DO PEOPLE WANT MORE PARTICIPATION? TENSIONS AND CONFLICTS IN GOVERNANCE IN TIMES OF SCEPTICISM[1]

¿Quiere la gente participar más? Tensiones y conflictos sobre el gobierno en tiempos de escepticismo

ABSTRACT

When ordinary people are asked how they feel about politics, negative terms enter into the conversation. In this work we analyse how people build their relationship with politics, to explore to what extent political representation is challenged by either participatory trends or by expert-based governance in citizens’ mind. To do this, we use focus groups in Spain, where popular distrust of political institutions rose dramatically in the period 1980‑2012. We analyse the meanings associated with expert-based, representative, and participatory governance models. In this way, the tensions and contradictions in political preferences for one type of institutional design or another are unveiled.

Keywords: Stealth democracy; participation; experts; representation; political distrust.

RESUMEN

Cuando preguntamos a la gente común sobre lo que siente por la política, los términos negativos suelen dominar la conversación. En este trabajo analizamos cómo la gente construye su relación con la política para explorar hasta qué punto la representación política es desafiada tanto por una tendencia participativa como por una tendencia tecnocrática. El trabajo se basa en una investigación con grupos de discusión en España, donde la desconfianza hacia las instituciones políticas ha tenido un incremento extraordinario en los últimos veinte años. El trabajo analiza los significados asociados con una gobernanza dominada por expertos en contra de una dominada por representantes o la participación ciudadana. De esta manera podemos desvelar las tensiones y las contradicciones que la ciudadanía tiene sobre las preferencias por un diseño institucional u otro.

Palabras clave: Democracia furtiva; participación; expertos; representación; desconfianza política.

CONTENTS

- Abstract

- Resumen

- I. INTRODUCTION

- II. BETWEEN PARTICIPATION AND EXPERTS

- III. RESEARCH STRATEGY, METHODS AND SAMPLE

- IV. POLITICS: THE THING THAT DOESN’T WORK

- V. BEYOND REPRESENTATION? THE ROLE OF EXPERTS

- VI. THINKING ABOUT “THE EQUALS”: PARTICIPATION AS AN ALTERNATIVE

- VII. CONCLUSIONS: DEMOCRACY “TOUT COURT”

- Notes

- References

I. INTRODUCTION[up]

When ordinary people are asked how they feel about politics, negative terms such as

dissatisfaction, disenchantment, indifference, apathy, distress or unrest are brought to the conversation and frame any other arguments and complaints. In the

popular imaginary politics is enshrouded in a negative aura. We know that this is

a well established tendency in Western countries, having existed as a classic debate

in Political Science for a long time (Norris, P. (1999). Critical citizens: Global support for democratic government: Global support for democratic

government. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available in:

Democracy needs public support. Against any other way of governing, democracy rests on citizens’ preferences. Thus, disaffection gives rise to a second order question; we are not only concerned with who feels or has this attitude, but to what extent disaffection impacts citizen’s political process preferences. Do people want more participatory governments or do they want more knowledgeable and expert-like politicians? Do they really want to overwhelm representation as a political process?

Increasing participation in politics is an established trend in Western democracies

(Sirianni, C. and Friedland, L. (2001). Civic innovation in America: Community empowerment, public policy, and the movement

for civic renewal. Oakland: University of California Press.Sirianni and Friedland, 2001; Font, J., Della Porta, D. and Sintomer, Y. (eds.) (2014). Participatory democracy in Southern Europe: Causes, characteristics and consequences.

New York: Rowman and Littlefield.Font et al., 2014; Baiocchi, G. and Ganuza, E. (2016). Popular democracy: The paradox of participation. Stanford: Stanford University Press.Baiocchi and Ganuza, 2016). However, against this inclination some researchers have questioned the citizen’s

support for it. More than participation, the citizenry would be inclined towards a

technical and impartial government (Hibbing, J. R. and Theiss-Morse, E. (2002). Stealth democracy: Americans’ beliefs about how Government should work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available in:

The article begins by explaining the viewpoint from which we believe this compatibility makes sense. Secondly, we present our research strategy, based on qualitative methods. This gives us a chance to focus on arguments, so we can follow up on how problems with the current political process are conceived by people and where they would like to innovate. Finally, we examine the arguments in favour of and against participatory or expert based governance in order to shed light on the core question: do people really want to overcome representative political processes?

II. BETWEEN PARTICIPATION AND EXPERTS[up]

Disaffection is not a new phenomenon (Easton, D. (1965). A systems analysis of political life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Easton, 1965; Crozier, M., Huntington, S. P. and Watanuki, J. (1975). The crisis of democracy. New York: New York University Press.Crozier et al., 1975), however nowadays it attracts a lot of attention due to the acknowledgement of the

convergence between a new style of citizenship, more informed and demanding, and an

established representative democracy unable to provide satisfactory answers to this

new social profile (McHugh, D. (2006). Wanting to be heard but not wanting to act? Addressing political

disengagement”. Parliamentary Affairs, 59 (3), 546‑552. Available in:

Some researchers think that the cultural drift of Western societies underlines a political

openness of citizens who demand alternative ways of political engagement and other

institutions (Dalton, R. J. (2004). Democratic challenges, democratic choices: The erosion of political support in advanced

industrial democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available in:

Since Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Hibbing, J. R. and Theiss-Morse, E. (2002). Stealth democracy: Americans’ beliefs about how Government should work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available in:

