Standing still or ascending in the social media political participation ladder? Evidence from Iran

¿Quedarse estancado o ascender en la escalera de participación política en las redes sociales? Evidencias desde Irán

ABSTRACT

The appeal of social media has transformed the ways political participation is experienced. As an online communication tool, social media platforms have changed how political content is processed and transmitted. These developments have stimulated political participatory practices even in authoritarian regimes that are less tolerant on how social media affect people’s political consciousness. This study seeks to examine whether social media platforms increase political participation in authoritarian regimes by having Iran as its case study. Iran is an authoritarian regime which imposes heavy censorship in all sorts of media and severe limitations in the freedom of speech. By introducing the Social Media Political Participation Ladder, this article accounts for both a theoretical and an empirical contribution by testing its application. Using primary data from a street survey, with a representative sample (n = 110) conducted in three different cities across Iran, we find a relatively positive impact of social media use in online political information and participation. However, the level of offline political participation remains low, showcasing no significant influence. Thus, the article verifies the different stages developed under the Social Media Political Participation ladder and Iran´s current standing on it.

Keywords: social media, Iran, online political information, online and offline participation, authoritarian regime.

RESUMEN

El recurso a las redes sociales ha transformado la forma en que experimentamos la participación política. Como una herramienta de comunicación en línea, las plataformas en las redes sociales han cambiado cómo se procesa y transmite el contenido político. Estos desarrollos han estimulado las prácticas de participación política, incluso en regímenes autoritarios, a pesar de ser menos tolerantes sobre cómo pueden afectar las redes sociales a la conciencia política de la población. Este estudio trata de examinar si las plataformas de redes sociales incrementan la participación política en regímenes autoritarios, utilizando Irán como estudio de caso. Irán es un régimen autoritario que impone una censura muy dura a todo tipo de medio de comunicación y aplica severas limitaciones a la libertad de expresión. Con la introducción de la escalera de participación política en las redes sociales, este articulo representa una contribución tanto teórica como empírica al testar su aplicación. Utilizando datos primarios extraídos de encuestas a pie de calle, con una muestra representativa (n = 110) recogida en tres grandes ciudades por todo el territorio de Irán, encontramos un impacto relativamente positivo del uso de las redes sociales sobre la información y participación política. Sin embargo, el nivel de participación política offline continúa siendo bajo, lo que demuestra una influencia poco significativa. De esta forma, se han podido verificar las diferentes etapas desarrolladas bajo la escalera de participación política en las redes sociales y la posición actual de Irán en la misma.

Palabras clave: redes sociales, Irán, información política online, participación online y offline, regímen autoritario.

INTRODUCTION[Up]

In recent years, social media have become the fastest spreading service in the world,

altering many aspects of daily life from communication, education, business, and even

politics. Social media are digital platforms that allow their users to create profiles,

share content and build a network of contacts (Boyd, Danah. 2008. “Facebook’s privacy trainwreck: Exposure, invasion, and social

convergence”, Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 14 (1): 13-20. Available at:

A first indicator of the growing popularity of social media both, in informing citizens

but also for online and offline political participation was illustrated in the 2008

US Presidential elections. Obama’s campaign used social media not only to raise funds

but to ‘’develop a groundswell of empowered volunteers who felt that they could make

a difference” (Aaker, Jennifer and Victoria Chang. 2009. Obama and the Power of Social Media and Technology. Case No. M321. Stanford: Stanford Graduate School of Business. Available at:

Political information refers to the use of social media to access news sources, while offline political participation addresses a more active stance by participating in rallies, protests or civil associations. However, the use of social media and its effects differ between democracies and authoritarian regimes. In authoritarian regimes, social media are not considered merely as a means of communication, but they hold the potential of increasing political engagement both online and offline. There have been incidents that highlight these prospects, such as the 2009 “Twitter uprising” in Iran (Bentivegna, Sara. 2002. “Politics and new media”, in Leah A. Lievrouw and Sonia Livingston, (eds.), Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Consequences of ICTs. London: SAGE Publications. Bentivegna, 2002) and the Arab Spring or “Facebook revolution” in Egypt in 2011 (El-Nawawy, Mohammed and Sahar Khamis. 2012. “Political activism 2.0: Comparing the role of social media in Egypt’s ‘Facebook revolution’ and Iran’s ‘Twitter uprising’”, CyberOrient, 6 (1): 8-33.El-Nawawy and Khamis, 2012). Social media have also been studied for their impact on democratization processes in societies where state authorities restrict communication flows.

The present study seeks to provide a more accurate understanding of social media by

examining its potential for generating political participation in authoritarian regimes.

Iran is selected as a representative authoritarian regime but also for its high level

of internet access and its young population that is increasingly familiar with new

communication technologies. According to the Global Digital Report (Global Digital Report. 2020. Digital 2020: Iran. Available at:

This article investigates the extent to which social media played a role in the dynamics of political information and online participation that could assist in advancing the offline participation in authoritarian regimes. The main research question addressed is whether social media opens up new spaces for online political participation and advocates for offline participation in Iran. Under this question, three hypotheses are formulated as follows:

-

H1. Social media are primarily used in authoritarian regimes to acquire political information.

-

H2. Social media are widely used in authoritarian regimes for online political participation.

-

H3. Increased social media engagement leads to more proactive offline political participation.

The study aims to make a theoretical contribution based on Arnstein`s (Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation”, Journal of the American Planning Association, 35 (4): 216-224. Available at:

LITERATURE REVIEW[Up]

Social media as a communication tool allows the population to participate more actively

in collective action, obtain information, engage in political discussion, and influence

a network of friends and family online. Therefore, social media can mobilize various

forms of political engagement in society (Xenos, Michael A, Ariadne Vromen and Brian D. Loader. 2014. “The great equalizer?

Patterns of social media use and youth political engagement in three advanced democracies”,

Information, Communication and Society, 17 (2): 151-167. Available at:

In terms of political participation and engagement, the literature provides a broad

framework of academic studies. For Brady (Brady, Henry. 1999. “Political Participation”, in John P. Robinson, Philip R. Shaver

and Lawrence S. Wrightsman, (eds.), Measures of Political Attitudes. San Diego: Academic Press.1999), citizens’ actions and activities must go beyond the political and social interest

of discussion, but they should also be able to influence political outcomes and the

decisions on social issues made by individuals and groups in society. The modes of

political engagement may involve collective actions, information and political participation,

production of texts and videos (Ekström, Mats and Adam Shehata. 2018. “Social media, porous boundaries, and the development

of online political engagement among young citizens”, New Media and Society, 20 (2): 740-759. Available at:

Social media favours political engagement by mobilizing information among the population

(Carlisle, Juliet E. and Robert C. Patton. 2013. “Is Social Media Changing How We Understand

Political Engagement? An Analysis of Facebook and the 2008 Presidential Election”,

Political Research Quarterly, 66 (4): 883-895. Available at:

Besides, the variety of media channels on the market has a differentiated impact on access to information or how political content is mobilized. Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram are more open channels that have a broad user base and allow people easy access to politicians’, party organizations’ and other political associations’ public accounts and research networks. They are also accessible platforms through any hardware device, i.e. computers, tablets, smartphones. Snapchat brings a more private setting and a more informal means of communication, but it has fewer profiling capabilities and can only be accessed by a mobile device. The difference in the character limitation of these channels also interferes with the communication transmitted between citizens. Facebook is a platform that allows 63,206 characters; Instagram 2,200 characters; and Twitter, only 280 characters (Bossetta, Michael. 2018. “The Digital Architectures of Social Media: Comparing Political Campaigning on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat in the 2016 U.S. Election”, Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 95 (2): 1-26. Bossetta, 2018).

Moreover, the technological evolution of online tools is a factor that has allowed

an increase in the political participation of the last years. Discussion spaces integrated

by chats and online research were already present much earlier in the digital world,

but their impacts were much limited in terms of political engagement (Carlisle, Juliet E. and Robert C. Patton. 2013. “Is Social Media Changing How We Understand

Political Engagement? An Analysis of Facebook and the 2008 Presidential Election”,

Political Research Quarterly, 66 (4): 883-895. Available at:

On the other hand, other authors (Zhang, Weiwu, Thomas J. Johnson, Trent Seltzer and Shannon L. Bichard. 2010. “The

Revolution Will be Networked: The Influence of Social Networking Sites on Political

Attitudes and Behavior”, Social Science Computer Review, 28 (1): 75-92.

In this way, social platforms facilitate political involvement by being able to attract

a wide range of users. This is due to their favourable accessibility, their presence

in daily habits, the advantageous cost and less demanding political efforts and commitments.

