Transparency in nursing home services before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain

Transparencia en los servicios de residencias de mayores antes y durante la pandemia de la COVID-19 en España

ABSTRACT

The objective of the article is to analyze transparency in the provision of nursing home services towards beneficiaries. To do this, we identify three policy dimensions and their specific elements, what allow us to assess transparency in the implementation of these services. The article develops and empirically tests an analytical framework to assess the transparency of elderly care services in Spain. On the one hand, we examine the extent to which nursing home service providers (both public and private) are obliged to supply information about their performance. We analyze the formal obligations for both public and private facilities in the seventeen autonomous communities (ACs). On the other hand, we examine the content of the messages posted on Twitter by the three biggest business associations of the sector in Spain, namely, Business Federation of Assistance for Dependents (Federación Empresarial de la Dependencia), Association of Dependency Services Companies (Asociación de Empresas de Servicios para la Dependencia), and Business Circle of Caring for People (Círculo Empresarial de Atención a las Personas), in order to determine whether transparency is a concern for the industry regardless of the regulatory requirements faced by direct service providers.

Keywords: transparency, nursing home services, COVID-19, formal rules, topic modeling, dictionary analysis.

RESUMEN

El objetivo de este artículo es analizar la transparencia en los servicios de residencias de personas mayores hacia sus beneficiarios. Para ello identificamos tres dimensiones de la política y sus elementos específicos que nos permiten evaluar la transparencia en la implementación de estos servicios. El artículo desarrolla y somete a verificación empírica el marco analítico para evaluar la transparencia de los servicios de atención a personas mayores en España. Por un lado, examinamos en qué grado las residencias (tanto públicas como privadas) están obligadas a proporcionar información sobre su desempeño. Para ello este artículo analiza las obligaciones formales a las que están sujetas las residencias tanto públicas como privadas en las diecisiete comunidades autónomas (CC. AA.). Por otro lado, analizamos el contenido de los mensajes publicados a través de Twitter por las tres asociaciones de empresas más grandes del sector en España: la Federación Empresarial de la Dependencia, la Asociación de Empresas de Servicios para la Dependencia y el Círculo Empresarial de Atención a las Personas. El objetivo de este análisis es determinar si la transparencia es una prioridad para estas organizaciones en la prestación de los servicios, independientemente de las obligaciones legales a las que están sujetos los proveedores directos de estos servicios.

Palabras clave: transparencia, residencias de mayores, COVID-19, reglas formales, topic modeling, dictionary analysis.

CONTENTS

- ABSTRACT

- RESUMEN

- INTRODUCTION

- TRANSPARENCY: EXAMINING PROVISION OF INFORMATION FROM SERVICE PROVIDERS TO BENEFICIARIES

- TRANSPARENCY IN NURSING HOME SERVICES: POLICY DIMENSIONS AND ELEMENTS OF THE TRANSPARENCY OF THE SERVICES

- NURSING HOME SERVICES IN SPAIN AND THE EFFECT OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

- METHODOLOGY

- FORMAL TRANSPARENCY ACROSS THE SPANISH AUTONOMOUS COMMUNITIES

- TOPIC MODELING AND DICTIONARY ANALYSIS OF BUSINESS ASSOCIATIONS CONCERNS BEFORE AND AFTER COVID-19 RESTRICTIONS

- CONCLUSIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- References

- APPENDIX 1. LEGAL FRAMEWORK EXAMINED

- APPENDIX 2. QUANTITATIVE TEXT ANALYSIS

INTRODUCTION [Up]

According to official data from the Spanish Institute for the Elderly and Social Services (IMSERSO), as of January 2021, 47.5 % of the fatal COVID-19 cases reported in Spain occurred amongst nursing home residents (a total of 31,460 people). The COVID-19 crisis reflected and expanded the ineffective management of this service and brought devastating consequences for its beneficiaries. Against this backdrop, the design and implementation of nursing home policy must be substantially reformed. A core aspect of these reforms should deal with transparency and responsiveness of the services towards beneficiaries. In the assessment of these services, it is necessary to examine the performance of both private and public providers, as elder care policies in Spain have a high degree of marketization: 73 % of a total of 372,985 nursing homes beds are operated by the private sector. The research questions that guide our study are the following: What are the elements of service delivery that policy providers are obliged to provide? And, what issues are de facto important for business associations in the elderly care sector when communicating with the public?

Other studies have analyzed the shortcomings of private-sector participation in public services provision in terms of their transparency and accountability. This study analyzes transparency in the provision of information towards the beneficiaries of the services. Following Grimmelikhuijsen and Welch (2012), we focus on transparency in two policy dimensions, namely, policy content and policy outcomes. In addition, drawing on Donabedian (1988), we identify three general topics over which policy providers can provide information, as they are crucial for measuring the quality of nursing home services: a) structure, which mainly refers to policy content aspects related to the providers’ material and human resources; b) process, which also refers to policy content aspects such as the management of care plans, the services provided and other aspects of the day-to-day operation of the facilities; and c) outcomes, which refer to the results of the care services such as information on evaluations and inspections.

The objective of the study is to analyze, on the one hand, the extent to which nursing home service providers (public and private) are obliged to supply information about their performance. For this, the article analyzes the formal obligations of transparency for both public and private facilities across the seventeen autonomous communities (ACs). On the other hand, and given that a large percentage of services are provided by private providers (73 %), we analyze the contents of the messages issued by the three biggest business organizations/associations that operate in Spain: the Business Federation of Dependence Assistance (Federación Empresarial de la Dependencia, FED), the Association of Companies for Dependency Services (Asociación de Empresas de Servicios para la Dependencia, AESTE) and, the Business Circle of Caring for People (Círculo Empresarial de Atención a las Personas, CEAPs). Although these organizations do not directly implement nursing home services, their analysis is crucial as they represent a high percentage of private firms responsible for implementing these services across ACs.

The analysis focuses on the messages issued by these organizations on social media, and more specifically on Twitter. The analysis of social networks during the pandemic is particularly important since these tools have permitted continued interaction between relevant actors (for example, politicians with citizens, public servants with citizens and, service providers and users) despite restrictions imposed during the state of alarm (Chaves-Montero et al., 2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic, elderly home care residents were the most vulnerable population, and facilities were challenged to respond to the health crisis. Moreover, we opted to analyze the Twitter accounts kept by sectoral business associations to determine whether transparency has been a concern for the industry regardless of the regulatory requirements faced by direct service providers.

The empirical analysis is based on two approaches. First, we conduct a systematic document analysis of the normative frameworks that regulate service provision in the seventeen ACs. At a second stage, we use topic modeling, an unsupervised machine learning technique, to analyze the topics these three business associations in Spain have been concerned about. By doing so, we investigate the extent to which the topics retrieved by a structural topic model on the corpus of messages were affected by the COVID-19 crisis. In addition, we perform a dictionary analysis to assess the prevalence of keywords related to transparency issues over time. These analyses allow us to examine the way in which these associations have responded to the outbreak by providing crucial information on the performance of services and to identify relevant patterns. To do this, we collected 3,042 tweets posted by the three largest elderly residence business groups in Spain. We identify whether the topics followed a different trend before and during the COVID-19 outbreak as well as the prevalence of keywords over a period of 12 months before and after the state of alarm in the country.

The systematic analysis of formal rules shows that the relatives of nursing home residents get information on the services through three main tools: contracts, bulletin boards and “visible information”. Our study also shows that ACs do not share a standardized pattern to provide information and that, in general, the obligations to provide information do not cover indicators that are crucial to examine the quality of the services. For example, and although ACs include more formal stipulations for the provision of information about the processes of the services, their fulfillment varies widely across ACs. More importantly, the analysis shows scarce mechanisms to provide information on the structures and the outcomes of the services. This implies that regional legislations do not mandate, for example, the provision of information to the residents’ relatives regarding the results of inspection, supervision, and control assessment over the facilities. From the dictionary analysis we also find that the process dimension of transparency is the most widely discussed by business associations of the sector, and that the topics focused on the structures and policy outcomes are not extensively included in their communication messages. Nevertheless, from the topic modeling analysis our analysis provides evidence that transparency is a concern in their social-media communication strategies both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it is worth noting that transparency is present in a topic which also includes references to greater professionalization. Further research on a larger corpus that includes direct providers is necessary to determine whether transparency in the sector is implemented as an active policy that covers core dimensions and topics of the (quality) of the services.

Studies on transparency have mainly focused on investigating it at governmental level. However, in this study we analyze the provision of information from the three main business associations in the sector in Spain. This study has important normative implications. Prior to the pandemic, some comparative studies highlighted important shortcomings in the performance of these services, even in more generous welfare states (e.g., Broms et al., 2020). Patient ombudsman bodies and civil society organizations (e.g., Amnesty International) pointed out that authorities’ COVID-19 response was inefficient and inadequate (Moreira et al., 2021), and that some home care residents suffered the violation of their human rights; particularly, due to the omission of information to the residents’ relatives. Our analysis is crucial as some of the most important allegations made by relatives were about the lack of information and transparency of service providers. The way in which the COVID-19 affected nursing home residents required openness and transparency about their conditions, as well as an active communication between providers and relatives.

This article is structured as follows. Sections 2 and 3 present the theoretical discussion about the conceptualization of transparency and its connection with different types of service providers. After that, sections 4 and 5 present the Spanish case and the methodology used. In section 6 a comparative analysis is performed throughout the seventeen Autonomous Communities examining the extent to which the regional formal obligations include mechanisms for regulating the provision of information towards beneficiaries. Finally, in section 7 we present a brief analysis, through topic modeling, of the salient topics that have dominated the messages of the three most important business associations that represent private providers in Spain as well as the salience of transparency-related keywords over time.

TRANSPARENCY: EXAMINING PROVISION OF INFORMATION FROM SERVICE PROVIDERS TO BENEFICIARIES[Up]

Governmental transparency is generally assumed as a “key of better governance” (Grimmelikhuijsen et al., 2013). This is because it can contribute to preventing corruption and to promoting efficiency in policy performance by enhancing the processes of information provision (Hood, 2007). In addition, as some scholars state (Birkinshaw, 2006; Grimmelikhuijsen et al., 2013), transparency is crucial as a human right given citizens’ right-to-know in democratic regimes. Some studies within the literature on transparency focus on formal transparency by examining the extent to which laws and stipulations regulate the provision of information (e.g., Cucciniello and Nasi, 2014). Other studies investigate the performance and the effects of the de facto provision of information, by assessing the performance and the factors that influence government websites transparency (Grimmelikhuijsen et al., 2013) and computer-mediated transparency (Meijer, 2009). In addition, other scholars provide important insights on the intersection between transparency and multilevel structures of governance by investigating, for example, transparency at the central tier of government (Bastida and Benito, 2007), at the regional level (Benish and Mattei, 2020) and, at the local level (Ferreira da Cruz et al., 2015; Grimmelikhuijsen and Welch, 2012). Some authors have examined the explanatory variables that influence transparency while others have focused on its consequences one aspects like levels of trust and government legitimacy (ibid.). The current article contributes to the analysis of transparency of social services; in particular, we focus on formal and de facto mechanisms to provide information about nursing home services. To this end, in this section we conceptualize transparency as it is used in this study, as well as the type of providers and recipients of such transparency.

