The Italian Democratic Party, its nature and its Secretary

El Partido Demócrata Italiano, su naturaleza y su Secretaría General

ABSTRACT

The Democratic Party (PD) is the only reasonably organized party in the Italian de-structured party system. It is itself undergoing a process of transformation. It defies all traditional party definitions. It is no longer a class-based mass party and not even a mass party. Nobody within the party believes that such a party can resurrect. It shows many features of a catch-all party, but some of them are by far more prominent than others. It is not simply an electoral-professional party since its aims go beyond just winning the elections and it relies more on internal resources than on outside professionals. At this point, the most appropriate definition is that of a personalist party cum factions. This article tries to explain : (1) how the PD has acquired a dominant position in Italian politics; (2) how its leader has been elected by members and sympathizers of the party; and (3) how much he is trying to transform the PD into a vehicle pursuing his personal ambitions. Much of what Matteo Renzi will achieve or fail to obtain depends on the new electoral law and on the opposition mounted by some actors, especially the Five Stars Movement. The easiest forecast is that in the short-run the Italian party system will remain de-structured providing opportunities, but also volatility risks for the PD and its leader.

Keywords: Italy; party system; personalist party; leadership; primaries.

RESUMEN

El Partido Demócrata (PD) es el único partido razonablemente organizado en el desestructurado sistema de partidos italiano. El propio PD está sufriendo un proceso de transformación que desafía todas las definiciones tradicionales de partidos. Ya no es un partido de masas de clase y ni siquiera un partido de masas. Nadie dentro del partido cree que tal partido pueda resucitar. Muestra muchos rasgos de un partido «atrapa todos», pero algunos de ellos son mucho más prominentes que otros. No es simplemente un partido profesional-electoral ya que sus objetivos van más allá de ganar las elecciones y depende más de los recursos internos que de profesionales externos. En este momento, la definición más apropiada es la de un partido personalista con facciones. Este artículo trata de explicar (1) cómo el PD ha adquirido una posición dominante en la política italiana; (2) cómo han elegido los miembros y los simpatizantes del partido a su líder y (3) cómo este último está intentando transformar el PD en un vehículo para sus ambiciones personales. Gran parte de lo que Matteo Renzi obtenga o no depende de la nueva ley electoral y de la oposición organizada por algunos actores, en especial el Movimiento Cinco Estrellas. El pronóstico más fácil es que en el corto plazo el sistema de partidos italiano seguirá desestructurado brindando oportunidades, pero también riesgos de volatilidad para el PD y su líder.

Palabras clave: Italia; sistema de partidos; partido personalista; liderazgo; primarias.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION[up]

The purpose of this article is to provide an analysis of the only remaining party in Italian politics: the Democratic Party. Specifically, it will examine its organization, the procedures to choose the party leader and the candidates to elective offices and its policies with special reference to electoral and constitutional reforms. It does so in an attempt to predict the possible transformation of the party and its changed role within the Italian party system. The defeat in the December 4, 2016 constitutional referendum, the February 2017 split of some dissenting sectors and the poor results in the June 2017 municipal elections have weakened the Democratic Party to an extent impossible to evaluate at this point in time. The future of the party will also depend on the type of electoral law that will finally be drafted.

ONE PARTY, MANY MODELS[up]

Product of a “cold” (that is, not accompanied by much enthusiasm) merger between the

Left Democrats (mostly former Communists) and the Daisy (mostly former Christian Democrats)

(Bordandini, Paola, Aldo Di Virgilio y Francesco Raniolo. 2008. “The Birth of a Party:

The Case of the Italian Partito Democratico”, South European and Politics, 13 (3): 303-24. Available at:

Perhaps, today’s Democratic Party is best defined as a personalist party. According

to the criteria specified by Kostadinova and Levitt, personalist parties are defined

by: a) the presence of a dominant leader; b) a party “organization” that is weakly institutionalized by design; and c) the “interactions between the leader and other politicians” are “driven mainly by

loyalty to that leader rather than e.g., organizational rules, ideological affinities,

or programmatic commitments” (Kostadinova, Tatiana and Barry Levitt. 2014. “Towards a Theory of Personalist Parties:

Concept Formation and Theory Building”, Politics and Policy, 42 (4): 490-512. Available at:

As most parties of medium-large size in contemporary competitive democratic systems, on the whole the PD is a professional-electoral party. According to Panebianco’s (Panebianco, Angelo. 1988. Political Parties: Organization and Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.1988: 264) criteria, a professional-electoral party is characterized by: a) a central role of the professionals; b) weak vertical ties, appeal to the “opinion electorate”; c) pre-eminence of the elected representatives, personalized leadership; d) financing through interest groups and public funds; f) stress on issues and leadership, central role of the careerists and representatives of interest groups within the organization. Though not fully aware of all the implications of its transformation, the PD or, at least, its party secretary and Prime Minister Matteo Renzi and his exclusive (“magic”) circle of collaborators stress their post-ideological, highly modern, future-oriented stances and policies without paying attention to the party organization nor investing energy and resources in its actual working. In several areas of Italy, the PD is in disarray or, simply, does not exist.

IN SEARCH OF AN ORGANIZATION[up]

As said, since its inception, the PD has not paid any attention to its organization.

The Daisy had practically retained no presence on the ground except where some powerful

professional politicians had a personal electoral base. The Left Democrats could rely

on some local structures especially, almost exclusively, in the so-called “Red Belt”

(central regions of Italy) and in few urban areas in the North-West. That the organization

of the party on the ground was fundamentally of no interest to the leaders of the

PD was immediately confirmed by Walter Veltroni’s summer campaign (2007) to win the

office of party secretary. His entire platform was devoted to proposals to tackle

and solve the socio-economic problems of Italy. What kind of party the new secretary

would like to shape and lead was never discussed. Indeed, it was not part of Veltroni’s

suggestive political narrative (Floridia, Antonio. 2009. “Modelli di partito e modelli di democrazia: analisi critica

dello Statuto del PD”, in Gianfranco Pasquino (ed.), Il Partito Democratico. Elezione del segretario, organizzazione e potere. Bologna: Bononia University Press.Floridia, 2009). In different forms and degrees, all other secretaries of the party have shown the

same reluctance to deal with the organizational structure of the party, especially

at the local level. In particular, this tendency is rather evident if we observe the

decline of party membership numbers, both in absolute and percentage terms. Looking

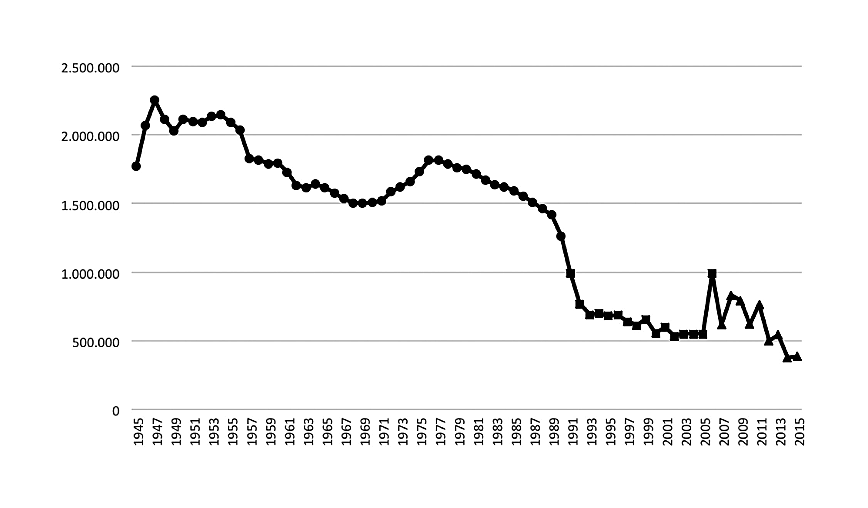

at Figure 1, it is possible to compare the level of party membership of the PD with that of the

Italian Communist (until 1990) and post-Communist party (1991-2006). The downward

trend, which is common throughout Western Europe (Poguntke, Thomas, Susan E. Scarrow and Paul Webb. 2016. “Party rules, party resources

and the politics of parliamentary democracies: How parties organize in 21st century”,

Party Politics, 22 (6): 661-78. Available at:

Figure 1.

Membership of the Italian Communist Party (PCI, 1945-1990), the Democratic Party of the Left or Left Democrats (1991-2006), the Democratic Party (2007-2015), absolute values

Legend: l = PCI, n = PDS/DS; s = PD.

