The social base and career development of Spanish mayors

La base social y el desarrollo de carrera de los alcaldes españoles

ABSTRACT

The growing corpus of studies about political elites in Spain has tended to focus on national and regional parliaments and executives, rather than on the municipal level of government. And yet, it is in these local settings that politicians acquire skills and political experience, develop their notions of democracy, and often start their political careers. Exploring patterns of political recruitment in Spanish local democracies allows us to look at some of the literature findings on this topic and check whether they also apply at the municipal level in Spain, enhancing in this way our understanding of who governs our cities, too. This article analyzes Spanish mayors’ social profiles, their patterns of professionalization and their political ambitions, trying to address questions such as: do municipal leaders share a common background? Are they amateurs or professionals in politics? Is the municipal level the first stage of an identifiable political career of Spanish representatives? In responding to these questions, this paper draws on survey data from a representative sample of 303 mayors in municipalities with populations larger than 10 000 inhabitants. The analysis confirms that Spanish mayors follow to a great extent the patterns found in studies of political elites and particularly those of local executives in other countries in Europe, but with some distinctive singularities.

Keywords: local government, local democracy, mayors, political recruitment, political leaders, Spain.

RESUMEN

La literatura sobre élites políticas en España ha tendido a centrarse en el estudio de los parlamentos y de los gobiernos nacionales y autonómicos, en lugar del nivel de gobierno municipal. Pese a ello, es precisamente en el entorno local donde los políticos adquieren sus habilidades y experiencia política, donde desarrollan sus nociones de democracia y donde en muchas ocasiones inician sus carreras políticas. El estudio de los patrones de reclutamiento en las democracias locales españolas nos permite comprobar si algunos de los hallazgos que ofrecen las investigaciones en la materia se confirman a nivel municipal en España, mejorando así nuestro conocimiento acerca de quiénes gobiernan nuestras ciudades. Este artículo analiza los perfiles sociales de los alcaldes y alcaldesas españoles, sus patrones de profesionalización y sus ambiciones políticas, intentando abordar cuestiones como: ¿Comparten los líderes locales antecedentes comunes? ¿Son amateurs o políticos profesionales? ¿Es el nivel municipal un primer paso en una carrera política identificable de los representantes españoles? Para responder a estas preguntas el trabajo se apoya en información procedente de una encuesta a una muestra representativa de 303 alcaldes de municipios de más de 10 000 habitantes. Los resultados confirman que los alcaldes y alcaldesas españoles comparten los patrones identificados por la literatura sobre élites políticas, particularmente la referida a gobiernos locales en otros países europeos, si bien se identifican algunas especificidades propias.

Palabras clave: gobierno local, democracia local, alcaldes, reclutamiento político, líderes políticos, España.

CONTENTS

- Abstract

- Resumen

- INTRODUCTION

- PATTERNS OF POLITICAL RECRUITMENT AND CAREER DEVELOPMENT

- METHOD

- EMPIRICAL FINDINGS ON THE SOCIAL BASE AND CAREER PATTERNS OF SPANISH MAYORS

- The social base of political recruitment

- The professionalization of mayors

- Mayors’ political ambitions

- CONCLUDING REMARKS

- Notes

- References

- APPENDIX

INTRODUCTION[up]

Cities are the public spaces where we first learn about the functioning of democracy and where we develop as citizens. Following the profound decentralization processes that took place throughout Europe ( Vetter, Angelika and Norbert Kersting. 2003. “Democracy versus efficiency? Comparing local government reforms across Europe”, in Norbert Kersting and Angelika Vetter, Reforming local government in Europe: closing the gap between democracy and efficiency. Opladen : Leske and Budrich.Vetter and Kersting, 2003) including Spain ( Navarro, Carmen and Francisco Velasco. 2016. “‘In wealth and in poverty?’ The changing role of Spanish municipalities in implementing childcare policies”, International Review of Administrative Sciences, 82 (2), 315-334.Navarro and Velasco, 2016) at the end of the last century, city governments have become increasingly relevant in the multilevel governance system and in providing services for the welfare of their residents. This makes them key actors in our political systems and, therefore, an attractive field for investigation. Cities are governed by mayors, visible heads of local democracies.

Important though mayors are, the literature on political elites has only partially analyzed this group of representatives ( Sundström, Aksel. 2013. Women’s Political Representation within 30 European Countries. QoG Working Paper Series, 2013 (18).Sundstrom, 2013). In the case of Spain, the growing body of studies of political recruitment has tended to focus on national and regional parliaments or executives ( Coller, Xavier, Antonio Jaime and Fabiola Mota. 2016. El poder político en España: parlamentarios y ciudadanía. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.Coller et al., 2016; Rodríguez Teruel, Juan. 2011. Los ministros de la España democrática: reclutamiento político y carrera ministerial de Suárez a Zapatero, 1976-2011. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales.Rodríguez Teruel, 2011) rather than on the municipal level of government. These more than eight thousand mayoral offices periodically filled with local representatives have thus remained under-researched. However, recruitment patterns and career development in a specific political system can only fully be understood if the local world is also analyzed.

In this study, the recruitment process refers to the path that leads to the head of the local government, the mayoral office. In municipal electoral contests, lists are closed and blocked and mainly made by parties (or electoral coalitions). After elections, Spanish mayors (alcaldes) are indirectly elected by the councilors in the first council session. More specifically, only councilors that were at the top of the electoral lists could be candidates for the mayoral office. To become a mayor, it is required either the absolute majority of councilors’ votes or, if this majority is not reached in the first vote, the councilor heading the list with most citizens’ votes automatically becomes the mayor. Once in office, Spanish mayors are the central figures of their municipal government. In typologies of local government forms, they belong to the “Strong Mayor” category, for they are able to “control the majority of the city council and are legally and actually in full charge of all the executive functions” ( Mouritzen, Poul E. and Svara James H. 2002. Leadership at the Apex: Politicians and administrators in Western local governments. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. Mouritzen and Svara, 2002: 55).

Exploring who our local elites are matters for a better understanding of paths in the political career and the functioning conditions of this cradle of the Spanish political elite; it also allows us to examine the extent to which political positions are open to everyone irrespective of their social background, or whether a link between descriptive representation (characteristics of those in an elected office) and substantive representation (the type of political action, leadership style and policies they adopt) can be established ( Pitkin, Hanna F. 1967. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.Pitkin, 1967). This article will tackle this topic by looking at the extent to which the main literature’s findings on the selection and career of political elites can also be found in the Spanish local context. They mainly refer to: a) the overrepresentation of a specific profile among representatives —i.e. male, middle-age, middle class— and b) the professionalization of the local political elite. Although this topic has obvious normative implications, this contribution does not aim to address them, but rather to contribute to the growing knowledge base about the Spanish local elite to make normative studies possible.

Thus, it seeks a response to the following questions: who stands for and gets elected mayor? Do municipal leaders share a common background? Are they amateurs or professionals in politics? Does the municipal political level of representation in Spain provide a career path to office in regional or central institutions? Our approach is both descriptive and analytical: Descriptive because it offers information on the main socio-economic traits and on the perceptions about ambitions of current Spanish mayors in large and medium sized municipalities. And analytical in attempting to find different patterns of career development, taking as potential explanatory factors variables such as age, education, sex, party affiliation, party family or size of the municipality.

Our hypotheses are derived from works based on the study of both national and regional

legislatures (i.e. Cotta, Maurizio and Heinrich Best. 2000. “Between Professionalization and Democratization:

A Synoptic View on the Making of the European Representative”, in Maurizio Cotta and

Heinrich Best (eds.), Parliamentary representatives in Europe, 1848-2000: legislative recruitment and careers

in eleven European countries. Oxford. Oxford University Press. Cotta and Best, 2000;

Norris, Pippa and Joni Lovenduski. 1995. Political recruitment: Gender, race and class in the British Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Norris and Lovenduski, 1995; Coller, Xavier, Antonio Jaime and Fabiola Mota. 2016. El poder político en España: parlamentarios y ciudadanía. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.Coller et al., 2016) and local assemblies and executives ( Steyvers, Kristof and Herwig Reynaert. 2006.”‘From the Few are Chosen the Few...’.

On the Social Background of European Mayors”, in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick

Magnier, (eds.), The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Steyvers and Reynaert, 2006; Kjær, Ulrik. 2006. “The mayor’s political career”, in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and

Annick Magnier (eds.), The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Kjaer, 2006; Guérin, Élodie and Eric Kerrouche. 2008. “From amateurs to professionals: The changing

face of local elected representatives in Europe”, Local Government Studies, 34 (2), 179-201.Guerin and Kerrouche, 2008). To test them, we use data from the so-called POLLEADER II Project (Political Leaders

in European Cities. Second Round)[1]. This is a comparative data set based on a survey conducted across 29 European countries

between 2015 and 2016 which aims to analyze the role played by mayors and the transformation

of political representation at the local level This research has been financed by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness:

«Una nueva arquitectura local: eficiencia, dimensión y democracia» (CSO213-48641-C2-1-R).

This work is structured in four sections. After this brief introduction, the literature’s main arguments and findings on the social background of political recruitment and professionalization of local executives are presented in the next section. The third and fourth sections describe the data and methods used in this article, presents the analysis of the database and discusses its findings in the light of the previous studies in the topic. The paper concludes by pointing to some general conclusions and to elements suggested by the study as avenues for further research.

PATTERNS OF POLITICAL RECRUITMENT AND CAREER DEVELOPMENT[up]

The process by which individuals are selected for inclusion among political elites is called political recruitment. The question arises: do all potential candidates for inclusion have the same chances of being selected for the electoral list or position? The literature on political elites reports that recruitment operates in such a way that having a specific social profile increases the chances for individuals to enter and remain in political office (see, for example, Eulau, Heinz and Kenneth Prewitt. 1973. Labyrinths of Democracy: Adaptations, Linkages, Representation, and Policies in Urban Politics. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.Eulau and Prewitt, 1973; Norris, Pippa and Joni Lovenduski. 1995. Political recruitment: Gender, race and class in the British Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Norris and Lovenduski, 1995; Cotta, Maurizio and Heinrich Best. 2000. “Between Professionalization and Democratization: A Synoptic View on the Making of the European Representative”, in Maurizio Cotta and Heinrich Best (eds.), Parliamentary representatives in Europe, 1848-2000: legislative recruitment and careers in eleven European countries. Oxford. Oxford University Press. Cotta and Best, 2000).

