FIGURE I. Ryan and Deci’s Taxonomy of Motivation (taken from Ryan and Deci, 2020)

Source: Compiled by the authors.

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2024-403-610

Ana Halbach

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3172-061X

Universidad de Alcalá

Manuel Aenlle

Universidad de Alcalá

Abstract

This article examines the effect of the application of the Literacy Approach, an approach to English language teaching developed in the context of CLIL programs, on student motivation. The Literacy Approach was implemented in the English lessons in year 5 (N=50) and 6 (N=36) of primary education in a medium-sized charter school with a CLIL program in a village in the north of Madrid. Motivation analyses were carried out using a mixed approach (quantitative and qualitative), studying this construct in various ways: firstly, studying motivation itself in a holistic view. Secondly, distinguishing between its extrinsic and intrinsic components. Lastly, focusing on how this construct evolves in special groups of learners: those with a higher level of English and those who struggle learning the language. Results seems to reflect a positive impact of the Literacy Approach on students’ motivation: an overall high level of motivation is seen throughout the academic year. The highest impact can be seen in the more internalized types of motivation, very much in line with what had been found for CLIL programs in an earlier research project. The increase in this more internalized motivation is especially noticeable in the weaker students in the group.

Keywords: Literacy Approach, ELT, primary education, motivation, CLIL.

Resumen

Este artículo examina el efecto de la implementación del Literacy Approach, un enfoque de enseñanza del inglés desarrollado en el contexto de los programas AICLE, sobre la motivación de los estudiantes. El Literacy Approach se implementó en las clases de inglés de 5º (N=50) y 6º (N=36) de primaria en un colegio concertado de tamaño medio con un programa AICLE en un pueblo del norte de la Comunidad de Madrid. El análisis de la motivación se llevó a cabo mediante un enfoque mixto (cuantitativo y cualitativo), estudiando este constructo de varias maneras: en primer lugar, centrándonos en la motivación en sí misma desde una perspectiva holística. En segundo lugar, distinguiendo entre sus componentes extrínsecos e intrínsecos. Por último, centrándonos en cómo evoluciona este constructo en grupos especiales de alumnos: los que tienen un mayor nivel de inglés y los que tienen dificultades para aprender el idioma. Los resultados parecen reflejar un impacto positivo del "Literacy Approach" en la motivación de los alumnos: se observa un alto nivel general de motivación a lo largo del curso académico. El mayor impacto se observa en los tipos de motivación más interiorizados, muy en línea con lo que se había encontrado para los programas AICLE en un proyecto de investigación anterior. El aumento de esta motivación de carácter más intrínseco es especialmente notable en los alumnos más flojos del grupo.

Palabras clave: Literacy Approach, enseñanza del inglés como lengua extranjera, educación primaria, motivación, AICLE.

For over two decades, CLIL programs have been implemented in many European countries and beyond, with good results in increasing students’ foreign language proficiency. However, beyond this expected, and rather obvious, effect on students’ language levels, the approach has also shown an impact on teaching methodology, especially in more traditional teaching contexts like Spain. Since the language of instruction in the content subjects is not the students’ mother tongue, CLIL requires teachers to put their students more clearly at the centre of their teaching (Madrid & Pérez Cañado, 2018) making sure that they scaffold their understanding while at the same time providing students with the linguistic tools necessary for their learning and interaction in class (Coyleet al., 2010). Interestingly, and despite the fact that the foreign language is central for the decision to set up a CLIL program, foreign language teaching seems not to have been impacted by its implementation: foreign language lessons have stayed much the same and research has not focused on the effect students’ increased language skills have on them (Halbach, 2014). While the impact of CLIL on content-subject teaching is most obvious, leaving foreign language teaching out of the equation makes little sense since the students come to their foreign language classes with different needs, different expectations and a different motivation to those of their peers in monolingual schools.

This article reports on the results of the implementation of the Literacy Approach (Halbach, 2022), a new approach to teaching foreign languages developed in the context of CLIL programs to meet the specific needs of students for whom the foreign language is the door to learning in their content subjects. While the effect of the Literacy Approach was measured in relation to different aspects (reading skills, writing skills and motivation), here the focus is on the impact of the approach on students’ motivation throughout an entire academic year.

For students in CLIL programs, the foreign language is no longer just that, a “foreign” language. Rather, it is the tool that will allow them to access knowledge and to express their understandings in the content subjects, or, in other words, the tool that will make it possible for them to succeed academically. Even though the more hands-on, student-centred, language-sensitive methodology proposed to teach content subjects in a foreign language (Pérez Cañado, 2018) will go some way to bridge the language gap, it is vital that students have the chance to develop their communication strategies and understanding of the language.

Taking these needs as a starting point, and in line with other approaches that place literacy development at the heart of learning like Pluriliteracies Teaching for Deeper Learning (Coyle & Meyer, 2021) or Text-based Teaching (Mickan, 2012), the Literacy Approach, developed for language teaching in CLIL contexts, works on developing students’ ability to understand and skilfully produce a range of text types in different modes. Each unit will guide students to producing a specific type of text in a particular mode. By focusing on students’ output, the Literacy Approach uses a backward planning model, where determining the final outcome of a unit is the first step in the planning process. It is from this final product that the contents and the procedures are derived (Richards, 2013).

