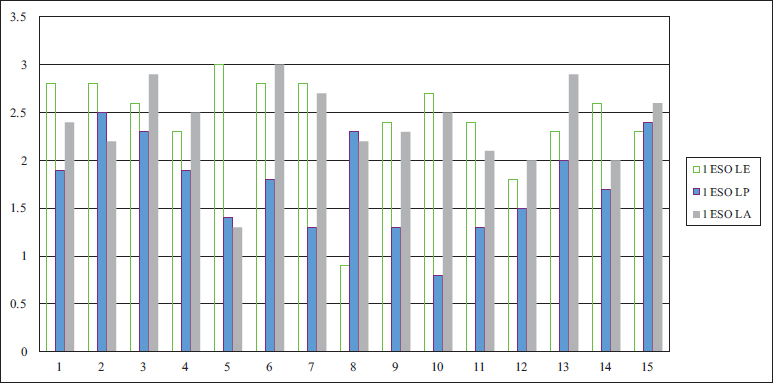

GRAPH I. Evolution of tests results at Las Encinas School between Y1st and Y3rd ESO

Source: Compiled by the author based on data.

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2024-403-605

Elena del Pozo Manzano

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1645-5491

Universidad Autónoma de Madrid

Abstract

CLIL has been the most common methodological approach in bilingual teaching in Western Europe since the 1990s. It was created as a formula to define the teaching and learning of subject-matter content (non-linguistic) through a foreign language. The present study proposes to evaluate both competences: linguistic and subject specific, in the context of integrated learning of history in English. Starting from a formative assessment, an exploratory longitudinal experimental study is conducted. It examines a research problem that has hardly been studied from the perspective of a content teacher who is not a specialist in linguistics. The sample for the analysis is the written essays of 45 students from three public bilingual schools in three different towns, belonging to bilingual English groups in Y1 and Y3 ESO in the school subject of Social Sciences: Geography and History. This study is part of a larger research about the acquisition of history through English in secondary schools. The H-CLIL assessment model, consisting of rubrics designed ad hoc for the analysis of written texts is presented. It considers Dalton-Puffer’s (2013) Cognitive Discourse Functions (CDF), which relate the learning objectives of the subject, interaction in the classroom, and production of discourse in a foreign language. The study aims to analyze the evolution in the acquisition of history knowledge by secondary school students in bilingual schools, and their ability to express that knowledge in an essay. Despite the limitations of the study, it can be inferred that students maintain a similar rate of learning history content, aligned with the curriculum requirements, in the two academic years and an even better-written expression in Y3 ESO. It can be concluded that there is no loss of knowledge of the subject by studying it in a foreign language although more research is needed on this matter.

Keywords: CLIL, formative assessment, history, research, discourse, teaching, integrated learning, H-CLIL model.

Resumen

AICLE (Aprendizaje Integrado de Contenido y Lengua Extranjera) o CLIL ha sido el enfoque metodológico más común en la enseñanza bilingüe en Europa occidental desde los años 90 del siglo XX (Cenoz, Genesee y Gorter, 2014). Se creó como una fórmula para configurar la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de contenidos de una materia (no lingüística) a través de una lengua extranjera. Este estudio propone evaluar ambas competencias (lingüística y la propia de la materia no lingüística) en el contexto de un aprendizaje integrado de contenidos de Historia en inglés. Partiendo de la evaluación formativa, se presenta aquí un estudio experimental longitudinal exploratorio que examina un problema de investigación que ha sido poco estudiado desde el punto de vista del profesorado de contenidos no especialista en lingüística. La muestra para el análisis es la producción escrita de 45 alumnos de tres centros públicos bilingües en tres localidades diferentes pertenecientes a grupos bilingües en inglés en 1º y posteriormente en 3º de ESO en la asignatura de Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia. Se trata de parte de una investigación mayor acerca de la adquisición de conocimientos de Historia en lengua extranjera por alumnos de secundaria. Se presenta el modelo H-CLIL de evaluación, consistente en rúbricas diseñadas ad hoc para el análisis de textos escritos, teniendo en cuenta las Funciones Cognitivas del Discurso (CDF) de Dalton-Puffer (2013), que relacionan los objetivos de aprendizaje de la asignatura, la interacción en el aula y la producción del discurso en lengua extranjera. El objetivo del estudio es analizar la evolución en la adquisición de conocimientos de historia por alumnos de secundaria bilingüe y su capacidad para expresar esos conocimientos en un texto escrito. A pesar de las limitaciones del estudio, se puede inferir que los alumnos mantienen un ritmo de aprendizaje de contenidos de historia acorde a los requeridos en el currículo para ambos niveles académicos y una mejor expresión escrita en 3ºESO. Con todo ello se concluye que no hay pérdida de conocimientos de la asignatura por cursarla en lengua extranjera, si bien es necesaria más investigación sobre este tema.

Palabras clave: AICLE, evaluación formativa, Historia, investigación, discurso, enseñanza, aprendizaje integrado, modelo H-CLIL.

Assessment is an effective pedagogical tool when there is a thorough understanding of what is going to be assessed, and the teaching process is designed to achieve the learning objectives. In 2014 Andreas Schleicher, Director of Education at the OECD, pointed out that quality should not be sacrificed to the detriment of equity: the more equity in educational resources, the better the results. In his analysis of assessment in Spain, Schleicher noted that equity is one of its strong points, with free compulsory education for all and the promotion of resilience. However, he added that the way of evaluating and retaking a course has negative effects on equity and makes education more expensive (Schleicher, 2014). Therefore, action should focus on the evaluation of the teaching and learning process from its beginning. This idea is also present in the evaluation in bilingual education: “Assessment is so fundamental to the success of CLIL that it needs to be considered and planned for in detail before any teaching takes place (…); assessment is not something that comes after instruction, but it is an indispensable part of instruction” (Llinares, Morton and Whittaker, 2012: 280). The Spanish regulation on evaluation in secondary education does not distinguish between bilingual and non-bilingual education but does refer to its objective, continuous, formative and integrated nature (LOMLOE, 2020). In other words, a formative assessment of the learning process is advocated as opposed to a summative assessment of the learning outcomes.

