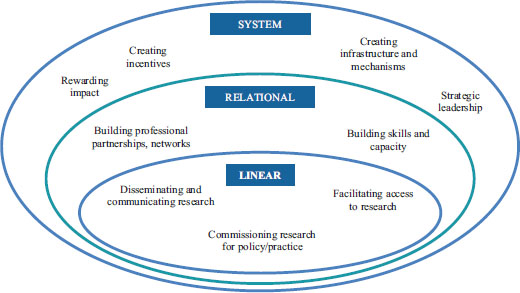

FIGURE I. Embedded models of knowledge mobilisation with examples

Source: Adapted from (Boaz, Oliver, & Hopkins, 2022).

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2023-400-571

Nóra Révai

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2045-6203

Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos

Jordan Hill

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8742-0494

Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos

José Manuel Torres

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6366-7759

Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos

Abstract

Using evidence well and systematically is fundamental for improving the learning experience and outcomes of all students and ensuring equity in education. Despite enormous effort and investment to reinforce the quality, production and use of education research, using evidence in policy and practice remains a challenge for many countries and systems. This paper reports on the findings of an OECD study that mapped actors and mechanisms facilitating the production and use of research in education systems. Data was collected from ministries of education in 37 systems representing 29 countries through a survey and follow-up interviews. This paper focuses specifically on research use in policy making. Findings depict a wide range of actors that facilitate research use. While respondents reported various research mobilisation mechanisms, these focus primarily on linear research transfer and relationship building. Only a minority of countries have a systems approach. Based on an analysis of reported actors, mechanisms and barriers, the paper concludes that in many systems the current set of mechanisms is not sufficient to achieve a systematic use of evidence in policy. What seems to be missing is an acknowledgement of the complexity of evidence systems and an appropriate system-level coordination of this.

Keywords: knowledge mobilisation, evidence-informed policy, knowledge intermediaries, education research, politics of education.

Resumen

Utilizar la evidencia educativa de manera correcta y sistemática es fundamental para mejorar la experiencia de aprendizaje de todo el alumnado y garantizar la equidad en educación. A pesar de los enormes esfuerzos e inversiones para reforzar la calidad, producción y uso de la investigación educativa, el uso de la evidencia en políticas públicas y la práctica escolar sigue siendo un reto para muchos países y sistemas educativos. Este artículo presenta las conclusiones de un estudio realizado por la OCDE en el que se han identificado los actores y mecanismos que facilitan la producción y el uso de la investigación en los sistemas educativos. Los datos se recopilaron de los ministerios de educación de 37 sistemas que representan a 29 países a través de una encuesta y entrevistas de seguimiento. Este artículo se centra específicamente en el uso de la investigación en la elaboración de políticas educativas. Los resultados muestran un amplio abanico de agentes que facilitan el uso de la investigación. Aunque los encuestados informaron de diversos mecanismos de movilización de la investigación, estos se centran principalmente en la transferencia lineal de la investigación y el establecimiento de relaciones entre los actores. Solo una minoría de países aplica un enfoque sistémico. A partir del análisis de los agentes, mecanismos y obstáculos señalados, el documento concluye que, en muchos sistemas, el conjunto actual de mecanismos no basta para lograr un uso sistemático de evidencia en políticas públicas. Lo que parece faltar es un reconocimiento de la complejidad de los sistemas de evidencia y una adecuada coordinación holística.

Palabras clave: movilización del conocimiento, política basada en evidencia, intermediarios del conocimiento, investigación educativa, política de la educación.

Using research more systematically to improve public services has become a policy imperative in the past two decades (Powell, Davies, & Nutley, 2017). In education, a thoughtful and systematic use of evidence is fundamental for improving the learning experience and outcomes of all students and ensuring equity. It is also critical to ensure that education remains relevant for societal needs and that education systems are efficient.

In 2000, the OECD’s Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) highlighted that the rate and quality of knowledge creation, mediation and use in the education sector was low compared with other sectors (OECD, 2000). CERI’s work on knowledge management and educational R&D also showed generally low levels of investment in educational research as well as in research capacity, especially in quantitative research. Links between research, policy and innovation were judged as weak in many OECD systems (OECD, 2003).

In the 2007 OECD volume Evidence in Education, experts and politicians formulated a number of challenges to stronger evidence use in decision making, including:

With the spread of the evidence-informed movement in education, three main trends can be observed in the past two decades.

First, many countries have invested in research itself. Although public spending on educational research and development (R&D) is still limited compared to other sectors such as health (OECD, 2019), significant funding has gone into experiments, systematic reviews and other forms of education research (OECD, 2007). Second, there has been growing investment in initiatives intended to facilitate the use of research. These include establishing dedicated brokerage institutions designed to mediate research for policy and practice (OECD, 2007), and making research more accessible to users through funding research syntheses, toolkits and various initiatives that aim to strengthen engagement with research. Third, research on evidence-informed policy and practice has also been expanding. Early conceptualisations of knowledge transfer as a linear process have evolved into an understanding of research ecosystems that recognise complexity (OECD, 2016; Boaz & Nutley, Using evidence, 2019; Best & Holmes, 2010). There are a growing number of studies looking at various brokerage initiatives, with some recent efforts exploring how these initiatives work and can be improved (Oliver, Hopkins, Boaz, Guillot-Wright, & Cairney, 2022; Gough, Maidment, & Sharples, EPPI-Centre, 2018).

Despite widespread investment since the early 2000s, to date, there is no strong evidence about how we can effectively strengthen the use of research in decision making. The positive trends mentioned above, coupled with a continuing dissatisfaction of many actors about the unfulfilled promise of evidence-informed policy and practice, call for establishing a state of the art in this matter. Exploring countries’ strategies to facilitate research production and use, and the barriers policy makers, researchers, practitioners and other actors are still facing in integrating evidence into educational policy and practice is a first step. Understanding how these strategies work and what impact the various brokerage efforts are making would be the second step, and a fundamental piece towards improving evidence use.

