FIGURE I. Representation of CLIL in teaching guides

Source: Compiled by author.

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2024-403-611

Noelia Mª Galán-Rodríguez

https://orcid.org/0001-6662-7269

Universidade da Coruña

Lucía Fraga-Viñas

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4602-3593

Universidade da Coruña

María Bobadilla-Pérez

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4972-5980

Universidade da Coruña

Tania F. Gómez-Sánchez

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1940-000X

Universidade da Coruña

Begoña Rumbo Arcas

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4748-8969

Universidade da Coruña

Abstract

Following the guidelines provided by the Council of Europe, Spanish educational administrations have been carrying out different strategies towards the development of the plurilingual competence. This has led to the introduction of CLIL sections in Spain where ‘generalist teachers’ are in charge of carrying out their non-linguistic subjects using an additional language as the language of instruction. This would require the generalist teacher to know the main principles of this approach as well as working with a set of competences related to the CLIL practice (Pérez-Cañado, 2018). Consequently, pre-service teacher training should prepare generalist teachers to carry out these CLIL sections to their full potential. Therefore, the main aim of this study is to present the results of a long-scale study concerning CLIL training at university level by analysing teaching guides. These teaching guides complied with two criteria: (1) they are related to the area of FLT and (2) they are taught in Spanish public schools in the Degree of Primary Education. Preliminary findings show that CLIL courses are often offered to pre-service teachers training to become FL educators rather than the generalist teachers. Furthermore, most of the analysed teaching guides do not show to be working on the six competences established by Pérez-Cañado (2018) in her study.

Keywords: CLIL, pre-service teachers, Primary Education, teaching guides, university training.

Resumen

De acuerdo con las directrices proporcionadas por el Consejo de Europa, las administraciones educativas españolas han implementado distintas estrategias encaminadas al desarrollo de la competencia plurilingüe. Se ha llevado a la introducción de secciones AICLE en España donde los ‘profesores generalistas’ son los encargados de impartir sus materias de área no lingüística a través de una lengua extranjera. Esto supone que el profesor generalista conozca los principios fundamentales de dicho enfoque y, para ello, trabajar el conjunto de competencias relacionadas con la práctica AICLE (Pérez-Cañado, 2018). En consecuencia, la formación inicial del profesorado debe preparar al profesorado generalistas para llevar a cabo estas secciones AICLE de la mejor manera posible. Por lo tanto, el objetivo principal de esta investigación es presentar los resultados de un estudio a larga escala sobre las materias AICLE analizando las guías docentes. Estas guías docentes cumplen los siguientes criterios: (1) son guías docentes relacionadas con el área de DLE y (2) se imparten en los grados públicos españoles en Educación Primaria. Los resultados preliminares muestran que la formación AICLE a menudo se ofrece a futuro profesorado especialista en LE en lugar de a profesorado generalista. Además, la mayoría de las guías docentes analizadas no desarrollan las seis competencias establecidas por Pérez-Cañado (2018) en su estudio.

Palabras clave: AICLE, profesorado en formación, Educación Primaria, guías docentes, formación universitaria.

For almost two decades Spanish educational administrations have been carrying out different strategies towards the implementation of linguistic polices in schools focusing on the students’ development of the plurilingual competence and following the guidelines provided by the Council of Europe. With that in mind, the regional areas of Spain launched different programmes to stablish bilingual education or plurilingual education, depending on whether it is a monolingual community (such as Madrid or Andalucía) or a bilingual community (such as Galicia or Catalonia). In all cases, English becomes the language of instruction of non-linguistic subjects in Primary and Secondary Education. Besides that, European funds have been invested in in-service teacher training programmes, very often more directed towards the improvement of their linguistic competence in the foreign language than on actual methodologies and approaches to teach any subject through a foreign language. The approach encouraged by educational administrations is Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL). While all these policies might be effective at some level in enhancing the development of the Primary school students’ competence in a foreign language, the first step to be taken in this endeavour is to train pre-service teachers pursuing a degree the Faculties of Education in such methodological approaches.

The adoption of the Bolognia Plan in Higher education in Europe prompted the transformation of all teaching guides of undergraduate and graduate degrees in the second decade of the twenty-first centuries. During that time, the Degree in Primary Education changed from a three-year programme to a four-year one. Both degrees qualified graduates to become generalist teachers in Primary Education. Those students interested in becoming English teachers in Primary education have to additionally complete the major in the area, such as it is the case with Physical Education or Music. In Spain’s educational system ‘generalist teachers’ are in charge of introducing Maths, Science, Social Science, Arts and Crafts, but Foreign Languages, Music and Physical Education are taught by these specialists. Interestingly, while the transformation of the teaching guides during the Bolognia process took place almost simultaneously with the implementation of bilingual/plurilingual linguistic policies in schools, there was not coordination among Educational administrations and universities towards the definition of the common goal, in this case considering the pre-service teaching training needs to prepare teachers for their future practice in bilingual/plurilingual schools and having to use the foreign language to introduce Maths, Science or Arts and Crafts through English.

Legally speaking, so far, the only mandatory requirement teachers need in order to become CLIL teachers in Spain is a language certificate: most autonomous communities only require their teachers to have a B2 language certificate in the target language to teach in bilingual schools, being Madrid and Catalonia the only communities which ask for a C1 language certificate (Durán-Martínez & Beltrán-Llavador, 2020, p. 171). This resonates with the idea of CLIL teacher training focused only on language proficiency, setting aside other competences a CLIL teacher may need.

In this study, the teaching guides of the Degree in Primary Education were analysed to see to what extent public funded higher education institutions in Spain are actually preparing pre-service teachers to exercise their profession in bilingual/plurilingual educational settings focusing on CLIL.