To learn about the specificities of the text type and its mode, students will use a model text as a starting point for their work. This model text is analysed at different levels, including a focus on the structure of the text and such specific features, as, for example, the use of image and music to support the message. Understanding of the input text at different levels paves the way for students’ own production, which is worked towards through a carefully sequenced learning path which assures the necessary understanding and practice for all students to successfully produce the final text. At the same time, the learning path guarantees that all the tasks done in class are meaningful for students, since they all converge in the final task. This means that students immediately see the usefulness of what they learn.

Making students aware of the specific characteristics of different text types and modes will increase their ability to both understand and produce texts as tools for meaning-making. In addition, working at the level of text allows language to be contextualized meaningfully and the different communicative skills to be integrated in a natural way as texts can be listened to, viewed or read, and identifying their characteristics will involve a great deal of discussion. Students don’t practice the communicative skills in isolation as “listening tasks”, for example, but do so because the work on the model text or on the production of their own text requires using them.

The Literacy Approach has been used in primary schools in Poland, Slovenia and Spain, and participating teachers have designed a number of units based on different types of text for different levels. While the results so far are very promising and teachers experience working with the Literacy Approach as challenging but satisfying, its effect had not been evaluated in any systematic fashion, neither as regards its learning outcomes nor how it impacts students’ motivation. The latter aspect is the focus of this article.

The implementation of CLIL programs has long been related to heightened levels of motivation. Starting with Seikkula-Leino’s (2007) study on motivation in Finland, studies by researchers in various European countries (Lasagabaster, 2011; Mede and Çinar, 2019; Navarro Pablo and García Jiménez, 2018; San Isidro and Lasagabaster, 2020; Shepherd and Ainsworth, 2017) have all proved this effect of CLIL.

However, a number of researchers have recently questioned whether the increased motivation that characterises students in CLIL programs can actually be attributed to the program (Dallinger et al., 2018; Mearns, et al., 2020; Rumlich, 2017). According to Rumlich (2017) the purported effect of CLIL may be due to the fact that only the best and most motivated students choose to become part of CLIL streams, so that rather than being an effect of the program, increased motivation may be an effect of the selection of students allowed to join CLIL programs.

In most contexts, the debate about whether motivation is the result of CLIL or a characteristic of CLIL learners prior to entering the program is difficult to resolve since most research lacks the necessary baseline data. However, with CLIL programs in the Madrid region, where this study takes place, becoming widespread and increasingly starting at age 3, students or parents are less likely to choose the CLIL program due to their higher motivation. In this sense, it is reasonable to assume that the results obtained in primary education schools in Madrid can be attributed to the special characteristics of CLIL.

Most of the research on motivation in CLIL is based on the use of questionnaires and compares CLIL students with similar groups of students in non-CLIL groups at a given moment in time. There are hardly any studies that look at the development of motivation within a group of students over time, with the notable exception of Lasagabaster and Doiz’s (2017) study which indicated that motivation in CLIL programs seems to vane over time, and San Isidro and Lasagabaster’s (2020) with the contrary result. This lack of data from longitudinal studies constitutes an important gap to be filled by research, especially since

[m]otivation is not stable but changes dynamically over time as a result of personal progress as well as multi-level interactions with environmental factors and other individual difference variables. It is therefore questionable how accurately a one-off examination (e.g. the administration of a questionnaire at a single point in time) can represent the motivational basis of a prolonged behavioural sequence such as L2 learning. (Dörnyei and Ushioda, 2021, p. 179)

Even though this multifaceted and dynamic nature of motivation makes establishing a cause-effect relationship difficult, Lasagabaster (2020) ventures to propose three main reasons for the positive impact of CLIL on motivation:

CLIL provides a cognitively challenging situation which is associated with a meaningful use of the foreign language and an improved sense of achievement. Secondly, CLIL seems to promote fruitful discussion on pedagogic issues and practices. And thirdly, it provides teachers and students with a sense of ownership of their teaching practice and the learning process (p. 16)

In line with the last aspect mentioned, ownership, Halbach and Iwaniec (2022) relate the higher levels of motivation found in CLIL programs to the fact that it caters for students’ basic needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness, as identified in Deci and Ryan’s (1985)self-determination theory. Thus, the fact that CLIL seems to cover these fundamental needs allows students to identify with the teaching goals of bilingual education in a different way than is typical in monolingual teaching (Buckingham, et al., 2022), and thus to “own” them.

