CHART I. Age Ranges*Gender of Salesian Principals of the Americas (n=330)

Note: Percentages are reported by column. X2 (4) = 7.9, p<0.01.

Source: Compiled by the author.

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2023-402-599

Amparo Jiménez Vivas

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2739-6581

Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca

Patricia Lorena Parraguez Núñez

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6554-3338

Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca

Abstract

In the complex framework that characterizes Latin American education, marked by strong inequality and unsatisfactory results further intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic, this article describes and analyzes, from a gender perspective, the pedagogical leadership of a group of Salesian Catholic schools in 21 countries of the continent, considered by its relevance as a major factor towards improving learning. For this purpose, a quantitative study was carried out by applying the questionnaire technique, with a probabilistic and stratified sample of 330 principals. Among the main results, we found that there was a predominance of female school leadership (66.7%) and more consolidated pedagogical approach practices in women who perform this role, such as supervision and monitoring of teaching practice, collaborative culture for professional development and decision making oriented to teaching and learning. There are other practices that require greater drive and training for all principals and their teams.

Keywords: gender issues, educational administration, Catholic schools, instructional leadership, statistical analysis.

Resumen

En el complejo entramado que caracteriza la educación latinoamericana, marcada por una fuerte desigualdad y resultados insatisfactorios aún más acentuados con la pandemia de la COVID-19, este artículo describe y analiza, desde una perspectiva de género, el liderazgo pedagógico de un conjunto de escuelas católicas salesianas de 21 países del continente, considerado por su relevancia como un factor de primer orden para la mejora de los aprendizajes. Para ello se realizó una investigación de carácter cuantitativo a través de la aplicación de la técnica del cuestionario, con una muestra probabilística y estratificada que abarcó a 330 directores/as. Entre los principales resultados encontramos el predominio del liderazgo escolar femenino (66.7%) y prácticas de enfoque pedagógico más consolidadas en las mujeres que ejercen este rol, tales como: supervisión y monitoreo de la práctica docente, cultura colaborativa para el desarrollo profesional y toma de decisiones orientada a la enseñanza y el aprendizaje. Se constatan otras prácticas que requieren mayor impulso y formación en el conjunto de los directores y sus equipos.

Palabras clave: mujer y desarrollo, gestión educacional, escuelas confesionales, liderazgo pedagógico, análisis bivariado.

The purpose of this research is to have an approach to the characteristics of pedagogical leadership exercised by people in leadership positions in Salesian schools in America, considering the relevance achieved by this approach and its relevance for the Latin American context (Bolivar, 2010; Murillo, 2007; Pont et al., 2008). For Salesian schools, the challenge of overcoming inequalities and narrowing educational gaps throughout the continent leads them to initiate research processes regarding their extensive presence in 25 countries of the Americas and the factors that influence the quality of education. Among these, school leadership is one of the most important factors, especially when it contributes to the transformation of educational organizations into learning communities (Montecinos and Cortez, 2015).

In the same vein, this study has placed significant value on female school leaders, since their capacity to influence and practice leadership in schools in the Americas accounts for a much higher percentage than that of men (Weinstein et al., 2014). In turn, several international studies on women and educational leadership acknowledge the need to continue including the gender variable in research on this topic, to shed light on the possible symptoms of discrimination and inequality faced by women in the workplace, in order to implement solutions to the problem (Cárdenas de Sanz, 2017; Castro et al., 2021; Rivera-Mata, 2013).

In the relentless quest to achieve good student learning, and after decades of promoting major external educational reforms, there is now consensus on the limited capacity they have had to significantly transform the educational reality (Fullan 2002; Loyo, 2019). On the contrary, the capacity to make their own decisions as a school and to establish pedagogical direction become powerful devices for schools to provide organizational responses in accordance with the demands of their respective contexts. Hence, the educational or pedagogical leadership of school management and management teams acquires the character of a critical factor of the first order (Bolívar, 2019).

The multifaceted educational scenario in Latin America has been characterized by a search for practices that make it possible to achieve quality learning, thus allowing students to overcome the margins of inequality so deeply rooted in the continent. The recognition that school leaders play a highly relevant role in raising the quality of teaching and learning has generated significant interest in offering adequate preparation for the exercise of school management leadership, based on policies aimed at strengthening school leaders (Weinstein et al., 2015). Several innovative programs that have been developed in Latin American countries have acquired new leadership approaches, such as pedagogical, transformational, and distributed leadership, while moving from a leadership focused on administration or a bureaucratic approach to schools to a leadership for change and continuous improvement (Murillo, 2006).

On the other hand, it is noted that female leadership is undergoing major paradigm shifts. Women have been positioning themselves as capable of making decisions in various areas of their personal and professional lives, as well as performing in multiple areas (Güezmes et al., 2022). However, in relation to the educational scenario, various studies confirm that, despite the progress and feminization of education, women's entry into management positions is lower compared to men (Carrillo, 2017; Cruz-González et al., 2020; Padilla, 2018).

In Latin America, however, the evidence showing a high presence of women in management positions is consistent (Murillo and Román, 2013; Weinstein et al., 2014), which some identify as a “continent of empowered women” (Cárdenas de Sanz, 2017:13), thus corroborating that female leadership has a broad capacity to face challenges, especially in contexts of change, encouraging flexibility and adaptability in the face of continuous transformations (Navarro et al., 2018).

The relevance of pedagogical leadership for improving the quality of schools in Latin America supports the importance and the need to continue to deepen this topic from a gender perspective, which although the amount of research in the region has increased, it is still insufficient (García and Martínez, 2019).