The “supply and demand model” ( Norris, Pippa and Joni Lovenduski. 1995. Political recruitment: Gender, race and class in the British Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Norris and Lovenduski, 1995) is a well-known approach for explaining political recruitment. It presents the outcome of selection as the interaction between the supply of candidates wishing to stand for political office and the demands of gatekeepers or selectorates (parties) who select the candidates. Supply factors are inherent in the aspirants’ individual characteristics : they are the traits that increase their chances to run for, and remain in, office. Among the elements that can shape the supply of candidates are their personal resources (education, time, experience), motivation, ambition or interest in politics ( Krook, Mona L. and Leslie Schwindt-Bayer. 2013. “Electoral Institutions”, in Georgina Waylen, Karen Celis, Johanna Kantola and Laurel Weldon, (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Krook and Schwindt-Bayer, 2013). Not all individuals aspiring to political office have the same opportunities. For instance, the personal resource “time to devote to politics” might be scarcer for younger people or for women compared to men or middle-age candidates due to their personal circumstances. Demand factors refer to the parties selectorates’ preferences. They point to parties and how they engage in the candidates recruiting process with specific perceptions of their qualifications and skills. These perceptions can be influenced by, among other things, shortcuts that lead to identifying only individuals from one’s own social networks or with some particular profile.

In looking at the actual result of these interactions between supply and demand, most studies coincide in pointing at gender, age, educational achievement and occupation as important factors for attaining places on the electoral lists. It is what some authors refer to as the “3 M mantra” of elite research ( Steyvers, Kristof and Herwig Reynaert. 2006.”‘From the Few are Chosen the Few...’. On the Social Background of European Mayors”, in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier, (eds.), The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Steyvers and Reynaert, 2006): representatives tend to be male, middle-aged and middle-class. At every level of government or the type of legislature, there is an over-representation of these population groups among the political elite. The afore-mentioned factors will now be taken in turn.

Gender [up]

The under-representation of women within the political class is one of the best reported and most researched aspects of political life ( Kittilson, Miki C. 2013. “Party Politics”, in Georgina Waylen, Karen Celis, Johana Kantola and Laurel Weldon (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Kittilson, 2013). However, the past two decades have witnessed enormous transformations in the presence of this group in the political sphere. Changes in society, as well as parties’ internal rules and national gender quotas have proved to be effective tools for increasing women’s representation in elected bodies of government ( Franceschet, Susan, Mona L. Krook and Jennifer M. Piscopo. 2013. The impact of Gender Quotas. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Franceschet et al., 2013).

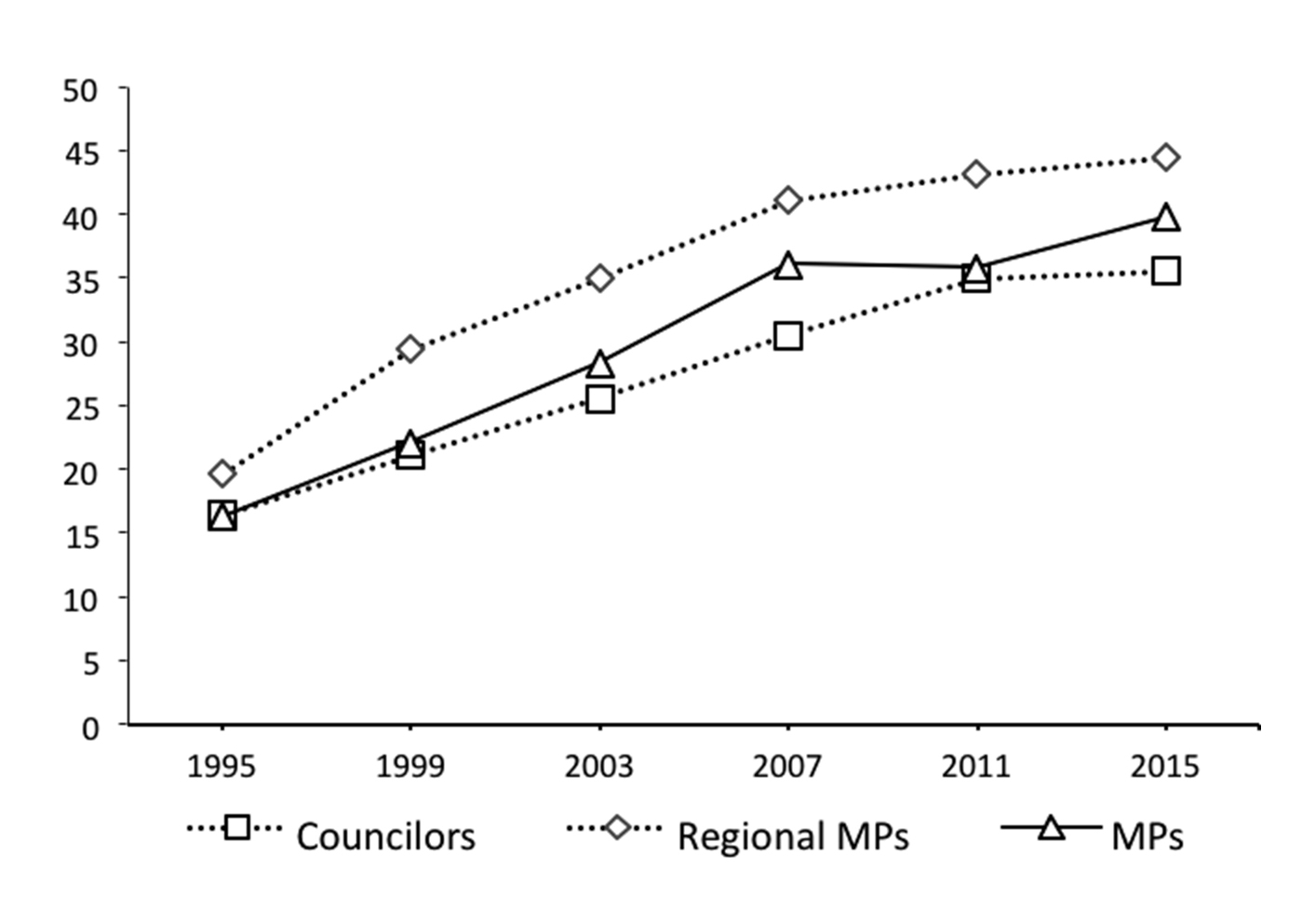

Spain constitutes a positive example of the gradual inclusion of women in the political sphere. Over the past two decades, their proportion in legislatures has increased from less than 20 % across the board in the mid-90s to current figures of 40 % in the national lower chamber, 45 % in regional parliaments and 36 % in local assemblies (see figure 1). It is remarkable how rapid and homogeneous the inclusion of women —particularly in regional parliaments— has been ( Verge, Tània, Maria A. Novo, Isabel, Diz and Marta I. Lois. 2016. “Género y Parlamento: impacto de la presencia política de las mujeres”, in Xavier Coller, Antonio Jaime and Fabiola Mota, (eds.), El poder político en España: parlamentarios y ciudadanía Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.Verge et al., 2016). By contrast and interestingly, rates are lower at the local level. This is a common pattern not only in Spain but throughout Europe in general ( Sundström, Aksel. 2013. Women’s Political Representation within 30 European Countries. QoG Working Paper Series, 2013 (18).Sundstrom, 2013), despite the intuitive perception that women should have greater access to local elected office where supply barriers such as time devoted to political activity or geographical distance are lower. However, few studies have addressed the topic of women in local politics ( Navarro, Carmen and Lluis Medir. 2016. “Patterns of Gender Representation in Councils at the Second Tier of Local Government. Assessing the Gender Gap in an Unexplored Institutional Setting”, in Xavier Bertrana, Björn Egner and Hubert Heinelt (eds.), Policy Making at the Second Tier of Local Government. What Is Happening in Provinces, Counties, Départements and Landkreise in the On-going Re-scaling of Statehood. Abingdon, Oxon : Routledge.Navarro and Medir, 2016).

Studies report that once the threshold of the “critical mass” of a 30 % of women in legislatures has been achieved, it rarely recedes ( Santana, Andrés, Xavier Coller and Susana Aguilar. 2015. “Women MPs in Spanish Regional Parliaments: Critical Mass, Parliamentary Experience and Political Influence”, Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 149: 111-130.Santana et al., 2015). However, the same progress has not been made in power positions and, consequently, more attention is focused now on the thicker “glass ceiling” women face in gaining access to executive positions ( Paxton, Pamela and Melanie M. Hughes. 2013. Women, Politics, and Power: A Global Perspective. Los Angeles: Sage.Paxton and Hughes, 2013; Santana, Andrés, Xavier Coller and Susana Aguilar. 2015. “Women MPs in Spanish Regional Parliaments: Critical Mass, Parliamentary Experience and Political Influence”, Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 149: 111-130.Santana et al., 2015): their chances to rise to the top of the political power hierarchy decrease when compared to legislatures. Mayoral offices are not an exception. Previous studies ( Sundström, Aksel. 2013. Women’s Political Representation within 30 European Countries. QoG Working Paper Series, 2013 (18).Sundstrom, 2013; Navarro, Carmen and Lluis Medir. 2016. “Patterns of Gender Representation in Councils at the Second Tier of Local Government. Assessing the Gender Gap in an Unexplored Institutional Setting”, in Xavier Bertrana, Björn Egner and Hubert Heinelt (eds.), Policy Making at the Second Tier of Local Government. What Is Happening in Provinces, Counties, Départements and Landkreise in the On-going Re-scaling of Statehood. Abingdon, Oxon : Routledge.Navarro and Medir, 2016) have found that women are underrepresented among mayors, especially in systems such as Spain’s, where the “strong mayor” type of local government makes the mayoral office the center of political power ( Steyvers, Kristof and Herwig Reynaert. 2006.”‘From the Few are Chosen the Few...’. On the Social Background of European Mayors”, in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier, (eds.), The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Steyvers and Reynaert, 2006). In sum, it is more difficult for women to gain access to local assemblies, and it is particularly difficult for them to become part of the core power apparatus that make key decisions.

