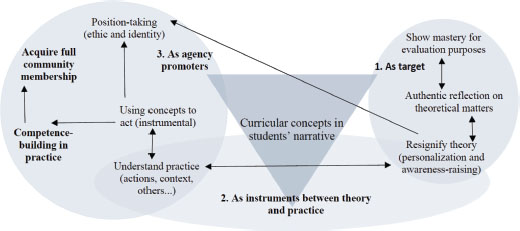

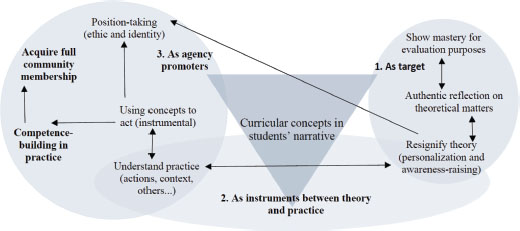

FIGURE I. Functions of curricular concepts in SL narratives

Source: Compiled by authors.

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2024-404-618

David García-Romero

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8957-3782

Universidad de Santiago de Compostela

Beatriz Macías-Gómez-Estern

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4952-1811

Universidad Pablo de Olavide

Virginia Martínez-Lozano

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2426-6255

Universidad Pablo de Olavide

José Luis Lalueza

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0897-9917

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Abstract

We explored the potential of Service-Learning (SL) as a methodology for authentic learning, understood as that which occurs in real situations with real problems, leading to the acquisition of holistic learning that will generate personal transformations. To this end, we conducted research with students involved in similar SL experiences at two universities. The experience consisted of complementing teaching with collaboration for a semester in highly complex schools, with a majority Roma population. In both universities the subjects involved followed similar structures. Four studies were developed with mixed methodology. Two quantitative studies compared students who had undergone the SL experience with control groups who had taken the subject with traditional methodologies. The Course Value Inventory translated into Spanish was applied to check whether participation in SL generated differences in the three dimensions of learning: conceptual, procedural and personal. The two qualitative studies explored in depth the differences found in the previous studies by analysing the field notes generated by the students. The first qualitative study focused on analysing the acquisition and appropriation of the classes’ theoretical contents and the other on the processes underlying the identity and personal changes taking place. The quantitative studies yielded significant differences in the self-perception of the learning achieved, in both universities. The qualitative studies showed the importance of psychological tools and personal relationships for authentic learning, highlighting the importance of considering the SL experience as a frontier space of learning generated by new participants, new goals and new tools.

Keywords: higher education, service-learning, authentic learning, identity, social participation.

Resumen

Exploramos el potencial del Aprendizaje-Servicio (ApS) como metodología para el aprendizaje auténtico, entendido como aquel que ocurre en situaciones reales con problemas reales, dando lugar a la adquisición de aprendizajes holísticos que van a generar trasformaciones personales. Para ello realizamos una investigación con estudiantes implicados en experiencias similares de ApS de dos universidades. La experiencia consistía en complementar la docencia con la colaboración durante un semestre en escuelas de alta complejidad, con población mayoritariamente de etnia gitana. En ambas universidades las asignaturas implicadas seguían estructuras similares. Se desarrollaron cuatro estudios con metodología mixta. Dos estudios cuantitativos compararon estudiantes que habían pasado por la experiencia de ApS con grupos control que habían cursado la asignatura con metodologías tradicionales. Se aplicó el Course Value Inventory traducido al castellano, con el objeto de comprobar si la participación en ApS generaba diferencias en las tres dimensiones del aprendizaje: conceptual, procedimental y personal. Los dos estudios cualitativos analizaron en profundidad las diferencias encontradas en los estudios anteriores a través del análisis de los diarios de campo generados por el alumnado. El primer estudio cualitativo se centró en analizar los procesos de adquisición y apropiación del contenido teórico de las asignaturas y el otro en los procesos subyacentes a los cambios identitarios y personales que se estaban produciendo. Los estudios cuantitativos arrojaron diferencias significativas en la autopercepción de los aprendizajes realizados, en ambas universidades. Los estudios cualitativos mostraron la importancia de los instrumentos psicológicos y las relaciones personales para el aprendizaje auténtico, destacando la importancia de considerar la experiencia ApS como espacio fronterizo de aprendizaje generado por nuevos participantes, nuevas metas y nuevas herramientas.

Palabras clave: educación superior, aprendizaje-servicio, aprendizaje auténtico, identidad, participación social.

One line of debate on the mission and meaning of learning at university level is located at the tension between focusing on the efficiency of students’ professional training and endowing the learning experience with meaning and significance for each learner and for social change (García-Romero et al., 2018; Manzano-Arrondo, 2012). Thus, throughout history there have been numerous teaching methodologies proposed committed to transformative logics, both for the learner and for society. This is the case of Dewey’s experiential learning (1936), Freire’s critical theory (2000), Vygotsky’s historical-cultural perspective (1978) or the more recent Social Design Experiments (Gutiérrez & Vossoughi, 2010) and service-learning (Taylor, 2017). These proposals, which focus on developing processes that are meaningful to the learner and coherent with the world in which they live, show a concern for understanding how learning is meaningful throughout life, in an attempt to bring classrooms into reality, and reality into the classroom.

The purpose of this paper is to reflect on the learning process that takes place through the service-learning (SL) methodology, defined as a training tool that integrates academic study with participation in community practice, in order to give meaning to academic content and at the same time generate processes of transformation and social change (McMillan et al., 2016). For the past two decades, this methodology has been experiencing increasingly rapid growth, as shown by systematic reviews conducted internationally (Sotelino et al., 2021) and nationally within Spain (Redondo-Corcobado & Fuentes, 2020). Specifically, on the subject of the impact of service-learning on the student body, we find studies aimed at analysing the impact of SL on cross-cutting competences such as group work, empathy and critical thinking (Blanco-Cano & García-Martín, 2021; Santos-Rego et al., 2022), as well as on identity-related aspects such as commitment or social justice (Asenjo et al., 2021; Jiménez-Jiménez et al., 2021).

