Analysis of the teaching role in a gamification proposal in the teacher’s master’s degree

Análisis del rol docente en una propuesta de gamificación en el máster de profesorado

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2024-405-635

Carmen Navarro-Mateos

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0757-7975

Universidad de Granada

Isaac José Pérez-López

https://orcid.org/000-0002-4156-7762

Universidad de Granada

Carmen Trigueros Cervantes

https://orcid.org/000-0001-7870-1411

Universidad de Granada

Abstract

Introduction: learning environments have suffered enormous changes in the last few years, as a consequence of social transformations and the students’ new demands. Furthermore, motivation in higher levels of education is related with a better academic performance, with the teaching staff’s role as a key aspect to have an impact on it. In this context, gamification is especially relevant, since it takes advantage of the attractiveness and significance of games and videogames to boost the implication and the learning experience. On the other hand, TV programs are a format that generates a great interest in university students. Therefore, the objective of this article is to analyse the teaching staffs’ role in a gamification proposal inspired by the TV program Masterchef, based on the narratives of its participants, with the intention of knowing its incidence and the aspects highlighted by them. Methodology: the participants were 29 students (4 female, 25 male) from the MA in Teaching from the University of Granada. A qualitative methodology was employed, and a phenomenological study was conducted. Through an open question approach, and using Google Drive, the students shared, anonymously and voluntarily, their emotions, the things they learned and both the negative and positive aspects they lived throughout the experience. The analysis was done using the software Nvivo. Results: the three characteristics that the students highlighted about the professor, and that according to their narratives, had the most impact on the degree in which they took advantage of the proposal, were: the levels of exigence (which made them give the better of themselves), the feedback (which favoured the learning process and the feeling of making progress) and the care for details (which contributed in the immersion of the participants and the credibility of the proposal). Conclusions: seeing the obtained results, the teacher/professor is a key differentiator element in these types of approaches, resulting in a higher degree of implication from the students and a higher degree of satisfaction with the proposal.

Keywords: teaching role, gamification, learning, university, students.

Resumen

Introducción: los entornos de aprendizaje han sufrido enormes cambios en los últimos años, como consecuencia de las transformaciones sociales y las nuevas demandas del alumnado. Además, la motivación en educación superior se relaciona con un mejor rendimiento académico, siendo el rol del docente un aspecto clave para incidir en la misma. En este contexto, adquiere especial relevancia la gamificación, pues aprovecha el atractivo y significatividad de los juegos y videojuegos para favorecer la implicación y el aprendizaje. Por otro lado, los programas de televisión son un formato que genera un gran interés en los estudiantes universitarios. Por tanto, el objetivo del presente artículo es analizar el rol del docente en una propuesta de gamificación basada en el concurso Masterchef, a partir de las narrativas de sus participantes, con la intención de conocer su incidencia y los aspectos más destacados por ellos. Metodología: los participantes fueron 29 estudiantes (4 chicas y 25 chicos) del máster de profesorado de la Universidad de Granada. Se ha utilizado la metodología cualitativa, llevando a cabo un estudio fenomenológico. A través de una pregunta abierta, mediante Google Drive, los estudiantes compartieron, de manera anónima y voluntaria, sus emociones, aprendizajes y aspectos más y menos positivos a lo largo de la experiencia. El análisis se realizó con el software Nvivo. Resultados: las tres características que el alumnado más destacó del docente y que, según sus narrativas, más incidieron en el grado de aprovechamiento de la propuesta, fueron: la exigencia (que les hizo sacar su mejor versión), el feedback (que favoreció su aprendizaje y sensación de progreso) y el cuidado de los detalles (que incidió en la inmersión de los participantes y la credibilidad de la propuesta). Conclusiones: a tenor de los resultados obtenidos, el docente es un elemento diferenciador en este tipo de planteamientos, propiciando un mayor grado de implicación del alumnado y de satisfacción con la propuesta.

Palabras clave: rol docente, gamificación, aprendizaje, universidad, alumnado.

Introduction

The pedagogical methods that involve students and make them work actively in learning tasks and through reflective processes, represent in recent years a new model of teaching at different stages, including the university level (Pires, 2021). In this context, different digital resources are combined with in-person teaching, achieving students’ proactive behaviors in training processes (Andrade and Brookhart, 2020; Van Laer and Elen, 2017). With the rapid development of educational information technologies, traditional teaching environments have undergone enormous changes, also requiring a transformation of the teaching role. The knowledge transfer function of the teacher has been replaced by a role more related to the development, guidance and facilitation of learning (Liu, 2018). However, assuming the role of information facilitator requires adaptation and flexibility on the part of the teacher, understanding learning as a process (Hernández et al., 2018; Reeve, 2006).

On the other hand, the concept of leadership typical of the area of marketing and business, can be transferred to the field of education, where the teacher must be aware of the importance of creating an environment conducive to learning and motivation (Peña and Wandosell, 2015). In fact, motivation in higher education is directly linked to academic performance and, ultimately, to educational success (Okada, 2023; Robbins et al., 2004). Similarly, the relationship between the teacher and the student is another key predictor of academic performance (Frenzel et al., 2009; Yoon, 2002). Knowing what students expect from teachers is essential when playing the teaching role, and improving teacher-student relations (Poulou, 2014; Wubbels, 2005).

If we analyze the profile of the ideal teacher based on the perceptions of students (Marín et al., 2011), students related to the field of social sciences highlight three aspects: teachers’ skills to teach (fluency in explaining, good communicative skills, etc.), the relationship with students (understanding and receptive person, etc.) and their social skills (close person, not authoritarian, etc.). Focusing on the teachers themselves, they highlight the importance of personal skills to develop their profession, such as pedagogical love, motivation, enthusiasm, creativity or self-criticism (Alonso-Sainz, 2021). These were followed by didactic-pedagogical skills, such as reflection on teaching practice, innovation or the use of teaching strategies that include active methodologies.

