Cyberbullying and suicidal behavior in adolescent students:

A systematic review

Cyberbullying y conducta suicida en alumnado adolescente: Una revisión sistemática

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2022-397-539

Sofia Buelga

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7434-4752

María-Jesús Cava

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7737-9424

David Moreno Ruiz

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1221-2097

Universidad de Valencia

Jessica Ortega-Barón

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8822-5906

Universidad Internacional de la Rioja

Abstract

The main purpose of this research was to carry out a systematic review of the most recent scientific literature on suicidal behavior in victims of cyberbullying. Five databases, Web of Science, Scopus, Psycinfo, Psycarticles and PubMed, were consulted to examine the research published between 2018 and 2020 (both included). After eliminating duplicate papers and applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the final study consists of 21 articles. The results of these studies on the prevalence of cyberbullying and suicidal behavior (including ideation, planning, and/or attempts) in adolescent students were analyzed, as well as the data on the chain of suicidal behavior in victims of cyberbullying and the psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying and suicidal behavior. Variations were found across the studies in the prevalence of cyberbullying and suicidal behavior. In all the studies, relationships between cybervictimization and suicidal behavior were observed. Suicidal ideations and attempts were significantly more prevalent in cyberbullying victims, and this was a risk factor for suicidal behavior in adolescent students. These findings confirm the need to implement effective programs in schools worldwide for the prevention of cyberbullying and suicidal behavior in adolescence.

Key words: cyberbullying, suicidal behavior, adolescents, students, systematic review

Resumen

El propósito principal de este trabajo ha sido realizar una revisión sistemática de la literatura científica más actual sobre la conducta suicida en víctimas de cyberbullying. Se han consultado cinco bases de datos, Web of Science, Scopus, PsycInfo, PsycArticles y PubMed con el fin de examinar los trabajos publicados entre 2018 y 2020 (ambos inclusive). Después de eliminar los trabajos duplicados y de aplicar los criterios de inclusión y exclusión, el estudio final consta de 21 artículos. Se han analizado los resultados de estos trabajos sobre la prevalencia del cyberbullying y de la conducta suicida (incluyendo ideación, planificación y/o tentativa) en el alumnado adolescente, se han examinado los datos sobre la cadena de la conducta suicida en las víctimas de cyberbullying, así como los factores psicosociales de riesgo asociados al cyberbullying y a la conducta suicida. Se encontraron variaciones entre los estudios en cuanto a la prevalencia del cyberbullying y de la conducta suicida. En todos los trabajos se observaron relaciones entre la cibervictimización y la conducta suicida. Las ideaciones y tentativas suicidas fueron significativamente más prevalentes en las víctimas de cyberbullying, siendo éste un factor de riesgo de la conducta suicida en los adolescentes. Estos hallazgos confirman la necesidad de implementar en el contexto escolar en todos los países del mundo programas eficaces para la prevención del cyberbullying y de la conducta suicida en la adolescencia.

Palabras clave: cyberbullying, conducta suicida, adolescentes, alumnado, revisión sistemática

Introduction

The use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs hereinafter) has spread so quickly and become so extended in today’s society that it is difficult to find an adolescent who does not use his or her smartphone or laptop daily (Buelga et al., 2019). The problem arises when instead of ICTs being used in positive ways, such as to promote positive interpersonal relationships with peers (Ortega-Barón et al., 2021), they are used to cause harm to others.

Cyberbullying is defined as the use of electronic devices by one or more people to intentionally and repeatedly attack someone who cannot easily defend him or herself (Kowalski et al., 2014). This type of online bullying can be direct (threats, insults, isolation, etc.) or indirect (identity theft, hacking, manipulation/distribution of photos or videos, etc.). The prevalence of cyberbullying is highly variable according to the studies; it ranges from 5% to 72% (Zych et al., 2016), with an average incidence of 23% for cybervictims, 16% for cyberbullies, and 18% for the dual role of cyberbully-victim (Buelga et al., 2017). However, there is more agreement among the authors about the fact that more cyberbullies are boys and more cybervictims are girls. Moreover, more cyberbullying victims are observed in students in the first stage of secondary school (junior high), and more cyberbullies and cyberbully-victims are found in older students (Kowalski et al., 2014).

Several factors can explain the global problem of cyberbullying. One of the causes is the availability and almost complete presence of the smartphone in the young population in recent years (Buelga et al., 2019). In Spain, 41.4% of 11-year-old preadolescents have this device, and 95.7% have a smartphone at age 15 (National Institute of Statistics [INE], 2020). In addition, the anonymity of the Internet means that many victims do not know the identity of their cyberbully, and they feel particularly vulnerable because they do not really know who is attacking them (Kowalski et al., 2014). This helplessness and hopelessness felt by victims is exacerbated by the 24/7 accessibility (24 hours a day, 7 days a week), viral nature, and loss of control over harmful contents uploaded to the Internet (Ortega-Barón et al., 2019).

Therefore, cyberbullying can cause even more harm to the victim than traditional bullying (Estévez et al., 2020; Navarro et al., 2015), and the distress increases when the victim experiences various victimizations (Cava et al., 2020; González-Cabrera, Machimbarrena, Fernández-González, et al., 2019; Quintana-Orts et al., 2021). The fact is that most of the time there is a situation of poly-victimization, where traditional bullying overlaps with cyberbullying (González-Cabrera, Machimbarrena, Ortega-Barón, et al., 2019; Víllora et al., 2020). In this regard, Kowalski et al. (2014) find that approximately 80% of traditional bullying victims are also victims online.

Certainly, cyberbullying is a global public health problem (Dennehy et al., 2020; John et al., 2018; Kwanya et al., 2021) whose impact has been associated with several indicators of psychosocial maladjustment, among which suicidal behavior stands out due to its severe consequences. In the meta-analysis by Van Geel et al. (2014), the authors show that 20% of cyberbullying victims have suicidal ideations, and between 5% and 8% have attempted self-harm. Suicidal ideation is the first link in the chain of suicidal behavior; it is a predictor of future attempts and completed suicide (Yazdi-Ravandi et al., 2021). The World Health Organization [WHO] (2019) reports that suicide in young people from 15 to 19 years old is the second leading cause of death in girls and the third leading cause in boys. In Spain, as in the rest of the world, suicide in young people has increased considerably in recent years (INE, 2021). Thus, whereas in 2008 and 2009 there were 88 suicides in adolescents from 15 to 19 years old, in 2018-2019 the figure rose to 138 suicides.

