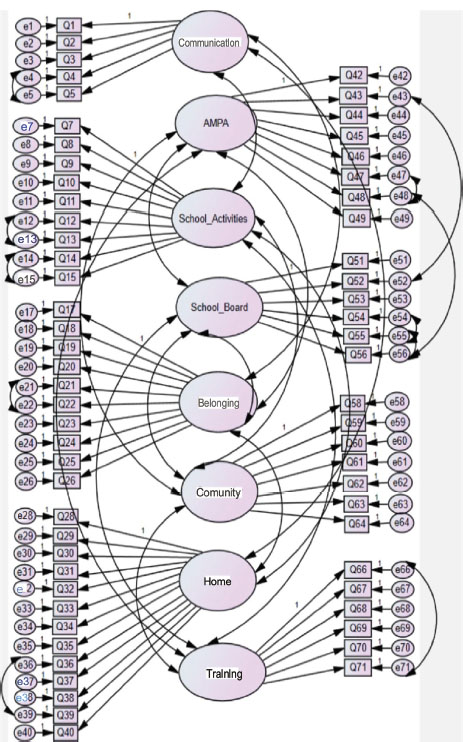

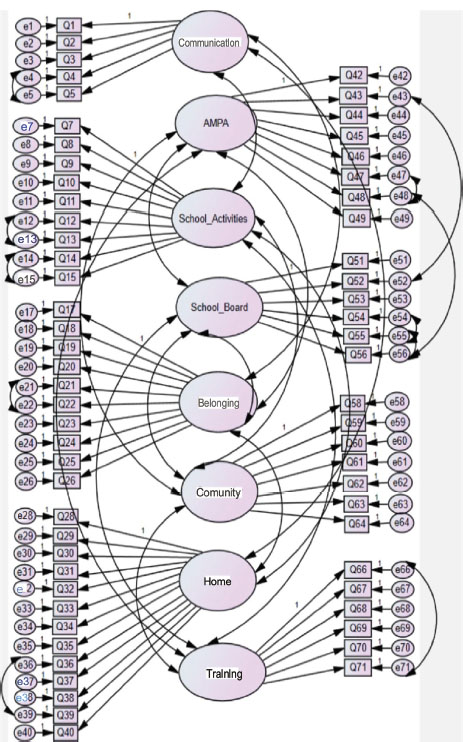

FIGURE I. Questionnaire Family Involvement in School (QFIS) Structural Equation Model

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2023-402-593

María de los Ángeles Hernández-Prados

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3617-215X

Universidad de Murcia

María Ángeles Gomariz Vicente

https://orcid.org/000-0002-8308-0848

Universidad de Murcia

María Paz García Sanz

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0367-7407

Universidad de Murcia

Joaquín Parra Martínez

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6818-8909

Universidad de Murcia

Abstract

This research presents an original instrument (Questionnaire Family Involvement in School, QFIS) to evaluate something as important as family involvement in school life. The questionnaire has been validated to measure the dimensions of such involvement: Communication with families, Participation in school activities, Sense of belonging, Home involvement, Activities in the Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) and School Council, Community involvement, and Family training. The participants were 3612 families of students in Early Childhood Education, Primary Education, and Secondary Education in a multicultural context. The instrument was collaboratively constructed by the authors and contributions from school management teams and AMPA. After validating the content of the instrument and the corresponding exploratory factor analysis (using the principal component method), the confirmatory factor analysis (by modelling structural equations) empirically demonstrated the fit of the initial theoretical model. The calculated reliability indices were satisfactory, indicating that the resulting instrument is valid and reliable for the overall measurement of family involvement in school. The possibilities for transfer related to detecting needs for educational administrations, centre managers, and future work that allows for digital evaluation processes of involvement are evident.

Keywords: family involvement, school, structural equation model, construct validity, factor analysis.

Resumen

Esta investigación ofrece un instrumento original (Questionnaire Family Involvement in School, QFIS) para evaluar algo tan importante como es la participación de las familias en la vida de los centros escolares. Se ha validado el cuestionario para medir las dimensiones de dicha participación: Comunicación con las familias, Participación en actividades del centro, Sentimiento de pertenencia, Implicación en el hogar, Actividades en las AMPA y en el Consejo Escolar, Participación comunitaria y Formación de familias. Los participantes fueron 3612 familias de alumnado de Educación Infantil, Educación Primaria y Educación Secundaria en un contexto multicultural. El instrumento fue construido colaborativamente por los autores y las aportaciones de equipos directivos de centros y AMPA. Al validar el contenido del instrumento y el correspondiente análisis factorial exploratorio (utilizando el método de componentes principales), el análisis factorial confirmatorio (mediante modelado de ecuaciones estructurales) demostró empíricamente el ajuste del modelo teórico inicial. Los índices de confiabilidad calculados fueron satisfactorios, lo que nos informa que el instrumento resultante es válido y confiable para la medición global de la participación familiar en la escuela. Son evidentes las posibilidades de transferencia referidas a la detección de necesidades para las administraciones educativas, los gestores de centros y futuros trabajos que permitan procesos de digitalización de evaluación de la participación.

Palabras clave: participación familiar, escuela, modelo de ecuaciones estructurales, validez de constructo, análisis factorial.

Family involvement in schools has been seen, by researchers and educational agents, as a relevant but complex process (Baker et al., 2016; Epstein et al., 2019; Kurtulmus, 2016; Wilder, 2014). Its relevance lies in a positive impact on inclusion, academic performance improvement, school climate, prevention of violent behaviour, and school dropout, among others (Jeynes, 2023; Merchán-Ríos et al., 2023; Tan et al., 2020; Wilder, 2014). Its complexity lies, on the one hand, in the interpretation made of the concept of participation, understood mostly as a face-to-face act, and not so much from an educational commitment to the school (Baker et al., 2016), reducing families to a consumer-client role, using the terminology of Vogels, which is unenterprising and un-innovative (Cárcamo & Jarpa-Arriagada, 2021). On the other hand, complexity lies in the reference to two contexts with different educational ways of proceeding, complementary and evoked to understanding (Hernández-Prados, 2022), and in the diversity of dimensions and variables that affect the family-school relationship, and its multilevel nature (Cárcamo & Jarpa-Arriagada, 2021; Epstein et al., 2019; Fernández-Alonso et al., 2017). Additionally, family involvement is subject to the geographical and cultural peculiarities of the context (Fernández-Vega & Cárcamo, 2021; Garbacz et al., 2019).