Therefore, the technical vision of education should be put aside in higher education and bet on an approach in which the personal growth of both student and teacher takes precedence, achieving significant learnings related to the objectives set by the teacher (Orón and Blasco, 2018). Different authors highlight the key role that motivation, through the role of the teacher, plays in the teaching and learning processes, since the relationships that are established with the students and the methodology selected will influence the interest and development of the students’ skills (González-Castro et al., 2021; Rodríguez-Pérez, 2012; Valenzuela et al., 2015).

Audiovisual influence

In the current audiovisual panorama, television series are the ones that achieve the greatest impact on the population, with a growing trend in the supply of titles and possibilities in recent years in the different streaming platforms (Albornoz and García, 2022). Young people today prefer to watch series and films on these platforms (Cortés-Quesada et al., 2022; Navarro-Robles and Vázquez-Barrio, 2020), although for the viewing of contests or reality shows they continue betting on traditional television (Navarro-Robles and Vázquez-Barrio, 2020). In addition, this generation has a tendency to connect audiovisual content and social networks, as they share their opinions through the Internet, which further expands the possibilities (Guerrero-Pérez, 2018).

Therefore, as Arufe-Giráldez (2019) says, the current media boom is a great opportunity for teachers, since college students are frequent consumers of television programs. This significance can be used to adapt successful formats to the educational context, generating a greater attraction in the way a subject is presented and carried out.

Some examples are the works of González and Pujolà (2021) and Pérez-López and Navarro-Mateos (2023a) developed in Spain. The former took advantage of the Peking Express television contest, including missions as a characteristic element of the programme for foreign language teaching and game-based learning as a methodology. Thanks to this, they managed to influence the motivation and learning of students, highlighting the potential of play in the educational context. The work of Pérez-López and Navarro-Mateos (2023a), called “Este profe me suena”, was carried out in the Master’s degree in teaching and was inspired by the Spanish well-known program “Tu cara me suena”. It included the main roles that appear in the contest (host, jury and contestants), and elements as the push button, combined with learning based on challenges. Students showed enormous satisfaction for the learning acquired through an approach of these characteristics, given its attractiveness and significance. In addition, in the international scientific literature, we find more proposals that, although they do not recreate the sensations and emotions of television programs as such, they use instead their potential to work with content from different subjects and reflect on current social issues (Black, 2001; Huilin and Hyangkeun, 2020; Klein, 2011; Wang, 2012).

Gamification

In close relation to the previous section, and in regards with the importance of increasing motivation of students to favor their learning, in the last decade there has been a boom of gamification in the educational context (Dicheva et al., 2015; Subhash and Cudney, 2018). One of its main objectives, precisely, is to influence students’ motivation in the teaching and learning process through different mechanics and elements of games and video games and, thus, achieve greater involvement in the learning process (Kapp, 2012). In fact, the different theories that support their inclusion in the educational context are based on a positive relationship between gamification and learning outcomes (Landers, 2014; Sailer and Homner, 2020).

In many cases, the concept of gamification has been mistakenly associated with the use of three very characteristic elements of video games: points, badges and leaderboards (PBL). In the educational field, gamification cannot be limited to the extrinsic component, since it is intended to achieve transcendent objectives that go beyond the exclusive use of rewards (Kapp, 2012; Pérez-López and Navarro-Mateos, 2022a; Zichermann and Cunningham, 2011). That is why other aspects should be included such as, for example, a narrative, challenges and missions, or the actions and emotions characteristic of the thematic universe selected to make the most of the full potential of gamification in the classroom (Marczewski, 2018; Pérez-López and Navarro-Mateos, 2023b).

Gamification can be carried out under a formative approach or a experiential one, but this does not mean that in any of the approaches is dispensed with what characterizes the other (Pérez-López and Navarro-Mateos, 2022b). In postgraduate education, the emphasis should undoubtedly be placed more on the formative approach, giving students the opportunity to consolidate and build on the learning acquired previously in their undergraduate studies. Further, we talk about a profile of students with a higher level of competence, and it is highly recommended that they become aware that they are the main responsible for achieving quality training. As the authors point out, the approach of a television format (or talent show), with a more sequenced approach and closed structure and design beforehand, can be a good option for postgraduate students (Pérez-López and Navarro-Mateos, 2022b). In fact, this circumstance is not incompatible with uncertainty, curiosity and surprise, key aspects in the training processes to achieve significant learning (Domínguez-Márquez, 2019; Mora, 2017; Oudeyer et al., 2016). In addition, the performance of the participants will determine "their continuity in the (television) program", testing the commitment to their training and the development of core competencies for their future work performance.

Contextualization

The present proposal was developed in a course of the specific module Learning and Teaching of Physical Education, of the University Master in Teaching in Compulsory Secondary Education and Baccalaureate, Vocational Training and Language Teaching (in the specialty of PE -Physical Education-) of the University of Granada (Spain). It involved 29 students (4 girls and 25 boys), and had a teaching load of 12 credits. The main objectives or learning outcomes of this course are:

- Knowing and analyzing the curricular elements, establishing correspondences between them and evaluating the suitability of these.

- To know and use the basic concepts of the didactic of PE to make a global analysis of the teaching and learning processes.

- Plan a school educational program in PE from a critical perspective, assessing its suitability and making modifications consistent with the aims of education.

- To acquire teaching skills for the future development of their professional work.

