Cracking the door open: Governing alliances between mainstream and radical right parties in Spain’s regions

Entreabriendo la puerta. Las alianzas de gobierno entre partidos de derecha mainstream y radical en la España autonómica

ABSTRACT

Spain’s mainstream right parties immediately cooperated with the radical right Vox as a support party for minority governments when it first entered regional parliaments in 2018 and 2019. We ask why the mainstream right opted to engage the radical right to govern and why the latter agreed. Only when we consider parties’ regional and national goals can we explain why the parties allied in Spain, and then only when we consider electoral as well as policy and office goals. We argue that centrifugal two bloc competition in the party system and electoral competition among the mainstream right parties on territorial and national identity issues encouraged engagement. Further, we show how the right bloc developed and solidified and how Vox constrained mainstream party choices by pushing for public recognition. It demonstrates the value of examining subnational politics, not only as another arena, but also as integral to party strategies.

Keywords: Party strategies, Mainstream right, Radical Right, Governments, Vox-Spain, Party competition, Minority governments, Coalitions, Spain.

RESUMEN

La derecha mainstream española colaboró con el partido de derecha radical Vox tan pronto como éste entró en los parlamentos autonómicos de algunas CCAA en 2018 y 2019. Esta colaboración consistió en aceptar el apoyo de Vox para la formación de gobiernos de coalición minoritarios. La pregunta es por qué la derecha mainstream española optó por aliarse con la derecha radical para que apoyase la formación de gobiernos desde fuera, y por qué ésta última aceptó hacerlo. Para poder explicar esta colaboración, es necesario tener en cuenta los objetivos de los diferentes partidos tanto a nivel autonómico como a nivel estatal, y sus metas electorales junto con las de políticas y cargos. En este artículo argumentamos que la competición centrífuga entre los bloques ideológicos de derecha e izquierda que caracteriza al sistema de partidos español, unida a la competición electoral dentro del bloque de derechas en torno a temas territoriales y de identidad nacional, alentaron la colaboración inmediata entre los partidos. Mostramos, además, cómo el bloque de la derecha se desarrolló y consolidó, y cómo Vox consiguió limitar las opciones de los partidos de derecha mainstream al exigir el reconocimiento público como partido legítimo. Este artículo demuestra el valor de poner el foco de análisis en la política sub-estatal, no sólo como una arena de competición más, sino como una parte integral de las estrategias de competición de los partidos a todos los niveles.

Palabras clave: Estrategias partidistas, Derecha mainstream, Derecha radical, Gobiernos, Vox-España, Competición entre partidos, Gobiernos minoritarios, Coaliciones, España.

The Spanish party system has changed dramatically in the past decade (Gray, 2020; Rodríguez-Teruel et al., 2018). In 2015, the centre-right Ciudadanos and the radical left Podemos became relevant electoral and parliamentary parties. Then in the cycle of elections in 2018 and 2019, the radical right Vox surged to capture seats in parliaments across the country. Spain had long been an outlier in Europe because of the lack of a significant radical right party (Alonso and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2015). Vox first became relevant for government formation in three (and only three) of Spain’s politically powerful regions in 2018 and 2019—Andalusia, Madrid, and Murcia. In each, Spain’s long-dominant conservative party, Popular Party (PP), and Ciudadanos (Cs) attained Vox’s support for minority governments of the PP and Cs.

Collaboration between mainstream and radical right parties as government coalition partners or support parties for minority governments is no longer uncommon in Western Europe, having occurred nationally in countries such as Austria, Denmark, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, and Norway (Albertazzi and Vampa, 2021; De Lange, 2012; Twist, 2019). Spain is interesting, in part, because the mainstream right parties engaged the new radical right party immediately.

This article asks why Spain’s mainstream right opted to ally with the radical right to govern, and why the radical right agreed. According to the coalitions’ literature, collaboration between the mainstream and radical right occurs when it is in the mainstream right’s office and/or policy interests (e.g. De Lange, 2012; Fagerholm, 2021; Twist, 2019). In other words, if an alliance with the radical right allows it to govern or govern with more power, and/or if the radical right is more proximate in policy terms (or perhaps flexible) than other potential allies, we should expect the mainstream right to seek an alliance.

However, we argue that an exclusive focus on policy and office goals and one territorial arena is insufficient to fully account for the right-wing alliances in Spain. Only when we consider parties’ goals at the regional and national levels and electoral goals can we account for why the mainstream and radical right allied in Spain. Our study builds on three literatures: (1) parties’ strategic choices regarding policy, office and vote goals (Müller and Strøm, 2000; Strøm, 1990), (2) governance in multilevel states (Field, 2016; Reniu, 2002; Ştefuriuc, 2009), and (3) radical right parties as strategic actors (Akkerman et al., 2016; Art, 2011; Luther, 2011; Zaslove, 2012). Rather than positing party goals exogenously, as often occurs in the coalitions’ literature, we empirically investigate them. We also consider party goals in multilevel perspective because multilevel state structures can shape party strategies.

The study examines the government formation processes in Andalusia (2018), Madrid (2019) and Murcia (2019) because these are the first cases at either the regional or national level where Vox was potentially relevant. We think these initial decisions represent a critical juncture in Spain. Spain’s regions are politically significant, and the parties’ central offices were visibly and heavily involved in the negotiations. Thus, the decisions constituted overall party strategies. The mainstream right parties’ alliances with Vox signalled to the Spanish public that they considered Vox a legitimate party. Empirically, the study draws on qualitative evidence, including interviews with party officials, newspaper reports, and party press releases.

We argue that centrifugal competition in the party system and electoral competition among the mainstream right parties on territorial and national identity issues encouraged engagement with Vox as an ally. This argument concurs with existing research on the development of polarised two-bloc politics in Spain, particularly between 2017 and 2019. This literature stresses party agency and vote-seeking strategies (Rodríguez-Teruel, 2020; Simón, 2020a, 2020b). One bloc contains the left and the most relevant regionally-based nationalist and regionalist parties. The other contains the mainstream and radical right. Whereas the existing literature examines national politics, our research demonstrates that decisions in the regions were integral to the establishment and solidification of the two blocs and provides insight into how they developed.

In the context of fierce and fluid competition on the political right, the severely weakened PP prioritized governing at the regional level and embraced Vox as an ally. The leadership did not think this choice conflicted with its national electoral goal of reuniting the right. Cs’ electoral goals in the national arena – particularly wanting to surpass PP and lead the political right -- led it to foreclose cooperation with the mainstream left, regardless of its policy and office payoffs. Thus, it needed Vox to govern. Vox agreed to support the minority coalitions and progressively pushed for recognition and legitimacy as a pathway to gain votes, while governing could wait.

The article proceeds as follows. First, we review the relevant literature and present our framework for examining government formation and party goals in multilevel perspective, then, we explain our case selection and empirical approach. An examination of the strategic environment in Spain between 2015 and 2018 follows. Next, we provide our empirical analysis of government formation negotiations in the three regions of Andalusia (2018/19), Madrid (2019) and Murcia (2019), followed by a concluding section.

GOVERNMENT FORMATION AND PARTY GOALS IN MULTILEVEL PERSPECTIVE[Up]

A growing body of literature seeks to understand the reaction of mainstream right parties to the rise of radical right parties (see, for example, Abou-Chadi and Krause, 2020; Bale and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2021; Downs, 2001; Heinze, 2018; Meguid, 2008). There is no widely accepted definition of a mainstream party (Moffit, 2021). As Moffit notes, scholars commonly use the term mainstream in contrast to other party types (single-issue, challenger, populist, etc.), which are the real focus of analysis. Among the few scholars who have ventured a substantive definition, there is no agreement on a single set of criteria, variously noting ‘ideological moderation, electoral dominance or governing potential’ (Moffit, 2021: 388). We recognize that the differences between mainstream and non-mainstream are ‘fuzzy, permeable and dynamic’ (Moffit, 2021: 386) and that satisfactorily defining left and right is ‘a very difficult task’ (Carter 2018: 161). We use Bale and Rovira Kaltwasser’s (2021: 11) recent conceptualization of a mainstream right party: one that considers ‘that the main inequalities within society are natural and largely outside the purview of the state’, ‘adopts fairly moderate programmatic positions’ (in the sense of positions that are considered as legitimate by a large majority in the country) and supports the liberal and democratic components of the liberal democratic order. There is certainly variation among mainstream right parties. In the European context, mainstream right parties include Christian Democrats, Conservatives and (often) Liberals.