Besides this confluence, the same factors that explain support for stealth democracy

serve to explain direct democracy support in Finland (Bengtsson, A. and M. Mattila (2009). Direct democracy and its critics: Support for

direct democracy and stealth democracy in Finland”. West European Politics, 32 (5), 1031‑1048. Available in:

One way to understand this puzzle would be to think that people don’t really want

to participate, as Paul Webb (Webb, P. (2013). Who is willing to participate? Dissatisfied democrats, stealth democrats

and populists in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Political Research, 52, 747‑772. Available in:

We propose to deal with the problem of political process preferences from a different perspective. We think that the debate has usually been presented as a zero sum game and it is difficult to obtain good conclusions from it. If people are inclined towards participation, it is expected that they are less likely to accept expert-based government and vice versa. But if recent research shows the compatibility of both trends in survey responses, we suggest that the problem (and the supposed compatibility between critical and stealth hypothesis) could be anchored in a representative framework, rather than in its alternatives. If the expert-based model has positive correlations with participation and representation in Spain (Font, J., Wojcieszak, M. and Navarro, C. (2015). “Participation, representation and expertise: Citizen preferences for political decision-making processes”. Political Studies, 63, 153‑172.Font et al., 2015), perhaps the problem is the lack of expertise in representative political architecture. If people are inclined to participatory processes, could it point to a desire to open up representative mechanisms? So, the first question to answer would be if people reject representation. And then, to what extent they want to articulate participation and expert-based models with representation, or even if they finally pretend to overcome representative architecture. Our hypothesis is that people want to reform current political processes through more open structures and more expertise in decision making processes, rather than overcoming current institutional settings.

We think that the questions quoted above are not easy to answer by applying the same

techniques that have been used to study this puzzle. We already have good explanations

about who is inclined towards expert-based governance or who is involved in participatory

and political activities (Webb, P. (2013). Who is willing to participate? Dissatisfied democrats, stealth democrats

and populists in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Political Research, 52, 747‑772. Available in:

Spain makes for an interesting place to study this issue. As many other South European

countries, two of the most salient features of Spanish political culture have been

distrust in the political institutions and indifference towards politics. Popular

distrust facing political institutions followed a dramatic upward trend in the period

1980‑2012 (Torcal, M. (2014). The decline of political trust in Spain and Portugal: Economic

performance or political responsiveness? American Behavioral Scientist, 58: 1542‑1567. Available in:

The interest of Spain also lies in its singularities regarding political process preferences.

One of the more striking elements of research on this topic has been the simultaneous

support for participation and expert-based governance. In Finland 70 % of people agree

with direct democracy, but they have a similar support of the stealth democracy index

[2]

as Americans (Bengtsson, A. and M. Mattila (2009). Direct democracy and its critics: Support for

direct democracy and stealth democracy in Finland”. West European Politics, 32 (5), 1031‑1048. Available in:

Spain unveils strong political tensions around the ideal decision making models. So, the research can help to illuminate this paradox and we may be able to get closer to the political meanings of participation and experts in a context characterized by strong political disaffection. Is it really true that people are searching for ways of bypassing politicians, but don’t have a desire to become involved in the detail of political decision making?

III. RESEARCH STRATEGY, METHODS AND SAMPLE[up]

We already had data on the preferences for different types of political processes,

so we designed a research strategy based on focus groups. They are useful to interpret

and contextualize previous survey results. Focus groups are a good methodological

strategy to generate in-depth information on a given topic (Morgan, D. L. (1996). Focus Group. Annual Review of Sociology, 22, 129‑152. Available in:

The focus groups were conducted in the first half of 2011. The sample of focus groups

was intended to reflect different political, social and demographic profiles. We wanted

to represent a variety of profiles which were relevant to understanding contrasting

views of political processes. Thus, we selected groups with a high political profile

and groups with a lower political profile, because we already knew that political

experience was a relevant factor evaluating some types of processes (Font, J. and Navarro, C. (2013). Personal experience and the evaluation of participatory

instruments in Spanish cities. Public Administration, 91 (3), 616‑631. Available in: ttps://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2012.02106.x.Font and Navarro, 2013). We also knew that ideology could be a relevant factor (Bengtsson, A. and Christensen, H. S. (2014). Ideals and Actions: Do citizens’ patterns

of political participation correspond to their conception of democracy? Government and Opposition, 51 (2), 234‑260. Available in:

Table 1.

Final sample of focus groups

| Acronym | Features of the participants |

|---|---|

|

FG1

Right wing supporters |

Elda (Alicante), 2011 Militant, sympathizers or voters of right- wing or conservative (Partido Popular) Liberal professions (nurse, doctor, lawyer, public officer) University level education 8 (5 men and 3 women) 25‑40 years old |

|

FG2

Upper-Middle-class professionals |

Zaragoza, 2011 Businessmen and women, liberal professions such as lawyer, architect and economist No political activism University level education 6 (mixed) 30‑55 years old |

|

FG3

University students |

Madrid, 2011 University students Psychology degree and other social sciences No political activism 6 (mixed) |

|

FG4

Retired working class men |

Conil de la Frontera, 2011 Retired workers (ex- workers in agriculture, fisheries and public services) No political activism Medium and low education 6‑10 men Over 65 |

|

FG5

VT Students |

Seville, 2011 Vocational training students Informatics and Computing degrees No political activism 6 (4 men- 2 women) 18‑20 years old |

|

FG6

Left-wing supporters |

Getafe, 2011 Militants, sympathizers or voters of leftist parties (Socialist Party- PSOE or United Left- IU) White-collar workers and liberal professions Further and higher (university) level education 7 (3 women and 4 men) 30‑55 years old |

|

FG7

Social activists |

Córdoba, 2011 Neighbourhood organizations and school parents’ associations Participants all involved in organization’s management 8 (3 women and 5 men) 30‑50 years old |

Source: own elaboration.