In line with Grimmelikhuijsen et al., this paper understands transparency as “the availability of information about an organization or actor that allows external actors to monitor the internal workings or performance of that organization” (2013: 576). As Meijer has emphasized, this definition implies an “institutional relation between an actor”, or a set of actors who are the object of transparency (as they can be monitored), and another actor, or a set of actors who are the subject of transparency and the information recipients (2013: 430). In this sense, in democratic regimes one might identify different types of information providers (e.g., central governments, regional governments, municipalities, street-level public officials, high-ranking officials, private providers), as well as different types of recipients or forums of such information (e.g., political representatives, courts, citizens in general, and beneficiaries). Our research is focused on transparency in relationships between service providers and beneficiaries.

A core question deals with clarifying the identity of the information provider when it comes to welfare services. Derived from the diffusion of New Public Management (NPM) reforms, the implementation of social services through private providers has been widespread. At the same time, the implementation of governance reforms has led to new modes of participation of societal actors in the provision of services, such as public-private partnerships. Although these new modes vary, one of their main objectives is to transfer “the risk and responsibility” of service delivery from public organizations to private providers (Reynaers and Grimmelikhuijsen, 2015). New modes of governance arrangements have also been predominant in the delivery of public services in different types of welfare regimes, such as in the provision of care services for the elderly. All these reforms have introduced more complex transparency systems since both public and private service providers are responsible for offering information on home care services.

Against this backdrop, these reforms have also led to research on the effect of contracted services, and on the quality, transparency, and accountability of the services. Some scholars have examined whether these new modes of governance have shortcomings when dealing with transparency issues and, specifically, when it comes to balancing efficiency and the democratic requirements of openness (ibid.). In a similar sense, Skelcher and Smith (2014) find that marketization of the provision of services produces lower levels of participation, lower control of public officials, and lower policy supervision and oversight which, in turn, leads to a decline in service performance. Hence, according to Skelcher and Smith (ibid.), a higher marketization of services might also lead to shortcomings in accountability arrangements. From these previous studies we know that a higher presence of private or hybrid providers might lead to shortcomings in the supervision and oversight that public bodies and political actors can carry out.

It is therefore necessary to emphasize that in welfare services where private organizations “become responsible for public service delivery, transparency is important for the public and external stakeholders to assess an organization’s internal workings and performance” (Reynaers and Grimmelikhuijsen, 2015: 2). That is, in this new mode of governance, transparency “allows to examine whether service providers are competent and acting in the public interest (ibid.); and at the individual level, it allows users/beneficiaries to have access to crucial information that affects their well-being. In addition, the provision of information is a necessary condition for the subsequent stages in the process of accountability; specifically for the evaluation and sanction phases.

TRANSPARENCY IN NURSING HOME SERVICES: POLICY DIMENSIONS AND ELEMENTS OF THE TRANSPARENCY OF THE SERVICES[Up]

By adapting Heald’s work (2006), Grimmelikhuijsen and Welch proposed to examine transparency in three core policy dimensions: a) transparency of decision-making processes, b) transparency of policy content information, and c) transparency of policy outcomes (2012: 563). The first element refers to “the degree of openness about the steps taken to reach a decision and the rationale behind the decision” (ibid.). The second (policy content transparency) refers to the information disclosed about crucial aspects of policies, such as the measures that will be adopted, the way in which such measures will be implemented and, their implications. Finally, policy outcome transparency “captures the provision and timeliness of information about the effects of policies” (ibid.). Since our research addresses transparency in service implementation, that is, the extent to which policy providers offer crucial information to beneficiaries, we focus on two of the above dimensions: transparency of the content and the outcomes of nursing home services.

To further specify the elements of transparency that fall under each policy dimension, we draw on the literature on quality of home care services. In their study on quality indicators in nursing home care processes, Saliba and Schnelle show that residents and their relatives emphasize the importance of having information on aspects related to the quality of services (2002: 1421). These include the choice and control over daily activities, assistance with activities of daily living, ongoing information about their health status, participation in care planning and, consistent access to their physician when needed. To identify these specific elements, we draw on the classic approach by Donabedian (1988; see an empirical application by Broms et al., 2020), who emphasized three crucial general topics to measure the quality of services, namely structure, process, and outcomes of services.

The first topic refers to the structural quality of the facilities, which covers “the context in which care occurs, such as material resources (money and physical facilities), human resources, and organizational structure (organization of management, human resource practices or methods of peer review)” (ibid.: 534). Given this conceptualization, this topic can be placed in the policy content dimension. Hence, its specific elements can cover the provision of information by service providers on aspects related to staff ratios (i.e., ratios of nursing and medical staff) and qualifications; resident ratios; and the physical conditions of the facilities. This topic also covers the provision of information about facilities governance rules, such as information on their ownership and their organizational structure (see Figure 1).

The second broad topic is the quality of the process, which can also be placed in the policy content dimension, and which refers to the provision of information on aspects such as the management of care plans, the services provided, daily activities and food provision to residents, as well as the communication and participatory channels for residents and their families. Given that marketization relies both on the notion of high competition between providers and on a clear definition of contracts between providers and beneficiaries (ibid.), a core aspect is the provision of information that is regulated in such contracts.

Finally, the third broad theme is the quality of the outcome, which refers to the results of the policy (ibid.), such as information on evaluations and inspections from both users and public bodies. Since the marketization of social services has increased in recent decades, this aspect covers information on the efficiency of the services, as well as on their innovation and equity. In this dimension, providers can also offer information about price improvement, quality systems and, more specific aspects of elder care policies such as indicators on pressure ulcers and resident mortality rates.

Table 1.

Analytical framework to assess transparency in nursing home services

| Dimensions | Policy content transparency | Policy outcome transparency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topics | Information on the structure | Information on the process | Information on the outcomes |

| Elements | Physical facilities Human resources Staff qualifications (nursing and medical) Staff ratios Ratios of residents Organizational structure Facility head Ownership of the facility |

Services provided Contracts Planning Daily life activities Schedules Meals/food provision Privacy Assistance provided Physical activities Participation channels |

Efficiency Innovation Equity Prices Inspections Quality systems Pressure ulcers Residents/Beneficiaries Evaluations Mortality rates |

Source: Own elaboration based on Donabedian (1988), and Broms et al., (2020).

NURSING HOME SERVICES IN SPAIN AND THE EFFECT OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC[Up]

This study empirically tests the analytical framework in the case of the transparency of nursing home services in Spain. Long-term care policies in Spain rely on regional governments, which “are responsible for regulating, financing and providing these services, as well as for guaranteeing care quality” (Zalakain et al., 2020: 3). As for the central government, it “dictates the financial and regulatory functions for the National Long-Term Care System (SAAD), which is provided mainly through the regional Social Services” (ibid.: 4). However, the provision of nursing home services is the responsibility of the autonomous communities, which finance the services “through taxation, social security contributions, and copayment by users” (Rodríguez-Cabrero and Marbán, 2013: 203). Hence, this is a decentralized policy the regulation and implementation of which rest on the ACs.

