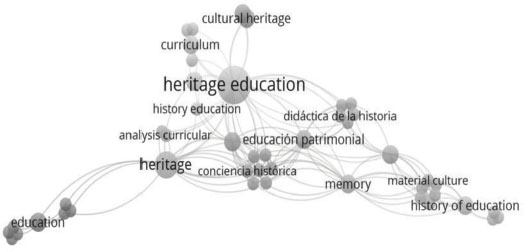

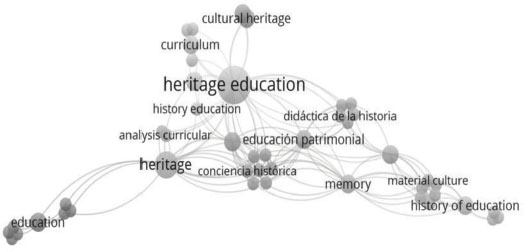

FIGURE I. Word co-occurrence networks on the Web of Sciences.

Source: VOSviewer

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2023-400-577

Inmaculada Sánchez-Macías

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8908-9333

Universidad de Valladolid

Alice Semedo

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8308-0971

Universidade do Porto

Guadalupe García-Córdova

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2753-1595

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

Abstract

Within the framework of research stays at the Centro de Investigação Transdisciplinar "Cultura, Espaço e Memória" (CITCEM, Oporto), an analysis of curricular regulations on heritage education in three countries: Portugal, Mexico and Spain was carried out, focusing on evidence of similarities and differences in the laws of the countries compared. The main objective is to discover what are the conceptualisations of each country on heritage education according to their educational regulations, what is understood by heritage, as well as to analyse which laws provide for the practice of this subject and what are the main differences between them. Comparisons are made with the official documents that govern the Education Systems and that prescribe the heritage education curriculum for Spanish Compulsory Secondary Education and its age counterparts (11 to 16 years old) in Portugal and Mexico. An exploratory sequential mixed method is used, with a first phase of bibliometric analysis using VOSwiever software, in which the categories of ethical analysis are extracted, and a second phase of content analysis of the laws themselves, based on a constructivist and post-constructivist worldview of reality. As a result, we found similarities, such as the approach to the concept of heritage, which is very close to that of culture and art used by the three countries in their education and some of the subjects that help to integrate heritage education, such as History, Language or Art; at the same time, there are numerous asymmetries or differences with regard to another series of subjects, differences in the courses in which they are dealt with, asymmetries that are related to the history of the countries and their regulatory changes over the years. There is a need for future discussion on a number of factors such as the role of teachers, their initial training, teaching practice, the students of the new century and the architects of the laws.

Keywords: Comparative Education; Curriculum; High Schools; Heritage Education; Educational Law.

Resumen

En el marco de estancias de investigación, se realizó un trabajo de análisis de normativa curricular sobre educación patrimonial en tres países: Portugal, México y España, enfocándose en evidencias de similitudes y diferencias en las leyes de los países comparados. El objetivo principal es descubrir cuáles son las conceptualizaciones de cada país sobre la educación patrimonial según sus normativas educaticas, qué se entiende por patrimonio, además de analizar qué leyes disponen la práctica de esta disciplina y cómo son las diferencias principales entre ellas. Las comparaciones se realizan con los documentos oficiales que rigen los Sistemas Educativos y que prescriben el currículo de educación patrimonial de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria española y sus homólogos en edad (11 a los 16 años) en Portugal y México. Se utiliza un método mixto secuencial exploratorio, con una primera fase de análisis bibliométrico a través del software VOSwiever, en el que se extraen las categorías de análisis étic y una segunda fase de análisis de contenido de las propias leyes, basado en una cosmovisión constructivista y postconstructivista de la realidad. Como resultados encontramos semejanzas, como, la aproximación al concepto de patrimonio muy cercano al de la cultura y arte que los tres países utilizan en su educación y algunas de las asignaturas que ayudan a transversalizar la educación patrimonial, como la Historia, la Lengua o el Arte; a su vez, numerosas asimetrías o diferencias en cuanto a otra serie de asignaturas, diferencias en los cursos en los que se tratan, asimetrías que tienen que ver con el transcurrir de la historia de los países y sus cambios normativos a lo largo de los años. Es necesario discutir en un futuro sobre varios factores como el rol del profesorado, su formación inicial, la práctica docente, el alumnado del nuevo siglo y los diseñadores de las leyes.

Palabras clave: educación comparada; currículo; educación secundaria; educación patrimonial; ley educativa.

Research into comparative education starts with the pioneer Jullien (1817) who sought to deduce true principles and established pathways for education to become an almost exact science (Fraser 1964, p. 20). Some authors, such as Adamson et al. (2017), also argue that Jullien is based on a positivist epistemology, similar in nature to many recent international studies, but his positioning was more holistic than some of the most influential worldwide, including PISA studies ( OECD 2013, 2016). Sobe (2018) reminds us that the comparison between countries is a crossroads between points of view, perspectives, reference frameworks, readings, which puts the notion of “relationality” at the centre (p.335). Moreover, from the socio-historical perspective of comparative education, all production of knowledge is seen as the reflection of a discursive community that imposes “legitimate knowledge and ways of thinking about education” (Novoa, 2005, p.2 4). This means that comparing educational policies requires variables articulated with a series of cultural, ideological and axiological relationships (not always quantifiable) that shape social processes. Carrying out a comparative analysis is not necessarily making a standardized and homogenized comparison of educational systems, characteristic of the institutional isomorphism typical of the 19th and 20th centuries, both of the masses and the elites (Meyer and Ramírez, 2002).