The “activist” was understood as a person who belonged to a political organization and had actively participated in it (three groups). Non activist was the person who did not belong or participate in organizations (four groups) which are considered political (parties or social movements). We did not take into consideration whether the participant votes or not. We decided to introduce a sample of conservative and left-wing militants. We also added a group of members of neighbourhood organizations and school parents’ associations, as they are the most common social organization, very institutionalized in most Spanish cities. The two groups of students (VT students and university students) were sought to bring different youth profiles with varying social projections (two different class-positions). They weren’t members of any political organization. In contrast, the group of retired working class men represented a lower educational profile, a middle-low income and an elder generation. In contrast with students and working class men, the group of middle-class professionals was composed of people who were well-off economically and educated to a high level. The purpose was to contrast the different and common axes of discourse by comparing different groups and profiles.

Participants were contacted with the support of a research cooperative, and through

the researchers’ personal and professional contacts. Locations (cities) were chosen

for their accessibility in order to form target groups in that specific area. For

example, the right-wing groups were organized in Alicante, a city where Partido Popular (the right-wing party) used to have an electoral majority. Sessions were held in hotels,

a tennis club, a seniors’ community centre, a research centre, university rooms, etc.

The groups did not have directive moderation, and they were conducted with a script

similar to that used by Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Hibbing, J. R. and Theiss-Morse, E. (2002). Stealth democracy: Americans’ beliefs about how Government should work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available in:

The emergent conversations of the focus groups were transcribed and coded, assisted

by the software Atlas-ti ®. An initial thematic analysis (Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: SAGE.Boyatzis, 1998) was developed. Our unit of analysis was each focus group (which had a number of

ideological conditions, socio-professional status, age and territory). The results

were interpreted in light of the interactions which had taken place within groups.

Focus groups not only provide opinions, but also different dynamics of interaction,

including direct and subtle changes of opinions (Smithson, J. (2000). Using and analyzing focus groups: limitations and possibilities.

International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 3 (2), 103‑11. Available in:

IV. POLITICS: THE THING THAT DOESN’T WORK[up]

All focus groups started with the same question, posed by researchers: “What do you think about the political system in general?” The immediate reaction in all groups was negative: apathy, dissatisfaction, frustration, anger, fatigue, etc. The thing that doesn’t work is related to the communication between the political system and society; people feel that they are not able to put their demands into the political system. Something malfunctions with the political channels. One of the activist participants in Cordoba stresses this point: “the bases of the system are good, but it lacks communicative channels between citizens and politicians”. The problem with democracy has to do with the connections between politics and society, not with democracy itself. The desire to have democratic processes is indisputable; criticism emerges when participants specify what they mean by democratic connections between politics and society, but democracy, as an ideal type, is a common place. Democracy is a basic cultural ground, even if these two job training students, quoted below, do not find any attraction to vote:

P1: This system, personally, doesn’t satisfy me, but I don’t have any particular idea why. Ever since I’ve been able to vote, I’ve never done it, I can’t find any political party fit to represent me. This, I think, is a problem. It shouldn’t happen in a good system.

P2: It’s true, I agree with him. The system doesn’t satisfy me, but it’s not completely wrong, because I see worse things elsewhere.

(FG5, Sevilla).

What we can learn from the focus groups is that people’s political beliefs are framed in a critical and concerned schema. But this frame is not formed by negative irrational emotions and feelings of detachment; it is formed by opinions and debates about the performance of the political system and how institutions are designed. Political dissatisfaction is rooted in a very simple statement: if we live in a democracy, we should have democratic political institutions. This is what leads people to discuss the pros and cons of political process alternatives, the place of experts and participatory mechanisms, but always within the current institutional framework. This reformist spirit evidences a conflicting path between the political imagery of participants and the democratic development of political institutions. For example, participants in the left-wing activist group discussed how institutions were deficient, particularly the party system which was seen as non-democratic, “The party system… I see it as irreplaceable. But, of course, within parties there is no democracy, in any of them. I speak from my experience. I think we are treated as non-adult citizens. Parties fear, at this stage of democracy, open lists, they fear being linked to the territory. They look up to the “priests” who decide the electoral lists. This is my view”. These, or other similar arguments, calling for closer relations and proximity of institutions, appear in all focus groups. They all fit in with the “critical citizen” frame, as people want to open political institutions. But no one seems to reject representative arrangements.

