Dual voting and second-order effects in the quasi-simultaneous 2019 Spanish regional and national elections

Voto dual y efectos de segundo orden en las elecciones autonómicas y generales cuasi simultáneas de 2019 en España

ABSTRACT

The 2019 regional elections in Spain were held in a context of political instability and polarization in the country and just 28 days after the national elections. Taking advantage of this unprecedented quasi-simultaneous electoral setting, this article analyzes vote-switching between regional and national elections, both at the aggregate and individual levels. Specifically, it explores whether the 2019 regional elections match the expectations of the second-order election model. The results show that quasi-simultaneity between regional and national elections did not entail a higher level of election congruence. In addition, while most of the predictions of the second-order election model regarding aggregate election results hold for the 2019 regional elections, our findings suggest that dual voting at the individual level does not respond to the logic of the second-order election model but rather to regional political considerations.

Keywords: regional elections, second-order elections, electoral cycle, dual voting, Spain.

RESUMEN

Las elecciones autonómicas de 2019 en España se celebraron en un contexto de inestabilidad política y polarización en el país y apenas veintiocho días después de las elecciones generales. Aprovechando este escenario electoral cuasi simultáneo y sin precedentes, este artículo analiza el cambio de voto entre elecciones autonómicas y generales, tanto a nivel agregado como individual. Específicamente, el artículo explora si las elecciones regionales de 2019 cumplen con las expectativas del modelo de elecciones de segundo orden. Los resultados muestran que la cuasi simultaneidad entre las elecciones autonómicas y generales no implicó un mayor nivel de congruencia electoral. Además, si bien la mayoría de las predicciones del modelo de elecciones de segundo orden respecto a los resultados electorales agregados son válidas para las elecciones autonómicas de 2019, nuestros hallazgos sugieren que el voto dual a nivel individual no responde a la lógica del modelo de elecciones de segundo orden, sino más bien a consideraciones políticas regionales.

Palabras clave: elecciones regionales, elecciones de segundo orden, ciclo electoral, voto dual, España.

CONTENTS

- ABSTRACT

- RESUMEN

- INTRODUCTION

- THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: SECOND-ORDER ELECTION EFFECTS IN A QUASI-SIMULTANEOUS ELECTORAL SETTING

- REGIONAL GOVERNMENT AND REGIONAL ELECTIONS IN SPAIN

- AN AGGREGATE-LEVEL ANALYSIS: CONGRUENCE OF THE VOTE AND SECOND-ORDER EFFECTS

- AN INDIVIDUAL-LEVEL ANALYSIS: DUAL VOTING IN THE 2019 REGIONAL AND NATIONAL ELECTIONS

- DISCUSSION

- NOTES

- REFERENCES

INTRODUCTION[Up]

The 2019 Spanish regional elections were held on Sunday May 26th, in twelve out of the seventeen autonomous communities that make up Spain[1], on the same day as the local and the European elections. They took place against

the backdrop of a fragmented and unstable political landscape in the country, and

barely one month after a snap general election held on April 28th. This is the first

time that regional elections have happened so soon after the national poll in Spain,

just 28 days later. In the literature, it is well established that the timing of regional

elections in the national political cycle matters: regional voting patterns tend to

deviate less from voting patterns in national elections when regional and national

elections are held simultaneously (Jeffery, Charlie and Dan Hough. 2006. “Devolution and Electoral Politics: Where Does

the UK Fit In?”, in Dan Hough and Charlie Jeffery (eds.), Devolution and Electoral Politics. Manchester: Manchester University Press.Jeffery and Hough, 2006) or close in time (Schakel, Arjan H. 2013. “Congruence Between Regional and National Elections”, Comparative Political Studies, 46 (5): 631-662. Available at:

This article analyzes the degree to which the 2019 Spanish regional elections may

be considered second-order contests by analyzing vote-switching between national and

regional elections at both the aggregate and individual levels. Specifically, it first

focuses on the degree of (dis)similarity between regional and national election results,

and then explores why people voted differently in the quasi-simultaneous 2019 regional

and national elections. We argue that voters that split their ticket between the regional

and the national elections are susceptible to be classified into two groups: (1) those

who chose to support different parties because they consider that the two arenas are

independent and (2) those who treat regional elections as second-order elections (Liñeira, Robert. 2011. “‘Less at Stake’ or a Different Game? Regional Elections in

Catalonia and Scotland”, Regional and Federal Studies, 21 (3): 283-303. Available at:

We contribute to the literature in two ways. First, while most empirical studies of

the second-order model draw upon the use of aggregate data such as election results,

we rely on individual-level data to complement the aggregate-level analysis. Second,

previous research has tended to use congruence of the vote between national and regional

elections as an indicator of the “nationalization” of regional elections (Pallarés, Francesc and Michael Keating. 2003. “Multi-Level Electoral Competition.

Regional Elections and Party Systems in Spain”, European Urban and Regional Studies, 10 (3): 239-255. Available at:

The remaining of this article proceeds as follows. Section 2 introduces the theoretical framework. Section 3 describes the main characteristics of the Spanish regional governments and the context under which the 2019 regional elections were held. Section 4 provides an aggregate-level analysis of congruence between the 2019 national and regional elections and identifies patterns of second-order voting. Section 5 moves forward to an individual-level analysis of dual voting. Section 6 concludes with a discussion of the results.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: SECOND-ORDER ELECTION EFFECTS IN A QUASI-SIMULTANEOUS ELECTORAL SETTING[Up]

The nationalization of regional elections is a possible consequence of the temporal

proximity between regional and national elections. Regional elections may be more

influenced by —and more subordinate to— national politics when they are held simultaneously

or close to the general election (Jeffery, Charlie and Dan Hough. 2006. “Devolution and Electoral Politics: Where Does

the UK Fit In?”, in Dan Hough and Charlie Jeffery (eds.), Devolution and Electoral Politics. Manchester: Manchester University Press.Jeffery and Hough, 2006; Schakel, Arjan H. 2013. “Congruence Between Regional and National Elections”, Comparative Political Studies, 46 (5): 631-662. Available at:

The second-order election model, the dominant approach in the study of regional elections,

makes three general predictions about election results (Reif, Karlheinz and Hermann Schmitt. 1980. “Nine Second-Order National Elections.