This paper1 reports on the findings of a recent OECD survey conducted in CERI’s Strengthening the Impact of Education Research project2. We first present the research questions and methodology, and then provide an analysis of the landscape of actors and mechanisms that facilitate research use in policy in OECD systems. We conclude with a short discussion of the findings and future areas of research.

The first step in addressing the questions above is to map existing mechanisms, actors and challenges across systems. In particular, we will investigate the following questions:

The OECD conducted a policy survey from June to September 2021 to collect data on various aspects of facilitating research use in countries/systems. It consisted of three parts: 1) aspects of facilitating research use in policy, 2) aspects of facilitating research use in (school and teaching) practice, and 3) aspects of research production. In this paper, we analyse data on actors and mechanisms with respect to research mobilisation in policy making (part 1 of the survey) and reflect on these mechanisms in light of literature on knowledge mobilisation.

The survey consisted of different question formats, including single and multiple choice (selecting one or several from a number of options), Likert scale (5-point), ranking and open-ended questions. The survey allowed for a wide and flexible interpretation of key concepts such as “research”, “policy maker”, “facilitating research use” and “activeness”. The choice of not setting narrow definitions was made to capture broad perceptions of respondents. As a follow-up to the survey, six countries3 were selected for further data collection through semi-structured interviews. The interviews confirmed certain differences in interpreting concepts (e.g., who policy makers are, whether research refers primarily to large scale data, experimental designs or is considered more broadly). Therefore, comparisons between systems should be made with caution. Nevertheless, the range of interpretations are all relevant to knowledge mobilisation and thus valid when discussing actors, mechanisms and barriers.

Overall, 37 education systems from 29 countries4 have responded to the survey. Responses represent the perspective of ministries of education at the national or sub-national (state, province, canton, etc.) level. Thus, data reflects the perceptions and personal realities of personnel within these ministries. It is important to recognise that this is limited perspective of the actors and mechanisms that operate in the research production, mediation and use space, as well as of the barriers to increasing research use. Nevertheless, this perspective is fundamental to understanding the use of evidence in policy making.

The survey targeted the highest level of decision making in education (ministry/department of education). In federal systems, this corresponds to the state (province, canton, etc.) department, although some such systems, such as Austria and Spain decided to respond at the federal (national) level. Ministries were asked to coordinate the response across departments. The follow up interviews revealed that ministries of education had various definitions of policy makers. Interviewees most commonly associated the term with high-level ministry officials such as Directors, Deputy Directors and Director Generals. There was overall a high degree of recognition that policy makers are those with influence over the policy process, rather than those tasked with implementation of policies. Some systems however took a broader view, considering all those working at the ministry of education, as well as individuals in the executive and legislative branches of government. As a result of the different understandings, comparisons between systems in policy survey data should be made with caution.

The evidence-informed policy and practice movement gave rise to a rich field of study looking into the dynamics of knowledge. Terms such as knowledge management, knowledge-to-action, knowledge translation, transfer, mobilisation, brokerage and mediation consider the dynamics of knowledge from different angles (Levin, 2008). A major development in conceptualising the interplay of research production and use is an evolution from linear to system models. Best and Holmes (2010) describe the three models of knowledge mobilisation in a nested perspective:

In both the relationship and systems models, a strong emphasis is placed on mediation, i.e., intermediary actors and processes that bridge the gap between communities of research producers and users. Intermediary actors include organisations (e.g., brokerage agencies) and individuals (e.g., translators, brokers, gatekeepers, boundary spanners and champions). While each actor is important in a systems view, this view implies that all actors together shape the research ecosystem through their interactions, feedback loops and co-creation (Campbell, Pollock, Briscoe, Carr-Harris, & Tuters, 2017).

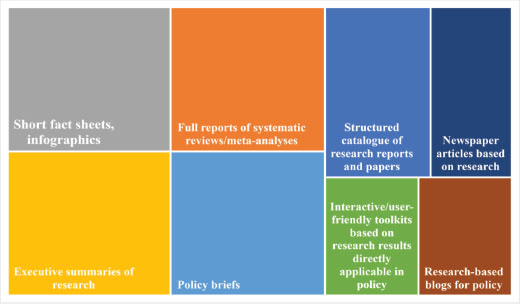

This development should not be seen as a simple shift from one model or strategy to another. Linear processes of knowledge transfer are not outdated; rather, they are embedded in more complex dynamics and remain key building blocks of research use. Relationships are fundamental elements of a systems view but it is not sufficient to only consider and foster partnerships. Strengthening the dynamics of research production and use is not simply about transferring and translating a narrow set of “codes” from one community to the other. The research presented in this paper is built on an embedded understanding of the linear, relational and systems approaches (Figure I).

FIGURE I. Embedded models of knowledge mobilisation with examples

Source: Adapted from (Boaz, Oliver, & Hopkins, 2022).

The systems view recognises the complex interactions not just between multiple actors, but also multiple sources and types of knowledge (Langer, Tripney, & Gough, 2016; Van De Ven & Johnson, 2006). These include formal research knowledge as well as practitioners’ and policy makers’ professional knowledge, such as their understanding of the context (e.g., of a classroom, policy processes) and how various elements interact within this. Recent conceptualisations see evidence use as “thoughtful engagement with research” (Rickinson, Walsh, Cirkony, Salisbury, & Gleeson, 2020), through which research evidence is combined with other sources of knowledge. In addition, research and other sources of evidence are often not used directly but they shape attitudes and ways of thinking in indirect and subtle ways (Nutley, Powell, & Davies, 2013). While recognising the above complexities, this research focuses on the actors and mechanisms that facilitate the integration of formal research knowledge (or evidence – these terms are used interchangeably in this paper) in processes of policy making.

