Reviewing the role of Education in the prevention of radicalisation in Europe

La Educación en la prevención del radicalismo: una revisión para Europa

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2022-397-545

Arantxa Azqueta

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2514-5989

Adoración Merino-Arribas

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3294-9996

Universidad Internacional de la Rioja

Abstract

This study analyses the extent to which global competence attitudes (OECD, 2018) - openness, respect, civic-mindedness, responsibility, self-efficacy and tolerance - are factored into the counter-radicalisation documents published by the governments of 16 European countries, whose placement into one of two control groups is determined by the presence or absence of fatalities following terrorist attacks. According to PISA’s assessment in 2018, these attitudes underpin the concept of democratic and inter-culturally competent citizenship. The project involves a comparative methodology with lexicographic content analysis (Iramuteq) and critical interpretive analysis which contextualises the documents. As shown by the results, the regulations of countries in which terrorist attacks have resulted in fatalities prioritise vigilance, seek to detect the threat, and regard education as a secondary concern. Conversely, in countries where terrorist attacks have not had deadly consequences, their regulations emphasise public safety and security, and contain hardly any references to education. The lexicographic analysis indicates that, of the 6 attitudes, the most highly valued are respect, responsibility and tolerance. At the other end of the scale are self-efficacy and civic-mindedness. The conclusion is that European policies on radicalisation are defective in terms of prevention and fail to address the issues of identity and inclusion, which are at the root of the problem. Moreover, while socio-educational policies are believed to be fundamental to the success of inclusion strategies, in practice they restrict the capacity of the school to detect signs of radicalisation and there is evidence of an increase in practices which suggest that education systems are being made subordinate to security agendas, whereby preventive responsibilities are assigned to schools and universities. There is a proposal for holistic and cross-cutting inclusion policies which, on the basis of an inter-cultural approach, reassess the role of the school, make education independent of security agendas and guard against political undercurrents which permeate counter-radicalisation discourse.

Key words: global competence, attitude, PISA, civic education, intercultural education, radicalization, extremism, inclusion, democracy.

Resumen

Esta investigación analiza si las actitudes de la competencia global (OECD, 2018) -apertura, respeto, conciencia cívica, responsabilidad, autoeficacia y tolerancia- se recogen en los documentos gubernamentales sobre prevención del radicalismo de 16 países europeos, aglutinados en dos grupos control, en función de la presencia o ausencia de víctimas mortales en los atentados. Estas actitudes, evaluadas por PISA en 2018, definen a una ciudadanía democrática e interculturalmente competente. Se emplea una metodología comparativa con un análisis de contenido lexicográfico mediante el software Iramuteq junto al análisis crítico-interpretativo que contextualiza los documentos. Los resultados señalan que las normativas de los países con víctimas mortales en atentados priorizan la vigilancia, buscan detectar la amenaza y la educación es secundaria. En cambio, los países sin víctimas mortales se centran en la seguridad y protección de la población, donde las referencias a la educación son prácticamente inexistentes. El análisis lexicográfico sobre la valoración de las 6 actitudes refleja que las más altas son: respeto, responsabilidad y tolerancia. Mientras que las más bajas son: autoeficacia y conciencia cívica. Se concluye que las políticas europeas sobre radicalización son débiles desde el punto de vista preventivo y no abordan las dificultades de identidad e inclusión que están en la raíz del problema. Además, aunque se considera que las políticas socioeducativas son un pilar para la inclusión, en la práctica limitan el papel de la escuela a la detección de brotes de radicalización y se evidencia la proliferación de prácticas que muestran la securitización de los sistemas educativos, que otorga responsabilidades preventivas a escuelas y universidades. Se sugiere promover políticas de inclusión holísticas y transversales, que desde un enfoque intercultural revaloricen el papel de la escuela, desvinculen la tarea educativa de las agendas de seguridad y se eviten las connotaciones políticas que impregnan el discurso preventivo de la radicalización.

Palabras clave: competencia global, actitud; PISA, educación cívica, educación intercultural, radicalización, extremismo, inclusión, democracia.

Introduction

Efforts to counter violent radicalisation in Europe have been addressed in official documents since 2005, with updates in 2008 and 2014 (Ruiz-Díaz, 2017) and 2020 (European Commission, 2020). European countries have respectively introduced measures to promote the inclusion not only of the immigrant population, but also of refugees and asylum seekers (Eurydice, 2019). This objective is in line with the aim of the Council of Europe, which originally set out to foster a European identity with a view to establishing greater unity among states and protecting fundamental freedoms and human rights (Council of Europe, 1949).

That is why Europe is facing significant challenges. The lack of trust in political processes, the political apathy of citizens, the lack of inter-cultural dialogue in culturally diverse societies and the rise in violent extremism are among the most critical threats to the values of freedom, citizenship and tolerance that lie at the very heart of Europe.

The 9/11 terrorist attack was a defining moment. Since then, Europe has perceived the terrorist threat to be a menace. Europe has also become a space where radicalisation and recruitment have thrived, and where the numbers of radicalised individuals have increased. Their profile is heterogeneous. However, they are connected by several characteristics such as religion and Islamic culture, socio-economic deprivation and cultural alienation (Municio, 2017). The radicalisation process revolves around a myriad of personal and structural factors such as socio-economic and cultural crisis, the need to belong in a disadvantaged environment and a lack of empathy with their situation or limited future prospects (Coolsaet, 2019).

Terrorist attacks have caused social upheaval, prompted a media backlash and posed a threat to traditional European values. Most terrorist attacks have been perpetrated by so-called “domestic combatants” influenced by the rhetoric of homegrown jihadism. They are predominantly second or third-generation European citizens of Muslim immigrants who have been born and raised in Europe (Municio, 2017). Meanwhile, the so-called “indigenous” population views Muslim immigration with increasing suspicion (Cesari, 2013).

Counter-radicalisation therefore figures prominently at the top of international agendas. The UN endorses action to Prevent Violent Extremism through Education (PVE-E) (General Assembly, 2016). Simultaneously, western democracies need to respond to the extremist attacks carried out in the name of a religion or ethnicity (OECD, 2018a). Europe attaches importance to the protection of the European spirit and has devised a strategy of broad-ranging initiatives which highlights the importance of the role that education systems can play in the prevention of radicalisation.