A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results”, European Journal of Political Research, 8 (1): 3-44. Available at:

Yet, when national and regional elections occur within a few weeks some of these regularities

may become more or less pronounced. At the aggregate level, and following the first

prediction of the second-order election model, we expect to find lower levels of voter turnout in the 2019 regional elections compared

to the national one. In this case, the close temporal proximity with national elections may accentuate

this specific second-order election effect. When voters are required to vote too often,

they could experience fatigue and participation may decline further (Schakel and Dandoy,

2014; Garmann, Sebastian. 2017. “Election Frequency, Choice Fatigue, and Voter Turnout”,

European Journal of Political Economy, 47: 19-35. Available at:

REGIONAL GOVERNMENT AND REGIONAL ELECTIONS IN SPAIN[Up]

For much of its recent history, Spain has been a hyper-centralized state, where territorial

diversity was not recognized. The decentralization process began with the transition

to democracy after four decades of dictatorship and the proclamation of the Constitution

in 1978, which ensured “the right to autonomy of the nationalities and regions” that

make up the country (Art. 2). In a relatively short period of time, Spain became a

highly decentralized country to the extent of being widely considered a “federation

in all but name” (Elazar, Daniel J. (ed.). 1991. Federal Systems of the World: A Handbook of Federal, Confederal and Autonomy Arrangements.

Harlow: Longman Group UK Limited.Elazar, 1991: 227; Hueglin, Thomas O., and Alan Fenna. 2015. Comparative Federalism: A Systematic Inquiry. 2nd edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.Hueglin and Fenna, 2015: 9). Today, Spain is made up of seventeen regions called Autonomous Communities. Although

asymmetry has been a persistent element in the development of the Spanish Statute

of Autonomies, nowadays all regions enjoy a considerable degree of autonomy (Novo, Ainhoa, Sergio Pérez and Jonatan Garcia. 2019. “Building a Federal State: Phases

and Moments of Spanish Regional (de)Centralization”, Italian Political Science Review / Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica, 49 (3): 263-277. Available at:

Regional parliaments vary in size from 33 members in La Rioja to 135 members in Catalonia.

The number of parties that make it to the regional parliaments also varies greatly

between regions (Gómez, Braulio, Sonia Alonso and Laura Cabeza. 2019a. Regional Manifestos Project Dataset (Version 11/2019). Available at:

Figure 1.

Average number of parties that have entered regional parliaments

Note: Average in the regions that hold elections on the same day.

Source: Own elaboration with data from Archivo histórico electoral, Argos.

The 2019 regional elections, which are the focus of this article, are characterized

by both horizontal simultaneity (twelve regions went to the polls) and vertical simultaneity

with other second-order elections (they were held on the same day as the local elections,

as well as the elections to the European Parliament). Indeed, because of that concurrence

of elections on the same date, many have labelled the election day as a “Super Sunday”[3]. Both vertical and horizontal simultaneity may have significant implications for

election results. On the one hand, turnout tends to increase when regional elections

are held concurrently with other elections (Schakel, Arjan H. and Régis Dandoy. 2014. “Electoral Cycles and Turnout in Multilevel

Electoral Systems”, West European Politics, 37 (3): 605-623. Available at:

AN AGGREGATE-LEVEL ANALYSIS: CONGRUENCE OF THE VOTE AND SECOND-ORDER EFFECTS[Up]

Election congruence[Up]

According to previous research, vertical and horizontal simultaneity increases the

level of congruence between regional and national election results (Schakel, Arjan H. 2013. “Congruence Between Regional and National Elections”, Comparative Political Studies, 46 (5): 631-662. Available at:

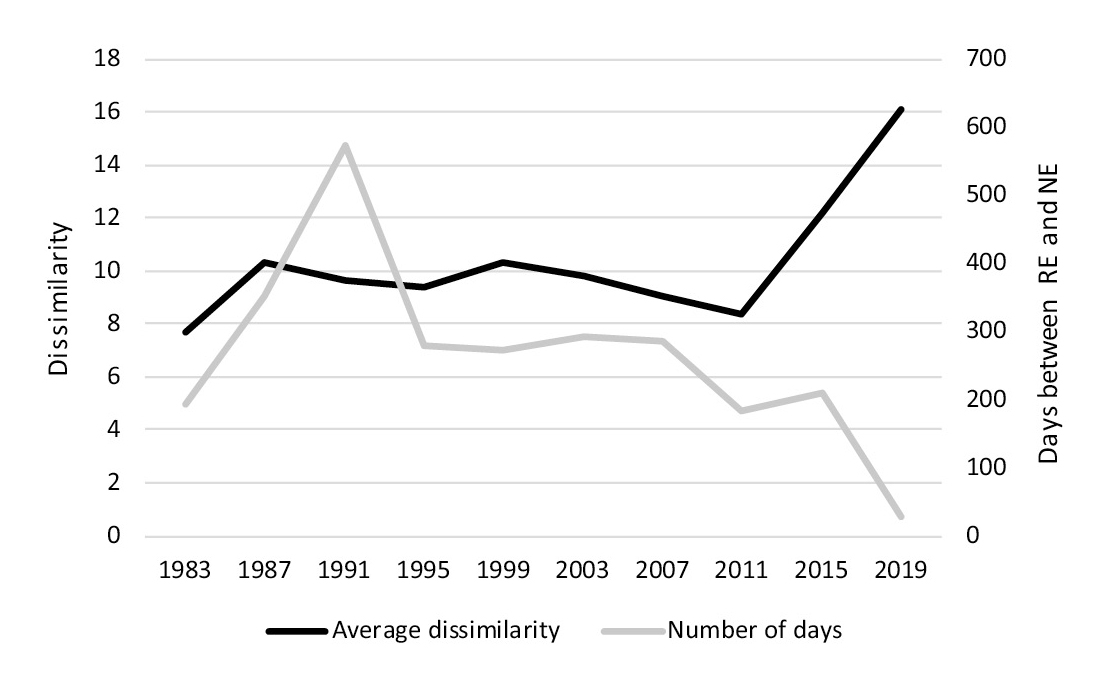

where iN stands for the percentage of the vote won by party i in the national election N and iR stands for the percentage of the vote won by party i in the closest regional election R. Scores may vary from 0 per cent, indicating complete congruence or similarity (i.e. nationalization), to 100 per cent, indicating complete incongruence or dissimilarity (i.e. regionalization). While the index allows different types of analytical combinations with respect to the type of election (national or regional) in conjunction with the territorial unit of analysis (national or regional), what matters for our analysis is the comparison between the national and the regional vote in a given region. Such a combination keeps the regional electorate constant but varies the type of election so that the effects of dual voting are incorporated.

