What do parents think about cyberbullying?: A systematic review of qualitative studies1

¿Qué piensan los padres sobre el ciberacoso?: Una revisión sistemática de estudios cualitativos

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2022-397-541

Elizabeth Pardo-González

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3096-9539

Sidclay B. Souza

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3727-3793

Universidad Católica del Maule (Chile)

Abstract

Cyberbullying is a psychosocial phenomenon that generates harmful consequences for children and adolescents and family involvement is essential to address it. The objective of this review is to analyze the research findings of parents’ and caregivers’ perspectives on cyberbullying. The search was carried out in the Scopus, Web of Science, PsycArticles and EBSCO databases using the PRISMA statement for systematic reviews and meta-analyses, initially yielding 419 articles, from which 12 were selected. The characteristics of the research were analyzed and the themes of the main findings were identified and grouped based on the principles of thematic analysis. The results indicate that most of the studies were conducted in North American and European countries and involved a higher percentage of women. The studies reviewed provide valuable information on parents’ knowledge of different aspects of the problem, such as the existing gap in the knowledge and use of Information and Communication Technologies by adults and children and adolescents. The parents’ accounts also focus on parental strategies for the prevention and intervention of cyberbullying, their children’s motives for getting involved in these situations, and the barriers to seeking help from children and adolescents in the face of this problem. Their opinions also highlight the need for parents and caregivers to receive support to understand and address this phenomenon. In addition, suggestions for future research presented in the analyzed articles were identified, emphasizing the need to continue carrying out studies that incorporate parents and other family members as participants, since they are key actors in the prevention and intervention of cyberbullying in children and adolescents.

Keywords: cyberbullying, parents, caregivers, qualitative research, systematic review.

Resumen

El ciberacoso es un fenómeno psicosocial que genera consecuencias perjudiciales para niños, niñas y adolescentes y para su abordaje es esencial la participación de la familia. El objetivo de esta revisión es analizar los hallazgos de las investigaciones de las perspectivas de progenitores y cuidadores sobre el ciberacoso. Se utilizó la declaración PRISMA para revisiones sistemáticas y meta-análisis y la búsqueda se desarrolló en las bases de datos Scopus, Web of Science, PsycArticles y EBSCO, arrojando inicialmente 419 artículos, de los cuales se seleccionaron 12. Se analizaron las características de las investigaciones y se identificaron y agruparon los temas de los principales hallazgos en base a los principios del análisis temático. Los resultados indican que la mayoría de los estudios se realizaron en países norteamericanos y europeos y contaron con la participación de un porcentaje mayor de mujeres. Los estudios revisados proporcionan información valiosa que da cuenta del conocimiento de los progenitores sobre distintos aspectos del problema, como la brecha existente en el conocimiento y uso de las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación de los adultos y los niños, niñas y adolescentes. Los relatos de los progenitores también se centran en las estrategias parentales para la prevención e intervención del ciberacoso, los motivos de sus hijos/hijas para involucrarse en estas situaciones y las barreras para la búsqueda de ayuda de niños, niñas y adolescentes ante este problema. Sus opiniones también destacan la necesidad de que los progenitores y cuidadores reciban apoyo para comprender y abordar este fenómeno. Adicionalmente se identificaron las sugerencias para futuras investigaciones presentadas en los artículos analizados, donde se enfatiza la necesidad de continuar realizando estudios que incorporen a los progenitores y otros familiares como participantes, ya que son actores clave en la prevención e intervención del ciberacoso en niños, niñas y adolescentes.

Palabras clave: ciberacoso, progenitores, cuidadores, investigación cualitativa, revisión sistemática.

Introduction

The development of information and communication technologies (ICT) has provided beneficial tools associated with learning, communication, entertainment and prevention of risk behaviors for children and young people (Plaza de la Hoz, 2018; Xiao & Hu, 2019). However, it has also favored the emergence of phenomena such as cyberbullying generating harmful consequences that are difficult to cope with and repair (Soriano et al., 2019).

Cyberbullying is defined as an aggressive and intentional act, carried out by an individual or group, through electronic forms of contact against a victim who does not easily defend himself (Mallmann et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2008). Additionally, the existence of three possible roles that can be adopted by those involved is proposed: harasser, victim and witness (Garaigordobil, 2015). The characteristics of the cyber world facilitate not only the participation in this phenomenon but also enables fuzzy boundaries to exist in the involvement in cyberbullying, which could give rise to the overlapping of roles (Mishna et al., 2012), where victims and witnesses could become aggressors and vice versa (Barlińska et al., 2013; Ferreira et al., 2016; Souza et al., 2018).

The prevalence of cyberbullying worldwide has shown variability, associated with the particularities of the investigated sample, contextual differences and the characteristics of the measurement instruments (Kowalski, et al., 2019). A panoramic review incorporating studies from North America and Europe found that there is a higher prevalence in Canada (23.8%) and China (23%) and lower in Australia (5%) and Sweden (5.2%) (Brochado et al., 2016). In addition, in a review of studies carried out in Latin American countries, higher figures of cybervictimization were found in Brazil (8.4% - 58%) and Argentina (14% - 44.2%) and the lowest figures were presented in Peru (11.9%) and Bolivia (11% - 16%) (Garaigordobil et al., 2018). In the aforementioned reviews, the authors covered in their search strategy a time range from 2004 to 2018 and did not report results of studies that incorporated parents, key actors in the prevention and intervention of this phenomenon (Yot-Domínguez et al., 2020).