Given this background, the main purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the most recent scientific literature on cyberbullying and suicidal behavior in adolescent students. Specifically, we were interested in discovering a) the prevalence of cyberbullying and suicidal behavior in different countries and continents, and the differences found according to the sex and age of the adolescent; b) the results on suicidal behavior in victims of cyberbullying; and c) the risk and protective factors associated with cyberbullying and suicidal behavior.

Method

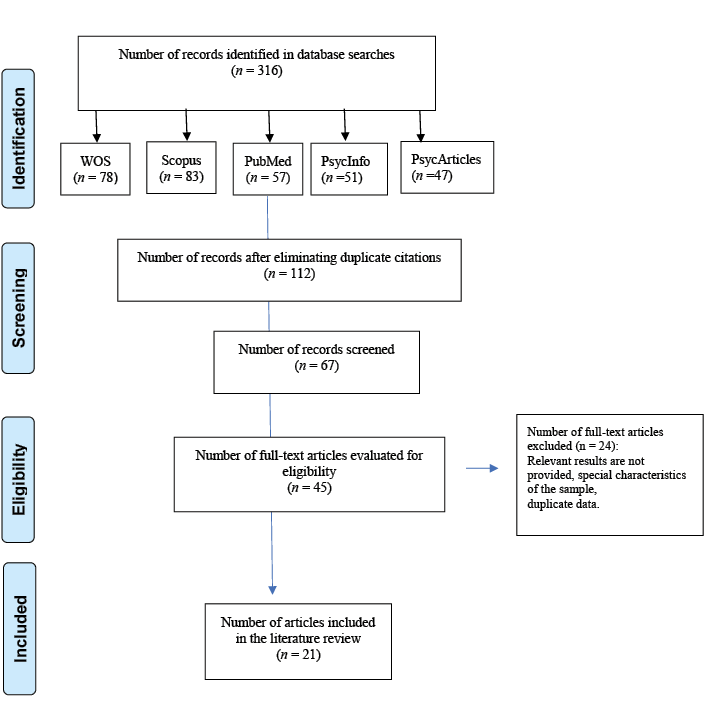

We followed the criteria of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses protocol, PRISMA-P (Shamseer et al., 2015). The study was also included in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, ID: CRD42021259414).

The information search was carried out between October and December 2020 (both included), and five databases were consulted: Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, PsycInfo, and PyscArticles. The search terms (in title, abstract, or keyword) were: Cyberbullying AND Suicidal (OR Suicide) AND Victims (OR Victimization). The search focused on the past three years (2018, 2019, 2020), in order to include the most recent evidence about the topics studied.

The inclusion criteria for the papers were that they had to: a) analyze suicidal behavior in victims of cyberbullying; b) be published between 2018 and 2020; c) examine this topic in students from 11 to 18 years old); and d) be written in English or Spanish. The following were excluded: a) articles that did not provide relevant results on the topic; b) articles with samples in populations of adults and/or with special characteristics; c) studies not published in English or Spanish; d) papers that were not scientific articles.

Results

Study selection

In the initial information search phase (Figure 1), 316 articles were found in the five databases consulted, with the largest number found in Scopus (n = 83). The references for these 316 articles were imported into the Zotero bibliography manager, eliminating duplicate papers (n = 204). After the screening process (Figure 1), 45 full-text articles were evaluated, and 24 of them were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria. The literature review for our analysis, finally, consists of 21 studies. The screening and eligibility process and the final study selection were performed by two authors of this manuscript. Cohen’s Kappa coefficient of agreement between the researchers in the screening phase was κ = 0.714, and κ = 0.833 in the phase of eligibility and final selection of the articles.

FIGURE 1. PRISMA Flow chart for study selection

Characteristics of the selected studies

The studies were carried out on all the continents except Africa. They were conducted in North America (n = 8); the United States stood out with five studies, and Canada had three. In addition, there are several studies from Asia (n = 7), carried out in South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, China, and Taiwan. Likewise, several studies were conducted in Europe (n = 5), predominantly in Spain with three studies; and one study was carried out in Australia.

Compared to 2018 (n = 4), twice as many articles were produced in 2019 (n = 8) and in 2020 (n = 9). In terms of journals and publication categories, the psychiatry category stands out (n = 8), as well as the journal Psychiatry Research with three articles (14.2%), published in 2018, 2019, and 2020, respectively. Articles published in the public, environmental, and occupational health category (n = 6) and the psychology category (n = 5) can also be highlighted. Moreover, 80% of the articles from Asia were published in the BMC series in various health science journals.

TABLE I. Summary of characteristics of the articles sorted by year of publication

|

Year |

Authors |

Country |

Journal |

|

2020 |

Abrahamyan et al. |

Portugal |

Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health |

|

2020 |

Baiden & Tadeo |

USA |

Child Abuse & Neglect |

|

2020 |

Islam et al. |

Australia |

Psychiatry Research |

|

2020 |

Kim, Walsh, et al. |

USA |

Journal of School Nursing |

|

2020 |

Kim, Shim, et al. |

South Korea |

Children and Youth Services Review |

|

2020 |

Nagamitsu et al. |

Japan |

BMC Pediatrics |

|

2020 |

Nguyen et al. |

Vietnam |

BMC Public Health |

|

2020 |

Perret et al. |

Canada |

Journal of child psychology and psychiatry |

|

2020 |

Sampasa-Kanyinga et al. |

Canada |

Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences |

|

2019 |

Alhajji et al. |

USA |

Global Pediatric Health |

|

2019 |

Chang et al. |

Hong Kong |

Psychiatry Research |

|

2019 |

Hinduja & Patchin |

USA |

Journal of School Violence |

|

2019 |

Iranzo et al. |

Spain |

Psychosocial Intervention |

|

2019 |

Kim et al. |

Canada |

The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry |

|

2019 |

Kuehn et al. |

USA |

Crisis- The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention |

|

2019 |

Peng et al. |

China |

BMC Psychiatry |

|

2019 |

Wang et al. |

Taiwan |

BMC Public Health |

|

2018 |

Extremera et al. |

Spain |

Frontiers in Psychology |

|

2018 |

Lucas-Molina et al. |

Spain |

Psychiatry Research |

|

2018 |

Rodelli et al. |

Belgium |

Preventive Medicine |

|

2018 |

Wiguna et al. |

Indonesia |

Asian Journal of Psychiatry |

Study of the sample population of the analyzed articles

The sample population is composed of 105,437 students in compulsory secondary education (7th-10th grade) and high school (11th-12th grade) between 11 and 18 years old. Almost all the studies included the entire educational cycle. An exception is the study by Nguyen et al. (2020), whose sample consisted only of students in the 6th grade (11 years old). In most of the articles, the distribution of students by sex is proportional, except in the longitudinal study by Kim, Walsh et al. (2020), whose sample has twice as many boys as girls. In addition, 90.4% (n = 19) of the studies are based on a cross-sectional design, whereas 9.6% (n = 2) use a longitudinal design.