Researchers have identified three categories of factors that explain varying levels of women’s participation in political office: institutional ( Duverger, Maurice. 1955. The Political Role of Women. Paris: Unesco. Duverger, 1955; Kittilson, Miki C. 2006. Challenging Parties, Changing Parliaments: Women and Elected Office in Contemporary Western Europe. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press. Kittilson, 2006; Wängnerud, Lena . 2009. “Women in parliaments: Descriptive and substantive representation”, Annual Review of Political Science, 12: 51-69. Wangnerud, 2009; Oñate, Pablo. (2014). “The effectiveness of quotas: vertical and horizontal discrimination in Spain”, Representation, 50 (3): 351-364.Oñate, 2014) such as electoral rules, how parties organize candidate selection or gender quotas; socioeconomic ( Rosenbluth Frances, Rob Salmond and Michael F. Thies. 2006. “Welfare works: Explaining female legislative representation”, Politics and Gender 2 (2): 165-192. Rosembluth et al., 2006; Iversen, Torben and Frances Rosenbluth. 2008. “Work and power: The connection between female labor force participation and political representation”, Annual Review of Political Science, 11: 479-495.Iversen and Rosembluth, 2008) such as the proportion of women in the workforce and the strength of the welfare state; and cultural ( Dahlerup, Drude and Monique Leyenaar. 2013. Breaking male dominance in old democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Dalherup and Leyennard, 2013) such as modernization trends, beliefs about equality, and the social acceptance of women for representational and leadership roles. The have also found that, other things being equal, leftist parties have traditionally been more likely to nominate women to safe places on their lists, although party ideology seems not to matter as much nowadays as it did in the past ( Kittilson, Miki C. 2013. “Party Politics”, in Georgina Waylen, Karen Celis, Johana Kantola and Laurel Weldon (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Kittilson, 2013). In addition, in big cities the percentage of women in the mayoral office tends to increase ( Steyvers, Kristof and Herwig Reynaert. 2006.”‘From the Few are Chosen the Few...’. On the Social Background of European Mayors”, in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier, (eds.), The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Steyvers and Reynaert, 2006).

All this leads us to expect that, for our sample, women would be unequally represented in mayoral offices, with lower shares than those found in legislatures, considering that it is the top position in the ladder to power in local government. We also expect to find differences by municipality size and party family, with more highly populated cities (because they are more diverse in representation) and leftist parties identified as factors related to higher female presence in mayoral offices.

Age [up]

The age distribution of political elites is a key aspect of their social background and can have normative implications, as well. The openness of the political arena and the system’s capacity to benefit from groups of all ages, and from newcomers, can be assessed through this variable.

Local political systems tend to score low in the inclusion of young people among their political elites ( Reynaert, Herwig. 2012. “The Social Base of Political Recruitment. A Comparative Study of Local Councillors in Europe”, Lex Localis. Journal of Local Self-Government, 10 (1): 19-36. Reynaert, 2012). From a normative perspective, this trend has advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, institutions and the decision-making process can benefit from new and different ideas if young elites occupy office; on the other hand, their inexperience in office can lead them to be less pragmatic and more inclined to avoid pacts in order to overcome policy paralysis ( Coller, Xavier, Helder Ferreira do Vale and Chris Meissner. 2008. Political elites in federalized countries: The case of Spain (1980-2005). Barcelona: Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials.Coller et al., 2008).

The overrepresentation of middle-aged people in political positions might be explained by the so-called “life cycle” hypothesis ( Steyvers, Kristof and Herwig Reynaert. 2006.”‘From the Few are Chosen the Few...’. On the Social Background of European Mayors”, in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier, (eds.), The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Steyvers, 2006), according to which candidates belonging to this group are in a better position to attain political access than their younger counterparts. Middle-aged aspirants enter electoral competitions having a) some already acquired professional and/or political experience that makes them more competitive for representative positions; b) more time to dedicate to politics after having passed through the central and most time-consuming period of life (e.g. raising their children, professional training); and c) already constructed consistent social, professional and party networks, which situate them in the best position to access power. In other words, the costs of getting involved in political activity are reduced in this period of life.An additional trait completes the understanding of this logic. The higher the level of power of the representative or executive position —or, in other words, the more exclusive the office— the longer it takes to get there. Therefore, one might expect that national parliamentarians would be older than their regional colleagues, and that ministers would be older than legislative representatives, etc.

In local government and specifically for the position of mayor, previous studies (for municipalities with populations above 10 000) have identified that middle-aged office holders are overrepresented ( Steyvers, Kristof and Herwig Reynaert. 2006.”‘From the Few are Chosen the Few...’. On the Social Background of European Mayors”, in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier, (eds.), The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Steyvers and Reynaert, 2006; Verhelst, Tom, Herwig Reynaert and Kristof Steyvers. 2013. “Political recruitment and career development of local councillors in Europe”, in Björn Egner, David Sweeting and Pieter-Jan Klok (eds.), Local Councillors in Europe. Wiesbaden: Springer. Verhelst et al., 2013). But, interestingly, the analysis also revealed that Spanish mayors were the youngest in the European group, 47.7 years old on average, compared to 56.4 in France, 52.4 in Germany and 57.1 in England (Ibid). Almost 40 % of Spanish mayors were between the ages of 40 and 49 ( Steyvers, Kristof and Herwig Reynaert. 2006.”‘From the Few are Chosen the Few...’. On the Social Background of European Mayors”, in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier, (eds.), The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Steyvers and Reynaert, 2006). The youth of Spanish representatives is not a feature limited to mayoral positions. Regional parliaments are also political arenas where high rates of relatively young politicians can be found. They are 48.2 years old on average (42 % of them are older than 50, 45 % are between 50 and 36 years old, and 13 % of them are under 36) ( Bermúdez, Sandra and Inmaculada Serrano. 2016. “¿Cómo son los parlamentarios?”, in Xavier Coller, Antonio Jaime and Fabiola Mota (eds.), El poder político en España: parlamentarios y ciudadanía. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.Bermúdez and Serrano, 2016). And this distinctive pattern of the Spanish political elite extends to the highest office of the executive as well. Most prime ministers in the last four decades were in their late forties when they first took office. Other studies have shown that female parliamentarians are younger than men, which seems to be connected to lower rates of seniority in political party’s affiliation ( Verge, Tània, Maria A. Novo, Isabel, Diz and Marta I. Lois. 2016. “Género y Parlamento: impacto de la presencia política de las mujeres”, in Xavier Coller, Antonio Jaime and Fabiola Mota, (eds.), El poder político en España: parlamentarios y ciudadanía Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.Verge et al., 2016).

Taking all this into account, we expect that mayors in our sample would tend to be middle- aged, although there will be variation by gender and by size of municipality.

Education and profession [up]

The literature on political elites describes a pattern of political leaders having high levels of education and belonging to specific highly qualified professions ( Cotta, Maurizio and Heinrich Best. 2000. “Between Professionalization and Democratization: A Synoptic View on the Making of the European Representative”, in Maurizio Cotta and Heinrich Best (eds.), Parliamentary representatives in Europe, 1848-2000: legislative recruitment and careers in eleven European countries. Oxford. Oxford University Press. Cotta and Best, 2000; Bermúdez, Sandra and Inmaculada Serrano. 2016. “¿Cómo son los parlamentarios?”, in Xavier Coller, Antonio Jaime and Fabiola Mota (eds.), El poder político en España: parlamentarios y ciudadanía. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.Bermúdez and Serrano, 2016). University training is nowadays widely prevalent throughout political elites. This is so partly because governing has become a very demanding activity that requires a good level of mastery over complex issues, and partly because the proportion of people with higher educational credentials has dramatically increased over recent decades. Local mayoral offices would not be an exception in this respect.

In the Spanish context, the outstanding growth of university educated citizens over the last thirty years has also extended to the social background of political elites. In 2010, 81 % of national MPs and 77 % of regional ones had university degrees ( Bermúdez, Sandra and Inmaculada Serrano. 2016. “¿Cómo son los parlamentarios?”, in Xavier Coller, Antonio Jaime and Fabiola Mota (eds.), El poder político en España: parlamentarios y ciudadanía. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.Bermúdez and Serrano, 2016). Regarding local government, the changes have been outstanding. In the early 1980s Capo and associates reported —in their study about local elites in Catalonia— that only 11 % of all mayors had a university degree ( Capo, Jordi, Montserrat Baras, Joan Botella and Gabriel Colomé. 1988. “La formación de una élite política local”. Revista de Estudios Políticos, (59): 199-224.Capo et al., 1988). Thirty years later, this proportion had reached 70 % in municipalities over 10 000 inhabitants ( Steyvers, Kristof and Herwig Reynaert. 2006.”‘From the Few are Chosen the Few...’. On the Social Background of European Mayors”, in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier, (eds.), The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Steyvers and Reynaert, 2006).

As for backgrounds, there is a gap between the society as a whole and the political elite. Norris and Lovenduski ( Norris, Pippa and Joni Lovenduski. 1995. Political recruitment: Gender, race and class in the British Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.1995) identified an overrepresentation of what they called “talking and brokerage” professions. This category is comprised by lawyers, teachers, public sector professionals and managers, among others. The explanation for their overrepresentation in politics is that candidates coming from these professional activities would have many advantages of pursuing political careers, compared to other sectors of the population. In the first place, these professions involve the mastering of some skills of great importance for political activity, such as communication, bargaining and debating skills. The rationale behind this is that by performing these occupations one is better equipped to convince, explain and generate trust. Moreover, these professional careers couldbe more easily interrupted in order to pursue political office and without incurring too high costs. This is the case both because most of them are civil servants —for example teachers— who would keep their job positions guaranteed after coming back from political service, or because their colleagues can easily take over their responsibilities in the organizations where they work —as it is the case of lawyers ( Coller, Xavier, Helder Ferreira do Vale and Chris Meissner. 2008. Political elites in federalized countries: The case of Spain (1980-2005). Barcelona: Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials.Coller et al., 2008).

