Local interest groups and the perception of power in Spanish cities

Grupos de interés locales y percepción del poder en las ciudades españolas

ABSTRACT

Studies on local interest groups have generated a considerable number of theories on urban power that have eventually become the basis of far-reaching approaches on democracy and collective action. Such literature has been especially concerned with discovering who governs the city, paving the way for discussions on elitism, pluralism and urban regimes. Some approaches consider that the business elite dominates local politics, while other theories assert that interests other than business (neighbors, environmentalists, faith-based organizations, civic groups) have been gaining relevance and access to local government. The POLLEADER survey (2006) provided data on the influence of certain social groups as perceived by mayors in Spain. Data showed that the local business community was, at best, as influential and active as voluntary associations. With recent data from the POLLEADER II survey (2015), this article confirms a certain pluralistic model of local power and, it considers the number of inhabitants and the Mayors’ ideology as key factors to determine variation in the way interest groups’ influence is perceived.

Keywords: power, interest groups, business, cities, mayors.

RESUMEN

Los estudios sobre grupos de interés locales han aportado una cantidad notable de teorías sobre el poder urbano que, tiempo después, facilitarían el desarrollo de enfoques más amplios sobre democracia y acción colectiva. Esta literatura se ha centrado especialmente en descubrir quién gobierna la ciudad con argumentos desde el elitismo, el pluralismo y los regímenes urbanos. Algunos enfoques sugieren que la elite empresarial es preponderante en la política local, mientras otras teorías consideran que otros intereses (vecinales, ecologistas, religiosos, cívicos) han ido ganando peso y acceso al Gobierno local. La encuesta POLLEADER (2006) ofreció datos sobre cómo los alcaldes y las alcaldesas percibían la influencia de ciertos grupos sociales. Los datos mostraron que los empresarios locales eran, a lo sumo, tan influyentes y activos como lo eran las asociaciones voluntarias. Con datos de la encuesta POLLEADER II (2015), este artículo confirma la existencia de un modelo pluralista de poder local, a la vez que identifica el tamaño del municipio y la ideología del Alcalde como los factores clave para determinar la variación en la percepción de la influencia de los grupos de interés.

Palabras clave: poder, grupos de interés, empresarios, ciudades, alcaldes.

INTRODUCTION[up]

City politics, referring to concepts related to government (public administration,

political legitimacy, etc.), representation (local democracy, leadership, interest

mobilization, etc.), and outcomes (public services, public policies, etc.), is currently

generating challenges in terms of huge politico-societal demands. Everything takes

place in cities, from political protests against globalization to the local settlement

of refugees, from industrial renewal to underground cultural movements. Nowadays,

local governments are tackling new metropolitan conflicts that relate to the way cities

seek economies of scale, as well as to the emergence of supra-municipal conflicts,

for example related to infrastructure for transportation, economic growth and industrial

districts, poverty and social exclusion, new technological connections and so on.

This directly relates to classic discussions concerning the size of municipalities,

the difficulties in consolidating metropolitan areas and the overall debate on how

to design good spatial policies ( Bassand, Michel and Daniel Kübler. 2001. “Introduction: Metropolization and Metropolitan

Governance”, Swiss Political Science Review, 7: 121-123.Bassand and Kübler, 2001; Erlingsson, Gissur Ó. and Jörgen Ödalen. 2013. “How Should Local Government be Organised?

Reflections from a Swedish Perspective”, Local Government Studies, 39 (1): 22-46. Available at:

A vast number of new concepts have emerged during the last decade to capture the many

transformations happening at the local level, namely, metropolitanization, cosmopolitan

localism, spatial mobility, urban sprawl, the functional specialization of space,

and so on ( Kübler, Daniel. 2012. “Governing the Metropolis: Towards Kinder, Gentler Democracies”,

European Political Science, 11: 430-445. Available at:

The research carried out by the POLLEADER II project on the transformations of local

governments in Spain in recent times shows that local governments have been (and still

are) looking for multiple ways to find their own space in the multi-level governance

developed in the last decades in the country. Although media attention mostly turns

to levels of government other than local authorities, we cannot ignore the argument

raised by Botella ( Botella, Joan. 1992. “La galaxia local en el sistema político espa-ol”, Revista de Estudios Políticos, 76: 145-160.1992), who points out that the Spanish tradition conceives the municipality as the starting

point when it comes to the regeneration of the political system. Since 1978, Spanish

local governments have focused on the modernization of administrative structures,

the redistribution of scarce resources, adaptation to a series of supra-municipal

structures (Diputaciones, Consejos Comarcales), the creation of mechanisms of local democracy, as well as the management of a growing

number of policy issues that, in many cases, have not been under the formal responsibility

of local authorities Of course, as Wollman (2012) argues, particularities are to be given special attention

when it comes to contextualising local government reforms. Local governments, although

emerging from solid roots in most European countries, mostly the Nordic ones, are

greatly embedded in multi-level structures and logics and thus they cannot escape

from national-based debates on public administration reforms in their entirety. Despite

various attempts to bring up a limited number of local government traditions in Europe,

be it as a North/South divide or as a leadership-pattern model ( Mouritzen, Poul and James Svara. 2002. Leadership at the Apex: Politicians and Administrators in Western Local Governments.

Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Alba, Carlos and Carmen Navarro. 2003. “Twenty Five Years of Local Government in Spain”,

in N. Kerting and A. Vetter (eds.), Reforming Local Government in Europe. Closing the Gap between Democracy and Efficiency.

Opladen: Leske and Budrich. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-11258-7_10.

This article addresses one key aspect within the broad topic of “local democracy” Local democracy includes multiple issues and discussions, ranging from the study of

local policy competencies and institutional structures to issues related to political

behaviour and political participation. This article is moderate in its claims. The

objective here is to analyse a very specific subject, namely that of influence and

transparency.

In this vein, we pose two research questions. The first question relates directly

to the topic of local power in the terms discussed in the literature: “Do Spanish

mayors feel businesspeople are the most influential group in local politics?” The

second question addresses a wider topic on local politics and interest groups in that

we attempt to examine, beyond the perception of influence, how local interest groups

seek influence locally. It is important to mention we are not dealing here with the

(always problematic topic of) measurement of interest group influence on specific

domains. We examine data on how mayors understand various access-related aspects,

such as meeting ( Cotton, Christopher. 2012. “Pay-to-Play Politics: Informational Lobbying and Contribution

Limits when Money Buys Access”, Journal of Public Economics, 96 (3-4): 369-386. Available at:

This article considers these different angles in structuring the content as follows: first, we discuss the main theories on interest groups at the local level, closely related to a much broader discussion on the concentration/dispersion of power. Second, the article offers an empirical analysis of the survey of Spanish mayors conducted by the POLLEADER II project. We opt for an analysis in which the perception of influence and interest group strategies are correlated with relevant variables such as the size of the city, the mayor’s ideology and the mayor’s policy priorities. To capture variance by the type of interest group, the analysis focuses on local businesses, voluntary associations, trade unions and the Church. The final remarks summarize the main conclusions and open the debate on local transparency, a topic that will guide future research on local interest groups in Spain.

LOCAL DEMOCRACY AND INTEREST GROUPS[up]

The study of urban power started back in the 1950s with the debate on the community power launched by Hunter’s ( Hunter, Floyd. 1953. Community Power Structure. A Study of Decision Makers. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.1953) elitist approach. Studies on local power prior to 1950 envisaged urban dynamics as a result of a Darwinian competition. Social groups seemed to organize themselves biologically in the cities, and they behaved according to utilitarian principles in migratory, segregation, and localization issues. As cities were an evolutionary body, these studies were not concerned with decision-making. Power simply was the result of urban adaptation. The reaction from community power theorists was to bring politics back in. Whether it took an elitist standpoint or it followed the pluralist approach, the new wave of studies on urban power considered that the development of cities was the result of decisions made by those who had the power (and the responsibility to govern) in the cities ( Harding, Alan. 1995. “Elite Theory and Growth Machines”, in D. Judge, G. Stoker and H. Wolman (eds.), Theories of Urban Politics. London: Sage Publications.Harding, 2009).

Hunter suggested business was the mightiest power in city politics, for power was unevenly distributed among politicians, administrators and business leaders. Hunter asserted the existence of a dominant alliance between businesses and local politicians, leading to all local decisions benefiting local businesses. Years later, Dahl ( Dahl, Robert A. 1961. Who Governs? Democracy and Power in an American City. Yale: Yale University Press.1961) came up with his famous pluralist approach. The pluralists suggested that no individual exerts influence over all municipal arenas, although there may be individuals who are particularly influential in one area. Dahl —and also Polsby ( Polsby, Nelson. 1963. Community Power and Political Theory. Yale: Yale University Press.1963)— argued that power is much more dispersed than elitists actually believe. Pluralist authors regarded the influence of a particular collective —or organized group— to be sectoral, so it varies across policy areas. It also varies over time.