Proposal description

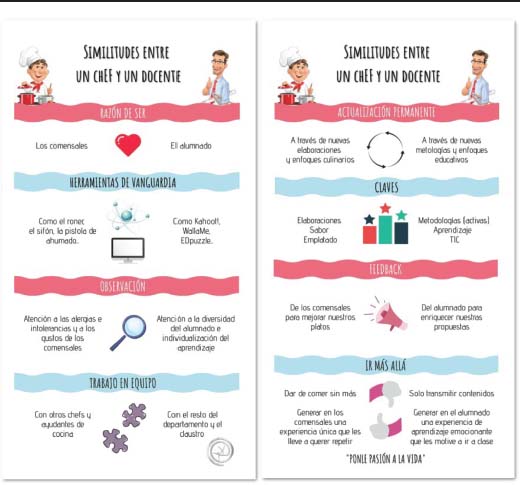

A proposal was made with gamification and active methodologies as a reference, so that the students had the leading role. The popular television contest called Masterchef was used, given the great impact of this show, and adapted to the educational field. In fact, after a first analysis of its main elements and structure, it was possible to see the enormous potential it had in this regard, as shown in Figure I.

FIGURE I. Similarities between the world of culinary and teaching

Source: Compiled by author.

During the whole experience, students were made to feel like the contestants of the program, recreating the emotions and feelings of the participants in each challenge they had to face (emotions management, time pressure, teamwork or creative approach), and transferring all of it to the future reality of a PE teacher.

The teacher (chEF -EF is from Educacion Fisica in Spanish, Physical Education in English-) was in charge of presenting the different contest tests, as in the original program, and presenting weekly the “ingredients” (formative contents) with which the contestants had to elaborate the “dishes” (challenges) that must meet different standards characteristic of the culinary field: “flavor” (degree of compliance with the objectives set), “logic of the dish” (coherence between the contents presented) and “plate up” (format in which it was presented).

The three classes a week (Monday, Wednesday and Thursday) were used to recreate the structure of the original program, maintaining the three tests that characterize Masterchef:

- Individual test (on Mondays): the contestants had different “ingredients” to use in their “dish”, either in some concrete way or in a free way. In this test the most outstanding candidates were chosen, becoming the captains of the team event.

- Team test (on Wednesdays): the captains chose the members of their teams and the “menu” (a combination of different challenges) they preferred to perform. The challenge was to work as a team in an organized way to get all the “dishes” out in time. Teams that got the worst feedback faced the elimination test (happening on Thursdays).

- Proof of “elimination” (on Thursdays): the contestants who stood out the day before had to perform individually the challenge that the jury had prepared for that day. Those responsible for the “dishes” that did not meet the established criteria were no longer eligible to win the title of MasterchEF Granada (unless they managed to stand out in the retake of the penultimate week of the contest). However, all of them continued to participate in the tests and challenges of each week, acquiring the same learning as the rest of the peers.

One of the key aspects to making the experience more immersive and credible was the care of small details and language. In this sense, the characteristic objects of the program (figure II) were used, such as the logo, the mysterious box, the clock that marks the cooking time or the immunity pin, as well as the white aprons of the contestants (and black for the elimination test).

FIGURE II. Example of elements included to increase immersion and credibility

Source: Compiled by author.

Each week the challenges were built around one or several “ingredients”, as detailed below:

- Week 1. Presentation and class climate.

- Week 2. Educational legislation and planning in PE.

- Week 3. Value of PE and profile of a good teacher.

- Week 4. Active methodologies and importance of communication skills.

- Weeks 5 and 6. Teaching intervention through practical sessions in PE.

- Week 7. Game-based learning and play point.

- Week 8. Evaluation, escape room and gamification.

- Week 9. Creative cooking (developing creativity in education), serious games and retake test.

- Week 10. Semifinal and final.

Method

The work has been framed within the interpretive paradigm (Denzin, 2010; Denzin and Lincoln, 2012; Silverman, 2001). A qualitative methodology has been used, and a phenomenological study was performed to understand the experience lived in all its complexity (Fuster, 2019; Van Manen, 2017). We aimed to have a vision of the feelings, perceptions and experiences of the participants involved in the project. The analysis aims to know and understand the perceptions that students have of the teaching role in a proposal of gamification. Therefore, the objectives of this work are:

- To describe the structure and main elements of a gamification project developed in the Master of teaching, and inspired by the Masterchef cooking television program.

- To analyze and interpret the testimonies that students made throughout the proposal with respect to the performance of the teacher, identifying the aspects that had the most impact on them.

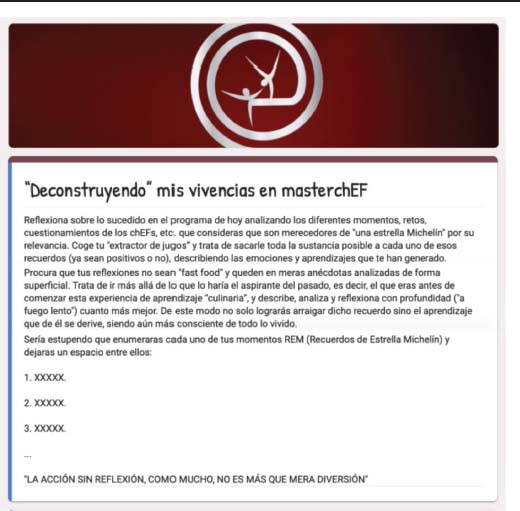

The production of information has been done through the testimonies that the students made throughout the experience (Biglia and Bonet-Martí, 2009). The aim was to understand the depth and transcendence of the teaching-learning process (Bolívar et al., 2001). The information production technique involved the testimonies collected through a questionnaire with an open question on Google Drive. Through this questionnaire they shared, voluntarily and anonymously, their main experiences and perceptions, learning, emotions and other aspects (figure III). A total of 265 testimonies were collected at the end of the project. By having the date of realization, this allowed us to classify the contributions of the students in three moments, relating them with the culinary field:

FIGURE III. Google Drive open question header

Source: Compiled by author.

