Exogenous and endogenous determinants of Spanish mayors’ notions of democracy:

A multilevel regression analysis

Determinantes exógenos y endógenos de las nociones sobre democracia de los alcaldes

españoles:

un análisis de regresión multinivel

ABSTRACT

A common ground in the literature on elite’s notions of democracy is (1) that leaders’ notions of democracy can be successfully captured by a representative-participatory dimension, and (2) that the way leaders view democracy is paramount to understand their behavior. Taking on an institutional perspective, the most common model combines an endogenous and exogenous origin of leaders’ notions of democracy. The theory assumes that both local institutional arrangements and personal characteristics may have an impact on the way local leaders perceive democracy and behave. However, while some evidence has been found to support the exogenous aspect of this theory (leaders’ ideology influence their notions of democracy), the impact of local institutional arrangements on leaders’ notions of democracy has received more limited empirical support. In this paper we provide a model of endogenous and exogenous factors on local elite’s notions of democracy. In particular, we show that local leaders’ political experience endogenizes the effect of ideology on their notions of democracy and on their support to democratic reforms. We test our model using survey data from a sample of mayors in Spanish municipalities and find empirical support for our model. One of our main findings is that the effect of ideology on mayors’ support for particular views of democracy decreases with political experience.

Keywords: notions of democracy, mayors, elite, ideology, career.

RESUMEN

Existe acuerdo en la literatura sobre las nociones de democracia sostenidas por la elite acerca de (1) que las nociones de democracia pueden ser representadas adecuadamente mediante una dimensión representativa-participativa, y (2) que el modo en que los líderes conciben la democracia es relevante para comprender su comportamiento. Desde una perspectiva institucionalista, el modelo más común combina el origen endógeno y exógeno de las nociones de democracia de los líderes políticos. La teoría asume que tanto los aspectos institucionales como las características individuales tienen un impacto sobre la manera en que los líderes perciben la democracia y actúan. Sin embargo, aunque existe evidencia para apoyar el aspecto exógeno de esta teoría (la ideología de los líderes influye en su visión sobre la democracia), el impacto del diseño institucional local sobre las nociones de democracia ha recibido menor apoyo empírico. En este trabajo se proporciona un modelo de factores endógenos y exógenos de las nociones de democracia la elite política municipal. En particular, mostramos que la experiencia política endogeniza el efecto de la ideología sobre las nociones de democracia y el apoyo a reformas institucionales democráticas. Ponemos a prueba nuestro modelo mediante datos de encuesta sobre una muestra de alcaldes de municipios españoles y encontramos apoyo empírico para el mismo. Uno de los principales hallazgos es que el efecto de la ideología sobre el apoyo de los alcaldes a ciertas visiones concretas de la democracia decrece con la experiencia política.

Palabras clave: nociones de democracia, alcaldes, élites, ideología, carrera.

INTRODUCTION[up]

Although the study of local leaders’ notions of democracy has a notorious tradition

( Tarrow, Sidney. 1977. Between Center and Periphery: Grassroots politicians in Italy and France. New Haven: Yale University Press.Tarrow, 1977), the growing availability of data ( Bäck, Henry. 2006. “Does recruitment matter? Selecting path and role definition”,

in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier (eds.), The Eurpean Mayor. Political Leaders in the Changing Context of Local Democracy (pp. 123-150). Heidelberg: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. Available at:

The nature of these new datasets has enabled both the testing of old theories ( Sharpe, Laurence J. 1970. “Theories and values of local government”, Political Studies, 18 (2): 153-174. Available at:

Previous studies, then, have taken on an institutionalist perspective. Based on the

theory that different types of local government explain differences in styles of local

leadership ( Haus, Michael and David Sweeting. 2006a. “Local democracy and political leadership:

Drawing a map”, Political Studies, 54: 267-288. Available at:

In this paper we argue that leaders’ notions of democracy have both an exogenous and endogenous origin. In particular, keeping the exogenous origin of leaders’ notions as in the classic theory, we argue that the variation in leaders’ notions of democracy is also highly dependent on leaders’ political experience, which the old theory does not take into account. In addition, we further argue that, over time, political experience completely endogenizes leaders’ notions of democracy, to the point that exogenous factors such as ideology no longer matter. Using data from political leaders in Spain, we offer empirical support for this model.

Section 2 offers an overview of how local leaders’ notions of democracy have been approached in the new comparative perspective in the field. It discusses the main results regarding the endogenous and exogenous models of the origins of leaders’ notions of democracy. Next, in Section 3 we outline our main theoretical argument presenting our exogenous and endogenous model of notions of democracy. In particular, we discuss the role of political experience in endogenizing local leaders’ notions of democracy. We also outline our hypotheses. The data used to test the hypotheses are presented in Section 4, and the results are presented and discussed in Section 5; followed by some concluding remarks in section 6.

MAYORS’ NOTIONS OF DEMOCRACY[up]

Local leaders’ notions of democracy are understood to play a central role in the way

they perceive their own role and behavior. In very broad terms, notions of democracy

are understood to come in two different kinds: representative democracy and participative

one ( Haus, Michael and David Sweeting. 2006b. “Mayors, citizens and local democracy” en

Henry Bäck, Henry, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier (eds.), The European Mayor: Political Leaders in the Changing Context of Local Democracy (pp. 151-176). Heidelberg: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. Available at:

In contrast, the participatory notion of democracy views the “accountability” model

as too “thin” ( Barber, Benjamin. 2003. Strong Democracy: Participatory Politics for a New Age. Berkeley: University of California Press.Barber, 2003) as it undermines direct self-government by citizens. If citizens should govern themselves,

elections are not to be seen merely as a mechanism to select representatives but as

one to select policy programs that must be implemented by elected representatives. This way, elections set up a mandate that

governments should implement ( Manin, Bernard, Adam Przeworski and Susan C. Stokes. 1999. “Elections and representation”,

en Adam Przeworski, Susan C. Stokes and Bernard Manin (eds.), Democracy, Accountability, and Representation (pp. 29-54). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at:

According to this theoretical framework, institutional arrangements and personal characteristics can influence the way mayors view local democracy which, in turn, affects the way local leaders perceive how they should behave and how local government should be reformed. This model, then, has triggered two main sets of questions in studies of local leaders. On the one hand, questions related to the extent to which institutional arrangements determine distinct notions of democracy among local political leaders. On the other hand, whether distinct views of local democracy explain behavior or attitudes toward reforms of local government that touch on key aspects of the functioning of democracy.

Heinelt ( Heinelt, Hubert. 2013a. “Councillors’ notions of democracy, and their role perception

and behaviour in the changing context of local democracy”, Local Government Studies, 39 (5): 640-660. Available at:

This view of the role of institutions has favored studies that try to identify instances

of different “adjustments” of notions of democracy to various institutional frameworks.