Defining radical right parties is also highly contested in the literature (Carter, 2018). One of the most widely used concepts is that of “populist radical right”, proposed by Mudde (2007). He defines these parties as those whose core ideology combines nativism, authoritarianism and populism (Mudde, 2007: 26). Populist radical right parties differ from extreme right parties in that the former are ‘(nominally) democratic’ (p. 49). Some scholars disagree with the inclusion of populism as one of the defining characteristics of the radical right in Europe (Art, 2011; Eatwell 2000; Hainsworth, 2008; Ignazi, 2002). We agree. Radical right parties may or may not be (equally) populist. Following these scholars, we conceptualize their core ideology as characterized by exclusive nationalism, nativism, and authoritarianism.[1]

Mainstream right parties can, broadly, opt for disengagement strategies, such as ignoring the party or establishing a cordon sanitaire/blocking coalition, or engagement strategies, such as co-opting the party’s policies or collaborating with it in executive, legislative and electoral arenas (Albertazzi and Vampa, 2021; Heinze, 2018). This literature seeks to explain why mainstream parties adopt different strategies (Bale, 2003; Downs, 2001; Heinze, 2018; Van Spanje, 2010), and the consequences, for example, for party success, moderation/radicalization, and liberal democracy (Akkerman et al., 2016; Art, 2007; Capoccia, 2005; Krause et al., 2023; Meguid, 2008; Ziblatt, 2017).

In the executive arena, the literature examines why or under what conditions the mainstream right forms coalition governments with radical right parties (e.g. Fagerholm, 2021; van Spanje, 2010; Twist, 2019), or allies with the radical right as a support party for minority governments (Bale, 2003; De Lange, 2012). In this article, we are interested in the latter type of engagement. When it comes to governance, it is commonly not a binary decision of whether or not to govern jointly with the radical right. Often also on the table is a third option – an alliance with the radical right to govern, yet without the latter taking seats in the cabinet. This support-party relationship can be more or less formalized (Field and Martin, 2022: 333-35).

Scholars often examine party goals to help explain governing outcomes (Müller and Strøm, 2000; Strøm, 1990). Simply put, parties must make choices that often involve trade-offs—do they prioritize obtaining votes from the electorate, the policies they prefer, or the spoils of office? Such choices may help account for political outcomes. Often, the coalitions’ literature applies this framework by positing party goals exogenously and examining how the pursuit of these goals influences the outcome. The literature on mainstream-radical right collaboration on governance tends to assume that mainstream parties pursue office, policy, or a combination of office and policy goals, as does the broader literature on coalitions (Müller and Strøm, 2000: 7).

Two explanatory variables are particularly common. First, the electoral success of radical right parties makes them more consequential in the right’s ability to govern, thus the (larger) size of the radical right party is an important factor (Bale, 2003: 70; Fagerholm, 2021; Van Spanje, 2010; Twist, 2019: 20). Second, in terms of policy, scholars also hypothesize that the extremeness of the radical right party and the policy distance between mainstream and radical right parties ideologically or on specific policy issues are consequential (De Lange, 2012; Fagerholm, 2021; Van Spanje, 2010; Twist, 2019; Zaslove, 2012). Examining collaboration between mainstream and radical right parties as coalition partners and support parties for minority governments in Western Europe in the early 2000s, De Lange (2012) argued that mainstream right parties turned to the radical right because of an electoral shift favourable to the right, and the convergence of policy positions between the mainstream and radical right. Similarly, Fagerhold (2021) finds that electoral success and policy proximity to a weak prime minister are sufficient for the radical right’s inclusion in government.

However, Twist (2019) finds that proximity is not a good predictor of mainstream and radical right coalitions. Therefore, her approach assumes that (large) mainstream right parties are office seeking and want to accomplish policy priorities on a small set of issues, and that radical right parties are uniquely flexible regarding such issues. This makes the latter attractive coalition partners. Policy flexibility becomes an important explanatory variable, which also pushes the literature toward asking which policies or policy dimensions matter for assessing policy goals.

While this literature provides important insights, we think there are limitations. First, it generally assumes (mainstream) parties have the same goals or set of goals. Further, because they are posited to be office and/or policy goals, we know less about how vote goals shape parties’ decisions (see Twist, 2019: 34-35). Second, it does not typically consider the multilevel territorial structure of some countries. For example, if a study is interested in government formation at the national level, it examines national-level party goals. This assumes that government formation decisions are insulated from what occurs in other territorial arenas. Third, the literature tends to focus on the decisions of (larger) mainstream parties. Therefore, it tells us less about radical right strategies and how they shape outcomes, and what to expect when there are multiple mainstream right parties.

While we build on insights from the coalitions’ literature, we do not ask why a coalition did or did not form, or why a minority government instead of a coalition formed, as is common in this literature. Rather, we ask a slightly different question—why the mainstream right opted to ally with the radical right to govern at all, and why the radical right agreed. We think support- party relationships between the mainstream and radical right provide a signal to the public and other political parties that the radical right is an acceptable and legitimate partner, facilitating its normalization. Finally, decisions at the regional level can both constitute and shape overall party strategies (Kestel and Godmer, 2004). In a multilevel state, developments at the regional level can force parties to make decisions that they may not want to make. This provides an additional rationale for studying subnational politics (see, e.g., Heinze, 2022).

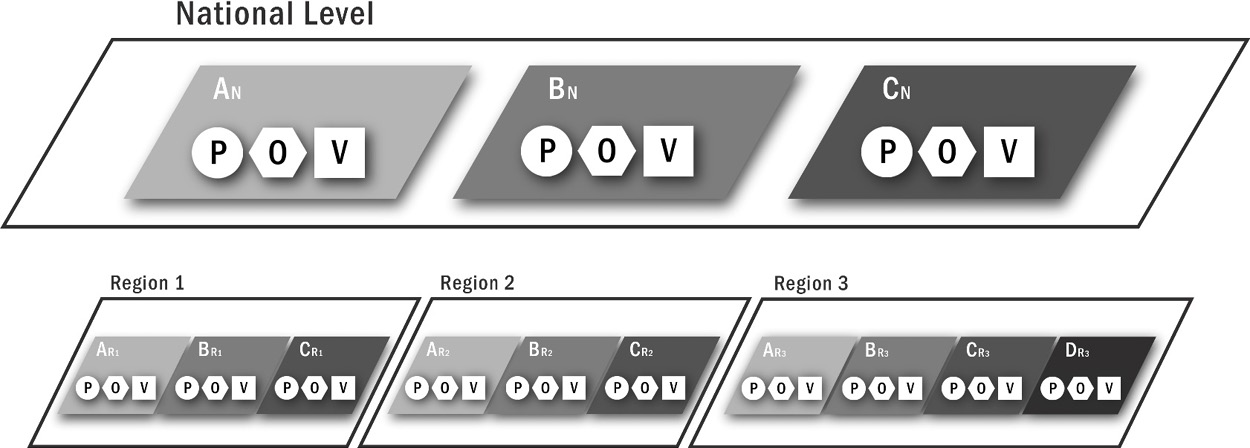

Our analyses of parties’ strategic priorities include policy, office, and vote goals (Strøm, 1990; Müller and Strøm, 2000) (see Figure 1). However, we do not assume that parties have a particular goal, rather we seek to identify them empirically. This allows for parties to have distinct goals from one another. We treat all parties as equally strategic, including radical right parties (Akkerman et al., 2016; Art, 2011; Luther, 2011; Zaslove, 2012), whose goals and strategies shape mainstream parties’ options, making some governing formulas more likely than others.

We also consider party strategies in multilevel, multi-parliament perspective. In multilevel states, parties’ goals can vary across territorial levels and potentially conflict across levels (Field, 2016; Reniu, 2002; Ştefuriuc, 2009). For example, a party may prioritize office goals at the regional level while prioritizing votes at the national level. Therefore, who in the party has the power to make decisions about governance is consequential (Ştefuriuc, 2009). Also, because parties can and do link governing strategies across parliaments (Colomer and Martínez, 1995), viewing government formation in multi-level and multi-parliament perspective can help account for outcomes that may appear anomalous when goals are only examined at a single territorial level.

Figure 1 depicts an example of government formation negotiations in multi-level, multi-parliament perspective. There are three parties involved in negotiations at the national level (AN, BN, CN), each of which must make choices about party goals: policy (P), office (O) and votes (V). There are also three regions with corresponding regional party branches of the national parties (AR, BR, CR). In Region 3, the figure also depicts a regional party (DR3) which only presents candidates in regional elections. While such regional parties were not relevant in the regions we examine ahead, they are in many of Spain’s regions and in other multilevel states.

We have three main expectations for our examination of Spain. First, given the fluid and highly competitive electoral environment in Spain at the time, electoral goals will shape parties’ decisions on governance. Second, the radical right Vox will strategically manoeuvre to attain its goals, as would any party. Third, national-level goals, when they conflict with regional goals, will impact decisions about governance in the regions where the national leadership has the authority to impose its will.