Facilitating research use – also referred to as research mobilisation in this paper – is understood broadly to comprise linear, relational and systems mechanisms and activities (as exemplified in Figure I) that support the use of research evidence in policy. Though important for a deep understanding of knowledge mobilisation, a discussion on the nature of research (its quality, methodology and inherent assumptions that may sometimes be political and ideological) and its production (drivers, actors, processes) is beyond the scope of this paper. Similarly, the paper does not discuss research mobilisation in school and teaching practice. For these analyses, see OECD (2022).

To operationalise these models in light of the research questions, we have focused on mapping actors that can play a role in the evidence ecosystem, key elements of relationships, and mechanisms and barriers. While the analytical framework for the policy survey includes a more comprehensive set of dimensions developed based on an extensive review of the literature (OECD, 2022), this paper focuses only on organisational actors and mechanisms that facilitate research use.

The first question of this paper asks how we can characterise the actors that facilitate the systematic use of education research in policy. This section first discusses the density and overall activeness level of actors facilitating research use in policy across OECD systems. It then delves into the role of various organisational actors and provides some qualitative analysis of the profiles of brokerage organisations.

In the early years, literature on knowledge management in education focused on three main groups: researchers, policy makers and practitioners. However, education systems are complex systems in which a multitude of actors interact at multiple levels (Burns, Köster, & Fuster, 2016). Beyond the traditional actors, relevant stakeholders include funders of research, textbook publishers and EdTech companies, think tanks and networks of researchers and practitioners, the media and students (Burns, Köster, & Fuster, 2016). These actors may all potentially play their parts in knowledge mobilisation.

To reflect this complexity, the survey asked respondents how active various actors (from a list of 17 actors altogether) were in their systems on a scale from 1 to 5 – not active at all, slightly active, moderately active, active and very active – in three areas: producing research, facilitating research use in policy and facilitating research use in practice (these last two also referred to as “research mobilisation”).

Survey data revealed that a large number of different organisations are seen as active to some degree in all three areas in each of the respondent systems (Table I). However, education systems vary in terms of their overall levels of activity (Figure II).

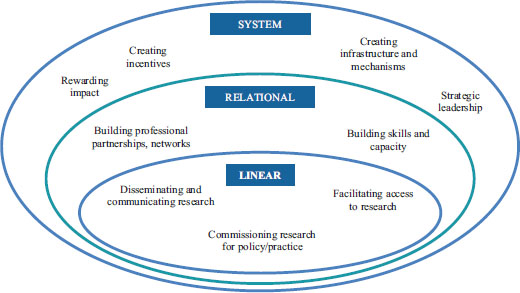

FIGURE II. Number and average activeness of organisations that facilitate research use in policy making

Note: The X axis shows the number of organisations that are perceived as at least slightly active in facilitating research use in policy. The Y axis is the average activeness of these organisations.

Source: OECD Strengthening the Impact of Education Research policy survey data.

Most systems reported a relatively high number of organisations with high activity level on average, with Finland being the most extreme (top right quadrant). Spain is also in this quadrant, reporting 12 organisations active, one (universities) very active and one (teacher education institutions) moderately active (Table V). Some reported a high number of organisations that facilitate research use in policy, but overall less actively (bottom right quadrant). This was the case for South Africa, the Slovak Republic, Austria and Switzerland (Zurich) for example. The concentration of systems on the right end of the chart suggests that research mobilisation is highly decentralised in most countries. In some of these systems, the ministry perceives research mobilisation as strong overall (high level of activeness), in others slightly weaker (medium to low activeness).

Only very few systems reported a significantly lower number of organisations. This is the case for Japan, where the Ministry of Education is the only actor reported. The follow-up interview helped clarify that while the Ministry perceives its own role as central in seeking out the research evidence they need for their policy processes, other actors also support evidence-informed policy. Notably, the National Institute for Educational Policy Research conducts research that supports policy planning and implementation. In Switzerland (St. Gallen), research mobilisation seems to occur between the ministry and teacher education institution(s) – the two actors reported to be very active. Finally, Switzerland (Uri) reported a low number of organisations (5) that are overall not perceived to be highly active (bottom left quadrant), but the ministry and the government funding agency play a central role. These systems may reflect a centralised approach to research mobilisation, in which the ministry itself – with or without one or two agencies – retains the mobilisation function for its own processes. However, it is also possible that the ministry is not aware of other organisations’ role in this field or does not have connections to them and therefore their role in facilitating research use in policy remains limited.

Overall, the data shows that it is not possible to separate research producers, brokers and users: most types of organisations have multiple functions. Research and policy organisations are the most prevalent actors that facilitate the use of research in policy (Figure III). Universities (faculties of education) and the ministries of education themselves were seen as the most active organisations in both the production and mobilisation of education research across the systems (see Table I). The prominent role of research organisations in knowledge mobilisation is not surprising given that policy makers likely perceive them as the most credible research producers and turn to them when they seek out evidence for policy purposes. On the other end of the scale, the media and businesses are not perceived as very active in research mobilisation in most systems, although some have recognised their intermediary roles. This might be because these are not primarily educational actors and may not be seen as main sources of evidence. Although fewer, a number of systems see some of the more practice-oriented organisations, such as teacher education providers and teacher unions, as active in facilitating research use in policy making as well.

FIGURE III. Perceived activeness of actors in facilitating research use in policy

Note: Size reflects the number of systems reporting that the given actor is active or very active in facilitating research use in policy making. See Table I in the Annex for the data on actors seen as very active or active (henceforth “active”) in each of the three areas.

Source: OECD Strengthening the Impact of Education Research policy survey data.

With respect to policy organisations, the key actor is the ministry itself. Some scholars have found that departments and ministries of education are quite weak in knowledge mobilisation (Levin, 2013; Cooper, 2014). However, the presence of “in-house” brokerage units that support particular ministries in research gathering, translation and communication efforts has been reported for some time (OECD, 2007). This type of internal brokerage has become more prominent over the past decade, and in certain national administrations also more formalised through the establishment of strategic intelligence units in ministries of education (Gough, Tripney, Kenny, & Buk-Berge, 2011). Qualitative data confirmed the presence of these research and analysis units in several systems, such as Slovenia, Norway, the Netherlands and Belgium (Flemish community).