Summative assessment also has advantages: it is a precise diagnostic tool that reflects students’ knowledge at a given moment and helps teachers identify specific learning problems (McLoughling, 2021). However, it does not involve students in their own assessment process, as formative assessment does. The implementation of a formative assessment approach in CLIL is taking time to occur since it involves a substantial methodological change (Otto & Estrada-Chichón, 2019): it must be integrated into the teaching and learning process, not outside of it, and extended throughout the course, not just at a specific moment.

Formative assessment emerges as the best option for meaningful teaching and the students’ history portfolio can help reflect their progressive learning of the subject. The portfolio includes students’ essays -such as those used in the research presented in this article-, oral presentations, projects, short activities, and self and peer assessments. It can be used as an additional assessment tool for the subject content. Through the development of a history portfolio, students become more deeply engaged with historical issues since they learn how their contributions can impact them (Del Pozo, 2009). Furthermore, it is an instrument that allows assessing the use of language in the context of a non-linguistic subject, rather than the language in isolation. The teaching and learning process in history is structured into conceptual content (eg. the conquest of Granada), procedural skills (e.g. differentiation and description of assault campaigns), and the linguistic skills employed for the purpose (connectors, adjectives and comparatives used in the description) (Ball, Clegg y Kelly, 2015). To introduce the component of formative assessment into the equation, Mahoney incorporates others that contribute to assessing what students can do when learning content in a foreign language: purpose, use, method and instrument (2017). The factors that shape the assessment for integrated learning of history through a foreign language -within the context of a formative assessment-, determine the decisions that teachers make about what to assess (content, purpose), how to assess it (procedure, instrument), why to assess it (usage) and when to assess it (method, sequencing). Based on these factors, teachers adopt a specific pedagogical approach, design their teaching units to achieve the goals set out in the assessment criteria, and adapt their teaching practices accordingly (Council of Europe, 2020). The following sections of this article show a case study that illustrates the application of the H-CLIL model for the integrated assessment of history and language as part of a formative assessment practice.

Traditionally, in the assessment of historical knowledge, some teachers focused on students memorizing a huge amount of data, what Counsell called fingertip: only the superficial was evaluated. However, it failed to consider that the true value lies in students’ understanding of the processes of change that occur in history, the residue -what remains when the anecdotal is forgotten- (Counsell, 2000). Cercadillo contributed to adding the international dimension to the acquisition of historical knowledge: “Alternative assessment approaches must be explored and international assessment of ‘historical understanding’ may represent a potentially useful option not affected by national bias” (Cercadillo, 2006: 94).

For assessment to be formative, that is, to have an impact on the teaching and learning process, it must be focused on success criteria, aimed at ensuring the success of students (Pascual y Basse, 2017), which really value the residue. These criteria should address the learning objectives of each subject, which are included in the curricula (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2021). The teaching objectives place the focus on the conceptual content of the subject, but responsibility for the results of the learning evaluation lies in the validity of the instruments used to evaluate (Mahoney, 2017). On the other hand, the curricular contents substantiate the learning objectives but are separated from them to determine what should be assessed in each subject and academic level. For the proper development of the process, mediators are used to make it possible to achieve the success criteria with sufficient guarantee that all students, without exclusion, can work on and achieve them at their own pace (González et al., 2015). The last element, and the one that will be largely addressed in this study, is the rubric as the instrument that articulates the components of the learning to be assessed with the expectations of teaching a subject content at a specific academic level (López Pastor y Pérez Pueyo, 2017).

For this research, students were asked to write about historical events that they had previously studied in their history lessons in an essay that would be part of their portfolio. This task may be more effective in enabling students to express their historical knowledge than a true-false test (Ravid, 2005), however effortless the latter may seem, and easier to analyze statistically. When writing an essay, students articulate their ideas, reflect on the questions posed to them, and enhance their linguistic competence in conveying curriculum-related content that is not strictly linguistic (Del Pozo & Llinares, 2021). Consequently, the topics prompted for the essays to be written by the participants in this study, in both Y1 and Y3ESO, were aligned with the curriculum guidelines for history (LOMLOE, 2020):

The scoring of the essays was from 0 to 3 points. This is an exploratory longitudinal experimental study since the data were collected from the same groups of students at two different academic moments (Cubo et al, 2011) with two years of difference between them: Y1st ESO and Y3rd ESO. The researcher considered that a one-year gap between the data collection could have been sufficient to observe changes in the acquisition of historical knowledge and essay-writing skills. However, it was anticipated that a two-year interval would yield more statistically significant results. The exploratory approach of the study is grounded in the fact that it examines an issue that has not been extensively studied from the perspective of a historian. By definition, exploratory approaches identify trends, contexts and potential relationships between variables, but require more extensive research (Hernández Sampieri et al, 2010; Cubo et al, 2011), as is the case of this study. The first goal was to assess how students’ learning of history had progressed over time and whether it had maintained a consistent path, unaffected by the language of instruction as a potential barrier to their learning. The second objective was to analyze the written expression of history in a foreign language. The starting point was a null hypothesis: secondary school students who study history in a foreign language experience content loss and a reduction in their written expression due to having learned it in a foreign language. The research questions were:

RQ1: To what extent do secondary school students acquire history content as measured by a written essay? (Independent variable)

RQ2: Are there differences (in terms of the evolution of integrated learning of history content in English) when students acquire knowledge in 1st and 3rd years of secondary education? (Dependent variable)

The phases in the study were:

The written tests were encrypted to protect the data of the participating students and schools, and corrected by applying the rubrics of the H-CLIL model; the data were processed with the SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) software (IBM, 2020). The mean, median, mode, standard deviation and variance were estimated from the total data obtained from the tests. Finally, graphs were created in a spreadsheet that better illustrated the results obtained to be presented here.

The study participants were 45 students from three public secondary schools with a bilingual English programme (Las Encinas, Los Pinos y Los Álamos: pseudonyms) in three different towns. The students were in the Y1st ESO during the initial data dollection and in the Y3rd ESO two years later, at the time of the second data collection. Schools of a similar socio-economic profile were selected to ensure that the samples were initially homogeneous. Approximately 80% of the participating students were of Spanish origin, with Spanish as their native language; 20% came from immigrant families: 5% from Eastern Europe (with a native language other than Spanish and English), 12% from Latin America (with Spanish as their native language), 2% from China (with Mandarin as their native language) and 1% from Morocco (with Arabic as their native language). All of them had English as a first or second foreign language, and they had all completed their primary education in public English bilingual schools. The three schools were located in neighbourhoods with a profile of working class families. Los Álamos and Las Encinas schools were the first to implement a bilingual programme, Los Pinos school followed seven years later.