In studies of Spanish political elites, the largest group comes from the education sector ( Coller, Xavier, Helder Ferreira do Vale and Chris Meissner. 2008. Political elites in federalized countries: The case of Spain (1980-2005). Barcelona: Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials.Coller et al., 2008). In 2010, they represented 23 % of all regional and national MPs, followed by lawyers (18 %) and professionals from the humanities and social sciences combined (22 %). Some differences by party affiliation were also observed. The conservative party Partido Popular was found to have higher rates of legal professionals on their rolls, while educators were more highly represented in leftist parties ( Bermúdez, Sandra and Inmaculada Serrano. 2016. “¿Cómo son los parlamentarios?”, in Xavier Coller, Antonio Jaime and Fabiola Mota (eds.), El poder político en España: parlamentarios y ciudadanía. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.Bermúdez and Serrano, 2016).

Other works specifically focusing on local political leaders in Europe have arrived at similar conclusions. In 2006, the largest share of all mayors in Europe —and among them 44 % of Spanish ones— were connected to brokerage professions ( Steyvers, Kristof and Herwig Reynaert. 2006.”‘From the Few are Chosen the Few...’. On the Social Background of European Mayors”, in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier, (eds.), The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Steyvers, 2006). For councilors, these talking and brokerage professions prior to entering the council are also the most numerous: 57 % in 2010, with civil servants and teachers as the largest groups ( Reynaert, Herwig. 2012. “The Social Base of Political Recruitment. A Comparative Study of Local Councillors in Europe”, Lex Localis. Journal of Local Self-Government, 10 (1): 19-36. Reynaert, 2012).

We expect our sample to be dominated by mayors with university degrees (considering the city threshold of 10 000 inhabitants), with the majority from talking and brokerage professions, with some differences in size and in party affiliation.

Mayors’ career development: amateurs or professionals? [up]

The local political elite is characterized not only by a specific social background but also by increasing professionalization ( Guérin, Élodie and Eric Kerrouche. 2008. “From amateurs to professionals: The changing face of local elected representatives in Europe”, Local Government Studies, 34 (2), 179-201.Guérin and Kerrouche, 2008), particularly in the case of executives. This means that a career in politics has tended to replace a mayor’s initial occupation. Some changes in the governmental context have contributed to this outcome.

The contexts of local democracies are not the same nowadays to those we knew of a few decades ago. Some specific external trends (urbanization, globalization, Europeanisation) and internal ones (rise of citizens’ demands) have introduced enormous pressure on the exercise of government ( Denters, Bas and Lawrence E. Rose. 2005. Comparing Local Governance. Trends and Developments. Basingstoke, UK : Palgrave Macmillan.Denters and Rose, 2005). Local institutions are being forced more than ever to improve their problem-solving capacity and effective leadership, in order to meet current demands. Consequently, political leadership nowadays requires more expertise, an intense workload and technical understanding of the complex issues local governments are responsible for ( Guérin, Élodie and Eric Kerrouche. 2008. “From amateurs to professionals: The changing face of local elected representatives in Europe”, Local Government Studies, 34 (2), 179-201.Guérin and Kerrouche, 2008).

All these circumstances favor professional political careers that are to some extent in tension with the traditional image of local politics as the last arena in which “amateurs” exercise power on a voluntary basis, devoting their time to the public cause for a limited period of time ( Aars, Jacob, Audun Offerdal and Dan Rysavy. 2012. “The Careers of European Local Councillors: A Cross-National Comparison1”, Lex localis, 10 (1): 63.Aars et al., 2012).

Previously, the ideal of lay representatives —as elected citizens empowered to act on behalf of their neighbors— was the benchmark: in this way, local democracies embodied the base of democratic government ( Mouritzen, Poul E. and Svara James H. 2002. Leadership at the Apex: Politicians and administrators in Western local governments. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. Mouritzen and Svara, 2002). The Spanish town halls of the late 1980s, headed to a large extent by amateurs, illustrate this reality ( Capo, Jordi, Montserrat Baras, Joan Botella and Gabriel Colomé. 1988. “La formación de una élite política local”. Revista de Estudios Políticos, (59): 199-224.Capo et al., 1988). Today, this principle has receded and, instead, elected officials with more professional profiles, who conceive politics as a profession with specific patterns of conduct and routines, have gained ascendance.

All this has not occurred without a debate and some controversy. However, whatever normative position one takes on the professionalization of the political elite, for the purposes of our study its salience lies in the effect it has on political recruitment. Not only have the criteria —by which candidates are recruited— transformed, reinforcing particular professional backgrounds (with no professional experience beyond politics or coming from communication and brokerage professions); but there has also been a change in the type of actors responsible for selecting them. As the exercise of politics has become more demanding, parties have occupied the local arena and are increasingly responsible for leading these processes ( Reynaert, Herwig. 2012. “The Social Base of Political Recruitment. A Comparative Study of Local Councillors in Europe”, Lex Localis. Journal of Local Self-Government, 10 (1): 19-36. Reynaert, 2012). Candidates, for their part, increasingly tend to have party affiliations.

On the other hand, and due to this stronger connection to parties, professionalization allows for more scope in candidates’ trajectories. The party system offers an access channel from local to regional and central levels. This is even more accentuated in countries like Spain, where the electoral system of closed and blocked list gives parties greater control over the internal composition of the lists. After having been trained in the “nursery” of politics, acquiring skills and political experience, municipal representatives would be more prepared to ascend to regional and/or national arenas. In the Spanish case, there are strong links between regional and national parliaments on the one hand, and local arenas on the other. In 2010, two thirds of regional and national MPs had previous experience in municipal activity either as councilors or as mayors ( Liñeira, Robert and Jordi Muñoz. 2016. “Profesionalización y trayectorias parlamentarias”, in Xavier Coller, Antonio Jaime and Fabiola Mota (eds.), El poder político en España: parlamentarios y ciudadanía Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.Liñeira and Muñoz, 2016). If the political career refers to the patterns of mobility once in office, local councils are, for many parliamentarians, the starting point.

The trend towards professionalization can be empirically analyzed based on some indicators organized around two criteria: focus and scope. Focus relates to the exclusivity of the job in terms of time and dedication, while scope refers to its duration and the prospects for the future ( Guérin, Élodie and Eric Kerrouche. 2008. “From amateurs to professionals: The changing face of local elected representatives in Europe”, Local Government Studies, 34 (2), 179-201.Guérin and Kerrouche, 2008). Prospects are closely connected to political ambitions. Politicians could have discrete, static or progressive ambitions ( Schlesinger, Joseph A. 1966. Ambition and Politics: Political Careers in the United States. Chicago: Rand McNally.Schlesinger, 1966). Discrete ambitions apply to cases when politicians are likely to step down from public service; static ambitions refer to those wanting to stay in the same office; while progressive ambitions entail the willingness to advance upward in the political career to upper legislatures.

For the amateur type of mayor, elected office would be an activity combined with another profession or, if it involves a full-time job, they would have less time to dedicate in terms of weekly hours. They would be less likely to be members of political parties and more likely to be elected from local lists, or act as independent candidates. In terms of political ambitions, amateurs are characterized by their limited ambitions: once their terms in office end, they frequently leave the work and do not run again in subsequent elections.

Professionals would tend to be full-time mayors with long-established political experience either in the mayoral office or in the council. They are more likely to be members of local branches of regional or national political parties, and their previous professional experience is frequently connected to the party organization. Where the political system allows it, they would tend to hold other mandates simultaneously in provincial, regional or national assemblies or institutions. In terms of political ambitions, their intentions, once the current electoral period is over, would be to either run again at the next election for the same office (static ambitions) or to seek upward mobility to a higher political office (progressive ambitions). Given the described emergence of professionalization patterns of local political elites in executive positions, we expect, for our sample, to find a predominance of the professional profile.

Further, particularly for political ambitions, we expect to find variation among mayors in the preferences they express on this topic (discrete, static or progressive ambition), based on specific factors such as gender, age, education, profession, dedication to mayoral office and type of party. First, the literature has reported lower levels of political ambition among female political candidates compared to male ones ( Lawless, Jennifer and Richard L. Fox. 2010. It Still takes a Candidate: Why Women Don’t Run for Office. New York: Cambridge University Press.Lawless and Fox, 2010), so we expect that this will be reflected in the mayors’ career patterns. Second, the younger the person in the mayoral office the more actual prospects he or she will have for a progressive trajectory in politics. Consequently, younger mayors will tend to express more progressive ambitions. Third, education and previous profession may influence the motivation to pursue or not a political career. Less educated mayors will have fewer professional offers in the market once their terms in office are concluded and have more incentives to run again in the next electoral contest. Regarding professional background and unlike those who entered politics from the civil service, mayors who had a previous occupation in the private sector —with the exception of lawyers— are less dispensable. They do not have their return to work guaranteed if they extend their public service indefinitely, and, therefore, they would tend to express more limited ambitions. Finally, membership and seniority in a party would indicate mayors with a more politically professionalized profile, which will naturally be associated with a desire to remain in politics.

METHOD[up]

In order to study Spanish mayors’ social profile and professionalization, this article

relies on descriptive statistics and appropriate bivariate analyses. As for the study

of Spanish mayors’ political ambitions , multivariate logistic regression will be

employed. In this case, the main dependent variable consists in the mayors’political

ambitions after their current mandate The response options considered were: continue as mayor, stay in the local council

but not as mayor, move to regional politics, move to national politics or return to

a previous profession out of politics.

The independent variables considered in the analyses are: gender, age, education level,

educational area, number of inhabitants of the municipality in 2014 (logged), party

membership, type of mayor’s party (local, regional or state-wide), party family For the party family we followed the classification by Andersson et al. ( Andersson, Staffan, Torbjörn Bergman and Ersson Svante. 2014. “The European Representative

Democracy Data Archive, Release 3”. Main sponsor: Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (In2007-0149:1-E).

Following Norris and Lovenduski ( Norris, Pippa and Joni Lovenduski. 1995. Political recruitment: Gender, race and class in the British Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Depending on the metrics of the variables involved, the bivariate analyses consisted in crosstabs (with Chi2 tests), mean comparisons (with t or F tests) and Pearson correlation’s (with t tests). In the case of the multivariate analyses of the political ambitions, given the qualitative nature of the dependent variable we employed logistic regression.