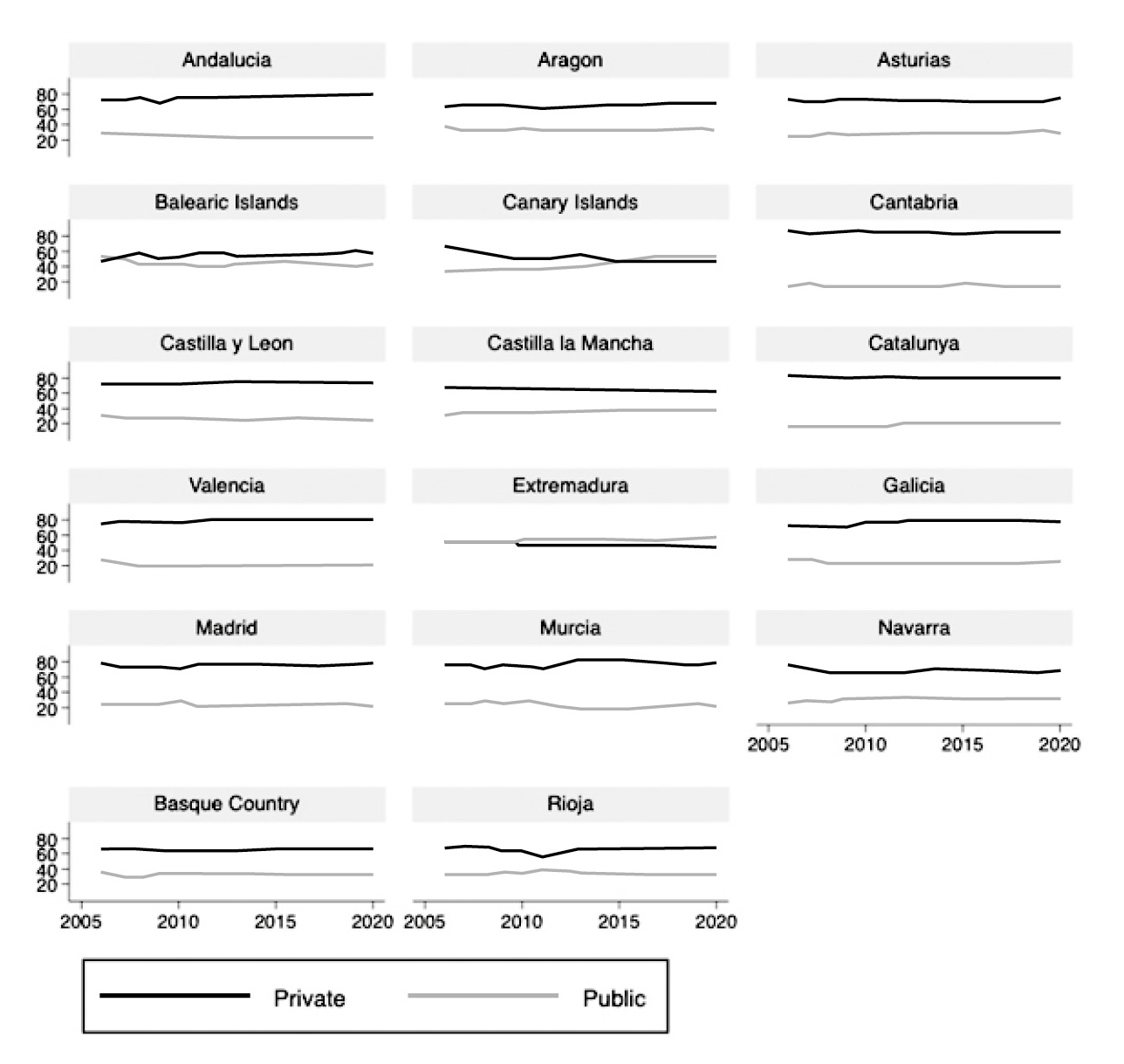

In general, regional authorities manage the provision of these services in different ways, through either direct provision arrangements or contracts with privately-run entities. Regional legislations state that service providers include public providers, private for-profit organizations, and nonprofit entities/foundations/associations. Although different arrangements are allowed, this is a policy with a high participation of the private sector. As it can be seen in Figure 1, in 2020, 73 % of beds in Spain were provided by private facilities. Yet, differences can be observed across ACs: For example, the provision by private providers is nearly 80 % in ACs such as Catalonia, Andalusia, Cantabria, Valencia, Madrid and, Murcia, whereas in a very few number of regions including Extremadura, the Canary Islands and the Balearic Islands this percentage falls below 60 %. In addition, Figure 1 shows that the marketization of the services has had a prominent role in the majority of ACs over time.

Figure 1.

Percentage of nursing home beds across ACs: public and private providers

Source: Own elaboration based on data provided by Abellan García et al., (2021)

The COVID-19 crisis was a core aspect that affected service performance, thus reflecting its limitations. As in many European countries, the COVID-19 crisis arrived in a context when elderly care policies had a marginal role. As some studies have shown, the people living in nursing homes were the most affected by the pandemic (Daly et al., 2021; León et al., 2021). In this sense, both governments and service providers were challenged to respond to the fast spread of COVID-19 and its effects in nursing home residents (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Population size, nursing home residents and number of COVID-19-related deaths in the Spanish ACs

| AC | Population size | Population over 65 years | Population over 65 (%) | Population over 75 | Population over 75 (%) |

Number of nursing

home residents (in 2019) |

No. of COVID-19-related deaths (updated to March 7th, 2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | 8464411 | 1470813 | 17 | 698359 | 8 | 42585 | 2206 |

| Aragon | 1329391 | 288662 | 22 | 152074 | 11 | 18424 | 833 |

| Asturias | 1018784 | 266567 | 26 | 133545 | 13 | 12313 | 709 |

| Balearic Islands | 1171543 | 183224 | 16 | 83772 | 7 | 5110 | 262 |

| Basque Country | 2220504 | 499432 | 22 | 250683 | 11 | 20534 | 1113 |

| Canarias | 2175952 | 351122 | 16 | 157237 | 7 | 7327 | 75 |

| Cantabria | 582905 | 129425 | 22 | 63422 | 11 | 6024 | 289 |

| Castile la Mancha | 2045221 | 390226 | 19 | 208503 | 10 | 26649 | 1627 |

| Castile Leon | 2394918 | 613704 | 26 | 336339 | 14 | 46457 | 2955 |

| Catalonia | 7780479 | 1468361 | 19 | 725347 | 9 | 62015 | 3410 |

| Ceuta | 84202 | 10144 | 12 | 4508 | 5 | 218 | 3 |

| Extremadura | 1063987 | 223246 | 21 | 118189 | 11 | 13751 | 789 |

| Galicia | 2701819 | 687824 | 25 | 364772 | 14 | 21179 | 789 |

| Madrid | 6779888 | 1208738 | 18 | 595652 | 9 | 48768 | 1496 |

| Melilla | 87076 | 9206 | 11 | 4042 | 5 | 271 | 2 |

| Murcia | 1511251 | 237967 | 16 | 114296 | 8 | 5192 | 328 |

| Navarra | 661197 | 130647 | 20 | 65533 | 10 | 6149 | 414 |

| Rioja | 319914 | 67321 | 21 | 34867 | 11 | 3209 | 276 |

| Valencia | 5057353 | 981752 | 19 | 470753 | 9 | 26810 | 2028 |

Sources: Own elaboration. Data on the population size are obtained from INE. Data on nursing home residents and on Covid-19 related deaths (updated to March 7th, 2021) are obtained from the IMSERSO dataset (available at: https://cutt.ly/2TbecL1). The number of nursing home residents in 2019 was obtained from Abellan-García (2021).

Given the impact of the COVID-19 crisis, we have also examined whether and how transparency on the content and the outcomes of nursing services have varied in the context of a global health crisis. In general, it might be expected that transparent actions were promoted in times of crisis with the aim of mitigating the surge of COVID-19. In the next sections, we examine the extent to which there were formal rules regulating the transparency of services before the pandemic, and how have been the communication practices by pertinent business associations before and during the outbreak.

METHODOLOGY[Up]

Our empirical analysis is developed in two stages. First, we examine the extent to which legal provisions of nursing homes services across ACs include mechanisms to provide information on the policy phases and the topics highlighted in the analytical framework. Second, we investigate the topics over which business associations are de facto informing through social media, specifically through their Twitter accounts.

First stage: Analysis and codification of legal documents on nursing home services[Up]

Before analyzing the actual information facilitated by the main business associations in Spain, we examined the formal obligations that both public and private providers should fulfill when informing the beneficiaries of services about their performance. To do this, we revised regional legislations on care services (See the list of the legislative texts examined in Annex 1).

In particular, we examined whether regional legislations stipulate the provision of information for beneficiaries about the structure, processes and outcomes of services; for instance, information about the organizational chart, services provided, calendar of activities, submission of complaints and suggestions, participation channels, among others. This is important because formal rules, understood as written rules and procedures (Pugh et al., 1968), serve as constraints that affect de facto transparency by service providers. As Meijer emphasizes, “legal frameworks influence the emergence of transparency practices” (Meijer, 2013: 429).

Second step: Dictionary analysis and topic modeling on issues covered by business associations[Up]

Secondly, we perform a quantitative text analysis on a corpus of tweets issued by the main business associations of the sector in Spain. This analysis consists of two elements: the first is a topic model that seeks to uncover latent themes inside the corpus through unsupervised machine learning. The second is a theory-driven dictionary analysis (see Table 1) in which keywords associated with three dimensions of transparency are detected throughout the corpus in order to identify both cross-sectional (among actors) and time-dependent (pre/post COVID-19 restrictions in Spain) patterns in language usage.

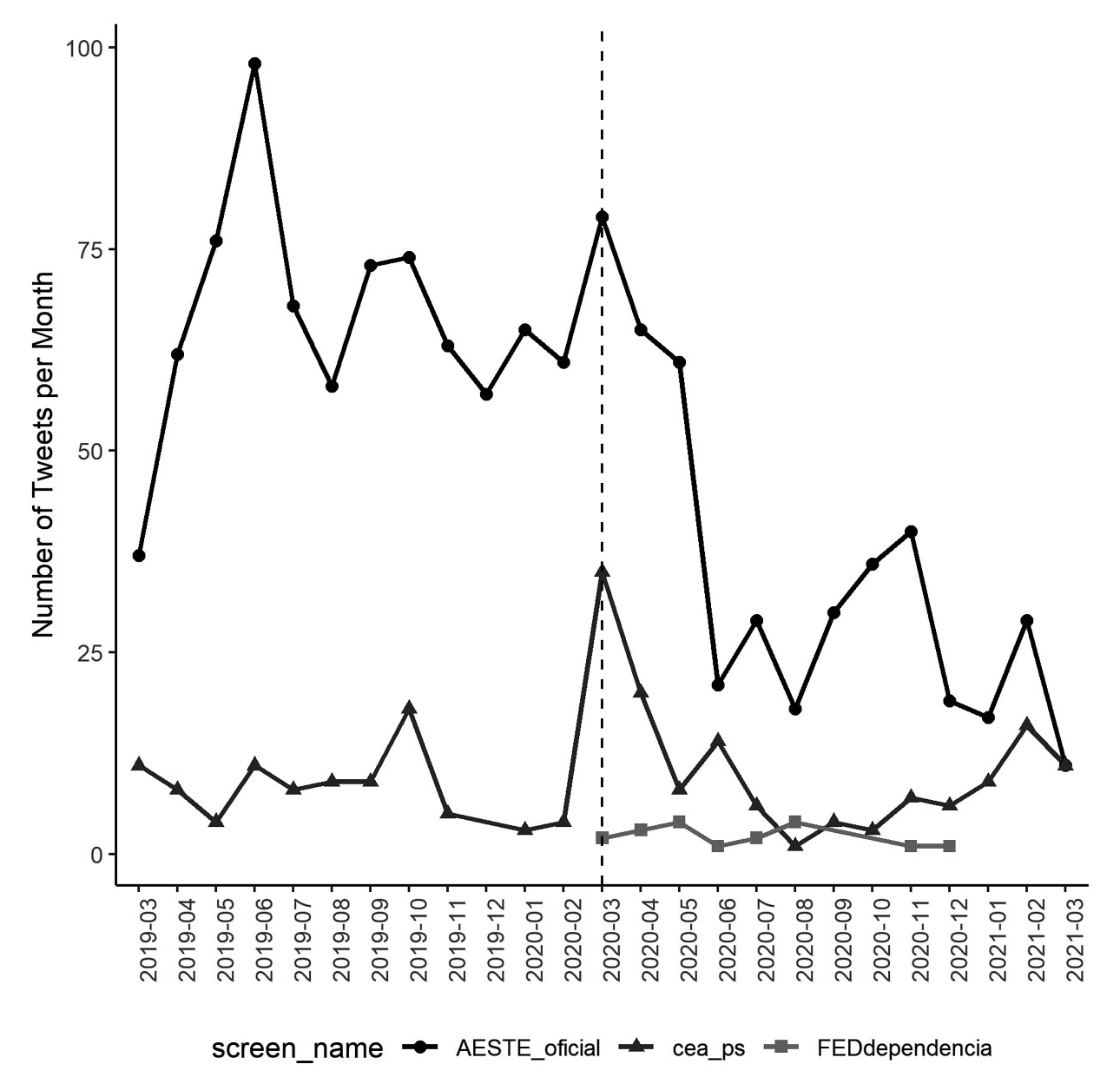

We examine the way in which these associations provide crucial information on the performance of the services. Although these organizations do not directly provide nursing home services, the analysis of their messages on Twitter is crucial as they represent a high percentage of private firms that are responsible for implementing these services across ACs. The organizations under examination are the three biggest business organizations/associations that operate in Spain: Business Federation of Dependent Assistance (Federación Empresarial de la Dependencia, FED), created in 2006; the Association of Companies for Dependency Services (Asociación de Empresas de Servicios para la Dependencia, AESTE), founded in 2002; and the Business Community for the Assistance of People (Círculo Empresarial de Atención a Personas, CEAPs), created in 2016. These associations encompass operators of nursing home facilities, day and night centers, tele-assistance services, among others. The corpus consists of 3,042 tweets issued by three institutional actors: a) cea_ps, b) AESTE_oficial, and c) FEDdependencia dating back to the 14th of November 2013. Since the COVID-19 crisis has had devastating effects, we covered a period before and during the outbreak. We select tweets issued 12 months before and after the state of alarm was declared in March 2020, which results in a corpus of 1,495 document-level observations. These tweets were collected using the R statistical programming language, which was also used for both the topic model and the dictionary analysis.