CASE SELECTION AND EMPIRICAL APPROACH[Up]

We study Spain and government formation in Andalusia (2018), Madrid (2019) and Murcia (2019) for several reasons. Regarding Spain, Vox is one of the newest radical right parties in Western Europe. There is now a rich literature on Vox, including its ideology, emergence, electoral base, party competition, organization, and impact on policy (Alonso and Espinosa-Fajardo, 2021; Arroyo Menéndez, 2020; Balinhas, 2020; Barrio et al., 2021; Ferreira, 2019; Gray, 2020; Oliván Navarro, 2021; Ortiz and Ramos-González, 2021; Rama et al., 2021; Turnbull-Dugarte, 2019). To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine governance strategies after its electoral breakthrough. Spain also provides the opportunity to examine the interactions between and among two mainstream right parties and a radical right newcomer, and party strategies in a complex territorial environment.

We examine the regions of Andalusia, Madrid and Murcia because they are the first cases at either the regional or national level where Vox was potentially relevant. We examine all three because they belong to the same cycle of elections in 2018 and 2019. Because the mainstream parties chose to govern together with the external support of Vox in all cases, we think these initial decisions represent a critical juncture. With these choices, the mainstream parties accepted Vox as a legitimate ally. We do not examine subsequent governance choices, which would come in 2021, because Vox had already been normalized in the 2018/19 cycle.

Finally, collaboration between the mainstream and radical right in Spain presents a puzzle. The Popular Party’s willingness to ally with Vox is, at least, consistent with office- and policy-seeking theories. With the fragmentation of Spain’s party system, PP ended up severely weakened and positioned ideologically between Ciudadanos and Vox. If PP wanted to govern, an alternative alliance with its main competitor, the Socialists, likely would have diluted its power in government and been further from its policy preferences.

However, the existing literature does not provide a fully satisfactory answer for the decisions of all the parties in our analysis. Positing office goals cannot explain why Ciudadanos rejected a two-party coalition government with the Socialists in Murcia that would have given it more power. Also, depending on the policy dimension we choose—economic, social or territorial—, we would come to different assessments of proximity. Moreover, Cs’ choices from a policy perspective were not consistent with its call for democratic renewal and cleaning up politics. Suspicions of corruption tainted the incumbent governing parties in all three regions. In Andalusia, Cs’ choices removed the incumbent PSOE from office, where it had governed since 1982. However, Cs allied with PP in both Murcia and Madrid, where PP had governed since 1995.

Having established our case selection, we now present our empirical approach. We examine government formation processes in the three regions while also considering developments nationally. Our analysis of parties’ goals, calculations and internal decision making is based on interviews, press releases from the parties’ central offices, and press reports. We conducted 16 semi-structured interviews between 2019 and 2020 with national and regional leaders of the three parties that were involved in government formation negotiations in Andalusia, Madrid, and Murcia.[2] We interviewed at least one person from each party, for each region. Of the 16, four were national party representatives and twelve were regional party negotiators. There were five interviews on Andalusia, five on Madrid and four on Murcia. The remaining two covered the parties’ government formation strategies more broadly across all regions.

We examined press releases (PRs) from the national parties’ central offices between March 2019, a month before the national parliamentary elections, and August 2019, when all regional governments had formed.[3] Our newspaper analysis includes El País (EP) and El Mundo (EM) coverage of government formation in Andalusia, Madrid and Murcia, and the period a month before and after general elections of April 28, 2019. Since Murcia was not covered as extensively in the national newspapers, we also examined a local paper, La Opinión de Murcia (OM).[4]

We organize the empirical discussion as follows: we summarize the strategic environment in Spain prior to and necessary for contextualizing the regional government formation processes, then analyse Andalusia (December 2018 to January 2019). Subsequently, we discuss the early April 2019 national parliamentary elections and their impact on the strategic environment. An analysis of Madrid and Murcia follows. Government formation negotiations occurred concurrently between May and August 2019, while the national parliament failed to form a government.

THE STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENT IN SPAIN (2015-2018)[Up]

This section presents the competitive environment in which the parties operated between 2015 and 2018. In 2015, Podemos and Ciudadanos entered the national parliament, undermining the dominance of the centre-left Socialist Party (PSOE) and the conservative PP in national politics (Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio, 2016). This was due in part to consequences of the great recession, and frustration with Spain’s political system, including corruption. Spain’s party system has strong left-right and centre-periphery dimensions. Important for our analysis, Cs offered democratic renewal, liberal social values, liberal economic policies, and a defence of Spanish national identity.

In the 2015/2016 cycle of elections, Cs prioritized policy over office and opted not to try to govern (Interviews 1, 3). Important for our analysis, in 2015, Cs was willing to support a PSOE national government, though parliamentary arithmetic prevented it. Spain held parliamentary elections again in 2016, after failing to form a government. Eventually, PP, led by PM Mariano Rajoy, governed with the external support of Ciudadanos and a few small parties. In 2015 and 2016, Cs also entered regional parliaments for the first time. Where relevant, it supported governments of PP or PSOE from parliament. Table 1 presents the election results from the 2015/16 and 2018/19 election cycles at the national level and in the three regions we examine ahead.

Table 1.

Election Results

| Andalusia | Madrid | Murcia | Spain | Spain | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional | Regional | Regional | National | National | ||||||||

| Mar 2015 | May 2015 | May 2015 | Dec 2015 | Jun 2016 | ||||||||

| Vote (%) | Seats (#) | Vote (%) | Seats (#) | Vote (%) | Seats (#) | Vote (%) | Seats (#) | Vote (%) | Seats (#) | |||

| PP* | 26.7 | 33 | 33.1 | 48 | 37.4 | 22 | 28.7 | 123 | 33.0 | 137 | ||

| PSOE | 35.4 | 47 | 25.4 | 37 | 24 | 13 | 22.0 | 90 | 22.6 | 85 | ||

| Cs | 9.3 | 9 | 12.1 | 17 | 12.5 | 4 | 13.9 | 40 | 13.1 | 32 | ||

| Podemos[*] | 14.9 | 15 | 18.6 | 27 | 13.2 | 6 | 20.7 | 69 | 21.2 | 71 | ||

| Vox | 0.5 | 0 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | ||

| IU[*][^] | 6.9 | 5 | 4.1 | 0 | 4.8 | 0 | 3.7 | 2 | – | – | ||

| Más Madrid | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Others | 6.3 | 0 | 5.5 | 0 | 7.2 | 0 | 10.8 | 26 | 9.9 | 25 | ||

| Seat Total | 109 | 129 | 45 | 350 | 350 | |||||||

| Majority (50%+1) | 55 | 65 | 23 | 176 | 176 | |||||||

| Government: | ||||||||||||

| Party | PSOE (1982) | PP (1995) | PP (1995) | PP (2011) | PP (2016-18) | PSOE (2018-19) | ||||||

| Status | Minority | Minority | Minority | Caretaker | Minority | Minority | ||||||

| Support | Cs | Cs | Cs | Cs + others | Podemos+others | |||||||

| Andalusia | Spain | Madrid | Murcia | Spain | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional | National | Regional | Regional | National | ||||||

| Dec 2018 | Apr 2019 | May 2019 | May 2019 | Nov 2019 | ||||||

| Vote (%) | Seats (#) | Vote (%) | Seats (#) | Vote (%) | Seats (#) | Vote (%) | Seats (#) | Vote (%) | Seats (#) | |

| PP[*] | 20.8 | 26 | 16.7 | 66 | 22.2 | 30 | 32.4 | 16 | 20.8 | 89 |

| PSOE | 27.9 | 33 | 28.7 | 123 | 27.4 | 37 | 32.4 | 17 | 28.0 | 120 |

| Cs | 18.3 | 21 | 15.9 | 57 | 19.4 | 26 | 12.0 | 6 | 6.8 | 10 |

| Podemos[*] | 16.2 | 17 | 14.3 | 42 | 5.6 | 7 | 5.6 | 2 | 12.8 | 35 |

| Vox | 11.0 | 12 | 10.3 | 24 | 8.9 | 12 | 9.5 | 4 | 15.1 | 52 |

| IU[*][^] | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 0 | – | – |

| Más Madrid | 14.7 | 20 | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Others | 5.8 | 0 | 14.1 | 38 | 1.8 | 0 | 6.1 | 0 | 16.5 | 44 |

| Seat Total | 109 | 350 | 132 | 45 | 350 | |||||

| Majority (50%+1) | 55 | 176 | 67 | 23 | 176 | |||||

| Government: | ||||||||||

| Party/Parties | PP+Cs | PSOE | PP+Cs | PP+Cs | PSOE+Podemos | |||||

| Status | Minority | Caretaker | Minority | Minority | Minority | |||||

| Support | Vox | Vox | Vox | Others | ||||||

| [^] |

Allied with Podemos in 2016 & 2019 national elections, 2019 Madrid Elections. Parentheses on Party indicate the year the party took office. |

Sources: Ministerio del Interior; Parlamento de Andalucía; El País.