Several factors are related to cyberbullying including protective factors such as perceived safety in the environment, positive experiences at school, school and social support, family cohesion, authoritative parental style and parental supervision of ICT use (Buelga et al., 2016; Hong et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2018; Zurcher et al., 2018). On the other hand, having suffered bullying, greater use of social networks, low level of bonding with teachers, poor relationships between peers, dysfunctional family relationships, an authoritarian parental style and parental abuse are configured as risk factors (Duarte et al., 2018; Hong et al, 2018; Zsila et al, 2018; Zurcher et al, 2018).

A large part of these factors is associated with family relationships and the parental role, whose action can influence the reduction of exposure to online risks, mainly through the control of internet access, education and prevention strategies. However, this is a challenge for parents and caregivers, especially for those who do not know well the devices and platforms used by children and adolescents (Cassidy et al., 2012; Marín et al., 2019). Among the parental strategies to prevent their children’s participation in cyberbullying is the control of ICT use, however, this action has shown a low impact on the prevention of cyberbullying, since a controlling parental style and inconsistent mediation regarding internet use are associated with greater participation in cyberbullying (Elsaesser et al., 2017; Katz et al., 2019). In addition, collaborative practices, such as mediation, have shown greater effectiveness (Elsaesser et al., 2017).

The role of parents is important in the prevention of cyberbullying from the perspective of teachers and adolescents, highlighting parental supervision and control in the use of ICTs, dialogue with children, strengthening relationships, connection with school and awareness of online risks (Cassidy et al., 2018; Marín et al., 2019). There have been systematic reviews based on quantitative studies on family variables associated with cyberbullying, as risk or protective factors (Elsaesser et al., 2017; Machimbarrena et al., 2019), highlighting important contributions on the role of the family in cyberbullying. These investigations have not incorporated qualitative studies, which allow in-depth exploration of people’s perspectives by enabling them to relate their experiences and opinions in their own words (Harcourt et al., 2014; Smith, 2019; Van Manen, 2016). This allows to gather specific information from the perspective of those involved and other relevant actors, significant data for the understanding, intervention and prevention of phenomena such as cyberbullying (Vandebosch & Green, 2019).

In light of the above, the present study analyzes findings from qualitative research that has examined parents’ and caregivers’ perspectives on cyberbullying. It seeks to answer the following questions: (1) What are the characteristics of the studies about parents’ and caregivers’ perspectives on cyberbullying?; (2) What do parents and caregivers know about cyberbullying in children and adolescents?; (3) What are the perspectives and experiences of parents and caregivers regarding cyberbullying prevention and intervention?; (4) What are the suggestions for future research proposed in the studies?

Method

Search and selection strategy

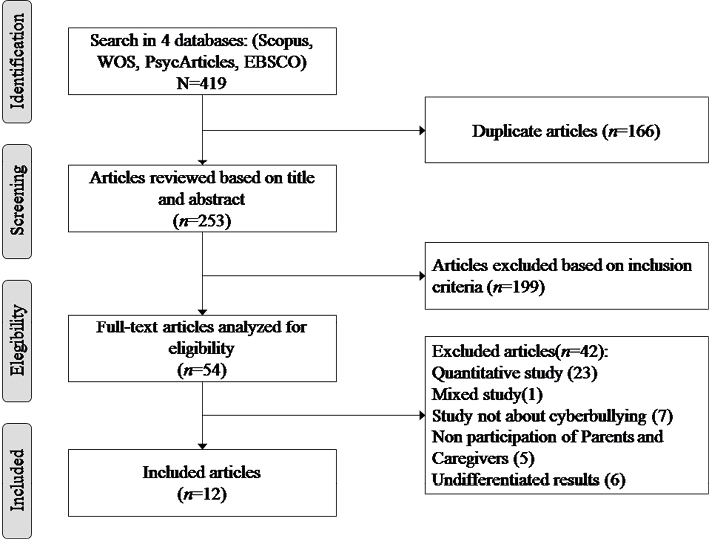

The review followed the PRISMA statement guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Moher et al., 2009). A systematic review of the literature published from January 2004 to December 2020 on parent and caregiver perspectives on cyberbullying was conducted. The choice to consider publications in this time range was based on the fact that the first studies on cyberbullying were published in 2004 (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2004; Zych et al., 2015). At first, Boolean terms and their combination were established, defining the following search strategy: (cyberbullying OR cyber-bullying OR online-bullying) AND (parents OR caregivers) AND (perceptions OR beliefs OR conceptualization OR knowledge OR concerns OR views OR understanding). This combination was used to run the search in four electronic databases: Web of Science, Scopus, PsycArticles (APA) and EBSCO. These databases were selected because of their multidisciplinary profile and their peer review process, which evidences the quality of scientific publications and because they contain the majority of journals at the international level (Martín-Martín et al., 2021). The search was performed by two researchers, using titles, abstracts and keywords.

Inclusion criteria

1) empirical studies published in scientific journals; 2) published from January 2004 to December 2020; 3) studies focused on investigating parents’ and caregivers’ perspectives on cyberbullying in children or adolescents; 4) use of the qualitative methodology. The option of incorporating only qualitative studies is based on the fact that these can provide a greater understanding of parents’ perceptions, opinions, and experiences about cyberbullying (Ghazali et al., 2017; Smith, 2019) and consider participants’ voices in describing and interpreting the problem (Creswell & Poth, 2016).

Exclusion criteria

1) studies that presented the perspectives of parents on cyberbullying and school bullying in an undifferentiated manner; 2) studies that presented the perspectives of parents, adolescents, teachers or others involved in an undifferentiated manner; 3) studies that only quantitatively explored parents’ knowledge of cyberbullying. It is important to clarify that bullying is recognized as a phenomenon associated with cyberbullying, however, the objective of the present review focused specifically on delving into the phenomenon of cyberbullying.