We have opted to analyze the Twitter accounts issued by sectoral business associations in order to determine whether transparency is a concern for the industry regardless of the regulatory requirements faced by direct service providers. Furthermore, and in order to avoid the third-party content that is often displayed on website portals, we have opted to analyze direct social media posts authored by the organizations themselves.

FORMAL TRANSPARENCY ACROSS THE SPANISH AUTONOMOUS COMMUNITIES[Up]

In this section we analyse all the relevant legislation on social services and on the regulation of home care facilities across the ACs. In particular, we pay attention to the mechanisms for information provision to the beneficiaries and their relatives.

It is worth noting that all ACs follow the Spanish Act 39/2006 on the Promotion of Personal Autonomy and Care for Dependent Persons (Dependency Act), which creates a system of social protection (Sistema de Autonomía y Atención a la Dependencia, or System of Autonomy and Dependency Care) (Rodríguez-Cabrero and Marbán, 2013: 202). At the central level, this legislation “universalizes a social benefits system for the entire dependent population” (ibid: 205). Although this system is coordinated by a Regional Board (Consejo Interterritorial) that “lays down the basic conditions” (ibid), each AC is responsible for the implementation of this service. In addition, another common aspect across all ACs is that all policy beneficiaries have rights regarding the confidentiality of their personal data. That is, the confidentiality of the personal data contained in administrative files and personal history documents. These stipulations are included in the legislation on personal data protection at both national and regional levels.

The revision of regional laws across all 17 ACs shows that the relevant information the services is provided through three main tools: contracts, bulletin boards, and information that according to regional legislations “must be visible and available” without stipulating the place and format. The legal stipulations at the regional level only create these three mechanisms, used by ACs in varying degrees. It is worth noting that each facility can adopt other tools for providing information to the residents’ relatives, such as the informative brochures in Valencia.

In addition, it is found that regional legislations set out mechanisms for providing information on policy content (process and structure) and outcome. Information on the policy process includes aspects like internal operational rules, beneficiaries’ rights and obligations, legal representatives and professionals, services provided, participation channels for relatives, visiting arrangements, scheduled activities. We also identify indicators related to the facility structures, such as the number of places, the number of staff and the organizational structures. Finally, we identify whether regional laws include indicators for providing information on the policy outcomes, such as information for submitting complaints and suggestions, results of procedures of control and evaluation of the services.

The results of our analysis show that only some ACs regulate the provision of information to beneficiaries through the contracts signed between facilities and users —or their relatives or legal representatives. Some examples are the Balearic Islands, the Basque Country, Valencia, and Aragon (see Table 3). However, items included in the contracts vary widely. For example, the Basque Country stipulates that the users or their legal representatives should receive and accept the content of 1) the internal regulation of the facility, 2) a copy of the Charter of rights and obligations of users and professionals of social services, and 3) information on the procedure to submit suggestions and complaints. As for the content of the internal regulation, the legislation of the Basque Country states that this must include aspects such as: objectives of the services; requirements for access; capacity (number of “beds”); channels for “democratic participation of users or their legal representatives”; list and prices of the services offered, detailing those included in the cost of stay and the optional ones; system for submitting and collecting suggestions and complaints; information on visiting hours and ways for external communication; information on the participation bodies of beneficiaries/users. In contrast, the information that should be provided in contracts according to the legislation of Valencia also states that is limited to the services offered and their prices (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Information provided through contracts between users and providers, bulletin boards and “visible information”

| Andalusia | Aragon | Asturias | Baleariq I. | Basque C. | Canary Islands | Cantabria | Castille Leon | Castille Mancha | Catalonia | Extremadura | Galicia | La Rioja | Madrid | Murcia | Navarre | Valencia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information on the structure | Identification data of the facility (number of register and authorization) | V | V | V | B | V | V | C; V | V | — | — | B; V | — | V | V | B | — | B |

| Organizational structure/chart | B | — | V | B | — | C; B | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | B | — | B | |

| Capacity/number of places | — | — | — | — | C | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | V | — | — | — | — | |

| Information on the process | Internal regulation | C | — | V | C; B | C | C; B | — | C; V | C; B | — | — | — | C; V | — | B1 | C | C |

| Services provided | — | — | V | C | C; V | C; B | V | C; V | C | V | — | — | C; V | — | B | C | C;B | |

| Scheduled activities (general/annual) | B | — | — | B | — | B | — | V | — | — | — | — | — | — | B | — | B | |

| Calendar with scheduled activities (monthly/weekly) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | V | — | — | — | — | — | — | B | — | — | |

| Procedures for submitting complaint and suggestions | — | — | V | B | C | C; V | — | V | — | — | — | — | C; V | — | B | C | B | |

| Diet and menu programming | B | — | B4 | B | — | B | B; V | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | B | — | B | |

| Participation channels for users (“juntas de participación”) | — | — | B; V | C3 | — | B | — | V | B | — | — | — | V | — | — | — | — | |

| Mailbox of complaints and suggestions | — | — | V | — | V | V | — | V | — | V | — | — | V | — | — | — | V | |

| Channels/bodies for the participation of users —or their legal representatives or relatives | — | — | — | — | C | C | — | C | C | — | — | — | C | — | — | C | — | |

| Minutes of board meetings (“actas reunión de consejo”) | B | — | — | — | — | B | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Visiting arrangements and external communication | C | — | V | C; B | C | — | — | — | C; B | — | — | — | C; V | — | B | C | — | |

| Charter of rights and obligations of users | — | — | V | C; B | C | C | — | C; V | C; B | — | — | — | C; V | — | — | C | C | |

| Charter of rights and obligations of professionals | — | — | — | — | C | C | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Information on the process | Rights and duties of users’ legal representatives, and their relatives | — | — | V | — | C | C | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Rights of users in terms of the services offered | — | — | V | C | C | C | — | C | C | V | — | — | C; V | V | — | C | C | |

| Information on the outcomes | Price list of the provided services | C; B | B | — | C; B | C; V | B; V | C; B | C; V | C | — | — | — | C; V | — | B2 | C;B | C;B |

| Instructions and plan in case of emergencies | — | — | — | B | V | B | — | — | — | V | — | — | — | — | B | — | B | |

| Health approval of collective dining rooms | — | — | — | — | — | — | V | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | B | — | — | |

| Certification of quality accreditation | — | — | V | — | — | B; V | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | B | |

Source: Own elaboration.

Other regions, such as Murcia, state that information should be public in a “bulletin board” which can provide data on: the registration data of the center; general services provided; price list of the services; organizational structure/chart of the center; availability of complaint forms and information on the procedure of claiming directly before the competent department; calendar with scheduled activities; instructions to follow in case of emergencies; office hours; diet and menu programming; and health approval of collective dining rooms; among others. In Extremadura, although the regulation stipulates the obligation to have a visible bulletin board in every center, the content to be shown is neither stipulated nor detailed (see Table 3).

In addition, although some regions do not clearly specify the existence of a “bulletin board”, some of them, such as Cantabria, state that facilities should show certain information to users and relatives in a “visible place”, such as that related to: registration data of the center, services provided, participation channels for users in the improvement of the services, and information for submitting and collecting suggestions and complaints (see Table 3).

Our systematic analysis of regional laws demonstrates that ACs do not share a standardized pattern to provide information and that, in general, the obligations to provide information to the beneficiaries of the services are very limited. For example, although ACs have developed specific legislations to regulate the physical conditions of the facilities, we have identified only three specific items that can be provided to the residents’ relatives: identification data of the facility, information on the organizational structure and number of places. While the majority of ACs stipulate the provision of information on the identification of the facility (13 ACs out of 17), only six ACs provide information on the organizational structure of the facility, and only one (the Basque Country) obliges to inform about the number of places.

Finally, and although ACs include more formal stipulations for the provision of information related to the processes of the services, their fulfillment across ACs have a wide variation. Our analysis also shows that there are scarce mechanisms to provide information on the outcomes of the services. For example, regional legislations do not stipulate the provision of information to the residents’ relatives regarding the results of inspection, supervision, and control assessment over the facilities. When it comes to information on the quality of the services, only three ACs include formal provisions to inform about quality accreditations of the facility.

