Canaries in a coal mine: The cayuco migrant crisis and the europeanization of migration policy

Canarios en una mina: la crisis migratoria de los cayucos y la europeización de la política migratoria

ABSTRACT

Understanding how the Spanish state and the Canary Islands dealt with the cayuco crisis and its aftermath is instructional for the current migrant crisis facing Europe. Employing the theoretical lenses of liberal intergovernmentalism and neo-institutionalism, this article studies how the EU has shaped the governance of migration policy using both hard and soft governance. Hard governance refers to coercive legally imposed mechanisms, whereas soft governance may be cooperation or voluntary adoption of EU models. During the cayuco crisis, as thousands of African migrants arrived to the Canary Islands, the Spanish government sought assistance from the EU and its member states via Frontex, and adopted the EU’s externalization of migration policy with Plan Africa, an aid package to stop immigration at its source. Both Frontex and Plan Africa were EU policy prescriptions, that exhibit EU soft governance and the Europeanization of migration policy. As a result, Spain achieved its goal of stopping the flow of irregular migrants, yet the state remained the main actor in migration policy, as liberal intergovernmentalists assert. However, the EU-inspired policies that Spain ultimately adopted during the cayuco crisis have been emulated in the current migrant crisis, inspiring a model for present and future migration policies in Europe.

Keywords: migration policy, soft governance, europeanization, Spain, Canary Islands.

RESUMEN

Entender cómo el Estado español y las Islas Canarias lidiaron con la crisis de los cayucos y sus consecuencias es esencial para comprender la actual crisis migratoria a la que se enfrenta Europa. Empleando las lentes teóricas del intergubernamentalismo liberal y el neoinstitucionalismo, este artículo estudia cómo la UE ha configurado la gobernanza de la política migratoria utilizando gobernanza dura y blanda. Gobernanza dura se refiere a los mecanismos coercitivos legalmente impuestos, mientras que la gobernanza blanda puede ser la cooperación o la adopción voluntaria de modelos de la UE. Durante la crisis del cayuco, cuando miles de inmigrantes irregulares africanos llegaron a las Islas Canarias, el Gobierno español buscó el apoyo de los Estados miembro a través de Frontex y adoptó la externalización de la política de migración de la UE con el Plan África, un paquete de ayuda para detener la inmigración en su lugar de origen. Tanto Frontex como el Plan África fueron modelos políticos de la UE, lo que demuestra la gobernanza blanda de la UE y la europeización de la política migratoria. Como resultado, España logró su objetivo de detener el flujo de inmigrantes irregulares, pero el Estado siguió siendo el principal actor en la política migratoria, tal y como afirman los autores intergubernamentales liberales. Sin embargo, las políticas inspiradas en la UE que finalmente adoptó España durante la crisis del cayuco se han emulado en la actual crisis migratoria, inspirando un modelo para las políticas migratorias presentes y futuras en Europa.

Palabras clave: política migratoria, gobernanza blanda, europeización, España, Islas Canarias.

CONTENTS

- Abstract

- Resumen

- INTRODUCTION

- HARD AND SOFT GOVERNANCE: WHAT IS THE EU’S ROLE IN MIGRATION POLICY?

- THE CAYUCO CRISIS

- SOLVING THE CAYUCO CRISIS

- EU AND SPANISH MIGRATION POLICIES: FAILED HARD GOVERNANCE

- IMPORTANT SOFT POWER, THE EXTERNALIZATION OF EU MIGRATION POLICY

- RELATION TO THE CURRENT CRISIS

- CONCLUSION

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Notes

- References

INTRODUCTION[up]

The ongoing migration crisis in Europe, beginning in the summer of 2015, appeared to emerge quite suddenly and the EU and its member states have struggled to process irregular migrants, to provide assistance to these immigrants as EU and international law require, to integrate them into society and to deter their entrance in large numbers. Buonanno ( Buonanno, Laurie. 2017. “The European Migration Crisis”, in Dinan, D., Nugent, N., Paterson, W. E. (eds.), The European Union in Crisis. London: Palgrave.2017) points out that the European Council President Herman Van Rompuy suggested that there were signs of a migration problem in 2013 and 2014, but the cayuco crisis demonstrates that warning signs were even earlier. The cayuco crisis, a mass migration flow from West Africa to the Canary Islands between 2006 and 2009, showed that migration was already increasing at that time and it also provided an example for the EU and its member states of how to respond to such a crisis. Although the current crisis is of a much larger scale and has directly affected more member states, the response to the cayuco crisis offers a model and understanding of policy responses to increased migration flows into Europe.

This article will examine how EU soft governance shaped the migration policy applied in the Canary Islands during the cayuco crisis, and how the Spanish government addressed the crisis adopting EU policy prescriptions to promote development in the countries at the source of migration and to create readmission agreements with countries of origin to stem the migration flow. Spain’s handling of the cayuco crisis demonstrates the Europeanization of migration policy, which has been emulated in the larger current migrant crisis, and has been upheld by public officials as a successful policy initiative[1]. For instance, French Minister of the Interior, Gérard Collomb, explained that the Spanish government’s response to the cayuco crisis stands as an example of how to deal with the current migration from Africa, specifically referring to how Spain created agreements with states of origin, which helped to stop the flow of immigrants and ended the crisis[2].

Crises have shaped how the EU, national and lower levels of government respond to

problems, exacerbating the constant tension about ‘where power lies in the EU system’( Graziano, Paolo and Charlotte Halpern. 2016. “EU governance in times of crisis: Inclusiveness

and effectiveness beyond the “hard” and “soft” law divide”, Comparative European Politics, 14: 1-19. Available at:

The cayuco crisis is of importance since it triggered the first aero-maritime intervention by

the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External

Borders of the Member States of the EU (Frontex). The crisis demonstrated: (1) how

southern European countries experienced greater migration pressures compared to their

northern counterparts, (2) how migrants found new routes as older routes in North

Africa were closed, (3) how Frontex’s actions intercepting migrant filled boats could

be of assistance saving lives, and (4) how the use of bilateral cooperation and development

programs could deter further migration all problems and policy strategies found in

the current migrant crisis ( Finotelli, Claudia. 2018. “Southern Europe: Twenty-five years of immigration control

on the waterfront”, in A. Ripoll Servent and F. Trauner (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Justice and Home Affairs. New York: Routledge.Finotelli, 2018; Finotelli, Claudia and Irene Ponzo. 2017. “Integration in times of economic decline.