For instance, Haus and Sweeting ( Haus, Michael and David Sweeting. 2006a. “Local democracy and political leadership:

Drawing a map”, Political Studies, 54: 267-288. Available at:

Nevertheless, the lack of effect of institutions constitutes an important challenge

to the endogenous theory of notions of democracy. First, this strand of research has

assumed that notions of democracy should be endogenous to particular types of institutional

frameworks, but empirical evidence has given little support to this. Second, there

is stronger evidence that local leaders’ notions of democracy depend on their political

orientations, especially ideology. For instance, using a typical left-right scale

for self-placement of European local councilors, Heinelt ( Heinelt, Hubert. 2013a. “Councillors’ notions of democracy, and their role perception

and behaviour in the changing context of local democracy”, Local Government Studies, 39 (5): 640-660. Available at:

Very little attention, however, has been devoted to explaining whether leaders’ notions

of democracy can change due to their repeated interaction within their institutional

environment, although the causes and consequences of local career paths and recruitment

have been thoroughly studied ( Bledsoe, Thimoty. 1993. Careers in City Politics. The Case for Urban Democracy. Pittsburgh and London: University of Pittsburgh Press,.Bledsoe, 1993; Eldersveld, Samuel J., Lars Strömberg and Wim Derksen. 1995. Local Elites in Western Democracies: A Comparative Analysis of Urban Political Leaders

in the U.S., Sweden, and the Netherlands. Boulder: Westview Press.Eldersveld et al., 1995; Bäck, Henry. 2006. “Does recruitment matter? Selecting path and role definition”,

in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier (eds.), The Eurpean Mayor. Political Leaders in the Changing Context of Local Democracy (pp. 123-150). Heidelberg: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. Available at:

THEORETICAL ARGUMENT[up]

Our argument is that local leaders’ notions of democracy are both exogenous and endogenous. On the one hand, it is quite safe to assume that political orientations or ideology provide local leaders (and the rest of us) with general principles that shape opinions regarding how democracy should work. For instance, it is political orientations that give local representatives a set of notions of democracy at the outset of their political career, when they have no prior experience as representatives. On the other hand, it is also reasonable to think that leaders’ ongoing career as political representatives —i.e., within one or several institutional frameworks— offers them incentives to adjust their notions of democracy according to their experience. In the end, what we understand as notions of democracy (a set of notions regarding how democracy should work) should be influenced precisely by our experience with democracy, because “politicians also bring with them a heritage from their political lives” ( Kœr, Ulrik. 2006. “The mayor’s political career”, en Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier (eds.), The European Mayor. Political Leaders in the Changing Context of Local Democracy (pp. 75-98). Heidelberg. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Kœr, 2006: 76). This way, since “the route to the mayoral office affects the mayor’s course of action once elected” (id.), local leaders’ notions of democracy may be independent of particular institutional frameworks but endogenous to the accumulation of interactions within institutions. By the same logic, political experience might also influence local leaders’ support for institutional reforms that deal with how democracy works —i.e., reforms that would change their roles as representatives giving either them or citizens more decision capacity in local democracy. Political experience, then, endogenizes local representatives’ notions of democracy.

Our first hypothesis (H1) tests the exogenous theory of notions of democracy, and we expect to find —like

Heinelt ( Heinelt, Hubert. 2013a. “Councillors’ notions of democracy, and their role perception

and behaviour in the changing context of local democracy”, Local Government Studies, 39 (5): 640-660. Available at:

DATA AND METHOD[up]

We test our hypotheses using data from the second round of the “Political Leaders

in European Cities” survey, which aims at studying the role of mayors and the transformation

of political representation at the local level in several European countries. We use

a subset of these data corresponding to mayors from Spain for two main reasons. First,

to our knowledge, there has been no published empirical work on the notions of democracy

of Spanish mayors so far, and this paper intends to fill this gap. Second, our intent

is not to test the role of different institutional designs in shaping mayors’ notions

of democracy, but to look at the mechanisms at work within institutions. The Spanish

local political system presents no regional differences and is based on a model of

representative, parliamentary democracy where the local assembly of elected councilors

elects the mayor. Once indirectly elected, mayor leadership is “strong” ( Page, Edward and Michael Goldsmith. 1987. Central and Local Government Relation. Beverly Hills: SAGE.Page and Goldsmith, 1987; Page, Edward. 1991. Localism and centralism in Europe. Oxfors: Oxford University Press. Available at:

The survey took responses form mayors elected in municipalities larger than 10,000 inhabitants. The original sample size was 752 mayors (all municipalities beyond that population threshold), and the actual responses amounted to 303, which yields a response rate of 40 %. Despite the response rate, the final sample is rather representative of the universe both in terms of territorial distribution and gender (see table 1) and, therefore, we do not expect the results to be biased due to unbalanced response rate.

Table 1.

Territorial and gender distribution of respondents (percentages) across regions throughout Spain

| Universe | Sample | |

|---|---|---|

| Region | ||

| Andalucía | 20.48 | 14.65 |

| Aragón | 1.73 | 1.83 |

| Balears, Illes | 3.06 | 4.03 |

| Canarias | 5.59 | 5.86 |

| Cantabria | 1.33 | 1.10 |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 5.32 | 2.93 |

| Castilla y León | 3.19 | 1.83 |

| Catalunya | 15.96 | 23.81 |

| Ceuta | 0.13 | 0.00 |

| Comunidad de Madrid | 6.52 | 6.96 |

| Comunitat Valenciana | 13.16 | 14.29 |

| Extremadura | 1.86 | 1.47 |

| Galicia | 7.45 | 5.13 |

| La Rioja | 0.53 | 0.73 |

| Melilla | 0.13 | 0.00 |

| Navarra | 1.33 | 2.93 |

| País Vasco | 5.45 | 6.23 |

| Principado de Asturias | 2.79 | 1.83 |

| Región de Murcia | 3.99 | 4.40 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 23.01 | 21.61 |

| Male | 76.99 | 78.39 |

In order to test our hypotheses, we fit multilevel linear regression models of mayors’ notions of democracy and support to democratic reforms on ideology and political experience as main independent variables. Multilevel models (ML) can better deal with unbalanced samples at the second level ( Gelman, Andrew and Jeniifer Hill. 2007. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.Gelman and Hill, 2007). In a nutshell, in ML models region-level intercepts are given a probability distribution, which puts them in relation to the average intercept and, therefore, region-level estimates are less biased than, say, pooled or standard fixed-effects models. With ML, we thus get an actual intercept which is the average cross-region estimate. We could also can get J separate intercepts, one for each region, relative to the model intercept. Given the modeling of each region’s intercept, ML models deal much better with regions with fewer observations, and therefore the model takes regional variation into account.