The study presented herein was carried out jointly in an exchange between research groups from the University of Porto (Portugal), the National Autonomous University (Mexico) and the University of Valladolid (Spain), presenting the problem of the concept of heritage in the educational regulations of the three countries, whether it coincides in its axioms; or what importance is being given to heritage education as a transversal subject in the curricula, or if the hidden curriculum includes different conceptualizations in the chosen countries. To this end, the general objective of the study is to develop comparative knowledge among educational regulations and, specifically, the current laws of Portugal, Mexico and Spain on heritage education, focusing specifically on the stages of secondary education (Spain), basic and secondary education (Portugal) and primary, secondary, preparatory, colégios and secondary schools (Mexico), that is, education in the three countries from 11 to 16 years old.

The exchange among researchers from the three countries allows us to conceptualize and theorize heritage education and thus have an impact on public policies, especially on national curriculum policies.

Moving from the analysis of educational systems to schools, from educational structures to social agents, from the level of ideas to discourse, from the facts to the political dimension (Nóvoa, 1998), helps us to identify new problems, to apply new forms of analysis and approaches to then produce new meanings for the teaching-learning processes (Ferreira, 2009, Madeira, 2009, Schriewer, 2009), in brief, to optimize pedagogical practices.

When designing education plans for students between 11 and 16 years old, it is necessary for those who are in charge to specify in the documents the purposes, concepts and principles that will guide the way in which the proposed objectives will be achieved. Moreover, it must be taken into account that within the same country there is a great cultural plurality, depending on the established regions or areas, and these differences must be taken into account when creating and designing the curriculum. In addition, as specific objectives, we are interested in discovering and comparing whether heritage education, in each country’s curriculum, is transmitted with a focus on certain subjects or specific subjects or the use of new technologies and active pedagogical methodologies, which are very up-to-date, as well as researching whether the concept of heritage is built throughout the documents and with what model it is assimilated, and what is the contribution of each subject so that heritage education is determined as a transversal subject in these countries, with the prior assumption of the growth in a significant production of the subject at national and international level.

There are many definitions of curriculum in the academic literature, but we highlight the definition proposed by Sacristán (2000) as a very pertinent and up-to-date one:

A practice, an expression of the socializing and cultural function that a given institution has, which regroups around it a series of subsystems or diversified practices, among which the pedagogical practice developed in the school institutions that we usually call teaching (pp.15-16).

But these specific characteristics of each curriculum are also related to the access to knowledge, taking into account to whom it is proposed and the relevant objectives. However, a distinction must be made between this curriculum and what is traditionally defined as the process that is focused on establishing objectives and content for each educational stage (Pires, 2000). Relevant in the definition on which we base this document is the idea supported by the latest recommendations of the Council of Europe of a curriculum as something that is built before and during the teaching-learning process, which lasts a lifetime. As such, this is a process that is shaped by the people who make decisions about the curriculum, each with their own views and teaching experiences.

In Portugal, the curriculum follows the Basic Law of the Portuguese Education System (Law No. 46/1986, approved on 14 October 1986, and later amended in 1997, 2005 and 2009, 2018). The first two amendments dealt with issues related to access and funding of higher education (1997 and 2005), and the third one, in 2009, with the establishment of compulsory education for school age children and young people and also the establishment of universal pre- school education for children from 5 years of age. The programming follows the concept of Essential Learning, for all subjects and courses, and is developed in conjunction with professional associations. They are defined as the common set of acquired knowledge, identified as structured, indispensable, conceptually articulated, relevant and significant content of subject knowledge, as well as competences and attitudes to be mandatorily developed by all students in each subject area or subject, with reference, in general, to the education grade or training grade (Law No. 46/1986, Article 3. p.2). They implement ten learner profile competence areas (LPCA) into each of the essential learning (EL) outcomes.

They include permeability among Secondary Education courses (see Table I), with the possibility of subject permutation. The National Strategy for Citizenship Education was implemented. Under the European Union International Cooperation Programme (INCO, 2030), Information and Communication Technologies will be extended to all grades of the second and third cycles. The 2018-2019 academic year is the first year in which the new law will be implemented, so it will not be possible to study the results in depth until its full implementation.

TABLE I. Education systems in Portugal, Mexico and Spain.

|

Age |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

|

15 |

16 |

PORTUGAL |

Levels |

BASIC |

SECONDARY |

|||||

Cycles |

|

2nd |

3rd |

|

|

|||

Grades |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

||

Subject fields |

Humanities Scientific Technology Specialist Artistic Professional Internship |

|||||||

MEXICO |

Levels |

|

PRIMARY |

SECONDARY |

|

MIDDLE UPPER |

||

Cycles |

|

3rd |

NA |

|

NA |

|||

Grades |

|

6th |

1st 2nd 3rd |

|

4th/1st |

5th/2nd |

||

Subject fields |

Mathematics Experimental Sciences Social Sciences Humanities Communication |

|||||||

SPAIN |

Levels |

SECONDARY |

|

|||||

Cycles |

|

1st |

2nd |

|

|

|||

Grades |

|

1st 2nd |

3rd 4th |

|

|

|||

Subject fields |

Biology and Geology. Physical Education. Plastic, Visual and Audiovisual Education. Physics and Chemistry. Geography and History. Spanish Language and Literature and, if any, Co-official Language and Literature. Foreign language Mathematics. Music. Technology and Digitalization |

|||||||

Source: Compiled by author

For its part, Mexico bases the national education system according to the General Law of Education, based on the New Education Model (2017), which divides it as follows: A) Compulsory basic education pre-school (5 years), primary (6-11 years) and secondary (12-14 years) (see Table II). This is the same reformulated regulation (2019) for the 32 states of the Republic and is public. B) upper secondary education, which includes baccalaureate, vocational technical baccalaureate and equivalent levels, and vocational education. This 2019 standard will promote the comprehensive development of learners, their knowledge, skills, abilities, attitudes and professional competences, through meaningful learning in subject areas of natural and experimental sciences, social sciences and humanities; as well as in transversal areas of knowledge integrated by mathematical thinking, history, communication, culture, arts, physical education, and digital learning. In its article 6, it proposes that all people living in the country must attend pre- school, primary, secondary and upper secondary education, that is, education is compulsory up to the age of 18.

