Mayors’ perceptions on local government reforms and decentralization in Spain

Percepciones de los alcaldes sobre las reformas y la descentralización en España

ABSTRACT

This article analyses Spanish Mayors’ perceptions on three areas of possible reforms that are currently on the local government agenda: re-scaling, amalgamations and metropolitanization. This study shows two main features: On the one hand, a relative homogeneity regarding mayors’ perceptions of reforms and, on the other hand, a consistent difference in the mayors’ orientations from two groups of autonomous communities. The first ones acceded to the “fast track” decentralization process that unfolded in Spain since 1978, due to the pressure exerted by their political leaders; the second group acceded to autonomy in a later wave, equating the distribution of power in all the territories of the state.

Specifically, it is found that homogeneity in responses is only apparent when the two groups of mayors are considered. Thus, those from “fast track” regions are more in favor of decentralization towards their regions and structures of coordination or cooperation between levels of government than mayors in “slow track” autonomous communities. We conclude that, in a scenario of shared power and multilevel interdependence, fast-track mayors tend to protect more intergovernmental agreements that favor spaces where they can control the formulation of policies that affect them.

Keywords: mayors, local government, amalgamation, metropolitan governance, decentralization.

RESUMEN

Este artículo analiza la percepción de los alcaldes españoles en tres áreas de posibles reformas que actualmente están en la agenda del gobierno local: reordenación, fusiones y creación de gobiernos metropolitanos. Este estudio revela dos características principales. Por un lado, una homogeneidad relativa de las posiciones de los alcaldes respecto a las reformas y, por otro, una diferencia consistente en las orientaciones de los alcaldes de alcaldes de dos grupos de comunidades autónomas. Las primeras accedieron al proceso de descentralización por la vía rápida que se desplegó en España a partir de 1978, debido a la presión ejercida por sus líderes políticos; el segundo grupo accedió a la autonomía en una ola posterior, equiparando la distribución del poder en todos los territorios del Estado.

Específicamente, se ha descubierto que la homogeneidad en las respuestas sólo se aprecia cuando se consideran los dos grupos de alcaldes mencionados. Así, los de las regiones de la vía rápida están más a favor de la descentralización hacia sus regiones y de estructuras de coordinación o cooperación entre niveles de gobierno que los alcaldes en las comunidades autónomas de la vía lenta. Concluimos que, en un escenario de poder compartido y de interdependencia multinivel, los alcaldes de la vía rápida tienden a proteger más los acuerdos intergubernamentales que favorezcan los espacios donde puedan controlar la formulación de políticas que los afectan.

Palabras clave: alcaldes, gobierno local, fusiones, gobernanza metropolitana, descentralización.

CONTENTS

- Abstract

- Resumen

- THE TERRITORIAL ISSUE AND THE SPANISH MULTILEVEL GOVERNANCE SYSTEM

- BUILDING AN ASYMMETRIC DECENTRALIZED STATE BEHIND THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT’S BACK

- MAYORS’ GENERAL PERCEPTIONS OF REFORMS IN TROUBLED TIMES

- Mayors’ perceptions on re-scaling reforms and amalgamations

- Metropolitan arrangements in Spanish mayors’ perceptions

- HYPOTHESIS AND MAIN RECODIFICATIONS

- THE PERSISTENT AND (STILL) OBSERVABLE EFFECT OF POLITICAL AND INSTITUTIONAL DIFFERENTIATION

- CONCLUSIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Notes

- References

THE TERRITORIAL ISSUE AND THE SPANISH MULTILEVEL GOVERNANCE SYSTEM[up]

Today, Spain is a highly decentralized country. However, the process of devolution started quite recently, in the early 1980s following the approval of the 1978 Spanish Constitution. The process of decentralization of the old unitary state was mainly driven by territorial pressures, especially coming from Catalans and Basques, and to a lesser extent, from Galicians, because this process was not clearly designed in the Constitution. Therefore, territorial issues, particularly the functioning and legitimation of the distribution of political powers between the regions and the state has been a controversial subject since the beginning of democracy.

In the process of decentralization of Spain, some regional political powers appeared as either leaders and laggards. The leaders were the main resistant territories during the Francoist regime, namely, those identified with a more democratic resistance and which enjoyed some political autonomy under the first Republic (1931 to 1939) before the Spanish civil war. Their stronger democratic struggle against Franco served to identify peripheral nationalist claims of strong self-government as democratic claims that needed to be treated differently in the new Constitution. Therefore, Catalonia, Galicia and especially the Basque Country recovered regional self-government with a faster and deeper institutional setting. For other political reasons, Andalusia also reached this “fast-track”, even if it has never been very different from the rest of Spain in cultural, historical or linguistic terms.

This foundational division between “fast-” and “slow-track” regions has been largely

scrutinized at diverse levels and with different approaches. It has been argued to

have different political effects on citizens’ perceptions and behaviors ( León, Sandra. 2011. “Who is responsible for what? Clarity of responsibilities in multilevel

states: The case of Spain”, European Journal of Political Research, 50 (1): 80-109. Available at:

However, up to the present, no work has paid attention to this divide when considering mayors’ perceptions of multilevel arrangements and territorial reforms. Mayors play a crucial role in legitimizing the political system in a country with more than 8000 municipalities. Therefore, their views and positions over local reforms are of undoubted relevance in academic fields. Indeed, mayors are privileged actors inside the local councils, with specific agendas and perceptions over territorial reforms potentially affecting them. We assume that mayors are “captured” inside the actual, nested multilevel scenario, and therefore, their perceptions of territorial reforms might be in some way affected by this fact. Therefore, this work links the institutional design of decentralized Spain with the willingness of local government reforms to study their relationship.

Therefore, in complex multilevel settings, crossed by organizational and identity issues, mayoral perceptions of territorial reforms and options may also be affected (or mediated) by these different institutional and identity settings. That is to say, even with a high and quite homogeneous level of decentralization at the regional level, strong standardized regulation at the local level and regional-centralism, as we will see further on, we can still account for differences in perceptions based on this foundational dichotomy between fast-track and slow-track regions.

Thus, taking as a starting point the absence of strong differences among mayors’ perceptions due to some institutional isomorphism, our theoretical argument functions as follows: mayors belonging to fast-track regions will be more prone to reforms and changes in the multilevel system only when these reforms are designed to preserve both strong regional powers and intermunicipal cooperation. The basic assumption is that, in a scenario of shared powers and wide multilevel interdependence, mayors in fast-track regions will be more likely to shield their main intergovernmental arenas. In sum, by preferring stronger regions and intermunicipal cooperation —rather than amalgamations or reductions in the power of regions— they are in fact willing to limit a wider spread of power across “non-close” tiers. Conversely, mayors in slow-track regions are more likely to show more attenuated preferences for reforms empowering regions and intermunicipal cooperation because the perceived importance of the regional level is not as deeply felt as in fast-track regions. Nevertheless, it is worth noting from the very beginning that we draw neither a strong divide nor a fundamental split separating Spanish mayors; rather, we aim at scrutinizing the dim but lasting effects of a foundational constitutional divide and the effect of some sort of regional nationalism in mayors’ perceptions.

We organize our work as follows: after this introduction, we build a theoretical part where we briefly describe and explain the multi-layered and complex architecture of Spain, followed by a descriptive analysis of the mayors’ responses of regarding the three main sources of reforms that have been implemented (or attempted) in Spanish local governments: re-scaling, amalgamations and metropolitanisation. In the fourth section, we specify our hypotheses and main recodifications. We use data from the second round of the Political Leaders in European Cities survey (2015-16), which sought to study the role of mayors and the transformation of political representation at the local level in several European countries. Afterwards, the fifth section presents of the results of the analysis, followed by some general conclusions.

BUILDING AN ASYMMETRIC DECENTRALIZED STATE BEHIND THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT’S BACK[up]

The political process of decentralization from 1978 to the mid-1980s was far from straightforward. Powerful territorial elites’ pressures were in place to determine the final structure of the new decentralized state. Today, Spain is formed by seventeen Autonomous Communities (ACs) —but none of them is specifically named in the Constitution—, fifty provinces (second-tier units of local government) and 8124 municipalities. In fact, the l process of transition was so tempestuous that, because of the need for an agreement between all actors involved, the Constitution finally approved only a formal procedure to regionally decentralize the state. A striking feature of this procedure is the absence of a clear number, scope or concrete competencies of the new regional units that were to be created. Thus, this procedural provision in the Constitution led to a process from 1978 to 1985 where most of the actual AACC were created, through the Estatutos de Autonomía, in some sort of multiple bilateral negotiations between central and territorial elites.