Prevalence of cyberbullying and suicidal behavior

The prevalence of cyberbullying in the cybervictim role ranges from 1.8% in Japan (Nagamitsu et al., 2020) to 22.1% in the United States (Hinduja & Patchin, 2019) (Table II). This percentage increases to 52% in the study by Wigunaa et al. (2018) in Indonesia for the dual role of cybervictim-cyberbully. The prevalence of traditional bullying victimization is reported by several studies (Baiden & Tadeo, 2020; Hinduja & Patchin, 2019; Nguyen, et al., 2020), as well as the continuation of offline victimization in the online context (Baiden & Tadeo, 2020; Islam et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2019). Wang et al. (2019) in Taiwan find that 9.4% of children in school are victims of cyberbullying and traditional bullying. In Spain, in the study by Iranzo et. al. (2019), the authors find significant relationships between cybervictimization and school victimization.

Four studies provide data on the prevalence of cybervictimization by gender, and three of them point to a considerably higher percentage of cybervictims among girls (Alhajji, et al., 2020, Sampasa et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019). With regard to age, Perret et al. (2020) conclude that the highest prevalence of cybervictimization occurs at 15 years of age, which coincides with the results from Lucas-Molina et al. (2018) for boys, but not for girls, whose age of highest risk is 14 years old.

Regarding suicidal behavior, almost all the studies provide data on the first phase of the suicidal chain, analyzing the incidence of suicidal thoughts in students. The prevalence of suicidal ideation presents, as in cyberbullying, considerable variability, ranging from 6.8% - 7.1% (Nguyen et al., 2020; Wigunaa, et al., 2018) to 23.2% - 25.7% (Lucas-Molina et al., 2018; Nagamitsu et al., 2020). However, in many studies, the prevalence of suicidal ideation is between 15% and 20% (Baiden & Tadeo, 2020; Chang et al., 2019; Rodelli et al., 2018). Only three studies provide data on suicide planning, with the incidence also varying between 2.9% (Nguyen et al., 2020) and 14.5% (Alhajji et al., 2019). Nine studies report the prevalence of suicide attempts, which range from 1.4% to 8.5% (Nguyen et al., 2020). There is more risk of suicidal behaviors in girls (Iranzo et al., 2020; Kim, Walsh et al. (2020). Regarding age, the results are inconclusive (Lucas-Molina et al., 2018; Perret et al., 2020). Thus, whereas in Canada, Peret et al. (2020) find that the age of highest risk of suicidal ideation and attempts is 17 years old, Nagamitsu et al. (2020), with a sample of 22,419 students in Japan, conclude that the age of highest risk of suicide attempts is 14-15 years old.

Cybervictimization and suicidal behavior

All the studies find significant relationships between cyberbullying and suicidal behavior. On the one hand, studies reveal that more than one-third of cybervictims (Abrahamyan et al., 2020; Peng, et al., 2019), and even almost half and more than half (Alhajji et al., 2020; Nagamitsu et al., 2020), have suicidal ideations. Almost 20% of cybervictims have made suicide attempts in the study by Nagamitsu et al. (2020), and 11.1% of 11-year-old cybervictims have attempted suicide according to the study by Nguyen et al. (2020).

On the other hand, regarding the degree of risk, the study by Chang et al. (2019) concludes that the probability of suicidal ideation in cybervictims increases 148%. In addition, some studies find that the risk of suicidal ideation in cybervictims increases considerably when they are also victims of school bullying (Abrahamyan et al., 2020; Baiden & Tadeo, 2020; Islam et al., 2020). Articles on sex differences in cybervictims’ suicidal behavior agree that girls are at a greater risk of ideations (Abrahamyan et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2019; Kuehn et al., 2019; Rodelli et al., 2018) and self-harm attempts (Kuehn et al., 2019). This partially agrees with the study by Alhajji et al. (2019). Although these authors note that the risk of suicidal ideation is higher in girls, the risk of suicide planning and attempts is higher in cybervictimized boys. With regard to age, Perret et al. (2020) find that there is a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation at the age of 15 in cybervictims, and of suicide attempts at the age of 17. In addition, Rodelli et al. (2018) find in Belgium that suicidal ideation is more frequent between the ages of 12 and 14.

Factors associated with cyberbullying and suicidal behavior

Some studies express interest in some individual psychological risk factors associated with suicidal ideation: depressive symptomatology (Baiden & Tadeo, 2020), sadness and hopelessness (Abrahamyan et al., 2020), low self-esteem (Kim, Shim, et al. 2020), negative emotions (Iranzo et al., 2019), and dissatisfaction with life (Chang et al., 2020). Likewise, other authors are interested in individual factors that buffer suicidal behavior in cybervictims, such as emotional intelligence (Extremera et al., 2018) and healthy lifestyles (Rodelli et al., 2018).

In some studies, on family variables, authors such as Nagamitsu et al. (2020) and Sampasa et al. (2020) find that poor quality family relationships between parents and children increase the risk of suicidal ideation in cybervictimized children. In contrast, parental acceptance (Nguyen et al., 2020) and satisfaction with family life (Chang et al., 2019) decrease the effect of cyberbullying on suicidal ideation and self-harm attempts. Regarding the school context, Kim, Walsh, et al. (2020) find in their longitudinal study that school connectedness (sense of belonging, relationships with peers and teachers) significantly reduces the impact of cyberbullying on suicidal behavior. In contrast, academic pressure (Nguyen et al., 2020) and negative experiences at school (Wang et al., 2020) increase the likelihood of suicidal ideation and attempts in students.