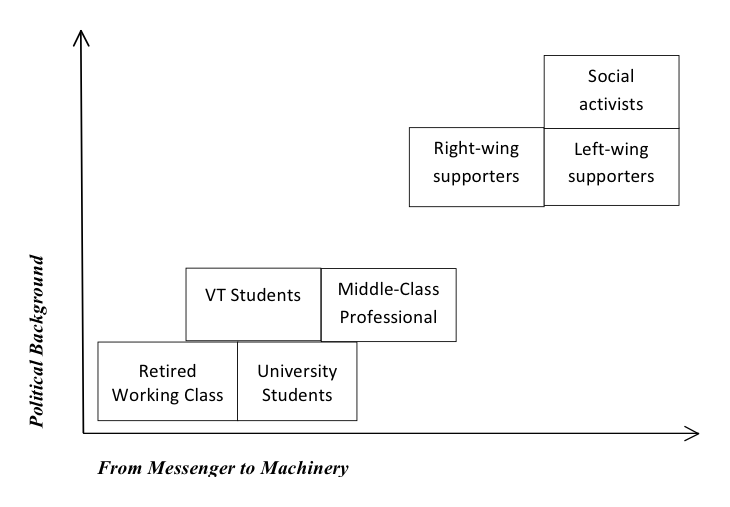

Regarding these connections between the political system and society, we find two contrasting positions in focus groups. On the one hand, in some groups, participants discuss mainly the attributes of the political class, hampering the connection between politics and society. Representatives, for a variety of reasons, do not represent properly. They do not capture and deliver popular demands properly. We call this discourse the “failed messenger problem”, since discourses focus on the (critique of the) attributes and qualities of politicians as elected representatives. On the other hand, in other focus groups, participants focus mainly on the design of institutions and political processes. We call it the “failed machinery problem”. The machinery problem embraces the discourses about the design of political processes, implying the advocacy for other types of political processes.

Participants in our focus groups show mixed arguments; however, some groups privilege the first discourse, and others tend to the second. We can say that those groups formed by participants with higher level of activism tend to discuss the machinery problem, while groups with less political background tend to focus on the messenger problem.

Non-activists were selected taking into account the low political profile of participants (non-militants of parties, social movements or organizations with a strong political profile). For example, university students who were studying psychology were asked not to have any membership in political organizations. When they met and were asked about the political system, they remarked on the flaws of politicians as the main problem. They were worried about the performance of these political actors. They do not act properly; they do not make good decisions. They do not deliver their promises. So they do not represent properly popular demands. The messenger, somehow, does not work.

P1: But then the problem is not the system but people…

P2: I think people are the problem. In my view, you vote and then you can complain

(Webb, P. (2013). Who is willing to participate? Dissatisfied democrats, stealth democrats

and populists in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Political Research, 52, 747‑772. Available in:

P3: You can vote for someone who stands for some things and then he or she does not deliver what they have promised… You say you will do some things and then you don’t. Or you don’t have a fixed policy direction, so it can vary depending on the events ... These changes [in the political direction] also influence people in a way that makes them reject this political system…

P4: Politics have never been well in Spain, they have never been well…

P2: But there have been politicians who had a more marked direction...

P5: Politicians themselves have to adapt... they should be flexible... and I think that ultimately politicians do not adapt to the context, they do not know make good…

(FG3, Madrid).

In contrast, political activists and party supporters privilege the discussion about institutions and their design. They talk about the system machinery. For example, we can identify this pattern in a group of members of neighbourhood and school parents’ associations. These activists criticized the political system in a long conversation on the democratic attributes of current political processes. As can be seen in the following paragraph, some participants criticize the qualities of politicians (the hypothesis of the messenger); but they also deal with the qualities of political processes (the hypothesis of the machinery):

P1: I do not like how it works [the political system]. I had great expectations for

many years. But I think there is a lack of real democracy in many of the institutions.

There is no reception from below [no bottom-up processes], from the level of participation

of people in the streets. Politicians do not listen to the people in the street. There

should be a culture in the political system that, somehow, leads to channel all those

demands… and it does not work. More or less we are on the level of participation in

elections every four years or… vote and, later, maybe the right to complain (Webb, P. (2013). Who is willing to participate? Dissatisfied democrats, stealth democrats

and populists in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Political Research, 52, 747‑772. Available in:

P2: Things are really serious now. Politicians with their official cars… they do not

pay attention to the people. In my view, this will end very badly… I think you have

to live with the people, fighting for the people. People have chosen them, and they

should be ready and willing to work for the people, not people working for politicians

(Webb, P. (2013). Who is willing to participate? Dissatisfied democrats, stealth democrats

and populists in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Political Research, 52, 747‑772. Available in:

(FG7, Córdoba).

There is something wrong in the machine. For these participants, it is not only a matter of the attributes of politicians. They suggest that there is a problem of “communication channels” and there can be alternatives in terms of political processes. They talk about participatory processes. The high political background of these participants, their engagement with local politics trough civic organizations, and even their knowledge of local participatory institutions make them prolific at criticizing the design of political processes. They know the machinery of local politics and they are familiar with political institutions. They discuss mainly alternative processes to fix “the machine”. When they do it, they never think about an alternative to the representative system, but in reforming it from a participatory framework.