Our two main dependent variables are mayors’ notions of democracy and their support to institutional reforms. Mayors’ notions of democracy are measured through their responses to a question that asks about their level of agreement (on a five-point scale) to a number of statements, which can be read table 2. Mayors’ level of support for democratic reforms is measured through another question where mayors were asked how desirable or undesirable (in a five-point scale) they considered a number of institutional reforms, regardless of whether these reforms had actually been implemented in their municipalities or not (see table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistical information of the main variables

| N | Mean | St. Dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||||

| Notions of democracy | |||||

| Political parties are the most suitable arena for citizen participation | 284 | 3.183 | 0.895 | 1 | 5 |

| Residents should participate actively and directly in making important local decisions | 286 | 4.213 | 0.730 | 2 | 5 |

| Residents should have the opportunity to make their views known before important local decisions are made by elected representatives | 282 | 4.167 | 0.618 | 2 | 5 |

| Apart from voting, citizens should not be given the opportunity to influence local government policies | 283 | 2.155 | 1.129 | 1 | 5 |

| Council decisions should reflect a majority opinion among the residents | 282 | 3.993 | 0.706 | 1 | 5 |

| Political representatives should make what they think are the right decisions, independent of the current views of local people | 283 | 3.254 | 1.007 | 1 | 5 |

| The results of local elections should be the most important factor in determining local government policies | 285 | 3.579 | 0.899 | 1 | 5 |

| Decentralization within local government is necessary to involve citizens in public affairs | 284 | 3.475 | 0.781 | 1 | 5 |

| Support for democratic reforms | |||||

| A decisive (binding) referendum | 277 | 3.477 | 0.984 | 1 | 5 |

| Direct election of the mayor | 278 | 3.558 | 1.021 | 1 | 5 |

| Non-binding referenda | 275 | 3.360 | 0.874 | 1 | 5 |

| Participatory Budgeting | 281 | 4.046 | 0.838 | 1 | 5 |

| Reduction of the number of councilors | 279 | 2.326 | 0.924 | 1 | 5 |

| Independent variables | |||||

| Political experience (years since first elected position) | 252 | 12.444 | 8.485 | 1 | 37 |

| Ideology (Left-Right) | 278 | 3.392 | 1.953 | 0 | 10 |

| Municipal size | 303 | 44,897.9 | 69,753.9 | 10,002 | 666,058 |

| Age | 277 | 46.31 | 8.99 | 20 | 73 |

Our main independent variables are ideology and the mayors’ political experience. Regarding the former, it is measured through a classic 11-point self-placement scale where 0 means extreme left and 10 extreme right ideology. The average ideological position leans toward the left (3.39) with a standard deviation of 1.9. Regarding political experience, the questionnaire asked mayors the year when they were first appointed to an elected position, regardless of whether this position was at the local or any other level of representation. From this variable, we calculated the number of years current mayors have been serving as representatives of any kind. Given that municipal elections had been held on May 2015 and the survey was responded between September 2015 and February 2016, respondents whose position as mayor was their first experience as elected representatives were counted as having 1 year of experience. The average mayor in the sample had had a bit more than 12 years of political experience, but there is notable variation among the respondents (a standard deviation of 8.5 years), with 9.5% of respondents serving for the first time as elected representatives. The maximum number of years serving in elected positions in the sample is 37 years, which corresponds with the time when Spain returned to democracy after Franco’s dictatorship (1978-79). Apart from these main variables, the models include three more control variables: age, level of education, and the population size of the mayors’ municipality.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS[up]

“Mandate” vs. “accountability” notions of democracy[up]

Table 3 shows the regional distribution of agreement on the statements summarizing the notions of democracy, which in most cases deal with the level of citizens’ participation in local democracy. In general, statements that point to a higher degree of citizen participation in local politics receive higher support (higher scores point to more agreement) than the ones pointing to a representative or “accountability” view of democracy. The widest agreement is found on the statement according to which “residents should participate actively and directly in making important local decisions”, while the least agreed upon statement is that “apart from voting, citizens should not be given the opportunity to influence local government policies”. Moreover, the standard deviation for each statement shows that variation tends to be quite lower in statements close to a participatory view, unlike those that receive more negative scores, which points to the possibility of heterogeneous effects along other variables.

Table 3.

Average agreement statements regarding participation of citizens in local democracy (1=strongly disagree/5=strongly agree)

| CCAA | Parties most suitable | Residents should participate | Residents’ views known before decisions | Nothing apart from voting | Council decisions reflect majority | Political representatives independent | Make policies depend on results | Local decentralization necessary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalucía | 3.34 | 4.17 | 4.12 | 1.98 | 4.22 | 3.05 | 3.58 | 3.46 |

| Aragón | 3.00 | 3.80 | 4.00 | 1.40 | 3.60 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.40 |

| Balears, Illes | 2.92 | 4.23 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 3.69 | 3.15 | 3.38 | 3.46 |

| Canarias | 2.56 | 4.38 | 4.31 | 2.25 | 4.19 | 3.62 | 3.31 | 3.62 |

| Cantabria | 2.75 | 4.00 | 4.25 | 1.25 | 4.75 | 3.25 | 3.50 | 3.75 |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 3.75 | 4.11 | 3.88 | 2.67 | 3.78 | 3.33 | 3.56 | 3.78 |

| Castilla y León | 3.71 | 3.71 | 4.00 | 2.14 | 3.86 | 3.29 | 3.86 | 3.43 |

| Catalunya | 3.13 | 4.29 | 4.31 | 1.98 | 3.99 | 3.19 | 3.75 | 3.53 |

| Comunidad de Madrid | 3.63 | 4.16 | 4.11 | 2.47 | 3.94 | 3.67 | 3.47 | 3.47 |

| Comunitat Valenciana | 3.08 | 4.42 | 4.30 | 2.42 | 3.92 | 3.05 | 3.40 | 3.50 |

| Extremadura | 3.00 | 3.40 | 3.20 | 2.00 | 3.80 | 3.40 | 3.60 | 2.60 |

| Galicia | 3.25 | 4.19 | 4.06 | 2.40 | 4.06 | 3.31 | 3.88 | 3.19 |

| La Rioja | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.50 |

| Navarra | 3.00 | 4.75 | 4.62 | 1.75 | 4.00 | 2.75 | 3.38 | 4.00 |

| País Vasco | 2.94 | 3.88 | 4.12 | 2.31 | 3.81 | 3.38 | 3.50 | 3.44 |

| Principado de Asturias | 3.40 | 4.40 | 3.80 | 2.00 | 4.20 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.40 |

| Región de Murcia | 3.42 | 4.08 | 3.92 | 2.33 | 3.92 | 3.58 | 3.67 | 3.17 |

In order to test for this heterogeneity, we fit a multilevel linear regression model of mayoral agreement on each statement dealing with various forms and levels of citizen involvement in politics, taking into account a number of individual and contextual variables, the results of which are presented in table 4. As expected, ideology carries a major explanatory power, with leftist mayors showing higher levels of agreement with statements implying higher levels of citizen participation (i.e., a “mandate” view), and rightist mayors supporting statements involving lesser or participation or simply keeping the statu quo (“accountability” model).

Table 4.