■ Approaches to Pedagogical Leadership

Pedagogical leadership has been developed by two major traditions with diverse approaches and objectives. The first refers to a type of “instructional leadership” of North American origin (Bush and Glover, 2014; Coughlin and Baird, 2013; Farnsworth, 2015), which has assumed that the critical focus of attention on the part of leaders is the behavior of teachers and their relationship to activities that directly affect student learning; the other, in contrast, that of “learning-centered leadership” (Hallinger and Heck, 2010; Leithwood et al., 2006; Robinson, 2011; Robinson et al., 2009), integrates instructional leadership with transformational leadership, which focuses on incorporating a broad spectrum of leadership actions to sustain learning and its outcomes (Hallinger, 2010; Lewis and Murphy, 2008).

Currently, school leadership is gaining momentum as leadership for learning or learning-centered leadership (learning-centered leadership). In the words of Robinson (2017:45) “the essence of learner-centered leadership is the permanent focus on the consequences that the decisions and actions of leaders have on the students for whom they are responsible.” That is, a critical connection is made between the exercise of leadership with student learning. This could be obvious, since the purpose of schools is precisely learning and school leadership should be based on it; however, we can question why something that should be obvious is novel in today's educational contexts. And one possible answer is that leadership has not been directly related to student learning outcomes since it is usually an individual and independent responsibility of teachers and their work in the classroom. That is, school leadership has been radically disconnected from teaching and learning for too long (Robinson, 2011: 8).

Studies on effective schools have systematically shown that one of the main characteristics that make them effective concerns the school director as pedagogical leader. Subsequently, authors such as Barber and Mourshed (2007), Bolívar and Murillo (2017) and Leithwood et al. (2008), have found that the school principal, when exercising pedagogical leadership functions, is the second factor, after classroom teaching, which has the greatest impact on student learning within intra-school factors.

In a study developed by Murillo (2007) in eight Latin American countries, it was found that there is a statistically significant relationship between the time principals devote to tasks related to pedagogical leadership and better performance of students in that school, and between this dedication and the greater satisfaction of teachers with the directorate.

Therefore, school leadership focused on pedagogical (Bolívar, 2012; Leithwood, 2009) and continuous improvement is proving to be an important way to face dilemmas and challenges of increasing complexity, providing a new theoretical lens that makes it possible to reconceptualize and reconfigure the practice of leadership in schools (Murillo, 2006). In the scenario of the health crisis, leading with a focus on teaching and learning has constituted an important demand for the leadership of the system, having to maintain an institutional management attentive to multiple demands.

■ Female Leadership in Education

The Latin American region reveals a high percentage of women linked to education in the Americas, and that has boosted the participation rate in school leadership, above the average of women in management positions in other spheres of social life (Cárdenas de Sanz, 2017).

In recent years, research on female leadership has increased significantly with the aim of evidencing the barriers that women face when facing management positions in the school scenario (Cruz et al., 2020; Cuevas et al., 2014), among which stand out experiences of successful women who are bringing greater visibility to important leadership achievements in large jobs (Malcorra, 2018; Sandberg and Scovell, 2015).

Some reasons that explain the increase of female leadership and positions of power in academia relate to the international agenda of gender equity and female empowerment. However, it is no less true that in these processes marked actions of discrimination in terms of managerial permanence coexist, due to the enduring stereotype of this position, linked more to male optics. This conditions women to reproduce that role (Navarro et al., 2018; Rivera-Mata, 2013).

Female leadership in educational institutions is linked to the involvement of all entities responsible for the organizational system, transferring the commitment obtained around the quality and culture of the organization, i.e., leadership of orientation, motivation, development of empathy, and interpersonal skills. It also includes optimal educational management and its facilitating projection in the community (Martínez and Martínez, 2012). The contribution generated from this type of leadership has shown that women are capable of exercising leadership at different levels, which is a way to move towards breaking hierarchical structures that hinder change in schools and in processes outside them, which is an important contribution to the challenges of the current reality (Cáceres et al, 2012).

According to Bolívar (2019), pedagogical leadership drives the creation of necessary conditions for learning, with a focus on curriculum, pedagogy, providing the educational team with ambitious learning goals for students and school autonomy. Pedagogical leadership is characterized by the importance it gives to teaching practice, focusing on teaching and evaluation, as well as on the professional development of teachers (Montecinos and Cortés, 2015), and in the search for building the best conditions for learning processes; promoting a collaborative culture, minimizing individualistic glimpses in teaching practices (Llorent-Bedmar et al., 2017) and ensuring that decisions regarding management are always driven by teaching and learning (Bendikson et al., 2012).

A study by Carrasco and Barraza (2021) shows that the pedagogical leadership approach, with its peculiarities, is linked to female leadership. It also states that female leaders characteristically work better with others, tending to develop more horizontal and collaborative work environments (Kaiser and Wallace, 2016). However, this approach would not be the only one, as female leadership has several particularities of other types of leadership, such as transformational, distributed, or leadership for social justice. In other words, we are gradually moving from the old concept of “think manager: think man” (Schein, 1973) to revaluating the contribution that female leadership can make to organizations. As various theories and studies on leadership have been developed, it has been shown that female leadership can combine effectiveness, concern for people, influence, inspirational motivation, adaptation to the diverse needs of the context, and cooperation more easily than men (Omar and Davidson, 2001; Wajcman, 1996).

If we currently understand that leadership is impossible without interpersonal influence and group effectiveness, the main focus of leadership today is on achieving the effective relationship between members, evolving from an individual to a collective construction (Rivera-Mata, 2013). In other words, in the social environment of the 21st century, there is no meaningful leadership without the relationships between people, or without considering the various contexts in which leadership unfolds, which are increasingly complex, changing, and interdependent.