The controversial, and rather nebulous, article two of the Constitution points from

the beginning and together with the insoluble unity of the state, to a political differentiation

among “ordinary regions” and “nationalities”: “The Constitution is based on the indissoluble

unity of the Spanish nation, the common and indivisible country of all Spaniards;

it recognizes and guarantees the right to autonomy of the nationalities and regions

of which it is composed, and the solidarity amongst them all”. This foundational dichotomy

between a differentiated set of four more powerful regions lasted, in juridical terms,

up to 1992, where an increase in self-government capacities for slow-track (ordinary)

regions was generally implemented, formally equalizing the system, representing a

second wave of decentralization. In fact, the system implemented according to the

Constitution has proved to be highly political, since no clear constitutional provisions

are in place, and the decentralizing dynamics and the intergovernmental game are characterized

by a deep political struggle ( Agranoff, Robert and Juan A. Ramos-Gallarín. 1997. “Toward Federal Democracy in Spain:

An Examination of Intergovernmental Relations”, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 27 (4): 1-38.Agranoff and Ramos-Gallarín, 1997; Aja, Eliseo and César Colino. 2014. “Multilevel structures, coordination and partisan

politics in Spanish intergovernmental relations”, Comparative European Politics, 12 (4-5): 444-467.

The Spanish devolved system underwent a third wave of change, a process led again by fast-track regions, which began with the failure to approve a new Statute of the Basque Country, and the approval in 2006 of the Catalan Statute. The latter was brought before the Constitutional Court, which issued the crucial Sentence 31/2010. This limited the federative evolution of Spain, thus frustrating the attempt to increase the weight of autonomous powers set out by regions, especially over the regulation of local governments ( Galán, Alfredo and Ricard Gracia Retortillo. 2011. “Estatuto de autonomía de Cataluña, gobiernos locales y Tribunal Constitucional”, Revista d’Estudis Autonòmics i Federals, 12: 237-301.Galán y Gracia, 2011). As a matter of fact, the decentralization process was mainly addressed to empower regional units, rather than local ones, which were dramatically left outside the debates during the transition and the consequent institutional design ( Rodríguez Álvarez, José María. 2011. “El gobierno local en España desde mediados del siglo XX: continuidades y cambios”, in Arenilla (ed.), La administración pública entre dos siglos: ciencia de la administración, ciencia política y derecho administrativo: Homenaje a Mariano Baena del Alcázar. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Administración Pública.Rodríguez, 2011).

Concerning local governments, a completely different path of decentralization and institutional design was in place during the transition. The fundamental number of units, basic functions and structure remained untouched from the dictatorship (and before, coming from the mid-18th century). The whole process of the democratic transition was made without democratically elected politicians at the local level, and the first free elections for the local government were held in 1979, almost half a year after the approval of the Constitution. From an institutional perspective, local governments were totally left outside the transition and devolution processes, and this was translated into the absence of a set of minimal competencies and also the weakness of the basic traits of local structures. Indeed, the basic law regulating local governments was not in force until 1985, seven years after democracy was in place[1]. It is true that local political autonomy is constitutionally granted; however, in practical terms, it is narrow and conditioned. Moreover, since the approval of the Ley 27/2013, de 27 de diciembre, de Racionalización y Sostenibilidad de la Administración Local (also known as LRSAL), the question of how local governments must be organized in a complex multilevel scenario has put the reorganizational aspects at the top of the political agendas.

Therefore, the legal configuration of local governments is quite particular, an expression

of a fussy multilevel system, where the state dictates the basic regulations and the

AACC can develop and implement this legal basis. Some authors claim Spanish local

governments had moved from a “central centralism” under Francoism to a “regional centralism”,

where municipalities mostly depend on AACC’s decisions and regulations ( Velasco Caballero, Francisco. 2014. “El nuevo régimen local general y su aplicación

diferenciada en las distintas comunidades autónomas”, Revista Catalana de Dret Públic, 48: 1-23. Available at:

When it comes to analyzing local governments and intergovernmental relations, scholars tend to look at the relative place and objectives of municipalities embedded in the multi-tiered system. For the Spanish case, their intergovernmental relations are strongly conditioned by the fact that the budget of each municipality is quite contingent on transferences from both the central and regional levels. Therefore, municipalities are not provided with financial autonomy that is powerful enough to fulfil their political autonomy. This complex landscape puts local governments in a difficult position, where local elites fight to ensure some independence in a process of consolidation of local levels of government, which has been characterized by the intervention of both the central government and regional governments.

In this scenario, some authors argue that the system of intergovernmental relations in Spain is much more political than in other federal countries ( Agranoff, Robert. 2010. Local governments and their intergovernmental networks in federalizing Spain. Québec: McGill-Queen’s University Press.Agranoff, 2010). In this sense, the entire Spanish intergovernmental system is strongly marked by the political relations among levels of government and the lack of transparency and accountability of those links ( Agranoff, Robert. 2007. “Local governments in Spain’s multilevel arrangements”, in H. Lazar y C. Leuprecht (eds.), Spheres of governance. Québec: McGill-Queen’s University Press.Agranoff, 2007). In small and medium towns, local elites use their skills and contacts to conduct intergovernmental transactions ( Agranoff, Robert. 2010. Local governments and their intergovernmental networks in federalizing Spain. Québec: McGill-Queen’s University Press.Agranoff, 2010), promoting, at a first sight, regional governments to have a predominant role in the whole system.

As a result, Spanish localities are a canonical member of the “Napoleonic” or “Franco-type” form of local government, mainly located in the south of Europe ( Heinelt, Hubert and Nikos Hlepas. 2006. “Typologies of Local Government Systems”, en Annick Magnier and Henry Bäck (eds.), The European mayor: political leaders in the changing context of local democracy. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Heinelt and Hlepas, 2006). This group of local government systems is characterised by a high level of political autonomy and elite bargaining capabilities, but with low functionality —which is to say, low performance in terms of output production ( John, Peter. 2001. Local governance in Western Europe. London: Sage.John, 2001; Page, Edward and Michael Goldsmith. 1987. Central and local government relations :a comparative analysis of West European unitary states. London: Sage.Page and Goldsmith, 1987; Wolman, Harold and Michael Goldsmith. 1992. “The study of urban politics and policy”, in Wolman and Goldsmith (eds.), Urban politics and policy: a comparative approach. Wolman and Goldsmith, 1992). This southern group, originally formed by Spain, France, Greece and Portugal, seems to cling mostly to the idea of a strong local representative elite and a centralised bureaucracy. Its members’ notion of democracy is more related to creating a sense of identification around the mayor as a powerful representative of the local community, rather than any other consideration ( Haus, Michael and David Sweeting. 2006. “Mayors, Citizens and Local Democracy”, en Annick Magnier and Henry Bäck (eds.), The European mayor: political leaders in the changing context of local democracy. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Haus and Sweeting, 2006; Magre, Jaume and Xavier Bertrana. 2005. “Municipal presidentialism and democratic consolidation in Spain”, in Berg and Rao (eds.), Transforming local political leadership. Basingstocke: Palgrave McMillan.Magre and Bertrana, 2005). The political expression of local autonomy, together with the generalised lack of capabilities and resources, is a constellation of strong political institutions with narrow margins for real manoeuvres, and with a low or very moderate economic impact in aggregate terms.

MAYORS’ GENERAL PERCEPTIONS OF REFORMS IN TROUBLED TIMES[up]

It is noteworthy that since 1985 there have been several attempts to reform local governments in Spain without much success; but the main reforms addressed by the questionnaire have regularly been on the political agenda. The main political and academic debates concerning the Spanish local government system had turned around the constitutional fit of local governments, questions of funding and competences and the nature and extent of inter-municipal cooperation. By happenstance, most of them were of the utmost relevance at the time when the fieldwork was conducted. We will comment on three basic sets of questions. A first group of questions refers to re-scaling processes, followed by a piece on amalgamations, which mainly coincide with LRSAL reform. The third set refers to processes of metropolitanisation, which are also on the Spanish political agenda, but less clearly articulated.

Under the concept of re-scaling reforms, it is usually considered all those measures and decisions aiming to change and move political capacities and competences between levels of government, including horizontal and vertical movements. Under the amalgamation concept, it is usually considered all kinds of mergers and fusions of local political units, generally in order to improve their economic performance (generating economies of scale). Finally, metropolitanization usually includes all kind of actions tending to create processes of metropolitan institution building.

The questionnaire devoted up to six questions to mayors’ perceptions concerning the more usual reforms on local governments. These questions are designed to be answered by mayors regardless their country, and regardless of whether a concrete reform is in place or not. The questions address individuals’ perceptions, from which we can only extract individual willingness, or the degree of individual agreement for each concrete reform. Regarding our data, the survey received responses from mayors elected in municipalities larger than 10 000 inhabitants; the original sample size was 752 mayors (all municipalities beyond that population threshold), and the actual responses amounted to 303, which yields a response rate of 40 %. Despite the low response rate, the final sample is rather representative of the studied universe both in terms of territorial distribution and gender, and therefore, we do not expect the results to be biased due to an unbalanced response rate.