One concept that allows us to address the different dimensions of student learning is that of authentic learning, a concept already used in some studies on SL (Marco-Macarro et al., 2016; Santos-Rego et al., 2022). This concept overcomes the existing duality between formal knowledge and contextual knowledge, understanding it as that which occurs within the development of an authentic task, directly connected with current human needs (Duman & Karakas-Ozur, 2020). This leads us, again following Dewey (1936), to a conception of learning as another dimension of life and not just a preparation for the future. Similarly, cultural-historical psychology argues that one key to learning is that a person’s development must be in response to real needs and, therefore, be based on genuine problems and questions embedded in cultural practices (González, 2009). Thus, authentic learning is learning that is situated and developed in a goal-directed collective activity (Vygotski, 1978), provides learners with a context (Duman & Karakas-Ozur, 2020) and has a purpose that is socially relevant (Velázquez-Rivera et al., 2020).

Consequently, the authentic learning process transcends the teacher-learner dyad and involves a wider community, a real audience where the motives for learning do not respond only to individual purposes but are framed in the social sphere (Guerrero-Rodríguez et al., 2014; Velázquez-Rivera et al, 2020). And this is where critical theories converge, which argue that it is through the awareness of social meaning that the learner establishes a relationship of commitment to the learning objectives and to learning itself (Freire, 2000), as they become able to make personal and immediate contributions valuable for a group of people. The progressive participation of the learner in a cultural practice will generate the development of commitment to it and to the people included in it, resulting in a change in their relationship with the world and in the way they perceive themselves as a person (Macías-Gómez-Estern et al., 2014; Wenger, 2001). The holistic process that includes these dimensions necessarily involves a reflective activity (Duman & Karakas-Ozur, 2020) in which the learner moves between the consideration of new conflicts and uncertainties, their problematisation and their resolution, where reconfigurations and changes are articulated. Thus, both the learner’s agency and the human relationships established are the pivots for the whole learning process.

To summarise, the concept of authentic learning can account for the processes that occur in SL educational practices as an experience that puts the learners at the centre of a real, complex and intercontextual learning process, while placing them in a hybrid activity setting between academic activity and community practice (McMillan et al., 2016). This setting provides real motives and goals that give meaning to learning, while generating personal commitments and positioning. All of this will anchor the acquisition of competences that, as the afore mentioned studies have shown, coincide with the three main dimensions of learning: conceptual, procedural and attitudinal.

The results of two quantitative and two qualitative studies carried out in the framework of the project “Analysis of the process of learning and identity change through service-learning in communities of practice in contexts of exclusion” are presented below, which aim to illustrate the authentic learning process that takes place within the framework of SL.

The research is based on a mixed methodological approach, already used in other studies on SL (Capella-Peris et al., 2020). It sets out to answer the following questions: a) Does participation in SL projects generate differences in learning between students who have undergone SL experiences and those who have not? And b) If such a difference exists, how does this participation operate in conceptual learning processes, and how are personal changes related to this type of learning?

To answer the first question, a quantitative study was developed comparing students who had undergone SL experiences with another group working through traditional methodologies. A qualitative approach, on the other hand, was only used with students participating in SL.

The participants were students from the Faculty of Social Sciences at Universidad Pablo de Olavide, studying the subject Fundamentals of Human Psychological Functioning, and from the Faculty of Psychology at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, studying Developmental Psychology. The teachers of these subjects were part of the research team of this project. In both cases, the SL project involved collaborating with highly complex schools located in socially vulnerable environments, with a majority Roma population. The university students attended two hours a week for a semester to carry out joint tasks with primary school students. In addition to the collaboration with the schools, the students kept a field journal of each of the sessions, reflection sessions were held with the teacher-researcher, and a final evaluation report was drawn up. The students who did not participate in the SL experience followed traditional methodologies, carrying out their practices through classroom seminars, analysing case studies and reading documents, and producing a final report.

The common antecedent for the SL projects at both universities were the Fith Dimension (Cole & The Distributed Literacy Consortium, 2006; Lalueza et al., 2020) and La Clase Mágica (Vásquez, 2003) models. These projects emerged in the USA and have been constituted as teaching, research and community service environments where reciprocal relationships are established between participants, enabling mutual learning while generating processes of social change and transformation (Underwood et al., 2021).

We used the Course Value Inventory (Nehari & Bender, 1978) translated into Spanish to test whether participation in SL generated differences in learning. This instrument, whose learning dimensions coincide with those found in existing research (Macías-Gómez-Estern et al., 2014), had previously been used in other studies that analysed SL experiences (Conway et al., 2009; Shek et al., 2020). The questionnaire consists of 36 items grouped into 4 scales, which assess students’ perceptions of their learning experience in: 1) the course in general, related to overall satisfaction; 2) conceptual learning, referring to the understanding of course content; 3) behavioural learning, referring to procedural and professional learning generated; 4) personal learning, related to the students’ identity constructions. Each subscale consists of 9 items that correspond to sentences that students must evaluate on a 4-point scale indicating whether it is: 4. positively true, 3. probably true, 2. probably false or 1. positively false. No neutral option was given. The item scores, as well as the scores for each subscale - with polarity adjustment - were used to compare the results between the two groups. In Table I, a sample item describes each subscale of the CVI.