EMPIRICAL FINDINGS ON THE SOCIAL BASE AND CAREER PATTERNS OF SPANISH MAYORS [up]

The social base of political recruitment [up]

Building on the previous theoretical overview, we now turn to our data to see whether Spanish mayors in municipalities with populations above 10 000 inhabitants, follow the patterns identified in the literature on political recruitment of political elites and, particularly, local elites.

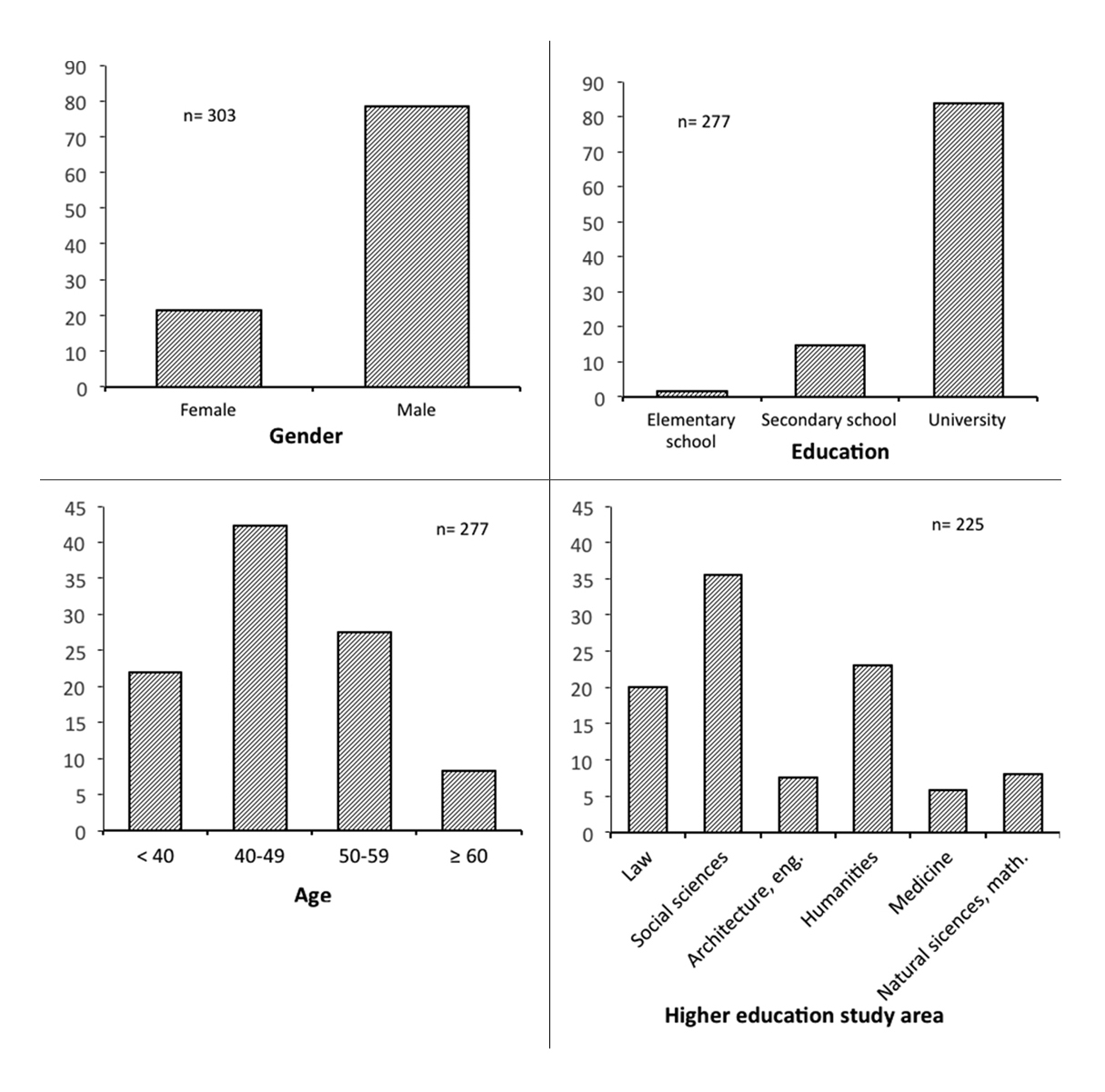

Regarding the socio-demographic profile of the Spanish mayors, our results tend to confirm previous findings on the topic with some singularities. In figure 2, we report mayors’ gender, age, level of education and area of university studies. In a nutshell, a clear majority are men (79 %), in their middle age (46 years old on average) and with a university degree (84 %) obtained mainly in the areas of social sciences (35 %) and humanities (23 %).

The gradual increase of women in Spanish legislatures experienced over the last two

decades is also reflected in local institutions. This change was first promoted by

some parties (particularly the Socialist Party) that applied internal quotas ( Verge, Tània and Aurélia Troupel. 2011. “Unequals among equals: Party strategic discrimination

and quota laws”, French Politics, 9 (3): 260-281.Verge and Troupel, 2011) for their candidates and later boosted by the Act for Effective Equality passed by the socialist government in 2007 The Act for Effective Equality (Ley Orgánica 3/2007, de 22 de marzo para la igualdad

efectiva de mujeres y hombres) states that political parties should construct electoral

lists in which the presence of candidates of the same sex cannot be below 40 percent

or above 60 % within each section of five candidates.

Figure 2.

The sociodemographic profile of Spanish mayors. Bar graphs represent percentages

Source: POLLEADER, 2nd. round.

Age is a feature in which Spanish mayors present singularities. Although our sample confirms the general pattern of political elites being middle-aged, they are nonetheless at the younger end of this particular period of life. As figure 2 illustrates, the mode is in the interval between 40 and 49 years. As an average, they are in their mid-forties (mean 46.3; std: 9), six years younger than their European counterparts and the youngest in the European scene (mean 52.07; std. 9.15) ( Steyvers, Kristof and Lluís Medir. 2018. “From the Few Are Still Chosen the Few? Continuity and Change in the Social Background of European Mayors”, in Political Leaders and Changing Local Democracy: the European mayor. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.Steyvers and Medir, 2018). Therefore, the data are in line with one of the traits identified in other studies about Spanish political elites: their youth. Compared to the situation one decade ago when the previous survey (POLLEADER I 2003-2004) was conducted, figures have not experienced major changes, neither for the total of European mayors nor for the Spanish ones ( Steyvers, Kristof and Herwig Reynaert. 2006.”‘From the Few are Chosen the Few...’. On the Social Background of European Mayors”, in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier, (eds.), The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Steyvers and Reynaerts, 2006). No differences in age were found by gender either. Although female mayors are slightly younger than males (45.4 and 46.6 respectively), the difference is not statistically significant.

Regarding education, our data ratify one of the main expectations: the predominance of individuals with a university degree (figure 2). Mayors have mainly undertaken undergraduate degrees in the social sciences (36 %) followed by humanities (23 %). Lawyers are only the third group (20 %), differing in this case from the standard law profile found in regional and national legislators ( Coller, Xavier, Helder Ferreira do Vale and Chris Meissner. 2008. Political elites in federalized countries: The case of Spain (1980-2005). Barcelona: Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials.Coller et al., 2008; Bermúdez, Sandra and Inmaculada Serrano. 2016. “¿Cómo son los parlamentarios?”, in Xavier Coller, Antonio Jaime and Fabiola Mota (eds.), El poder político en España: parlamentarios y ciudadanía. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.Bermúdez and Serrano, 2016).

In addition, and in line with the findings showed by other studies about local elites ( Steyvers, Kristof and Herwig Reynaert. 2006.”‘From the Few are Chosen the Few...’. On the Social Background of European Mayors”, in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier, (eds.), The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Steyvers and Reynaert, 2006; Navarro, Carmen and Lluis Medir. 2016. “Patterns of Gender Representation in Councils at the Second Tier of Local Government. Assessing the Gender Gap in an Unexplored Institutional Setting”, in Xavier Bertrana, Björn Egner and Hubert Heinelt (eds.), Policy Making at the Second Tier of Local Government. What Is Happening in Provinces, Counties, Départements and Landkreise in the On-going Re-scaling of Statehood. Abingdon, Oxon : Routledge.Navarro and Medir, 2016), women are significantly better educated than men. 93 % of female mayors have a university degree compared to 81 in the case of their male counterparts. This indicates that education continues to be a vital resource for women ( Paxton, Pamela and Melanie M. Hughes. 2013. Women, Politics, and Power: A Global Perspective. Los Angeles: Sage.Paxton and Hughes, 2013) to try to overcome the structural disadvantages they face to make it to the top of the electoral list.

