Routledge. |

|

|

Ambrose, Susan A., Michael W. Bridges, Michele DiPietro, Marsha C. Lovett and Marie K. Norman. 2010. How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. |

|

|

Anderson, Lorin W. and David R. Krathwohl (eds.). 2001. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman. |

|

|

Angelo, Thomas A. and K. Patricia Cross. 1993. Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. |

|

|

Bilgin, Pinar. 2004. “Whose Middle East’? Geopolitical Inventions and Practices of Security”, International Relations, 18 (1): 25-41. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117804041739. |

|

|

Bonwell, Charles and James A. Eison. 1991. Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 1. Washington DC: The George Washington University, School of Education and Human Development. |

|

|

Cairo Carou, Heriberto. 2016. “Critical Geopolitics and the Decolonization of Area Studies”, in Encarnación Gutiérrez Rodriguez, Manuela Boatcă and Sérgio Costa (eds.), Decolonizing European Sociology: Transdisciplinary Approaches. London; New York: Routledge. |

|

|

Campbell, David. 1998. Writing Security: United States Foreign Policy and the Politics of Identity. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. |

|

|

Clark, Ian. 2012. “Formative Assessment: Assessment Is for Self-Regulated Learning”, Educational Psychology Review, 24 (2): 205-249. Available at: https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10648-011-9191-6. |

|

|

Cleary, Timothy J. and Barry J. Zimmerman. 2004. “Self-Regulation Empowerment Program: A School-Based Program to Enhance Self-Regulated and Self-Motivated Cycles of Student Learning”, Psychology in the Schools, 41 (5): 537-550. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10177. |

|

|

Culcasi, Karen. 2010. “Constructing and Naturalizing the Middle East”, Geographical Review, 100 (4): 583-597. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2010. 00059.x. |

|

|

Deardoff, Michelle D. 2013. “The Professor, Pluralism and Pedagogy”, Journal of Political Science Education, 9 (3): 366-373. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2013.796252. |

|

|

Devlin, Marcia. 2006. “Challenging Accepted Wisdom about the Place of Conceptions of Teaching in University Teaching Improvement”, International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 18 (2): 112-119. |

|

|

Díaz Sanz, Marina. 2019. Iran and the Geopolitical Imagination: A Discourse Analysis of the Spanish Contribution to the Debate on the Meaning of Modern Iran [doctoral dissertation]. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid. Available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=223843. |

|

|

Díaz Sanz, Marina and Lucía Ferreiro Prado. 2021. “Orientalism is not my opinion: Decolonial Teaching and the problem of credibility in IR courses with a MENA focus”, Politics, online first. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/02633957211009068. |

|

|

Dodds, Klaus. 2019. Geopolitics: A Very Short Introduction. 3rd ed. Very Short Introductions, 171. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780198830764.001.0001. |

|

|

Dunn, Kevin C. and Iver B. Neumann. 2016. Undertaking Discourse Analysis for Social Research. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. |

|

|

Flint, Colin. 2017. Introduction to Geopolitics. 3rd ed. London; New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group. |

|

|

Flint, Colin and Peter J. Taylor. 2018. Political Geography: World-Economy, Nation-State and Locality. Seventh edition. London; New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315164380. |

|

|

Giroux, Henry A. 2012. “Rethinking Education as the Practice of Freedom: Paulo Freire and the Promise of Critical Pedagogy”, Policy Futures in Education, 8 (6): 715-721. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2010.8.6.715. |

|

|

Giroux, Henry A. 2020. On Critical Pedagogy. 2nd ed. London; New York; Oxford; New Delhi; Sydney: Bloomsbury Academic. |

|

|

Hutchings, Pat. 1993. “Principles of Good Practice for Assessing Student Learning”, Assessment Update, 5 (1): 6-7. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/au.3650050104. |

|

|

Ishiyama, John T., William J. Miller and Eszter Simon (eds.). 2015. Handbook on Teaching and Learning in Political Science and International Relations. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. |

|

|

Jackson, Richard. 2005. Writing the War on Terrorism. Language, Politics and Counter-Terrorism. Manchester: Manchester University Press. |

|

|

Khan, Alya and John Gabriel. 2018. “Resisting the Binary Divide in Higher Education: The Role of Critical Pedagogy”, Journal for Critical Education Policy, 16 (1): 30-58. |

|

|

Lamy, Steven L. 2007. “Challenging Hegemonic Paradigms and Practices: Critical Thinking and Active Learning Strategies for International Relations”, PS: Political Science and Politics, 40 (1): 112-116. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096507250279. |

|

|

Li, Darryl. 2020. “Teaching the Global War on Terror”, in Omnia El Shakry (ed.), Understanding and Teaching the Modern Middle East. Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv17nmzqj. |

|

|

McCarthy, Patrick J. and Liam Anderson. 2000. “Active Learning Techniques versus Traditional Teaching Styles: Two Experiments from History and Political Science”, Innovative Higher Education, 24 (4): 279-294. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1023/B:IHIE.0000047415.48495.05. |