TABLE I. Sample items of the subscales of the Course Valuing Inventory (CVI)

Course evaluation |

I consider this learning experience as time and effort well spent. |

Conceptual learning |

This course has helped me to acquire important information. |

Personal learning |

In a way, I feel good about myself because of this course. |

Behavioural learning |

This course has been useful for me in developing new ways of learning. |

Source: Compiled by authors.

Each university carried out a study, comparing two groups from the same subject and with the same teaching staff. One group was taught through SL methodology (SL-group) and the other through traditional classroom methodology (non-SL-group). The selection of the samples was thus intentional and non-probabilistic.

The total sample of Universidad Pablo de Olavide taking the subject in the first semester of 2015-2016 was made up of 179 students, 74 following the SL methodology (41.3%) and 105 following a traditional methodology (58.7%). In Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona data were collected from 174 students, 68 SL (39.1%), from three groups that had undergone SL experiences in three different periods (SL Group 14-15A in the first semester of the academic year 2014-2015; SL Group 15-16A in the first semester of the academic year 2015-2016; SL Group 15-16B in the second semester of the academic year 2015-2016), and 106 that followed the traditional methodology (60.9%), from a single group in the first semester of the academic year 2014-2015. The age of the students in both samples ranged from 18 to 25.

The CVI was administered as an anonymous survey after the end of the first semester classes. The two studies were conducted and analysed separately.

Quantitative data were processed using SPSS software, MANOVA-one-way, ANOVA and Chi-Square analyses.

For the qualitative study, the field notes prepared by each student throughout the semester were analysed (Lalueza & Macías-Gómez-Estern, 2020). Each student wrote between 9 and 10 field notes according to a script provided by the teaching staff. It included: general data on the visit (author, date, class group, participants, space), general observation (descriptive overview of the social climate and physical environment of the session), focused observation (detailed description of the behaviours and interactions, with the explicit instruction not to make subjective interpretations or assessments) and theoretical and personal reflection (where they related the contents of the subject with the experience of the activity, together with emotions, sensations or personal interpretations of their own learning processes and the dynamics observed). Students received feedback with their first marks from the teaching staff.

The field notes of the students who had completed them, a total of 66 students (32 from Universidad Pablo de Olavide and 34 from Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona), were followed up. After a first overall reading, the journals of 28 students (14 from each university) were selected for an in-depth analysis with the support of Atlas.ti 7 software, as they offered the most complete information, developing the theoretical and personal reflection parts more extensively.

For the analysis, we began by partitioning each text into units of meaning, through cycles of coding, until properties emerged that allowed us to construct our own categories, ensuring that they conformed to the definitions of validity (Martínez & Moreno, 2014). We proceeded as follows: a) Familiarisation: two people from each university reviewed all the field notes to formulate basic ideas and questions to be answered in relation to the research; b) Coding and categorisation: classification of the data into categories; c) Piloting of the category system and sharing: a random sample of journals was distributed so that each was read by two people; the categories that emerged within each pair were compared until agreement on definitions was reached; this was followed by team-wide sharing until a single set of categories and their definitions were reached; d) Using a different sample of field notes, it was confirmed that each coding pair had an agreement rate above the 90% criterion; e) Coding and categorisation: all texts were re-distributed for coding according to the developed category system; f) Integration: the results were analysed on the basis of the guiding research questions.

We obtained 25 different categories that were grouped into the three macro-categories detected in previous studies (Macías-Gómez-Estern et al. 2014): conceptual learning, procedural learning and attitudinal learning or processes of identity change (see Table II).

TABLE II. Schematic summary of the developed category system

CONCEPTUAL LEARNING |

1.1. Theoretical learning |

||

1.2. Theoretical and practical learning |

|||

1.3 Application of theoretical knowledge to practice |

|||

1.4. Inappropriate content |

|||

2.PROCEDURAL LEARNING/ PROFESSIONAL |

2.1. Communication and information strategies |

||

2.2. Conflict management |

|||

2.3. Analytical observation |

|||

2.4. Intervention in thinking and learning processes |

|||

2.5. Register of procedures |

|||

2.6. Teamwork |

|||

3.PROCESSES OF IDENTITY CHANGE |

3.1. Taking the initiative |

||

3.2. Self-awareness |

3.2.1. Emotional states |

||

3.2.2. Self-awareness |

|||

3.2.3. Awareness of the learning/identity process |

|||

3.3. Knowledge of the other/alterity |

3.3.1. Reality check |

||

3.3.2. Awareness of the cultural other |

|||

3.3.3. Knowledge of the interpersonal other |

|||

3.3.4. Prejudices/ stereotypes |

3.3.4.1. Emission of prejudice |

||

3.3.4.2. Challenging prejudice |

|||

3.4. Proximity and identification with the other professional |

|||

3.5 Commitment |

|||

Source: Compiled by author.

In a second phase, the results of the conceptual and identity learning categories were analysed in depth and separately. For the conceptual analysis, the 28 selected field notes were examined in an attempt to analyse the role of curricular learning as artefacts mediating participation in practical experience. For the analysis of personal learning, the changes experienced by the students in relation to otherness and their own identity were investigated, for which an intensive narrative study was carried out of the field notes of 2 students, one from each university, with the aim of gaining in-depth knowledge of the personal transformations generated by the experience. These cases were selected for the density of their narratives, as well as for the way in which each illustrated two different types of identity trajectories found in our student body as a whole.

Quantitative analysis showed significant differences in the self-perceptions of SL and non-SL students about their learning in their subjects.

In the study of the Universidad Pablo de Olavide (Macías-Gómez-Estern et al, 2019) a one-way MANOVA analysis was used to analyse the overall differences between groups. Subsequently, an ANOVA was used to compare the scores obtained in each of the four subscales (table III). Significant results were found for both the overall score and the four subscales, with the SL group showing a better evaluation of the course in all the categories considered. Using Chi-square, a third analysis was carried out, which informed us about which items made the differences.