Plurilingualism has been promoted in all educational levels by the European Commission for more than two decades (1995, p. 47). Nevertheless, the aim of achieving bilingual education required not only foreign language learning, but also triggered the implementation of policies that would lead to significant challenges and changes in all the spheres of education. In a general level, the Common European Framework for Reference (CEFR; Council of Europe, 2001) must be mentioned due to its significant impact in the unification of foreign language levels, with an influence that has already surpassed the European borders (Nishimura-Sahi, 2020; Sidhu et al., 2018; Than Hai, 2018). In Higher Education, the creation of the European Area Education and Bologna Process (EHEA) endorsed the English-medium instruction (EMI), fostered the bilingual graduate programmes and launched the Erasmus+ initiative, among others. In primary and secondary education, Content Language Integrated Learning (hereinafter CLIL) appeared in 1994 and became a key methodology to meet the European objective of multilingualism:

Multilingualism is one of the cornerstones of the European project and a powerful symbol of the EU’s aspiration to be united in diversity. Foreign languages have a prominent role among the skills that will help equip people better for the labour market and make the most of available opportunities. (European Commission, 2015, p.13)

As teachers are one of the main stakeholders and promoters of language policy, it is important that their teacher training caters to this plurilingual/bilingual reality. In regard to in-service teacher training, Durán-Martínez & Beltrán-Llavador (2020) argue that “training for bilingual teaching has not been homogeneous in Spain so far” (2020, p. 171) and point out to several studies which mention (1) compulsory training modules (Fernández and Halbach, 2011; Lova Mellado, Bolarín Martínez, and Porto Currás, 2013), (2) language courses (Olivares and Pena 2013), (3) summer programs and (4) optional postgraduate courses on CLIL teaching (Durán and Beltrán 2013). Concerning the different training courses, Palacios, Gómez & Huertas (2018, p. 145) mention five different courses taken by in-service CLIL teachers in several autonomous communities in Spain:

CLIL implied that other subjects started to be taught in a foreign vehicular language in a meaningful and planned manner. In Spain, CLIL programmes appeared in 2004 and the number of schools participating on the programme has rocketed since then. Indeed, Coyle claimed already in 2010 that “Spain is rapidly becoming one of the European Leaders in CLIL practice and research” (p. viii). Just to illustrate the reality with some data, in the Autonomous Community of Madrid the number of state schools increased from 26 to more than 330 (Antropova et al. 2021).

Despite the repercussion that plurilingual programmes have had in the country, research in CLIL results, experiences and teaching guides is still quite scarce. Most research available deals with quantitative studies based on questionnaires to CLIL in-service teachers. As a common conclusion reached, teachers pinpointed deficiencies and needs in their respective training, particularly in their fluency in the foreign language (English) and researchers have pointed out significant gaps in teachers’ knowledge of what CLIL is, CLIL methodology and resources. These conclusions are common to all the levels. Starting with primary education, Antropova et al. (2021) shared the results of their study with 75 in-service Natural and Social Science teachers of primary education in the Autonomous Community of Madrid. Data obtained revealed the concept of bilingualism is not clear among teachers, they do not have accurate knowledge of CLIL basic principles, and they do not use enough didactic resources associated to the method. Several teachers also claimed not to believe the bilingual programmes are being successful. Researchers object thought that the reason why is that the programme is not being correctly implemented, according to what they observed during the time they conducted their research and the results of the questionnaires. They also point out that teachers’ belief in CLIL is fundamental to its success. In similar research, Durán-Martínez and Beltrán-LLavador (2020) surveyed 97 teachers of bilingual programmes about their needs. Teachers numbered their priorities in training as follows: 1-language proficiency, 2-investment in training, 3-contact with native speakers, 4-CLIL specific training, 5-materials design, 6-pronunciation courses, 7-sharing experiences, and 8-ICT training. These results show how CLIL in-service teachers focus on language rather than CLIL methodology. Other studies (Estrada, 2021) with teachers at primary level reached out similar conclusions to the ones above mentioned.

Regarding studies with in-service teachers at secondary school, the results are akin. Morton (2019) made teachers reflect on language as a curriculum concern in CLIL, as a tool for learning, and as competence. Morton highlighted the global scarcity of training in CLIL existent for in and pre-service teachers, despite having been implemented more than a decade ago and its current popularity; and the shortcomings in research about CLIL programmes. Through some interviews with in-service secondary teachers, it was revealed that teachers do not plan learning sequences with systematic language goals, that they respond positively to observation, critical thinking and discussion practice with simulated CLIL classrooms; and they do not consider language as a scaffolding to build knowledge upon. Another study with 17 teachers of bilingual education centres of Madrid Autonomous Community carried out by Cabezuelo Gutiérrez and Fernández Fernández (2014) also pointed to teachers’ perception of a need for improving the training they receive, their wish to receive more training and some acknowledgement that they need to enhance their language skills, although this last remark is way lower than in previous studies conducted.

Moving on to Higher Education, results are not very distant. Professors who took part in Plurilingualism Promotion Plan at the University of Almería, claimed to need more training in foreign language (English), particularly in speaking and interaction but showed no interest in more training in specific methodology in CLIL, materials or tools (Sánchez Pérez and Salaberri Ramiro, 2017). Teachers participating received some training programme on plurilingual teaching methodologies and were asked to evaluate it through 16 indicators after three years in the programme, with results showing a positive development of the elements analysed.

Palacios, Gómez and Huertas (2018) exposed the needs of formation in CLIL of future teachers such as the improvement in communicative/linguistic competence, methodological/professional competence and the digital one; and the necessity of higher education centres to offer bilingual programmes. Likewise, Olmeda, Guillén y González (2016) pointed out how universities had to resort to masters or the offering of bilingual grades but those are often implemented without a proper reflection on the results aimed. In order to proof those allegations of teacher training flaws, Portolés y Martí (2020) surveyed 110 pre-service teachers before and after a short course on CLIL. Results indicated teacher’s knowledge and perceptions on CLIL pre-course were wrong: they only seemed to conceive the benefits of the C for Communication and basically ignore the other three (Content, Cognition and Culture). Moreover, more than 65% consider it might endanger the learning of contents. After the short course on CLIL, results obtained were a little better but still far from the ones desirable.