TABLE II. Summary of the results of the studies (n= 21) on cyberbullying and suicidal behavior

|

Year |

Author |

Participants and country |

Prevalence of cyberbullying (CB) and other data on CB |

Prevalence of suicidal behavior (SB) and other data on SB from the sample |

Results on SB in victims of cyberbullying (CVs) |

Factors associated with CB and SB |

|

2020 |

Abrahamyan et al. |

2,602 students from 7th grade to 12th grade, 12 -18 years old, Portugal (45.2% ♂, 54.8% ♀). |

No data available. |

12 months 11.3% suicidal ideation (13.4% ♀, 9.2% ♂). |

35.75% CVs have had suicidal ideations (38.5% ♀, 33% ♂) CVs have 5 times + risk of suicidal ideations (6.8 ♀, 5 ♂), and 7.7 times + when there is also bullying (9.7 ♀, 5.8 ♂). |

+ prevalence of suicidal ideation in adolescents with sadness and hopelessness, involved in physical fights, and members of single-parent families. |

|

2020 |

Baiden & Tadeo |

14603 students 14 - 18 years old, USA. (48 % ♂, 52% ♀). |

Past 12 months 5.1 % cybervictims 9.1% cybervictims + victims of school bullying (1 out of every 10 students). |

12 months 18% suicidal ideations. |

CVs have twice the risk of suicidal ideation, and 3 times + when there is also bullying.. |

High correlation between depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. |

|

2020 |

Islam et al. |

2166 students, grades 7-12, 12-17 years old, Australia (52.3% ♂, 47.7% ♀). |

12 months 11.8% cybervictims 11.2% cybervictims + bullying. |

12 months 7.8% suicide ideation 5.9% planning 2.5% tentative Las ♀ report + suicidal behaviors. |

CVs have 8.4+ risk of suicidal planning, 4.7 + of attempt and 5.2 + of attempt and planning. When bullying is also present. 8.8 times + risk of planning, 4.8 times + of attempt, 5.36 + of attempt and planning |

People with depression, anxiety are + at risk of being bullied; aggravates mental health of victims. The path from cyber victimization to mental disorders is stronger. |

|

2020 |

Kim, Walsh, et al. |

93 students from 8th grade (T1, T2), 9th grade (T2), 10th grade (T3), 13- 16 years old, USA (66.7% ♂, 33.3% ♀). |

30 days: By sex: ♂: 16% cyberbullies, 5% cybervictims, 16% dual role. ♀: 32% cyberbullies, 8% dual role. No student reported only cyber victimization; all cybervictims were also cyberbullies. |

♀ + risk of suicidal behaviors. |

Cybervictimization, associated with suicidal behaviors. |

Connectedness with school (sense of belonging, relationships with peers, teachers) is a protective factor of CB in suicidal behavior. |

|

2020 |

Kim, Shim, et al. |

7412 students 7th grade to 12th grade, 12- 18 years old, South Korea (58% ♂, 42% ♀). |

Cyber-victimization has a direct effect on loneliness, depression, anxiety. |

Negative emotions have a direct effect on suicidal ideation. |

Direct effect between CB and suicidal ideation, stronger effect with traditional bullying. |

Negative emotions mediate the effects of CB and bullying on suicidal ideation Self-esteem moderates the effect of negative emotions on suicidal ideation. |

|

2020 |

Nagamitsu, et al. |

22419 students in grades 7-12, ages 13-18, Japan. |

30 days 1.8% experienced CB. |

12 months 25.7% suicidal ideations 5.4% attempts 9th grade, 14-15 years old (3rd ESO) + high percentage of attempts (5.9%). Suicidal ideations high in 7th grade, 12-13 years old (25.7%) and in 11th grade 16-17 years old (27.6%). |

52.0% of CVs have had suicidal ideations, 19.9% attempts. Almost twice as many attempts in ♀ (6.6% vs. 3.5%). Cybervictimization major risk factor for ideation and attempts in all school grades. |

7th-9th grade: Stress in family relationships with parents and stress due to traditional bullying + elevated risk factors for suicidal behavior. 10th-12th grade: bullying and stress due to sexual identity. |

|

2020 |

Nguyen et al. |

648 students in 6th grade, 11 years old, Vietnam. (52.3% ♂, 47.7% ♀). |

30 days: 9% cybervictims 17.6% bullying victims. |

12 months, 7.1% suicidal ideation, 2.9% suicidal planning, 1.4% suicide attempt. |

19.6% of the CVs have had suicidal ideations, 21.1% planning, 11.1% attempts. |

Perceived academic pressure is related to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Perceived parental acceptance decreases suicidal ideation and self-injury. |

|

2020 |

Perret et al. |

Cohort of 2120 adolescents followed at 12, 13, 15, and 17 years of age, Canada. |

Longitudinal study: 1.8% cybervictims 15 years old: higher prevalence of CV (4.3% sometimes, 1.2% very often), 19.3% ♀, 10.7% ♂). |

12 months Prevalence of suicide ideation/attempt in non-victimized students. 13 and 15 years: 2.7%. 17 years: 4.6%. |

Between 2.29 and 4. 20 + of suicidal ideation and attempts in CVs. Prevalence of suicidal ideation/attempts in CVs: 15 years: 22.7%. 17 years: 40.6%. |

Victim of traditional bullying is associated with suicidal behavior over time. CB is an immediate + risk factor for suicide in the first two years of bullying. |

|

2020 |

Sampasa-Kanyinga et al. |

5478 students, grades 7 to 12, 12- 20 years old, Canada (52.2% ♂, 47.8% ♀). |

12 months 18.7% cybervictims (15.4% ♂, 22.2% ♀). |

12 months 12.4% suicidal ideations (8.5% ♂, 16.3% ♀), 3.2% attempts (1.8% ♂, 4.6% ♀). |

