Dual identity? A methodological critique of the Linz-Moreno question as a statistical proxy of national identity

¿Identidad dual? Una crítica metodológica a la pregunta Linz-Moreno como indicador estadístico de la identidad nacional

ABSTRACT

This article develops a methodological critique of a widespread measurement of national identity through surveys, the so-called “Linz-Moreno question” (LMQ) and of its epistemological foundation, the theory of “dual identity”. We chose Spain as a case study for our research because of its internal variability in terms of identity feelings between its regions and the availability of quality data. We have divided the seventeen Spanish Autonomous Communities (ACs) into four groups, in accordance to their identity structure. We present two big groups of ACs, one including the ACs with primacy of nationwide nationalistic feelings, and the other one containing those ACs with significant presence of sub-state nationalisms. Then, we divide each of these categories into two, attending to the strength of their identity feelings. Using qualitative methodologies, we found differences in the reproduction process of nationalism for each group of ACs, what strengthens the validity of our classification. Finally, we tested our main hypothesis with a multinomial logistic regression that provides empirical evidence showing that the LMQ is not a good indicator of national identity for weakly nationalized ACs. We conclude that the dual identity theory hides relevant differences related to the hierarchy and nature of collective identities in modern societies. Consequently, we should problematize merely descriptive analyses of collective identities and begin to treat national identity as an ideological expression of nationalism. The critique of the LMQ presented in this article wants to contribute to a better measurement of identities in modern societies.

Keywords: nationalism, autonomous communities, Spain, Linz-Moreno question, national identity, dual identity.

RESUMEN

Este artículo ofrece una crítica metodológica a una medición generalizada de la identidad nacional a través de encuestas, la llamada «pregunta Linz-Moreno» (PLM), y a su fundamento epistemológico, la teoría de la «identidad dual». Elegimos España como caso de estudio para nuestra investigación dada la variabilidad interna en términos de identidad entre sus regiones y la disponibilidad de datos sólidos. Dividimos sus diecisiete comunidades autónomas (CC. AA.) españolas en cuatro grupos, en función de su estructura identitaria. Presentamos dos grandes grupos de CC. AA., incluyendo en el primero las CC. AA. donde priman sentimientos nacionalistas de ámbito estatal, y en el segundo aquellas con una presencia significativa de nacionalismos subestatales. A continuación, dividimos cada una de estas categorías en dos, atendiendo a la fortaleza de sus sentimientos identitarios. Utilizando metodologías cualitativas, hallamos diferencias en el proceso de reproducción del nacionalismo para cada grupo de CC. AA., lo que refuerza la validez de nuestra clasificación. Por último, probamos nuestra hipótesis principal con una regresión logística multinomial, que proporciona evidencia empírica que demuestra que la PLM no es un buen indicador de identidad nacional para aquellas CC. AA. débilmente nacionalizadas. Concluimos que la teoría de la identidad dual oculta diferencias significativas en cuanto a la jerarquía y naturaleza de las identidades colectivas en sociedades modernas. Por ello, optamos por problematizar el análisis meramente descriptivo de las identidades colectivas y comenzar a tratar la identidad nacional como expresión ideológica del nacionalismo. La crítica de la PLM presentada en este artículo quiere contribuir a una mejor medición de las identidades en las sociedades modernas.

Palabras clave: nacionalismo, comunidades autónomas, España, pregunta Linz-Moreno, identidad nacional, identidad dual.

INTRODUCTION[up]

There are few social phenomena as reluctant to be studied under the rigorousness of

the scientific method as national identity. The embeddedness within the realm of the

doxa, in its twofold Platonian significance of pistis and eikasia ( Plato. 1968 [380BC]. Republic (Vol. VI). New York: Harper Collins.Plato, 1968 [380BC]), of national identity is perhaps better understood when we compare its scientific

development with another old, politically loaded, concept like social class, during

the last one hundred years of modern social science. Thus, if we observe two of the

most widely respected compilations of the state-of-the-art regarding social class

and national identity, Wright ( Wright, Erik O. 2005. Approaches to Class Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at:

The relevance of national identity in contemporary societies is also undeniable. It

was at the core of the 2014 Scottish independence referendum ( Mullen, Tom. 2014. “The Scottish Independence Referendum 2014”, Journal of Law and Society, 41 (4): 627-640. Available at:

This article aims to draw upon the path opened by the LMQ, in order to further strengthen

the methodological tools at our disposal, which are, as Goldthorpe ( Goldthorpe, John H. 2000. On Sociology. Numbers, Narratives, and the Integration of Research and Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.2000) insistently states, at the core of any scientific advancement. This task seems particularly

urgent today, when national identity is at the core of the issues defining the impact area of political communication ( Bouza, Fermín. 2004. “The Impact Area of Political Communication: Citizenship Faced

with Public Discourse”, International Review of Sociology, 14 (2): 245-259. Available at:

This article is divided into 5 sections; first, it presents the objectives, hypothesis, and data used, featuring a detailed discussion of the LMQ and of the dual identity approach that usually underpins the interpretations of the LMQ. This presentation is followed by a descriptive analysis of the structure of identity feelings for each AC, using data gathered by the CIS. Based on this descriptive analysis, the article then offers a qualitative analysis of the press, the results of which are aligned with our initial hypotheses. Finally, we present a quantitative analysis of the data based on a multinomial logistic regression using data of CIS’ study 2956, Barómetro Autonómico III. The results of the qualitative and quantitative analyses and their successful alignment with our key hypotheses are discussed in the conclusions.

OBJECTIVES, HYPOTHESIS AND DATA[up]

Agreeing with Merton’s statement that “establishing the phenomenon” is the most important

prerequisite preceding any scientific analysis ( Merton, Robert K. 1987. “Three Fragments from a Sociologist’s Notebooks: Establishing

the Phenomenon, Specified Ignorance, and Strategic Research Materials”, Annual Review of Sociology, 13 (1): 1-28. Available at:

We will follow here the terminology established by Moreno and McEwen ( Moreno, Luis and Nicola McEwen. 2005. “Exploring the territorial politics of welfare”, in Nicola McEwen and Luis Moreno (eds.), The territorial politics of welfare. Oxon/New York: Routledge.2005) for the description of the different levels as state-wide and sub-state, as we consider this terminology more accurate and value-free than others, such as “regional/national”. The LMQ establishes five categories to complete the sentence “Do you see yourself as…”:

1/ [sub-state identity] only.

2/ More [sub-state identity] than [state-wide identity].

3/ Equally [sub-state identity] and [state-wide identity].

4/ More [state-wide identity] than [sub-state identity].

5/ [state-wide identity] only.

When applied to Spain, the LMQ takes as sub-state identities those associated to each

one of the seventeen Autonomous Communities (ACs) in which Spain’s territory is divided.

Some ACs have long traditions and historical content, while others were designed ex novo as part of the so-called café para todos (coffee for all) policy, which was at the core of the 1978 Spanish territorial design

( Tusell, Javier. 1997. Historia de España (Vol. XII). Madrid: Espasa Calpe.Tusell, 1997). In Spain, however, we find different national projects; from the advanced nation-building

processes taking place in the Basque Country and Catalonia, to the relatively underdeveloped

nation-building processes in other areas like Galicia ( Martinez-Herrera, Enric. 2002. “From nation-building to building identification with

political communities: Consequences of political decentralization in Spain, the Basque

Country, Catalonia and Galicia, 1978-2001”, European Journal of Political Research, 41, (4): 421-453. Available at:

Our objective is to determine the validity of the LMQ as a proxy variable to measure national identity, regardless of the degree of nationalist consolidation that characterizes the society under examination. Our main hypothesis here is that the LMQ is a good indicator of national identity when applied to societies featuring strong sub-state nation building processes, such as Scotland, but it faces some relevant analytical problems when applied to places where these processes were not so strongly developed, like Galicia.