In the wake of the terrorist attacks in Paris in November 2015, European education ministers convened to sign the “Paris Declaration” (Eurydice, 2016). The document sets out a number of shared aims and policies in support of integration, social cohesion and the prevention of radicalisation (Eurydice, 2019).

The concept of global competence is a construct that draws inspiration from the work of Lambert (1993) who, in the context of globalisation, promotes the idea that education should adopt a cosmopolitan outlook. In addition, although different models of global education, education for citizenship, democratic education, education for sustainable development and inter-cultural education are developed on the basis of different approaches (cosmopolitanism, human rights, environmental sustainability or cultural diversity), they share the objective of fostering understanding of the world and preparing individuals to make an active and transformative contribution to - and on behalf of - society (Sanz-Leal, Orozco and Toma, 2022).

On the basis of UN guidelines (General Assembly, 2016), the OECD has formulated its strategy to set out the learning approaches required in societies that are experiencing rapid and profound change and in which social and cultural diversity is restructuring countries and communities (OECD, 2018b). A new multidimensional and permanent learning objective, in the form of “global competence”, is set and assessed in the 2018 tests of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) alongside the three standard fields of reading, mathematics and science. The aim is to assess the methods by which education systems prepare young people to embrace a diverse and peaceful society. Students are expected to learn how to converse, embrace other cultures, actively participate in social and political life and uphold principles of solidarity (OECD, 2018a, OECD, 2020).

PISA defines global competence in the following terms: “the capacity to examine global and inter-cultural issues, based on a support for human rights, in order to interact with people from different cultures, and to act for collective well-being and sustainable development” (OECD, 2018a: p. 4). Critics point to its evident Eurocentric approach (Auld and Morris, 2019; Grotlüschen, 2018), the lack of consensus and transparency around the framing of the concept (Engel, Rutkowski y Thompson, 2019), the challenge of assessing some aspects of the competence which diminishes its validity (Sälzer and Roczen, 2018) or that it is promoted along partisan lines with a view to legitimising the ideas that underpin the global competence model (Ledger et al., 2019; Robertson, 2021). In turn, while the indifferent and interchangeable identification of democratic competence and inter-cultural competence is criticised by Simpson and Dervin (2019), it is justified by Barrett and Byram (2020).

This study examines whether the global competence attitudes (OECD, 2018a) are considered in the counter-radicalisation regulations of 16 European countries. Secondly, an analysis is conducted to compare countries in which terrorist attacks have had deadly consequences, on the one hand, and those that have not, on the other.

Method

The research employs comparative methodology (Sartori and Morlino, 1994) based on two non-equivalent control groups.

Sample

The variables under analysis have been selected on the basis of the global competence descriptors (OECD, 2018a). They are thought to underpin the concept of democratic and inter-culturally competent citizenship, to express the intentions of governments and to shape domestic policies.

The conceptual framework of global competence was defined following a lengthy process of coordination involving the ministries of education of the member states of the Council of Europe. A total of 101 conceptual schemas of global, inter-cultural and civic competence were used, including 2,085 descriptors which were assessed and validated according to three criteria: clarity, precision and observability. The descriptors were statistically scaled according to the Rasch model which was used to compare cultures. They were finally simplified into 20 multivariable elements including 3 sets of values, 6 attitudes, 8 skills and 3 bodies of knowledge (Council of Europe, 2016a, 2016b).

Analysing the multivariable elements of knowledge and skills has been ruled out as they have been part of educational programmes for longer periods of time (Naval, Print and Veldhuis, 2002). So too has analysis of values as, despite their importance, their assessment is particularly complex and they are not examined by PISA either (OECD, 2018a).

The analysis in respect of attitudes is justified because they are critical in adolescence and during school years (period in which principles and future moral standards are formed). Secondly, because education strategies that promote attitude change are the means by which to improve the capacity for dialogue, reflection and participation (García-López and Sales, 1998), they contribute to the construction of a European citizenship (Viejo, Gómez-López and Ortega-Ruiz, 2019) and, conversely, attitude changes may be a precursor to ideological changes which pave the way for violent radicalisation (de la Corte and Muro, 2020). Finally, because they do not tend to be included in intervention programmes (Burde et al., 2015). The particular multivariable elements connected with attitudes are therefore analysed: openness, respect, civic-mindedness, self-efficacy and tolerance, as conceptualised by the Council of Europe (Council of Europe, 2016a) and adopted by the OECD (OECD, 2018a).

The scourge of violent radicalisation is a reality facing all European countries, albeit to varying degrees of intensity (Nessert, 2018). It is assumed that the presence or absence of fatalities during terrorist attacks will mark a differentiating factor in the level of concern and public alarm and may set the tone of the message contained in official documents (Bermejo-Laguna, 2018). In light of this criterion, two groups are distinguished:

- The first group represents the counter-radicalisation plans issued by the governments of European countries whose national territories were affected by deadly jihadi attacks between 2015 and 2020. These countries are: Spain, Sweden, Germany, Denmark, Austria, Belgium, France, United Kingdom, and Finland (Table I).

- The second group encompasses the official counter-radicalisation documents of European countries in which terrorist attacks did not have deadly consequences between 2015 and 2020. These countries are: Albania, Lithuania, Portugal, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Slovenia and Norway, which represent different European cultural traditions (Mediterranean, Baltic, Balkan, Nordic and Central European) (Table II).

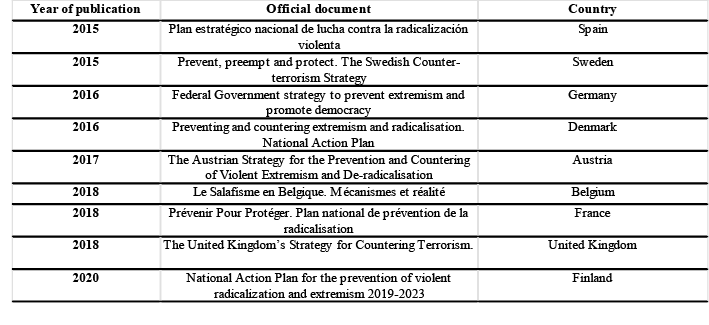

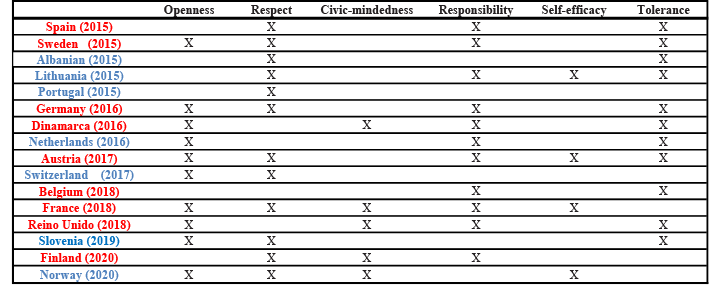

TABLE I. Official documentation (2015-2020) of European countries in which terrorist attacks have had deadly consequences

TABLA II. Official documentation (2015-2020) of European countries in which terrorist attacks have not had deadly consequences.