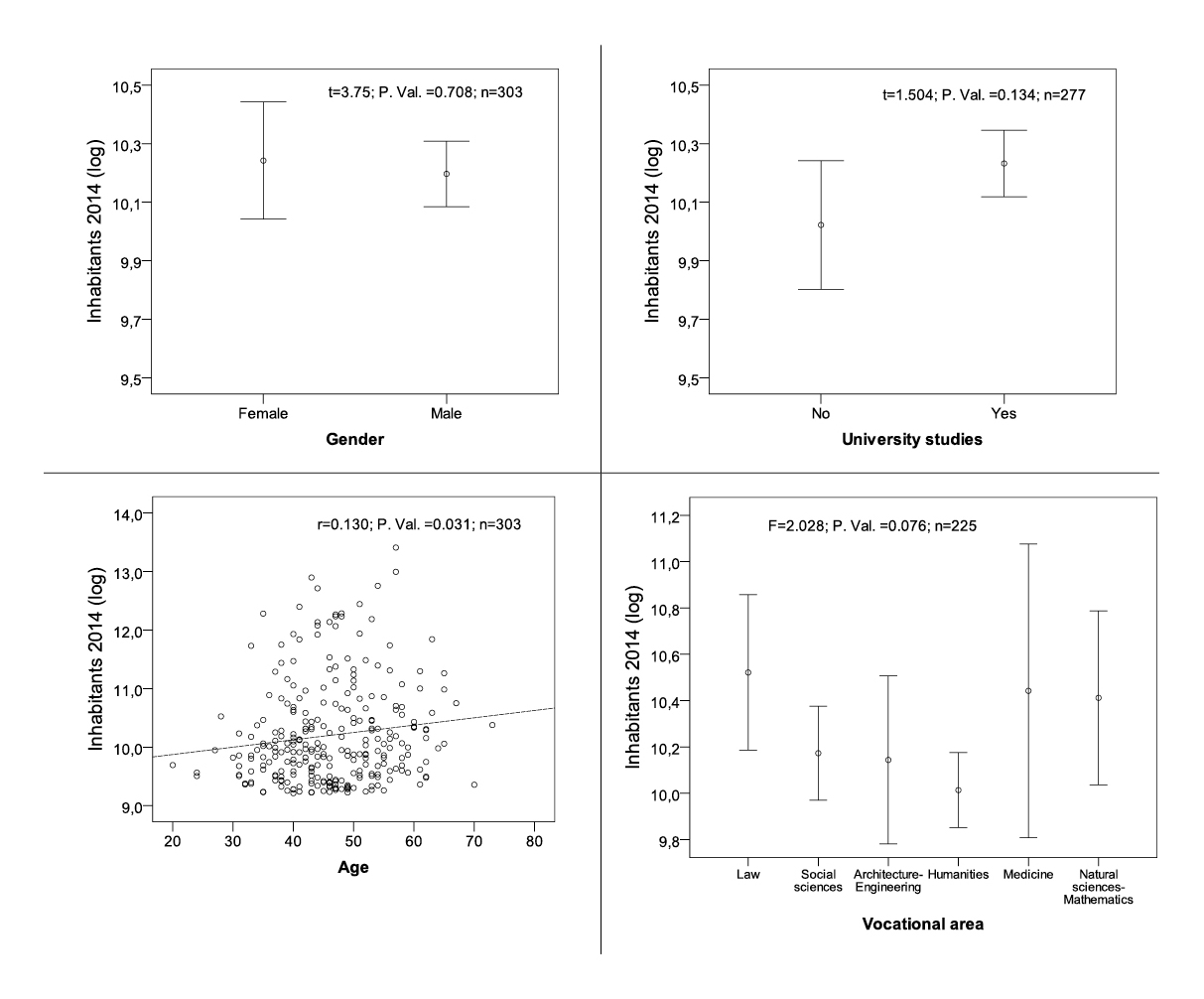

Regarding the expectation of differences in mayors’ social profile by population size, figure 3 presents the results. First, contrary to other studies that pointed to big cities being more diverse and, therefore, more open spaces for women to compete, our data do not confirm this direction. In this respect, the fact that the biggest cities in the country are nowadays governed by women (Manuela Carmena in Madrid and Ada Colau in Barcelona) can not be taken as a pattern. But, according to our data, big cities are not more hostile environments either. The number of inhabitants is unrelated to the likelihood of finding more individuals of a specific gender in the mayoral office. Second, the same disconnection applies for education. Although better trained mayors tend to lead larger communities, differences are not statistically significant.

The component of the social background in which variation by size appears is age.

The larger the municipality, the older the mayor tends to be (figure 3). This probably has to do with the fact that mayors in big cities tend to be very

visible figures and relevant actors in the party structure and in the multilevel political

arena. As a consequence, recruitment processes in these spaces will be more exclusive,

requiring longer trajectories in politics and within the party to opt for the most

important seat in the city hall. These differences indicate that municipalities surveyed

in this study are of a different nature regarding size. Out of around Spanish 750

municipalities with more than 10 000 inhabitants, the highest proportion concentrates

in the group of lower populations For Spain: below 10 000 inhabitants: 7359 municipalities; 10 000 to 20 000: 355; 20 000

to 50 000: 257; 50 000 to 100 000: 83; +100 000: 63. INE 2015.

Figure 3.

Habitat size (logged), by gender, education, age and vocational area of the mayors. Whiskers represent 95 % confidence intervals for the means

Source: POLLEADER, 2nd. Round.

Differences by size are also noticeable in the vocational area of mayors’ university studies (figure 3). Backgrounds in law, medicine, natural science and mathematics are more likely to be found in larger cities, while a profile in humanities (geography, philosophy and the like) is the standard for smaller towns. Particularly in the case of law —bigger cities— versus humanities —smaller towns— the differences are at the edge of statistical significance.

Figure 4.

Education, gender and area of studies of the mayors, by party families (Andersson et al. 2014). Bar graph represent percentage points within party families

Source: POLLEADER, 2nd. round.

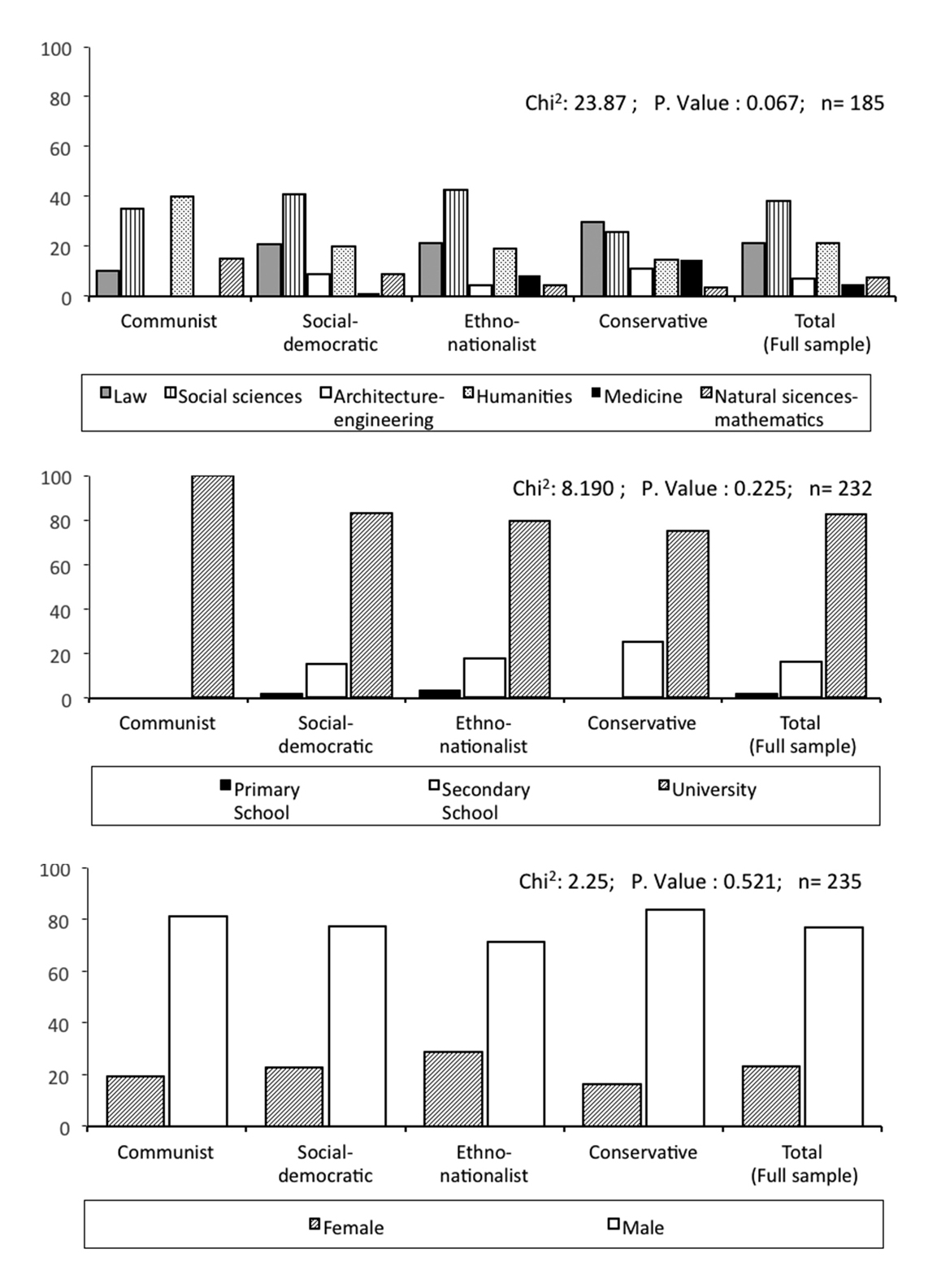

Finally, although party family —as suggested in the literature— stands as a dimension in which differences in mayors’ social profile can be observed (i.e. socialist parties tend to integrate more women among their ranks compared to conservative organizations; conservatives surpasses their counterparts in level of education), our data do not confirm these expectations (figure 4). For our community of respondents, party ideology is not a factor related either to gender or to educational achievement. Female mayors in our sample are slightly underrepresented in conservative parties, but differences are not statistically significant. The educational level (primary, secondary or higher education), for its part, is also unrelated to the party family local leaders belong to. However, in our sample, the vocational area of candidates’ university studies does vary by party affiliation, and differences are very close to the edge of statistical significance (P.Val.:0.067). Specifically, within the group of conservative mayors, a university degree in Law or in Medicine is more frequent than in mayors from other party families. And within the communist family, undergraduate degrees in humanities and natural sciences seem to be also more likely than in the rest. This result follows one of the patterns found in Spanish regional parliaments, where the conservative party doubles the proportion of lawyers of the socialist party ( Coller, Xavier, Helder Ferreira do Vale and Chris Meissner. 2008. Political elites in federalized countries: The case of Spain (1980-2005). Barcelona: Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials.Coller et al., 2008).