TOPIC MODELING AND DICTIONARY ANALYSIS OF BUSINESS ASSOCIATIONS CONCERNS BEFORE AND AFTER COVID-19 RESTRICTIONS[Up]

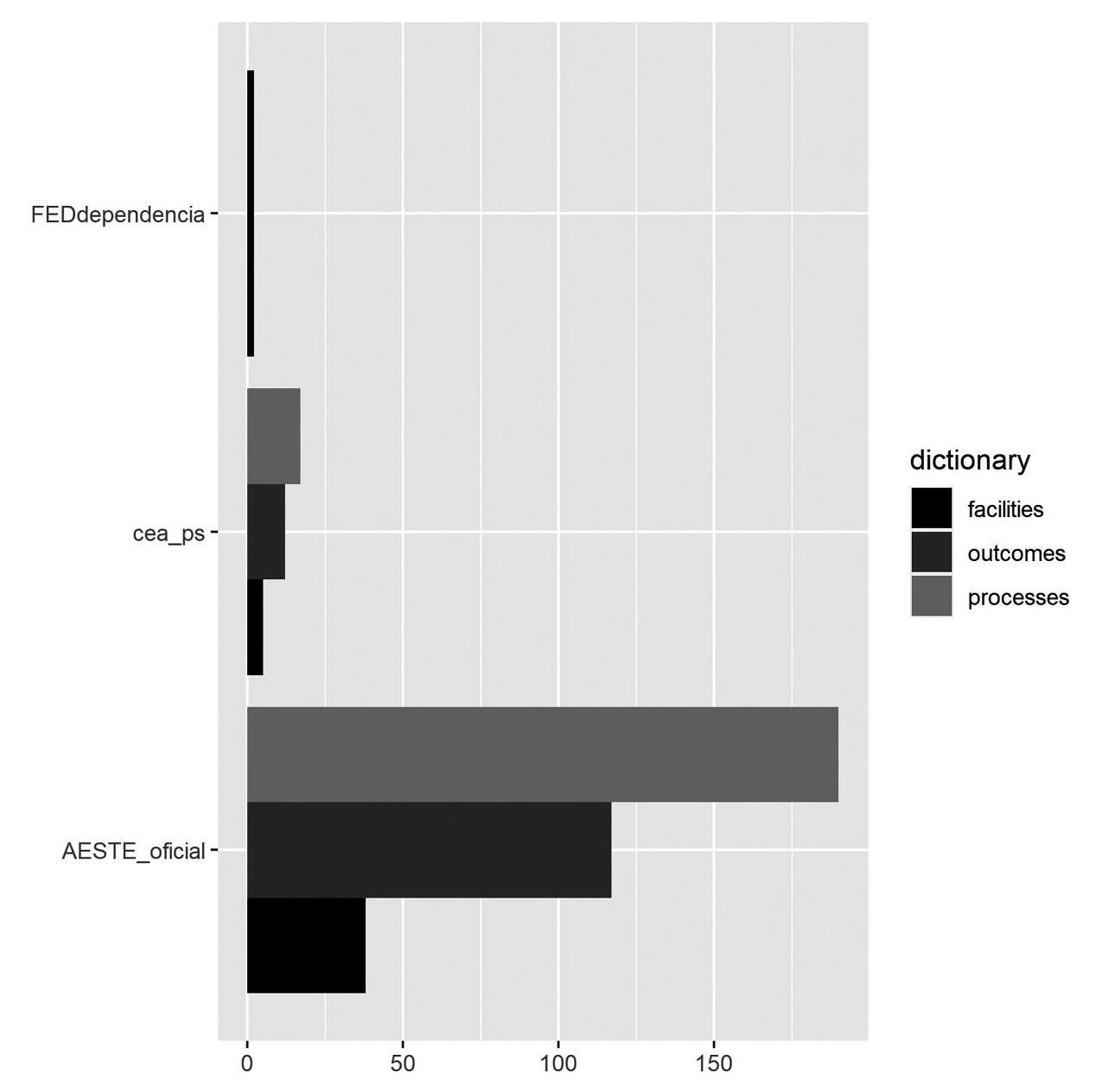

In this section, we examine the latent topics uncovered by a structural topic model (STM) from the corpus of tweets issued by business associations before and during the COVID-19 outbreak. Subsequently, we examine the results of the dictionary analysis of transparency-related keywords in three dimensions: a) facilities, b) outcomes, and c) processes.

Topic modeling: identifying the salience of latent themes[Up]

The objective of the topic modeling analysis is to determine whether the model is able to uncover transparency-related (or otherwise theoretically relevant) latent themes inside the tweet corpus with limited input from the researchers. Topic models rely on an unsupervised machine learning algorithm that calculates the probabilistic distribution of topics for all documents in a corpus, as well as the terms (words or n-grams) that are likely to be generated by a given topic based on a number of topics k determined by the researcher.

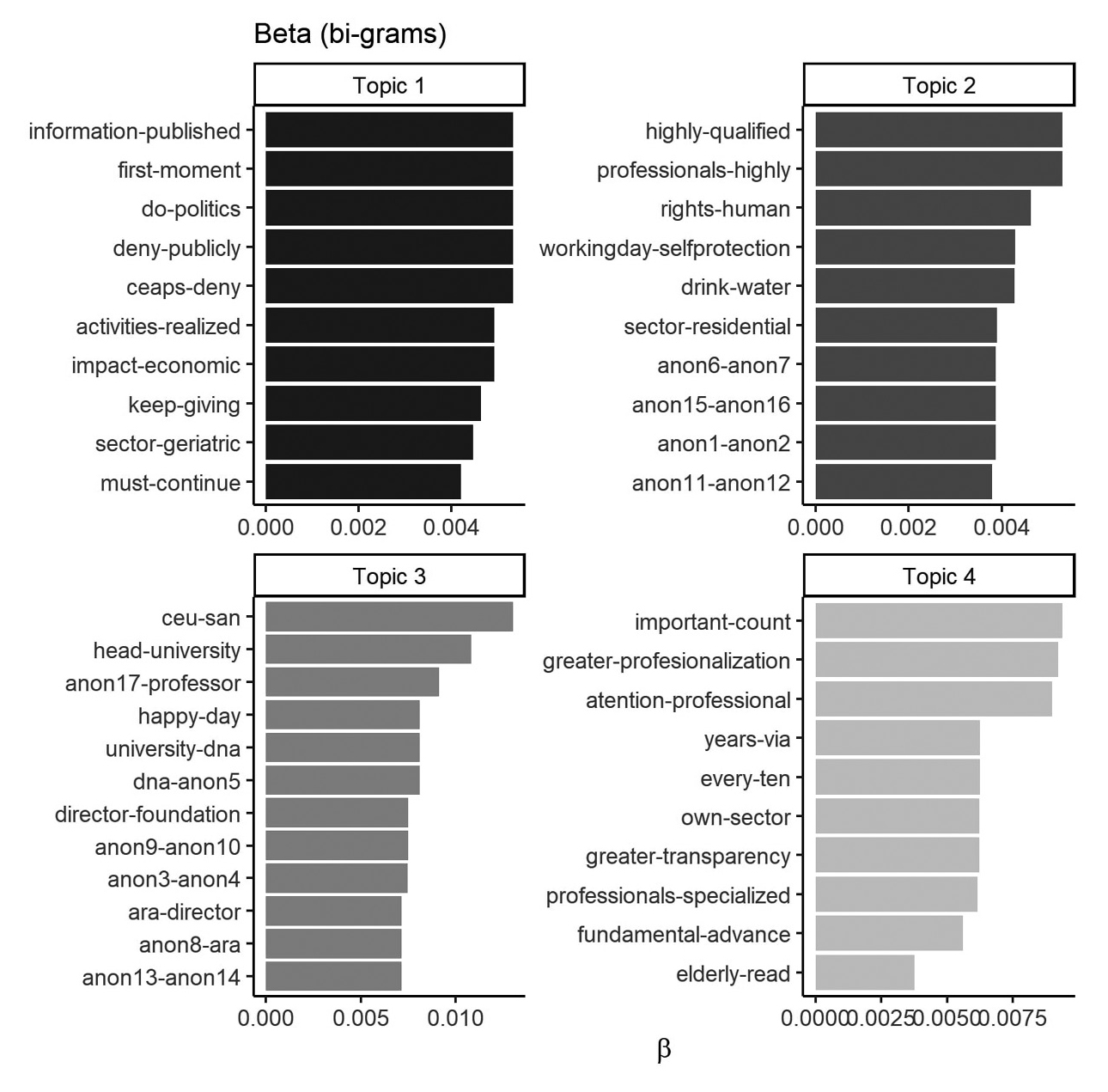

The outputs of the model include topic content and topic prevalence. For the former, we examine the most probable terms (highest beta values) for each of the topics uncovered to look for meaningful terms and associations. For the latter, we look at the proportion that a given topic (gamma) has across documents, actors and time. Topic modeling has been used extensively to trace the salience of latent themes in text over time (see for instance, Schoonvelde et al., 2020).