The history teachers in the groups of participating students were qualified to teach in the bilingual programme and they only assisted in the collection of the tests, not taking part in them. Initially, more students were participating, but those who left the school before the study concluded, retook a year course, declined to participate, or did not meet the requirements for the research to be as consistent as possible, were discarded. It was agreed with the teachers that students with special educational needs and students with high abilities would not participate since that was not the object of the study, and the tests were not adapted to their needs.

Relationship of the data collected from the participants with the variables in the research:

The tests were taken in the three schools during the first term of Y1st ESO but rubrics were applied for correction only after the second test in Y3rd ESO, when they had been refined and their effectiveness had been tested. Rubrics designed ad hoc for the assessment were applied taking into account both the historical content and the language used by students in their essays: H-CLIL rubrics.

The rubric, as an assessment tool, takes each educational objective and develops scales -or descriptors- about what students know and can do. It is used to assess students’ performance (Barbero, 2012) and it is presented in the form of a matrix. As noted by Newell et al. (2002) regarding the creation of rubrics, the highest levels of attainment indicate metacognition in students’ knowledge of the topic they are writing about; the lowest levels reflect what they still need to learn and improve; and in the middle are intermediate levels of attainment. For this study, holistic or comprehensive rubrics were not used -with scores like excellent, good, satisfactory…-, but rather analytical rubrics -with a numerical index of attainment of the participating students- were designed for the H-CLIL model to provide reliable quantitative data, more suitable for the research (Hernández Sampieri et al., 2010). Success criteria were followed in the rubric design, ensuring that even the smallest piece of historical information provided by the participants was considered. The objective was to attribute solid value to what the students knew and were able to express. A rubric was designed for each academic level -Y1st and Y3rd ESO- that analyzed the same parameters of content and language for each level, so that the progressive assimilation of historical knowledge and language writing skills could be studied (De Oliveira, 2011; Del Pozo, 2019).

The degree of knowledge required in history and language expression in each of the two selected academic levels is different. Regardless of the vehicular language used, history teachers expect an evolution both in the acquisition of the content learnt and its expression in a written essay. Obviously, this is not evident in the results of all the tests analyzed in this study since the cognitive development of students is not uniformly consistent (Wineburg, 1996). Thus, each rubric was articulated around Dalton-Puffer’s Cognitive Discourse Functions construe (henceforth CDF) (2013). While Krathwohl (2002) revised Bloom’s taxonomy (1956) providing the dimension of knowledge, Dalton-Puffer synthesizes both models and indicates to what extent the specific cognitive learning objectives of a subject -in this case history- are linked to the written production of students in the tests (Dalton-Puffer, 2013). Besides, the CDF construct provides teachers with a tangible means to perceive how the content and the language needed to learn, integrate in the classroom. It has “proven to be a relevant tool for exploring academic language in contact with content areas” (Lorenzo, 2017: 40), such as history. By including the component of analysis of the metalanguage used for teaching and learning, it facilitates the teaching and learning process in CLIL contexts (Gerns, 2023). The CDFs are articulated around the following classification (Table I):

TABLE I. Cognitive Discourse Functions

Function type |

Communicative intention |

Label |

CLASSIFY |

Type 1 I tell you how we can cut up the world according to certain ideas |

Classify, contrast, match |

DEFINE |

Type 2 I tell you about the extension of this object of specialist knowledge |

Identify, characterize |

DESCRIBE |

Type 3 I tell you details of what can be seen (also metaphorically) |

Label, name, specify |

EVALUATE |

Type 4 I tell you what my position is vis a vis X |

Judge, argue, justify, reflect |

EXPLAIN |

Type 5 I give you reasons for and tell you the cause/s of X |

The reason, express, cause/effect, deduce |

EXPLORE |

Type 6 I tell you something that is potential |

Hypothesize, speculate, predict |

REPORT |

Type 7 I tell you about something. external to our immediate context on which I have a legitimate knowledge claim |

Inform, recount, narrate |

Source: Dalton-Puffer, 2013.

The CDF Classify was recently revised and renamed as Categorize (Evnitskaya & Dalton-Puffer, 2023). The specific CDF that were included in the tests were Describe, Report, Explain and Explore. All of them are present in the curriculum of history in secondary, what reinforces the idea that CDF are part of the process of learning (BOE, 2022). The rubrics following the H-CLIL model for Y1stESO (see Appendix I) and Y3rdESO (see Appendix II) were designed taking into account the following criteria prompted in the essay:

The tests administered were scored on a 3-point scale. First, quantitative data from the tests will be presented, followed by the most relevant linguistic aspects of the essays. The data collected were processed with the SPSS software (V. 27.0, IBM, 2020) and the measurements of tendency were obtained for every array of data: mean, median, mode, standard deviation and variance (Table II).

TABLE II. Results of the tests in the schools and measurements of general tendency