|

|

Mills, David and Patrick Alexander. 2013. Small Group Teaching: A Toolkit for Learning. The Higher Education Academy. Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/resources/Small_group_teaching_1.pdf [retrieved: October 27, 2021] |

|

|

Moon, Jenny. 2005. Guide for Busy Academics No. 4: Learning Through Reflection. Higher Education Academy. Available at: https://nursing-midwifery.tcd.ie/assets/director-staff-edu-dev/pdf/Guide-for-Busy-Academics-No1-4-HEA.pdf [retrieved: October 27, 2021]. |

|

|

Nicol, David J. and Debra Macfarlane‐Dick. 2006. “Formative Assessment and Self‐regulated Learning: A Model and Seven Principles of Good Feedback Practice”, Studies in Higher Education, 31 (2): 199-218. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/ 03075070600572090. |

|

|

Ó Tuathail, Gearóid. 1996. Critical Geopolitics: The Politics of Writing Global Space. London: Routledge. |

|

|

Ó Tuathail, Gearóid. 1998a. “Introduction: Thinking Critically about Geopolitics”, in Gearóid Ó Tuathail, Simon Dalby and Paul (eds.), The Geopolitics Reader. London: Routledge. |

|

|

Ó Tuathail, Gearóid. 1998b. “Postmodern Geopolitics? The Modern Geopolitical Imagination and Beyond”, in Gearóid Ó Tuathail and Simon Dalby (eds.), Rethinking Geopolitics. London: Routledge. |

|

|

Petty, Geoff. 2022. “Orient, Present, Activity, Review”, Improve Your Teaching and That of Your Team [blog]. Available at: https://geoffpetty.com/ [retrieved: October 27, 2021]. |

|

|

Rawlins, Peter and Linda Leach. 2014. “Questions in Assessment for Learning and Teaching”, in Alison Margaret St. George, Seth Brown and John O”Neill (eds.), Facing the Big Questions in Teaching: Purpose, Power and Learning, 2nd ed. Auckland: Cengage Learning. |

|

|

Said, Edward W. 1978. Orientalism. Western Conceptions of the Orient. London: Routledge and Kegan Pail Ltd. |

|

|

Woods, Nathan. 2015. “Formative Assessment and Self-Regulated Learning”, Education, 2015. Available at: https://thejournalofeducation.wordpress.com/2015/05/20/formative-assessment-and-self-regulated-learning/ [retrieved: October 27, 2021]. |

ANNEX[Up]

Topic: Geopolitical codes

ILO1: Identify and analyze the mainstream discursive formulation of the US geopolitical code in relation to Iraq (2003) in Bush”s political discourses.

ILO2: Understanding the differences between essentialist and critical analyses in Geopolitics.

ILO3: Evaluate the political consequences of the discourse.

| Sequence | Timing | Activity | Tools/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-class | Async | Read | Flint, C, 2018, Introduction to Geopolitics. London: Routledge. (chapter 3, Geopolitical Codes, uploaded on Moodle) |

| Class | 00-05 | Welcome | Slide 1 Presentation of the session (geopolitical codes of the US in 2003 war in Iraq) |

| 05-10 | Prior knowledge activity | Questions on conceptualization of geopolitical codes and geopolitical approaches | |

| Class | 10-12 | Definition | Debate on students’ answers and main conceptualizations of geopolitical codes (mainstream and critical approach) |

| 13-20 | Presentation of the activity | Brief video (5 minutes) of Bush’s speech launching the intervention in Iraq Presentation of the activity: Studying the US’ geopolitical code for the intervention in Iraq (2003) |

|

| 20-30 | Reading of Bush’s speeches | Students reading Bush’s speeches (Instructor, allocating groups on Moodle and BlackBoard Collaborate) |

|

| 30-70 | Small groups’ work | Students producing the mainstream analysis of geopolitical codes (Instructor, working with students) |

|

| 70-75 | Report back (10 min) |

Report back from groups’ analysis instructor checking on analyses produced and giving feedback |

|

| 75-90 | Break | ||

| 90-130 | Small groups’ work | Students producing the critical analysis of geopolitical codes (Instructor, working with students) |

|

| 130-140 | Report back | Report back from groups’ analysis Tutor checking on analyses produced and giving feedback |

|

| 140-150 | Wrap-Up | Instructor’s conclusions based on the analyses Final students” questions |

|

| Post-class | Async + sync |

Moodle | Evaluative assessment: quiz/Multiple choice questions Formative assessment: written reflections & debriefing in class (sync) |

Biography[Up]

| [a] |

Lecturer in International Relations at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain. Her work focuses mostly on global discourses and practices of terrorism and counter-terrorism and international security more in general. She has been a board member of the EISA Early Career Development Group and the BISA Critical Studies on Terrorism Working Group. She is the author of various articles focusing on international terrorism and counter-terrorism and of the research monograph The UN and counter-terrorism. Global hegemonies, Power and identities (Routledge, 2021). She is also a co-editor of various edited volumes, among others, Encountering Extremism. Theoretical Issues and Global Challenges (MUP, 2020). She has been teaching IR at a BA and MA level for several years and she holds a Certificate in Learning and Teaching awarded by the Queen Mary, University of London. |