In 2017, tensions regarding Catalonia rose. In October, the Catalan regional government held an independence referendum, defying a constitutional court ruling. While national authorities suspended Catalonia’s autonomy in response, pro-independence parties returned to power in Catalonia. Then, triggered by PP’s conviction for corruption, the Rajoy government was brought down in a constructive vote of no confidence in 2018. It also brought Socialist PM Pedro Sánchez and the PSOE into power (see Table 2). The alliance that made that possible included Unidos Podemos (UP) and a variety of regionally-based parties, including some pro-independence Catalan and Basque parties. While Ciudadanos withdrew its support for the PP government, it did not support the motion.

Table 2.

Timeline of Events

| 1 June 2018 | Constructive vote of no confidence against PM Rajoy (PP) |

| Simultaneous investiture of PM Sánchez (PSOE) | |

| 21 July 2018 | Pablo Casado elected PP party leader |

| 2 December 2018 | Regional Elections—Andalusia |

| 16 January 2019 | Investiture—Andalusia, Moreno (PP+Cs+Vox) |

| 10 February 2019 | Colón demonstration |

| 15 February 2019 | PM Sánchez calls elections for 28 April 2019 |

| February-June 2019 | Trail (oral arguments) of Catalan independence leaders |

| 28 April 2019 | General Elections—Spain (Regional Election—Valencia) |

| 26 May 2019 | Local, Regional (12 Regions), & European Elections |

| 2-4 July 2019 | Failed investiture—Murcia, López Miras (PP) |

| 10 July 2019 | Failed investiture—Madrid, no candidate |

| 22-25 July 2019 | Failed investiture—Spain, Sánchez (PSOE) |

| 26 July 2019 | Investiture—Murcia, López Miras (PP+Cs+Vox) |

| 14 August 2019 | Investiture—Madrid, Díaz Ayuso (PP+Cs+Vox) |

| 10 November 2019 | General Elections—Spain |

| 11 November 2019 | Albert Rivera resigns as Cs party leader |

| 4-7 January 2020 | Investiture—Spain, Sánchez (PSOE+UP+others) |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

In this context, Cs believed it could overtake PP electorally and lead on the political right. National identity issues were salient due to the context as well as the parties’ strategic choices. Competition between PP and Cs centred on their Spanish nationalist credentials (Alonso and Field, 2021; Rodríguez-Teruel, 2020) and opposition to the Sánchez government and its allies. Cs moved to the right (Rodríguez-Teruel, 2020: 16). This preceded Vox’s electoral breakthrough, which occurred in the Andalusian regional elections in December 2018. A split from PP in terms of some of its leadership and voter base, Vox stresses Spanish nationalism, nativism, ultraconservative social values, and liberal economic policy (Ferreira, 2019; Rama et al., 2021).

In the 2018/19 cycle of regional elections, the national identity dimension of party competition dominated, and policy positioning was in part endogenous to the government formation decisions we analyse. The next sections seek to explain the mainstream right’s acceptance of Vox as a support party, and Vox’s acquiescence.

GOVERNMENT FORMATION IN THREE REGIONS[Up]

A few empirical observations are relevant to all regions. First, the left parties rejected supporting or actively facilitating a right-wing government of PP and Cs, which limited the governing options. However, the Socialist PSOE was willing to ally with Cs. We focus on the decisions of the right-wing parties. Second, the investiture vote in the parliaments is only on the candidate to lead the government, which shaped the negotiation processes. Finally, the national party leaderships of PP, Cs and Vox were heavily involved in the governance decisions in all three regions and able to impose their preferred outcome on their regional party branches, where their preferences conflicted.

Andalusia, December 2018-January 2019 [Up]

The Socialist Party (PSOE) had been governing Andalusia since 1982, with Cs’ external support since 2015. The December 2018 regional election gained significant national attention in part because Vox’s surprise breakthrough attracted extensive media coverage. It was also the beginning of a new political cycle, following PP’s ouster from the Spanish government and with multiple fixed-calendar elections due in May 2019.

The Socialist Party won the most votes (28 percent) and seats, though it lost support from 2015 (35 percent) (see Table 1). PP also declined significantly from 27 percent in 2015 to 21 percent. Cs doubled its support from 9 to 18 percent. Vox entered parliament with far more weight than expected and 11 percent of the vote. Podemos increased its vote share modestly from 15 to 17 percent.

Two governing formulas comprised the political options: a right-wing government that required cooperation between PP, Cs and Vox; or a left-leaning government that required cooperation between the Socialists, Podemos and Cs. Government formation discussions centred overwhelmingly on the right-wing formula. Our analysis shows that each party’s regional and national goals aligned. PP and Cs sought to balance office and vote goals, while Vox pursued policy concessions and legitimacy to gain votes. This pointed to collaboration between the three right parties. The central party branches of PP (Interview 6, 7), Cs (Interview 1) and Vox (Interview 2) closely managed the government formation discussions (EP 7.12.2018; EP 27.12.2018; EP 8.1.2019). At times, the central party leaders negotiated amongst themselves without the relevant Andalusian politicians present.

PP: The Government Broker Party. PP has long been an office-seeking party. Even so, the party’s focus on governing was particularly strong in Andalusia. The election marked a low point for PP, tainted by corruption and having lost the Spanish government in the censure vote. Additionally, poor results in the 2015 regional elections had left it weakened in the regions. Its new leader, Pablo Casado, needed to consolidate his leadership after a divisive internal party election in July 2018. At a practical level, the party also needed offices for its cadres.

In Andalusia, the party had long striven to dislodge the Socialists from power (Interview 6). When the parliamentary arithmetic showed a right-wing government was possible, PP was very receptive to an alliance with Cs. Also, Casado would not discard the possibility of Vox entering the government, rejecting that it was a ‘dangerous’ party (EP 4.12.2018; EM 2.12.2018). When asked why PP accepted Vox as a potential ally, one interviewee pointed to simple parliamentary arithmetic and personal relationships with Vox leader Santiago Abascal, who had been a member of PP (Interview 7).

The national party leadership very rapidly viewed the alliance of PP, Cs, and Vox as a model for future governments (EM 27.12.2018). Though PP was weaker electorally, it recognized it could potentially govern in more places (‘fewer votes, more governments,’ EP 11.1.2019). Taking the Andalusian premiership was non-negotiable (EP 9.12.2018; EM 4.12.2018). The party leadership portrayed itself as the ‘central’ party, capable of brokering a right-wing government that it led.

In terms of vote goals, the national party leadership wanted to hold its lead position on the political right. In the party’s strategic thinking, once it was in power, it would try to reincorporate Vox (and Vox voters), which it saw as a split from the Popular Party (Interview 7). It therefore needed to be careful how it treated the party. In their view, Vox voters were former PP voters. The PP leadership thought their own voters would understand an agreement with Vox. And PP’s voters wanted them to govern (EM 30.12.2018). The national leadership also hoped to reunite the right, including Cs, under a big tent, as had occurred under Jose María Aznar in the early 1990s. They recognized the left would try to use an agreement with Vox against them (Interview 6).

In policy terms, the national PP had shifted right under Casado, though PP’s Andalusian leader, Juanma Moreno, was considered a moderate (EM 7.1.2019), aligned with Casado’s competitor in the prior leadership contest. Given its office goals, the central party leadership was receptive to making policy concessions in programmatic negotiations with Cs, which it did not consider difficult due to overlapping positions (Interviews 6, 7). The PP’s negotiating team considered Vox’s initial policy demands ‘crazy’ and ‘unacceptable’, yet it viewed the final deal as one that was ‘sensible’ (Interviews 6, 7). They recognized areas of agreement with Vox, such as the unity of Spain, defending traditions, and the economy, as well as areas of strong disagreement (Interview 6). The PP’s challenge was to negotiate a document with Vox that would be acceptable to Cs (Interview 7), while Cs refused to sit at the negotiating table or sign an agreement.

The PP viewed national and regional goals generally as compatible, without significant disagreements between the party organizations. They could dislodge the Socialists from one of its feuds. PP would lead the government under Moreno and hold on to its position as the main opposition to the Socialists. Already suffering electorally, they did not foresee high electoral costs. Some in the party, however, disagreed (Interview 7). After PP and Vox signed an agreement, they warned: ‘If we do what Vox does, they will vote for Vox’ (EM 6.1.2019). However, dissent did not provoke an internal crisis, and abated once the final agreement was known (EP 11.1.2019).