Las Encinas School |

|

Los Pinos School |

|

Los Álamos School |

|

||||||

|

1stESO |

3rdESO |

DIFF |

|

1stESO |

3rdESO |

DIFF |

|

1stESO |

3rdESO |

DIFF |

LE1 |

2,8 |

2,8 |

0 |

LP1 |

1,9 |

2,3 |

0,4 |

LA1 |

2,4 |

2,2 |

-0,2 |

LE2 |

2,8 |

2,7 |

-0,1 |

LP2 |

2,5 |

2,8 |

0,3 |

LA2 |

2,2 |

2,7 |

0,5 |

LE3 |

2,6 |

2,8 |

0,2 |

LP3 |

2,3 |

2,6 |

0,3 |

LA3 |

2,9 |

2,8 |

-0,1 |

LE4 |

2,3 |

2 |

-0,3 |

LP4 |

1,9 |

1,7 |

-0,2 |

LA4 |

2,5 |

2,8 |

0,3 |

LE5 |

3 |

2,8 |

-0,2 |

LP5 |

1,4 |

1,3 |

-0,1 |

LA5 |

1,3 |

1,9 |

0,6 |

LE6 |

2,8 |

3 |

0,2 |

LP6 |

1,8 |

2 |

0,2 |

LA6 |

3 |

2,6 |

-0,4 |

LE7 |

2,8 |

3 |

0,2 |

LP7 |

1,3 |

1,6 |

0,3 |

LA7 |

2,7 |

2,8 |

0,1 |

LE8 |

0,9 |

1,4 |

0,5 |

LP8 |

2,3 |

2,2 |

-0,1 |

LA8 |

2,2 |

2,7 |

0,5 |

LE9 |

2,4 |

2,6 |

0,2 |

LP9 |

1,3 |

1,9 |

0,6 |

LA9 |

2,3 |

2,5 |

0,2 |

LE10 |

2,7 |

2,8 |

0,1 |

LP10 |

0,8 |

1,9 |

1,1 |

LA10 |

2,5 |

2,3 |

-0,2 |

LE11 |

2,4 |

2,6 |

0,2 |

LP11 |

1,3 |

2 |

0,7 |

LA11 |

2,1 |

2,2 |

0,1 |

LE12 |

1,8 |

2,5 |

0,7 |

LP12 |

1,5 |

1,8 |

0,3 |

LA12 |

2 |

2,4 |

0,4 |

LE13 |

2,3 |

2,1 |

-0,2 |

LP13 |

2 |

2,3 |

0,3 |

LA13 |

2,9 |

2,5 |

-0,4 |

LE14 |

2,6 |

2,4 |

-0,2 |

LP14 |

1,7 |

2,2 |

0,5 |

LA14 |

2 |

2,2 |

0,2 |

LE15 |

2,3 |

2,6 |

0,3 |

LP15 |

2,4 |

2,8 |

0,4 |

LA15 |

2,6 |

2,6 |

0 |

mean |

2,43 |

2,54 |

0,11 |

mean |

1,76 |

2,09 |

0,33 |

mean |

2,37 |

2,48 |

0,11 |

median |

2,6 |

2,6 |

|

median |

1,8 |

2 |

|

median |

2,4 |

2,5 |

|

mode |

2,8 |

2,8 |

|

mode |

1,3 |

2,3 |

|

mode |

2,2 |

2,2 |

|

Σ |

0,52 |

0,43 |

|

Σ |

0,49 |

0,43 |

|

Σ |

0,44 |

0,27 |

|

VAR |

0,27 |

0,18 |

|

VAR |

0,24 |

0,18 |

|

VAR |

0,19 |

0,07 |

|

Source: Compiled by the author based on data.

The mean provides information about the centre of data distribution and was expected to remain within a close range. This was the case for Las Encinas and Los Alamos schools, where the mean remained consistent between the Y1st and Y3rd ESO tests with a minimal variation of 0.11. In contrast, in Los Pinos School there was a difference of 0.33 points between the two tests. This could be attributed to the fact that when the participating students took the initial test, the bilingual programme had just been implemented at the school and neither the school’s educational project nor the teachers in the programme had experience in bilingual education. However, in Y3rd ESO there was the mentioned increase of 0,33 points in the results, as the school had a stable qualified teaching staff and began to engage in bilingual innovation projects, which supports this improvement.

The standard deviation indicates the spread of data around the mean, and in this case, there a slight difference between Y1st and Y3rd scores in Las Encinas and Los Pinos (0.09 and 0.06 respectively), while in Los Alamos the difference is greater (almost o.17 points). The mode shows a higher score in Las Encinas (2.8) and Los Alamos (2.2), whereas in Los Pinos there is a clear difference within the group between Y1st ESO (mode 1.3) and Y3rd ESO (mode 2.3), which supports the observations concerning the mean.

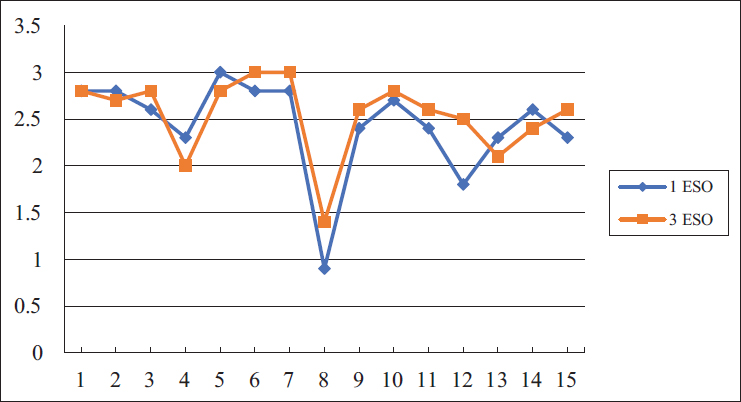

Regarding the individual results, in Las Encinas most of the students increased their scores on the test, with the exception of four students (LE2, LE4, LE13 and LE14), although the decrease was minimal (0.2 points on average). Even the student who obtained the lowest score in Y1st ESO (LE8 0.9 points) scored 0.5 points higher in Y3rd ESO (Graph I).

GRAPH I. Evolution of tests results at Las Encinas School between Y1st and Y3rd ESO

Source: Compiled by the author based on data.