CVs have 2.38 + risk of suicidal ideations and 2.07% + of attempts. |

Poor parent-child relationships and the male gender are risk factors for suicidal ideation in CVs. |

|

2019 |

Alhajji et al. |

15465 students from 9th grade to 12th grade, USA (51.3% ♂, 48.7% ♀). |

12 months 15.5% cybervictims (32% ♂, 68% ♀). |

12 months 17.6% suicidal ideations, 14.5% planning. |

Cybervictims: 41.2 % have ideations 34.5%, suicide planning. ♀ have 2.5 times + probabilities of being cybervictimized and 2 times + of suicidal ideations. ♂ have 2.5 times + probabilities of suicide planning. |

Cybervictims transfer their negative experience to others. |

|

2019 |

Chang et al. |

3,522 students 7th grade to 12th grade, 13 - 17 years old, Hong Kong (56.2% ♂, 43. 8% ♀). |

12 months 11.9% cybervictims. |

12 months 21. 8% suicidal ideations. |

148% increased likelihood of suicidal ideation in cybervictims 3 times + risk of suicidal ideation in cybervictims. |

Satisfaction with life partially mitigates effect of CB on suicidal ideation. |

|

2019 |

Hinduja & Patchin |

2670 students 12 - 17 years old, USA. (49.6% ♂, 49.9% ♀). |

30 days Cybervictimization ranges according to bullying behavior. The + prevalent: 22.1% (someone posted mean or hurtful comments about me), 19.6% (someone spread rumors about me). |

12 months 16.1% suicidal ideation (16.7% ♀ y 15.3% ♂). 2.1% attempts (2.2 % ♀ y 2% ♂). |

Cybervictims have 1.6 times + risk of suicidal ideation and 1.02 times + risk of attempts, When bullying is also present, cybervictims have 5.4 times + risk of suicidal ideation and 11.4 times + risk of suicide attempts. |

Older students (15-17 years) + risk of suicidal behavior (ideation and attempt). |

|

2019 |

Iranzo et al. |

1062 students 7th grade to 12th grade, 12- 18 years old, Spain. (51.5% ♂, 48.5%♀). |

12 months Cyberbullying is positively associated with bullying; relationships higher with relational bullying, followed by verbal bullying. |

Last week suicidal ideation Significant sex differences; ♀ score higher on suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation associated with psychological distress and perceived stress.. |

Direct effects between cybervictimization and suicidal ideation, and indirect effects of these variables through perceived stress, loneliness, psychological distress, and depressive symptoms. |

The variables of psychological distress, stress, loneliness, depressive symptomatology, and psychological discomfort are antecedents of suicidal ideation. |

|

2019 |

Kim et al. |

4940 students Grades 7 to 12, 13 -17 years old, Canada (43. 3% ♂, 56. 7% ♀). |

12 months 10.5% cybervictims (2 or + times) (13. 3% ♀ and 7.8% ♂). |

12 months 13.5% suicidal ideations (18% ♀ and 9.1% ♂). |

Cybervictims have 3.5 + risk of having suicidal ideations (4.6 ♀ and 2.4 ♂). |

Cybervictimized ♀ have + risk of consuming substances, non-significant association for ♂. |

|

2019 |

Kuehn et al. |

10404 students, 7th grade to 12th grade, from 12-19 years old, USA |

12 months 19.0% cybervictims: 11.3% for LGTB, 5. 4% academic difficulties. |

12 months 8.5% suicide attempt. |

Cybervictimization increases the risk of suicide attempt by 10.4% in the presence of the covariates: female sex, sleep problems, fights, obesity, computer time, traditional bullying, etc. |

LGBT sexual orientation is associated with bullying (r=.20) and CB (r=.26). |

|

2019 |

Peng et al. |

2647 students, 7th grade to 9th grade, 12 - 14 years old, China. (48. 8% ♂, 51.2% ♀). |

12 months 9% cybervictims, 3.5% victims of CB + bullying |

12 months 23.1% suicidal ideation (19.4% ♀ y 14.0 % ♂) 3.0% ideation + self-injury (4.2% ♀ y 2% ♂). 4.2% suicide attempt (5.9% ♀ y 2.6% ♂). |

Cybervictims: 27.4% have suicidal ideation, 6.2% suicidal ideation and self-harm, 6.8% suicidal attempts. Cybervictims + Bullying: 35.9% suicidal ideation, 7.6% suicidal ideation and self-injury, 14.1% attempts. CB risk factor for suicidal ideation and self-injury with ideation. CB + bullying risk factor for suicide attempts. |

Polyvictimization (CB and bullying) + vulnerable group for emotional maladjustment. Psychopathological symptoms: risk factors in a) suicidal ideation; b) ideation and self-injury; c) suicide attempts. |

|

2019 |

Wang et al. |

2028 students in 10th grade and 11th grade, 14- 20 years old, Taiwan (48. 6% ♂, 51.4% ♀). |

2 months 9.9% cybervictims, (61% ♀). 13.3% victims of traditional bullying 9.4% victims of CB + bullying (70% ♀). |

30 days Suicidal ideation 6.6% cybervictims, 15.6% cybervictims + victims of bullying. |

Combined bullying (traditional bullying and CB) in the dual role of bully-victim is associated with suicidal ideation, and also with being a boy ♂ |

Bullying and CB overlap. Other risk variables in combined bullying in the dual role of victim and bully are negative experiences at school and Internet addiction. |

|

2018 |

Extremera et al. |

1660 students, 7th grade to 12th grade, 12- 18 years old, Spain (49.6% ♂, 50. 4% ♀). |

Cybervictimization is negatively associated with EI and self-esteem. + cybervictimization in ♀. |

+ risk of suicide (ideations and behavior) in ♀. |

+ Relationship between suicide risk and cybervictimization. |

EI has a buffer effect between cybervictimization and suicide risk. |

|

2018 |

Lucas-Molina et al. |

1664 students, 9th grade to 12th grade, 14 -19 years old, Spain. (47% ♂, 53% ♀). |

2 months 6.4% cyber-victims by Internet 8.6% cybervictims by mobile phone. + prevalence of cybervictimization in adolescents + young adults, 15 years old in ♂, 14 years old in ♀. |

12 months 23.2% suicidal ideation. There are + suicidal ideations in the ♀. No significant differences by age. |

Direct positive relationship between the three types of cyberbullying and suicidal ideation. |

Subjective wellbeing and the female gender indirect variables between cybervictimization by mobile phone and traditional bullying with suicidal ideation. |

|

2018 |

Rodelli et al. |

1037 students, 7th grade to 12th grade, 12 -18 years old, Belgium (50% ♂, 50% ♀). |