V. BEYOND REPRESENTATION? THE ROLE OF EXPERTS[up]

The idea that dissatisfaction with democracy can go beyond representation is usually

portrayed as lack of knowledge and “frustration with the obscure complexities of the

political processes” (Webb, P. (2013). Who is willing to participate? Dissatisfied democrats, stealth democrats

and populists in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Political Research, 52, 747‑772. Available in:

People are really upset with politicians and political parties, but they never imagine

a political design without them, as this left-wing participant says: “The political

party system is irreplaceable”. The problem is what political theory calls “cartel

party” (Katz, R. S. and Mair, P. (1995). Changing models of party organization and party democracy:

The emergence of the cartel party. Party Politics 1 (1), 5‑28. Available in:

Most people’s criticism against politicians and political parties stem from this “cartel”

grammar. Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Hibbing, J. R. and Theiss-Morse, E. (2002). Stealth democracy: Americans’ beliefs about how Government should work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available in:

However the debate here (the complexity of politics) revolves around the expert issue

as if they could offer a solution. Stealth hypothesis supporters were right to stress

the importance of the issue, because experts, as an ideal meritocracy body in citizens’

political imaginary, hold for all the “good” attributes necessary to effectively rule

for the community: “They can make decisions efficiently, objectively and without disagreement”

(Hibbing, J. R. and Theiss-Morse, E. (2002). Stealth democracy: Americans’ beliefs about how Government should work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available in:

Hence, participants frequently conceive the ideal politician through expert qualities. As one member of the right-wing activists explained: “The important thing would be that the politician is the expert, it’s what we’ve talked about, excellence and qualification. If one is an expert in economics, I do not want him to be minister of education. I want him to be the finance minister.” If technical knowledge is something seen as necessary to perform political functions, participants think that meritocracy, and the principle of distinction linked to it, should therefore be part of the political profile. As a member of the left activist group argued, “I think that politics is one of the professions which require the most expertise in all aspects, that’s to say that in politics only the wisest people should govern”. Expertise seems to be a political guarantee for citizens in a complex world, but if politicians fail or they are not good enough, should experts rule? Should they replace the parties and politicians as the stealth hypothesis suggest? In the groups, this issue always gave rise to a sharp debate around the role that technical experts should play in government.

The discussion was always guided by a confrontation between a “necessary technical knowledge to rule” and “people’s right to be elected for ruling”. The tension was strong, but discussions gave priority to the latter, even if most agreed that merit is central in a political career, as this exchange in the right-wing group shows:

P1: There must be representatives, but well-qualified representatives. As for myself, I am ashamed to see the president of my country get nervous when someone speaks English to him.

P2: But Ivan, why do we demand qualification from our politicians and not from the citizens?

P1: What I want is that those who govern us have a minimum guarantee, because if the minister of economy knows nothing about economics, chaos sets in. Okay, representatives yes, but qualified.

(FG1, Alicante).

We can observe this pattern in all groups. At first politics is associated with the knowledge of experts, because of world complexities. But as the debate advances, participants start to think around the meaning of democracy, that is, the right of each to rule regardless of their origin. At the end, from the left-wing participants (“experts can help, advise decision making process”) to upper middle class (“Politics takes more than professionalism. You need to have a political concept and experts don’t have it”); or university students (“You cannot make decisions about people if you haven’t been chosen to do so. You can give information as an expert”), the problem is that politics often requires political and not technical decisions, so political decisions should be made by someone elected. Far from rejecting politics, in the conversation the technical issue reminds participants of the importance of the political grammar. A good politician would be someone who knows how to do their job well. Experts aren’t ultimately seen as an alternative, but “expertise” is a fundamental part of a good government. Dealing with this issue is a cornerstone in citizens’ political imagination.

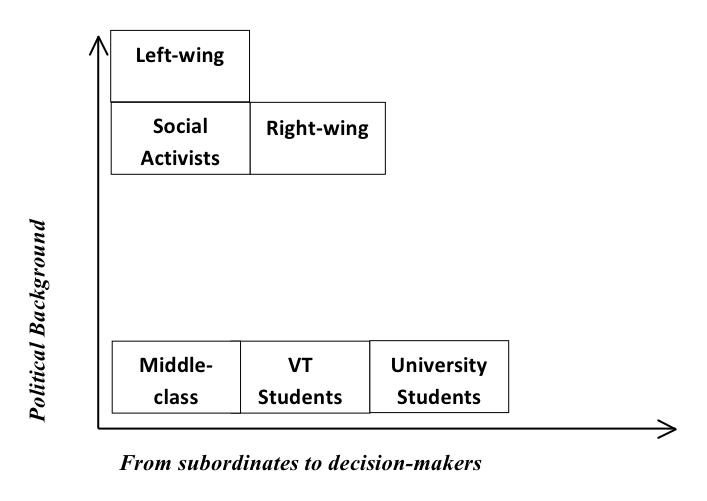

We don’t find big differences across groups around this issue. However in highly politicized groups, participants made a clear distinction: experts are subordinated to politicians. Experts are considered “advisers” (“asesores”), “technical staff” or public servants. Their role is to advise politicians and support them so that public policies are of a high quality. This vision is shared by social activists, left and right wingers. Participants in groups of non-activists show a wider variety of positions. There are those participants who do not develop the question further (working-class pensioners), those that show internal debate and contradiction (training and university students), and those who share the activists’ understanding (upper middle-class professionals). Some participants in non-activist groups rely on the discourse that experts should have a stronger voice in political processes and decision-making. Other participants defend the subordination relationship mentioned above. They show a plurality of discourses which is not present in highly politicized groups, although ultimately they are not confident that a more prominent role of experts in government would make a positive difference.