Mayors’ perceptions on re-scaling reforms and amalgamations[up]

The re-scaling reforms of LRSAL are framed in the context of an economic crisis and

under the indications of European and international organizations. Thus, the conductive

line content was clearly dominated by an overall objective of ensuring the financial

sustainability at the municipal level. The LRSAL reform has been the widest, but still

an ineffective, reform of the Spanish local governments’ system ( Galán, Alfredo. 2015. “La aplicación autonómica de la Ley de Racionalización y Sostenibilidad

de la Administración Local”, Revista de Estudios de La Administración Local y Autonómica, núm. extraordinario.Galán, 2015), and an attempt to control local governments’ budgets, with limited effects though

( Medir, Lluís, Esther Pano, Alba Viñas and Jaume Magre. 2017. “Dealing with Austerity:

a case of local resilience in Southern Europe”, Local Government Studies, 43 (4): 621-644. Available at:

The LRSAL was backed and designed mainly by the central state, approved solely thanks to the absolute majority of the conservative party (PP) in Congress from 2011 to 2015. The reception of this bill was far from peaceful from other tiers of government. Specifically, regions and municipalities opposed it, since the proposed homogenous regulation challenged not only municipalities’ powers, but regions’ self-government on local matters: “The autonomous communities have also opposed local reform. They have raised the flag of the defense of the autonomy of their local entities, but mainly they were acting against what they considered a State invasion of their powers” ( Galán, Alfredo. 2015. “La aplicación autonómica de la Ley de Racionalización y Sostenibilidad de la Administración Local”, Revista de Estudios de La Administración Local y Autonómica, núm. extraordinario.Galán, 2015: 12). In this scenario, two main adverse reactions to the LRSAL are clearly identified by Galán ( Galán, Alfredo. 2015. “La aplicación autonómica de la Ley de Racionalización y Sostenibilidad de la Administración Local”, Revista de Estudios de La Administración Local y Autonómica, núm. extraordinario.2015): several appeals to the constitutional court, challenging most of the contents of the law on the one hand, and the blocking and reinterpretation of the regional implementation of the law on the other hand. In fact, the autonomous communities have chosen not to proceed to autonomic development of the precepts of the LRSAL, or to do it in a very restricted way, usually driven by the intention to obstruct its application regardless of the political party governing the region. As a result, we can claim that the bill is still under “non-practical implementation”. Nevertheless, its political impact is enormous.

How does this tumultuous situation translate into the mayors’ general perceptions? Question 29 asks about how desirable or undesirable were considered five “classical” reforms affecting local governments: decentralization of tasks to the municipalities; decentralization of tasks to the regions; reduction in the number of counties; reduction in the number of regions; and creating metropolitan governments. All of these are answered on a Likert scale from highly undesirable to highly desirable. Table 1 shows the raw percentage for every reform in our sample.

First, there is the question of decentralization of tasks to municipalities. As it can be reasonably expected, 47,7 % of respondents considers decentralization of tasks to municipalities as a desirable reform and 27,6 % a highly desirable reform. However and significantly, if we take into account the fact that those are mayors’ responses, 7,8 % of them considers decentralization to municipalities to be undesirable.

Table 1.

Percentages of mayors on desirability of re-scaling reforms

| Decentralization of tasks to municipalities | Decentralization of tasks to the regions | Reduction in the number of counties | Reduction in the number of regions | Creating metropolitan governments | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||||||||||

| Highly undesirable | 6 | 2,1 | 8 | 2,8 | 48 | 17,3 | 60 | 21,5 | 16 | 5,8 | ||||||||||

| Undesirable | 16 | 5,7 | 22 | 7,8 | 85 | 30,6 | 88 | 31,5 | 56 | 20,4 | ||||||||||

| Neither desirable nor undesirable | 48 | 17,0 | 45 | 16,0 | 113 | 40,6 | 103 | 36,9 | 127 | 46,4 | ||||||||||

| Desirable | 135 | 47,7 | 123 | 43,8 | 17 | 6,1 | 18 | 6,5 | 64 | 23,4 | ||||||||||

| Highly desirable | 78 | 27,6 | 83 | 29,5 | 15 | 5,4 | 10 | 3,6 | 11 | 4,0 | ||||||||||

| Total N | 283 | 100,0 | 281 | 100,0 | 278 | 100,0 | 279 | 100,0 | 274 | 100,0 | ||||||||||

Source: European Mayor 2nd. Round.

On a second issue, mayors were asked to rate the desirability of enhancing decentralization to regions. Here we found a strong pattern, where 73,3 % of respondents considers this reform to be a (highly) desirable one, and only 10,6 % considers it undesirable. These results seem consistent in the LRSAL context, where regions have been the main protective shield of local governments’ autonomy. Congruently, when asked about the reduction in the number of regions, only 10,1 % of mayors considers this reform as desirable, even if 36,9 % of them do not take side for any option, probably reflecting the convenience of status quo.

Patterns seem less clear when asking about the reduction of counties and the creation of metropolitan governments. With respect to the former, almost 90 % of the answers are distributed among the categories highly undesirable (17,3 %), undesirable (30,6 %) and neither desirable nor undesirable (40,6 %). Concerning the latter, opinions are more divided, with a high percentage (46,4 %) of ambiguous answers (neither desirable nor undesirable). The rest of the opinions are quite polarized: 5,8 % considers it highly undesirable and 20,4 % undesirable, while 23,4 % considers desirable and 4 % highly desirable. These answers are logical for the Spanish case, where there has been no national policy of metropolitan reforms. The picture emerging from this first set of questions clearly shows wide support for local governments’ decentralization and, especially, to empower autonomous communities. These results show that the aforementioned “regional centralism” is perceived as a suitable and comfortable intergovernmental arena for Spanish mayors.

On the same re-scaling debate, in recent years, Europe has found itself immersed in

a grave economic crisis that has reopened old debates about the strategies available

to public administrations with regard to the rationalization and economizing of their

resources in order to reduce public deficit. This has led to different member states

pushing through policies of austerity and a reduction in expenditures that, in some

cases, have resulted in a profound transformation of municipal structures. Along these

lines, in 2010, Greece completed a reorganization of its municipal map that resulted

in a reduction in the number of municipalities to practically one-third of those that

had existed up to that time. Some other European countries had also previously entered

into this debate, one example of which was the redrawing of the Danish municipal map

in 2008 ( Bertrana, Xavier and Hubert Heinelt. 2013. “The Second Tier of Local Government in

the Context of European Multi-level Government Systems: Institutional Settings and

Prospects for Reform”, Revista Catalana de Dret Públic, 46: 73-89. Available at:

LRSAL also devoted some room to the promotion of amalgamations, since Spain’s municipal map is highly fragmented and unequally distributed in the territory. On the one hand, this is based on a few population centers, mainly urban, with a very high population density and, on the other hand, on a high number of medium-sized or small centres with low population densities, located in inland areas of the country. This fragmentation has often been seen as an impediment to taking on, developing and providing public services, given that the Spanish Local Government Regulatory Law, 7/1985, defines the municipality as an essential body in terms of territorial organization, which is provided with its own legal entity and full capacity to exercise the public functions that it is charged with. In effect, the application of the law requires that the municipality, whether on its own or in collaboration with another entity, must provide a series of obligatory services, the extent of which will depend on its size. Apart from these generalized, obligatory services, other sectorial laws also attribute a number of functions to town or city councils that, in many cases, do not establish any limit in terms of population, as the provision thereof is, in principle, obligatory for all municipalities.

Concerning amalgamations, the Spanish state has not remained at the margins of this European tendency. Indeed, the first drafts of LRSAL provided for the suppression of all municipalities with populations under 5000 inhabitants, along with their absorption into a neighboring municipality should the provision or financial sustainability not comply with the standards of quality stipulated in the text of the law. However, the final version of the bill in 2013 introduced technical, specific measures aimed only at encouraging the voluntary merging of municipalities and introducing a new procedure for mergers between neighbouring councils within the same province, by way of the so-called “convenio de fusión” —merger agreement— ( Calonge Velázquez, Antonio. 2015. “La fusión de municipios, único instrumento de la Ley 27/2013, de 27 de diciembre, de racionalización y sostenibilidad de la Administración Local para la modificación de la planta municipal: una oportunidad perdida”, Revista de Estudios de la Administración Local y Autonómica, núm. extraordinario.Calonge, 2015).

In this regard, and to understand the evolution of the bill, it must be taken into

account that, generally speaking, autonomous communities have an exclusive competence

with regard to their municipal structure. Consequently, the policy regarding municipal

structure (and as a result, municipal mergers) corresponds to each autonomous community.