Figure 2 represents the average dissimilarity and number of days between regional and national elections since 1983, when the first round of regional elections took place in the Spanish ordinary regions. Against the predictions of the literature, the temporal proximity to the national elections did not translate to an increase in election congruence in the 2019 regional elections in Spain. Indeed, it is precisely in 2019, when the time that elapsed between the national and regional elections is the shortest, where we can observe the highest score on the dissimilarity index. According to the data in Figure 2, in the case of Spain, the level of election congruence does not seem to depend at all on the proximity or distance between regional and national elections. In fact, dissimilarity has remained virtually constant between 1983 and 2011, despite the variation in the number of days elapsed between national and regional elections.

Figure 2.

Average dissimilarity and number of days between regional and national election (1983-2019)

Note: Dissimilarity is measured by an index that ranges from 0 per cent (complete congruence/similarity) to 100 per cent (complete incongruence/dissimilarity). Average in the regions that hold regional elections on the same day.

Source: Own elaboration with data from Archivo histórico electoral, Argos.

Figure 3 reports the dissimilarity index in 2019 by region, showing a high level of

cross-regional variation in election congruence. This variation is mainly due to the

presence and strength of regionalist parties. Regionalist parties are those whose

political program is the defense of a distinctive territory within the state; they

are all rooted in the center-periphery cleavage and organize exclusively in their

peripheral territory (Alonso, Sonia, Laura Cabeza and Braulio Gómez. 2017. “Disentangling Peripheral Parties’

Issue Packages in Subnational Elections”, Comparative European Politics, 15 (2): 240-263. Available at:

Figure 3.

Dissimilarity between regional and national election results by region (2019)

Note: Dissimilarity is measured by an index that ranges from 0 per cent (complete congruence/similarity) to 100 per cent (complete incongruence/dissimilarity).

Source: Own elaboration with data from Archivo histórico electoral, Argos.

The level of congruence between national and regional election results not only depends on the presence and strength of regionalist parties. Conjunctural or region-specific factors also play a role. For instance, Madrid is among the regions with the highest dissimilarity index in 2019 (see Figure 3) but there are no regionalist parties as such. The high score on the dissimilarity index in this case is due to the emergence of the new political platform Más Madrid, which did not participate in the April 2019 national election. On the contrary, despite the presence of relevant regionalist parties, Aragon stands out for its very low score on the dissimilarity index. The low dissimilarity score in Aragon can be explained by the idiosyncrasy of this region. According to Spanish political scientists, Aragon is the “Spanish Ohio” (Fernández Albertos, Joséet al. 2015. Aragon es nuestro Ohio. Así votan los españoles. Barcelona: Malpaso Editorial.Fernández Albertos et al., 2015). Similarly to what happens in United States with the midwestern “swing state”, the first party in Aragon has always been the first party in Spain. Like Ohio, which contains a bit of everything American, Aragon is a kind of Spain in miniature: it combines a large urban center with large rural areas, it has a very similar party system characterized by the presence of mainstream parties and both center-left and center-right regionalist parties, and even reproduces regionalist parties’ weight at national level.

Be that as it may, to look exclusively at differences or similarities between national

and regional vote shares is not enough to determine whether regional elections are

nationalized or not (Schakel, Arjan H. 2013. “Congruence Between Regional and National Elections”, Comparative Political Studies, 46 (5): 631-662. Available at:

Second-order effects[Up]

The first prediction of the second-order election model refers to voter turnout, which

tends to be consistently lower in regional than in national elections (Henderson, Ailsa and Nicola McEwen. 2010. “A Comparative Analysis of Voter Turnout

in Regional Elections”, Electoral Studies, Special Symposium: Voters and Coalition Governments, 29 (3): 405-16. Available at:

The second prediction of the second-order election model is that national government

parties tend to lose votes at mid-term, while they may enjoy a short “honeymoon period”

if the second-order election takes place immediately after their electoral success

at the national election (Dinkel, Reiner. 1977. “Der Zusammenhang zwischen Bundes- und Landtagswahlergebnissen”,

Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 18 (2/3): 348-359.Dinkel, 1977; Hix, Simon and Michael Marsh. 2007. “Punishment or Protest? Understanding European

Parliament Elections”, Journal of Politics, 69 (2): 495-510. Available at:

Table 1.

Results of the 2019 national and regional elections

| Turnout | PSOE | PP | Podemos | C’s | Vox | Regional[*] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NE | RE | NE | RE | NE | RE | NE | RE | NE | RE | NE | RE | NE | RE | |

| Aragon | 75.2 | 66.2 | 32 | 31.1 | 19.1 | 21.1 | 13.7 | 8.2 | 20.7 | 16.8 | 12.3 | 6.1 | 11.4 | |

| Asturias | 65.0 | 55.1 | 33.5 | 35.6 | 18.1 | 17.7 | 17.3 | 11.2 | 16.9 | 14.1 | 11.6 | 6.5 | 6.6 | |

| Balearic Is. | 65.4 | 53.9 | 26.6 | 28.1 | 17.0 | 22.8 | 18.0 | 9.8 | 17.6 | 10.0 | 11.4 | 8.2 | 7.2 | 18.1 |

| Canary Is. | 62.5 | 52.5 | 28.0 | 29.6 | 15.6 | 15.1 | 15.8 | 8.8 | 14.8 | 7.2 | 6.6 | 2.5 | 16.5 | 32.2 |