Migrant inclusion in Southern European societies: trends and theoretical implications”,

Journal of Ethnic Migration Studies. 44 (14), 2303-2319. Available at:

The article will first examine the EU’s use of hard and soft governance with an examination of neo-institutionalism (the mulit-level governance model and new modes of governance) juxtaposed with liberal intergovernmentalism, and the central role of the state, in shaping migration policy. Next, the cayuco crisis is analysed to demonstrate how the externalization of European migration policy was adopted by the Spanish state to stave off the crisis. The article concludes using the experience of the cayuco crisis as a way of understanding EU policy regarding the recent migrant crisis beginning in 2015.

HARD AND SOFT GOVERNANCE: WHAT IS THE EU’S ROLE IN MIGRATION POLICY?[up]

The notions of EU hard and soft governance are central to understanding how and in

what way does the EU influence policy governance. Governance is “societies’ collective

steering and management” that is constantly changing ( Peters, B. Guy. 2002. Governance: A Garbage Can Perspective. Political Science Series Vienna: Institute for Advanced Studies. Available at:

One perspective within neo-institutionalism is multi-level governance (MLG), that

suggests that the EU adds a supranational layer of government with which national

governments have to share authority in addition to subnational actors, both public

and private ( Hooghe, Liesbet and Gary Marks. 2001. Multi-level Governance and European Integration. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.Hooghe and Marks, 2001; Van Kersbergen, Kees and Francis van Waarden. 2004. “Governance” as a Bridge between

Disciplines. Cross-Disciplinary Inspiration regarding Shifts in Governance and Problems

of Governability, Accountability, and Legitimacy”, European Journal of Political Research, 43 (2): 143-171. Available at:

As Tommel and Verdun ( Tommel, Ingebörg and Amy Verdun. 2013. “Innovative Governance in EU Regional and Monetary

Policy-Making”, German Law Journal, 14: 380-404.2013) and Dehousse ( Dehousse, Renaud. 2016. “Has the European Union moved towards soft governance?”, Comparative European Politics, 14: 20-35. Available at:

A competing perspective, the state-centric or liberal intergovernmentalist perspective,

asserts that states remain central to governance within the EU as European integration

is seen as a succession of bargains among states acting in their rational self-interest

( Moravcsik, Andrew. 2001. “A constructivist research programme for EU studies”, European Union Politics, 2: 219-249.Moravcsik, 2001; Moravcsik, Andrew. 1994. “Why the European Community Strengthtens the State: Domestic

Politics and International Cooperation”, Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association. New York. Available at:

According to both theoretical perspectives, governance can be defined as ‘where power

lies in the EU system…and power is the capacity of actors to obtain decisions that are in line with their preferences’

( Graziano, Paolo and Charlotte Halpern. 2016. “EU governance in times of crisis: Inclusiveness

and effectiveness beyond the “hard” and “soft” law divide”, Comparative European Politics, 14: 1-19. Available at:

The issue about hard and soft governance is related to the question about where power

lies. Soft governance refers to “non-coercive and informal modes of governance” or

NMG, that is, the open method of coordination or relations within policy networks,

which tends to be non-hierarchical and voluntary ( Dehousse, Renaud. 2016. “Has the European Union moved towards soft governance?”, Comparative European Politics, 14: 20-35. Available at:

The single market and the need for the free movement of people and goods to achieve

it, became a fundamental policy area of the EU. However, the movement of people across

borders had been a central policy area of the state, which the EU also needed to regulate

( Guiraudon, Virginie. 2000. “European Integration and Migration Policy: Vertical Policy-making

as Venue Shopping”, Journal of Common Market Studies, 38: 251-271. Available at:

Although Schengen was intended to promote an EU-wide approach to immigration issues,

regarding migration and asylum, the policies of member states, as well as lower levels

of government, as well as non-governmental actors working across all levels of government

have shaped immigration policy and practice ( Guiraudon, Virginie. 2000. “European Integration and Migration Policy: Vertical Policy-making

as Venue Shopping”, Journal of Common Market Studies, 38: 251-271. Available at:

As for soft governance, it can be found in EU policy prescriptions and member state

best practices shared within EU policy networks. Examples of soft mechanisms regarding

migration policy might include the Tampere Council of 1999 or the functioning of Frontex.

The Tampere Council was a special meeting held focusing on the creation of “an area

of freedom, security and justice in the European Union” ( European Parliament. 1999. Tampere European Council 15-16.10.1999: Conclusions of

the Presidency”. Available at:

Related to hard and soft governance, one of the central questions within EU migration

policy is whether or to what extent member states give authority to the EU ( European Commission. 2010. “Schengen: some basic facts”. Press Releases. Available at:

Processes of (a)construction (b) diffusion (c) institutionalization of formal and informal rule, procedures, policy paradigms, styles, ‘ways of doing things’ and shared beliefs and norms which are first defined and consolidated in the making of EU decisions and then incorporated in the logic of domestic discourse, identities, political structures and public policies (p. 4).

Similar to the “second–image reversed” idea which suggests the international system

impacts domestic politics and viceversa, the EU influences what policies member states

adopt, and member states contribute to the shaping of EU policy ( Gourevitch, Peter. 1978. “The Second Image Reversed: The International Sources of

Domestic Politics”, International Organization, 32: 881-912. Available at:

THE CAYUCO CRISIS[up]

Prior to the cayuco crisis, African irregular migrants began arriving on small wooden fishing boats called

pateras. The first patera arrived at Fuerteventura, one of the Eastern islands, in 1994 with two Saharawis on

board. Pateras are very light fishing boats that can barely float in waters with strong ocean currents.