Since then, the discussion on urban power has focused on two dimensions: on the one

hand, the question of the existence of competing local elites —and the dispersion

of local power; on the other hand, if the business elite dominates local politics

( Abney, Glenn, and Thomas P. Lauth. 1985. “Interest Groups Influence in City Policy-Making:

The Views of Administrators”, Western Political Quarterly, 38: 148-161. Available at:

Here it is worth noting that it would be unwise to assume that what occurs in the

United States will be paralleled in Britain. The tradition and capacity for local

business involvement is greater in the United States. Their local government system

is arguably more open to a “take-over” by business interests. There is an absence

in the U.S.A. of a strongly organized and ideological party politics at the local

level. The scale of local councils in the U.S.A. is generally smaller in terms of

the populations they were and the professional and organizational resources at their

disposal ( Stoker, Gerry and David Wilson. 1991. “The Lost World of British Local Pressure Groups”, Public Policy and Administration, 6 (2): 20-34. Available at:

Regarding the latter dimension, although the emergence of the pluralist approach tried

to explain that power was diffuse and that the elitist approach did not have much

practical application, the neo-elitist theorists ( Bachrach, Peter and Morton S. Baratz . 1962. “Two Faces of Power”, American Political Science Review, 56: 947-952. Available at:

Accepting that local democracies must coexist with the forces of the free market is

the principle of the urban regime analysis. Urban regime theory ( Stone, Clarence. 1989. Regime Politics: Governing Atlanta, 1946-1988. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.Stone, 1989) considers local governments to be concerned primarily with implementing their own

agenda of industrial and social growth, so they seek coalitions with private actors

with which to carry out public services. All actors are constrained by their environment,

so local power is about how actors make policies happen; therefore, they form a regime.

For local regime we must understand the ‘circle of powerful administrators and elected

officials who move in and out the office’ ( Fainstein, Susan S. and Norman Fainstein. 1983. “Economic Change, National Policy

and the System of Cities”, in S.S. Fainstein, N. Fainstein, R. Child Hill, D. Judd

and P. Smith (eds.), Restructuring the Cities: The Political Economy of Urban Redevelopment. New York: Longman.Fainstain and Frainstain, 1983: 256). Stone ( Stone, Clarence. 1989. Regime Politics: Governing Atlanta, 1946-1988. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.1989) suggested the analysis of local power should study the power to carry out objectives,

instead of examining power over others. Stone’s study of local politics in Atlanta

identified the existence of a stable coalition among white downtown business groups,

Black middle class organizations, and elected officials from a succession of city

administrations, which they all cooperated over the years for the development of local

policies ( Mossberger, Karen. 2009. “Urban Regime Analysis”, in J. S. Davies and D. L. Imbroscio

(eds.), Theories of Urban Politics. London: Sage Publications. Available at:

Although labor union officials, party members, leaders of non-profit organizations

and church leaders may also be engaged, businesses are meant to have privileged access

“because of the scope of resources and expertise they command and cities require for

economic development and/or fiscal solvency” ( De Socio, Mark. 2007. “Business Community Structures and Urban Regimes: A Comparative

Analysis”, Journal of Urban Affairs, 29: 339-366. Available at:

It is true that Stone’s theory is critical of the pluralistic view, although it is

not as deterministic as the early elitist approaches. Stone ( Stone, Clarence. 1993. “Urban Regimes and Capacity to Govern”, Journal of Urban Affairs, 15: 1-28. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.1993.tb00300.x.

A similar argument is made by the growth-machine thesis ( Logan, John and Harvey Molotch. 1987. Urban Fortunes: The Political Economy of Place. Los Angeles: University of California Press.Logan and Molotch, 1987). These authors argue that local businesses are one of the main poles of local activity

in that they instigate investments, initiate businesses and launch development strategies.

Local businesses seek the support of various actors in the city, especially the municipal

authorities, also interested in local growth. Studies on urban governance also consider interactions between local authorities and local businesses to be more

intense than with other types of actors ( Navarro-Yañez, Clemente, Annick Magnier and María Antonia Ramírez-Pérez. 2008. “Local

Governance as Government-Business Cooperation in Western Democracies”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32 (3): 531-547. Available at:

However, a number of studies suggest that neighborhood groups, environmental groups,

religious groups, trade unions and minority groups are also relevant to the promotion

of social issues in local politics ( DeLeon, Richard E. 1992. Left Coast City: Progressive Politics in San Francisco, 1975-1991. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.DeLeon, 1992; Mesh, Gustavo S. and Kent P. Schwirian. 1996. “The Effectiveness of Neighbourhood

Collective Action”, Social Problems, 43: 467-483. Available at:

The discussion on local power reserves an important space for the Marxist approach

on urban politics ( Geddes, Mike. 2009. “Marxism and Urban Politics”, in J.S. Davies and D.L. Imbroscio

(eds.), Theories of Urban Politics. London: Sage Publications. Available at:

In general, Marxists focus on the rise of local neoliberalism and its consequences.

It is a process of change from welfare to workfare, in which the market seeks to restore

the power of the economic elites. This process revolves around a mode of governance

that favors business leadership and the growing participation of the private sector

in public management ( Jessop, Bob. 2002. “Liberalism, Neoliberalism and Urban Governance: A State-Theoretical

Perspective”, in N. Brenner and N. Theodore (eds.), Spaces of Neoliberalism: Urban Restructuring in North America and Western Europe.

Oxford: Blackwell. Available at:

Despite the particularities of each of the theoretical approaches, all of them with very different policy frames and research purposes, the literature on urban power suggests three hypotheses:

H1. Business groups are the most influential type of group in local politics.

H2. Other non-business groups are also influential, but their power depends on the public agenda in each of the cities.

H3. Reformist governments are less susceptible to the influence of local groups than non-reformist governments.

The other aspect of influence is interest group access to decision making. The main

issue concerning access is how interest groups develop their influence strategies.

Grant ( Grant, Wyn. 1978. Insider Groups, Outsider Groups and Interest Group Strategies in Britain. Working Papers of Warwick University, Department of Political Science, 19.1978) argued that group strategies are determined by their relative position within decision

making. Groups with access and legitimacy (insider groups) engage in formal negotiation with members of government (and parliament), while groups

opposed to the government are forced to develop outsider strategies. Binderkrantz

et al. have recently raised the concern that “access points are not of equal value across

political arenas and especially not across political systems” ( Binderkrantz, Anne, Helene H. Pedersen and Jan Beyers. 2016. “What is Access? A Discussion

of the Definition and Measurement of Interest Group Access”, European Political Science, 16, 306-321. Available at: doi:10.1057/eps.2016.17. Available at:

A number of studies have recently delved into the motives that lead groups to develop

their particular lobbying strategies and point to a clear connection between the type

of interest group, members’ background and organizational costs. Hanegraaff et al. ( Hanegraaff, Marcel, Jan Beyers and Iskander De Bruycker. 2016. “Balancing Inside and

Outside Lobbying: The Political Strategies of Lobbyists at Global Diplomatic Conferences”,

European Journal of Political Research, 55: 568-588. Available at:

THE PERCEPTION OF POWER IN LOCAL POLITICS IN SPAIN[up]

The starting point in our analysis of the influence of interest groups in the Spanish local arena is Navarro’s ( Navarro, Carmen. 2016. “Los grupos de interés y el Gobierno local en España”, in J. M. Molins, L. Muñoz and I. Medina (eds.), Los grupos de interés en España: la influencia de los lobbies en la política española. Madrid: Tecnos.2016) study included in the book Los grupos de interés en España ( Molins, Joaquim M., Luz Muñoz and Iván Medina (eds.). 2016. Los grupos de interés en España: la influencia de los lobbies en la política española. Madrid: Tecnos.Molins et al., 2016), which happens to be the only research that offers a specific look at this topic. Navarro points out that local associations were the germs of democratic political participation of Spaniards in the early days of the transition to democracy in the late 1970s. Spaniards began to organize themselves in neighborhood associations with a clear political intention to transform neighborhoods and struggle for social improvements, demanding improvements in the infrastructure of cities, in housing policy, in public transport and in schools. These associations emerged in the heat of the urbanization processes of the 1960s, when there was a great rural exodus to large cities such as Madrid and Barcelona. These associations became advocates of social demands given the political situation of the moment and the lack of political pluralism as leftist activists especially nourished them. Neighborhood associations helped create the “history of the city”, particularly in urban areas without strong social capital. This gave a collective identity to the neighborhoods and established spaces for mobilization. After the first democratic municipal elections held in 1979, the neighborhood associations started losing social leadership as they faced an intense reduction in terms of members and resources to the benefit of political parties. Neighborhood associations were still in force, but they tended towards ideological radicalization. In addition, the new constitutional framework of liberties encouraged citizens to form all kinds of specific associations in the fields of culture, business, education, sports, leisure, and youth.

Beyond the voluntary motivations of individuals when it comes to forming associations,

it seems that the thematic range of local associations is restricted, at least by

the matter of political structure. Local governments in Spain are responsible, in

particular, for three major policy areas: a) policies aimed at urban maintenance and

basic social services; b) urban, educational and public health policies, although

these policies are usually shared with other supra-municipal levels; c) policies aimed

at cultural promotion (women, local festivals, music) and social inclusion (immigrants,

the elderly, housing). This implies that the municipal level is fertile ground for

interest groups that defend interests related to community wellbeing, such as neighbourhood

associations, and interests related to the cultural and social spheres, both in promoting

causes and in defence of specific public interests However, cities are also an ideal place for grassroots politics, which are not always

articulated in the form of interest groups. In recent decades, there have been protests

against a wide range of issues, with varying degrees of intensity over time. In the

1990s, there was a revitalisation of the squatter movement in Madrid, still going

to the present day with the Patio Maravillas (also in Barcelona with Can Vies), as well as protests against the Prestige in several Galician cities. There was also a rise in protests of an ecological nature

and in defence of the territory in many municipalities in Catalonia (Plataforma en defensa de l’Ebre) and Valencia (Salvem el Cabanyal).

Although this article does not examine political protest at the local level, the emergence

of political entrepreneurs from the local associations and movements deserves further

research.