As it has been previously mentioned, teacher training is a valuable tool for pre-service and in-service teachers. It goes without saying that CLIL teachers would need further training from the one given at a general level as teaching using the CLIL methodology comes with its own idiosyncrasies. After reviewing several studies on what a competent CLIL teacher profile should entail, Pérez-Cañado (2018) highlights several core CLIL teacher competences: (1) linguistic competence, (2) pedagogical competence, (3) organizational competence, (4) scientific knowledge, (5) interpersonal and collaborative competencies, (6) reflective and developmental competence.

The linguistic competence is generally understood as the ability to communicate as well as having linguistic knowledge and also encompassing “intercultural aspects” (Pérez-Cañado, 2018, p. 213). It can be divided into BICS (Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills) and CALP (Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency): the first one deals with language used on daily situations and social interaction whereas the second one has to do with abstract language used in academic settings. Although some studies point out to pre-service and in-service teachers’ perceptions of their own linguistic competence to be subpar (Durán-Martínez & Beltrán-Llavador, 2020; Pons-Seguí, 2020), Pérez-Cañado (2018) argues that: after several further years of CLIL implementation, the need for linguistic training now appears to take a backseat. More recently, teachers seem to harbor a much more optimistic and self-complacent outlook on their linguistic level, which thus seems to have reached adequate levels for them to be able to teach confidently (p. 215).

This is especially relevant in teachers with less than 3 years of experience in CLIL programmes who are reported to be more confident in their linguistic skill than their more experienced counterparts (Pérez-Cañado, 2018). Furthermore, previous experience abroad is also said to have a positive impact on language proficiency (2018, p. 215). However, the author also states that non-linguistic area and primary and infant education teachers still need linguistic training (2018, p. 215).

The pedagogical competence encompasses several methodological issues which the CLIL teacher should be aware: student-centred methodologies, different learning environments and resources (in which ICT should be considered) and a “transparent, holistic, and formative type of evaluation” (2018, p. 213). Many studies (Palacios, Gómez & Huertas, 2018; Durán-Martínez & Beltrán-Llavador, 2020; Pons-Seguí, 2020; Estrada, 2021) state the need to train CLIL teachers on these issues. Additionally, it has been pointed out that recent research has shown improvement in the following areas: more active methodologies, original materials, a greater use of ICT, attempts at curricular integration and diversified evaluation concerning techniques and instruments. However, some training needs remain constant over time: “materials design and adaptation; catering to diversity and mixed-ability groups; the use of the English language portfolio, project-based learning (PBL), and the lexical approach; the full incorporation of computer-mediated communication techniques; and the inclusion of the oral component in exams” (Pérez-Cañado, 2018, p. 216). Moreover, “it appears that preservice teachers are not receiving sufficient specific CLIL methodological training in existing undergraduate degrees” (2018, p. 216).

In similar lines, the organizational competence is defined by classroom groupings, learning modalities, classroom management techniques and control strategies. Concerning classroom management in particular, several studies regarding in-service CLIL teachers’ perceptions of their training needs show this issue to be a concern (Cabezuelo Gutiérrez & Fernández Fernández, 2014; Pons-Seguí, 2020). It is significant to mention here that those who mentioned classroom management are in service teachers whereas pre-service teachers do not consider classroom management or other control strategies to be an important issue, focusing instead on language proficiency (linguistic competence) and methodological implications (pedagogical competence) (Pons-Seguí, 2020, p. 289).

Concerning scientific knowledge, Pérez-Cañado (2018) establishes a dual categorisation between subject-specific knowledge (e.g., content knowledge) and the theoretical foundations of CLIL. Some studies (Antropova et al., 2021) show CLIL teachers’ lack of familiarity with language and learning theories regarding CLIL as well as lack of interest on methodological principles concerning plurilingualism by teacher trainers at university level (Sánchez-Pérez & Salaberri-Ramiro, 2017, p. 151). In terms of teacher training, scientific knowledge about CLIL is relevant as “it is the area in which the lowest level and highest training needs have been detected” (Pérez-Cañado, 2018, p. 216). Furthermore, some differences can be found regarding nationality as pre-service teachers from Central and East Europe are said to have more theoretical knowledge on CLIL than their Latin American counterparts (2018, pp. 216-217).

As for interpersonal and collaborative competencies, the first one is linked to Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences (1983), specifically the interpersonal intelligence, based on the ability to relate well with people and manage (social) relationships: this is particularly relevant at classroom level to be able to handle problems and create meaningful relationships with students as well as create a safe space to promote participation (Pérez-Cañado, 2018, p. 214). Regarding collaborative competence, teamwork has increased in the CLIL classroom thanks to PBL “which increases coordination and helps attune the programs to specific student needs” (2018, P. 216). However, it bears noting that CLIL teachers also report lack of communication among them and other CLIL teachers, which is seen as a problem and a need (Durán-Martínez & Beltrán-Llavador, 2020; Galán-Rodríguez, 2020).

According to Pérez-Cañado (2018), all these competences are equivalent to the reflective and developmental competence, whose cornerstones are lifelong learning and continuous teacher’s update on CLIL theories and practices. Studies such as Morton (2019) and Durán-Martínez & Beltrán-Llavador (2020) show that Continuing Professional Development (CPD) is an area which needs further improvement as CLIL teachers “have mostly never obtained study licenses for further research or participated in specific MA degrees in CLIL, in exchange programs, or in methodological upgrade courses abroad. They also lack familiarity with publications on CLIL” (Pérez-Cañado, 2018, p. 217). Therefore, working on CPD and fostering reflective practices should be part of a teacher training curriculum in order to fulfil teacher training needs which would result into successful CLIL implementations.