We find the epistemological foundations of the LMQ in the theory of dual identity

( Moreno, Luis. 1988. “Scotland and Catalonia: the path to home rule”, in David McCrone,

and Alice Brown (eds.), Scottish Government Yearbook 1988. Edinburgh: Unit for the Study of Government in Scotland.Moreno, 1988; Moreno, Luis and Ana Arriba. 1996. “Dual Identity In Autonomous Catalonia”, Scottish Affairs, 17 (1): 78-97. Available at:

To summarize the basic reason for this problematization of the concept of dual identity, it could be said that single individuals do, in fact, identify themselves with multiple identities on everyday life —woman, teacher, sister, Catalan, etc.— but this fact does not mean that these different identities are all of them on the same layer of social reality. In social sciences, it is well established that the identities assumed by individuals are necessary for the development of social interaction ( Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books.Goffman, 1959) framed within a network of power relations and capital circulation ( Bourdieu, Pierre. 2012. Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. London: Routledge.Bourdieu, 2012) which are at the core of the formation of human practices ( Bourdieu, Pierre. 1987. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Bourdieu, 1987). This amounts to say that identities can be seen as a resource at the disposal of individuals so that they are able to build up the subjectivity inherent and constitutive of social relations. Such a process, however, is only possible if there is a functional differentiation between the different identities available to each set of social positions. Hence, associations between subjects and identities are not dual but presumably multiple, depending on the synchronic characteristics of social fields, as Moreno himself has argued ( Moreno, Luis. 2004. “Identidades múltiples y mesocomunidades globales”, in Francesc Morata, Guy Lachapelle and Stéphane Paquin (eds.), Globalización, gobernanza e identidades. Barcelona: Fundació Carles Pi Sunyer d’Estudis Autonòmics i Locals.Moreno, 2004).

In order to make our point clearer, we summarize some of the knowledge produced within

the academic sub-discipline of nationalist studies, with no intention of presenting

an exhaustive review of the huge volume of social scientific literature on the topic,

which, as Rogers Brubaker pointed out “has become unsurveyably vast” ( Brubaker, Rogers. 2009. “Ethnicity, Race, and Nationalism”, Annual Review of Sociology, 35: 21-42. Available at:

Differences between a national, standardized language and pre-national forms of talk

were thoroughly commented by Billig ( Billig, Michael. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: Sage Publications.1995: 13-36), who coined the term “syntax of hegemony” (ibid.: 87), referring to the metonymic process by which a part of a nation’s cultural mosaic

claims to represent the whole. Billig uses this concept to analyze the construction

of national languages, when a particular dialect becomes the national language in

a process linked to power dynamics; in Billig’s words: “The middle class of metropolitan

areas typically will make their meanings stick as the official language, relegating

other patterns within the national boundaries to ‘dialects’, a term which almost invariably

carries a pejorative meaning” (ibid.: 32). In fact, the term dialect has been problematized a number of times, as it usually

involves not only a descriptive scientific definition on the natural variation characterizing

languages, but also differences regarding the status of each of these varieties —see

Haugen ( Haugen, Einar. 1966. “Dialect, Language, Nation”, American Anthropologist, 68 (4): 922-935. Available at:

Differences between pre-national diacritics and standardized national forms do not

only apply to languages, but also to whichever ethnic diacritic susceptible of being

integrated in the nation-building process in the form of differential facts. This

matrix is first developed within the limits of the intellectual field ( Hroch, Miroslav. 1985. Social Preconditions of National Revival in Europe: A Comparative Analysis of the

Social composition of Patriotic Groups among the Smaller European Nations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Hroch, 1985) which, as a subfield dependent on the broader field of political power ( Bourdieu, Pierre. 1971. “Champ du pouvoir, champ intellectuel et habitus de classe”.

Scoliès. Cahiers de recherche de l’Ecole normale supérieure, 1: 7-26.Bourdieu, 1971), cannot be independent from the socio-political context; or, as McCrone puts it,

“being able to show that there is ethnic homogeneity in a given territory —or, rather,

that people living there believe themselves to be homogeneous— is the outcome of political

and social processes, not their explanation, their cause” ( McCrone, David. 2001. “Who Are We? Understanding Scottish Identity”, in Catherine

Di Domenico, Alexander Law, Jonathan Skinner and Mick Smith (eds.), Boundaries and Identities: Nation, Politics and Culture in Scotland. Dundee: University of Abertay Press.McCrone, 2001: 23; see also Stavenhagen, Rodolfo. 1996. Ethnic Conflicts and the Nation-State. London: Macmillan. Available at:

In other words, the development of a sub-state national identity induces two opposing

phenomena: the growth of a concordant regional identity in unnationalized parts of

the community, and a reaction reaffirming the national-state identity in other portions

as well as among the population outside this community. In terms of identities, the region in question is divided, as it were, into three

persuasions: two are built around the same specific ethnicity but in different degrees

(a national sub-state versus a simple regional identity), and the third is centered on the national-state identity” ( Beramendi, Justo G. 1999. “Identity, ethnicity and state in Spain: 19th and 20th centuries”,

Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 5 (3-4): 79-100. Available at:

There is no possible analytical way of discerning the first two identities referred to by Beramendi if we only take into account the five categories of the LMQ, as each of these become a bucket where fundamentally different identities coexist. This impossibility of the LMQ to differentiate regional from national identities might lead to misconceptions; for instance Table 1 uses the examples of Catalonia and Galicia to show how the same responses to the LMQ are associated to different national identifications in strongly and weakly nationalized ACs.

Table 1.

Meaning of Spain for respondents of the LMQ

| Galician Only | Catalan Only | More Galician than Spanish | More Catalan than Spanish | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain is my country | 16.8 % | 5.6 % | 51.0 % | 13.5 % |

| A nation of which I am a member | 8.5 % | 1.4 % | 11.2 % | 10.1 % |

| The State of which I am a citizen | 27.9 % | 9.7 % | 23.4 % | 25.1 % |

| A State made up of several nationalities and regions | 10.8 % | 26.5 % | 11.8 % | 40.8 % |

| An alien State, to which my country does not belong | 30.8 % | 52.5 % | 0.6 % | 7.0 % |

Source: CIS’ Autonomic Barometer III (Study 2956, for year 2012).

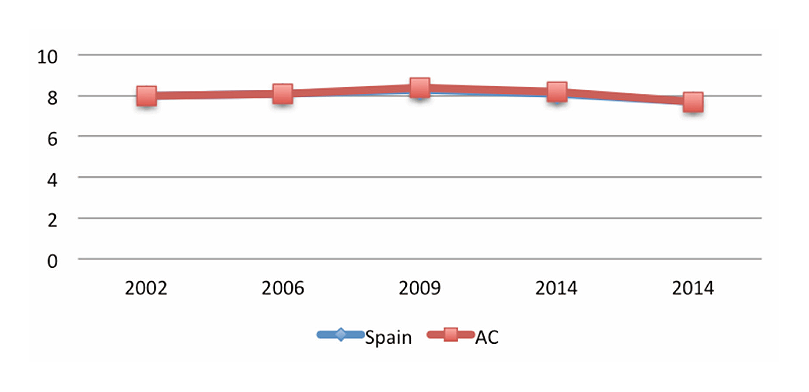

Even if we consider the neo-institutionalist perspective, according to which weak sub-state identities could have been boosted after more than three decades of autonomic system, the LMQ continues to suffer from the same impossibility to differentiate regional vs. national identities. In addition, the identification with the ACs in Spain is rather stable and shares values and synchronic evolution with the identification with Spain as a whole (vid. Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Degree of territorial identification (0-10 scale)

Source: CIS’ Time Series E.4.05.01.002 “Scale of identification (0-10) with the Autonomous Community”, and CIS’ Times Series E.4.05.01.003 “Scale of identification (0-10) with Spain”.

Our hypothesis, then, is that the LMQ can only be a good indicator of national identity

feelings in societies hosting one or two advanced nation-building processes, but not

in societies characterized for having low intensity nationalisms. In this second kind

of societies, we will find simultaneously the same ethnic diacritics adopting nationalized

and un-nationalized versions of themselves, from an emic point of view ( Headland, Thomas N., Kenneth L. Pike and Marvin Harris. 1990. Emics and Etics: The Insider/Outsider Debate. London: Sage.Headland et al., 1990). This dynamic can be easily identified in the opposition between normative and vernacular

languages —vid. O’Rourke and Ramallo ( O’Rourke, Bernadette and Fernando Ramallo. 2011. “The native-non-native dichotomy

in minority language contexts”, Language Problems and Language Planning, 35 (2): 139-159. Available at:

It might be the case, however, that the relationship between national identity and

political preferences does correlate differently for the Spanish case. The reason

being that the national status of Scotland in the UK is out of discussion, a fundamental

difference with the Spanish case, where the national status of some ACs is a matter

of ongoing discussion and political confrontation. Thus, it might be the case that

sub-state national identification in Spain could be more clearly aligned with political

preferences than in Scotland, but further research is needed.

