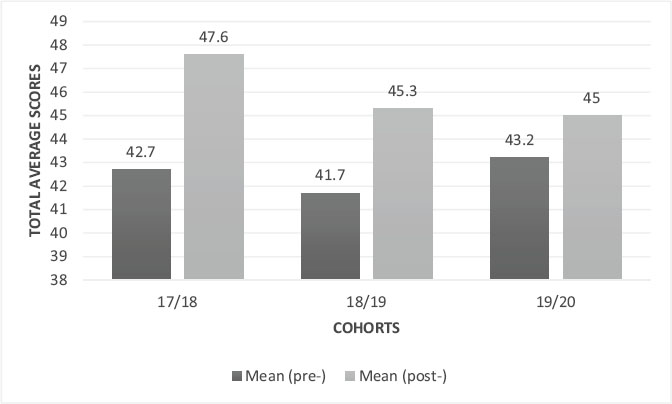

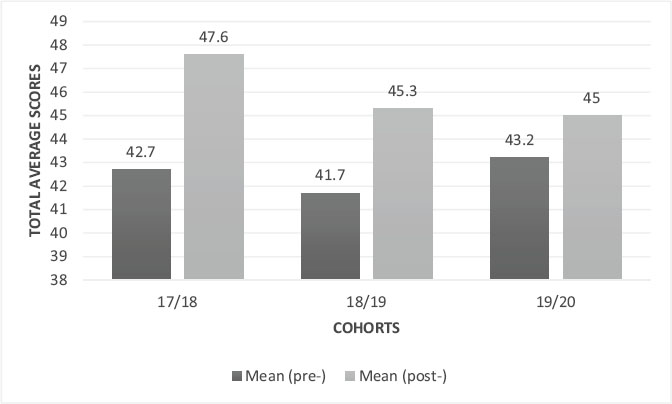

GRAPH I. Average scores for positive attitudes in pre- and post-questionnaires per year

Source: Compiled by authors.

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2024-403-606

Raquel Fernández-Fernández

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1858-2750

Universidad de Alcalá

Ana Virginia López-Fuentes

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2625-2201

Universidad de Zaragoza

Abstract

Literature has always been a valuable resource in English as a foreign language learning. However, recently published research (Duncan & Paran, 2017, 2018; Calafato & Paran, 2019) indicates the need to motivate future foreign language teachers to use it. To do that, they propose the inclusion of literary experiences in the teacher education curriculum as well as the promotion of positive experiences that help them be ready to use literary texts in their future bilingual classrooms. The present cross-sectional empirical study examines the impact of a 15-week pedagogical intervention on teacher education undergraduates’ attitudes towards the use of literature in the bilingual classroom. The intervention was based on the pedagogical principles of both the transactional theory (Rosenblatt, 1995,) and the dialogic theory (Flecha, 1997), which deal with literature as a complete educational resource. The participants were 37 undergraduates completing their degree in Primary Teacher Education with an EFL specialization and following a bilingual track. Data from three different cohorts (from 2017 to 2019) was collected using three data-gathering tools: a questionnaire based on Jones and Carter (2012), a written final reflection on the course, and focus-group meetings with each cohort. The information gathered was analysed using SPSS and NVivo statistical software. Results indicate that the intervention significantly increased students’ favourable attitudes towards the use of literature, especially in terms of considering literary texts a valid educational resource for teaching content as well as for working on misconceptions and misbeliefs. Participants also showed a high degree of confidence in their abilities both to use literature and to motivate their students to approach literary texts with ease.

Keywords: initial teacher education, bilingual teaching, literacy, language and literature teaching, classroom research.

Resumen

La literatura siempre ha sido un recurso valioso en el aprendizaje de idiomas adicionales. Sin embargo, algunas investigaciones publicadas recientemente (Duncan & Paran, 2017, 2018; Calafato & Paran, 2019) señalan la necesidad de motivar al profesorado de lenguas adicionales a utilizarla. Para ello, plantean incluir experiencias literarias en el currículo de formación del profesorado, así como promover experiencias positivas que les ayuden a estar preparados para utilizar textos literarios en sus futuras aulas bilingües. El presente estudio empírico transversal examina el impacto de una intervención pedagógica de 15 semanas en las actitudes del estudiantado de Magisterio hacia el uso de la literatura en el aula bilingüe. La intervención se basó en los principios pedagógicos transaccionales (Rosenblatt, 1995) y dialógicos (Flecha, 1997), que tratan de la literatura como un recurso educativo completo. Las personas participantes fueron 37 estudiantes universitarios del Grado de Magisterio en Educación Primaria con especialidad en lengua inglesa y cursando un itinerario bilingüe. Se recogieron datos de tres cohortes diferentes (de 2017 a 2019) utilizando tres herramientas de recogida de datos: un cuestionario basado en Jones y Carter (2012), una reflexión final escrita sobre el curso y reuniones de grupos focales con cada cohorte. La información recopilada fue analizada utilizando el software estadístico SPSS y NVivo. Los resultados indican que la intervención aumentó significativamente las actitudes favorables del estudiantado participante hacia el uso de la literatura, especialmente en su consideración de los textos literarios como un recurso educativo válido para la enseñanza bilingüe, así como para trabajar conceptos y creencias erróneas. Las personas participantes también mostraron un alto grado de confianza en sus habilidades para utilizar la literatura y motivar a sus futuros discentes a acercarse a los textos literarios fácilmente.

Palabras clave: formación inicial del profesorado, enseñanza bilingüe, alfabetización, didáctica de la lengua y la literatura, investigación en el aula.