Social media ensures a low cost of access to political information and mobilization

compared to other instruments (newspapers, magazines, books, posters, flyers) (Carlisle, Juliet E. and Robert C. Patton. 2013. “Is Social Media Changing How We Understand

Political Engagement? An Analysis of Facebook and the 2008 Presidential Election”,

Political Research Quarterly, 66 (4): 883-895. Available at:

Thus, social media ends up being used for political engagement by a profile of the

public more inclined by these ways. Based on the Rainie’s Internet and American Life

Project (Rainie, Lee, Aaron Smith, Henry Brady and Sidney Verba. 2012. Social Media and Political Engagement. Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project. Available at:

While McClurg (McClurg, Scott D. 2003. “Social networks and political participation: The role of

social interaction in explaining political participation”, Political Research Quarterly, 56 (4): 449-464. Available at:

The role of social media may also vary according to the culture and political system

of a country. While this should not be asserted, for Boulianne (Boulianne, Shelley. 2015. “Social media use and participation: a meta-analysis of

current research, Information”, Communication and Society, 18 (5): 524-538. Available at:

SOCIAL MEDIA POLITICAL PARTICIPATION LADDER[Up]

Active citizen participation in politics is observed in acts such as voting, campaigning,

protesting organizations, and contacting representatives and officials. It is generally

perceived as a voluntary act to influence elections or public actions (Verba, Sidney, Kay L. Schlozman and Henry E. Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.Verba et al., 1995). However, political participation has been mainly associated with higher levels

of income and education, as well as specific groups, syndicates, and organized activist

groups (Smith, Aaron, Kay L. Schlozman, Sidney Verba and Henry E. Brady. 2009. “The Internet

and Civic Engagement”, Pew Research Center, 01-09-09. Available at:

Arnstein’s work (Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation”, Journal of the American Planning Association, 35 (4): 216-224. Available at:

The traditional approaches on political participation do not fully engage with the

complexities of the participatory process (Carpentier, Nico. 2016. “Beyond the ladder of participation: An analytical toolkit

for the critical analysis of participatory media processes”, Javnost-The Public, 23 (1): 70-88. Available at:

However, the introduction and widespread use of social media are considered to have

even more profoundly shaped political participation both in the online and offline

form (Jost, John T., Pablo Barberá, Richard Bonneau, Melanie Langer, Megan Metzger, Jonathan

Nagler, Joanna Sterling and Joshua Tucker. 2018. “How social media facilitates political

protest: Information, motivation, and social networks”, Political psychology, 39 (11): 85-118. Available at:

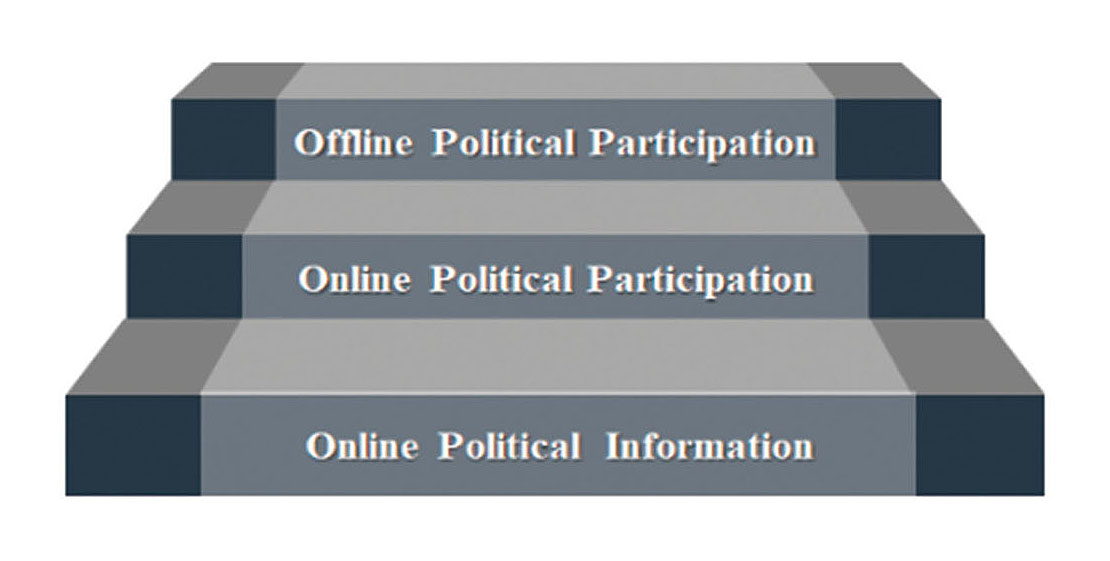

Based on these considerations, we develop the Social Media Political Participation Ladder, which identifies three stages or steps of political participation (Figure 1). The first step represents the various sources for acquiring information in social media platforms including news, commentaries and on-spot coverage of events taking place through live videos.

After having climbed this step of the ladder, citizens can proactively engage in online

discussions, create pages, support petitions and political campaigns making their

voices heard. The last step indicates that after the users have been informed and

engaged in online deliberations, they seek a more active offline political participation

as it also observed in other studies (Skoric, Marko M. and Nathaniel Poor. 2013. “Youth engagement in Singapore: The interplay

of social and traditional media”, Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 57 (2): 187-204. Available at:

IRAN’S POLITICAL SYSTEM AND CENSORSHIP OF SOCIAL MEDIA[Up]

Since the 1979 revolution, Iran’s regime was established as the first Islamic republic

system in the world, governed by religious authorities and the law of Sharia as an

integral part of the country’s legal code. According to Ayatollah Khomeini —the founder

of the Islamic Republic—, Islam defines the provisions for the political life since

“Islam itself is democratic” (Vatanka, Alex. 2015. “The Authoritarian Resurgence: Iran Abroad.”, Journal of Democracy 26 (2): 61-70. Available at:

Nevertheless, Iran’s political system has been criticized by political elites and

international organizations in the West mainly on election-related violations, freedom

of speech, inequality of gender and human rights (Tazmini, Ghoncheh. 2009. Khatami’s Iran: the Islamic Republic and the turbulent path

to reform. London and New York: IB Tauris. Available at:

The authoritarianism of the Iranian regime is particularly evident in the realm of

information technology and social media, with the hiring of thousands of “cyber-jihadists”

to monitor and control social media (Milani, Abbas. 2015. “The Authoritarian Resurgence: Iran’s Paradoxical Regime”, Journal of Democracy, 26 (2): 52-60. Available at:

Iranian online social media has played a significant role in shaping social capital

(Eloranta, Jari, Hossein Kermani and Babak Rahimi. 2015. “Facebook Iran: Social Capital

and the Iranian Social Media”, in David M. Faris and Babak Rahimi (eds.), Social media in Iran: politics and society after 2009. Albany: State University of New York Press. Eloranta et al., 2015), in empowering marginalized groups (Gheytanchi, Elham. 2015. “Gender Roles in the Social Media World of Iranian Women”,

in David M. Faris and Babak Rahimi (eds.), Social media in Iran: politics and society after 2009. Albany: State University of New York Press. Gheytanchi, 2015), as an alternative way to censorship of printed media (Michaelsen, Marcus. 2015. “The Politics of Online Journalism in Iran”, in David M.

Faris and Babak Rahimi (eds.), Social media in Iran: politics and society after 2009. Albany: State University of New York Press. Michaelsen, 2015) and as a form of political mobilization (Ekström, Mats and Adam Shehata. 2018. “Social media, porous boundaries, and the development

of online political engagement among young citizens”, New Media and Society, 20 (2): 740-759. Available at:

However, online activity in Iran is also being monitored while foreign-based websites

are banned or filtered, including news sites, search engines, entertainment channels,

email domains (Pakravan, Rudabeh. 2012. “Territory Jam: Tehran”, Places Journal, July. Available at:

THE ROLE OF SOCIAL MEDIA IN THE 2009-2018 UPRISINGS IN IRAN[Up]

This section analyzes the role of social media in the political uprisings in 2009

and 2018. The victory of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in the 2009 elections created unprecedented

unrest with public demonstrations in many cities across the country. The candidate

of the opposition Mir-Hossein Musavi and his supporters accused the regime of vote-rigging

and election fraud. Thousands of citizens took on the streets with the slogan “Where’s

my vote?”. These protests over the next months marked the beginning of the “Green

Movement” (Dabashi, Hamid. 2013. “What happened to the Green Movement in Iran?”, Al Jazeera, 12-6-2013. Available at:

The government consequently forbade the demonstrations’ coverage and imposed greater

control over online activities. The regime also used social media to coerce and threaten

activists inside and outside the country (Elson, Sara B., Douglas Yeung, Parisa Roshan, S. R. Bohandy and Alireza Nader. 2012.