In order to test our hypothesis, we use data from Spain, due to two reasons. The

first reason is that the Spanish case offers a particularly adequate framework for

comparison among regions, as the Spanish Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS) has been producing empirical data on this matter at least since 1983 ( CIS. 2014. Series temporales. Available at:

DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS[up]

Let us start by analyzing data from CIS’ study Autonomic Barometer (III), no. 2956. This study involved the realization of a survey with 11 290 interviews within

Spain, with a sample that allows specific analysis for each one of the seventeen Spanish

Autonomous Communities (ACs). The fieldwork for this study took place between 13 September

and 09 October 2012, and the data is accessible online (CIS, 2012) There is no data available for inclusion in our analysis of the Autonomous Community

of the Region of Murcia, due to the absence of a question in its questionnaire that

allows us to measure the multiple levels of Murcian identity. Murcia, however, has

traditionally been an AC with a weak sense of AC identity; the LMQ for this AC in

CIS’ 2956 study indicated no identification with the category “Only Murcian, not Spanish”

and only a 6.3 % of people answering “More Murcian than Spanish”.

The wording of this question was: “Everyone feels attached, to some extent, with the

land where we live, but there are some areas to which we feel more attached than others.

To what extent do you feel identified with the village or city where you live? Use

a 0 to 10 scale to answer, where 0 means that you do not feel “any identification”

and 10 that you feel “very identified”. This question —absent in the questionnaire

for Murcia— included identification with Spain and with the AC.

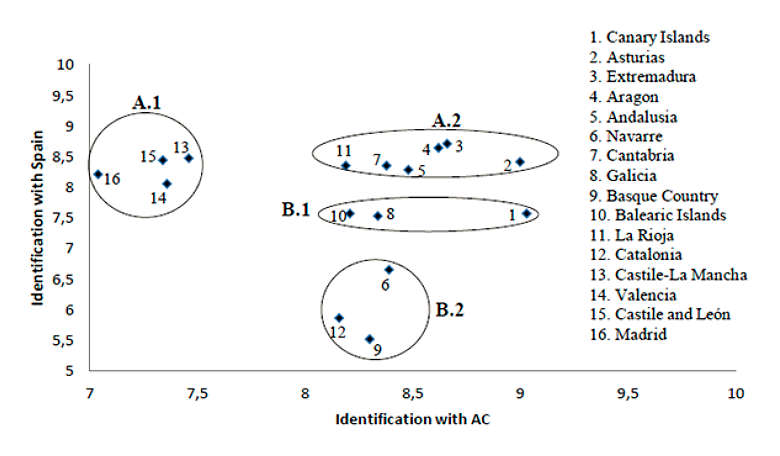

Figure 2.

Identification with Spain and with each AC (1-10)

Source: Elaborated by the authors with data from CIS’ study 2956.

Figure 2 represents two main groups of ACs: Group A contains the ACs in the upper part of the chart and group B includes the ACs occupying the lower space of the chart. We have then identified two subsets of ACs within each of the above groups. The first subset, A.1, includes Castile-La Mancha, Valencia, Castile and León and Madrid, all of them featuring a high level of identification with Spain (means ranging from 8 to 9, over 10) together with a relatively low identification with the AC (means ranging from 7 to 7.5, over 10). The second subset, A.2, is made up of ACs that present a high level of identification with Spain (means ranging from 8 to 9, over 10) but also a high level of identification with the AC (means ranging from 8 to 9, over 10), and includes Asturias, Extremadura, Aragon, Andalusia, Cantabria and La Rioja. The second group of ACs, group B, includes the ACs located under the best fit line of the scatter plot, hence characterized for having relatively low feelings of identification with Spain (means under 8, over 10). We have subdivided this group into two subsets, B.1 and B.2; the first one contains relatively low identifications with Spain (means ranging from 7 to 8, over 10) together with high levels of identification with the AC (means ranging from 8 to 9.03, over 10), and it includes the Canary Islands, Galicia and the Balearic Islands.

Finally, subset B.2 is made up of ACs featuring low levels of identification with

Spain (means ranging from 5 to 7, over 10) combined with high levels of identification

with the AC (means ranging from 8 to 8.5, over 10), and it includes Navarre, the Basque

Country and Catalonia. At this point, we have to note the peculiarity regarding the

case of Navarre, as this AC has been traditionally claimed as part of the Basque Country

by Basque nationalists —vid., e.g., Pérez-Agote ( Pérez-Agote, Alfonso. 1989. “Cambio social e ideológico in Navarra (1936-1982). Algunas

claves para su comprensión”, Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 46: 7-21. Available at:

From 2011 to 2015 more than 26,000 votes were lost by the Basque nationalists in Navarre.

This change is attributable to the irruption of the new party Podemos which, together with Ciudadanos, broke up with the two-party system that had characterized Spain during the last decades

( Orriols, Lluis and Guillermo Cordero. 2016. “The Breakdown of the Spanish Two-Party

System: The Upsurge of Podemos and Ciudadanos in the 2015 General Election”, South European Society and Politics, 21 (4): 469-492. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2016.1198454

In line with the existing literature, particularly Herranz de Rafael ( Herranz de Rafael, Gonzalo. 1996. “Estructura social e identificación nacionalista

in la España de los noventa”, Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 76: 9-35. Available at:

QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS[up]

It has been consistently proven that the press is a central actor in the reproduction

of national identity. Despite some skepticism on this relationship ( Schlesinger, Philip. 1991a. Media, State and Nation: Political Violence and Collective Identities. London: Sage.Schlesinger, 1991a; Schlesinger, Philip. 1991b. “Media, the Political Order and National Identity”, Media, Culture and Society, 13 (3): 297-308. Available at:

We have analyzed the front pages of newspapers read at least by 5 % of the adult newspaper reading population within each AC (vid. Table 2). We have consulted the front pages of these newspapers in two symbolic dates, exemplifying those flag-waving situations referred by Billig as moments of special patriotic meaning ( Billig, Michael. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: Sage Publications.Billig, 1995: 37-39). The first one is 11 September, the national day of Catalonia, and the second day is 12 October, the national day of Spain. The first day, also known as Diada Nacional de Catalunya, commemorates the fall of Barcelona, defeated by the Bourbon Spanish troops during the War of the Spanish Succession, on 11 September, 1714. The second day is the Fiesta Nacional de España, also referred to as Día de la Hispanidad, that commemorates the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus, on 12 October, 1492. It is worth noting that newspapers do not act as mere mirrors of state-building processes, but they are also an agent of nation-building in their respective communities; however, we believe that the analysis shows a clear empirical trend, enough to make it useful for our discussion.

Table 2.