Literary texts have proved to be a beneficial resource in the learning of additional language along decades (Maley, 1989; Collie & Slater, 1990; Hişmanoğlu, 2005; and Daskalovska & Dimova, 2012). However, the use of literature in bilingual contexts is still not a compulsory area in the teacher education curricula in Spain, and, when included, the pedagogical perspective taken isvery often centred on the study of literary texts rather than in their use in the classroom. Due to this, teachers are often ill-equipped, and seem unenthusiastic about using literary texts (Applegate & Applegate, 2004; Skaar et al, 2018). In this line, Calafato and Paran (2019) give a warning about the lack of reading habits and positive attitudes found in young EFL teachers, and advocate for a more explicit integration of literature into English language courses at university, especially those directed to pre-service teacher programs, based on enjoyable experiences around literature.

This study aims to measure the potential of a pedagogical approach to literature in promoting teacher education graduates’ positive attitudes towards its use. The approach, which combines dialogic and transactional practices, was delivered in the subject “Exploring Children’s Literature in English” over three consecutive academic years (2017-2018, 2018-2019, 2019-2020. Participants were Primary Education Teacher undergraduates in a bilingual track and completing an EFL teaching specialization.

This cross-sectional study collected both quantitative and qualitative information. Participants’ positive attitudes were measured through a questionnaire based on Jones and Carter (2012) before and after the intervention. Written reflection and focus groups were used to gather qualitative information on the specific types of positive attitudes triggered.

This contribution also addresses a research gap identified in previous studies, such as Shanahan, (1997), Carter (2007), Paran, (2008), and Duncan and Paran (2018), concerning the lack of empirical evidence of the impact of the use of literature on students’ educational development. To fill this gap, this study analyses and discusses mixed data collected along three courses to validate theoretical underpinnings. We hope that our conclusions will inform future research projects and classroom practice.

In the last decades, there has been a renewed interest in the role of literature in foreign language learning. The Common European Framework for Reference for Languages has recently incorporated literature as a resource to develop communicative dimensions, including mediation (CEFRL, 2020). Also, the Modern Language Association (MLA) suggested replacing the dualistic language-literature structure typical of higher education with a curriculum in which “language, culture, and literature are taught as a continuous whole” (2007, p. 3). Concerning bilingual education, its connection with the 4Cs (Communication, Cognition, Content and Culture) (Coyle et al., 2010) developed by the CLIL approach seems evident (Kramsch, 2013).

While literature is gaining momentum as a valid resource in the bilingual classroom, teacher undergraduates seem to be less prepared and less enthusiastic about its use. According to Calafato and Paran (2019), younger EFL teachers are less prone to use literature in their classes compared to more experienced teachers. The authors suggest that this lack of motivation towards literary texts may be balanced with the provision of positive experiences both at pre- and in-service stages. However, literature is not a compulsory component in many teacher education curricula, and when included, teacher educators often ignore how to design and implement a pedagogical approach that can favour those positive attitudes. In this line, Paran (2008) highlights some important elements that should be considered, such as:

Tak[ing] different aspects of the learner and the context of learning into account, looking at the whole person and the whole culture, in which literature is part of developing the whole person, and in which affective development and affective factors are taken into account. (p.15)

Also, and following Bobkina and Dominguez (2014), it seems convenient to “combine different approaches to enhance the use of literature as an effective tool” (p. 255). All this considered, we propose a constructivist approach to learning based on the creation of a student-centred, communicative and respectful learning environment. More specifically, the pedagogical intervention has two theoretical pillars: the transactional theory of reading (Rosenblatt, 1995, 2005), which defines what type of relationship between readers and text is considered, and what type of interaction is promoted in class, and, the dialogic learning theory (Freire, 1970, 2005), which explains the creation of a community of learners around literary texts and bring some specific strategies into play, such as the use of dialogic talks (Flecha, 1997). We consider these to be promising methodologies to increase students’ positive attitudes towards learning using literature, as they ensure students’ experiential learning, and create space for their voice and choice.

The transactional theory of reading, presented by Prof. Louise Rosenblatt in her book Literature as Exploration (1938) and developed until our times, was not designed for the teaching of additional languages. However, it serves to set up the type of interaction with the text we would like to promote in the classroom. Her philosophy about reading, very often wrongly classified as a reader-response theory, highlights the unique interaction between the reader and the text, which she considers to be ‘a transaction’. In this exchange, the reader and the texts modify each other, and each reading event is unique. She also argues that this private sphere of reading should be promoted in education together with a public sphere, where readers can share their reading experiences in a positive learning atmosphere. Rosenblatt believed that using literary texts in this environment would ultimately promote active democratic citizenship.

The dialogic theory, started by Brazilian pedagogue Paulo Freire (1970, 2005), is based on power of words and dialogue to transform students’ ways of seeing reality and the world. The presence of the dialogic theory in this study is more specifically found in the use of dialogic talks (Flecha, 1997). These talks promote the gathering of a group of people around a literary work. This instructional technique is developed in an environment of respect and tolerance. All the members of the community are invited to participate, and the experience is also open to people outside. Flecha (2015) also coined the term “dialogic reading” to define actions that take place in “numerous, diverse contexts at more times (during school hours and after school hours), in more spaces (from the classroom to the home and the street) and with more individuals (peers, friends, family members, teachers, neighbours, volunteers and other community members)” (pp. 39-40). These experiences consider the student’s interests and daily lives, generate new spaces of equality and trust as to achieve a better relationship between the students and the community.

With the help of transactional and dialogic components as the theoretical basis of the intervention, it is expected exert a positive influence in EFL teacher education undergraduates’ attitudes towards the use of literature in bilingual contexts. The learning environment created will also provide opportunities for discussion and reflection on the use of literature, thus encouraging metacognition as a core component of teaching professional development. In line with Bobkina and Domínguez (2014), we attempt to increase students’ awareness of the multiple dimensions literature can cover.