“Background on Social Media Use in Iran and Events Surrounding the 2009 Election”,

in Sara Beth Elson, Douglas Yeung, Parisa Roshan, S. R. Bohandy and Alireza Nader

(eds.), Using Social Media to Gauge Iranian Public Opinion and Mood After the 2009 Election.

Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.Elson et al., 2012; Michaelsen, Marcus. 2016. “Exit and voice in a digital age: Iran’s exiled activists

and the authoritarian state”, Globalizations, 15 (2): 248-264. Available at:

Regarding the political use of social media in the Green Movement, similarities can

be seen in the context of the Arab Spring, which represented a series of social demonstrations

against the abuse of power by political authorities in the Middle East and North Africa

since late 2010. Similar to Iran, social media played a key role in channelling information,

showing the government repressions, organizing protests and giving meaning to events

of Arab Spring (Brown, Heather, Emily Guskin and Amy Mitchell. 2012. “The Role of Social Media in

the Arab Uprisings”, Pew Research Center, 28-11-12. Available at:

Nevertheless, President Ahmadinejad has been more successful in managing traditional

and online media than Arab neighbors (Elson, Sara B., Douglas Yeung, Parisa Roshan, S. R. Bohandy and Alireza Nader. 2012.

“Background on Social Media Use in Iran and Events Surrounding the 2009 Election”,

in Sara Beth Elson, Douglas Yeung, Parisa Roshan, S. R. Bohandy and Alireza Nader

(eds.), Using Social Media to Gauge Iranian Public Opinion and Mood After the 2009 Election.

Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.Elson et al., 2012; Faris, David M. 2015. “Architectures of Control and Mobilization in Egypt and Iran”,

in David M. Faris and Babak Rahimi (eds.), Social media in Iran: politics and society after 2009. Albany: State University of New York Press. Faris 2015). In the same manner, Tunisia adopted a similar filtering system; however, the government

was not effective in blocking social media (Dewey, Taylor, Juliane Kaden, Miriam Marks, Shun Matsushima and Beijing Zhu. 2012.

The impact of social media on social unrest in the Arab Spring. International Policy

Program. Stanford: Stanford University. Available at:

Social media also played an important role in the anti-government demonstrations rocking

the country in 2017-2018 when new protests burst out in Mashhad against President

Hassan Rouhani (Eltagouri, Marwa. 2018. “Tens of thousands of people have protested in Iran. Here’s

why”, Washington Post, 03-01-18. Available at:

Nevertheless, these protests were different in nature. In 2009, protesters demanded

changes that stayed however under the framework of existing politics, the overthrow

of Ahmadinejad’s and the establishment of Mousavi as president, more social freedoms

and less oppression by the security forces. Contrarily the 2018 demands were much

more radical, with the opposition insisting on the removal of Khamenei from power

and the end of the regime (Quinn, Michelle. 2018. “One Difference Between 2009 vs 2018 Iran Protests? 48 Million

Smartphones”, VOA, 03-01-18. Available at:

METHOD AND SAMPLE[Up]

The study aims to test the theory of the participation ladder in social media. To

do so, we employed the case survey research method aiming to combine the benefits

of both a survey and a case study, using cross-sectional data and in-depth analysis

(Larsson, Rikard. 1993. “Case survey methodology: Quantitative analysis of patterns

across case studies”, Academy of management Journal, 36 (6): 1515-1546. Disponible ena.

Conducting interviews in the Middle East has proven quite demanding regarding ethical

and political considerations (Clark, Janine A. 2006. “Field research methods in the Middle East”, Political Science and Politics, 39 (3): 417-423. Available at:

The questionnaire was conducted in the Persian language in three Iranian cities Tehran, Shiraz and Zahedan in April 2019, with the assistance of three residents, who were PhD students in social sciences trained for completing the interviews. The three cities differ significantly from one another in population, economic prosperity and educational level, while the number of internet, mobile and social media users varies between them, thus constituting a representative sample of the Iranian society. Tehran is the capital city with 9,135,000 population, 40.2 % of economic participation rate and 24.9 % of the country’s total Internet users; Shiraz is a medium size city of 1,565,572 people and Zahedan is a rather small city with 609,263 population[6].

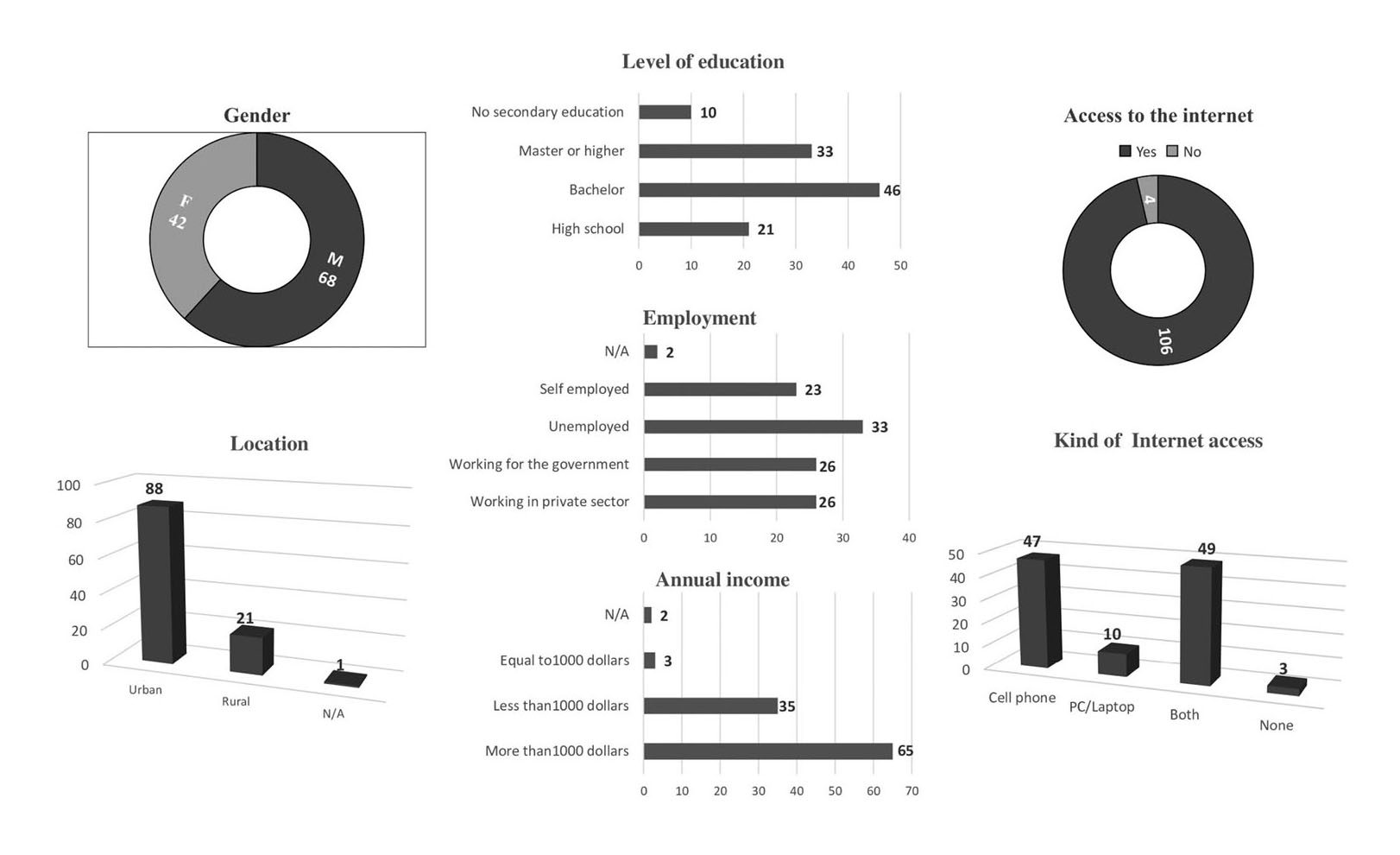

The interviews were conducted by approaching people in streets and parks[7] and lasted an average of 10-15 minutes. Interviewees were informed that their participation is entirely voluntary, anonymous, to be used for academic purposes and that they can abandon it at any time even after it has been started. Respondents were selected randomly however not all wished to complete the questionnaire, and some left in the middle of the process. The number of fully completed questionnaires was 110 (n = 110). Figure 2 presents the demographic variables.