Sources: own elaboration. Istituto Cattaneo (www.cattaneo.org); Partito Democratico (www.partitodemocratico.it); Pasquino (Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi. 2013. “Post-electoral politics in Italy:

Institutional problems and political perspectives”, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 18 (4): 466-84. Available at:

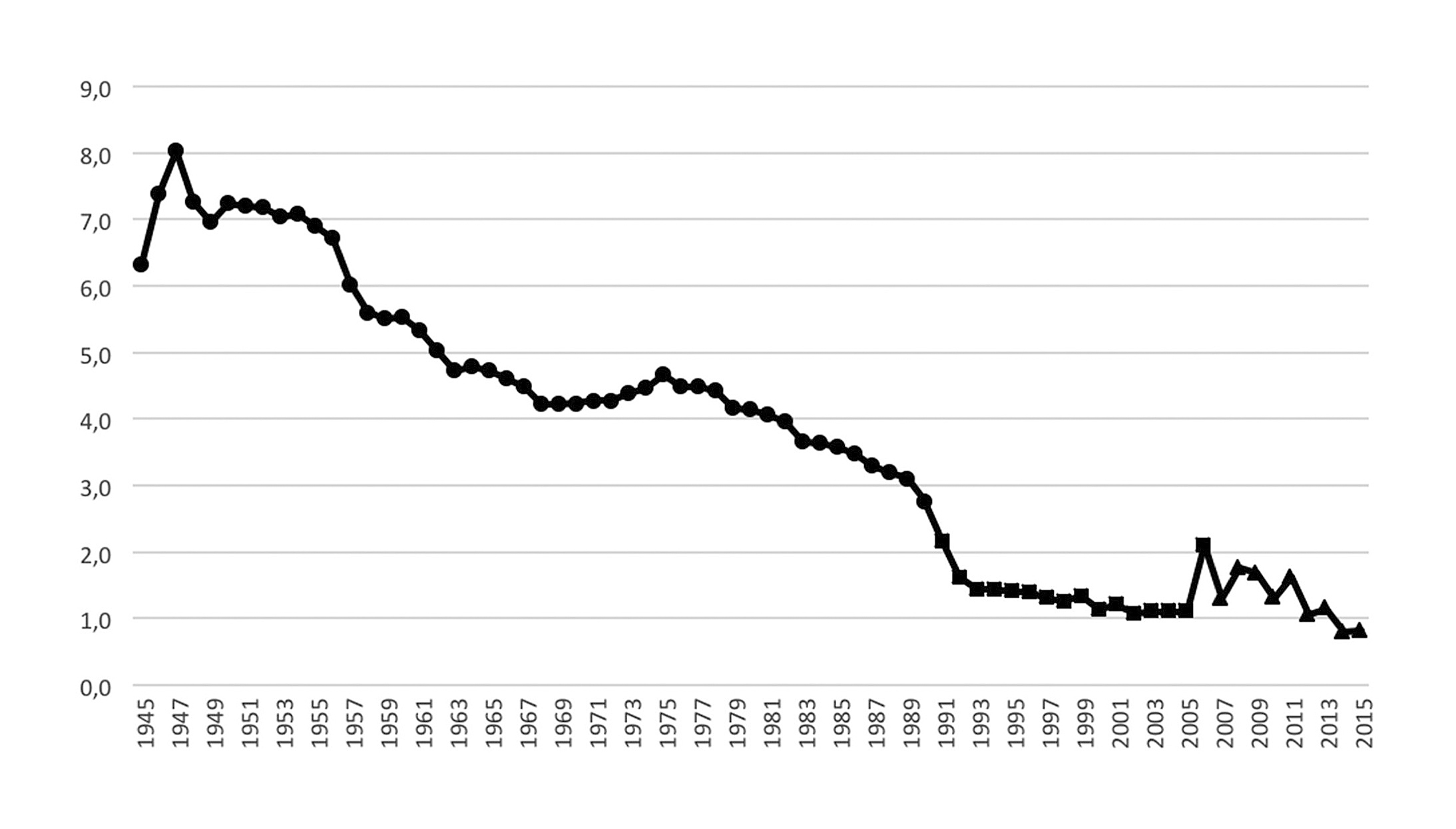

Figure 2.

Membership of the Italian Communist Party (PCI, 1945-1990), the Democratic Party of the Left or Left Democrats (1991-2006), the Democratic Party (2007-2015) as percentage of the national electorate

Legend: l = PCI, n = PDS/DS; s = PD.

Sources: Own elaboration. Istituto Cattaneo (www.cattaneo.org); Partito Democratico (www.partitodemocratico.it); Pasquino (Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi. 2013. “Post-electoral politics in Italy:

Institutional problems and political perspectives”, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 18 (4): 466-84. Available at:

A similar trend emerges from the analysis of the membership/electoral ratio (ME), which is an indicator of the extent to which the party is anchored in society, that is, at the grassroots level. Up until the late 1980s, the mean party membership for the PCI as percentage of the national electorate was 5.1. With the creation of the PD, this figure has fallen to 0.8 %, which means that less than 1 % of the national electorate is a card-carrying member of the party. Again, this is a common trend elsewhere in Europe, but the pace as well as the extent to which it actually took place in Italy, especially for the left-wing parties, are indeed unique.

As specified above, there are some exceptions to this trend, in particular if one observes the organizational strength and entrenchment of the party at the local/regional level. As shown in table 1, in the central “red” regions of Italy (Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria and Marche), the average ME ratio for the PD in 2013 is 2.1 %, while in the rest of Italy the ratio falls to less than 0.8 %. These figures confirm two aspects. First, that the PD is mainly a geographically concentrated party, with a clearly uneven distribution of staff, members and resources throughout the entire nation. In a way, if the party elites aspire to build a real “Party of the Nation”, widely representative and evenly present on the Italian territory, eventually they should take into account this (dismal) state of affairs. Second, the relatively enduring entrenchment of the party in the central regions of Italy proves a contrario that the organizational efforts, if any, of the party leaders to create a new, nationally widespread party structure, have essentially failed. Or, differently put, it means that the PD has not succeeded in inheriting and preserving the legacy of its predecessors and is moving toward a terra incognita of a new party model, which its leaders are not capable of imagining, defining and constructing.

Table 1.

Membership of the PD and membership ratio in 2012-2013

| PD Membership 2012 | Electorate 2013 | PD Voters 2013 | ME | MV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piemonte | 19,244 | 3,439,197 | 643,863 | 0.6 | 3.0 |

| Valle d’Aosta | 112 | 100,277 | 18,191 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Liguria | 12,510 | 1,274,561 | 258,766 | 1.0 | 4.8 |

| Lombardia | 37,356 | 7,443,321 | 1,467,480 | 0.5 | 2.5 |

| Trentino-Alto Adige | 2105 | 777,135 | 101,216 | 0.3 | 2.1 |

| Veneto | 19,735 | 3,717,087 | 628,166 | 0.5 | 3.1 |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 6091 | 964,045 | 178,001 | 0.6 | 3.4 |

| Emilia-Romagna | 82,098 | 3,338,137 | 989,810 | 2.5 | 8.3 |

| Marche | 11,743 | 1,197,752 | 256,886 | 1.0 | 4.6 |

| Toscana | 62,496 | 2,885,048 | 831,464 | 2.2 | 7.5 |

| Umbria | 16,671 | 683,834 | 168,726 | 2.4 | 9.9 |

| Lazio | 41,333 | 4,430,323 | 852,836 | 0.9 | 4.8 |

| Campania | 40,054 | 4,593,671 | 653,173 | 0.9 | 6.1 |

| Abruzzo | 10,129 | 1,067,298 | 175,857 | 0.9 | 5.8 |

| Molise | 1321 | 262,008 | 42,499 | 0.5 | 3.1 |

| Puglia | 15,110 | 3,297,793 | 407,279 | 0.5 | 3.7 |

| Basilicata | 6,384 | 476,020 | 79,631 | 1.3 | 8.0 |

| Calabria | 28,756 | 1,580,119 | 209,379 | 1.8 | 13.7 |

| Sicilia | 36,894 | 4,076,290 | 467,724 | 0.9 | 7.9 |

| Sardegna | 18,944 | 1,391,515 | 233,278 | 1.4 | 8.1 |

| Total | 469,086 | 46,995,431 | 8,664,225 | 0.9 | 5.4 |

Note: ME = membership as percentage of the national electorate; MV = membership as percentage of PD’s voters.

Sources: Own elaboration. Partito Democratico (www.partitodemocratico.it) and Ministry of Interior (www.interno.gov.it).