The number of pateras increased as more migrants risked their lives on the perilous journey to the Canary

Islands. The situation worsened as smugglers overloaded the boats. Travelers faced

conditions of hypothermia, dehydration, disease and overcrowding ( Amnesty International. 2006. «Los derechos de los extranjeros que llegan a las Islas

Canarias siguen siendo vulnerados», en Resultado de la misión de investigación de Amnistía Internacional. London: Amnesty International.Amnesty International, 2006; Castellano, Nicolás. 2016. “20 años de inmigración en Canarias”, Cadena Ser. Available at:

The challenging surge of migration began after 2000, when cayucos, larger boats, started to arrive to the Canary shores and the number of migrants increased steadily (Interview with J. Naranjo, held on September 30, 2016). One of the reasons for increased immigration to the Canary Islands in the 90s and 2000s was that Europe had helped to re-enforce the northern enclaves, namely the borders of Ceuta and Melilla in Morocco, as well as the Strait of Gibraltar (Finotelli, 2018; interview with D. Godenau, held on July 6, 2016). As a consequence, migrants were searching for an alternative route to enter Europe.

In response to increased migration to the Canaries, many irregular immigrants were sent to the Spanish peninsula. For instance, the mayor of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria at that time, Jose Manuel Soria, began sending unidentified or un-deportable migrants to mainland Spain (interview with J. Naranjo, held onSeptember 30, 2016). This became known as the “Soria doctrine.” It consisted in sending migrants living on the streets of the municipality of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria to Madrid, so they could be closer to their embassies, in the hope that this would facilitate the normalization of their legal status in Spain or allow them to travel to other European countries[3].

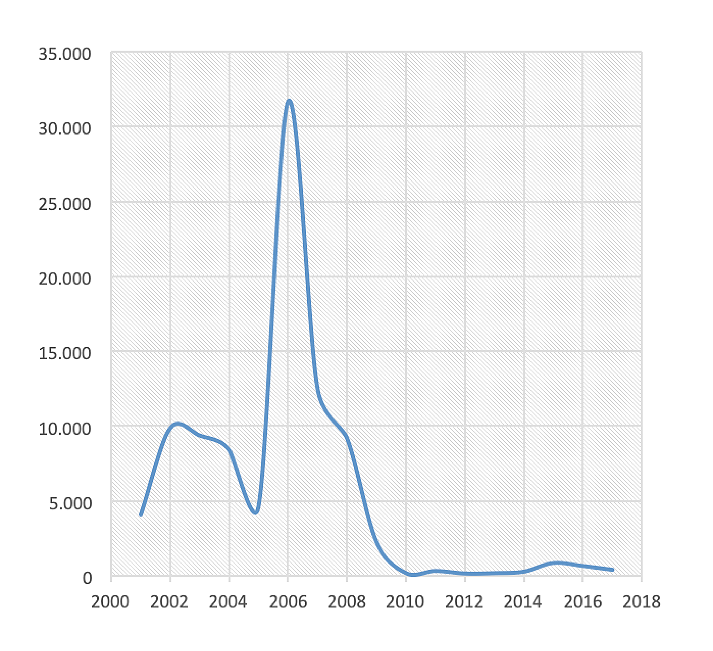

By 2006, the number of immigrants overwhelmed the Island’s border enforcement and

the retention centres where migrants are usually housed. Throughout the 90s, the total

number of migrants who had reached the Canary Islands’ shores was 1000, but in 2006

the number of irregular entries peaked at 31 678 ( Ministerio del Interior. 2016. Inmigración Irregular: balance 2015. Lucha contra la inmigración irregular. Available at:

Chart 1.

Number of irregular entries to the Canary Islands

Sources: Own elaboration with data from Ministerio del Interior: Inmigración irregular: balance 2015. Lucha contra la inmigración irregular [available at: https://bit.ly/2tRJZmH]; Inmigración irregular: balance 2016. Lucha contra la inmigración irregular [available at: https://bit.ly/2T8i6nO]; Inmigración irregular: informe semanal del 25 a 31 de diciembre. Lucha contra la inmigración irregular [available at: https://bit.ly/2n5zcko].

SOLVING THE CAYUCO CRISIS[up]

Irregular migrants fall under EU legislation, specifically Schengen as already mentioned, as well as Spanish legislation. The act that lays out the status, rights and duties of migrants in Spain is the Organic Law 2/2009 on the Rights and Freedoms of Foreigners in Spain and their Social Integration, commonly referred to as the Spanish Aliens Act[4]. It establishes the framework for the treatment of irregular migrants, regulates foreigners’ rights and duties in Spain and contains principles that seek to promote legal immigration, with the goal of restricting to a minimum the entry of irregular migrants. It offers opportunities to immigrants established in Spanish territory in irregular conditions to normalize their situation. As a general rule, this law establishes the recognition of the rights granted by the Spanish Constitution, international treaties interpreted in accordance with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and other existing treaties on citizens’ rights. Thus, although one could argue that Schengen has placed parameters on Spain’s immigration policy, the Aliens Act is a law the Spanish state put into place to establish Spanish rules and norms of immigration beyond the general framework of Schengen. In this way, one might assume that EU hard governance is at work holding Spain accountable for the appropriate treatment of migrants.