Recently published research on EFL teachers’ approaches to literature in their classrooms. is generally focused on secondary and higher education. In an upper-secondary setting, Bloemert et al. (2016) report on a 20-item Likert-scale survey administered to 106 Dutch EFL teachers, who used literature as a compulsory component in pre-university courses. Findings indicate that teachers’ practices differ greatly in the time devoted and in the methodology applied. The most influential factor in teachers’ practices is ‘curricular heritage’: teachers embrace the practices and curriculum that is developed in the school as soon as they arrive. Participants found a slight predominance of the context approach (focused on historical, social and cultural elements), but made a case for the importance of implementing a Comprehensive Approach to “enrich literature lessons as well as increase FL students’ understanding of contemporary literary prose” (p.184).

Duncan and Paran (2017) focused on the use of literature in the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme in the UK. The exploratory research sought to examine teachers’ views and practices with literature in the foreign language classroom through a mixed methods approach involving, a 118-item online survey, teacher interviews, student discussions and student focus groups, open student questionnaires, and lesson observations. Three school case studies participated in this study. Results indicate that teachers are in favour of using literature and are aware of its educational potential. The participants were confident in their ability to teach literature, and at many times considered that their own engagement and passion for reading was the success factor in their use in the classroom.

In a second study (Duncan and Paran, 2018), the authors aimed to discover the different ways in which teachers negotiate the challenge of teaching literature inside the IB Programme. They conclude that it is important to allow teachers to choose the literary texts that may fit better to their contexts, and comment on how teachers who are passionate about literature transfer this to their learners.

The attitudes towards literature of 12 EFL language teachers at the University of Central Lancashire was studied by Jones and Carter (2012). Authors argue that literature is an essential teaching-learning resource in the Common European Framework for Reference (CEFR, 2010), and, therefore, it is important to use literary texts to “appreciate literature”; but also “as a resource for developing language and cultural awareness” (p. 80). Results show that most teachers (75%) find literature useful classroom material and recognise its potential to develop cultural awareness (66.6%). However, they consider it contains many difficult cultural references and low-frequency language (66.6%), and half of the respondents believe that understanding literature is not what most learners need to do, especially advanced learners.

A more specific view on how age can be an influential variable in EFL teachers’ attitudes towards literature in EFL is offered by Calafato and Paran (2019). In their study, 140 Russian EFL teachers teaching at different levels completed an 85-item questionnaire. Their findings show that although they generally hold a positive view of literature in language teaching, the youngest group of participants (>30 years) uses literature to a statistically significantly lesser extent than the two older groups, and also report enjoying literature significantly less. The authors point to the need to enrich teacher education programmes (especially pre-service) with experiences that nurture a positive attitude towards the literary text.

Although studies on teacher undergraduates’ attitudes towards literature in bilingual classrooms are scarce, there are some recent contributions located in Spain. Férez-Mora and Coyle (2020) measured undergraduates’ beliefs before and after having used a lesson plan based on a poem in the EFL classroom. The data gathering tool was a 17-item Likert-type questionnaire covering three dimensions: linguistic, intercultural and motivational. Results indicate that students were more aware of the motivational and intercultural benefits of using poetry, but struggle to see their language learning potential.

This literature review indicates that teachers generally hold positive attitudes towards literature, and believe in the transferability of their passion for books. However, when coming to grips with literary texts in the classrooms, they report experiencing a lack of confidence and knowledge to use them appropriately. Most research published insists on the need to clarify the role of literature in the language classroom and to include courses on how to use literary texts as part of the teacher education curricula. Concerning methodological remarks, comprehensive approaches to literature, which explore its full educational potential, are generally fostered. Finally, most works highlight that it is urgent to enlarge the body of research to measure the impact of the use of literature empirically.

The present study is empirical, as it tests the impact of a given pedagogical intervention, collecting data before and after their administration. It is also cross-sectional, as it was conducted during three consecutive courses with different cohorts of students. Finally, it uses a mixed-method approach that facilitates the obtention of qualitative and quantitative information.

The present contribution aims to measure the impact of a pedagogical approach based on transactional and dialogic practices in improving students’ attitudes towards the use of literature in the bilingual classroom. Two hypotheses have been formulated:

H1: Experiencing this methodology increases teacher education undergraduates’ value and appreciation of literary texts as educational resources.

H2: Experiencing this methodology increases teacher education undergraduates’ motivation and readiness to use literary texts in the classroom.

Attending to these hypotheses, we can distinguish two main variables of the study, further subdivided as follows:

– Value and appreciation of literary texts as educational resources to learn content.

– Value and appreciation of literary texts to modify students’ thoughts and behaviour.

– Value and recognition of the role of different literary genres in learning.

– Recognition of the usefulness of literary texts at all levels, even with young learners.

– Perception of ability to motivate students to learn.

– Confidence in their ability to prepare lessons using literary texts.

– Perception of ability to integrate literature in the learning programme.

– Identification of literature as having a key role in their teaching practice.

– Recognition of skills to create classroom libraries.

Participants in this study are three different cohorts of students (N=37) distributed as follows: 14 (2017-2018), 10 (2018-2019), and 13 (2019-2020). Concerning age, 83.8% of the participants were between the ages of 21 to 25 years, while the rest were older than 25. With respect to their English level, all students had to present a B1 certificate to enter the bilingual itinerary. At the time of collecting data, in their fourth year in the degree, 73% of the participants possessed a B2 level of English (estimated or certified).

Taking as a reference the parameters stated by the PEW Research centre (2016), students show a medium-low reading habit in their mother tongue (Spanish), as 45.9% of participants claimed they read 1 to 4 books per year, and 40.5% read 5 to 10. Only 10.8% read from 10 to 20. When looking at their reading habit in English, figures are higher for the strand from 1 to 4 books (59.5%); however, there was a higher number of students reporting not reading any (32.4%), and just 8.1% read from 5 to 10 books.