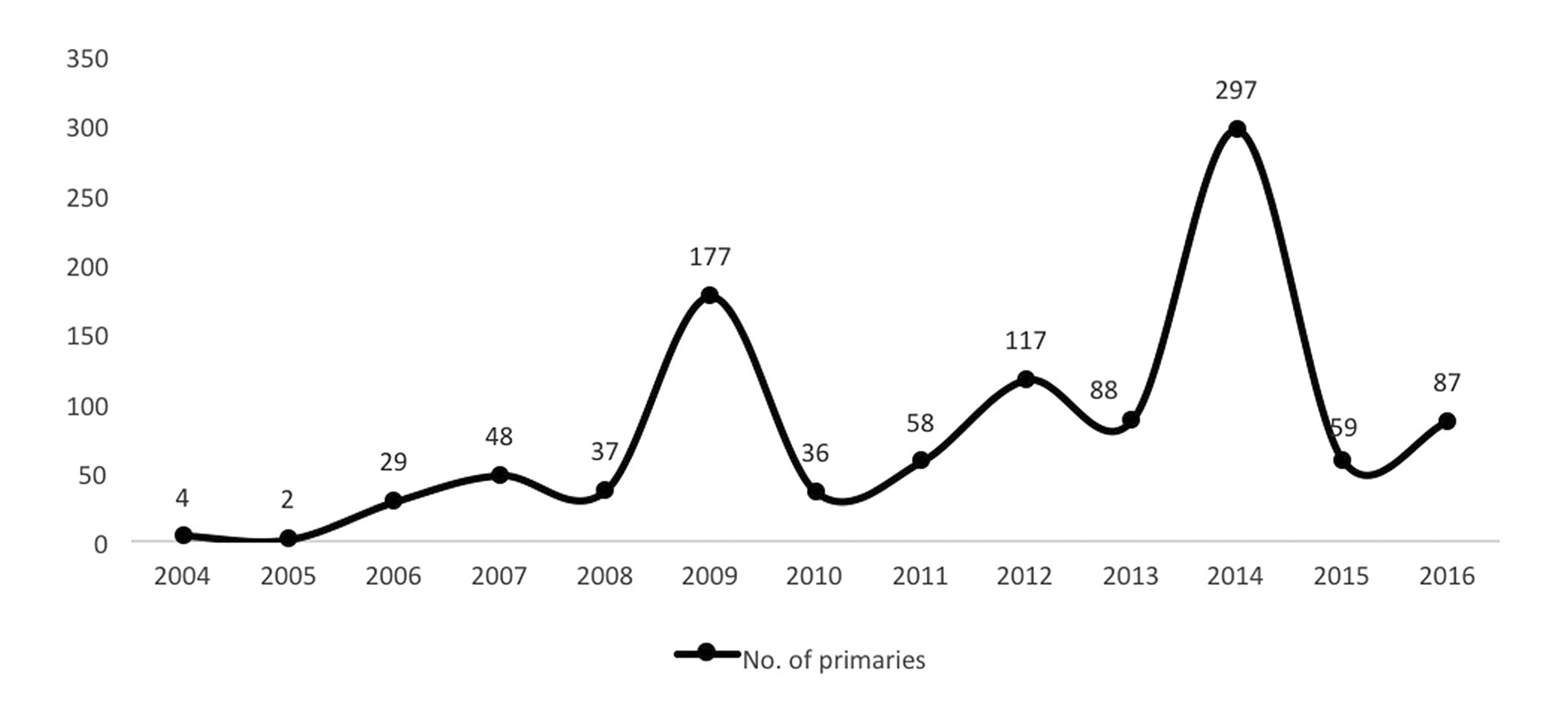

Nonetheless, one significant innovation deserves both credit and a close analysis. According to art. 18 of the PD Statute all candidates to elective public office must be selected through primaries. The election of the party secretary himself/herself is entrusted not just to the party members, but to all those who sympathize with the party’s objectives and approve its platform. They will do so by signing a document (and donating some money) at the time of casting their vote.

Though still controversial, primary elections have been consistently resorted to by

the Democratic Party even, to be precise, before the party came into existence. In

October 2005, Romano Prodi was chosen to become the candidate to the office of Prime

Minister of a coalition soon to be called Unione (The Union) through primary elections (Valbruzzi, Marco. 2015. “In and Out: The Competitiveness of Partito Democratico Leadership

Elections”, in Giulia Sandri and Antonella Seddone (eds.), The Primary Game. Primary elections and the Italian Democratic Party, Novi Ligure: Edizioni Epokè.Valbruzzi, 2015). At the time of our writing (October 2016) “regular” primary elections for mayors

and presidents of the regions organized and held by the PD (or their immediate predecessors)

have reached the quite impressive number of 1.039 at the municipal level (Seddone, Antonella and Marco Valbruzzi. 2012. Primarie per il sindaco. Partiti, candidati, elettori. Milano: Egea.Seddone and Valbruzzi, 2012; Venturino, Fulvio. 2016. “Primarie comunali: mal comune senza gaudio?”, inn Marco

Valbruzzi and Rinaldo Vignati (eds.), Cambiamento o assestamento? Le elezioni amministrative del 2016. Bologna: Istituto Cattaneo.Venturino, 2016) and 17 at the regional level (De Luca, Marino y Stefano Rombi. 2016. “The regional primary elections in Italy”,

Contemporary Italian Politics, 8 (1): 21-41. Available at:

Figure 3.

Number of municipal primaries in Italy, 2004-2016

Source: Candidate and Leader Selection (www.cals.it).

The explosion of primary elections in Italy is thus the product of many, both systemic and individual, factors (Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi (eds.). 2016. “Ten Years After: A Balance-sheet of the Italian Primaries”, Contemporary Italian Politics, 8 (1), special issue: 3-111.Pasquino and Valbruzzi, 2016). Nonetheless, it is a phenomenon that can be fully explained only by making reference to the idea, vaguely entertained by the major party leaders, to build up a so-called “party of the voters”, namely, a political organization in which members and voters share the same powers, rights and duties. This was the party model briefly sketched in the Statute of the party, but repeatedly challenged by the old guard of the PD. So far it has remained just a project on paper.

The initial idea entailed the creation of what Susan Scarrow (Scarrow, Susan E. 2014. Beyond Party Members: Changing Approaches to Partisan Mobilization. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at:

A MULTI-SPEED MEMBERSHIP PARTY?[up]

To a certain extent, all episodes of intra-party competition that have so far taken

place within the Partito Democratico were based on these two different narratives of party legitimacy. On the one hand,

one finds the type of party model promoted by Veltroni and Renzi. It can be defined

as a purely election-oriented vote-seeking political party, according to which the

voters, not the members, are the organizational bottom line. On the other hand, there

lingers the “cleavage representation party”, supported by Bersani and much of the

old guard of the PD, which has “well-defined notions of the group interest to which

members are expected to defer” (Scarrow, Susan E. 2014. Beyond Party Members: Changing Approaches to Partisan Mobilization. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at:

As to the selection of the party secretaries (see table 2), there have been three

instances to date: Veltroni in 2007 (Pasquino, Gianfranco (ed.). 2009. Il Partito Democratico. Elezione del segretario, organizzazione e potere, Bologna: Bononia University Press.Pasquino, 2009); Pier Luigi Bersani in 2008 (Pasquino, Gianfranco and Fulvio Venturino (eds.). 2010. Il Partito Democratico di Bersani. Persone, profilo e prospettive. Bologna: Bononia University Press.Pasquino and Venturino, 2010; Valbruzzi, Marco. 2015. “In and Out: The Competitiveness of Partito Democratico Leadership

Elections”, in Giulia Sandri and Antonella Seddone (eds.), The Primary Game. Primary elections and the Italian Democratic Party, Novi Ligure: Edizioni Epokè.Valbruzzi, 2015); Matteo Renzi in 2013 (Pasquino, Gianfranco and Fulvio Venturino (eds.). 2014. Il Partito Democratico secondo Matteo. Bologna: Bononia University Press.Pasquino and Venturino, 2014). In a way, all three elections have been preceded or followed by traumatic events.

Veltroni’s victory proved to be just one additional factor in the prolonged crisis

of Romano Prodi’s second unfortunate experience in the government (2006-2008). Almost

inevitably, the secretary of the PD, as it had occurred in numerous occasions within

the Christian Democratic party, somewhat felt to be and, in any case, was largely

considered the successor designate of the incumbent Prime Minister. Veltroni’s electoral

and political strategy in the subsequent 2008 national elections led to what was considered

a clear defeat, inevitably followed by his quick abrupt resignation. More complex

was not so much Bersani’s election to the office of party secretary, but his later

designation to the office of Prime Minister at the end of 2012 (Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi. 2013. “Post-electoral politics in Italy:

Institutional problems and political perspectives”, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 18 (4): 466-84. Available at:

Table 2.

Leaders of the Democratic Party, 2007-2017

| Method | Selectorate | Candidates to the party leadership (% of votes) | Secretary | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Direct election | Members and sympathizers | Veltroni (75.8) |

Bindi (12.9) |

Letta (11.0) |

Others (0.3) |

Walter Veltroni |

| 2009 | Congress | Party delegates | Franceschini (91.9) |

Parisi (8.1) |

Dario Franceschini | ||

| 2009 | Direct election | Members and sympathizers | Bersani (53.6) |

Franceschini (33.9) |

Marino (12.5) |

Pier Luigi Bersani | |

| 2013 | Congress | Party delegates | Epifani (85.8) |

Guglielmo Epifani | |||

| 2013 | Direct election | Members and sympathizers | Renzi (65.8) |

Cuperlo (20.5) |

Civati (13.7) |

Matteo Renzi | |

| 2017* | Direct election | Members and sympathizers | Renzi (69.2) |

Orlando (19.9) |

Emiliano (10.9) |

Renzi | |

Sources: Own elaboration. Democratic Party (www.partitodemocratico.it) and Pasquino (Pasquino, Gianfranco. 2013. “Italy”, in Jean M. De Waele, Fabien Escalona y Mathieu Vieira (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Social Democracy in the European Union, Houndmills. Basingstoke: Palgrave, pp. 222-43.2013). Legend: * = the direct election of the Pd leadership was held on 30 April 2017.

Even though the PD’s Statute/Charter is crystal-clear, that is, the party secretary is consequentially and automatically the party’s candidate to the office of Prime Minister, there appeared a challenger: Matteo Renzi, the young newly elected mayor of Florence. Out of a combination of political generosity and of an understandable evaluation of the mobilizational benefits of an open competition, Bersani asked for and, obviously obtained, an ad hoc temporary derogation from the Charter. In a five- candidate field/race Bersani did not garner an absolute majority of votes (44.9 %) and Renzi did much better than expected (35.5 %). Out of 3,110,210 votes cast, Bersani gained only 291,000 votes more than Renzi. In a way, the lack of an absolute majority and the relatively small lead justified yet another exception to the party’s rules. A run-off was held between Bersani and Renzi sanctioning Bersani’s victory (60.9 %), but also highlighting the impressive performance by Renzi (39.1 %). There lingered in the Democratic electorate at large a not so much subterranean dissatisfaction with the ruling group, the old guard of the party. Thanks to a mix of populist discourse and anti-political rhetoric, Renzi’s determination to challenge the old guard and his promise to proceed to its scrapping (rottamazione), as if it were an old car, was substantially rewarded.