Diversity is the most remarkable characteristic of the myriad of local associations in Spain to this day. The main Spanish city councils have agreed on the need to articulate local associations due to the existence of thousands of voluntary groups that seek to contribute to social and political development. One of the most recurrent instruments is the establishment of registers of associations through which to visualize the local associative network in each city, as well as making the participatory process more transparent. The registers of associations of the main Spanish cities account for the formal existence of thousands of associations, many of them with political aspirations and many others focused on meeting their members’ demands, such as the majority of sports clubs. It should be emphasized that only associations with political intentions, meaning that they have a representative vocation, can be considered interest groups by nature, something that is changing greatly at the municipal level. These registers offer really useful information, although in some cases the data may be slightly artificial as being registered is the requirement to access municipal subsidies and for eligibility to manage public services (for instance, sports facilities, health care centers, immigrant care services and care for people with disabilities).

With this in mind, a first comment on the registers is that local employers’ associations

represent a very moderate percentage of the total number of local associations, while

education-driven and culture-oriented associations represent the lion’s share of the

local associative realm. As Table 1 shows, this is the case for Malaga, Zaragoza, Seville, Madrid, Barcelona and Santiago

de Compostela with data as of January 2017 This is a random selection of cities for informative purposes only.

Table 1.

The nature of local associations in six Spanish cities (as of Jan 2017)

| Type of association | Malaga | Zaragoza | Seville | Madrid | Barcelona | Santiago de Compostela | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Neighbourhood | 297 | 12 | 123 | 4,7 | 199 | 7,2 | 187 | 9,3 | 262 | 4,7 | 62 | 10,5 |

| Culture | 591 | 23,8 | 909 | 34,5 | 880 | 31,9 | 354 | 17,5 | 1577 | 28,3 | 121 | 20,5 |

| Sports | 256 | 10,3 | 460 | 17,5 | 319 | 11,6 | 162 | 8 | 550 | 9,9 | 204 | 34,6 |

| Social work/rights | 224 | 9 | 420 | 16 | 110 | 4 | 280 | 13,9 | 364 | 6,6 | 7 | 1,2 |

| Consumers | 10 | 0,4 | 13 | 0,5 | 13 | 0,5 | 22 | 1,1 | 11 | 0,2 | 1 | 0,2 |

| Immigrants | N/A | – | 15 | 0,6 | N/A | – | 66 | 3,3 | 120 | 2,2 | 3 | 0.5 |

| Elderly | 103 | 4,1 | 31 | 1,2 | 41 | 1,5 | 43 | 2,1 | 186 | 3,4 | 6 | 1 |

| Youth | 185 | 7,4 | 104 | 4 | 58 | 2,1 | 87 | 4,3 | 250 | 4,5 | 43 | 7,3 |

| Women | 125 | 5 | 56 | 2,1 | 126 | 4,6 | 70 | 3,5 | 173 | 3,1 | 22 | 3,7 |

| Education (parents) | 201 | 8,1 | 208 | 7,9 | 219 | 8 | 385 | 19 | 644 | 11,6 | 10 | 1,7 |

| Business/professionals | 74 | 3 | 122 | 4,6 | 98 | 3,6 | 90 | 4,5 | 361 | 6,5 | 25 | 4,2 |

| Environment/animals | 46 | 1,9 | N/A | – | 52 | 1,9 | 28 | 1,4 | 171 | 3,1 | 8 | 1,4 |

| Health | 155 | 6,2 | 96 | 3,6 | 516 | 18,7 | 164 | 8,1 | 437 | 7,9 | 66 | 11,2 |

| Foreign aid | 132 | 5,3 | 18 | 0,7 | 28 | 0,9 | 49 | 2,4 | 329 | 5,9 | 11 | 1,9 |

| Religious/local culture | 86 | 3,5 | 59 | 2,2 | 96 | 3,5 | 35 | 1,7 | 119 | 2,1 | N/A | – |

| N | 2485 | 2634 | 2755 | 2022 | 5554 | 589 | ||||||

Source: registers of local associations from each of the cities’ websites.

Data from the registers provide information on the associative ecology, but say little

on local power; there is no information on interest groups’ access to local government,

either. Methodologically, the study of urban influence can be carried out in various

ways, all with strengths and limitations. Each of the schools propose a particular

way of approaching the topic, being useful the study of various dimensions like formal

decision-making, non-formal decision-making, the distribution of private property,

informal alliances among diverse social groups, and so on. Among the possible research

strategies, a first one is to study municipal decisions to analyze the winners and

losers within all groups. Although this is the path used by the main studies on urban

power, the difficulty of analyzing municipal decisions in depth makes them quite specific

to just one city (Atlanta, New Haven, Chicago). Another way is to study the institutional

participation of local associations in forums such as municipal councils. The problem

of analyzing the formal participation of associations is that informal channels of

interaction are not taken into account, which has been proven to be unsound ( Parés, Marc, Jordi Bonet-Martí and Marc Martí-Costa. 2012. “Does Participation Really

Matter in Urban Regeneration Policies? Exploring Governance Networks in Catalonia

(Spain)”, Urban Affairs Review, 48 (2): 238-271. Available at:

The third option is to consult local associations on their perception of influence, leading to an exercise of data verification and identification of real interest groups among the entire set of associations. Data show massive numbers of associations per municipality, which would force us to reduce the number of cities under research. The fourth strategy is to survey the mayors who happen to be the main political actors of their cities, at least in the Spanish case. Mayors know their cities and they are aware of the political interactions between the administration and relevant groups. It is evident that the study of influence here will be somewhat biased, but the perception of influence will always be subjective. The decision to take into consideration the mayors’ opinions leads us to conceptualize power in its most relational aspect, for we are going to consider the contact that Spanish mayors have with local groups. This way, we will consider neither the possible coalitions between social groups that exist in each of the cities in the survey, nor the property of local resources despite its valuable explanatory power. The purpose is to achieve a general picture of local influence in a large number of Spanish municipalities, while other strategies would require specific case studies.

Navarro ( Navarro, Carmen. 2016. “Los grupos de interés y el Gobierno local en España”, in J. M. Molins, L. Muñoz and I. Medina (eds.), Los grupos de interés en España: la influencia de los lobbies en la política española. Madrid: Tecnos.2016) considers interest group influence through mayors’ lenses. She examines the Political Leaders in European Local Governments (POLLEADER) database, which is based on questionnaires to the mayors of municipalities with more than 10 000 inhabitants in 17 European countries for the year 2006. The first conclusion of her work is that business groups and voluntary associations (single-issue groups) had, at that time, a moderate influence on local politics. This is a feature that differentiated Spain from countries like Poland, Sweden and Hungary, where local businesses’ influence was greater than that of other cause groups. Trade unions and the Church had a relatively low influence on local affairs, which is explained by the residual participation of local governments in labor and religious matters.

Our article intends to discuss the validity of this first round of conclusions, as well as to indicate the applicability of the hypotheses derived from the literature on urban power. There are two main reasons for this. The first one is to examine whether we can identify a solid trend in the way the distribution of power is observed in Spanish cities. If a clear trend is not observed, the second reason is to assess the extent to which the context of economic crisis has impacted on local dynamics, taking into account that the theoretical contributions indicate a certain revitalization of business postulates. In that case, the temporal comparison between the first and the second rounds leads us to have a better image of local groups’ influence.

The database comes from the second round of the mayor survey conducted by the POLLEADER II project, in collaboration with European partners, which in Spain has collected the views of 303 mayors from cities with more than 10 000 inhabitants. The questionnaire was distributed in 2015. Part of the questionnaire was devoted to topics of local democracy, including questions about the influence of certain actors on local politics and the more recurring lobbying strategies from local businesses, trade unions, the Church, and voluntary associations. In particular, we are concerned with the following two questions: no. 28 “What kind of means do the following actors use to achieve their goals in your municipality?”. The mayors could indicate between institutional mechanisms (formal negotiations, litigation), grassroots strategies, or presence in the media. Also question no. 34: “On the basis of your experience as a mayor in this city, and independently from the formal procedures, please indicate how influential each of the following actors are over the local authority activities”. These two questions asked about local businesses, trade unions, voluntary associations, and religious groups.