Multilevel regression model of agreement on statements regarding participation of citizens in local democracy (1 = strongly disagree /5 = stongly agree)

| Agreement (1 = strongly disagree / 5= stongly agree) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parties most suitable | Residents should participate | Residents’ views known before decisions | Nothing Apart from voting | Council decisions reflect majority opinion | Political representatives independent | Make policies depend on results | Decentralization to local necessary | |

| Ideology (L-R) | 0.053 p<0.1; (0.029) |

-0.100 p<0.01. (0.023) |

-0.064 p<0.01. (0.020) |

0.124 p<0.01. (0.036) |

-0.031 (0.024) |

0.146 p<0.01. (0.032) |

0.081 p<0.01. (0.029) |

-0.012 (0.026) |

| Age | 0.008 (0.048) |

-0.021 (0.039) |

0.004 (0.034) |

0.020 (0.059) |

0.036 (0.039) |

-0.027 (0.052) |

0.024 (0.048) |

0.015 (0.043) |

| Age squared | -0.0001 (0.001) |

0.0001 (0.0004) |

-0.0001 (0.0004) |

-0.0002 (0.001) |

-0.0004 (0.0004) |

0.0002 (0.001) |

-0.0001 (0.001) |

-0.0001 (0.0005) |

| Female | -0.112 (0.137) |

0.027 (0.111) |

0.030 (0.097) |

0.138 (0.169) |

0.048 (0.110) |

-0.022 (0.150) |

-0.336 p<0.05; (0.137) |

0.102 (0.123) |

| Education Elementary | -0.085 (0.451) |

0.018 (0.365) |

0.289 (0.316) |

0.261 (0.552) |

-0.284 (0.420) |

-0.658 (0.493) |

-0.322 (0.452) |

0.242 (0.405) |

| Secondary | -0.175 (0.161) |

-0.012 (0.128) |

0.071 (0.112) |

-0.318 (0.199) |

-0.070 (0.127) |

-0.204 (0.175) |

-0.103 (0.159) |

-0.282 p<0.05; (0.142) |

| Years elected | 0.007 (0.007) |

-0.008 (0.006) |

-0.009 p<0.1; (0.005) |

0.022 p<0.05; (0.009) |

-0.0002 (0.006) |

0.024 p<0.01. (0.008) |

-0.008 (0.007) |

-0.003 (0.007) |

| Municipal size (log) | 0.099 (0.068) |

0.086 (0.054) |

0.059 (0.048) |

-0.053 (0.083) |

0.018 (0.054) |

0.072 (0.074) |

-0.139 p<0.05; (0.067) |

0.161 p<0.01. (0.060) |

| Constant | 1.884 (1.246) |

4.447 p<0.01. (1.008) |

3.885 p<0.01. (0.880) |

1.428 (1.525) |

3.142 p<0.01. (1.002) |

2.542 p<0.1; (1.361) |

3.861 p<0.01. (1.248) |

1.426 (1.115) |

| Observations | 242 | 244 | 240 | 241 | 242 | 242 | 244 | 244 |

| Log Likelihood | -328.637 | -281.072 | -243.402 | -373.599 | -276.977 | -348.742 | -331.373 | -304.999 |

| AIC | 679.273 | 584.143 | 508.805 | 769.198 | 575.954 | 719.484 | 684.746 | 631.999 |

In particular, the more mayors place themselves to the left the stronger their agreement is with statements that imply that “residents should participate actively and directly in making important local decisions”, and that “residents should have the opportunity to make their views known before important local decisions are made by elected representatives”. On the other hand, when mayors place themselves on the right they show higher levels of agreement with statements that affirm that “political parties are the most suitable arena for citizen participation”, that “apart from voting, citizens should not be given the opportunity to influence local government policies”, that “political representatives should make what they think are the right decisions, independent of the current views of local people”, and that “the results of local elections should be the most important factor in determining local government policies”.

Turning now to political experience, the number of years serving in elected positions tends both, to play against statements that involve higher or deeper levels of citizen involvement in politics, and to significantly reinforce the statu quo. For instance, while (as mentioned above) leftist mayors significantly agree with a statement such as “residents should have the opportunity to make their views known before important local decisions are made by elected representatives”, their support diminishes with political experience (negative coefficient). On the other hand, agreement with statements that either limit the ability of citizens to exert influence beyond voting or that ensure the independence of political representatives beyond current public opinion, tends to grow higher among those mayors that have more experience as politicians. Finally, no other variable seems to have an impact on mayors’ notions of democracy.

These results, therefore, allow us to give preliminary support to our first hypothesis

that linked more leftist ideology with wider support to a “mandate” view of democracy.

On the one hand, the relationship between mayors’ ideology and their notions of democracy

gives preliminary support to the exogenous model of notions of democracy. These results,

moreover, are consistent with those reported by Heinelt ( Heinelt, Hubert. 2013a. “Councillors’ notions of democracy, and their role perception

and behaviour in the changing context of local democracy”, Local Government Studies, 39 (5): 640-660. Available at:

Table 5.

Loadings of the factor analysis of all dimensions of agreement on statements regarding participation of citizens in local politics. “Varimax” rotation

|

Factor1

(Mandate view) |

Factor2

(Accountability view) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Residents should participate actively and directly in making important local decisions. | 0.726 | –0.228 |

| Residents should have the opportunity to make their views known before important local decisions are made by elected representatives. | 0.662 | –0.156 |

| Decentralization within local government is necessary to involve citizens in public affairs. | 0.395 | 0.038 |

| Council decisions should reflect a majority opinion among the residents. | 0.341 | 0.016 |

| Apart from voting, citizens should not be given the opportunity to influence local government policies. | –0.167 | 0.263 |

| Political parties are the most suitable arena for citizen participation. | 0.095 | 0.423 |

| The results of local elections should be the most important factor in determining local government policies. | 0.006 | 0.451 |

| Political representatives should make what they think are the right decisions, independent of the current views of local people. | –0.185 | 0.536 |

These results, however, do not ensure that mayors are actually consistent in their

notions of democracy —i.e., that they tend to agree and disagree with the statements

in a consistent way. To test the consistency of these findings, we carry out a factor

analysis of the statements regarding democratic notions. Using this very procedure

on data from local councilors from several countries, Heinelt ( Heinelt, Hubert. 2013a. “Councillors’ notions of democracy, and their role perception

and behaviour in the changing context of local democracy”, Local Government Studies, 39 (5): 640-660. Available at:

We also find that the two factors are highly (negatively) correlated, which supports the idea that mayors align with either one of the two views of democracy, since they are actually theoretically exclusive which, in turn, is consistent with the effect of ideology on their notions of democracy.

Table 6.