Though all this was very interesting and, to our knowledge, unprecedented in European

parliamentary democracies, it may have come to nothing had Bersani not led a very

lackluster electoral campaign for the 2013 national elections. Too much complacent

in his role of front-runner, Bersani did not offer any new policy, but fundamentally

more of the same and much of the same of what the previous non-partisan government

led by the Professor of Economics Mario Monti (Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi. 2012. “Non-partisan governments Italian-style:

decision-making and accountability”, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 17 (5): 612-29. Available at:

Bersani’s inevitable resignation led to yet another contest for the office of party secretary. On December 8, 2013, in a three-person race Renzi obtained a crushing victory (67.7 %). The 22nd of February, 2014, President Napolitano appointed Renzi to replace a sort of Grand Coalition government led by PD Enrico Letta that had lasted less than a year. Renzi became the youngest Prime Minister in the history of the Italian Republic and the first to be at the same time the leader of his party and not a member of Parliament. Since then, the story of the Democratic Party and, perhaps, its destiny have been fully interwoven with what Renzi’s government has done and not done, does and will do. A turning point not to be underestimated, though already considered far away in the past, was represented by the 2014 elections of the European Parliament. Unexpectedly, perhaps just a felicitous instance of a honeymoon with the electorate, the Democratic Party won 40.8 % of the votes (see table 3), more than any other European party (Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi. 2014. “Il Partito democratico: #Renzistasereno”, in Marco Valbruzzi and Rinaldo Vignati (eds.), L’Italia e l’Europa al bivio delle riforme. Le elezioni europee e amministrative del 25 maggio 2014. Bologna: Istituto Cattaneo.Pasquino and Valbruzzi, 2014). In Italy, in national elections, only the Christian Democrats had ever overcome the 40 % threshold. Not without some reason, Renzi’s interpreted this outcome as a personal success. More precisely, the European elections proved, on the one hand, that Renzi had a significant personal appeal, or backing, that goes much beyond that of his party; on the other hand, that the PD under his new galvanizing leadership was in fact capable of attracting voters from other parties, especially center (Civic Choice, Union of the Centre) and right-wing parties (Berlusconi’s Forza Italia).

Table 3.

PD electoral results, 2001-2014

|

Legislative elections (no. and % of votes) |

Seats

(no. and %) |

European elections (no. and % of votes) |

Seats

(no. and %) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 (DS + Daisy) | 11,542,981 31.1 |

211 33.5 |

||

| 2004 (Olive Tree) | 10,077,793 31.1 |

23 29.5 |

||

| 2006 (Olive Tree) | 11,930,983 31.3 |

220 34.5 |

||

| 2008 (PD) | 12,095,306 33.1 |

211 33.5 |

||

| 2009 (PD) | 7,999,476 26.1 |

21 29.2 | ||

| 2013 (PD) | 8,952,200 25.5 |

297 47.1 |

||

| 2014 (PD) | 11,203,231 40.8 |

31 42.5 |

Sources: Own elaboration. Ministry of the Interior (http://elezionistorico.interno.it) and Pasquino (Pasquino, Gianfranco. 2013. “Italy”, in Jean M. De Waele, Fabien Escalona y Mathieu Vieira (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Social Democracy in the European Union, Houndmills. Basingstoke: Palgrave, pp. 222-43.2013).

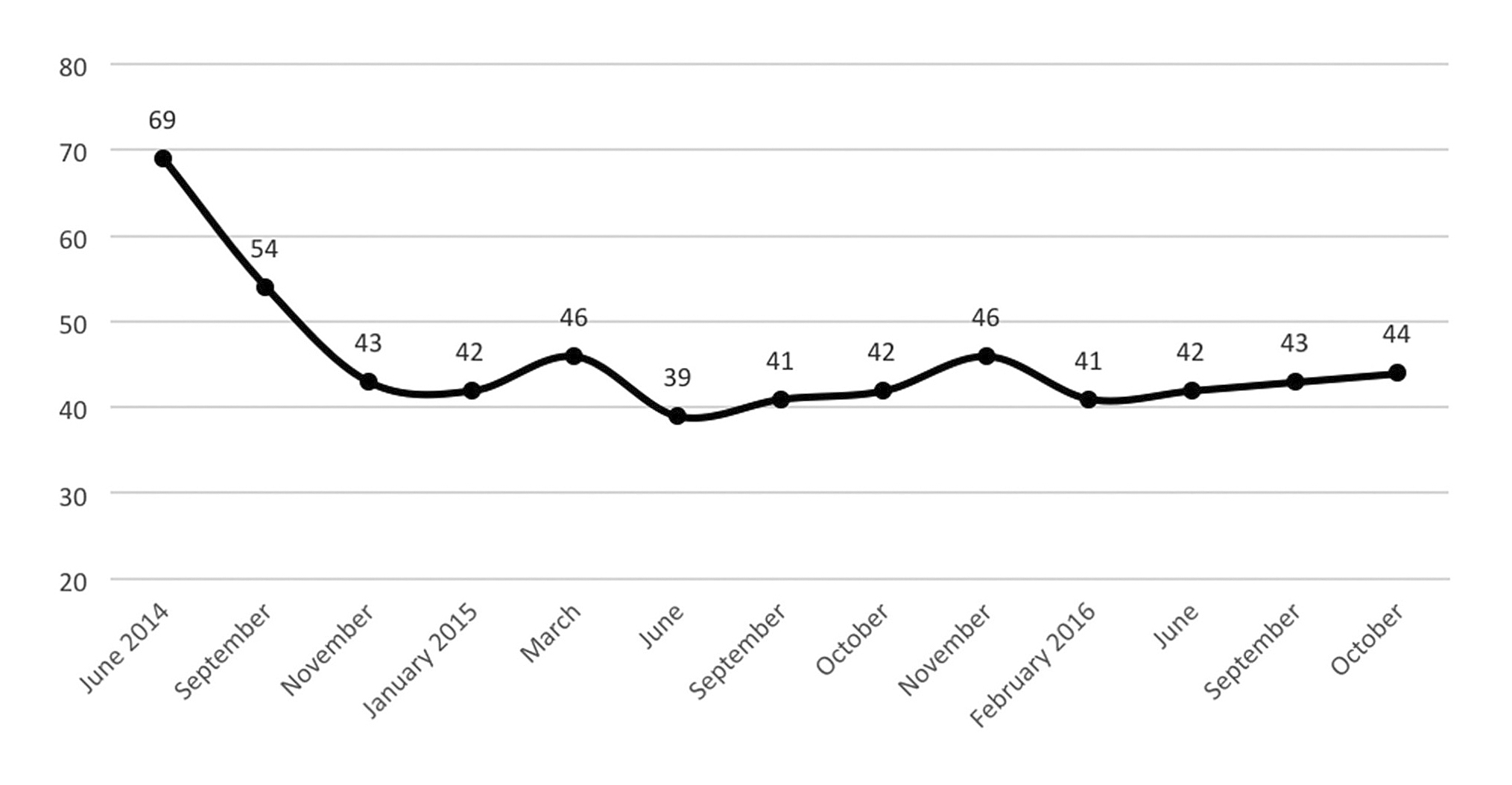

Subsequent, especially local elections have somewhat downsized the electoral strength of the PD and, in particular, the attractiveness of its new leadership. However, following the European elections Renzi seems to have acted as if the party he is leading is more of a hindrance than an instrument to be used to govern and to transform the country because his personal appeal and approval ratings (see figure 4) have constantly transcended the borders of the party’s political confines and electoral capabilities.

By all means, since his “popular” election to secretary of the PD, Renzi has been in full control of his party because the National Assembly reflects in its composition the percentages obtained by the three candidates. More precisely, as table 4 shows, Renzi received 65.8 % of the votes, whereas Cuperlo managed 20.5 % and Civati 14.2 %. These figures make clear that the Secretary had a stronger appeal among the voters at large rather than the “regular” activists of the party. His sort of anti-establishment message, centered on the idea of the so-called “scrapping” of the old(er) party elite, made him the perfect candidate to attract votes from a wider audience made up of light, “irregular” members or sympathizers plus those who were beginning their “electoral” story in those years.

Figure 4.

Renzi’s government approval rating, June 2014-October 2016 (percentage values)

Note: Question “On a scale of 1-10, how would you rate Renzi’s government?”. The figures report the percentage of respondents rating Renzi’s government favorably (that is, with a value greater than or equal to 6). Survey conducted from October, 24 to October 27, 2016 through a combined CATI (Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing), CAMI (Computer Assisted Mobile Interviewing) and CAWI (Computer Assisted Web Interviewing) method. The sample (N = 1.213) is representative of the overall Italian electorate. The margin of error of ± 2.8 %.

Source: Demos and Pi (http://www.demos.it/a01315.php?ref=HREC1-9). For more details, see Diamanti (Diamanti, Ilvo. 2016. “A un mese dal voto in vantaggio il No, il Pd si compatta intorno al premier”, la Repubblica, 30-10-2016.2016).