The Spanish Constitution, firstly, followed by the Statutes of Autonomy allow the

different autonomous communities to take responsibility for the process of reform

and modernization of their territorial organization structures ( Calonge Velázquez, Antonio. 2015. “La fusión de municipios, único instrumento de la

Ley 27/2013, de 27 de diciembre, de racionalización y sostenibilidad de la Administración

Local para la modificación de la planta municipal: una oportunidad perdida”, Revista de Estudios de la Administración Local y Autonómica, núm. extraordinario.Calonge, 2015). The central State itself may only partially condition the exercise of these regional

competences through its power to establish the basic rules of local government ( Velasco Caballero, Francisco. 2014. “El nuevo régimen local general y su aplicación

diferenciada en las distintas comunidades autónomas”, Revista Catalana de Dret Públic, 48: 1-23. Available at:

Notwithstanding the direction taken in recent years by the regulations concerning municipal structure in Europe, in Spain, mayors have notably distanced themselves from these trends; Spanish mayors were asked to choose between amalgamation and inter-municipal cooperation in order to provide improvements to certain aspects associated with municipal management (question 30). It must also be taken into account that, in a context of municipal fragmentation and minifundismo (division into small units), the creation of second-level institutions and the use of instruments of cooperation have represented a clear alternative to amalgamations. In this case, the goal of the entity is centered on a double function: on the one hand, to operate as a support mechanism making the presentation of the service possible, above all, for very small municipalities; and, on the other, to incorporate economies of scale through an increase in the volume of the provision. Definitively, these two mechanisms (amalgamation and cooperation) are often considered as possible ways of compensating for municipal fragmentation.

Thus, the mayors were presented with the dichotomy between amalgamation and inter- municipal cooperation, based on four axes that, in the end, are those highlighted by the academic literature —i.e., the professionalization of public servants, the quality of the public service, economic costs and political participation. Table 2 shows their answers.

Table 2.

Percentage of mayors on effectiveness of amalgamations or intermunicipal cooperation

| Professionalization of administrative staff | Service quality | Cost saving | Political participation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Intermunicipal cooperation is more effective | 127 | 45,8 | 180 | 65,5 | 168 | 60,0 | 95 | 34,3 |

| Amalgamation is more effective | 30 | 10,8 | 43 | 15,6 | 90 | 32,1 | 24 | 8,7 |

| There is no real utility in cooperation or amalgamation | 120 | 43,3 | 52 | 18,9 | 22 | 7,9 | 158 | 57,0 |

| Total N | 277 | 100,0 | 275 | 100,0 | 280 | 100,0 | 277 | 100,0 |

Source: European Mayor 2nd Round.

In each of the cases presented, inter-municipal cooperation turns out to be largely the preferred mechanism. The surprising thing, in view of the distribution of the results is, first of all, the unanimity in considering that mergers are not the best instrument for dealing with local government rationalization, distancing the Spanish local elite from the regulatory solutions that have been introduced recently and, above all, separating them from the analysis of many academics who continue to insist on the benefits of amalgamation. It is only recently that studies have appeared that place these solutions in any doubt ( Magre, Jaume and Esther Pano. 2012. “La reobertura del debat sobre la fusió municipal: buscant la resposta a algunes preguntes”, Anuari Polític, 2011: 153-159.Magre and Pano, 2012). Moreover, it is only when the question is raised regarding economic benefits that the percentage of endorsements for municipal amalgamation increases, to the point of reaching a third of those interviewed. While it is true that the main argument that has supported the different merger proposals is of an essentially economic aspect ( Christoffersen, Henrick, Martin Paldam and Allan Wurtz. 2007. Public versus private production and economies of scale, Public Choice, 130 (3): 311-328.Christoffersen et al., 2007; Bel, Germà and Antonio Miralles. 2003. Factors influencing privatization of urban solid waste collection in Spain. Urban Studies, 40: 1323-1334.Bel, 2003), those in favor of inter-municipal cooperation as a means of achieving a saving in costs duplicates those that consider mergers to be the best instrument.

Metropolitan arrangements in Spanish mayors’ perceptions[up]

The 20th century has witnessed the transformation of the European territory: nearly three-quarters of the European population currently live in metropolitan and urban areas (Eurostat, 2014). The challenges posed by the metropolitan phenomena are diverse, including those related to political and institutional issues (like the coordination of policies and services or democratic representation). The debate on how metropolitan areas, urban agglomerations and, more recently, city-regions, should be governed has become recurrent in the field of urban studies (for a review see Savitch, Hank and Robert Vogel. 2009. “Regionalism and Urban Politics”, in Jonathan S. Davies and David L. Imbroscio (eds.), Theories of urban politics. London: Sage.Savitch and Vogel, 2009; Tomàs, Mariona. 2012. “Exploring the metropolitan trap: the case of Montreal”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 36: 554-567.Tomàs, 2012). Most of the literature has focused on showing which is the appropriate model of metropolitan governance, ranging from high institutionalized models to informal arrangements and showing different conceptions of democracy and efficiency at the local and metropolitan scale ( Heinelt, Hubert and Daniel Kübler. 2005. Metropolitan Governance. Capacity, democracy and the dynamics of place. ECPR Studies in European Political Science. London and New York: Routledge.Heinelt and Kübler, 2005).

Evidence from diverse comparative studies on models of metropolitan governance according

to their level of institutionalization shows that metropolitan areas in Europe and

North America are mostly fragmented political spaces and that powerful metropolitan

governments are exceptional ( OECD. 2015. Governing the City. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available at:

In our survey, some questions are related to the mayors’ role in this system of multilevel governance and the way they conceive institutional reforms and the models of metropolitan governance. Despite evidence of a metropolitanization process, the Spanish political system has not responded to this phenomenon ( Alba, Carlos and Carmen Navarro. 2005. “Metropolitan Areas in Spain, a diverse and unknown reality”, in V. Hoffmann-Martinot y J. Sellers (eds.), Metropolitanization and Political Change, Wiesbaden: Springer.Alba and Navarro, 2005). The central government has not given incentives for the creation of metropolitan areas and this issue has not been important in the political agenda. At a state level, a bill approved in 2003[3] aimed at modernizing the management of councils and the development of citizen participation in large cities, recognizes that these bigger cities share some particularities, but the law does not address metropolitan problems. In 2006, the cities of Madrid and Barcelona were given special status as the biggest Spanish cities[4]. However, in these two special laws there are no references to or dispositions regarding the metropolitan scale. In sum, governing metropolitan areas is a decentralized competence that, a priori, should open the door to the existence of a plurality of models of metropolitan governance, as in federal states such as Germany ( Heinelt, Hubert and Karsten Zimmermann. 2011. “How Can We Explain Diversity in Metropolitan Governance within a Country? Some Reflections on Recent Developments in Germany”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35 (6): 1175-1192.Heinelt and Zimmermann, 2011).

The law regulating local government sets a general framework of local government, while it establishes that the regions are responsible for creating, modifying and abolishing metropolitan areas through their own Statutes of Autonomy (article 43 of the law regulating local government). In other words, specific legislation on the issue is necessarily regional, while the central government determines general legislation (laws on local financial resources, on local government, etc.). This may explain why there is not an official statistical definition of “the metropolitan phenomenon” in Spain; it is considered a regional affair. Unlike countries such as the United States or Canada, there is no systematic statistical definition to define metropolitan areas. In fact, the National Institute of Statistics does not have a metropolitan category in its classification, and there is none provided by most of the regional statistical institutes, either.

Traditionally, AACC have been jealous of their autonomy and have been suspicious of

the metropolitan bodies. This was especially true during the 1980s, when the corporaciones metropolitanas created during the dictatorship in Barcelona, Valencia, Bilbao and Madrid were abolished

sooner or later and replaced, in some cases, by sectorial agencies. The abolition

was decided by the new regional governments and was particularly polemic in Barcelona

and Valencia. Thirty years later, only in Barcelona is there a light version of a

metropolitan government, while the rest of urban agglomerations are governed by sectorial

agencies or directly by the regional governments (for further details on the Spanish

models of metropolitan governance, see Tomàs, Mariona. 2017. “Explaining Metropolitan Governance. The Case of Spain”, Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 3. Available at:

If we compare the different legislation of each autonomous community where the main urban agglomerations exist (Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Málaga, Sevilla, Bilbao) we find one main difference. The statutes of autonomy in three of them recognize the possibility of creating metropolitan areas by a regional law (article 93 in Catalonia, article 65 in Comunitat Valenciana, article 94 in Andalusia). However, in the statutes of autonomy of Madrid and the Basque Country there is no reference to the creation of metropolitan areas. These references are to be found on their respective legislation on local government: the law of 2003 in the case of Madrid (article 76) and the law of 2016 in the Basque Country (article 108). To sum up, the degree of institutionalization of metropolitan governance depends on the regional parliaments, and they have used this prerogative scarcely.