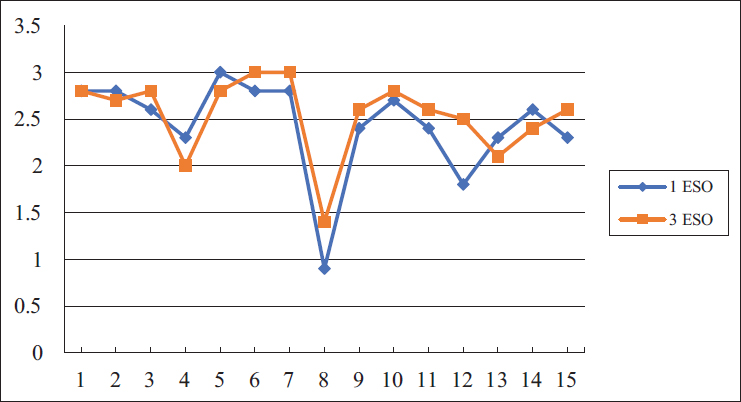

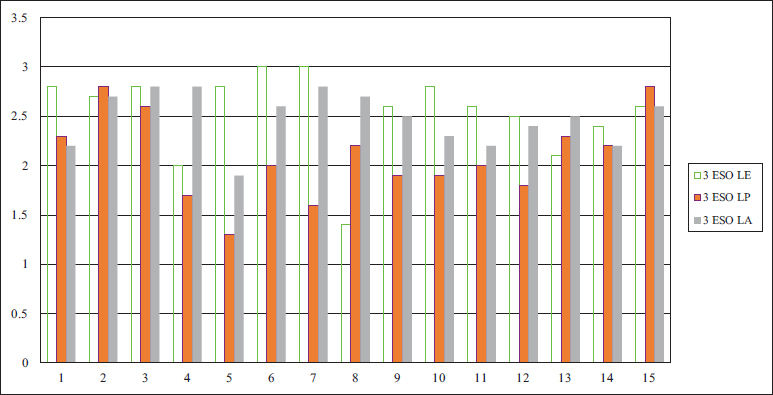

In Los Álamos School, a similar trend of improvement or maintenance of results from Y1st and Y3rd ESO is observed. However, there are two students, LA6 and LA13 whose scores decreased by 0.4 points between the two tests. It is worth noting that this decrease is not significant since the starting grade for both was already high: 2.9 out of 3 in the initial test in Y1ESO (Graph II).

GRAPH II. Evolution of tests results at Los Alamos School between Y1st and Y3rd ESO

Source: Compiled by the author based on data.

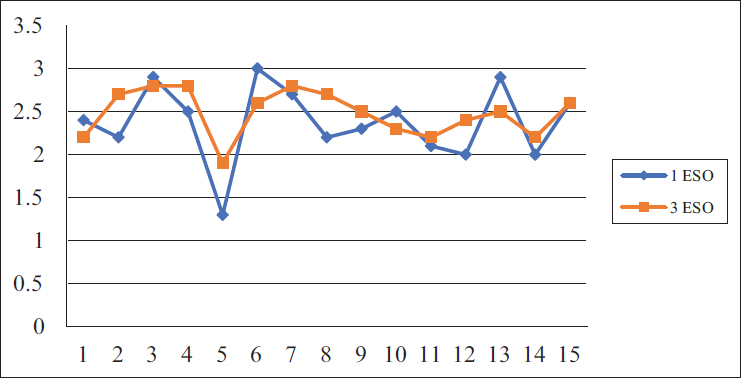

It is in Los Pinos school where we find the largest difference in results between Y1st and Y3rd ESO. The scores improved by an average of 0.33 points between the first test and the second, with the most significant improvement being that of student LP10, who scored 1.1 points higher in Y3rd than in Y1st ESO. Only three students have lower scores in the second test (LP4, LP5 and LP8), and their decline is not very significant, ranging from 0.1 and 0.2 points, starting from a mean of 1.8 in Y1st ESO. Therefore, this decline would be considered of little relevance (Graph III).

GRAPH III. Evolution of tests results at Los Pinos School between Y1st and Y3rd ESO

Source: Compiled by the author based on data.

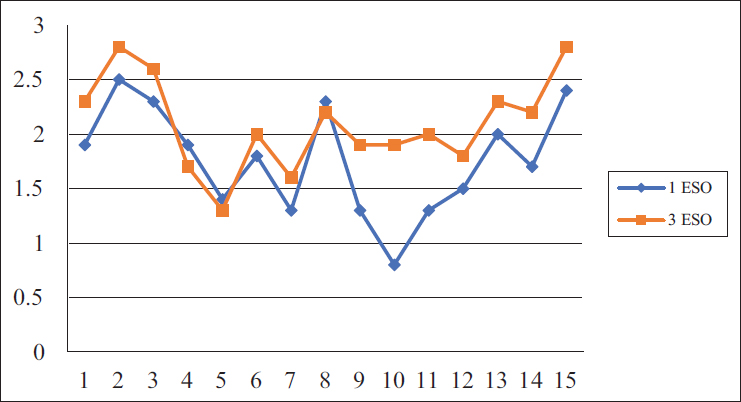

The comparison of data from the three schools contributes to explaining distinct aspects of the research (Ravid, 2005), such us observing contrasts within the region, since these are schools in different towns. Graphs IV and V show the previously mentioned trends. Starting from an initial situation (Y1st ESO), where only seven out of 45 students had results below the mean (1.5 points), the overall results of two of the schools already exceeded the mean: Las Encinas with 2.43 points and Los Álamos 2.37 points (Graph IV).

GRAPH IV. Comparison among the three participating schools in the first data collection (Y1st ESO)

Source: Compiled by the author based on data.

GRAPH V. Comparison among the three participating schools in the second data collection (Y3st ESO)

Source: Compiled by the author based on data.

In Y3rd ESO, students have been consistently learning new historical content and writing essays for two years as part of the bilingual programme, both in English language and in non-linguistic subjects with high theoretical content -such as social and natural sciencies-. Graph V illustrates this trend towards improved results. Only two out of the 45 students (LP5 and LE8) scored below what would be considered a passing mark (1.5 points), since the maximum score is 3 (Graph V).

Regarding the linguistic aspects that are included in the essays, it is necessary to point out a greater use of subordinate clauses in Y3rd ESO compared to the more commonly used coordinate clauses in Y1st ESO. In addition, the importance of using connectors in history text writing (Achugar & Schleppegrell, 2005), is extensively included in the H-CLIL rubrics concerning the writing style, addressing where, when, how and why the events took place. The use of connectors is more common in Y3rd ESO than in Y1st ESO tests. Similarly, the arbitrary use of tenses, such as the present tense (in the case of the campaign log in Y3rd ESO test), past tenses and historical present -always a challenge for students of history- is more prevalent in the texts written by Y1st than those written by Y3rd ESO. Below are excerpts from the essays of three students, one from each participating school, in Y1st and Y3rd ESO that illustrate the above:

LE11 – 1ºESO: “Christopher Columbus discovered America, but how? He was looking for another way to go to India. He thought the world was spherical. It was in August”.