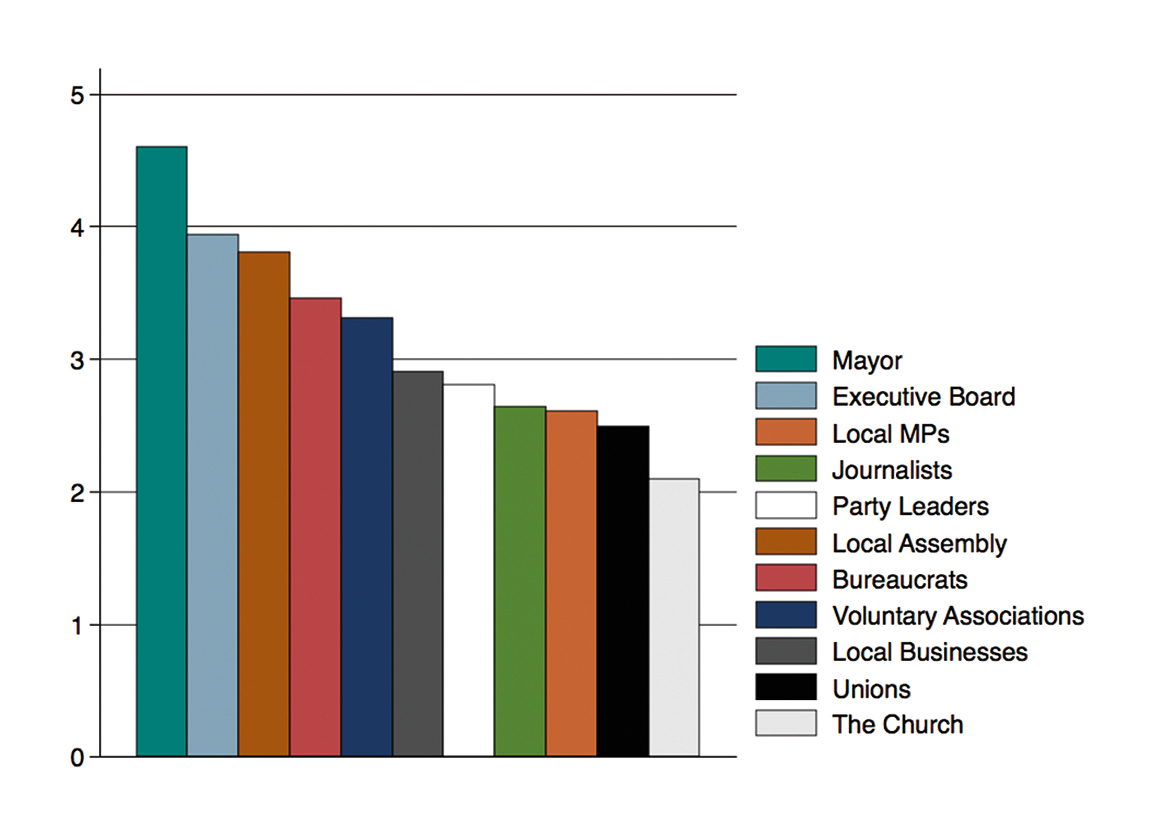

Figure 1.

Spanish mayors approach to the influence of local actors in Spain

Note: Responses to the question “On the basis of your experience as a mayor in this city, and independently from the formal procedures, please indicate how influential each of the following actors are over the local authority activities”. Responses range from 0 (no influence) to 5 (high influence).

Source: 2015 POLLEADER II Survey. Spain.

To begin with the topic of urban power, figure 1 shows that interest groups are moderately influential in local politics but they are, by no means, the dominant actors in local politics. Contrary to the literature, Spanish mayors do not feel local businesses are the most influential group, whereas both voluntary associations and local businesses also enjoy considerable levels of local influence. Actors linked to the government and administration, namely the mayor, the Executive Board, local MPs and local bureaucrats, are the ones possessing the greatest influence in municipal affairs. This perception fits in perfectly with the type of local government suggested by the literature on local governments, which portrays the mayor as the most important political figure in the city. This point raises the importance of considering elected officials as “gatekeepers” when it comes to influencing local decisions and as a result, the study of local power in Spain must recognize the importance of institutions. Social groups appear to be moderately influential actors, although some of them barely influence the municipal agenda (trade unions, the Church).

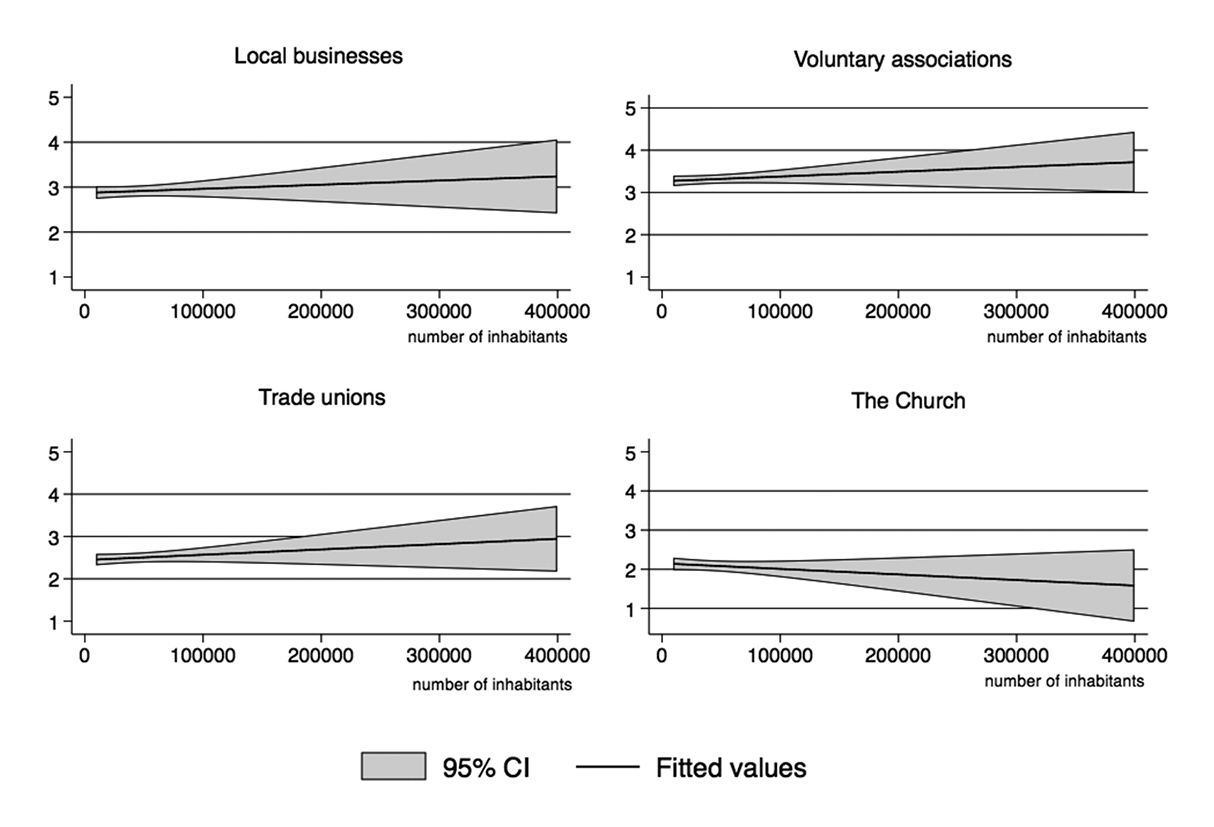

Figure 2.

Interest group influence by number of inhabitants

Note: Responses to the question “On the basis of your experience as a mayor in this city, and independently from the formal procedures, please indicate how influential each of the following actors are over the local authority activities”. Responses range from 0 (no influence) to 5 (high influence).

Source: 2015 POLLEADER II Survey. Spain.

A more detailed analysis of the data in Figure 1 shows some variation in the perception of different social groups’ influence. Given the idea that local businesses might be more influential in large cities, the businessmen’s influence seems to grow slightly as the number of inhabitants of the city increases (see figure 2). This variation is explained by the big cities’ greater political capacity, as well as their greater economic dynamism. This explanation also applies to the case of voluntary associations and trade unions. Large cities generate a greater number of political opportunities, for they boost more intense social and political dynamism. The key point here is that voluntary associations are the most influential type of group regardless of the number of inhabitants in the city. The influence of the Church decreases as the number of inhabitants increases. Large cities are characterized by a greater bureaucratization of social services, as well as by a greater diversity of school and care facilities. The Church finds a larger number of competitors in the management of care services, as well as greater religious diversity. This is why the “social presence” of the Church is more diffuse in large cities.

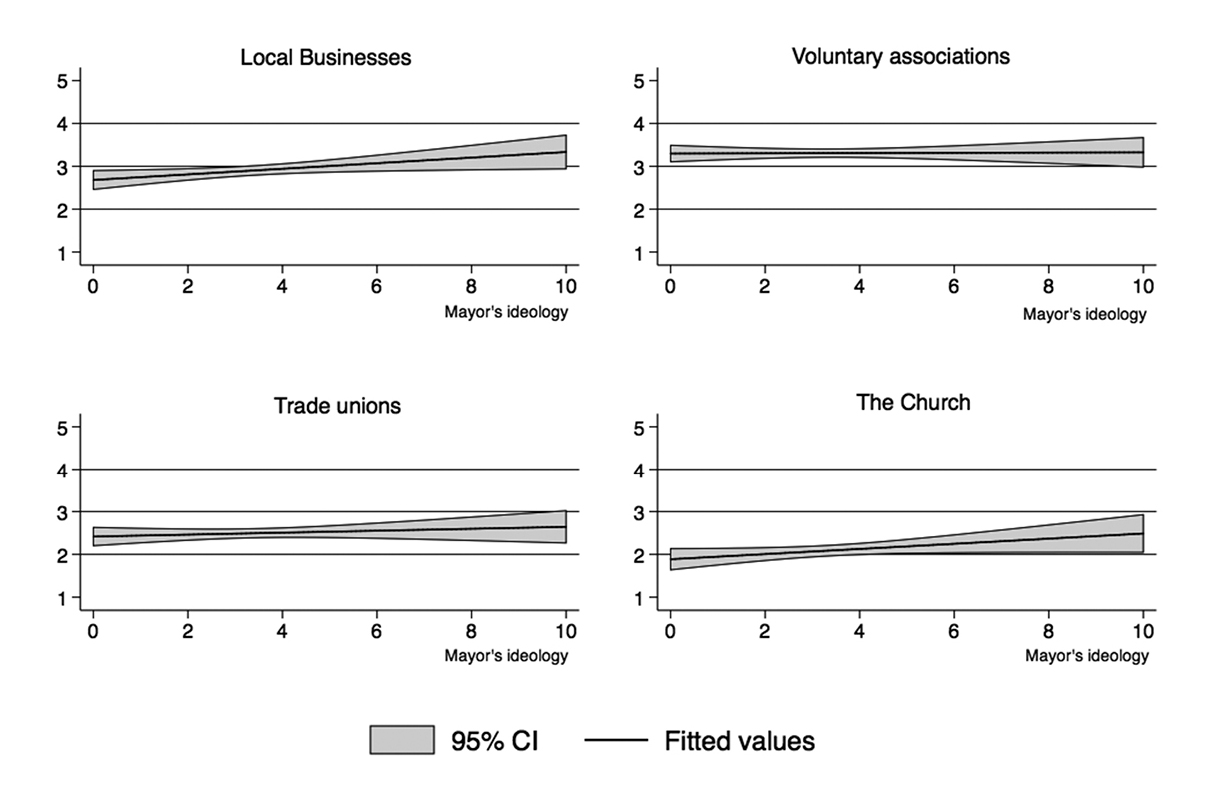

Figure 3.