Multilevel regression analysis of agreement on the “mandate” view of local democracy

| Mandate view | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ideology (left-right) | -0.104 p<0.01. (0.028) |

-0.234 p<0.01. (0.050) |

| Age | -0.005 (0.044) |

0.002 (0.044) |

| Age squared | 0.00001 (0.0005) |

-0.0001 (0.0005) |

| Female | 0.063 (0.128) |

0.015 (0.126) |

| Education [Ref. University] Elementary | -0.481 (0.477) |

-0.452 (0.467) |

| Secondary | 0.070 (0.153) |

0.042 (0.151) |

| Years since first elected position | -0.010 (0.007) |

-0.041 p<0.01. (0.012) |

| Municipal size (log) | 0.102 (0.065) |

0.115 p<0.1; (0.064) |

| Ideology x Years since first elected | 0.010 p<0.01. (0.003) |

|

| Constant | -0.395 (1.156) |

-0.296 (1.134) |

| Observations | 232 | 232 |

| Log Likelihood | -295.322 | -295.310 |

| Akaike Inf. Crit. | 612.644 | 614.620 |

| Bayesian Inf. Crit. | 650.558 | 655.981 |

To test the effect of ideology and political experience on mayors’ views of democracy, we incorporate the score of each mayor on the first dimension of our factor analysis (“mandate” view of democracy) and use it as a dependent variable in another multilevel linear regression model including ideology and political experience as main independent variables. Results can be observed in Table 6. Again, ideology is the only good predictor of a mandate view of democracy: more leftist mayors tend to agree on a mandate view of democracy in a significant way, while those that place themselves more to the right are significantly less favorable to this model of democracy. In order to test the endogenization of notions of democracy through the institutionalization of representation, we fit an interaction term between ideology and years of political experience (second column of Table 6), and the coefficients for both the interaction and the constitutive terms are significant and with the expected sign. On the one hand, the positive sign of the coefficient of the constitutive term for ideology (–0.234) is to be interpreted as the effect of ideology on agreement to a mandate model for mayors with zero years of experience, that is, for those just starting their careers. Here the effect of ideology is largest. However, the coefficient for the interaction term between ideology and years since first elected (political experience) is positive, which points to a moderating effect of political experience on ideology.

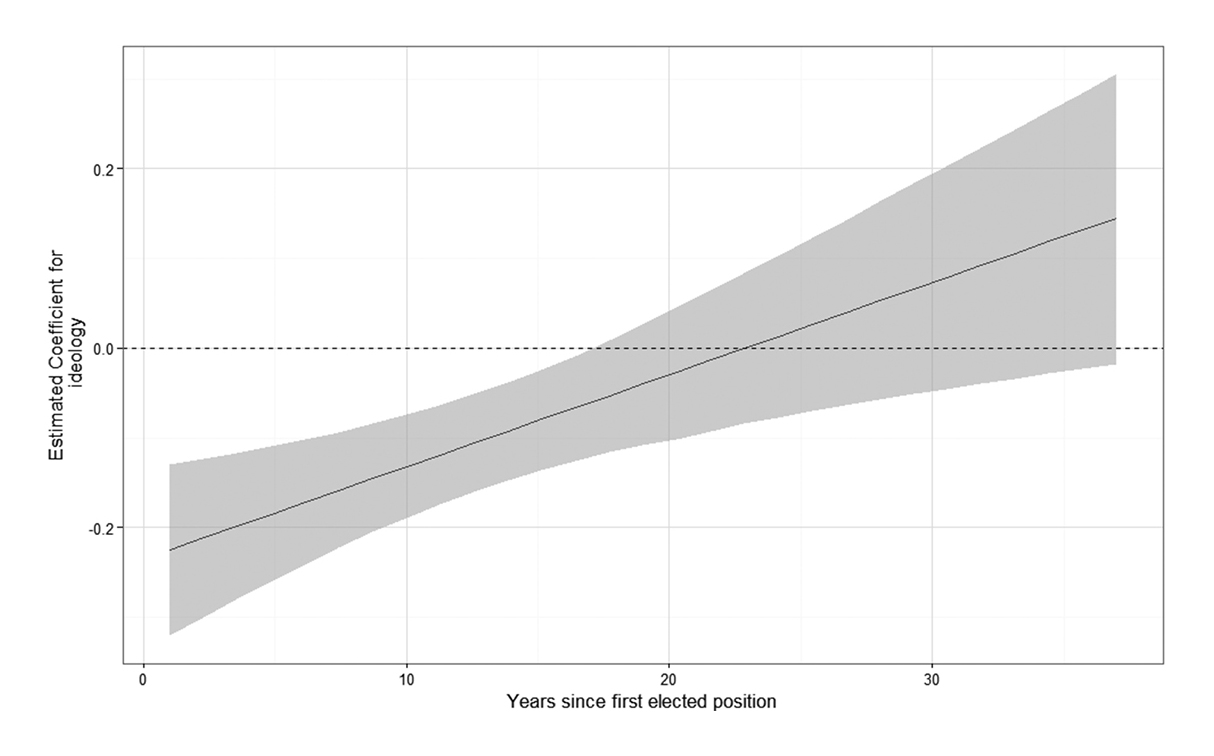

To better depict the effect of this interaction, Figure 1 plots the marginal effect of political experience on the relationship between ideology and mayors’ holding mandate views of democracy. The solid line shows that as mayors grow in political experience, the link between their ideology and their defense of mandate views of democracy weakens (is closer to zero), up to a moment in their career when their ideology just ceases to be a good predictor of their notion of democracy. This critical moment (when the upper confidence interval in Figure 1 crosses the zero line) comes just after finishing their fourth four-year term as elected representatives —i.e., 16 years. In other words, after an average of four terms as elected representatives, leftist mayors will no longer be distinct to rightist mayors in their notions of democracy.

Democratic reforms[up]

Once the effect of ideology and political experience on the mayors’ notions of democracy has been tested, we are ready to test our third hypothesis —the effect of views of democracy on mayors’ support for institutional reforms of local government.

Our data contains five proposals of institutional reform for mayors to score according to their level of desirability. These reforms are:

-

A decisive (binding) referendum.

-

Direct election of the mayor.

-

Non-binding referenda.

-

Participatory Budgeting.

-

Reduction of the number of councilors.

At least two of these proposals —namely binding referendum and participatory budgeting— are clearly related to the mandate view of democracy, since they imply a stronger link between voters and policy, even beyond the role of the representatives. On the other hand, the direct election of the mayor and the reduction of the number of councilors seem more broadly related to an accountability model of democracy, and in particular support the strengthening of the local executive power (direct election of mayor) and the reduction of the number of representativeness of the local assembly (reduction of councilors). Finally, non-binding referenda could fit in either model of democracy, since despite being a form of direct democracy it does not directly bind elected representatives to act according to the results.

Figure 1.

Marginal effect of the interaction between ideology and years since first elected position

The plot shows that leftist ideology has a significant effect on mandate views of democracy, but that this effect diminishes with time spent as a politician.

Table 7 shows the results of five separate regression models on the level of desirability mayors’ express regarding each reform proposal. On the one hand, ideology explains significant variation in four of the five items even controlling for both individual and contextual factors, according to our expectations. Left-wing mayors (which according to our previous results are prone to hold a mandate view of democracy) present significant support for binding referenda and participatory budgeting, while right-wing mayors (supporters of an accountability view) tend to support the direct election of the mayor and the reduction of the number of councilors in the local assembly. Ideology, finally, seems to have no effect on the support to reforms implying non-binding referenda. Interestingly, moreover, political experience tends to run against these democratic reforms. Thence, the higher the number of years since a mayor’s first elected position, the lower her support for participatory reforms such as binding referenda and participatory budgeting, which tend to be supported by leftist mayors. Moreover, as mayors grow in political experience, they tend to be more supportive of being directly elected by voters, although they also tend to be less supportive of reforms that imply a reduction of the number of councilors.

Table 7.