TABLE II. Ethical categories proposed for content analysis.

CATEGORIES |

WORDS AND WORD FAMILIES |

patrim* |

Patrimonio/s, patrimonial/es, patrimonialización… |

art* |

Arte/s, artístico/s, artista/s… |

muse* |

Museo/s, museístico/s, museográfico/s… |

memo* |

Memoria, memorial… |

cult* |

Cultura/s, cultural/es, multicultural/es, transcultural/es, intercultural/es… |

ident* |

Identidad, identitario… |

monument* |

Monumento/s, monumental, monumentalista… |

ciudad* |

Ciudad, ciudadanía, ciudadano/a… |

arqueol* |

Arqueología, arqueológico/a… |

vincul* |

Vínculo, vinculativo… |

perten* |

Pertenencia, pertenece… |

famili* |

Familia, familiar… |

herencia* |

Herencia, hereditario/a… |

Source: Compiled by author

The services that make up secondary education in Mexico are: a) Secondary, including general, technical, community or regional modalities authorized by the Ministry; b) Secondary for workers; and c) Telesecondary.

In the case of Spain, with the LOMCE (2013), in compulsory secondary education (see Table III), the number of competences decreased from eight to seven. They are no longer called basic competences, just competences or key competences. There are two types: two basic (linguistic and mathematical, science and technology) and five transversal (digital, learning to learn, social and civic, initiative and entrepreneurship, and cultural awareness and expression).

TABLE III. Study categories count

|

PORTUGAL |

MEXICO |

SPAIN |

patrimo* |

33 |

39 |

22 |

art* |

143 |

314 |

63 |

muse* |

2 |

33 |

2 |

memo* |

3 |

4 |

2 |

cult* |

175 |

448 |

236 |

ident* |

22 |

82 |

42 |

monument* |

4 |

9 |

8 |

ciudad* |

85 |

107 |

56 |

arqueol* |

1 |

6 |

10 |

vincul* |

0 |

4 |

9 |

perten* |

12 |

0 |

8 |

famili* |

2 |

17 |

53 |

herencia* |

4 |

0 |

11 |

TOTAL |

486 |

1063 |

438 |

Source: Prepared by author

Learning patterns are the new element included by LOMCE in the curriculum elements. They are defined as the specificities of the assessment criteria, which allow specifying the objectives that students must achieve at the end of each stage (what they must know and know how to do at the end of each year in each subject). The three types of topics mentioned above appear (core, specific and standalone free configuration). In the ESO (Compulsory Secondary Education) stage, at the end of the fourth grade, students are assessed by means of external tests designed by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports; passing these tests is essential to qualify for the Baccalaureate. In the fourth grade of ESO, students will have two options, they may choose between: the path that leads to the Baccalaureate (known as the Academic Studies Option for introduction to the Baccalaureate) or the path that leads to Intermediate Vocational Training (Applied Studies Option for introduction to Vocational Training).

Currently, the LOMLOE, Organic Law 3/2020, of 29 December, which amends Organic Law 2/2006, of 3 May, on Education, was approved by the current government and it is important to understand that it is organized around three key objectives: to update the LOE, to eliminate the most dysfunctional aspects of the LOMCE, and to guide the education system towards student success. In 2018, the Recommendation of 22 May 2018 of the Council of the European Union on key competences for lifelong learning was made, which not only revises the list of key competences, but also establishes that Member States should “incorporate the ambitions of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (…) in education, training and learning”, included in the 2030 Agenda. The amendments included in this law are multiple: the definition of childhood education as an educational stage with its own identity is recovered and its objectives are redefined (article 12.1 and article 17), the primary education cycles are recovered (article 18), an explicit reference to the contributions of non-formal education within the lifelong learning framework and its connection with formal education for the development and acquisition of competences is incorporated (article 5), plans are added to promote reading, literacy in multiple ways proposed by UNESCO (Article 19. 3), promoting the use of ICT, digitalization, virtual environments, foreign languages and research and innovation (art. 55.3), promoting the development of significant and relevant projects through inductive methodologies (articles 19.4, 24.3 and 26.2), ensuring the inclusion with personal and economic resources (articles 81, 87. 1 and 88), subjects are integrated to ensure learning for all students with specific needs (art. 22.5), promotion of an educational approach to avoid failure and absenteeism (articles 20 and 28), and education in environmental sustainability and social cooperation (art. 110.3), among others.

To better understand the curricular proposals, we propose Table I, which specifies the differences and similarities in the ages considered, in terms of training levels, cycles, number of years and subject fields:

The study focuses precisely on these educational stages in order to address - and, when appropriate, confront the concept of heritage from which we start, since these are stages in which the concept of identity is fully developed. Heritage education, understood as a transversal subject in the curriculum, takes into account several satellite concepts that help to understand it: identity, citizenship, new technologies, innovative methodologies, and globalization.

With regard to the concept of identity, Tajfel (1978) defines it as “the part of the individual's self-concept that derives from the knowledge of their belonging to a social group (or social groups) together with the emotional and evaluative meaning associated with that belonging” (p. 68). And, after Quiroga (1999), identity develops in three stages, an evolutionary change from the beginning of adolescence to the acquisition of this identity between the ages of 18 and 28.

It is in the secondary education stage that social identity, one of the concepts that are part of heritage, settles; and with regard to this identity and following a holistic approach to the concept, we are based on an interdisciplinary perspective between the natural and cultural aspects of heritage, with scientific-technological, historical-artistic and ethnological references, contextualized in a specific space-time and cultural environment, which give meaning and identify a given society (Cuenca and López-Cruz, 2014; Cuenca, Martín and Schugurensky, 2017).