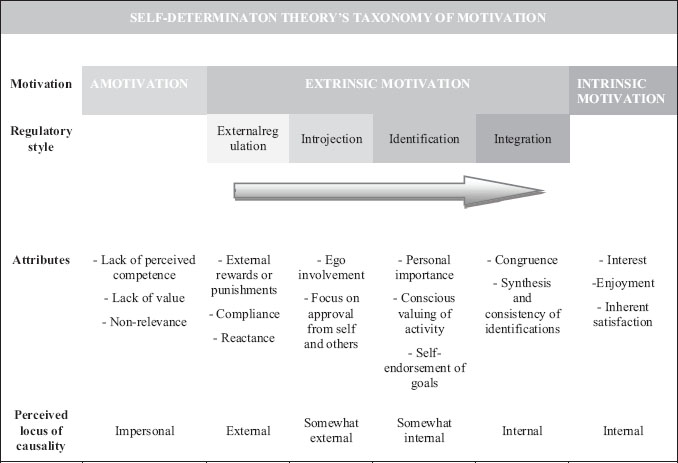

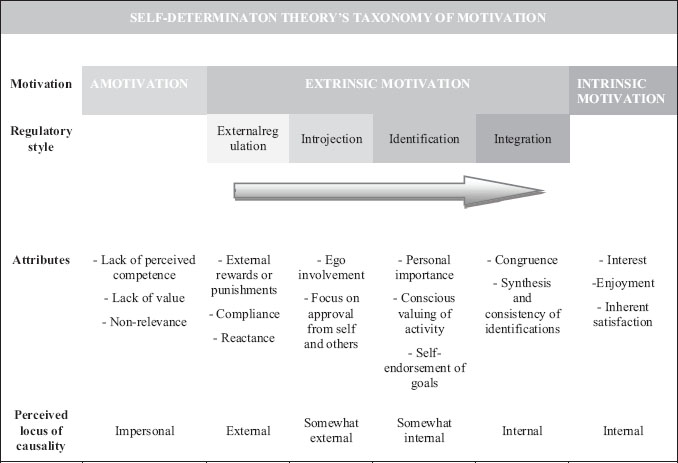

This identification with the teaching goals of a program is further explained by Ryan and Deci’s (2020) continuum of extrinsic forms of motivation where the more the student internalizes the teaching goals, the weaker the effect of external control and the more self-regulated the students’ motivation becomes (see figure I).

FIGURE I. Ryan and Deci’s Taxonomy of Motivation (taken from Ryan and Deci, 2020)

Source: Compiled by the authors.

It remains to be seen whether the Literacy Approach, as an approach to teaching English in CLIL contexts, can have a similar effect on students to that observed in the CLIL programs themselves.

During the academic year 2021-2022, the Literacy Approach was implemented in the English lessons in year 5 (N=50) and 6 (N=36) of primary education in a medium-sized charter school with a CLIL program in a village in the north of Madrid. Both year groups were divided into two groups (A and B) which were taught by the same teacher. The teacher in charge of year 5 had received some training in the Literacy Approach through participation in an Erasmus+ Project on the topic and had had some prior experience with it, while the teacher in year 6 was new to the approach. Both teachers were participating in an in-house professional development seminar on the Literacy Approach during the academic year. Students in year 5 had already been taught using the Literacy Approach in year 4, while for year 6 students this way of teaching English was completely new.

The main question guiding the overall research project was “What is the effect of using a Literacy Approach for teaching English in a primary school with a CLIL project?”, and, as mentioned above, this question was broken down to focus on different aspects related to students’ learning and their motivation. In this article the focus is on the latter, and thus the research questions is:

RQ: How does using the Literacy Approach to learn English impact students’ motivation?

Based on previous informal evaluations of the effect of the approach and on the review of prior studies on motivation, and specifically motivation in CLIL programs, we formulated the following hypotheses:

H1: the motivation of students exposed to the Literacy Approach will be high throughout the academic year

H2: there will be a transformation of students' primary motivators over the course of the year, showing an increase in their Intrinsic motivation according to Ryan and Deci’s (2020) taxonomy

H3: motivation will depend on the language learning ability of the students, with greater growth in the group of more advantaged students compared to those with greater learning difficulties.

This research has been approached from a descriptive observational point of view in which the evolution of students' motivation to study English through the Literacy Approach was investigated over the course of an academic year. The first two hypotheses of this study can be addressed from this observational perspective using a combination of quantitative and qualitative data. In the case of the last hypothesis, it has been addressed from a mixed design (cross-sectional and longitudinal) which compares the evolution of motivation in students who were classified by their teachers as generally “high performers” and “struggling students”. Five strong students and three weaker students were selected among the 50 students in grade 5. It was not possible to do the same analysis for year 6, as in this case students had not written their names on the questionnaires.

The instrument used for this research is a motivation questionnaire (see Appendix 1). It is divided into three parts, with the first measuring some demographic variables such as gender and age, but also issues related to language use in students’ lives such as the languages spoken at home or visits to English-speaking countries. The second part of the questionnaire, a five-point Likert-scale with 26 items, was taken from Doiz et al. (2014) and measured the constructs of instrumental and intrinsic motivation, motivational strength, anxiety, parental / family support and interest in foreign languages and cultures. Items k, r and v were reverse coded to avoid students’ mechanically choosing a given answer to the items. The final part of the questionnaire contained three open-ended questions asking what students liked best and least in their English lessons, and giving them the opportunity to add any further thoughts about their lessons. The questionnaire was piloted with a group of seven 1st year secondary students from the same school and, based on their feedback, adjustments were made to assure its clarity. The final questionnaire was completed by students in years 5 and 6 on three occasions at the start (October), middle (February) and end (May) of the academic year.

The first two parts of the questionnaires were coded and analysed with the help of SPSS version 27.0. During the analysis stage it was decided to eliminate the scales for anxiety and parental support as results did not yield any interesting information about motivation in the way addressed in this study. This is consistent with the results in Doiz et al. (2014) who found that the two student groups in their study (CLIL and non-CLIL) did not vary significantly in these two dimensions. Considering this, we finally had a tool composed of 4 sub-scales. Three of them were made up of 4 items, so they are on a 4-20 scale, while the "Motivational strength" scale was made up of 5 items. A weighting was performed to transform the “Motivational strength” scale into a 4-20 scale giving it the same weight as the rest of the aspects measured with each of the motivation scales. Thus, we have a 16-80 scale questionnaire which measures the general motivation of the students, and which is divided into 4 scales (4-20): "Intrinsic motivation", "Instrumental orientation", "Interest in foreign languages and cultures" and "Motivational strength".