During the cayuco crisis, EU soft governance was also applied, which included support by member states via Frontex and also promoting the EU’s externalization of migration policy ( Triandafyllidou, Anna. 2014. “Multi-leveling and externalizing migration and asylum: lessons from the southern European islands”, Island Studies Journal, 6: 7-22.Triandafyllidou, 2014). Externalization of migration policy as prescribed at the Tampere Council included Spain’s adoption of Plan Africa and its signing of repatriation agreements with several African countries including: Algeria, Morocco, Senegal, Mauritania, Gambia, Guinea, Mali and Ghana[5]. EU soft governance, was able to strengthen the central role of the state in dealing with the crisis and achieve Spain’s preferences, stopping the migration, as liberal intergovernmentalists assert.

The cayuco crisis was resolved through the coordinated action of multiple levels of governments

and assistance from NGOs. The institutional framework that structures the governance

of migration policy in Spain includes both the national and regional levels of government.

National government, under the Spanish Ministry of the Interior, handles security,

detention of migrants in the high seas, identification, possible repatriation and

the management of retention centres ( Frontex. 2017. National Authorities. Available at:

On May 21st 2006, in the midst of the cayuco crisis, the Canary Islands government requested the Spanish government to ‘armor the coast’ and in response Spain called for an emergency fund from the European Union[6]. The next day, the Vice-President of Spain, María Teresa Fernández de la Vega, travelled to Brussels to ask for help in controlling irregular migration and securing Spain’s Southern border[7].

The EU’s response, however, was slow and member states such as Germany and the Netherlands

blamed the surge of irregular migrants on Spain’s poor management of their borders

in 2005, whereby 600 000 irregular migrants were allowed to enter ( Monar, Jörg. 2007. “Justice and Home Affairs”, Journal of Common Market Studies, 45: 107-124. Available at:

In response to Spain’s request, member states eventually supported Frontex providing

assistance. Frontex was created in 2004 to ensure European norms on immigration and

border management are followed according to standards of Integrated Border Management

and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU. Frontex lacks its own border guards

and equipment, instead it relies on EU member states to deploy experts and equipment

( Frontex. 2015. Press Pack on the General Migratory Situation at the External Borders of the EU. Available at:

The responsibility for the control and surveillance of external borders lies with

the Member States. The Agency (Frontex) should facilitate the application of existing

and future Community measures relating to the management of external borders by ensuring

the coordination of Member States, actions in the implementation of those measures

( Council of the European Union. 2004. Council Regulation (EC) No 2007/2004 establishing

a European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders

of the Member States of the European Union. Available at:

Frontex’s involvement in the cayuco crisis was really a test case since it was Frontex’s first major joint aero maritime

operation, HERA. The European Parliament passed two plans of action, HERA I and HERA

II, signed in 2006. HERA I consisted of the assistance for surveillance duties in

high seas and identification of migrants. It began on July 17, 2006 when European

countries sent nine experts —more were sent later— to the Canary Islands to help Spanish

authorities identify migrants that had arrived through irregular channels ( Frontex. 2006. “Longest FRONTEX coordinated operation. HERA, the Canary Islands”,

News. Available at:

HERA II expanded efforts with the goal of improving the Spanish authority’s sea surveillance. Beginning on August 11 2006, HERA II included several EU member states sending equipment in order to stop migrants from arriving to the islands. Frontex’s intervention meant a significant decrease in migrants in a short amount of time. HERA I and II were successful because they accomplished the European Union goal, to secure its most southern border from irregular immigration. The Spanish government’s Policía Nacional, working with experts from other countries and using more advanced equipment, managed to identify all 18 987 migrants that arrived to the islands between July 17, 2006 and December 10, 2006 (ibid.). HERA I and II, as a result of the information obtained in the interviewing process of migrants, also facilitated the detention of several smugglers in sub-Saharan Africa, hence decreasing the number of more potential irregular migrants (ibid.).

Frontex’s actions are an example of soft governance and Europeanization. Spain maintains

the competency to protect the integrity of its borders, but as more migrants poured

into the islands or were dying at sea, the Spanish government thought it imperative

to seek the assistance of EU and member state resources. Frontex was designed to create

greater solidarity in the protection of Europe’s borders and depends on the support

of member states and their cooperation with one another ( Frontex. 2018. Origin and Tasks. Available at:

The EU does not require Frontex intervention and Frontex will only act at the behest and with the assistance of member states, thus hard governance does not apply to Frontex action, since there is no legal imperative. However, with member states cooperating via Frontex it created an opportunity for networks of policing forces from other EU countries, EU officials and Spanish policing forces to work together and share knowledge and practices in order to help stave off deaths at sea and to process migrants (Interview with D. Godenau, held on July 6, 2016; interview with a member of the National Police Force, held on August 11, 2016). Here we see the Europeanization of managing border controls as networks of experts in the field were able to share best practices promoting diffusion of implementation ideas, and ‘ways of doing things’ that could be incorporated into public policy implementation ( Radaelli, Claudio. 2000. “Whither Europeanization: Concept Stretching and Substantive Change”, European Integration On-line Papers, 4 (8).Radaelli, 2000).

EU AND SPANISH MIGRATION POLICIES: FAILED HARD GOVERNANCE[up]

Even with the application of Schengen and the constraints EU law places on Spanish

migration laws, EU hard governance was not enough to keep Spain accountable to its

own laws or European ones. The implementation of the Spanish Alien’s Act establishes

the framework for the treatment of irregular immigrants in the Canary Islands. One

of the responsibilities of the state in accordance with Spanish, EU and international

laws is to provide retention centers for immigrants. In the Canary Islands there are

three centers for migrants and national authorities set up another building to contend

with the larger influx of migrants both before and after the cayuco crisis ( Global Detention Project. 2016. Spain: Immigration Detention Profile. Available at:

(Ley Orgánica 4/2000, de 11 de enero, sobre derechos y libertades de los extranjeros

en España y su integración social; Ley Orgánica 2/2009, de 11 de diciembre, sobre

derechos y libertades de los extranjeros en España y su integración social.

Ley Orgánica 4/2000, de 11 de enero, sobre derechos y libertades de los extranjeros

en España y su integración social.