| Cantabria | 72.4 | 65.7 | 25.4 | 17.8 | 21.8 | 24.3 | 10.3 | 3.2 | 15.2 | 8.0 | 11.2 | 5.1 | 14.6 | 38 |

| C.-La Man. | 76.6 | 68.0 | 32.6 | 44.5 | 22.8 | 28.8 | 10.2 | 7.0 | 17.6 | 11.5 | 15.4 | 7.1 | ||

| C. and Leon | 72.9 | 65.8 | 30.1 | 35.2 | 26.3 | 31.8 | 10.5 | 5.1 | 19.1 | 15.1 | 12.4 | 5.6 | 2.1 | |

| Extremadura | 74.2 | 69.3 | 38.4 | 47.2 | 21.5 | 27.7 | 9.6 | 7.3 | 18.1 | 11.2 | 10.9 | 4.8 | ||

| La Rioja | 73.4 | 65.9 | 31.9 | 39.0 | 26.7 | 33.4 | 11.9 | 6.7 | 17.9 | 11.6 | 9.1 | 3.9 | 1.2 | 4.7 |

| Madrid | 75.5 | 64.3 | 27.5 | 27.4 | 18.8 | 22.3 | 16.3 | 5.6 | 21.1 | 19.5 | 13.9 | 8.9 | 14.8 | |

| Murcia | 73.5 | 64.1 | 24.9 | 32.6 | 23.6 | 32.5 | 10.5 | 5.6 | 19.7 | 12.1 | 18.7 | 9.5 | ||

| Navarre | 72.5 | 72.2 | 26.0 | 20.8 | 29.6 | 36.9 | 18.8 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 1.3 | 19 | 32.2 | ||

| Mean | 71.6 | 63.6 | 29.7 | 32.4 | 21.7 | 26.2 | 13.6 | 6.9 | 18.1 | 12.5 | 11.5 | 5.8 | 11.7 | 17.8 |

| Difference | -8.0 | 2.7 | 4.5 | -6.6 | -5.6 | -5.7 | 6.1 | |||||||

| [*] |

Aragon: PAR, CHA; Asturias: Foro; Balearic Islands: MES, El Pi; Canary Islands: CC, NC; Cantabria: PRC; Castile and Leon: UPL; La Rioja: PR; Madrid: Más Madrid; Navarre: GeBai, EHBildu. |

Finally, the third prediction of the second-order election model is that, compared

to traditional opposition parties, small and new political parties have brighter electoral

prospects in second-order elections (Reif, Karlheinz and Hermann Schmitt. 1980. “Nine Second-Order National Elections.

A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results”, European Journal of Political Research, 8 (1): 3-44. Available at:

One plausible explanation for the poor performance of Vox in the 2019 regional elections

is linked to the party position on the center-periphery cleavage, which is central

to the party’s strategy. Paradoxically, Vox participated in the regional elections

with the programmatic goal of abolishing regional autonomy and regional parliaments,

as stated in its manifesto[5]. It comes as no surprise that 16.1 per cent of the quasi-sentences of the regional

election manifesto of Vox are dedicated to the center-periphery dimension, advocating

for recentralization (Gómez, Braulio, Laura Cabeza and Sonia Alonso. 2019b. En busca del poder territorial: cuatro décadas de elecciones autonómicas en España.

Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.Gómez et al., 2019b). What is more surprising is that issues such as immigration are not even mentioned.

There is only one quasi-sentence in Vox’s entire regional manifesto against teaching

Islam in public schools. Unlike most of the right-wing populist parties in Western

Europe, the rise of Vox does not seem to be based on the party’s ability to capitalize

on anti-immigrant sentiments or disenchantment among the “losers of globalization”.

On the contrary, Vox draws its support mainly from the wealthiest areas of Spain (Galaup, Laura and Raúl Sánchez. 2019. “La extrema derecha española no capta voto obrero:

Vox despunta en los barrios ricos de las grandes ciudades”. elDiario.es, June 10, 2019. Available at:

Moreover, as recent research has shown, neither voters’ political distrust nor concerns

about immigration have played a role in explaining the electoral success of Vox (Turnbull-Dugarte, Stuart J. 2019. “Explaining the End of Spanish Exceptionalism and

Electoral Support for Vox”, Research and Politics, 6 (2): Online first. Available at:

AN INDIVIDUAL-LEVEL ANALYSIS: DUAL VOTING IN THE 2019 REGIONAL AND NATIONAL ELECTIONS[Up]

Analysis based on aggregate election results are useful to quantify the overall differences between regional and national vote shares. However, only survey data can provide evidence on the real amount and the specific direction of vote-switching at the individual-level. This section uses data from the post-election survey conducted by the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS) after the 2019 Spanish regional and local elections (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS). 2019. Estudio 3253 Postelectoral elecciones autonómicas y municipales 2019. Madrid.CIS, 2019). Although the main focus of this survey is on voting behavior at the regional and local elections, respondents were also asked about their vote choice in the April 2019 national election. This allows us to identify the transition between the national and the regional vote for each individual.

According to these data, a large proportion of the electorate voted the same way in

the 2019 Spanish national and regional elections. Yet, those who vote differently

represent a 23.7 per cent. This is not a negligible amount especially if we consider

two things: (1) the short time lapse between the two elections, and (2) the fact that

we are analyzing only the ordinary Spanish regions, not the “historic” nations such

as Catalonia, the Basque Country and Galicia. In any case, what is relevant to our

purpose is to examine whether dual voting respond to the prevalence of a second-order

election logic or not. Voters that split their ticket between the regional and the

national elections are susceptible to be classified into two groups: those who change

their vote because they treat regional elections as second-order elections and those

who vote for different parties at different levels because they consider that both

arenas are independent (Railings, Colin and Michael Thrasher. 1998. “Split‐ticket Voting at the 1997 British

General and Local Elections: An Aggregate Analysis”, British Elections and Parties Review, 8 (1): 111-134. Available at:

Concerning the second group, labelled as No SOE transitions, we include electoral transitions that deviate from second-order expectations. To this

group of voters pertain those who switched from a state-wide party in the national

election to a regionalist party in the regional election. Extensive research has been

conducted in Spain analyzing this kind of vote transition, mainly focusing on the

Catalan case (Font, Joan. 1991. “El voto dual en Cataluña: lealtad y transferencia de votos en las

elecciones autonómicas”, Revista de Estudios Políticos, 73: 7-34.Font, 1991; Riba, Clara. 2000. “Voto dual y abstención diferencial. Un estudio sobre el comportamiento

electoral en Cataluña”, Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 91: 59-88. Available at:

Table 2.