The professionalization of mayors [up]

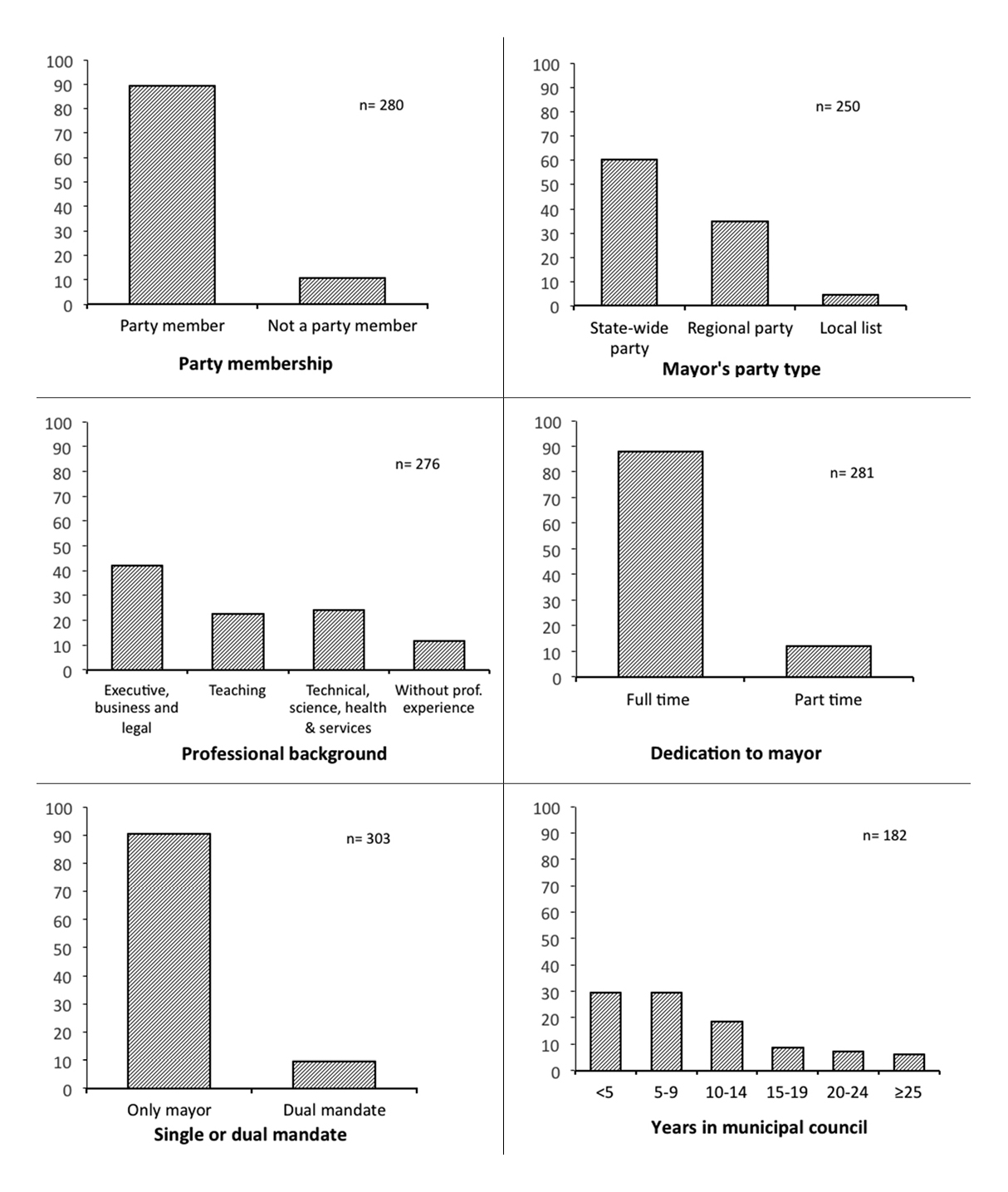

The data collected in our survey allow us to offer an assessment on the degree of professionalization of mayors, as well (figure 5). The standard profile in this dimension of analysis is a full-time mayor, member of a national or regional party, who has had a professional activity in a “talking and brokerage” profession and has a long trajectory of having served in the municipality as political officer, 10 years in the council on average. Therefore, the patterns of professional politicians apply both to focus (exclusivity, dedication) and to scope (duration, political trajectory).

Almost all mayors in our sample are in charge of the city government as a full-time activity with an extremely intensive dedication. Respondents report a dedication of 63 hours per week on average, and some of them place this figure at much higher values, close to one hundred hours per week (see descriptive statistics in the appendix). The conclusion is that being a mayor is not like other jobs. Typically, their obligations are not limited to preparative work for a mayor’s duties or meetings with the council, the executive board or the administrative staff. It extends to ceremonial and representative functions, field visits in the city, interactions with other authorities, political party meetings, etc. Many mayors describe an activity level of 15 hours a day, 7 days a week. On the other hand, the “full-time trait” could easily be anticipated considering that the study only surveys municipalities above 10 000 inhabitants, with larger tasks and responsibilities compared to smaller units. Beyond the general pattern of professionalization of local executives, size continues being closely connected to dedication. Part time mayors are concentrated in smaller towns.

What is an unequivocal signal of professionalisation is how spread party affiliation is among the components of this group and, more importantly, affiliation to state-wide parties (figure 5). A great majority of them are party members (89 %). More specifically, 50 % belong to a state-wide party and 29 % to a regional party. Only 5 % of the total has run for office in local lists. In comparative terms, Spain ranks among the first positions regarding the presence of national parties in local politics ( Bäck, Henry, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier (eds.). 2006. The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenshaften.Bäck et al., 2006; Heinelt, Hubert, Annick Magnier, Marcello Cabria and Herwig Reynaert (eds.). 2018. Political Leaders and Changing Local Democracy. The European Mayor. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.Heinelt et al., 2018).

Figure 5.

Professionalization of mayors’ career. Bar graphs represent percentage points

Source: POLLEADER, 2nd. round.

As the theory indicated, another feature that is usually connected to this pattern of recruitment is profession, the assumption being that professionalized politicians would tend to either have no work experience before getting their first elected position, or that they would come from “talking and brokerage” professional environments. The results of our survey’s support this expectation regarding the latter. Figure 5 reflects how 67 % of mayors come from executive, business and legal professions combined with educators. Only one in four have worked in technical, science and the health sector or in other services. However, and interestingly, only a small percentage of them (12 %) declare to have no experience in any professional sector other than a function in a political party organization.

Long experience in the local political life defines the career of mayors as well.

Our respondents have been in the municipal council for 10 years on average at the

time of the survey, mostly as councilors in the beginning, before ascending to the

top position in the city government In the Spanish local system the mayor is, at the same time, a councillor of the municipal

assembly.

The circumstance of holding a dual mandate in an elected body (or as in the French expression cumul de mandat) is not extensively spread among Spanish mayors. Holding another position while they are in office is considered to be another trait of professionalization. It refers to the circumstance of being at the same time in a provincial, regional or national legislature or in an executive body if the legal system allows (i.e. president of a provincial council). However, this trait seems to be more popular in other systems, like in France or in Ireland ( Kjær, Ulrik. 2006. “The mayor’s political career”, in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier (eds.), The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Kjaer, 2006). For our respondents, only 10 % of mayors are in this situation, combining the position of mayor mainly with a seat in the provincial council or executive body or in the regional parliament.

In sum, Spanish mayors have a remarkable level of professionalization, especially regarding involvement with parties and seniority in local politics. But, what about their political future, are they thinking about a political professional trajectory that leads them to the upper levels of representative office, either in regional or national parliaments or executives? Or would they rather remain at the local level or quit politics?

Mayors’ political ambitions [up]

Table 1 offers mayors’ answers to the question “for the time being, what are you planning

to do at the end of the present mandate” We have aggregated the different answers in four categories: 1) I want to continue

my political career as a mayor; 2) I want to continue my political career at the local

level but not as mayor; 3) I want to continue my political career at regional/provincial/national

or European level; 4) I want to quit politics to go back to private profession.

The answers are distributed as follows. Almost 60 % of Spanish mayors answering the questionnaire declare that they want to continue as mayor for another term. Nearly 30 % state that they want to quit politics and go back to their own profession; 7 % prefer to stay in local politics but not as mayor; and only 6 % express preference for a change of political arena, continuing their political career at provincial, regional, national level or European level.

Table 1.

Political ambitions of Spanish mayors after their current mandate

| Continue as mayor | 59 |

|---|---|

| Stay in local politics | 7 |

| Provincial-Regional-National politics | 6 |

| Back to own profession | 28 |

| Total | 100 |

| (n) 182 |

Source: POLLEADER 2nd round.

There are two categories with very small percentages, which reveal interesting logics in the mayors’ minds. First, stepping down from the first position in the city to a much less relevant job in the council is not a popular alternative. To understand this, we have to remember the characteristics of local government in Spain, where mayors are in full charge of all the executive functions and control the assembly whereas councils have a much weaker role. Considering councilors’ relative lack of political power and influence ( Navarro, Carmen. 2012. “Si la reducción de los concejales fuera la respuesta ¿cuáles son las preguntas? Cómo son y qué se espera de los líderes políticos locales”, Anuario de Derecho Municipal, 6, 165-181.Navarro, 2012) it is understandable that mayors do not see a reduction in rank as a foreseeable possibility. Second, although we know from other works that a relevant proportion of regional chambers’ members come from the local world either from councils or from mayoral offices ( Liñeira, Robert and Jordi Muñoz. 2016. “Profesionalización y trayectorias parlamentarias”, in Xavier Coller, Antonio Jaime and Fabiola Mota (eds.), El poder político en España: parlamentarios y ciudadanía Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.Liñeira and Muñoz, 2016), only a minority of respondents declare an ambition to pursue a political career, of which this is the first step in the trajectory. Here, there is probably a component of a socially desirable answer; mayors might interpret that declaring ambitions could be seen as being uninterested in the job. Therefore, although progressive ambitions are probably in the minds of more than those who declared them, we cannot conclude from these answers that local political elites conceive their current position as the starting point of a political trajectory that will lead them to regional or national arenas.

Given the small number of respondents declaring a preference for staying in local politics (not as mayor) or changing to another political arena (11 and 12 observations respectively) we will focus on the two main preferences that will constitute the two values of our dependent variable: continue as mayor or leave politics and go back to own profession.

In fact, what most mayors declare is the aim to remain as mayors. That is of outmost importance for these individuals. We then have to understand that, in the local context, the political career does not necessarily involve progressive ambitions but, in terms of professionalization, it does indicate that these elected officers have tended to replace other forms of employment by political activities and that the likelihood to return to this employment is low ( Guérin, Élodie and Eric Kerrouche. 2008. “From amateurs to professionals: The changing face of local elected representatives in Europe”, Local Government Studies, 34 (2), 179-201.Guérin and Kerrouche, 2008). However, there are still more than one in four mayors who do not follow this pattern. Instead, they want to quit politics and go back to their profession. What factors can explain the contrasting political ambition of these individuals?