The aim of this paper is to analyse the foreign language teaching guides of the Degrees in Primary Education concerning CLIL training. We seek to answer the following research questions:

Initial training for bilingual teaching in Spain (the context of this study) has an institutional design. The higher education institutions follow the guidelines provided by the ISDC (UNESCO, 2012) in regard to pre-service teacher training degrees. With the purpose of establishing a common ground on the European Higher Education Area, the National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation (ANECA) established some directions on the creation of teaching guides in 2003. Although it is possible for each higher education institution to adapt these general prescriptions (White Paper, 2005; Naya-Rivero, Gómez-Sánchez, Rumbo-Arcas and Segade-Pampín, 2021), all institutions have structured their degrees in Primary Education into four academic years where there are common mandatory subjects to all pre-service teachers and optional subjects which belong to different teaching majors (e.g., Foreign Languages, PE., Music, etc.).

In 2007, the specific regulations on official university degrees were approved and it has affected all higher education institutions. It has contemplated that primary school teachers must “effectively address language learning situations in multicultural and multilingual contexts” (BOE, 2007, p.53747). Therefore, teacher training must endeavour to prepare future teachers for these plurilingual realities.

After compiling all the documentation, a descriptive exploratory analysis has been carried out in order to extract all the information that refers to the subjects related to CLIL. Secondly, competences and learning results from these documents have been classified under Pérez Cañado’s (2018) division of competences. The starting hypothesis, developed from the theoretical framework and the contextualization, establishes a great variability in the pre-service training of primary school teachers for CLIL.

For the purposes of our analysis, after a first selection of 501 foreign language teaching guides, we proceeded to analyse the main curricular elements (competences, learning goals, and contents). After a closer reading they were grouped in two main categories: whether CLIL is present or not. If the CLIL approach is present, the main curricular elements are analysed. An exploratory and descriptive analysis was applied to rank the most repeated categories and the conceptualization of these. After detecting and classifying curricular elements, an Excel programme was used to synthesize in figures the frequency of the categories, reflecting the overall picture of the syllabus’ views on these aspects of the pre-service teacher training in CLIL courses.

The content analysis of the teaching guides was carried out by using the following software: MAXQDA for the qualitative data set and SPSS for the quantitative data. Contents were classified into four categories (syntactic-discourse, pedagogical, competence-based and CLIL-focused) after carrying out a thematic analysis of the data provided. Likewise, the contents of the teaching guides for CLIL courses were classified into five categories: 4 C’s (Coyle et al. 2010), plurilingualism, planning, assessment and resources.

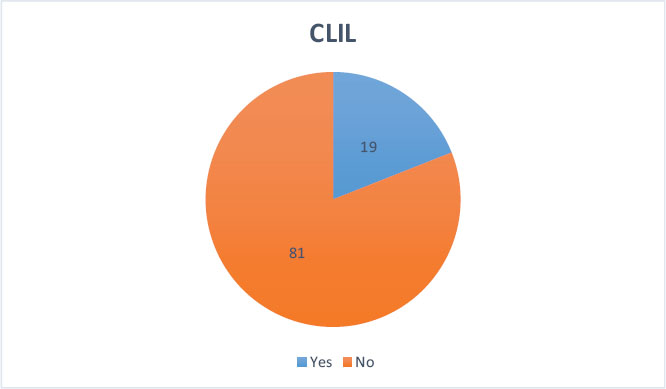

The overall sample of this study contains 501 teaching guides from the Spanish public funded universities that offer the degree of teacher training in Primary Education (ISCED1). The teaching guides that mention CLIL explicitly add up to 19% (Figure I). In order to answer to the research questions, these are analysed in terms of competences and contents in the results section of this paper.

FIGURE I. Representation of CLIL in teaching guides

Source: Compiled by author.

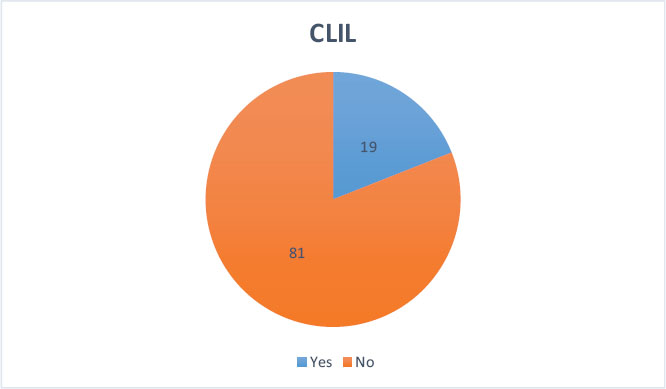

From all the subjects that mention CLIL, 47.31% are optional subjects on the major in foreign language teaching (pre-service who wish to become foreign language teachers). Additionally, 33.3% of the analysed teaching guides represented were optional subject available for all students in the degree while only 19.35% were mandatory (Figure II).

FIGURE II. Type of subject

Source: Compiled by author.