Brokerage organisations are not limited to formal brokerage agencies. Data shows that other types of organisations, such as consultancies, think tanks and university-school partnerships also play an intermediary role in a number of systems. Formal brokerage agencies (i.e., agencies with an explicit mission to support the use of research in policy/practice) were reported to exist in 18 systems and were seen as being active to some degree in 16 systems. Only one system (England) reported this agency to be the most active organisation across research production and mobilisation in policy and practice. England has a particularly well-developed brokerage system. In the other 15 systems, such formal agencies often received much lower overall activeness ratings.

Brokerage agencies vary greatly in terms of their profile across systems. Some systems report them to be multi-functional, i.e. active in producing research and facilitating its use in both policy and practice. This was the case for six systems (Costa Rica, Chile, Finland, Norway, Portugal and UK [England]). Others see them as more narrowly-focused: active in only one or two areas. This was the case in seven systems (Columbia, Denmark, Hungary, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland [Obwalden] and Türkiye). New Zealand for example reported them as only active in facilitating the use of research in practice. Interestingly, five systems reported the presence of brokerage agencies, but the ministry perceived them as mostly or entirely inactive in producing research or facilitating its use (Austria, South Africa [Pretoria], Switzerland [Lucerne], Switzerland [Zurich], Switzerland [Appenzell Ausserrhoden]).

Qualitative data collected about formal brokerage agencies revealed a number of additional differences between these. They differ in key organisational characteristics, such as size and funding sources (e.g., charity, government). Brokerage agencies also have different target groups and interlocutors. Some target and interact with the traditional educational stakeholders (e.g., teachers, schools and decision makers). Others have a much broader mandate to build bridges between education, politics and society as a whole. Importantly, they facilitate evidence use through a variety of different functions and activities. Some still focus on linear mechanisms such as the dissemination of evidence in accessible formats on their websites, whereas others actively build relationships and networks.

Another important difference between them is the type of evidence they focus on. There are agencies that carry out and disseminate research syntheses to support the use of research by practitioners and policy makers. These include the long established “What Works” centres, such as the English EPPI-Centre and the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), and some more recent agencies such as the Knowledge Centre for Education, established by the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research in 2013. These organisations usually reflect on the robustness of evidence, sometimes establish evidence standards (e.g., EEF), and usually have a strong focus on research that study the effectiveness of various interventions. Conducting secondary research, in particular systematic reviews and meta-analyses, is one of their core activities, but some also conduct primary research.

There are also many brokerage agencies that focus on system-level, large scale educational data, and provide statistical services and access to data. For example, Statistics Finland produces statistics for the entire education system from pre-primary to adult education. Some brokerage organisations produce regular reports on the state of education. These usually consist of the analysis of national and international student assessments and teacher surveys (e.g., PISA, TALIS), as well as administrative datasets. Considering data as the primary source of evidence-informed decision making is not unique to certain formal brokerage agencies. Many of the analytical units within ministries also interpret evidence in this sense, rather than as education research more broadly.

Overall, the landscape of organisational actors is highly diverse in the field of research mobilisation. To understand how these organisations facilitate research use in policy, we will now explore some of the mechanisms.

The second question of this paper asks how education systems facilitate the use of research in policy. This section discusses the presence of various mechanisms in OECD systems according to the Best and Holmes (2010) models introduced above. It then gives further information on certain aspects of all three approaches: research dissemination, capacity building, and monitoring and evaluation.

Mechanisms that facilitate research mobilisation can be characterised in various ways. They vary according to the different levels at which they act: individual, organisational and system (Nutley, Walter, & Davies, 2009). Knowledge mobilisation activities can also be classified based on the three conceptual approaches described by Best and Holmes (2010): linear, relational and systems. The framework used in this study (Table I) builds on Humphries and colleagues’ (2014) typology of factors developed in relation to the healthcare sector, which represents the variety of levels in the research production and use system, and incorporates linear, relational and systems approaches. This typology has been adapted and enriched with the work of other authors to ensure applicability in the education sector (see Table II and Table III).In the survey, respondents were asked to indicate which mechanisms exist in their system (from a list of 10). Further details were asked for a number of these mechanisms if the respondent indicated their presence. Given that the study explores mechanisms of the education system, the items were not referring to any specific individuals or organisations but were formulated in generic terms referring to the system.

Overall, education systems reported an average of 4.7 mechanisms that facilitate research use in policy with a strong dispersion across systems (Table IV). Some systems reported all or most of these mechanisms in place (e.g., Türkiye, the Netherlands, Finland and Sweden), while others only declared one or two mechanisms (e.g., the Swiss cantons of Uri and Nidwalden, the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic). Spain reported four mechanisms: systematically identifying research gaps, disseminating research findings in user-friendly formats, programmes encouraging interactions and providing targeted funding for research (Table VI).

None of the mechanisms are omnipresent in education systems (Figure IV). Over two thirds of systems (70%) provide targeted funding for research on specific topics, which is the most common mechanism. We must note that the classification of this mechanism as a systems approach is debatable. Targeted funding can be seen as a systemic incentive for linking research production and use through encouraging the production of research that is based on policy (or practice) needs. However, it can also be interpreted as a linear view in which research is produced and made available for users. In reality, funding incorporates a large number of actors (e.g., private, public, national, international funders) and factors (e.g., criteria and timeframes for funding) that influence research production and mobilisation. Unfolding this mechanism – or rather, multiple and complex mechanisms – is an endeavour worthy of a separate discussion and further attention from the research community.