Concerning the context of the study, this was a private university, Centro Universitario Cardenal Cisneros, administratively linked to a state university, Universidad de Alcalá (Madrid, Spain). The university offers bilingual itineraries for both the Infant and Primary Teacher Education Degrees. The bilingual track consists of more than 50% of the subjects delivered in the curricula in English, which means that subjects of different areas, such as Psychology, Pedagogy, Science, History or Arts, are delivered in English along the four years. Besides developing the well-known 4 Cs (Coyle et al., 2010): Communication, Content, Cognition and Culture, this specific bilingual project includes a fifth element, labelled as ‘connection’, which encourages students to approach learning considering affective factors (Fernández-Fernández and Johnson, 2016). The bilingual project also includes a strong metacognitive component that invites students to reflect on what they experience as learners and its application to the Primary classroom. It is also worth mentioning that this bilingual project was awarded the European Language Label (2016) by the European Commission through the Spanish Service of Internationalization of Education.

Participants of the study were all enrolled in a compulsory subject for the EFL specialization: “Exploring Children’s Literature in English”, which revolves around the use of children’s literature in EFL/CLIL contexts, thus experiencing the same pedagogical intervention. The subject was developed in 15 weeks in 150 hours (6 ECTS), which included the attendance to on-Campus sessions four hours per week over 15 weeks (60 hours total), reading texts, coordinating group work, preparing reading and writing assignments, and designing and creating materials and resources needed for the tasks proposed.

The study utilizes three different data-gathering tools. First, an attitudes questionnaire based on Jones and Carter’s (2012) (see appendix 1). The questionnaire was used both as a pre- and post-test. It contained a general information section that sought to find information about their age, level of English, and reading habits in English and Spanish. In a subsequent section, students are presented with 11 sentences and are required to share their level of agreement using a five-point scale from ‘I completely disagree’ to ‘I completely agree’. The original instrument was designed for EFL university lecturers. For this reason, some items were slightly modified to match the participants’ profile: EFL teacher education undergraduates in a bilingual itinerary. The final instrument was piloted with a small sample of students with a similar profile to participants who provided feedback on the improvement of the wording of some items. Also, one item was discarded from the original version, as it requested information about participants’ past experience with literature, and therefore, was not subject to variation in the pre- and post- measures.

The second instrument used was written testimonies. Students were asked to write a short text (no longer than a page) about how the subject had contributed to their learning and professional development. The task was suggested to students after final marks had been released. Students’ writings sometimes included evidence of their work, such as photographs of the materials they had created or links to activities they had developed over the 15 weeks.

The third instrument was a focus-group interview carried out by two external research team members, university professors, who had a one-hour meeting with volunteer students for each cohort. Focus group interviews were conducted asking students whether the experience had changed their attitude towards the use of literature, how this experience could impact their teaching practice and what elements of the experience could be changed to improve the intervention. Participants were also given room to share other opinions or views. Interviewers provided a summary of students’ responses and note down some literal sentences expressed by participants.

The data-gathering tools were administered in the same way to all three cohorts participating. The Likert-scale questionnaire was delivered in the first week of class in September/October. In December, participants could see their initial responses and change them using a different colour if they did not agree with them. Descriptive and bivariate analysis was performed using SPSS V.20.

Students’ written reflections on this learning experience were gathered in December, and focus groups were organised in January as a voluntary activity. All students participated. Qualitative data was entered in NVivo software. Transcriptions were coded independently by two researchers using the variables for this study as categories. The Kappa coefficient for inter-rater validity was 0.82, which is considered to be excellent (Landis & Koch, 1977). All statistical calculations were revised by a statistics technician external to the project.

All participants in the study signed a written consent document to allow the researchers to use the information gathered and disseminate results, provided that their identities were not disclosed. The data was securely stored in the university virtual drive, which was only accessible by the two researchers.

Participants were completing the subject “Exploring Children’s Literature in English”, which presents students with different literary materials for the CLIL/EFL classroom. The subject was delivered over 15 weeks, from September to January, using a transactional and dialogic methodology, as presented by Rosenblatt (1995, 2005) and Freire (1970, 2005), respectively. Students were invited to explore literary texts in a collaborative environment which encouraged discussion and critical thinking. They were taking different roles: as readers of these literary texts, as teachers who will use these texts in their future classrooms, and as writers, as creative writing was also promoted.

The contents of the subject included: storytelling, jazz chants, shape poems writing, drama activities (readers’ theatre, freeze frames, improvisation, preparing simple scripts), the analysis of nursery rhymes and fairy tales, and materials development. Also, students participated in dialogic talks once a week discussing a young adult work of literature. These talks were open to other members of the educational community. In all lessons students were asked to reflect on their experience and its potential impact on their future teaching practices.

Following dialogic principles, students were free to participate with their opinions and views. They were also invited to co-construct learning, contributing to the group with their knowledge and experience. In the same vein, the transactional theory highlights both the private and public spheres in reading, as students’ individual reading experiences are combined with group-sharing activities. In this meaning-making process, students use efferent and aesthetic stances, (Rosenblatt, 1995), to discover that reading literary texts requires skills other than retaining information, and that the use of representational language generates text layers that may be interpreted differently by readers.

In what follows, the results obtained through each of the data-gathering tools (attitude questionnaire, written reflections and focus groups) are discussed. Information gathered is described in relation to the variables included in this piece of research.

Regarding pre- and post- differences, results demonstrate that initial attitudes are already positive, as none of the criteria scored below 2.5 out of 5; however, in the post-test, these attitudes have increased, especially in the item “It is difficult to motivate students to read in English” (reverse coded), with a difference of 0.73, followed by “Using literature is a secondary goal for me” (reverse coded) increasing 0.7. The only exception is the item: “Using literature takes a lot of preparation”, with a slight decrease (-0.03). We can thus assert that attitudes after the intervention tend to be more positive.

Concerning the items participants agreed on the most, the highest average score in the post-test corresponds with “Literature can change students’ misbeliefs, misconceptions, prejudices, etc.” (4.86/5); followed by “Literature can help children understand content-subjects, such as Science or History” (4.81/5). Both items are related to the educational value of literary texts beyond language learning.