To address the first two hypotheses, a descriptive analysis of the means obtained by the different groups of students in each of the variables of interest was carried out. For the study of the third hypothesis, a descriptive analysis of the same nature was carried out and, additionally, a 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures on one factor was applied in order to study whether differences observed in the evolution of the students' intrinsic motivation throughout the course were significant.

The open questions yielded a dataset of 8037 words (what I like most: 3504; what I like least: 2504; other: 2029), which was analysed using NVivo software for coding. A mixture of emic and etic processes was used to identify the themes, as the attributes of the different regulatory styles in Ryan and Deci’s taxonomy were used as a first set of codes (see Table I), which was then complemented with the themes emerging from reading the students’ answers. Thus, the different regulatory styles were related to the following themes:

TABLE I. Key words associated with the different regulatory styles

Regulatory style |

External regulation |

Introjection |

Identification |

Integration |

Intrinsic motivation |

Key words |

Marks Importance of English for their future |

What others think Self-awareness Shame |

Learning aims Identification with learning aims |

Personal importance of English |

Enjoyment of learning activities Satisfaction with learning achievements |

Locus of control |

External |

Somewhat external |

Somewhat internal |

Internal |

Internal |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

To evaluate students’ general motivation levels throughout the course, the results derived from the analysis of motivation in the 5th and 6th grade groups are presented separately, distinguishing between the different scales in questionnaire. The overall motivation as the sum of the scores obtained on the 4 scales was also calculated. The results obtained are shown in the Table II below.

TABLE II. Student’s motivation averages per year

Grade |

Motivation |

October |

February |

May |

Global |

5º |

Intrinsic motivation |

15.96 |

15.61 |

16.78 |

16.12 |

Instrumental orientation |

14.80 |

14.67 |

14.66 |

14.71 |

|

Interest in foreign languages and cultures |

17.00 |

17.24 |

17.04 |

17.09 |

|

Motivational strength |

14.92 |

14.83 |

14.95 |

14.90 |

|

Total |

62.68 |

62.35 |

63.43 |

62.82 |

|

6º |

Intrinsic motivation |

17.03 |

17.03 |

17.46 |

17.17 |

Instrumental orientation |

14.63 |

14.64 |

15.16 |

14.81 |

|

Interest in foreign languages and cultures |

17.58 |

17.61 |

18.03 |

17.74 |

|

Motivational strength |

15.75 |

15.52 |

15.50 |

15.59 |

|

Total |

64.99 |

64.80 |

66.15 |

65.31 |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

As we can see, the general motivation of the students throughout the course remains relatively stable with only very small increases between the three moments in which measurements were taken (October, February and May). The scores obtained in the 5th grade group are 62.68, 62.35 and 63.43 in October, February and May, respectively. The scores obtained in the 6th grade group were slightly higher, at 64.99, 64.80 and 65.31 in the same months. Bearing in mind that the scale that defines total motivation has a range of scores between 16 and 80, the general levels of motivation are very high.

If we analyze the results of the different scales of motivation in both groups, we find that in both cases, "Interest in foreign languages and cultures" is the scale that obtains the highest scores throughout the course (17.09 in the 5th grade and 17.74 in the 6th grade), while the scale of "Instrumental orientation" shows the lowest scores (14.71 in the 5th grade and 14.81 in the 6th grade), with a difference of almost 3 points between them. In the middle, we can see the scales for "Intrinsic motivation" and "Motivational strength" (see Table II).

As a result of the high levels of motivation seen in all the different scores, between 14.63 and 18.03 points on a 20-point scale, variations during the course are only very slight. Thus, in the 6th grade, we can observe slight increases in "Interest in foreign languages and cultures", "Instrumental orientation" and "Intrinsic motivation", although the variations observed are very modest, while “Motivational strength” remains stable. In year 5 we observe almost constant scores in "Motivational strength" and "Instrumental orientation" and "Interest in foreign languages and cultures", while at the same time there is a small increase in "Intrinsic motivation" at the end of the academic year.

Students’ responses to the open questions, confirm the high levels of motivation and highlight the strength of their more internally regulated and intrinsic motivation. For example, the concept of “mark” (nota or calificación) only appears twice in the whole dataset showing that the extrinsic motivator of rewards or punishment plays a very minor role for students. The other more extrinsic motivator of the importance of English for students’ future is a little more present in comments such as “we learn a lot of English for our future1” (year 6, October, what I like most), but there are no more than 5 mentions of the word “future” in the whole dataset and most of them come from the first set of questionnaires in October. This would coincide with the relatively lower scores given to “Instrumental motivation”.