- “Starters”: first contact with the narrative and structure of the sessions (week 1).

- “Main course”: work of the different contents and competences of the course, and phase of practical PE sessions (from week 2 to week 8).

- “Dessert”: presentation of different products (a board game on contents of the subject of PE and a teaching unit with innovative approach) that happened the same weeks of the semifinal and final of the contest (week 9 and week 10).

The analysis were performed using the NVivo software, by a thematic and categorical analysis (Bernard and Ryan, 2010; Mieles-Barrera et al., 2012; Vaismoradi et al., 2013), which used the initial word frequency to find the key categories (and their corresponding subcategories) derived from the participants’ speech.

Ethics in research was guaranteed by an informed consent approved by the ethics committee of the University of Granada, which guaranteed the confidentiality and anonymity of the participants. At the time of writing the results, the names of the students have been replaced by those of Spanish reference chefs to not reveal the identity of the students.

Results

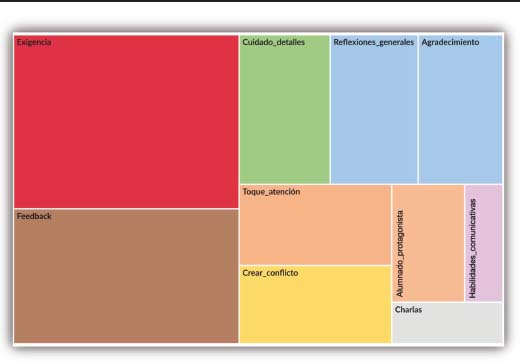

First of all, we should highlight the enormous volume of testimonies that talk about the teaching role, being the most referred category, ahead of some with enormous formative value as “Learning” or “Emotions”. This aspect is of great relevance, because it makes us see the impact that the teacher has in a proposal of gamification. Therefore, we will analyze what characteristics and competencies the students highlight about the teacher role, and the impact that it could have on the degree of use of the proposal, as well as the value that they give to its future professional work.

The starting point will be a hierarchical map, to compare the subcategories related to the teaching role according to the number of references of each of them (figure IV).

FIGURE IV. Hierarchical map of the subcategories that make up “Teaching role”

Source: Compiled by author.

As we can see in figure IV, the “Demanding” is the subcategory to which students most allude, with a total of 95 coding references. In them, the participants highlighted the high intensity and demand of the format, and the fact that the teacher does not agree with the minimum necessary from students but makes them go further to get their best version.

This idea can be seen in the testimony shared by Eneko Atxa, as it reflects on the teaching role and its impact on the degree of achievement of student achievements: «The chEF is very tight and even if you think you have it, he is always able to find something to improve. Without this requirement, it is true that we would have never improved as we did in this subject» (testimony 132). We also find another fragment in which Pedro Subijana reflects on the way a good educator should act, linking it directly with the teacher’s demanding profile:

I believe that squeezing your students within the particular conditions, which the teacher must know, is part of the work of a good educator. Take them to the frontier of their possibilities and once there, they will be able to cross it (testimony 115).

In this line, Valenzuela-Carreño (2007) points out that reducing the level of demand from the teacher would cause a misperception of the value of the effort in academic achievement. In addition, in this context, it will be essential to develop strategies that allow for a coherent response to the needs of the environment. Thus, being able to activate suitable skills to meet the requirements posed at the training level for their subsequent professional transfer (López-Aguilar et al., 2022).

On the other hand, it is interesting to see how this demanding spirit posed by the teacher ends up becoming a requirement towards the students, prioritizing the formative component to the narrative/experiential. All this can be seen in the fragment of Martin Berasategui, in which her degree of critical awareness regarding his own performance is revealed:

I was not among the candidates for elimination, but I was still not happy with myself. When the candidates wearing the black apron (those for elimination) started working, I decided to join them and voluntarily perform the work alongside them. I wanted to take advantage of that day and relieve myself from the thoughts that I might not have deserved to be among the participants saved that week (testimony 20).

This approach that many of the participants had is very meritorious, because it is opposite to the dynamic to which they are accustomed (and whose formula worked for them for years), as perfectly expressed by Elena Arzak, «I’m not saying it can’t be done, because then you can find time for everything, but it is just that we’re not used to being demanded that much. We are used to being given everything done or do things by the path of least resistance» (testimony 188). To be under that demand leads them to discover what they are capable of, and to leave the comfort to which they are accustomed, as is the case of Joan Roca: «these challenges are very hard psychologically and make you see that you can work much more than we believe» (testimony 74).

The second subcategory that stands out is that of “Feedback”, with a total of 74 references. The students emphasize how necessary it is for their formative process to make them see certain things that they were not aware of at first, although it was not always easy to assimilate because, as Eva Arguiñano says, «finally, I wanted to add that all this reflection has been enriched thanks to the feedback that our chEF always gives us, which however hard it is, I do not change it for anything» (testimony 145).

They also mention how important it is to point out individual and group progress, as this recognition motivates them to continue working even more. In fact, the sense of progress is considered one of the fundamental motivators in the educational field (Hailikari et al., 2016) and also in gamification (Kapp 2012; Marczewski, 2018), connecting with the concept of competence from the theory of self-determination (Ryan and Deci, 2000). When a person feels that the proposed challenge is achievable (and not too easy) he improves his skill levels with its execution, allowing him to face even greater challenges. This concept is also related to the flow concept (flow channel) because when you have a clear and immediate feedback, and the level of difficulty of a challenge is properly balance with the competence of the person, you can get into that optimal work area (Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), and connect with intrinsic motivation (Mehta and Vyas, 2022). The testimony of Paco Roncero collected the essence of these ideas as he received the pin recognition of immunity for his good work during the holidays, since he voluntarily worked on the “dishes” that he had not “prepared” properly during the contest: “The chefs have taken into consideration the work I have done during Christmas and the evolution I have had since day one. I felt proud, fulfilled, happy with what I have managed to cook from my harvest...» (testimony 98).