The notion of heritage is important for the countries’ culture and development, contributing to the continuous reframing and revaluation of cultures and identities, being an important vehicle for the transmission of experiences, competences and knowledge between generations (UNESCO, 2003, Art. 2.1). Along this same line, Choay (2001) reminds us that heritage does not survive outside the memory and culture exercise of a given population, that is, heritage must be recognized by that social group, must have a place in the affective memory of that group, so that it does not run the risk of being forgotten and lost. And this idea is restated in Fontal (2013, p.65). In this paper, we attribute an integral view of heritage in education, developed through three models: the mediator, the symbolic and the connecting; it is a conception of heritage that enhances its human dimension so that both the material, immaterial and spiritual elements of the human condition are dealt with (Fontal, 2003, 2012; Fontal, Sánchez-Macías and Cepeda, 2018; Trabajo and López, 2019).

The Spanish National Plan for Education and Heritage (PNEyP, 2015) reminds us that heritage education is a subject designed to link heritage to its society, which is at the same time its generator, owner and depositary (PNEyP, 2015, p .22). Research in this field is crucial and is promoted by different institutions for the development of countries and societies that comprise them.

Heritage education also has repercussions in strengthening the concept of citizenship, with the right to memory, but also with the duty to contribute to keeping the country's valuable cultural heritage (Oriá, 2005), while understanding it as a construction with multiple contributions.

In this Secondary Education and Baccalaureate age group, the use of new technologies (ICT) is of the utmost importance, based on the wide acceptance they have in global and extracurricular life with great mobility in the physical space, of technology, in a conceptual space from a personal interest that evolves, in the social space, and finally, in learning dispersed in time (Ibáñez-Etxeberria, Asensio and Correa, 2012, p. 65). This ICT idea is confronted with the situationism of the projects inside the classroom, as pointed out in the Portuguese case, on the defence of collections and historical museums of natural or health sciences (Lourenço, 2009; Gomes, 2017), in which Mota-Almeida (2020) also includes certain requirements for the Portuguese teachers, extensive to Spain, with regard to the lack of training of specific personnel with specialization in heritage collections, or specific training for regular teachers or the creation of a reserve of hours to be dedicated specifically to this heritage. This draws us to the theoretical formulation of these requirements with a more generic scope proposed by Fontal (2003), which led to the regulation of methodologies in heritage education through multidisciplinary criteria.

Globalization can also arise from some definitions of globalization, the philosophical paradigm in which looking at the past can be questioned ontologically, which will problematize the importance of Heritage, History and Heritage Education. Heritage education must move from the current stage, which is used to complement the current curriculum, to the follow-up of the results of several studies (Fontal and Ibáñez-Etxeberria, 2017) that suggest that it should be included not only in the students’ learning experiences, but also in the national curriculum. This requirement is essential in the Spanish, Portuguese and Mexican contexts, demanding the removal of formal obstacles, both in more general laws and in curricular designs, as a central axis to support the pedagogical reform in individual projects spread throughout the territories of the three countries.

For this study, we designed a mixed sequential exploratory research method (Clark et al. 2008; Hanson et al. 2005; Creswell, 2014), in which quantitative (quan) data were extracted, documentary analysis (Gil Pascual, 2011) and qualitative (QUAL) data, supported by Grounded Theory (Flick, 2007), and integrated into the interpretation phase.

First, we carried out a co-occurrence analysis of bibliographic words from the three databases in which the main topic was Heritage Education and the secondary topics: Portugal, Mexico, Spain and Secondary, in the last five years, with VOSwiever software (Van Eck and Waltman, 2010). The co-occurrence analysis of words is included in the classification of relational and multidimensional indicators (Callon, Courtial & Penan, 1995; Leydesdorff & Welbers, 2011). This analysis is carried out when there are joint occurrences of two terms in a given text in order to identify the conceptual and thematic structure of a scientific domain. After selecting the words, co-occurrence networks or matrices are created and the similarity among them is measured (see Fig. I):

FIGURE I. Word co-occurrence networks on the Web of Sciences.

Source: VOSviewer

Based on this result, together with the proposals of four subject matter specialist judges, we used words and their respective families, which served as categories in our study, specified in Table II.

These ethical categories are analysed in a second qualitative phase, within each one of the documents analysed, which are our sample: Basic Law of the Portuguese Education System (Law No. 46/1986, approved on 14 October 1986, and later amended in 2018), General Law of Education (2017) of Mexico and the current law in Spain, LOMLOE, Organic Law 3/2020, of 29 December.

Initially, the ethical categories were developed (patrim*, art*, muse*, memo*, cult*, ident*) and later, after the judges' analysis, the emic categories were added (monumento*, cidade*, arqueol*, vincul *, perten*, famili*, herencia*), thus completing the group of study categories presented in Table II.

The results of the document analysis will be grouped into several points according to our research objectives:

Firstly, according to the count of word-categories searched in the regulation, it can be seen (see Table III) that the most frequent category is culto* and its word family, followed by arte* and the least frequent is vincul*, perten* or herencia*. This gives an idea of the meanings and concepts closer to heritage that are used in these documents, in which culture and art are the protagonists of this definition; however, the coded categories do not always coincide with the definitions we have of them, with other attributes characterizing them. In general, these words (culture and art) are classified in the curriculum as: culture and geography, cultures and societies, artistic manifestations, artistic and documentary heritage, natural, historical and linguistic heritage, historical-artistic heritage, archaeological heritage, musical heritage, folkloric heritage, indigenous heritage, popular culture, etc.

Secondly, in the three countries we can find explicit references to the values and attitudes of the concept of heritage about “knowing, valuing and respecting the basic aspects of one's own and other peoples’ culture and history, as well as artistic and cultural heritage” (LOMLOE, Chapter III, Art.23, p.57); in the Portuguese law, it is stated that it is necessary to “ensure a general education common to all Portuguese people that guarantees the discovery and development of their interests and abilities, reasoning ability, memory and critical thinking, creativity, moral sense and aesthetic sensitivity, promoting the individual achievement in harmony with the social solidarity values” (Decreto de Educación Básica, Objetivos, p. 7). In this sense, in Mexico, its law highlights: “knowledge of the arts, appreciation, preservation and respect for musical, cultural and artistic heritage, as well as the development of artistic creativity through technological and traditional processes” (LGE, Article 30. Conteúdos, 22). The third result found in the analysis is related to the subjects that take into account the heritage defined through the chosen analysis categories (see Table IV):

TABLE IV. List of subjects that include heritage in their competences.