RESULTS AND ANALYSIS[Up]

Demographic Questions[Up]

From the total number of interviewees, 68 were male, and 42 were female. The second demographic question in the sample was age: 19 ranged between 18-24 years old, 43 between 25-34 years old, 28 between 35-44 years old, 12 between 45-59 years old, and eight were older than 59 years.

The next question concerned the respondents’ education level, who were distributed as follows: no secondary education 10, completed high school 21, bachelor’s degree holders of 46, and master’s or higher degree holders 10. Regarding the type of employment, in the public sector or governmental position 26, work in private sector 26, freelancer or self-employed 23, unemployed 33 while two chose not to respond to this question. The next question concerned the annual income, and the responses resulted in: 65 more than 1000 dollars, 35 less than 1000 dollars, three equal to 1000 and two did not want to disclose this information. Lastly, concerning the residency, 88 of the interviewees live in an urban area and 21 in a rural one, while one gave no response. Lastly, regarding access to the internet, 106 of the sample answered that they have private access to the internet and four do not have. On the specific type of internet access, 47 stated to have only mobile internet access, 10 only on PC or laptop, 44 on both and four none.

According to these results, our sample is characterized by a male, urban, young adult, and a highly educated majority, with access to the internet, satisfactory income, employed both in the private and public sector.

Online political information questions[Up]

Social media has brought a new dynamic to the way political information is transmitted

and consumed by citizens. Access and exposure to news through social media has been

expanding rapidly. Often, quality content is produced by digital platform experts

that enable citizens to gain political knowledge (Bode, Leticia. 2015. “Political News in the News Feed: Learning Politics from Social

Media”, Mass Communication and Society, 19 (1): 1-25. Available at:

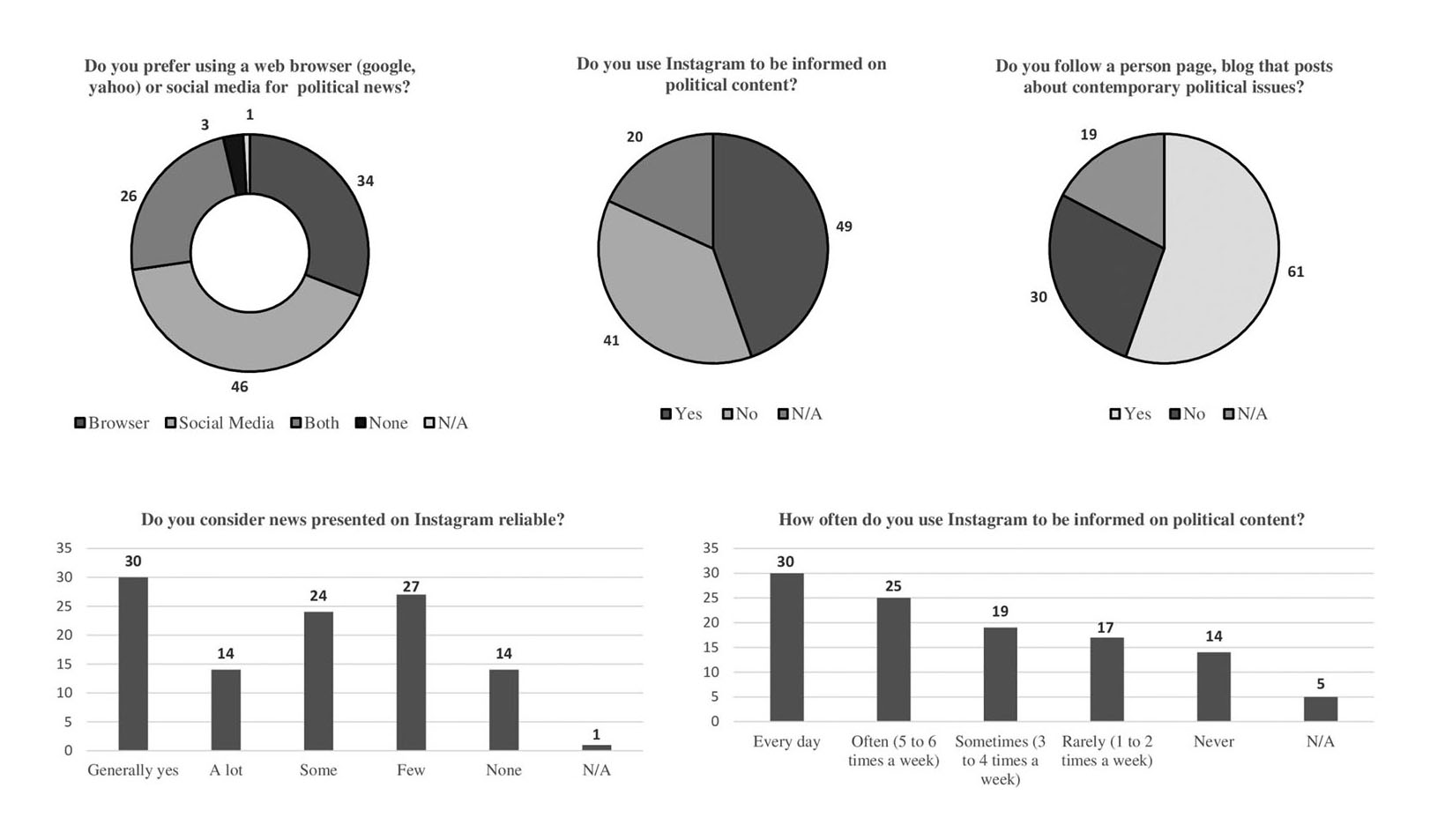

The responses allow us to affirm that there is a considerable number of Iranians who use social media in receiving political information as a primary source; thus, our first hypothesis is verified. From the participants, 46 responded they would use social media, 34 browsers, 26 both resources, three responded none and one did not wish to respond. Considering the frequency of using social media to stay informed of political issues, 30 mentioned every day, 25 often (five to six times a week), 19 sometimes (three to four times a week), 17 rarely (one to two times a week), 14 never and five did not wish to respond. Now, regarding the particular use of Instagram, there is a balance among Iranians who choose this resource to be informed about the political content. From the respondents, 49 use Instagram for this purpose, 41 do not use it, and 20 did not wish to respond. The survey also allows us to assess whether Iranians have confidence in the information provided by social media. From the respondents, 30 generally consider it reliable, 14 a lot reliable, 24 some, 27 few, 14 none and one did not wish to respond. We can also see that it is common among Iranians to follow pages of people or blogs that publish on contemporary political issues. From the respondents, 61 reported following person pages or blogs with political content, 30 did not, and 19 did not wish to respond.

In short, the role of social media in serving the purpose of obtaining political information

is more significant. This rise of social media in obtaining news has led to a decrease

in the dependence of Iranians from traditional media (Gallagher Nancy, Ebrahim Mohseni and Clay Ramsay. 2019. Iranian Public Opinion under “Maximum Pressure”. The Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland (CISSM) and Iran Poll.

Available at:

Online political participation questions[Up]