Thirdly, the category “Care of details" should be highlighted, with 33 references. In the testimonies from this category, the participants focus on all the work behind each program: use of language and characteristic objects, adaptation of the main events of the contest, presentation of the ingredients, etc. These details make the difference, as expressed by Carme Ruscalleda «... our chefs did not hesitate to dress up with our soundtrack, and as they said, any excuse is good to show their involvement in this experience, every little detail counts and that is transmitted» (testimony 6). In this sense, when a proposal inspired by an audiovisual reference is made, making the greatest number of similarities and nods to the original reference increases immersion and credibility (Navarro-Mateos and Pérez-López, 2022; Pérez-López and Navarro-Mateos, 2019), and participants like José Andrés value them enormously: «The chef presents the dishes, David Muñoz and I looked to each other, and we love it, this is Masterchef 100%. Further, it is the winner of the previous test the one who distributes the dishes, this is incredible!» (testimony 35).

Students also value the effort required to plan and execute such a project, wanting to reciprocate. This concern is present in many testimonies, highlighting that of Vicky Sevilla: «I do not like to think that after all the effort, the desire and the time that our chefs dedicate to us, they feel disappointed with us, unmotivated or sad» (testimony 196).

Table I presents the matrix with the subcategories and the corresponding temporal moments (“starters”, “main course” or “dessert”), to analyze their evolution throughout the gamification project.

TABLE I. Results of the query matrix in relation to temporal moments

|

Entrante |

Plato_principal |

Postre |

Agradeamteoto |

2 |

19 |

10 |

Alumnado_protagonisha |

7 |

8 |

6 |

Charlas |

2 |

8 |

1 |

Crear_conflicto |

4 |

24 |

1 |

Cuidado detalles |

8 |

20 |

5 |

Exigencia |

25 |

59 |

11 |

Feedback |

8 |

58 |

8 |

General_reflexiones |

2 |

11 |

19 |

Hab_comunicativas |

0 |

10 |

1 |

Toque_atención |

10 |

19 |

1 |

Total |

68 |

236 |

63 |

Source: Compiled by author.

It can be seen how in the “starters” the degree of demand from the teacher stands out, because in that first week they were given enormous emphasis on how important it would be for them to take advantage of this specific training that preceded their teaching work. Thus, we were clear with the approach of the proposal and we also clarify that, for us, this was the best way for them to grow at the formative and personal level. A summary of the above is found in the testimony of Dani García:

From the beginning we could observe the degree of demand from the teacher, and more after not sending the first homework. Undoubtedly, this first class helped me to assimilate what a real job is and what it entails, involvement and effort, but I also know that the satisfaction of doing things well will come, even more after feeling not ok with myself that, which encourages me to excel every day (testimony 30).

All this was connected in a coherent way with the degree of demand that characterizes the Masterchef competition. To recreate the sensations and emotions of the program, a fundamental aspect in gamification (Pérez-López and Navarro-Mateos, 2019), characteristic elements such as the clock that marks the time of cooking were included. In regards to this, Ángel León says that it made them have to manage multiple emotions, a fundamental competence as a future teacher: «Again this day the degree of uncertainty was similar to that of demand. My feeling towards the task posed was initially of enough tension and stress, since we had to work against the clock» (testimony 31).

In regards with the “starters” it is also necessary to mention the subcategory “Wake-up call” because during the first week, the chEF devoted special attention to awareness. The various reflections were directed towards the necessary competences as future teachers and to the deficiencies that each student detected in regards with them, which generated the need to improve their training. In addition, the presentation of the first “ingredients” (such as those related to legislative aspects), which were the common basis of all “dishes”, made participants like Pepe Rodríguez reflect the following:

I have realized that I have no idea of almost anything related to legislation and it is very important for the teaching work, so it is an area in which I have to go much deeper and I must get up to date (testimony 29).

A noteworthy aspect is the ability of the teacher to tell students off when necessary and instead of reducing their involvement, it motivates them to action. In fact, the students are very aware of it and, by living it in the first person, it helps them to be aware of its value and to extrapolate it to their future work, since «... even if you scold us, you motivate us to do things better and demand the maximum. It is something that I would like to be able to do myself, that is to say to tell my future students off at the same time that I motivate them. Here is an objective» (Susi Díaz, testimony 37). Something like this would be complex to achieve if a good classroom climate had not been previously built. An example of this is what Jordi Roca shares: «This reflects how important the climate of a classroom is to favor an emotional and sensitive environment, also trust and comfort, which also encourages participation as has been clearly demonstrated» (testimony 2). There is no doubt that if the teacher is in a bad mood, it creates a tense work environment, in which the students are afraid to participate and if, on the contrary, the teacher is close and motivates them to learn with effort and dedication, the predisposition that will generate in the students will be completely different (Peña and Wandosell, 2015).

With respect to the “main course”, the “Demand” stands out in a remarkable way, together with the “Feedback”. During these weeks, topics and skills directly related to their professional work were addressed, such as planning in PE, active methodologies, the teaching intervention guidelines to be taken into account in the practical sessions or different evaluation instruments. At all times we tried to squeeze the full potential of the contestants, being very aware of it Andoni Luis Aduriz «... all teams were working in a good way today so I wanted to see our nomination as a favor for ourselves. Perhaps the chEF wanted to force our group to get something different from us next time. Honestly, he got this» (testimony 102).