Not surprisingly, given the age of students, self-awareness is a theme that occurs fairly often in their responses, especially in connection with speaking in front of the class, and this is an issue mentioned throughout the year by a small number of students who express their fear of “Having to speak in front of the class because I am afraid of making a mistake” (year 5, June) since “sometimes when you mispronounce a word they laugh at you, but not always” (year 6, June). However, for other students, speaking is among their preferred activities, even if they get nervous: “Even though I get nervous when I speak, I like it when we have to speak” (year 6, June, other). This comment is interesting because it shows how in this particular case the enjoyment of the activity (speaking) overrides the students’ self-consciousness and nervousness. For other students, speaking is a source of conflict not because of their self-consciousness, but because they feel they do not get enough chances to speak, as expressed in this student’s complaint: “That some classmates go on speaking and don’t allow me to speak” (year 5, October, what I like least).

A number of comments from students denote the identification with the learning goals of the subject, for example by valuing “that we do groupwork to understand the subject better” (year 6, February, what I like most), or mentioning that the Literacy Approach helps them learn much more than the methodology used in earlier years (“we learn much better in this way, at least I do” (year 6, June, what I like most). In general, the word stem “apren” (aprender, aprendemos, etc.) occurs 83 times in the question about what students like most, and 33 times in the space for other comments, and only 9 times in the question about what students like least. The negative comments are related mostly to taking exams, but also to aspects such as having to learn phrasal verbs. This awareness of their own learning and identification with the learning goals goes hand I hand with other comments where students express very personal learning goals such as “I like watching series and films about cars without subtitles and meet my favourite actors and to travel to Dallas, Houston and San Antonio and other places in the US” (year 5, October, other comments).

The identification with the subject’s learning goals is also related with the high level of “Interest in foreign languages and cultures” reflected in the quantitative data and supported by comments such as “I learn a language and I like learning many languages” (year 5, October, what I like most). However, when analysing the dataset as a whole, comments that mention learning languages as something positive and desirable are rare (only 3 comments in the whole dataset). It seems that the interest in learning languages is more related with learning English specifically: “I love learning English” (year 6, June, other comments). Finally, another token of internal regulation can be found in comments reflecting students’ satisfaction with their learning achievement: “Sometimes when I am speaking in English I feel as if I knew a lot” (year 6, February, what I like most), an awareness that is quite remarkable in students who are just entering adolescence.

However, by far the largest number of comments found in the open questions refer to the fact that students enjoy doing the tasks in their English lessons. This is the single most frequent comment, and the word stem “div” (divertido, divierto, etc.) appears 143 times in the data: “They are great fun, and I really like what we are dealing with” (year 5, May, what I like most). It is not only that classes and tasks are fun, but students also value that they involve a meaningful use of the language that is not restricted to learning it: “we go outside and do great unusual activities, even experiments with which we learn” (year 5, October, what I like most). Students derive pleasure and motivation from being able to use English, from learning the language and from the tasks they do in class.

In this sense, students also value teachers’ efforts to create these tasks and design their teaching materials: “I love the fact that teachers make an effort to create the books and that they are really cool and fun” (year 6, June, what I like most). They generally express their admiration for their teachers (85 positive comments throughout the academic year), especially year 6 students, who at age 11 could be expected to be more critical: “The teacher, because I never used to like English but the way my teacher teaches makes me love it because she plays games, treats us well and for me the most important thing is that she explains super-well and when you get home you have already learnt the contents” (year 6, October, what I like most). This effect does no wear off during the course, as might be expected when students get to know a teacher and become used to her methodology.

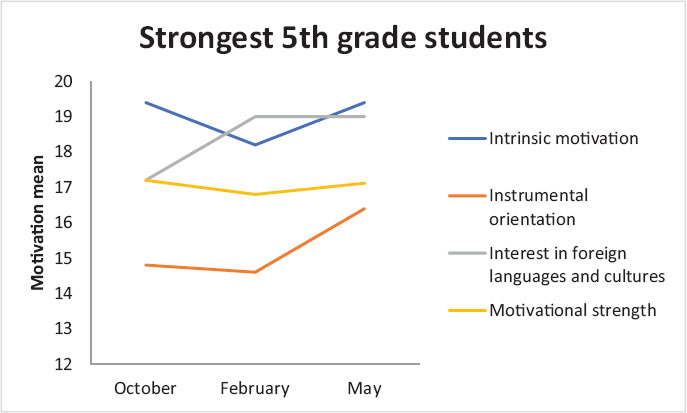

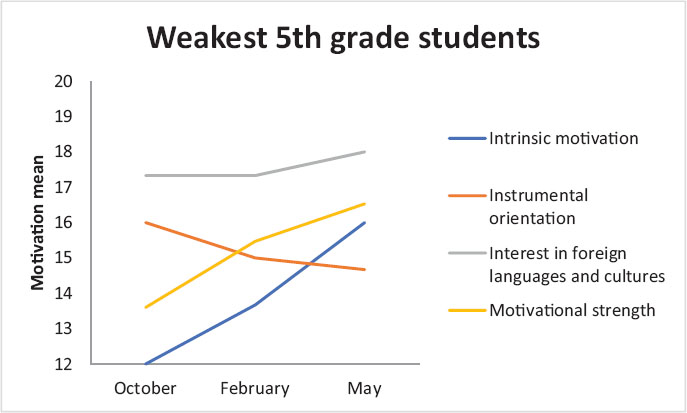

To look at the motivation in the two groups of more and less advanced students from year 5, the same measures as for the whole group were repeated, analysing the scores of the different motivational scales and the overall score of motivation at the three points in time where data were collected. Looking at the different types of motivation we can, once again, see very high levels in the case of the students with good abilities (14.80 to 19.40 on a scale of 20), and lower levels in the case of the low achievers (between 12.00 and 18.00). In fact, as can be seen in Table III, the average of the motivation scores of the weakest students are 61.87 compared to 69.70 in the group of the more advantaged students, showing a difference of almost 8 points. This difference is reduced slightly during the academic year, as the growth in motivation of the weaker students is 6.27, while in the case of the stronger students we see an increase of 3.32 points. More important than this slight difference in growth is the fact that overall motivation grows throughout the academic year, and that the two groups develop differently.