TABLE III. Scores of the ANOVA of the Universidad Pablo de Olavide study

|

Group |

N |

M |

S.D. |

P |

Stage2 |

Full scale CVI |

SL |

74 |

29.69 |

3.34 |

< .001 |

0.26 |

Non-SL |

105 |

23.17 |

9.91 |

|

|

|

Total |

179 |

25.87 |

8.50 |

|

|

|

Course evaluation |

SL |

74 |

31.95 |

4.16 |

< .001 |

0.27 |

Non-SL |

105 |

24.89 |

10.84 |

|

|

|

Total |

179 |

27.81 |

9.37 |

|

|

|

Conceptual learning |

SL |

74 |

30.34 |

3.86 |

< .001 |

0.25 |

Non-SL |

105 |

24.15 |

10.39 |

|

|

|

Total |

179 |

26.71 |

8.87 |

|

|

|

Personal learning |

SL |

74 |

27.76 |

3.52 |

< .001 |

|

Non-SL |

105 |

21.38 |

9.41 |

|

|

|

Total |

179 |

24.02 |

8.17 |

|

|

|

Procedural learning |

SL |

74 |

28.73 |

3.64 |

< .001 |

|

Non-SL |

105 |

22.26 |

9.69 |

|

|

|

Total |

179 |

24.93 |

8.39 |

|

|

Source: Compiled by authors.

The results showed significant differences in 6 items in the subscale of overall assessment of the course, 2 in the subscale of conceptual learning, 2 in the subscale of professional learning and 7 in the subscale of personal learning. The items that marked differences in subscale 1 were related to the relevance of the experience; the assessment of the course as constructive and enriching; the assessment of the time and effort spent; and the statement that they would recommend the course to their peers. In the subscale of their assessment of conceptual learning, the students in the SL group highlighted that the course had helped them to understand the contents better and to consider them in a different and more clarifying way. In the subscale of personal learning, the students in the SL-group highlighted the positive impact of the course on their values, feelings and emotional reactions; the help the course gave them in terms of clarifying their personal views and increasing their sensitivity, tolerance and empathy towards others; and, finally, the greater impact of the course on their personal growth. Finally, the behavioural learning subscale showed significant differences in the items highlighting the usefulness of the course in their learning and in their lives in general. No significant differences were found between genders or between students with and without previous volunteering experience.

The analyses the results of Universitat de Barcelona (García-Romero et al., 2018), a comparison of means and an ANOVA were carried out, which showed significant differences both in the questionnaire as a whole and in almost all the subscales (table IV). In the subscale on general assessment of the course, SL students showed a greater positive affective involvement with the course. The subscale analysing personal learning showed the greatest differences, with perceptions indicating that the SL experiences had brought about relevant personal changes, related to self-knowledge, commitment and attitudinal changes. The results of the behavioural learning subscale showed that SL students perceived a greater and better acquisition of professional competences and skills than the non-SL group. Finally, the conceptual learning subscale was where the fewest differences were found between the four groups, although calculating the joint average of the three SL groups showed scores that exceeded those of the traditional methodologies group.

TABLE IV. Mean scores of the Universitast de Barcelona sample

Groups |

Full scale CVI |

Course evaluation |

Conceptual learning |

Personal learning |

Procedural learning |

SL 14-15A |

2.262 |

2.656 |

2.115 |

2.000 |

2.336 |

SL 15-16A |

2.180 |

2.495 |

1.913 |

2.165 |

2.136 |

SL 15-16B |

2.226 |

2.534 |

2.119 |

2.091 |

2.211 |

Non-SL 1415A |

1.757 |

1.972 |

1.923 |

1.433 |

1.715 |

Source: Compiled by authors.

In short, in both studies the results confirmed our initial hypothesis about the differences that students perceive in their learning depending on the methodologies used in the subject, with the SL groups showing the highest levels of satisfaction.

Once these data were obtained, the aim of the research was to analyse the learning processes that took place through the P2P experiences. The following sections show the results obtained by analysing, on the one hand, the conceptual learning processes that take place through SL and the role they play in participation in the practical activity (García-Romero & Martínez-Lozano, 2022) and, on the other hand, the impact that participation in these SL experiences has on the identity processes of students (Lalueza & Macías-Gómez-Estern, 2020).

If we look at authentic learning as holistic change, we must understand the role of disciplinary knowledge promoted in the subjects students study, and this is the focus of our third study (García-Romero & Martínez-Lozano, 2022).

From a historical-cultural perspective, we start from the dialectical relationship between theory and practice (Taylor, 2014). A dialectical process in which reflection, understood as the mental activity dedicated to understanding uncertain situations or resolving incoherence (Clarà & Mauri, 2010), plays a fundamental role. Through reflection, new significant learning emerges. Service-learning contexts involve a boundary activity where two activity systems with parallel historical developments converge, often involving inconsistencies in their norms, roles and even worldviews (McMillan et al., 2016). These uncertain situations need to be confronted by students, leading to reflective processes of negotiating meanings that smooth out contradictions (Kiely, 2005).

This study analyses the students’ field notes in which we find the account of this reflective activity, where the personal processes of negotiation and learning that lead to understanding the curricular concepts taught in class are recorded, so that they can be applied in practice. The results (García-Romero & Martínez-Lozano, 2022) showed that the role played by the contents as mediators of the practice is in itself very diverse, in accordance with the plurality of motives that guide each person and the different degree of participation they develop in the experience (figure I).

FIGURE I. Functions of curricular concepts in SL narratives

Source: Compiled by authors.