VI. THINKING ABOUT “THE EQUALS”: PARTICIPATION AS AN ALTERNATIVE[up]

We can say that we live in a participatory age. “Political participation today occupies an exceptional position as a privileged prescription for solving difficult problems and remedying the inherent flaws of democracy” (Baiocchi, G. and Ganuza, E. (2016). Popular democracy: The paradox of participation. Stanford: Stanford University Press.Baiocchi and Ganuza, 2016: 3). Within this context scholars have wondered if participation is a real alternative in the citizens imaginary as supporters of critical citizens hypothesis have suggested. When participants are asked to think about the feasibility of a participatory model of government they doubt strongly. No one questions the normative background linked to democracy, which is based on the idea of people ruling, but the feasibility of applying the ideal. Here the problems with politicians are taken to society as a whole. Society will then become the cornerstone of the current political crisis.

People have an underlying view that society is partly responsible for the degradation of the political system. The argument is quite consequential, because if politicians are corrupt and they rule guided by particular interests, it is because no one pays attention, it is because of society. In public discourse, the ultimate blaming of the entire society prevails: “it is the people who are ill and corrupt”, a participant in the retired people’s group said, getting the approval of the rest. This socialization of the political responsibility balances the criticism towards the political class. One participant in the upper middle class group made the point that, “In any political system, even in those that are not very extreme, in theoretical terms, all regimes have very good things. What happens is that it’s people who put them into practice, right? That’s the problem in the end.” In the group of neighbourhood activists, ideologically contrary to the former group, someone arrived at the same conclusion, “I still think we’re not disenchanted by politics, we are disenchanted by some politicians, those who have damaged the overall image of something as magnificent as politics.” The negative image of the society itself makes it really difficult to imagine any participatory alternatives to the current political crisis; these will always face individual narrow-mindedness, passions and interests.

The arguments among participants are embedded in the same questions which guide the criticism of politicians. Ordinary people, in the face of political participation, would be unable to work together for the common good and to reach political agreements at the expense of particularistic interests. Many of the problems which targeted the political elite are dumped on society as a whole. If world complexities render expertise an important issue in politics, the same underlines participation. The point is the lack of education, information and civic competence which Spanish people supposedly display in the political arena. For the group of retired working-class men, it seems clear that “People are not ready to make decisions, because there is no education and culture. And that’s what happens to people.” It is not just a matter of old generations. For younger students (VT students), the perception is similar, “as people lack knowledge, they [politicians] conceal relevant issues to us”. Even in the group of neighbourhood activists, who are the most politically confident and demand active participatory policies at municipal level, participants share the same argument: “Yes, the level of citizen competence, that is still very low. We are talking of civic competence...”

It is not only an abstract idea about people; all participants discussed widely the reasons behind this framing with pragmatic examples. All focus groups put in motion a metaphor of direct democracy in assemblies making reference to what we have called the property owners’ council syndrome (“el síndrome de la comunidad de vecinos”). Property owners’ councils are a typical Spanish form of managing horizontal property. The building normally has a meeting a couple of times per year to decide the needs and problems of the community and, specifically, the shared facilities. These councils are mandatory by law. For a member of the upper middle class group, “If you have the opportunity to go to a meeting of a neighbours’ community … People go there with two lawyers! And they just insult each other: it’s a frenzied show. That’s what would happen in this country if we could all have a say in politics.” Likewise, in the left activist group, a participant references the property owners’ council syndrome, “Look, here there’s just a few of us and there are two who talk a lot. I’d love you to see a meeting of my neighbours’ community, it’s unbelievable! Imagine a hundred people deciding. I think we need representatives, there must be some sort of delegation.” The argument is that people’s quarrelsome, egoistic and low civic competence somehow renders society ill-equipped to have a central role in politics.

If participation is not a real alternative to the current political system, participatory

processes are not rejected at all; at least, the idea of having a voice in a representative

framework. Even if politicians were good enough, even if politics should be ruled

by politicians and experts should advise them, people in democracy should also have

a voice in ruling. Here the literature confuses taking part in the daily task of ruling

(Webb, P. (2013). Who is willing to participate? Dissatisfied democrats, stealth democrats

and populists in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Political Research, 52, 747‑772. Available in:

The differences among groups have to do with the procedures and tools discussed. It

may be the difference already pointed out by Webb (Webb, P. (2013). Who is willing to participate? Dissatisfied democrats, stealth democrats

and populists in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Political Research, 52, 747‑772. Available in:

There is a general view that important decisions need some involvement from society, from right to left-wing militants and across socioeconomic positions. In the group of right-wing voters a vibrant debate took place, “Are we in a real democracy or a democracy where we vote ... simply choosing some representatives who govern us for four years following their ideals? Ideally, I would make it a condition that plebiscites establish the laws. For me, this would be the ideal government”. A peer in the group replied that “in big issues, when reforming important laws… they should consult the people”. For one of the participants in the group of professional training students it was clear, “Relevant decisions? By urban referendum”, and a participant in the retirees’ group proposed exactly the same, “Why don’t you ask the people? By referendums or in meetings…” Thus, the criticism against politicians begins to make sense through an open reform of political parties as collective institutions which should be linked to society. The idea of communication and participation, without taking the power, leads citizens to envisage political reforms within the parties: open lists, changes in the electoral system, the bonding of representatives to the territory and their population, the limitation of terms, referenda on key issues, internal democracy in political parties, etc. People demonstrate a desire for greater popular control over political processes and for embedded types of political representation, but no one wants to overwhelm them.