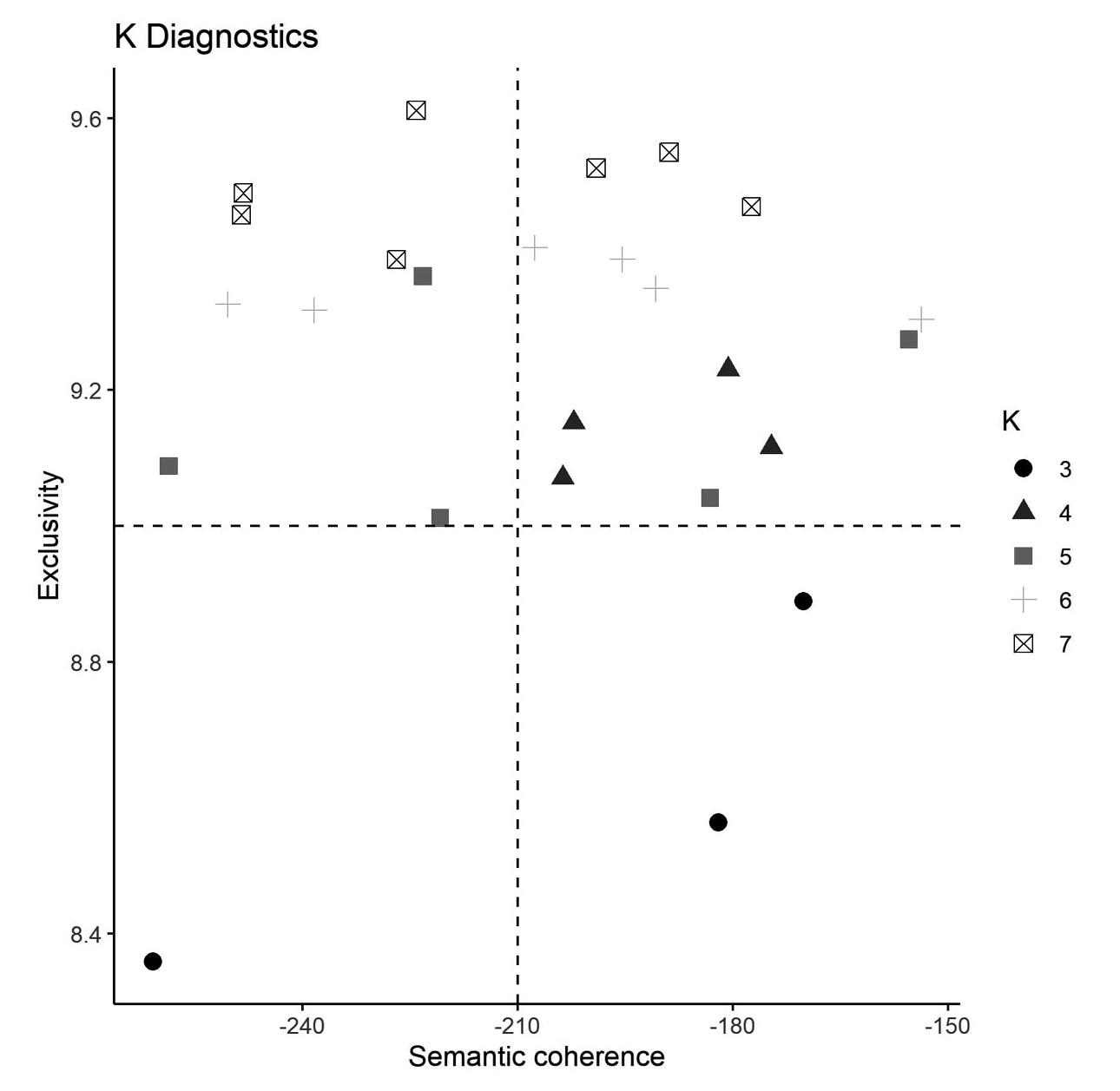

The parameter k of our topic model was selected by considering the trade-off between term exclusivity and semantic coherence (see appendix) based on test models run in iteration at various levels of k (3-7). A k level of 4 was selected, meaning that the classification algorithm was tasked with determining the content (beta) and prevalence (gama) of four topics throughout the corpus. We used the structural topic model (STM) algorithm where a dummy variable for pre and post COVID-19 and the actor were added as regressors for topic prevalence. Furthermore, we tokenize the term by bi-grams (word pairs) rather than by single words in order to improve the interpretability of the outputted topics (Roberts, et al., 2014).

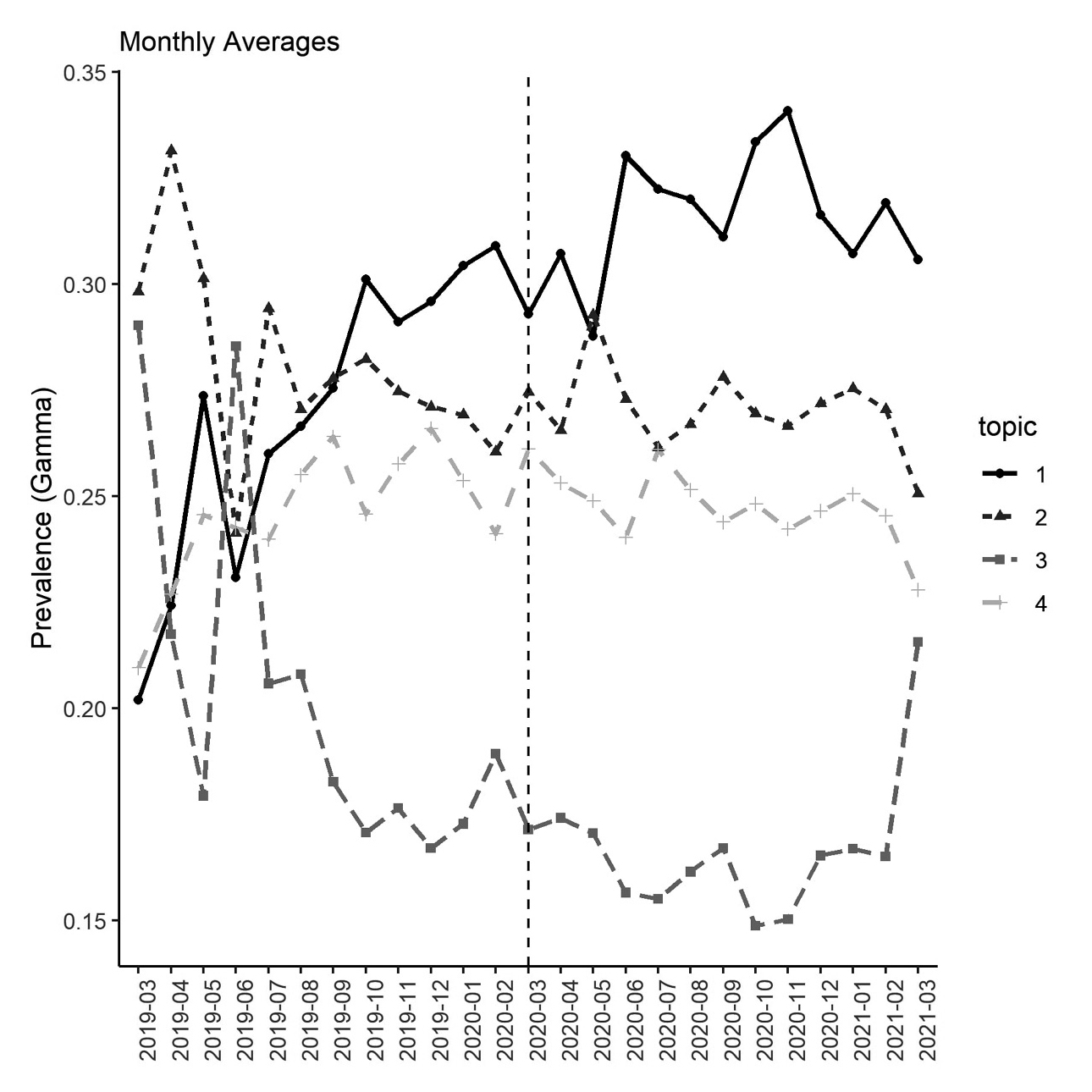

Given the unsupervised nature of this approach, the interpretation of topics requires some degree of discretion by researchers as well as several robustness tests to limit the risk of biased interpretations or “reading tea leaves” (Chang et al., 2009). We performed several robustness tests with k +/- 1 and stepwise regressions in the prevalence allocation within the STM but found consistent results on the distribution of topical prevalence (gamma) and content (beta). As shown in Figure 2, our model identified transparency (mayor-transparencia) and professionalization (mayor-profesionalización, profesionales-especializados) within the top 10 elements (beta) of Topic 4. This suggests that concerns over transparency are thematically connected to concerns over professionalism in the sector.

Figure 2.

Highest (10) term probabilities by topic (STM)

Source: Own elaboration.

In addition to topic-content patterns, we also find that there is a time effect on topic-prevalence (gamma) for pre and post COVID-19 restrictions. As shown in Figure 3, during the latter period, Topic 1 became noticeably more prevalent, peaking at approximately 33 % in November 2020. As indicated in Figure 2, this topic (1) has several defensive elements in which the associations allude to misinformation (e.g., desmentimos-publicamente). In sum, we find evidence that transparency is a concern for the main sectoral business associations (topic 4), despite not being held to the same reporting requirements as direct providers.

Dictionary analysis: identifying the components of the analytical framework[Up]

The second part of our quantitative textual analysis consists of a theory-driven dictionary analysis. As already mentioned, we identify three relevant topics regarding the transparency of service provision (facilities, processes, outcomes) and associate unique keywords to each (see Table 1). The purpose of this approach is to determine to what extent the associations make references to transparency —having found evidence that they do in the topic model above— and what elements of it they focus on when they do. We consider three dimensions of de facto references to transparency. The specific keywords for each dimension can be found in the appendix.

In general, the dictionary analysis found that the process dimension of transparency is the most widely discussed by these actors, and that the topics focused on the structures and policy outcomes are not extensively included in their communication messages. This is in line with expectations, as these associations do not directly manage facilities but simply represent those that do. Nevertheless, the evidence shows that transparency is of concern to these actors and that it remained a key part of their social-media communication strategies both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings notwithstanding, future studies should consider the communication strategies of a more comprehensive corpus of actors in the industry, as well as their variation across regions and types of providers.

CONCLUSIONS[Up]

In this study we examined transparency in nursing home services across Spanish autonomous communities. Since transparency is a relational concept that can cover different types of actors, in their role as information providers or recipients, our research focused on transparency relationships between service providers and beneficiaries. In particular, we examined transparency in two core types of policy-relevant activities: policy-content transparency and the transparency of policy outcomes. In addition, we paid particular attention to the provision of information on three general topics that are crucial for measuring the quality of nursing home services: their structure, processes and results. For each dimension and topic, we identified the specific elements of the transparency of the services.

To do this, we analyzed the formal obligations created by the regional laws of 17 Spanish ACs on the conditions of nursing home facilities. In general, we identified that relevant information about nursing homes is provided through three ways, contracts, bulletin boards, and the publication of public information. From our systematic analysis, we identified that the ACs do not have a standardized pattern to provide information, and that the obligations to provide information to the beneficiaries of the services do not cover all the core topics suggested by the specialized literature on the quality of these services (Donabedian, 1988). For example, the formal provisions have scarce mechanisms for sharing information about service outcomes. In particular about the supervision and control of the service provision. But there are also deficits in the legal stipulations when it comes to sharing information about infrastructures and staff resources (number of medical staff and its training) across regions. In this article, we show that formal stipulations are mainly focused on the provision of information on the processes of the services, but the fulfillment across ACs have a wide variation.

Since 73 % of the services are provided by private providers (profit or non-for-profit), in the second part of our empirical research, we examined the Twitter messages issued by the three biggest business organizations/associations that operate in Spain (FED, AESTE, and CEAPs). Despite not being directly subject to the same reporting requirements as direct service providers, we found evidence that transparency is a concern in the social media communication strategies of these associations. The topic model found that transparency concerns are closely related to professionalization and reliability. This suggests that actors in the sector might use transparency as a way of reacting to external demands, rather than as a core dimension of an active disclosure activity (Grimmelikhuijsen and Welch, 2012); however, further research on a larger corpus of actors would be required to test this assertion.

The topic model and dictionary analysis indicate that, respectively, general and theory-driven transparency concepts of transparency can be found throughout the corpus. Of the three dimensions of transparency identified in the paper (processes, outcomes, and facilities), the three associations pay greater attention to processes. This finding is also in line with the analysis of the formal legislations of ACs, according to which this dimension of policy transparency is more likely to be regulated across regions. Similarly, the transparency-related latent theme uncovered by the topic model suggests that the concept is closely related to professionalization.