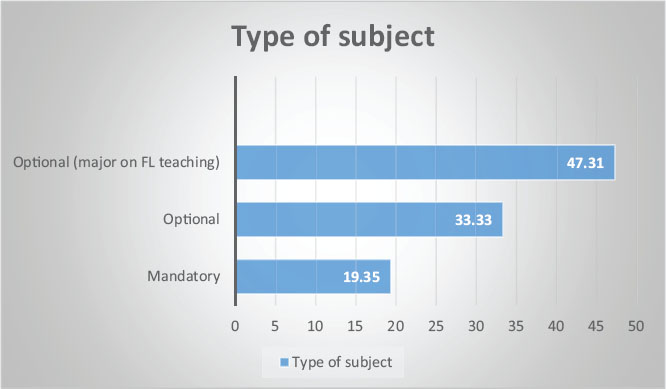

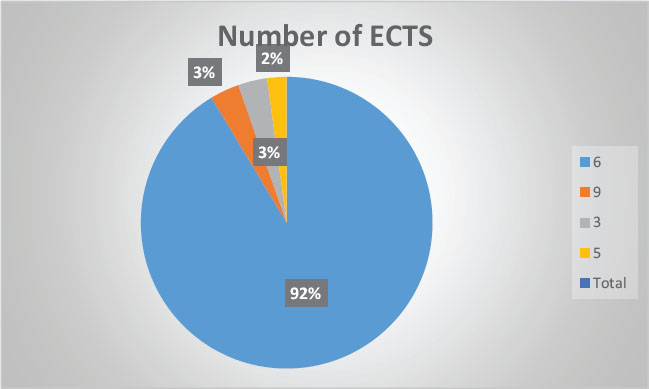

Overall, there is a clear tendency towards 6 ECTS’ subject (92% of the total) among the analysed teaching guides (Figure III).

FIGURE III. Number of ECTS

Source: Compiled by author.

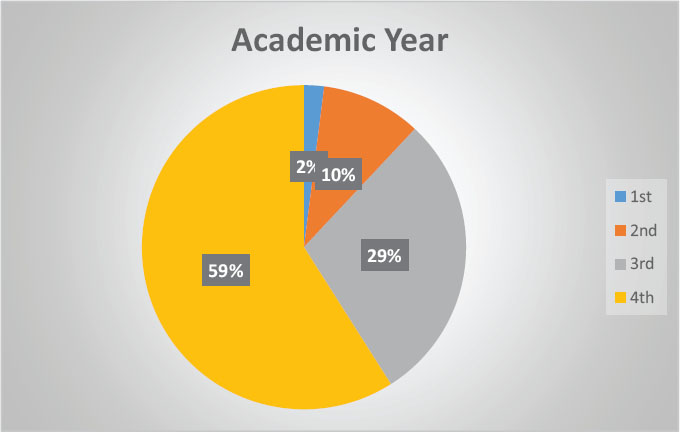

As it can be seen on Figure IV, most of the courses (59%) that deal with CLIL are taught in the last year of the degree (4th year). This is not surprising as most of them are optional subjects which are usually offered in the last two years of undergraduate programmes in Spain.

FIGURE IV. Academic year

Source: Compiled by author.

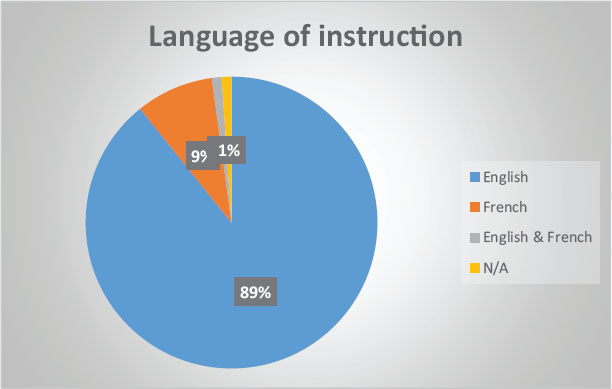

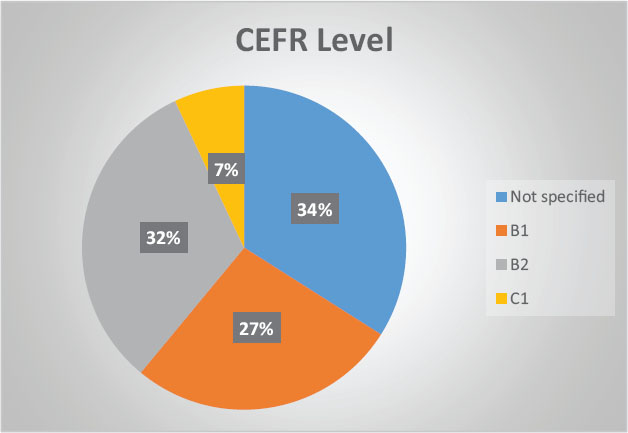

As far as the language of instruction is concerned, there is a clear predominance of English over other languages which resonates with the idea of English as lingua franca (Figure V). Moreover, according to the language scale of proficiency of the CEFR, most of the courses mention the intermediate level (B2: 32%; B1: 27%) in their teaching guides (Figure VI). It bears noting that in Spain students are supposed to finish their upper secondary education with an intermediate level in their first foreign language.

FIGURE V. Language of instruction

Source: Compiled by author.

FIGURE VI. CEFR level

Source: Compiled by author.

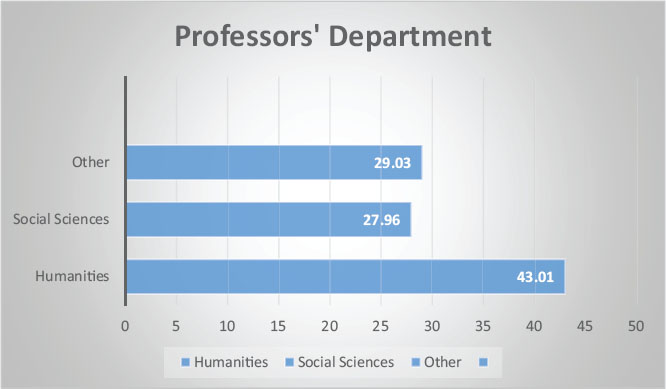

Despite the fact the degree of primary education is taught in the faculty of education (social sciences), 43% of the professors in charge of these courses belong to humanities departments while almost 28% are part of FL didactics departments. The remaining 29% classified as “other” may have provided further information of the topic (Figure VII). However, in most of these cases the department in charge of these courses was not specified in the teaching guide.

FIGURE VII. Professors’ Department

Source: Compiled by author.

