Democratizing participation through feminisms.

The role of feminist subaltern counterpublics in the expansion of the Basque public

sphere

Democratizando la participación a través del feminismo.

El rol de los contrapúblicos subalternos feministas en la expansión de la esfera pública

vasca

RESUMEN

This article aims to understand the limits on the expansion of the public space that is occurring through democratic innovations, and to investigate strategies for overcoming these limits. With an approach rooted in standpoint epistemology, this article studies the participation experiences of sixteen women belonging to a feminist subaltern counterpublic in fifteen apparatuses in the Autonomous Region of the Basque Country. The study considers that this expansion of the public space has taken place with three limits, related to the de-legitimisation of the private, the undervaluation of relational aspects and the naturalization of a universal idea of participation. Opposing this, the article states that the practice of counterpublics facilitates greater inclusion in the designs of democratic innovations due to those parallel publics’ subaltern position in the public space.

Palabras clave: dispositivos de innovación democrática; teoría feminista; epistemología del punto de vista; Nancy Fraser.

ABSTRACT

Este artículo tiene como objetivo comprender los límites con los que se está produciendo la ampliación del espacio público a través de mecanismos de innovación democrática, así como indagar sobre las estrategias para afrontarlos. Con un enfoque basado en la «epistemología del punto de vista», se estudian las experiencias de participación de dieciséis mujeres que forman parte de un contrapúblico subalterno feminista en quince mecanismos de la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco. La investigación plantea que esta ampliación del espacio público se está llevando a cabo con tres límites relacionados con la deslegitimación de lo privado, la minusvaloración de lo relacional y la naturalización de una idea universal de participación. Frente a esto, el artículo afirma que la práctica de los contrapúblicos facilita una mayor inclusividad en los diseños de innovación democrática por su posición subalterna en el espacio público.

Keywords: democratic innovations; feminist theory; standpoint epistemology; Nancy Fraser.

SUMARIO

- Resumen

- Abstract

- INTRODUCTION

- Feminist political theory and the expansion of the public sphere through democratic innovations

- Subaltern Counterpublics And Democratic Expansion

- CONTEXT AND DATA COLLECTION

- HOW DO THE FEMINIST COUNTERPUBLICS BUILD DEMOCRACY?

- Becoming counterpublic: Revaluation of the public, the importance of emotion and the search for models

- The consequences of feminist subaltern counterpublics: Extension of the notion of participation and changes in structuring the apparatus

- CONCLUSION

- Acknowledgements

- Notas

- References

INTRODUCTION[Subir]

In most societies in the world considered to be democratic, an expansion of the public

sphere is occurring through deliberative, participatory and community development

procedures that will be referred to in this article broadly as “democratic innovations”

(Smith, Graham. 2009. Democratic innovations. Designing institutions for citizen participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Disponible en:

Those tackling the matter of democratic innovations (hereinafter DIs) from a critical

viewpoint agree in indicating at least two closely related points: first, that participation

and deliberation have a gender, a race, an age, a sexuality and a dominant class (Pateman, Carole. 1970. Participation and democratic theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Disponible en:

The identification of this exclusive nature of democratic expansion through innovation

processes has provoked, often with a deductive logic[3], the development of a range of practical and theoretical strategies that seek to

guarantee inclusion by recognition, the redistribution of power and the representation

of excluded social groups. Thus, on the one hand, the most empirically developed measures

in the literature range from working on deliberation through “enclaves” (Mansbridge, Jane. 1996. “Using power/fighting power: The polity,” en Seyla Benhabib,

Democracy and difference: Contesting boundaries of the political. Princeton: Princeton University Press.Mansbridge, 1996: 57; Karpowitz, Christopher, Raphael Chad y Allen Hammond. 2009. “Deliberative democracy

and inequality: Two cheers for enclave deliberation among the disempowered”Politics and Society 37, 4: 576- 615. Disponible en:

Although from the study of any of these practical measures or theoretical proposals it is possible to know more about how to find the cracks that can be exploited for expanding the public space through innovation, the deductive logic used for their design might enclose the researcher in circular thinking[4] in which it becomes difficult to listen directly to those who experience exclusion in the first person, thus hindering identification, from that person’s point of view, of the challenges faced by the DI and possible strategies for overcoming them. Therefore, in order to improve our understanding both of these limits and the strategies to overcome them, it is important to open up “access” by means of the study of the theoretical proposals and practical measures that facilitate inductive knowledge.

Among these strategies, this article draws on the “subaltern counterpublics” offered

by Nancy Fraser for two reasons. Firstly, because they were offered with the explicit

goal of responding to an overly narrow notion of public sphere, a notion that will

be also dealt with in this article. Secondly, because their analysis allows an inductive,

experience-based and sensitive approach to the structures of power (race, gender or

class among others) that intersect in the oppression experienced by those who are

excluded from DIs (Martínez-Palacios, Jone. 2016. “Equality and diversity in democracy. How can we democratize

inclusively?”, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 35 (5/6): 350-63. Disponible en:

With this in mind, this article enquires about the possibilities offered by these counterpublics when it comes to combating the complexity of the forms of exclusion that occur in some of these apparatuses being used to expand the public sphere. It examines the potential contribution of feminist subaltern counterpublics in ensuring fuller and broader participation in societies considered democratic and with democratic innovations already in place.

To do so, and applying an inductive research strategy with a dialectic perspective based on action research, it focuses on the point of view and experience of sixteen diverse women who belong in different ways to a feminist counterpublic in the Autonomous Region of the Basque Country. Specifically, the research is built on life histories that concentrate on their participative experience, two focus groups and the direct observation of two DI spaces.

The article is divided into four main sections. In the first one, after introducing the perspectives of Critical Theory regarding the enlargement of the public space that is currently occurring through democratic innovation apparatuses, an explanation is given of the theoretical context in which Nancy Fraser’s counterpublic contribution is situated. The second section sets out the context and methodological procedure of the research on which this article is based. The third one examines the way in which counterpublics build democracy. This is done by interpreting the data obtained from the fieldwork and in order to provide some answers to the above stated questions. The fourth and last section concludes that feminist subaltern counterpublics operate like large-scale “rooms of one’s own”; these facilitate thinking about democracy in more inclusive terms by means of mobilizing a discursive framework which focuses on the demand for greater social justice based on recognition and redistribution.

Feminist political theory and the expansion of the public sphere through democratic innovations[Subir]

When referring to the expansion of the “public sphere” in its Habermasian sense, this reference is to the fact that the space in which citizens deliberate on common problems is today more diverse in terms of forms, subject matter and agents, than it was at the beginning of the 20th century. The concept of public space is used for that space in modern societies where political participation happens through discussions, informal gatherings, literary salons, etc. It refers to the social space in which discussion and participation takes place (Habermas, Jürgen. 1989. The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. Cambridge: MIT Press.Habermas, 1989). In this social space, a way of talking that the author calls “bourgeois” (bourgeois public sphere) has predominated, and this must be enlarged and extended in order to radicalise democracy. In this undertaking of sketching out a new, “post-bourgeois” public sphere (Fraser, Nancy. 1996. Justice interruptus: Critical reflections on the” postsocialist” condition. Londres: Routledge.Fraser, 1996: 133), Habermas sees deliberation and rational argument as effective instruments. Transparent and plural dialogue and communication constitute his proposal’s central tools.