In order to answer this question, we have performed a logistic regression analysis including as independent variables the factors mentioned in the theoretical part of this article. Briefly we expected that: being a male, young, not having a previous profession or university studies and being enrolled in a political party would increase political ambitions and the patterns of professionalization of mayors. The results from table 2 confirm most of our expectations and, interestingly, run contrary to others.

Table 2.

Logistic regression of the political expectations after the mandate as mayor (Dependent variable 0: Return to own profession, 1: Stay as mayor). S.E. in parenthesis

| Female | 2.109 p<0.01. (0.815) |

| Age | -0.028 (0.037) |

| University | -2.558 p<0.05; (1.132) |

| Previous occupation in private sector | -1.327 p<0.05; (0.642) |

| First/second elected in professional association | -1.712 p<0.1; (1.022) |

| Years belonging to party | 0.031 (0.040) |

| Support from local media in early career | 0.860 p<0.01. (0.322) |

| Hours per week spent as mayor | 0.076 p<0.01. (0.024) |

| Mayor in his/her first term | 2.730 p<0.01. (0.739) |

| Mayors’ party type (ref.: state-wide party) | |

| Belongs to regional party | -1.789 p<0.01. (0.682) |

| Belongs to a local list | -2.403 p<0.05; (1.200) |

| Inhabitants 2014 (logged) | -0.019 (0.398) |

| Constant | -2.189 (4.175) |

| Observations | 112 |

| Nagelkerke Ps.R2 | .59 |

| Log Likelihood | -42.276 |

First, contrary to what was expected and all the literature reports, female mayors are more ambitious than their male counterparts. This finding indicates that, for women who have already broken through the glass ceiling, assumptions about their lower levels of ambition do not apply. In their trajectory to the top position on the electoral list and then in the higher office of local politics they have already overcome the structural obstacles and bias in the recruitment processes and so they are well equipped to pursue a political career once they are there.

Second, regarding the other elements of the social profile, only education and previous profession (not age) explain differences. Not having university studies is connected to the wish to remain in politics. This can be the effect of the marginal opportunities for these individuals to return to an employment comparable with the one they currently hold. On the other hand, mayors with a professional profile connected to the private sector are more likely to want to quit politics than the rest. This is understandable as they are in politics at a higher cost, especially those with high professional credentials shown by the fact that they have been active in professional associations as well. They are significantly more prone to think about returning to their job when the current political term comes to its end.

Third, mayors with more dedication to the job and belonging to wide-state parties are logically those more embedded in patterns of political professionalization and, therefore express more ambition to continue in politics. Probably, part of the hours per week spent as mayors are devoted to the party and to political interactions other than those strictly linked to local policy issues.

Two more factors have an effect in the prospects of mayors for the future. When mayors are in the first term of office they are more inclined to continue. And they also express a wish to repeat for a second period when they have the support of the local media. We interpret these results in the context of the high level of personal demands when one is involved in local politics and how it can have a fatigue effect as years pass or when other actors in local governance are too hostile.

Finally, we observe that, in general, serving in larger municipalities seems not to be related to the political ambitions of the mayors.

CONCLUDING REMARKS[up]

This article has analyzed the social background and patterns of professionalization in the political recruitment of mayors, with own data coming from a questionnaire applied to a sample of 303 Spanish mayors in municipalities larger than 10 000 inhabitants. It has presented the main body of literature’s approaches and findings on the topic in order to look at the empirical data with appropriate conceptual lenses.

Spanish mayors follow to a great extent the patterns of political elites and particularly, those of local executives in other countries of Europe, but with some distinctive traits. In fact, like their European counterparts and the political elite in general, they are mainly male, middle-aged and highly educated. But, following a national pattern already identified in national elites, they are particularly young for European standards. The almost monopolistic presence of mayors belonging to political parties in the local arena stands as another sign of country specificity. This, together with the fact that a high proportion of them have been in local politics for relatively long periods of time and that they mostly wish to remain in politics (women in particular) place them in distinguishable patterns of political professionalization.

This study has left some issues of political recruitment aside and has raised some questions as suggestions for a future research agenda. First, this article has not gone into the implications of the normative aspects that emerge from the results of our analysis. Relevant as they are, they deserve a separate contribution —probably with the support of qualitative techniques— which seeks to analyze the specific interactions of supply and demand factors in the political recruitment processes at the local level and identify where exactly the selection towards a specific profile occurs. Second, in analyzing political ambitions of mayors we were unable to trace political trajectories that start at the local level and continue to other arenas. We know that local government is the nursery of many Spanish politicians, but this has not been revealed in our study. Again, additional studies that aim to reveal these processes would be worthwhile, not only to be able to connect the diverse political arenas of the multilevel Spanish governance but also to continue building with empirically develop our knowledge and understanding of how local governments function.

Notes[up]

| [1] |

A similar survey —POLLEADER I— was conducted between 2003 and 2004 across seventeen countries, whose main results are detailed in Bäck et al. ( Bäck, Henry, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier (eds.). 2006. The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenshaften.2006). |

| [2] |

This research has been financed by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness: «Una nueva arquitectura local: eficiencia, dimensión y democracia» (CSO213-48641-C2-1-R). |

| [3] |

The response options considered were: continue as mayor, stay in the local council but not as mayor, move to regional politics, move to national politics or return to a previous profession out of politics. |

| [4] |

For the party family we followed the classification by Andersson et al. ( Andersson, Staffan, Torbjörn Bergman and Ersson Svante. 2014. “The European Representative Democracy Data Archive, Release 3”. Main sponsor: Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (In2007-0149:1-E).2014). |

| [5] |

Following Norris and Lovenduski ( Norris, Pippa and Joni Lovenduski. 1995. Political recruitment: Gender, race and class in the British Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.1995) the professions were classified as: a) Executive, teaching, business and legal professions; b) Technical, scientific, health and services professions and c) Without a previous profession. |

| [6] |

The Act for Effective Equality (Ley Orgánica 3/2007, de 22 de marzo para la igualdad efectiva de mujeres y hombres) states that political parties should construct electoral lists in which the presence of candidates of the same sex cannot be below 40 percent or above 60 % within each section of five candidates. |

| [7] |

For Spain: below 10 000 inhabitants: 7359 municipalities; 10 000 to 20 000: 355; 20 000 to 50 000: 257; 50 000 to 100 000: 83; +100 000: 63. INE 2015. |

| [8] |

In the Spanish local system the mayor is, at the same time, a councillor of the municipal assembly. |

| [9] |

We have aggregated the different answers in four categories: 1) I want to continue my political career as a mayor; 2) I want to continue my political career at the local level but not as mayor; 3) I want to continue my political career at regional/provincial/national or European level; 4) I want to quit politics to go back to private profession. |

References[up]

|

Aars, Jacob, Audun Offerdal and Dan Rysavy. 2012. “The Careers of European Local Councillors: A Cross-National Comparison1”, Lex localis, 10 (1): 63. |

|

|

Andersson, Staffan, Torbjörn Bergman and Ersson Svante. 2014. “The European Representative Democracy Data Archive, Release 3”. Main sponsor: Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (In2007-0149:1-E). |

|

|

Bäck, Henry, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier (eds.). 2006. The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenshaften. |

|

|

Capo, Jordi, Montserrat Baras, Joan Botella and Gabriel Colomé. 1988. “La formación de una élite política local”. Revista de Estudios Políticos, (59): 199-224. |

|

|

Coller, Xavier, Helder Ferreira do Vale and Chris Meissner. 2008. Political elites in federalized countries: The case of Spain (1980-2005). Barcelona: Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials. |

|

|

Coller, Xavier, Antonio Jaime and Fabiola Mota. 2016. El poder político en España: parlamentarios y ciudadanía. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. |

|

|

Cotta, Maurizio and Heinrich Best. 2000. “Between Professionalization and Democratization: A Synoptic View on the Making of the European Representative”, in Maurizio Cotta and Heinrich Best (eds.), Parliamentary representatives in Europe, 1848-2000: legislative recruitment and careers in eleven European countries. Oxford. Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Dahlerup, Drude and Monique Leyenaar. 2013. Breaking male dominance in old democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Denters, Bas and Lawrence E. Rose. 2005. Comparing Local Governance. Trends and Developments. Basingstoke, UK : Palgrave Macmillan. |

|

|

Duverger, Maurice. 1955. The Political Role of Women. Paris: Unesco. |

|

|

Eulau, Heinz and Kenneth Prewitt. 1973. Labyrinths of Democracy: Adaptations, Linkages, Representation, and Policies in Urban Politics. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. |

|

|

Franceschet, Susan, Mona L. Krook and Jennifer M. Piscopo. 2013. The impact of Gender Quotas. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Guérin, Élodie and Eric Kerrouche. 2008. “From amateurs to professionals: The changing face of local elected representatives in Europe”, Local Government Studies, 34 (2), 179-201. |

|

|

Heinelt, Hubert, Annick Magnier, Marcello Cabria and Herwig Reynaert (eds.). 2018. Political Leaders and Changing Local Democracy. The European Mayor. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. |

|

|

Instituto de la Mujer y para la Igualdad de Oportunidades. (s. f.). Mujeres en Cifras. Poder y Toma de Decisiones. Administración Local. Available at: www.inmujer.gob.es [Last accessed February 2017] |

|

|

Iversen, Torben and Frances Rosenbluth. 2008. “Work and power: The connection between female labor force participation and political representation”, Annual Review of Political Science, 11: 479-495. |

|

|

Kjær, Ulrik. 2006. “The mayor’s political career”, in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier (eds.), The European Mayor. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. |

|

|

Kittilson, Miki C. 2013. “Party Politics”, in Georgina Waylen, Karen Celis, Johana Kantola and Laurel Weldon (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Kittilson, Miki C. 2006. Challenging Parties, Changing Parliaments: Women and Elected Office in Contemporary Western Europe. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press. |

|

|