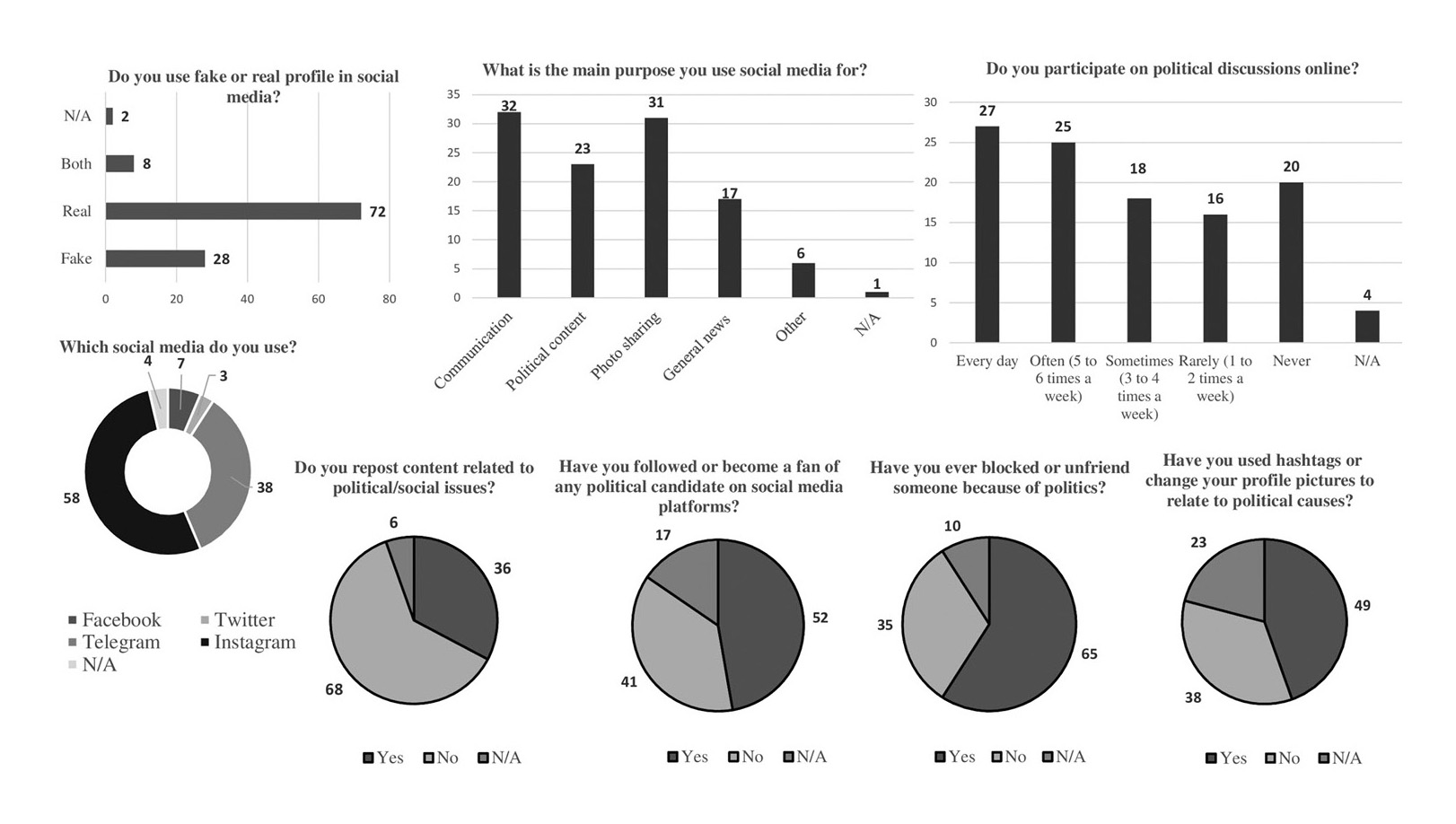

Online political participation means that a person participates in the political process by spreading their opinions and beliefs through the digital path. In this section, as we can see in Figure 4, we will look at how Iranians have participated in political activities through social media and whether there is any significant repercussion of political participation. Most Iranians have a real profile on social media. From the respondents, 72 use real profiles, 28 fake, eight both and two did not wish to respond. Besides, most Iranians use social media to communicate. Among the respondents, 32 mentioned communication, 23 political content, 31 photo sharing, 17 general news, 6 responded other people, and one did not wish to respond.

According to the responses, we can confirm that Instagram is the most widely used

digital platform among Iranians. in fact, 58 of them use Instagram, seven Facebook,

three Twitter, 38 Telegram and four did not wish to respond. These results indicate

that Iranians also use other social media that have been banned in the country with

the most popular social media being Instagram and Telegram also verified in other

surveys (Gallagher Nancy, Ebrahim Mohseni and Clay Ramsay. 2019. Iranian Public Opinion under “Maximum Pressure”. The Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland (CISSM) and Iran Poll.

Available at:

The results show that Iranians somehow moderately react online to political opinions within a network of friends and family. 65 respondents mentioned that they have already blocked or unfriend, 35 have not, and only 10 did not wish to respond. There is also a moderate number of Iranians who follow or become a fan of any political candidate on social media. Among the respondents, 52 have followed, 41 have not followed, and 17 did not wish to respond. Regarding the use of hashtags in profile pictures as an indication of supporting political causes, Iranians have not promoted this practice extensively. 49 respondents have used it, 38 have not used it, and 23 did not wish to respond.

Thus, the role of social media in leveraging online political participation in Iranian

society appears not to be significant; although there is a moderate influence in terms

of maintaining communication, following pages of political candidates and reacting

to the circle of friendship regarding the diversity of political opinions. Regarding

the second stage of the SMPPL, which refers to the engagement of the users online,

the Iranian society reaches a moderate way, thus, not verifying the second hypothesis.

Similar conclusions were drawn from studies focusing on Facebook users in Iran, revealing

that Iranians are rather “passive” users, mostly following or liking content than

commenting on political posts. Additionally, the majority of the people interviewed

responded that they share mostly personal rather political content or news (Iran Media Program. 2014. Liking Facebook in Tehran: Social Networking in Iran. Available at:

Offline political participation questions[Up]

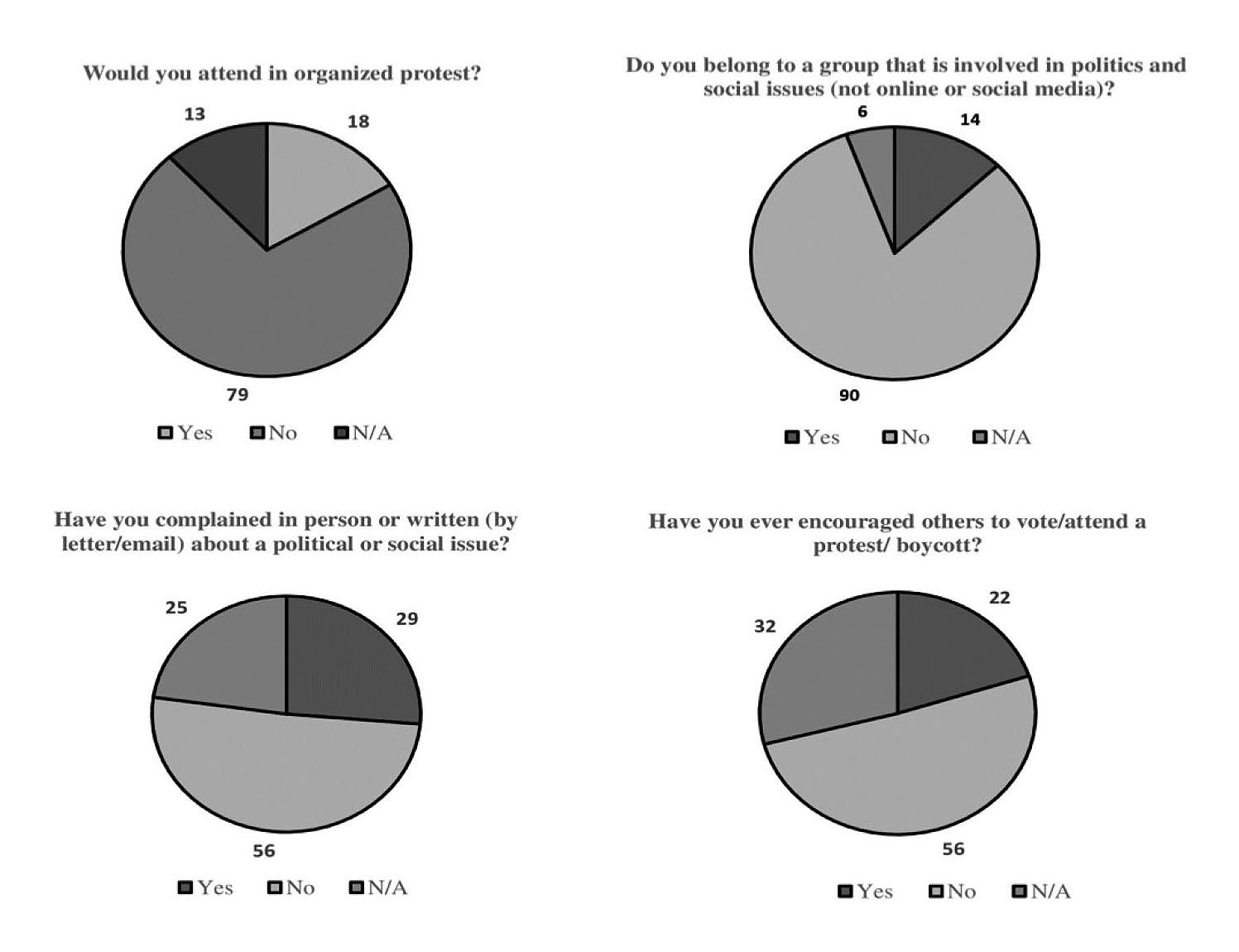

Offline political participation is one of the traditional forms of involvement that allows individuals to express their position and political opinion through participation in protests, political rallies, public audience, work, or volunteering in any political party. In this section, as we can (Figure 5), we will look at Iranian political participation through offline resources. Thus, we can compare whether there is a greater willingness of Iranians to participate in politics online or offline and whether social media has provided a significant role in this motivation. The questionnaire confirms that most Iranians have little propensity to attend political protests. From the respondents, 79 would not attend in an organized protest, 18 would attend, and 13 did not wish to respond.