An analysis of the clusters of items associated with each of the variables of the study demonstrates an increase in both. The items associated with the first variable (“Participants’ value and appreciation of literary texts”) are items 2, 3, 7, 9 and 10, while items for variable 2 (“Participants’ motivation and readiness to use literary texts”) appear with an asterisk in Table I (items 1, 4, 5, 6, 8 and 11).

TABLE I. Attitudes questionnaire (Pre- and post-test results)

|

N |

Av. (Pre-test) |

Av. (Post-test) |

Av. Differences |

Dev. (Pre-test) |

Dev. (Post-test) |

1. I am ready to use literary texts using different resources, materials, techniques* |

37 |

4.16 |

4.76 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

0.49 |

2. Literature can be introduced in the classroom when students have an intermediate competence in the language. (Reverse coded) |

37 |

3.27 |

3.57 |

0.3 |

1.33 |

1.28 |

3. Literature can change students’ misbeliefs, misconceptions. prejudices. etc. |

37 |

4.51 |

4.86 |

0.35 |

0.61 |

0.35 |

4. Using literature takes a lot of preparation (Reverse coded)* |

37 |

2.54 |

2.51 |

-0.03 |

0.87 |

1.04 |

5. It is difficult to motivate students to read in a foreign language. (Reverse coded)* |

37 |

3.41 |

4.14 |

0.73 |

0.93 |

0.95 |

6. There is enough time in class to introduce literary texts.* |

37 |

3.22 |

3.32 |

0.11 |

0.95 |

1.16 |

7. Literary language is not useful for everyday communication. (Reverse coded) |

37 |

4.3 |

4.35 |

0.05 |

0.7 |

0.75 |

8. Creating a classroom library is very expensive and difficult. (Reverse coded)* |

37 |

4.41 |

4.59 |

0.19 |

0.72 |

0.72 |

9. I’d prefer not to use poetry in my English classes. (Reverse coded) |

37 |

4.46 |

4.65 |

0.19 |

0.65 |

0.63 |

10. Literature can help children understand content-subjects, such as Science or History. |

37 |

4.57 |

4.81 |

0.24 |

0.5 |

0.57 |

11. Using literature is a secondary goal for me. (Reversed coded)* |

37 |

3.81 |

4.51 |

0.7 |

1.08 |

0.9 |

Source: Compiled by authors.

When looking at the means for each of the clusters (see table II), results indicate that both variables increase in the post-test: (0.23 for variable 1, and 0.38 for variable 2). This reinforces the positive trend, although it indicates that there is a slightly higher increase in participants’ motivation and readiness to use literary texts. Despite these results, the highest total score in the post-test is related to students’ value and appreciation of literary texts. Total results demonstrate that students’ positive attitudes increase from 3.88 (pre-test) to 4.19 (post-test), thus showing a difference of 0.31.

TABLE II. Attitudes questionnaire (Pre- and post-test results). Clusters for variables

|

Average (pre-test) |

Average (post-test) |

Av. Differences |

Variable 1. Value and appreciation of literary texts (Items 2, 3, 7, 9 and 10 in table I) |

4.22 |

4.45 |

0.23 |

Variable 2. Motivation and readiness to use literary texts (Items 1, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 11 in table I) |

3.59 |

3.97 |

0.38 |

Total |

3.88 |

4.19 |

0.31 |

Source: Compiled by authors.

To check whether these differences are found to be statistically significant, it is necessary to conduct a paired samples t-test. To perform this, the sample was tested for normal distribution using a Kolmogórov-Smirnov test (Table III).

TABLE III. Kolmogórov-Smirnov test

|

Total (pre-test) |

Total (post-test) |

Cluster 1 (pre-test) |

Cluster 1 (post-test) |

Cluster 2 (pre-test) |

Cluster 2 (post-test) |

Z de Kolmogórov-Smirnov |

.706 |

.991 |

.655 |

1.046 |

1.171 |

.824 |

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.702 |

.279 |

.785 |

.224 |

.129 |

.505 |

Source: Compiled by authors.

Once the normal distribution of the sample for each of the variables of the study was confirmed, three t-tests were performed between the total results of pre- and post-tests, cluster 1 and cluster 2. In each of the three cases, the p-value was below 0.05, as it is shown in Table IV. These results indicate that there is a very small chance that the observed differences in means would have occurred by chance, therefore, we can reject the null hypothesis. In other words, the scores on the post-test are significantly higher than the scores on the pre-test for all three groups. This suggests that the intervention that was administered to the participants was effective in improving their scores.

TABLE IV. T-tests performed

|

t |

Sig. (2-tailed) |

Total pre-test- Total post-test |

-6.020 |

.000 |

Cluster 1 pre-test-Cluster 1 post-test |

-4.445 |

.000 |

Cluster 2 pre-test-Cluster 2 post-test |

-3.085 |

.004 |

Source: Compiled by authors.

The pedagogical intervention was also equally effective for each cohort (Graph I/Tabla V). The 2017/18 group increases 4.9, followed by the 2018/19 cohort with 3.6 and finally the cohort 19/20 increasing by 1.8. The increase in the three cohorts demonstrate a steady positive effect of the intervention in the three samples. It is also worth noting that the standard deviation in all cases decreases in the post-questionnaire, which may indicate that students’ attitudes tend to be more similar after the pedagogical intervention.

GRAPH I. Average scores for positive attitudes in pre- and post-questionnaires per year

Source: Compiled by authors.