It is certain that an extension of the public sphere, through democratically innovative apparatuses, is today a noticeable fact. Experiences of e-democracy are increasing and becoming consolidated (Cardon, Dominique. 2010. La démocratie Internet, promesses et limites. París: Seuil-La République des idées.Cardon, 2010); the number of participatory budgeting programmes has increased in most countries (Bacqué, Marie. 2005. Gestion de proximité et démocratie participative. Paris: La Dévouverte.Bacqué, 2005); and it is possible to find forums where matters previously considered to be “pre-political” such as gender norms[5] are nowadays being discussed.

In this context, one of the tasks of Critical Theory is to know under what conditions this expansion trend has taken place and whether or not it has really incorporated those who, throughout history, have had little ability to signify reality on their own terms; or, in another way, those who have had limited symbolic power (Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. “Sur le pouvoir symbolique”, Annales. Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations, 3: 405: 411.Bourdieu, 1977). In this regard, although on many occasions the value of Habermas’s conceptual proposal to the theory of democracy has been recognised (Fraser, Nancy. 1996. Justice interruptus: Critical reflections on the” postsocialist” condition. Londres: Routledge.Fraser, 1996), feminist criticism has also offered many contributions to the notion of public sphere (Pagé, Geneviève. 2014. “L’art de conquérir le contrepublic: les zines féministes, une voie/x subalterne et politique?”, Recherches Féministes, 27 (2): 191-215.Pagé, 2014). This body of criticism underlines the multiple exclusions motivated by class, gender, sexuality, race, capacity for bodily mobility and age that underlie the “bourgeois public sphere”.

Joan Landes has shown that Habermas’s notion of public sphere conceives language as the only possible form of expression, ignoring others related to the expression of emotions and body language (Landes, Joan. 1992. “Jürgen Habermas, the structural transformation of the public sphere: A feminist inquiry”, Praxis International, 12/1: 106-127.Landes, 1992). According to Landes, the problem with Habermas’s conceptualisation lies in thinking that the way to occupy the public sphere is neutral and, therefore, universal. Therefore, the German author fails to recognize that the public sphere has been conceptualised against the private-domestic one, and that the public sphere has been mainly occupied by white, heterosexual, bourgeois men. Landes’ view allows a connection with one of the inputs of studies of political intersectionality related to the idea that the praxis of the political expansion of the public space does not take into consideration agents beset by different axes of domination, such as race, gender, age or others (Cruells, Marta. 2015. La interseccionalidad política: tipo y factores de entrada en la agenda política, jurídica y de los movimientos sociales. Lombardo, Emanuela (dir.), Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Barcelona.Cruells, 2015). For this reason, they have fewer opportunities to export their own forms of expression to the public space. The rationale that makes the public sphere neutral is a bourgeois rationality, according to Landes, that does not relate to many women’s life experience (Landes, Joan. 1988. Women in the public sphere in the age of revolution. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 1988).

Iris Marion Young also underlines the aspirations to universality in the form of dialogue

involved in the bourgeois public sphere, founded on the false idea that culturally

neutral and universal deliberation is possible (Young, Iris Marion. 1989. “Polity and group difference”, Ethics, 99 (2): 250-274. Disponible en:

Nancy Fraser has also contributed to the critique of the Habermasian public sphere

is. She shares Habermas’ idea that the public sphere is a bourgeois public sphere

in which not all social groups have the same capacity to intervene and that this is

one of the constituent facts regarding the different imbalances of power between agents.

However, in Fraser’s judgement, the German thinker idealizes a form of liberal public

sphere that forgets about the existence of non-bourgeois and non-liberal publics who,

although with less capability to signify, have tried to create spaces to name the

world (Fraser, Nancy. 1990. “Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique

of actually existing democracy”, Social Text, 25/26: 56-80. Disponible en:

Fraser’s fundamental contribution lies in highlighting that, apart from its classism, the public sphere is also permeated by the gender, racial and heteronormative system, and so the dominant form of occupying the public space (male and bourgeois) creates a multiplicity of publics. This idea allows the introduction of the political intersectional perspective, which makes Fraser’s proposal attractive and suitable to the many discriminations against the agent, and the effect that this has on the configuration of that agent’s social position[6].

To recapitulate, within the critical theory of democratic innovation, the feminist theory warns against the possible exclusions underlying the expansion of the public sphere that, as this text proposes, is currently occurring through DIs. This critique calls attention to, at least, the following risks: the aspiration to universality when occupying the public space; the false neutrality of bourgeois reasoning; wanting to design a supposedly impartial decision-making space; the deepening of the public-versus-private dichotomy; and the invisibilization of other publics. However, as it has been stated above, this theory offers proposals and solutions for the gradual deactivation of exclusion. Nancy Fraser’s proposal, one of the foundations of this essay, must be seen in this light.

Although Fraser’s contribution has been much used and debated on the normative plane, there have been fewer attempts to operationalize the term and to apply it to specific cases with an inductive approach to political reality.

Subaltern Counterpublics And Democratic Expansion[Subir]

Nancy Fraser’s proposal regarding subaltern counterpublics is closely related to an

idea that Virginia Woolf brought up in 1929: women need money and a room of their

own to write. Woolf helped us make clear, with the figure of “the room of one’s own”,

the importance of material and symbolic conditions for writing. Writing, enunciating

in one’s own words, considering the social position of agents when it comes to transforming

reality is, then, one of the goals of counterpublics. Specifically, for Fraser, counterpublics

are: “Parallel discursive arenas where members of subordinated social groups invent

and circulate counterdiscourses, which in turn permit them to formulate oppositional

interpretations of their identities, interests, and needs” (Fraser, Nancy. 1990. “Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique

of actually existing democracy”, Social Text, 25/26: 56-80. Disponible en:

Analysing Fraser’s proposal, it can be concluded that the author is concerned, like Woolf, both with material and with symbolic conditions in which individuals find themselves and which affect the ability to enunciate in the public sphere.

However, as she herself states, not all counterpublics are positive in democratic terms, since some of these parallel arenas defend anti-equality discourses (for example, anti-feminist or xenophobic groups). Furthermore, it is important to indicate that these counterpublics can be found in very different political-cultural contexts, adapting themselves to the characteristics of the environment. However, I find a potential inherent in Fraser’s concept. It can be considered that the analysis of counterpublics’ discourse allows the obstacles to inclusiveness to be identified from a political intersectional approach that allows access to the point of view of those who experience exclusion in the processes of expanding the public sphere. I consider that intersectional inequality in the author’s approach is intuited based on her vision of “bivalent groups” that suffer from both poor socioeconomic distribution and erroneous cultural recognition. Fraser defines gender and race as paradigmatic bivalent groups, allowing the possibility of visibilizing the new situations of inequality resulting from the overlap of a lack of redistribution (class) and recognition (identity) (Fraser, Nancy y Axel Honneth. 2003. Redistribution or recognition? A political-philosophical exchange. Londres: Verso.Fraser, 2003: 87).

In her work, the author offers what she considers to be an outstanding example of

a democratising counterpublic: the late 20th century US feminist counterpublic which, through a network of bookshops, cultural

production and research realised the constitutive protest function of all such collectives.