■ Salesian School in the Americas and female school leadership

Taking Salesian schools in the Southern Cone as a reference, a study conducted in 2020 (Jiménez et al., 2023)) reveals that out of a total of 300 principals surveyed, 67.3% were women and 32.7% were men. In other words, in the 219 schools that make up this region (Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay), a high percentage is made up of women in management positions. This choice does not seem to be accidental. For the Congregation of the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians, founded by St. John Bosco and St. Mary Mazzarello (1872) in northern Italy and present in 97 countries, the formation and promotion of women is a priority (FMA, 1996; 1997). The Salesian Congregation, for its part, in recent decades has given significant space to the role of women in the educational community (Salesian Congregation, 1996), providing them with opportunities for their professional and personal development. There is also particular commitment of female teachers prepare themselves professionally to take on new challenges, which makes promotion to leadership positions frequent and natural in Salesian schools in America, along with other gender characteristics that are expressed with greater visibility by female leadership, such as the ability to work with others, to promote participatory decisions, sensitivity to their own emotional world and that of others, and passion for education from the ethics of care, that is, a people-centered leadership (Arroyo, 2020; Brescoll, 2016).

■ Pedagogical leadership and pandemic

With the changes in the scenario brought about by Covid-19, the school and its leaders have had to adapt to a new work model, to new challenges and transformations that reveal the need to reflect on the future. Thus, leaders must be able to engage their teams and the entire school community, to take on the challenge of reconfiguring the school, redesigning the conditions to ensure it is implemented.

In relation to women’s leadership in times of pandemic, the UN states that “the leadership style of women leaders in the response to Covid-19 has been described as more collective than individual, more collaboration than competition and more directive than imperative” (Zedník, 2020), important characteristics in a context where the conception of leadership involves resilience, mobilizing human and material resources to achieve shared goals, aggregating capabilities to respond to unexpected events, and staying the pedagogical course in a remote, hybrid, or face-to-face learning ecosystem (Vaillant, 2022).

Although no specific analysis has been found on female pedagogical leadership in times of pandemic, it may be inferred that reacting to the emergency could have been faster, more decisive and effective, due to the fact that female characteristics are more suitable for times of crisis, as demonstrated by the theory of “think crisis - think female” (Gartzia et al., 2012); or as referred by the study of Zenger and Folkman (2021), where women tended to perform better during the crisis and were positively rated with higher statistical significance than men in the first wave of the pandemic.

The objective of this article is to describe and analyze from a gender perspective, the pedagogical leadership that is developed in Salesian schools in the Americas, in order to characterize the reality of the continent and to promote further formative processes of school leaders. Based on the data obtained, it particularly intends to:

a) Describe the results of the pedagogical leadership variables that were addressed.

b) Determine whether there are significant differences in the exercise of pedagogical leadership based on the gender variable.

c) To recognize the practices most consolidated by male and female director in the continent and those that need to be strengthened.

The article is based on the preliminary findings of a doctoral research project on school leadership in Salesian schools in Latin America. This project seeks to improve the current understanding of school leadership practices in this region. The quantitative method has been chosen, through a non-experimental and cross-sectional design.

The study was carried out between April and September 2021, with the participation of 330 principals of Salesian schools, located in urban and rural areas. The population corresponds to a set of about 1000 educational centers in 21 Latin American countries, including the United States only as a general reference.

A random, probabilistic sample was determined, which made it possible to extrapolate and thus generalize the results observed to the accessible population; and from there, to the general population. The type of sampling was also stratified, which was constructed based on the countries that constitute the universe and the number of Salesian schools that exist in each of them, thus forming strata, which were randomly selected through the SPSS statistical program, in proportion to the universe present in each country. Since the population was finite in size, the random sample was calculated considering a correction factor, an estimated error of ±5%, and a 95% confidence level.

The instrument selected for data collection was the Principal Instructional Leadership Rating Scale (PIMRS) by Philip Hallinger (2015), which has been widely used in several studies and doctoral theses. An adaptation was made for Latin American Spanish and Portuguese (Brazil), with expert validation. The questionnaire was applied online through the LimeSurvey platform, with ten variables associated with pedagogical leadership (Table I), each with 5 Likert-type questions and five levels of responses: (1) Almost never; (2) Rarely; (3) Sometimes; (4) Frequently; (5) Almost always.

TABLE I. Variables Associated with Pedagogical Leadership

DEFINE THE SCHOOL’S MISSION |

MANAGE THE INSTRUCTIONAL PROGRAM |

DEVELOP THE SCHOOL’S LEARNING CLIMATE |

Structure school goals Communicates school goals |

Manages the curriculum. Supervises and assesses instruction. Monitors student progress |

Ensures teaching time. Maintains a visible presence in the school. Provides incentives for teachers. Promotes professional development. Encourages learning |

Source: Compiled by the author.

■ Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 28 for Macintosh. The mean scores obtained in each of the categories were calculated to simplify the analysis, as well as bivariate analysis through contingency tables with some questions associated with pedagogical leadership practices compared by sex. Afterwards, the trends in school leadership in Salesian schools in the Americas and the aspects that require improvement in the continent were assessed. It is recognized as a limitation of this study that the analysis responds to the opinions of the participating principals, without a means of control to counteract the possible subjectivity of the responses.

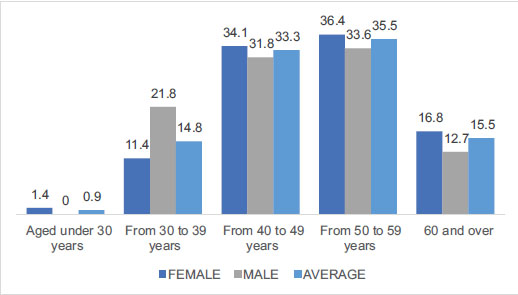

Chart I shows a bivariate analysis with data on the sex and age groups of the participants. Sixty-seven percent of the respondents were women and 33% were men. The age range with the highest percentage is between 50 and 59 years of age (36%), followed by 40 and 49 years of age with 33%.

CHART I. Age Ranges*Gender of Salesian Principals of the Americas (n=330)

Note: Percentages are reported by column. X2 (4) = 7.9, p<0.01.

Source: Compiled by the author.