LE11 – 3ºESO: “We are in Granada, the people runs in panic, some escape and the others stay without knowing what to do, we have entered the fortress and it’s done. The reconquest of centuries finish and we won”.

LP3 – 1ºESO: “Christopher Columbus goes to see if he could reach Asia from the other way. There it found America. San Salvador was the island he gets. He went in August and reach it in October”.

LP3 – 3ºESO: “I have arrived to the campaign where we are gonna stay tonight so we could attack the day after tomorrow. Today we are only preparing the weapons, so they are prepared for war and others are looking for a good place to attack (…) Even if it seems simple, it isn’t (…) What they [the governors responsible for the war] don’t know is that with all this fights, somehow, trade routes are closing”.

LA8 – 1ºESO: “Columbus crossed the Atlantic Ocean and he see a little bit of land. He and the navegants were so happy. First they see San Salvador. They went on Spain back and they told all the people that they saw other land out of Spain.

LA8 – 3ºESO: “Day 1. We reached Granada and start setting up the camps. Day 2. We are preparing the catapults and the assault towers. We also have shovels and pick axes to dig under the castle and make it collapse. Day 3. We started the siege, we have surround the castle”.

Misspelling was not taken into account as a penalty either in the evaluation criteria outlined in the rubric or in the marking. Strategies for writing in history in a foreign language prioritize the authenticity of the provided information, the transmission of knowledge, the correct sequencing of events, the clarity and coherence of the discourse over spelling (Ministry of Education-British Council, 2010). Even the SAT (Standard Attainment Tests), administered in Great Britain to students between the ages of 7 and 14, prioritize the development of discourse over spelling (Gov.UK, 2014).

Based on the results obtained, the null hypothesis is refuted, as the study illustrates that students exhibit a learning progression of historical content in line with the curriculum requirements in both academic levels, along with an improved written expression of the content in Y3rd ESO compared to Y1st ESO. Despite the limitations of this study, it can be inferred that students acquire the curricular content of history even when they learnt it in a foreign language. However, these findings should be taken cautiously, as it would be prudent to expand the sample and repeat the tests in several-year courses. Further research is needed, for example comparing the results with those of students at the same academic levels in non-bilingual schools, where the subject is learnt in their native language.

It seems obvious to assert that the most authentic assessment situation is in which teachers select the assessment method that is most similar to the tasks that have been carried out in the classroom. A fair assessment is important, both in languages and content subjects. A poor way of evaluating can lead to failure for students and, therefore, for schools. Formative assessment models that take into account the process that leads to learning and consider all the elements included in the learning -the language of schooling- may help teachers to adopt the most appropriate methodologies for their teaching practice.

The use of assessment results in bilingual education is a pivotal issue, as it underpins or impacts the programmes: what areas need to be improved and what would be essential to achieve success? How can these programmes be enhanced and how can teaching practices be promoted? This study aims to illustrate how an assessment approach that considers, not only the content but also the language, can contribute to supporting subject teachers to become aware of how evaluation influences their teaching and their students’ expression of the learning. Encouraging students to write what they learnt, especially nowadays, with open-ended questions goes beyond focusing on exams as the only form of standard evaluation. It is important to meaningfully analyze the teaching and learning processes and formatively assess students by involving them in the process, since the results obtained influence the adoption of significant educational decisions (Mahoney, 2017).

It is essential to critically examine the assessment process in CLIL. It seems logical to consider measuring the content in the language embedded, as would be done in L1. An interesting debate revolves around the percentage allocated to every item in the assessment criteria. This study suggests measurement methods appropriate to bilingual teaching. Additionally, it proposes opening paths to possible lines of research in which data collection could be expanded to other non-linguistic subjects. The study of the potential implications that the socioeconomic profile could have in their academic results would be an extremely interesting aspect to explore. Another promising and yet under-studied research direction links the learning of history with the alternated use that students make of the native and the foreign language in the classroom when they want to effectively communicate: translanguaging (Celic & Seltzer, 2013; Lasagabaster, 2013). Far from being an obstacle to students’ communication, the use of linguistic resources in two languages when expressing their knowledge of the subjects studied under the CLIL approach is an added value to bilingual education. Mahoney makes a controversial suggestion: “If the objective is to measure history knowledge, then assessment could be conducted in English, Spanish or a combination of both languages, which are meaningful to the students and can better show what students know (…) Failing to assess [them] also in their native language may mean ignoring relevant information about the teaching and learning process” (Mahoney, 2017: 11-12). During the research, some examples of translanguaging came up and the transmission of historical knowledge was achieved; there is also this example of metalanguage that a student included in his essay to explain the switching of languages to the reader:

LE10 – 1ºESO: “Then they put the objects in the carabela (this word is in Spanish) and they took gold and new products to Spain”.

Assessing in bilingual education entails recognizing and appreciating the resources, effort and time that teachers, students, families and public administrations have made for over 25 years. Eventually, it is all about enhancing education, particularly in the light of the current context when learning, including that of CLIL subjects, largely occurs in hybrid environments characterized by blended teaching, increased digitalization and online learning.

Achugar, M. and Schleppegrell, M. J. (2005). Beyond connectors: The construction of cause in history textbooks. Linguistics and Education, 16(3), 298–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2006.02.003

Anderson, L.W., & Krathwohl, D.R.(2021). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Ball, P., Kelly, K., & Clegg, J. (2015). Putting CLIL into Practice. Oxford Handbooks

Barbero, T. (2012). Assessment tools and practices in CLIL. In Quartavalle Franca (ed.) Assessment and Evaluation in CLIL. AECLIL-EACEA. Ibis Edition. http://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/promoitals/article/viewFile/2827/3030.

Bloom, B.S. (ed.), Engelhart, M.D., Furst, E.J., Hill, W.H., & Krathwohl, D.R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. David McKay.

BOE (2022). Real Decreto 217/2022, de 29 de marzo, por el que se establece la ordenación y las enseñanzas mínimas de la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2022/03/29/217/con

Celic, C. M., & Seltzer, K. (2013). Translanguaging: A CUNY-NYSIEB Guide for Educators.

Cercadillo, L. (2006). ‘Maybe they haven’t decided yet what is right’: English and Spanish perspectives on teaching historical significance. Teaching History, 125, p.6-9. The Historical Association.