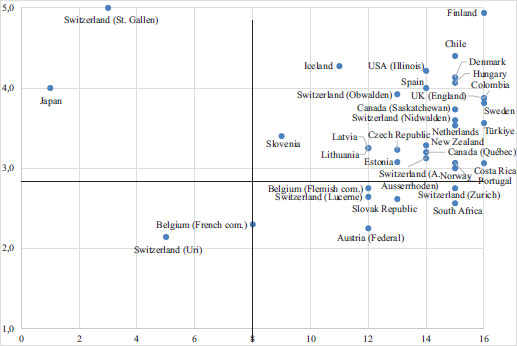

FIGURE IV. Mechanisms used to facilitate research use in policy by type

Note: Data refers to percentage of systems reporting the existence of a given mechanism, by type. N=37.

Source: OECD Strengthening the Impact of Education Research policy survey data.

Clearly, linear and relational mechanisms dominate the landscape of research mobilisation in policy making. If the provision of targeted funding is considered as a linear approach, then this is overwhelmingly true. Interestingly, more systems reported commissioning research based on needs than systematically identifying research needs. This suggests that commissioning research is based on ad-hoc needs at least in some systems. Nevertheless, approximately half of respondent systems identify research needs and research gaps systematically, although only 38% do both.

Disseminating research findings through user-friendly tools is the most traditional way of research mobilisation. Yet over 40% of systems do not have this basic linear approach. Those who do, reported a range of platforms and formats through which research findings are disseminated (Figure V). The most common ones are short fact sheets and infographics, executive summaries, policy briefs and reports of systematic reviews.

FIGURE V. Prevalence of different formats in which research is disseminated to policy

Note: Size reflects the relative proportion of the number of systems that reported using the given format. N=22 (systems that reported having any kind of dissemination format).

Source: OECD Strengthening the Impact of Education Research policy survey data.

In terms of relational mechanisms, two thirds of systems have projects or programmes that encourage interactions among actors, while about half of them reported mechanisms which systematically build policy makers’ capacity to use research. Capacity building includes both formal learning opportunities such as the provision of training and workshops, continuing specialist support and secondment programmes in research organisations, and informal ones, such as sharing good practices and offering resources (Figure VI). Informal mechanisms are more common.

FIGURE VI. Formal and informal learning opportunities that build policy makers’ capacity to use research

Note: Percentage of systems reporting that the given mechanisms exist in their systems from among those that reported the presence of capacity building mechanisms. N=18.

Source: OECD Strengthening the Impact of Education Research policy survey data.

Systems approaches are clearly the weak link in research mobilisation for policy. One single country (Türkiye) reported having all four mechanisms classified as systems approach. Only one in four education systems reported having legislation, laws or guidelines promoting the use of research, while one out of five systems have a system-wide strategy for facilitating research use in policy. With respect to the latter, interview data revealed that some countries that have an education research strategy, which is primarily focused on research production, did not report this as a research use strategy. For example, Norway’s research strategy – not reported for this survey question – includes elements with respect to knowledge mobilisation even though production is a key focus. Systems that have a system-wide strategy reported a significantly greater number of mechanisms on average than those without (7.6 versus 3.8), which may indicate the effectiveness of such strategies in some respect. Similarly to system-wide strategies, very few systems (22%) reported regularly monitoring or evaluating the impact of educational research across the system. Systems that monitor impact tend to do this in multiple ways, with Switzerland (St. Gallen) and Türkiye using all four forms of monitoring listed in the survey:

System-wide strategies to facilitate research use and monitoring the impact of research should ideally be connected. Yet only two countries, Finland and Türkiye, reported having both these mechanisms.

The third question of this paper asks about the barriers education systems are facing in facilitate the use of research in policy. This section presents the relative importance of various barriers in OECD systems and briefly discusses the relationship between mechanisms and barriers along the Best and Holmes (2010) framework.

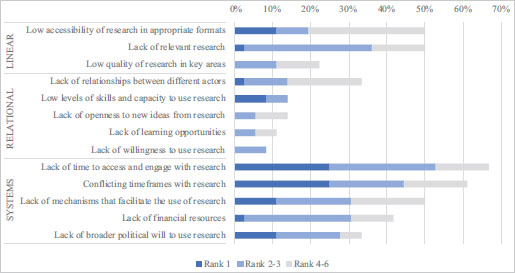

Respondents were also asked about what they perceive to be the main barriers to improving research use and rank three to six out of a dozen suggested options in order of importance (Figure VII). While systems factors are most commonly mentioned as barriers, an important proportion of education systems still face major barriers with respect to the availability, accessibility and quality of education research (i.e., linear factors). Lack of time to engage with research and the conflicting timeframes of research and policy making are the top barriers. The former may indicate a lack of appropriate incentives for policy makers.

Figure VII. Barriers to increasing and improving the use of education research in policy

Note: Data shows the percentage of systems ranking the given barrier, by type and rank range. N=37.

Source: OECD Strengthening the Impact of Education Research policy survey data.

Reported mechanisms and barriers are only partially consistent. Systems mechanisms exist in few education systems, and such barriers were correspondingly highly reported. However, many systems that reported having various linear mechanisms, still reported linear factors – notably, the accessibility of research in appropriate format – as an important barrier. Similarly, while most countries have projects encouraging interactions among actors, still about one third of these countries reported the absence of relationships between actors. This suggests that such projects do not yet fully fulfil their mission. Perhaps the most remarkable gap is that some countries reporting the lack of mechanisms facilitating the use of research as a major barrier also reported a higher number of mechanisms on average. This could imply that systems consider existing mechanisms to be insufficient in facilitating research use.

Overall, data suggests that while countries do report a number of ways in which they facilitate research use, these mechanisms do not ensure the systematic use of evidence in policy making. In the next section, we discuss some initial explanations of this problem.

The findings from the survey beg for examining the effectiveness of mechanisms that education systems have in place to facilitate research use in policy. While this study did not directly investigate effectiveness, knowledge mobilisation literature helps gauge at least some elements.