TABLE III. Average motivation of high and low achievers at the three points of measurement

Group |

Motivation |

October |

February |

May |

Global |

Strongest students (year 5) |

Intrinsic motivation |

19.40 |

18.20 |

19.40 |

18.87 |

Instrumental orientation |

14.80 |

14.60 |

16.40 |

15.27 |

|

Interest in foreign languages and cultures |

17.20 |

19.00 |

19.00 |

18.40 |

|

Motivational strength |

17.20 |

16.80 |

17.12 |

17.04 |

|

Total |

68.60 |

68.60 |

71.92 |

69.70 |

|

Weakest students (year 5) |

Intrinsic motivation |

12.00 |

13.67 |

16.00 |

13.89 |

Instrumental orientation |

16.00 |

15.00 |

14.67 |

15.22 |

|

Interest in foreign languages and cultures |

17.33 |

17.33 |

18.00 |

17.55 |

|

Motivational strength |

13.60 |

15.47 |

16.53 |

15.22 |

|

Total |

58.93 |

61.47 |

65.20 |

61.87 |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

The information contained in Table III shows the evolution of the scores on the different aspects of motivation measured over the course of the school year for the two groups of students selected. This evolution can be seen much more clearly in graphs I and II.

GRAPH I. Evolution of the motivation scales for 5th grade advanced students

Source: Compiled by the authors.

GRAPH II. Evolution of the motivation scales for 5th grade students with difficulties

Source: Compiled by the authors.

The graphs show a combination of almost level lines with others that show some changes over time. Thus, in the case of the stronger students, motivational strength and intrinsic motivation stay stable over time, while the other two scales show some slight positive variations (see Graph I). The first type of motivation that grows is students’ “Interest in foreign languages and cultures”. As was seen in the case of the whole group, this strengthened interest may be related to the nature of the tasks they do in their English lessons, which this group of students describes as “fun” and “interesting”. In fact, students appreciate “that we learn new things I didn’t know” (S, May, what I like most), which could refer both to the language or to the topics dealt with, as becomes visible in the analysis of the answers of the whole group.

Instrumental motivation also grows in the case of these stronger students from 14.80 points to 16.40 points, but only in the May questionnaire. This might be related to the external exam students were taking a few weeks after completing this last questionnaire, or to their greater concern about marks at this time of the academic year, as can be seen in this response to a May questionnaire: “I’d like to have more ‘extra tasks’ like last year so I can get a better grade” (S, May, what I like least).

The changes over time experienced in the weaker students’ motivation are slightly more complex as they show a relatively stable “Interest in foreign languages and cultures”, a decreasing “Instrumental motivation” (16.00 to 14.67) and very pronounced rises in “Motivational Strength” (13.60 to 16.53 points) and “Intrinsic motivation” (12.00 to 16.00 points; see Graph II).This increase of 4 points, while still small, is much higher than any other we have been able to observe in the study, and therefore merits further analysis. A 2-way ANOVA was performed and the results show significant differences in the 2 main effects (time, sig.=0.017; group, sig.=0.014) and in the interaction effect (sig.=0.023), which leads us to conclude that there are significant differences in the level of “Intrinsic Motivation” between the three moments at which data were collected (time factor), between both groups (group factor) and in the evolution of intrinsic motivation throughout the course (interaction effect). Looking at the open questions, we can find that for the weaker students the main motivator is fun, and they explicitly mention “games and songs” as positive. However, towards the end of the academic year, we can observe that these students also explicitly mention learning as something positive about the teaching approach: “That [the lessons] are very entertaining and I learn the same as with a textbook but having fun” (W, May, other comments). Learning is no longer related to fun only but also to achievement, thus aligning students’ perceptions with the aims of the subject.

Looking at the data collected through the questionnaire we find that, generally speaking, as was expected, students’ motivation in relation to their English lessons is very high. In the case of year 5 overall motivation scores remain stable throughout the year, while in year 6 there is a slight but steady increase. This is in consonance with studies that find that motivation in CLIL programs, and specifically motivation towards English in CLIL programs, tends to be high (Shepherd and Ainsworth, 2017). These high motivation levels are maintained throughout the course with slight variations if we look at the groups at large, and greater variations if we look at specific groups of students. This is somewhat counter-intuitive, as motivation is subject to the influence of a great number of factors, and therefore can be expected to vary over time (Lazarides and Raufelder, 2017). At the same time, it coincides with San Isidro and Lasagabaster's (2020) finding of sustained motivation over time in CLIL programs.

Motivation scores for year 6 are slightly higher than for year 5, which could be related to the novelty of the Literacy Approach for this group of students, but the fact that in this group scores also increase during the academic year seems to indicate that they are more than the result of the novelty of the Literacy Approach, as this would wear off over time. Students’ answers to the open questions in the questionnaire also stay similarly positive throughout the year, especially in relation to the tasks done in class and the teachers’ closeness, work and engagement. This seems to indicate that both the high levels and the slight increase of motivation shown in year 6 can be related to the effect of the Literacy Approach.