This community minted a series of concepts such as “sexism” and “patriarchate” to

define, in its own terms, the reality as they were experiencing it. In this way, once

their needs were identified, they could set out their arguments before other publics

with more likelihood of them having an impact. From this it can be deduced that the

main, but not the only, function of these arenas is to protest against the pretensions

to being all encompassing of the dominant publics, based on the identification and

formulation of the group’s specific needs. The validity of these functions has been

confirmed in recent studies of the feminist and women’s movement in Spain in the field

of labour (Ruiz García, Sonia. 2015. “Power and representation: feminist movement challenges

on work”, Revista Española de Ciencia Política, 39: 195-220.Ruíz García, 2015), and in France in the field of reproduction (Contamin, Gabriel. 2007. “Genre et modes d’entré dans l’action collective. L’exemple

du mouvement pétitionnaire contre le projet de Loi Debré”, Politix. 78: 13-37. Disponible en:

However, Fraser is aware that these alternative publics might have different functions according to the society in which they are located. In egalitarian multi-cultural societies[7], counterpublics would seek to support the ideal of participation and deliberation, since for this task the existence of multiple publics, who can offer their different visions of a social reality, is desirable. In stratified societies, in which the “basic institutional framework generates unequal social groups in structural relations of dominance and subordination” (Fraser, Nancy. 1996. Justice interruptus: Critical reflections on the” postsocialist” condition. Londres: Routledge.Fraser, 1996: 148), counterpublics have two functions: “On the one hand, they function as spaces of withdrawal and regroupment; on the other hand, they also function as bases and training grounds for agitational activities directed toward wider publics” (Fraser, Nancy. 1996. Justice interruptus: Critical reflections on the” postsocialist” condition. Londres: Routledge.1996: 151).

Like Fraser, I believe that societies that are called democratic are on the road to becoming multi-cultural egalitarian societies and, therefore, these counterpublics have multiple functions: protest, withdrawal and regroupment; the construction of meanings and interpretations; and the elaboration of emancipatory strategies.

The Basque society, which is the subject of this article, is situated on this continuum between stratified and egalitarian society. There, as will be argued below, counterpublics have both a protest and a democratising function.

CONTEXT AND DATA COLLECTION[Subir]

Studying the limits on the expansion of the public space from the viewpoint of counterpublics takes up one of the central ideas of standpoint epistemology, according to which those located on the margins have a clearer view of the process of creating knowledge in a way that is more free from androcentric, sexist, racist and classist values (Collins, Patricia H. 1990. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Londres: Routledge.Collins, 1990). Furthermore, it invites us to take a methodological approach consistent with the desire to place at the centre of things the life experiences of those who suffer exclusion in the DIs that channel the expansion of the public space.

With the goal of finding out about the limits of this expansion I have carried out an analysis of the feminist subaltern counterpublic (hereinafter FSC) in fifteen DI apparatuses set up in the Basque Country between 1978 and 2014. These are fifteen innovative spaces with different topics[8].

In seven of the apparatuses, the presence of a FSC has been detected, participating within in one of the following ways: (1) Arena made up of women who belong to a feminist group and who participate as representatives of it within the democratic innovation space. In the feminist group there are more or less formalised spaces and times for dialogue, where the person who represents the counterpublic at the DI shares her impressions about what has happened in the apparatus, asks for advice and, as a group, they create a discursive strategy. This FSC is identified as “external to the DI apparatus”. (2) Arena made up of women who promote a group within the DI space with a counterpublic intent. In this case, the ID apparatus started without a feminist vocation and discourse. This situation went against the “feminist requirements” of some of the women participating, so, they decided to create a women’s group to work on the subject of the DI – degrowth[9] –, with a feminist perspective. (3) Arena made up of women who, in spite of being non-permanent members of the two above-mentioned arenas, participate regularly in their activities and collaborate through interventions (attending lectures, seminars, occasional meetings) in the identification of optimal conditions for participation.

After the selection of the fifteen apparatuses, I contacted 42 women who contributed to them between 2013 and 2014. Sixteen of these women belonged to a FCP: Nine of them were young white women (aged between 20 and 30), six white adults (aged between 30 and 50) and one 50-year old white woman, all with high cultural capital (over 90 % have at least one university degree), and who define themselves as lower- middle class and/or middle class. Only one had a non-normative sexuality and two were mothers.

To find out more about the standpoint of those counterpublics, I applied an action research tool. So, during a first stage, a biography of participation[10] was written for each of the participants using life histories, and direct observation of two of the fifteen spaces was carried out. In a second stage, five discussion groups were run with women who had participated in the previous stage. Lastly, a process took place that “returned” the study to those involved and with the Basque society in general via two public deliberative seminars.

These sixteen women said that they had experienced moments of “external” and “internal exclusion” in the sense defined by Young (Young, Iris Marion. 2000. Inclusion & democracy. Nueva York: Oxford University Press.2000). When talking about these moments, they made reference in a non-hierarchical or additive way to different structures or axes of oppression such as gender, motherhood, age and educational level. None used the term intersectionality to refer to the relationship between them. However, this study incorporates the heuristic nature of the intersectional approach to the analysis of the limits of the current expansion of the public space. At methodological level, it follows authors such as Platero (Platero, R. Lucas. 2014. “¿Es el análisis interseccional una metodología feminista y queer?”, en Mendia, Irantzu et al.,Otras formas de (re) conocer. Donostia: Hegoa.2014), who recommend critically examining the analytical categories that order the world (woman, young person, mother and others), making explicit the relationships among categories and uncovering, in as much as possible, invisibilized realities. Therefore, the approach used here is based on the excluded viewpoint, taking into consideration their life experiences or biographies; and it takes form in an action research-based methodology. At the theoretical level it reveals the intersectional thought of Fraser’s normative proposals and comes into dialogue with the contributions of intersectionality thinkers and scholars (Collins, Patricia H. 1990. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Londres: Routledge.Collins, 1990; Cruells, Marta. 2015. La interseccionalidad política: tipo y factores de entrada en la agenda política, jurídica y de los movimientos sociales. Lombardo, Emanuela (dir.), Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Barcelona.Cruells, 2015).

HOW DO THE FEMINIST COUNTERPUBLICS BUILD DEMOCRACY?[Subir]

A first result of this analysis was the realization of the key role played by feminist subaltern counterpublics in enabling women’sparticipatory project and making it more sustainable over time. It was noted that the apparatuses in which a feminist counterpublic existed underwent changes in their internal organisation that permitted greater female participation (Martínez-Palacios et al., 2015). A substantial difference was found between those women who belonged to a FSC and those who did not, in two aspects closely linked to the possibility of making their participatory wishes coincide with their practices. Firstly, the first group of women identified, more readily than the second group, a series of oppressive structures that obstructed their participatory project. These structures include: the family in its patriarchal form, the idea of romantic love and the incorporation of some gender norms such as discipline and discretion. Secondly, women belonging to a FSC were able to enunciate a greater number of both reflexive and embodied strategies that could be used to facilitate their participatory projects when confronted with those oppressive structures that explain the external and internal forms of exclusion. A look at the experience of those sixteen women will provide more information about how feminist counterpublics build democracy.

Becoming counterpublic: Revaluation of the public, the importance of emotion and the search for models[Subir]

Three major reasons have been detected as motivations for the sixteen women to join or form a FSC. These women linked these motivations to some kind of “contradiction”[11] they had experienced in their lives.