6 months 7.4% cybervíctims 9% cyberbullies 49.5% spectators of CB |

6 months 22% suicidal ideations. |

Female cybervictims and cyberbullies and with younger ages (12-14 years) + risk of suicidal ideation. |

Healthy lifestyles (diet, sleep, physical activity) decrease suicidal ideation in cybervictims and cyberbullies. |

|

2018 |

Wigunaa et al. |

2917 adolescents 11- 18 years old, Indonesia |

6 months 5.1% cybervictims 2. 4% cyberbullies, 52.% cybervictim/cyberbully 12-14 years + risk of having the role of cybervictim and cyberbully. 15-17 years + risk of dual role. |

6.8% suicidal ideation 6.3% self-injury 2.4% suicide attempt Being a victim of CB increases the risk of self-injury. |

♀ cybervictims and cyberbullies have 1.90 + risk of suicide ideations and 2.11 + risk of attempts. |

Male cybervictims/cyberbullies have + risk of externalizing behavior: smoking, alcohol consumption, and self-injury, whereas ♀ have + risk of internalizing with suicidal ideation and attempts. |

Conclusions

The main purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the most recent scientific literature on cyberbullying and suicidal behavior (including ideation, planning, and/or attempts) in adolescent students. Regarding the first objective of this study on the prevalence of cyberbullying, significant variability was observed across the studies (Lucas-Molina et al. 2018; Nagamitsu et al., 2020; Sampasa et al., 2020), and even within the same country (Alhajji et al., 2020; Baiden & Tadeo, 2020). The prevalence of cybervictimization ranged from 1.8% in Japan (Nagamitsu et al., 2020) to 22.1% in the United States (Hinduja & Patchin., 2019). The conceptual and methodological divergence between different studies in assessing the problem of cyberbullying (Kowalski et al., 2014), as well as the sociocultural context of the participants (Chun et al., 2020), may explain these variations across studies.

Despite these divergences between some of the studies, it is worth mentioning that a certain consensus was found among the North American authors regarding the time interval for measuring cyberbullying. All the studies carried out in the United States (except the study by Hinduja & Patchin, 2019), Canada, and Australia measure cyberbullying in the previous 12 months. In Asia and Europe, the time period varies considerably: the past 30 days (Nagamitsu et. al, 2020, Nguyen et al. 2020), two months (Wang et al., 2019), six months (Rodelli et al., 2018, Wigunaa et al., 2018), and 12 months (Peng et al., 2019; Lucas-Molina, 2018). This might explain why the mean prevalence of cybervictimization in North America is higher (15%) than what was found in studies from Asia and Europe, dropping to 7% when cyberbullying is measured in a shorter time interval. In previous studies carried out in Spain by Buelga et al. (2010) and by Navarro et al. (2015), in which cyberbullying is assessed in the previous 12 months, the prevalence obtained by the authors ranges, as in North America, between 20 and 25%.

In addition, some studies, such as the one by Baiden & Tadeo (2020), showed that a high percentage of adolescents are victims of cyberbullying and traditional bullying, which is consistent with the idea of the continuation and overlapping of offline and online victimization (González-Cabrera, Machimbarrena, Ortega-Barón, et al., 2019). Moreover, in line with previous studies (Kowalski et al., 2014), girls were found to be more vulnerable than boys to both types of victimization (Alhajii et al. 2020; Sampasa et al. 2020; Wang, 2019). With regard to age, the studies by Perret et al. (2020) and Lucas-Molina et al. (2018) agree with previous studies (Yubero et al., 2017) by showing a higher prevalence of cybervictimization in early adolescence (Buelga et al., 2010; John et al., 2018).

Regarding the prevalence of suicidal behavior, almost all the studies assessed this variable using the previous 12 months as a criterion, and they all provide data on suicidal ideation. The prevalence of the first antecedent of suicide, that is, ideations in students, ranges between 17 and 20% in Asia (Chang et al., 2019; Nagamitsu et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2019), Europe (Lucas-Molina et al., 2018; Rodelli et al., 2018), and the United States (Alhajji et al., 2020; Baiden & Tadeo, 2020). Only three studies provide data on suicide planning (Alhajii et al., 2019; Islam et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020). The prevalence of suicide planning and suicide attempts in adolescent students in the United States ranges from 8.5% (Kuehn et al., 2019) to 14.5% (Alhajji et al. 2019). Findings from studies that analyzed gender differences in suicidal behavior agree that, as in cybervictimization, being a female is a risk factor (Iranzo et al., 2019; Kim, Walsh, et al., 2020).

Regarding the second objective of our review, all the studies find significant relationships between cyberbullying and suicidal behavior (Abrahamyan et al., 2019, Iranzo et al., 2019; Peng et al., 2020). Studies that provide data on the prevalence of suicidal ideation in cybervictims report high percentages, ranging from 30% in Portugal (Abrahamyan et al., 2019) to 52% in Japan (Nagamitsu et al., 2020). In addition, 20% of Japanese adolescent cybervictims (Nagamitsu et al., 2020) and 11.1% of 11-year-old Vietnamese cybervictims (Nguyen et al., 2020) had attempted self-harm in the past year. The young age of Vietnamese cybervictims who, with hardly any life history, attempt to take their own lives and have a very high risk of subsequent attempts (Okamura et al., 2021; WHO, 2019), is very disturbing. It is true that, in Asia, a current priority in countries such as Japan is suicide prevention in young people, through municipal policies that allow greater early targeting and intervention in high-risk groups (Okamura et al., 2021).

Regarding the degree of cyberbullying risk in suicidal behavior (Hinduja & Patchin, 2019; Kuehn et al., 2019; Sampasa et al., 2020; Wigunaa et al., 2018), Chang et al. (2020) observed that cybervictims are 148 times more likely to have suicidal ideations and five times more likely to plan and carry out self-harm attempts (Islam et al., 2020). The risk of suicidal behavior in the victim increases when traditional bullying also takes place (Abrahamyan et al., 2020; Baiden & Tadeo, 2020; Hinduja & Patchin, 2019). These data point to the idea of the cumulative and negative risk of victimization experiences for the victim’s mental health (Cava et al., 2020; González-Cabrera, Machimbarrena, Fernández-González, et al., 2019).