TABLE V. Average scores for positive attitudes in pre- and post- questionnaires per year

|

N |

Mean (pre-) |

Mean (post-) |

Mean differences |

St. Dev (pre-) |

St. Dev. (post-) |

St. Dev difference |

17/18 |

14 |

42.7 |

47.6 |

4.9 |

3.4 |

2 |

-1.4 |

18/19 |

10 |

41.7 |

45.3 |

3.6 |

4.5 |

4 |

-0.5 |

19/20 |

13 |

43.2 |

45 |

1.8 |

4 |

2.9 |

-1.1 |

Source: Compiled by authors.

Although the quantitative results demonstrate a clear positive trend in participants’ attitudes after the implementation of the pedagogical intervention, it is necessary to complete these results with qualitative information obtained from written reflections and focus groups, as they may shed light to formulate valid conclusions.

Results from the 37 written reflections and the three focus groups will be presented together and in relation to the variables set for this study.

Variable 1: Participants’ value and appreciation of literary texts as educational resources.

Comments related to variable 1 are present in all the written reflections and all the focus groups conducted. When considering the sub-variables, ‘Recognition of the usefulness of literary texts at all levels, even with young learners’ shows the highest frequency (23 out of 37). 20 believe that the main reason for developing a negative attitude towards reading is that teachers do not choose interesting books or that students are not involved in choosing the texts. In the same line, 12 participants would prefer multicultural texts, and six would choose contemporary authors. Three students pointed out that the literary materials used in class ail to represent all children, thus hindering the development of their identities.

The most frequent subvariable ‘Value and appreciation of literary texts to modify students’ thoughts and behaviour’ is present in 25 reflections (67%). Teacher undergraduates indicate that shared reading impacts their knowledge, beliefs and actions. 23 reflections indicate that this practice allowed them to learn more “from the book and from my classmates” (ID 20).

Concerning ‘Value and appreciation of literary texts as educational resources to learn content’ students “generally agreed that literary texts can have a vital role in content-learning, but considered them as complementary material” (Focus group 2). In relation to ‘Value and recognition of the role of different literary genres in learning’, they mentioned that “it is difficult to enjoy poetry when we used to learn long epic poems by heart in our L1” (Focus group 3) and that “it may be a good idea to use literature in this way in the Spanish language classes” (Focus group 2). The transfer of practices between L1 and FL classrooms is also mentioned in 20 written reflections belonging to the three cohorts.

Variable 2: Participants’ motivation and readiness to use literary texts in the classroom.

54% of the written reflections are related to “Participants’ perception of ability to integrate literature in the learning programme”. More specifically, they feel confident to take literature into their classrooms, because they firmly believe it can be enjoyed. One comment that illustrates this idea states (ID 31): “I just can say that I have never enjoyed opening a book. Never. And now I’m very motivated towards books and reading in any language.” Other states that: “It is not just the book you choose, but how you present it to students to make the experience valuable. We have experienced this here.” (ID 20). In the transcripts of the focus groups this is also a common topic, as it appears in all three.

The subvariable ‘Confidence in their ability to prepare lessons using literary texts’ is present in 19 written reflections. 12 explicitly refer to the dialogic-transactional methodology used: “This is much better than an exam or work related to the book. Students can develop not only their English but also their critical thinking. Also, they can share their thoughts and predictions about the texts they read” (ID 29). In all focus groups participants shared their belief that what they had experienced could be transferred to their future classrooms.

Another frequent idea is the recognition of collaborative learning environments as a key pedagogical component, found in 10 written reflections and in all focus group conversations. One student refers to dialogic talks: “At the beginning I didn’t even read the texts. I confess, but when I listened to my classmates reflecting on them, I felt motivated to discover them myself and see what I could get from them. If I can motivate my pupils to share and discover, they will enjoy stories” (ID 8). Some of them consider that resorting to their classmates (and not the teacher) means they can learn from their peers, and that “everybody can have a role in the classroom and, by extension, in society” (ID 25).

Students also generally agree that the creation of a positive learning atmosphere is pivotal to developing positive attitudes towards literary texts in the English classroom. One states: “It is difficult to participate when the teacher is just looking at your grammar, or you need to provide the correct answer” (ID 20). In this sense, participants highlight the importance of being part of authentic activities promoting real communication and fostering respect and tolerance. One of the participants shares: “I was surprised to find out that I could share my views, even if they disagreed with what was expressed earlier, and my classmates tried to understand my point of view. I felt heard and respected in the dialogic talks” (ID 6).

Participants also referred to the difficulties met and how they faced them. Five writings mention that experiential activities were challenging at the beginning. Also, in the transcript for focus group 1 we can find that students share that “it was difficult for them to think about their experiences, and sometimes they did not know what to say. They believed that this problem was solved through practice. Once students shared their views, they knew how to join the discussion.” Language abilities seem to be another issue, as students in focus group 3 said that “most of the activities required advanced oral skills. They shared that they were shy to participate at the beginning. However, they highlight that the positive learning atmosphere encouraged them to participate and share their views without fear of making mistakes”. Therefore, students had to adapt to a new learning environment where they were required to think and be active.

Finally, a common finding in written reflections is that some students longed to have experienced literature in a more positive way during their Primary and Secondary education studies. One comment representing this view is the one offered by this student (ID 25), who says: “I wish I had enjoyed literature as a child and teenager as I have done with this course. I’m sure I’d have been a more avid reader now. But it is never too late. I’m happy I can now enjoy stories much more”.

Results show that the pedagogical intervention based on transactional and dialogic techniques improved students’ attitudes towards the use of literature in the three cohorts. Results are in line with Férez Mora and Coyle (2020), who recognised the positive impact of an experience with teacher undergraduates using poetry and recognize that it “amplified their identity systems as learners to a great extent” (p. 242).

The responses to the pre-test questionnaire show an initial positive attitude towards the use of literature. These results chime with previous exploratory studies in different countries, such as Jones and Carter (2012), Bloemert et al. (2016), or Duncan and Paran (2017). Although with caution as the attitudes of in-service teachers were not gathered, this may also indicate that this sample does not follow the trend indicated by Calafato and Paran (2019), which highlighted that younger undergraduates had fewer positive attitudes.