PORTUGAL |

|

2nd CYCLE |

History and Geography of Portugal 5th and 6th grade |

Natural Sciences 5th and 6th grade |

|

Technological Education 2nd cycle |

|

Visual Education 2nd cycle |

|

Portuguese 5th and 6th grade |

|

3rd CYCLE |

History 7th, 8th and 9th grade |

Geography 7th, 8th, 9th grade |

|

Visual Education 3rd cycle |

|

Natural Sciences 7th, 8th, 9th grade |

|

Portuguese 7th, 8th, 9th grade |

|

SECONDARY - 10th grade |

Biology and Geology 10th grade |

Geography A 10th grade |

|

History A 10th grade |

|

History B 10th grade |

|

History of Culture and Arts 10th grade |

|

Portuguese 10th grade |

|

Basic and Secondary Education |

Citizenship and Development |

MEXICO |

|

6thPRIMARY |

Arts |

1st-3rd SECONDARY |

Civics and Ethics |

Mother Tongue/Spanish |

|

Mother/Indigenous Tongue |

|

History |

|

Geography |

|

ESCUELA NACIONAL PREPARATORIA |

Spanish Language |

Universal History |

|

Aesthetic and Artistic Education IV |

|

History of Mexico |

|

Aesthetic and Artistic Education V |

|

World Literature |

|

Geography |

|

COLEGIO D CC Y HUMANIDD |

Modern and Contemporary Universal History I and II |

CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS CIENTÍFICOS Y TECNOLÓGICOS |

History of Mexico I and II |

Modern and Contemporary Universal History II |

|

Modern and Contemporary Universal History I |

|

Philosophy I |

|

Philosophy II |

|

Colegio Nacional de Educación Profesional Técnica (HOSPITALIDAD TURISTICA) |

Citizen Development |

Colegio de Bachilleres |

Social Sciences |

Introduction to Philosophy |

|

Art Appreciation |

|

Ethics |

|

SPAIN |

|

1st SECONDARY |

Biology and Geology |

Geography and History |

|

Castilian Language and Literature |

|

Mathematics |

|

First Foreign Language: ……………….. |

|

Physical Education |

|

Ethical Values or Religion |

|

Plastic, Visual and Audiovisual Education |

|

Technology |

|

2nd SECONDARY |

Biology and Geology |

Geography and History |

|

Castilian Language and Literature |

|

Mathematics |

|

First Foreign Language |

|

Physical Education |

|

Ethical Values or Religion |

|

Music |

|

Classical Culture |

|

3rd SECONDARY |

Biology and Geology |

Physics and Chemistry |

|

Geography and History |

|

Castilian Language and Literature |

|

Maths AC or AP |

|

First Foreign Language |

|

Physical Education |

|

Ethical Values or Religion |

|

Latin |

|

Plastic, Visual and Audiovisual Education |

|

Music |

|

Introduction to entrepreneurial and business activity |

|

4th SECONDARY |

Geography and History |

Castilian Language and Literature |

|

Maths AC or AP |

|

First Foreign Language |

|

Physical Education |

|

Ethical Values or Religion |

|

Classical Culture |

|

Plastic, Visual and Audiovisual Education |

|

Music |

|

Galician Language and Culture |

|

Latin |

|

Information and Communication Technologies |

|

Technology |

|

Scientific Culture |

|

Biology and Geology |

|

Economics | |

Source: Compiled by author

Within these topics that include heritage in their study programmes, we highlight, as another result, some remarkable particularities:

With regard to the topics History and Geography, the use of the concept of heritage stands out, very close to the patrimonialization process, as a bridge between heritage and society, as part of citizenship:

In Spain: “Finally, a particular approach to artistic manifestations will be needed to signify the creative effort of the human being over time and, consequently, to value cultural heritage in its richness and variety” (History, First grade ESO, block 1, common content, p.32141); other evidence: “To value the cultural and artistic heritage as a wealth to be preserved” (History, First grade ESO, block 1, common content, p.32158).

In Portuguese law, the concept also comes close to this idea of symbolic appropriation of heritage: “Recognition of the marks left by the Phoenicians, the Greeks and the Carthaginians in the Iberian Peninsula, highlighting the major (technical and cultural) contributions of these civilizations to the enrichment of the peninsular cultures” (History and Geography of Portugal, 2nd cycle Basic Education., 2013, p. 5).

Moreover, in Portuguese law, in this matter, heritage is present from 11 to 16 years of age, whereas in Mexico it is discovered in the cycles from 11 to 14 and in Spain, as in Portugal, throughout the cycle from 11 to 16 years of age.

In the Anthropology subject in the 12th grade of the Portuguese educational system, which is the only subject that includes it, among the essential learnings that are promoted, the importance of patrimonialization processes stands out: “EA: Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes. The student must be able to: Distinguish patrimonialization processes and their different involvements with the populations that produce material cultural and immaterial practices” (Anthropology of Portugal, 12th course, 2013, p.6). In addition, this law speaks of a profile in which students are guided in this subject and in the use of ICT: “Strategic teaching actions aimed at the students’ profile”.

(Examples of actions to be developed in the subject): - Mapping heritage processes in Portugal (examples: Cola San Jan, Chocalhos, Fado) and ideally close to the local community; Finding videos on Youtube about patrimonialization processes: - Contacting researchers dedicated to patrimonialization processes” (p.7).