Specific research on family involvement has been characterised, firstly, by analysing the levels of such involvement from the perception of teachers, management teams, the families themselves and, on rare occasions, students (Torrego, 2019). And secondly, by employing different methodologies, information collection instruments, population sectors and statistical analyses, which make comparative analyses difficult (McNeal, 2012). According to Boonk et al. (2018), this distinction is due to research being conducted without a widely accepted theoretical framework. Hence the importance of confirmatory analyses that help us provide consistency to theoretical models.

Recent bibliographic studies conclude that research on family involvement has mainly focused on the modalities, variables, effects, and obstacles of collaboration, as well as on the immigrant group (Egido, 2020). Participation can be divided into both in school and at home, direct or indirect, individual or collective (Castro et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2020). Information can be gathered on the nature of parental involvement (consumer, client, participant, and partner), the level of parental involvement (informative, consultative, collaborative, decision-making, and efficacy control), and the place of participation (inside or outside the school), according to the model of Cárcamo and Jarpa-Arriagada (2021). Other aspects, such as promoting participation opportunities, improving communication, welcoming families, sharing time, and favouring the transition from involvement to commitment, are also important for family involvement (Baker et al., 2016). Without detracting from the relevance of any of them, we focus on the theoretical delimitation of each of the modalities or avenues for participation, starting from the general to the particular. In this regard, the Anglo-Saxon model of Epstein (Epstein et al., 2019), internationally recognised, remains in force, and contemplates six forms of family involvement: parenting, communication, volunteering, home learning, decision-making, and community collaboration. The North American model of Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler (Walker et al., 2005) consists of five levels of involvement (parental role beliefs, parental self-efficacy to help, feeling invited to participate by children and teachers, and participation in school activities) and recognises the importance of feeling welcomed by teachers in the decision to participate. For its part, León and Fernández (2017) present a model of nine aspects that are grouped into four modalities of family involvement: relationship (communication and family-teacher-school relationship); pedagogical support (orientation and promotion); participation (modes of participation, personal interest, knowledge); and training (behavioural and academic aspects). These studies reveal that communication, participation in school activities, family involvement, and training are common elements. The Dual Navigation Approach (DNA) model of Jeynes (2023) highlights communication, associationism, homework supervision, participation in classroom and school activities, and community resource mobilisation as aspects of school involvement, differentiating it from involvement at home.

More specifically, communication has been recognised as one of the most effective forms of student progress (Clark et al., 2019); motivating participation in the rest of the modalities, especially with school activities, home involvement, and a sense of belonging (Garreta & Llevot, 2022; Gomariz et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2020); and effective for receiving guidelines to help students at home; in fact, families demand more timely, proactive, and preventive communication (Baker et al., 2016). Communication is mainly developed through face-to-face interactions (Conus & Fahrni, 2019), often associated with attending informational meetings and tutorials to address problems (López-Castro & Pantoja, 2016; Tran, 2014), although digital communication is on the rise, despite the scepticism and distrust of teachers (Novianti & Garzia, 2020; Papakonstantinou, 2023). It includes aspects such as individual tutoring, collective meetings with families, the school agenda, informative notes, as well as any other form of communication (Consejo Escolar del Estado, 2014; Dettmers et al., 2019; Garbacz et al., 2019), although they can be specified as López-Castro and Pantoja (2016) do when focusing on family involvement in tutoring, knowledge of the functions and degree of satisfaction with the tutor and advisor, dedication and commitment of the tutor and use of the digitised communication in tutorial activities.

On the other hand, most models distinguish between Participation in school activities, focused on fostering collaborative actions within the school, and Involvement from home, which promotes support for children in homework and cognitive development (Gomariz et al., 2020; Hernández-Prados, 2022; Jeynes, 2023). The first of these encompasses attendance at meetings with teachers, help with classroom activities and participation in the running of the school as actions that make up participation in the school (Fernández-Alonso et al., 2017) as well as classroom activities, sports, coexistence, cultural activities, festivals, extracurricular outings, school services such as the library or canteen, school committees, fundraising and evaluative activities (Gomariz et al., 2020). The frequency or mode of participation (attendance, collaboration or involvement in management and decision-making) can be taken into account, as has been done on other occasions (Consejo Escolar, 2014).

By Implication at home, we understand those educational actions carried out by parents at home to promote their children's learning and allow for the general social capital of the child, encouraging family communication about school life, reading at home, participating in educational and cultural activities, instilling academic norms and expectations, supporting their learning at home and homework, parenting style, family norms, etc. (Boonk et al., 2018; Jeynes, 2023). The term does not imply presence in school, but rather a commitment to school education (Baker et al., 2016), it promotes student achievement and well-being (Dettmers et al., 2019), and it is related to the sense of belonging and centre activities.

The training of families is included as one of the centre's activities (Consejo Escolar, 2014) and we consider it to be a specific form of participation, in line with trends that emphasise the importance of family information and training policies, betting on a training model in which families and teachers commit to learning together (Fernández-Alonso et al., 2017; Tran, 2014). Nonetheless, both dimensions, Training and Centre Activities, are deeply related (León & Fernández, 2017).