Multilevel model of support to institutional reforms with varying intercept by region. Desirability of reforms (1 = highly undesirable / 5 = highly desirable)

| Desirability of reforms (1=highly undesirable / 5=highly desirable) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Binding

referendum |

Direct election

of mayor |

Non-binding

referenda |

Participatory

budgeting |

Reduction no.

councilors |

||

| Ideology | –0.090 p<0.01. (0.033) |

0.062 p<0.1; (0.035) |

–0.027 (0.029) |

–0.178 p<0.01. (0.025) |

0.059 p<0.1; (0.032) |

|

| Age | 0.056 (0.053) |

0.045 (0.055) |

–0.053 (0.046) |

0.036 (0.041) |

0.093 p<0.1; (0.052) |

|

| Age squared | –0.001 (0.001) |

–0.0004 (0.001) |

0.0005 (0.0005) |

–0.001 (0.0004) |

–0.001 (0.001) |

|

| Female | –0.015 (0.152) |

–0.255 (0.157) |

0.048 (0.133) |

0.107 (0.120) |

–0.096 (0.149) |

|

| Education [Ref. University] Elementary | 0.365 (0.494) |

–1.354 p<0.01. (0.512) |

–0.711 (0.432) |

0.447 (0.388) |

0.428 (0.483) |

|

| Secondary | –0.155 (0.183) |

–0.247 (0.190) |

0.254 (0.157) |

0.035 (0.140) |

–0.074 (0.174) |

|

| Years first elected position | –0.016 p<0.1; (0.008) |

0.015 p<0.1; (0.008) |

0.003 (0.007) |

–0.011 p<0.1; (0.006) |

–0.014 p<0.1; (0.008) |

|

| Municipal size (log) | 0.004 (0.075) |

–0.157 p<0.05; (0.076) |

0.248 p<0.01. (0.066) |

0.234 p<0.01. (0.057) |

–0.118 (0.073) |

|

| Constant | 2.509 p<0.1; |

3.601 p<0.05; |

2.276 p<0.1; |

1.978 p<0.1; |

1.016 | |

| Observations | 237 | 238 | 237 | 240 | 239 | |

| Log Likelihood | -342.583 | -352.574 | -312.189 | -290.323 | -339.545 | |

| Akaike Inf. Crit. | 707.166 | 727.148 | 646.378 | 602.645 | 701.089 | |

| Bayesian Inf. Crit. | 745.314 | 765.343 | 684.526 | 640.932 | 739.330 | |

Table 8.

Factor analysis results of democratic reforms. “Varimax” rotation

| Type of reform | Variable | Mandate | Accountability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participatory Budgeting | D26 4 | 0.989 | -0.131 |

| Binding referendum | D26 1 | 0.371 | -0.047 |

| Non binding referenda | D26 3 | 0.081 | -0.156 |

| Direct election of mayor | D26 2 | -0.062 | 0.188 |

| Reduction number of councillors | D26 5 | 0.179 | 0.981 |

However, to what extent is there a consistent relationship between mayors’ notions of democracy and their support to institutional reforms? To test this relationship we follow the same method of reduction of variation employed above and carry out a factor analysis of the responses on these five proposals of institutional reform, as shown in Table 8. As expected, participatory budgeting and binding referendum score high in the first dimension, while direct election of the mayor and the reduction of the number of councilors score higher in the second. Somewhere in the middle lies the non-binding referendum, although it scores slightly higher in the first dimension. We use each mayor’s score on the first dimension as dependent variable to test, first, the effect of ideology and political experience, and, second, the consistency between notions of democracy and support for reforms.

The results of this test are in Table 9, and give support to our hypothesis. The first two columns report the effect of ideology and political experience on support for more participatory reforms, and results show a high level of consistency. Again, the negative coefficient for ideology shows that as mayors move from left to right their support for participatory reforms decreases even controlling for age, gender, education, political experience and the size of their municipality. Moreover, as long as mayors increase their experience as politicians, their support for institutional reforms that would increase the direct participation of citizens shaping policy decisions (budget and referenda) decreases. The interaction term in the second column shows that given enough time as elected representatives, mayors’ ideology ceases to be a predictor of their support to participatory reforms.

The last two columns of Table 9 tell a similar story, but having mayors’ notions of democracy instead of ideology as the main independent variable. Coherently with our previous findings, mayors who hold mandate views of democracy tend to support institutional reforms that should increase the role of citizens in political decisions at the local level. Besides, even controlling for mandate view, mayors with more political experience tend to give less support to these participatory reforms. Therefore, their political career seems, again, to run against this link between notions of democracy and support for “mandate” reforms, although in this case the interaction coefficient, having the right sign, is not significantly different from zero.

Table 9.

Multilevel regression analysis of support to participatory reforms on ideology and participatory views

| Dependent variable: Mandate reforms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideology (left-right) | -0.179 p<0.01. (0.033) |