Following Pérez Cañado’s (2018) classification, the first competence to consider is the linguistic competence. It is not surprising to see that 89.2% of teaching guides work on the linguistic competence as one of the key factors in pre-service teacher training. This is so because we are analysing subjects that mention CLIL explicitly and language is one of the cornerstones of this approach. It also bears noting that the educational framework concerning CLIL requires teachers to have language certificate equivalent to, at least, a B2. Interestingly, the most frequent language level of proficiency found in the qualitative data analysis was ‘B1’ (50 documents). Furthermore, the analysis of this competence emphasises the communicative approach since several keywords evolve around the topic: ‘understand’ (f=81), ‘oral/orally’(f=82/101), ‘express’(f=86), ‘communication’ (f=83), ‘situations’(f=88) and ‘written’(f=87).

Regarding the pedagogical competence, 97.8% of teaching guides work on this, being the most frequent competence found in this analysis. This is to be expected due to the pedagogical nature of the degree these teaching guides belong. The descriptors for this competence focus on the pre-service teacher as a conduct for the ‘curriculum’ (f=80) with emphasis on ‘contents’ (f=77) and ‘competences’ (f=71), as well as their role as evaluators (‘evaluate’: f=86) and designers (‘design’: f=57).

The organisational competence appears in 54.8% of teaching guides and highlights aspects such as the ‘ability’ (f=62) to adapt to the ‘classroom’ (f=72) and students’ ‘level’ (f=66). It is also striking that several keywords from this data set such as ‘contents’ (f=93) often appear on the aforementioned pedagogical competence: this may be because the descriptors of both competences are of a similar nature as both focus on the practical aspects of teaching practice.

Surprisingly, although all the analysed teaching guides mention CLIL (and some are focused solely on the CLIL approach), competence wise, only 3.2% could be classified into the scientific competence established in Pérez Cañado (2018). This opens up a debate on how CLIL is seen at higher education: as a content element rather than a teaching practice that requires a competence-based view of the issue. From the data gathered, two of these teaching guides endeavour to teach pre-service teachers how ‘to design CLIL projects’ and the last one ‘to know CLIL terminology.’

The interpersonal and collaborative competencies is found on 58.1% of teaching guides, which is striking bearing in mind the emphasis put on collaboration among teaching professionals in these last decades. In the same line, in the qualitative analysis of this set keywords such as ‘cooperative’, ‘team’ and ‘collaboration’ do not appear as much as expected (f=60, f=50 and f=10 respectively). In contrast, ‘autonomous’ is found in 100 documents. In regard to interpersonal skills, issues such as classroom atmosphere are the main ideas found on this data reading: ‘problems’ (f=82), ‘develop’ (f=76), ‘situations’ (f=75), ‘boost’ (f=78) and ‘different’ (f=63).

Having considered the importance of a lifelong learning experience based on continuous improvement of the teaching practice, the reflective and developmental competencies found in these documents underline ‘practice’ (f=116), ‘autonomous’ (f=118), ‘skills’ (f=80) and ‘reflect’ (f=73). Additionally, keywords such as ‘develop’ and ‘development’ appear frequently (f=66 and f=72 respectively). Quantitative wise, this is one of the competences found the most in this study (77.4% of teaching guides). This bodes well for the development of this competence and the idea of lifelong and reflective learning/teaching among future Primary school teachers.

It is worth mentioning that not all the competences found in the teaching guides could be classified under Pérez Cañado’s (2018) classification as 51.6% of teaching guides contain learning goals related to the idea of education as a social agent (‘contexts’: f=89; ‘social’ =61; ‘socials’: f=51), critical thinking (‘develop’: f=113; ‘boost’: f= 66) and cultural expressions (‘cultural’: f=66; ‘literature’: f=45).

As it has been mentioned, CLIL teacher training at higher education is still very much focused on contents over competences. Therefore, in order to provide an overview on this matter, it is necessary to analyse the contents of these teaching guides. In this analysis, we can distinguish between CLIL-specific courses and other courses that mention CLIL. Overall, 23 teaching guides belong to CLIL-specific courses while the remaining 70 teaching guides just list it with other contents (e.g., Didactics of Foreign Language courses).

Following the thematic analysis, the contents of the 93 teaching guides analysed were classified as:

Overall, the syntactic-discourse category is the least frequently found on the contents for these teaching guides, represents 16.3% of the total data set. Similarly, the competence-based category represents 22.2%: both categories are related to the linguistic competence. This can be interpreted in two ways: on the one hand, the high frequency of the linguistic competence is further backed up by the contents; on the other hand, the limits of what competence-based learning and content-based learning are still blurred. Once again, catering to the pedagogical nature of the degree, pedagogical contents are the most frequently found among teaching guides with a total of 32.5%. In regard to the pedagogical contents concerning CLIL, 29.1% are classified as such (Table I).

TABLE I. Content Analysis

|

|

N |

Percentage |

Case percentage |

Content Analysis |

Syntactic-discourse |

33 |

16.3% |

37.5% |

Pedagogical |

66 |

32.5% |

75% |

|

Competence-based |

45 |

22.2% |

51.1% |

|

CLIL-focused |

59 |

29.1% |

67% |

|

Total |

|

203 |

100% |

230.7% |

Source: Compiled by author.

Those teaching guides which were found to have CLIL-focused contents were further analysed into the following sections in order to determine what is taught about this approach (Table II):

TABLE II. CLIL-focused Contents

|

|

N |

Percentage |

Case percentage |

CLIL-focused Contents |

4 C’s |

15 |

17.2% |

62.5% |

Plurilingualism |

8 |

9.2% |

33.3% |

|

Planning |

23 |

26.4% |

95.8% |

|

Assessment |

23 |

26.4% |

95.8% |

|

Resources |

18 |

20.7% |

75% |

|

Total |

|

87 |

100% |

362.5% |

Source: own elaboration.