We can say that in the population surveyed, female principals are twice as many as male principals in general terms (67%), except in the 30-39 age group, where men (21.8%) have a higher percentage than women (11.4%). This shows that Salesian schools are largely led by women throughout the continent.

Regarding gender distribution by country, the countries with the highest percentage of women in school leadership are Honduras, Nicaragua, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Bolivia, Brazil, El Salvador, Ecuador, and Chile (Table II).

TABLE II. Principals distributed by gender and countries (n=330)

|

Sex |

Total |

|

Female |

Male |

||

United States |

57.1% |

42.9% |

100.0% |

Argentina |

59.0% |

41.0% |

100.0% |

Bolivia |

84.6% |

15.4% |

100.0% |

Brazil |

77.6% |

22.4% |

100.0% |

Chile |

71.4% |

28.6% |

100.0% |

Colombia |

52.0% |

48.0% |

100.0% |

Costa Rica |

60.0% |

40.0% |

100.0% |

Ecuador |

72.7% |

27.3% |

100.0% |

El Salvador |

75.0% |

25.0% |

100.0% |

Guatemala |

66.7% |

33.3% |

100.0% |

Honduras |

100.0% |

0.0% |

100.0% |

Mexico |

59.1% |

40.9% |

100.0% |

Nicaragua |

100.0% |

0.0% |

100.0% |

Panama |

50.0% |

50.0% |

100.0% |

Paraguay |

70.0% |

30.0% |

100.0% |

Peru |

55.6% |

44.4% |

100.0% |

Puerto Rico |

100.0% |

0.0% |

100.0% |

Dominican Republic |

91.7% |

8.3% |

100.0% |

Uruguay |

64.3% |

35.7% |

100.0% |

Venezuela |

90.0% |

10.0% |

100.0% |

Bolivia-EPDB |

57.7% |

42.3% |

100.0% |

Note: Bolivia and the Don Bosco Popular Schools (EPDB) are presented separately because the latter corresponds to a set of 300 schools that operate under another management modality and the reading of these data is considered independent for this study.

The study assumes that women principals tend to perform more pedagogical leadership practices when these refer to relational aspects, participation, and ability to work with others, compared to men. Of the variables corresponding to pedagogical leadership, the means were calculated for each group of practices or categories and subsequently, questions were selected from the set of variables that most stand out in this type of leadership: supervision of teaching practice and evaluation; professional development. conditions for the learning process; collaborative culture; decision making oriented to teaching and learning.

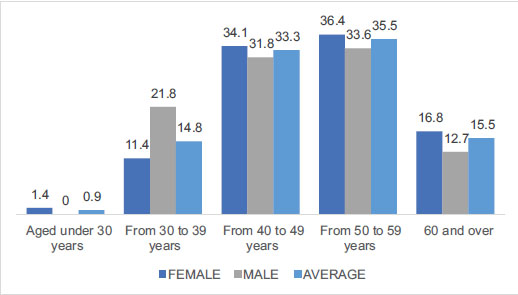

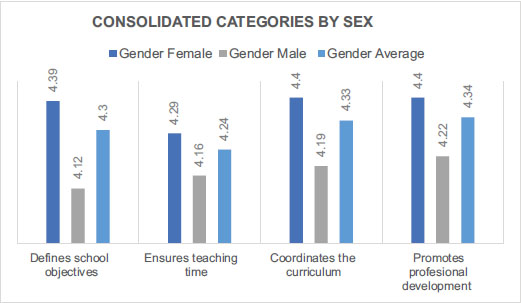

As shown in Table III, in a general overview of the set of variables, it is possible to identify tendencies linked more to female leadership, such as supervision and evaluation of teaching, coordinating the curriculum, monitoring student progress, maintaining a visible presence in the school, promoting professional development, and encouraging learning. In the general result, there are consolidated categories and others that are weaker for all principals (Chart II and III).

TABLE III. Principals’ Average Pedagogical Leadership by Category and Gender (n=330)

Dimension |

Gender |

Total |

|

|

Female |

Male |

|

Structures school goals |

4.40 |

4.22 |

4.34 |

Communicates school goals |

3.99 |

3.85 |

3.95 |

Supervises and assesses instruction |

4.21 |

3.94 |

4.12 |

Manages the curriculum |

4.40 |

4.19 |

4.33 |

Monitors student progress |

4.01 |

3.77 |

3.93 |

Ensures teaching time |

4.29 |

4.16 |

4.24 |

Maintains a visible presence in school |

4.24 |

3.93 |

4.13 |

Provides incentives for teachers |

3.96 |

3.73 |

3.88 |

Promotes professional development |

4.39 |

4.12 |

4.30 |

Encourages learning |

3.90 |

3.61 |

3.80 |

Source: Compiled by the author.

CHART II. Consolidated categories by gender (n=330)

Source: Elaborated by the author.

CHART III. Less established categories

Source: Compiled by the author.

■ Findings on supervision and monitoring of teaching practice

In this set of variables related to classroom teaching practice, the results in Table IV show that female principals carry out this practice more frequently (75.9%) compared to male principals (60.9%). Since these are contingency tables with categorical variables, the Hypothesis of X2. Thus, it is concluded that H0 is rejected and there is 95% confidence that there is a relationship between supervision and assessment of teaching practice and sex (X2 (4) = 11.972, p<0.05). That is, we can affirm that there is a relationship between the gender of the principals with respect to the practice of frequent and informal observation in the classroom; women would be showing with greater evidence the importance they give to the process of supervision and teacher accompaniment.