Question 32 mainly reveals the importance of the regional level in metropolitan affairs, leaving aside the concrete implementation of metropolitan governments (asked in question 29). Here, mayors were asked about the effectiveness of several modes of governance for the development of their agglomeration. Table 3 shows raw percentages for the whole sample[5]:

Table 3.

Percentages of mayors on effectiveness of modes of metropolitan governance

| Multi-purpose governance bodies for the urban agglomeration | Single-purpose authorities / special purpose districts | Inter-municipal contracts and cooperation | Support and regulations by upper-level governments | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| 1 Not effective at all | 12 | 7,5 | 27 | 17,1 | 3 | 1,9 | 10 | 6,2 |

| 2 | 23 | 14,3 | 29 | 18,4 | 3 | 1,9 | 13 | 8,0 |

| 3 | 62 | 38,5 | 78 | 49,4 | 45 | 27,8 | 60 | 37,0 |

| 4 | 58 | 36,0 | 21 | 13,3 | 67 | 41,4 | 61 | 37,7 |

| 5 Highly effective | 6 | 3,7 | 3 | 1,9 | 44 | 27,2 | 18 | 11,1 |

| Total N | 161 | 100,0 | 158 | 100,0 | 162 | 100,0 | 162 | 100,0 |

Source: European Mayor 2nd Round.

The majority of respondents considers the support and regulations by upper-level governments moderately effective (37,0 %) or quite effective (37,7 %) (values 3 and 4 out of 5), while 11 % of them considers it highly effective. Again, this is not surprising considering that regional governments are responsible for creating or abolishing both metropolitan areas and mechanisms for metropolitan cooperation. Mayors are more critical when asked about the effectiveness of creating multi-purpose governance bodies for urban agglomerations. Indeed, 7,5 % considers this not effective at all, while 14,3 % considers it not very effective; 38,5 % of the answers is located in the middle point and 36 % considers it effective. Only 3,7 % considers it highly effective. The solution of introducing single-purpose governance bodies (special districts) has less support. Indeed, almost half of the respondents (49,4 %) consider it moderately effective (value 3). The rest of the respondents tend to consider it not effective at all (17,1 %) and not effective (18,4 %). Only 13,3 % considers it effective and 1,9 % really effective.

Finally, mayors were asked about the effectiveness of inter-municipal contracts and cooperation, a solution that is very common in smaller urban agglomerations. In the last 30 years, the number of inter-municipal associations has grown: from 109 in 1986 to 996 associations in 2015 (according to the Register of Local Entities from the Ministry of Public Administration, 2015: 15). In this case, almost all the answers are situated between values 3 and 5, that is, 27,8 % of the respondents considers inter-municipal contracts and cooperation as moderately effective, 41,4 % as effective and 27,2 % as highly effective. In other words, the option of less institutionalized mechanisms of metropolitan governance are well evaluated by mayors.

HYPOTHESIS AND MAIN RECODIFICATIONS[up]

From the previous responses we have already drawn a picture that partly confirms some theoretical insights from the position of the municipalities within the Spanish multilevel governance system. These partial results seem to confirm a strong —and well perceived— regional centralism, a preference for intermunicipal cooperation rather than amalgamations for several important aspects, and also a preference for cooperative solutions to urban problems. These patterns are general and homogeneous, and no significant differences appear when comparing Autonomous Communities.

We know that the fundamental basis of the system is very strong, and does not allow for significant institutional differences. However, our theoretical argument considers that the foundational divide between fast-track and slow-track regions may still have an influence on mayors’ perceptions. Obviously, the argument is not strictly institutional, but rather attitudinal, since we are probably capturing the effect of the closeness and relative importance of historical regions in local elites’ minds. In this sense, we hypothesize that mayors in fast-track regions will be more prone to keep political power between them and the region. In other words, in fast-track regions, mayors will be more likely to safeguard their closest intergovernmental arenas, by preferring stronger regions and intermunicipal cooperation, rather than amalgamations or reductions in the power of regions.

This general hypothesis unfolds in several aspects that cannot be straightforwardly analyzed and pooled in a single statistical model, given the high number of issues involved. Instead, we propose to construct different models for every of the aforementioned reforms, and to draw a general picture of the difference between fast-track and slow-track regions. Therefore, our conclusions will be derived from the interpretation of all results taken together.

Our main independent variable will always refer to the division between ordinary regions and nationalities, and we always control for different individual and contextual factors, such as gender, age, education, hours devoted to mayoralty, political party (recoded), number of political parties in the municipality and population in 2014. Our main independent variable is created by clustering the Andalusian, Basques, Catalans and Galician mayors against the rest of Spain (“Slow-track Regions”, N=155; “Fast-track Regions”, N=148). Table 4 offers a description of the rest of the main independent variables used:

Table 4.

Independent variables: descriptive statistics

| Hours spent each week as a mayor | Age | Logged population 2014 | Number of municipal groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 279 | 277 | 303 | 303 |

| Missing | 24 | 26 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean | 65,738 | 46,31 | 10,2066 | 5,10 |

| Median | 60,000 | 46,00 | 9,9664 | 5,00 |

| Mode | 60,0 | 40 | 9,21a | 5 |

| St. Dev | 21,7691 | 8,991 | ,86214 | 1,226 |

| Minimum | 12,0 | 20 | 9,21 | 2 |

| Maximum | 168,0 | 73 | 13,41 | 9 |

| N | % | |||

| Gender | Female | 65 | 21,5 | |

| Male | 238 | 78,5 | ||

| N | % | |||

| Education | Elementary school | 4 | 1,4 | |

| Secondary school | 41 | 14,8 | ||

| University or equivalent | 232 | 83,8 | ||

| N | % | |||

| Political Party (recoded) | BNG | 3 | 1,0 | |

| C’s | 1 | ,3 | ||

| CCa-PNC | 9 | 3,0 | ||

| CIU | 21 | 6,9 | ||

| COMPROMIS | 12 | 4,0 | ||

| EH BILDU ERC-AM |

8 18 | 2,6 5,9 | ||

| IU / ICV | 12 | 4,0 | ||

| OTROS | 25 | 8,3 | ||

| PA | 3 | 1,0 | ||

| PNV-EAJ | 12 | 4,0 | ||

| PODEMOS Y ASIMILADOS | 7 | 2,3 | ||

| PP | 41 | 13,5 | ||

| PSOE | 131 | 43,2 |

Source: European Mayor 2nd Round.

Our dependent variables are the reforms that were presented in the previous section; however, we recode them to capture better the information they provide. We show some descriptive data of the recoded dependent variables, reordered by the fast-track and slow-track divide. Moreover, in order to deal with all the complexity of the questionnaire and its information, we have dichotomized all dependent variables contained in Q29 and Q32, to better capture the direction of the perceptions, in the same restrictive manner. We considered two values (out of five, from the Likert scales 1-5) as “desirable” and “effective”, clearly stating such options, and recoding the three remaining values as “non-desirable” and “not effective”. Concerning amalgamations and intermunicipal cooperation, we dichotomized the variables in order to keep in each option (mergers or IMC), those who consider more effective in tackling the concerned issue, against those that do not consider it more effective than the opposite option, or neither of them. Table 5 shows the data only for the “Desirable, “More Effective” and “Effective” options for each respondent belonging to the slow-track or fast-track setting:

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of all dependent variables by type of region

| Q29. Rescaling processes | Decentralization to municipalities | Decentralization to regions | Reduction of counties | Reduction of regions | Creation of metropolitan governments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast-track Regions | ||||||

| Desirable | N | 111 | 123 | 19 | 18 | 47 |

| % | 78,2 % | 87,2 % | 13,8 % | 12,9 % | 34,1 % | |

| Slow-track Regions | ||||||

| Desirable | N | 102 | 83 | 13 | 10 | 28 |

| % | 72,3 % | 59,3 % | 9,3 % | 7,1 % | 20,6 % | |

| Q32. Effectiveness of modes of governance | Regulations of upper-levels | Contracts and cooperation | Multipurpose governance | Single purposes or Special Districts | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast-track Regions | ||||||

| Effective | N | 47 | 67 | 37 | 9 | |

| % | 53,4 % | 77,0 % | 43,0 % | 10,7 % | ||

| Slow-track Regions | ||||||

| Effective | N | 32 | 44 | 27 | 15 | |

| % | 43,2 % | 58,7 % | 36,0 % | 20,3 % | ||

| Amalgamation (Q30) | Administrative staff | Service Quality | Cost saving | Political participation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast-track Regions | ||||||

| Is more effective | N | 18 | 16 | 38 | 12 | |

| % | 13,1 % | 11,8 % | 27,3 % | 8,8 % | ||

| Slow-track Regions | ||||||

| Is more effective | N | 12 | 27 | 52 | 12 | |

| % | 8,6 % | 19,4 % | 36,9 % | 8,6 % | ||

| Intermunicipal cooperation (Q30) | Administrative staff | Service Quality | Cost saving | Political participation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast-track Regions | ||||||

| Is more effective | N | 66 | 103 | 92 | 51 | |

| % | 48,2 % | 75,7 % | 66,2 % | 37,2 % | ||

| Slow-track Regions | ||||||

| Is more effective | N | 61 | 77 | 76 | 44 | |

| % | 43,6 % | 55,4 % | 53,9 % | 31,4 % | ||

Source: European Mayor 2nd Round.