Cs: The Pursuit of Electoral Leadership on the Right. Ciudadanos’ central party leadership, under Albert Rivera, had made it a strategic priority to govern in the regions (Interview 1), which the party in Andalusia shared (Interviews 3, 4). As an external support party in Andalusia and elsewhere, Cs had found it difficult to get its policies implemented. The party thought it now had the experience and personnel to govern and implement its policy priorities. Its surge in popular support in Andalusia reinforced its aspiration to govern (EM 3.12.2018). However, the national party leadership prioritized vote goals in Spain more broadly, seeking to surpass PP and become the lead party on the political right. The leadership only viewed regional office and national vote goals as compatible if governing did not involve the left.

In Andalusia, Cs’ choices determined the viability of the right or left-leaning government formulas. Cs had promised during the campaign not to ally with the Socialists, though at a time when it thought the left parties would win enough seats to govern alone (Interview 3). During the campaign, Cs’ regional leader, Juan Marín, also discarded making deals with Vox, at a time when its future relevance was unknown (EP 4.12.2018).

Immediately after the election, Cs’ national leadership would not discard any governing formula (EP 4.12.2018; EM 3.12.2018), suggesting a willingness to work with Vox. Subsequently, Cs distanced itself from Vox, refusing to negotiate with the party directly, though recognizing that any PP+Cs government would need Vox’s support to form. Cs then decided to negotiate directly only with PP on a government that would not give Vox government posts.

The wavering was at least in part a response to strong internal party divisions about the central party leadership’s refusal to ally with the Socialists (EM 10.12.2018), which would make the party reliant on Vox to govern. Cs also faced criticism and pressure from European liberals, such as France’s President Emmanuel Macron (EM 9.1.2019). Neither steered the party leadership away from a deal with PP that would require Vox’s support. Cs’ leaders recognized rumbling from European liberals but stressed Vox would not be in the government and that many European parties had already governed with or depended on the support of radical right parties (Interview 1).

The party’s choice of governing alliance in Andalusia exhibited the central party leadership’s vote-seeking strategy to become the primary opposition to the Socialists in Spain. When we asked why Cs was not open to an alliance with the Socialists in Andalusia, a Cs executive committee member stated: ‘That has a lot to do with the national situation, which is that we consider PSOE to be absolutely off balance (descentrado) about the idea of what Spain is’ (Interview 1). The right parties lambasted the Socialists for their willingness to collaborate with secessionists and the radical left.

This left PP and Cs to negotiate a programmatic agreement and coalition government structure, and PP to separately negotiate a support agreement with Vox. In the programmatic negotiations between Cs and PP, PP accepted many of Cs’ demands (EP 26.12.2018; Interview 3). In exchange, PP took the premiership. Cs recognized that the investiture of the PP candidate required a deal with Vox (Interviews 1, 6). Because the investiture vote is only on the candidate to head the government, Cs claimed that it did not need Vox’s votes, PP did. Cs refused to negotiate directly with the party, would not sign a joint document or share a publicity photograph, and would not tolerate a PP+Vox deal that compromised its own agreement with PP.

In policy terms, Cs recognized areas of proximity across the three parties, particularly on economic and national identity questions. There were other areas of stark contrasts, particularly on social issues, which the party had made secondary. Ultimately, Cs’ representatives claimed that there was nothing in the final PP+Vox agreement that was unacceptable (Interview 3).

Electorally, Cs did not see Vox as a threat. Given that Cs and Vox both increased their votes in the Andalusian election, Cs thought Vox was an electoral problem for PP (Interview 1). It also thought that its own voters would understand the party’s decision to dislodge the Socialists from power in Andalusia after nearly four decades, which was compatible with the party’s commitment to democratic renewal and campaign promise (Interviews 1, 3). The party nonetheless knew the left would accuse it of coming to power at the hands of Vox (Interview 3).

Vox: Policy and Legitimacy for Votes. Vox did not expect to win so many seats or to be relevant for government formation (Interview 2). The party never had a serious discussion about trying to enter government (Interviews 2, 5). The day after the election, Vox’s national and regional leaders stated in public that Vox would not be an obstacle to removing the PSOE from office (EP 3.12.2018). The party’s national and regional goals were in synch. The party sought legitimacy as a pathway to gain votes.

From the party’s perspective, electoral success in Andalusia, after five years of failures, was an opportunity to gain policy concessions and deliver for its voters (Interviews 2, 5). In the words of its regional leader Francisco Serrano, ‘Vox won’t demand offices’ but ‘neither will we allow them to ignore us.’ Speaking about a possible negotiation, he stated: ‘one thing is that we go with humility and another that they treat us with contempt…Our party as well as our voters deserve to be treated with dignity’ (EP 12.12.2018).

Strategically, the party sought a formal tripartite policy agreement with PP and Cs, cemented with a public appearance of the three parties to forestall a sanitary cordon (EM 21.12.2018). While Cs refused, Vox got a formal agreement and recognition from PP. Vox indicated it was looking for a minimal agreement that reflected its parliamentary weight (Interviews 2, 5). However, it presented a preliminary document and made it public, to the surprise of its PP interlocutors (EP 9.1.2019; Interview 7). A Vox leader asserted that they wanted to make their demands transparent to their (potential) supporters, while recognizing that some were symbolic (Interview 2). Subsequently, PP and Vox forged a compromise agreement, including commitments in the areas of family policy, education, culture, immigration and historical memory. Signed by the parties’ national general secretaries and regional party leaders on 9 January 2019, the agreement committed Vox to support the PP candidate for regional premier in a first-round vote.

Vox also won symbolic victories. For example, there was a public photo of its national general secretary, Javier Ortega, and PP general secretary, Teodoro García Egea, signing an agreement in the Andalusian parliament on the governing board of the parliament – which for Vox symbolized a formal request for support (EP 27.12.2018; EM 27.12.2018). García Egea made clear that he was ‘going to treat Vox as I would treat any party that competes in elections’ (EP 4.1.2019). Another photo important to Vox captured the signing of the formal investiture agreement (EP 10.1.2019). In the investiture debate, Vox’s regional leader Serrano said ‘Andalusia had voted for “dialogue without complexes, prejudices or sanitary cordons”’ (EP 15.1.2019).

Cs would not sit down with Vox publicly, despite continuous calls from Vox to do so. Cs only committed to the measures it negotiated with PP. Cs would have preferred for the government to get Vox’s support for investiture without a formal deal with PP. Vox would not acquiesce. This left Cs to try to convince the public that it did not have anything to do with the deal. Cs’ general secretary, José Manuel Villegas, stated: ‘That agreement does not obligate the coalition government or of course Ciudadanos’ deputies’ (EP 10.1.2019). However, the press reported meetings. For example, Cs’ leaders in Andalusia, Juan Marín and Ana Bosquet met with Vox’s leader in Andalusia, Francisco Serrano, to ask for his support for Bosquet to become president of the parliament (EP 28.12.2018).

PP premier candidate Juanma Moreno was elected with the support of PP, Cs and Vox on 16 January 2019. Government formation took 45 days. The two mainstream parties depicted the outcome very differently. For the PP’s national leadership, it was a model for the future. In contrast, Ciudadanos presented the Andalusian situation as ‘exceptional’ due to decades of Socialist rule. It referred to the agreement between Vox and PP as ‘papel mojado,’ which roughly translates to ‘not worth the paper it’s printed on’ (EP 11.1.2019).

Spain, General Parliamentary Elections, April 2019 [Up]

In the months between the elections in Andalusia and the fixed-calendar May 2019 European, local and regional elections, political tensions in Spain were high. PM Sánchez was governing in minority with the support of a combination of radical left and regional and regional-nationalist parties, including Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC), which had supported the independence push in Catalonia.

The right-wing parties continued to compete particularly over their Spanish nationalist credentials, outbidding one another (Simón, 2020b: 534), and animosity toward the Socialist government. Symbolic of the time, PP and Cs called a demonstration in Colón Plaza in Madrid on 10 February 2019 to demand elections and end the government’s negotiation with secessionists. In an environment replete with Spanish flags, the national leadership of the three right parties—Pablo Casado (PP), Albert Rivera (Cs) and Santiago Abascal (Vox)—appeared together, a symbol of their increasing engagement. Soon after, the Sánchez government’s 2019 budget bill was defeated in parliament. On 15 February, PM Sánchez called early elections for the Spanish parliament, which would occur in April. February also marked the beginning of oral arguments in the trial of Catalan independence leaders.

In the April 2019 general elections, PP suffered a severe decline from 33 percent of the vote in 2016 to less than 17 percent (see Table 1). Cs increased its vote share to nearly 16 percent, making Cs’ electoral goal of overtaking PP appear within reach. Vox entered the national parliament for the first time. Yet there was no right-wing majority. Pedro Sánchez had two alternatives to pursue: an agreement between the PSOE and Cs (whose MPs jointly held a majority), which Cs’ central executive committee had formally ruled out before the elections as part of its vote-maximizing strategy (Simón 2020b: 534), or a leftist government supported by some combination of leftist and regional-nationalist parties. With a new government pending in Spain, regional elections occurred in May 2019.