-0.276 p<0.01. (0.060) |

||

| Mandate view | 0.463 p<0.01. (0.071) |

0.507 p<0.01. (0.130) |

||

| Age | 0.083 (0052) |

0.091 p<0.1; (0.051) |

0.087 p<0.1; (0.048) |

0.090 p<0.1; (0.048) |

| Age squared | -0.001 p<0.1; (0.001) |

-0.001 p<0.05; (0.001) |

-0.001 p<0.1; (0.001) |

-0.001 p<0.05; (0.001) |

| Female | 0.104 (0.148) |

0.070 (0.148) |

0.242 p<0.1; (0.137) |

0.239 p<0.1; (0.137) |

| Education [Ref. University] Elementary | 0.545 (0.478) |

0.527 (0.475) |

0.163 (0.505) |

0.131 (0.513) |

| Secondary | 0.106 (0.179) |

0.067 (0.179) |

0.291 p<0.1; (0.170) |

0.289 p<0.1; (0.170) |

| Years first elected position | -0.015 p<0.1; (0.008) |

-0.040 p<0.01. (0.015) |

-0.013 p<0.1; (0.007) |

-0.013 p<0.1; (0.007) |

| Municipal size (log) | 0.237 p<0.01. (0.077) |

0.251 p<0.01. (0.076) |

0.111 (0.073) |

0.112 (0.073) |

| Ideology x Years first elected | 0.008 p<0.1; (0.004) |

|||

| Mandate x Years first elected | -0.003 (0.008) |

|||

| Constant | -3.291 p<0.05; (1.355) |

-3.284 p<0.05; (1.347) |

-2.944 p<0.05; (1.256) |

-2.996 p<0.05; (1.265) |

| Observations | 232 | 232 | 224 | 224 |

| Log Likelihood | -327.735 | -330.471 | -297.415 | -301.193 |

| Akaike Inf. Crit. | 677.469 | 684.941 | 616.830 | 626.386 |

| Bayesian Inf. Crit. | 715.383 | 726.302 | 654.358 | 667.326 |

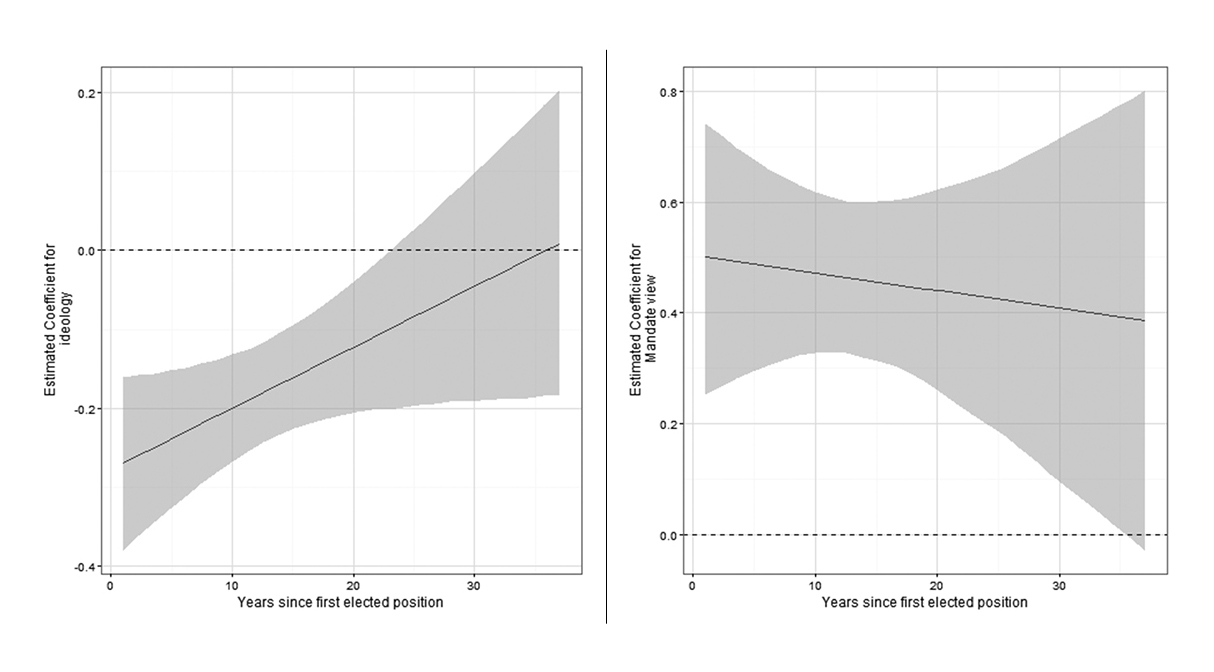

Figure 2.

Marginal effects of ideology and mandate views on support to participatory reforms, by number of years since first elected position

The effect of political time on the consistency between ideology and notions of democracy, and support for participatory reforms at the local level can be observed in Figure 2. The left panel shows the marginal effect of political experience on the coefficient for ideology. In this case, ideology ceases to be a good predictor of support for participatory institutional reforms after 23 years of political experience. Let us recall that in our previous findings the critical point when ideology ceased to be a good predictor of “mandate” notions of democracy was 16 years. This finding supports the idea of the existence of a chain of causality between political experience, notions of democracy, and support for institutional reforms, in which political experience first erodes mayors’ notions of democracy at a faster pace. Although in the right panel of Figure 2 confidence intervals are too wide, we see that time spent serving in elected positions also tends to erode the link of consistency between holding a mandate view of local democracy and the support for reforms that would increase the role of citizens in shaping policy at the local level.

CONCLUSIONS, LIMITATIONS AND FURTHER RESEARCH[up]

Understanding the notions of democracy that drive mayors’ political decision making is crucial for the understanding of local democracy and this article represents a first attempt to study Spanish mayors’ notions of democracy. Consequently, this research was designed to survey and explore the factors that influence mayors’ notions of democracy in Spanish municipal governments with populations over 10,000 inhabitants. In this study, being the first to look systematically into this timely issue in Spain, we hypothesized that mayors’ notions of democracy are influenced both by endogenous and exogenous factors. The hypotheses are grounded on two groups of theories: neo-institutionalism and theories of individual factors that shape political preferences. Both theories refer to the institutional and personal factors that influence mayors’ notions of democracy.

Three sets of findings stand out from this research. First, and taken together, our findings are consistent and in tune with prior findings in that exogenous factors are key factors influencing mayors’ notions of democracy and, therefore, influencing and shaping mayors’ political behavior and performance. It is also relevant a second set of findings indicating that mayors’ support for a model of representative democracy over a mandate model is endogenous to their experience while holding office. According to this, our study indicates that, as suggested by the neo-institutional approach, mayors’ notions of democracy tend to adjust to their experience, measured here by the number of years serving as representatives. Yet, overall our study suggests that notions of democracy are shaped by both institutional factors and personal preferences derived from individual factors.

The multilevel linear regression analysis and the factor analysis we have applied in this study show both consistent and significant statistical evidence supporting our three hypotheses. Regarding the first one, we have showed that ideology (an exogenous factor from an institutionalist standpoint, employed here as independent variable) results an excellent predictor of the mayor’s view of democracy (dependent variable). There is a strong and positive relationship between the agreement on a participatory (or mandate) model of democracy and a leftist position on the classic 11-point self-placement scale. In an analogous way, rightist positions yield high positive coefficients with agreements on representative (or accountability) models.

Political experience (an endogenous factor measured here as the number of years holding elected office, and employed in our analysis as the other main independent variable) also has an effect on support for the models of democracy researched. In particular, our data show statistical significant evidence of a negative relationship between political experience and the support for a mandate (participatory) model. Although the effects are not large, it is clear that the support for participatory views of democracy decreases with a greater number of years serving in elected positions. Moreover, the main finding is that the political experience erodes, slowly but gradually, the effect of ideology on the view of democracy, confirming so our second hypothesis.

The same kind of conditional effects between ideology (exogenous factor) and political experience (endogenous one) can be found when we analyze their impact on the support for democratic reforms (our second main dependent variable). Considered separately, the effect of ideology is stronger than that of political experience on the support for specific democratic reforms. Of course, left positions are positively and strongly correlated with the preference for a participatory or mandate model democratic reforms. However, once more, political experience erodes the effect of ideology on the support of participative democratic reforms, confirming our third hypothesis, although, in this case, the effect of political experience is weaker. This fact might be explained because in the Spanish setting many mayors perform both political and administrative managerial functions.

Being the first study of this kind in Spain, we remain cautious about the interpretation of our results, for a number of reasons. First, one important limitation of our study is that the data analyzed refer only to municipalities with populations over 10 000 inhabitants. Taking into account that most Spanish municipalities have less than 10 000 inhabitants, the results lack full generalization capacity and therefore it would be worthwhile to extend the analysis presented here to smaller municipalities. Apart from the need to broaden our sample, another limitation is that the items used as dependent variables to measure the notions of democracy are too limited and it would be desirable to verify our findings in a study including more items. Other possible factors that may explain variation in mayors’ notions of democracy include, for example, cultural and civil society issues within the locality or how much transparency in political decision-making and government policy-making they are prepared to support as well as mayors’ socialization within their political party. Of course, similar limitations of the indicators could be noted for the independent variables employed in the survey. In particular, political experience measured only by the number of years elected in office leaves out potentially relevant details on what happened during those years: level of government served, whether they had governmental responsibilities or were in the opposition, main issues faced during office, and the responses they had taken. Future rounds of the survey can improve reliability and accuracy by using longitudinal data as well as in-depth case studies to investigate how notions of democracy are acquired and developed.