Instrument

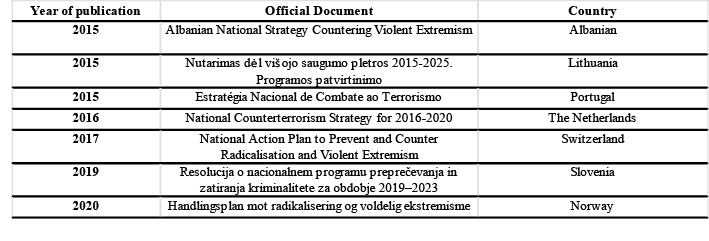

Analysis is carried out in two phases:

- Phase 1: Analysis of lexicographic content based on co-occurrence clustering or grouping techniques, because it displays the data and is suitable for comparative studies characterised by a large volume of digitised documentation. The lexicographic analysis software Iramuteq (Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires) is used. Lexical profiles - both of words and of lexemes - are assessed to analyse terms, to identify networks of correlations and similarities, and to create a hierarchical structure for the primary lexical worlds of discourse, such that the general semantics of the narration are identified. However, such a large volume of relational information is produced that it is not legible. Consequently, a pruning algorithm must be used (Kamada-Kawai, 1989) to display the relevant information. Finally, textual analysis templates including a quantitative and comprehensive description of the vocabulary are produced to facilitate the extraction of non-explicit information from the texts (Reinert, 1990).

- Phase 2: The study is completed by a critical and interpretative analysis of the documents. This required subject matters to be identified and the core messages of documents to be categorised and interpreted (Bardin, 2002).

Data collection and Analysis Procedure

The procedure specified in figure I has been implemented.

IMAGE I. Procedure implemented during the research project

Source: produced by the authors of this study

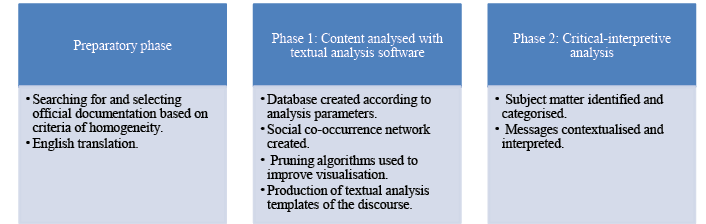

The software generates approximately 800 co-occurrences (lexical units within a text corpus, which have lexical similarity among the included forms). As the project involves data mining analysis, the 80 co-occurrences with the highest value have been selected to produce colour graphs in which the results of this research project are visually represented. The resulting information is relational between forms, based on research objectives. The software generates an image of ramifications of distinguished clusters, which unite related words in view of their proximity to the subject matter under study. The colours of clusters are random and distinguish common blocks. The greatest frequency of words is graphically represented by the largest size and the thickness of links shows the importance of their relationship: key words are in the graph nodes and reflect the co-occurrence between them.

Results

The graphs featured in Figures II and III have been produced on the basis of the analysis tool. Each image displays the network of similarities in such a way that it is possible to highlight the models or priorities that each set of countries has followed in relation to the prevention of radicalisation on their territory.

FIGURE II. Network of common co-words generated on the basis of the documentation (2015-2020) of countries in which terrorist attacks have had deadly consequences -table I-.

Source: produced by the authors of this study

The network of similarities between the plans of the first group revolves around threat which is present in every document. The centre of the graph features words which express the priorities of the programmes, not including any of the key words under analysis. The purpose is to monitor in order to prevent violent acts and to keep the population safe. The central cluster is surrounded by another aspect common to prevention plans: security. Governments prioritise vigilance and police intervention to prevent violent acts and locate the incipient terrorist activity. Words related to preventive factors are included laterally. This is where education and school are found. The size of these terms and their peripheral location suggest that they are secondary elements. While the term “radicalisation” is repeatedly referenced in all plans, the term “education” appears sporadically. This would indicate that its role is still embryonic and marginal. Although the documents of this group are qualified as preventive, the analysis shows that they place a considerable emphasis on security and that their message to citizens is geared towards security and protection.

FIGURE III. Network of common co-words generated on the basis of the documentation (2015-2020) of countries in which terrorist attacks did not have deadly consequences -Table I-.

Source: produced by the authors of this study

The network of similarities between countries without fatalities is characterised by the core objective of security, both of territories and their citizens. “Security” is the most relevant word on account of its centrality and its size. On the other hand, they are aware of the threat and seek to keep extremism under control. This is also the location of programmes and public services which help to shape social policies and foster cooperation. However, references to education are practically non-existent and vague, and occupy residual positions.

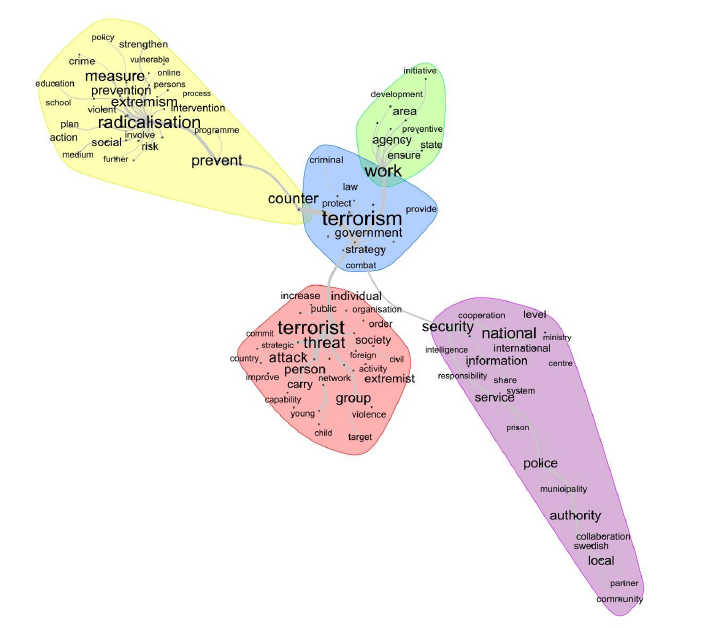

Table III outlines whether the documents include explicit references to global competence attitudes. The documents are considered in the chronological order of their publication. They are differentiated by colour: whether the terrorist attacks occurring on their territories have (red) or have not (blue) had deadly consequences. A network graph is included for the sake of clarity (Figure IV).