EU and Spanish law provide the framework within which the Spanish state should treat and process migrants. In this way, one might assume that EU hard governance is at work holding Spain accountable for the appropriate treatment of migrants. However, according to a report of Amnesty International in 2006 on the cayuco crisis, the rights of irregular migrants were violated (Amnesty International, 2006). The report denounced the Spanish state for not complying with EU law in accordance with the Charter of Fundamental Rights. Migrants were not informed about their situation once they arrived to the police station, the process of return, nor were they asked if they were at risk in their home countries. As an example, out of 6 908 people that arrived to Tenerife in January-June 2006, only 9 of them applied for asylum (Amnesty International, 2006). Many of them did not know that they could apply for political asylum claiming persecution because of racial or ethnic discrimination, war, homophobia and similar circumstances that certainly are a reality in their countries of origin (ibid.). Also, there was a significant language barrier for migrants. They had access to translators of French and English; however, most reported that their mother tongue was Wolof. Without adequate translators it became virtually impossible for them to understand their rights (ibid.).

Amnesty International ( Amnesty International. 2006. «Los derechos de los extranjeros que llegan a las Islas Canarias siguen siendo vulnerados», en Resultado de la misión de investigación de Amnistía Internacional. London: Amnesty International.2006) also identified that there were not enough resources dedicated to identifying the migrants. It is a challenge for local authorities to guess their nationalities, since migrants might identify themselves more with a tribe or ethnicity that does not necessarily correspond with a state or government authority. Most migrants are identified as Senegalese, since it is in the interest of Spain to identify nationals of countries with which the Spanish government has repatriation treaties, such as Senegal. Furthermore, migrants were not put in contact with attorneys as soon as they arrived at the CIEs. Many migrants reported that they only met their attorneys on the day of the trial, and were not granted a translator (ibid.).

Thus, although the EU’s hard governance set up parameters within which migrants must be treated, the Spanish government did not fully comply, but rather worked within their means or willingness to deal with the migrant crisis irrespective of meeting EU requirements. In this way, although hard governance is technically present, there is a lack of enforcement of EU law. Frontex was able to assist with capturing and processing migrants, but the care of migrants was left to the state and non-state actors such as the Spanish Red Cross and Caritas (a church sponsored organization). The Red Cross and Caritas took the lead in assisting migrants and providing health and social intervention, and yet certain migrant rights were still not fully protected, demonstrating a failure of EU hard governance, in part due to the lack of resources and EU oversight during the crisis. As has been demonstrated with the current crisis, similar issues regarding the violation of migrants’ rights as the EU has limited oversight and mechanisms to force compliance on the ground. Examples of countries violating EU law include Germany’s ignoring of the Dublin Agreement requiring registration at the country of origin and Hungary constructing a border wall with other member states.

IMPORTANT SOFT POWER, THE EXTERNALIZATION OF EU MIGRATION POLICY[up]

An integral part of decreasing the number of African migrants arriving to the Canary

Islands shores was the externalization of EU migration policy ( Triandafyllidou, Anna. 2014. “Multi-leveling and externalizing migration and asylum:

lessons from the southern European islands”, Island Studies Journal, 6: 7-22.Triandafyllidou, 2014). In 1999, the externalization of EU migration policy found strong support from the

European Council and at the Tampere meeting in 1999, “partnership with the country

of origin” became a major goal of the Council regarding Common Asylum and Migration

Policy ( European Parliament. 1999. Tampere European Council 15-16.10.1999: Conclusions of

the Presidency”. Available at:

Similar to the Tampere Council conclusions, Spain also created an Official Development Aid Plan referred to as Plan Africa. Plan Africa was a development program with several migrants’ home countries which included the opening of new embassies on the continent and the promotion of trade relations with the migrants’ main countries of origin to improve their economies. Approved for 2006-2008, Plan Africa was not simply a development plan to improve living conditions in Saharan Africa, but a plan to increase Spanish influence in specific African countries, and to prevent irregular migration to the Canary Islands. The plan was based around seven objectives: contributing to the consolidation of democracy; fighting against poverty; promoting cooperation to regulate migration flows; participating in the development of an EU’s strategy towards Africa; strengthening economic exchanges and encourage investment — especially in relation to energy security and hydrocarbons; encouraging cultural cooperation; and increasing the institutional presence of Spain ( Alcalde, Ana. 2007. “The Spanish Action Plan for Africa”. Review of African Political Economy, 34 (111): 194-198.Alcalde, 2007).

Mauritania’s outcome with Plan Africa is particularly noteworthy since it was successful

in its goal of stopping irregular migration. As part of Plan Africa, members of the

Spanish National Police and another group of Spanish Civil Guards travelled to Mauritania

to partner with a group of Mauritanian state policemen. In addition, Spain also assisted

in strengthening the Mauritanian’s national police providing some equipment Peregil, Francisco. 2015. «Así se detuvo el éxodo de migrantes en cayucos desde África

occidental», EL PAÍS. Available at:

Id.

Plan Africa is a result of EU soft governance. Using the policy ideas of the Tampere Council and EU initiatives, Spain created a similar program to combat migration at its source using development and enhancing policing capabilities within the home countries of migrants. Plan Africa, coupled with assistance from Frontex were both sources of EU soft governance that strengthened the Spanish state’s ability to stave off migration and to end the cayuco crisis. In the end, Spain was able to achieve its preferences, lessening migration, thus strengthening the states governance over migration supporting a more liberal-intergovernmentalist perspective as it relates to migration policy, but at the same time adopting EU policy prescriptions voluntarily or a Europeanization of EU governance using soft governance supporting the assertions of neo-institutionalists.