In fact, in a large number of references related to “Demand” and “Feedback”, the contestants are the ones who directly assume the responsibility and consequences of their decisions, denoting a high level of maturity. A good example of this is the story shared by Karlos Arguiñano: «I arrived nervous because I was not able to send my homeworks to the chEF in time, so again I thank you chEF for doing what you thought was right» (testimony 119). In fact, another gesture that denotes enormous maturity is shown by Alberto Chicote, because he is able to understand that giving the best version of oneself is a gesture of generosity, since «that the fact that level is high makes us all improve more, because we cannot relax but give our best instead» (testimony 149).

Finally, in the “main course” the subcategory “Create conflict” is analyzed, understood as that cognitive flexibility that is required to adapt to new circumstances (Diamond, 2013). This is a basic competence for teachers in training, because tomorrow they will have to be able to adapt to the requirements of complex and changing situations (Mamani-Ruiz, 2017; Savchuk et al., 2020). For this purpose they were tested in the different “cooking”, breaking the schemes so that they trained their resilience and were able to react to unexpected situations. An example of a test in which it was carried out is narrated by Quique Dacosta: «Four captains were appointed (I was one of them) to prepare the dishes of the next day, forming groups in which a surprise arose, rotating of group» (testimony 111). Fina Puigdevall delves into the emotions and sensations that this change of groups generated in the captains:

I love that unexpected things like this happen, that force us to change and adapt from one moment to another. Above all, the place of the captains had to be even weirder, since I’m sure they were thinking who to choose and why, and suddenly... they ran into a new team, composed of members whom they had not chosen (testimony 121).

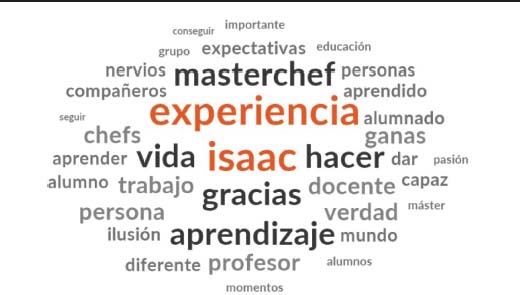

We arrived at the final part: the “dessert”. In this part the “Demand” subcategory remains present, a constant throughout the proposal. The subcategory with the most references in this case is that of “General reflections”. In it the participants took stock of the experience, shared their feelings and summarized their perception with respect to the experience and the teacher. Some people pointed out that it was an unforgettable experience, not only because of what was lived, but because of the applicability of the resources learned, as Toño Pérez says: «It is not a common subject you have in college. It has been a process that will never be forgotten and I hope that in my days as a teacher, if I ever arrive, I will use all the resources learned» (testimony 253). In addition, in this last phase the gratitude to the teacher was constant, as can be seen in figure V.

FIGURE V. Word cloud that make up the dessert of the category “Teaching role”

Source: Compiled by author.

To conclude and, in order to connect with the ideas discussed in the introduction, a fragment is shared in which Ferran Adrià extracts the MasterchEF juice and the essence of the teaching-learning process:

I would like to highlight that of which is talked up so much, the one-to-one correspondence, which is to establish a symbiotic relationship in the teaching-learning process of a student, so that a synergy is formulated between teacher and student. This teaching and therefore learning must be reciprocal and bidirectional (testimony 115).

Conclusions

In this article we have described the main aspects to take into account when adapting a talent show, specifically, the Masterchef television program, to the training of future teachers in the Master’s degree in teaching. To recreate the essence of the contest and, therefore, generate sensations and emotions similar to those experienced by the participants of the original program, it will be essential to include the structure, language and characteristic objects. At the same time, the perceptions and assessments of the participating students on the role of the teacher in the proposal have been shown. The three fundamental aspects that stood out from him were: the demand, the feedback and the care of details. These “ingredients” together with others such as, for example, the transfer of learning to their future teaching work or the students leading role, characteristic of active methodologies, had an impact on the development of their skills and the degree of acquisition of the contents of the course. Therefore, the role of teachers is a differentiating element in this type of approach, fostering a greater degree of involvement of students and satisfaction with the proposal.

With regard to future lines of research, it would be interesting to analyze the impact of the teacher in a proposal built on a PBL system, to see if its incidence would be greater, or not, than in an approach such as the one described here. Another possibility would be to make the comparison using, instead of a television program, a film reference (television series or films), given the great significance they also have for today’s young people.

Acknowledgements

This research has been carried out thanks to a pre-doctoral contract from the Junta de Andalucía.

Bibliographical references

Albornoz, L., & García, M. T. (2022). Netflix Originals in Spain: Challenging diversity. European Journal of Communication, 37(1), 63-81. https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231211012174

Alonso-Sainz, T. (2021). ¿Qué caracteriza a un” buen docente”? Percepciones de sus protagonistas. Profesorado, revista de currículum y formación del profesorado, 25(2), 165-191. https://doi.org/10.30827/profesorado.v25i2.18445

Andrade H. L., & Brookhart S. M. (2020). Classroom assessment as the co-regulation of learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 27(4), 350–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2019.1571992

Arufe-Giráldez, V. (2019): Experiencia didáctica de una adaptación de tres famosos programas de TV: First Dates, MásterChef y Pekín Express al aula universitaria. In E. De la Torre Fernández (Ed.), Contextos universitarios transformadores: construíndo espazos de aprendizaxe (pág. 99-116). Universidad de A Coruña.

Bernard, H. R., & Ryan, G. W. (2010). El análisis de datos cualitativos: enfoques sistemáticos. In Analyzing qualitative data: Systematic approaches (pp. 3–16). SAGE Publications.