Finally, suicidal behavior in cybervictims can be buffered by some individual, family, and school factors. Emotional intelligence (Extremera et al., 2018) and healthy lifestyles -diet, sleep, and physical activity- (Rodelli et al., 2018) are some individual factors suggested in some studies in this review. In addition, parental acceptance and family satisfaction are family protective factors that decrease the impact of cyberbullying on suicidal ideation and self-harm (Chang et al., 2019). Likewise, school connectedness - sense of belonging, relationships with peers and teachers - buffers the negative impact of prolonged cyberbullying on suicidal behavior (Chang et al., 2019).

This review has some limitations; first, there are differences in the conceptualization and measurement of cyberbullying and suicidal behavior across the studies. Second, although the time period for article inclusion is quite recent (2018-2020), the data for the studies were collected before the COVID-19 pandemic, and these issues may have worsened during the pandemic. Third, most of the studies are cross-sectional, which keeps us from establishing a cause-effect relationship between cyberbullying and suicidal behavior. Fourth, there are sociocultural differences between the studies that must be taken into account when interpreting their results.

Despite these limitations, this international review provides very interesting data on cyberbullying and suicidal behavior in adolescent students. These results ratify the WHO (2019) imperative on the global priority of establishing effective action plans for the prevention of suicide in the youth population and the healthy use of ICTs in the school context.

References

References marked with an asterisk (*) indicate the studies included in the review:

*Abrahamyan, A., Soares, S., Peres, F. S., & Fraga, S. (2020). Exposure to violence and suicidal ideation among school-going adolescents. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 32(2-3), 99-109. https://doi.org/10.2989/17280583.2020.1848849

*Alhajji, M., Bass, S., & Dai, T. (2019). Cyberbullying, mental health, and violence in adolescents and associations with sex and race: Data from the 2015 youth risk behavior survey. Global Pediatric Health, 6, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X19868887

*Baiden, P., & Tadeo, S. K. (2020). Investigating the association between bullying victimization and suicidal ideation among adolescents: Evidence from the 2017 youth risk behavior survey. Child Abuse & Neglect, 102, 104417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104417

Buelga, S., Cava, M. J., & Musitu, G. (2010). Cyberbullying: Victimización entre adolescentes a través del teléfono móvil y de Internet [Cyberbullying: Victimization among adolescents through the mobile phone and the Internet]. Psicothema, 22(4), 784-789. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1020-49892012000700006

Buelga, S., Martínez–Ferrer, B., & Cava, M. (2017). Differences in family climate and family communication among cyberbullies, cybervictims, and cyber bully–victims in adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 164-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.07.017

Buelga, S., Martínez-Ferrer, B., Cava, M.-J., & Ortega-Barón, J. (2019). Psychometric properties of the CYBVICS Cyber-Victimization Scale and its relationship with psychosocial variables. Social Sciences, 8(1),1-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8010013

Cava, M.-J., Tomás, I., Buelga, S., & Carrascosa, L. (2020). Loneliness, depressive mood and cyberbullying victimization in adolescent victims of cyber dating violence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4269. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124269

*Chang, Q., Xing, J., Ho, R. T. H., & Yip, P. S. F. (2019). Cyberbullying and suicide ideation among Hong Kong adolescents: The mitigating effects of life satisfaction with family, classmates and academic results. Psychiatry Research, 274, 269-273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.054

Chun, J., Lee, J., Kim, J., & Lee, S. (2020). An international systematic review of cyberbullying measurements. Computers in Human Behavior, 113, 106485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106485

Dennehy, R., Meaney, S., Walsh, K. A., Sinnott, C., Cronin, M., & Arensman, E. (2020). Young people’s conceptualizations of the nature of cyberbullying: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 51, 101379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101379

Estévez, J. F., Cañas, E., & Estévez, E. (2020). The impact of cybervictimization on psychological adjustment in adolescence: Analyzing the role of emotional intelligence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3693. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103693

*Extremera, N., Quintana-Orts, C., Mérida-López, S., & Rey, L. (2018). Cyberbullying victimization, self-esteem and suicidal ideation in adolescence: Does emotional intelligence play a buffering role? Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 367. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00367

González-Cabrera, J., Machimbarrena, J. M., Fernández-González, L., Prieto-Fidalgo, Á., Vergara-Moragues, E., & Calvete, E. (2019). Health-related quality of life and cumulative psychosocial risks in adolescents. Youth & Society, 53(4), 636-653. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X19879461

González-Cabrera, J., Machimbarrena, J. M., Ortega-Barón, J., & Álvarez-Bardón, A. (2019). Joint association of bullying and cyberbullying in health-related quality of life in a sample of adolescents. Quality of Life Research, 29(4), 941-952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02353-z

*Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2019). Connecting adolescent suicide to the severity of bullying and cyberbullying. Journal of School Violence, 18(3), 333-346. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2018.1492417

Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE]. (2020). Encuesta sobre equipamiento y uso de tecnologías de información y comunicación en los hogares. https://www.ine.es/prensa/tich_2020.pdf

Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE]. (2021). Defunciones según la causa de muerte. Suicidios y lesiones autoinflingida, de 15 a 19 años. https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=7947

*Iranzo, B., Buelga, S., Cava, M.-J., & Ortega-Barón, J. (2019). Cyberbullying, psychosocial adjustment, and suicidal ideation in adolescence. Psychosocial Intervention, 28(2), 75-81. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a5

*Islam, Md. I., Khanam, R., & Kabir, E. (2020). Bullying victimization, mental disorders, suicidality and self-harm among Australian high schoolchildren: Evidence from nationwide data. Psychiatry Research, 292, 113364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113364

John, A., Glendenning, A. C., Marchant, A., Montgomery, P., Stewart, A., Wood, S., Lloyd, K., & Hawton, K. (2018). Self-harm, suicidal behaviours, and cyberbullying in children and young people: Systematic review. Journal of medical internet research, 20(4), e129. https://doi.org/10.2196/preprints.9044

*Kim, J., Shim, H. S., & Hay, C. (2020). Unpacking the dynamics involved in the impact of bullying victimization on adolescent suicidal ideation: Testing general strain theory in the Korean context. Children and Youth Services Review, 110, 104781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104781

