The Missing Linke? Restraint and Realignment in the German Left, 2005-2017

El eslabón perdido: restricción y realineamiento dentro de la izquierda alemana, 2005-2017

ABSTRACT

This article serves two purposes: Firstly, it aims to introduce the reader to the rich and diverse party environment of the German radical left party “Die Linke”. Secondly, this paper is going to argue that the party’s apparent lack of “office-seeking” at the national level is directly relat to the requirements of its immense diversity. The issue addressed focuses on one of the aspects of the failure of cooperation between the three parties on Germany’s centre-left at the national level, and argues that besides the hesitancy of the SPD and Greens to embrace such an undertaking, Die Linke has not been ready to push for a left of centre cooperation either, due to an existential need of self-preservation and internal cohesion. This paper is based on an analysis of Die Linke’s policy debates on the issue of the economic and euro-zone crises as an example to document the large number of competing and politically diverse factions within the party that must find common policy ground and be accommodated when reaching party-wide policy positions. While this tension can be overcome by agreeing on low common denominators to voice concerns and reject government policies in an opposition role, the role as a potential junior partner in a wider “centre-left” party coalition would require far more advanced agreements on wide-ranging policy compromises with the SPD and Greens; and this would be highly divisive and threaten Die Linke’s inner-party cohesion. In response, Die Linke has continued to avoid committing to a strategy that would clearly advocate the formation of a national level “left-of-centre” party coalition to challenge the country’s centre-right government.

Keywords: cohesion; cooperation; crisis; Germany; left; Die Linke; office-seeking; party politics; radicalism.

RESUMEN

Este artículo tiene dos objetivos: en primer lugar, pretende introducir al lector en el rico y diverso ambiente del partido de la izquierda radical alemán Die Linke. En segundo lugar, este artículo argumentará que la aparente falta de orientación del partido a la “búsqueda de cargos públicos” a nivel nacional está directamente relacionada con los requisitos de su inmensa diversidad. El tema abordado se centra en uno de los aspectos del fracaso en la cooperación entre los tres partidos de centro-izquierda en Alemania a nivel nacional, y argumenta , además de la indecisión del SPD y de los Verdes para abrazar tal proyecto, Die Linke tampoco ha estado preparado para presionar en busca de una cooperación de izquierda, debido a una necesidad existencial de autopreservación y cohesión interna. Este artículo se basa en el análisis de los debates políticos de Die Linke sobre el tema de la crisis económica y de la eurozona como un ejemplo para documentar el gran número de facciones en competición y políticamente diversas dentro del partido, que tienen que encontrar una base política común y ser acomodadas cuando el partido adopta posiciones políticas. Aunque esta tensión puede superarse cuando se alcancen acuerdos para expresar inquietudes y rechazar las políticas gubernamentales en un papel de oposición, el papel de un posible socio menor en una coalición de partidos de centroizquierda más amplia requeriría acuerdos mucho más avanzados en compromisos sobre políticas de amplio alcance con el SPD y los Verdes, que serían altamente divisivos y amenazarían la cohesión interna de Die Linke. Como respuesta, Die Linke ha evitado comprometerse con una estrategia que claramente abogaría por la formación de una coalición de centro-izquierda a nivel nacional para desafiar al Gobierno de centroderecha estatal.

Palabras clave: cohesion; cooperation; crisis; Alemania; izquierda; Die Linke; consecución de cargos; política partidista; radicalismo.

CONTENTS

- Abstract

- Resumen

- INTRODUCTION

- DIE LINKE AND THE GERMAN PARTY SYSTEM

- ANALYSING AND UNDERSTANDING DIFFERING POLICY ATTITUDES AND DIFFERENTIATING DIE LINKE’s POLITICAL WINGS

- DIE LINKE AND ITS TENDENCIES AND WINGS: UNITED IN DIVERSITY?

- Forum Demokratischer Sozialismus (fds)

- Sozialistische Linke (SL)

- Emanzipatorische Linke (Ema.Li)

- Antikapitalistische Linke (AKL)

- DIE LINKE AND THE EURO-CRISIS

- References

INTRODUCTION[up]

Die Linke, as one of the three left-wing parties represented in Germany’s national parliament, holds the potential to be part of a wider “left-of-centre” party coalition that could challenge Germany’s centre-right majority –electoral arithmetic permitting–. The country’s other two well -established parties to the centre-left of the political spectrum are Germany’s “Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands” (SPD) and “Bündnis 90/Die Grünen” (Greens). Die Linke is one of the few radical left parties in Europe, compared to most fellow members in the European Parliament’s “European United Left/Nordic Green Left” party group, that under certain circumstances could potentially play a part in the formation of a national level “left-of-centre” coalition government; something Die Linke only has experience in on the country’s regional Länder level. This raises the question of why the party has failed to link up with the SPD and Greens and aim for cooperation at national level, so far.

One obvious reason for Die Linke’s perceived lack of “office-seeking” is related to

the attitude displayed by the SPD and Greens, which have publicly mostly ruled out

the possibility of seeking a “left-of-centre” party cooperation with the more “radical”

Die Linke, both for strategic electoral reasons as well as programmatic disagreements.

In fact, the SPD leadership has repeatedly accused Die Linke of being “untrustworthy

and irresponsible” in regard to the “parties” spending pledges” as well as “foreign

and defence policies”; and it has described Die Linke as “unfit and unreliable” for

any type of coalition arrangement (Stern. 2005. „Rot-rot-grüne Gedankenspiele: Überflüssig wie ein Kropf», Stern-Online, 2. August 2005. Available at:

As for the electoral and strategic prospects of Germany’s 2017 general election, all

three parties made attempts to explore ideas and find common ground for a future so-called

Red-Red-Green (R2G) coalition at the national level (Gathmann, Florian. 2016. “Großes Treffen von SPD, Linken und Grünen: Bisschen schnuppern,

bisschen stänkern”, Der Spiegel-Online, 10-16-2016. Available at:

There currently appears to be a growing sense in the literature that the onset of the financial crisis and an increasingly critical discourse towards free market economics may have caused policy ideas from parties on the radical left to “appear to move from marginality to the mainstream” (March, Luke and Daniel Keith (eds). 2016. Europe´s Radical Left: From Marginality to the Mainstream? London: Rowman and Littlefield International.March and Keith, 2016: 1) and gain traction with left parties located further towards the centre of the spectrum. There has also been a noticeable re-emergence of interest and an increase in the number of publications dealing with parties on the radical left. March and Keith (March, Luke and Daniel Keith (eds). 2016. Europe´s Radical Left: From Marginality to the Mainstream? London: Rowman and Littlefield International.2016) have gone as far as categorising such publications into four sets: (1) works that aim to provide more conceptual clarity about the ideology of parties on the radical left; (2) publications that analyse the radical left’s programmatic approaches towards Europe; (3) studies on radical left parties” involvement in government; and (4) publications that deal with the diverging electoral performances that radical left parties have experienced over recent years (March, Luke and Daniel Keith (eds). 2016. Europe´s Radical Left: From Marginality to the Mainstream? London: Rowman and Littlefield International.March and Keith, 2016: 2). This article seeks to contribute to the growing body of works on radical parties by offering a case study on Die Linke’s intellectual, programmatic and strategic responses to the crisis.