Vote transitions from National to Regional Elections

| SOE transitions | |

|---|---|

| From voting to abstention | 23,8 |

| From a mainstream party to a new party | 14,1 |

| No SOE transitions | |

| From a mainstream or new party to a regionalist party | 29,6 |

| From a new party to a mainstream party | 18,3 |

| From abstention to voting | 7,3 |

| Two different mainstream or two different new parties | 6,9 |

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 2 focuses on the people that voted differently and shows the direction of vote change

between national and regional elections. The vote transitions that we have theoretically

defined as No SOE transitions (62.1 per cent) are more frequent than those that we have considered as SOE transitions (37.9 per cent). Indeed, many individuals casting their votes for different parties

switched from a state-wide party (either mainstream or new) in the national election

to a regionalist party in the regional election. This is clearly the most frequent

form of dual voting (29.6 per cent), and the most well documented by previous research

on the Spanish case (Font, Joan. 1991. “El voto dual en Cataluña: lealtad y transferencia de votos en las

elecciones autonómicas”, Revista de Estudios Políticos, 73: 7-34.Font, 1991; Riba, Clara. 2000. “Voto dual y abstención diferencial. Un estudio sobre el comportamiento

electoral en Cataluña”, Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 91: 59-88. Available at:

Why people vote differently between the 2019 Spanish regional and national elections? Which factors drive SOE and no SOE voting transitions? In order to answer these questions, we proceed to a multivariate analysis. The dependent variable takes on three values: No vote change (when the individual voted for the same party or opted for abstention in both the 2019 regional and national elections), SOE transitions and No SOE transitions. We use multinomial logistic regression and set No vote change as the baseline group to which the other two outcomes are compared. Standard errors are clustered at the regional level to account for potential correlation of individuals within each region.

We consider in our analysis the three fundamental factors that previous research has

shown to be the main predictors of dual voting: national identity, assessments of

national government or leaders, and assessments of regional government or leaders

(Fraile, Marta and Santiago Pérez-Nievas. 2000. Is the Nationalist Vote Really Nationalist? Dual Voting in Catalonia 1980-1999. Estudio/Working Paper, 2000/147. Madrid: Instituto Juan March.Fraile and Pérez-Nievas, 2000; Liñeira, Robert. 2011. “‘Less at Stake’ or a Different Game? Regional Elections in

Catalonia and Scotland”, Regional and Federal Studies, 21 (3): 283-303. Available at:

Unfortunately, the CIS survey does not contemplate the evaluation of the national government in the questionnaire; but we account for the influence of the national arena by including in our model the evaluation of Pedro Sánchez, who was the Spanish Prime Minister when the 2019 regional elections were held. It is measured by a continuous variable with 10 points, where 1 stands for very bad and 10 for very good. In order to assess the effect of regional assessments, we include in our model the evaluation of the regional government. The original variable is categorical and ranges from 1 (very good) to 5 (very bad). To facilitate interpretation, we have inverted the order of the scale and grouped the responses into three categories: (1) bad, (2) regular and (3) good. The CIS survey does not ask for the evaluation of regional leaders. As control variables, we include interest in the regional election campaign, level of education and ideology, all of them as categorical variables. Table 3 shows the results of the multinomial logistic regression.

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression (Base category: No Vote Change)

| SOE Transitions | No SOE Transitions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Robust S.E. | Coef. | Robust S.E. | |

| National Identity (reference category: Equally) | ||||

| Only Spanish | 0.315[*] | 0.189 | 0.030 | 0.122 |

| More Spanish | -0.444 | 0.303 | -0.250 | 0.240 |

| More [regional demonym] | 0.269 | 0.205 | 0.385 | 0.264 |

| Only [regional demonym] | -0.029 | 0.428 | 0.641[**] | 0.308 |

| Evaluation Spanish Prime Minister | 0.039 | 0.044 | -0.026 | 0.050 |

| Retrospective Evaluation Regional Government (reference category: Neutral) | ||||

| Bad | 0.084 | 0.092 | -0.090 | 0.223 |

| Good | -0.387[***] | 0.127 | 0.225[*] | 0.122 |

| Interest Regional Election Campaign (reference category: Not at all) | ||||

| Not very interested | -0.165 | 0.151 | 0.176 | 0.139 |

| Somewhat interested | -0.384[*] | 0.190 | 0.447[**] | 0.209 |

| Very interested | -0.745[**] | 0.244 | 0.178 | 0.230 |

| Education (reference category: No formal education) | ||||

| Primary | 0.500 | 0.603 | -0.343 | 0.440 |

| Secondary | 0.804 | 0.496 | 0.571 | 0.386 |

| Higher | 1.343[***] | 0.453 | 0.948[**] | 0.447 |

| Ideology (reference category: Centre) | ||||

| Left | -0.263 | 0.252 | -0.178 | 0.331 |

| Centre-left | -0.466[**] | 0.183 | -0.265 | 0.265 |

| Centre-right | -0.076 | 0.136 | -0.057 | 0.116 |

| Right | 0.109 | 0.169 | -0.347[**] | 0.149 |

| Undeclared | -0.113 | 0.244 | -0.322[**] | 0.153 |

| Constant | -2.705[***] | 0.459 | -2.275[***] | 0.536 |

| N | 3,678 | |||

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.032 | |||

The effect of national identity is as expected. Individuals with exclusionist feelings

are more likely to cast a dual vote. Specifically, Spanish identity increases the

chance of carrying out a SOE transition, while those individuals who feel exclusively attached to their region are more likely

to carrying out one of the transitions that we have defined as No SOE transitions. This is consistent with previous research on dual voting that points towards the influence

of national identity (Liñeira, Robert and Jordi Muñoz. 2014. “Voto dual y abstención diferencial: ¿Quién

se comporta de manera diferente en función del tipo de elección?”, in Francesc Pallarés