RELATION TO THE CURRENT CRISIS[up]

The response to the cayuco crisis and its aftermath sheds light on how Europeanization of EU migration policy

has been applied to the current migrant crisis, as well as how neo-institutional and

liberal intergovernmental assertions relate to migration policy. The Spanish response

to the cayuco crisis was Plan Africa, which clearly constituted a form of EU soft governance. Although

the state remained the main actor, Spain adopted the EU policy prescriptions to set

up a developmental program and a relationship with several African countries that

were major countries of origin, such as Senegal and Mauritania. Likewise, in response

to the migrant crisis that emerged in 2015 throughout Europe, the EU established an

agreement with Turkey —the EU-Turkey Joint Action Plan and Turkey Facilitation— to

stop migrants from leaving Turkish refugee camps. Unlike the Spanish Plan Africa,

the agreement with Turkey was a European one, although made at the behest of Germany.

This agreement provides financial assistance to Turkey to fund the refugee camps It began in 2015, when Turkey received 3 billion euros; this increased to 6 billion

in 2016; payments continued until 2018.

In addition, the EU has created regional trust funds to deal with both the influx

of Syrian and African migration. The EU Regional Trust Fund in Response to the Syrian

Crisis is voluntarily funded by twenty two member states and the EU, amounting to

1.4 billion euro to assist refugees in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey with humanitarian

and non-humanitarian needs such as “basic education and child protection, training

and higher education, access to healthcare, infrastructure and economic opportunity”

( European Commission. 2016. “EU Regional Trust Fund in Response to the Syrian Crisis

- European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations: EU Regional Trust Fund

in Response to the Syrian Crisis”, European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations. Available at:

In the current migrant crisis, we see in a sense the “double image reversed” and it being reflected back again. During the cayuco crisis the Spanish state adopted EU policy prescriptions and in the current crisis, states are calling on the EU to follow similar measures including providing aid at the source of migration in addition to member state financial contributions, and shoring up Europe’s borders with Frontex, as was done during the cayuco crisis. Member states have remained central actors in the current crisis limiting a European response to a European problem that has “structural inequalities and asymmetric shocks” ( Cornelisse, Galina. 2014. “What’s wrong with Schengen? Border Disputes and the Nature of Integration in the Area without Internal Borders”, Common Market Law Review, 51 (3): 741-70.Cornelisse, 2014: 12).

CONCLUSION[up]

The cayuco crisis and its aftermath demonstrate how the EU can shape migration policy by utilizing both hard and soft governance mechanisms. During that crisis, Schengen and its requirements to create common standards to people crossing Europe’s borders framed the parameters within which the Spanish government could act. However, with the lack of EU enforcement mechanisms and such a large influx of migrants in a short period of time, meeting the requirements of Schengen were not fully adhered to ( Amnesty International. 2006. «Los derechos de los extranjeros que llegan a las Islas Canarias siguen siendo vulnerados», en Resultado de la misión de investigación de Amnistía Internacional. London: Amnesty International.Amnesty International, 2006). On the other hand, EU soft governance in accordance with ideals from the Tampere Council of 1999 and with the creation of Frontex assisted in staving off the migration crisis. The externalization of migration policy, that was adopted from EU practices first espoused in the Tampere Council in 1999, helped shape the response to the stark increase in immigrants to the Canary Islands. Spain implemented repatriation agreements coordinated policing efforts with African countries and provided development programs, and was thus able to stop immigration at its point of origin, which was its governance goal to stave off west African migration. In addition, Spain requested the assistance from Frontex, which is dependent on the will and contributions of other member states. The European policing and border control networks assisted in intercepting boats at sea and capturing smugglers (Member of National Police, interview, August 11 2016).

The cayuco crisis informs our understanding of how the EU can shape migration policy. Although Schengen with hard governance sets parameters for what member states can and cannot do regarding migration policy, it is also clear that member states do not always fulfil their legal obligations. However, soft governance, in the form of Plan Africa and Frontex intervention, became instrumental bringing an end to the cayuco crisis. The europeanization of migration policy, or the adoption by Spain of ideals that were initially EU policy prescriptions, including the externalization of migration policy, was voluntarily applied to the crisis. Thus, EU soft governance shaped Spain’s response to the migration crisis as neo-instutitionalists would assert, but Spain remained the main actor as liberal intergovernmentalists claim.

Looking at the current migration crisis, EU member states and European institutions have followed a similar model to the one used in the cayuco crisis. First of all, Frontex has again been brought in to help migrants at sea and to secure Europe’s maritime borders; second of all, the externalization of migration policy with an agreement with Turkey that is similar to Plan Africa, without the capability of dealing directly with the country of origin, namely Syria. Although the EU has attempted to implement quotas to more equitably spread the burden of immigration across Europe and to institute hard governance in the current migrant crisis, the EU has failed because it lacks mechanisms to enforce compliance while member states refuse to follow its mandates. Thus, states remain the main actors shaping implementation of migration policy, just as Spain did during the cayuco crisis.

As immigrants continue to come to Europe’s shores, asymmetries of the impact between north and south will continue. However, the ideals from the Tampere Council, which shaped the response to the cayuco crisis and its positive outcome reducing immigration have inspired similar policies in the current crisis, suggesting that although member states continue asserting themselves, the soft governance of Europeanization does play an important role in the governance of migration policy across EU member states.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS[up]

The field research to complete this project was generously funded by Hofstra University’s Faculty Research and Development Grant and the Bernard Firestone Fellowship for undergraduate research.