There are two key factors that can be held responsible for the lack of cooperation

amongst Germany’s parties on the centre-left. Firstly, the SPD and Green centre-left

rival parties have consistently justified their dismissal of national-level co-operation

with Die Linke by claiming that the party would be neither able, nor willing to compromise

on key-controversial policies as well as being an untrustworthy coalition partner

(Stern. 2005. „Rot-rot-grüne Gedankenspiele: Überflüssig wie ein Kropf», Stern-Online, 2. August 2005. Available at:

This then triggers the question of whether these divisions between the different constituencies within the party may be a key cause of Die Linke’s inability to engage more willingly with the idea of aiming to become part of a wider left-of-centre coalition government. And arguably, this has taken place at a time when the financial crisis might have also acted as a source of inspiration to the party’s constituencies by reinforcing commonly held key beliefs in the dysfunctionality of the neoliberal policy paradigm. This, in turn, could have been expected to bring together the different party tendencies in their quest for agreement and to formulate a coherent alternative policy agenda (Bouma, Amieke. 2016. “Ideological Confirmation and Party Consolidation”, in Luke March and Daniel Keith (eds.), Europe’s Radical Left: From Marginality to the Mainstream (pp. 133-154). London: Rowan and Littlefield.Bouma, 2016, 146) and increase the willingness to engage more positively with other parties on the left. In either case, the analysis of Die Linke’s engagement with the crisis serves as a helpful example to improve our understanding of the dynamics that have been at work when the party responded to policy challenges during that period.

In order to gain a better understanding of Die Linke’s ability to formulate coherent policies, it is helpful to analyse the creation and make-up of Die Linke and its ability to “speak with one voice”. Similarly, it is useful to recognise that the party unites a “broad house” and large variety of left and radical left political traditions that inevitably disagree over fundamental strategic and policy alignment. As an illustration, we will briefly look at the policy positions devised by Die Linke’s component wings on the (euro) crisis.

The article starts by locating Die Linke within Germany’s party-political system and identifies the large variety of actors that form the inner-party tendencies and make of the party such a “broad coalition of left wing ideology and thinking”. Afterwards, these findings offer the context for locating and comparing the party actors” policy positions on the Euro-crisis, including an analysis of the parliamentary party wings” voting behaviour in the Bundestag. Finally, and as it is highlighted in the conclusion, this analysis shows the extent of fundamental policy disagreements within the party, culminating in a party-wide movement of restraint and realignment and leading to the distinct policy positions and attitudes that prevent Die Linke’s from embracing “deeper cooperation” with the other parties on the “centre-left”; a challenge that appears even more pressing after the country’s 2017 general election outcome.

DIE LINKE AND THE GERMAN PARTY SYSTEM[up]

Die Linke emerged in its current form in 2007, after a merger of the “Electoral Alternative for Employment and Social Justice” (Wahlalternative Arbeit und Soziale Gerechtigkei–WASG) that had been formed a couple of years before by disaffected social democrats and trade unions disillusioned with the sitting SPD-led “third way” government and its labour market reforms on the one hand, and the Partei des Demokratischen Sozialismus (Party of Democratic Socialism–PDS/Linkspartei) on the other hand. The PDS had been formed from the remnants of East Germany’s Democratic Republic’s (GDR) Socialist Unity Party (SED) which, despite having been represented in the Bundestag since unification, had not risen much beyond regional electoral success in the East and the status of a “left” representation of East Germans” interests after the 1990s unification.

The merger of both parties meant not only the blending of two distinct “left” traditions, but also that Die Linke was able to widen (more or less successfully) its electoral appeal nationwide and establish itself as a political party to the left of the SPD and Greens throughout Germany (Holmes, Michael and Knut Roder. 2012. The Left and the European Constitution. Manchester: Manchester University Press.Holmes and Roder, 2012: 97). This claim is underlined by the fact that the party has ideologically been far more critical and unaccommodating of the country’s economic system by continuing to argue that “capitalism proves itself incapable of solving the most pressing problems of humanity” (Die Linke. 2013. “100 % Sozial”, Wahlprogramm zur Bundestagswahl 2013. Berlin: Die Linke.Die Linke, 2013: 46). Similarly, when looking at the Die Linke’s voting record in the Bundestag on issues related to the financial- and Euro crisis, the party has, on ideological grounds, consistently argued and voted against government initiatives. This has often placed Die Linke in stark contrast to the representatives of the other two parties from the centre-left, the SPD and Greens, which over time have been far more willing to engage with and support government policies on the crisis (see roll-call voting record on table 2).

Table 1.

German election results (in % of vote) and government coalitions, 2002–2013

| Election Year | Die Linke | Bündnis 90/ Die Grünen | SPD | CDU/CSU | FDP | AfD | Government (coalition) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 4.0 % | 8.6 % | 38.5 % | 38.5 % | 7.4 % | – | SPD / GRÜN |

| 2005 | 8.7 % | 8.1 % | 34.2 % | 35.2 % | 9.8 % | – | CDU / SPD |

| 2009 | 11.9 % | 10.7 % | 23.0 % | 33.8 % | 14.6 % | – | CDU / FDP |

| 2013 | 8.2 % | 8.4 % | 25.7 % | 41.5 % | 4.8 % | 4.7 % | CDU / SPD |

| 2017 | 9.2 % | 8.9 % | 20.5 % | 32.9 % | 10.7 % | 12.6 % |

Notes: Centre-left in bold. “Die Linke”: 2005 electoral alliance “PDS. Linkspartei” & “WSAG”; 2002 “Partei des Demokratischen Sozialismus” (below 5 % representational threshold with only two direct constituency mandates).

Source: author’s elaboration

ANALYSING AND UNDERSTANDING DIFFERING POLICY ATTITUDES AND DIFFERENTIATING DIE LINKE’s POLITICAL WINGS [up]

Before looking at Die Linke’s debates over the financial and euro crisis, it is important to recognise that the party constitutes a broad coalition of left wing ideology and thinking that reaches well beyond the party politics of its predecessors, PDS/Linkspartei and WASG. While there may be plenty of common ground between the party’s different wings when it comes to agreements over the understanding of the economic problems and their causes, these various tendencies within Die Linke can be easily differentiated, as rightly pointed out by Benjamin-Emmanuel Hoff (Hoff, Benjamin-Immanuel. 2014. Die Linke: Partei neuen Typs? Hamburg: VSA-Verlag2014: 128-135), according to their degree of fundamental opposition or willingness to engage with and believe in the ability to transform the status quo represented by the political system. Such an approach would also reach beyond the more traditional attempts to understand the party by differentiating its wings along domestic structural issue lines that reflect differences among party members and voters in the East and West of Germany, between former members of the PDS and WASG, or between reformers and traditionalists (ibid.: 124).