In Spain, there are two bodies representing families in schools: the Associations of Mothers and Fathers of Students (AMPA), which is an appropriate form of organisation that allows for social interaction between educational organisations and the immediate surroundings of schools (Calik et al., 2019; Merchán-Ríos et al, 2023) and promotes community participation, and School Councils. They are consultative bodies, subject to recent debate, with little prominence in educational research, which require greater teacher qualification to optimise their potential in terms of family involvement (García-Sanz et al., 2020), as currently presents low levels of involvement, especially from Roma and immigrant families (Garreta, 2016; Merchán-Ríos et al, 2023). According to Garreta and Llevot (2022), the AMPA is considered a support channel, since it consists of professionals who act as translators or mediators. New trends in research on the subject tend to identify various components of parental involvement, such as cultural, emotional, and psychological aspects, among others (Jeynes, 2023; Merchán-Ríos et al., 2023). In this sense, special educational needs, parental trust in educational support, academic expectations, sense of belonging, parental satisfaction and well-being, are aspects to consider (Tan et al., 2020), as well as the cultural barriers faced by certain immigrant or Roma communities (Garreta & Llevot, 2022; Merchán-Ríos et al., 2023). New models also emerge, such as the one proposed by Garbacz et al. (2019), which contemplates: communication between home and school, home expectations and monitoring, educational support, school and community participation, and school attendance. Subsequent studies have evolved by introducing new elements such as the sense of belonging, family training, and the facilitating role of the teacher, among others (Gomariz et al., 2022; Hernández-Prados et al., 2019; Hernández-Prados et al., 2015). From a more social approach to education, community participation is considered. It involves ending the barriers around the school to collaborate with the community, through actions that promote cooperation between schools, families, organisations, community groups, businesses, and agencies (Gomariz et al., 2020). There are community participation initiatives through service-learning, which emphasise the commitment to solidarity in students and facilitate responsible citizenship (Rabadán et al., 2022), but they generally do not integrate family participation. Gahwaji (2019) includes, among others, national and religious events, celebrations, programs of local organisations, comprehensive family service, guides to community institutions, partnerships with libraries, parks and museums, and family association in collaboration with the community. From another approach, more focused on the participation for citizenship, solidarity-based, fundraising, ecological, religious, volunteering, neighbourhood activities could be included, among others, providing its own identity and differentiated from the rest of the dimensions in terms of content.

Finally, participation is closely linked to emotion, specifically the feeling of belonging of families to the educational centre. This feeling identifies with feeling welcomed and recognised by the educational community, so that one perceives oneself as a member of the centre (Hernández-Prados et al., 2015). This is a determining factor in family participation and in improving academic performance (Castro et al., 2015). With the review of previous studies (Reparaz et al., 2018; Uslu & Gizir, 2017), we have incorporated: identification with the educational project of the centre, trust in the teaching staff, defence of the centre’s teams, feeling integrated and liberated from negative connotations towards the school, which translates into greater satisfaction and involvement with the activities organised by the centre, to the point of recommending it to other families. Feeling invited by teachers and maintaining positive communication is essential to feeling recognised, embraced and welcomed to school, increasing family participation and feeding back into the processes (Anderson & Minke, 2007). The study by Uslu and Gizir (2017) revealed that interpersonal relationships, involvement at home, and family participation in school are significant predictors of the sense of belonging.

As a result of the review conducted, a Comprehensive Model of Family Participation in Educational Centres (IMFIS) was created, which incorporates seven modalities of family participation: 1. Communication, 2. Centre activities, 3. Sense of belonging, 4. Involvement at home, 5. Parent-teacher association and school council, 6. Community participation, and 7. Family training. This model integrates traditional and emerging modalities, overcoming partial and conservative views. In addition to promoting a broad understanding of family participation, it allows for relationships to be established between each of them, since, although it is shown linearly, following the order used in the questionnaire, there are interconnections that each dimension maintains with the rest, weaving a network of interdependencies that better reflects the complexity of family participation.

We pose the following research problem: how to validly and reliably evaluate family participation in their children's educational centre? Likewise, the general objective of the study was to construct a comprehensive questionnaire based on the theoretical model presented on family participation, to obtain knowledge about the dimensions that make up family participation in schools. The initial operational objectives were:

A descriptive, non-experimental, cross-sectional, and confirmatory quantitative survey design was used in this research.

Out of an estimated population of 5022 families of students from 14 educational centres in Southeast Spain, where Infant, Primary, and Secondary Education is taught, all of them were invited to participate. Through a volunteer sampling, 3639 families accepted the invitation (19.8% from Infant Education, 59.1% from Primary Education, and 20.3% from Secondary Education). However, after refining the data, a real sample of 3612 parents was obtained, achieving a confidence level of 97% and a sampling error of less than 1%.

We started with an initial questionnaire with 19 situational questions and 88 items (with a 5-point scale, except for one dichotomous) on family participation grouped into 7 dimensions according to the IMFIS, which we named Questionnaire Family Involvement in School (QFIS). After a content validity check performed by 5 university professors (experts in the subject and research methodology), the 14 participating centres’ management teams and the respective AMPA boards, the instrument retained the 19 questions about the informants' parents' situation, but the family participation items were reduced to 64, maintaining the initial 7 dimensions. These items are presented in Annex 1.

The content validity of the questionnaire was carried out through email. Before applying the validated instruments to the informant families, they were translated into Arabic and English as necessary, since most non-Spanish origin families (except for Latin Americans) did not understand Spanish. The questionnaires were applied in a normal sanitary situation (non-pandemic), with the educational centres responsible for distributing them to families in paper format and collecting them once completed. These questionnaires were accompanied by a brief letter ensuring the confidentiality of the data and informed consent.

To respond to the first operational objective of the research, an exploratory factor analysis was carried out using the principal component extraction method and the Varimax rotation method through the statistical package SPSS, version 24. Regarding the second objective, a confirmatory factor analysis was carried out using the structural equation modelling approach through the program AMOS, version 21. Finally, to respond to the third objective of the study, the reliability of QFIS was obtained through the calculation of Cronbach's Alpha coefficient and McDonald's Omega using the SPSS program. In all cases, a statistical significance level of α=.01 was considered.

Before proceeding with the exploratory factor analysis, in order to avoid multicollinearity problems among the QFIS items, the Spearman correlation coefficient was calculated between them. In no case did bivariate correlations exceed .85, thus, according to Kline (2005), no item had to be removed from the questionnaire validated by experts.

After checking the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin sample adequacy measure (.955) and the statistical significance of the Barlett sphericity test (.000), which coincided with the dimensions of the theoretical model (IMFIS), 7 components were established, with an explained variance of 53.96%. In this first exploratory factor analysis, all the questionnaire items were included, except the last one of each dimension. These items were subjected to a second factor analysis because their content consists of the opposite process to what is fundamentally intended to be evaluated with the QFIS.