Madrid and Murcia, May-August 2019 [Up]

The circumstances in Madrid and Murcia differed considerably among themselves and from Andalusia. Madrid and Murcia were bastions of PP’s regional power. It had governed in both since 1995, with Cs’ external support since 2015. In the May 2019 elections in both regions, PSOE was the most voted party, followed by PP, and then Cs. Vox was fourth in Murcia and fifth in Madrid (see Table 1). While Cs’ vote share increased significantly in Madrid and PP’s declined in both, Cs did not surpass PP. According to PP leader Pablo Casado, it was a ‘good bad result’ (EP 26.5.2019).

The Andalusian formula of collaboration between PP, Cs and Vox was numerically possible in both regions. PP’s goals and strategy did not change. Regional and national goals aligned, and the party prioritized governing. Similarly, Vox’s vote- and policy-seeking priorities remained the same; however, it learned from Andalusia to make better strategic use of its bargaining position (EP 27.5.2019).

For Cs, there were more vexing trade-offs between policy, office and vote goals across territorial levels. Unlike in Andalusia, the right-wing alliance was not compatible with the democratic regeneration that had been important to Cs, given PP’s long tenure in power in Murcia and Madrid. There were other options. An agreement between PSOE and Cs in Murcia could produce a majority coalition that would give Cs more power and accomplish turnover. In Madrid, in contrast, an alliance of PSOE and Cs would not be enough. In Murcia, Cs’ national party and part of the regional party organization disagreed over strategy. Ultimately, Cs’ national leadership and the national electoral goal won out. This led to a repeat of the Andalusian formula, despite distinct circumstances in all three regions.

As in Andalusia, the central party offices of PP (Interviews 12, 16), Cs (Interviews 1, 9, 13) and Vox (Interview 14) closely managed the government formation negotiations.

PP: ‘Governments of Freedom’ to Stay in Office. As in Andalusia, PP continued to prioritize governing in the regions, while simultaneously pursuing the longer-term electoral aim of rebuilding its hegemony on the right (Interviews 6, 7, 11, 12, 16; PRs 24.5.2019, 1.7.2019).

Our interviews suggest that PP did not have a red line that Vox could not enter governments. In Madrid, the party contemplated various scenarios before knowing what Vox would demand (Interview 11), while in Murcia governing with Vox was not seriously on the table, ‘neither was it discarded’ (Interview 16). In both regions, PP knew it was a nonstarter for Cs (Interview 11, 12, 16). Regarding policy, according to PP, the three parties shared positions on core issues such as low taxation, parents’ freedom to choose the education of their children, equality of opportunity for all Spaniards, and the unity of the Spanish nation (PR 1.6.2019; Interview 6; OM 3.6.2019). In terms of votes, PP did not view Vox’s support in Andalusia as having had electoral costs (Interviews 6, 12). PP thus relied on Andalusia as a model for the negotiations (Interview 7; several PRs between 24.5.2019 and 30.6.2019).

Unlike in Andalusia, PP could not use the urgency of democratic renewal as an argument in its own strongholds. Instead, it continued to delegitimize the PSOE, accusing it of ‘whitewashing’ terrorists, separatists, and left extremists, referring to the ongoing negotiations between PSOE and the radical left Basque independence party, EH-Bildu, on government formation in Navarre (PRs 1.6.2019, 20.6.2019). Since the unity of Spain and preventing left-wing governments were core goals of Vox and Cs, this put pressure on both parties to facilitate right-wing governments (PR 5.6.2019, Interviews 11, 12, 16). PP referred to the tripartite collaboration as ‘governments of freedom’ (PRs 16.6.2019, 25.6.2019).

Ultimately, negotiations in Murcia and Madrid occurred in three different arenas: PP and Cs, PP and Vox, and the three parties together. The agreements between PP and Cs were relatively easy to achieve (EP 8.7.2019). These bilateral agreements, however, infuriated Vox, whose leadership demanded a tripartite negotiation, which Cs initially rejected. This meant protracted negotiations to get Vox’s support.

Cs: Prioritizing National Electoral Interests in the Regional Arena. Cs’ regional office-seeking and national vote-seeking goals conflicted. The priority of the regional party branches in Murcia and Madrid was to govern; the priority of the national leadership was to surpass PP electorally in Spain. To do so, the national leadership thought it had to avoid governing with the PSOE and keep a safe distance from Vox. Party leader Albert Rivera stated that Cs would not negotiate or participate in coalition governments with Vox (EP 31.5.2019), while simultaneously rejecting the PSOE as a coalition partner in Murcia and Madrid.

In Murcia, a majority coalition with the PSOE, which the PSOE wanted, was compatible with Cs’ emphasis on democratic regeneration, and would divide power among fewer parties. This was the option most compatible with an office-maximizing strategy. A right-wing government would require sharing power with PP plus concessions to Vox, which Cs had promised not to do after Andalusia. Moreover, Cs would not be able to characterize its reliance on Vox as ‘exceptional’ and necessary for democratic renewal, as it had done in Andalusia (Interview 13). During the week after the election, Cs-Murcia negotiated simultaneously with PP and PSOE. PSOE offered Cs the mayor’s office in the city of Murcia to sweeten the regional government negotiation (EP 8.6.2019). Cs-Murcia seemed open to negotiating with PSOE. During the electoral campaign and immediately after the election, Cs-Murcia’s spokesperson, Isabel Franco, declared they wanted to ‘end the exhausted government of the Popular Party, tainted by its numerous cases of corruption’ (Cs PR 19.5.2019).

In Madrid, PSOE also tried to negotiate with Cs, offering the party the mayor’s office in the city of Madrid as part of a regional deal. Yet the leader of Cs-Madrid, Ignacio Aguado, ruled out a deal with PSOE early on (EP 27.5.2019; 30.5.2019). Cs-Murcia, by contrast, was split in its preference to pact with PSOE or PP (Interview 13).

Cs’ national leadership saw PP as the ‘preferential’ partner across all regions of Spain (EP 29.5.2019; EM 6.6.2019). In the fight to electorally surpass PP, Spanish nationalism was the battleground (Cs PRs 29.3.2019, 4.4.2019, 12.4.2019, 24.4.2019), which all three right parties emphasized. Nationally, where a government had yet to form, Cs also refused to form a majority coalition with the PSOE. Like PP, Cs argued that the PSOE had no legitimacy to govern Spain since it was a party that negotiated with separatists, terrorists, and left extremists (Cs PR 24.6.2019).

Cs’ strong performance in the April and May 2019 elections gave Cs-Spain another argument in favour of partnering with PP in Murcia. The national party leadership interpreted it as confirmation that its dependence on Vox in Andalusia had no electoral costs. On the contrary, the national vote-seeking strategy was bearing fruit (Interview 1). Under pressure from Cs’ national leadership, Cs-Murcia eventually abandoned the negotiations with PSOE, despite internal division (EP 31.5.2019).

For Cs’ national leadership, the model for Madrid and Murcia was Andalusia: a minority government of PP and Cs with external support from Vox, without negotiating directly or signing an agreement with Vox (EP 31.5.2019). The party adamantly rejected Vox as a coalition partner. It again tried to keep a distance from Vox by letting PP negotiate its support for the investiture of PP’s candidates, Fernando López Miras in Murcia, and Isabel Díaz Ayuso in Madrid. Meanwhile, PP and Cs signed a programmatic agreement on 20 June in Murcia (Cs PR 20.6.2019) and in Madrid on 8 July.

In Murcia, Cs’ initial inflexible position towards Vox changed after Vox refused to support the PP candidate in the first investiture vote on 4 July (Cs PR 10.7.2019). It forced Cs to recognize Vox as an interlocutor (Cs PR 10.7.2019). The three parties reached an agreement for the investiture of López Miras on 19 July. As Cs demanded, the agreement was only verbal. There was no document signed by the three parties (EM 19.7.2109). As Vox demanded, PP and Cs presented their policy agreement publicly with Vox during the investiture debates (EM 26.7.2019). López Miras described the agreement as ‘totally acceptable’ and ‘compatible’ with the PP-Cs coalition agreement. Isabel Franco referred to it as ‘not incompatible’ with it (EM 19.7.2019).