Newspapers read in the different ACs

| Autonomous Community | Newspaper | Reading Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | El País | 21,7 |

| ABC | 10,7 | |

| El Mundo | 9,2 | |

| Ideal (Granada, Jaén, Almería) | 7,5 | |

| Diario Sur | 7,4 | |

| Córdoba | 5,3 | |

| Aragon | Heraldo de Aragón | 68,1 |

| El País | 11,7 | |

| Asturias | La Nueva España | 66,9 |

| La Voz de Avilés y el Comercio | 16,4 | |

| El País | 8,2 | |

| Balearic Islands | Última hora | 46,3 |

| Diario de Mallorca | 29,8 | |

| El País | 10,7 | |

| Diario de Baleares | 5,5 | |

| Basque Country | El Correo | 41,3 |

| El Diario Vasco | 24,2 | |

| El País | 6,1 | |

| Gara | 7,1 | |

| Canary Islands | El Día de Canarias | 27,0 |

| Canarias 7 | 22,1 | |

| La Provincia | 14,8 | |

| Diario de Avisos | 9,9 | |

| El País | 9,3 | |

| Cantabria | Diario Montañés | 63,1 |

| El País | 13,3 | |

| Alerta | 8,2 | |

| Castile-La Mancha | El País | 34,4 |

| El Mundo | 14,6 | |

| ABC | 11,5 | |

| Castile and León | El Norte de Castilla | 17,2 |

| El País | 17,1 | |

| Diario de León | 13,5 | |

| El Mundo | 9,5 | |

| Diario de Burgos | 7,7 | |

| La Opinión El Correo de Zamora | 6,3 | |

| Catalonia | El Periódico de Cataluña | 27,0 |

| La Vanguardia | 24,7 | |

| El País | 9,4 | |

| El Punt | 5,7 | |

| Extremadura | Hoy Diario de Extremadura | 55,0 |

| El País | 19,8 | |

| El Mundo | 9,6 | |

| El Periódico de Extremadura | 7,1 | |

| Galicia | La Voz de Galicia | 39,7 |

| Faro de Vigo | 17,4 | |

| El País | 11,0 | |

| El Progreso de Lugo | 6,4 | |

| La Región de Ourense | 5,6 | |

| La Rioja | La Rioja | 63,8 |

| El País | 12,6 | |

| Madrid | El País | 40,5 |

| El Mundo | 21,2 | |

| ABC | 7,3 | |

| 20 Minutos | 5,9 | |

| Navarre | Diario de Navarra | 56,9 |

| Diario de Noticias | 25,1 | |

| Valencia | El País | 25,4 |

| Levante | 20,4 | |

| Información de Alicante | 13,2 | |

| Las Provincias | 9,5 | |

| El Mundo | 7,9 | |

| Mediterráneo | 5,8 |

Source: CIS’ Autonomic Barometer III (Study 2956, for year 2012), with the exception of the ACs of Catalonia, Navarre, and La Rioja, for which we used the CIS’ Autonomic Barometer II (Study 2829, for year 2010). The wording of the question, formulated to those aged 18 or more who admit reading the newspaper, is: “And what newspaper do you prefer to follow political information?”.

We have chosen the national day of Catalonia because the national question in Spain

is very much focused on Catalonia since the Catalan elections held on 25 November

2012, which were anticipated by the Catalan government, and presented by CiU —the

coalition in government at that time—, as a monographic election around independence.

Independence was explicitly defended by Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya, one of the two political parties making up the governing coalition CiU —some leaders

of the other party, Unió Democràtica de Catalunya, had shown some reluctance to independence, however ( Piñol, Àngels. 2012. Duran rectifica y anuncia que irá a la marcha soberanista de

la Diada. Available at:

We have analyzed the headlines for these two symbolic days in four front pages for each newspaper, the day after each celebration: 12 September, and 13 October, both in 2013; we have also taken into account the same four dates for 2012, in order to better contrast our data. We have classified the messages of each headline into three different categories: negative, neutral and positive, in order to produce a comparative framework for the analysis of the news coverage of Spain’s identity politics. We have classified the headlines as negative when these are focused on criticizing the opponent —either Catalan or Spanish national projects. Accordingly, we have identified the messages as positive when these are focused on praising the own nation. When there is no evidence or neither negative nor positive messages, we will classified them as neutral.

Table 3, vid. infra, presents the results of our qualitative analysis of the press, and we can see that these are aligned with our hypothesis. The front-pages of strong state-wide ACs, grouped within set A.1, show a primacy of negative messages, 60 %, on the Catalan national day, while this trend is reversed on the Spanish national day, with a majority of positive messages, 64.3 %. We have found a primacy of positive messages on those ACs with strong sub-state nationalisms of group B.2 for both national days, 71.4 % on the national day of Catalonia, 68.6 % on the national day of Spain. In line with our hypothesis, trends are softer for the two sets of weakly nationalized ACs, A.2 and B.1; we found a majority of neutral messages on these two groups on the Catalan national day, 54.5 % in group A.2 and 58.3 % on group B.1. The analysis for the Spanish national day show a majority of positive messages in these two sets of weakly nationalized ACs, although this primacy is clearly bigger in the case of the strongly nationalized ACs —62.5 % of positive messages for group A.2 and 53.8 % for group B.1.

Table 3.

Type of messages published in the media for each group of ACs

| Catalan National Day (2012/13) | Spanish National Day (2012/13) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A.1 | Positive N ( %) |

0 (0.0 %) | 9 (64.3 %) |

| Neutral N ( %) |

6 (40.0 %) | 3 (21.4 %) | |

| Negative N ( %) |

9 (60.0 %) | 2 (14.3 %) | |

| A.2 | Positive N ( %) |

0 (0.0 %) | 10 (62.5 %) |

| Neutral N ( %) |

12 (54.5 %) | 4 (25.0 %) | |

| Negative N ( %) |

10 (45.5 %) | 2 (12.5 %) | |

| B.1 | Positive N ( %) |

2 (16.7 %) | 7 (53.8 %) |

| Neutral N ( %) |

7 (58.3 %) | 3 (23.1 %) | |

| Negative N ( %) |

3 (25.0 %) | 3 (23.1 %) | |

| B.2 | Positive N ( %) |

5 (71.4 %) | 24 (68.6 %) |

| Neutral N ( %) |

2 (28.6 %) | 2 (5.7 %) | |

| Negative N ( %) |

0 (0.0 %) | 9 (25.7 %) | |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS[up]

Once we have empirically proved that there are, in fact, remarkable differences among our proposed sets of ACs regarding the degree of national conflict associated to them and, thus, strengthening the usefulness of this classification, we will proceed to present some quantitative empirical evidence based again on data from the CIS’ study 2956, Barómetro Autonómico III. One of the questions in this study directly refers to the political status of Spain:

Q.18 What does Spain mean to you? (ONE ANSWER ONLY)

-

My country.

-

A nation of which I am a member.

-

The State of which I am a citizen.

-

A State made up of several nationalities and regions.

-

An alien State of which my country is not a part.

-

(DO NOT READ) None of the above.

-

Do not know.

-

h. Do not answer.

Options “a” and “b”, are expressions of Spanish nationalism, as we can say that people choosing these options consider Spain as a nation and, most importantly, as their nation. Options “d” and “e”, however, do not explicitly consider Spain as a nation, but simply as a State; moreover, people who choose options “d” or “e” consider that the Spanish State is made up from different sub-state nations. Option “c” is a neutral one, for it only describes the reality of Spain being a State within international law. We consider other response categories for Q18, options “f”, “g”, and “h”, as missing values. As Q18 is included in the questionnaire for every AC, we think that it is a good way to test our hypothesis, i.e., that the LMQ is a good indicator of national identity within those territories which are strongly nationalized, but not when applied to those regions which are weakly nationalized.