At a first level, students wrote down the definition of the concept in their notes, with the main purpose of passing an assessment, in line with the requirements of a traditional model of learning by transmission. Therefore, the concepts were used here only as objects of their own reflection, constituting the ultimate purpose of the latter. Below is an example from one of the field notes analysed:

“Lalueza et al. (2001): their socialising practices are based on children’s participation in the social world and on guided learning techniques. (Ana1, note2, 4th year, Psychology)

On a different level, although the concepts occupied the same role as the object of conceptual reflection, a relationship was established with experienced practice, giving examples, contextualising them and providing them with concreteness in order to deepen and resignify the concept, informing us of a genuine interest in the theory itself, but with an interest in appropriating it, an equally relevant aspect in the academic community. Below is an example taken from a focus group participation:

“It’s very difficult to decipher … the concept of ‘socialisation’. I didn’t understand it, so I started to do some research, and then I related it to the school, to how these children have a different socialisation to ours because they were born where they were.” (Maricarmen, Note7, 1rst year, Social Education)

On the other hand, curricular concepts also appear as psychological artefacts that mediated understanding of the complex, new and uncertain reality in which one is participating. Here, the purpose of concept use is not about assessment, but about a need to understand and orient oneself when participating in a meaningful social practice (Primavera, 2021). Concepts stand as frameworks for understanding both their own participation and experience and the new context in which they find themselves, as well as the relationships with the actors involved (Schön, 1987). This use of concepts is particularly relevant, as this need to understand what is happening has an important implication for students’ learning and competence as new participants in the community who want to contribute to collective goals and be legitimised by their peers. In short, it shows us the role of curricular concepts as promoters of agency processes. Below is one example where this is made very explicit:

“Having made a prior diagnosis of the class helped me to get to know them even better and to set the goals I wanted to achieve. In other words, I was able to detect abilities and needs that I was unaware of before; I became aware of the priorities of each student and so I was able to set the objectives I considered appropriate. (Esther, Note 4, 4th year, Psychology)

We thus see how, in a situation where initiative and action are required, the conceptual tools that serve to understand practice also enable decisions to be made about which procedures and actions to implement. Thus, we find narratives in which students legitimise their actions based on these curricular concepts, which allows them to participate more centrally and fully in practice (Wenger, 2001). This transition in their participation implies a commitment to the collective objectives, as well as to the different people involved in the activity, a commitment that involves enabling new identity positions on the part of the participating students, often confronting their own implicit theories and re-signifying them to adjust them to the new knowledge and experience. In this process, the new concepts they learn related to the lived context remain imbued with ethical and political values, assuming an important role in the awareness-raising process, a fundamental aspect in a genuine education process (Matusov et al., 2016). We can see it here:

What makes us afraid to express what we feel is the consequences. As we can see in the book Summerhill, if children are aware that a teacher is “superior”, simply because she is a teacher and older, they will not reveal themselves as they really are and will be afraid of the repercussions of saying what they think, for fear of punishment, failure and countless other things. That is why we must fight so that children do not see us as their superiors; we are all people with equal rights and equal duties, free to express what we feel, and we should not be inhibited by the consequences of our thoughts. FREE EDUCATION is the basis of our future to be formed as real people. (Raquel, Nota8, social education)

A second qualitative study was carried out on the impacts experienced by students participating in SL projects on their personal learning processes, focusing on the trajectories of two students whom we tracked through an identity “border crossing” elicited by the educational experience of SL itself.

The idea of “border crossing” (Kiely, 2005; Naudé, 2015) is a metaphorical way of looking at a change in the subjective world of the learner. This change occurs as a result of the incursion into a context that is different from one’s own, with different assumptions, norms, values and routines. It is an opportunity for transformation as the learner ‘denaturalises’ their own position by re-situating it in a more complex cultural and interactional universe. The result is not only an entry into a different world ‘on the other side of the border’, but also, and above all, the opportunity for introspection and self-knowledge.

In a very similar way to this trajectory identified by Kiely (2005) and Naudé (2015), our students go through different processes from the first moment of contact with practice, when they arrive at a school with children belonging to a cultural community that is alien to them, and with which they must collaborate to achieve predetermined goals. Thus, in their field notes, they report moments dominated by dissonance, in which they show surprise, discomfort and disagreement with certain practices of the students, their families or the school itself:

Soledad told me to go down to the secretary’s office to call the mother back so that she could come and visit the school and talk to her daughter. However, the answer she gave to the secretary on the phone was: ‘I’m not coming because I’m making lunch’. (Maria, note1, social education)

In both students, these dissonances spark processing or reflection, i.e., conscious attempts to make sense of practices that seem strange to them.

This is perhaps to me, having been brought up under the premise that school is a fundamental element for the physical, social and psychological evolution and development of the person, the fact that an 11-year-old pupil has been absent from school for three weeks in a row is anomalous and alarming. So, at this point I try and try not to be carried away by my beliefs, but to keep in mind that Roma culture as Lalueza et al. (2001) explains ‘their socialising practices are based on the participation of children in the social world and on guided learning techniques…” (Paula, note 7, psychology).

This processing takes place on two parallel planes, an intellectual plane of distancing from the object, and another plane catalysed by a process of personalisation, in which the people with whom they carry out the tasks (mainly boys and girls, but also teachers and fellow trainees) “take shape” through the relationship. Explicitly in the field notes, the weaving of affections is reported, as well as approximations that allow us to understand the motives and justifications for their behaviour. This affective connection between the students and the ‘subjects’ of the intervention, ‘the others’, appears in both cases as the prelude to the development of agency and commitment to the activity.