The first contradiction is related to the public-versus-private dichotomy. All the women agreed that, as in other areas of their lives (work, school and family), in the DI they took part in, they experienced the confrontation of a private/domestic sphere – considered to be a women’s domain and less appreciated socially – and a highly regarded public sphere, in which the presence of men has predominant. This contradiction connects with the feminist critique of the theory of democracy according to which the systematic gender division of space has created a domestic image of women, far from public life, which blocks the citizenship status of many of them (Pateman, Carole. [1992] 2012. “Equality, difference, subordination. The politics of motherhood and women’s citizenship”, en Carver, T. y C. Sanuel, Carole Pateman: Democracy, feminism, welfare. Nueva York: Routledge.Pateman, 2012).

This contradiction has been strongest in the case of the women over 30 years old and it has been most clearly stated by mothers. Women situated at this intersection see in motherhood a social institution that “swallows” women into the domestic space, excluding them from the public sphere for two reasons. Firstly, because in the domestic sphere women exercise skills linked to the emotions and care tasks that are not valued in a context of discursive ability, like the public space. Secondly, because expansions of the public space do not have a planned structure for “not making a women feel guilty if she wants to take a child, who makes a noise during meetings. Often when I do it, they give me dirty looks, as if they are asking me to take responsibility for him” (Jane, aged 36)[12]. It has been found that the mothers’ detachment from the participatory spaces lasts for the first two years of the baby’s life. During this period, women are disconnected from the DI, neglecting the participatory skills valued there. Afterwards, there is no “reinsertion mechanism” that facilitates their return to the participatory space. The result is that many women opt to stop participating in DI spaces and decide to dedicate themselves to caring for their children.

However, one of the women highlighted her experience of that contradiction. She found in a feminist space, like Woolf’s room, the chance to think about other models of motherhood and ways of coming to agreements regarding care, which made her participation easier:

That is a thing that really makes me angry; how the system acts with women, and particularly with women who are mothers, that makes me angry. It puts us in a frame of mind by which we have to choose, and that isn’t fair. I feel that I have to choose between participating and looking after my child. Why? It isn’t fair! It isn’t talked about, but it is there. When I brought up the subject in a non-feminist space, it was a waste of time. There wasn’t any desire, any willingness to talk about that subject, it wasn’t of interest. But it is important! Because we have these tasks loaded onto us (Patricia, aged 36).

This contradiction was also found in the sexual division of labour that occurred in

the DI spaces. All the sixteen women agreed that they felt uncomfortable when they

saw a gender division of tasks reproduced in spaces that were claimed to be democratic.

While men carried out public coordination tasks, women carried out a executive-relational

work. This has also been revealed in other studies of the women’s participation in

social movements (Falquet, Jules. 2005. “Trois questions aux mouvements sociaux «progressistes» apports

de la théorie féministe à l’analyse des mouvements sociaux”, Nouvelles Questions Féministes, 24 (3): 18-35.

My analysis of it is that women are much more involved in private matters; the involvement of women has not been permitted in public affairs. We have a lot of great skills but often these are not adapted to being in public. (…) It is much more difficult for us to speak out, and I have seen that happening in meetings[13]. On the other hand, men… I am really shocked sometimes; a guy arrives and it’s the first time he attends and it’s no problem for him to say: “well I don’t like that”. In my opinion they are really daring, they have a licence to participate in public that women don’t. So, it is great for them, because they have the power to manage issues, to give opinions or to say what they want, and that’s great, but also often it is done without respect or without being careful, because I’m a man! Because that is the education they have received. And the women are on the other side of that. I am tired of seeing women preparing cultural week, and when it’s time to do things: “I’ll make the chocolate, I’ll get the kids…”, doing things! And the men are like: “I’ll phone whoever to see if they can bring whatever” and I feel like saying: “why don’t you go for it?”

Simone saw that, within the DI, women were systematically expected to take charge of tasks related to care, without these being socialized or valued. She needed to put forward this criticism and transform the structure of the DI apparatus in which she was participating and so she joined a FSC. It is possible to see here clearly the regrouping function of counterpublics.

The second contradiction relates to the reason-versus-emotion dichotomy, and has been particularly demonstrated by women under 30. This consists of perceiving there are physical as well as verbal methods of expressing oneself in the public sphere. These physical methods include very important relational elements that many women say they feel comfortable with, and which are undervalued in or absent from the DI apparatus. A direct connection can be seen here with the critique that Joan Landes makes of narrow conceptualizations of the public space that identify language as the only possible expression in it. After analysing the narratives of the women participating in counterpublics, what became clear was not only the invisibilization of other forms of expression, such as bodily ones, but also the discrimination of all uses of knowledge that are considered non-expert. In one of the focus groups made up of women under 30, the following was said:

–I don’t feel happy at all about the fact that everything related to feelings is left out of the assembly. I think that feelings, not feelings against others, or hurtful ones, but others, should have their place. For example, if there has been an argument by e-mail a couple of days before, we get to the assembly and there is no talk about ‘listen, what has happened here?’, ’we need to look after one another’ There is nothing of that kind! (Laure, aged 29).

–Yes, or… being able to share and to say: ‘look my limits are here’. Or to say ‘I am really scared and, I don’t know, and I am just as good as all the other people here, no? And in many spaces you can’t, can you?’ (…) The atmosphere doesn’t let us express insecurity and fear and so, based on that, you put limits on yourself, don’t you? Ok, I am really scared and on top of that here I am not going to be able to say so, so I’m not going to that place!” (Amy, aged 26).

Detecting that there is no place for those emotional expressions in a space where a debate is expected based on the exclusive use of reason and the strongest argument, has motivated women to create a FSC in which they can give a recognised place to emotions and relationships.

In the participatory observations carried out, notes were taken on the different body positions. From there, it became clear that women showed more affective and relational attitudes than men. And they did so through physical mechanisms of inclusion, such as: smiling at those entering, as if they have been invited to participate; giving a hug at the beginning and end of the meeting; nodding and giving eye contact to the person taking part; or stroking someone’s arm to show support.

The sixteen women whose biographies were taken also raised a third contradiction.

Both, younger and older women agreed in equal measure that the expansion of the public

sphere followed to the codes of a dominant class which they did not feel represented

them. This coincides with Young’s (Young, Iris Marion. 1989. “Polity and group difference”, Ethics, 99 (2): 250-274. Disponible en:

I also see that there is less diversity in [participatory] spaces; there is a certain profile of white men or women who are middle aged, with no children or people to look after. I am looking for other colours, I am looking for… other ethnicities, another kind of life, not this ablecentrism[15].

In the direct observations, data were collected taking into consideration the persons who joined in the group on the days of observation. The results support the idea that, in general, groups are uniform and highly adapted to social norms:

The number of people attending is 37. 14 women and 23 men. (…) The average age is around 30 to 35. There are two people, a man and a woman, of Latin American origin, the others have light-coloured skin and are of Basque origin.” (Notes from direct observation of culture topic DI apparatus carried out by the author of the text on 3 November 2014).

The number of people attending is 14. There are 6 women, 8 men and a dog. The approximate average age is 40-50. The youngest woman is 28. These are mostly people without children (3 out of 14 with children). There is a woman in a wheelchair with reduced mobility. All are Spanish citizens and always have been. All are white” (Notes from direct observation of degrowth topic DI apparatus carried out on 28 June 2014).