TABLE III. Inclusion of attitudes analysed in documents issued by European governments.

Source: produced by the authors of this study

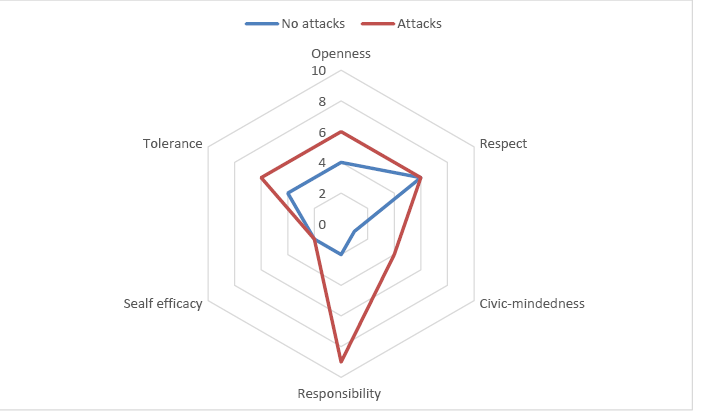

FIGURE IV. Presence of global competence attitudes in European documents.

Source: produced by the authors of this study

Figure IV shows the inclusion of the global competence attitudes, following the lexicographic analysis of the documents:

- The attitudes with the highest rating are responsibility, tolerance and respect which shape discourse in virtually all European countries. In respect of whether the presence of attacks with fatalities will mark a differentiating factor, there is a contrast in the attitude of responsibility, which includes the greatest disparity of results. While it is considered to be vital in counties where attacks have had deadly consequences, this is not reflected in counties where attacks have not resulted in fatalities. The former appeal to the responsibility of citizens, which is particularly evident in some sectors such as social workers, health workers and educators, who are tasked with detecting risk factors. However, responsibility is not a required attitude in countries where the attacks have not resulted in fatalities. It is only included by Lithuania and the Netherlands.

- The attitudes with the lowest rating are self-efficacy and civic-mindedness. In the latter, a difference is observed in the two groups of countries. Its presence is more prominent in countries with fatalities than in the other group, where it is only present in Norway, the country that has produced the most recent prevention plan (2020).

The critical-interpretative analysis of documents with references to prevention through education yields clear results.

As shown by Table I (countries with fatalities between 2015-2020):

The plan produced by Spain (Gobierno de España, 2015) focuses on public security and seeks to identify dangerous micro-scenarios. While it makes no explicit reference to the education system, it takes the view that it has a collaborative role to play.

Sweden (Government Office of Sweden, 2015) concludes that radicalisation is an insidious process that develops through social contracts with charismatic leaders. Young people are introduced to extremist groups through friends or family who already belong to these groups.

Germany (Federal Government, 2016) has produced a preventive programme in which references to school and family are among the 20 most commonly cited terms. It underscores the importance of a young person’s education, as the majority of radicalised individuals in this country are between the ages of 18 and 24, and some 20% are between 12 and 17.

Denmark (Danish Ministry of Immigration, Integration and Housing, 2016) has devised a proposal which primarily aims at diverting young people away from radicalisation. As part of the proposal, a subject on human rights is added to the curriculum and counter-radicalisation initiatives and materials are proposed. It has introduced a scheme whereby a national group of professional mentors and instructors (parents) support families at risk.

As for Austria (Federal Ministry of the Interior of Austria, 2017), it has expressed concern about the rise in terrorist activity across its territory, especially among young people of an immigrant background. It is supportive of the idea that extremism can be countered by addressing the healthcare and educational needs of young people. It analyses the causes of radicalisation and identifies reasons for social and structural exclusion.

In Belgium (Veiligheid van de staat, 2018), the spotlight is placed on Salafism, which is hostile to western and democratic values. Its educational policies offer training programmes for teachers and students and a hotline is made available to report cases of radicalisation.

France (Gouvernement République Française, 2018) has a relatively ineffective plan in terms of prevention and makes no mention of integration or diversity. It primarily defends republican values, opts to secularise Islam and upholds secularism as a basic principle. It aims to detect cases quickly, given that extremists may live among its citizens, and provides a prevention guide for teachers outlining how to detect cases of radicalisation in schools. It has developed digital literacy and citizenship modules in a bid to counter the risk of radicalisation.

The United Kingdom (Her Majestic´s Government of United Kingdom, 2018), a beacon of social and cultural diversity, does not qualify diversity as a strength. In 2015, it passed a law which legally requires schools, universities and teachers to prevent young people from being radicalised. Education and health systems are made subordinate to security agendas and rely on the cooperation of citizens who have a duty to remain vigilant and prevent. Its effects include “Britishness” whose aim is to promote British identity and values through education, as a way of fostering community cohesion (Matthews, 2016). The plan has sparked a public debate which is currently ongoing. While the plan is supported by some (Walker and Cawley, 2020), it is criticised by others the reason that it muzzles free speech in schools or universities (O´Donnell, 2016), undermines confidentiality and trust (Lumb, 2018), poses a threat to policies that promote equality (Jerome, Elwick and Kazim, 2019), and increases suspicion of some groups, not least young Muslims (Busher, Choudhury and Thomas, 2020).

Finland (Ministry of the Interior, 2020) stresses the importance of education, and especially early education, because it promotes the inclusion of minors. It endorses an educational and social well-being policy as well as a successful employment policy. It has set up multi-disciplinary task forces (educators, police officers, families, schools, etc.) to provide special support to teenagers who are at risk of being radicalised.

As regards the documents of the European countries in the second group (Table II):

Albania (Republic of Albania, 2015) is considered to be one of the most susceptible countries to radicalisation, given its geographic location and the fact that 50% of its population is Muslim. Albanian researchers suggest that the country is free from the threat of extremism in view of the inter-religious harmony that has traditionally existed there (Hide, 2015) and of the need for stability that its population so desperately craves (Vrumo, Lamllari and Papa, 2015). The plan supports the view that schools and teachers can stimulate cohesion and effectively contribute to counter-radicalisation efforts.