“I have been very moved by the change that we have all undergone during these months, the transformation of some students who did not know what their future would be like and are now fighting to become policemen, firemen, teachers… Without forgetting their essence as children and looking to the future with perspective (María, note 10, social education)”.

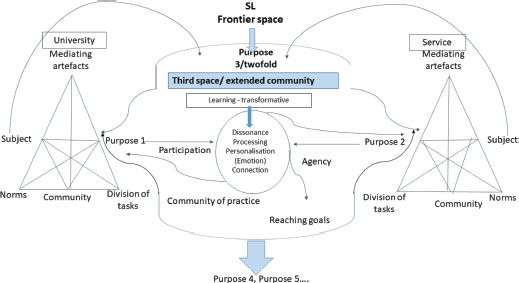

Our analysis (Macías-Gómez-Estern & Lalueza, 2024) thus illustrates the complex interweaving and synchrony between individual, social, affective and interactive processes involved in achieving boundary crossing in SL projects. These two cases were chosen because they offer two distinct and paradigmatic crystallisations of the processes we have found in our student body as a whole. Each of them shows a different trajectory, as their starting conditions (age, academic experience, narrative style, etc.) and the characteristics of the activity scenario in which they participated (differences in the organisation of the projects, in the role expected of them, in the models of action present) are different. However, in both cases there are iterations of the same process of identity change and “border crossing”, forging transformations both in themselves and in the scenarios in which they participate. In the narratives of both we find some elements that give content to the processes involved in identity change, such as the processes of dissonance, processing, personalisation and connection. Firstly, in both cases, the emergence of intense emotions (frustration, commitment, etc.) constitutes the first element of dissonance, which elicits transformative learning. However, this is not enough for “border crossing” to take place. It is necessary for the tools of the hybrid system of activity in which they are inserted to come into play so that it can be processed and personalised (through, among others, reflective writing as part of the didactic methods of SL), progressively giving rise to greater agency in this hybrid scenario. The SL scenario analysed then takes on the characteristics of what other authors have called a “third space” (Gutiérrez & Vossoughi, 2010), where norms, values and ways of doing, coming from different cultural traditions and practices, connect, converge, are legitimised and put into interaction, forming a new place as a result of the participation of all the subjects involved.

In summary, the internal processes of identity transformation in the two students analysed involve a dialectical view of what happens in the SL scenario, in which the change in subjectivities occurs as a result of motivated participation in a goal-directed activity in coordination with people who may be guided by different cultural and social referents, and with whom intersubjective agreements need to be established (McMillan et al., 2016).

Figure II, developed in Lalueza & Macías-Gómez-Estern (2020) and inspired by the third generation of Activity Theory (Engeström, 2001), accounts for the dialectical and continuously transforming character of identity change processes in a hybrid activity context that we have observed in our SL programmes.

FIGURE II. Conceptual map of the dialectical process of identity change

Source: Compiled by authors, inspired by Engestrôm, 2001.

Through an action-research project conducted at two universities, we have analysed the learning processes of university students enrolled in SL projects, questioning their character as authentic learning. Thus, we have been able to identify the details of a process that, as previous studies have shown (Santos Rego et al., 2022; Asenjo et al., 2021), combines the development of competences with the redefinition of reality in contact with a community group.

Quantitative studies have allowed us to access the perceptions of the learning process of the students who participated in the SL programmes, revealing results consistent with quantitative research conducted to date (Blanco-Cano & García-Martín, 2021). Firstly, we found that SL helped students to understand contents better, with a significant differential with respect to the non-SL group. Secondly, there were also significant differences in self-perceptions about the procedural competences acquired, as well as their usefulness in a potential professional field and in their life in general. Finally, and consistent with the literature (Asenjo et al., 2021), students who participated in the SL projects developed their self-concept and recognised personal changes related to their personal views, sensitivity, tolerance and empathy towards others.

For their part, qualitative studies have allowed us, through the pupils’ field notes, to interpret the processes that favour this learning. Although both studies are oriented towards different goals, both identify as triggers the immersion of students in an uncertain context, which they have to face, and the reflective processes that they generate. We therefore highlight, in line with Kiely’s studies (2005), the relevance of considering our SL experience as a “border crossing” that forces students to move towards a context of activity that is different from their everyday world, oriented towards goals other than those of the university institution, governed by other rules and mediated by different artefacts. This is intensified if it also involves an encounter with people with very different cultural references.

The first qualitative study shows how students develop a new interpretation of reality using the tools they learn on the course, which they use to intervene in it. Conceptual knowledge is not content to be “hoarded” but an instrument for understanding and acting in the world. Nevertheless, what is decisive for us to be able to speak of authentic learning is how this new knowledge acquired in practice leads to initiative and commitment to the activity. The need to understand - in order to act - goes hand in hand with making commitments to people and to the goals of the activity. The concepts are appropriated by the students as psychological tools that enable them to understand the practice, to make decisions and thus to become intervening agents in the context of the practice.

The second qualitative study allowed us to trace the dynamics of otherness that the students had with members of the Roma community, and how they went through some emotional experiences that were generators of internal changes. The “crossing of borders” acts as a triggering factor in this process, where “the other” becomes especially important, both culturally or paradigmatically (the Roma) and in a personalised way (each of the children with whom one enters into a relationship). As Saavedra et al. (2022) show in their study, the students express and analyse their own emotions, personal interactions and awareness of their own role, allowing us to unravel the chain of dissonance, reflection and bonding that leads them to acquire agency through commitment, also showing us the very important role of affective bonds in this process.