Finally, to empirically test all these variables in multivariable models, we ran logistic regressions for each variable, with the same independent variables each, to obtain a complete picture of Spanish Mayors perceptions’, mediated by the fast-track and slow-track division.

THE PERSISTENT AND (STILL) OBSERVABLE EFFECT OF POLITICAL AND INSTITUTIONAL DIFFERENTIATION[up]

Before getting into multivariate analysis, the results displayed in table 5 shows the types of reforms where the fast-track and slow-track divide makes a difference. At first sight, we can observe some patterns of continuity from the whole sample, but there are also some interesting deviances.

In relation to the re-scaling strategies, both types of mayors’ perceptions are similar in almost every kind of reform, since all mayors consider the same reforms either desirable or undesirable. Both groups are in favor of decentralization for municipalities and regions, but substantive differences appear in the regionalization reform, where fast-track mayors’ perceptions are stronger (87,2 % versus 59,3 %), but their positions are similar with regard to municipalities (78,2 % versus 72,5 %). Both groups also take a homogeneous stance opposing the idea of reducing counties and regions. Again, both groups show minor differences regarding the creation of metropolitan governments. Even though it is largely non-desirable for both, 34 % of fast-track mayors consider it desirable, while only 20,6 % of “slow track” ones do it.

As for amalgamations and intermunicipal cooperation, there are no strong differences for the former. According to the raw numbers in section 3, Spanish mayors are widely and strongly against mergers in any form and for any purpose. Concerning IMC, a different pattern emerges, since both groups consider intermunicipal cooperation not to be more effective in dealing with administrative issues and increasing citizens’ political participation. However, when it comes to cost savings and service quality, the differentiation appears again. Mayors in fast-track regions are more prone to consider these reforms as “effective” (75,5 % versus 55,4 % for service quality and 66,2 % versus 53,9 % for cost savings).

Finally, concerning the effectiveness of the four different governance modes of metropolitan municipalities, results show great variation. For instance, regulations coming from upper levels of government are the sole exception where perceptions differ. Mayors in ordinary regions do not consider this governance option as effective (43,2 %), whereas mayors in fast-track regions consider this effective to a greater extent (53,4 %). Apart from this, mayors in fast-track regions consider the contracts and cooperation option to be better (77 % consider them effective, versus 58,7 %) and are less opposed to multipurpose bodies (43 % consider them effective, versus 36 %). The last option under examination, namely single purpose bodies, is strongly rejected by both groups, but with 20,3 % of the slow-track mayors considering them effective, and only 10,7 % of fast-track mayors.

The picture emerging from these results accounts for somehow divergent profiles. As mayors’ perceptions are substantially equal in all senses, slight differences appear, the main ones concerning the strength of the preferences. As we have already indicated, it seems that mayors in fast-track regions are more prone to reinforce regions and are less against the creation of metropolitan regions. Moreover and to a larger extent, they consider intermunicipal cooperation, as more effective for cost savings and service quality. Similarly, they see the reforms based on contracts and cooperation much more positively than their counterparts in slow-track regions. Thus, in general terms, this picture seems to corroborate the fact that differences in mayors’ perceptions can be explained by their belonging to one or another group.

In any case, to what extent are the slight differences we have considered significantly different in a multivariate environment? Are those small differences systematic, or due to chance? A complete set of logistic regressions is carried out to finally assess the robustness of the results we have just shown. In order to increase the reliability of our results, we ran the regressions with the same set of independent variables; thus, the only variation affects the dependent variable. Indeed, for reasons of space and clarity of the interpretations, we offer here only a summary table of our findings. Table 6 includes only the independent variable that is significant, together with coefficien t β, of selected variables.

Table 6.

Resumed logistic models on reforms

| Fast-track regions | Population 2014 (log) | Age | Secondary education | University education | Male | Hours devoted | N political groups | Political party | Constant | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q29 Rescaling |

Decentralization to municipalities | 0.415 | -0.017 | 0.014 | -0.820 | -0.270 | -0.096 | -0.002 | 0.106 | Yes | 16.558 | 251 |

| Decentralization to regions | 1.436[***] | -0.299 | 0.020 | 0.576 | 1.202 | -0.674 | -0.0002 | 0.428[***] | Yes | -0.040 | 250 | |

| Reduction of counties | 0.285 | -0.336 | -0.004 | -1.306 | -1.297 | 0.779 | -0.020 | -0.080 | Yes | 5.699 | 247 | |

| Reduction of regions | 0.490 | -0.457 | 0.013 | 17.099 | 16.802 | 2.382[**] | 0.003 | -0.039 | Yes | -34.467 | 248 | |

| Creation of metropolitan | 0.884[**] | 0.170 | 0.001 | -1.081 | -0.337 | -0.050 | -0.013 | 0.161 | Yes | -2.953 | 244 | |

| Q30 Amalgamation |

Administrative staff | 0.678 | -0.373 | 0.030 | 16.930 | 17.139 | 0.571 | -0.002 | -0.279 | Yes | -34.656 | 248 |

| Service Quality | -0.798[**] | -0.106 | 0.022 | 15.064 | 15.250 | 0.053 | 0.003 | -0.277[*] | Yes | -15.364 | 247 | |

| Cost saving | -0.340 | 0.257 | 0.002 | -0.275 | -0.851 | -0.021 | -0.003 | -0.239[*] | Yes | -1.153 | 251 | |

| Political participation | 0.318 | 0.139 | 0.026 | 15.922 | 16.310 | 1.119 | -0.023 | 0.167 | Yes | -39.717 | 249 | |

| Q30 IMC |

Administrative staff | -0.044 | 0.102 | 0.020 | 0.883 | 1.616 | 0.091 | 0.010 | 0.020 | Yes | -5.043[**] | 248 |

| Service Quality | 0.877[**] | -0.026 | 0.006 | -0.411 | -0.534 | -0.049 | -0.003 | 0.159 | Yes | -0.199 | 247 | |

| Cost saving | 0.632[**] | -0.191 | 0.022 | 1.468 | 1.814 | 0.239 | 0.004 | 0.189 | Yes | -2.352 | 251 | |

| Political participation | 0.183 | -0.265 | 0.009 | 0.692 | 0.824 | -0.014 | 0.014[**] | -0.012 | Yes | -17.084 | 249 | |

| Q32 Modes of governance |

Regulations of upper-levels | 0.602 | 0.287 | -0.067[***] | 15.396 | 15.872 | -0.588 | 0.008 | 0.059 | Yes | -32.202 | 146 |

| Multipurpose governance | 0.835[*] | -0.174 | -0.034 | -0.804 | -0.905 | -0.193 | 0.021[*] | 0.552[***] | Yes | -16.241 | 145 | |

| Single purpose bodies | 0.202 | -0.090 | -0.075[*] | 14.689 | 14.179 | -0.558 | 0.039[***] | 0.196 | Yes | -31.128 | 143 | |

| Contracts and cooperation | 1.698[***] | -0.113 | -0.010 | -1.499 | -0.986 | -0.190 | -0.004 | 0.543[**] | Yes | -1.105 | 146 | |

The models show interesting results, partially confirming our hypothesis. First, even when controlling for seven relevant independent variables accounting for individual traits, context and political elements, it appears quite clearly that the most discriminant variable of all those considered is our variable of interest —the divide between fast-track and slow-track regions. This independent variable is significant, to different degrees, in 7 out of 17 models. Secondly, the direction of the relations between it and our dependent variables in every model, when significant, is in line with the theoretical expectations and the current political mood. Thirdly, the resulting picture configures a slightly identifiable profile of mayors based on their belonging to one or another institutional setting.

We built our hypothesis under the assumption of high homogeneity of perceptions, but with identifiable specificities derived both from the institutional setting and the perceptions of the elites from the devolved Spain. In fact, the picture emerging from the analysis of all models shows no significant differences in the willingness to reduce the current multi-tier institutional system (reduce regions and counties), and also a wide homogeneity in desiring decentralization towards local units, and considering amalgamations as a bad solution in general terms. Therefore, slight differences appear between our two groups of interest.