Another way to enhance the analysis of Die Linke could be to focus on the divisions

regarding the party goals. While salience theorists typically focus on electoral success,

parties may seek multiple goals that may or may not be mutually compatible, namely

vote-seeking, office-seeking (in conjunction with policy-seeking) or cohesion-seeking

(Steenbergen, Marco R. and David J. Scott. 2004. Contesting Europe? The salience of European integration as a party issue, in G. Marks, G. and M. G. Steenbergen, European Integration and Political Conflict. Cambridge University Press. Disponible en:

For this reason, the party decided on a leadership structure that quite successfully

offers representation to different wings of the party’s spectrum in a dual leadership

model, with co-chairing of the party leadership between Gregor Gysi and Oskar Lafontaine;

or currently Katja Kipping and Bernd Riexinger, as well as on a parliamentary party

level between Dietmar Bartsch and Sahra Wagenknecht, having become the norm. However,

this structure has come at a strategic price, namely the party is not able to follow

a very clear uncontested strategic direction. In fact, it is significant to note that

within this model the dominant wings appear to continue to promote their vision of

a more engaged coalition role, or the need for a more oppositional positioning, something

that was also reflected at Die Linke’s June 2017 party congress where the party adapted

its programme for the pending September general election, with the co-chair of the

parliamentary party, Sahra Wagenknecht, continuing to distance her party from any

possible coalition building with the SPD and Greens after the elections (Der Spiegel. 2017. „Linken-Parteitag geht auf Distanz zu SPD und Grünen“, Hamburg,

Der Spiegel-Online, 6-11-2017. Available at:

DIE LINKE AND ITS TENDENCIES AND WINGS: UNITED IN DIVERSITY?[up]

Inner-party groupings, tendencies and networks are usual features and inner-party plurality can be recognised in everyday party politics. In Germany, there is a long tradition that political parties “officially” sanction and even encourage the formation of inner-party groups that aim at influencing party discourse marked along ideological lines or that represent concerns for single topics (ecology, gay and lesbian). All German mainstream parties recognise these groups within with the help of special procedures that determine their setting up as well as rules and roles that govern their activities. As stressed by Hoff, usually “only a small number” of party activists are associated with wings or groups in regards to the overall party membership base, but “they are important in terms of accentuating and expressing positions that give orientation to ordinary individual party members” (Hoff, Benjamin-Immanuel. 2014. Die Linke: Partei neuen Typs? Hamburg: VSA-VerlagHoff, 2014: 125-6). These groups are meant to offer special focus or representation relating to issues deemed significant to ultimately advocate and help to develop a more complex party political positioning.

The inner-party groups are also tools to build platforms for inner-party political competition in regard to influence, distribution of resources and to determine the leadership personnel in positions of responsibility and power (Hoff, Benjamin-Immanuel. 2014. Die Linke: Partei neuen Typs? Hamburg: VSA-VerlagHoff, 2014: 126). And finally, party actors that play key roles and are spokespeople for those groups hold the ability to claim greater legitimacy to argue their policy positions, while being widely recognised as influential on party debates and decisions.