TABLE IV. Reference to Informal Classroom Observations by Gender of the Principal (n=330)

|

Sex |

Total |

|||

Female |

Male |

||||

Conducts informal observations in the classroom on a regular basis |

Almost never |

Count |

5 |

6 |

11 |

% within sex |

2.3% |

5.5% |

3.3% |

||

Seldom |

Count |

9 |

9 |

18 |

|

% within sex |

4.1% |

8.2% |

5.5% |

||

Sometimes |

Count |

39 |

28 |

67 |

|

% within sex |

17.7% |

25.5% |

20.3% |

||

Frequently |

Count |

88 |

44 |

132 |

|

% within sex |

40.0% |

40.0% |

40.0% |

||

Almost always |

Count |

79 |

23 |

102 |

|

% within sex |

35.9% |

20.9% |

30.9% |

||

Total |

Count |

220 |

110 |

330 |

|

% within sex |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

||

Note: Percentages are reported by column. X2 (4) = 11.972, p < 0.01.

Overall, Salesian schools in the Americas report this practice as frequent and important (70.9%), however, as a whole, it may be an area for improvement.

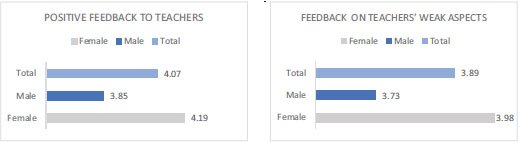

Regarding the feedback of the same process, Table IV shows that there is a relationship between the frequency of this practice and the sex variable, being a practice performed more frequently by women (82.3%) than by men (69.1%). The Hypothesis test rejects H0 and confirms this relationship with 95% confidence (X2 (4) = 13.781, p < 0.01), i.e., there is evidence to infer that, in the Salesian school population, positive feedback is associated with the sex of the principal. In the overall result, 77.8% of the principals systematically carry out this practice.

Regarding the feedback of weaknesses in teachers’ classroom performance, it is observed that female principals (76%) perform this practice more frequently than male principals (68.2%). However, the null hypothesis does not allow us to affirm a significant gender association at 95% confidence with respect to reporting weaknesses in classroom practice to teachers (X2 (4) = 8.917, p>0.05).

At the general level, 73.3% of Salesian school principals carry out this practice. It is of interest to verify which systems are used and which could be implemented to consolidate the feedback from principals to teachers, particularly in the weak aspects.

The following graphs (IV-V) show the averages between both genders for positive feedback and for weaknesses after classroom observation.

CHART IV-V. Feedback to teachers by Principals’ gender (n=330)

Compliled by the author.

Enhancing the professional development of teachers and educators in the school community is a great challenge and a pressing need, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, an important issue is how to promote this dimension to support the acquisition of new skills and tools, in addition to generating a culture of collaborative work.

In response to the question about ensuring that the training carried out by school personnel is consistent with the objectives of the school, it is possible to determine that there is no statistical difference between men and women in this practice, i.e., the implementation of training in Salesian schools in America, is a concern that is not related to the gender of the principals and that is quite consolidated (90.3%), which indicates that there is a focus on the importance of teacher training and that this is related to the objectives of the school (X2 (4)= 6.664, p>0.05).

One aspect that is linked to collaborative culture and the ability to work with others is the achievement of participation of all staff in important school activities. The results show a significant association with the gender of the principals, as shown in Table V, where promoting the participation of all staff in activities is more associated with female principals (92.7%) than male principals (87.2%). Women would be evidencing greater frequency in this practice, at 95% confidence, which is confirmed in the Hypothesis test, although with low intensity (p=0.038).

TABLE V. Staff Participation in the Activities and Incidence by gender of the Principals (n=330)

|

Sex |

Total |

|||

Female |

Male |

||||

Achieves participation in relevant activities |

Rarely |

Count |

3 |

2 |

5 |

% within sex |

1.4% |

1.8% |

1.5% |

||

Sometimes |

Count |

13 |

12 |

25 |

|

% within sex |

5.9% |

10.9% |

7.6% |

||

Frequently |

Count |

95 |

59 |

154 |

|

% within sex |

43.2% |

53.6% |

46.7% |

||

Almost always |

Count |

109 |

37 |

146 |

|

% within sex |

49.5% |

33.6% |

44.2% |

||

Total |

Count |

220 |

110 |

330 |

|

% within sex |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

||

Note: Percentages are reported by column. X2 (3) = 8.433, p< 0.01.

When asked about the time given in work meetings for teachers to share ideas or information about the activities they are carrying out, female principals lead in the frequency of this practice with 88.6% compared to males (76.4%). The hypothesis test allows us to conclude, however, that there is no relationship between these variables at a 95% confidence level. (X2 (3,261) = p >,05).

Another important aspect in the area of Professional Development is to actively support the use in the classroom of skills acquired during the training offered by the school. The results show that 90.6% of the principals of Salesian schools in the Americas frequently carry out this practice, which reflects an important consolidation of this attribute linked to the Professional Development of teachers. In turn, the Chi-square test reveals that there is a significant association at 95% confidence, in that this practice is performed more frequently by women (92.7%) than by men, who only obtain 86.3%. (X2(4) = 16,751, p<0,01).

CHART VI. Time in meetings for teacher collaborative work associated with gender of principals (n=330)

Elaborated by the author. X2(4) = 20.550, p= 0,000.

The results show a higher frequency of female principals (78.6%) compared to male principals (66.3%) in terms of providing professional growth opportunities for teachers. The hypothesis test confirms that there is a relationship between this variable and the sex of the principals, at 95% confidence. (X2 (4) = 15,051, p<0,05).

Therefore, regarding Professional Development in Salesian schools in America, the results show similarity with the theory, confirming that female pedagogical leadership manifests important skills that favor the accompaniment of teaching practice and the creation of conditions to achieve greater professional growth.

■ Conditions for the learning process

Table VI shows the averages obtained by principals in the category of Ensuring teaching time.