The fact that this subject was introduced in the Portuguese curricula helps the teaching- learning process at this age to implicitly involve heritage processes so that there is a symbolic appropriation of heritage. This heritage process is seen from three perspectives: institutional, cultural and community (Fontal and Gómez, 2015, p.91), through the teaching actions and strategies proposed in this essential learning, that is, with the use of active methodologies proposed for the development of competences in this subject.

The example of the topic History and culture of religions (Spain), very controversial due to its existence in the curricula of the successive Spanish reforms, is curious in its fifth assessment criterion in which the verb to bind is used for the sole and exclusive moment when speaking of heritage, related to the concept of heritage as a link between individual and object (Fontal, 2008; Calaf, 2009; Marín, 2013): “5. Valuing religious traditions, their cultural and artistic manifestations and the socio-cultural heritage they generated and with which they are linked” (LOMCE, Historia y cultura de las religiones, p.86). The remaining documents use other types of verbs: value, know, recognize, identify, respect, enjoy, or conserve.

And in the Portuguese topic Citizenship and Development (Portugal), values and cultural diversity are also mentioned: "In short, Citizenship and Development intends to contribute to the increase of attitudes and behaviours, dialogue and respect for others, based on ways of being in society that have human rights as a reference, especially the equality, democracy and social justice values” (EL: Secondary Education, p.6).

(…) in the Citizenship and Development (CD) component of the curriculum, the teachers have the mission of preparing students for life, to be democratic, participatory and humanist citizens, in a time of increasing social and cultural diversity, to promote tolerance and non-discrimination, as well as to eliminate violent radicalism (EL: Secondary Education, p.7).

In Mexico, within the topic of Civility and Ethics, the law clearly points out the relevance of indigenous culture as an important part of citizenship: “Indigenous education must meet the educational needs of indigenous people, peoples and communities with cultural and linguistic relevance; it must also be based on respect, promotion and preservation of the historical heritage and of our cultures” (LGE, Chapter 4, art. 56). However, little is specified about the methodology to be used or whether it is advisable to use ICT, as in the Portuguese case.

-And, within the topic of Secondary History in Portugal, we can highlight a study topic, Glocal (global+local) and heritage awareness, which was not identified in any Spanish or Mexican document: "Glocal and Heritage Awareness - enhances the experimentation of diversified techniques, instruments and ways of working, intentionally promoting, in the classroom or outside the classroom, observation activities, questioning of close and more distant realities from a perspective of knowledge integration (Perfil dos Alunos à Saída da Escolaridade Obrigatória, p. 31). However, what the new Spanish law assumes is the development of critical ability on ICT: “To develop basic technological competences and advance in an ethical reflection on their operation and use” (LOMLOE, Art.23.e, p.57).

In these very up-to-date concepts, it is assumed that heritage encompasses a great diversity of typologies and that it forms the cultural heritage of communities and minorities, both in the past and in the present. And heritage awareness comprises a large complex web of interculturality and identity in which each individual must take on the responsibility for their local or global civic action, that is, situated and contextualized.

In the study presented, we started from the basis proposed by the Council of Europe of a curriculum that is built before and during the teaching-learning process, throughout life, and that is shaped by the people who make decisions about it, each one with their own views and teaching experiences. The heritage education curriculum in the three countries studied, whose comparison becomes asymmetrical, is modelled, but not created, according to Fontal (2011), by professionals of subjects such as History and Geography, Arts, Language, Music, Civic Education, Values, Religion, or Citizenship, among others. And, according to Sacristán (2000), each curriculum promotes different content and internal management because it has different social functions. The concept of heritage found in this study is close to that of culture and art is close to the notion of UNESCO (2003), which advises us that heritage is important for the countries’ culture and development, contributing to the continuous reframing and revaluation of cultures and identities, while being an important vehicle for the transmission of experiences, competences and knowledge between generations, that is, in their education. However, it is a concept, in part, far removed from Fontal (2003), in which heritage is part of its environment and territory, in which an individual and collective affective connection is established for the formation of identities. The curriculum for this age group, between 11 and 16 years old in the three countries, does not specifically take into account the affective connections between people and their environments, territories and contexts, on which they later build their identities, a crucial issue in adolescence.

Given these results, it is necessary, on the one hand, as Madeira (2009) points out, to define the type of education that corresponds to each society through the comparative method and, at the same time, it is this method that allows us to decide which educational practice is appropriate for a given reality. Based on all of them and on the results, it is important to redefine the curricula of these countries in terms of heritage education, to broaden its concept and adapt it to new methodologies and ICT, to make agreements between educational agents on policies in this matter so that professionals from this transdisciplinary field can locate the broad, mediating, symbolic and binding notion of the concept of heritage.

However, to consolidate this hypothesis, it is necessary to pose more research questions in a comparative historical framework that allows us to find, for each space-time unit considered, the particular modes, modalities, institutions, strategies, responses and appropriations, from which such symmetries, patterns or inequalities can be introduced.

The curriculum of each country has its own peculiarities and, after making comparisons, we highlight a series of similarities with regard to heritage education in these studied stages: the notion of heritage in the three regulations is related to the concepts of culture, geography, society, artistic manifestation, documentary, natural, history, language, archaeology, music, folklore, indigenous and popular culture, as well as being related to citizenship, ICT, and globalization. In other words, a concept that relates to identity, the symbolic, the social and the human, a holistic and relational model. The asymmetries arise in the way the concept is dealt with in the topics that cover it in each country, or in the fact that, in Spain, for example, there are 17 educational rules that emanate from a common law, but that are adapted to the peculiarities of each Autonomous Community. In Mexico, however, we find 32 different states that follow the same common law, just like Portugal, which is governed by a national law agreed by the different regions and municipalities. It would be necessary to extend the study to a longitudinal level and with learning outcomes in the three countries.