The Lithuanian strategy (Lietuvos Respublikos Seimas, 2015) includes succinct references to radicalisation. It takes the view that it poses a significant risk to public security and warns that cyberspace is a breeding ground for radicalisation.

Portugal (Conselho de Ministros do Portugal, 2015) has produced a vague plan which highlights the need for all sectors of civil society to work together and makes clear the challenge posed by the use of the internet in the radicalisation process.

The programme of the Netherlands (National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism, 2016) consists of preventive, repressive and corrective measures. Like social or healthcare services, the education system is viewed as a means of detecting suspicious behaviour. As for as education is concerned, the policy in relation to immigration has changed course. Funding has been diverted away from some programmes which seek to promote inclusion in schools and equity in education for children of immigrants, for instance the remedial initiatives intended for disadvantaged children of immigrant backgrounds under the Early Childhood Education Intervention Programmes, and language and culture courses.

Switzerland (Swiss Security Network, 2017) has devised a preventive plan setting out initiatives to raise awareness of national identity, promote research and foster inclusive education in schools and universities. It states that individuals can be radicalised by their friendships and online interactions.

Slovenia (Republike Slovenije, 2019) notes that radicalisation clearly represents a cross-border risk. Some factors, such as geographic location, background and culture or ethnicity of the population represent a significant different in respect of other European countries.

Norway (Justis og beredskapsdepartementet, 2020) has adopted a holistic approach with an emphasis on prevention and working with young people. Schools are the medium through which students are taught about democracy and they undertake initiatives to train teachers, promote the use of digital resources, enhance terrorism resilience, etc. Norwegians have long echoed the concerns of their Scandinavian neighbours, in so far as they relate predominantly to the supremacist threat.

Conclusions

The comparative methodology with two phases of analysis is appropriate because it addresses crux of the matter and the key elements of the documents. The combination is complementary and adds balance to the research. The lexicographic analysis with Iramuteq provides rigour, objectivity and graphical visualisation. It is further enhanced by the critical and interpretative analysis which serves to contextualise the documents and adds depth.

In light of the conclusions drawn from the study of the extent to which global competence attitudes are considered by 16 European countries, it is possible to formulate recommendations for the improvement of counter-radicalisation policies through education:

Firstly, it is concluded that European policies on radicalisation are defective in terms of prevention and fail to address the issues of identity and inclusion, which are at the root of the problem. While countries from the first group - where the terrorist attacks have deadly consequences - prioritise vigilance and seek to detect the threat, countries from the second group - where attacks did not have deadly consequences - focus on security and protection of population. They all tend to adopt “hard” prevention strategies (Sjøen and Jore, 2019) which occasionally have adverse effects both on young people who are viewed with suspicion, and on some communities, not least Muslim communities, which are stigmatised (Ragazzi, 2017).

According to Innerarity (2006), Europe has become a paradigm and an “integration laboratory”. This marks the beginning of the challenge facing the European citizen of the 21st century. We live in a multi-ethnic society where the concept of citizenship has evolved from the idea of national citizenship which revolves around shared cultural identities to one which links solidarity between communities to civic and democratic values (Innerarity and Acha, 2010). These circumstances call for “ethical humanism” which promotes “responsibility towards the other” and “consideration for the diverse” (Bauman, 2012). In this respect, Thoillez (2019) notes that relations built on recognition and communication are more likely than a respect for individual freedom, as enshrined in law, to create an environment in which the characteristics and attributes of others are recognised, valued and respected.

The concept of inclusion is a two-way street. It concerns all parties exposed to different cultures in this new context and requires integration models to prioritise an inter-cultural approach. If the identity of a specific population was once defined by culture, nation or religion, this definition is no longer fit for purpose. Inclusion implies a positive assessment of difference whereby social, cultural and political structures are subordinate to respect, acceptance and recognition of the other as a human being whose intrinsic dignity takes precedence over social consideration.

It is difficult to combine European identity with other cultural, national, racial and religious identities. Society is in a process of transformation, the future result of which is far from certain. However, a statistical relationship does not always exist between education and the rejection of violence and extremism (Gielen, 2017). Brockhoff, Krieger and Meierrieks (2015) state that, while education has a key role to play in mitigating the risks of radicalisation, its impact is actually subject to a number of factors, and educational measures ought to go hand-in-hand with improvements in socio-economic, politico-institutional and demographic spheres. If these spheres are unfavourable, education may lead directly to terrorism and increase feelings of frustration and humiliation. According to Aly, Balbi and Jacques (2015), radicalisation is a complex phenomenon which requires cross-cutting and comprehensive preventive measures.

Secondly, the consideration given to education is either secondary (countries with fatalities) or practically non-existent (countries without fatalities). In theory, socio-educational policies have a fundamental role to play in addressing the issue of integration (Eurydice, 2016, 2019). However, in practice, the analysis concludes that the documents reduce education and the school to a relatively insignificant role and limit their preventive function to the detection of the first signs of radicalisation. It should be noted that the documents produced in 2020, such as those issued by Finland and Norway, adopt a more comprehensive and inter-disciplinary approach to prevention, to the extent that while educational measures continue to be subordinate to security agendas, they at least exist in greater numbers and are developed in a more exhaustive manner.

As indicated by Musaio (2021), an “inter-cultural citizenship” project is needed to shape the inter-cultural approach to services which protect the human rights of the most vulnerable, and to promote inclusive education practices. Thus, education encourages pupils to accept personal identities and “otherness” of the other in advance of the recognition of their cultural background (Merino-Mata, 2004). Similarly, Balduzzi (2021) highlights the mission that schools can undertake as an “educational community” which contributes not only to the development and personal improvement of pupils, but also to the construction of a shared cultural project.