Consejo de Europa. (2020). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume. Council of Europe Publishing. www.coe.int/lang-cefr

Counsell, C. (2000). Historical knowledge and historical skills: a distracting dichotomy, in Arthur, J., & Phillips, R. Issues in history teaching, Routledge.

Cubo Delgado, S., Martín Marín, B., and García Ramos, J.L. (coord.) (2011). Métodos de investigación y análisis de datos en ciencias sociales y de la salud. Pirámide Grupo Anaya.

Cuny-Nysieb. Cenoz, J., Genesee, F., & Gorter D. (2014). Critical Analysis of CLIL: Taking Stock and Looking Forward, Applied Linguistics 35 (3): 243-262. http://tacticasc.blogspot.com.es/2016/03/una-polemica-sin-resolver-el-futuro-de.html

Dalton-Puffer, Ch. (2013). A construct of cognitive discourse functions for conceptualizing content-language integration in CLIL and multilingual education. EuJAL 1(2), 216–253 DOI: 10.1515/eujal-2013-0011

De Oliveira, L.C. (2011). Knowing and Writing School History. The Language of Students’ Expository Writing and Teachers’ Expectations. Information Age Publishing.

Del Pozo, E. (2009). Portfolio: un paso más allá en CLIL. Prácticas en Educación Bilingüe y Plurilingüe, 1. Equipo Prácticas en Educación. Centro de Estudios Hispánicos de Castilla y León. http://practicaseneducacion.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=43&Itemid=69

Del Pozo, E. (2019). CLIL in the Secondary Classrooms: History Contents on the Move, en Tsuchiya, K. y Pérez-Murillo, M.D. (coord.) Content and Language Integrated Learning in Spanish and Japanese Contexts: Policy, Practice and Pedagogy. Palgrave MacMillan.

Del Pozo, E., & Llinares, A. (2021). Assessing students’ learning of history content in Spanish CLIL programmes: a content and language integrated perspective, en C. Hemmi, D. L. Banegas (eds.), International Perspectives on CLIL. International Perspectives on English Language Teaching. Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70095-9_3

Evnitskaya, N., & Dalton-Puffer, C. (2023) Cognitive discourse functions in CLIL classrooms: eliciting and analysing students’ oral categorizations in science and history. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 26(3). 311-330. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1804824

Gerns, P. (2023). Qualitative insights and a first evaluation tool for teaching with cognitive discourse function: "comparing" in the CLIL science classroom. Porta Linguarum, 40 (161-179). https://doi.org/10.30827/portalin.vi40.26619

González, O. L. P., Mora, A. M., Hernández, B. M. T., & Leal, E. J. G. (2015). Reflexiones conceptuales sobre la evaluación del aprendizaje. Didasc@lia: Didáctica y Educación, 6(4), 161-168.

Gov.UK (2014). The National Curriculum. https://www.gov.uk/national-curriculum

Hernández Sampieri, R., Fernández-Collado, C., and Baptista Lucio, P. (2010). Fundamentos de metodología de la investigación. McGraw Hill.

IBM Corp. (2020). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 27.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp.

Krathwohl, D.R. (2002). A Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy: An Overview, Theory Into Practice. Volume 41, Number 4, 212-218. College of Education, The Ohio State University.

Lasagabaster, D. (2013). The use of the L1 in CLIL classes: the teachers’ perspective. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning 6/2: 1-21. http://laclil.unisabana.edu.co/index.php/LACLIL/article/view/3148/pdf_1.

Llinares, A., Morton, T., & Whittaker, R. (2012). The roles of language in CLIL. Cambridge University Press.

LOMLOE, Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de diciembre, por la que se modifica la Ley Orgánica de Educación 2/2006 de 3 de mayo https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2020/12/29/3

López Pastor, V. M., & Pérez Pueyo, Á. (2017). Evaluación formativa y compartida en educación: experiencias de éxito en todas las etapas educativas. Grupo IFAHE.

Lorenzo, F. (2017). Historical literacy in bilingual settings: Cognitive academic language in CLIL history narratives. Linguistics and Education 37 (32-41). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2016.11.002

Mahoney, K. (2017). The Assessment of Emergent Bilinguals: Supporting English Language Learners. Multilingual Matters.

McLougling, A. (2021). How to write CLIL materials. Training course for ELT writers, 25. Amazon Digital Services.

Ministerio de Educación-British Council (2010). Programa de Educación Bilingüe en España. Presentación de los resultados de la evaluación independiente. MEC-BC

Newell, J., Dahm, K, & Newell, H. (2002). Rubric Development and Inter-Rater Reliability Issues in Assessing Learning Outcomes. Proceedings of the 2002 American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference & Exposition. American Society for Engineering Education.

Otto, A., & Estrada-Chichón, J.L. (2019). Towards an Understanding of CLIL in a European Context: Main Assessment Tools and the Role of Language in Content Subjects. CLIL Journal of Innovation and Research in Plurilingual and Pluricultural Education, 2(1), 31-42. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/clil.11

Pascual, I., & Basse, R. (2017). Assessment for Learning in CLIL classroom discourse, en Llinares, A. and Morton, T.(eds) Applied Linguistics Perspectives on CLIL. Language Learning & Language Teaching, 47. John Benjamins Publishing Co.

Ravid, R. (2005). Practical Statistics for Educators. University Press of America

Schleicher, A. (2014), Equity, Excellence and Inclusiveness in Education: Policy Lessons from Around the World, International Summit on the Teaching Profession, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264214033-en.

Wineburg (1996) ‘The Psychology of Learning and Teaching History.’ In D. C. Berliner and R. C. Calfee (eds) Handbook of Educational Psychology. 423-437. Simon & Schuster Macmillan.