Interest group influence by mayors’ ideology

Note: Responses to the question “On the basis of your experience as a mayor in this city, and independently from the formal procedures, please indicate how influential each of the following actors are over the local authority activities”. Responses range from 0 (no influence) to 5 (high influence). Mayor’s ideology is measured in a 0-10 scale in which 0 is extreme left and 10 is far-right.

Source: 2015 POLLEADER II Survey. Spain.

At all times, the data reflect mayors’ subjective opinion, which is conditioned by their ideology. One such instance of ideological bias would be that leftist mayors maximize the influence of the businesspeople and the Church with the intention of reinforcing the involvement of the city council in the local economy. Conservative mayors can argue the opposite, meaning that local businesses are not as influential as the left claims. Figure 3 presents the correlation between the influence of the groups and the ideology of the mayors measured on a 0/10 scale. The data support an alternative hypothesis. In general, the mayor’s ideology seems a relevant factor when it comes to explaining variation in the perception of interest groups’ influence. Leftist mayors perceive lower levels of influence of all groups, while the perception of influence increases as mayors position themselves towards a stronger conservative vision. The influence of voluntary associations scarcely varies, but there is a clear impact when it comes to local businesses and the Church. In this regard, conservative mayors assume positive aspects attached to the influence of these groups and, as a result, they are more likely to gain insider status with conservative mayors.

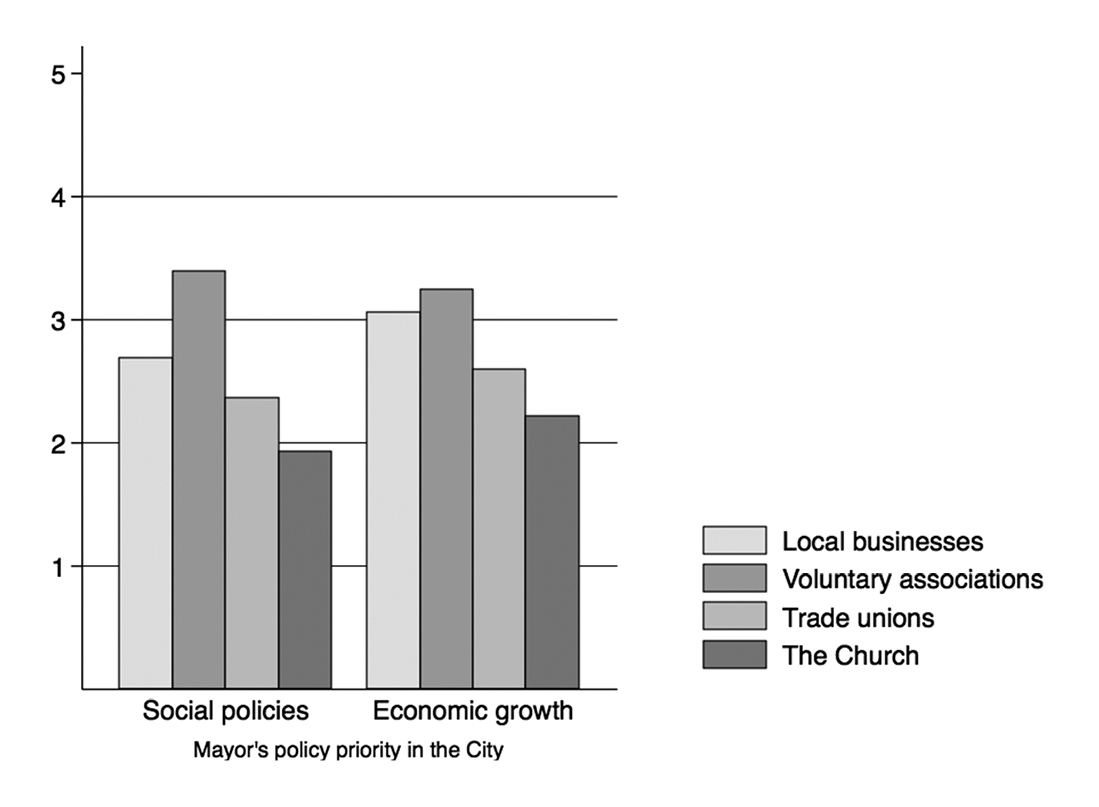

The notion of insider status entails that the government favors the access of certain groups with which it shares an ideological and policy affinity. The discussion concerning figure 3 suggests that mayors with more conservative (or moderate) positions preferentially pursue objectives related to the economic growth of the city, as opposed to objectives related to the strengthening of local welfare. The discussion of interest group influence as a positive element is present in figure 4, which links the perception of influence to mayors’ main policy objective (either social policies or economic growth). Mayors whose objective is the economic development of the city tend to believe that local businesses have greater influence on local affairs than mayors who prioritize social policies. Conversely voluntary associations end up being the most influential group when the city prioritizes social policies. Figure 4 confirms Hypothesis 2, although a small distinction should be made: mayors with a priority other than the city’s economic growth are likely to reduce their dependence on local businesses, but this does not mean that the influence (or positive stance) of the other groups grows massively.

Figure 4.

Interest group influence by mayors’ policy priority

Note: Responses to the question “On the basis of your experience as a mayor in this city, and independently from the formal procedures, please indicate how influential each of the following actors are over the local authority activities”. Responses range from 0 (no influence) to 5 (high influence).

Source: 2015 POLLEADER II Survey. Spain.

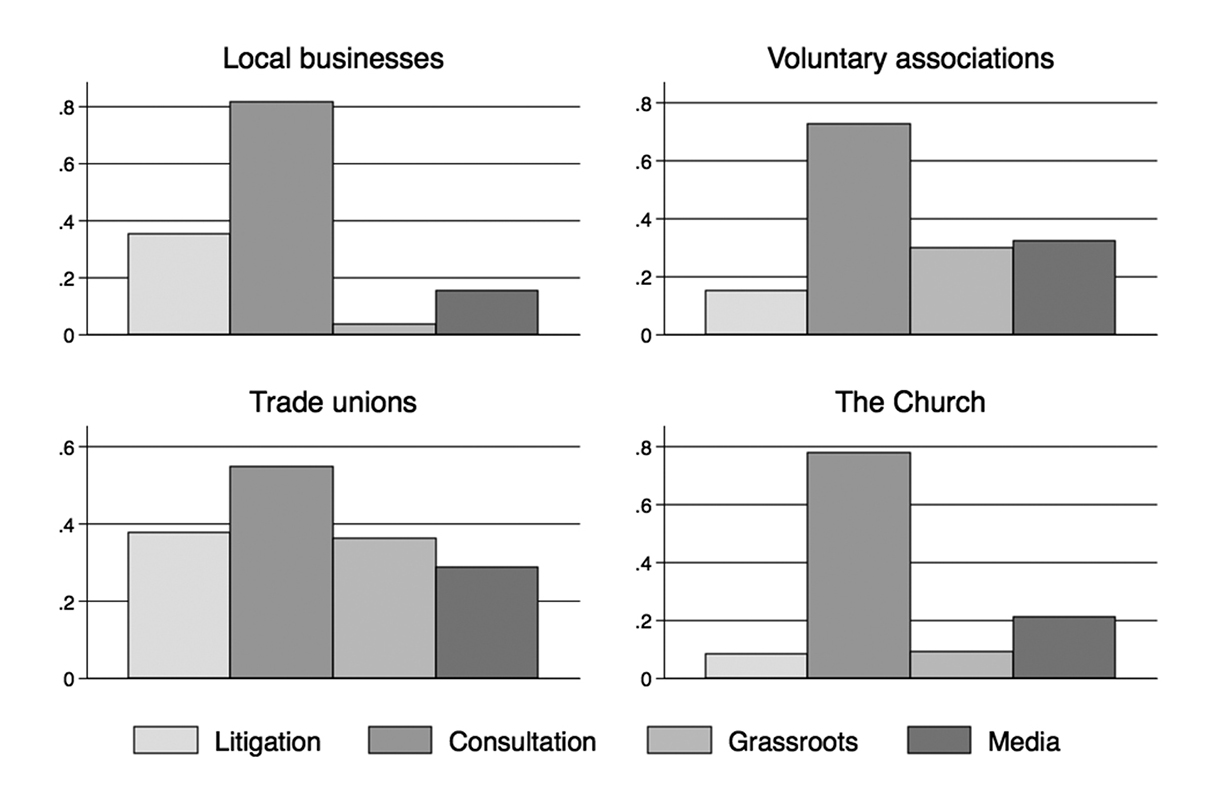

Regarding interest group strategies, figure 5 shows that formal meetings the between local government and social leaders are the most recurring lobbying strategy in all cases. In the specific literature on interest groups, data point to access to local institutions being much less demanding than access to upper levels of government. A closer look at figure 5 allows us to extract valuable information about the preferences of the different groups. Business groups are insider groups that seek formal channels of interaction. Local businesses seldom protest in the streets. They rather choose to litigate with the administration when their interests are not matched. In this regard, local businesses are very similar to the Church. Voluntary associations and unions are “high-profile insider groups”, that is to say, groups with access to municipal government that use the media to raise public awareness for their campaigns. This also explains their determination concerning political protest, as demonstrations at the local level help increase media impact.