Slightly less uneven is Renzi’s control of the party on the ground where there were

major waves of allegiance transfers from the old guard to the new rulers. As a consequence,

while some dissent may still appear here and there, one cannot find true “rebellions”,

that is, cases and contexts in which local parties have openly opposed the party line

or openly criticized the party secretary. Renzi’s sore points have been the Chamber

and, even more so, the Senate parliamentary groups. Because of the electoral law,

party lists are closed, that is, all candidates have been elected following their

ranking on the lists. Obviously, being party secretary at the time of the drafting

of the lists of candidates, Bersani with his collaborators exercised a strong/decisive

influence in the appointment and ranking of the candidates even though several so

called “parliamentary primaries” were held (Regalia, Marta and Marco Valbruzzi. 2016. “With or without parliamentary primaries?

Some evidence from the Italian laboratory”, Contemporary Italian Politics, 8 (1): 42-61. Available at:

Table 4.

Results of the 2013 direct leadership election (% values)

| Regions | Matteo Renzi | Gianni Cuperlo | Giuseppe Civati |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valle d’Aosta | 64.2 | 15.2 | 20.6 |

| Piemonte | 70.2 | 14.1 | 15.7 |

| Lombardia | 67.8 | 14.9 | 17.3 |

| Liguria | 62.8 | 19.5 | 17.7 |

| North-west regions | 67.6 | 15.3 | 17.1 |

| Trentino-Alto Adige | 67.5 | 13.8 | 18.7 |

| Veneto | 68.8 | 14.9 | 16.3 |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 66.2 | 17.9 | 15.9 |

| Emilia-Romagna | 71.6 | 14.9 | 13.5 |

| North-east regions | 69.5 | 15.2 | 15.3 |

| Toscana | 77.4 | 12.3 | 10.3 |

| Marche | 76.2 | 10.7 | 13.1 |

| Umbria | 73.6 | 16.1 | 10.3 |

| Lazio | 65.5 | 21.2 | 13.3 |

| Abruzzo | 67.4 | 20.1 | 12.5 |

| Central regions | 74.0 | 14.5 | 11.5 |

| Molise | 62.1 | 29.6 | 8.3 |

| Puglia | 60.3 | 24.5 | 15.2 |

| Basilicata | 58.3 | 33.7 | 8.0 |

| Campania | 60.7 | 30.8 | 8.5 |

| Calabria | 58.4 | 33.3 | 8.3 |

| Southern regions | 61.6 | 27.2 | 11.2 |

| Sicilia | 61.3 | 27.4 | 11.3 |

| Sardegna | 55.6 | 25.4 | 19.0 |

| Islands | 59.4 | 26.7 | 13.9 |

| Total Italy | 65.8 | 20.5 | 13.7 |

It is true that few deputies and senators have decided to leave the PD parliamentary group (among them Civati who has launched a political movement called “Possibile”, clearly referring to Podemos), but other deputies and senators, coming, for instance, from the Five Star Movement, have joined the PD parliamentary groups. But what really counts is that none of the dissenting Democratic parliamentarians has prevented the government from obtaining what Renzi firmly desired and imposed. Of course, half of the 463 laws approved between March 15, 2013 and June 15, 2016 have been approved because of a strict enforcement of party discipline, but not even on the constitutional reforms and the electoral law the so-called minorities of the PD have either attempted or succeeded in disrupting the course of the government.

ELECTORAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS[up]

Repeatedly, Renzi has claimed that his government’s raison d’être is to make the constitutional reforms (and, subordinately, to revise the electoral

law). He has gone so far as to stress that the reform of the Constitution is the mandate

given to him by former President Giorgio Napolitano. A close analysis of the process

of the reforms that have been formulated and approved, and of the referendum campaign

launched and personally conducted by Renzi can reveal a lot concerning the Democratic

Party, its political role, its leadership, its future (Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi. 2017. “Italy Says No: The 2016 Constitutional

Referendum and its Consequences”, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 22 (2): 145-62. Available at:

According to article 138 of the Italian Constitution, all constitutional revisions, if not approved by a parliamentary majority of two thirds, may be (but do not have to be) submitted to a referendum provided one fifth of the parliamentarians or five regional councils or five hundred thousand voters request it. From the very beginning and at all times they felt it necessary, Renzi and his Minister of Institutional Reforms stressed that, in any case, the government was going to call a referendum. From the very beginning and for several months up to the end of August 2016, Renzi vehemently stressed that if “his” reforms will not be confirmed by the voters, he would resign and leave political life so that a serious political crisis would follow. It was only after some criticisms of his plebiscitarian posture/blackmail reached the ears of especially President Napolitano who suggested that the Prime Minister had probably exceeded in his personal politicization/political personalization of the referendum, that Renzi has somewhat receded from his propaganda statements (taken too seriously by foreign economic operators and major economic newspapers). Despite his delayed attempts to progressively deactivate the plebiscitarian threat, the Italian voters used the constitutional referendum also to express their evaluation of the performance of the Prime Minister and their disapproval of his policies.

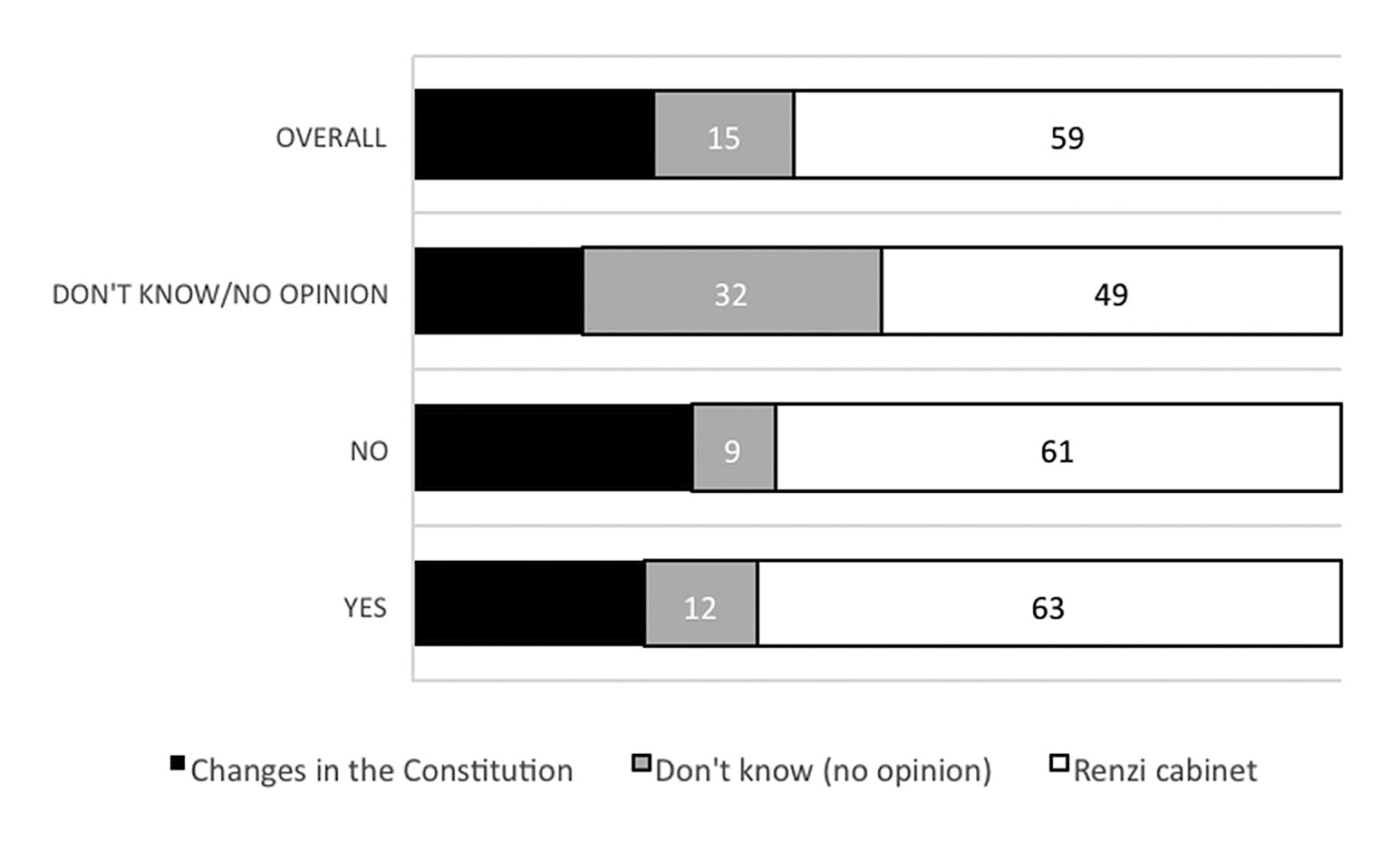

In any case, for many voters the issue had already irreversibly become personalized. A Yes vote meant supporting Renzi and his government; a No vote implied also the rejection of Renzi and his government. As shown in figure 5, the majority of voters counter-reacted to the personalized campaign conducted by the PD leader by adopting a similar personalized logic of voting. More precisely, according to the opinion of the electorate, from both sides of the confrontation, six voters out of ten used the referendum as an instrument to either keep in or kick out of office the incumbents. Inevitably, the most immediate consequence of the referendum result was, as indicated above, the resignation of Renzi’s cabinet and then the overt contestation of his leadership within the Democratic Party. A circumstance that, for the moment, has put a brake on Renzi’s ambitions to transform the party into his own personal political vehicle.

Figure 5.