The first factor integrates 12 items, all belonging to the questionnaire dimension called Implication in the AMPA and in the School Council. The second factor is formed by 10 items that constitute the dimension Sense of belonging. The third factor contains the 13 items of the Involvement at Home dimension. The fourth factor includes all the items of the Participation in School Activities dimension (9), plus one belonging to the Communication with the School dimension (Q4: "I talk to the tutor in casual contacts at the educational centre"). It is an item with a low factor load for the factor it saturates (.382), with a very similar load to that obtained in the factor it should have saturated according to the IMFIS (.365). The fifth factor is formed by the 7 items of the Community Participation dimension. The sixth factor integrates the 6 items of the Training dimension. The seventh and last factor includes 4 of the 5 items from the Communication with the School dimension, plus 2 items from the Implication in the AMPA and in the School Council of the centre (Q48: "I am, have been, or would be willing to be a member of the AMPA Board of the centre; Q56: "I am, have been, or would be willing to run as a representative of families in the School Council of the centre"). It can be understood that, to take an active part of the AMPA or the School Council of the centre, broad communication with the educational institution is necessary. In addition, the factorial loads regarding the saturations of the fifth factor are found in the first of them (.389 and .361, respectively), corresponding to the Implication in the AMPA and in the School Council of the centre dimension.

From this first exploratory factor analysis, it can be stated that the QFIS has hardly suffered any variation regarding the assignment of items to each dimension, in relation to the content validation carried out by the evaluators and the IMFIS, although the Communication with the educational centre dimension has been the one that has been most affected. Thus, the denomination of the 7 factors results as follows:

Regarding the second operational objective of the research, the Implication in the AMPA and in the School Council of the centre dimension was divided into two for the calculation of confirmatory factor analysis. Likewise, missing values were eliminated, and although the methodological literature on these values seems to disagree (Aguinis et al., 2013), a decision was made to disregard them, considering as such those cases in which the standardized observable variable scores exceeded the |3| score (Verdugo et al., 2008). In Figure I, according to the IMFIS, the correlation between the latent variables and the observable variables, their specific measurement error, as well as the covariance between the latent variables and also between the detected measurement errors, are graphically represented.

FIGURE I. Questionnaire Family Involvement in School (QFIS) Structural Equation Model

The model was computed using maximum likelihood method. As it is impractical to rely on multivariate normality assumptions, univariate normality was assessed by studying the skewness and kurtosis of each observed variable. For interpretation, the recommendations of Curran et al. (1996) were followed, who established limits for univariate normal behaviour at values up to |2| for skewness and up to |7| for kurtosis. This criterion was met for all observed variables.

All pairs between observed and latent variables are significant, with standardized regression coefficients reaching or exceeding the value of .3 established by Cohen (1988) as the typical size of effect. Similarly, the relationships between latent variable covariance coefficients and measurement error coefficients were all significant. These correlation coefficients reach or exceed, in 88.46% of cases, the value of .3 determined by Cohen (1988).

To assess model fit, since it is recommended to use several indicators (Hu & Bentler, 1998), three indicators of different nature were used (Hair et al., 2008): normalised chi-squared or chi-squared to degrees of freedom ratio (CMIN/DF), included in parsimony goodness of fit measures; comparative fit index (CFI), integrated in incremental fit measures; and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), framed within absolute goodness of fit measures. Table I shows the values obtained for these indices.

Table I. The goodness-of-fit indices of the IMFIS

Index |

Value |

CMIN/DF |

3.49 |

CFI |

.90 |

RMSEA |

.05 |

Regarding the normalised chi-square, the values established by the literature range between 1 and 5 (Hair et al., 2008; Lévy & Varela, 2003; Marsh & Hocevar, 1985; Wheaton et al., 1977). The comparative fit index (CFI) should reach at least .9 (Cupani, 2012; Lévy & Varela, 2003; Marsh & Hocevar, 1985; McDonald & Marsh, 1990). The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) can be found in values lower than .08 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hair et al., 2008), lower than .06 (Hu & Bentler, 1998), or scores below .05 (Lévy & Varela, 2003).

In light of the results, it can be affirmed that the IMFIS presents reasonable fit indices between the theoretical structures and the empirical data obtained, which allows us to use the questionnaire rigorously for the intended purpose.

Regarding the third objective of the study, Table 2 shows acceptable reliability indices for the questionnaire, both for the Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α) and the McDonald's omega (Ω), globally and by dimensions. All of this is in line with the categorisation established by DeVellis (2003), who determines that reliability of a measuring instrument can be considered satisfactory with values equal to or greater than .7.

TABLE II. Overall reliability of the questionnaire by dimensions.

Dimensions |

α Cronbach |

Ω McDonald |

Global |

.958 |

.981 |

Communication with the centre |

.684 |

.661 |

Participation in centre activities |

.848 |

.875 |

Sense of belonging |

.946 |

.931 |

Home involvement |

.875 |

.891 |

Participation in the AMPA and School Council |

.934 |

.926 |

Community participation |

.861 |

.880 |

Training |

.825 |

.792 |

The Questionnaire Family Involvement in School (QFIS) shows sufficient adjustment, although there are other instruments that have measured family involvement in school (Epstein, 2019; Garbacz et al., 2019; León & Fernández, 2017; Walker et al., 2005), its subscales allow measuring several aspects with differentiated internal consistency, integrating new dimensions that are not contemplated in other instruments or only appear as items, without considering subscales. The questionnaire presents content and construct validity with fairly explained variance. Adequate validity and reliability were observed in all dimensions, with special relevance regarding Community Participation, fully saturating the items and without considering covariance between the measurement errors of the items.

The complexity of the relationships between the dimensions of participation is consistent with what is presented in the theoretical model. More specifically, in the Communication dimension, it is observed that the item referring to casual contacts with the tutor (Q4) has saturated in the centre activities dimension when several authors consider it an informal mode of communication (Epstein, 2019), essential when parents work (Snell et al., 2020) or in immigrant families (Garreta & Llevot, 2022), decreasing such contacts as the school year progresses (Conus & Fahrni, 2019). Conversely, two items belonging to other dimensions saturate. Specifically, Q48 and Q56, referring to the willingness to belong to the AMPA board of directors and to represent families on the School Council, probably because this attitude arises from maintaining effective communication with teachers and school leaders. This type of participation has benefits for both students and the relationships between parents and teachers, increasing trust and communication (Murray et al., 2019).

Covariance has been identified between the measurement errors of two variables referring to casual contacts with the tutor (Q4) and communication with other teachers (Q5). Regarding this, we emphasise that although contacts with tutors (Kurtulmus, 2016) acting as mediators of communication between the family and non-tutor teachers, communication with the rest of the teachers should be encouraged, especially in secondary school, where the tutor only teaches one subject. The teaching functions marked by the regulations support the duty of providing "periodic information to families on the learning process of their sons and daughters, as well as guidance for their cooperation in it" (LOMLOE, Art. 91).