TABLE VI. Ensuring teaching time by gender (n=330)

|

Sex |

|

|

Female |

Male |

Total |

|

Ensures that class periods are not interrupted. |

4.54 |

4.29 |

4.45 |

Ensures that students do not leave the classroom during class periods |

4.59 |

4.51 |

4.56 |

Ensures that students who are tardy or absent suffer consequences for missing learning time. |

4.46 |

4.34 |

4.42 |

Encourages teachers to use classroom time to teach and practice new skills and concepts. |

3.54 |

3.56 |

3.55 |

Tries not to let complementary and/or extracurricular activities interfere with the class period. |

4.31 |

4.11 |

4.24 |

Source: Compiled by the author.

In this regard, a weakness observed by the group of principals is related to teaching and practicing new skills and concepts in classroom time (3.55). Teachers need to be accompanied in these processes of teaching innovation, which is also related to the permanent capacity to learn new skills, tools and concepts. Considering the value of classroom time, it is necessary to take advantage of and adequately organize what is done there, and principals can play a key role in this by permanently motivating teachers and creating the conditions for them to put the acquired knowledge into practice.

The next set of questions, related to collaborative culture and decision making, shows the trends observed in the sample (n=330).

Collaborative culture and decision making oriented to teaching and learning obtain a good evaluation in general terms. The association between sex of principals and the questions described above shows that there is a statistically significant relationship when these functions are performed by women only in the case of question 2.3 “consults the school’s academic objectives with teachers when making curricular decisions.” (X2(4) = 15.633, p<0.01).

TABLE VII. Collaborative culture and teaching and learning-oriented decisions by principals’ gender (n=330)

|

SEX |

|

|

FEMALE |

MALE |

TOTAL |

|

1.3 Uses needs assessment or other formal and informal methods to ensure staff contribution to the development of objectives. |

4.2 |

4.0 |

4.2 |

2.2 Discusses the school’s academic objectives with teachers in working meetings with them. |

4.5 |

4.2 |

4.4 |

2.3 Consults the school’s academic goals with teachers when making curricular decisions. |

4.3 |

4.0 |

4.2 |

3.2 Considers student learning outcomes to evaluate teaching. |

4.5 |

4.3 |

4.4 |

7.2 Visit classrooms to meet and share school issues with teachers and students. |

4.4 |

4.2 |

4.3 |

Source: Compiled by the author.

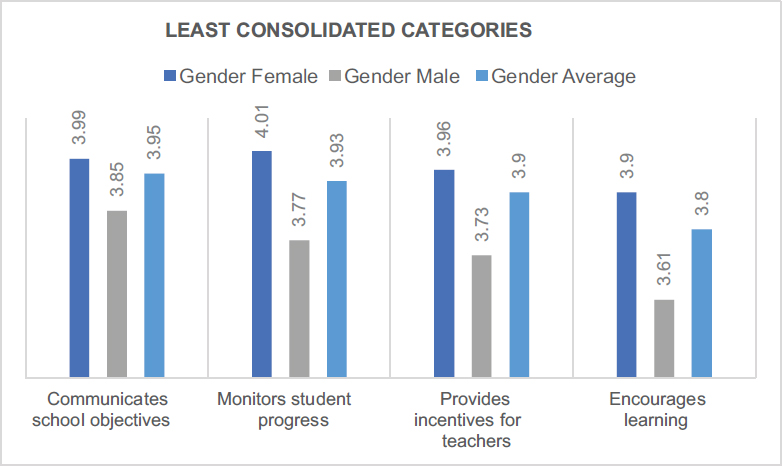

The results obtained, which represent Salesian schools in the Americas in 21 countries, show important strengths in terms of the ability to define the school’s objectives (4.34); coordination of the curriculum (4.33); promoting professional development (4.30) and ensuring teaching time (4.24). All of these are of great importance in the exercise of pedagogical leadership centered on learning.

The set of variables explored to establish pedagogical leadership (Table I) show that, in this group of schools in the Americas, it is possible to observe a growing model of pedagogical leadership focused on learning, whose educational purposes include: setting educational goals, planning the curriculum, evaluating teachers, and teaching and promoting teacher professional development (Hallinger, 2005; Robinson et al., 2009).

Aspects that require attention are those related to encouraging learning (3.80); providing incentives for teachers (3.88); monitoring student progress (3.93) and communicating school objectives (3.95). In other words, the functions linked to the management of the teaching program according to Hallinger, in the case of these results, show strengths in terms of curriculum management and in the supervision and evaluation of teaching; however, it is necessary to strengthen the monitoring of the progress made by students with respect to their learning process.

Consequently, it is necessary to promote a leadership style that distributes responsibilities and empowers intermediate leaders to promote learning. Likewise, understanding the school as a Professional Learning Community and generating spaces for it may constitute one of the great strategies for substantive school improvement, strengthening teacher leadership and their ability to build together learning for teaching (Bolivar, 2012; 2019).

In terms of defining the school’s mission, the communicational aspect (3.95) requires improvement, along with those items that favor the development of the learning climate: providing incentives to teachers (3.88) and encouraging learning (3.80), both aspects related to strengthening motivation in teachers and students.

Regarding pedagogical leadership, we see that in this set of schools, strong female leadership is exercised, in which the theory about their affinity is corroborated in various categories and functions, highlighting a significant association when these are performed by women (Carrasco and Barraza, 2021).

Other aspects, such as the visibility of the principal in the school, appear as a greater challenge for men (3.93) than for women (4.24); or the supervision and evaluation of teaching, presents more favorable results for female principals (4.21) than for male principals (3.94).

It is worth noting that female principals have a higher frequency in the various practices evaluated, even though this does not necessarily imply a statistically significant relationship. It could be interpreted “between the lines”, that there is a significant empowerment of women in Latin American education, as stated by Cárdenas (2014).

As a general conclusion, this approach to pedagogical leadership has allowed, on the one hand, to characterize the most consolidated dimensions and those that should be promoted more strongly by Salesian schools in America to achieve quality learning, thus opening an opportunity for exchange between countries and regions to share good practices and leadership experiences among their principals and management teams.