Contact address: Elena del Pozo Manzano. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Departamento de Filología Inglesa. Calle Silvano, 154 – 28043 (Madrid, Spain). E-mail: elena.delpozo@madrid.org

(adapted from Del Pozo & Llinares, 2021)

ESSAY: Explain, providing as many details as possible, how the discovery of America took place. Use the words: Columbus, Asia, Earth, caravels, August, October and San Salvador (about 150 words). Up to 3 points

SCORE/CATEGORIES |

0.5 mark |

0.4 mark |

0.3 mark |

0.2 mark |

1. GENERAL FEATURES: Fluency |

-The student writes between 150 and 100 words. |

The student writes between 99 and 75 words. |

The student writes between 74 and 50 words. |

The student writes less than 50 words. |

2. FORMAL FEATURES: -Marking sentences using capital letters and full stops -Essay format -Verb tenses -Coherence -Textual cohesion |

-Coordinate and subordinate clauses. - Uses all formal features required. - Uses an essay format -Correct use of the past and/or historical present. -It follows a cohesive discourse. |

-Mainly coordinate clauses, poor tries on subordinates. -Uses formal features and essay format but not completely correct. -Past and present tenses (historical present may not be used correctly). -The essay is coherent but may not follow a chronological order. Cohesive discourse |

-Only coordinate clauses or just chunks of information. -Uses formal features but no essay format or the opposite. -Incorrect use of the past and/or present tenses. -The essay is mainly coherent but sometimes lacks cohesion. |

The student does not use formal features. |

3. REPORT 1 Who participated? What happened? |

-(WHO) The student mentions Columbus, the Catholic Monarchs, Americo Vespucci, name of caravels or other historical characters or elements involved in the discovery. -(WHAT) The student mentions correctly at least two details of the trip. |

-(WHO) The student mentions Columbus and the Catholic Monarchs (or other historical characters or elements involved in the discovery). -(WHAT) The student mentions one detail of the trip correctly. |

- (WHO) The student mentions Columbus or any of the Catholic Monarchs (or other historical characters or elements involved in the discovery). (WHAT) The student mentions one detail of the trip but it is wrong. |

The student neither mentions the participants nor what happened, or the answer is not consistent. |

4. REPORT 2 DESCRIBE Where did it happen? |

-(WHERE) The student correctly mentions the place of setting off (Castile, Spain), the place of landing (new land, America) and the presumed destination (Asia). |

-(WHERE) The student describes the trip; mentions some places but may miss one. |

-(WHERE) The student describes the trip. The student mentions places that may not be correct. |

The student does not follow the report features. The report is not consistent. |

5. REPORT 3 DESCRIBE When did it happen? |

-(WHEN) The student correctly mentions the date of setting off and the date of the discovery. -Time connectors |

-(WHEN) The student mentions dates but fails one. -Time connectors (some may be wrong). |

-(WHEN) The student mentions only one of the dates and may fail. -No time connectors used. |

The student does not follow mention any date. The report is not consistent. |

6. EXPLAIN DESCRIBE How did it happen? Why did it happen? |

-(HOW/WHY) The student explains how the expedition sailed, direction East/West and how the trip ended up. -Sequence cause or effect connectors are used. |

-(HOW/WHY) The student explains how the expedition sailed, just mentions correctly either East or West and how the trip ended up but one is incorrect. -Sequence cause or effect connectors are used. |

-(HOW/WHY) The student tells only either how the expedition sailed or how the trip ended up (but does not mention East or West). -No sequence cause or effect connectors are used. |

The student does not explain. The explanation is not consistent. |

ESSAY: Imagine you are one of the officers of the Christian army in the conquest of Granada. Write the daily campaign including every detail you can think of (about 150 words). Up to 3 points

SCORE/CATEGORIES |

0.5 mark |

0.4 mark |

0.3 mark |

0.2 mark |

1. GENERAL FEATURES: -Fluency |

-The student writes between 150 and 100 words. |

The student writes between 99 and 75 words. |

The student writes between 74 and 50 words. |

The student writes less than 50 words. |

2. FORMAL FEATURES: -Marking sentences using capital letters and full stops -Diary format -Verb tenses -Coherence -Textual cohesion |

-Coordinate and subordinate clauses. - Uses all formal features required. - Uses a diary format -Correct use of the verb tenses. -It follows a cohesive discourse |

-Mainly coordinate clauses, poor tries on subordinates. -Uses formal features and diary format but not completely correct. -Correct use of the verb tenses (may fail any). -The text is coherent but may not follow an order. Cohesive discourse. |

-Coordinate clauses or just chunks of information. -Uses formal features but no diary format or the opposite. -Incorrect use of the verb tenses. -The text is mainly coherent but sometimes lacks cohesion. |

The student does not follow formal features. |

3. REPORT 1 EXPLORE Who participated? What happened? |

-(WHO) The student names correctly the historical protagonists (allies and enemies) of the conquest. -(WHAT) The student narrates everyday life in the campaign (at least two historical items). |

-(WHO) The student names the protagonists of the conquest and may miss any. -(WHAT) The student narrates the life in the campaign. The narration is incomplete. |

(WHO) The student either names the protagonists of the conquest or (WHAT) narrates the life during the campaign. Part of the data may be incorrect. |

The student does not mention who participated, what happened or the answer is not consistent. |

4. REPORT 2 When did it happen? |

-(WHEN) The student mentions the date correctly or the century of the campaign or details of the period. -Time connectors/markers. |

-(WHEN) The student mentions time periods. The information is not complete. -Time connectors/markers (some may be wrong). |

-(WHEN) The student mentions either dates or just general time periods and may fail. -No time connectors/markers used. |

The student does not mention when it happened, or the answer is not consistent. |

5. REPORT 3 Where did it happen? |

-(WHERE) The student mentions the setting of the campaign correctly and refers to features of the site (castle, walls, river, mountain, forest, valley…). - Location connectors |

-(WHERE) The student mentions the setting of the campaign and refers to features of the site. The information is not complete. - Location connectors (some may be wrong) |

-(WHERE) The student either mentions the setting of the campaign or some features of the site. The student may fail some. -No location connectors used. |

The student does not locate the action, or the answer is not consistent. |

6. DESCRIBE EXPLAIN EXPLORE How did it happen? Why did it happen? |

-(HOW/WHY) The student explains how the campaign happened and how it ended up. -Sequence/cause/effect connectors are used. -(WHY) |

-(HOW/WHY) The student explains how the campaign happened and how it ended up. The information is incomplete. -Sequence/cause/effect connectors (some may be wrong) |

-(HOW/WHY) The student explains how the campaign happened or how it ended up. Part of the information may be wrong. -No sequence/cause/effect connectors used. |

The student does not explain. The explanation is not consistent. |