Data also indicates that the pedagogical intervention enhanced participants’ confidence in their use of literature in the classroom, not only for language learning, but as an educational tool, promoting ‘a passion for books’ (Duncan and Paran, 2017). They increased their attitude towards their skills to motivate students to read literary texts using the techniques used in the intervention. This transferability may feed their teaching practices in the future.

Results in the post-test demonstrate that the highest scores belong to students’ recognition of literary texts as useful resources to deliver content and change readers’ prejudices and misbeliefs. The latter being a predominant area in the qualitative data gathered. This holistic consideration of the benefits literary texts may bring into the classroom are in line with Bloemert et al.’s (2016) wish to implement a Comprehensive Approach to the teaching of literature. The transactional and dialogic strategies used in the pedagogical intervention of this study promote a more holistic view of the potential of literature in education, also considering it a springboard to discuss ideas with others, and to reflect on their own.

One common element in participants’ contributions is their recognition of the value of a learning environment where cooperation and sharing were natural, as proposed by Rosenblatt (1995, 2005) and Flecha (1997, 2015). Many comments refer to the use of dialogic talks. These findings chime with previous studies focused on this instructional strategy, (Alonso et al., 2008; Chocarro de Luis, 2013; Fernández-Fernández, 2020). Participants’ comments also indicate that their pasts experience with literature was developed in a much more controlled learning atmosphere. This can lead us to consider whether this use of literary texts deprives them of their very own nature: to be read and experienced.

Participants refer to the choice of texts as a predominant area. They refer to the use of predetermined reading lists of canonical authors or works, often in an adapted version. The lack of voice and choice draws education apart from student-centred learning environments. These results go in line with Duncan and Paran (2018) claim that indicates that teachers should be given the opportunity to select those texts they find more appropriate for their students.

Finally, a good number of participants blame past experiences with literature in the L1 classroom for their difficulties in approaching literature in the FL classroom. Therefore, the methodologies of teaching literature in L1 classes could require an urgent shift towards a more collaborative and reflective approach. Also, the connections between L1 and FL past experiences with literature may require further investigation, and classroom practices in both areas would need to be better aligned at all educational level.

It is important to acknowledge certain limitations of this study. Even if the sample encompasses the whole population available, the number of participants is low, and cannot be said to represent the whole population of EFL teacher education undergraduates. Concerning data gathering, the use of pre-questionnaires completed by participants as post-questionnaires could bias results, as they could see their initial responses. Finally, the focus groups transcripts have been limited to summaries provided by the interviewers, as they could not be recorded at the time of the experiment.

In the present study three different cohorts of teacher undergraduates (N=37) completing their EFL specialization and a bilingual track experienced a 15-week pedagogical intervention based on transactional and dialogic strategies. The evolution of their attitudes towards literature was measured through a questionnaire, written reflections and focus groups.

The findings indicate that there is a statistically significant improvement in their attitudes, present in the two variables studied: participants’ motivation and readiness to use literary texts in the classroom, and their value and appreciation of literary texts as educational resources. It may be stated that teacher education undergraduates are now more motivated to read and to use literary texts in English in their future bilingual classrooms. They more specifically recognize the role of literary texts to teach content and to change students’ beliefs.

The study has identified several success factors in the use of literary texts in bilingual teacher education programmes, such as the creation of a positive learning atmosphere, the promotion of collaborative learning, and the use of dialogic talks to share and comment their reading experiences. Also, students indicate that the choice of texts has been pivotal in letting them explore literary texts of their interest and taste.

Concerning future lines of research, this study could be replicated with in-service bilingual teachers to compare their attitudes towards literature. To do this, however, it would be advisable to design a new attitudes questionnaire which can cover highlighted areas, such as the connection between L1-FL, book choice or the use of collaborative learning spaces. Also, it would be interesting to measure the attitudes of the participants of this study after a few years of teaching practice. All in all, it is our hope that these transactional and dialogic learning experiences will inspire the, to design positive learning experiences around literary texts in their bilingual classrooms.

Alonso, M.J., Arandia, M., & Loza, M. (2008). La tertulia como estrategia metodológica en la formación continua: avanzando en las dinámicas dialógicas. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 11 (1), 71–77. http://www.aufop.com/aufop/uploaded_files/articulos/1240860668.pdf

Applegate, A. J., & Applegate, M. D. (2004). The Peter Effect: Reading habits and attitudes of preservice teachers. The Reading Teacher, 57(6), 554e563.

Bloemert, J.; Jansen, E., & van de Grift, W. (2016). Exploring EFL literature approaches in Dutch secondary education. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 29, 2, 169–188, https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2015.1136324

Bobkina, J., & Domínguez Romero, E. (2014). The use of literature and literary texts in the EFL classroom; between consensus and controversy. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English literature, 3 (2), 248–260. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.3n.2p.248

Calafato, R., & Paran, A. (2019). Age as a factor in Russian EFL teacher attitudes towards literature in language education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 79, 28–37.

Carter, R (2007). Literature and language teaching 1986-2006: a review. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 17 (1), 3–13.

Chocarro de Luis, E. (2013). Las tertulias dialógicas, un recurso didáctico en la formación de docentes. Historia y Comunicación Social, 13, 219–229. https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/HICS/article/viewFile/44238/41800

Collie, J., & Slater, S. (1990). Literature in the Language Classroom: A Resource Book of Ideas and Activities. Cambridge University Press.

Common European Framework of References for Languages (2010). Retrieved from https://www.coe.int/T/dg4/Linguistic/Source/Framework_EN.pdf

Council of Europe (2020). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume. Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg. Available at http://www.coe.int/lang-cefr.

Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge University Press.