The analysis of the aforementioned teaching guides sheds light on a lack of CLIL pre-service teaching training, which is in line with Morton’s (2019) study where in-service teachers reported the same. Furthermore, the predominance of English as the language of instruction in these guides is outstanding. In fact, it represents 90% of the total, which goes against the idea of the CEFRCV (Council of Europe, 2020) of equality among languages and setting aside ‘dominant’ languages. What is more, this focus on English would be understood as a bilingual practice rather than a plurilingual one.

Competence-wise, this study shows a clear imbalance among the competences set by Pérez Cañado (2018) on what a CLIL teacher should master. Unsurprisingly, there is an obvious emphasis on the linguistic competence focused on the communicative approach (specifically on working the four language skills) which could be directly related to the area of expertise of the professors in charge of those courses (mostly from the humanities areas). Although language is indeed part of the CLIL approach, the predominance of the linguistic competence could stem from the misclassification of this method as a language learning approach rather than an integrated one: however, further studies need to be carried out.

As expected, the pedagogical competence is found in the majority of the teaching guides which bodes well for the practical implications of teaching at primary school where different learning environments and resources are present. In contrast, the organisational and interpersonal and collaborative competencies report a low score: we presume the organisational competence may be worked more directly during internship periods as it is better acquired when working in context on a specific classroom. Concerning the interpersonal competence, it is especially necessary if we consider the challenges using a FL may have on students cognitively and affectively, thus, building rapport with them is something CLIL teachers should be able to accomplish. Similarly, collaboration among departments is fundamental when dealing with this approach: it is because of this that it is quite concerning that the collaborative competence does not present higher scores.

Despite the fact that all analysed teaching guides mention CLIL explicitly, it seems striking that only three out of these work on the scientific competence. Since this competence is directly related to this approach and its main principles, it would be expected that all those courses that mention CLIL would have competences or learning goals related to this matter. A possible explanation for this could be CLIL is seen as a content-based issue rather than a competence-based one. This resonates with the findings of this study concerning the contents of the teaching guides.

The analysis of the contents revealed that there is a tendency in the teaching guides to include competence-based elements to the contents section. This is why there is a clear link between some of the contents and the classification of competence (e.g., the competence-based contents are directly related to the linguistic competence). Moreover, an overall focus on pedagogical contents both of a general nature (classified as ‘pedagogical’) and CLIL-related (classified as ‘CLIL-focused’) has been reported.

In regard to RQ 2, the analysis of the contents showed that Coyle’s (2010) 4 C’s, which are the cornerstones of this approach, are not to be found in most teaching guides, which resonates with the results found for the scientific competence. If future teachers are not aware of the idiosyncrasies of this approach it is quite likely that the CLIL-lessons they may teach would end up being ‘translated’ versions of the usual non-CLIL lessons. The absence of more contents related to plurilingualism does not cater to the education curriculum which has established the plurilingual and pluricultural competence as a key competence for lifelong learning. What is more, plurilingualism would help future teachers to reject the idea of compartmentalised learning and to encourage integrated learning into their teaching practice. In addition, plurilingual approaches would foster the presence of several languages of instruction apart from English. Practical aspects of the teaching practice such as planning, assessment and resources are found in most of the analysed contents. This is positive as it caters to the pedagogical, organizational and reflective competencies. The fact that these contents are specific to the CLIL approach can only help to better prepared teachers of CLIL practices.

All in all, the pre-service teacher training in CLIL and the current educational paradigm are at odds on several issues: language training seems to be an issue (Cabezuelo Gutiérrez and Fernández Fernández, 2014). Even though most autonomous communities require CLIL teachers to have a B2 or even a C1 certificate, the teaching guides analysed still mention a B1 level in 27% of the cases. This creates a void that higher education training does not fill. Another issue to consider is the optional nature of these subjects: most of them are optional subjects taught in the major in FL teaching. Therefore, generalist teachers do not receive this training. This leads to a bleak panorama: at school level, CLIL subjects are taught by generalist teachers, who need to rely on their university training to put CLIL into practice. However, as it has been proved, most of this training is focused on FL teachers, who will most likely not be CLIL teachers themselves.

This research points out to a lack of CLIL training among pre-service primary teachers in Spanish public funding universities based on their teaching guides. However, one of the limitations of the study is the fact that the teaching guides may not correspond entirely to the actual teaching practice: this could only be further analysed by carrying out systematic observation of the aforementioned lessons. Furthermore, some subjects listed in the study programme concerning the object of the study were not available, hence, impossible to analyse. Further research may include studies on pre-service teachers’ perceptions on their CLIL training and their knowledge of said approach. Other possible lines of research entail the analysis of the whole data set in regard to plurilingual training.

ANECA. (2005). Libro Blanco. Título de Grado en Magisterio, Vol.1. España: Madrid. http://www.aneca.es/var/media/150404/libroblanco_jun05_magisterio1.pdf

Antropova, S., Poveda Garcia-Noblejas, B., & Carrasco Polaino, R. (2021). Teachers’ Efficiency of CLIL Implementation to Reach Bilingualism in Primary Education. Journal of Learning Styles, 14 (27), 6–19.

BOE (2007). Order ECI/3857/2007, of 27 December, which establishes the requirements for the verification of official university degrees that qualify for the exercise of the profession of teacher in Primary Education. BOE no. 312, December 29 2007.

Cabezuelo Gutiérrez, P., & Fernández Fernández, R. (2014). A case study on teacher training needs in the Madrid bilingual project. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning, 7(2), 50–70. doi:10.5294/laclil.2014.7.2.3 eISSN 2322–9721.