The meaning of the constitutional referendum according to the Italian electorate (% values)

Note: Question: ‘According to you, Italian voters will express their vote on the constitutional referendum on the basis of…’. Survey conducted in two waves (October and November 2016) through a combined CATI (Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing), CAMI (Computer Assisted Mobile Interviewing) and CAWI (Computer Assisted Web Interviewing) method. The sample (N = 2,400) is representative of the overall Italian electorate. The margin of error of ± 2.8 %.

Source: Bordignon, Ceccarini and Diamanti (Bordignon, Fabio, Luigi Ceccarini and Ilvo Diamanti. 2017. LLItalia dei Sì e lIItalia del No. Evoluzione e profilo del voto referendario, in Andrea Pritoni, Marco Valbruzzi y Rinaldo Vignati (eds.), La prova del No. Il sistema politico italiano dopo il referendum costituzionale. Soveria Mannelli: Rubbettino.2017: 141).

The referendum strategy had never been discussed in the National Assembly of the Democratic Party, but the message sent to the “minorities” within the PD was very simple and precise: they were asked not only to vote Yes to the reforms, but also to organize Committees in support of those reforms. The new political class of the Democrats would emerge and be recruited from those committees and on the basis of their commitment. A promise or a threat that were made credible by the existing electoral law and its closed lists of parliamentary candidates.

The reform of the electoral law was originally drafted in collaboration with Berlusconi

whose electoral law, used in 2006, 2008, and 2013, had been declared unconstitutional

by the Constitutional Court. The so-called Italicum shares many features with the

previous electoral law (and, in fact, has met the same electoral fate of its predecessor,

being partially rejected by the Constitutional Court), but for our purposes, that

is, understanding and explaining the role and the goal of the Democratic Party, one

feature and one mechanism have an overriding importance (Pasquino, Gianfranco. 2015. “Italy has yet another electoral law”, Contemporary Italian Politics, 7 (3): 293-300. Available at:

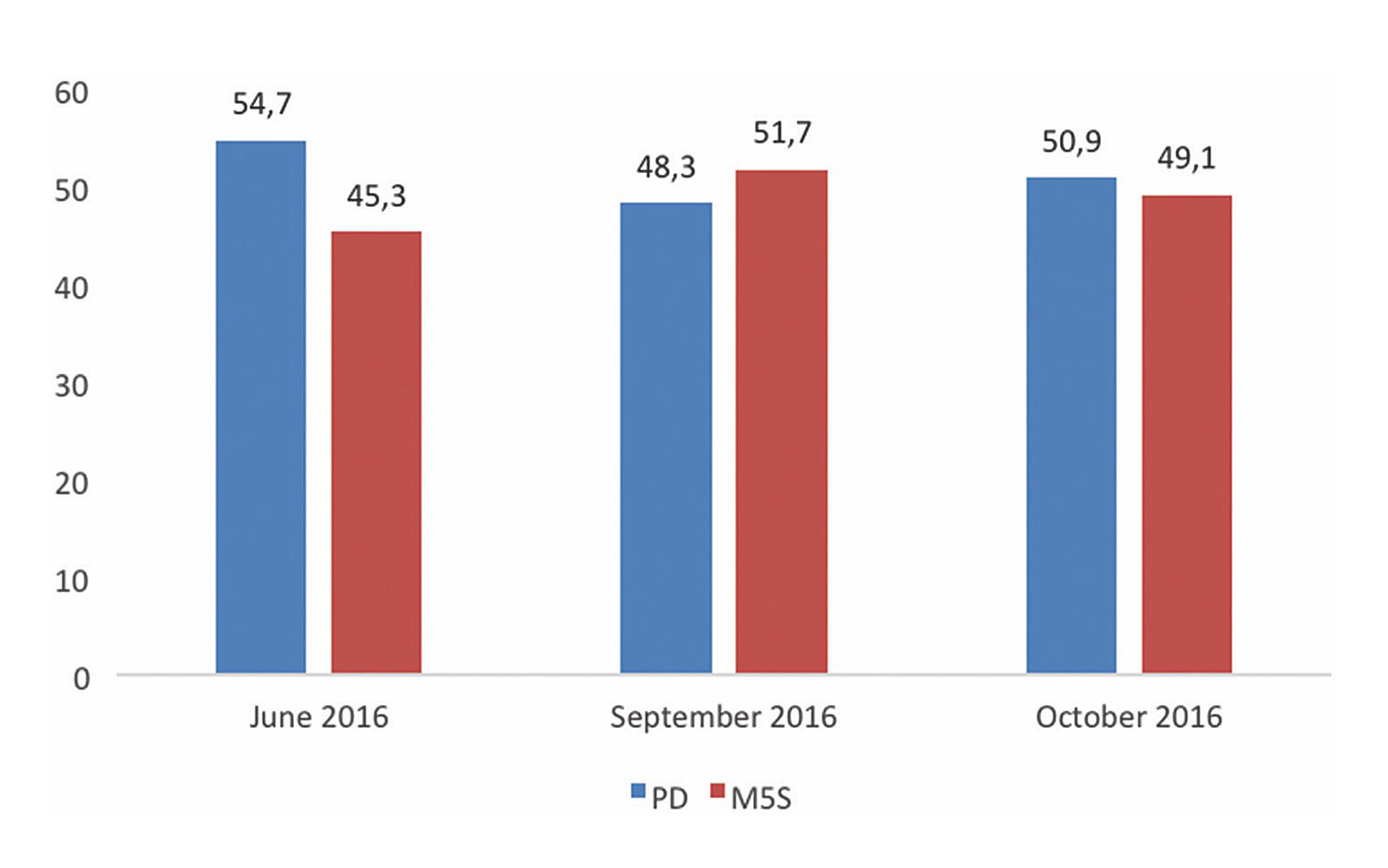

Berlusconi accepted the mechanism of the run-off when it still appeared possible that his party could obtain enough votes to be the second Italian party. Since the approval of the law and after several municipal elections, not only do all the data suggest that the Five Stars Movement is solidly behind the PD, but that in a run-off it may even obtain enough votes to defeat Renzi’s party. Hence, after having repeatedly declared that the Italicum is an excellent electoral law for which many European systems prove admiration and envy and that they will soon imitate, a bizarre situation has followed. In order to avoid a likely victory by the anti-establishment and surely catch-all Five Star Movement, how to reform the reform, that is, an electoral law not yet utilized and already changed or corrected by the Constitutional Court, has become the new game in town.

The main reason behind the idea of a sizable seat bonus to the winning party is to assure the governability that, according to the proponents, litigious Italian coalitions have not been able to provide. Renzi’s paramount goal was and remains that of obtaining a single party parliamentary majority, possibly made exclusively of loyal supporters, allowing him to govern alone. Throughout the discussion of the electoral law and the constitutional reforms, the project of a new, though never fully designed, party appeared: the Party of the Nation.

A NEW PARTY FOR THE NATION[up]

Since 1994[1], the Italian party system has been in disarray (Morlino, Leonardo. 1996. “Crisis of parties and change of party system in Italy”,

Party Politics, 2 (1): 5-30. Available at:

Figure 6.

Voting intentions in the hypothetical run-off election between Democratic Party (PD) and Five Star Movement (M5S), 2016 (percentage values)

Note: Question “In case of run-off election between PD and M5S, which party would you vote for?”. Survey conducted from October, 24 to October 27, 2016 through a combined CATI (Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing), CAMI (Computer Assisted Mobile Interviewing) and CAWI (Computer Assisted Web Interviewing) method. The sample (N = 1.213) is representative of the overall Italian electorate. The margin of error of ± 2.8%.

Source: Demos and Pi (http://www.demos.it/a01315.php?ref=HREC1-9). For more details, see Diamanti (Diamanti, Ilvo. 2016. “A un mese dal voto in vantaggio il No, il Pd si compatta intorno al premier”, la Repubblica, 30-10-2016.2016).

In order to understand and appreciate how the PD has reacted, it is important to explain the impact and the consequences of two events and developments. The first one has to do with the absolute necessity to reform the existing electoral law whose several features have been declared unconstitutional by a sentence of the Constitutional Court n. 1/2014. The second event is to be considered at the same time a short-term reaction to the political situation and a not fully thought-through strategy.

In Italy more than elsewhere, with the likely exception of France, reforms of the electoral law have been drafted in a highly partisan manner in order to redefine political parties, electoral coalitions, the overall party system. This was also the case of the 1993 electoral law dubbed Mattarellum because its rapporteur was Sergio Mattarella (since 2015 President of the Italian Republic). Indeed, the transition from a PR law to a law in which three fourths of the parliamentarians had to be elected in single-member constituencies produced not only a bipolar competition, but, for the first time in Italian history, put the premises of that precious, until then unachieved, outcome that is represented by alternation in the government (Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi (eds). 2011. Il potere dell’alternanza. Teorie e ricerche sui cambi di governo. Bologna: Bolonia University Press.Pasquino and Valbruzzi, 2011). Also, it obliged Italian parties to coalesce and granted small parties a significant coalitional/blackmail power (Sartori, Giovanni. 1976. Parties and Party Systems. A Framework for Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University PressSartori, 1976) because in single-member constituencies their votes could, and often did, make a difference. Thus, the electoral law drafted by Renzi and initially accepted by Berlusconi was also meant to reduce, even, if at all possible, to eliminate the small parties’ blackmail power (for the most significant technicalities, see Pasquino, 2015). But the requirement introduced in the 2014 law e.g. that, for a party to win the majority bonus, it must obtain 40 % of the votes plus one, means that both Renzi and Berlusconi will be obliged to find some allies well before the vote.[2]

Those who had given birth to the Partito Democratico and, before them, some of the participants in the umbrella organization called Ulivo (Olive Tree), had entertained the idea of shaping a party with a majoritarian vocation. Incidentally, apparently unknown to most of them, the same vocation/aspiration was formulated several decades before by Palmiro Togliatti, the leader of the Italian Communist Party. The majoritarian vocation consists of two components. The first one, much too simple, was that the party aimed at obtaining the highest possible number of votes (vote-seeking) getting rid of any ideological baggage whatsoever that might negatively impinge on its electoral appeal. The second, less simple, but clear component was that the party had to declare itself unwilling to join any coalition, because it wanted to run alone without being encumbered by small greedy parties. This is exactly what the first Secretary of the Partito Democratico, Walter Veltroni, did in the 2008 elections. He won a very high percentage of votes (33.1 %, see table 3), though still less than Enrico Berlinguer’s PCI in 1976, but was resoundingly defeated by Berlusconi’s political vehicle, at the time called Popolo della Libertà.