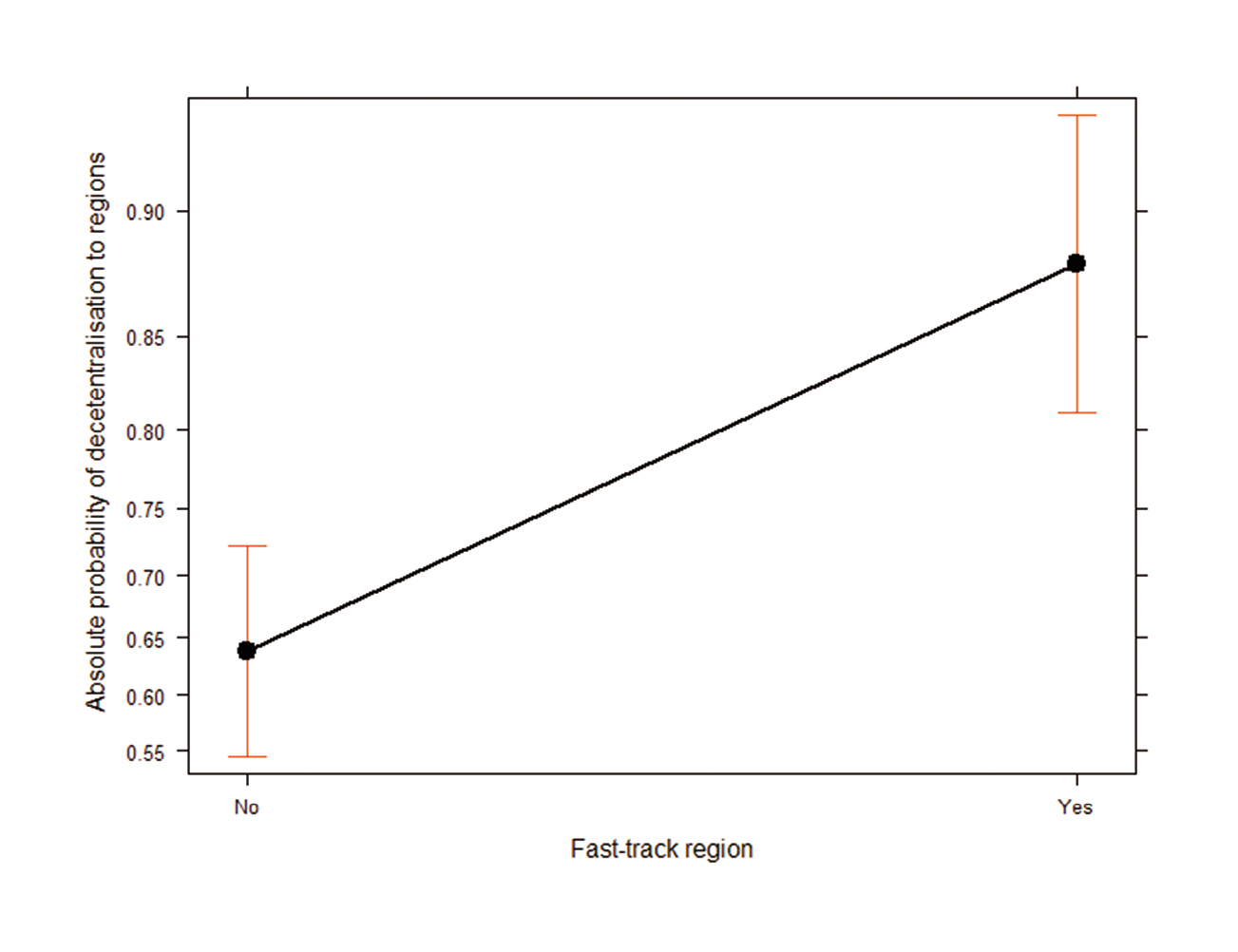

As expected, the perceptions of mayors from fast-track regions seem to configure a homogeneous pattern of protecting their main intergovernmental arenas and institutional counterparts. These mayors prefer, to a larger and significant extent, decentralization to regions (Q29), placing the autonomous community not only as the legal-political center, but also as a confident player in the intertwined game of intergovernmental relations. This is the strongest effect of all, as figure 1 shows in absolute probabilities:

Moreover, the significant and relevant coefficients on considering effective contracts and cooperation (Q32), analyzed together with a consideration of IMC solutions to be more effective with regard to quality of services and cost efficiency, show a clear and robust preference for generating intergovernmental spaces where they can control —or at least, be aware of— policy-making that affects them.

CONCLUSIONS[up]

In this paper, we have assessed mayors’ perceptions of three issues: re-scaling reforms, mergers and metropolitan governance. An analysis of the complete sample shows a higher homogeneity in responses and relevant continuities, regardless whether mayors belong to fast-track or slow-track regions. This homogeneity of local elites’ perceptions is not surprising, but it is rather to be expected, since the institutional environment of local government units is rather similar across the territory, due to the existence of statewide basic laws.

In fact, through the process of decentralization of the state, each autonomous community has become the key institution concerning local government management. In other words, besides basic regulation coming from the state, autonomous communities are the key actors to determine local governments’ day-to-day functioning. Our expectations are that this institutional link between local and regional units might have an impact on local elites’ perceptions of local government reforms. Therefore, to understand these perceptions it is necessary to consider the process of political decentralization that occurred since the end of the 1970s.

The main results show that, generally speaking, Spanish mayors are in favor of strengthening decentralization towards municipalities and regions, and therefore, similar majorities are against the reduction of counties and regions. Most mayors’ positions are less clear when considering the creation of metropolitan governments. Moreover, a vast majority of mayors is against mergers and amalgamations, while mayors are slightly more favorable to intermunicipal cooperation as a preferred way to overcome municipal fragmentation. Finally, the processes of metropolitanization are perceived as not particularly adequate for the main local governments’ governance challenges.

However, our results show identifiable specificities in mayors’ perceptions derived from the institutional setting and the perception of elites from the decentralized Spain. Although there are no significant differences in the willingness to reduce regions and municipalities or the desire for more decentralization towards local units, slight differences appear between mayors belonging to fast-track regions and slow-track ones.

Indeed, mayors from fast-track regions are prone to protect their main intergovernmental arenas and institutional counterparts. These mayors advocate for higher decentralization to the autonomous community, which emerges as a key actor in the intertwined game of intergovernmental relations. To sum up, in this paper we show that mayors’ perceptions are influenced by intergovernmental relationships and especially by the asymmetric process of decentralization that has unfolded over the last forty years.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS[up]

This work has benefited from the funds of the LoGoRef project: “Una nueva arquitectura local: eficiencia, dimensión y democracia” (CSO2013-48641-C2-2-R, MCOC, Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad), and the Catalan Government through AGAUR, 2014-SGR-838. We are also grateful for the comments made to the paper by two anonymous reviewers, together with the comments made by our colleagues from the LoGoRef project.

Notes[up]

| [1] |

Year of the approval of the Ley 7/1985, de 2 de abril, Reguladora de las Bases del Régimen Local (LBRL). |

| [2] |

The previous art. 28 of LBRL allowed municipalities to act in whatever matter if a ‘local interest’ was at stake. |

| [3] |

Ley 57/2003, de 16 de diciembre, de Medidas para la Modernización del Gobierno Local. |

| [4] |

Ley 22/2006, de 4 de julio, de Capitalidad y de Régimen Especial de Madrid and Ley 1/2006, de 13 de marzo, por la que se regula el Régimen Especial del Municipio de Barcelona. |

| [5] |

We have to notice here that only those municipalities part of a large urban agglomeration were allowed to respond to this question; therefore, our total N for these questions is 184. |

References[up]

|

Agranoff, Robert and Juan A. Ramos-Gallarín. 1997. “Toward Federal Democracy in Spain: An Examination of Intergovernmental Relations”, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 27 (4): 1-38. |

|

|

Agranoff, Robert. 2007. “Local governments in Spain’s multilevel arrangements”, in H. Lazar y C. Leuprecht (eds.), Spheres of governance. Québec: McGill-Queen’s University Press. |

|

|

Agranoff, Robert. 2010. Local governments and their intergovernmental networks in federalizing Spain. Québec: McGill-Queen’s University Press. |

|

|

Aja, Eliseo and César Colino. 2014. “Multilevel structures, coordination and partisan politics in Spanish intergovernmental relations”, Comparative European Politics, 12 (4-5): 444-467. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2014.9. |

|

|

Aja, Eliseo. 2014. Estado autonómico y reforma federal. Barcelona: Alianza. |

|

|

Alba, Carlos and Carmen Navarro. 2005. “Metropolitan Areas in Spain, a diverse and unknown reality”, in V. Hoffmann-Martinot y J. Sellers (eds.), Metropolitanization and Political Change, Wiesbaden: Springer. |

|

|

Amat, Francesc, Ignacio Jurado and Sandra León. 2009. A political theory of decentralization dynamics. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ciencias Sociales. |

|

|

Amat, Francesc. 2012. Identidad y cambio institucional: Los efectos de la competición política. Madrid: Fundación Alternativas. |