Comunidad de Madrid: Consejería de Educación y Juventud. (2021). PLAN DE FORMACIÓN EN LENGUAS EXTRANJERAS: Curso 2020–2021. Comunidad de Madrid. http://gestiondgmejora.educa.madrid.org/pfle21/index.php/index/seccion/0

Consejería de Educación, Cultura y Deportes, Castilla-La Mancha. (2021). Plan de Formación del Profesorado 2021/2022. Castilla-La Mancha. https://www.castillalamancha.es/sites/default/files/documentos/pdf/20211028/plan-formacion-profesorado-crfpclm-2122b.pdf

Consejería de Educación, Junta de Andalucía. (2016). Plan Estratégico de Desarrollo de las Lenguas en Andalucía: Horizonte 2020. Junta de Andalucía. https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/export/drupaljda/plan_estrategico.pdf

Consejería de Educación, Universidades, Cultura y Deportes, Gobierno de Canarias. (2021). Programa Lenguas Extranjeras y Programa Auxiliares de Conversación. Gobierno de Canarias. https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/educacion/web/programas-redes-educativas/programas-educativos/lenguas_extranjeras/

Consellería de Cultura, Educación e Universidade, Xunta de Galicia. (2021). Linguas Estranxeiras. Xunta de Galicia. http://www.edu.xunta.gal/portal/es/linguasestranxeiras

Council of Europe. (2001) Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching and Assessment. Cambridge Assessment English.

Council of Europe. (2020). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume. Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg.

Coyle, D. (2010). Foreword. In D. Lasagabaster; & Y. Ruiz de Zarobe (Eds.), CLIL in Spain: Implementation, results and teacher training, vii–viii. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars.

Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge University Press.

Durán, R., & F. Beltrán. (2013). Nuevos modelos de formación del profesorado de inglés: el Caso de Castilla y León. Profesorado, 17, 307–323.

Durán-Martínez, R., & Beltrán-Llavador, F. (2020). Key issues in teachers’ assessment of primary education bilingual programs in Spain, International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23 (2), 170–183

Estrada, J. L. (2021). Diagnóstico de necesidades formativas entre maestros AICLE en formación inicial. European Journal of Child Development, Education and Psychopathology, 9(1), 1–16.

European Commission. (1995). White Paper on Education and Training. Teaching and Learning. Towards de Learning Society. Brussels: Archive of European Integration. Retrieved from http://europa.eu/documents/comm/white_papers/pdf/com95_590_en.pdf

European Commission (2015). Erasmus+ Programme Guide. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/discover/guide/index_es.htm, accessed 15 April, 2016.

Fernández, R., & A. Halbach. (2011). “Analysing the Situation of Teachers in the Madrid Bilingual Project after Four Years of Implementation.” In Y. Ruiz de Zarobe, J. Manuel Sierra & F. Gallardo del Puerto (Eds.), Content and Foreign Language Integrated Learning. Contributions to Multilingualism in European Contexts, (pp. 41–70). Peter Lang.

Galán-Rodríguez, N. M. (2020). Motivation in CLIL: Research in Secondary Education in the Galician Context. Peter Lang.

Gardner, H. E. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Basic books.

Lova Mellado, M., M. J. Bolarín Martínez, & M. Porto Currás. (2013). Programas bilingües en educación primaria: Valoraciones de Docentes. Porta Linguarum, 20, 253–268.

Morton, T. (2019). “Teacher education in content-based language education”. In S. Walsh, & S. Mann (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of English Language Teacher Education (pp. 169–183). Routledge.

Naya-Rivero, M. C., Gomez-Sanchez, T. F., Rumbo-Arcas, M. B., & Segade-Pampín, M. E. (2021). Comparative interregional study of Mathematical Education for preservice Primary Teachers. Revista latinoamericana de investigación en matemática educativa, 24(2), 207–233.

Nishimura-Sahi, O. (2020). Policy borrowing of the Common European Framework of Reference for languages (CEFR) in Japan: an analysis of the interplay between global education trends and national policymaking. Asia Pacific Journal of Education. Routledge: Taylor & Francis group. DOI: 10.1080/02188791.2020.1844145

Olivares, M., & C. Pena. (2013). How Do We Teach Our CLIL Teachers? A Case Study from Alcalá University. Porta Linguarum, 19, 87–99.

Olmeda, G. J., Guillén, M. T. F., & González, R. (2016). La formación inicial de los maestros de educación primaria en el contexto de la enseñanza bilingüe en lengua extranjera. Bordón. Revista de pedagogía, 68(2), 121-135.

Palacios, F. J., Gómez, M. E., & Huertas, C. A. (2018). Formación inicial del docente AICLE en España: Retos y claves. Estudios Franco-Alemanes, 10, 141–161.

Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2018). Innovations and challenges in CLIL teacher training. Theory Into Practice, 57(3), 1–10.

Pons-Seguí, L. (2020). Are Pre-Service Foreign Language Teachers Ready for CLIL in Catalonia? A Needs Analysis from Stakeholders’ Perspective. Porta Linguarum, 33, 279–295.

Portolés, L., & Martí, O. (2020). Teachers’ beliefs about multilingual pedagogies and the role of initial training. International Journal of Multilingualism, 17(2), 248–264.

Sánchez-Pérez, M. M. & Salaberri-Ramiro, M. S. (2017). Implementing Plurilingualism in Higher Education: Teacher Training Needs and Plan Evaluation. Porta Linguarum, Monográfico II, 139–156.

Sidhu, G. K., Kaur, S., & Chi, L. J. (2018). CEFR-aligned school-based assessment in the Malaysian primary ESL classroom. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 8, 452–463. DOI: 10.17509/ijal.v8i2.133311

Than Hai, L. T. (2018). Impacts of CEFR-aligned learning outcome implementation on assessment practice at tertiary level education in Vietnam: An exploratory study. Hue University Journal of Science: Social Sciences and Humanities, 127 (6B), 87–99. DOI: 10.265459

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2012). International standard classification of education: ISCED 2011. Comparative Social Research, 30.

Contact address: Noelia Mª Galán-Rodríguez, Universidade da Coruña, Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Departamento de DIDES e MIDES. Campus de Elviña, S/N, 15071. A Coruña, Galicia (España). E-mail: noelia.galan@udc.es