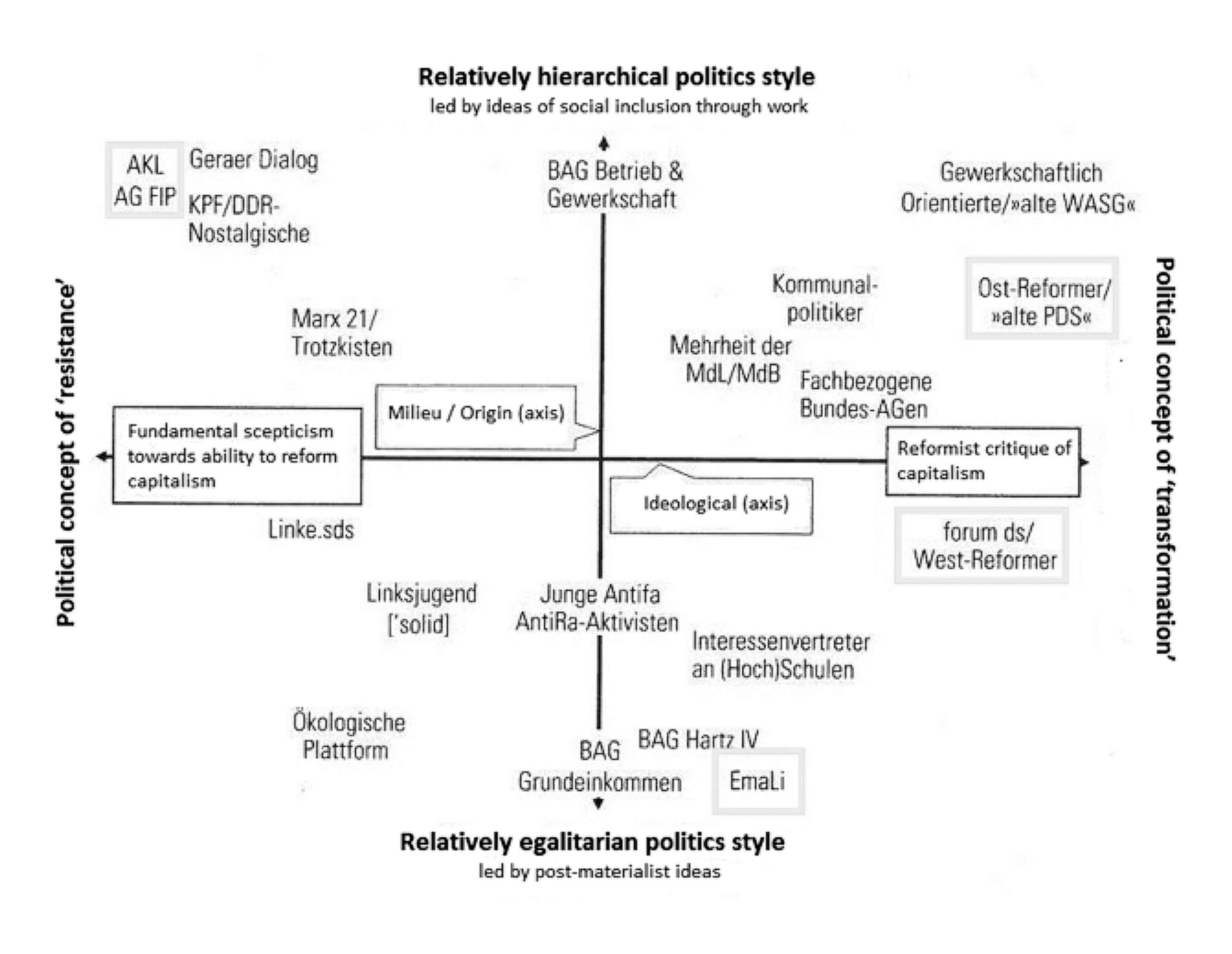

While the effects of inner-party groups described above are common to all political parties in Germany’s political spectrum, there are some features that are specific to Die Linke. The party’s members and leadership personnel are split into “Fundi” (members representing “fundamental” opposition with a lack of interest in and “resistance” to taking part in coalitions with other parties), and “Realo” (members prepared to advocate toned down “realistic” policy demands to enable coalition building and an embrace of a “transformative” approach by trading in less moderate positions). The graph below, adapted from Hoff (Hoff, Benjamin-Immanuel. 2014. Die Linke: Partei neuen Typs? Hamburg: VSA-Verlag2014: 129), is an attempt to add sophistication and a better understanding to the analysis of the different groups active in Die Linke’s party-policy-making environment. Here, the various-inner party actors, factions and wings are placed within a vertical axis that differentiates between actors that advocate a more hierarchical political style from those that focus on a more egalitarian style of politics, and within a horizontal axis that distinguishes actors who define their role in terms of putting up political “resistance” from those who believe in “transforming” the system (Hoff, Benjamin-Immanuel. 2014. Die Linke: Partei neuen Typs? Hamburg: VSA-VerlagHoff, 2014: 128-135).

Graph 1.

Position and variety of inner-party factions / actors within Die Linke

Source: adapted from Hoff, G.-I. (Hoff, Benjamin-Immanuel. 2014. Die Linke: Partei neuen Typs? Hamburg: VSA-Verlag2014) “Die Lage der Flügel und Akteure im politischen Raum der Partei Die Linke”, p. 129).

Quite revealing –but not surprising– it is the fact that the large number of functionaries, politicians at the local level, together with the majority of Die Linke party members of the Bundestag and regional Länder parliaments, or practitioners actively engaged in local politics by sitting in councils and regional administrations, as well as those working as trade union representatives (trade unionists, communal politicians, as well as reformers in the East and West) are usually receptive to a far greater degree to compromising on policies when working with representatives from other parties. Regarding inner-party groupings, this group contains many “moderates” who advocate the concept of active policy making engagement and “transformation” and are likely to sympathise with the Forum Demokratischer Sozialismus (“forum democratic socialism”–fds), later.

Hoff (Hoff, Benjamin-Immanuel. 2014. Die Linke: Partei neuen Typs? Hamburg: VSA-Verlag2014) contrasts groups that are most willing to subscribe to engagement and “transformation” with those others that represent and advocate a far more fundamental “scepticism towards the party’s ability to reform the capitalist” system, with a strong focus on system analysis and change taking prevalence over day-to-day engagement and aiming towards small-scale piecemeal improvements. In fact, those who advocate more radical and anti-capitalist goals insist on keeping a conscious and distinct distance to the more moderate on the left, namely the SPD and Greens, arguing that the aim to participate in a coalition government means selling out party principles as Die Linke would have to compromise and be likely to be forced to support policies of austerity that should be deemed unacceptable. Those on the opposing part of the inner-party policy continuum represent therefore a more fundamental call for resistance towards the prevalent political and economic system.

On this side of the spectrum one finds more ideologically driven groups, including the “Antikapitalistische Linke” (anti-capitalist left–AKL) or “Die Linke. Sozialistisch-demokratischer Studierendenverband” (socialist-democratic students” associalition–Die Linke.SDS). Somewhere between those opposites we can locate the influential broadly pro-Keynesian and trade unionist “Sozialistische Linke” (Socialist Left–SL) as well as the liberalist new-social movement “Emanzipatorische Linke” (emancipatory left–EMA.LI) group representing the other large and key inner-party tendencies within Die Linke that we will briefly look at.

Significantly, the various factions and inner-party currents within Die Linke have

not developed accidentally, but are an important and intended part of the party’s

structural make-up. In fact, the party’s constitution explicitly encourages the set

up and official recognition (Innerparteilicher Zusammenschluss–Bundessatzung §7) of

such groups by clearly determining how they may compete to influence the party’s priorities,

debates and programme (Emanzipatorische Linke/Ema.Li. 2015. “Über Ema.Li”. Available at:

In order to assess the ability of Die Linke to offer a consistent message, we need

to briefly locate the different key tendencies or “inner party pressure groups” within

the party’s inner-political spectrum (Emanzipatorische Linke/Ema.Li. 2015. “Über Ema.Li”. Available at:

Forum Demokratischer Sozialismus (fds)[up]

The “Forum Demokratischer Sozialismus” (fds) represents the “social democratic”, “reformist”

and “realo” spectrum of Die Linke which advocates much of the more moderate policy

approaches of the pre-2007 “Eastern” (Linkspartei) PDS (Forum Demokratischer Sozialismus-fds. 2007. “Gründungserklärung: Also träumen wir mit hellwacher Vernunft: Stell dir vor, es ist

Sozialismus, und keiner geht weg!” Initiative für den Demokratischen Sozialismus in

der neuen Partei DIE LINKE. Available at:

Similarly, the paper argues for the need to aim at “government responsibility” by

stressing that “a change of government will not be possible without the SPD and Greens”

and that “this means that the Die Linke needs to compromise and relinquish some of

its positions” and pre-conditions (Recht, Alexander, Paul Schäfer, Axel Troost and Alban Werner. 2015. “Aprilthesen”,

Sozialismus extra, 32. Available at:

Sozialistische Linke (SL)[up]

Similar to the Forum Sozialistische Linke (fsl), the “Sozialistische Linke” (SL) defines

itself as a moderate representative of that social democratic tradition, however not

without stressing that besides “realism” it also represents a “radical” perspective

(Sozialistische Linke-SL. 2007. Gründungserklärung: Realistisch und Radikal. Available at:

The SL’s agenda appears to be to the left of the fsl as it not only stresses the “need

for a revival of public ownership, public investment, a strong welfare state and a

socio-ecological restructuring attempt for the economy”, but also includes the “rejection

of the current EU treaties” linked to the “demand for a new beginning to the EU”,

with the SL’s ultimate aims remaining the “overthrowing of capitalism” in a self-proclaimed

“realistic and radical” manner (Sozialistische Linke-SL. 2007. Gründungserklärung: Realistisch und Radikal. Available at:

This party wing is frequently depicted as representing the “new” part of the party