Few Iranians have been engaged in traditional groups of political or social content. From the respondents, only 14 have belonged to a group, 90 have not belonged, and six did not wish to respond. Similarly, there is little encouragement among Iranians. Of the respondents, 22 have ever encouraged other people to vote or to participate in a political protest/boycott, 56 have not encouraged, and 32 did not wish to respond. It is not very common among Iranians to contact a national or local government official about an issue. From the respondents, 26 have contacted, 56 have not, and 25 did not wish to respond. As expected, Iranians have not complained in writing or person about political or social issues. From respondents, nine have complained quite often, five often, 14 rarely, 12 not quite often, 19 seldom, 39 never, 12 did not wish to respond.

Overall, the role of social media in fostering offline political participation has

no significant weight. Iranian society hardly uses social media to promote protests,

political rallies, or participation in public deliberations; offline political participation

seems to have almost no significant weight in Iranian society. Regarding the third

level of the SMPPL which refers to an active form of offline political participation

that represents the empowerment of citizens in societal and political issues we notice

that Iranians do not actively participate in shaping the government agenda or promoting

and engaging in initiatives of offline political participation even to safeguard their

rights. The third hypothesis of this study is not verified. This outcome has been

presented in other studies that question the ability of social media in “fuelling

activist protest and sustain revolution” (Wojcieszak, Magdalena and Briar Smith. 2013.“Will Politics Be Tweeted? New Media Use

by Iranian Youth in 2011”, New Media and Society, 16 (1): 91-109. Available at:

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS[Up]

This article constitutes a contribution to the area of Political Science by analyzing the impact of social media on promoting political participation in Iran as a representative case study of authoritarian regimes. As discussed, the use of social media is vigorously restricted in Iranian society because of its authoritarian political system. As a result of the political censorship in Iran, many of the digital platforms have already been banned from use. By employing a survey conducted in Iran, this study has sought to provide an understanding of the links between social media and political participation.

Accordingly, with the introduction of the Social Media Political Participation Ladder (SMPPL), we list three possible analytical dimensions where social media can gain an influential role: online political information, online and offline political participation. Based on this theoretical underpinning, political participation is perceived as a process whereby the respective society takes a gradual “step-up or stage-up” approach. According to the SMPPL, only after having achieved a higher level of political information, a developed interest in being more involved in online political discussions and initiatives emerges thus, advancing to a more proactive online political behaviour. Consequently, after the second stage of online political participation, further stimulation will encourage an increased propensity to discuss and engage offline, reaching the top of the ladder.

The findings of this study demonstrate that the impact of social media in Iran does

work largely in this stepwise format. Furthermore, the responses provided are to a

degree consistent with those of Wojcieszak and Smith (Wojcieszak, Magdalena and Briar Smith. 2013.“Will Politics Be Tweeted? New Media Use

by Iranian Youth in 2011”, New Media and Society, 16 (1): 91-109. Available at:

Our second hypothesis that considers that social media are used widely for online political participation was not verified with the sample of the survey revealing a rather moderate online political participation in Iran. Thus, considerations that praise the role of social media as a critical element in active political engagement in authoritarian regimes need to be re-evaluated. Finally, there is no validation of the third hypothesis that accounts for significant effects of using social media in offline political participation. A great majority of respondents had not engaged in any format of offline political participation. This may suggest that the fear of the regime is still quite prominent in the country.

In conclusion, the findings of this study match the conclusions of the existing literature on the use and impact of social media in authoritarian regimes. More notably, this article confirms that social media has not impacted drastically active political participation in Iran. In brief, Iranian society is on an ascending process but currently standing on the first stage of political information.

NOTES[Up]

| [1] |

Government of the mullahs (clerics). |

| [2] |

Al Jazeera. 2017. “Iran blocks Instagram, Telegram after protests”. Available at: https://bit.ly/2VXq82t [Last accessed: May 8th 2019]. |

| [3] |

StatCounter. 2019. Social Media Stats in Islamic Republic of Iran. Available at: https://gs.statcounter.com/social-media-stats/all/iran [Last accessed: May 10th 2019]. |

| [4] |

It means “we regret” (our vote). |

| [5] |

Also known as standardized survey interviewing. |

| [6] |

Statistical Center of Iran. 2020. Census 2016. Available at:https://www.amar.org.ir/english [Last accessed: May 5th 2020]. |

| [7] |

Shiraz: Zand street and Eram garden street (شیراز: خیابان زند و خیابان ارم), Tehran:

Enghelab street and Tajrish street (تهران : خیالان انقلاب و خیابان تجریش) and Zahedan:

Janbazan street and Keshavarz street (زاهدان : خیابان جانبازان و خیابان کشاورز). |

References[Up]

|

Aaker, Jennifer and Victoria Chang. 2009. Obama and the Power of Social Media and Technology. Case No. M321. Stanford: Stanford Graduate School of Business. Available at: https://stanford.io/3e7zRJJ [Last accessed: May 2nd 2020]. |

|

|

Alami, Abdolreza. 2017. Social media use and political behavior of Iranian university students as mediated by political knowledge and attitude. Adnan, Hamedi Mohid (dir.). University of Malaya, Malaysia. |

|

|

Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation”, Journal of the American Planning Association, 35 (4): 216-224. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01 944366908977225. |

|

|

Asadzade, Peyman. 2018. “New data shed light on the dramatic protests in Iran”, Washington Post, 1-1-2018. Available at: https://wapo.st/2Dd1Cni [Last aceessed: May 8th 2019]. |

|

|

Bailly, Jordan. 2012. The Impact of Social Media on Social Movements: A Case Study of the 2009 Iranian Green Movement and the 2011 Egyptian Revolution. Cottam, Martha (dir.). Washington State University, Washington. |

|

|

Baumgartner, Jody C. and Jonathan S. Morris. 2009. “MyFaceTube Politics Social Networking Web Sites and Political Engagement of Young Adults”, Social Science Computer Review, 28 (1): 24-44. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439 309334325. |

|

|

Bentivegna, Sara. 2002. “Politics and new media”, in Leah A. Lievrouw and Sonia Livingston, (eds.), Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Consequences of ICTs. London: SAGE Publications. |

|

|

Bode, Leticia. 2015. “Political News in the News Feed: Learning Politics from Social Media”, Mass Communication and Society, 19 (1): 1-25. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2015.1045149. |

|

|

Bossetta, Michael. 2018. “The Digital Architectures of Social Media: Comparing Political Campaigning on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat in the 2016 U.S. Election”, Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 95 (2): 1-26. |

|

|

Boulianne, Shelley. 2015. “Social media use and participation: a meta-analysis of current research, Information”, Communication and Society, 18 (5): 524-538. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1008542. |

|

|

Boyd, Danah. 2008. “Facebook’s privacy trainwreck: Exposure, invasion, and social convergence”, Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 14 (1): 13-20. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856507084416. |

|

|

Brady, Henry. 1999. “Political Participation”, in John P. Robinson, Philip R. Shaver and Lawrence S. Wrightsman, (eds.), Measures of Political Attitudes. San Diego: Academic Press. |

|

|

Brown, Heather, Emily Guskin and Amy Mitchell. 2012. “The Role of Social Media in the Arab Uprisings”, Pew Research Center, 28-11-12. Available at: https://www.journalism.org/2012/11/28/role-social-media-arab-uprisings/ [Last accessed: May 5th 2020] |

|

|

Carlisle, Juliet E. and Robert C. Patton. 2013. “Is Social Media Changing How We Understand Political Engagement? An Analysis of Facebook and the 2008 Presidential Election”, Political Research Quarterly, 66 (4): 883-895. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912913482758. |

|

|

Carpentier, Nico. 2016. “Beyond the ladder of participation: An analytical toolkit for the critical analysis of participatory media processes”, Javnost-The Public, 23 (1): 70-88. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2016.1149760. |

|

|

Casero-Ripollés, Andreu. 2018. “Research on political information and social media: Key points and challenges for the future”, El Profesional de la Información, 27 (5): 964-974. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2018.sep.01. |

|

|

Castells, Manuel. 2012. Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the Internet age. Malden: Polity Press. |

|

|

Cho, Jaeho, Dhavan V. Shah, Jack M. McLeod, Douglas M. McLeod, Rosanne M. Scholl and Melissa R. Gotlieb. 2009. “Campaigns, reflection, and deliberation: Advancing an OSROR model of communication effects”, Communication Theory, 19 (1): 66-88. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.01333.x. |