The identity changes shown in the field notes, described in terms of personal pathways and learning, can only be understood within the framework of the practical activity taken as the basic unit of analysis. Agency emerges through involvement in the activity, in a scenario that transforms through the intervention of the different participants and generates its own goals. From a cultural-historical perspective (Vygotski, 1978), we interpret the SL projects analysed as activity systems in which otherness plays a special role as a driver of learning and change (Taylor, 2014). In this perspective, the focus shifts from isolated individual learning to the analysis of SL activity as a boundary field in which subjects, motives, cultures, and goals converge from the two preceding systems, the university, and the school, creating a hybrid system with a dual community referent and an equally dual object. Students thus participate simultaneously in a university academic activity scenario and a community professional scenario, each with its own goals, instruments, motives and rules of action. In this sense, our work gives empirical support to McMillan et al. (2016), when they state that this type of hybrid system in which students do not participate to respond exclusively to academic requirements, but also to respond to the demands of the community, will transform them as they become active agents.

The two quantitative studies described here are highly reliable due to the sample sizes, the concordance of the results between them and the coherence with previous studies focusing on the same object. However, the qualitative studies, although they have allowed us to investigate processes that undoubtedly have potential to generate authentic learning processes, are nonetheless case studies and therefore their results cannot legitimately be generalised. The context, made up of the particular type of SL programme shared by both universities, among other elements, cannot be separated from the contents analysed, which allow us to speak of border crossing and authentic learning. This is why we believe that more qualitative studies are needed to examine the relevance of these concepts in different types of SL programmes.

The institutionalisation processes currently underway in Spanish universities require, firstly, a definition of what is meant by university SL, and secondly, mechanisms for evaluating the impact on students (learning and personal change) and on the service (impact on the community). In this framework, we consider that the conceptualisation of SL as authentic learning provided by our work is not just an academic exercise, as it can operate as one of the tools for evaluating the impact of SL required by these institutionalisation processes, a task that we have already begun to advance in García-Romero et al. (2021), but which still has a long trajectory ahead.

Research funded by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, within the State Programe for Research, Development and Innovation Oriented to the Challenges of Society, Call 2014, Modality «Proyectos I+D+I». Ref: EDU2014-55254-R.

Asenjo, J. T., Santaolalla, E., & Urosa, B. (2021). The impact of service learning in the development of student teachers’ socio-educational commitment. Sustainability, 13(20), 11445. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011445

Blanco-Cano, E.; García-Martín, J. (2021). El impacto del aprendizaje-servicio (ApS) en diversas variables psicoeducativas del alumnado universitario: las actitudes cívicas, el pensamiento crítico, las habilidades de trabajo en grupo, la empatía y el autoconcepto. Una revisión sistemática. Revista Complutense de Educación, 32(4), 639–649. https://redined.educacion.gob.es/xmlui/handle/11162/218099

Capella-Peris, C., Gil-Gómez, J., & Chiva-Bartoll, Ò. (2020). Innovative analysis of service-learning effects in physical education: A mixed-methods approach. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 39(1), 102–110.

Clarà, M., & Mauri, T. (2010). El conocimiento práctico: Cuatro conceptualizaciones constructivistas de las relaciones entre conocimiento teórico y práctica educativa. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 33(2), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1174/021037010791114625

Cole, M., & the Distributed Literacy Consortium. (2006). The Fifth Dimension: An after-school program built on diversity. Russell Sage Foundation.

Conway, J. M., Amel, E.L., & Gerwien, D. P. (2009). Teaching and learning in the social context: A meta-analysis of service learning’s effects on academic, personal, social, and citizenship outcomes. Teaching of Psychology, 36(4), 233–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986280903172969

Dewey, J. (1936). General propositions, kinds, and classes. The Journal of Philosophy, 33(25), 673–680. https://doi.org/10.2307/2016747

Duman, N., & Karakas-Ozur, N. (2020). Philosophical Roots of Authentic Learning and Geography Education. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 90, 185–204. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1284522

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive Learning at Work: toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14(1), 136–156.

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

García-Romero, D., Lalueza, J. L., & Blanch Gelabert, S. (2021). Análisis de un proceso de institucionalización del Aprendizaje-Servicio universitario. Athenea Digital: revista de pensamiento e investigación social, 21(3). https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/athenea.2934

García-Romero, D., & Martínez-Lozano, V. (2022). Social Participation and Theoretical Content: Appropriation of Curricular Concepts in Service-Learning. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 26(1). https://openjournals.libs.uga.edu/jheoe/article/view/1504

García-Romero, D., Sáchez-Busqués, S., & Lalueza, J. L. (2018). Exploring the value of service learning: students’ assessments of personal, procedural and content learning. Estudios sobre Educación, 35, 557–577. https://doi.org/10.15581/004.35.557-577

González, F. (2009). La significación de Vygostki para la consideración de lo afectivo en la educación: las bases para la cuestión de la subjetividad. Actualidades investigativas en Educación, 9, 1–24.

Guerrero-Rodríguez, M., González-Romo, A. I., Ornelas-Rodríguez, G., & Valencia-García, M. A. A. (2014). Tareas de aprendizaje auténtico para el desarrollo de competencias en los niveles medio superior y superior. DOCERE, 11, 5–8. https://doi.org/10.33064/2014docere111793

Gutiérrez, K. D., & Vossoughi, S. (2010). Lifting off the ground to return anew: Mediated praxis, transformative learning, and social design experiments. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1-2), 100–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109347877

Jiménez Jiménez, F., Fernández Cabrera, J. M., & Gómez Rijo, A. (2021). Derribando muros: percepción del alumnado universitario en una experiencia de Aprendizaje-Servicio en un contexto de justicia juvenil. Estudios pedagógicos (Valdivia), 47(4), 331–350. https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?pid=S0718-07052021000400331&script=sci_abstract&tlng=en

Kiely, R. (2005). A transformative learning model for service-learning: A longitudinal case study. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 12(1), 5–22. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ848477

Lalueza, J. L., Crespo, I., Maria, C. P., & Luque, J. (2001). Socialización y cambio cultural en una comunidad étnica minoritaria. El nicho evolutivo gitano. Cultura y educación, 13(1), 115-130.