(after its merger and re-foundation in 2007) as most of the SL’s founding members

came from the “West” German trade union movement and WASG. However, the SL also encompasses

members from a more “Trotskyite” group called “marx21” that has had some effect on

the programmatic positioning of the SL and represents a more system-sceptic approach

by opposing, for example, those party members that are sympathetic towards embracing

participation in coalition governments (Marx21. 2015. “Bielefelder Parteitag: Klare Kante statt trüber Brühe”, Marx21, 6-9-2015. Available at:

Emanzipatorische Linke (Ema.Li) [up]

The “Emancipatory Left” advocates a “liberal” approach to society and promotes ideas

of “radical democratic emancipatory” nature with the aim of serving as an “inclusive

discussion forum within as well as outside the party” to assist the development of

a “new left” (Emanzipatorische Linke/Ema.Li. 2015. “Über Ema.Li”. Available at:

Antikapitalistische Linke (AKL)[up]

On the more radical inner-party spectrum to the left stands the “anti-capitalist left”

that advocates a more fundamentalist opposition role rejecting participation of Die

Linke in any coalition government (Antikapitalistische Linke-AKL. 2013. Über die AKL. Available at:

For that reason, the AKL has identified numerous red lines (“non-negotiable positions”) that would have to be met by the SPD and Greens before the group could support being part of any government coalition. In the matter of the Euro crisis, these include, for example, a rejection of both the “fiscal compact” and the “Troika’s bailout conditions” as well as “any bank rescue plans”. In addition, the AKL insists that that there cannot be any German military involvement abroad, demands an end to privatisation, rejects social cuts, and demands an end to the use of nuclear and coal power (id). Clearly, the attitude towards any cooperation with other parties on the left as part of a coalition stands in stark contrast to the beliefs and strategies advocated by the fds.

Not to be left out, another larger and recognised inner-party group on the left that

must be mentioned is called the Communist Platform (Kommunistische Plattform–KPF).

This group is composed of “communists” who aim to “preserve and develop Marxist ideas”

within the party (Die Linke. 2011. “Kommunistische Plattform der Partei Die Linke“. Available at:

The “Communist Platform” has not been particularly engaged with the details of the

Euro crisis as its members reject outright the wider workings of the current economic

system, and for that reason are generally more engaged in focusing on broader ideological

debates. For that reason, while mentioned, the activities of that wing will not be

considered any further in this article. Similarly, there are numerous other smaller

wings and tendencies, many of which are mentioned in Hoff’s table of positions of

inner-party factions and actors within Die Linke, but which do not require further

mention for the purposes of this paper (Hoff, Benjamin-Immanuel. 2014. Die Linke: Partei neuen Typs? Hamburg: VSA-VerlagHoff, 2014: 129). In fact, numerous smaller groups such as the AKL or “Geraer Dialog/Sozialistischer

Dialog” hold more of a fringe status and have complained in the past that their policy

documents are frequently blocked at party conventions and not permitted to proceed

to the party’s programmatic negotiation stages (Sozialismus Info. 2015. “Gysis ´Vermächtnis´ und die Zukunft der Linken”, Sozialistische Alternative (SAV), 10. Available at:

What remains clear from the analysis above is the fact that Die Linke contains a large spectrum of left tendencies that are mostly located well beyond the centre-left policy ideas of the SPD and Greens. Differences in the perceived role of Die Linke either as part of a transformative coalition of progressive parties on the left or instead as an actor to resist engagement and protest against the convention of the established political and economic conventions are to be expected to a certain degree. In the same way the party’s groups reflect the wider left spectrum between “ideas of economic growth” and “social inclusion through work” as well as more “post-materialist” and environmental concerns. This brings us back to our starting point: that Die Linke itself represents a coalition of different more or less radical left wing political belief systems and strategies for change, with many ideological divisions going much further back than the re-foundation of Die Linke in 2007. In fact, groups often represent conflicts and ideological divisions among left ideologies that reach back to the early 20th century. Or in the words of Benjamin-Immanuel Hoff, disagreements reassemble the disagreements and political “evergreens” of Germany’s wider Left (Hoff, Benjamin-Immanuel. 2014. Die Linke: Partei neuen Typs? Hamburg: VSA-VerlagHoff, 2014: 134).

DIE LINKE AND THE EURO-CRISIS[up]

After the brief review of the wide spectrum of left- and radical left- policy approaches represented within the party, it is helpful to gain some understanding of the differing views about the crisis among the party’s leadership personnel as well as how the party’s policies are expressed in its programme.

Contrasting Dr Axel Troost’s and Dr Sahra Wagenknecht’s attitudes on this matter gives a good example as both are prominent finance policy experts within the party who have published widely on the financial and euro crisis in the form of books, articles, and policy programmes. Moreover, Sahra Wagenknecht has receiving a great deal of attention due to her frequent appearances on German prime time TV politics talk shows. Both politicians somehow embody the difference between the party’s more moderate Eastern wing and the more Western sceptic policy one, commonly represented by the party’s regional party associations. Axel Troost comes originally from pre-unification West Germany and represents more moderate social democratic policy convictions, which has allowed him to win his nomination on a moderate regional East German party list from Saxony in the East, while the East German Sahra Wagenknecht, who is commonly associated with the more radical wing of the party, has been given her parliamentary mandate by a West German party association from North Rhine-Westphalia that is generally deemed to be part of the more radical side of the party’s political spectrum.

It is also important to emphasise that Axel Troost has in the past stressed that the differences in opinion between Die Linke’s different wings are a common and necessary part of inner-party democracy that aids the fleshing out of official policy programmatic positions. In fact, Troost goes as far as insisting that the degree of disagreements to be found in Die Linke are in line with internal divisions also found in other German parties. He argues that the differences in the analysis and agreements of the causes of policy challenges, such as those arising from the financial and euro crisis, are surprisingly similar amongst the different groups represented in Die Linke, while the most fundamental disagreements among them have to do with the strategic direction and the most suitable policy solutions to deal with identified policy challenges (Troost, Axel. 2015a. Authors’ interview with Dr Axel Troost. Leipzig.Troost, 2015a). This would mean that Troost and Wagenknecht may advocate substantially different strategies on how to deal with the financial and euro crisis, but they would share an understanding of the structural issues and flaws of the Economic and Monetary Union system as well as their analysis of the role of the German government within it. Their agreement is apparent in the party’s programmatic compromises on the issue, as summed up well in the 2013 general election programme “100 % Sozial” (Die Linke. 2013. “100 % Sozial”, Wahlprogramm zur Bundestagswahl 2013. Berlin: Die Linke.Die Linke, 2013).