Search and selection process

The search yielded a total of 419 articles. Duplicate articles (n=166) were identified, the abstracts of the remaining articles (n=253) were reviewed and 199 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Fifty-four articles were selected for full-text analysis and 12 studies were finally included in the review (see Figure I).

FIGURE I. Study selection flow according to the PRISMA Statement.

Source: Own elaboration.

Data analysis

Based on the principles of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Thomas & Harden, 2008), as applied in previous studies (Macaulay et al., 2018), the present systematic review used this technique to identify and group the themes of the main findings to represent common patterns across all included studies (Belotto, 2018; Thomas & Harden, 2008). This analytical procedure provided a synthesis of the results.

Results

Characteristics of the studies included in the review

Five studies were conducted in the United States and one in Canada. The others were conducted in different countries, which were located in Australia, Belgium, England, Turkey and Croatia. One of the studies did not report the country where it was conducted. Regarding the participants, three of the studies included only parents and the others included different members of the community (students, teachers and other school professionals, police and pediatricians). It should be noted that only one study included guardians (caregivers or other family members). Therefore, in describing the results, it will refer primarily to parents. The number of participating parents ranged from 10 to 65. Regarding their individual characteristics, only six of the studies reported age, ranging from 25 to 67 years. Regarding gender, eight studies provided the percentage of men and women, with a higher proportion of women, and in two studies, all participants were mothers. Regarding data collection, seven studies conducted focus groups, four used semi-structured interviews and one study applied a questionnaire with open-ended questions (see Table I).

TABLE I. Description of studies on parents’ and caregivers’ perspectives on cyberbullying in children and adolescents included in the systematic review (n=12)

|

Authors (year) |

Country |

Objectives |

Participants (n) |

Data collection |

|

1. Bolenbaugh et al. (2020) |

United States |

To explore how parents perceive technology use and their sons/daughters’ involvement in cyberbullying as a function of gender. |

Parents (48) |

Focus groups |

|

2. Broll (2016) |

Canada |

To examine the types of resources held by parents, schools and police, their position within the cyberbullying safety net, how safety is worked out and the constraints experienced by each group |

Parents (14) Educators (12) Police (12) |

In-depth interview |

|

3. Compton et al. (2014) |

Australia |

To examine the views of teachers, parents, and students on the motivation of students who engage in cyberbullying and bullying. To explore their understanding of the definition of both phenomena. |

Parents (12) Students (12) Teachers (11) |

Focus groups |

|

4. DeSmet et al. (2016) |

Belgium |

To explore specific parental behavior in the context of cyberbullying using scenarios. |

Parents (48) |

Questionnaire with open-ended questions in phase 2 of the study. |

|

5. Helfrich et al. (2020) |

Not reported |

To identify parental protection strategies to prevent their sons/daughters’ involvement in cyberbullying and increase young people’s ability to cope with cyberbullying |

Parents (26) |

Focus groups |

|

6. McHugh & Howard (2017) |

United States |

To explore perceptions of cyberbullying of parents of athletes with disabilities. |

Parents (10) |

In-depth and semi-structured interview |

|

7. Mehari et al. (2018) |

United States |

To explore precautionary norms for cyberbullying prevention in youth, parents, and pediatricians and identify barriers to prevention |

Parents (15) Adolescents (29) Pediatricians (13) |

Semi-structured interview |

|

8. Midamba & Moreno (2019) |

United States |

To examine the similarities and differences between how parents and adolescents view cyberbullying and the role of parents in addressing this phenomenon. |

Parents (65) Adolescents (66) |

Focus groups |

|

9. Monks et al. (2016) |

England |

To examine the perceptions of parents/guardians and school staff on cyberbullying among elementary school students. |

Parents /tutors (21) Teachers (20) |

Focus groups |

|

10 Toraman & Usta (2018) |

Turkey |

To determine the opinions of high school students and their parents about Internet use and problems occurring on the Internet. |

Parents (12) Students (24) |

Semi-structured interview |

|

11. Vejmelka et al. (2020) |

Croatia |

To determine patterns of Internet use and Internet addiction in children and to examine cyberbullying |

Parents (20) Children (5) Teachers and caregivers (13) |

Focus groups in phase 2 of the study. |

|

12. Young & Tully (2019) |

United States |

To explore parents’ reactions to cyberbullying scenarios and how their responses affirm or contradict guidance on handling their sons’/daughters’ involvement in cyberbullying. To compare their responses with those of their sons/daughters. |

Parents (48) Adolescents (17) |

Focus groups |

Source: Own elaboration.

Study findings

The studies provided important information about parents’ perspectives on cyberbullying, demonstrating that they are aware of the phenomenon and their opinions are analogous to those of other parents. The topics were grouped as follows: a) Knowledge and use of ICTs by children, adolescents and parents; b) Parental strategies for the prevention of cyberbullying; c) Parental intervention in cases of cyberbullying; d) Motives of children and adolescents for getting involved in cyberbullying situations; e) Barriers to help-seeking by children and adolescents in cyberbullying situations. It is important to note that the differentiation between roles was considered based on the information provided in the studies analyzed. These results are presented in Table II.

TABLE II. Contributions of the included articles to the topics generated in the thematic analysis.

|

Autores (año) |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

1. Bolenbaugh et al. (2020) |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

2. Broll (2016) |

X |

||||

|

3. Compton et al. (2014) |

X |

||||

|

4. DeSmet et al. (2016) |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

5. Helfrich et al. (2020) |

X |

||||

|

6. McHugh & Howard (2017) |

X |

||||

|

7. Mehari et al. (2018) |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

8. Midamba & Moreno (2019) |

X |

||||

|

9. Monks et al. (2016) |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

10. Toraman & Usta (2018) |

X |

||||

|

11. Vejmelka et al. (2020) |

X |

||||

|

12. Young & Tully (2019) |

X |

X |

X |

Note: 1= Knowledge and use of ICTs by children, adolescents and parents; 2 = Parental strategies for the prevention of cyberbullying; 3 = Parental intervention in cases of cyberbullying; 4 = Motives of children and adolescents for getting involved in cyberbullying situations; 5 = Barriers to help-seeking by children and adolescents in cyberbullying situations. The contribution of the articles to each topic is marked with X.