The lack of diversity was noted by all sixteen women. As they said, there was an absence of valid references or models within the DI space on whom they could model behaviour in order to create their own. In their various ways, the lack of diversity is related by them, in terms reminiscent of Young, to the existence of a dominant model for participating and discussing. This model is generally represented by men and is one that they do not identify or feel comfortable with. As one of them put it, “they have had to fight to put their views forward”, “they have had to raise their voices excessively” to be heard and that “has made them feel uncomfortable” (Simone, aged 40). Faced with this situation, the sixteen women have found in the FSC they belong to an opportunity to discover other subjectivities and different ways of doing things; to share doubts; and to name elements that limit their freedom.

It is important to point out that the absence of identified diversity has not, up until now, allowed the emergence of the intersectionality notion on the apparatus’s agenda; nonetheless, this is clearly a practical expression of the idea of political intersectionality. Criticism of uniformity means that participants from the FCP affirm, in the majority public – hegemonic public –, the existence of axes of domination such as social class, race or educational level which block participation in the particular way it is offered. In one way or another, this reveals the form of the normative subject for whom, according to these counterpublics, the apparatuses are designed. The data available do not reveal the extent to which these reflections are considered in the majority public when those constituting the counterpublic are not present. With the consolidation of DIs, studies into this matter will be very relevant.

The consequences of feminist subaltern counterpublics: Extension of the notion of participation and changes in structuring the apparatus[Subir]

It is possible to gather the consequences that parallel arenas have had for the processes of enlarging the public sphere through DIs into two major groups: the consequences on the specific women’s participatory projects, and those related to the structure of the DI apparatus. Considering these consequences, it is also possible to see what kind of functions these counterpublics have had.

Regarding the impact on the participatory projects, these arenas have allowed to problematize the political meaning of many negative feelings that women previously felt privately and individually with regard to their participation and which were related to forms of “internal exclusion”. Arguably, then, these counterpublics had a therapeutic effect by making available the space and time needed to reflect; this space is what is referred to by the figure of “a room of one’s own”.These publics offered the chance to state that participation has a race, a gender, a class, an age and a dominant sexuality. In other words, these arenas have allowed the integration of the political intersectional viewpoint into participation with a questioning of the so-called universality of participation in those innovative spaces. This questioning has been undertaken in terms of the presence/absence of diversity, revealing, as we have seen above, the most objectified aspects in which oppressive structures are materialized. Yet it goes further, and has also emphasized the embodied elements of the oppression carried out by such structures, such as embarrassment, fear and discretion. So, they have given a political reading and an interpretation in terms of domination of some social facts that seem to be “natural” and which are often linked to the agent’s personality. Other embodied elements worth mentioning include feeling nervous when talking, that they are not offering anything when they take part or that they are not up to the situation; shaking; blushing; and perceiving the obligation to leave to one side their emotions in order to make their speech more legitimate. These counterpublics have given political value to embarrassment, fear or nervousness and use them to initiate a contrast and experimentation space for women, where they can practise “sorority” and find models to follow (Lagarde, Marcela. 1990. Los cautiverios de las mujeres. Madrid: Horas y Horas.Lagarde, 1990).

In this sense, Virginia (aged 28) declares that having a discussion about “the fear of beginning to participate” and making that matter visible has allowed its problematization and the creation of strategies that she decided to use whenever another woman participates for the first time in the apparatus where she belongs to:

I don’t know, seeing a person at a presentation or somewhere, and we don’t know who she is and you see she is alone, well try to… I try to go to her, even though it makes me feel really nervous! But well, she has come here, and she should feel OK, shouldn’t she? She doesn’t know anyone, I have also been new in places, haven’t I? and I am always grateful if someone comes to speak to you. Maybe my tactic for not coming into confrontation with the hard reality of it is to, little by little, well, when younger girls come, to try to make them feel good; because there are more men than women at [name of the DI space] and there is lots of division of tasks and that’s not good, but… I don’t know. It makes me angry to go and see that those on the scaffolding are all men. Maybe that is a coincidence, but normally things don’t happen by chance. It is important (…) so women need to look after each other, when we don’t know each other and, I don’t know, it has been a really positive process.

As Virginia explained, sorority follows a course of putting oneself in the place of

another (a place in which she had already been), putting care at the heart of actions

(caring for the other) and building alliances among women. The intention is to create

“positive relationships” and make “existential and political alliances” among women

with the aim of “contributing to the social elimination of all kinds of oppression”

(Lagarde, Marcela. 2006. “Pactos entre mujeres y sororidad”, Aportes para el debate: 123-135. Disponible en:

An important part of this work of interpreting and resignifying, which ultimately is own’s own interpretation of their participatory experiences, has broadened the notion of participation. There is a tendency in Political Science and Sociology to distinguish social, political, citizen and community participation without leaving a place to forms of participation linked to domestic care, such as organisations of parents when taking children to school, or participation in a scout group (Cunill Grau, Nuria. 1999. “La reinvención de los servicios sociales en América Latina”, Revista del CALD Reforma y Democracia, 13: 1-29.Cunill, 1999). None of the sixteen women had any doubts when it came to identifying their time at school or in scout groups as participation. Pilar explained how, for them, participation covers everything that affects and influences the construction of society, and not only what has results in terms of policy.

I don’t remember when I began to participate because I think I have always participated. Maybe it is because since I was small I was taught to participate at school, at home, among my friends, that is also participation, that is how we started, participating in society to be a free subject and think like one (Pilar, aged 29).

There is a clear implication in the use of such a broad definition of participation in the sense that it includes activities traditionally invisibilized or as Landes suggests, other forms of expression, demonstrating their value. Furthermore, it makes it possible for people who have traditionally been excluded from making any kind of socio-political contribution to be defined as participating agents.

With respect to the consequences in the DI, it is important to mention that these arenas have not always managed to introduce the topics and forms that women wish to express into the wider public. Only one of the fifteen analysed here showed a notable change of agenda and structure due to the action of these parallel arenas. This was one of the two observed cases where the counterpublic was founded within the DI from the very beginning, which at least partly explains the counterpublic’s achievement on this matter. Two visible consequences have been detected in this experience: a broadening of the topics tackled within the apparatus, incorporating new ones traditionally linked to the domestic sphere (such as care or the mood of the participating agent); and the transformation of the apparatus’s structures.

An example of the need to name reality on one’s own terms is found at one of the assemblies that the researcher was able to attend:

The following topic is set out by an FSC woman (Almudena). Those present pay attention. Two men look at the floor when she talks, the women look her in the eyes. A woman, using the ‘I want to speak’ card, talks about the possibility of working on this topic in another area in which the DI is present. Almudena says “my feeling is that degrowth ignores the crisis in care; it is talked about but it is not really taken into consideration”; she offers specific data “unemployed men do less housework than employed women”. Everybody seems interested in the study she presents. Some time is spent looking at it. The chair doesn’t say anything (Notes from direct observation of degrowth topic DI apparatus carried out on 28 June 2014).