In the run-up to the September 2013 election, the Euro crisis was perceived in Germany

to have reached its height; they reason why Die Linke invested a great deal in covering

the issue in the party’s manifesto. As a result, the programme offers a good and detailed

overview of Die Linke’s broader understanding of the crisis and how it should be dealt

with. The 100-page-strong election manifesto made some very strong points about blaming

the crisis on the EMU’s systemic economic imbalances, but explicitly turned it into

a more general critique of the capitalist system (Münchau, Wolfgang. 2013. “Rot-Rot-Grün ist die beste Lösung für Europa“, Spiegel-Online,

8-28-2013. Available at:

In addition, the programme accused Angela Merkel’s government of having attempted to “[...] reinterpret the financial crisis as a sovereign debt crisis” and thereby “confusing cause with effect” (ibid.: 46). Furthermore, the manifesto reproached the Merkel government for having blamed the crisis on the countries that were suffering most under the debt and thereby distracting from what the party views as the “real causes” of the crisis, namely the facilitation of bank bailouts. The latter were viewed not only as responsible for the unsustainably high sovereign debt levels of some countries but also as part of a system that had been ultimately rigged to benefit German banks (ibid.: 47). This interpretation of the crisis indicates a clear conviction regarding a strong crisis narrative that could clearly be agreed upon by the different groups present within Die Linke. And as a result, this was reflected by Die Linke’s voting patterns on legislation in the Bundestag, where Die Linke’s representatives consistently rejected and voted against measures put forward by the government on issues such as the “European Stability Mechanism”, the “Fiscal Compact” and bailout packages as tools of crisis management (ibid.: 46).

Appearing certain about its macroeconomic analysis of the crisis, the party pledged

considerably radical solutions entrenched in the party’s ideological underpinnings

(Münchau, Wolfgang. 2013. “Rot-Rot-Grün ist die beste Lösung für Europa“, Spiegel-Online,

8-28-2013. Available at:

As for the European Union integration, the programme states the party’s demand for a “re-foundation of the European Union”, which is criticised for having become neo-liberal in orientation since the Maastricht Treaty. And while the programme clearly states that “EMU is being viewed as containing huge errors in its current setup”, Die Linke did stress that it did “not want an end to the Euro” (Die Linke. 2013. “100 % Sozial”, Wahlprogramm zur Bundestagswahl 2013. Berlin: Die Linke.Die Linke, 2013: 49). Above all, it remains clear that despite substantial disagreements between the different tendencies within the party on how to engage with the political system, there is a substantial agreement within Die Linke on the interpretation of the causes of the crisis.

Similarly, disagreements in discourse among the different Die Linke factions did not

always or necessarily translated into votes. For example, Sahra Wagenknecht had been

arguing that reform of the “Eurozone-dominated neo-liberal austerity mainstream” wasn’t

currently possible (Troost, Axel. 2015b. “Raus aus dem Euro?”, Die Linke, 8-25-2015. Available at:

Using the example of key “roll-call” votes on the Euro mechanisms and bailouts, Die

Linke’s MPs –from all the different wings of the party (fds, SL & Ema.Li)– have thus

consistently voted together (see table 2). While this should be expected, considering

that Die Linke MPs were voting on legislation proposed by a Christian Democrat-led

government and playing its role as an opposition party on the left, what may be even

more revealing is the way Die Linke’s MPs voted distinctly differently to its potential

partners on the centre-left, the SPD and Greens. Die Linke voted alongside the SPD

only 2 out of 14 times, and together with the Greens only 5 times out of 14. In contrast,

the Greens voted alongside the SPD at least 10 out of 14 times (Bundestag. 2016. Plenum-Abstimmungen. Available at:

This indicates that, while Die Linke may appear divided and it is composed of a substantial group of differing wings that hold distinctive ideological policy principles (also see graph 1 2), Die Linke’s parliamentary party has acted and voted with exceptional unity in the Bundestag in terms of policy issues and understandings related to the crisis and debated in the Bundestag. This shows that, in the case of the Euro crisis, Die Linke’s policy output has been surprisingly consistent, despite its different wings and ongoing inner-party debates. However, it must be stated that the party voted consistently against the government with such votes lending themselves to do so, with the anti-systemic positions certainly partly explaining such a degree of party unity. However, a more strategic and coordinated approach with the other two parties on the centre-left, SPD and Greens, would have been possible so to close ranks and invest in the possibility of future cooperation. But this option was clearly not embraced.

Table 2.

Voting patterns of key representatives from different wings of Die Linke: Bundestag’s “roll-call” on Euro-/Financial Crises legislation. Linke, Greens, SPD and overall (2008-2016)

| Date | Voting Issue (roll-call vote) on government laws / initiatives dealing with Euro-/ Financial Crisis (no translation needed as emphasis on voting patterns) |

Troost

(fds) |

Wagenknecht

(SL/AKL) |

Kipping (Ema/Li) |

“Die Linke”

Yes/No/Abst. |

“Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen”

Yes/No/Abst. |

“Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD)”

Yes/No/Abst. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19.08.2015 | Gewährung eines 86 Mrd. Euro Kreditpakets für Griechenland 3 | No | No | No | 0 / 45 / 7 N | 52 / 1 / 8 Y | 171 / 4 / 0 Y |

| 17.07.2015 | Stabilitätshilfe zugunsten Griechenlands | No | No | No | 0 / 53 / 2 N | 23 /2 /33 N | 175 /4 / 0 Y |

| 27.02.2015 | Finanzhilfen für Griechenland 2 | Yes | Abstention | Yes | 41 / 3 / 10 Y | 60 / 0 / 0 Y | 178 / 0 / 0 Y |

| 18.04.2013 | Finanzhilfen für Zypern (ESM) | No | n / a* | No | 0 / 72 / 0 N | 62 / 0 / 1 Y | 122/10/10 Y |

| 30.11.2012 | Finanzhilfen für Griechenland 1 | No | No | No | 0 / 67 / 0 N | 65 / 0 / 1 Y | 111/11/9 Y |

| 19.07.2012 | Bankenhilfe für Spanien (EFSF) | No | No | No | 0 / 60 / 0 N | 54 / 1 / 10 Y | 118/14/2 Y |

| 29.06.2012 | Dauerhafter Euro-Rettungsschirm ESM | No | No | No | 0 / 71 / 0 N | 65 / 1/ 0 Y | 128/8/4 Y |

| 29.06.2012 | Fiskalpakt | No | No | No | 0 / 71 / 0 N | 65 / 1/ 0 Y | 138/ 1 / 4 Y |

| 27.02.2012 | Zweites Rettungspaket für Griechenland | No | No | n / a* | 0 / 66 / 0 N | 85 / 4 / 1 Y | 129/ 7 / 1 Y |

| 29.09.2011 | Euro-Stabilisierungsfonds EFSF | No | No | No | 0 / 70 / 0 N | 67 / 1 / 0 Y | 141/ 1 / 1 Y |

| 21.05.2010 | Euro-Rettungsschirm | No | No | No | 0 / 76 / 0 N | 0 / 0 / 63 N | 0 / 1 / 128 N |

| 07.05.2010 | Notkredit für Griechenland | No | No | No | 0 / 67 / 0 N | 61 / 0 / 5 Y | 4 / 0 / 134 N |

| 20.03.2009 | Stabilisierung des Finanzmarktes (Finanzmarkt stabilisierungsergänzungsgesetz- FMStErgG) | No | (-)* | No | 0 / 47 / 0 N | 0 / 0 / 43 N | 191 / 1 / 0 Y |

| 17.10.2008 | Maßnahmenpakets zur Stabilisierung des Finanzmarktes (Finanzmarkt stabilisierungsgesetz -FMStG) | No | (-)* | No | 0 / 50 / 0 N | 0 / 48 / 0 N | 207 / 0 / 0 Y |

Notes: Roll-call voting in the German Bundestag on government-introduced legislation on the Financial- and Euro crisis (2008-2016) (* n / a = not present during voting) (-) = not member of Bundestag). In case of a majority of “No” votes or abstentions (failing to support government initiative) = marked in red as “No”.