We found that the problems that arise in this comparative work do not differ much on either side of the Atlantic. For this reason, intensifying the cooperation relationships among academic institutions through the integration of countries that share a common language and history with Portugal and Spain is an exceptional opportunity to analyse the expansion process of the European school model in colonial contexts and perhaps on its heirs. The consolidation of research networks, as in the case of this study, can contribute to revaluing, on a global scale, the specificity of the organization, construction and dissemination processes of the European school model on the other side of the Atlantic, with a special focus on the spaces occupied by shared languages and stories. Like Nóvoa (2005), we believe that it is this specificity of each country and culture that should be studied, that it is worth investing in. It is a complex challenge that articulates different fields of relationships, namely the political, social, cultural, epistemological aspects and the forum for the creation of scientific communities in different spaces.

This document is funded by national funds through FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, under project UIDB/04059/2020

Adamson, B., Forestier, K., Morris, P., & Han, C. (2017). PISA, policymaking and political pantomime: education policy referencing between England and Hong Kong. Comparative Education, 53(2), 192–208. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03050068.2017.1294666. Access on: 11 March 2022.

Calaf, R., (2009). Cuando el pasado y el presente se encuentran. Iber: Didáctica de las ciencias sociales, geografía e historia, 110–124.

Callon, M., Courtial, J.P. y Penan, H. (1995). Cienciometría, el estudio cuantitativo de la actividad científica: De la bibliometría a la vigilancia tecnológica. Gijón: Ediciones Trea.

Choay, F. (2001). A alegoria do patrimônio. Barcelona: Gustavo Gil, S.A.

Clark, D. T., Goodwin, S. P., Samuelson, T., & Coker, C. (2008). A qualitative assessment of the Kindle e-book reader: results from initial focus groups. Performance measurement and metrics, 9(2), 118–129. Available at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/14678040810906826/full/html?casa_token=mJnYqQOdOrkAAAAA:X0w01v_7ZBZ2tpLI0VJZTgTRgi4DgqQiwRLQiZ

_r3K78hTr_e8juX41D4Ll7OpFcuJ9AVvLro5JS5kLx4gpi7QxdweQW34o2u2dz0Bskk7cbrfE2Bfru. Access on: 11 March 2022.

Cuenca, J. M. y López-Cruz, I. (2014). La enseñanza del patrimonio en los libros de texto de Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia para ESO. Cultura y Educación: Culture and Education, 26 (1), 19–37.

Cuenca López, J., Martín Cáceres, M. y Schugurensky, D. (2017). Educación para la ciudadanía e identidad en los museos de Estados Unidos: Análisis desde la perspectiva de la educación patrimonial. Estudios pedagógicos (Valdivia), 43(4), 29–48. Retrieved from: https://scielo.conicyt.cl/pdf/estped/v43n4/art02.pdf

Creswell, J. W. (2014). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. SAGE publications: L.A, California. USA.

Ferreira, A. G. (2009). O sentido da educação comparada: Uma compreensão sobre a construção de uma identidade. In: Martinez, S. A., Souza, D. B. (Org.). Educação comparada: Rotas de além-mar, (p. 137–166). São Paulo: Xamã.

Flick, U. (2007). Introducción a la investigación cualitativa. Madrid: Morata.

Fontal, O. (2003). La educación patrimonial. Teoría y práctica en el aula, el museo e Internet. Gijón: Ediciones Trea.

Fontal, O. (2008). La importancia de la dimensión humana en la didáctica del patrimonio. In La comunicación global del patrimonio cultural (pp.79–110). Trea.

Fontal, O. (2011). El patrimonio en el marco curricular español. Patrimonio Cultural de España, 5, 21–44.

Fontal, O. (2012). Patrimonio y educación: Una relación por consolidar. Aula de innovación educativa, 208, 10–13.

Fontal, O. (Coord.). (2013). La educación patrimonial: Del patrimonio a las personas. Gijón: Trea.

Fontal, O. & Gómez-Redondo, M. D. C. (2015). Evaluación de programas educativos que abordan los procesos de patrimonialización. [Tesis doctoral]. Universidad de Valladolid.

Fontal, O. e Ibáñez-Etxeberria, A. (2017). La investigación en Educación Patrimonial. Evolución y estado actual a través del análisis de indicadores de alto impacto. Revista de Educación, 375(1), 84–214. Retrieved from: https://uvadoc.uva.es/bitstream/handle/10324/54146/La-investigacion-en-Educacion-Patrimonial.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Fontal, O., Sánchez-Macías, I., y Cepeda, J. (2018). Personas y patrimonios: análisis del contenido de textos que abordan los vínculos identitarios. MIDAS. Museus e estudos interdisciplinares, (Varia), 9, 1–18. Retrieved from: https://journals.openedition.org/midas/1474

Fraser, B.J. (1964). Jullien’s plan for comparative education 1816-1817. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University.

Gil Pascual, J. A. (2011). Metodología cuantitativa en educación, n. 37 370, e-libro.

Gobierno de España. Ley Orgánica 8/2013, de 9 de diciembre, para la Mejora de la Calidad Educativa. LOMCE. BOE nº 295 de 10/12/2013, páginas 97858 a 97921. Retrieved from: http://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2013/12/10/pdfs/BOE-A-2013-12886.pdf

Gobierno de España. Subdirección General del Instituto del Patrimonio Cultural de España. Plan Nacional de Educación y Patrimonio. Editora: Secretaría General Técnica. Centro de Publicaciones. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, 2015. Retrieved from: https://sede.educacion.gob.es/publiventa/plan-nacional-de-educacion-y-patrimonio/patrimonio-historico-artistico/20704C

Gomes, I. (2017). The scientific heritage of Portuguese secondary schools: A historical approach. Paedagogica Historica, 54(4), 468–484. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1080/00309230.2017.1409771

Hanson, W. E., Creswell, J. W., Clark, V. L. P., Petska, K. S., & Creswell, J. D. (2005). Mixed methods research designs in counseling psychology. Journal of counseling psychology, 52(2), 224–235. Retrieved from: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.224

Ibáñez-Etxeberria, A., Asensio, M. y Correa, J. M. (2012). Mobile learning y patrimonio: Aprendiendo historia con mi teléfono, mi GPS y mi PDA. En: A. Ibáñez-Etxeberria, (Ed.). Museos, redes sociales y tecnología 2.0. (pp.59–88), Zarautz: EHU.