Modern conceptualisations of knowledge mobilisation recognise that the evidence production and use system is complex (Maxwell, Sharples, & Coldwell, 2022). Complex systems cannot be driven solely by linear mechanisms that assume that making research accessible will imply its use. Establishing relationships between actors has been proven to be fundamental to strengthen engagement with research and facilitate the production of relevant research (Langer, Tripney, & Gough, 2016). The findings presented above demonstrate that there are a large number of actors that play a role in producing and mobilising research evidence. While most systems today invest in fostering interactions between actors, this may not be enough. We have seen that even in systems where various programmes and projects facilitate interactions, missing relationships still hinder research use. This points to the importance of a systems perspective: some relationships may need to be created more strategically through mapping the actors and finding the “structural holes” (Burt, 1992).

In addition, research has shown that the impact of certain mechanisms on research use is stronger in combination with others (Langer, Tripney, & Gough, 2016). For example, building relationships between actors will only foster evidence use if the actors have the right competences to understand and engage with research, as well as to understand and appreciate other types of knowledge. Yet, systems tend not to complement relationship building with capacity-building activities and learning opportunities.

Ensuring a systematic use of research at the level of the entire system requires strategies that drive the dynamics of the whole system (Best & Holmes, 2010). What mechanisms are effective in facilitating the dynamics of the evidence ecosystem remains largely uncharted territory in the literature. In recent studies, strategic leadership, mechanisms that reward research impact and engagement, and creating infrastructure and positions in organisations specifically to foster research use have been emphasised (Oliver et al., 2022). A mapping of over 500 brokerage initiatives in a variety of sectors has shown that such mechanisms are rare (Oliver et al., 2022). The OECD survey confirmed this finding for education.

System-wide coordination, that ensures the connection between interventions and aligns action to a system’s context – including its actors and resources – and goals, is necessary for effectively governing complex education systems (OECD, 2016). While countries do report various initiatives to facilitate research use, system-wide strategies to coordinate these only exist in a handful of countries. The lack of coordination between initiatives can prevent them from fulfilling their potential impact and can be a barrier to using evidence in policy systematically. In addition, monitoring and evaluating the impact of the various initiatives, and providing appropriate incentive structures for all actors, including but not limited to funding, are also drivers of the entire evidence ecosystem. Yet, such systems approaches are still largely missing. For example, the dominant performance indicator for university-based researchers in most countries is publishing in academic journals, a format which clearly impedes their engagement with policy makers and other actors.

As shown in the embedded model of approaches to knowledge mobilisation, systems approaches will not be possible without relational and linear components. But some education systems still lack the basic foundations for research use: high-quality, relevant and accessible research itself. Mechanisms that would help ensure these foundations, such as identifying actors’ needs, fostering research production aligned to these needs and disseminating research findings are also not yet omnipresent.

In sum, while this data cannot tell us much about the effectiveness of each of the mechanisms, the overall picture of actors, mechanisms and barriers clearly indicates that in many systems the current set of mechanisms is not sufficient to achieve a systematic use of evidence in policy. What seems to be missing is an acknowledgement of the complexity of evidence systems and an appropriate system-level coordination of this.

This paper set out to investigate how education systems facilitate the use of research in policy making, who the actors are in this landscape and what barriers still exist to using evidence systematically and well. The OECD survey data has demonstrated that the landscape of actors and mechanisms is highly diverse across systems. While many systems have various mechanisms and a large number of actors that facilitate research use in policy, they also face important barriers. Overall, it seems that conceptual development in the field – an evolution from linear to systems approaches – has not yet fully translated into action. Just like the entire education system, the evidence system is also complex and requires governance approaches that consider this complexity. Countries first need to have a good understanding of existing actors, their functions and relationships, as well as the existing mechanisms of and barriers to research mobilisation. A systems approach could then involve creating a system- wide strategy that is adapted to the context and state of the art, establishing systemic incentives and ensuring strategic leadership.

While findings presented here point to some current challenges and initial paths to address these, the study also has a number of limitations. First, it reflects the perceptions of only one set of actors, that of policy makers, which may be a biased and narrow view of the evidence system. In the future it will be important to collect data from other actors, such as intermediary organisations and practitioners. Second, some quantitative information needs to be complemented by more qualitative data. For example, some countries reported to have system-wide strategies to facilitate research use. Exploring the content and implementation of such strategies would provide valuable information on governing knowledge mobilisation. Third, the study did not allow for gauging the relationships between the various dimensions, notably between actors and mechanisms. There remains a research gap with regard to how different organisations actually perform their research mobilisation functions and how they engage with or are affected by other mechanisms that exist in the system. Fourth, understanding how the evidence system can be improved requires understanding the impact of existing mechanisms, which this data could not map. The evaluation of intermediary efforts is a missing piece in general, and thus literature on their impact is scarce.

To address these limitations, future efforts should be aiming to map the functioning of intermediary actors, collect information directly from these actors to explore their activities, relationships and the challenges they are facing. Although assessing the impact of such initiatives is highly complex, the field should be moving towards understanding their effectiveness. The OECD Strengthening the Impact of Education Research project is therefore currently developing a new round of data collection from intermediary actors.

The diverse nature of evidence systems, both in terms of actors and mechanisms, suggests that a simple and unified approach to strengthening research engagement may not exist. However, this diversity also indicates that there is the potential for a large amount of knowledge exchange and shared learning between the different models. There is currently a strong momentum to increase and improve research use in education policy and practice. This special edition is an example of that, but we could also name recent manifestos [e.g., (Coe & Kime, 2019; Bofill Foundation, 2021)], investments both by NGOs and governments, and the strong interest from countries in international efforts such as that of the OECD. We must seize this momentum by bringing together the academic, policy and practice communities, as well as the various intermediary actors to collectively reflect on what works in “what works” and bring about the change needed for a more systematic and high- quality evidence use.