Knowledge and use of ICTs by children, adolescents and parents

Parents stated that they think their children use technology excessively (Bolenbaugh et al., 2020), also referring that children and adolescents have greater skills in computer literacy and access to technology, perceiving a generational gap in the competencies associated with ICTs (Monks et al., 2016). Parents noted that their children generally know more about technology and, according to their perception, the most common barrier to cyberbullying prevention was parents’ low ICT competence (Mehari et al., 2018).

Parental strategies for the prevention of cyberbullying

The strategies for preventing cyberbullying and cybervictimization noted by parents are communicating and monitoring their children’s online activity, maintaining an open and constant line of communication with them and supervising or restricting the content to which they have access. In addition, parents indicated that another strategy used was to encourage positive behavior from cyberbullying witnesses and to build trust in their children (Helfrich et al., 2020). Monitoring and supervision of ICT use were strategies that consistently recurred in the responses of parents and guardians, along with the use of rules and restrictions (Mehari et al., 2018; Monks et al., 2016). Parents prioritize rules as an element of prevention, recognizing that their children require constant monitoring (Young & Tully, 2019), especially when they have a disability since this would make them more vulnerable to cybervictimization (McHugh & Howard, 2017). Another interesting aspect of the parents’ account is that the responsibility for monitoring is often interfered with by the parental burden on them, which, in conjunction with the lack of knowledge about cyberbullying, leads them to experience feelings of frustration (Bolenbaugh et al., 2020).

Parental intervention in cases of cyberbullying

Parents stated that they should play a protective role and help their children to escape cyberbullying when they are victimized and, in the case that they were aggressors, give sanctions. In addition to the sanctions as an immediate solution, they recognize that it is necessary to understand how their children relate to others on social networks in order to become effective allies in addressing the problem (Bolenbaugh et at., 2020). In the same vein, Young and Tully (2018) explored parents’ reactions to hypothetical scenarios where they envisioned their children in the roles of cyberaggressor, cybervictim, or cyberwitness. In the first place, when the parents imagined their children as victims, they showed an attitude aimed at protecting them, but this also depended on who was involved and the context of the aggression. Secondly, conceiving their children as aggressors generated great concern for them since this could indicate that their children were moving away from the values developed at home. In addition, the majority indicated that they would apply for a sanction (give punishment), but the need to have an open conversation was recognized. Thirdly, visualizing their children as witnesses, parents indicated that they could advise them to express support for the victim, but not to confront the aggressor, balancing concern for their children’s safety with guidance to support others.

Regarding support needs, parents indicate that resources, guidance and strategies focused on the prevention and intervention of cyberbullying are required (Midamba et al., 2019) since, according to them, reducing the prevalence of this phenomenon is the only way to protect their children (DeSmet et al., 2016). Moreover, parents can also take other types of measures when their children are cybervictims, such as reporting the situation on the social networks involved, taking legal action (Toraman & Usta, 2018) or seeking professional help from psychologists, pediatricians or other professionals (Helfrich et al., 2020). On the other hand, Broll’s (2014) study indicated that parents of adolescents who had been cybervictims or cyberaggressors reported their desire to deal with cyberbullying on their own without the help of other groups. This is because in past experiences they were disappointed by the responses of other people responsible for the safety of their children, such as teachers or police officers, which led them to independently seek solutions or discuss cyberbullying incidents with the parents of those involved.

Motives of children and adolescents for getting involved in cyberbullying situations

Among the reasons that drive children and adolescents to engage in cyberbullying as aggressors, parents mention anonymity, the use of technology, the avoidance of retaliation (Compton et al., 2014), previous participation in bullying situations (Monks et al., 2016) and the normalization of violent behaviors through the internet (Vejmelka et al., 2020). On the other hand, they have the perception that girls and adolescents tend to engage more in cyberbullying in the role of aggressor and normalize certain behaviors, which can also configure a motive to be cybervictimized as well (Bolenbaugh et at., 2020; Vejmelka et al., 2020).

Barriers to help-seeking by children in situations of cyberbullying

Parents recognize the importance of cybervictims being able to seek external help, either by reporting cyberbullying situations at school or by informing their family (Mehari et al., 2018). In the same vein, they refer that it is necessary to educate their children regarding the duty of not ignoring cyberbullying when they witness it, providing containment to their peers, taking positive action and informing adults (DeSmet et al., 2016). Regarding potential barriers to cybervictims deciding to seek help or report their cyberbullying experiences, parents suggested fear of repercussions (Mehari et al., 2018), the perception of cyberbullying as normal, and the idea that parental intervention is not necessary (Young & Tully, 2019).

Suggestions for future research presented in the reviewed studies

The studies suggest that future research could incorporate parents from different ethnic backgrounds and socioeconomic levels (Bolenbaugh et al., 2020), highlighting the importance of developing cross-cultural research (DeSmet et al., 2016). Larger-scale studies with parents and guardians, primary and secondary school students, and educational establishment staff are suggested, exploring their perceptions of cyberbullying, allowing everyone to participate in the dialogue and planning of cyberbullying prevention and intervention strategies (Cassidy et al., 2018; Compton et al., 2014; Helfrich et al., 2020; Monks et al., 2016; Toraman & Usta, 2018). There are other important actors in the intervention, detection or prevention of cyberbullying, highlighting primary health care professionals, with whom it is suggested to carry out future research exploring larger samples and diverse contexts (Mehari et al., 2018). On the other hand, there is a need to explore the cyberbullying safety net, of which institutional members in charge of safety, parents and staff of educational establishments can form part. Future studies should also consider informal and criminal responses to cyberbullying (Broll, 2014).