It has also made evident the strong female pedagogical leadership that is being developed in the continent, showing promising results for the development of a leadership focused on learning, which allows valuing and projecting this approach as a shared and complementary experience among principals, opening the possibility for future research to give continuity to these findings. The pedagogical leadership approach finds various links with the Salesian educational proposal, so it is desirable to further reflect on the elements and characteristics that make this type of leadership, a concrete operational form of developing a Salesian leadership in the school.

At a crucial time for making decisions regarding the future of post-pandemic education, the transformation that presses for a profound change, capable of generating a better connection between school practice, social demands, and the needs of students in the society of the 21st century, is mostly in the hands of Latin American women. It is possible to affirm, therefore, that school leadership with a female face constitutes an opportunity: “Think crisis - Think female”.

Finally, the practices associated with female leadership constitute a learning opportunity for principals as a whole, especially in terms of the competencies that ensure learning. Therefore, considering the presence of female leadership could further enrich the work of management teams, whether in the management role or in intermediate leadership directly linked to pedagogy.

Arroyo, D. (2020). Liderazgo de mujeres en la educación: una perspectiva desde las lideres escolares chilenas. Revista INTEREDU, 3(2), 9–32. https://bit.ly/3S73a4f

Barber, M. & Mourshed, M. (2007). Cómo hicieron los sistemas educativos con mejor desempeño para alcanzar sus objetivos. https://mck.co/3qW6t1l

Bendikson, L.; Robinson, V. & Hattie, J. (2012). Principal instructional leadership and secondary school performance. Set: Research Information for Teachers, 1, 1–8. https://bit.ly/3oDyM3W

Bolívar, A. (2010). ¿Cómo un liderazgo pedagógico y distribuido mejora los logros académicos? Revisión de la investigación y propuesta. Magis, Revista Internacional de Investigación en Educación, 3 (5), 79–106. https://bit.ly/35WLFvT

Bolívar, A. (2012). Políticas actuales de mejora y liderazgo educativo. Archidona, Málaga. Ediciones Aljibe.

Bolívar, A. (2019). Una dirección escolar con capacidad de liderazgo pedagógico. Editorial La Muralla.

Bolívar, A., & Murillo, J. (2017). Mejoramiento y liderazgo en la escuela. Once miradas. CEDLE; Santiago de Chile, (p. 71–79).

Brescoll, V. (2016). Leading with their hearts? How gender stereotypes of emotion lead to biased evaluations of female leaders, The Leadership Quarterly, 27(3), 415–428.

Bush, T. & Glover, D. (2014). School leadership models: what do we know? School Leadership y Management, 34:5, 553–571, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2014.928680

Cáceres, M., Trujillo. J., Hinojo, F., Aznar, I., & García, M. (2012). Tendencias actuales de género y el liderazgo de la dirección en los diferentes niveles educativos. Educar, 48(1), 69–89.

Cárdenas de Sanz, M. (2017). En busca del liderazgo femenino: el recorrido de una investigación. Ed. Bogotá, D. C. Colombia: Universidad de los Andes, 2017.

Carrasco, A. & Barraza , D. (2021). Una aproximación a la caracterización del Liderazgo Femenino. El caso de directoras escolares chilenas. RMIE, 26(90), 887–910. https://bit.ly/3cDj329

Carrillo, N. (Ed.). (2017). Género y poder: ¿por qué no hay mujeres directivas? Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. https://bit.ly/3OK3S4M

Castro, M., Mosteiro, M., & Porto, A. (2021). El liderazgo educativo desde una perspectiva de género. In M. Santos Rego, M. Lorenzo Moledo, Anaïs Quiroga Carrillo (Eds.). La educación en Red. Realidades diversas, horizontes comunes, (p. 803). Universidad de Compostela.

Congregación Salesiana. (1996). Actas Capítulo General XXIV. Salesianos y Seglares, compartir el espíritu de la misión. https://bit.ly/3ztBcau

Coughlin, A., & Baird, L. (2013). Pedagogical leadership. Ontario: Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

Cruz-González, C., Lucena, C., & Domingo, J. (2020). Female principals and leadership identity. A review of the literature. The International Journal of Organizational Diversity, 20, 45–58.

Cuevas, M., García, M., & Leulmi, Y. (2014). Mujeres y liderazgo: Controversias en el ámbito educativo. Journal for Educators, Teachers and Trainers, 5(3), 79 – 92.

Farnsworth, S. (2015). Principal learning-centered leadership and faculty trust in the principal. Brigham Young University.

FMA (Instituto Hijas de María Auxiliadora). (1996). Actas del Capítulo General XX. “A ti te las confío”.

FMA (Instituto Hijas de María Auxiliadora). (1997). Promoción de la mujer. https://bit.ly/3beg4gf

Fullan, M. (2002). Las fuerzas del cambio. Explorando las profundidades de la reforma educativa. Ediciones Akal.

García-Garnica, M., & Martínez-Garrido, C. (2019). Dirección escolar y liderazgo en el ámbito Iberoamericano. Revista Profesorado, 23(2). https://bit.ly/3oyI1m3

Gartzia, L., Ryan, M., Balluerka, N., & Aritzeta, A. (2012). Think crisis–think female: Further evidence. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 21:4, 603–628, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2011.591572

Güezmes, A., Scuro, L., & Bidegain, N. (2022). Igualdad de género y autonomía de las mujeres en el pensamiento de la CEPAL. El Trimestre Económico, vol. LXXXIX 1(353), 311–338. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20430/ete.v89i353.1416

Hallinger, P. (2005). Instructional leadership and the school principal: A passing fancy that refuses to fade away. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 4, 221–239.

Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. (2010). Leadership for learning: Does collaborative leadership make a difference in school improvement? Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 38(4), 654–678.

Hallinger, P., Wang, W., Chen, C., & Li, D. (2015). Assessing instructional leadership with the principal instructional management rating scale. Springer.