Lalueza, J. L., & Macías-Gómez-Estern, B. (2020). Border crossing. A service-learning approach based on transformative learning and cultural-historical psychology (Cruzando la frontera. Una aproximación al aprendizaje servicio desde el aprendizaje transformativo y la psicología histórico-cultural). Culture and Education, 32(3), 556–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2020.1792755

Lalueza, J. L., Sánchez-Busqués, S., & García-Romero, D. (2020). Following the trail of the 5th dimension: learning from contradictions in a university-community partnership. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 27(2), 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2019.1611859

Macías-Gomez-Estern, B., Arias-Sánchez, S., Marco Macarro, M. J., Cabillas Romero, M. R., & Martínez-Lozano, V. (2019). Does service learning make a difference? comparing students’ valuations in service learning and non-service learning teaching of psychology. Studies in Higher Education, 46(7), 1395–1405. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1675622

Macías-Gómez-Estern, B., & Lalueza, J. L. (2024). Navigating I-positionings in higher education Service Learning as hybrid scenarios: a case study. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2024.100805

Macías-Gómez-Estern, B., Martínez-Lozano, V., & Vásquez, O. A. (2014). “Real Learning” in Service Learning: Lessons from La Clase Mágica in the US and Spain. IJREE–International Journal for Research on Extended Education, 2(2), 13–14.

Manzano-Arrondo, V. (2012). La universidad comprometida. Hegoa.

Marco-Macarro, M., Martínez-Lozano, V., & Macías-Gómez-Estern, B. (2016). El Aprendizaje-Servicio en Educación Superior como escenario de aprendizaje y de construcción identitaria. Papeles de Trabajo sobre Cultura, Educación y Desarrollo Humano, 12(3), 45–51.

Martínez, R. J., & Moreno, R. (2014). ¿Cómo plantear y responder preguntas de manera científica?. Síntesis.

Matusov, E., von Duyke, K., & Kayumova, S. (2016). Mapping concepts of agency in educational contexts. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 50(3), 420–446. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12124-015-9336-0

McMillan, J., Goodman, S., & Schmid, B. (2016). Illuminating “transaction spaces” in higher education: University–community partnerships and brokering as “boundary work”. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 20(3), 8–31. https://openjournals.libs.uga.edu/jheoe/article/view/1291

Naudé, L. (2015). On (un)common ground: Transforming from dissonance to commitment in a service learning class. Journal of College Student Development, 56(1), 84–102. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/566969

Nehari, M., & Bender, H. (1978). Meaningfulness of a Learning Experience: A Measure for Educational Outcomes in Higher Education. Higher Education 7(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00129786

Primavera, K. (2021). Make Learning Purposeful. English in Texas, 51(1), 20–25. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1312159

Redondo Corcobado, P., & Fuentes Gómez-Calcerrada, J. L. (2020). La investigación sobre el Aprendizaje-Servicio en la producción científica española: una revisión sistemática. Revista complutense de educación, 31(1) 69–83.

Saavedra, J. A., Ruiz, L., Alcalá, L., & Saavedra, J. A. (2022). Critical Service-Learning Supports Social Justice and Civic Engagement Orientations in College Students. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 28(1). h

Santos Rego, M. A., Sáez-Gambín, D., González-Geraldo, J. L., & García-Romero, D. (2022). Transversal Competences and Employability of University Students: Converging towards Service-Learning. Education Sciences, 12(4), 265. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7102/12/4/265

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. Jossey-Bass.

Shek, D. T.L., Ma, C. M. S., & Yang, Z. (2020). Transformation and development of university students through service-learning: A corporate-community-university partnership initiative in Hong Kong (Project WeCan). Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(5), 1375–1393. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11482-019-09738-9

Sotelino, A., Arbués-Radigales, E., García-Docampo, L., & González-Geraldo, J. L. (2021). Service-learning in Europe. Dimensions and understanding from academic publication. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 6, p. 604825). https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.604825

Taylor, A. (2014). Community service-learning and cultural-historical activity theory. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 44(1), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v44i1.183605

Taylor, A. (2017). Service-learning programs and the knowledge economy: Exploring the tensions. Vocations and Learning, 10(3), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-016-9170-7

Underwood, C., Mahmood, M. W., & Vásquez, O. (Eds.). (2021). A cultural historical approach to social displacement and university-community Engagement: Emerging research and opportunities. IGI Global.

Vásquez, O. (2003). La Clase Mágica: Imagining Optimal Possibilities in a Bilingual Community of Learners. Laurence Erlbaum.

Velázquez-Rivera, L.M., Clark-Mora, L., & Quiñones-Pérez, I. R. (2020). La problematización: Herramienta para facilitar el aprendizaje auténtico de las ciencias en el nivel elemental. International Journal of New Education, 6, 63–81. https://doi.org/10.24310/IJNE3.2.2020.10267

Vygotski, L. S. (1978). El desarrollo de los procesos psicológicos superiores. Crítica.

Wenger, E. (2001). Comunidades de práctica: Aprendizaje, significado e identidad. Paidós.

Contact address: David García-Romero. Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Facultade de Ciencias da Educación, Departamento de Pedagoxía e Didáctica, Rúa Prof. Vicente Fráiz Andón, s/n, 15782, Santiago de Compostela, España. E-mail: d.garcia.romero@usc.es

_______________________________

1 Fictitious names have been used to ensure the anonymity of the participants.