Best, A., & Holmes, B. (2010). Systems thinking, knowledge and action: Towards better models and methods. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 6(2), 145–159. doi:10.1332/174426410X502284

Boaz, A., & Nutley, S. (2019). Using evidence. In A. Boaz, H. Davies, A. Fraser, & S. Nutley (Eds.), What Works Now? Evidence-Informed Policy and Practice (pp. 251–277). Bristol: Policy Press.

Boaz, A., Oliver, K., & Hopkins, A. (2022). Linking research, policy and practice: Learning from other sectors. In Who Cares about Using Education Research in Policy and Practice?: Strengthening Research Engagement. OECD Publishing, Paris. doi:10.1787/70c657bc-en

Bofill Foundation. (2021). Apostem per la recerca per millorar l’educació del país. Retrieved from https://recercaperleducacio.cat/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/MANIFEST_020721_Apostem-per-la-recerca-per-millorar-leducacio%CC%81.pdf

Burns, T., Köster, F., & Fuster, M. (2016). Education Governance in Action: Lessons from Case Studies. In Educational Research and Innovation. OECD Publishing, Paris. Doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264262829-en

Burt, R. (1992). Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. MA: Harvard Press, Boston.

Campbell, C., Pollock, K., Briscoe, P., Carr-Harris, S., & Tuters, S. (2017). Developing a knowledge network for applied education research to mobilise evidence in and for educational practice. Educational Research, 59(2), 209–227. Doi: 10.1080/00131881.2017.1310364

Coe, R., & Kime, S. (2019). A (new) manifesto for evidence-based education: twenty years on. Sunderland, United Kingdom: Evidence Based Education. Retrieved from https://evidencebased.education/new-manifesto-evidence-based-education/

Cooper, A. (2014). Knowledge mobilisation in education across Canada: A cross-case analysis of 44 research brokering organisations. Evidence and Policy, 10(1). Doi: 10.1332/174426413X662806

Gough, D., Maidment, C., & Sharples, J. (2018). UK What Works Centres: Aims, Methods and Contexts. EPPI-Centre, Institute of Education, University College London. Retrieved from https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Portals/0/PDF%20reviews%20and%20summaries/UK%20what%20works%20centres%20study%20final%20report%20july%202018.pdf?ver=2018-07-03-155057-243.

Gough, D., Tripney, J., Kenny, C., & Buk-Berge, E. (2011). Evidence informed policymaking in education in Europe. In EIPEE Final Project Report Summary.

Humphries, S., Stafinski, T., Mumtaz, Z., & Menon, D. (2014). Barriers and facilitators to evidence-use in program management: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1). Doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-171

Langer, L., Tripney, J., & Gough, D. (2016). The Science of Using Science Researching the Use of Research Evidence in Decision-Making. EPPI-Centre, Institute of Education, University College London.

Levin, B. (2008). Thinking about knowledge mobilization. Paper presented at a symposium sponsored by the Canadian Council on Learning and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.oise.utoronto.ca/rspe/UserFiles/File/KM%20paper%20May%20Symposium%20FINAL.pdf

Levin, B. (2013). To know is not enough: Research knowledge and its use. Review of Education, 1(1), 2–31. Doi: 10.1002/rev3.3001

Maxwell, B., Sharples, J., & Coldwell, M. (2022). Developing a systems-based approach to research use in education. Review of Education, 10(3). Doi: 10.1002/rev3.3368

Nutley, S., Powell, A., & Davies, H. (2013). What counts as good evidence? Provocation paper for the Alliance for Useful Evidence. Alliance for Useful Evidence, University of St Andrews. Retrieved 10 18, 2019, from www.alliance4usefulevidence.org

Nutley, S., Walter, I., & Davies, H. (2009). Promoting evidence-based practice: Models and mechanisms from cross-sector review. Research on Social Work Practice, 19(5), 552–559. doi:10.1177/1049731509335496

OECD. (2000). Knowledge Management in the Learning Society. OECD Publishing, Paris. Doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264181045-en

OECD. (2003). New Challenges for Educational Research. In Knowledge Management. OECD Publishing, Paris. Doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264100312-en

OECD. (2007). Evidence in Education: Linking Research and Policy. OECD Publishing, Paris. Doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264033672-en

OECD. (2016). Governing Education in a Complex World. In T. Burns, & F. Köster (Eds.), Educational Research and Innovation. OECD Publishing, Paris. Doi: 10.1787/9789264255364-en

OECD (2019). Research and Development Statistics: Gross domestic expenditure on R-D by sector of performance and socio-economic objective (Edition 2018), OECD Science, Technology and R&D Statistics (database).

OECD. (2022). Who Cares about Using Education Research in Policy and Practice?: Strengthening Research Engagement. In Educational Research and Innovation. OECD Publishing, Paris. Doi: 10.1787/d7ff793d-en

Oliver, K., Hopkins, A., Boaz, A., Guillot-Wright, S., & Cairney, P. (2022). What works to promote research-policy engagement? Evidence & Policy, 1–23. Doi: 10.1332/174426421x16420918447616

Powell, A., Davies, H., & Nutley, S. (2017). Facing the challenges of research-informed knowledge mobilization: ‘Practising what we preach’? Public Administration, 96(1), 36–52. Doi: 10.1111/padm.12365

Rickinson, M., Walsh, L., Cirkony, C., Salisbury, M., & Gleeson, J. (2020). Quality Use of Research Evidence Framework. Monash University, Melbourne Retrieved from https://www.monash.edu/education/research/projects/qproject/publications/quality-use-of-research-evidence-framework-qure-report

Van De Ven, A., & Johnson, P. (2006). Knowledge for theory and practice. The Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 802–821. Retrieved 12 09, 2019, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/20159252.pdf

Contact address: José Manuel Torres, 2 Rue André Pascal, 75016, Paris, France. email jose.torres@oecd.org