Daskalovska, N, & Dimova, V. (2012). Why should literature be used in the language classroom? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 1182–1186

Duncan, S., & Paran, A. (2017). The effectiveness of literature on acquisition of language skills and intercultural understanding in the high school context. A research report for the International Baccalaureate Organisation. Institute of Education, University College London. literature-lanquage-acquisition-summary-en-2.pdf (ibo.org)

Duncan, S., & Paran, A. (2018). Negotiating the Challenges of Reading Literature: Teachers Reporting on their Practice. In: Bland, J, (ed.) Using Literature in English Language Education: Challenging Reading for 8–18 Year Olds. (pp. 243–260). Bloomsbury.

Férez, P., & Coyle, Y. (2020). Poetry for EFL: Exploring Change in Undergraduate Students’ Perceptions. Porta Linguarum, 33, 231–247.

Fernández-Fernández, R. (2020). Using Dialogic Talks in EFL Primary Teacher Education: An Experience. Revista Nebrija de Lingüística Aplicada a la Enseñanza de Lenguas, 14(29), 148–159. https://doi.org/10.26378/rnlael1429367

Fernández-Fernández, R., & Johnson, M. (2016) (cords.). Bilingual education at the university level. Centro Universitario Cardenal Cisneros. https://www.cardenalcisneros.es/sites/default/files/CC%20-%20Bilingual%20Education%20at%20the%20University%20Level_1.pdf?

Flecha-García, R. (1997). Compartiendo palabras. El aprendizaje de las personas adultas a través del diálogo. Paidós.

Flecha-García, R. (2015). Successful educational actions for inclusion and social cohesion in Europe. Springer.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin.

Freire, P. (2005). Pedagogy of the oppressed. 30th Anniversary Edition. Continuum.

Hişmanoğlu, M. (2005). Teaching English through Literature. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 1(1), 53–66.

Jones. C., & Carter. R. (2012). Literature and Language Awareness: Using Literature to Achieve CEFR Outcomes. Journal of Second Language Teaching and Research, 1(1), 69–82. https://doi.org/10.5420/jsltr.01.01.3320

Kramsch, C. (2013). Culture in Foreign Language Teaching. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 1(1), 57–78.

Landis, J.R., & Koch, G.G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174.

Maley, A. (1989). Down from the pedestal: Literature as resource. In R. Carter, R. Walker & C. Brumfit (eds.), Literature and the learner: methodological approaches. (pp. 1–9). Modern English Publications and the British Counsel.

Modern Language Association (MLA). (2007). Foreign Languages and Higher Education: New Structures for a Changed World. https://www.mla.org/Resources/Guidelines-and-Data/Reports-and-Professional-Guidelines/Foreign-Languages-and-Higher-Education-New-Structures-for-a-Changed-World

Paran, A. (2008) The role of literature in instructed foreign language learning and teaching: an evidence-based survey. Language Teaching, 41(04), 465 – 496. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026144480800520X

Pew Research Center, September 2016, “Book Reading 2016”. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/wpcontent/uploads/sites/9/2016/08/PI_2016.09.01_Book-Reading_FINAL.pdf

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1995). Literature as Exploration (2nd ed.). D. Appleton-Century Co. 5th Edition.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (2005). Making meaning with texts: selected essays. Heinemann.

Shanahan, D. (1997). Articulating the relationship between language, literature and culture: Toward a new agenda for foreign language teaching and research. Modern Language Journal, 81(2), 164–174.

Skaar, H., Elvebakk, L., & Nilssen, J. H. (2018). Literature in decline? Differences in pre-service and in-service primary school teachers' reading experiences. Teaching and Teacher Education, 69, 312e323.

Contact address: Raquel Fernández Fernández. Universidad de Alcalá, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras. Departamento de. Filología Moderna, Facultad de Filología (Caracciolos), c/Trinidad, 3, 28801 Alcalá de Henares (Madrid, España). E-mail: raquel.fernandez@uah.es

My name is:

DATE:

1. I am a:

□ Man

□ Wo man

2. My age is:

□ 21-25

□ 25-30

□ 30-35

□ +35

3. My level of English is:

□ Estimated

□ Certified

□ A2

□ B1

□ B2

□ C1

□ C2

4. I read literature in my mother tongue (if your mother tongue is not Spanish. indicate it here:_____________________)

□ None

□ 1-4 books per year

□ 5-10 books per year

□ 10-20 books per year

□ +20 books per year

5. I read literature in English:

□ None

□ 1-4 books per year

□ 5-10 books per year

□ 10-20 books per year

□ +20 books per year

6. If you don’t read literature in English. why don’t you do it?

□ I don’t have time

□ I find it difficult to understand because of the language level

□ I find it boring because of the topics

□ I don’t understand cultural issues

□ I don’t have the motivation to do it

□ I don’t know why

7. If you read literature in English. why do you do it?

□ For pleasure

□ As an assignment for my studies (University. E.O.I.,Language schools. etc.)

□ For any other reason. please state it here: _________________________________

With relation to CLIL Primary Education, indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

|

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Not Sure |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

1. I am ready to use literary texts using different resources. materials. techniques |

|

|

|

|

|

2. Literature can be introduced in the classroom when students have an intermediate competence in the language. |

|

|

|

|

|

3. Literature can change students’ misbeliefs. misconceptions. prejudices. etc. |

|

|

|

|

|

4. Using literature takes a lot of preparation |

|

|

|

|

|

5. It is difficult to motivate students to read in a foreign language. |

|

|

|

|

|

6. There is enough time in class to introduce literary texts |

|

|

|

|

|

7.Literary language is not useful for everyday communication |

|

|

|

|

|

8. Creating a classroom library is very expensive and difficult |

|

|

|

|

|

9. I’d prefer not to use poetry in my English classes |

|

|

|

|

|

10. Literature can help children understand content-subjects. such as Science or History |

|

|

|

|

|

11. Using literature is a secondary goal for me. |

|

|

|

|

|