Despite these concerns, we are convinced that our empirical study contributes to understand more thoroughly the functioning of local democracy. This research is important because it provides a national study of mayors’ notions of democracy, and also the results presented here are of relevance for comparative cross-country research and suggest some directions for further research in order to test and to contextualize our findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS[up]

This work has benefited from the funds of the LoGoRef project: “Una nueva arquitectura local: eficiencia, dimensión y democracia” (CSO2013-48641-C2-2-R, MCOC-Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad).

Notes[up]

References[up]

|

Bäck, Henry, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier (eds.). 2006. The European Mayor: Political Leaders in the Changing Context of Local Democracy. Heidelberg: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-90005-6. |

|

|

Bäck, Henry. 2006. “Does recruitment matter? Selecting path and role definition”, in Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier (eds.), The Eurpean Mayor. Political Leaders in the Changing Context of Local Democracy (pp. 123-150). Heidelberg: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-90005-6_6. |

|

|

Barber, Benjamin. 2003. Strong Democracy: Participatory Politics for a New Age. Berkeley: University of California Press. |

|

|

Bledsoe, Thimoty. 1993. Careers in City Politics. The Case for Urban Democracy. Pittsburgh and London: University of Pittsburgh Press,. |

|

|

Borraz, Olivier and Peter John. 2004. “The transformation of urban political leadership in western Europe”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28 (1):107-120. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00505.x. |

|

|

Cohen, Joshua. 2007. “Deliberative democracy”, en S. R. Rosenberg (ed.), Deliberation, Participation and Democracy. Can the People Govern? (pp. 219-236). New York: Palgrave Macmillan, Houndsmill. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230591080_10. |

|

|

Denters, Bas and Pieter-Jan Klok. 2013. “Citizen democracy and the responsiveness of councillors: The effects of democratic institutionalisation on the role orientations and role behaviour of councilors”, Local Government Studies, 39 (5): 661-680. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2012.670747. |

|

|

Eldersveld, Samuel J., Lars Strömberg and Wim Derksen. 1995. Local Elites in Western Democracies: A Comparative Analysis of Urban Political Leaders in the U.S., Sweden, and the Netherlands. Boulder: Westview Press. |

|

|

Gelman, Andrew and Jeniifer Hill. 2007. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. |

|

|

Genieys, William, Xavier Ballart and Pierre Valarié. 2004. “From ‘great’ leaders to building networks: The emergence of a new urban leadership in southern Europe?”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28 (1):183-199. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00510.x. |

|

|

Goldsmith, Mike and Helge Larsen. 2004. “Local political leadership: Nordic style”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28 (1):121-133. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00506.x. |

|

|

Haus, Michael and David Sweeting. 2006a. “Local democracy and political leadership: Drawing a map”, Political Studies, 54: 267-288. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2006.00605.x. |

|

|

Haus, Michael and David Sweeting. 2006b. “Mayors, citizens and local democracy” en Henry Bäck, Henry, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier (eds.), The European Mayor: Political Leaders in the Changing Context of Local Democracy (pp. 151-176). Heidelberg: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-90005-6_7. |

|

|

Heinelt, Hubert and Nikolaos K. Hlepas. 2006. “Typologies of local government systems”, en Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier (eds.), The European Mayor. Political Leaders in the Changing Context of Local Democracy (pp. 21-42). Heidelberg: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-90005-6_2. |

|

|

Heinelt, Hubert. 2013a. “Councillors’ notions of democracy, and their role perception and behaviour in the changing context of local democracy”, Local Government Studies, 39 (5): 640-660. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2012.670746. |

|

|

Heinelt, Hubert. 2013b. “Introduction: The role perception and behaviour of municipal councillors in the changing context of local democracy”, Local Government Studies, 39 (5): 633-639. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2012.670745. |

|

|

Karlsson, David. 2013. “The hidden constitutions: How informal political institutions affect the representation style of local councils”, Local Government Studies, 39 (5): 681-702. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2012.670748. |

|

|

Kersting, Norbert and Angelika Vetter (eds.). 2003. Reforming Local government in Europe. Closing the gap between democracy and efficiency. Oplanden: Leske und Budrich. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-11258-7. |

|

|

Kœr, Ulrik. 2006. “The mayor’s political career”, en Henry Bäck, Hubert Heinelt and Annick Magnier (eds.), The European Mayor. Political Leaders in the Changing Context of Local Democracy (pp. 75-98). Heidelberg. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. |

|

|

Leach, Steve and David Wilson. 2004. “Urban elites in England: New models of executive governance”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28 (1): 134-149. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00507.x. |

|

|

Manin, Bernard, Adam Przeworski and Susan C. Stokes. 1999. “Elections and representation”, en Adam Przeworski, Susan C. Stokes and Bernard Manin (eds.), Democracy, Accountability, and Representation (pp. 29-54). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139175104.002. |

|

|

Manin, Bernard. 1997. The principles of representative government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511659935. |

|

|

March, James G. and Herbert A. Simon. 1958. Organizations. New York: John Wiley. |

|

|

March, James G. and Johan P. Olsen. 1984. “The new institutionalism: Organizational factors in political life”, The American Political Science Review, 78 (3): 734-749. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/1961840. |

|

|

March, James G. and Johan P. Olsen. 2006. “The logic of appropriateness”, en Michael Moran, Rein Michael and Robert E. Goodin (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy (pp. 689-708). New York: Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Page, Edward and Michael Goldsmith. 1987. Central and Local Government Relation. Beverly Hills: SAGE. |

|

|

Page, Edward. 1991. Localism and centralism in Europe. Oxfors: Oxford University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198277279.001.0001. |

|

|

Przeworski, Adam. 2010. Democracy and the Limits of Self-Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511778490. |

|

|

Sharpe, Laurence J. 1970. “Theories and values of local government”, Political Studies, 18 (2): 153-174. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1970.tb00867.x. |

|

|

Tarrow, Sidney. 1977. Between Center and Periphery: Grassroots politicians in Italy and France. New Haven: Yale University Press. |

|

|

Wollmann, Hellmut. 2004. “Urban leadership in German local politics: The rise, role and performance of the directly elected (chief executive) mayor”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28 (1):150-165. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00508.x. |

Biography[up]

| [a] |

Political scientist and associate professor of political science at the University

of Barcelona. Between 2014 and 2015 he worked as a post-doc researcher at the University

of Amsterdam. His research and teaching interests include political behavior, the

political economy of judicial politics, and political geography. He also teaches how

to use R for data analysis. |

| [b] |

Assistant professor of political and administrative sciences at the University Rey

Juan Carlos in Madrid. Previously he had taught at the Complutense University, also

in Madrid. His research focuses on issues of local government in Spain and with a

European comparative perspective, with a particular focus on local democratic innovations

and local public management. His second main area of research involves the study of

political corruption in Spain, specifically addressing its role in local policy processes. |