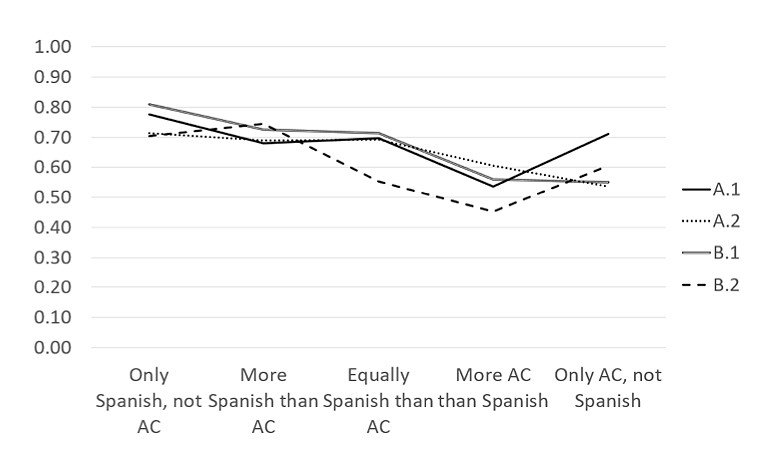

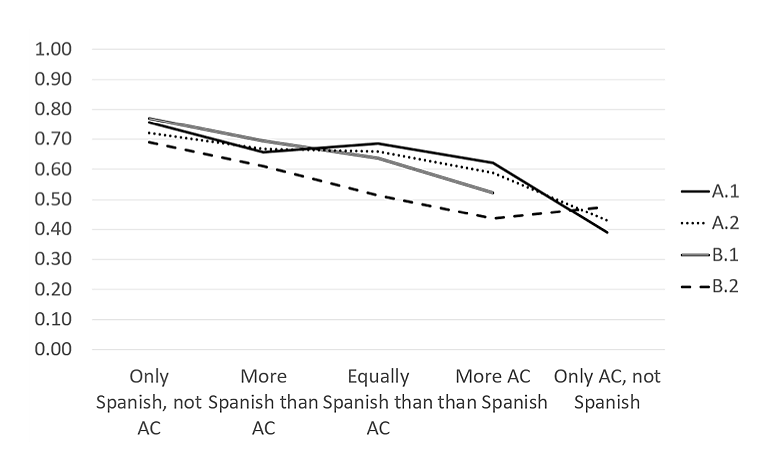

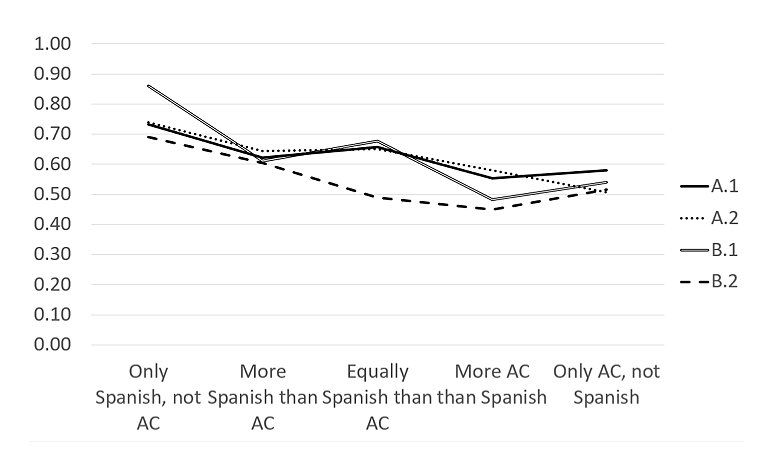

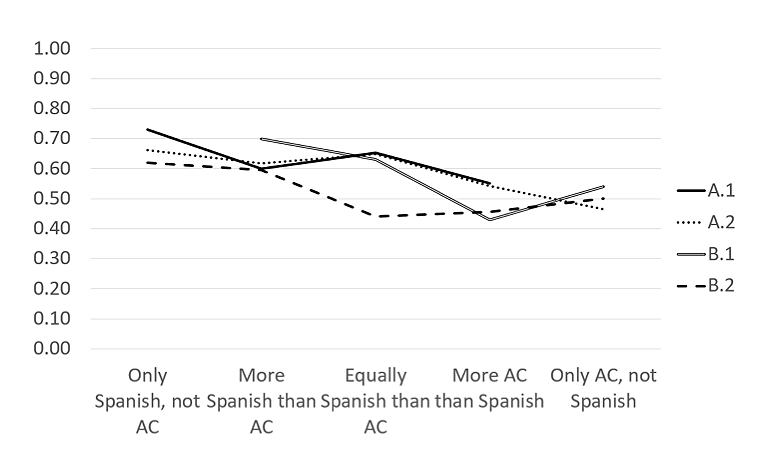

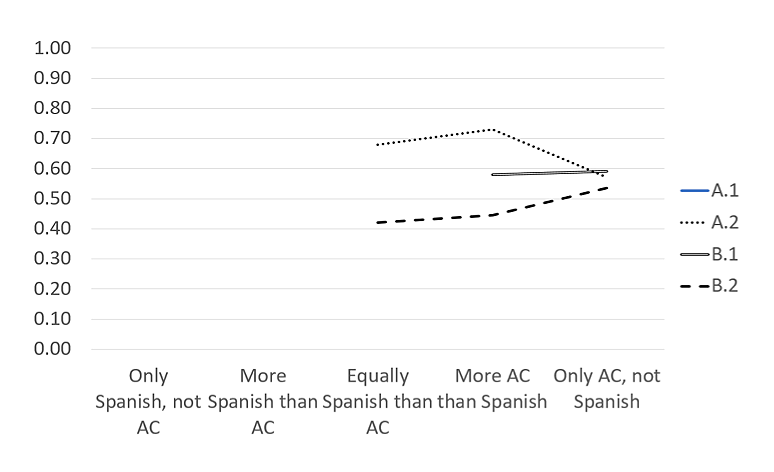

We have built a multinomial logistic regression model with Q18 as the dependent variable (DV), and the five categories of the LMQ as independent variables (IVs), controlling by sex and type of occupation. The model allows us to measure the predicted probabilities that respondents of the LMQ have to choose the different categories of Q18 (figures 3 to 7).

Figure 3.

Predicted probabilities of identifying Spain as ‘my country’ for the different categories of the LMQ

Figure 4.

Predicted probabilities of identifying Spain as ‘a nation of which I am a member’ for the different categories of the LMQ

Figure 5.

Predicted probabilities of identifying Spain as ‘a State of which I am a citizen’ for the different categories of the LMQ

Figure 6.

Predicted probabilities of identifying Spain as ‘a State including different nationalities and regions’ for the different categories of the LMQ

The results of the multinomial regression prove that the relationship between national identity and the response to the LMQ is structurally different for each of the four groups of Autonomous Communities. The results are also aligned with our hypothesis, as the category “only AC, not Spanish” of the LMQ is a better predictor of national identity —category “my country” in Q18— for the groups A.1 and B.2 of ACs. Moreover, the results of the regression show consistently lower predicted probabilities for “equally Spanish than AC” in the B.2 group for all Q18 categories, suggesting that this response to the LMQ has contradictory associations to national identity in those ACs with highly developed conflicting national projects.

CONCLUSIONS[up]

The scientific study of national identity is among the most urgent tasks for contemporary

social sciences. The relevance of identity politics and nationalism in Europe and

worldwide has only increased during the recent years. Some of the most relevant recent

political events are defined to a great extent by nationalism, including the Brexit

( Henderson, Ailsa, Charlie Jeffery, Robert Liñeira, Roger Scully, Daniel Wincott and Richard Wyn Jones. 2016. “England, Englishness

and Brexit”, The Political Quarterly, 87 (2): 187-199. Available at:

Thus, we have provided proof that the most usual measure of national identity feelings through surveys, the Linz-Moreno question, needs to be analyzed with methodological reflexivity. Using data from Spain, we have developed both qualitative and quantitative analyses in order to test if the LMQ provides a right measure of national identity independently of the degree of development of the nation-building processes present in each society. After classifying Spain’s Autonomous Communities into four categories in accordance to the identity feelings displayed by their populations, we saw that the LMQ presents structural differences when considered as a proxy of national identity feelings. In particular, the weakly nationalized ACs are usually considered a good example of what is usually referred to as “dual identity”, but we have shown that identity overlapping is only possible in these regions due to a substantive difference affecting both identities; while one is purely national, the other is regional.

We have presented a critique of the dual identity theory, which is the epistemological foundation of the LMQ; this critique is based on the fact that in societies where there is a clear primacy of a statewide national project, sub-state identity (or identities) is either totally or partially —in case that a sub-state national project developed— subsumed within the dominant state-wide national project, in the form of its regional expressions, producing what we may call a dialectalization of identity, through its regionalization. This regionalization process, based on the creation of symbolic dependencies —affecting those ethnic diacritics ( Barth, Fredrik. 1969. Ethnic Groups and Boundaries. The Social Organization of Culture Difference. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.Barth, 1969) through which national or pre-national sub-state identities are socially constructed— initiates a dialectical process in which this regionalization became the thesis, while the antithesis is embodied in diverse social movements that can, to some degree, be identified under the label of pro-independence; in fact we can easily cite many examples of these kind of movements in places where there is sufficient cultural diversity to make the situation too symbolically violent for the said dialectical process not to start, and these would include the defense and promotion of language, natural and historical heritage, music, literature, etc. ( Hroch, Miroslav. 1985. Social Preconditions of National Revival in Europe: A Comparative Analysis of the Social composition of Patriotic Groups among the Smaller European Nations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Hroch, 1985). Thus, what makes compatible both identities in the dual identity framework is precisely that the two identities are different in nature.