Suggestions also point to future studies incorporating among their variables the motives of children and youth who perpetrate cyberbullying (Compton et al., 2014) and parental supervision and support as a protective factor against the risks of the cyber world (Vekmelka et al., 2020). Moreover, research presenting hypothetical scenarios to participants could use gender-neutral pronouns, to avoid the gender variable influencing the responses of parents or other participants (Bolenbaugh et al., 2020). Finally, it is also suggested to develop future research on cyberbullying in adolescents with intellectual disabilities incorporating bullying perpetrated by peers, teachers, and even siblings. In addition, it is important to evaluate the effectiveness of support using infographics and other types of visual support to help children and adolescents recognize when they are being cyberbullied and an adult needs to be notified (McHugh & Howard, 2017).

Discussion and conclusions

This study aimed to systematize qualitative research on the perspectives of parents and caregivers about cyberbullying. After searching the Scopus, Web of Science, PsycArticles and EBSCO databases and analyzing the 12 selected articles, it was found that only one of the studies included other family members or guardians in addition to parents. This information evidences the need to conduct studies with this population. This is needed since caregivers and guardians have fundamental role in the prevention and intervention of this phenomenon. Moreover, the results indicate that parents have perspectives and opinions about different important aspects of cyberbullying, highlighting knowledge and use of ICTs, parental strategies for prevention and intervention, children’s motives for involvement in cyberbullying situations, and barriers to seeking help.

The findings of the reviewed studies show that parents are aware of the phenomenon and their opinions are similar to those of other parents. One element present in most of their accounts is the identification of a generation gap in terms of ICT use. Parents and guardians perceive that they are at a disadvantage, arguing that their children are more tech-savvy (Bolenbaugh et al., 2020; Mehari et al., 2018; Monks et al., 2016). This can make it difficult for parents to be aware of their children’s online activities, a situation that constitutes a risk factor (Barlett & Fennel, 2018). Preventing cyberbullying is a complex task for parents and the characteristics of the cyber world make this task difficult, as it constantly offers new platforms, applications and ways of communicating online that they do not know or understand, which can hinder supervision (Elsaesser et al., 2017; Goldstein, 2015).

Parents report that they use various strategies to prevent and intervene in cyberbullying situations. In terms of prevention, they show a preference for monitoring and supervising their children’s online activity and maintaining open and constant communication with them (Helfrich et al., 2020; Mehari et al., 2018; Monks et al., 2016; Young & Tully, 2019). The above result is consistent with the literature, where it is evident that parents tend to use two types of prevention strategies. The first type is restrictive ones that include monitoring or limiting the use of the Internet or technological devices and the second one collaborative strategies, where mediation, education, communication, strengthening family relationships and linking school and family stand out (Cassidy et al., 2018; De la Caba et al., 2013; Elsaesser et al., 2017). At this point, it is important to consider that parents can control and limit the use of technology and online activity of their children, however, these measures can affect the relationship with them, making it distant (Baldry et al., 2019). In the same line, parental monitoring has great influence as a protective factor for involvement in risky behaviors on the Internet, since most cyberbullying situations occur when children and adolescents are at home (Buelga et al., 2016).

When their children are victims of cyberbullying, parents recognize that they need to protect and support them and to do so they need to understand their interactions on social networks and other virtual platforms (Bolenbaugh et at., 2020; Midamba et al., 2019). Parents report using sanctioning actions as immediate solutions, but in the long term, they prioritize positive bonding (Cassidy et al., 2012). It is important to have positive and open communication between parents and their children (Moreno et al., 2019) because when communication is scarce and conflictive, they tend to avoid sharing with their parents the difficult circumstances they experience, situation that causes parents to be unaware when their children are involved in cyberbullying (Buelga et al., 2016). It is relevant to point out that parents who participated in the studies did not report information about overlapping of roles, since different opinions and possible actions emerged in the case of their children being aggressors, victims or witnesses. However, the studies did not explore their perspectives on possible situations in which their children were involved in cyberbullying from more than one role (Barlińska et al., 2013; Ferreira et al., 2016; Mishna et al., 2012).

On the other hand, it has been evidenced that parental control through the establishment of restrictions and supervision configures a protective factor against cyberbullying (Álvarez-García et al., 2019). When their children are victims of cyberbullying, parents sometimes also take other types of measures, such as reporting the situation on the social networks involved, establishing legal actions (Toraman & Usta, 2018) or seeking help from professionals (Helfrich et al., 2020). However, Broll’s (2014) research revealed that parents of adolescents who had been victims or aggressors might also decide to deal with cyberbullying on their own without seeking help, due to past negative experiences, where they have not received support. Parents play a central role in preventing and intervening in cyberbullying situations, therefore, they should be encouraged to be aware of and show interest in their children’s online activities (Cerna et al., 2016; Moodley & Singh, 2016). In addition, they raised the need for support in understanding the risks of the cyber world and guidance on the most effective strategies to deal with cyberbullying by implementing programs that address that need (Hutson et al., 2018).

Among the motives of children and adolescents for engaging in cyberbullying, parents and guardians mention anonymity, the impact of technology, avoiding retaliation (Compton et al., 2014) and previous experiences of bullying (Monks et al., 2016). Other motives include escape from the real world and compensation for lack of social skills, desire for revenge, and intent to harm, variables that have been extensively studied in conjunction with cyberbullying (Navarro et al., 2018; Tanrikulu & Erdur-Baker, 2019). Parents’ knowledge of their children’s motivations for engaging in cyberbullying is extensive and is consistent with the literature, which indicates that adolescents’ motives for engaging in cyberbullying may be power, anonymity, boredom, or access to technology (Yot-Dominguez & Fernandez, 2020).