|

|

Clark, Janine A. 2006. “Field research methods in the Middle East”, Political Science and Politics, 39 (3): 417-423. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096506060707. |

|

|

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). 2019. Iran / Middle East & North Africa: Journalists attacked in Iran since 1992. Available at: https://cpj.org/mideast/iran/ [Last accessed: May 8th 2019] |

|

|

Costanza-Chock, Sasha. 2008. “The Immigrant Rights Movement on the Net: Between ‘Web 2.0’ and Comunicación Popular”, American Quarterly, 60 (3): 851-864. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.0.0029. |

|

|

Dabashi, Hamid. 2013. “What happened to the Green Movement in Iran?”, Al Jazeera, 12-6-2013. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2013/05/201351661225981675.html. |

|

|

Dewey, Taylor, Juliane Kaden, Miriam Marks, Shun Matsushima and Beijing Zhu. 2012. The impact of social media on social unrest in the Arab Spring. International Policy Program. Stanford: Stanford University. Available at: https://stanford.io/2Dgohz7 [Last accessed: May 5th 2020]. |

|

|

Effing, Robbin, Jos van Hillegersbergand and Theo Huibers. 2011. “Social Media and Political Participation: Are Facebook, Twitter and YouTube Democratizing Our Political Systems?”, in Efthimios Tambouris, Ann Macintosh and Hans De Bruijn, (eds.), Electronic Participation. Berlin: Heidelberg. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-23333-3_3. |

|

|

Ekman, Joakim. 2009. “Political Participation and Regime Stability: A Framework for Analyzing Hybrid Regimes”, International Political Science Review, 30 (1): 7-31. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512108097054. |

|

|

Ekström, Mats and Adam Shehata. 2018. “Social media, porous boundaries, and the development of online political engagement among young citizens”, New Media and Society, 20 (2): 740-759. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816670325. |

|

|

El-Nawawy, Mohammed and Sahar Khamis. 2012. “Political activism 2.0: Comparing the role of social media in Egypt’s ‘Facebook revolution’ and Iran’s ‘Twitter uprising’”, CyberOrient, 6 (1): 8-33. |

|

|

Eloranta, Jari, Hossein Kermani and Babak Rahimi. 2015. “Facebook Iran: Social Capital and the Iranian Social Media”, in David M. Faris and Babak Rahimi (eds.), Social media in Iran: politics and society after 2009. Albany: State University of New York Press. |

|

|

Elson, Sara B., Douglas Yeung, Parisa Roshan, S. R. Bohandy and Alireza Nader. 2012. “Background on Social Media Use in Iran and Events Surrounding the 2009 Election”, in Sara Beth Elson, Douglas Yeung, Parisa Roshan, S. R. Bohandy and Alireza Nader (eds.), Using Social Media to Gauge Iranian Public Opinion and Mood After the 2009 Election. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. |

|

|

Eltagouri, Marwa. 2018. “Tens of thousands of people have protested in Iran. Here’s why”, Washington Post, 03-01-18. Available at: https://wapo.st/2VPUbsP [Last acessed: May 15th 2019]. |

|

|

Ems, Lindsay. 2014. “Twitter’s place in the tussle: how old power struggles play out on a new stage”, Media, Culture and Society, 36 (5): 720-731. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443714529070. |

|

|

Esfahlani, Mohammad S. 2015. “The Politics and Anti-Politics of Facebook in Context of the Iranian 2009 Presidential Elections and Beyond”, in David M. Faris and Babak Rahimi (eds.), Social media in Iran: politics and society after 2009. Albany: State University of New York Press. |

|

|

Esfandiari, Golnaz. 2017. Iranian Politicians Who Use Twitter Despite State Ban. RFE/RL: Free Media In Unfree Societies. Available at: https://www.rferl.org/a/iranian-politicians-twitter-ban/28701701.html [Last accessed: May 11th 2020]. |

|

|

Eveland, William P. 2004. “The effect of political discussion in producing informed citizens: The roles of information, motivation, and elaboration”, Political Communication, 21 (2): 177-193. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600490443877. |

|

|

Ehteshami, Anoushiravan and Luciano Zaccara. 2013. “Reflections on Iran’s 2013 Presidential Elections”, Orient, 4 (54): 7-14. |

|

|

Faris, David M. 2015. “Architectures of Control and Mobilization in Egypt and Iran”, in David M. Faris and Babak Rahimi (eds.), Social media in Iran: politics and society after 2009. Albany: State University of New York Press. |

|

|

Fountain, Megan. 2017. Social Media and its Effects in Politics: The Factors that Influence Social Media use for Political News and Social Media use Influencing Political Participation. Wood, Thomas and Acree, Brice (dirs.). Department of Political Science, Ohio State University. |

|

|

Freedom House. 2019. Freedom in the World 2019: Iran. Available at: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/iran. |

|

|

Gallagher Nancy, Ebrahim Mohseni and Clay Ramsay. 2019. Iranian Public Opinion under “Maximum Pressure”. The Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland (CISSM) and Iran Poll. Available at: https://bit.ly/2Ca5Ag2 [Last accessed: May 7th 2019] |

|

|

German, Kathleen M. 2014. “Social Media and Citizen Journalism in the 2009 Iranian Protests: The Case of Neda Agha-Soltan”, Journal of Mass Communication Journalism, 4 (5): 1-8. Available at: https://doi.org/10.412/2165-7912.1000195. |

|

|

Gheytanchi, Elham. 2015. “Gender Roles in the Social Media World of Iranian Women”, in David M. Faris and Babak Rahimi (eds.), Social media in Iran: politics and society after 2009. Albany: State University of New York Press. |

|

|

Gil de Zúñiga, Homero, Nakwon Jung and Sebastián Valenzuela. 2012. “Social media use for news and individuals’ social capital, civic engagement and political participation”, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, (17) 3: 319-336. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01574.x. |

|

|

Gleason, Benjamin. 2013. “# Occupy Wall Street: Exploring informal learning about a social movement on Twitter”, American Behavioral Scientist, 57 (7): 966-982. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213479372. |

|

|

Global Digital Report. 2020. Digital 2020: Iran. Available at: https://bit.ly/2NZxKgu [Last accessed:May 7th 2019]. |

|

|

Howard, Philip. N., Sheetal D. Agarwal and Muzammil M. Hussain. 2011. “When Do States Disconnect Their Digital Networks? Regime Responses to the Political Uses of Social Media”, The Communication Review, 14 (3): 216-232. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10714421.2011.597254. |

|

|

Iran Media Program. 2014. Liking Facebook in Tehran: Social Networking in Iran. Available at: https://bit.ly/31TjnlZ [Last accessed: 30 April 2020]. |

|

|

Jost, John T., Pablo Barberá, Richard Bonneau, Melanie Langer, Megan Metzger, Jonathan Nagler, Joanna Sterling and Joshua Tucker. 2018. “How social media facilitates political protest: Information, motivation, and social networks”, Political psychology, 39 (11): 85-118. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12478. |

|

|

Kadivar, Jamileh. 2015. “A Comparative Study of Government Surveillance of Social Media and Mobile Phone Communications during Iran’s Green Movement (2009) and the UK Riots (2011)”, Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society, 13 (1): 169-191. Available at: https://doi.org/ 10.31269/vol13iss1pp169-191. |

|

|

Ketabchi, Kaveh, Masoud Asadpour and Seyed Amin Tabatabaei. 2013. “Mutual influence of Twitter and postelection events of Iranian presidential election”, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 100 (40): 40-56. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.698. |

|

|

Kurtz, Howard. 1995. “Webs of Political Intrigue: candidates, media looking for internet Constituents”, Washington Post, 13-11-95. Available at: https://wapo.st/2Z47zLU [Consulted: 22 May 2019]. |

|

|

Kurun, Ismail. 2017. “Iranian Political System: ‘Mullocracy?’”, Journal of Management and Economics Research, 15 (1): 113-129. Available at: https://doi.org/10.11611/yead.285351. |

|

|

Larsson, Rikard. 1993. “Case survey methodology: Quantitative analysis of patterns across case studies”, Academy of management Journal, 36 (6): 1515-1546. Disponible ena. https://doi.org/10.5465/256820. |

|

|

Levi, Margaret and Laura Stoker. 2000. “Political trust and trustworthiness”, Annual Review of Political Science, 3 (1): 475-507. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.475. |

|

|

Macintosh, Ann. 2004. “Characterizing e-participation in policy-making”, in Proceedings of the 37th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, IEEE. Computer Society Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2004.1265300. |

|

|

Margetts, Helen, Peter John, Scot Hale and Taha Yasseri. 2015. Political Turbulence: How Social Media Shape Collective Action. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc773c7. |