(ed.), Elecciones autonómicas 2009-2012. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.Liñeira and Muñoz, 2014) and more generally, with previous studies that have found national identity to be

a determinant factor to explain whether individuals vote in regional elections based

on national or level-specific issues (Cabeza, Laura. 2018. “‘First-Order Thinking’ in Second-Order Contests: A Comparison

of Local, Regional and European Elections in Spain”, Electoral Studies, 53: 29-38. Available at:

The evaluation of the performance of the regional government also affects voters’

dual behavior. A positive retrospective evaluation of the regional government decreases

the likelihood of carrying out a No SOE transition, while it increases the chance of carrying out a SOE transition. However, evaluations of the performance of the Spanish Prime Minister do not affect

the likelihood of voting differently in the 2019 national and regional elections.

The coefficients of this variable are not statistically significant, either for SOE transitions or for No SOE transitions. Previous research on the Catalan and the Scottish cases has not found any perceptible

impact of the evaluation of the national incumbent on the likelihood of casting a

dual vote, either (Liñeira, Robert. 2011. “‘Less at Stake’ or a Different Game? Regional Elections in

Catalonia and Scotland”, Regional and Federal Studies, 21 (3): 283-303. Available at:

DISCUSSION[Up]

The 2019 regional and national elections in Spain were separated by less than a month. Taking advantage of this unprecedented quasi-simultaneous electoral setting, this article has analyzed the degree to which the 2019 Spanish regional elections may be considered second-order contests, looking at vote-switching between national and regional elections at both the aggregate and individual levels. The contribution to the literature is twofold: on the one hand, it closes an empirical gap by complementing aggregate with individual-level data; on the other hand, it proposes a new approach to the study of second-order election effects by focusing on a subgroup of the electorate, dual voters, and theoretically classifying their different vote transitions into two categories: those who vote differently because they treat regional elections as second-order elections and those who do so because they consider that the two arenas are independent.

At the aggregate level, we have observed an increasing incongruence between regional and national election results since the Great Recession. First, quasi-simultaneity did not translate into an increase in election congruence. On the contrary, it was precisely in 2019, when the time that elapsed between the national and regional elections was the shortest, where we observed the highest score on the dissimilarity index. Differences between party vote shares in regional and national elections were relatively large. Second, we have shown that in the Spanish case, the degree of election (in)congruence does not depend on the proximity or distance between elections at different political levels, but on the presence of regionalist parties. Together with increasing dissimilarity, we also observed second-order election effects when analyzing election results, with a persistent lower turnout in regional elections compared to national elections, and the increase in vote share for the PSOE, confirming the thesis of the “honeymoon period” of governing parties in temporally close elections. Contrary to the expectations of the second-order election model, however, all smaller and new parties have experienced electoral losses at the regional level compared to their vote share on the national election.

Yet, a quite different picture emerged from the analysis at the individual level. Our findings suggest that most of the dual voting at the individual level does not respond to the logic of the second-order election model but rather to voters’ autonomous considerations of the regional arena. In fact, we found no perceptible impact of the evaluation of the national incumbent on the likelihood of casting a dual vote. In this sense, our multivariate analysis has shown that two main determinants of dual voting: (1) national identity, which increases the likelihood of voting differently across national and regional elections; and (2) the evaluation of the performance of the regional government. These findings gain particular significance given that our analysis has been circumscribed to the regions that have held elections on the same date, the so-called ordinary Spanish regions. Even in these regions, that could be considered the most-likely cases for the prevalence of a second-order election vote logic, regional elections are becoming increasingly decoupled from national politics.

NOTES[Up]

| [1] |

Namely, Aragon, Asturias, Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Cantabria, Castile and Leon, Castile-La Mancha, Extremadura, Madrid, Murcia, Navarre and La Rioja. |

| [2] |

Regional presidents have the prerogative to call a snap election, but this has happened just once: in the 2019 Valencian regional election. |

| [3] |

.Spanish socialists aim to consolidate general election win. (2019, May 25). The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/may/25/spanish-socialists-aim-to-consolidate-general-election-win |

| [4] |

In June 2018, Pedro Sánchez (PSOE) became Spain’s new prime minister, thanks to a vote of no confidence —the first to succeed in Spanish democratic history— against Mariano Rajoy (PP). This event was a major achievement for Pedro Sánchez, who saw his popularity skyrocket. Sánchez appointed the cabinet with the highest proportion of female ministers in Europe and implemented a progressive program including measures such as a rise in the minimum wage, an increase in pensions and public employees’ wages, and a commitment to exhume the remains of the dictator Francisco Franco (which took place on October 24th 2019). Sánchez’s government was the shortest one in the history of Spain. After his budget plan was rejected by the parliament, Sánchez called a snap general election, where the PSOE gained most of the seats. |

| [5] |

The centralist character of this party is further corroborated by the fact that Vox, unlike all other state-wide parties in Spain, releases a single election manifesto for all regions. |