Our proposal notes that the preventive task requires an unambiguously inter-cultural approach which facilitates inclusion and constructs, in practice, a democratic citizenship. School creates a stronger sense of belonging, shapes personal identity, increases resilience, raises awareness of democratic practices and promotes the public good and the pursuit of a shared future beyond the context of education. Alongside families, schools can act as a conduit through which to create a fairer society. During our school years, we form the principles which will shape our lives moving forward and are exposed to the ideal environment in which to normalise behaviours which create emotional bonds and friendships between pupils. An inter-cultural school paves the way for a democratic culture which helps to forge a relational and social sense of existence itself. School facilitates contact among equals; it enables different individuals to form relationships and interact; and it teaches pupils to value different identities and to develop the skills they need to converse with others. Miguel-Luken and Carvajal (2007) point out that, as school is a space in which individuals are required to co-exist, it represents an environment where they can become known to and valued by others, regardless of their origin. More often than not, difficulties arise in other spaces of co-existence where interaction is neither present nor promoted, and where it is easier for prejudices to take hold. Exposure to different cultures in these spaces of co-existence enables teenagers to accept customs, languages, ethnicities and religions different from their own, so much so that these situations shape their personality (Azmitia, Ittel and Radmacher, 2005), and teach them to compromise in order to resolve a dispute and to show greater sensitivity to differences based on diverse cultural perspectives (Villalobos-Carrasco, Álvarez-Valdivia and Vaquera, 2017). Moreover, as school not only fosters interaction between different groups, but also social mixing (Thoillez, 2019), pupils will develop better social skills and be more likely to succeed in the future (Checa and Arjona, 2009). However, schools are not immune to cultural tensions. It is preferable to avoid situations in which pupils of immigrant backgrounds or from stigmatised groups are predominantly allocated places in particular deprived areas and education centres (Ponce, 2007). Segregation in these schools goes hand-in-hand with disadvantaged socio-economic circumstances which act as a barrier to inclusion and makes these establishments prone to the risk of radicalisation.

Thirdly, the close links between security and education have received widespread political support (Durodié, 2016). Responsibility is the most relevant attitude in the documentation and shapes the discourse of preventive policies in the European countries of the first group - table I. This approach is far removed from the ethical focus of responsibility (Bauman, 2012) and points to the subordination of education systems to security agendas, whereby preventive responsibilities are assigned to schools and universities. That is why several countries require teachers to monitor risk indicators with a view to detecting cases of radicalisation, based on a prevention guide for teachers and headteachers. This form of vigilance has become a legal requirement in the United Kingdom. Belgium and France are also developing systems in which educators will be expected to detect signs or cases of radicalisation and these concepts are spreading to other countries such as Sweden and Spain.

It is widely accepted that the presence of fatalities in terrorist attacks not only increases suspicion and social hostility, but also causes European governments to prioritise counter-radicalisation policies: every country in which attacks have had deadly consequences have developed preventive plans and civic integration programmes. However, this is not the case in counties without fatalities. Only Switzerland and Norway have devised plans similar to those of countries from the first group. In all the others, while references to radicalisation are included in security and counter-radicalisation strategies, they do not amount to preventive plans per se. It should be noted that, in the case of Albania and Slovenia, whose populations are characterised by a high percentage of Muslims and where inter-religious harmony has traditionally existed, they view radicalisation as a cross-border rather than an internal political issue, which is why matters of radicalisation are included in general strategies.

That is why it is preferable to make education independent of security agendas and guard against political undercurrents which permeate counter-radicalisation discourse. The subordination of education systems to security agendas has been deeply criticised in Europe, where individual freedoms and rights are deemed to be fundamental. However, academic literature on education and security studies has recently indicated that, even from opposing points of view, the subordination of education systems to security agendas is not an unfamiliar concept and illustrated the point with some past cases (Gearon, 2015; Stonebanks, 2019).

The analysis considers the extent to which it may be appropriate for European radicalisation policies to consider an integrated approach with cross-cutting policies, where social aspects take precedence over security agendas and where the issues of identity and inclusion are addressed. It is also suggested that preventive policies should afford schools a greater role, such that, as part of an inter-cultural strategy that is independent of security agendas, they are in a position to contribute to the creation of societies that are more cohesive, more democratic and inclusive, and more resistant to extremism. Schools are spaces in which humanity should be allowed to flourish.

Limitations and outlook

This research is limited to an extent, for instance in respect of the numerous languages in which the documentation is produced. As all the documentation had to be standardised with a translation into English, some important nuances may have been lost in translation. We also found it particularly difficult to access this documentation and find the latest versions, as the speed with which the wheels of domestic legislation turn varies from one country to the next.

Prospective analysis may enlarge the analysed sample of countries and European regions and may even incorporate new categories of analysis. It would also be appropriate to consider the autonomous communities and European regions which have their own special regulations in this respect.

References

Aly, A., Balbi A.-M. & Jacques, C. (2015). Rethinking Violent Extremism: Implementing the Role of Civil Society. Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism 10(1), 3-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/18335330.2015.1028772

Auld, E. & Morris, P. (2019). Science by streetlight and the OECD’s measure of global competence: A new yardstick for internationalisation? Policy Futures in Education, 17(6), 677-698 https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210318819246

Azmitia, M., Ittel, A. & Radmacher, K. (2005). Narratives of friendship and self in adolescence. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 107, 23-39. https://doi.org 10.1002/cd.119.

Balduzzi, E. (2021). Por una escuela vivida como comunidad educativa. Teoría de la Educación, Revista Interuniversitaria, 33(2), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.23774

Bardin, L. (2002). Análisis de contenido (third edition). Madrid: Akal.

Barrett, M. & Byram, M. (2020). Errors by Simpson and Dervin (2019) in their description of the Council of Europe’s Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture. Intercultural Communication Education, 3(2), 75-95 https://doi.org/10.29140/ice.v3n2.286

Bauman, Z. (2012). Amor líquido. Sobre la fragilidad de los vínculos humanos. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Bermejo-Laguna, J. (2018). Multiculturalismo, islam y yihadismo en Europa: análisis de sus políticas multiculturales. Revista de Pensamiento Estratégico y Seguridad, 3(2), 75-89.

Brockhoff, S., Krieger, T. & Meierrieks, D. (2015). Great expectations and hard times: The (nontrivial) impact of education on domestic terrorism. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 59(7), 1186-1215.

Burde, D., Guven, O., Kelcey J., Lahmann, H. & Al-Abbadi, K. (2015). What Works to Promote Children’s Educational Access, Quality of Learning, and Wellbeing in Crisis-Affected Contexts. Education Rigorous Literature Review. London: Department for International Development.