Although the AMPA and School Council dimensions present internal consistency independently, in the theoretical model, they constitute a single dimension. They have presented the largest volume of covariances in measurement errors, being recorded in items referring to the AMPA (Q47-Q48), the School Council (Q54-Q55-Q56), and both (Q48-Q56 and Q43-Q52). In the first covariance, we agree with Garreta (2016) that being or being willing to be a member of the AMPA Board of Directors (Q48) necessarily implies participating in the activities organised by the AMPA (Q47). Thus, the decision-making and management processes of the activities are carried out by the association's board, but all families can participate in the organised activities (Calik et al., 2019). In addition, the success of the organised activities depends on both the leadership style and the participation of families (Ndubi & Mugambi, 2019). In the measurement errors recorded in the items referring to the School Council, we can verify that the formulation between being informed of the elections to the School Council (Q54), participating in them (Q55), and presenting oneself as a representative (Q56) is similar, but the levels of participation and the responsibility they entail are different (Consejo Escolar, 2014).

Finally, the theoretical model acknowledges the interactions between the AMPA (Association of Parents of Students) and the School Council, with the latter being the great unknown (Gomariz et al., 2020). Sometimes, families play both roles: being part of the AMPA Board of Directors (Q48) and representing families on the School Council (Q56), leading to oversaturation (García-Sanz et al., 2020). For this same reason, errors related to knowing the members of the AMPA Board of Directors (Q43) and the representatives of the School Council (Q56) arise.

The dimension related to family participation in activities organised by the school is consistent, although families take advantage of these meetings to communicate informally with the tutor. The diversity of activities implies formulating items referring to categories and exemplifying the most common situations in parentheses. These are complex items (Medina, 2015), but necessary to avoid further expanding the questionnaire and exhausting the respondents. The presence of measurement errors leads us to rethink some of the items (Q12-Q13, Q14-Q15): work committees are collaboration spaces related to the communal school philosophy (Payà & Tormo, 2016), and although they have been linked to coexistence and centre improvement (Q13), they are not limited to participation in plan development but also in services (Q12). Although Stacer and Perrucci (2013) argue that both items could constitute a single one, our proposal is to continue considering them as different. Likewise, family participation in fundraising (Q14) and centre evaluation processes (Q15) present covariance between the measurement errors of both items. There is evidence to justify the presence of both items. Some family participation taxonomies contemplate that they act as support agents to improve resource provision (Youn et al., 2012), although there are significant differences based on the social capital of families (Msila, 2012), and many impoverished communities distance themselves from school if they only care about receiving more than giving (Jeynes, 2023). Furthermore, we witness the construction of an evaluative culture based on the participation of the school community that promotes the improvement of educational quality (Janzen et al., 2017).

The dimension Involvement at home shows high consistency and reliability. It requires attention to the similarity between extracurricular or complementary activities (Q36) and cultural activities (Q37) that can lead to confusion, especially in immigrant families unfamiliar with Spanish school activities (Garreta, 2016). The difference between them lies in that the former present an academic, individual nuance, and external to the home, while the latter are typical of shared family leisure, essential in family education (Álvarez-Muñoz et al., 2023). We agree with Fernández-Alonso et al. (2017) and Castro et al. (2015) in recognising that involvement at home covers support and cultural opportunities (Q33), communication with children about school issues (Q25), and accompanying them in schoolwork (Q31).

The dimension Sense of belonging presents a level of total coincidence with the theoretical model and the highest reliability of all dimensions, with the exception of the measurement error covariance related to two items (Q21-Q22). Feeling attracted to collaborative activities or experiences with families refers to the potential of the sense of belonging as a driver for participation (Castro et al., 2015), while participating in the educational centre makes one feel part of it, emphasising how the sense of belonging to a community is generated (Dove et al., 2018; Hernández-Prados et al., 2015; Uslu & Gizir, 2017).

Finally, having information about the educational activities for families organised by the school (Q66) is the lowest level of participation in the Training dimension, since it does not imply a commitment to attend. Commitment is essential to participate, just as teacher commitment is vital to promote participation (Dove et al., 2018; Siciliano, 2016). However, when we ask if the training offered contributes to improving family-school relationships (Q71), it is a different aspect, focused on the content of the training activity. Wilder (2014) indicates that training sessions for parents in communication with the school and involvement in home reading had positive results in family-school relationships and student performance. Given the above, there is evidence to maintain both items despite the covariance found.

This study offers a comprehensive model for evaluating family participation in schools and a reliable and valid multidimensional measurement tool that fits well with the IMFIS. QFIS provides relevant information for making decisions in action with families in Early Childhood, Primary, or Secondary Education centres, making it useful for different education professionals (educational administration, centre management teams, and family associations). As a limitation, although the proposed model presents an acceptable fit, it has only confirmed that it is one of the possible models (Cupani, 2012). Regarding the relationship between the obtained measurement errors, Hermida (2015) conducted 985 studies, in which 315 articles were identified that allowed correlating the measurement errors of observable variables. For this author, this is acceptable due to theoretically justifiable reasons, with the complexity of the model being a potential reason for the correlation of measurement errors. Landis et al. (2009) argue that estimating measurement errors in the structural equation model is only appropriate when these correlations are inevitable, including when observable variables share components. Both cases affect this study, with the wording of the affected items being very similar, but at the same time, all of them are necessary to conform to the specified theoretical model.

This study becomes the empirical reference framework for managing and supporting, among other transfer possibilities, the development of digital platforms for joint co-training of families and teaching staff (Ref. PID2020-113505RB-I00). We share that family empowerment in leadership roles contributes to mobilising their networks, connections, and increasing participation (Dove et al., 2018), which in turn favours the transition from a spectator family to a partner (Hernández-Prados, 2022). QFIS can promote an empathic process with teachers and the desire to share, an essential competence to establish collaborative, reciprocal family-school relationships (Peck et al., 2015). Similarly, trust between these agents results in a more active role for families in the classroom and better support and guidance from teachers towards family education (Tran, 2014).

This work has been carried out within the framework of the ref. EDU2016-77035-R and ref. PID2020-113505RB-I00 projects, funded by MINECO and MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 (Ministry of Science and Innovation/State Research Agency), respectively.