REFERENCES[Up]

|

Alonso, Sonia, Laura Cabeza and Braulio Gómez. 2017. “Disentangling Peripheral Parties’ Issue Packages in Subnational Elections”, Comparative European Politics, 15 (2): 240-263. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2015.15. |

|

|

Alonso, Sonia and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2015. “Spain: No Country for the Populist Radical Right?”, South European Society and Politics, 20 (1): 21-45. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2014.985448 |

|

|

Cabeza, Laura. 2018. “‘First-Order Thinking’ in Second-Order Contests: A Comparison of Local, Regional and European Elections in Spain”, Electoral Studies, 53: 29-38. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2018.03.004. |

|

|

Cabeza, Laura, Braulio Gómez and Sonia Alonso. 2017. “How National Parties Nationalize Regional Elections: The Case of Spain”, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 47 (1): 77-98. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjw030. |

|

|

Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS). 2019. Estudio 3253 Postelectoral elecciones autonómicas y municipales 2019. Madrid. |

|

|

Climent, Víctor and Miriam Montaner. 2020. “Los partidos populistas de extrema derecha en España: un análisis sociológico comparado”, Revista Izquierdas, 49: 910-931. |

|

|

Dandoy, Régis. 2013. “Belgium: Toward a Regionalization of National Elections?”, in Régis Dandoy and Arjan H. Schakel (eds.), Regional and National Elections in Western Europe: Territoriality of the Vote in Thirteen Countries. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137025449. |

|

|

Dinkel, Reiner. 1977. “Der Zusammenhang zwischen Bundes- und Landtagswahlergebnissen”, Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 18 (2/3): 348-359. |

|

|

Elazar, Daniel J. (ed.). 1991. Federal Systems of the World: A Handbook of Federal, Confederal and Autonomy Arrangements. Harlow: Longman Group UK Limited. |

|

|

Fernández Albertos, Joséet al. 2015. Aragon es nuestro Ohio. Así votan los españoles. Barcelona: Malpaso Editorial. |

|

|

Font, Joan. 1991. “El voto dual en Cataluña: lealtad y transferencia de votos en las elecciones autonómicas”, Revista de Estudios Políticos, 73: 7-34. |

|

|

Fraile, Marta and Santiago Pérez-Nievas. 2000. Is the Nationalist Vote Really Nationalist? Dual Voting in Catalonia 1980-1999. Estudio/Working Paper, 2000/147. Madrid: Instituto Juan March. |

|

|

Galaup, Laura and Raúl Sánchez. 2019. “La extrema derecha española no capta voto obrero: Vox despunta en los barrios ricos de las grandes ciudades”. elDiario.es, June 10, 2019. Available at: https://www.eldiario.es/politica/Vox-objetivo-seducir-despunta-ciudades_0_907109825.html. |

|

|

García Hípola, Giselle. 2014. Estrategias de comunicación política en contextos concurrenciales: las campañas electorales de 2008 y 2012 en Andalucía. Universidad de Granada. |

|

|

Garmann, Sebastian. 2017. “Election Frequency, Choice Fatigue, and Voter Turnout”, European Journal of Political Economy, 47: 19-35. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2016.12.003. |

|

|

Goitia, Lana. 2019. “Make Spain Great Again”. The Rise of Far-Right Populism in España. University of North Georgia. |

|

|

Gómez, Braulio, Sonia Alonso and Laura Cabeza. 2019a. Regional Manifestos Project Dataset (Version 11/2019). Available at: www.regionalmanifestosproject.com. |

|

|

Gómez, Braulio, Laura Cabeza and Sonia Alonso. 2019b. En busca del poder territorial: cuatro décadas de elecciones autonómicas en España. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. |

|

|

Gómez, Braulio and Ignacio Urquizu. 2015. “Political Corruption and the End of two-party system after the May 2015 Spanish Regional Elections”, Regional and Federal Studies, 25 (4): 379-389. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2015.1083013. |

|

|

Heath, Anthony, Iain McLean, Bridget Taylor and John Curtice. 1999. “Between First and Second Order: A Comparison of Voting Behaviour in European and Local Elections in Britain”, European Journal of Political Research, 35 (3): 389-414. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006924510899. |

|

|

Henderson, Ailsa and Nicola McEwen. 2010. “A Comparative Analysis of Voter Turnout in Regional Elections”, Electoral Studies, Special Symposium: Voters and Coalition Governments, 29 (3): 405-16. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2010.03.012. |

|

|

Hix, Simon and Michael Marsh. 2007. “Punishment or Protest? Understanding European Parliament Elections”, Journal of Politics, 69 (2): 495-510. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00546.x. |

|

|

Hueglin, Thomas O., and Alan Fenna. 2015. Comparative Federalism: A Systematic Inquiry. 2nd edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. |

|

|

Jeffery, Charlie and Dan Hough. 2001. “The Electoral Cycle and Multi-Level Voting in Germany”, German Politics, 10 (2): 73-98. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/772713264. |

|

|

Jeffery, Charlie and Dan Hough. 2003. “Regional Elections in Multi-Level Systems”, European Urban and Regional Studies, 10 (3): 199-212. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764030103002. |

|

|

Jeffery, Charlie and Dan Hough. 2006. “Devolution and Electoral Politics: Where Does the UK Fit In?”, in Dan Hough and Charlie Jeffery (eds.), Devolution and Electoral Politics. Manchester: Manchester University Press. |

|

|

Lagares Diez, Nieves, Carmen Ortega and Pablo Oñate. 2019. “La relevancia de las elecciones autonómicas de 2015 y 2016 en el contexto de un sistema multinivel en crisis”, in Nieves Lagares Diez, Carmen Ortega and Pablo Oñate (eds.), Las elecciones autonómicas de 2015 y 2016. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. |

|

|

Lago, Ignacio and André Blais. 2020. “El voto estratégico en las elecciones generales”, in Carmen Ortega, Juan Montabes Pereira and Pablo Oñate (eds.), Sistemas electorales en España: caracterización, efectos, rendimientos y propuestas de reforma. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. |

|

|

Leonisio, Rafael and Matthias Scantamburlo. 2019. “La competición política en el País Vasco, 1980-2016. El equilibrio entre la dimensión económica y la nacionalista”, in Braulio Gómez, Laura Cabeza and Sonia Alonso (eds.), En busca del poder territorial. Cuatro décadas de elecciones autonómicas en España. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. |

|

|

Liñeira, Robert. 2011. “‘Less at Stake’ or a Different Game? Regional Elections in Catalonia and Scotland”, Regional and Federal Studies, 21 (3): 283-303. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2011.578790. |

|

|

Liñeira, Robert and Jordi Muñoz. 2014. “Voto dual y abstención diferencial: ¿Quién se comporta de manera diferente en función del tipo de elección?”, in Francesc Pallarés (ed.), Elecciones autonómicas 2009-2012. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. |