The way of tackling a matter (degrowth) in this case left out a topic that the FSC considered vital, namely, the crisis in care. Here, there is an FSC within the apparatus that allows those who belong to it, after working on the matter internally during weekly meetings, to bring to the dominant public their opinion with enough “energy” so that their point of view becomes part of the apparatus’s agenda. Evidence that this DI’s agenda has been changed can be found in the fact that currently, both in the manifestos and in the public statements produced by this innovation apparatus, it is not possible to talk about degrowth without mentioning the crisis in care. Like the FSC of the 1970s referred to by Fraser, in this case interpretations of reality have been carried out that include concerns and viewpoints excluded by the majority public. These interpretations have also given place to the formulation of concepts that can be used to name reality (e.g. the care crisis).

Furthermore, in this same case, it is possible to detect a change of structure motivated by a previous diagnosis by a feminist counterpublic. This counterpublic identified a gender division of labour in the apparatus and a level of domination by those who know the linguistic codes of the rational debates, identifying the presence of people who

have an excellent political education who give speeches with very solid foundations, which are really well documented, very complex and I think most women, when faced with that, we feel excluded and as if we are not up to that level of excellence, or something like that. (…). The assemblies were carried out as open debates, with an agenda, and the different topics were debated, decisions were taken as a group, and it was almost always the same people who participated in this form of open debate, and they participated with long, very solid speeches, which lasted a long time, they were grandiloquent and often very vehement and usually it was the same kind of person who took part: older men, with experience, with a lot of previous activist experience (Almudena, aged 46).

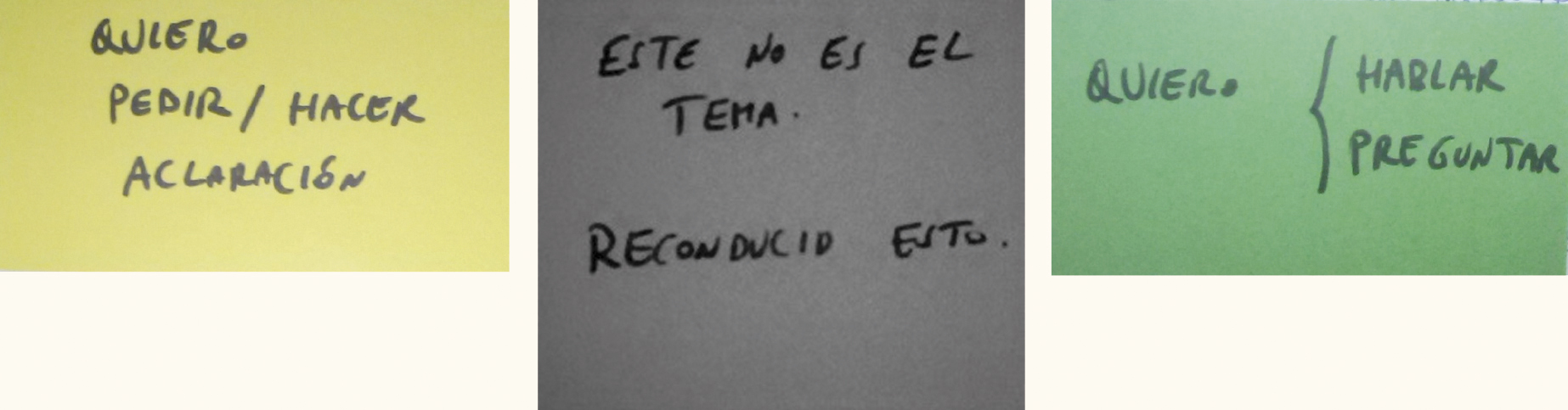

At the initiative of the FSC, a strategy was undertaken to strengthen participative spaces which recalls that strategy used by US feminists in the 1960s (Phillips, Anne. 1991. Engendering democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.Phillips, 1991: 120-46). In this new apparatus, dynamics were promoted with the goal of socializing speaking, including appropriate amounts of time and turns, and problematizing personal emotions and moods. A method was designed that involved cards that made the space more dynamic. Each participant was given three coloured cards at the beginning of the meeting on which were written the following messages “I want to ask for/make a clarification”, “this is off topic, return to the matter in hand” and “I want to talk/ask a question” (see figure no. 1). During the meetings the cards were used to intervene in the debate.

Figure 1.

Photograph of the cards used to take part in the meetings

Source: author of the article, July 2014.

In summary, these counterpublics have not only had positive consequences in terms of liberation and inclusiveness for the women and other social groups who belong to them, for example, by creating spaces for discussing topics considered to be domestic and therefore “pre-political”; but they have also managed, in cases where the counterpublic was formed within the apparatus, to make these topics pass onto the apparatus’s political agenda without their discourse being capitalized on by outside agents.

CONCLUSION[Subir]

This article started by acknowledging that an expansion of the public sphere is taking place based on the implementation of DIs. It has also confirmed the concerns of critical deliberative theory that this is happening in the terms of and according to the norms of those who occupy a dominant position in societies (Young, Iris Marion. 2000. Inclusion & democracy. Nueva York: Oxford University Press.Young, 2000; Fung, Archon y Erik Wright. 2003. Deepening democracy: Institutional innovations in empowered participatory governance. Londres: Verso.Fung and Wright, 2003: 26-34). The text also showed some of the many proposals, often created by employing a deductive logic of thought, that aim to deactivate the forms of exclusion detected in these DI apparatuses.

With the aim of finding out more details about the characteristics of the limits of this expansion and the possibilities to redirect it in inclusive terms, this article has focussed on subaltern counterpublics, as they are understood by Nancy Fraser. It has defended the thesis that listening to the experiences of oppression and resistance of the “hard to hear”, constituted into a counterpublic, provides information about the limitations of the forms being utilized to expand the public sphere.

The main conclusion from the case study presented here is that feminist subaltern counterpublics operate like large-scale and collective “rooms of one’s own” with respect to the expansion of the public sphere. These offer material resources (time and space) and symbolic ones (language, vocabulary) to those who belong to them, and they maintain contact with the dominant public, while also being able to transform the political agenda of the latter.

In those societies that fall between stratified and multi-cultural egalitarian ones, like the Basque case, it makes sense for FSCs to fulfil the functions that Nancy Fraser assigned to them in each of those societies. For this reason, it has been possible to see how, apart from supporting the participatory ideal by formulating a more inclusive concept of about what participation means and working for a broader concept that includes more people and more topics, these FSCs have also had the appropriate functions to stratified societies, namely, withdrawal, regrouping and speech and body language training. The withdrawal function has allowed to problematize embarrassment, fear and nervous feelings as a political matter. The training has made possible the practice of forms of speech and gestures that women have later brought into the dominant public. Fraser’s critique, which gives meaning to the counterpublics’ approach, is with respect to the situation in which there are groups systematically excluded from the public space, which means not just a lesser physical presence of these groups or an “external exclusion”, but also an absence of the ways of being that these groups can “manoeuvre” among spaces, resulting in “internal exclusion”.

Furthermore, from standpoint epistemology and using the inductive approach employed in this study it can be said that, what motivates women to join or create a FSC gives us clues to the shortfalls of today’s expansion of the public sphere. There are three logics by which this extension is reproducing a dominant system that does not include everyone: (1) the logic by which the private and domestic is systematically subordinated to the public; (2) the logic by which relational-emotional arguments are delegitimized compared with rational ones; (3) and the logic by which, in the enlargements of the public sphere, a univocal and falsely universal model of participation has been imposed that hides other possibilities and references when it comes to participating. These logics have been identified based on the contradictions expressed by those who experience the consequences of carrying out a restrictive expansion of the public space and it can be seen that they are related to the critique that Landes and Young respectively make of a notion of public space that excludes forms of expression that are not linguistic- or reason- based; and they present the form traditionally used of occupying the public space as universal and neutral.