Source: author’s elaboration – Plenum – Namentliche Abstimmungen, 16, 17. & 18. Wahlperiode

(Bundestag. 2016. Plenum-Abstimmungen. Available at:

Conclusion[up]

Judging by the evidence of Die Linke’s diverse composition and need for party cohesion, we can conclude that the party is being constrained from more enthusiastically and strategically embracing an “office-seeking” “left-of-centre” cooperation with the SPD and the Greens at the national level. Thus, in spite of the fact that only a successful cooperation between the three parties could challenge Germany’s centre-right government majority, there are two good reasons why this cooperation has not yet materialised.

Firstly, there is the unwillingness to cooperate with, and even dismissal of, Die

Linke by the SPD and Greens, that refuse to embrace Die Linke as a possible partner

for strategic as well as programmatic reasons (Stern. 2005. „Rot-rot-grüne Gedankenspiele: Überflüssig wie ein Kropf», Stern-Online, 2. August 2005. Available at:

Die Linke’s composition of programmatically and ideologically highly diverse groups which represents a wide ideological continuum reaching from social democrats (fds and SL) to anti-system groups opposed to capitalism (AKL and KPF) means that Die Linke’s balance of factions needs to be partly sustained. Therefore, keeping this “coalition” of factions is an implicit precondition for safeguarding the survival of the party; and this can only be achieved by mobilising sufficient numbers of activists as well as a critical mass of voters to keep Die Linke politically relevant by attracting sufficient electoral support to reach the 5 % minimum threshold that is required to win parliamentary representation in Germany. In other words, Die Linke’s restrictive policy choices of avoiding cross-party cooperation with the SPD and Greens, something that remains highly contested internally, may well be of existential importance to the party, as it aims to preserve cohesion and essentially prioritises the very party survival. For this reason, Die Linke has been understandably hesitant to commit itself to any “centre-left” coalition building with all the consequences that this would entail in the face of having to substantially compromise on policy positions with the far more moderate centre-left SPD and Greens. For example, in the case of the positions adopted and expressed during Bundestag voting on the crisis, Die Linke could not have sustained such a degree of policy rejection, but instead would have had to display substantial willingness to engage and compromise, even more so, if it had had to play a part in any centre-left coalition government.

However, calling Die Linke a “missing link” on the left would be unfair, as this would

indicate that the party has failed to engage in policy debates and position itself.

This has clearly not been the case, particularly when looking at the sheer volume

of work, programmes and publications through which party members and supporters have

contributed to the debate on the crisis from all sides of the party’s political spectrum.

In addition to the party’s engagement in the Bundestag (Der Spiegel. 2015. „Datenlese: Opposition im Bundestag Wir hätten da mal 1313 Fragen“,

Hamburg, Der Spiegel-Online, 4-23-2015. Available at:

If Die Linke should, one day, decide to become part of a wider German government to the left (SPD and Greens being willing, as well as electoral majorities and interparty discourse permitting), international interest can be expected to surge in the party’s policy debates. Instead of representing a missing link, Die Linke continues to hold the potential to ultimately transform itself into a coalition partner, if leading members decide “in favour of moving towards the option of taking on government responsibility” (Lucke, Albrecht von. 2015. “Einheit in der Spaltung: Die Linkspartei nach Gysi”. Berlin: Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik, 7 / 2015: 5-8Lucke, 2015: 8) and the various party factions start believing that their party could make a real difference as a result of Die Linke being able to implement sufficient amounts of their policy ideas as part of a national level centre-left coalition with the SPD and Greens.

References[up]

|

Antikapitalistische Linke-AKL. 2013. Über die AKL. Available at: http://www.antikapitalistische-linke.de/?page_id=40. |

|

|

Antikapitalistische Linke-AKL. 2014. “Kapitalismus bedeutet Krieg, Umweltzerstörung und Armut!“, Berlin: AKL-Broschüre-2014. Available at: http://www.antikapitalistische-linke.de/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/AKL-Brosch%C3%BCre-2014.pdf. |

|

|

Bundestag. 2016. Plenum-Abstimmungen. Available at: http://www.bundestag.de/bundestag/plenum/abstimmung/16wp (16. Wahlperiode). http://www.bundestag.de/bundestag/plenum/abstimmung/grafik (17. & 18. Wahlperiode). |

|

|

Bonk, Julia, Katja Kipping and Caren Lay. 2006. “Freiheit und Sozialismus. Let’s make it real: Emanzipatorische Denkanstöße für die neue linke Partei“, Ema.Li, April 2006. Available at: https://emanzipatorischelinke.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/freiheit-und-sozialismus-lets-make-it-real.pdf. |

|

|

Bouma, Amieke. 2016. “Ideological Confirmation and Party Consolidation”, in Luke March and Daniel Keith (eds.), Europe’s Radical Left: From Marginality to the Mainstream (pp. 133-154). London: Rowan and Littlefield. |

|

|

Candeias, Mario. 2010. „Ein fragwürdiger Weltmeister: Deutschland exportiert Arbeitslosigkeit“, Reihe Standpunkte, Juni 14/ 2010. Available at: http://www.rosalux.de/fileadmin/rls_uploads/pdfs/Standpunkte/Standpunkte_14-2010.pdf. |

|

|

Chiocchetti, Paolo. 2017. The Radical Left Party Family in Western Europe, 1989-2015. Abingdon: Routledge. |

|

|

Der Spiegel. 2015. „Datenlese: Opposition im Bundestag Wir hätten da mal 1313 Fragen“, Hamburg, Der Spiegel-Online, 4-23-2015. Available at: http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/bundestag-so-arbeiten-die-gruenen-und-die-linken-a-1026871.html. |

|

|

Der Spiegel. 2017. „Linken-Parteitag geht auf Distanz zu SPD und Grünen“, Hamburg, Der Spiegel-Online, 6-11-2017. Available at: http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/linke-sahra-wagenknecht-geht-auf-distanz-zu-spd-und-gruenen-a-1151594.html. |