The COVID-19 crisis has demonstrated that the governance model and the transparency of these services have failed. Against this backdrop, recent studies (e.g., Thompson, 2020) highlight the need to reform the way in which these services are implemented. This article provides a first step towards systematic research on transparency of the services. Further studies will benefit from the analysis of de facto provision of the information identified. As some studies focused on transparency governance in Spain show (Molina Rodríguez-Navas et al., 2017, 2021) a core challenge is to assess the quality of the information provided to the beneficiaries by measuring core attributes of the information, such as its accessibility and reliability. Further studies are required to determine whether this pattern holds across different actor types (e.g., for profit or non-profit direct providers) and across different regions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS[Up]

This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Innovation, Spain [grant number PID2019-106964RA-I00]. We would also like to thank Laura Chaqués-Bonafont, Ivan Medina and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. We are grateful to Julia García Puig for her assistance in codifying regional legislations.

References[Up]

|

Abellan-García, Antonio, María del Pilar Aceituno Nieto, Diego Ramiro Fariñas and Ana Belén Castillo Belmonte. 2021. Estadísticas sobre residencias: distribución de centros y plazas residenciales por provincia. Datos de septiembre de 2020. Informes Envejecimiento en Red, no 27. Available at: https://cutt.ly/nTboz3z. |

|

|

Bastida, Francisco J. and Bernardino Benito. 2007. “Central government budget practices and transparency: An International Comparison”, Public Administration, 85: 667-716. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2007.00664.x. |

|

|

Benish, Avishai and Paola Mattei. 2020. “Accountability and hybridity in welfare governance”, Public Administration, 98 (2): 281-290. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12640. |

|

|

Birkinshaw, Patrick J. 2006. “Transparency as a Human Right”, in Christopher Hood and David Heald (eds.), Transparency: The Key to Better Governance? Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5871/bacad/9780197 263839.003.0003. |

|

|

Broms, Ramus, Carl Dahlström and Marina Nistotskaya. 2020. “Competition and service quality: Evidence from Swedish residential care homes”, Governance, 33: 525-543. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12436. |

|

|

Cucciniello, Maria and Greta Nasi. 2014. “Transparency for Trust in Government: How Effective Is Formal Transparency?”, International Journal of Public Administration, 37 (13): 911-921. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2014.949754. |

|

|

Chang, Jonathan, Sean Gerrish, Chong Wang, Jordan Boyd-Graber and David Blei. 2009. “Reading Tea Leaves: How Humans Interpret Topic Models”, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 32: 288-296. |

|

|

Chaves-Montero, Alfonso, Fernando Relinque-Medina, Manuela A. Fernández-Borrero and Octavio Vázquez-Aguado. 2021.” Twitter, Social Services and Covid-19: Analysis of Interactions between Political Parties and Citizens”, Sustainability, 13 (4): 2187. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042187. |

|

|

Daly, Mary, Margarita León, Birgit Pfau-Effinger, Costanzo Ranci and Tine Rostgaard. 2021. “COVID-19 and Policies for Care Homes in European Welfare States: Too little, too late?”, Journal of European Social Policy [Forthcoming]. |

|

|

Donabedian, Avedis. 1988. “The quality of care. How can it be assessed?”, Journal of the American Medical Association, 260 (12): 1743-1748. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1988.03410120089033. |

|

|

Ferreira da Cruz, Nuno, António F. Tavares, Rui Cunha Marques, Susana Jorge and Luís de Sousa. 2015. “Measuring Local Government Transparency”, Public Management Review, 18 (6): 866-893. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2015.1051572. |

|

|

Grimmelikhuijsen, Stephen, Gregory Porumbescu, Boram Hong and Tobin Im. 2013. “The Effect of Transparency on Trust in Government: A Cross‐National Comparative Experiment”, Public Administration Review, 73: 575-586. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12047. |

|

|

Grimmelikhuijsen, Stephen and Eric W. Welch. 2012. “Developing and Testing a Theoretical Framework for Computer‐Mediated Transparency of Local Governments”, Public Administration Review, 72: 562-571. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02532.x. |

|

|

Heald, David. 2006. “Varieties of Transparency”, in Christopher Hood and David Heald (eds.), Transparency: The Key to Better Governance? Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5871/bacad/9780197263839.003.0002. |

|

|

Hood, Christopher. 2007. “What happens when transparency meets blame-avoidance?”, Public Management Review, 9 (2): 191-210. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030701340275. |

|

|

León, M., M. Arlotti, D. Palomera, and R. Costanzo. “Trapped in a Blind Spot: The Covid-19 crisis in nursing homes in Italy and Spain”, Social Policy and Society [Forthcoming]. |

|

|

Meijer, Albert J. 2009. “Understanding Computer-Mediated Transparency”, International Review of Administrative Sciences, 75 (2): 255-269. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852309104175. |

|

|

Meijer, Albert J. 2013. “Understanding the Complex Dynamics of Transparency”, Public Administration Review, 73: 429-439. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12032. |

|

|

Molina Rodríguez-Navas, Pedro, Narcisa Medranda Morales and Johamna Muñoz Lalinde. 2021. “Transparency for Participation through the Communication Approach”. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 10 (9): 586. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10090586. |

|

|

Molina Rodríguez-Navas, Pedro, Núria Simelio Solà and Marta Corcoy Rius. 2017. “Methodology for transparency evaluation: procedures and problems”, Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 72: 818-831. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2017-1194en. |

|

|

Moreira, Amílcar, Margarita Léon, Flavia Coda Moscarola and Antonios Roumpakis. 2021. “In the eye of the storm…again! Social policy responses to COVID-19 in Southern Europe”. Social Policy and Administration, 55: 339-357. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12681. |

|

|

Reynaers, Anne M. and Stephan Grimmelikhuijsen. 2015. “Transparency in public-private partnership: Not so bad after all?”, Public Administration, 93: 609-626. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12142. |

|

|

Roberts, Margaret, Brandon M. Stewar, Dustin Tingley, Christopher Lucas, Jetson Leder-Luis, Shana Kushner Gadarian Bethany Albertson and David G. Rand. 2014. “Structural Topic Models for Open-Ended Survey Responses”, American Journal of Political Science, 58: 1064-1082. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12103. |

|

|

Rodríguez Cabrero, Gregorio and Vicente Marbán Gallego. 2013. “Long-Term Care in Spain: Between Family Care Tradition and the Public Recognition of Social Risk”, in Costanzo Ranci and Emmanuele Pavolini (eds.), Long-Term Care Policies in Europe Investigating Institutional Change and Social Impacts. New York: Springer. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4502-9_10. |

|

|

Schoonvelde, Martjin, Denise Traber and Gijs Schumacher. 2020. “Errors have been made, others will be blamed: Issue engagement and blame shifting in prime minister speeches during the economic crisis in Europe”, European Journal of Political Research, 59: 45-67. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12340. |

|

|

Skelcher, Chris and Steven R. Smith. 2014. “Theorizing Hybridity: Institutional Logics, Complex Organizations, and Actor Identities: The Case of Nonprofits”, Public Administration, 93: 433-448. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12105. |

|

|

Thompson, Dana-Claudia, Madalina-Gabriela Barbu, Cristina Beiu, Liliana Gabriela Popa, Mara Madalina Mihai, Mihai Berteanu and Marius Nicolae Popescu. 2020. “The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Long-Term Care Facilities Worldwide: An Overview on International Issues”, BioMed Research International, 7. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8870249. |

|

|

Zalakain, Joseba, Vanessa Davey and Aida Suárez-González. 2020. The COVID-19 on users of Long-Term Care services in Spain. LTCcovid, International Long-Term Care Policy Network, CPEC-LSE. |

APPENDIX 1. LEGAL FRAMEWORK EXAMINED[Up]

Andalusia

-

Decreto 168/2007, de 12 de junio, por el que se regula el procedimiento para el reconocimiento de la situación de dependencia y del derecho a las prestaciones del Sistema para la Autonomía y Atención a la Dependencia. Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía-BOJA, 119, 18-6-2007.

-

Decreto 87/1996, de 20 de febrero, modificado por el Decreto 102/2000, de 15 de marzo, por el que se regula la autorización, registro y acreditación de los Servicios y Centros de Servicios Sociales de Andalucía. Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía, Histórico del BOJA, 39, 28-3-1996.

-

Decreto 183/2003, de 24 de junio, por el que se regula la información y atención al ciudadano y la tramitación de procedimientos administrativos por medios electrónicos (Internet). Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía, Histórico del BOJA, 134, 15-7-2003.

Aragon

-

Decreto Ley 1/2016, de 17 de mayo, sobre acción concertada para la prestación a las personas de servicios de carácter sanitario y social. Boletín Oficial de Aragón, 19-5-2016.

-

Ley 5/2009, de 30 de junio, de Servicios Sociales de Aragón. Boletín Oficial de Aragón, 10-7-2009.

-

Decreto 111/1992, de 26 de mayo, por el que se regulan las condiciones mínimas que han de reunir los servicios y establecimientos sociales especializados. Boletín Oficial de Aragón, 10-6-1992.

Asturias

-

Resolución de 22 de junio de 2009, de la Consejería de Bienestar social y Vivienda, por la que se desarrollan los criterios y condiciones para la acreditación de centros de atención de servicios sociales en el ámbito territorial del Principado de Asturias. Boletín Oficial del Principado de Asturias, 149, 29-6-2009.

-

Decreto 79/2002, de 13 de junio, por el que se aprueba el Reglamento de autorización, registro, acreditación e inspección de centros de atención de servicios sociales. Boletín Oficial del Principado de Asturias, 1-7-2002.

Balearic Islands

-

Decreto 31/2016, de 27 de mayo, de modificación del Decreto 86/2010, de 25 de junio, por el que se establecen los principios generales y las directrices de coordinación para la autorización y la acreditación de los servicios sociales de atención a personas mayores y personas con discapacidades, y se regulan los requisitos de autorización y acreditación de lo servicios residenciales de carácter suprainsular para estos sectores de población. Boletín Oficial de las Islas Baleares, 28-05-2016.

-

Decreto 86/2010, de 25 de junio, por el que se establecen los principios generales y las directrices de coordinación para la autorización y la acreditación de los servicios sociales de atención a personas mayores y personas con discapacidades, y se regulan los requisitos de autorización y acreditación de los servicios residenciales de carácter suprainsular para estos sectores de población. Boletín Oficial de las Islas Baleares, 99, 3-7-2010.

-

Ley 4/2009, de 11 de junio, de servicios sociales de las Illes Balears. Boletín Oficial de las Islas Baleares, 89, 18-6-2009. Boletín Oficial de las Islas Baleares, 163, 7-7-2009.