In a subtle, or just improvised way, the idea of yet a party with a majoritarian vocation made its reappearance in the circles around Prime Minister Renzi. In particular, this idea was vaguely inspired by the work of Maurice Duverger (Duverger, Maurice. 1954. Political Parties. Theoir Organization and Activity in the Modern State. London: Methuen.1954) on the organization and strength of political parties. According to the French scholar, three types of parties can be distinguished on the basis of their electoral strength: minor parties, major parties and parties with a majority bent. The latter category applies to those parties “which command an absolute majority in parliament or are likely to be able to command one at some date in the normal play of institutions” (Duverger, Maurice. 1954. Political Parties. Theoir Organization and Activity in the Modern State. London: Methuen.Duverger, 1954: 284). More precisely, for this majoritarian party, which is the norm in two-party systems and can also make their appearance in moderate or bipolar party systems, “it is likely at some date to have to shoulder alone the responsibilities of government” (ibid.). This idea of a party with a majority bent, especially in the highly fragmented context of the Italian party system, was mostly misinterpreted and forgot by the founders of the Partito Democratico. A “majority bent” does not imply the necessity nor the capability for a party to represent the whole nation. It simply means that there exists a party which finds itself in the position to control, for a more or less limited period of time, a majority of seats in parliament and, in the light of this, is willing to govern alone.

By contrast, the idea, the “emotional” label, the prospect of becoming a party truly representing the entire Nation, though mission impossible, was entertained, cherished and widely exhibited. Never mind that some, however few, commentators pointed to the important historical experience of Italian Christian Democracy that, though in fact largely representing the “nation”, was always quite open and willing to reach, include, and reward the political allies. Never mind, too, that the “occupation” of the center of the Italian political spectrum by the DC has prevented the occurrence of any alternation in government, mainly for international reasons. Never mind, finally, that, indeed, power corrupts and that the DC had ended in collapse. Born to provide a viable alternative to Berlusconi and his recurrent conquest of political power and prolonged governmental rule, the PD, at least, its secretary, his collaborators and several political commentators were willing to run all the risks entailed in the transformation leading to the Party of the Nation and its subsequent attempt to govern the country, presumably not severely challenged by any competitor.

Even though the PD in Parliament has accepted and “rewarded” the votes by parliamentarians elected in the ranks of Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, the project for a Party of the Nation has made little headway so far. It has ultimately remained a project on paper or in the mind of the party elite, but it has found virtually no response among citizens and voters. As table 5 makes evident, the PD is still the favorite party for those citizens who identify themselves as left-wing voters. Renzi’s PD appeal to non-leftist voters is rather limited and approximately only one-third of its potential electorate comes from centrist and right-wing citizens. From this perspective, the truly “national” political party in Italy is not Renzi’s PD but, interestingly enough, Beppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement, whose actual and potential electorate is quite homogeneously distributed throughout the entire political spectrum, including also those voters that reject the twentieth-century left-right dimension of competition.

Table 5.

Voters’ left/right self-placement by voting intentions, 2015 (% values)

| Voter’s self-placement | Partito Democratico | Five Star Movement | Overall electorate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left | 70.9 | 36.3 | 41.3 |

| Center | 16.4 | 27.3 | 18.1 |

| Right | 9.2 | 20.8 | 32.0 |

| Neither left nor right | 3.5 | 15.6 | 8.6 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Note: Survey conducted from November, 16 to November 24, 2015 through a combined CATI

(Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing) and CAMI (Computer Assisted Mobile Interviewing)

method. The sample (N = 1.522) is representative of the overall Italian electorate.

Confidence level at 95 % with a margin of error of ± 2.5 %. For more details, see

Emanuele and Maggini (Emanuele, Vincenzo and Nicola Maggini. 2015. Il Partito della Nazione? Esiste e si chiama Movimento 5 Stelle. Available at:

Source: Own elaboration.

The June 2016 local elections, characterized by the poor and quite disappointing results

of the PD candidates and lists (Morini, Mara and Andrea Pritoni. 2016. “Il Pd: #menosereno”, in Marco Valbruzziy Rinaldo

Vignati (eds.), Cambiamento o assestamento? Le elezioni amministrative del maggio 2016, Bologna: Istituto Cattaneo.Morini e Pritoni, 2016), dealt a major, but not necessarily decisive blow to the idea/project of the Party

of the Nation. In any case, no lesson was learned. No attempt has been made so far

to reorganize the party along neither well-known traditional criteria nor new criteria.

Launching his campaign on the referendum concerning constitutional reforms , the secretary

of the party stated that the new Democratic Party “ruling” class would emerge from

the “Committees for the Yes vote”, probably in an attempt to appeal to outside ambitious

women and men rather than (re)mobilize PD activists. In spite of repeatedly making

reference to some reforms –the job market, the educational system, the incomplete

restructuring of the Italian bureaucracy–, the PD cannot be characterized as a policy-seeking

party. The vote-seeking nature of the party and, in particular, the office-seeking

attitude of its single-minded elite completely obfuscated the programmatic orientation

of the PD. If a policy-seeking party is defined by the fact that it gives absolute

priority to its policies (Wolinetz, Steven B. 2002. “Beyond the Catch-all Party: Approaches to the Study of

Parties and Party Organization in Contemporary Democracies”, in Juan Linz, José Ramon

Montero and Richard Gunther (eds.), Political Parties: Old Concepts and New Challanges, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 136-65. Available at:

CONCLUSION: PARTY AND GOVERNMENT[up]

Notwithstanding the opposition from a few weak internal factions, there can be no doubt that the Italian Democratic Party is today almost exactly, what its secretary, Matteo Renzi, wants it to be. As long as Renzi was also the Prime Minister of Italy, the party organization as such enjoyed practically no autonomy from the government and its policies. Few exceptional moments and instances aside, the Democratic Party local power holders work as a transmission belt of what the PD does in the government. Though too many Italians often boast that their country is either a laboratory in which political and institutional transformations start or which anticipates events that will take place in other parliamentary democracies, what is occurring in the Partito Democratico can be explained with reference both to an old, but revered, model and to a new, rather widespread, phenomenon. By all standards, the Partito Democratico is more than anything else a catch-all party of the type identified by Kirchheimer, more precisely a vote and office-seeking political instrument. All the catch-all features characterize its structure, its leadership, its policies. Moreover, the Partito Democratico also fits especially well among the personalist parties that have appeared in many contemporary democratic regimes. To some extent, the PD is also trying to construct a multi-speed membership organization, which combines, in different forms and degrees, the constant commitment to the party activities by “old” militants with the more erratic engagement of new “light members” or sympathizers. However, as we have stressed throughout this article, there is no established, widely accepted, overarching model for the PD. To date, the Democratic Party remains a party made up of many models, oftentimes in contradiction with one another. This wealth of models, platforms and projects is not an indicator of party strength, but reveals the uncertainty and the persistent inability to endow the party with a stable structure. To some extent, this state of affairs within the PD is also a function of the whole Italian party system still stuck in a never-ending political and institutional transition. As long as the Italian transition will not find a more stable anchorage, the Democratic Party too will be at the mercy of different and contradictory incentives. It is still too early to assess both the validity and durability of this experiment in party engineering, but the evidence collected thus far shows that the survival of the PD will rest on very shaky grounds unless a coherent party model prevails over the alternative models.

AFTERMATH[up]

Two major events have significantly affected the Democratic Party between December 2016 and May 2017. Having invested much of his political prestige and reformist aura on the referendum on constitutional reforms, to the point that the referendum had almost become a plebiscite on his person, Matteo Renzi immediately resigned from Prime Minister and party secretary following the crushing defeat on December 4, 2016. Soon afterwards a new government was formed led by Democrat Paolo Gentiloni, who only replaced a couple of ministers but has run the government in total continuity with the previous one. For his part, Renzi and his collaborators launched the procedures to elect the new secretary for the Partito Democratico looking for a political comeback and in an attempt to regain full control of the party. The reconquista became even more important after months and months of quarrels and clashes (and defeats), when some sectors of the Democratic Party, led by former Secretary Pier Luigi Bersani, decided to leave the PD (February 2017). It is impossible to evaluate how much has this split affected the PD. In any case, Renzi went on and easily won the re-election as secretary with slightly less than 70 % of the votes. When the PD lost badly the June 2017 local elections, several voices within and around the party made themselves heard criticizing Renzi’s leadership style, substance, strategy. Both the PD and several left-wing groups “circulating” around it appear not well positioned on their way to the February/March 2018 national elections. The Italian Left and the Democratic Party may not (yet) be in disarray, but their future is not promising, either.