If, at the onset, the participation in our focus groups thought about expertise as something compatible with representative institutions, now we can see that for them participation only makes sense as part of a representative framework. No one searches alternatives beyond representation. This unveils the conundrum that people are faced with when dealing with their preferences about political processes.

VII. CONCLUSIONS: DEMOCRACY “TOUT COURT”[up]

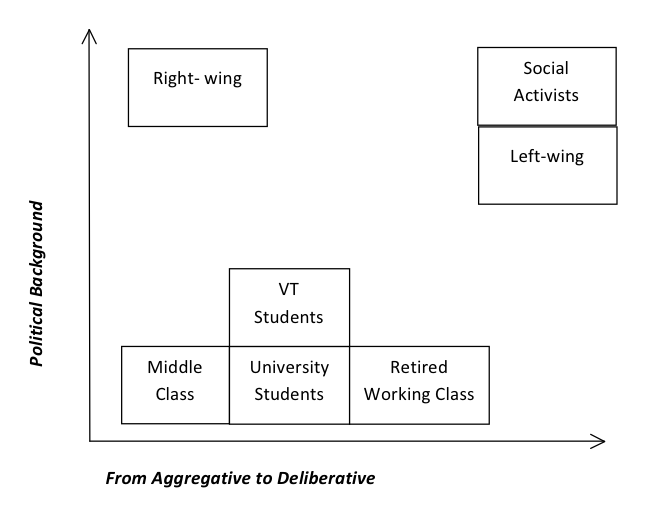

According to our focus groups, we can understand the frustration with politics. Politicians

are bad, experts cannot replace them because politics should be performed by elected

representatives, and citizens are incompetent to rule and to elect good politicians.

This political vicious circle feeds the citizen’s political imagination. The problem of the political system is,

finally, a cultural issue embodied in a crisis of values and civic competence. This

reference appears clearly in leftist groups, which include people engaged in associative

movements, who support the participatory experiences from an educative perspective.

This is because they are more inclined to deliberative devices rather than aggregative

ones, such as referenda (García-Espín, P., Ganuza, E. and de Marco, S. (2017). ¿Asambleas, referéndum o consultas?

Representaciones sociales de la participación ciudadana”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas (forthcoming in 2017). Available in:

The debate about political processes in our focus groups unveils that citizens’ direct

participation is not perceived as a clear alternative. People do not want to get involved

in the detail of political decision making, as suggested by Webb (Webb, P. (2013). Who is willing to participate? Dissatisfied democrats, stealth democrats

and populists in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Political Research, 52, 747‑772. Available in:

The idea of experts ruling, or anything which aims to overwhelm representative democracy,

is finally rejected. Because politics matters and is complex, citizens think that

experts cannot be left out, but neither can citizens. The debate has to take place

in political institutions (from political parties to parliaments), but it shouldn’t

forget the state/society links. Presented with more than one model of involvement

in everyday politics, participants support the idea of citizen debate on key political

issues. As much of the research on political process preferences shows, the idea of

referenda about important issues is widely shared, while specific participatory procedures

such as participatory budgeting, participatory councils, etc., are common mainly to

left-wing groups (García-Espín, P., Ganuza, E. and de Marco, S. (2017). ¿Asambleas, referéndum o consultas?

Representaciones sociales de la participación ciudadana”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas (forthcoming in 2017). Available in:

We think the focus groups illustrate an important point in the debate about political process preferences. Politicians, experts and people do not live in separate dimensions. As Font et al. (Font, J., Wojcieszak, M. and Navarro, C. (2015). “Participation, representation and expertise: Citizen preferences for political decision-making processes”. Political Studies, 63, 153‑172.2015) suggested before, the three ideal political dimensions are not antagonistic and are intertwined in the minds of citizens. The compatibility between critical and stealth attitudes in people’s minds highlights 1) the importance of expertise in politics and 2) the will to have more open political systems. Future research has important questions to ask in order to better understand how the three dimensions (expertise, participation and representation) are articulated and to make sense of the divergences between countries. We cannot forget the Spanish political disaffection context. Perhaps in other contexts we may expect different results.

Notes[up]

| [1] |

Esta investigación se ha realizado en el marco del proyecto de investigación «Stealth democracy: Between participation and professionalization», financiado por el Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (CSO2012‑38942). |

| [2] |

The stealth democracy index set up by Hibbing and Theiss-Morse is based on four different items: 1) officials should stop talking and they should start to act; 2) compromise means selling out own principles; 3) government should be run by experts or 4) businessmen |

References[up]

|

Baiocchi, G. and Ganuza, E. (2016). Popular democracy: The paradox of participation. Stanford: Stanford University Press. |

|

|

Bengtsson, A. and M. Mattila (2009). Direct democracy and its critics: Support for direct democracy and stealth democracy in Finland”. West European Politics, 32 (5), 1031‑1048. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380903065256. |

|

|

Bengtsson, A. and Christensen, H. S. (2014). Ideals and Actions: Do citizens’ patterns of political participation correspond to their conception of democracy? Government and Opposition, 51 (2), 234‑260. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2014.29. |

|

|

Bonet, E., Martin, I. and Montero, J. R. (2006). Las actitudes políticas de los españoles. In J. Font, J. R. Montero and M. Torcal (eds.). Ciudadanos, asociaciones y participación en España (pp. 105‑132). Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. |