Notes[up]

| [1] |

Efe. 2017. «Francia pone el caso de Canarias como ejemplo ante la inmigración de África», El Diario. Available at: https://bit.ly/2VwznE8. |

| [2] |

Id. |

| [3] |

ABC. 2002. «El PSOE adopta la “doctrina Soria” sobre el traslado de inmigrantes irregulares». Available at: https://bit.ly/2BZHUIr. |

| [4] |

Ley Orgánica 2/2009, de 11 de diciembre, sobre derechos y libertades de los extranjeros en España y su integración social. |

| [5] |

BBC. 2007. «Spain begins anti-migration ads». Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7004139.stm |

| [6] |

El Mundo Agencias. 2006. «De la Vega viaja hoy a Bruselas para reclamar ayuda ante la crisis migratoria de Canarias». Available at: http://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2006/05/23/espana/1148357662.html. |

| [7] |

Some scholars of MLG suggest that often times regional governments circumvent the state and interact directly with the EU ( Hooghe, Liesbet and Gary Marks. 2001. Multi-level Governance and European Integration. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.Hooghe and Marks, 2001), but in this instance, the state intervened at the request of the Autonomous Community, and sought assistance at the EU level. |

| [8] |

(Ley Orgánica 4/2000, de 11 de enero, sobre derechos y libertades de los extranjeros en España y su integración social; Ley Orgánica 2/2009, de 11 de diciembre, sobre derechos y libertades de los extranjeros en España y su integración social. |

| [9] |

Ley Orgánica 4/2000, de 11 de enero, sobre derechos y libertades de los extranjeros en España y su integración social. |

| [10] |

Peregil, Francisco. 2015. «Así se detuvo el éxodo de migrantes en cayucos desde África occidental», EL PAÍS. Available at: https://bit.ly/2Ub8lSm. |

| [11] |

Id. |

| [12] |

It began in 2015, when Turkey received 3 billion euros; this increased to 6 billion in 2016; payments continued until 2018. |

References[up]

|

Alcalde, Ana. 2007. “The Spanish Action Plan for Africa”. Review of African Political Economy, 34 (111): 194-198. |

|

|

Amnesty International. 2006. «Los derechos de los extranjeros que llegan a las Islas Canarias siguen siendo vulnerados», en Resultado de la misión de investigación de Amnistía Internacional. London: Amnesty International. |

|

|

Asín Cabrera, María. 2007. «Menores extranjeros: artículo 92: menores extranjeros no acompañados. Artículo 93: desplazamiento temporal de menores extranjeros. Artículo 94: residencia del hijo de residente legal», en Margarita Isabel Ramos Quintana y Gloria Pilar Rojas Rivero (coords.), Comentarios al Reglamento de extranjería. Madrid: Lex Nova. |

|

|

Bach, Tobias., Eva Ruffing and Kutsal Yesilkagit. 2015. “The Differential Empowering Effects of Europeanization on the Autonomy of National Agencies”, Governance, 28: 285-304. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12087. |

|

|

Bevir, Mark. 2008. “What is Governance? Key Concepts in Governance”. Los Angeles: Sage. |

|

|

Buonanno, Laurie. 2017. “The European Migration Crisis”, in Dinan, D., Nugent, N., Paterson, W. E. (eds.), The European Union in Crisis. London: Palgrave. |

|

|

Carrera, Sergio, Jennifer Allsopp. 2018. “The Irregular Immigration Policy Conundrum: Problematizing “effectiveness” as a frame for EU criminalization and expulsion policies”, in Ripoll Servent, A., Trauner, F. (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Justice and Home Affairs Research. New York: Routledge. |

|

|

Castellano, Nicolás. 2016. “20 años de inmigración en Canarias”, Cadena Ser. Available at: http://cadenaser.com/especiales/seccion/espana/2014/inmigracion-canarias/. |

|

|

Caviedes, Alexander. 2017. “European Immigration and Asylum Policy”, in The Routledge Handbook of European Public Policy. New York: Routledge. |

|

|

Cornelisse, Galina. 2014. “What’s wrong with Schengen? Border Disputes and the Nature of Integration in the Area without Internal Borders”, Common Market Law Review, 51 (3): 741-70. |

|

|

Council of the European Union. 2004. Council Regulation (EC) No 2007/2004 establishing a European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union. Available at: https://bit.ly/2TaslrS. |

|

|

Dehousse, Renaud. 2016. “Has the European Union moved towards soft governance?”, Comparative European Politics, 14: 20-35. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2015.7. |

|

|

European Commission. 2010. “Schengen: some basic facts”. Press Releases. Available at: https://bit.ly/2C4cLn3. |

|

|

European Commission. 2016. “EU Regional Trust Fund in Response to the Syrian Crisis - European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations: EU Regional Trust Fund in Response to the Syrian Crisis”, European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations. Available at: https://bit.ly/2kCJgin. |

|

|

European Commission. 2017. “The EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa-International Cooperation and Development”, International Cooperation and Development. Available at: https://bit.ly/1NwTlU6. |

|

|

European Parliament. 1999. Tampere European Council 15-16.10.1999: Conclusions of the Presidency”. Available at: https://bit.ly/2H9vAZu. |

|

|

European Parliament Think Tank. 2017. EU accession to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Available at: https://bit.ly/2Jexp5n. |

|

|

Finotelli, Claudia and Irene Ponzo. 2017. “Integration in times of economic decline. Migrant inclusion in Southern European societies: trends and theoretical implications”, Journal of Ethnic Migration Studies. 44 (14), 2303-2319. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1345830. |

|

|

Finotelli, Claudia. 2018. “Southern Europe: Twenty-five years of immigration control on the waterfront”, in A. Ripoll Servent and F. Trauner (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Justice and Home Affairs. New York: Routledge. |

|

|

Frontex. 2006. “Longest FRONTEX coordinated operation. HERA, the Canary Islands”, News. Available at: https://bit.ly/2tMXTVv. |

|

|

Frontex. 2015. Press Pack on the General Migratory Situation at the External Borders of the EU. Available at: https://bit.ly/2Uhsxlw. |

|

|

Frontex. 2017. National Authorities. Available at: https://bit.ly/2VwmUAe. |

|

|

Frontex. 2018. Origin and Tasks. Available at: https://bit.ly/2HbsJPE. |

|

|

Global Detention Project. 2016. Spain: Immigration Detention Profile. Available at: https://bit.ly/2gkrHDo. |