These logics, revealed by those who identify and suffer from exclusion in the DI apparatus, connect with many aspects studied by critical theorists and particularly feminist scholars. One outstanding aspect that has been introduced into the study, but which deserves further research, is the heuristic nature of an intersectional approach to the expansion of the public space by means of democratic innovation. The sixteen women have referred to the complexity with which exclusion shows itself in the DI apparatus, both because of the diverse structures of power that permeate the apparatuses, and the objectified and embodied forms in which it reveals itself. From that point, the women seem to read these limits in terms of “contradictions”. Furthermore, they explore alternatives from that same point. That the fields of exclusion and domination in which the different axes interconnect are also fields of resistance is something that intersectionality theory has stated from its very beginnings (Collins, Patricia H. 1990. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Londres: Routledge.Collins, 1990). For this reason, future agendas for research into democratic innovation will have a broader perspective of inclusion if they take into account its maxim that “when they enter, we all enter” (Crenshaw, Kimberley. 1989. “Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics”, University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989 (1): 139-67.Crenshaw, 1989).

Acknowledgements[Subir]

These reflections have been possible thanks to different people who have dedicated their time and offered advice to the text’s author. The Berrikuntza Demokratiko Feministak (Emakunde 2014-2015 Research grants for Equality between men and women) team has been a source of knowledge and a laboratory of creation. This paper owes much to Igor Ahedo Gurrutxaga, Alicia Suso Mendaza and Zuriñe Rodríguez Lara. Furthermore, the contributions of Jean-Nicolas Bach, Dominique Bourg and the researchers at Ottawa University’s Institute of Feminist and Gender Studies have enriched the initial ideas that have taken shape in this text. The author would like to acknowledge the helpful comments made by the two people who evaluated this text. Their recommendations and advice, as well as those offered by the Secretaria de Redacción of the Revista Española de Ciencia Política have greatly improved the study’s initial manuscript. Thank you all for your help.

Notas[Subir]

| [1] |

The differences among democratizing via deliberation, via participation and via community

development exist both in their genealogies and in the normative conditions respecting

the legitimization of the outcome, product or decision (Martínez-Palacios, Jone. 2016. “Equality and diversity in democracy. How can we democratize

inclusively?”, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 35 (5/6): 350-63. Disponible en:

|

| [2] |

Young refers to internal exclusion as “those forms of exclusions that sometimes occur even when individuals and groups are nominally included in the discussion and decision making process” (Young, Iris Marion. 2000. Inclusion & democracy. Nueva York: Oxford University Press.2000: 53); and says that external exclusion “names the many ways that individuals and groups that ought to be included are purposely or inadvertently left out of fora for discussion and decision-making” (Young, Iris Marion. 2000. Inclusion & democracy. Nueva York: Oxford University Press.2000: 54). |

| [3] |

I refer to the fact that, in the academic field, and with the exception of some studies (Mansbridge, Jane, Janette Hartz-Karp, Matthew Amengual y John Gastil. 2006. “Norms of Deliberation. An inductive Study”, Journal of Public Deliberation, 2 (7): 1-47.Mansbridge et al., 2006), the procedure for responding to the excluding effects of innovation processes has been to make proposals adapted to commonly accepted normative criteria of what is understood as “fair” and “egalitarian” deliberation or participation. |

| [4] |

Empirical verification of exclusion based on absences or reiterations; presentation of proposals for inclusion in harmony with a normative understanding of “good” innovation; the trial of these proposals; the study of the limits on the expansion of the space, based on these proposals. |

| [5] |

A recent case of the application of discretion as a State norm in order to dominate women is found in the case of Turkey, where the Deputy Prime Minister, Bulent Arinc, declared in July 2014 that “women should not laugh out loud in public to protect moral values” to which many Turkish women responded by posting images of themselves laughing on the social and other media (http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-07-31/women-in-turkey-defy-call-not-to-laugh-in-public/5637742 [December 18, 2016]. |

| [6] |

As is explained below, the idea of intersection in Fraser is related to understanding that inequality comes about not only because of poor redistribution or misrecognition but because of the interaction of both. |

| [7] |

Fraser defines these as “societies whose basic framework does not generate unequal social groups in structural relations of dominance and subordination (…) classless societies without gender or racial divisions of labour. However, they need not be culturally homogeneous” (Fraser, Nancy. 1996. Justice interruptus: Critical reflections on the” postsocialist” condition. Londres: Routledge.Fraser 1996: 152). |

| [8] |

Azkoitia’s Deliberative space on Immigration; Laudio neighbourhood assemblies; Oñati Participatory Budgeting; Gipuzkoa Participatory Budgeting Networks; San Sebastian “Empowering the Neighbourhoods” participatory process; Assembly of the 15M Movement in Biscay province; Actions against the shareholders’ meeting, run by the Platform Against the BBVA; Vitoria Gaztetxe assembly; Bilboko Konpartsak; Alarde Mixto of Irun; Astra participatory process; Degrowth movement assembly; Gure Esku Dago process in favour of the right to decide; Abusu Sarean participatory project. |

| [9] |

Term used to refer to a socio-political movement based on anti-consumerist and anti-capitalist ideas. |

| [10] |

Biographies of participation are a kind of in-depth interview focusing on a specific agent’s experiences of participation (understood broadly). |

| [11] |

Term employed by the women themselves. |

| [12] |

The interviews were carried out in Spanish and/or Basque. The quotes used in this article have been translated into English by the author. |

| [13] |

DI apparatus in which she participates and which was analysed in the study. |

| [14] |

These are women who, although they have arrived in decision-making spaces, continue to hold a subordinate position. |

| [15] |

Following Toboso and Guzmán’s definition, according to which “ableism is based on the belief that some capacities are intrinsically more valuable, and those who possess them are better than the rest; that there are some bodies that are complete and others which are not, some people who have a disability or functional diversity and others who do not, and that this division is clear” (Toboso, Mario y Francisco Guzmán. 2010. “Cuerpos, capacidades, exigencias funcionales... y otros lechos de Procusto”, Política y Sociedad, 2010, 47: 67-83.2010: 70). |