Aguinis, H., Gottfredson, R. K., & Joo, H. (2013). Best-practice recommendations for defining, identifying, and handling outliers. Organizational Research Methods, 16(2), 270–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112470848

Álvarez-Muñoz, J.S., Hernández-Prados, M.A., & Belmonte, M.L. (2023). Percepción de las familias sobre los obstáculos y dificultades del ocio familiar durante el confinamiento. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 42, 167–180. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2023.42.11

Anderson, K. J., & Minke, K. M. (2007). Parent Involvement in Education: Toward an Understanding of Parents’ Decision Making. The Journal of Educational Research, 100(5), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.100.5.311-323

Baker, T. L., Wise, J., Kelley, G., & Skiba, R. J. (2016). Identifying barriers: Creating solutions to improve family engagement. School Community Journal, 26(2), 161–184. http://www.schoolcommunitynetwork.org/SCJ.aspx

Boonk, L., Gijselaers, H. J. M., Ritzen, H., & Brand-Gruwel, S. (2018). A review of the relationship between parental involvement indicators and academic achievement. Educational Research Review, 24, 10–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.02.001

Browne, M.W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K.A. Bollen, & J.S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage.

Calik, B., Kilic, K., & Akar, H. (2019). Evaluation of the Current School-Parent Association Policy in Two Public Primary Schools. Elementary Education Online, 18(1), 1–19. doi: http://ilkogretim-online.org.tr/index.php/io/article/view/2170

Cárcamo, H., & Jarpa-Arriagada, C. (2021). Debilidad en la relación familia-escuela, evidencias desde la mirada de futuros docentes. Perspectiva Educacional, 60(1), 58–80. https://doi.org/10.4151/07189729-vol.60-iss.1-art.1172

Castro, M., Expósito-Casas, E., López-Martín, E., Lizasoain, L., Navarro-Asencio, E., & Gaviria, J. L. (2015). Parental involvement on student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational research review, 14, 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.01.002

Clark, K., Epstein, J.L., & Sanders, M.G. (2019). Measure of school, family, and community Partnerships. In J.L. Epstein (Coord.), School, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for action (pp. 342–347). Corwin Press.

Cohen, J. (1988) (2ª. ed.). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Academic Press.

Consejo Escolar del Estado (2014). La participación de las familias en la educación escolar. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. http://ntic.educacion.es/cee/estudioparticipacion/

Conus, X., & Fahrni, L. (2019). Routine communication between teachers and parents from minority groups: an endless misunderstanding? Educational Review, 71(2), 234–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2017.1387098

Cupani, M. (2012). Análisis de ecuaciones estructurales: conceptos, etapas de desarrollo y un ejemplo de aplicación. Revista Tesis, 1, 186–199.

Curran, P. J., West, S.G., & Finch, J.F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods 1, 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16

Dettmers, S., Yotyodying, S., & Jonkmann, K. (2019). Antecedents and outcomes of parental homework involvement: How do family-school partnerships affect parental homework involvement and student outcomes? Frontiers in psychology, 10, 1048. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01048

DeVellis, R.F. (2003) (2.ª ed.). Scale development: Theory and applications. Sage.

Dove, M. K., Zorotovich, J., & Gregg, K. (2018). School Community Connectedness and Family Participation at School. World Journal of Education, 8(1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v8n1p49

Egido, I. (2020). La colaboración familia-escuela: revisión de una década de literatura empírica en España (2010-2019). Bordón: Revista de pedagogía, 72(3), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.13042/Bordon.2020.79394

Epstein, J.L. (Coord.) (2019). School, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for action. Corwin Press.

Epstein, J. L., Sanders, M. G., Sheldon, S. B., Simon, B. S., Salinas, K. C., Jansorn, N. R., Van Voorhis, F. L., Martin, C. S., Thomas, B. G., Greenfeld, M. D., Hutchins, D. J., & Williams, K. J. (2019). School, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for action. Corwin Press.

Fernández-Alonso, R., Álvarez-Díaz, M., Woitschach, P., Suárez-Álvarez, J., & Cuesta, M. (2017). Parental involvement and academic performance: Less control and more communication. Psicothema, 29(4), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2017.181

Fernández-Vega, J. P., & Cárcamo, H. (2021). Relación familia-escuela: significados de profesores rurales sobre la participación de las familias. Propósitos y Representaciones, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9n2.636

Gahwaji, N. M. (2019). The Implementation Of The Epstein’s Model As A Partnership Framework At Saudi Kindergartens. Journal of College Teaching & Learning (TLC), 16(2), 11–20.

Garbacz, S. A., Hall, G. J., Young, K., Lee, Y., Youngblom, R. K., & Houlihan, D. D. (2019). Validation Study of the Family Involvement Questionnaire–Elementary Version With Families in Belize. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 46(3), 238–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534508419862857

García-Sanz, M. P., Hernández-Prados, M. Á., Galián, B., & Belmonte, M. L. (2020). Docentes, familias y órganos de representación escolar. Estudios sobre Educación, 38, 125–144. https://doi.org/10.15581/004.38.125-144

Garreta, J. (2016). Las asociaciones de madres y padres en los centros escolares de Cataluña: puntos fuertes y débiles. Revista electrónica interuniversitaria de formación del profesorado, 19(1), 47–59.

Garreta, J., & Llevot, N. (2022). Escuela y familias de origen extranjero. Canales y barreras a la comunicación en la educación primaria. Educación XX1, 25(2), 315–335. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.31840

Gomariz, M. Á., Hernández-Prados, M. Á., Parra, J., García-Sanz, M. P., Martínez-Segura, M. J., & Galián, B. (2020). Familias y Profesorado Compartimos Educación. Guía para educar en colaboración. Editum. https://doi.org/10.6018/editum.2872

Gomariz, M.Á., Parra J., García-Sanz, M.P., & Hernández-Prados, M.Á. (2022). Teaching Facilitation of Family Participation in Educational Institutions. Front. Psychol. 12:748710. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.748710

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (2008) (5.ª ed.). Análisis multivariante. Prentice Hall.

Hermida, R. (2015). The problem of allowing correlated errors in structural equation modeling: concerns and considerations. CMSS Computational Methods in Social Sciences, III(1), 5–17.