Busher, J., Choudhury, T. & Thomas, P. (2020). The introduction of the Prevent duty into schools and colleges: stories of continuity and chance. In J. Busher y L. Jerome (Eds.). The prevent duty in education: impact, enactment and implications (pp. 33-54). London: Palgrave-Mc.Millan.

Cesari, J. (2013). Why the west fears Islam: An exploration of Muslims in liberal democracies. Basingstoke: Springer.

Checa, J. & Arjona, Á. (2009). La integración de los inmigrantes de “segunda generación” en Almería. Un caso de pluralismo fragmentado. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 67(3), 701-727. http://doi.org/10.3989/ris.2008.04.17

Conselho de ministros do Portugal (2015). Estratégia Nacional de Combate ao Terrorismo. Diário da República, 1ª série, nº 36 (20 de fevereiro 2015). https://bit.ly/3lkWZsO

Coolsaet, R. (2019). Radicalization: The origins and limits of a contested concept. In N. Fadil (Coord) Radicalisation in Belgium and the Netherlands: Critical Perspectives on Violence and Security (pp. 29-51). London: IB Tauris.

Corte de la, L. & Muro, D. (2020). Certezas e incertidumbres sobre la radicalización terroristas (pp. 47-62). In VV. AA Cómo prevenir la radicalización yihadista, Prácticas exitosas, dilemas e incertidumbres. Report Victims of Terrerism Memorial Centre, nº 10. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Victims of Terrorism Memorial Centre. https://n9.cl/40gy

Council of Europe (1949). Statute of Council of Europe, London, May 5, 1949. https://rm.coe.int/1680306052

Council of Europe (2016a). Competences for democratic culture: Living together as equals in culturally diverse democratic societies. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. https://bit.ly/2FuwFHE

Council of Europe (2016b). Reference framework of competences for democratic culture: guidance for implementation (I-III). Strasbourg: Council of Europe. http://xurl.es/e75m5

Danish Ministry of Immigration, Integration and Housing (2016). Preventing and countering extremism and radicalisation. National Action Plan. https://cutt.ly/1HAcwQp

Durodié, B. (2016). Securitising education to prevent terrorism or losing direction. British Journal of Educational Science 64(1), 21-35. http://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2015.1107023

Engel, L, Rutkowski, D. & Thompson, G. (2019). Toward an international measure of global ompetence? A critical look at the PISA 2018 framework. Globalisation, Societies & Education. 17(2), 117-131 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2019.1642183

European Commission (2020). Communication from the Commission to the European Parlament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, 9.12. 2020. A Counter-Terrorism Agenda for the EU: Anticipate, Prevent, Protect,Respond. COM (2020) 795 final.

Eurydice (2016). Promoting citizenship and the common values of freedom, tolerance and non-discrimination through education: Overview of education policy developments in Europe following the Paris Declaration of 17 March 2015. Luxembourg: Publications Office EU. https://doi.org/10.2797/396908

Eurydice (2019). Integrating students from migrant backgrounds into schools in Europe: national policies and measures. Louxembourg: Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency. https://doi.org/10.2797/819077

Federal Goverment (2016). Federal Government strategy to prevent extremism and promote democracy. Berlin: Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend. https://bit.ly/2DlTQFS

Federal Ministry of the Interior of Austria (2017). The Austrian Strategy for the Prevention and Countering of Violent Extremism and De-radicalisation. Vienna: Federal Agency for State Protection and Counter Terrorism. https://bit.ly/2YAeeN7

García-López, R. & Sales, A. (1998). Formación de actitudes interculturales en la Educación Secundaria: Un programa de educación intercultural, Teoría de la Educación, Revista Interuniversitaria, 10, 189-204

Gearon, L. (2015). Education, Security and Intelligence Studies. British Journal of Educational Studies 63(3), 263–379 https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2015.1079363

General Assembly (2016). Resolución 70/L.41. Culture of peace. Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism. Seventieth session (9 february 2016).

Gielen, A. (2017). Countering Violent Extremism: A Realist review for assessing what works, for whom, in what circumstances, and how? Terrorism and Political Violence 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2017.1313736.

Gobierno de España (2015). Plan Estratégico Nacional de Lucha contra la Radicalización Violenta. Un marco para el respeto y el entendimiento común. Madrid: Ministerio del Interior. https://bit.ly/2gyz3jA

Gouvernement Republique Française (2018). Prévenir Pour Protéger. Plan national de prévention de la radicalisation. https://bit.ly/2yaiV3c

Government Office of Sweden (2015). Prevent, preempt and protect. The Swedish counter-terrorism strategy. (Skr. 2014/15:146) Government Communication Office. https://bit.ly/2YwhLfo

Grotlüschen, A. (2018). Global competence. Does the new OECD competence domain ignore the global South? Studies in the Education of Adults, 50(2), 185-202. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2018.1523100

Her Majestic´s Goverment of United Kingdom (2018). The United Kingdom’s Strategy for Countering Terrorism. https://bit.ly/2Js6G8J

Hide, E. (2015). Assessment of risks on national security/ the capacity of state and society to react: Violent Extremism and Religious Radicalization in Albania. Albanian Institute for International Studies https://cutt.ly/tkMiBbM

Innerarity, D. (2006). El nuevo espacio público. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe.

Innerarity, C. & Acha, B. (2010). Los discursos sobre ciudadanía e inmigración en Europa: universalismo, extremismo y educación, Política y sociedad, 47(2), 63-84.

Jerome, L., Elwick, A. y Kazim, R. (2019). The impact of the Prevent duty on schools: A review of the evidence. British Educational Research Journal, 45(4), 821-837. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3527

Justis og beredskapsdepartementet (2020). Handlingsplan mot radikalisering og voldelig ekstremisme. https://cutt.ly/tk5IHkE

Kamada, T. & Kawai, S. (1989). An agorithm for drawing general undirected graphs. Information pocessing letters, 31, 7-15.

Lambert, R. (1993). Educational Exchange and Global Competence. 46th International Conference on Educational Exchange. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED368275.pdf

Ledger, S., Their, M., Baile, L. & Pitts, C. (2019). OECD’s approach to measuring Global Competency: Powerful voices shaping education. Teachers College Record, 121, 1-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811912100802

Lietuvos Respublikos Seimas (2015). Nutarimas dėl viešojo saugumo plėtros 2015-2025 Programos patvirtinimo https://bit.ly/3grgAUH

Lumb, E. (2018). Terrorism in the Nursery: considering the implications of the British Values discourse and the Prevent duty requirements in early years education, Forum, 60(3), 355-364. http://doi.org/10.15730/forum.2018.60.3.355.