Similarly, in Madrid, with the legal deadline to form a government approaching, Vox forced an investiture vote without a candidate on 10 July (EP 10.7.2019). This eventually pushed Cs into a tripartite negotiation (EP 11.7.2019). The agreement in Murcia served as the template for Madrid, according to Vox’s leader in Madrid, Rocío Monasterio (EP 11.7.2019; 24.7.2019). Finally, on 1 August, the three parties verbally agreed on a joint list of measures that sealed the investiture of PP’s Díaz Ayuso (EP 2.8.2019; EM 2.8.2019). As in Murcia, PP and Cs presented the policy agreement with Vox during the investiture debates (EM 13.8.2019). Cs-Madrid’s leader, Ignacio Aguado, described the agreement as ‘not incompatible with our bilateral pact with PP’ and, therefore, as ‘perfectly acceptable’ (EP 14.8.2019).

Vox: Doubling Down on Political Legitimacy and Policy Influence for Votes. Vox continued to pursue political legitimacy and policy influence as a pathway to votes, though with greater resolve. Vox was a more forceful and strategic negotiator in Murcia and Madrid than it had been in Andalusia. The radical right party wanted the recognition and legitimacy of a tripartite negotiation (EP 8.7.2019).

Vox had learned a lesson in Andalusia (EP 27.5.2019; EM 2.7.2019). Soon after the elections, Vox warned PP and Cs that they would need to sit at the negotiating table jointly if they wanted to govern (EP 27.5.2019; OM 12.6.2019). Vox’s national leader, Santiago Abascal, said that Vox would not accept ‘insults, sanitary cordons, or stigmas’ (EP 27.5.2019). Vox leaders in Murcia (OM 27.5.2019) and Madrid (EP 27.5.2019) echoed the message. Vox’s demand for recognition triggered an arduous multi-layered negotiation process involving the three parties and their national and regional organizations.

Despite early demands for posts in the governments of Madrid and Murcia, Vox’s priority was not yet office (EP 27.5.2019; OM 12.6.19; Interviews 2, 14, 15). According to the party, influence over policies would give it the desired legitimacy and credibility as a party of principles that can bring about change. They considered office to be risky because it would constrain the party’s behaviour and rhetoric. It also could be electorally costly to share office with a PP tainted by corruption. According to a Vox-Madrid leader, PP offered Vox subcabinet positions that they decided not to take (Interview 10). Also, the party was not yet ready for office. It was still engaged in building a party organization (Interview 14). Instead, the party thought supporting the formation of a government from parliament would send a strong message of responsibility, sacrificing immediate rewards (government portfolios) to prevent left-wing governments and ending the ‘ideological hegemony’ of the left in Spain (Interviews 2, 5, 10, 14, 15). Vox’s policy-seeking and vote-seeking goals aligned, and it deferred gaining office.

Vox’s strategy toward the first investiture votes in Madrid and Murcia, discussed previously, showed its resolve and veto power. This compelled Cs to sit at the negotiating table. During these negotiations, PP and Cs convinced Vox to water down its most radical policy demands, among them the repeal of the LGTBi+ Law (OM 18.7.2019; Interview 16). Ultimately, the PP candidates for the premierships were elected on 26 July 2019 in Murcia and 14 August in Madrid, each with the support of PP, Cs and Vox. In contrast to Andalusia, where government formation took 45 days, it took 61 days in Murcia and 80 in Madrid.

CONCLUSIONS[Up]

This article set out to explain why the mainstream right in Spain rapidly collaborated with Vox as a support party, and why Vox agreed. To do so, we examined the parties’ policy, office and vote goals in multilevel perspective. While parties’ office and policy goals were clearly important, only when we also consider electoral goals in multilevel perspective can we account for why the mainstream and radical right allied in Spain. Beginning in Andalusia, PP prioritized governing in the regions, with the longer-term national electoral goal of uniting the right. It viewed a governing alliance with Cs and Vox as compatible with both. Vox pursued recognition as a legitimate party and policy influence as a pathway to votes across Spain, and it progressively became more assertive. Governing could wait, and the party strategically worked to block a sanitary cordon that could hinder its future. In both parties, national and regional goals aligned.

In contrast, Cs faced distinct trade-offs in different regions, and at times conflicting goals in the national and regional arenas. Despite varying conditions in the regions, its national electoral goal of becoming the lead party on the right led it to eschew governing with the PSOE, which meant it would need Vox to govern. Recognizing the potential costs of proximity to Vox, it tried to keep a distance from it. This became progressively more difficult because of its inherent contradictions and pressure from Vox.

This study makes several contributions to the comparative literature on cooperation between the mainstream and the radical right. First, as just described, our multilevel analysis helps account for governing outcomes that appeared anomalous in single-level perspective. Second, it demonstrates that a mainstream party’s vote-maximization strategy can, perhaps counter-intuitively, lead to engagement with the radical right to govern. In Spain, electoral competition among the mainstream right parties and Cs’ goal of surpassing PP led it to tolerate the radical right Vox as a governing ally. Third, it provides further evidence that radical right parties are strategic and can constrain mainstream party choices. In Spain, Vox pushed Cs to give it more recognition than the latter had wanted.

The study also contributes to understanding the development of polarising, two-bloc politics in Spain, which encompassed engagement with the radical right. It provides further insight into how the right bloc developed and solidified, and the constitutive role of party decisions in the regions. Thus, it demonstrates the utility of adding a subnational perspective to our studies of the radical right and mainstream party strategies, not simply as another or separate arena, but also as an integral component of party strategies. In Spain, we argue, the choices made in the regions constitute overall party strategies. The national party leaderships were heavily involved in the decisions and able to impose their preferred strategies on regional party branches when they conflicted. In cross-national perspective, the degree to which choices in the regions constitute national party strategies depends on who in the party makes decisions about government formation. In decentralized parties, regional party branches may be better positioned to make autonomous decisions and thus mainstream-radical right governing alliances may be less indicative of overall party strategies.

We hope this study helps generate additional research on the consequences of mainstream-radical right engagement in the executive arena. One strand of literature defends that mainstream parties’ accommodative strategies towards the radical right help to reduce its strength and undermine its success (Meguid, 2008) while another claims accommodation legitimizes and contributes to its successful consolidation (Arzheimer and Carter, 2006; Dahlström and Sundell, 2012; Krause et al., 2023). We suspect that the government formation decisions in Spain affected the parties’ subsequent trajectories. Today, it is Cs that is nearly irrelevant in Spanish politics, with many of its leaders having abandoned it for PP and the party’s decision not to run candidates in the July 2023 general elections. In contrast, Vox became Spain’s third largest party in the national parliamentary elections held in November 2019. In 2022, Vox first governed in coalition with PP in the region of Castile and Leon. While parliamentary arithmetic in the aftermath of the 2023 national parliamentary elections did not permit a PP-Vox government, the two currently govern together in many of Spain’s regions and municipalities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS[Up]

We thank Patricia Puig and Lourdes Solana for their research assistance, and the politicians who generously gave their time for interviews and shared their invaluable insights. We also thank Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser for his comments on a previous version of this manuscript. We thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for their helpful feedback. Bonnie Field gratefully acknowledges funding from Bentley University, Bentley Research Council. Sonia Alonso acknowledges partial funding from the Qatar Foundation/GUQ-sponsored Faculty Research Grant. The authors contributed equally to the study and are listed in reverse alphabetical order.

NOTES[Up]

| [1] |

While there is agreement in the literature that Vox is a radical right party, a body of literature contends that the party cannot be characterized as populist, at least in the early stages of its existence (Arroyo Menéndez, 2020; Balinhas, 2020; Ferreira, 2019; Ortiz and Ramos-González, 2021; Turnbull-Dugarte, 2019). |

| [2] |

We sought to interview at least one person from each party who was directly involved in government formation negotiations in each region, as well as a representative from each party who was involved in setting party strategy broadly. We were unable to interview a PP representative on broad party strategy. We identified the parties’ negotiators in the press and through other interviewees. Per human subjects’ approval, interviewees signed a formal consent form in advance of the interview and were offered anonymity. |

| [3] |

Since Vox did not issue many press releases, we also examined press releases from Vox’s parliamentary group once it formed after the April 2019 general elections. |

| [4] |

Due to the numerous references to news articles and press releases, we refer only to the source abbreviation and date of publication (day.month.year) in in-text citations. |