Jullien, M.A. (1817). Esquisse et vues préliminaires d'un ouvrage sur l'éducation comparée. Chez L. Colas, imprimeur.

Junta de Castilla y León, Consejería de educación. DECRETO 52/2007, de 17 de mayo, por el que se establece el currículo de la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria en la Comunidad de Castilla y León. (España), 2007. Retrieved from: https://www.educa.jcyl.es/educacyl/cm/educacyl/tkContent?idContent=11112

Leydesdorff, L. & Welbers, K. (2011). The semantic mapping of words and co-words in contexts. Journal of Informetrics, 5, 469–475. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1751157711000095

Lourenço, M. (2009). O patrimônio da ciência: Importância para a pesquisa. Museologia e Patrimônio, 2(1), 47–53.

Madeira, A. I. (2009). O campo da educação comparada: Do simbolismo fundacional à renovação das lógicas de investigação. In: Martinez, S. A. y Souza, D. B. (Org.). Educação comparada: Rotas de além-mar (pp. 105–136). São Paulo: Xamã.

Marín, S. (2013). Una nueva geografía patrimonial: la diversidad, la psicología dle patrimonio y la educación artística. Educación artística: revista de investigación, 4, 217–224.

Meyer, J. W. y Ramírez, F. O. (2002). La institucionalización mundial de la educación. In Schriewer, J. (Coord.). Formación del discurso en la educación comparada (pp. 91–111). Ediciones Pomares-Corredor.

Mota-Almeida, M., Fernández, C. y Mendes, C. (2020). O Plano de Valorizaçao do Património Cultural da Escola Secundária Sebastiao e Silva, Oeiras. Conservar Patrimonio, 33, 44–52. Retrieved from: http://revista.arp.org.pt/pdf/2018041.pdf

Nóvoa, A. (1998). Relação escola-sociedade: Novas respostas para um velho problema. Formação de professores. São Paulo: UNESP.

Nóvoa, A. (2005). Les états de la politique dans l’espace européen de l’éducation. LAWN, M. Oriá, R. (2005). Ensino de História e diversidade cultural: Desafios e possibilidades. Cadernos Cedes, 25(67), 378–388. Retrieved from: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/ccedes/v25n67/a09v2567.pdf

OCDE, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, (2013).. PISA 2012 results: What makes a school successful (volume IV): Resources, policies and practice. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/9789264201156-en

OCDE, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, (2016). PISA 2015: Results in focus. PISA.

Pires, M. L. B. (2000). Robert Louis Stevenson: Tusitala, o contador de histórias. Lisboa: Universidade Aberta, Portugal.

Quiroga, S. E. (1999). Adolescencia: Del goce orgánico al hallazgo de objeto. Buenos Aires: Eudeba. Buenos Aires, Argentina.

República Portuguesa. Direçao-General da Educaçao. (1986). Lei de Bases do Sistema Educativo. Lei n.º 46/1986, de 14 de outubro. Retrieved from: https://dre.pt/web/guest/pesquisa//search/222418/details/normal?p_p_auth=D688OvBC

República Portuguesa. Direçao-General da Educaçao. (2018). As Aprendizagens Essenciais (AE) referentes ao Ensino Básico são homologadas pelo Despacho n.º 6944-A/2018 , de 19 de julho.

República Portuguesa. Direçao-General da Educaçao. (2018). As Aprendizagens Essenciais (AE) referentes ao Ensino Secundário são homologadas pelo Despacho n.º 8476-A/2018, de 31 de agosto.

Sacristán, J. G. (2000). El sentido y las condiciones de la autonomía profesional de los docentes. Revista Educación y Pedagogía, 12(28), 9–24. Retrieved from: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2562948

Schriewer, J. (2009). Aceitando os desafios da complexidade: metodologia de educação comparada em transição. In: Martinez, S. A.; Souza, D. B. (Org.). Educação comparada: Rotas de além-mar (pp. 63–104). São Paulo: Xamã.

Sobe, N. W. (2018). Problematizing comparison in a post-exploration age: Big data, educational knowledge, and the art of criss-crossing. Comparative Education Review, 62(3), 325–343. Retrieved from: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/698348

Tajfel, H. (1978). Differentiation Between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. New York: Academic.

Trabajo, M. Y López, I. (2019). Implementación del programa Vivir y Sentir el patrimonio en un centro de Educación Secundaria. Un mar de Patrimonio. Ensayos, Revista de la Facultad de Educación de Albacete, 34(1), 55–66. Retrieved from: https://revista.uclm.es/index.php/ensayos/article/view/2019

UNESCO, Conferencia General de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura, (2003). Convención para la Salvaguarda del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved from: https://ich.unesco.org/es/convención#art2

Unión Europea, European Anti Poverty Network, EAPN, (2009). Informe INCO: Consulta sobre la futura estrategia UE 2020 (Comisión de las Comunidades Europeas). Red Europea de Lucha contra la Exclusión Social en el Estado Español. Retrieved from: https://www.eapn.es/publicaciones/91/consulta-sobre-la-futura-estrategia-ue-2020-comision-de-las-comunidades-europeas

Van Eck, N. & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84(2), 523–538. Retrieved from: https://akjournals.com/view/journals/11192/84/2/article-p523.xml

Contact address: Inmaculada Sánchez Macías. Universidad de Valladolid-Campus de Segovia, dpto. Didáctica de la Expresión Musical, Plástica y Corporal. Facultad de Educación de Segovia. Plaza de la Universidad 1, 40001 Segovia, España, e-mail: inmaculada.sanchez.macias@uva.es