|

|

Godenau, Dirk and Ana López Sala. 2016. “Non-State Actors and Migration Control in Spain. A Migration Industry Perspective”. The Futures we want: Global Sociology and the Struggles for a Better World. 3rd ISA Forum of Sociology, July 10-14, Vienna, Austria, 2016. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10261/136847. |

|

|

Gourevitch, Peter. 1978. “The Second Image Reversed: The International Sources of Domestic Politics”, International Organization, 32: 881-912. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081830003201X. |

|

|

Graziano, Paolo and Charlotte Halpern. 2016. “EU governance in times of crisis: Inclusiveness and effectiveness beyond the “hard” and “soft” law divide”, Comparative European Politics, 14: 1-19. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2015.6. |

|

|

Green Cowles, Maria, James Caporaso and Thomas Risse. 2001. Transforming Europe, Europeanization and Domestic Change. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. |

|

|

Guiraudon, Virginie. 2000. “European Integration and Migration Policy: Vertical Policy-making as Venue Shopping”, Journal of Common Market Studies, 38: 251-271. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00219. |

|

|

Guiraudon, Virginie. 2018. “The 2015 refugee crisis was not a turning point: explaining policy inertia in EU border control”, European Political Science, 17: 151-160. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-017-0123-x. |

|

|

Hooghe, Liesbet and Gary Marks. 2001. Multi-level Governance and European Integration. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield. |

|

|

Majone, Giandomenico. 1999. “The regulatory state and its legitimacy problems”, West European Politics, 22: 1-24. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/014023 89908425284. |

|

|

Marks, Gary. 1993. “Structural Policy and Multilevel Governance in the EC”, in Alan Cafrun and Glenda Rosenthal (eds.), The State of the European Community: The Maastricht Debates and Beyond. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. |

|

|

Menz, Georg. 2010. “Stopping, Shaping and Moulding Europe: Two Level Games, Non-State Actors and the Europeanization of Migration Policies”, Journal of Common Market Studies, 49: 437-462. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02123.x. |

|

|

Ministerio del Interior. 2016. Inmigración Irregular: balance 2015. Lucha contra la inmigración irregular. Available at: https://bit.ly/2tRJZmH. |

|

|

Monar, Jörg. 2007. “Justice and Home Affairs”, Journal of Common Market Studies, 45: 107-124. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2007.00738.x. |

|

|

Moravcsik, Andrew. 1994. “Why the European Community Strengthtens the State: Domestic Politics and International Cooperation”, Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association. New York. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116501002002004. |

|

|

Moravcsik, Andrew. 2001. “A constructivist research programme for EU studies”, European Union Politics, 2: 219-249. |

|

|

Mungianu, Roberta. 2013. “Frontex: Towards a Common Policy on External Border Control”, European Journal of Migration and Law, 15: 359-385. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1163/15718166-00002041. |

|

|

Peters, B. Guy. 2002. Governance: A Garbage Can Perspective. Political Science Series Vienna: Institute for Advanced Studies. Available at: https://bit.ly/2EHfrJ9. |

|

|

Pierre, Jon and B. Guy Peters. 2005. “Multilevel Governance: A Faustian Bargain?”, in Governing Complex Societies: Trajectories and Scenarios. London: Palgrave Macmilan. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230512641_5. |

|

|

Radaelli, Claudio. 2000. “Whither Europeanization: Concept Stretching and Substantive Change”, European Integration On-line Papers, 4 (8). |

|

|

Ripoll Servent, Ariadna and Floriant Trauner (eds.). 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Justice and Home Affairs Research. New York: Routledge. |

|

|

Rosenow, Kerstin. 2009. “The Europeanization of Integration Policy”, International Migration, 47: 131-159. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2008.00499.x. |

|

|

Schain, Martin. 2009. “The State Strikes Back: Immigration Policy in the European Union”, The European Journal of International Law, 20: 93109. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chp001. |

|

|

Schmitter, Philippe C. 1970. “A Revised Theory of Regional Integration”, International Organization, 24: 836-868. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300017549. |

|

|

Smith, Andy. 2003. “Multi-Level Governance: What it is and How it Can Be Studied”, in Handbook of Public Administration. London: SAGE. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848608214 |

|

|

Tommel, Ingebörg and Amy Verdun. 2013. “Innovative Governance in EU Regional and Monetary Policy-Making”, German Law Journal, 14: 380-404. |

|

|

Tosun, Jale, Anna Wetzel and Galina Zapryanova. 2014. “The EU in Crisis: Advancing the Debate”, Journal of European Integration, 36: 195-211. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2014.886401. |

|

|

Triandafyllidou, Anna. 2014. “Multi-leveling and externalizing migration and asylum: lessons from the southern European islands”, Island Studies Journal, 6: 7-22. |

|

|

Van Kersbergen, Kees and Francis van Waarden. 2004. “Governance” as a Bridge between Disciplines. Cross-Disciplinary Inspiration regarding Shifts in Governance and Problems of Governability, Accountability, and Legitimacy”, European Journal of Political Research, 43 (2): 143-171. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2004.00149.x. |

Biography[up]

| [a] |

Professor and Chair of Political Science and Director of European Studies at Hofstra

University. She received her Ph.D. and M.A. in Political Science from the University

of Pittsburgh. Professor Dudek has been awarded several fellowships including a Jean

Monnet Fellowship at the European University Institute and two Fulbright Scholarships

to Spain and Argentina. Her field research in Europe and Latin America has resulted

in publications on EU cohesion policy, regional economic development in Spain, EU-US

food regulations and trade, EU-Latin American relations, regional nationalism in Europe

and migration policy. |

| [b] |

Received her bachelors degree in Political Science from Hofstra University. While

at Hofstra University, she was awarded the Bernard Firestone Fellowship. In addition,

Pestano has received two consecutive excellence scholarships for post graduate studies

from the government of the Canary Islands. She is currently a masters student of European

Affairs at Sciences Po Paris. |