Biglia, B., & Bonet-Martí, J. (2009). La construcción de narrativas como método de investigación psico- social. Prácticas de escritura compartida. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 10(1). https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/download/1225/2665?inline=1

Black, C. (2001). Un gars, une fille: plaidoyer pour la culture avec un ‘petit c’dans un cours de français langue étrangère. Canadian modern language review, 57(4), 628-639. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.57.4.628

Bolívar, A., Domingo, J., & Fernández, M. (2001). La investigación biográfico-narrativa. Enfoque y metodología. La Muralla.

Cortés-Quesada, J. A., Barceló-Ugarte, T., & Fuentes-Cortina, G. (2022). Estudio sobre el consumo audiovisual de la Generación Z en España. Fonseca, Journal of Communication, 24(18), 19-32. http://hdl.handle.net/10366/150230

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Beyond boredom and anxiety. Jossey-Bass.

Denzin, N. K. (2010). Moments, mixed methods, and paradigm dialogs. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(6), 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410364608

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2012). Introducción general. La investigación cualitativa como disciplina y como práctica. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), El campo de la investigación cualitativa (Vol. I, pp. 43–116). Gedisa.

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual review of psychology, 64, 135-168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

Dicheva, D., Dichev, C., Agre, G., & Angelova, G. (2015). Gamification in education: A systematic mapping study. Journal of educational technology & society, 18(3), 75-88. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.18.3.75

Domínguez-Márquez, M. (2019). Neuroeducación: elemento para potenciar el aprendizaje en las aulas del siglo XXI. Educación y ciencia, 8(52), 66-76.

Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., Lüdtke, O., Pekrun, R., & Sutton, R. E. (2009). Emotional Transmission in the Classroom: Exploring the Relationship Between Teacher and Student Enjoyment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(3), 705-716. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014695

Fuster, D. E. (2019). Investigación cualitativa: Método fenomenológico hermenéutico. Propósitos y Representaciones, 7(1), 201–229. https://doi.org/10.20511/pyr2019.v7n1.267

González, V., & Pujolà, J. T. (2021). Del juego a la gamificación: una exploración de las experiencias lúdicas de profesores de lenguas extranjeras. In F. J. Hinojo, S. V. Arias, M. N. Campos & S. Pozo (Eds.), Innovación e investigación educativa para la formación docente. (pp. 398-412). Dykinson S.L.

González-Castro, I., Vázquez-García, M. A., & Zavala-Guirado, M. A. (2021). La desmotivación y su relación con factores académicos y psicosociales de estudiantes universitarios. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.19083/ridu.2021.1392

Guerrero-Pérez, E. (2018). La fuga de los millennials de la televisión lineal. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 73, 1231-1246. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2018-1304

Hailikari, T., Kordts-Freudinger, R., & Postareff, L. (2016). Feel the Progress: Second-Year Students’ Reflections on Their First-Year Experience. International Journal of Higher Education, 5(3), 79-90. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v5n3p79

Hernández, R. M., Orrego, R., & Quiñones, S. (2018). Nuevas formas de aprender: La formación docente frente al uso de las TIC. Propósitos y representaciones, 6(2), 671-685. https://doi.org/10.20511/pyr2018.v6n2.248

Huilin, Z., & Hyangkeun, S. (2020). A Study on the Self-directed Learning Using TV Shows-Focusing on Education for Korean Culture in Universities of China. Journal of the International Network for Korean Language and Culture, 12(1), 283-308. https://www.earticle.net/Article/A373650

Kapp, K. M. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: game-based methods and strategies for training and education. John Wiley & Sons.

Klein, B. (2011). Entertaining ideas: Social issues in entertainment television. Media, Culture & Society, 33(6), 905-921. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443711411008

Landers, R. N. (2014). Developing a theory of gamified learning: linking serious games and gamification of learning. Simulation & Gaming, 45(6), 752–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878114563660

Liu, H. (march of 2018). Reflections on Teaching Role Transformation of University Teachers in the New Period. In 2nd International Conference on Culture, Education and Economic Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2018) (pp. 53-55). Atlantis Press.

López-Aguilar, D., Álvarez-Pérez, P. R., & Ravelo-González, Y. (2022). Capacidad de adaptabilidad e intención de abandono académico en estudiantes universitarios. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 40(1), 237-255. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.463811

Mamani-Ruiz, T. H. (2017). Efecto de la adaptabilidad en el rendimiento académico. Educación Superior, 2(1), 38-44. http://www.scielo.org.bo/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2518-82832017000100004&lng=es&tlng=es.

Marczewski, A. (2018). Even Ninja Monkeys like to play. Unicorn Edition. Gamified UK.

Marín, M., Martínez-Pecino, R., Troyano, Y., & Teruel, P. (2011). Student perspectives on the university professor role. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 39(4), 491-496. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2011.39.4.491

Mehta, P., & Vyas, M. (2022). A Systematic Literature Review on the Experience of Flow and its Relation to Intrinsic Motivation in Students. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(3), 299-304. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/systematic-literature-review-on-experience-flow/docview/2723857415/se-2

Mieles-Barrera, M. D., Tonon, G., & Alvarado, S. V. (2012). Investigación cualitativa: el análisis temático para el tratamiento de la información desde el enfoque de la fenomenología social. Universitas Humanística, 74, 195–226. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0120-48072012000200010&lng=en&tlng=es.

Mora, F. (2017). Neuroeducación: Solo se puede aprender aquello que se ama. Editorial Alianza.

Navarro-Mateos, C., & Pérez-López, I. J. (2022). A phone app as an enhancer of students’ motivation in a gamification experience in a university context. Alteridad. Revista de Educación, 17(1), 64-74.