Jiménez, A., Garay, S., & Parraguez, P. (2023). Diagnóstico de las competencias de liderazgo escolar en directivos salesianos. Revista Alteridad, 18(2), 222–233. https://doi.org/10.17163/alt.v18n2.2023.06

Kaiser, R., & Wallace, W. (2016). Gender bias and substantive differences in ratings of leadership behavior: toward a new narrative. Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 68(1), 72–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000059

Leithwood, K. (2009). ¿Cómo liderar nuestras escuelas? Aportes de la Investigación. Santiago de Chile: Fundación Chile.

Leithwood, K., Day, C., Sammons, P., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2006). Successful school leadership what it is and how it influences pupil learning. Nottingham: Research Report 800.

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2008). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. School Leadership and Management, 28(1), 27–42

Lewis, P., & Murphy, R. (2008). New directions in school leadership. School Leadership & Management, 28(2), 127–146.

Llorent-Bedmar, V., Cobano, V., & Navarro, M. (2017). Liderazgo pedagógico y dirección escolar en contextos desfavorecidos. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 75(268), 541–564.

Loyo, A. (2019). ¿Qué queda hoy de la gran ola de reformas educativas de los años noventa en América Latina? Gaceta de la Política Nacional de Evaluación Educativa en México, 4(12). https://bit.ly/3CXdMxJ

Malcorra, S. (2018). Pasión por el Resultado. Ed. Paidós.

Martínez-Uribe, U., & Martínez-Chaparro, A. (2012). Aproximación al perfil psicosocial de las mujeres líderes del programa “Familias en Acción” del Municipio de Bello. Pensando Psicología. 8(14), 118–129. http://bit.ly/3Hdt1oj

Montecinos, C., & Cortez, M. (2015). “Experiencias de desarrollo y aprendizaje profesional entre pares en Chile: implicaciones para el diseño de una política de desarrollo docente”, Docencia, 55(mayo) 52–61.

Murillo, F. (2006). Una dirección escolar para el cambio: del liderazgo transformacional al liderazgo distribuido. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, vol. 4, (4), 11–24.

Murillo, F. (Coord.). (2007). Investigación iberoamericana sobre eficacia escolar. Bogotá: Convenio Andrés Bello.

Murillo, F., & Román, M. (2013). La distribución del tiempo de los directores y de las directoras de escuelas de Educación Primaria en América Latina y su incidencia en el desempeño de los estudiantes. Revista de Educación, 361. DOI: https://doi.org/10-4438/1988-592X-RE-2011-361-138

Navarro, J., Vergara, M., & Eljach, M. (2018). Liderazgo femenino en el escenario educativo: un fundamento para posibles intervenciones psicoterapéuticas y sociales. Revista AVFT, 37(5), 489–494.

Omar, A., & Davidson, M. (2001), Women in management: A comparative cross-cultural overview. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 8(3/4), pp. 35–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527600110797272

ONU Mujeres (Entidad de las Naciones Unidas para la Igualdad de Género y el Empoderamiento de las Mujeres). (2020). COVID-19 y liderazgo de las mujeres: Para responder con eficacia y reconstruir mejor. http://bit.ly/3VCXws0

Padilla, M. (2018). Opiniones y experiencias en el desempeño de la dirección escolar de las mujeres en Andalucía. RELIEVE, 14(1), 1–27. https://bit.ly/3OFmliy

Pont, B., Nusche, D., & Moorman, H. (2008). Improving school leadership. Paris, OCDE. http://www.oecd.org/edu/schoolleadership

Rivera-Mata, J. (2013). Liderazgo, mujer y sociedad en América Latina. Ed. Lima: Universidad del Pacífico, 2013.

Robinson, V. (2011). Student-centered leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Robinson, V. (2017). Hacia un fuerte liderazgo centrado en el estudiante: afrontar el reto del cambio. In J. Weinstein (ed.), Liderazgo educativo en la escuela: Nueve miradas, 45–80. Santiago, Ediciones Universidad Diego Portales.

Robinson, V., Hohepa, M., & Lloyd, C. (2009). School leadership and student outcomes: Identifying what works and why. Best evidence synthesis iteration [BES]. Wellington.

Sandberg, S., & Scovell, N. (2015). Vamos Adelante (Lean in). Las mujeres, el trabajo y la voluntad de liderar. Londres: wh Allen.

Schein, V. (1973). The relationship between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 57(2), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037128

Vaillant, D. (2022). El día después en Latinoamérica: Pensar el liderazgo educativo en escenarios de incertidumbre. In A. Bolívar, G. Muñoz, J. Weinstein and J. Domingo (Coords.). Liderazgo Educativo en Tiempos de Crisis. Aprendizajes para la escuela post COVID. (pp. 59–74). Universidad de Granada.

Wacjman, J. (1996). The Domestic Basis for the Managerial Career. The Sociological Review, 44(4), 609–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1996.tb00439.x

Weinstein, J., & Hernández, M. (2014). Policies to improve the leadership of School Principals in Chile: A comparison against other Latin American school systems. Psicoperspectivas, 13(3), 52–68. https://bit.ly/3zTATXK

Weinstein, J., Hernández, M., Cuellar, C., & Flessa, J. (2015). Liderazgo escolar en América Latina y el Caribe. Experiencias innovadoras de formación de directivos escolares en la región. OREAL/UNESCO Santiago. https://bit.ly/3PJHHgb

Zednik, R. (2020). “A Shaken World Demands Balanced Leadership”. Medium, 15 de abril. http://bit.ly/3OZHUfE

Zenger, J., & Folkman, J. (2021). Research: Women Are Better Leaders During a Crisis. http://bit.ly/3P1Y73S

Contact address: Patricia Lorena Parraguez Núñez. Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca, escuela doctorado. P.º de Canalejas, 38, 54, 37001, Salamanca, Spain. E-mail: plparragueznu.chs@upsa.es