Hernández-Prados, M. Á. (2022). Los ámbitos de la educación familiar: formal, no formal e informal. Participación educativa, 12, 29–39. https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/mc/cee/publicaciones/revista-participacion-educativa/sumario-n12.html

Hernández-Prados, M.Á., García-Sanz, M. P., Galián, B., & Belmonte, M.L. (2019). Implicación de familias y docentes en la formación familiar. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 22(3), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.22.3.388971

Hernández-Prados, M.Á., Gomariz, M.Á., Parra, J., & García-Sanz, M.P. (2015). El sentimiento de pertenencia en la relación entre familia y escuela. Participación educativa, 7, 45–57. https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/mc/cee/publicaciones/revista-participacion-educativa/sumario-n7.html

Hu, L.T., & Bentler, P.M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3, 424–453.

Janzen, R., Ochocka, J., Turner, L., Cook, T., Franklin, M., & Deichert, D. (2017). Building a community-based culture of evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning, 65, 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.08.014

Jeynes, W. (2023). A Theory of Parental Involvement Based on the Results of Meta-Analyses 1. In W. Jeynes (Ed.), Relational Aspects of Parental Involvement to Support Educational Outcomes: Parental Communication, Expectations, and Participation for Student Success (pp. 3–21). Taylor & Francis.

Kline, R. B. (2005) (2.ª ed.). Principle and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford.

Kurtulmus, Z. (2016). Analyzing Parental Involvement Dimensions in Early childhood Education. Educational Research and Reviews, 11(12), 1149–1153.

Landis, R., Edwards, B. D., & Cortina, J. (2009). Correlated residuals among items in the estimation of measurement models. In C. E. Lance & R. J. Vandenberg (Eds.), Statistical and methodological myths and urban legends: Doctrine, verity, and fable in the organizational and social sciences (pp. 195–214). Routledge.

León, V., & Fernández, M. J. (2017). Diseño y validación de un instrumento para evaluar la participación de las familias en los centros educativos. Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía, 28(3), 115–132. http://revistas.uned.es/index.php/reop/article/view/21622/17827

Lévy, J.P., & Varela, J. (2003). Análisis multivariante para Ciencias Sociales. Pearson-Prentice Hall.

LOMLOE (2020). Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de diciembre, por la que se modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación. (BOE de 30 de diciembre). https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2020-17264

López-Castro, M., & Pantoja, A. (2016). Diseño y validación de una escala para comprobar la percepción y satisfacción de las familias andaluzas en relación con los procesos tutoriales en centros de educación primaria. Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía, 27(1), 47–66.

Marsh, H. W., & Hocevar, D. (1985). Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First-and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychological Bulletin, 97(3), 562–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.97.3.562

McDonald, R.P., & Marsh, H.W. (1990). Choosing a multivariate model: Noncentrality and goodness of fit. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 247–255.

McNeal, R. B. (2012). Checking in or checking out? Investigating the parent involvement reactive hypothesis. The Journal of Educational Research, 105, 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2010.519410

Medina, F.N. (2015). Las variables complejas en investigaciones pedagógicas. Apuntes Universitarios, 5(2), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.17162/au.v0i2.244

Merchán-Ríos, R., Abad-Merino, S., & Segovia-Aguilar, B. (2023). Examination of the Participation of Roma Families in the Educational System: Difficulties and Successful Practices. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 13(1), 64–90. https://doi.org/10.447/remie.11616

Msila, V. (2012). Black parental involvement in South African rural schools: Will parents ever help in enhancing effective school management. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 2(2), 303–313. https://www.richtmann.org/journal/index.php/jesr/article/view/11841

Murray B., Domina T., Renzulli L., Boylan R. (2019). Civil society goes to school: Parent-teacher associations and the equality of educational opportunity. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 5(3), 41–63. https://doi.org/10.7758/RSF.2019.5.3.03

Ndubi, P. M., & Mugambi, M. M. (2019). Factors influencing completion of parents association projects in public secondary schools in Imenti South Sub-county, Kenya. International Academic Journal of Information Sciences and Project Management, 3(4), 210–232. http://www.iajournals.org/articles/iajispm_v3_i4_210_232.pdf

Novianti, R., & Garzia, M. (2020). Parental engagement in children's online learning during covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Teaching and Learning in Elementary Education (Jtlee), 3(2), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.33578/jtlee.v3i2.7845

Papakonstantinou, A. A. (2023). Teachers’ Perceptions Regarding School Parents’ Online Groups. Education Sciences, 13(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010060

Payà, A., & Tormo, M. (2016). La participación educativa de las familias en una escuela pública valenciana. Un estudio cualitativo. Foro de Educación, 14(21), 227–248. https://doi.org/10.14516/fde.2016.014.021.012

Peck, N. F., Maude, S. P., & Brotherson, M. J. (2015). Understanding preschool teachers’perspectives on empathy: A qualitative inquiry. Early Childhood Education Journal, 43, 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-014-0648-3

Rabadán, J. A., Benito, J., & Giorgi, A. (2022). El aprendizaje-servicio como metodología educativa y social. Dykinson.

Reparaz, R., Sanz, A., & González, P. (2018). La participación de las familias en el sistema educativo de Navarra. Influencia de los factores socioeconómicos y culturales. Gobierno de Navarra. Fondo de Publicaciones.

Siciliano, M. D. (2016). It’s the quality not the quantity of ties that matters: Social networks and self-efficacy beliefs. American Educational Research Journal, 53(2), 227–262. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216629207

Snell, E. K., Hindman, A. H., & Wasik, B. A. (2020). Exploring the use of texting to support family-school engagement in early childhood settings: Teacher and family perspectives. Early Child Development and Care, 190(4), 447–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1479401

Stacer, M. J., & Perrucci, R. (2013). Parental Involvement with Children at School, Home, and Community. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 34(3), 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-012-9335-y

Tan, C. Y., Lyu, M., & Peng, B. (2020). Academic benefits from parental involvement are stratified by parental socioeconomic status: A meta-analysis. Parenting, 20(4), 241–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2019.1694836

Torrego, J.C. (Coord.) (2019). La participación en los centros educativos de la Comunidad de Madrid. Consejo Escolar de la Comunidad de Madrid. https://www.comunidad.madrid/publicacion/ref/16449

Tran, Y. (2014). Addressing reciprocity between families and schools: Why these bridges are instrumental for students’ academic success. Improving Schools, 17(1), 18–29. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/soe_faculty/99

Uslu, F., & Gizir, S. (2017). School belonging of adolescents: The role of teacher-student relationships, peer relationships and family involvement. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 17(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2017.1.0104

Verdugo, M.A., Crespo, M., Badía, M., & Arias, B. (2008). Metodología en la investigación sobre discapacidad. Introducción al uso de las ecuaciones estructurales. VI Seminario Científico SAID. Salamanca: INICO.