*Kim, J., Walsh, E., Pike, K., & Thompson, E. A. (2020). Cyberbullying and victimization and youth suicide risk: The buffering effects of school connectedness. The Journal of School Nursing, 36(4), 251-257. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840518824395

*Kim, S., Kimber, M., Boyle, M. H., & Georgiades, K. (2019). Sex differences in the association between cyberbullying victimization and mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation in adolescents. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(2), 126-135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743718777397

Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N., & Lattanner, M. R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1073-1137. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035618

*Kuehn, K. S., Wagner, A., & Velloza, J. (2019). Estimating the magnitude of the relation between bullying, e-bullying, and suicidal behaviors among United States youth, 2015. Crisis, 40(3), 157-165. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000544

Kwanya, T., Kogos, A. C., Kibe, L. W., Ogolla, E. O., & Onsare, C. (2021). Cyber-bullying research in Kenya: A meta-analysis. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/GKMC-08-2020-0124

*Lucas-Molina, B., Pérez-Albéniz, A., & Fonseca-Pedrero, E. (2018). The potential role of subjective wellbeing and gender in the relationship between bullying or cyberbullying and suicidal ideation. Psychiatry Research, 270, 595-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.043

*Nagamitsu, S., Mimaki, M., Koyanagi, K., Tokita, N., Kobayashi, Y., Hattori, R., Ishii, R., Matsuoka, M., Yamashita, Y., Yamagata, Z., Igarashi, T., & Croarkin, P. E. (2020). Prevalence and associated factors of suicidality in Japanese adolescents: Results from a population-based questionnaire survey. BMC Pediatrics, 20(1), 467. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02362-9

Navarro, R., Yubero, S., & Larrañaga, E. (2015). Cyberbullying across the globe: Gender, family, and mental health. Springer.

*Nguyen, H. T. L., Nakamura, K., Seino, K., & Vo, V. T. (2020). Relationships among cyberbullying, parental attitudes, self-harm and suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from a school-based survey in Vietnam. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 476. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08500-3

Okamura, K., Ikeshita, K., Kimoto, S., Makinodan, M., & Kishimoto, T. (2021). Suicide prevention in Japan: Government and community measures, and high-risk interventions. Asia Pacific Psychiatry, 13(3), e12471. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12471

Organización Mundial de la Salud [OMS]. (2019). Suicidio: Datos y cifras. https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

Ortega-Barón, J., Buelga, S., Ayllón, E., Martínez-Ferrer, B., & Cava, M.-J. (2019). Effects of intervention program Prev@cib on traditional bullying and cyberbullying. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(4), 527. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040527

Ortega-Barón, J., Machimbarrena, J. M., Montiel, I., Buelga, S., Basterra-González, A., & González-Cabrera, J. (2021). Design and validation of the brief Self Online Scale (SO-8) in early adolescence: An Exploratory Study. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 41(7), 1055-1071. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431620978539

*Peng, Z., Klomek, A. B., Li, L., Su, X., Sillanmäki, L., Chudal, R., & Sourander, A. (2019). Associations between Chinese adolescents subjected to traditional and cyber bullying and suicidal ideation, self-harm and suicide attempts. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 324-332. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2319-9

*Perret, L. C., Orri, M., Boivin, M., Ouellet-Morin, I., Denault, A., Côté, S. M., Tremblay, R. E., Renaud, J., Turecki, G., & Geoffroy, M. (2020). Cybervictimization in adolescence and its association with subsequent suicidal ideation/attempt beyond face-to-face victimization: A longitudinal population-based study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(8), 866-874. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13158

Quintana-Orts, C., Rey, L., & Neto, F. (2021). Are loneliness and emotional intelligence important factors for adolescents? Understanding the influence of bullying and cyberbullying victimisation on suicidal ideation. Psychosocial Intervention, 30(2), 67-74. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2020a18

*Rodelli, M., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., Dumon, E., Portzky, G., & DeSmet, A. (2018). Which healthy lifestyle factors are associated with a lower risk of suicidal ideation among adolescents faced with cyberbullying? Preventive Medicine, 113, 32-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.05.002

*Sampasa-Kanyinga, H., Lalande, K., & Colman, I. (2020). Cyberbullying victimisation and internalising and externalising problems among adolescents: The moderating role of parent–child relationship and child’s sex. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 29(8), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796018000653

Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L. A., & the PRISMA-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ, 349, 7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647

Van Geel, M., Vedder, P., & Tanilon, J. (2014). Relationship between peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(5), 435. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4143

Víllora, B., Larrañaga, E., Yubero, S., Alfaro, A., & Navarro, R. (2020). Relations among poly-bullying victimization, subjective well-being and resilience in a sample of late adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020590

*Wang, C.-W., Musumari, P. M., Techasrivichien, T., Suguimoto, S. P., Tateyama, Y., Chan, C.-C., Ono-Kihara, M., Kihara, M., & Nakayama, T. (2019). Overlap of traditional bullying and cyberbullying and correlates of bullying among Taiwanese adolescents: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1756. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8116-z

*Wiguna, T., Irawati Ismail, R., Sekartini, R., Setyawati Winarsih Rahardjo, N., Kaligis, F., Prabowo, A. L., & Hendarmo, R. (2018). The gender discrepancy in high-risk behaviour outcomes in adolescents who have experienced cyberbullying in Indonesia. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 37, 130-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2018.08.021

Yazdi-Ravandi, S., Khazaei, S., Shahbazi, F., Matinnia, N., & Ghaleiha, A. (2021). Predictors of completed suicide: Results from the suicide registry program in the west of Iran. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 59, 102615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102615

Yubero, S., Navarro, R., Elche, M., Larrañaga, E., & Ovejero, A. (2017). Cyberbullying victimization in higher education: An exploratory analysis of its association with social and emotional factors among Spanish students. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 439-449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.037

Zych, I., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Marín-López, I. (2016). Cyberbullying: A systematic review of research, its prevalence and assessment issues in Spanish studies. Psicología Educativa, 22(1), 5-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pse.2016.03.002

Contact address: Sofia Buelga, Universidad de Valencia, Facultad de Psicología, Psicología Social. Av. Blasco Ibañez, 21, CP 46010 Valencia. E-mail: sofia.buelga@uv.es