|

|

Arbós, Xavier, César Colino, María Jesús García Morales and Salvador Parrado. 2009. Las relaciones intergubernamentales en el Estado autonómico: la posición de los actores. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Autònomics. |

|

|

Bel, Germà and Antonio Miralles. 2003. Factors influencing privatization of urban solid waste collection in Spain. Urban Studies, 40: 1323-1334. |

|

|

Bertrana, Xavier and Hubert Heinelt. 2013. “The Second Tier of Local Government in the Context of European Multi-level Government Systems: Institutional Settings and Prospects for Reform”, Revista Catalana de Dret Públic, 46: 73-89. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2436/20.8030.01.4. |

|

|

Calonge Velázquez, Antonio. 2015. “La fusión de municipios, único instrumento de la Ley 27/2013, de 27 de diciembre, de racionalización y sostenibilidad de la Administración Local para la modificación de la planta municipal: una oportunidad perdida”, Revista de Estudios de la Administración Local y Autonómica, núm. extraordinario. |

|

|

Christoffersen, Henrick, Martin Paldam and Allan Wurtz. 2007. Public versus private production and economies of scale, Public Choice, 130 (3): 311-328. |

|

|

Galán Alfredo. 2012. La reordenación de las competencias locales: duplicidad de Administraciones y competencias impropias. Barcelona: Fundación Democracia y Gobierno Local. |

|

|

Galán, Alfredo and Ricard Gracia Retortillo. 2011. “Estatuto de autonomía de Cataluña, gobiernos locales y Tribunal Constitucional”, Revista d’Estudis Autonòmics i Federals, 12: 237-301. |

|

|

Galán, Alfredo. 2015. “La aplicación autonómica de la Ley de Racionalización y Sostenibilidad de la Administración Local”, Revista de Estudios de La Administración Local y Autonómica, núm. extraordinario. |

|

|

Haus, Michael and David Sweeting. 2006. “Mayors, Citizens and Local Democracy”, en Annick Magnier and Henry Bäck (eds.), The European mayor: political leaders in the changing context of local democracy. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. |

|

|

Heinelt, Hubert and Daniel Kübler. 2005. Metropolitan Governance. Capacity, democracy and the dynamics of place. ECPR Studies in European Political Science. London and New York: Routledge. |

|

|

Heinelt, Hubert and Karsten Zimmermann. 2011. “How Can We Explain Diversity in Metropolitan Governance within a Country? Some Reflections on Recent Developments in Germany”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35 (6): 1175-1192. |

|

|

Heinelt, Hubert and Nikos Hlepas. 2006. “Typologies of Local Government Systems”, en Annick Magnier and Henry Bäck (eds.), The European mayor: political leaders in the changing context of local democracy. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. |

|

|

Jiménez Asensio, Rafael. 2014. Vademècum sobre la Llei de Racionalització i sostenibilitat de l’Administració Local. 100 qüestions sobre la seva aplicació. Barcelona: Federació de Municipis de Catalunya. |

|

|

John, Peter. 2001. Local governance in Western Europe. London: Sage. |

|

|

Keil, Roger, Julie-Anne Boudreau, Pierre Hamel and Stephen Kipfer, S. (eds.) 2016. Governing Cities Through Regions: Transatlantic Perspectives. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier Press. |

|

|

Lago-Peñas, Santiago and Ignacio Lago-Peñas. 2013. “La atribución de responsabilidades políticas en Estados descentralizados”, Cuadernos Económicos de ICE, 85: 43-64. |

|

|

León, Sandra and Mónica Ferrín Pereira. 2007. “La atribución de responsabilidades sobre las políticas públicas en un sistema de gobierno multinivel”, Administración y Cidadanía, 2 (1): 49-75. |

|

|

León, Sandra and Mónica Ferrín Pereira. 2011. “Intergovernmental Cooperation in a Decentralised System: the Sectoral Conferences in Spain”, South European Society and Politics, 16 (4): 1-20. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2011.602849. |

|

|

León, Sandra. 2011. “Who is responsible for what? Clarity of responsibilities in multilevel states: The case of Spain”, European Journal of Political Research, 50 (1): 80-109. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01921.x. |

|

|

Liñeira, Robert. 2014. El Estado de las autonomías en la opinión pública: preferencias, conocimiento y voto. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. |

|

|

Linz, Juan José. 1973. “Early State-building and Late Peripheral Nationalism Against the State: The Case of Spain”, in Eisendstad and Rokkan (eds.), Building States and Nations. London: Sage. |

|

|

Linz, Juan José. 1985. “De la crisis de un Estado unitario al Estado de las autonomías”, in Fernández Rodríguez (ed.), La España de las Autonomías. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios de Administración Local. |

|

|

Magre, Jaume and Esther Pano. 2012. “La reobertura del debat sobre la fusió municipal: buscant la resposta a algunes preguntes”, Anuari Polític, 2011: 153-159. |

|

|

Magre, Jaume and Esther Pano. 2016. “Deliver of Municipal Services in Spain: An Uncertain Picture”, in Wollman, Kopric and Marcou (eds.), Public and Social Services in Europe. From Public and Municipal to Private Sector Provision. London: Palgrave MacMillan. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-57499-2. |

|

|

Magre, Jaume and Xavier Bertrana. 2005. “Municipal presidentialism and democratic consolidation in Spain”, in Berg and Rao (eds.), Transforming local political leadership. Basingstocke: Palgrave McMillan. |

|

|

Medir, Lluís, Esther Pano, Alba Viñas and Jaume Magre. 2017. “Dealing with Austerity: a case of local resilience in Southern Europe”, Local Government Studies, 43 (4): 621-644. Available at: http://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1310101. |

|

|

Molas, Isidre and Oriol Bartomeus. 1998. Estructura de la competència política a Catalunya. Barcelona: ICPS. |

|

|

OECD. 2015. Governing the City. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264226500-en |

|

|

Page, Edward and Michael Goldsmith. 1987. Central and local government relations :a comparative analysis of West European unitary states. London: Sage. |

|

|

Pallarés, Francesc and Michael Keating. 2003. “Multi-Level Electoral Competition”, European Urban and Regional Studies, 10 (3): 239-255. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764030103005. |

|

|

Riera, Pedro. 2012. “La abstención diferencial en la España de las autonomías. Pautas significativas y mecanismos explicativos”, Revista Internacional de Sociología, 70 (3): 615-642. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3989/ris.2010.10.07. |

|

|

Riera, Pedro. 2013. “Voting differently across electoral arenas: Empirical implications from a decentralized democracy”, International Political Science Review, 34 (5): 561-581. |

|

|

Rodríguez Álvarez, José María. 2011. “El gobierno local en España desde mediados del siglo XX: continuidades y cambios”, in Arenilla (ed.), La administración pública entre dos siglos: ciencia de la administración, ciencia política y derecho administrativo: Homenaje a Mariano Baena del Alcázar. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Administración Pública. |

|

|

Savitch, Hank and Robert Vogel. 2009. “Regionalism and Urban Politics”, in Jonathan S. Davies and David L. Imbroscio (eds.), Theories of urban politics. London: Sage. |

|

|

Tomàs, Mariona. 2012. “Exploring the metropolitan trap: the case of Montreal”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 36: 554-567. |

|

|

Tomàs, Mariona. 2017. “Explaining Metropolitan Governance. The Case of Spain”, Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 3. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13147-016-0445-0. |

|

|

Velasco Caballero, Francisco. 2014. “El nuevo régimen local general y su aplicación diferenciada en las distintas comunidades autónomas”, Revista Catalana de Dret Públic, 48: 1-23. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2436/20.8030.01.18. |

|

|

Wolman, Harold and Michael Goldsmith. 1992. “The study of urban politics and policy”, in Wolman and Goldsmith (eds.), Urban politics and policy: a comparative approach. |

Biography[up]

| [a] |

Assistant professor in Political Science in the Political Science section of the Faculty

of Law of the University of Barcelona and a member of GREL (www.ub.edu/grel). His areas of interest are local public policies, local institutional design and intergovernmental

relations of local governments. He has coordinated the data collection of the European

Major project for Spain, from which the data of this monographic section come from. |

| [b] |

Lecturer in Political Science at the Department of Political Science, Constitutional

Law and Philosophy of Law of the University of Barcelona (UB). He is the Principal

Investigator of the GREL (www.ub.edu/grel) and director of the Fundació Carles Pi i Sunyer (www.pisunyer.org). His research interests are focused on local institutions, territorial governance

and democracy. |

| [c] |

Associate Serra Húnter Professor of Political Science at the University of Barcelona

(UB) and member of the Research Group in Local Studies (GREL). Her research focuses

on metropolitan governance, urban policies and local government. She has published

in journals such as the International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Urban

Studies or the Journal of Urban Affairs. She has been a researcher at the National

Institute of Scientific Research of Quebec (INRS) and post-doctoral candidate at the

University of Montreal. |