Figure 5.

Interest group strategies at the local level

Note: Responses to the question “What kind of means do the following actors use to achieve their goals in your municipality?”. Columns indicate the percentage of mayors who recognize the use of each of the strategies by the groups. Percentages are presented in a range from 0 to 1.

Source: 2015 POLLEADER II Survey. Spain.

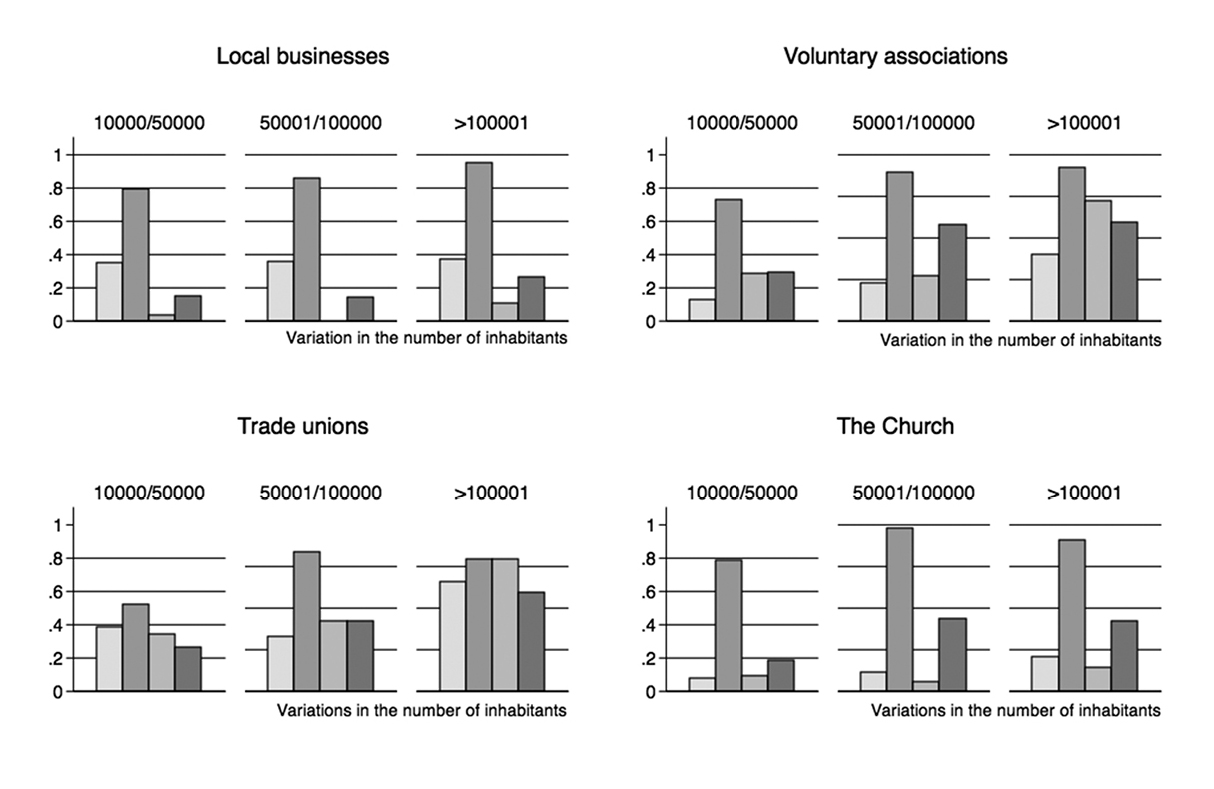

Considering that pressure strategies are determined by the resources available in the political context, pressure strategies are conditioned by the number of competitors, the pressure to attract members and the ability of the group to be visible. Previously, data have highlighted the connection between the municipality size and influence. As for group strategies, this connection also seems to prove correct. Figure 6 shows that the insider profile of local businesses is not affected by the size of the municipality. Local businesses reinforce a formal bargaining strategy (consultation) even in large cities. In other cases, the first conclusion is that access to decision making in large cities is much costlier than in small cities and therefore voluntary associations, trade unions and the Church are all forced to combine insider and outsider strategies. It is also the case that these groups need to develop outsider strategies in big cities, so as to have social impact.

Figure 6.

Interest group strategies by number of inhabitants

Note: Responses to the question “What kind of means do the following actors use to achieve their goals in your municipality?”. Columns indicate the percentage of mayors who recognize the use of each of the strategies by the groups. Percentages are presented in a range from 0 to 1.

Source: 2015 POLLEADER II Survey. Spain.

CONCLUSIONS[up]

The survey of Spanish mayors carried out by the POLLEADER II project offers new data on urban power in Spain, confirming the conclusions raised by Navarro ( Navarro, Carmen. 2016. “Los grupos de interés y el Gobierno local en España”, in J. M. Molins, L. Muñoz and I. Medina (eds.), Los grupos de interés en España: la influencia de los lobbies en la política española. Madrid: Tecnos.2016). Mayors reject local businesses as the most influential group in the local arena. Thus, Spain is framed in the European context where local power is widely distributed among institutional actors, political actors and interest groups. We would state, in theoretical terms, the existence of pluralistic patterns, although some clarifications are worthy of mention. Entrepreneurs are more influential when the mayor’s political agenda prioritizes economic development. This would reinforce the idea of an urban regime model, although the data show the mayors’ capacity to forge alliances with other local actors. In this sense, we cannot state that all Spanish cities are equal in terms of the influence of interest groups. Cities with a larger number of inhabitants are more exposed to economic dynamics and are more complex. This makes voluntary associations and local entrepreneurs more necessary for urban governance. In this sense, voluntary associations and entrepreneurs access local government through formal channels, something that the literature on interest groups’ access to decision-making poses in a different way.

In a very descriptive way, data show that mayors act as gatekeepers in the promotion of certain interests, depending on political priorities and ideological affinities. In this way, the study of urban power in Spain is highly conditioned by political factors.

Mayors’ stances on interest group influence analyzed here should be framed in a context with significant differences from the previous round of the survey administered to mayors. The deep and prolonged economic crisis was accompanied by a stage of mobilization in the main Spanish cities (15M movement) with a critical message on democratic institutions. Several political sectors addressed the topic of democratic regeneration, demanded political reforms and claimed higher citizen empowerment in decision-making. The 2014 European Parliament election provided a window of opportunity for new political parties (Ciudadanos and particularly Podemos), which transformed the map of actors that stood for the 2015 local elections. Although Podemos did not compete as a party in local elections, its leaders promoted the confluence with local social movements in the main Spanish cities. The formula proved appropriate in important cities (Madrid and Barcelona in the first place, but also Zaragoza, Cadiz, A Coruña and Santiago de Compostela). Overall, the 2015 local elections echoed the political and social aspirations for regeneration: almost half (48.7 %) of the mayors were elected for the first time, while 11.8 % of them had no prior experience at the local level. This phenomenon is relevant insofar as there is a current trend to bring control over lobbying activities in the local arena (see, for instance, the Madrid City Council.) Such discussion is beyond the goal of this article, but local transparency will undoubtedly be one of the main topics in future research on local power in Spain. We want to show some final thoughts in this regard.

Today, there is a broad debate on political corruption and fiscal transparency ( García-Quesada, Mónica, Fernando Jiménez and Manuel Villoria. 2013. “Building Local

Integrity Systems in Southern Europe: The Case of Urban Local Corruption in Spain”,

International Review of Administrative Sciences, 79 (4): 618-637. Available at:

Local governments have established a large number of participatory platforms, including

“opinion polls, surveys, focus groups, community panels, public debates, forums, citizens’

juries, round tables, invitation to coffee sessions, civic market research and policy

studies” ( Häikiö, Liisa. 2012. “From Innovation to Convention: Legitimate Citizen Participation

in Local Governance”, Local Government Studies, 38 (4): 415-435. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2012.698241.

Pike, Andy, Andrés Rodríguez-Pose and John Tomaney. 2006. Local and Regional Development. London and New York: Routledge.

It seems pertinent to note that one of the possible dimensions of change in Spanish local governments is the relationship between local governments and citizens, as well as an increase in government transparency. We believe that the publication of the mayor’s agenda (with information regarding his/her interviews and contacts and its differentiation with respect to acts of institutional representation), as well as the existence of a register of associations with information on their institutional participation, all constitute good indicators. Table 2 identifies key areas of municipal transparency in Malaga, Zaragoza, Madrid, Barcelona, and Seville.

Table 2.

Transparency in five Spanish cities (as of Jan 2017)

| City | Government meetings | Register of associations | Lobbying registers | Subsidies to associations | Advisory councils | ITA (2014)+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malaga | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | 98.8 |

| Zaragoza | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 100 |

| Madrid | Yes Includes meeting of senior officials. |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 92.5 |

| Barcelona | Yes Interlocutor not always specified. |

Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 100 |

| Seville | No Only the mayor. |

Yes | No | Yes | No | – |

| Santiago de Compostela | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 66.3 |

City governments have made extraordinary progress in the last decade, as evidenced

by the reports published by Transparency International Spain since 2008. The various

reports show the main Spanish councils are willing to improve in administrative and

financial transparency. The average score in 2008 showed a lack of commitment to transparency

(see table 3), which was alarming in terms of democratic quality, especially due to doubts related

to the management of financial resources In this regard, the 2014 report also highlights that municipal transparency is related

to the size of the municipality, insofar as large municipalities are the most transparent.