|

|

Die Linke. 2011. “Kommunistische Plattform der Partei Die Linke“. Available at: https://www.die-linke.de/partei/zusammenschluesse/kommunistische_plattform_der_partei_ die_linke/. |

|

|

Die Linke. 2013. “100 % Sozial”, Wahlprogramm zur Bundestagswahl 2013. Berlin: Die Linke. |

|

|

Die Linke NRW. 2015. “Politische Strömungen”. Available at: http://www.dielinke-nrw.de/nc/partei/arbeitskreise/politische_stroemungen/. |

|

|

Emanzipatorische Linke/Ema.Li. 2015. “Über Ema.Li”. Available at: https://emanzipatorischelinke.wordpress.com/uber-uns/ |

|

|

Forum Demokratischer Sozialismus-fds. 2007. “Gründungserklärung: Also träumen wir mit hellwacher Vernunft: Stell dir vor, es ist Sozialismus, und keiner geht weg!” Initiative für den Demokratischen Sozialismus in der neuen Partei DIE LINKE. Available at: http://forum-ds.de/?page_id=351. |

|

|

Forum Demokratischer Sozialismus-fds. 2015. “Erklärung zum Strömungsratschlag vom 12. Juni 2015 in Berlin - Gemeinsame Erklärung der Teilnehmenden des Forum Demokratischer Sozialismus (fds), der Sozialistischen Linken (SL) und der Emanzipatorischen Linken (Ema.Li)”. Available at: http://forum-ds.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Erkl %C3 %A4rung-zum-Str%C3%B6mungsratschlag.pdf. |

|

|

Gathmann, Florian. 2016. “Großes Treffen von SPD, Linken und Grünen: Bisschen schnuppern, bisschen stänkern”, Der Spiegel-Online, 10-16-2016. Available at: http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/grosses-rot-rot-gruen-treffen-r2g-in-berlin-a-1116976.html. |

|

|

Holmes, Michael and Knut Roder. 2012. The Left and the European Constitution. Manchester: Manchester University Press. |

|

|

Hoff, Benjamin-Immanuel. 2014. Die Linke: Partei neuen Typs? Hamburg: VSA-Verlag |

|

|

Höll, Susanne. 2012. „Koalitionsaussage für Bundestagswahl 2013 SPD-Chef Gabriel schließt Bündnis mit Linken“, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 1-25-Januar 2012. Available at: http://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/koalitionsaussage-fuer-bundestagswahl-spd-chef-gabriel-schliesst-buendnis-mit-linken-aus-1.1266407. |

|

|

Korte, Jan and Dominic Heilig. 2015. “Im freien Fall”, die Tageszeitung, 7-7-2015. Available at: http://taz.de/fileadmin/static/pdf/Linke-und-Gruene-Paper.pdf. |

|

|

Lucke, Albrecht von. 2015. “Einheit in der Spaltung: Die Linkspartei nach Gysi”. Berlin: Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik, 7 / 2015: 5-8 |

|

|

Marx21. 2015. “Bielefelder Parteitag: Klare Kante statt trüber Brühe”, Marx21, 6-9-2015. Available at: http://marx21.de/bielefelder-parteitag-klare-kante-statt-trueber-bruehe/. |

|

|

March, Luke and Daniel Keith (eds). 2016. Europe´s Radical Left: From Marginality to the Mainstream? London: Rowman and Littlefield International. |

|

|

Münchau, Wolfgang. 2013. “Rot-Rot-Grün ist die beste Lösung für Europa“, Spiegel-Online, 8-28-2013. Available at: http://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/wolfgang-muenchau-ueber-das-wahlprogramm-der-linken-a-919067.html. |

|

|

Recht, Alexander, Paul Schäfer, Axel Troost and Alban Werner. 2015. “Aprilthesen”, Sozialismus extra, 32. Available at: http://www.sozialismus.de/fileadmin/users/sozialismus/pdf/Sozialismus_extra_2015-06_Web.pdf. |

|

|

Sozialistische Linke-SL. 2007. Gründungserklärung: Realistisch und Radikal. Available at: http://www.sozialistische-linke.de/ueber-uns. |

|

|

Sozialistische Linke-SL. 2014a. “Nach dem Europaparteitag-DIE LINKE kämpft für ein anderes Europa”, Stellungnahme des BundessprecherInnenrates, 2-23-2014. Available at: http://www.sozialistische-linke.de/politik/debatte/969-bsr-nach-ept. |

|

|

Sozialistische Linke-SL. 2014b. “Die SL zum Berliner Parteitag der LINKEN”, Stellungnahme des BundessprecherInnenrates, 5-15-2014. Available at: http://www.sozialistische-linke.de/politik/debatte/992-sl-bpt-berlin-2014. |

|

|

Sozialismus Info. 2015. “Gysis ´Vermächtnis´ und die Zukunft der Linken”, Sozialistische Alternative (SAV), 10. Available at: https://www.sozialismus.info/2015/06/gysis-vermaechtnis-und-die-zukunft-der-linken/. |

|

|

Steenbergen, Marco R. and David J. Scott. 2004. Contesting Europe? The salience of European integration as a party issue, in G. Marks, G. and M. G. Steenbergen, European Integration and Political Conflict. Cambridge University Press. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511492013.010. |

|

|

Stern. 2005. „Rot-rot-grüne Gedankenspiele: Überflüssig wie ein Kropf», Stern-Online, 2. August 2005. Available at: http://www.stern.de/politik/deutschland/rot-rot-gruene-gedankenspiele--ueberfluessig-wie-ein-kropf--3300542.html. |

|

|

Tagesspiegel. 2016. „Bundestagswahl 2017: SPD und Linke loten Bedingungen für Rot-Rot-Grün aus“, Der Tagesspiegel, 7-10-2016. Available at: http://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/bundestagswahl-2017-spd-und-linke-loten-bedingungen-fuer-rot-rot-gruen-aus/13854638.html. |

|

|

Troost, Axel. 2015a. Authors’ interview with Dr Axel Troost. Leipzig. |

|

|

Troost, Axel. 2015b. “Raus aus dem Euro?”, Die Linke, 8-25-2015. Available at: http://www.die-linke.de/nc/die-linke/nachrichten/detail/zurueck/nachrichten/artikel/raus-aus-dem-euro/. |

Biography[up]

| [a] |

Senior Lecturer and BA Politics Course Leader at Sheffield Hallam University. He has

published on the politics and political economy of European integration, party politics

with a focus on Germany and the UK. And he is the author of Social Democracy and Labour Market Policy (2003); and co-editor (with Holmes, M.) of The Left and the European Constitution (2012) and The European Left and the Crisis (forthcoming 2018). |