Matthews, J. (2016). Media performance in the aftermath of terror: Reporting templates, political ritual and the UK press coverage of the London Bombings, 2005. Journalism 17(2), 173-189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884914554175

Merino-Mata, D. (2004). El respeto a la identidad como fundamento de la educación intercultural. Teoría de la Educación Revista Interuniversitaria, 16, 49-64. https://doi.org/10.14201/3068

Miguel-Luken, V. & Carvajal, C. (2007). Percepción de la inmigración y relaciones de amistad con los extranjeros en los institutos. Migraciones, 22, 147-190.

Ministry of the Interior Finland (2020) National Action Plan for the prevention of violent radicalization and extremism 2019-2023. Helsinki: Government Administration-Department Publications. https://cutt.ly/cHAbnbb

Municio, N. (2017). Evolución del perfil del yihadista en Europa. Boletín del Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos, 6, 556-573.

Musaio, M. (2021). Rethinking the fundamentals and practices of intercultural education in an era of insecurity. Bordón, 73(1), 97-110, http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1555-7314

National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism (2016). National Counterterrorism Strategy for 2016-2020.

Naval, C., Print, M. y Veldhuis, R. (2002). Education for Democratic Citizenship in the New Europe: Context and Reform. European Journal of Education, 37(2), 107-128

Nesser, P. (2018). Islamist terrorist in Europe. Oxford University Press.

O´Donnell, A. (2016). Securitisation, counterterrorism and the silencing of dissent: The educational implications of Prevent. British Journal of Educational Studies, 64(1), 53–76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2015.1121201

OECD (2018a). Preparing our youth an inclusive and sustainable world. The OECD PISA global competence framework. Paris: OECD. https://cutt.ly/rr6fMVl

OECD (2018b). The Future of Education and Skills OECD Education 2030 Framework. Paris: OECD Publishing, https://bit.ly/2IhJXYs

OECD (2020). PISA 2018 Results (Volume VI): Are Students Ready to Thrive in an Interconnected World? OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/d5f68679-en.

Ponce, J. (2007). Segregación escolar e inmigración. Contra los guetos escolares: Derecho y políticas públicas urbanas. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales.

Ragazzi, F. (2017). Students as suspects: The challenges of counter-radicalization policies in education in the Council of Europe member states. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. https://cutt.ly/Hr5bhhL

Reinert, M. (1990). Alceste: une méthodologie d’analyse des donne textuelles et une application: Aurélia de G. de Nerval. Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique, 26(1), 24-54.

Republic of Albania (2015). Albanian National Strategy Countering Violent Extremism, 930, 18 November 2015. Official Gazette of the Republic of Albania (203/2015). https://cutt.ly/gkMgrJG

Republike Slovenije (2019). Resolucija o nacionalnem programu preprečevanja in zatiranja kriminalitete za obdobje 2019–2023 https://bit.ly/31sGCTp

Robertson, M. (2021). Provincializing the OECD-PISA global competences project. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 19(2), 167-182. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2021.1887725

Ruiz-Díaz, L. (2017). La prevención de la radicalización en la estrategia contra el terrorismo de la Unión Europea: entre soft law e impulso de medidas de apoyo. Revista Española de Derecho Internacional, 69(2), 257-280 http://dx.doi.org/10.17103/redi.69.2.2017.1.10

Sälzer, C. & Roczen, N. (2018). Assessing global competence in PISA 2018: Challenges and approaches to capturing a complex construct. International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, 10(1), 5-20. https://doi.org/10.18546/IJDEGL.10.1.02

Sanz-Leal, M., Orozco, M. y Toma, R. (2022). Construcción conceptual de la competencia global en educación, Teoría de la Educación, Revista Interuniversitaria, 34(1), 83-103. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.25394).

Sartori, G. & Morlino, L. (1994). La comparación en las Ciencias Sociales. Madrid: Alianza.

Simpson, A. & Dervin, F. (2019). Global and intercultural competence for whom? By whom? For what purpose? An example from the Asia Society and the OECD. Compare. Journal of comparative and international education, 49(4), 672-677. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2019.1586194

Sjøen, M. & Jore, S. (2019). Preventing extremism through education: exploring impacts and implications of counter-radicalisation efforts Journal of Beliefs & Values, 40(3), 269-283 https://doi.org/10.1080/13617672.2019.1600134

Stonebanks, C. (2019). Secularism and securitization: The imaginary threat of religious minorities in Canadian public spaces. Journal of Beliefs & Values 40(3), 303-320 https://doi.org/10.1080/13617672.2019.1600341

Swiss Security Network (2017) National Action Plan to Prevent and Counter Radicalisation and Violent Extremism. https://bit.ly/2QuX6nr

Thoilliez, B. (2019). Vindicación de la escuela como espacio para el desarrollo de experiencias democráticas: aproximación conceptual a las prácticas morales de reconocimiento y respeto. Educacion XX1, 22(1), 295-314, https://doi.org/10.5944/educXX1.21657

Veiligheid van de staat. Vei Sûrete de l’Etat (2018) Le Salafisme en Belgique. Mécanismes et réalité. https://bit.ly/30Gvdw5

Viejo, C., Gómez-López, M. & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2019). Construyendo la identidad europea: una mirada a las actitudes juveniles y al papel de la educación. Revista Psicología Educativa, 25(1), 49-58. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2018a19

Villalobos-Carrasco, C., Álvarez-Valdivia, I. & Vaquera, E. (2017). Amistades co-étnicas e inter-étnicas en la adolescencia: Diferencias en calidad, conflicto y resolución de problemas. Educación XX1, 20(1), 99-120, https://doi.org/10.5944/educXX1.11894

Vrumo, G., Lamllari, B. & Papa, A. (2015). Religious Radicalization and Violent Extremism in Albania. https://cutt.ly/xkMpKbF

Walker, C. & Cawley, O. (2020). The juridification of the Uk´s Counter Terrorism Prevent Policy. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 1-6 https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2020.1727098

Contact address: Arantxa Azqueta, Universidad Internacional de La Rioja, Facultad de Educación, Departamento de Teoría e Historia de la Educación. Avda de la Paz 137, CP,26006, Logroño. E-mail: arantxa.azqueta@unir.net