In conclusion, if nationalism should be treated as an ideology, as Billig insists

( Billig, Michael. 1993. Studying Nationalism as an Everyday Ideology. Papers on Social Representations, 2 (1): 40-43.Billig, 1993) maybe we could start by measuring it as such, making use of a similar scale to the

one that we usually employ to measure the left-right ideology The wording of this question in CIS’ studies is: “Usually, when talking about politics,

the expressions left and right are used. If 1 was extreme left and 10 extreme right,

which one would be your positioning?”.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS[up]

We want to thank the participants in the Working Group “State Nationalism in Plurinational Democracies”, of the 13th AECPA Congress, for their useful insight and comments that helped us to improve this article. Especially, we want to thank its coordinators, Dr. Antonia María Ruiz Jiménez and Dr. Angustias Mª Hombrado Martos. We also want to thank Mr. Ross Bond, from the School of Social and Political Science of the University of Edinburgh, for his very useful comments on an earlier draft of this article. We are also grateful to the “Territorial Politics and Governing Divided Societies” Research Group, led by Dr. Wilfried Swenden at the same University, for their helpful comments following the presentation of the main findings of this work on the conference that took place in Edinburgh, on December the 10th, 2013. Finally, we want to thank the “Plan Galego de Investigación, Innovación e Crecemento 2011-2015”, of the Xunta de Galicia, for its financial support.

Notes[up]

| [1] |

Although formally initiated with the signature of the “Declaration of the initiation of the Process of Independence of Catalonia”, on 9 November 2015, passed in the Parliament of Catalonia with 72 votes in favor, 63 against and 0 abstentions, it is usually agreed that the process started with the Catalan pro-independence demonstration of 11 September 2012. |

| [2] |

It is worth noting that, although it is sometimes referred to simply as the “Moreno

Question” within the Anglo-Saxon academic world ( Kiely, Richard, David McCrone and Frank Bechhofer. 2006. “Reading between the lines:

national identity and attitudes to the media in Scotland”, Nations and Nationalism, 12 (3): 473-492. Available at:

|

| [3] |

It might be the case, however, that the relationship between national identity and political preferences does correlate differently for the Spanish case. The reason being that the national status of Scotland in the UK is out of discussion, a fundamental difference with the Spanish case, where the national status of some ACs is a matter of ongoing discussion and political confrontation. Thus, it might be the case that sub-state national identification in Spain could be more clearly aligned with political preferences than in Scotland, but further research is needed. |

| [4] |

There is no data available for inclusion in our analysis of the Autonomous Community of the Region of Murcia, due to the absence of a question in its questionnaire that allows us to measure the multiple levels of Murcian identity. Murcia, however, has traditionally been an AC with a weak sense of AC identity; the LMQ for this AC in CIS’ 2956 study indicated no identification with the category “Only Murcian, not Spanish” and only a 6.3 % of people answering “More Murcian than Spanish”. |

| [5] |

The wording of this question was: “Everyone feels attached, to some extent, with the land where we live, but there are some areas to which we feel more attached than others. To what extent do you feel identified with the village or city where you live? Use a 0 to 10 scale to answer, where 0 means that you do not feel “any identification” and 10 that you feel “very identified”. This question —absent in the questionnaire for Murcia— included identification with Spain and with the AC. |

| [6] |

From 2011 to 2015 more than 26,000 votes were lost by the Basque nationalists in Navarre.

This change is attributable to the irruption of the new party Podemos which, together with Ciudadanos, broke up with the two-party system that had characterized Spain during the last decades

( Orriols, Lluis and Guillermo Cordero. 2016. “The Breakdown of the Spanish Two-Party

System: The Upsurge of Podemos and Ciudadanos in the 2015 General Election”, South European Society and Politics, 21 (4): 469-492. Available at:

|

| [7] |

The wording of this question in CIS’ studies is: “Usually, when talking about politics, the expressions left and right are used. If 1 was extreme left and 10 extreme right, which one would be your positioning?”. |

References[up]

|

Abélès, Marc. 1990. Anthropologie de l’état. Paris: Armand Colin. |

|

|

Álvarez-Cáccamo, Celso. 1993. “The pigeon house, the octopus and the people: The ideologization of linguistic practices in Galiza”, Plurilinguismes, 6: 1-26. |

|

|

Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso. |

|

|

Armstrong, John A. 1982. Nations Before Nationalism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. |

|

|

Balandier, Georges. 1994. El poder in escenas. De la representación del poder al poder de la representación. Barcelona: Paidós. |

|

|

Balibar, Étienne. 2005. Violencias, identidades y civilidad. Para una cultura política global. Barcelona: Gedisa. |

|

|

Barth, Fredrik. 1969. Ethnic Groups and Boundaries. The Social Organization of Culture Difference. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. |

|

|

Beramendi, Justo G. 1999. “Identity, ethnicity and state in Spain: 19th and 20th centuries”, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 5 (3-4): 79-100. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13537119908428571. |

|

|

Beramendi, Justo G. 2007. De provincia a nación. Historia do Galeguismo político. Vigo: Xerais. |

|

|

Beswick, Jaine. 2007. Regional Nationalism in Spain. Language Use and Ethnic Identity in Galicia. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Available at: https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853599811. |

|

|

Billiet, Jaak, Bart Maddens and Roeland Beerten 2003. “National Identity and Attitude Toward Foreigners in a Multinational State: A Replication”, Political Psychology, 24 (2): 241-257. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00327. |

|

|

Billig, Michael. 1993. Studying Nationalism as an Everyday Ideology. Papers on Social Representations, 2 (1): 40-43. |

|

|

Billig, Michael. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: Sage Publications. |

|

|

Bond, Ross. 2000. “Squaring the Circles: Demonstrating and Explaining the Political ‘Non-Alignment’ of Scottish National Identity”, Scottish Affairs, 32: 15-35. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3366/scot.2000.0029. |

|

|

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1971. “Champ du pouvoir, champ intellectuel et habitus de classe”. Scoliès. Cahiers de recherche de l’Ecole normale supérieure, 1: 7-26. |

|

|

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1987. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

|

|

Bourdieu, Pierre. 2012. Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. London: Routledge. |

|

|

Bouza, Fermín. 2004. “The Impact Area of Political Communication: Citizenship Faced with Public Discourse”, International Review of Sociology, 14 (2): 245-259. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03906700410001681310. |

|

|

Brookes, Rod. 1999. “Newspapers and national identity: the BSE/CJD crisis and the British press”. Media, Culture and Society, 21 (2): 247-263. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/016344399021002007. |

|

|

Brubaker, Rogers. 2009. “Ethnicity, Race, and Nationalism”, Annual Review of Sociology, 35: 21-42. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115916. |

|

|

Chueca-Intxusta, Josu. 1999. El nacionalismo vasco in Navarra (1931-1936). Bilbao: Servicio Editorial de la Universidad del Pais Vasco, Argitalpen Zerbitzua Euskal Herriko Unibersitatea. |

|

|

CIS. 2014. Series temporales. Available at: http://www.analisis.cis.es/cisdb.jsp. |

|

|

Conversi, Daniele. 1997. The Basques, the Catalans and Spain. Alternative Routes to Nationalist Mobilisation. London: Hurst. |

|

|

Crameri, Kathryn. 2014. Goodbye Spain? The question of independence for Catalonia. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. |

|

|

Curtice, John and Anthony Heath. 2001. “Is the English lion about to Roar? National identity after devolution”, in Roger Jowell et al. (eds.), British Social Attitudes: Focusing on Diversity. London: Sage. |

|

|

De Nieves, Arturo. 2008. “Ideoloxías lingüísticas na comunidade de fala galega. O caso da cidade da Coruña”, Revista Galega de Ciencias Sociais, 7: 29-44. |