Variations in the scores of the different motivational scales during the academic year are too small to draw any conclusions, but looking at the overall scores we can see that in both groups “Motivational strength” and “Instrumental orientation” score below 16, while “Intrinsic motivation” and especially “Interest in foreign languages and cultures” obtain scores above 16. The two latter types of motivation could be placed at the more internally regulated end of Ryan and Deci’s (2020) taxonomy, thus confirming the second hypothesis that predicted the Literacy Approach to foster more intrinsic types of motivation. This is also reflected in students’ answers to the open questions in the questionnaire, particularly in their mention of activities as being fun and interesting. Given the characteristics of the Literacy Approach described above, we can also hypothesize that the high interest in foreign languages and cultures could be related to the use of different types of, mostly authentic, texts in different modes. This greater variety of texts not only gives students a more direct access to the culture, but also allows for different learning situations that include fun and interesting activities, and that make it possible to link the English language classes to the real world (“Doing unusual things such as trips or arts” year 5, October, what I like most). It seems that, as Lasagabaster (2020) argued for CLIL, the Literacy Approach allows for “the meaningful use of the foreign language and an improved sense of achievement” (p. 16). While in CLIL the meaningfulness of the language stems from the need to use it to learn the content subjects, in the Literacy Approach it comes from the contextualization of the study of language and the practice of the communicative skills on the path towards skilful production of texts with a clear focus on the success of all students.

This “inclusive” nature of the approach would then account for the performance of the motivation scales in the case of the more advantaged and weaker students studied. As was expected, the more advanced students showed higher levels of motivation, although contrary to our hypothesis, this group does not show a significant increase in their motivation levels throughout the course. The group that does show a significant increase, particularly in the levels of “Intrinsic motivation” is the weaker students. This is interesting, as it goes hand in hand with a decrease in instrumental motivation, as if these weaker students substituted the external motivators, for example the (bad) marks, for more internal ones, in this case the fun nature of the tasks or the feeling that they are capable of succeeding. In terms of the Literacy Approach, this evaluation of tasks as fun and leading to learning could be related with the meaningfulness resulting from the contextualization of all learning and practice within the Literacy Approach. It could also be the result of the orientation of the approach towards success, since the fact that planning occurs from the end of the teaching process, i.e. from the expected student production, and from there determines the contents and the procedures in the unit of work, makes it possible to equip all learners with the knowledge, understanding and skills they will need for the successful production of the final output. The open nature of this output, in turn, will allow all learners to perform at their level. Thus, both advanced and struggling students will get to the end of a teaching unit having produced a text they can be proud of. That on the way they have also improved their language skills is shown in the results obtained in the reading part of the evaluation project reported in Fernández-Fernández and Halbach (2023).

Going back to the controversy in CLIL whether increased motivation is the result or a condition for participation in the program, we can say, first of all, that in the case of the school in this research, participation in the CLIL program is not limited to the most able students. As regards the Literacy Approach itself, the data suggests that it is particularly motivating for the weaker students, whose intrinsic motivation scores show a greater improvement, and that, above all, it fosters a more integrative type of motivation. Given the higher cognitive demand that is inherent in learning new contents through a foreign language, developing an approach to ELT that motivates students at all levels of ability, promotes the growth of internal motivators and has a positive effect on students’ language levels will be particularly important precisely for these struggling students.

While the results of this study are promising, research in education is characterized by its messiness and dependence on a particular context. In this case, data collection on several occasions throughout a single academic year proved a challenge, thus leading to the loss of vital information such as year 6 students’ names. Furthermore, the school in which the study took place was led by a very determined management team that had clearly espoused literacy development as the way forward, so much so that the implementation of the Literacy Approach and its effect had been reported on in the local newspaper. All of these contextual variables may have had an impact on the results obtained. Nevertheless, taken together with the results obtained about the development of students’ reading skills (Fernández-Fernández and Halbach, 2023), the findings of this study seem to uncover a positive effect of the Literacy Approach. Hopefully other studies will follow that will allow us to further understand the impact of this approach to ELT.

Although not focused on CLIL programs as such, this article has evaluated the impact on students’ motivation of an approach to teaching foreign languages first developed in CLIL contexts, the Literacy Approach. Results seem to point towards a positive impact of the approach on students’ motivation, particularly on the more internalized types of motivation, very much in line with what had been found for CLIL programs in an earlier research project (Buckingham et al., 2022; Halbach and Iwaniec, 2022). Beyond this general effect, it was also possible to observe how it is particularly the students who are identified as struggling by their teachers who seem to develop this more internalized, intrinsic form of motivation, thus running counter to the claim of CLIL programs at large benefiting the most able and gifted students. On the other hand, while the effect of CLIL on motivation was related to the fact that it seems to cater for what Deci and Ryan (1985) described as the basic needs of mastery, autonomy and relatedness, it seems that in the case of the foreign language what the Literacy Approach fosters is mostly related with the pleasure derived from doing fun and interesting tasks that students perceive as relevant to learning. In the words of one of year 6 students “The method we are using is very interesting since we are always playing games and topics are dealt with that we don’t normally know about. I wish we would always be taught with this method” (year 6, May, others).