TABLE I. Number of systems reporting organisations to be active in facilitating the use of education research and in research production

|

Universities/ Faculties of Education |

Ministry of Education |

Teacher education institutions |

Other public research organisations |

Academic or research networks |

Government funding agencies |

University - School networks |

PD providers for teachers |

Other professional groups |

Policy networks |

Education consulting firms |

Teacher unions |

Brokerage agencies |

Think tanks |

Media |

School networks |

Businesses |

Facilitating research use in POLICY |

32 |

32 |

17 |

20 |

21 |

18 |

17 |

12 |

14 |

11 |

13 |

13 |

8 |

10 |

11 |

|

6 |

Facilitating research use in PRACTICE |

24 |

21 |

21 |

17 |

13 |

16 |

14 |

19 |

13 |

10 |

9 |

12 |

10 |

4 |

2 |

12 |

7 |

Producing education RESEARCH |

30 |

26 |

22 |

20 |

22 |

21 |

14 |

13 |

5 |

10 |

8 |

4 |

9 |

6 |

6 |

7 |

4 |

Note: 1. Data was collected at national and sub-national levels. 2. School networks did not feature as an option when ministries were asked about facilitating research use in policy. This was building on the assumption that school networks are not focused on increasing the use of research in policy. 3. “PD providers ” refers to professional development providers. 4. In some countries, Teacher education institutions and Faculties of Education may overlap, which implies limitation to the correct interpretation of data.

Source: OECD Strengthening the Impact of Education Research policy survey data.

TABLE II. Typology of factors influencing research use

Type |

Definition |

Information |

Existence and quality of relevant research evidence, its availability, accessibility and format; and its channels of circulation and dissemination. |

Interaction |

Contact, collaboration and flow of information between researchers, practitioners and policy makers through formal or informal relationships; the characteristics of these relationships, such as trust and mutual respect. |

Individual characteristics |

Researchers' understanding of the policy and practice processes and context; Practitioners’ and policy makers' skills and capacity to use research; related learning opportunities in formal and informal education and training. Similar characteristics of other actors influencing the use of research evidence. |

Structure and organisation |

System and organisational support for the production and use of research, manifested in formal structures (e.g., provision of time, funding, learning opportunities, formal training) and/or processes (e.g., presence of guidelines and financial incentives). |

Culture |

Researchers’, practitioners’ and policy makers' priorities and their alignment; Actors’ attitudes towards research and willingness to use it; System and organisational values, principles, beliefs, and valorisation of research production and use. |

Source: Adapted from Humphries, S. et al. (Humphries, Stafinski, Mumtaz, & Menon, 2014).

TABLE III. Factors influencing research use by type of approach in the OECD Strengthening the Impact of Education Research policy survey

Type of approach |

Barriers |

Mechanisms |

Linear |

|

|

Relationships |

|

|

Systems |

|

|

TABLE IV. Number of mechanisms facilitating research use

COUNTRY |

IN POLICY MAKING |

IN PRACTICE |

Türkiye |

10 |

10 |

Netherlands |

9 |

10 |

Finland |

9 |

10 |

Sweden |

9 |

9 |

Hungary |

8 |

7 |

Canada (Saskatchewan) |

7 |

8 |

Slovenia |

7 |

7 |

Belgium (Flemish community) |

7 |

5 |

Switzerland (St. Gallen) |

7 |

5 |

Norway |

7 |

5 |

Canada (Quebec) |

7 |

4 |

Switzerland (Appenzell A.) |

6 |

9 |

United Kingdom (England) |

5 |

8 |

Switzerland (Lucerne) |

5 |

7 |

Chile |

5 |

4 |

Latvia |

5 |

3 |

Belgium (French community) |

5 |

3 |

Spain |

4 |

6 |

Austria |

4 |

6 |

Estonia |

4 |

5 |

Iceland |

4 |

2 |

Switzerland (Obwalden) |

4 |

2 |

New Zealand |

3 |

7 |

Denmark |

3 |

5 |

Lithuania |

3 |

3 |

Colombia |

3 |

3 |

Japan |

3 |

2 |

South Africa |

3 |

2 |

Switzerland (Zurich) |

3 |

1 |

United States (Illinois) |

2 |

5 |

Costa Rica |

2 |

3 |

Portugal |

2 |

3 |

Switzerland (Uri) |

1 |

2 |

Switzerland (Nidwalden) |

1 |

2 |

Czech Republic |

1 |

1 |

Slovak Republic |

- |

1 |

Note: Maximum number is 10.

Source: OECD Strengthening the Impact of Education Research policy survey data.

TABLE V. Actors in research production and mobilisation in Spain

Universities/ Faculties of Education |

Other professional groups |

Ministry of Education |

Government funding agencies |

Other public research organisations |

Academic or research |

Policy networks |

Teacher unions |

School networks |

University - School networks |

Education consulting |

Think tanks |

Businesses |

Media |

Teacher education |

Brokerage agencies |

Pro. devt. providers for teachers |

Very active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

* |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Moderately active |

|

|

Active |

Very active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

|

|

Very active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Moderately active |

|

|

Note: * School networks did not feature as an option when ministries were asked about facilitating research use in policy. Spain did not report the presence of brokerage agencies and professional development providers.

Source: OECD Strengthening the Impact of Education Research policy survey data.

TABLE VI. Mechanisms and barriers reported by Spain

Mechanisms |

Barriers (in order of relevance) |

|

|

Source: OECD Strengthening the Impact of Education Research policy survey data.

_______________________________

1 The paper draws on analyses published in the volume “Who Cares About Using Education Research in Policy and Practice” (OECD, 2022), adding new data, analyses and insights to it.

2 https://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/education-research.htm

3 Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, South Africa.

4 OECD member countries: Austria, Belgium (Flemish and French Communities), Canada (Quebec, Saskatchewan), Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Hungary, Iceland, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland (Appenzell Ausserrhoden, Lucerne, Nidwalden, Obwalden, St. Gallen, Uri, Zurich), Türkiye, United Kingdom (England), United States (Illinois). Non-member countries: Russian Federation, South Africa.