|

|

Deutsch, Karl W. 1966. Nationalism and Social Communication: An inquiry into the foundations of nationality. Cambridge (MA): The Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press. |

|

|

Dinnie, Keith. 2008. Nation Branding. Concepts, Issues, Practice. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. |

|

|

Eder, Klaus, Bernd Giesen, Oliver Schmidtke and Damian Tambini. 2002. Collective Identities in Action. A sociological approach to ethnicity. Aldershot: Ashgate. |

|

|

Friend, Julius W. 2012. Stateless Nations. Western European Regional Nationalisms and the Old Nations. London: Palgrave Macmillan. |

|

|

García Ferrando, Manuel, Eduardo López Aranguren and Miguel Beltrán. 1994. La conciencia nacional y regional in la España de las autonomías. Madrid: CIS. |

|

|

Gellner, Ernest. 1983. Nations and Nationalism. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. |

|

|

Guinjoan, Marc and Toni Rodon. 2015. “A Scrutiny of the Linz-Moreno Question”, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 46 (1): 128-142. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjv031. |

|

|

Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books. |

|

|

Goldthorpe, John H. 2000. On Sociology. Numbers, Narratives, and the Integration of Research and Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Gunther, Richard, Giacomo Sani and Goldie Shabad. 1986. Spain after Franco: the Making of a Competitive Party System. Berkeley: University of California Press. |

|

|

Habermas, Jürgen. 2012. The Crisis of the European Union. A Response. Cambridge: Polity Press. |

|

|

Hall, John A. and Siniša Maleševic. 2013. Nationalism and War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139540964. |

|

|

Haugaard, Mark. 2006. “Nationalism and Liberalism”, in Gerard Delanty and Krishan Kumar, (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Nations and Nationalism. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848608061.n30. |

|

|

Haugen, Einar. 1966. “Dialect, Language, Nation”, American Anthropologist, 68 (4): 922-935. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1966.68.4.02a00040. |

|

|

Haupt, Georges, Michael Löwy and Claudie Weill. 1974. Les marxistes et la question nationale. Paris: Maspero. |

|

|

Headland, Thomas N., Kenneth L. Pike and Marvin Harris. 1990. Emics and Etics: The Insider/Outsider Debate. London: Sage. |

|

|

Heath, Anthony and James Kellas. 1998. “Nationalisms and constitutional questions”, Scottish Affairs, 25 (2): 110-128. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3366/scot.1998.0070. |

|

|

Henderson, Ailsa, Charlie Jeffery, Robert Liñeira, Roger Scully, Daniel Wincott and Richard Wyn Jones. 2016. “England, Englishness and Brexit”, The Political Quarterly, 87 (2): 187-199. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12262. |

|

|

Herranz de Rafael, Gonzalo. 1996. “Estructura social e identificación nacionalista in la España de los noventa”, Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 76: 9-35. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/40183984. |

|

|

Herrero, Mário J. 2011. Guerra de grafias, conflito de elites na Galiza contemporânea. Santiago de Compostela: Atraves Editora. |

|

|

Hobsbawm, Eric. 1991. Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

|

|

Hroch, Miroslav. 1985. Social Preconditions of National Revival in Europe: A Comparative Analysis of the Social composition of Patriotic Groups among the Smaller European Nations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

|

|

Ichijo, Atsuko. 2013. Nationalism and Multiple Modernities. Europe and Beyond. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137008756 |

|

|

Idoiaga, Petxo, Imanol Murua and Txema Ramirez. 2016. “Press coverage of Basque conflict (1975-2016): Compilation of attitudes and vicissitudes”, Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 71: 1007-1035. |

|

|

Jones, Rhys and Peter Merriman. 2009. “Hot, banal and everyday nationalism: Bilingual road signs in Wales”, Political Geography, 28 (3): 164-173. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2009.03.002 |

|

|

Kendrick, Stephen. 1989. “Scotland, Social Change and Politics”, in David McCrone, Stephen Kendrick and Pat Straw (eds.), The Making of Scotland: Nation, Culture and Social Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. |

|

|

Kiely, Richard, Frank Bechhofer, Robert Stewart and David McCrone. 2001. “The markers and rules of Scottish national identity”, The Sociological Review, 49 (1): 33-55. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.00243. |

|

|

Kiely, Richard, David McCrone and Frank Bechhofer. 2006. “Reading between the lines: national identity and attitudes to the media in Scotland”, Nations and Nationalism, 12 (3): 473-492. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8129.2006.00249.x. |

|

|

Kuzio, Taras. 2016. “European Identity, Euromaidan, and Ukrainian Nationalism”, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 22: 497-508. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2016.1238249. |

|

|

Law, Alex. 2001. “Near and far: banal national identity and the press in Scotland”, Media, Culture and Society, 23 (3): 299-317. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/016344301023003002. |

|

|

Lepič, Martin. 2017. “Limits to territorial nationalization in election support for an independence-aimed regional nationalism in Catalonia”, Political Geography, 60: 190-202. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.08.003. |

|

|

Linz, Juan J. 1973. “Early State-Building in the Late Peripheral Nationalisms against the State: the case of Spain”, in Shmuel N. Eisenstadt and Stein Rokkan (eds.), Building States and Nations: Models, Analysis and Data across Three Worlds. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. |

|

|

Linz, Juan J., Shmuel N. Eisenstadt and Stein Rokkan. 1973. Early state-building and late peripheral nationalism against the state: the case of Spain. London: Sage. |

|

|

Luhtanen, Riia and Jennifer Crocker. 1992. “A collective self-esteem scale. Self-evaluation of one’s social identity”, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18 (3): 302-318. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167292183006. |

|

|

Máiz, Ramón and Antón Losada. 2000. “Institutions, Policies and Nation Building: The Galician Case”, Regional and Federal Studies, 10 (1): 62-91. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560008421109. |

|

|

March, James G. and Johan P. Olsen. 1989. Rediscovering Institutions. New York: Free Press. |

|

|

Martinez-Herrera, Enric. 2002. “From nation-building to building identification with political communities: Consequences of political decentralization in Spain, the Basque Country, Catalonia and Galicia, 1978-2001”, European Journal of Political Research, 41, (4): 421-453. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00018. |

|

|

McCrone, David. 1998. The Sociology of Nationalism. London: Routledge. |

|

|

McCrone, David. 2001. “Who Are We? Understanding Scottish Identity”, in Catherine Di Domenico, Alexander Law, Jonathan Skinner and Mick Smith (eds.), Boundaries and Identities: Nation, Politics and Culture in Scotland. Dundee: University of Abertay Press. |

|

|

McCrone, David, Angela Morris and Richard Kiely. 1995. Scotland the Brand: The Making of Scottish Heritage. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. |

|

|

Merton, Robert K. 1987. “Three Fragments from a Sociologist’s Notebooks: Establishing the Phenomenon, Specified Ignorance, and Strategic Research Materials”, Annual Review of Sociology, 13 (1): 1-28. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.13.080187.000245. |

|

|

Mihelj, Sabina. 2011. Media Nations: Communicating Belonging and Exclusion in the Modern World. Basingstoke: Palgrave. |

|

|

Moreno, Luis. 1986. Decentralisation in Britain and Spain: the cases of Scotland and Catalonia. Drucker, Henry (dir.), University of Edinburgh, Scotland. |

|

|

Moreno, Luis. 1988. “Scotland and Catalonia: the path to home rule”, in David McCrone, and Alice Brown (eds.), Scottish Government Yearbook 1988. Edinburgh: Unit for the Study of Government in Scotland. |

|

|

Moreno, Luis. 2004. “Identidades múltiples y mesocomunidades globales”, in Francesc Morata, Guy Lachapelle and Stéphane Paquin (eds.), Globalización, gobernanza e identidades. Barcelona: Fundació Carles Pi Sunyer d’Estudis Autonòmics i Locals. |

|

|

Moreno, Luis. 2006. “Scotland, Catalonia, Europeanization and the ‘Moreno Question’”, Scottish Affairs, 54 (1): 1-21. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3366/scot.2006.0002. |