|

|

McClurg, Scott D. 2003. “Social networks and political participation: The role of social interaction in explaining political participation”, Political Research Quarterly, 56 (4): 449-464. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290305600407. |

|

|

Michaelsen, Marcus. 2015. “The Politics of Online Journalism in Iran”, in David M. Faris and Babak Rahimi (eds.), Social media in Iran: politics and society after 2009. Albany: State University of New York Press. |

|

|

Michaelsen, Marcus. 2016. “Exit and voice in a digital age: Iran’s exiled activists and the authoritarian state”, Globalizations, 15 (2): 248-264. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2016.1263078. |

|

|

Milani, Abbas. 2015. “The Authoritarian Resurgence: Iran’s Paradoxical Regime”, Journal of Democracy, 26 (2): 52-60. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2015.0034. |

|

|

Mills, Albert J., Gabrielle Durepos and Elden Wiebe. 2010. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412957397. |

|

|

Mossberger, Karen, Caroline J. Tolbert and Ramona S. McNeal. 2008. Digital Citizenship: The Internet, Society and Participation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/7428.001.0001. |

|

|

Payvand. 2009. Iran’s elections topped Twitter’s list of most popular topics of 2009. Available at: https://bit.ly/3f8Gtc9 [Last accessed: 25 July 2019]. |

|

|

Pakravan, Rudabeh. 2012. “Territory Jam: Tehran”, Places Journal, July. Available at: https://doi.org/10.22269/120709. |

|

|

Papan-Matin, Firoozeh. 2014. “Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran (1989 Edition)”, Iranian Studies, 47 (1): 159-200. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/00210862.2013.825505. |

|

|

Pejman Abdolmohammadi and Giampiero Cama. 2015. “Iran as a Peculiar Hybrid Regime: Structure and Dynamics of the Islamic Republic”, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 42 (4): 558-578. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13530194.2015.1037246. |

|

|

Quinn, Michelle. 2018. “One Difference Between 2009 vs 2018 Iran Protests? 48 Million Smartphones”, VOA, 03-01-18. Available at: https://bit.ly/2Dd5AfG [Last accessed: April 28th 2019]. |

|

|

Rainie, Lee, Aaron Smith, Henry Brady and Sidney Verba. 2012. Social Media and Political Engagement. Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-0315-8.ch003. |

|

|

Rajavi, Maryam. 2018. “These Iranian Protests are Different From 2009”, WSJ, 08-01-18. Available at: https://on.wsj.com/2VYNkxk [Last accessed: June 15th 2019]. |

|

|

RSF-Reporters without Borders. 2020. World Press Index. Available at: https://rsf.org/en/ranking [Last accessed: 2 May 2020]. |

|

|

Reuter, Ora. J. and David Szakonyi. 2013. “Online Social Media and Political Awareness in Authoritarian Regimes”, British Journal of Political Science, 45 (1): 29-51. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123413000203. |

|

|

Romano, David. 2006. “Conducting research in the Middle East’s conflict zones”, Political Science and Politics, 39 (3): 439-441. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096506060768. |

|

|

Saidi, Mike. 2018. “More Protests, No Progress: the 2018 Iran Protests”, Critical Threats, 28-11-18. Available online: https://bit.ly/2O1hlIb [Last accessed: August 15th 2019]. |

|

|

Schmid, Peter D. 2002. “Expect the unexpected: A religious democracy in Iran”, The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 9 (2): 181-196. |

|

|

Siraki, Garineh K. 2018. “The Role of Social Networks on Socialization and Political Participation of Political science Students of Islamic Azad University, South Tehran Branch (2007-2017)”, Preprints, 1-20. Available at: https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints201812.0255.v1. |

|

|

SimilarWeb. 2019. Top websites ranking. Available at: https://www.similarweb.com/top-websites [Last accessed: May 5th 2020]. |

|

|

Skoric, Marko M. and Nathaniel Poor. 2013. “Youth engagement in Singapore: The interplay of social and traditional media”, Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 57 (2): 187-204. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2013.787076. |

|

|

Smith, Aaron, Kay L. Schlozman, Sidney Verba and Henry E. Brady. 2009. “The Internet and Civic Engagement”, Pew Research Center, 01-09-09. Available at: https://pewrsr.ch/2O74fJq [Last accessed: April 16th 2019]. |

|

|

Sung, Wookjoon and Changki Jang. 2020. “Does Online Political Participation Reinforce Offline Political Participation?: Using Instrumental Variable”, in Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Available at: https://doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2020.222. |

|

|

Szmolka, Inmaculada. 2017. “Successful and Failed Transitions to Democracy”, in Inmaculada Szmolka (ed.), Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa: After the Arab Spring. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3366/edinburgh/9781474415286.003.0016. |

|

|

Tazmini, Ghoncheh. 2009. Khatami’s Iran: the Islamic Republic and the turbulent path to reform. London and New York: IB Tauris. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5040/9780755610105. |

|

|

The Economist. 2018. Iran is in turmoil but the clerics and their allies remain entrenched. Available at: https://econ.st/3f6jKNW [Last accessed:May 15th 2020] |

|

|

The Economist. 2019. Democracy Index 2019. Available at: https://www.eiu.com/topic/democracy-index. |

|

|

Tusa, Feliz. 2013. “How Social Media Can Shape a Protest Movement: The Cases of Egypt in 2011 and Iran in 2009”, Arab Media and Society, 7: 1-19. |

|

|

Vatanka, Alex. 2015. “The Authoritarian Resurgence: Iran Abroad.”, Journal of Democracy 26 (2): 61-70. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2015.0037. |

|

|

Verba, Sidney, Kay L. Schlozman and Henry E. Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. |

|

|

Vitak, Jessica, Paul Zube, Andrew Smock, Caleb T. Carr, Nicole Ellison and Cliff Lampe. 2011. “It’s complicated: Facebook users’ political participation in the 2008 election”, CyberPsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14 (3): 107-114. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0226. |

|

|

Wakabi, Wairagala and Åke Grönlund. 2019. “When SNS use doesn’t trigger e-participation: case study of an African Authoritarian Regime.”, in Yoshino Woodard White (ed.), Civic Engagement and Politics: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications. Pennsylvania: IGI Global. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-7669-3.ch056. |

|

|

Wojcieszak, Magdalena and Briar Smith. 2013.“Will Politics Be Tweeted? New Media Use by Iranian Youth in 2011”, New Media and Society, 16 (1): 91-109. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813479594. |

|

|

World Justice Project. 2020. Rule of Law Index 2020.Available at: https://bit.ly/2VUBRid [Last accessed: May 11th 2020]. |

|

|

Xenos, Michael A, Ariadne Vromen and Brian D. Loader. 2014. “The great equalizer? Patterns of social media use and youth political engagement in three advanced democracies”, Information, Communication and Society, 17 (2): 151-167. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.871318. |

|

|

Yucesou, Tayfun and Burak Karabulut. 2019. “Iranians Revolution’s Demands under the Shadow of Spiral of Silence: A Content Analysis of Twitter Messages in Iranian Mass Movement”, Global Media Journal: Turkish Edition, 9 (18): 48-70. |

|

|

Zaccara, Luciano. 2012. “The 2009 Iranian presidential elections in comparative perspective”, in Anoushiravan Ehteshami and Reza Molavi (eds.), Iran and the international system. New York: Routledge. |

|

|

Zhang, Weiwu, Thomas J. Johnson, Trent Seltzer and Shannon L. Bichard. 2010. “The Revolution Will be Networked: The Influence of Social Networking Sites on Political Attitudes and Behavior”, Social Science Computer Review, 28 (1): 75-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439309335162. |

|

|

Zogby, James. 2011. Social media and the Arab Spring. Zogby Research Services. Available at: https://bit.ly/31Sx1Wp [Last accessed: May 14th 2020]. |

Biography[Up]

| [a] |

PhD Candidate of International Relations at the University of Minho (Portugal), and

Integrated Member of the Research Centre in Political Science. She holds a Master

of Arts in International Relations from the Graduate Program in International Relations

San Tiago Dantas (UNESP, UNICAMP, PUC-SP) (Brazil), and a bachelor’s degree in International

Relations from the Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (orcid.org/0000-0001-8145-7333). |

| [b] |

PhD Candidate of International relations at the University of Minho (Portugal), and

Integrated Member of the Research Centre in Political Science. She holds a Master

of Arts in International Political Economy from Panteio University, Greece and a bachelor’s

degree in International and European studies from Piraeus University. She has also

been visiting researcher at ICD in Berlin (Germany) and the University of Maribor

(Slovenia) (orcid.org/0000-0001-7672-3342). |