Regarding seeking help from children and adolescents, parents identify fear of repercussions in the case of victims (Mehari et al., 2018) and the normalization of cyberbullying as barriers (Young & Tully, 2019). Consistent with this, the literature indicates that perceived harm in cyberbullying and active mediation increases the likelihood of help-seeking (Cerna et al., 2016). Moreover, adolescents show a preference for addressing cyberbullying on their own, and justifications for this decision include ignorance or underestimation of the negative consequences of cyberbullying and fear of adult overreactions, including restriction of internet access (Gao et al., 2016). Adolescents often report cyberbullying to their peers rather than to adults, and many even prefer not to report it. To counteract this situation, adolescents should be educated about the importance of their role as witnesses and parents and other significant adults should be educated about how to support the involved children (Brandau et al., 2019; DeSmet et al., 2016).

Regarding the limitations of this review, it is important to mention that we did not incorporate studies included in books or unpublished research (grey literature) and did not include Spanish-language databases in the search, sources that could have provided more information. The present review focused only on parents’ and caregivers’ perceptions of cyberbullying and a limitation derived from this decision is the exclusion of articles that dealt only with traditional bullying considering that both phenomena are widely related. Additionally, only one of the studies of this review included caregivers, so it was not possible to analyze their perspectives on the phenomenon in depth.

Based on what was reported in the analyzed studies, it is suggested that future research on cyberbullying with parents be conducted considering the various sociodemographic factors, such as socioeconomic levels, other ethnic backgrounds, and the individual characteristics of the children, such as intellectual ability or sexual and/or gender orientation. It is also suggested that future research that presents participants with hypothetical scenarios or cases employ gender-neutral pronouns. The perspectives of parents, caregivers, and others involved on role overlap in cyberbullying need to be studied. It is suggested to explore parents’ and caregivers’ knowledge, experiences, coping strategies, and intervention measures in both cyberbullying and traditional bullying. It is necessary to investigate the role of the different actors involved in the phenomenon, including children, parents, caregivers, teachers and other members of educational establishments, primary health care professionals and professionals in the area of public safety. Finally, it is essential to incorporate families in cyberbullying prevention and intervention programs, so future studies should consider their experiences, opinions and needs.

In conclusion, the main findings of the studies included in this review address the knowledge and use of ICTs by parents and their children, parental strategies for prevention and intervention of the phenomenon, their children’s motives for engaging in cyberbullying, and barriers to seeking help. These results provide guidelines for an educational-preventive action that promotes parental knowledge of their children’s new forms of social interaction and effective intervention. The family plays a fundamental role in the prevention and intervention of cyberbullying, so it is necessary to continue carrying out research involving these actors. Therefore, it is important to know their opinions regarding the phenomenon, how they are intervening and their needs and suggestions so that they can also promote the healthy coexistence of their children with their peers in a face-to-face and online context.

References

Álvarez-García, D., Núñez, J. C., González-Castro, P., Rodríguez, C., & Cerezo, R. (2019). The effect of parental control on cyber-victimization in adolescence: the mediating role of impulsivity and high-risk behaviors. Frontiers in psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01159

Baldry, A. C., Sorrentino, A., & Farrington, D. P. (2019). Cyberbullying and cybervictimization versus parental supervision, monitoring and control of adolescents’ online activities. Children and Youth Services Review, 96, 302-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.11.058

Barlett, C. P., & Fennel, M. (2018). Examining the relation between parental ignorance and youths’ cyberbullying perpetration. Psychology of popular media culture, 7(4), 547-560. http://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000139

Barlińska, J., Szuster, A., & Winiewski, M. (2013). Cyberbullying among adolescent bystanders: Role of the communication medium, form of violence, and empathy. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 23(1), 37-51. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2137

Belotto, M. J. (2018). Data analysis methods for qualitative research: Managing the challenges of coding, interrater reliability, and thematic analysis. Qualitative Report, 23(11), 2622-2633. Retrieved from https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol23/iss11/2

Beyazit, U., Şimşek, Ş., & Ayhan, A. B. (2017). An examination of the predictive factors of cyberbullying in adolescents. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 45(9), 1511-1522. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.6267

*Bolenbaugh, M., Foley-Nicpon, M., Young, R., Tully, M., Grunewald, N., & Ramirez, M. (2020). Parental perceptions of gender differences in child technology use and cyberbullying. Psychology in the Schools, 57(11), 1657-1679. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22430

Brandau, M. S., Sarzosa, A., & Schmillen, H. (2019). Who, When, and How: A Comprehensive Literature Review of Adolescent Reporting of Cyberbullying. Journal of General Nursing and Community Health, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3813039

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brochado, S., Soares, S., & Fraga, S. (2016). A scoping review on studies of cyberbullying prevalence among adolescents. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 18(5), 523-531. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016641668

*Broll, R. (2016). Collaborative responses to cyberbullying: preventing and responding to cyberbullying through nodes and clusters. Policing and society, 26(7), 735-752. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2014.989154

Buelga S., Martínez-Ferrer B., Musitu G. (2016) Family Relationships and Cyberbullying. En: R. Navarro, S. Yubero, & E. Larrañaga (Eds.), Cyberbullying Across the Globe (pp. 99-114). Springer.