Navarro-Robles, M., & Vázquez-Barrio, T. (2020). El consumo audiovisual de la Generación Z. El predominio del vídeo online sobre la televisión tradicional. Ámbitos: Revista internacional de comunicación, 50, 10-30. https://doi.org/10.12795/Ambitos.2020.i50.02

Okada, R. (2023). Effects of Perceived Autonomy Support on Academic Achievement and Motivation Among Higher Education Students: A Meta‐Analysis. Japanese Psychological Research, 65(3), 230-242. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpr.12380

Orón, J. V., & Blasco, M. (2018). Revealing the hidden curriculum in higher education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 37, 481-498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-018-9608-5

Oudeyer, P. Y., Gottlieb, J., & Lopes, M. (2016). Intrinsic motivation, curiosity, and learning: theory and applications in educational technologies. Progress in brain research, 229, 257-284. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2016.05.005

Peña, B., & Wandosell, G. (2015). The Emotional Leadership of Managers Applied to University Teaching Role. In 2015 International Conference on Education Reform and Modern Management (pp. 128-130). Atlantis Press.

Pérez-López, I. J., & Navarro-Mateos, C. (2019). Gamificción: qué, cómo y por qué. Un relato basado en hechos reales. In 15º Congreso Internacional de Ciencias del Deporte y la Salud (pp. 108-119). Sportis.

Pérez-López, I. J., & Navarro-Mateos, C. (2022a). Gamificación: lo que es no es siempre lo que ves. Sinéctica, 59. https://doi.org/10.31391/S2007-7033(2022)0059-002

Pérez López, I. J., & Navarro Mateos, C. (2022b). Gamificar en tiempos revueltos. Tándem: didáctica de la educación física, 76, 60-68. https://hdl.handle.net/11162/235951

Pérez-López, I. J., & Navarro-Mateos, C. (2023a). “Ese profe me suena”: una experiencia de innovación docente en el Máster de Profesorado. In Educar para transformar: Innovación pedagógica, calidad y TIC en contextos formativos (pp. 2015-2021). Dykinson.

Pérez-López, I. J., & Navarro-Mateos, C. (2023b). Guía para gamificar. Construye tu propia aventura. Copideporte S.L.

Pires, F. (2021). The Wheel of Competencies to Enhance Student-Teacher Role Awareness in Teaching-Learning Processes: The Use of a Classical Coaching Tool in Education. In Z- Hunaiti (Ed.), Coaching Applications and Effectiveness in Higher Education (pp. 48-77). IGI Global.

Poulou, M. (2014). The effects on students’ emotional and behavioural difficulties of teacher–student interactions, students’ social skills and classroom context. British Educational Research Journal, 40(6), 986-1004. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3131

Reeve, J. (2006). Teachers as Facilitators: What Autonomy-Supportive Teachers Do and Why Their Students Benefit. The elementary school journal, 106(3), 225-236. https://doi.org/10.1086/501484

Robbins, S. B., Lauver, K., Le, H., Davis, D., Langley, R., & Carlstrom, A. (2004). Do Psychosocial and Study Skill Factors Predict College Outcomes? A Meta-Analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 130(2), 261–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.261

Rodríguez-Pérez, N. (2012). Causas que intervienen en la motivación del alumno en la enseñanza aprendizaje de idiomas: el pensamiento del profesor. Didáctica, Lengua y Literatura, 24, 381-409. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_DIDA.2012.v24.39932

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. L. (2000). La Teoría de la Autodeterminación y la Facilitación de la Motivación Intrínseca, el Desarrollo Social, y el Bienestar. American psychologist, 55(1), 68-78.

Sailer, M., & Homner, L. (2020). The gamification of learning: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 32(1), 77-112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09498-w

Savchuk, B., Kondur, O., Rozlutska, G., Kohanovska, O., Matishak, M., & Bilavych, H. (2020). Formation of cognitive flexibility as a basic competence of the future teachers’ multicultural personality. Space and Culture, India, 8(3), 48-57. https://doi.org/10.20896/saci.vi0.1016

Silverman, D. (2001). Interpreting Qualitative Data. SAGE Publications.

Subhash, S., & Cudney, E. A. (2018). Gamified learning in higher education: A systematic review of the literature. Computers in human behavior, 87, 192-206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.028

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing and Health Sciences, 15(3), 398–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

Valenzuela, J., Muñoz-Valenzuela, C., Silva-Peña, I., Gómez-Nocetti, V., & Precht-Gandarillas, A. (2015). Motivación escolar: Claves para la formación motivacional de futuros docentes. Estudios pedagógicos (Valdivia), 41(1), 351-361. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07052015000100021

Valenzuela-Carreño, J. (2007). Exigencia académica y atribución causal: ¿qué pasa con la atribución al esfuerzo cuando hay una baja significativa en la exigencia académica? Educere, 11(37), 283-287. http://ve.scielo.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1316-49102007000200014&lng=es&tlng=es.

Van Laer S., & Elen J. (2017). In search of attributes that support self-regulation in blended learning environments. Education and Information Technologies, 22(4), 1395–1454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-016-9505-x

Van Manen, M. (2017). But Is It Phenomenology? Qualitative Health Research, 27(6), 775–779. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317699570

Wang, D. (2012). Self-directed English Language Learning Through Watching English Television Drama in China. Studies in Culture and Education, 19(3), 339-348. https://doi.org/10.1080/1358684X.2012.704584

Wubbels, T. (2005). Student perceptions of teacher-student relationships in class. International Journal of Educational Research, 43(1-2), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2006.03.002

Yoon, J. S. (2002). Teacher characteristics as predictors of teacher-student relationships: Stress, negative affect, and self-efficacy. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 30(5), 485-494. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2002.30.5.485

Zichermann, G., & Cunningham, C. (2011). Gamification by design. O’Reilly.

Contact address: Carmen Navarro Mateos. Universidad de Granada. Facultad de Ciencias del Deporte. Departamento de Educación Física y Deportiva.Camino de Alfacar, 21, 18071 Granada. E-mail: carmenavarro@correo.ugr.es