Basque Country

-

Decreto 126/2019, de 30 de julio, de centros residenciales para personas mayores en el ámbito de la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco. Boletín Oficial del País Vasco, 9-9-2019.

-

Decreto 64/2004, de 6 de abril, por el que se aprueba la carta de derechos y obligaciones de las personas usuarias y profesionales de los servicios sociales en la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco y el régimen de sugerencias y quejas. Boletín Oficial del País Vasco, 76-2139, n.º disposición 64, 23-04-2004

-

Decreto 125/2005, de 31 de mayo, de modificación del Decreto sobre los Servicios Sociales residenciales para la tercera edad, y por Decreto 195/2006, de 10 de octubre, de segunda modificación del Decreto sobre los Servicios Sociales residenciales para la tercera edad. Boletín oficial BOPV, 104-2827, n.º disposición 125, 03-06-2005.

-

Ley 12/2008, de 5 de diciembre, de Servicios Sociales del País Vasco. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 242, 7-10-2011.

-

El Decreto 185/2015, de 6 de octubre, de cartera de prestaciones y servicios del Sistema Vasco de Servicios Sociales, en la ficha del anexo I relativa a los «Centros residenciales para personas mayores» (2.4.1) define el servicio y sus objetivos, las prestaciones que incluye, la delimitación de la población destinataria y la especificación de los restantes requisitos de acceso, estableciendo que está sujeto a copago. Boletín Oficial del País Vasco, 206-4561, n.º disposición 185, 29-10-2015.

Canary Islands

-

Decreto 154/2015, de 18 de junio, por el que se modifica el Reglamento regulador de los centros y servicios que actúen en el ámbito de la promoción de la autonomía personal y la atención a personas en situación de dependencia en Canarias, aprobado por el Decreto 67/2012, de 20 de julio. Boletín Oficial de Canarias, 128, 3-7-2015, 3117.

-

Decreto 67/2012, de 20 de julio, por el que se aprueba el Reglamento regulador de los centros y servicios que actúen en el ámbito de la promoción de la autonomía personal y la atención a personas en situación de dependencia en Canarias. Boletín Oficial de Canarias, 158, 13-7-2012, 4140.

-

Orden de 3 de junio de 2004, por la que se aprueba el Reglamento de régimen interno de los centros de día de atención social a personas mayores cuya titularidad ostente la Administración pública de la Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias. Boletín Oficial de Canarias, 113, 14-6-2004, 933.

-

Decreto 63/2000, de 25 de abril, por el que se regula la ordenación, autorización, registro, inspección y régimen de infracciones y sanciones de centros para personas mayores y sus normas de régimen interno. Boletín Oficial de Canarias, 62, 19-5-2000.

Cantabria

-

Orden UMA/12/2019, de 14 de marzo, por la que se establecen los criterios y se regula el procedimiento para la acreditación de centros de servicios sociales destinados a la atención a personas en situación de dependencia.

-

Ley de Cantabria 2/2007 de Derechos y Servicios Sociales (actualizada a 1-1-2019). Boletín Oficial de Cantabria, 66, 3-4-2007.

-

Decreto 40/08, de 17 de abril, por el que se regulan la autorización, la acreditación, el registro y la inspección de entidades, servicios y centros de servicios sociales de la Comunidad Autónoma de Cantabria. Boletín Oficial de Cantabria, 29-4-2008, 83.

Castile-La Mancha

-

Orden de 04/06/2013, de la Consejería de Sanidad y Asuntos Sociales, por la que se modifica la Orden de 21/05/2001, de la Consejería de Bienestar Social, por la que se regulan las condiciones mínimas de los centros destinados a las personas mayores en Castilla-La Mancha (2013/7109). Diario Oficial de Castilla-La Mancha, 112, 12-6-2013.

-

Ley 14/2010, de 16 de diciembre, de servicios sociales de Castilla-La Mancha. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 38, 14-2-2011.

Castile Leon

-

Ley 16/2010, de 20 de diciembre, de Servicios Sociales de Castilla y León. Boletín Oficial del Estado, A-2011-40.

-

Ley 5/2003, de 3 de abril, de Atención y Protección a las Personas Mayores de Castilla y León.

-

Boletín Oficial del Estado, A-2003-9100.

-

Decreto 14/2001, de 18 de enero regulador de las condiciones de las condiciones y requisitos para la autorización y el funcionamiento de los centros de carácter social para las personas mayores. Boletín Ofcial de Castilla y León, 17, 24-1-2001.

Catalonia

-

Decreto 205/2015, de 15 de septiembre, del régimen de autorización administrativa y de comunicación previa de los servicios sociales y del Registro de Entidades, Servicios y Establecimientos Sociales. Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya, 6958, 17-9-2015.

-

Ley 12/2007, de 11 de octubre, de Servicios Sociales. Comunidad Autónoma de Cataluña. Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya, 4990, 18-10-2007. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 266, 6-11-2007, A-2007-19189.

Extremadura

-

Decreto 298/2015, de 20 de noviembre, por el que se aprueba el reglamento de autorización, acreditación y registro de centros de atención a personas mayores de la comunidad autónoma de Extremadura. Diario Oficial de Extremadura, 228, 26-11-2015.

-

Decreto 83/2000, de 4 de abril, por el que se regula el estatuto de los centros de mayores de la Consejería de Bienestar Social de la Comunidad Autónoma de Extremadura. Diario Oficial de Extremadura, 42, 11-4-2000.

Galicia

-

Orden de 12 de enero de 2021 por la que se regula la presentación y la comunicación de las reclamaciones en materia de servicios sociales (códigos de procedimiento BS105A y BS105B).

-

Ley 13/2008, de 3 de diciembre, de servicios sociales de Galicia. Diario Oficial de Galicia, 245, 18-12- 2008. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 15, de 17-1-2009. A-2009-807.

-

Orden de 13 de abril de 2007 por la que se modifica la de 18 de abril de 1996 por la que se desarrolla el Decreto 243/1995, de 28 de julio, en lo relativo a la regulación de las condiciones y requisitos específicos que deben cumplir los centros de atención a personas mayores.

La Rioja

-

Ley 1/2002, de 1 de marzo, de Servicios Sociales. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 79, 2-4-2002.

-

Decreto 27/1998, de 6 de marzo, por el que se regulan las categorías y requisitos específicos de los centros residenciales de personas mayores en La Rioja. Boletín Oficial de La Rioja, 29, 7-3-1998.

Madrid

-

Ley 11/2002, de 18 de diciembre, de Ordenación de la Actividad de los Centros y Servicios de Acción Social y de Mejora de la Calidad en la Prestación de los Servicios Sociales de la Comunidad de Madrid. Boletín Oficial de la Comunidad de Madrid, 304, 23-12-2002.

-

Decreto 72/2001, de 31 de mayo, por el que se regula el Régimen Jurídico Básico del Servicio Público de Atención a Personas Mayores en Residencias, Centros de Atención de Día y Pisos Tutelados.

-

Orden 766/1993, de 10 de junio, de la Consejería de Integración Social, por la que se aprueba el Reglamento de Organización y Funcionamiento de las Residencias de Ancianos que gestiona directamente el Servicio Regional de Bienestar Social.

Murcia

-

Ley 3/2003 del 10 de abril, del Sistema de Servicios Sociales de la Región de Murcia. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 35, 10-2-2004

-

Decreto 54/ 2001, de 15 de junio, de autorizaciones, organización y funcionamiento del registro de entidades, centros y servicios sociales de la Región de Murcia y de la Inspección.

-

Decreto 69/2005, de 3 de junio, por el que se establecen las condiciones mínimas que han de reunir los centros residenciales para personas mayores de titularidad pública o privada.

Navarra

-

Ley Foral 15/2006, de 14 de diciembre, de Servicios Sociales. Boletín Oficial de Navarra, 152, 20-12-2006.

-

Decreto Foral 92/2020, de 2 de diciembre, por el que se regula el funcionamiento de los servicios residenciales, de día y ambulatorios de las áreas de mayores, discapacidad, enfermedad mental e inclusión social, del sistema de servicios sociales de la Comunidad Foral de Navarra, y el régimen de autorizaciones, comunicaciones previas y homologaciones.

Valencia

-

Orden del 4 de febrero de 2005, de la Conselleria de Bienestar Social, por la que se regula el régimen de autorización y funcionamiento de los centros de servicios sociales especializados para la atención de personas mayores (2005/1376). Modificada por la Orden 8/2012, de 20 de febrero, de la Conselleria de Justicia y Bienestar Social, por la que se modifica la Orden de 4 de febrero de 2005, de la Conselleria de Bienestar Social, por la que se regula el régimen de autorización y funcionamiento de centros de servicios sociales especializados para la atención de personas mayores. Diario Oficial de la Generalitat Valenciana, 6728, 6-3-2012.

-

Decreto 91/2002, de 30 de mayo, del Gobierno Valenciano, sobre registro de los titulares de actividades de acción social, y de registro y autorización de funcionamiento de los servicios y centros de acción social, en la Comunidad Valenciana (2002/X5931).

APPENDIX 2. QUANTITATIVE TEXT ANALYSIS[Up]

| Dictionary Keywords (Spanish/English) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processes | Outcomes | Facilities | |||

| staff | staff | servicios | services | resultados | results |

| ratios | ratios | prestaciones | benefits | innovación | innovation |

| infraestructuras | infrastructure | contrato | contract | eficiencia | efficiency |

| cualificaciones | qualifications | cuidado | care | equidad | equity |

| instalaciones | installations | horarios | schedules | igualdad | equality |

| recursos humanos | human resources | comida | food | mortalidad | mortality |

| personal | personnel | menús | menus | úlceras | ulcers |

| organigrama | organization chart | privacidad | privacy | calidad | quality |

| titularidad | ownership | actividades | activities | satisfacción | satisfaction |

| ejercicio | exercise | usuarios | users | ||

| actividades sociales | social activities | ||||

| participación | participation | ||||

| dirección | direction | ||||

Biography[Up]

| [a] |

Assistant professor (Serra-Húnter Fellow) at the Department of Political Science and Public Law, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Her research interests include regulation, governance, accountability, EU agencies, and national regulatory agencies. Her work has been published in the Journal of European Public Policy, Regulation and Governance, West European Politics, European Political Science Review, Journal of European Integration, and International Review of Administrative Sciences. |

| [b] |

Teaching fellow at the Barcelona Institute of International Studies (IBEI). His research interests include computational social sciences, quantitative text analysis and international political economy. His work has been published in volumes by Springer, Emerald, and Hart among others. |