Table 3.

Transparency International Spain’s Local Government Transparency Index, 2008-2014

| Topic | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global transparency | 52.1 | 64 | 70.2 | 70.9 | 85.2 |

| Corporate portfolios | 69.6 | 71.4 | 68.1 | 72.2 | 86.3 |

| Citizens | 69 | 71.4 | 77.3 | 76.3 | 86.8 |

| Budgets | 29.1 | 49.1 | 63.8 | 71.2 | 90 |

| Contracts | 37.3 | 58.3 | 70.1 | 68.6 | 74.1 |

| Public works, environment | 48.4 | 67 | 72.2 | 77.6 | 85.8 |

| Transparency Law | – | – | – | 57.4 | 81.2 |

Source: Transparencia Internacional España (http://bit.ly/2oCyqw1).

The question is what might explain the possible variations in the level of transparency

between local governments. Local transparency seems to be determined by political

competition (partisan competition increases electoral accountability), size of municipality

(larger cities are more transparent), financial situation (cities with larger budgetary

debts are less transparent) and the local fiscal capacity (cities collecting more

taxes are more transparent) ( Esteller, Alejandro and José Luis Polo-Otero. 2010. Análisis de los determinantes de la transparencia fiscal: evidencia empírica para

los municipios catalanes. Documentos de Trabajo FUNCAS, 560/2010.Esteller and Polo-Otero, 2010; Pietrowsky, Suzanne J. and Gregg G. Van Ryzin. 2007. “Citizen Attitudes toward Transparency

in Local Government”, The American Review of Public Administration, 37 (3): 306-323. Available at:

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS[up]

This article was part of the LOGOREF project (Local Government Reform in Spain: efficiency, re-scaling and democracy) funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Science (CSO-2013-48641-C2-1-R). We are very grateful to all researchers in the LOGOREF project and to the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

Notes[up]

| [1] |

The recurrent example of this is Thatcher’s legacy on changing rules and organisational

dynamics in local governments in the United Kingdom ( Atkinson, Hugh and Stuart Wilks-Heeg. 2000. Local Government from Thatcher to Blair: The Politics of Creative Autonomy. London: Wiley.Atkinson and Wilks-Heeg, 2000). Other instances follow suit. Alba and Navarro assessed the motivations behind local

reforms in Spain from mid-1850 onwards and concluded that “reform attempts have always

been a top-down process, and policy entrepreneurs have mainly been organizationally

based in the prime minister’s office and, more recently, in the ministry of public

administration” ( Alba, Carlos and Carmen Navarro. 2011. “Administrative Tradition and Reforms in Spain:

Adaptation versus Innovation”, Public Administration, 89 (3): 783-800. Available at:

|

| [2] |

Of course, as Wollman (2012) argues, particularities are to be given special attention

when it comes to contextualising local government reforms. Local governments, although

emerging from solid roots in most European countries, mostly the Nordic ones, are

greatly embedded in multi-level structures and logics and thus they cannot escape

from national-based debates on public administration reforms in their entirety. Despite

various attempts to bring up a limited number of local government traditions in Europe,

be it as a North/South divide or as a leadership-pattern model ( Mouritzen, Poul and James Svara. 2002. Leadership at the Apex: Politicians and Administrators in Western Local Governments.

Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.Mouritzen and Svara, 2002), we cannot just tiptoe around the fact that local governments in Sweden are responsible

for hiring two-thirds of the entire public sector personnel, whereas in Spain this

figure barely stood at 23 per cent at the beginning of the last decade ( Alba, Carlos and Carmen Navarro. 2003. “Twenty Five Years of Local Government in Spain”,

in N. Kerting and A. Vetter (eds.), Reforming Local Government in Europe. Closing the Gap between Democracy and Efficiency.

Opladen: Leske and Budrich. Available at:

|

| [3] |

Local democracy includes multiple issues and discussions, ranging from the study of local policy competencies and institutional structures to issues related to political behaviour and political participation. This article is moderate in its claims. The objective here is to analyse a very specific subject, namely that of influence and transparency. |

| [4] |

It is true that Stone’s theory is critical of the pluralistic view, although it is

not as deterministic as the early elitist approaches. Stone ( Stone, Clarence. 1993. “Urban Regimes and Capacity to Govern”, Journal of Urban Affairs, 15: 1-28. Available at:

|

| [5] |

However, cities are also an ideal place for grassroots politics, which are not always articulated in the form of interest groups. In recent decades, there have been protests against a wide range of issues, with varying degrees of intensity over time. In the 1990s, there was a revitalisation of the squatter movement in Madrid, still going to the present day with the Patio Maravillas (also in Barcelona with Can Vies), as well as protests against the Prestige in several Galician cities. There was also a rise in protests of an ecological nature and in defence of the territory in many municipalities in Catalonia (Plataforma en defensa de l’Ebre) and Valencia (Salvem el Cabanyal). |

| [6] |

Although this article does not examine political protest at the local level, the emergence of political entrepreneurs from the local associations and movements deserves further research. |

| [7] |

This is a random selection of cities for informative purposes only. |

| [8] |

Local governments have established a large number of participatory platforms, including

“opinion polls, surveys, focus groups, community panels, public debates, forums, citizens’

juries, round tables, invitation to coffee sessions, civic market research and policy

studies” ( Häikiö, Liisa. 2012. “From Innovation to Convention: Legitimate Citizen Participation

in Local Governance”, Local Government Studies, 38 (4): 415-435. Available at:

|

| [9] |

In this regard, the 2014 report also highlights that municipal transparency is related to the size of the municipality, insofar as large municipalities are the most transparent. |

References[up]

|

Abney, Glenn, and Thomas P. Lauth. 1985. “Interest Groups Influence in City Policy-Making: The Views of Administrators”, Western Political Quarterly, 38: 148-161. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/448289. |

|

|

Alba, Carlos and Carmen Navarro. 2003. “Twenty Five Years of Local Government in Spain”, in N. Kerting and A. Vetter (eds.), Reforming Local Government in Europe. Closing the Gap between Democracy and Efficiency. Opladen: Leske and Budrich. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-11258-7_10. |

|

|

Alba, Carlos and Carmen Navarro. 2011. “Administrative Tradition and Reforms in Spain: Adaptation versus Innovation”, Public Administration, 89 (3): 783-800. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01886.x. |

|

|

Atkinson, Hugh and Stuart Wilks-Heeg. 2000. Local Government from Thatcher to Blair: The Politics of Creative Autonomy. London: Wiley. |

|

|

Bachrach, Peter and Morton S. Baratz . 1962. “Two Faces of Power”, American Political Science Review, 56: 947-952. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/1952796. |

|

|

Bassand, Michel and Daniel Kübler. 2001. “Introduction: Metropolization and Metropolitan Governance”, Swiss Political Science Review, 7: 121-123. |

|

|

Bellver, Ana and Daniel Kaufmann. 2005. Transparenting Transparency: Initial Empirics and Policy Applications. Washington DC: The World Bank. |

|

|

Binderkrantz, Anne. 2005. “Interest Group Strategies: Navigating between Privileged Access and Strategies of Pressure”, Political Studies, 53: 694-715. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2005.00552.x. |

|

|

Binderkrantz, Anne. 2008. “Different Groups, Different Strategies: How Interest Groups Pursue their Political Ambitions”, Scandinavian Political Studies, 31 (2): 173-200. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2008.00201.x. |

|

|

Binderkrantz, Anne, Helene H. Pedersen and Jan Beyers. 2016. “What is Access? A Discussion of the Definition and Measurement of Interest Group Access”, European Political Science, 16, 306-321. Available at: doi:10.1057/eps.2016.17. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2016.17. |

|

|

Binderkrantz, Anne, Helene H. Pedersen and Peter M. Christiansen. 2015. “Interest Group Access to the Administration, Parliament and Media”, Governance, 28 (1): 95-112. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12089. |

|

|

Botella, Joan. 1992. “La galaxia local en el sistema político espa-ol”, Revista de Estudios Políticos, 76: 145-160. |

|

|

Braun-Poppelars, Caelesta. 2007. “Resource Exchange in Urban Governance: On the Means that Matter”, Urban Affairs Review, 43 (1): 3-27. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087407302766. |

|

|

Brenner, Neil and Nik Theodore. 2002. Spaces of Neoliberalism: Urban Restructuring in North America and Western Europe. Oxford: Blackwell. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444397499. |

|

|

Browning, Rufus P., Dale R. Marshall and David H. Tabb. 2003. Racial Politics in American Cities. New York: Longman. |

|

|

Buchanan, S. 1982. “Power and Planning in Rural Areas: Preparation of the Suffolk County Structure Plan”, in M. Moseley (ed.), Power, Planning and People in Rural East Anglia. Norwich, Norfolk: Centre for East Anglian Studies, University of East Anglia. |

|

|

Castells, Manuel. 1978. City, Class and Power. London: Macmillan. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-27923-4. |

|

|

Cooper, Christopher A., Anthony J. Nownes and Steven Roberts. 2005. “Perceptions of Power: Interest Groups in Local Politics”, State and Local Government Review, 37 (3): 206-216. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X0503700303. |

|

|

Cotton, Christopher. 2012. “Pay-to-Play Politics: Informational Lobbying and Contribution Limits when Money Buys Access”, Journal of Public Economics, 96 (3-4): 369-386. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2011.11.005. |

|

|

Dahl, Robert A. 1961. Who Governs? Democracy and Power in an American City. Yale: Yale University Press. |