Walker, J. M. T., Wilkins, A. S., Dallaire, J. R., Sandler, H. M., & Hoover-Dempsey, K. V. (2005). Parental involvement: Model revision through scale development. The Elementary School Journal, 106, 85–105. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/499193

Wheaton, B., Muthén, B., Alwin, D.F., & Summers, G.F. (1977). Assessing relability and stability in panel models. In D.R. Heise (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 84–136). Josseey-Bass. https://doi.org/10.2307/270754

Wilder, S. (2014). Effects of parental involvement on academic achievement: a meta-synthesis. Educational Review, 66(3), 377–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2013.780009

Youn, M. J., Leon, J., & Lee, K. J. (2012). The influence of maternal employment on children's learning growth and the role of parental involvement, Early Child Development and Care, 182, 1227–1246. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2011.604944

Contact address: Joaquín Parra Martínez. Universidad de Murcia, Dpto. de Métodos de Investigación y Diagnóstico en educación, Facultad de Educación. Campus de Espinardo, 30100-Murcia (España). E-mail: jparra@um.es

Dimensions and items of the Questionnaire Family Involvement in School, QFIS

A. Communication with the centre |

1. I attend meetings with the classroom teacher. |

2. I request meetings with the classroom teacher throughout the year. |

3. I attend group meetings with other parents and the classroom teacher. |

4. I speak with the classroom teacher in casual meetings at the beginning or end of the class. |

5. I have meetings with the other teachers. |

B. Involvement in school activities |

6. Workshops in the classroom (Reading, handicrafts, cooking, etc.). |

7. Cultural activities (historical facts, music topics, ecological, traditions, International Day of Peace, grandparents, children, women, etc.). |

8. Sport activities (tournaments or displays of football, basketball, judo, karate, etc.). |

9. Celebrations (Christmas, Carnival, end of year, etc.). |

10. Trips (to museums, monuments, other institutions, long trips, etc.). |

11. Service activities offered by the centre (homeroom, library, dining room, school transport, etc.). |

12. Work commissions in the centre (Plan for Coexistence, Improvement plan, etc.). |

13. Commission for classroom fundraising (gifts, costumes, classroom decorations, etc.). |

14. In the processes used to assess the centre (responding to forms, using a suggestions box, making complains and/or suggestions through the AMPA (association for parents of students) or individually, etc.) |

C. Sense of belonging |

15. I identify with the values, ideas, attitudes, goals, etc. of the centre. |

16. I consider myself to be a part of the centre. |

17. If a sporting, artistic or cultural team of the centre participates in any tournament or demonstration, I support that team. |

18. I trust the educational work of the teachers, supporting their decisions. |

19. I find the family activities or experiences offered by the centre appealing. |

20. Participating in the school makes me feel like I am a part of it. |

21. Since the beginning, I’ve felt welcomed and integrated by the education community. |

22. I’m satisfied with the education that my child receives at the school. |

23. I feel free to express my ideas, concerns, suggestions, complaints, etc. |

24. I would recommend this school to others with children. |

D. Home involvement |

25. I speak with my child about what he/she has done in class. |

26. I show my child that I trust him/her. |

27. I’m aware of my child’s attendance. |

28. I’m interested in my child’s homework. |

29. I’m concerned about how my child organises his/her time. |

30. I promote a good study environment at home (motivating the child to study, giving him/her a good space with no distractions, learning resources, etc.). |

31. I’m available to help my child with school work at any time. |

32. I congratulate my child after the completing of his/her school work. |

33. I give extracurricular or complementary activities to my child (languages, IT, music, dancing, sports, support lessons, etc.). |

34. I promote my child’s responsibility when studying, being on the lookout, but never completing the activities myself or being with the child the entire time. |

35. I ensure responsible use of computers, mobile phones, etc. |

36. In my family we participate in cultural activities (we read, we go to the cinema, theatre, museums, trips, concerts, exhibitions, etc. |

37. I try to ensure that my child uses the things learned in class in real life |

E. Involvement in the AMPA and the School Board |

38. I’m aware of the structure and functioning of the AMPA. |

39. I know members of the AMPA Board. |

40. I’m informed of the activities organised by the AMPA. |

41. I know the collection of books in which the AMPA takes part. |

42. I’ve looked for information about the AMPA on the internet, social networks, etc. |

43. I take part in activities organised by the AMPA. |

44. I am, I have been or I would be willing to be a member of the AMPA Board. |

45. I feel that the AMPA represents the interests of the families. |

46. I’m aware of the structure of the School Board. |

47. I know family representatives on the School Board. |

48. I’m informed of the decisions made in School Board meetings. |

49. I’m informed of the election process for the School Board (calendar, candidatures, election process, etc.) |

50. I vote in the elections for the School Board. |

51. I am, I have been or I would be willing to be a family representative of the School Board. |

F. Community involvement |

52. In collection activities (food, clothes, caps collection, charity markets, etc.). |

53. In ecological activities (cleaning of rivers, demonstrations for the environment, environmental awareness programs, tree planting, etc.). |

54. In neighbourhood activities (local parties, neighbour meetings, demonstrations for the needs of the neighbourhood, etc.). |

55. In charity and volunteer activities (helping the elderly, the ill, those with limited resources, those who are alone, soup kitchens, etc.). |

56. In activities of the different religious communities. |

57. In activities targeted to diversity awareness (gender, abilities, cultural background, ethnic, etc.). |

58. Activities to collaborate with youth associations to promote healthy leisure and free time activities. |

G. Training |

59. I’m informed of the training activities for families in the school. |

60. I attend training activities for families in the school. |

61. I take an active role in parent training activities (I ask questions, participate in debates, use what I’ve learned, etc.). |

62. I’m involved in the creation of training activities for families. |

63. I have sufficient training to improve my child’s education. |

64. The training offered by the centre helps to improve the family-school relationship. |