|

|

Liñeira, Robert and Josep M. Vallès. 2014. “Differential Abstention in Catalonia and the Community of Madrid: A Socio-Political Explanation of an Urban Phenomenon”, Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 146: 69-92. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.146.69. |

|

|

Marsh, Michael. 1998. “Testing the Second-Order Election Model after Four European Elections”, British Journal of Political Science, 28 (4): 591-607. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712349800026X. |

|

|

Novo, Ainhoa, Sergio Pérez and Jonatan Garcia. 2019. “Building a Federal State: Phases and Moments of Spanish Regional (de)Centralization”, Italian Political Science Review / Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica, 49 (3): 263-277. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2018.23. |

|

|

Orriols, Lluís and Guillermo Cordero. 2016. “The Breakdown of the Spanish Two-Party System: The Upsurge of Podemos and Ciudadanos in the 2015 General Election”, South European Society and Politics, 21 (4): 469-492. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2016.1198454. |

|

|

Pallarés, Francesc and Michael Keating. 2003. “Multi-Level Electoral Competition. Regional Elections and Party Systems in Spain”, European Urban and Regional Studies, 10 (3): 239-255. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764030103005. |

|

|

Railings, Colin and Michael Thrasher. 1998. “Split‐ticket Voting at the 1997 British General and Local Elections: An Aggregate Analysis”, British Elections and Parties Review, 8 (1): 111-134. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13689889808413008. |

|

|

Reif, Karlheinz. 1984. “National Electoral Cycles and European Elections 1979 and 1984”, Electoral Studies, 3 (3): 244-255. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-3794(84)90005-2. |

|

|

Reif, Karlheinz and Hermann Schmitt. 1980. “Nine Second-Order National Elections. A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results”, European Journal of Political Research, 8 (1): 3-44. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00737.x. |

|

|

Riba, Clara. 2000. “Voto dual y abstención diferencial. Un estudio sobre el comportamiento electoral en Cataluña”, Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 91: 59-88. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/40184275. |

|

|

Riera, Pedro. 2011. “La abstención diferencial en el País Vasco y Cataluña”, Revista de Estudios Políticos, 154: 139-173. |

|

|

Riera, Pedro. 2012. “La abstención diferencial en la España de las autonomías. Pautas significativas y mecanismos explicativos”, Revista Internacional de Sociología, 70 (3): 615-642. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3989/ris.2010.10.07. |

|

|

Riera, Pedro. 2013. “Voting Differently across Electoral Arenas: Empirical Implications from a Decentralized Democracy”, International Political Science Review, 34 (5): 561-81. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512112467216. |

|

|

Rodon, Toni and María José Hierro. 2016. “Podemos and Ciudadanos Shake up the Spanish Party System: The 2015 Local and Regional Elections”, South European Society and Politics, 21 (3): 339-357. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2016.1151127. |

|

|

Romanova, Valentyna. 2014. “The Principle of Cyclicality of the Second-Order Election Theory for Simultaneous Multi-Level Elections”, Politics, 34 (2): 161-179. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.12016. |

|

|

Scantamburlo, Matthias. 2019. “Who Represents the Poor? The Corrective Potential of Populism in Spain”, Representation, 55 (4): 415-434. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2019.1669692. |

|

|

Scantamburlo, Matthias, Sonia Alonso and Braulio Gómez. 2018. “Democratic Regeneration in European Peripheral Regions: New Politics for the Territory?”, West European Politics, 41 (3): 615-639. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1403148. |

|

|

Schakel, Arjan H. 2013. “Congruence Between Regional and National Elections”, Comparative Political Studies, 46 (5): 631-662. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414011424112. |

|

|

Schakel, Arjan H. and Régis Dandoy. 2014. “Electoral Cycles and Turnout in Multilevel Electoral Systems”, West European Politics, 37 (3): 605-623. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.895526. |

|

|

Schakel, Arjan H. and Charlie Jeffery. 2013. “Are Regional Elections Really “Second-Order’ Elections?”, Regional Studies, 47 (3): 324-341. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.690069. |

|

|

Schmitt, Hermann and Ilke Toygür. 2016. “European Parliament Elections of May 2014: Driven by National Politics or EU Policy Making?”, Politics and Governance, 4 (1): 167-181. Available at: https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v4i1.464. |

|

|

Simón, Pablo. 2016. “The challenges of the new Spanish multipartism: government formation failure and the 2016 general election”, South European Society and Politics, 21 (4): 493-517. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2016.1268292. |

|

|

Turnbull-Dugarte, Stuart J. 2019. “Explaining the End of Spanish Exceptionalism and Electoral Support for Vox”, Research and Politics, 6 (2): Online first. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168019851680. |

|

|

Vampa, Davide and Matthias Scantamburlo. 2020. “The ‘Alpine Region’ and Political Change: Lessons from Bavaria and South Tyrol (1946-2018)”, Regional and Federal Studies. Online first. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2020.1722946. |

Biography[Up]

| [a] |

Research Associate at the University of Deusto and coordinator of the “Regional Manifestos Project”. She holds a PhD in Political Sciences from the University of Cologne, where she is Associate Member of the Cologne Center for Comparative Politics. Prior to joining the University of Deusto, she was a Max Weber Fellow at the European University Institute (Florence) and worked at the Instituto de Estudios Sociales Avanzados (IESA-CSIC). Her research has been published in journals such as Party Politics, Electoral Studies, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, Regional and Federal Studies and Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, among others. She has also co-authored numerous book chapters and co-edited a volume titled En busca del poder territorial: Cuatro décadas de elecciones autonómicas en España, published by the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. |

| [b] |

Postdoctoral researcher at the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid and team member of the “Regional Manifestos Project”. Previously he held research positions at Aston University (Birmingham, United Kingdom) and the University of Deusto (Bilbao, Basque Country). He completed his doctorate in Political Science at the University of Innsbruck (Austria) with a dissertation focusing on regionalist parties and multi-dimensional electoral competition. His major research interests include territorial politics, political parties, and electoral competition in multi-level settings. His research has been published in journals such as West European Politics, Regional and Federal Studies and Representation. Journal of Representative Democracy, among others. He is co-editor of Nazioni e Regioni the Italian journal on nationalism studies. |