Buckingham, L., Fernández, M. & Halbach, A. (2022). Differences between CLIL and non-CLIL students: motivation, autonomy and identity. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development.

Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge University Press.

Coyle, D., & Meyer, O. (2021). Beyond CLIL. Cambridge University Press.

Dallinger, S., Jonkmann, K., & Hollm, J. (2018). Selectivity of content and language integrated learning programmes in German secondary schools. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(1), 93–104. doi:10.1080/13670050.2015.1130015

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behaviour. Plenum.

Doiz, A., Lasagabaster, D., & Sierra, J. M. (2014). CLIL and motivation: The effect of Individual and contextual variables. Language Learning Journal, 42, 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2014.889508

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2021). Teaching and researching motivation. Routledge.

Fernández-Fernández, R., Halbach, A. (2023). Giving ELT a Content of Its Own: How Focusing on Literacy Development Impacts Primary CLIL Students’ Reading Performance. English Teaching & Learning. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-023-00148-7

Halbach, A. (2014). Teaching (in) the foreign language in a CLIL context: Towards a new approach. In Breeze, R. et al. (eds.) Integration of theory and practice in CLIL. Amsterdam: Rodopi: 1–14.

Halbach, A. (2022). The Literacy Approach to teaching foreign languages. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Halbach, A. & Iwaniec, J. (2022). Responsible, competent and with a sense of belonging: an explanation for the purported levelling effect of CLIL. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(5), 1609–1623.

Lasagabaster, D. (2011). English achievement and student motivation in CLIL and EFL settings. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 5(1), 3–18. doi:10.1080/17501229.2010.519030

Lasagabaster, D. (2020). Motivation in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) research. The Palgrave Handbook of Motivation for Language Learning (pp. 347–366). Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-28380-3_17

Lasagabaster, D., & Doiz, A. (2017). A longitudinal study on the impact of CLIL on affective factors. Applied Linguistics, 38, 688–712. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amv059

Lazarides, R. and Raufelder, D. (2017). Longitudinal effects of student-perceived classroom support on motivation - a Latent Change model. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00417

Madrid, D., & Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2018). Innovations and challenges in attending to diversity through CLIL. Theory Into Practice, 57(3): 241–249.

Mearns, T., de Graaff, R., & Coyle, D. (2020). Motivation for or from bilingual education? A comparative study of learner views in the Netherlands. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23(6), 724–737. doi:10.1080/13670050.2017.1405906

Mede, E., & Çinar, S. (2019). Implementation of content and language integrated learning and its effects on student motivation. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning, 11(2), 215–235. doi:10.5294/laclil.2018.11.2.3

Mickan, P. (2012) Language Curriculum Design and Socialization. Multilingual Matters.

Navarro Pablo, M., & García Jiménez, E. (2018). Are CLIL students more motivated? An analysis of affective factors and their relation to language attainment. Porta Linguarum, 29, 71–90.

Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2018). CLIL and pedagogical innovation: Fact or fiction? International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 28, 369–390.

Richards, J. C. (2013). Curriculum approaches in language teaching: Forward, central, and backward design. RELC Journal, 44(1), 5–33. doi:10.1177/0033688212473293

Rumlich, D. (2017). CLIL theory and empirical reality - two sides of the same coin? Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 5(1), 110–134.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

San Isidro, X., & Lasagabaster, D. (2020). Students' and families' attitudes and motivations to language learning and CLIL: A longitudinal study. Language Learning Journal, 50(1), 119–134. doi:10.1080/09571736.2020.1724185

Seikkula-Leino, J. (2007). CLIL learning: Achievement levels and affective factors. Language and Education, 21, 328–341. https://doi.org/10.2167/le365.0

Shepherd, E., & Ainsworth, V. (2017). English Impact. An evaluation of English language capability. Retrieved from https://www.britishcouncil.es/sites/default/files/british-council-english-impact-report-madrid-web-opt.pdf

Contact address: Ana Halbach. Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, departamento de Filología Moderna, Universidad de Alcalá. C/Trinidad 3, 28100, Alcalá de Henares. (Madrid, Spain). E-mail: ana.halbach@uah.es.

En este cuestionario queremos preguntarte sobre cómo aprendes inglés. Verás que no te pedimos ningún dato personal para que sea confidencial. Nos gustaría que intentaras contestar a todas las preguntas con sinceridad y confianza.

Gracias por tu ayuda.

1. ¿Eres…

2. ¿Cuántos años tienes? ___________

3. ¿Cuál es tu lengua materna, la que hablas con tu familia?

4. ¿Qué lenguas se hablan en tu casa?

5. ¿Has viajado alguna vez a un país de habla inglesa?

6. ¿Qué actividades realizas en inglés?

7. Te vamos a indicar algunas frases para que nos digas si estás de acuerdo o no con ellas. Por ejemplo:

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

Nada de acuerdo Un poco Algo Bastante Totalmente de acuerdo

9. ¿Qué es lo que más te gusta de tus clases de inglés en el colegio? Cuéntalo aquí.

10. ¿Qué es lo que menos te gusta de tus clases de inglés en el colegio? Cuéntalo aquí

11. ¿Quieres decirnos algo más sobre las clases de inglés?

MUCHAS GRACIAS POR TU PARTICIPACIÓN

_______________________________

1 All quotes have been translated from Spanish by the authors.