References[Subir]

|

Bacqué, Marie. 2005. Gestion de proximité et démocratie participative. Paris: La Dévouverte. |

|

|

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. “Sur le pouvoir symbolique”, Annales. Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations, 3: 405: 411. |

|

|

Cardon, Dominique. 2010. La démocratie Internet, promesses et limites. París: Seuil-La République des idées. |

|

|

Collins, Patricia H. 1990. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Londres: Routledge. |

|

|

Contamin, Gabriel. 2007. “Genre et modes d’entré dans l’action collective. L’exemple du mouvement pétitionnaire contre le projet de Loi Debré”, Politix. 78: 13-37. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.3917/pox.078.0013. |

|

|

Cooper, Emeline y Graham Smith. 2012. “Organizing deliberation: The perspectives of professional participation practitioners in Britain and Germany”, Journal of Public Deliberation, 8 (3): 1-39. |

|

|

Crenshaw, Kimberley. 1989. “Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics”, University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989 (1): 139-67. |

|

|

Cruells, Marta. 2015. La interseccionalidad política: tipo y factores de entrada en la agenda política, jurídica y de los movimientos sociales. Lombardo, Emanuela (dir.), Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Barcelona. |

|

|

Cunill Grau, Nuria. 1999. “La reinvención de los servicios sociales en América Latina”, Revista del CALD Reforma y Democracia, 13: 1-29. |

|

|

De Sousa Santos, Boaventura. 1998. Reinventar A Democracia. Portugal: Gravida. |

|

|

Falquet, Jules. 2005. “Trois questions aux mouvements sociaux «progressistes» apports de la théorie féministe à l’analyse des mouvements sociaux”, Nouvelles Questions Féministes, 24 (3): 18-35. https://doi.org/10.3917/nqf.243.0018. |

|

|

Fraser, Nancy. 1990. “Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy”, Social Text, 25/26: 56-80. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.2307/466240. |

|

|

Fraser, Nancy. 1996. Justice interruptus: Critical reflections on the” postsocialist” condition. Londres: Routledge. |

|

|

Fraser, Nancy. 2008. Scales of justice: Reimagining political space in a globalizing world. Nueva York: Columbia University Press. |

|

|

Fraser, Nancy. 2013. Fortunes of feminism: From state-managed capitalism to neoliberal crisis. Londres-Nueva York: Verso. |

|

|

Fraser, Nancy y Axel Honneth. 2003. Redistribution or recognition? A political-philosophical exchange. Londres: Verso. |

|

|

Fung, Archon y Erik Wright. 2003. Deepening democracy: Institutional innovations in empowered participatory governance. Londres: Verso. |

|

|

García De León, María Antonia. 1994. Elites discriminadas. Barcelona: Anthropos. |

|

|

Habermas, Jürgen. 1989. The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. Cambridge: MIT Press. |

|

|

Karpowitz, Christopher, Raphael Chad y Allen Hammond. 2009. “Deliberative democracy and inequality: Two cheers for enclave deliberation among the disempowered”Politics and Society 37, 4: 576- 615. Disponible en: https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0032329209349226. |

|

|

Lagarde, Marcela. 1990. Los cautiverios de las mujeres. Madrid: Horas y Horas. |

|

|

Lagarde, Marcela. 2006. “Pactos entre mujeres y sororidad”, Aportes para el debate: 123-135. Disponible en: http://www.asociacionag.org.ar/pdfaportes/25/09.pdf [Consulta: 13 de febrero de 2017]. |

|

|

Landes, Joan. 1988. Women in the public sphere in the age of revolution. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. |

|

|

Landes, Joan. 1992. “Jürgen Habermas, the structural transformation of the public sphere: A feminist inquiry”, Praxis International, 12/1: 106-127. |

|

|

Landwehr, Claudia. 2014. “Facilitating deliberation: The role of impartial intermediaries in deliberative mini-publics”, en Kimmo Grönlund et al. (eds.), Deliberative mini-publics. Colchester: ECPR Studies. |

|

|

Lezaun, Javier y Linda Soneryd. 2007. “Consulting citizens: Technologies of elicitation and the mobility of publics”, Public Understanding of Science, 16 (3): 279-297. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662507079371. |

|

|

Mansbridge, Jane. 1990. Beyond adversary democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. |

|

|

Mansbridge, Jane. 1996. “Using power/fighting power: The polity,” en Seyla Benhabib, Democracy and difference: Contesting boundaries of the political. Princeton: Princeton University Press. |

|

|

Mansbridge, Jane, Janette Hartz-Karp, Matthew Amengual y John Gastil. 2006. “Norms of Deliberation. An inductive Study”, Journal of Public Deliberation, 2 (7): 1-47. |

|

|

Martínez-Bascuñán, Máriam. 2010. “¿Puede la deliberación ser democrática? Una revisión del marco deliberativo desde la democracia comunicativa”, Revista Española de Ciencia Política, 24: 11-32. |

|

|

Martínez-Palacios, Jone, Igor Ahedo Gurrutxaga, Alicia Suso Menzada y Zuriñe Rodríguez Lara. 2015. “La participation entravée des femmes. Le cas des processus d’innovation démocratique au Pays basque”, Participations. Revue de sciences sociales sur la démocratie et la citoyenneté, 15 (2): 31-56. |

|

|

Martínez-Palacios, Jone. 2016. “Equality and diversity in democracy. How can we democratize inclusively?”, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 35 (5/6): 350-63. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-04-2016-0030. |

|

|

Pagé, Geneviève. 2014. “L’art de conquérir le contrepublic: les zines féministes, une voie/x subalterne et politique?”, Recherches Féministes, 27 (2): 191-215. |

|

|

Pateman, Carole. 1970. Participation and democratic theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511720444. |

|

|

Pateman, Carole. [1992] 2012. “Equality, difference, subordination. The politics of motherhood and women’s citizenship”, en Carver, T. y C. Sanuel, Carole Pateman: Democracy, feminism, welfare. Nueva York: Routledge. |

|

|

Phillips, Anne. 1991. Engendering democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press. |

|

|

Platero, R. Lucas. 2014. “¿Es el análisis interseccional una metodología feminista y queer?”, en Mendia, Irantzu et al.,Otras formas de (re) conocer. Donostia: Hegoa. |

|

|

Ruiz García, Sonia. 2015. “Power and representation: feminist movement challenges on work”, Revista Española de Ciencia Política, 39: 195-220. |

|

|

Sanders, Lynn. 1997. “Against deliberation”, Political Theory, 25 (3): 347-376. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591797025003002. |

|

|

Smith, Graham. 2009. Democratic innovations. Designing institutions for citizen participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511609848. |

|

|

Surprenant, Marie-Eve. 2013. Les femmes changent la lutte. Quebec: Éditions du remue-ménage. |

|

|

Toboso, Mario y Francisco Guzmán. 2010. “Cuerpos, capacidades, exigencias funcionales... y otros lechos de Procusto”, Política y Sociedad, 2010, 47: 67-83. |

|

|

Warren, Mark. 2009. “Governance-driven democratization”, Critical Policy Studies, 3 (1): 3-13. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1080/19460170903158040. |

|

|

Woolf, Virginia. [1929] 1989. A room of one’s own. USA: Harvest. |

|

|

Young, Iris Marion. 1989. “Polity and group difference”, Ethics, 99 (2): 250-274. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1086/293065. |

|

|

Young, Iris Marion. 1990. Justice and the politics of difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press. |

|

|

Young, Iris Marion. 2000. Inclusion & democracy. Nueva York: Oxford University Press. |

Biografía[Subir]

| [a] |

Profesora adjunta de Ciencia Política en la Universidad del País Vasco-Euskal Herriko

Unibertsitatea. Forma parte del grupo de investigación consolidado Parte Hartuz: Estudios sobre Democracia Participativa en el que coordina el eje de investigación

“Feminismos y democracia”. Ha publicado distintos trabajos sobre la relación entre

la democracia participativa y la teoría feminista tales como: “Equality and diversity

in democracy. How can we democratize inclusively?” (Martínez-Palacios, Jone. 2016. “Equality and diversity in democracy. How can we democratize

inclusively?”, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 35 (5/6): 350-63. Disponible en:

|