Cassidy, W., Brown, K., & Jackson, M. (2012). “Making kind cool”: Parents’ suggestions for preventing cyber bullying and fostering cyber kindness. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 46(4), 415-436. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.46.4.f

Cassidy, W., Faucher, C., & Jackson, M. (2018). What Parents Can Do to Prevent Cyberbullying: Students’ and Educators’ Perspectives. Social Sciences, 7(12), 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7120251

Cerna, A., Machackova, H., & Dedkova, L. (2016). Whom to trust: The role of mediation and perceived harm in support seeking by cyberbullying victims. Children & Society, 30(4), 265-277. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12136

*Compton, L., Campbell, M. A., & Mergler, A. (2014). Teacher, parent and student perceptions of the motives of cyberbullies. Social Psychology of Education, 17(3), 383-400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9254-x

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage publications.

De la Caba-Collado, M. A., & López, R. (2013). Las respuestas de los padres ante situaciones hipotéticas de agresión a sus hijos en el contexto escolar. Revista de Educación, 236-260. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2013- EXT-248

*DeSmet, A., Van Cleemput, K., Bastiaensens, S., Poels, K., Vandebosch, H., Malliet, S., Verloigne, M., Vanwolleghem, G., Mertens, L., Cardon, G., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2016). Bridging behavior science and gaming theory: Using the Intervention Mapping Protocol to design a serious game against cyberbullying. Computers in Human Behavior, 56, 337-351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.039

Duarte, C., Pittman, S., Thorsen, M., Cunningham, R., & Ranney, M. (2018). Correlation of Minority Status, Cyberbullying, and Mental Health: A Cross-Sectional Study of 1031 Adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 11(1), 39-48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-018-0201-4

Elsaesser, C., Russell, B., Ohannessian, C. M., & Patton, D. (2017). Parenting in a digital age: A review of parents’ role in preventing adolescent cyberbullying. Aggression and violent behavior, 35, 62-72. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.06.004

Ferreira, P. C., Simão, A. V., Ferreira, A., Souza, S., & Francisco, S. (2016). Student bystander behavior and cultural issues in cyberbullying: When actions speak louder than words. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 301-311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.059

Gao, M., Zhao, X., & McJunkin, M. (2016). Adolescents’ Experiences of Cyberbullying: Gender, Age and Reasons for Not Reporting to Adults. International Journal of Cyber Behavior, Psychology and Learning (IJCBPL), 6(4), 13-27. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJCBPL.2016100102

Garaigordobil, M. (2015). Psychometric Properties of the Cyberbullying Test, a Screening Instrument to Measure Cybervictimization, Cyberaggression, and Cyberobservation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(23), 3556–3576. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515600165

Garaigordobil, M., Mollo-Torrico, J. P., & Larrain, E. (2018). Prevalencia de Bullying y Cyberbullying en Latinoamérica: una revisión. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología, 11(3), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.33881/2027-1786.rip.11301

Ghazali, A., Abdullah, H., Omar, S., Ahmad, A., Samah, A., Ramli, S., & Shaffril, H. (2017). Malaysian Youth Perception on Cyberbullying: The Qualitative Perspective. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 7(4), 87-98. http://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i4/2782

Goldstein, S. E. (2015). Parental regulation of online behavior and cyber aggression: Adolescents’ experiences and perspectives. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2015-4-2

Harcourt, S., Jasperse, M., & Green, V. (2014). “We were sad and we were angry”: A systematic review of parents’ perspectives on bullying. Child & Youth Care Forum, 43(3), 373-391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-014-9243-4

*Helfrich, E. L., Doty, J. L., Su, Y. W., Yourell, J. L., & Gabrielli, J. (2020). Parental views on preventing and minimizing negative effects of cyberbullying. Children and Youth Services Review, 118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105377

Hong, J. S., Kim, D. H., Thornberg, R., Kang, J. H., & Morgan, J. T. (2018). Correlates of direct and indirect forms of cyberbullying victimization involving South Korean adolescents: An ecological perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 327-336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.06.010

Hutson, E., Kelly, S., & Militello, L. (2018). Systematic review of cyberbullying interventions for youth and parents with implications for evidence-based practice. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 15(1), 72-79. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12257

Katz, I., Lemish, D., Cohen, R., & Arden, A. (2019). When parents are inconsistent: Parenting style and adolescents’ involvement in cyberbullying. Journal of adolescence, 74, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.04.006

Kowalski, R. M., Limber, S. P., & McCord, A. (2019). A developmental approach to cyberbullying: Prevalence and protective factors. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 20-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.02.009

Macaulay, P. J., Betts, L. R., Stiller, J., & Kellezi, B. (2018). Perceptions and responses towards cyberbullying: A systematic review of teachers in the education system. Aggression and violent behavior, 43, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.08.004

Machimbarrena, J. M., González-Cabrera, J., & Garaigordobil, M. (2019). Variables familiares relacionadas con el bullying y el cyberbullying: Una revisión sistemática. Pensamiento Psicológico, 17(2), 37-56. https://doi.org/10.11e144/javerianacali.ppsi17-2.vfrb

Mallmann, C., de Macedo, C., & Zanatta, T. (2018). Cyberbullying and coping strategies in adolescents from Southern Brazil. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 21(1), 34-43. https://doi.org/10.14718/ACP.2018.21.1.2

Marín, A., Hoyos, O., & Sierra, A. (2019). Factores de riesgo y factores protectores relacionados con el ciberbullying entre adolescentes: una revisión sistemática. Papeles del psicólogo, 40(2), 109-124. https://doi.org/10.23923/pap.psicol2019.2899

Martín-Martín, A., Thelwall, M., Orduna-Malea, E., & López-Cózar, E. D. (2021). Google Scholar, Microsoft Academic, Scopus, Dimensions, Web of Science, and OpenCitations’ COCI: a multidisciplinary comparison of coverage via citations. Scientometrics, 126(1), 871-906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03690-4