|

|

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: SAGE. |

|

|

Bryman, A. (2001). Social research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe. (2001). Participation of citizens in local public life. Recommendation 2001‑19. |

|

|

Crozier, M., Huntington, S. P. and Watanuki, J. (1975). The crisis of democracy. New York: New York University Press. |

|

|

Dalton, R. J. (2004). Democratic challenges, democratic choices: The erosion of political support in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199268436.001.0001. |

|

|

Easton, D. (1965). A systems analysis of political life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. |

|

|

Font, J., Navarro, C., Wojcieszak, M. and Alarcón, P. (2012). ¿“Democracia sigilosa” en España?: preferencias de la ciudadanía española sobre las formas de decisión política y sus factores explicativos. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. |

|

|

Font, J. and Navarro, C. (2013). Personal experience and the evaluation of participatory instruments in Spanish cities. Public Administration, 91 (3), 616‑631. Available in: ttps://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2012.02106.x. |

|

|

Font, J., Della Porta, D. and Sintomer, Y. (eds.) (2014). Participatory democracy in Southern Europe: Causes, characteristics and consequences. New York: Rowman and Littlefield. |

|

|

Font, J., Wojcieszak, M. and Navarro, C. (2015). “Participation, representation and expertise: Citizen preferences for political decision-making processes”. Political Studies, 63, 153‑172. |

|

|

Gamson, W. and Sifry, M. (2013). “The Occupy Movement”. The Sociological Quarterly, 54 (1), 159‑230. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1111/tsq.12026. |

|

|

García-Espín, P., Ganuza, E. and de Marco, S. (2017). ¿Asambleas, referéndum o consultas? Representaciones sociales de la participación ciudadana”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas (forthcoming in 2017). Available in: https://doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.157.45. |

|

|

Hibbing, J. R. and Theiss-Morse, E. (2002). Stealth democracy: Americans’ beliefs about how Government should work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511613722. |

|

|

Hydén, L. C. and Bülow, P. H. (2003). Who’s talking: drawing conclusions from focus groups-some methodological considerations. International Journal Social Research Methodology, 6 (4), 305‑321. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570210124865. |

|

|

Katz, R. S. and Mair, P. (1995). Changing models of party organization and party democracy: The emergence of the cartel party. Party Politics 1 (1), 5‑28. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068895001001001. |

|

|

Kitzinger, J. (1995). Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ: British medical journal, 311 (7000), 299‑302. |

|

|

Laclau, E. (2007). On Populist Reason. London: Verso. |

|

|

Lasch, C. (1995). The revolt of the elites. New York: Norton Company. |

|

|

McHugh, D. (2006). Wanting to be heard but not wanting to act? Addressing political disengagement”. Parliamentary Affairs, 59 (3), 546‑552. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsl027. |

|

|

Morgan, D. L. (1996). Focus Group. Annual Review of Sociology, 22, 129‑152. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.129. |

|

|

Mota, F. (2006). ¿Hacia la democracia participativa en España? Coincidencias y discrepancias entre ciudadanos y representantes políticos. En A. Martínez (ed.). Representación y calidad de la democracia en España. Madrid: Tecnos. |

|

|

Munday, J. (2006). Identity in focus: The use of focus groups to study the construction of collective identity”. Sociology, 40 (1): 89‑105. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038506058436. |

|

|

Neblo, M. A., Esterling, K., Kennedy, R., Lazer, D. and Sokhey, A. (2010). Who wants to deliberate and why? American Political Science Review, 104 (3), 566‑583. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055410000298. |

|

|

Norris, P. (1999). Critical citizens: Global support for democratic government: Global support for democratic government. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1093/0198295685.001.0001. |

|

|

Norris, P. (2009). Public disaffection and electoral reform: Pressure from below? Paper prepared for ECPR Joint Sessions of Workshops, Lisbon, 14‑19 April 2009. |

|

|

Norris, P., Walgrave, S. and Van Aelst, P. (2006). Does protest signify disaffection? Demonstrators in a postindustrial democracy. In M. Torcal and J. R. Montero (eds.). Political dissatisfaction in contemporary democracies (pp. 279‑307). London and New York: Routledge. |

|

|

Pharr, S. and Putnam, R. (2000). Disaffected democracies. Princeton: Princeton University Press. |

|

|

Sirianni, C. and Friedland, L. (2001). Civic innovation in America: Community empowerment, public policy, and the movement for civic renewal. Oakland: University of California Press. |

|

|

Smithson, J. (2000). Using and analyzing focus groups: limitations and possibilities. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 3 (2), 103‑11. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1080/136455700405172. |

|

|

Stoker, G. (2006). Why politics matters: Making democracy work. London: Palgrave Macmillan. |

|

|

Tejerina, B., Perugorría, I., Benski, T. and Langman, L. (2013). From indignation to occupation: A new wave of global mobilization. Current Sociology, 61, 377‑392. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392113479738. |

|

|

Torcal, M. (2014). The decline of political trust in Spain and Portugal: Economic performance or political responsiveness? American Behavioral Scientist, 58: 1542‑1567. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764214534662. |

|

|

Torcal, M. and Montero, J. R. (eds.) (2006). Political disaffection in contemporary democracies: Social capital, institutions, and politics. London: Routledge. |

|

|

Webb, P. (2013). Who is willing to participate? Dissatisfied democrats, stealth democrats and populists in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Political Research, 52, 747‑772. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12021. |