|

|

Moreno, Luis and Ana Arriba. 1996. “Dual Identity In Autonomous Catalonia”, Scottish Affairs, 17 (1): 78-97. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3366/scot.1996.0056. |

|

|

Moreno, Luis and Nicola McEwen. 2005. “Exploring the territorial politics of welfare”, in Nicola McEwen and Luis Moreno (eds.), The territorial politics of welfare. Oxon/New York: Routledge. |

|

|

Mullen, Tom. 2014. “The Scottish Independence Referendum 2014”, Journal of Law and Society, 41 (4): 627-640. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6478.2014.00688.x. |

|

|

Nairn, Tom. 2007. “Union on the rocks?”, New Left Review, 43: 117-132. |

|

|

Orriols, Lluis and Guillermo Cordero. 2016. “The Breakdown of the Spanish Two-Party System: The Upsurge of Podemos and Ciudadanos in the 2015 General Election”, South European Society and Politics, 21 (4): 469-492. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2016.1198454 |

|

|

O’Rourke, Bernadette and Fernando Ramallo. 2011. “The native-non-native dichotomy in minority language contexts”, Language Problems and Language Planning, 35 (2): 139-159. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1075/lplp.35.2.03oro |

|

|

Özkirimli, Umutu. 2010. Theories of Nationalism: A Critical Introduction. London: Palgrave Macmillan. |

|

|

Pattie, Charles, David Denver, James Mitchell and Hugh Bochel. 1999. “Partisanship, national identity and constitutional preferences: an exploration of voting in the Scottish devolution referendum of 1997”, Electoral Studies, 18 (3): 305-322. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-3794(98)00054-7. |

|

|

Pérez-Agote, Alfonso. 1989. “Cambio social e ideológico in Navarra (1936-1982). Algunas claves para su comprensión”, Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 46: 7-21. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/40183391. |

|

|

Piñol, Àngels. 2012. Duran rectifica y anuncia que irá a la marcha soberanista de la Diada. Available at: http://ccaa.elpais.com/ccaa/2012/09/08/catalunya/1347056908_076969.html [Consulted: 28 October 2013]. |

|

|

Plato. 1968 [380BC]. Republic (Vol. VI). New York: Harper Collins. |

|

|

Powell, Walter W. and Paul J. Dimaggio. 1991. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago: Chicago University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226185941.001.0001 |

|

|

Renan, Ernest. 1997. Qu’est-ce qu’une nation? Paris: Mille et une nuits. |

|

|

Rigger, Shelley. 2000. “Social Science and National Identity: A Critique”, Pacific Affairs, 537-552. |

|

|

Rivera, Jose M. and Erika Jaráiz. 2016. “Modelos de explicación y componentes del voto in las elecciones autonómicas catalanas de 2015”. Revista Española de Ciencia Política, 42: 13-43. Available at: https://doi.org/10.21308/recp.42.01. |

|

|

Robert, Elen. 2009. “Accommodating ‘new’ speakers? An attitudinal investigation of L2 speakers of Welsh in south-east Wales”, International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 195: 93-116. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/IJSL.2009.007. |

|

|

Roosvall, Anna and Inka Salovaara-Moring. 2010. Communicating the Nation: National Topographies of Global Media Landscapes. Gothenburg: Nordicom. |

|

|

Rosie, Michael, John MacInnes, Pille Petersoo, Susan Condor and James Kennedy. 2004. “Nation speaking unto nation? Newspapers and national identity in the devolved UK”, The Sociological Review, 52 (4): 437-458. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2004.00490.x. |

|

|

Rosie, Michael and Ross Bond. 2008. “A Decade of Devolution: How Does it Measure Up?”, Radical Statistics, 97: 47-65. |

|

|

Ruiz Jiménez, Antonia. 2007. “Los instrumentos de medida de las identidades in los estudios del CIS y el Eurobarómetro: problemas de validez de la denominada escala Moreno”, Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 117 (1): 161-182. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/40184757. |

|

|

Schlesinger, Philip. 1991a. Media, State and Nation: Political Violence and Collective Identities. London: Sage. |

|

|

Schlesinger, Philip. 1991b. “Media, the Political Order and National Identity”, Media, Culture and Society, 13 (3): 297-308. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/016344391013003002. |

|

|

Schlesinger, Philip. 1993. “Wishful Thinking: Cultural Politics, Media and Collective Identities in Europe”, Journal of Communication, 43 (2): 6-17. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01258.x. |

|

|

Serrano, Ivan. 2013. “Just a Matter of Identity? Support for Independence in Catalonia”, Regional and Federal Studies, 23 (5): 523-545. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2013.775945. |

|

|

Serricchio, Fabio. 2012. “Italian Citizens and Europe: Explaining the Growth of Euroscepticism”, Bulletin of Italian Politics, 4 (1): 115-134. |

|

|

Shabad, Goldie and Richard Gunther. 1982. “Language, Nationalism, and Political Conflict in Spain”, Comparative Politics, 14 (4): 443-477. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/421632. |

|

|

Smith, Anthony D. 1983. “Nationalism and Classical Social Theory”, The British Journal of Sociology, 34 (1): 19-38. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/590606. |

|

|

Stavenhagen, Rodolfo. 1996. Ethnic Conflicts and the Nation-State. London: Macmillan. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-25014-1. |

|

|

Thomas, Alys. 1997. “Language policy and nationalism in Wales: a comparative analysis”, Nations and Nationalism, 3 (3): 323-344. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1354-5078.1997.00323.x. |

|

|

Tomlinson, John. 1991. Cultural Imperialism: A Critical Introduction. New York: Continuum. |

|

|

Trump, Donald. 2015. Crippled America. New York: Simon and Schuster. |

|

|

Tusell, Javier. 1997. Historia de España (Vol. XII). Madrid: Espasa Calpe. |

|

|

Vaczi, Mariann. 2016. “Catalonia’s Human Towers: Nationalism, Associational Culture, and the Politics of Performance”, American Ethnologist, 43 (2): 353-368. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12310. |

|

|

Wodak, Ruth, Rudolf de Cillia and Martin Reisigl. 2009. The Discursive Construction of National Identity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. |

|

|

Wright, Erik O. 2005. Approaches to Class Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511488900. |

|

|

Yumul, Arus and Umut Ozkirimli. 2000. “Reproducing the nation: ‘banal nationalism’ in the Turkish press. Media, Culture and Society, 22 (6): 787-804. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/016344300022006005. |

Biography[up]

| [a] |

Obtained his Ph.D. Cum Laude with International Mention by the Universidade da Coruña in 2015. His Ph.D. thesis

“Mathematical Principles for a Theoretical Model of Electoral Behavior from an Expanded

Theory of Practice” received the Extraordinary Doctorate Award of the Universidade

da Coruña (2015/16). During his pre-doctoral period, Arturo de Nieves worked for one

year at the Research Department of Spain’s Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, after receiving one of the 2012 CIS’ training scholarships. His pre-doctoral research

was completed with two three-month research visits, one to the School of Social and

Political Science of the University of Edinburgh, UK (2013), the other to the Instituto de Ciências Sociais of the Universidade do Minho, Portugal (2014). Since 2015, Dr De Nieves works for

the United Nations, in the organization’s New York headquarters and with the UN Department

of Peace Operations, in South Sudan. Currently seconded by the IOM-UN Migration, Arturo

de Nieves is Head of Situation and Analysis for the Inter Sector Coordination Group

Secretariat, coordinating the response to the Rohingya refugee crisis, in Bangladesh. |

| [b] |

Interim Substitute Professor in the Department of Sociology and Communication Sciences

of the University of A Coruña (UDC). Degree in Sociology and Doctor Cum Laude with Extraordinary Award in Social and Cultural Anthropology (2016). He has been Visiting

Researcher at the Université Bordeaux II. He is a member of the Evaluating Board of

AIBR, Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana. Researcher in the Sociology Team of

International Migrations (ESOMI) of the UDC and collaborating member of the Research

Group on Social Exclusion and Control (GRECS) of the Universitat de Barcelona. His

main lines of research are political sociology, activism, subjectivities, social movements,

urban studies and the anthropology of the body, with a special interest in ethnography

and qualitative methodology. |