References[Up]

|

Abou-Chadi, Tarik and Werner Klause. 2020. “The causal effect of radical right success on mainstream parties’ policy positions: a regression discontinuity approach”, British Journal of Political Science, 50 (3): 829-47. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000029 |

|

|

Akkerman, Tjitske, Sarah L. De Lange and Matthijs Rooduijn, eds. 2016. Radical right-wing populist parties in Western Europe. Into the mainstream? London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315687988 |

|

|

Albertazzi, Daniele and Davide Vampa, eds. 2021. Populism and new patterns of political competition in Western Europe. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/ 9780429429798 |

|

|

Alonso, Alba and Julia Espinosa-Fajardo. 2021. “Blitzkrieg against democracy: gender equality and the rise of the populist radical right in Spain”, Social Politics, 28 (3): 656-81. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxab026 |

|

|

Alonso, Sonia and Bonnie N. Field. 2021. “Spain: the development and decline of the Popular Party”, in Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser and Tim Bale, (eds.), Riding the populist wave: Europe’s mainstream right in crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 216-245. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009006866.010 |

|

|

Alonso, Sonia and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2015. “Spain: no country for the populist radical right?”, South European Society and Politics, 20 (1): 21-45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2014.985448 |

|

|

Arroyo Menéndez, Millán. 2020. “Las causas del apoyo electoral a VOX en España”, Política y Sociedad, 57 (3): 693-717. https://dx.doi.org/10.5209/poso.69206 |

|

|

Art, David. 2007. “Reacting to the radical right: lessons from Germany and Austria”, Party Politics, 13 (3): 331-49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068807075939 |

|

|

Art, David. 2011. Inside the radical right. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511976254 |

|

|

Arzheimer, Kai and Elizabeth Carter. 2006. “Political opportunity structures and right-wing extremist party success”, European Journal of Political Research, 45 (3): 419-43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00304.x |

|

|

Bale, Tim. 2003. “Cinderella and her ugly sisters: the mainstream and extreme right in Europe’s bipolarising party systems”, West European Politics, 26 (3): 67-90. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380312331280598 |

|

|

Bale, Tim and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2021. “The mainstream right in Western Europe: caught between the silent revolution and silent counter-revolution”, in Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser and Tim Bale, (eds.), Riding the populist wave: Europe’s mainstream right in crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1-37. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009006866.002 |

|

|

Balinhas, Daniel. 2020. “Populismo y nacionalismo en la ‘nueva’ derecha radical española”, Pensamiento al margen. Revista Digital de Ideas Políticas, 13: 69-88. |

|

|

Barrio, Astrid, Sonia Alonso Sáenz de Oger, and Bonnie N. Field. 2021. “VOX Spain: the organisational challenges of a new radical right party”, Politics and Governance, 9 (4): 240-51. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v9i4.4396 |

|

|

Capoccia, Giovanni. 2005. Defending democracy: reactions to extremism in interwar Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. |

|

|

Carter, Elisabeth. 2018. “Right-wing extremism/radicalism: reconstructing the concept”, Journal of Political Ideologies, 23 (2): 157–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2018.1451227 |

|

|

Colomer, Josep M. and Florencio Martínez. 1995. “The paradox of coalition trading”, Journal of Theoretical Politics, 7 (1): 41-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951692895 007001003 |

|

|

De Lange, Sarah L. 2012. “New alliances: why mainstream parties govern with radical right-wing populist parties”, Political Studies, 60 (4): 899-918. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00947.x |

|

|

Dahlström, Carl and Anders Sundell. 2012. “A losing gamble. how mainstream parties facilitate anti-immigrant party success”, Electoral Studies, 31 (2): 353-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.03.001 |

|

|

Downs, William M. 2001. “Pariahs in their midst: Belgian and Norwegian parties react to extremist threats”, West European Politics, 24 (3): 23-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380108425451 |

|

|

Eatwell, Roger. 2000. “The rebirth of the ‘extreme right’ in Western Europe?”, Parliamentary Affairs, 53 (3): 407–425. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/53.3.407 |

|

|

Fagerholm, Andreas. 2021. “How do they get in? Radical parties and government participation in European democracies”, Government and Opposition, 56 (2): 260-80. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2019.24 |

|

|

Ferreira, Carles. 2019. “Vox como representante de la derecha radical en España: un estudio sobre su ideología”, Revista Española de Ciencia Política, 51: 73-98. https://doi.org/10.21308/recp.51.03 |

|

|

Field, Bonnie N. 2016. Why minority governments work: multilevel territorial politics in Spain. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137559807 |

|

|

Field, Bonnie N. and Shane Martin. 2022. “Comparative conclusions on minority governments”, in Bonnie N. Field and Shane Martin, (eds.), Minority governments in comparative perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192871657.003.0016 |

|

|

Gray, Caroline. 2020. Territorial politics and the party system in Spain. London: Routledge. |

|

|

Hainsworth, Paul. 2008. The extreme right in Western Europe. Abingdon: Routledge. |

|

|

Heinze, Anna-Sophie. 2018. “Strategies of mainstream parties towards their right-wing populist challengers: Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland in comparison”, West European Politics, 41 (2): 287-309. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1389440 |

|

|

Heinze, Anna-Sophie. 2022. “Dealing with the populist radical right in parliament: mainstream party responses toward the Alternative for Germany”, European Political Science Review, 14 (3): 333-50. https://doi.org/10.1017/S17557739220 00108 |

|

|

Ignazi, Piero. 2002. “The extreme right”, in Martin Schain, Aristide Zolberg, and Patrick Hossay, (eds.), Shadows over Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230109186_2 |

|

|

Kestel, Laurent and Laurent Godmer. 2004. “Institutional inclusion and exclusion of extreme right parties”, in Roger Eatwell and Cas Mudde, (eds.), Western democracies and the new extreme right challenge. London: Routledge, 133-49. |

|

|

Krause, Werner, Denis Cohen and Tarik Abou-Chadi. 2023. “Does accommodation work? Mainstream party strategies and the success of radical right parties”, Political Science Research and Methods, 11 (1): 172-79. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2022.8 |

|

|

Luther, Kurt Richard. 2011. “Of goals and own goals: a case study of right-wing populist party strategy for and during incumbency”, Party Politics, 17 (4): 453-70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068811400522 |

|

|

Meguid, Bonnie M. 2008. Party competition between unequals: strategies and electoral fortunes in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511510298 |

|

|

Moffit, Benjamin. 2021. “How do mainstream parties ‘become’ mainstream, and pariah parties ‘become’ pariahs? Conceptualizing the processes of mainstreaming and pariahing in the labelling of political parties”, Government and Opposition, 57 (3): 385-403. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.5 |

|

|

Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511492037 |

|

|

Müller,Wolfgang C. and Kaare Strøm, eds. 2000. Coaliton governments in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Oliván Navarro, Fidel, ed. 2021. El toro por los cuernos: VOX la extrema derecha europea y el voto obrero. Madrid: Tecnos. |

|

|

Ortiz, Pablo and Jorge Ramos-González. 2021. “Derecha radical y populismo: ¿consustanciales o contingentes? Precisiones en torno al caso de VOX”, Encrucijadas. Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales, 21 (2): a2111. |

|

|

Rama, José, Lisa Zanotti, Stuart J. Turnbull-Dugarte and Andrés Santana. 2021. VOX. The rise of the Spanish populist radical right. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003049227 |

|

|

Reniu, Josep M. 2002. La formación de gobiernos minoritarios en España, 1977-1996. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. |

|

|

Rodríguez-Teruel, Juan. 2020. “Polarisation and electoral realignment: the case of the right-wing parties in Spain”, South European Society and Politics, 25 (3-4): 381-410. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2021.1901386 |

|

|

Rodríguez-Teruel, Juan, Oscar Barberà, Astrid Barrio and Fernando Casal Bértoa. 2018. “From stability to change? The evolution of the party system in Spain”, in Marco Lisi, (ed.), Party system change, the European crisis and the state of democracy. London: Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9781315147116-14 |

|

|

Rodríguez-Teruel, Juan and Astrid Barrio. 2016. “Going national: Ciudadanos from Catalonia to Spain”, South European Society and Politics, 21 (4): 587-607. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2015.1119646 |

|

|

Simón, Pablo. 2020a. “The multiple Spanish elections of April and May 2019: the impact of territorial and left-right polarisation”, South European Society and Politics, 25 (3-4): 441-74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2020.1756612 |

|

|

Simón, Pablo. 2020b. “Two-bloc logic, polarisation and coalition government: the November 2019 general election in Spain”, South European Society and Politics, 25 (3-4): 533-63. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2020.1857085 |

|

|

Ştefuriuc, Irina. 2009. “Introduction: government coalitions in multi-level settings—institutional determinants and party strategy”, Regional & Federal Studies, 19 (1): 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560802692199 |

|

|

Strøm, Kaare. 1990. “A behavioral theory of competitive political parties”, American Journal of Political Science, 34 (2): 565-98. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111461 |

|

|

Turnbull-Dugarte, Stuart J. 2019. “Explaining the end of Spanish exceptionalism and electoral support for Vox”, Research & Politics, 6 (2). https://doi.org/10.1177/ 2053168019851680 |

|

|

Twist, Kimberly A. 2019. Partnering with extremists: coalitions between mainstream and far-right parties in Western Europe. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.10117163 |

|

|

Van Spanje, Joost. 2010. “Parties beyond the pale: why some political parties are ostracized by their competitors while others are not”, Comparative European Politics, 8 (3), 354-83. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2009.2 |

|

|