Notes[up]

| [1] |

We take as a cut-off point the date of the national elections held with a new largely majoritarian electoral law. |

| [2] |

This requirement (run-off voting), as well as the possibility for the top candidates standing in multiple constituencies to freely choose his/her favourite election constituency, have been struck down by the decision of the Constitutional Court issued on January, 25. In doing so, the Court sent a powerful message to Parliament to draft laws more respectful of the need to provide good representation to the Italian voters. |

References[up]

|

Bordandini, Paola, Aldo Di Virgilio y Francesco Raniolo. 2008. “The Birth of a Party: The Case of the Italian Partito Democratico”, South European and Politics, 13 (3): 303-24. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13608740802349472. |

|

|

Bordignon, Fabio. 2014. “Matteo Renzi: A ‘Leftist’ Berlusconi for the Italian Democratic Party?”, South European Society and Politics, 19 (1): 1-23. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2014.887240. |

|

|

Bordignon, Fabio and Luigi Ceccarini. 2013. “Five Stars and a Cricket. Beppe Grillo Shakes Italian Politics”, South European Society and Politics, 18 (4): 427-49. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2013.775720. |

|

|

Bordignon, Fabio, Luigi Ceccarini and Ilvo Diamanti. 2017. LLItalia dei Sì e lIItalia del No. Evoluzione e profilo del voto referendario, in Andrea Pritoni, Marco Valbruzzi y Rinaldo Vignati (eds.), La prova del No. Il sistema politico italiano dopo il referendum costituzionale. Soveria Mannelli: Rubbettino. |

|

|

Calise, Mauro. 2015. “The personal party: an analytical framework”, Italian Political Science Review, 45 (3): 310-15. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2015.18. |

|

|

Corbetta, Piergiorgio and Elisabetta Gualmini (eds.). 2013. Il Partito di Grillo. Bologna: Il Mulino. |

|

|

De Luca, Marino y Stefano Rombi. 2016. “The regional primary elections in Italy”, Contemporary Italian Politics, 8 (1): 21-41. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2016.1153827. |

|

|

Diamanti, Ilvo. 2016. “A un mese dal voto in vantaggio il No, il Pd si compatta intorno al premier”, la Repubblica, 30-10-2016. |

|

|

Duverger, Maurice. 1954. Political Parties. Theoir Organization and Activity in the Modern State. London: Methuen. |

|

|

Emanuele, Vincenzo and Nicola Maggini. 2015. Il Partito della Nazione? Esiste e si chiama Movimento 5 Stelle. Available at: http://cise.luiss.it/cise/2015/12/07/il-partito-della-nazione-esiste-e-si-chiama-movimento-5-stelle/ [consulta: 21 de marzo de 2017]. |

|

|

Floridia, Antonio. 2009. “Modelli di partito e modelli di democrazia: analisi critica dello Statuto del PD”, in Gianfranco Pasquino (ed.), Il Partito Democratico. Elezione del segretario, organizzazione e potere. Bologna: Bononia University Press. |

|

|

ITANES. 2013. Voto amaro. Disincanto e crisi economica nelle elezioni del 2013. Bologna: Il Mulino. |

|

|

Katz, Richard S., Peter Mair et al. 1992. “Membership of political parties in European Democracies, 1960-1990”, European Journal of Political Research, 22 (3): 329–45. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1992.tb00316.x. |

|

|

Kirchheimer, Otto. 1966. The Transformation of the Western European Party Systems, in Joseph LaPalombara y Myron Weiner (eds.), Political Parties and Political Development. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 177-200. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400875337-007. |

|

|

Kostadinova, Tatiana and Barry Levitt. 2014. “Towards a Theory of Personalist Parties: Concept Formation and Theory Building”, Politics and Policy, 42 (4): 490-512. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12081. |

|

|

Morini, Mara and Andrea Pritoni. 2016. “Il Pd: #menosereno”, in Marco Valbruzziy Rinaldo Vignati (eds.), Cambiamento o assestamento? Le elezioni amministrative del maggio 2016, Bologna: Istituto Cattaneo. |

|

|

Morlino, Leonardo. 1996. “Crisis of parties and change of party system in Italy”, Party Politics, 2 (1): 5-30. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068896002001001. |

|

|

Panebianco, Angelo. 1988. Political Parties: Organization and Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

|

|

Pasquino, Gianfranco. 2013. “Italy”, in Jean M. De Waele, Fabien Escalona y Mathieu Vieira (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Social Democracy in the European Union, Houndmills. Basingstoke: Palgrave, pp. 222-43. |

|

|

Pasquino, Gianfranco. 2015. “Italy has yet another electoral law”, Contemporary Italian Politics, 7 (3): 293-300. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2015.1070513. |

|

|

Pasquino, Gianfranco (ed.). 2009. Il Partito Democratico. Elezione del segretario, organizzazione e potere, Bologna: Bononia University Press. |

|

|

Pasquino, Gianfranco and Fulvio Venturino (eds.). 2010. Il Partito Democratico di Bersani. Persone, profilo e prospettive. Bologna: Bononia University Press. |

|

|

Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi. 2010. “A che punto è il PD? Analisi organizzativa di un amalgama malriuscito”, in Gianfranco Pasquino y Fulvio Venturino (eds.), Il Partito Democratico di Bersani. Persone, profilo e prospettive. Bologna: Bolonia University Press. |

|

|

Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi (eds). 2011. Il potere dell’alternanza. Teorie e ricerche sui cambi di governo. Bologna: Bolonia University Press. |

|

|

Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi. 2012. “Non-partisan governments Italian-style: decision-making and accountability”, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 17 (5): 612-29. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1354571X.2012.718568. |

|

|

Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi. 2013. “Post-electoral politics in Italy: Institutional problems and political perspectives”, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 18 (4): 466-84. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1354571X.2013.810805. |

|

|

Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi. 2014. “Il Partito democratico: #Renzistasereno”, in Marco Valbruzzi and Rinaldo Vignati (eds.), L’Italia e l’Europa al bivio delle riforme. Le elezioni europee e amministrative del 25 maggio 2014. Bologna: Istituto Cattaneo. |

|

|

Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi. 2015. A Changing Republic. Politics and Democracy in Italy. Novi Ligure: Edizioni Epokè |

|

|

Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi (eds.). 2016. “Ten Years After: A Balance-sheet of the Italian Primaries”, Contemporary Italian Politics, 8 (1), special issue: 3-111. |

|

|

Pasquino, Gianfranco and Marco Valbruzzi. 2017. “Italy Says No: The 2016 Constitutional Referendum and its Consequences”, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 22 (2): 145-62. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1354571X.2017.1286096. |

|

|

Pasquino, Gianfranco and Fulvio Venturino (eds.). 2014. Il Partito Democratico secondo Matteo. Bologna: Bononia University Press. |

|

|

Poguntke, Thomas, Susan E. Scarrow and Paul Webb. 2016. “Party rules, party resources and the politics of parliamentary democracies: How parties organize in 21st century”, Party Politics, 22 (6): 661-78. Available at: https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1354068816662493. |

|

|

Pritoni, Andrea, Marco Valbruzzi and Rinaldo Vignati (eds.). 2017. La prova del No. Il sistema politico italiano dopo il referendum costituzionale. Soveria Mannelli: Rubbettino. |

|

|

Regalia, Marta and Marco Valbruzzi. 2016. “With or without parliamentary primaries? Some evidence from the Italian laboratory”, Contemporary Italian Politics, 8 (1): 42-61. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2016.1153828. |

|

|

Russo, Federico. 2015. “Two steps forward and one step back: the majority principle in the Italian Parliament since 1994”, Contemporary Italian Politics, 7 (1): 27-41. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2014.1002245. |

|

|

Sartori, Giovanni. 1976. Parties and Party Systems. A Framework for Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press |

|

|

Scarrow, Susan E. 2014. Beyond Party Members: Changing Approaches to Partisan Mobilization. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199661862.001.0001. |

|

|

Seddone, Antonella and Marco Valbruzzi. 2012. Primarie per il sindaco. Partiti, candidati, elettori. Milano: Egea. |

|

|

Tronconi, Filippo (ed.). 2015. Beppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement. Farnham: Ashgate. |

|

|

Valbruzzi, Marco. 2015. “In and Out: The Competitiveness of Partito Democratico Leadership Elections”, in Giulia Sandri and Antonella Seddone (eds.), The Primary Game. Primary elections and the Italian Democratic Party, Novi Ligure: Edizioni Epokè. |

|

|

Van Biezen, Ingrid, Peter Mair and Thomas Poguntke. 2012. “Going, going, gone? The decline of party membership in contemporary Europe”, European Journal of Political Research, 51 (1): 24-56. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.01995.x. |

|

|

Venturino, Fulvio. 2016. “Primarie comunali: mal comune senza gaudio?”, inn Marco Valbruzzi and Rinaldo Vignati (eds.), Cambiamento o assestamento? Le elezioni amministrative del 2016. Bologna: Istituto Cattaneo. |

|

|

Wolinetz, Steven B. 2002. “Beyond the Catch-all Party: Approaches to the Study of Parties and Party Organization in Contemporary Democracies”, in Juan Linz, José Ramon Montero and Richard Gunther (eds.), Political Parties: Old Concepts and New Challanges, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 136-65. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/0199246742.003.0006. |