|

|

DeLeon, Richard E. 1992. Left Coast City: Progressive Politics in San Francisco, 1975-1991. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. |

|

|

De Socio, Mark. 2007. “Business Community Structures and Urban Regimes: A Comparative Analysis”, Journal of Urban Affairs, 29: 339-366. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2007.00350.x. |

|

|

Dür, Andreas and Gemma Mateo. 2013. “Gaining Access or Going Public? Interest Group Strategies in Five European Countries”, European Journal of Political Research, 52 (5): 660-686. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12012. |

|

|

Elkins, David R. 1995. “The Structure and Context of the Urban Growth Coalition: The View from the Chamber of Commerce”, Policy Studies Journal, 23: 583-600. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.1995.tb00536.x. |

|

|

Erlingsson, Gissur Ó. and Jörgen Ödalen. 2013. “How Should Local Government be Organised? Reflections from a Swedish Perspective”, Local Government Studies, 39 (1): 22-46. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2012.744967. |

|

|

Esteller, Alejandro and José Luis Polo-Otero. 2010. Análisis de los determinantes de la transparencia fiscal: evidencia empírica para los municipios catalanes. Documentos de Trabajo FUNCAS, 560/2010. |

|

|

Fainstein, Susan S. and Norman Fainstein. 1983. “Economic Change, National Policy and the System of Cities”, in S.S. Fainstein, N. Fainstein, R. Child Hill, D. Judd and P. Smith (eds.), Restructuring the Cities: The Political Economy of Urban Redevelopment. New York: Longman. |

|

|

Feiock, Richard C., Kent E. Portney, Jungah Bae and Jeffrey M. Berry. 2014. “Governing Local Sustainability: Agency Venues and Business Group Access”, Urban Affairs Review, 50 (2): 157-179. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087413501635. |

|

|

Fitch, Kimberly. 2007. “Water Privatisation in France and Germany: The Importance of Local Interest Groups”, Local Government Studies, 33 (4): 589-605. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930701417627. |

|

|

García-Quesada, Mónica, Fernando Jiménez and Manuel Villoria. 2013. “Building Local Integrity Systems in Southern Europe: The Case of Urban Local Corruption in Spain”, International Review of Administrative Sciences, 79 (4): 618-637. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852313501125. |

|

|

Geddes, Mike. 2009. “Marxism and Urban Politics”, in J.S. Davies and D.L. Imbroscio (eds.), Theories of Urban Politics. London: Sage Publications. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446279298.n5. |

|

|

Goldsmith, Michael. 2006. “From Community Power and Back Again?”, in H. Baldersheim and H. Wollmann (eds.), The Comparative Study of Local Government and Politics: Overview and Synthesis. Opladen: Barbara Budrich Publishers. |

|

|

Grant, Wyn. 1978. Insider Groups, Outsider Groups and Interest Group Strategies in Britain. Working Papers of Warwick University, Department of Political Science, 19. |

|

|

Guillamón, María-Dolores, Francisco Bastida and Bernardino Benito. 2011. “The Determinants of Local Governments’ Financial Transparency”, Local Government Studies, 37 (4): 391-406. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2011.588704. |

|

|

Häikiö, Liisa. 2012. “From Innovation to Convention: Legitimate Citizen Participation in Local Governance”, Local Government Studies, 38 (4): 415-435. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2012.698241. |

|

|

Hanegraaff, Marcel, Jan Beyers and Iskander De Bruycker. 2016. “Balancing Inside and Outside Lobbying: The Political Strategies of Lobbyists at Global Diplomatic Conferences”, European Journal of Political Research, 55: 568-588. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12145. |

|

|

Harding, Alan. 1995. “Elite Theory and Growth Machines”, in D. Judge, G. Stoker and H. Wolman (eds.), Theories of Urban Politics. London: Sage Publications. |

|

|

Harvey, David. 1973. Social Justice and the City. London: Arnold. |

|

|

Hunter, Floyd. 1953. Community Power Structure. A Study of Decision Makers. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. |

|

|

Jessop, Bob. 2002. “Liberalism, Neoliberalism and Urban Governance: A State-Theoretical Perspective”, in N. Brenner and N. Theodore (eds.), Spaces of Neoliberalism: Urban Restructuring in North America and Western Europe. Oxford: Blackwell. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444397499.ch5. |

|

|

Jiménez, Fernando, Mónica García-Quesada and Manuel Villoria. 2014. “Integrity Systems, Values and Expectations. Explaining Differences in the Extent of Corruption in Three Spanish Local Governments”, International Journal of Public Administration, 37 (2): 67-82. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2013.836666. |

|

|

Kübler, Daniel. 2012. “Governing the Metropolis: Towards Kinder, Gentler Democracies”, European Political Science, 11: 430-445. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2011.44. |

|

|

Lefèbvre, Henri. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell. |

|

|

Lindblom, Charles E. 1977. Politics and Markets: The World’s Political-economic Systems. New York: Basic Books. |

|

|

Logan, John and Harvey Molotch. 1987. Urban Fortunes: The Political Economy of Place. Los Angeles: University of California Press. |

|

|

Mesh, Gustavo S. and Kent P. Schwirian. 1996. “The Effectiveness of Neighbourhood Collective Action”, Social Problems, 43: 467-483. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/3096955. |

|

|

Molins, Joaquim M., Luz Muñoz and Iván Medina (eds.). 2016. Los grupos de interés en España: la influencia de los lobbies en la política española. Madrid: Tecnos. |

|

|

Mossberger, Karen. 2009. “Urban Regime Analysis”, in J. S. Davies and D. L. Imbroscio (eds.), Theories of Urban Politics. London: Sage Publications. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446279298.n4. |

|

|

Mouritzen, Poul and James Svara. 2002. Leadership at the Apex: Politicians and Administrators in Western Local Governments. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. |

|

|

Navarro, Carmen. 2014. “Immigrant Associations and Local Politics in Madrid”, in F. Velasco and M. A. Torres (eds.), Global Cities and Immigrants: A Comparative Study of Chicago and Madrid. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. |

|

|

Navarro, Carmen. 2016. “Los grupos de interés y el Gobierno local en España”, in J. M. Molins, L. Muñoz and I. Medina (eds.), Los grupos de interés en España: la influencia de los lobbies en la política española. Madrid: Tecnos. |

|

|

Navarro-Yañez, Clemente, Annick Magnier and María Antonia Ramírez-Pérez. 2008. “Local Governance as Government-Business Cooperation in Western Democracies”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32 (3): 531-547. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00816.x. |

|

|

Parés, Marc, Jordi Bonet-Martí and Marc Martí-Costa. 2012. “Does Participation Really Matter in Urban Regeneration Policies? Exploring Governance Networks in Catalonia (Spain)”, Urban Affairs Review, 48 (2): 238-271. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087411423352. |

|

|

Peterson, Paul. 1981. City Limits. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226922645.001.0001. |

|

|

Pike, Andy, Andrés Rodríguez-Pose and John Tomaney. 2006. Local and Regional Development. London and New York: Routledge. |

|

|

Pietrowsky, Suzanne J. and Gregg G. Van Ryzin. 2007. “Citizen Attitudes toward Transparency in Local Government”, The American Review of Public Administration, 37 (3): 306-323. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074006296777. |

|

|

Polsby, Nelson. 1963. Community Power and Political Theory. Yale: Yale University Press. |

|

|

Ramírez-Pérez, Antonia, Clemente Navarro-Yáñez and Terry N. Clark. 2008. “Mayors and Local Governing Coalitions in Democratic Countries: A Cross-National Comparison”, Local Government Studies, 34 (2): 147-178. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930701852245. |

|

|

Salet, Willet and Federico Savini. 2015. “The Political Governance of Urban Peripheries”, Environment and Planning C, 33: 448-456. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15594052. |

|

|

Sharp, Elaine B. 2003. “Political Participation in Cities”, in J. P. Pelissero (ed.), Cities, Politics and Policy: A Comparative Analysis. Washington, DC: CQ Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483330006.n3. |

|

|

Smith, Neil. 1991. Uneven Development: Nature, Capital and the Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell. |

|

|

Stoker, Gerry. 1995. “Regime Theory and Urban Politics”, in D. Judge, G. Stoker and H. Wolman (eds.), Theories of Urban Politics. London: Sage Publications. |

|

|

Stoker, Gerry and David Wilson. 1991. “The Lost World of British Local Pressure Groups”, Public Policy and Administration, 6 (2): 20-34. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/095207679100600202. |

|

|

Stone, Clarence. 1989. Regime Politics: Governing Atlanta, 1946-1988. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. |

|

|

Stone, Clarence. 1993. “Urban Regimes and Capacity to Govern”, Journal of Urban Affairs, 15: 1-28. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.1993.tb00300.x. |

Biography[up]

| [a] |

Doctor in Law from the University of Barcelona and Emeritus Professor of Political

Science at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. He has published extensively on

interest groups, business associations and regionalism in journals such as West European Politics; Transfer: European Review of Labor and Research and Territory, Politics, Governance, as well as in various collective works published by the Center for Political and Constitutional

Studies (CEPC), the Center for Sociological Research (CIS) and other prestigious publishers.

He is co-editor of the book Los grupos de interés en España (2016). |

| [b] |

European Doctor in Political Science from the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

He is currently a professor of Political Science at the University of Valencia. He

is a member of the COMPASSS network dedicated to the promotion of Qualitative Comparative

Analysis. His lines of research are focused on the study of interest groups in Spain,

business associations in Europe, as well as the economic side of regionalism. He is

co-editor of Los grupos de interés en España (2016) and co-autor of Análisis Cualitativo Comparado (QCA) (2017). |