*McHugh, M. C., & Howard, D. E. (2017). Friendship at any cost: parent perspectives on cyberbullying children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 10(4), 288-308. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2017.1299268

*Mehari, K. R., Moore, W., Waasdorp, T. E., Varney, O., Berg, K., & Leff, S. S. (2018). Cyberbullying prevention: Insight and recommendations from youths, parents, and paediatricians. Child: care, health and development, 44(4), 616-622. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12569

*Midamba, N., & Moreno, M. (2019). Differences in parent and adolescent views on cyberbullying in the US. Journal of children and media, 13(1), 106-115. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2018.1544159

Mishna, F., Khoury-Kassabri, M., Gadalla, T., & Daciuk, J. (2012). Risk factors for involvement in cyber bullying: Victims, bullies and bully–victims. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.08.032

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), 264-269. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

*Monks, C. P., Mahdavi, J., & Rix, K. (2016). The emergence of cyberbullying in childhood: Parent and teacher perspectives. Psicología Educativa, 22(1), 39-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pse.2016.02.002

Moodley, P., & Singh, R. J. (2016). Parental regulation of internet use: issues of control, censorship and cyberbullying. Mousaion, 34(2), 15-30.

Moreno–Ruiz, D., Martínez–Ferrer, B., & García–Bacete, F. (2019). Parenting styles, cyberaggression, and cybervictimization among adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 252-259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.031

Navarro, R., Larrañaga, E., & Yubero, S. (2018). Differences between preadolescent victims and non-victims of cyberbullying in cyber-relationship motives and coping strategies for handling problems with peers. Current Psychology, 37(1), 116-127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9495-2

Plaza de la Hoz, J. (2018). Ventajas y desventajas del uso adolescente de las TIC: visión de los estudiantes. Revista Complutense de Educación, 29(2), 491-508. https://doi.org/10.5209/rced.53428

Silva, Y. N., Hall, D. L., & Rich, C. (2018). BullyBlocker: toward an interdisciplinary approach to identify cyberbullying. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 8(18), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-018-0496-z

Smith, P. (2019). Research on Cyberbullying: Strengths and Limitations. En H. Vandebosch, & L. Green (Eds.), Narratives in Research and Interventions on Cyberbullying among Young People (pp. 9-27). Springer Nature.

Smith, P., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 49(4), 376-385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x

Soriano, E., Cala, V. C., & Bernal, C. (2019). Sociocultural and psychological factors affecting sexting: A transcultural study. Revista de Educación, (384), 175-197. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2019-384-407

Souza, S. B., Veiga Simão, A. M., Ferreira, A. I., & Ferreira, P. C. (2018). University students’ perceptions of campus climate, cyberbullying and cultural issues: implications for theory and practice. Studies in Higher Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1307818

Sudarsana, I. K, Yogantara, I. W., & Ekawati, N. W. (2019). Cyber Bullying Prevention And Handling Through Hindu Family Education. Jurnal Penjaminan Mutu, 5(2), 170-178.

Tanrikulu, I., & Erdur-Baker, Ö. (2019). Motives behind cyberbullying perpetration: a test of uses and gratifications theory. Journal of interpersonal violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518819882

Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC medical research methodology, 8(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

*Toraman, L., & Usta, E. (2018). A Qualitative Study on the Problems Encountered by Secondary School Students on the Net. Participatory Educational Research, 5(2), 80-94. https://doi.org/10.17275/per.18.13.5.2

Van Manen, M. (2016). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Routledge.

Vandebosch, H., & Green, L. (2019). Introduction. En H. Vandebosch, & L. Green (Eds.), Narratives in Research and Interventions on Cyberbullying among Young People (pp. 1-6). Springer Nature.

*Vejmelka, L., Matkovic, R., & Borkovic, D. K. (2020). Online at risk! Online activities of children in dormitories: experiences in a croatian county. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 11(4), 54-79. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs114202019938

Xiao, Y., & Hu, J. (2019). Regression analysis of ICT impact factors on early adolescents’ reading proficiency in five high-performing countries. Frontiers in psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01646

Yot-Domínguez, C., & Fernández, A. C. (2020). Las familias en la investigación sobre el ciberacoso. Edutec. Revista Electrónica De Tecnología Educativa, (73), 140-156. https://doi.org/10.21556/edutec.2020.73.1537

Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2004). Online aggressor/targets, aggressors, and targets: A comparison of associated youth characteristics. Journal of child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(7), 1308-1316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00328.x

*Young, R., & Tully, M. (2019). ‘Nobody wants the parents involved’: Social norms in parent and adolescent responses to cyberbullying. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(6), 856-872. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2018.1546838

Zsila, Á., Orosz, G., Király, O., Urbán, R., Ujhelyi, A., Jármi, É., …, & Demetrovics, Z. (2018). Psychoactive Substance Use and Problematic Internet Use as Predictors of Bullying and Cyberbullying Victimization. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16(2), 466-479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9809-0

Zurcher, J. D., Holmgren, H. G., Coyne, S. M., Barlett, C. P., & Yang, C. (2018). Parenting and cyberbullying across adolescence. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 21(5), 294-303. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0586

Zych, I., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Del Rey, R. (2015). Scientific research on bullying and cyberbullying: Where have we been and where are we going. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 24, 188-198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.015

Contact address: Sidclay B. Souza (Ph.D.), Departamento de Psicología, Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Católica del Maule. Av. San Miguel, CP 3605, Talca, Chile. E-mail: sbezerra@ucm.cl.

1 Acknowledgements: Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID) / Subdirección de Capital Humano / Beca de Doctorado Nacional - Folio 21201664.