Design and validation of the Self-Perception and Perception of Bullying in Adolescents Scale (SPB-A)1

Diseño y validación de la Escala de Autopercepción y Percepción del Acoso Escolar en Adolescentes (APAE-A)

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2022-397-538

Lucía Álvarez-Blanco

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4116-4864

María-Teresa Iglesias-García

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9577-7693

Antonio Urbano Contreras

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6973-1125

Verónica García Díaz

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2809-112X

Universidad de Oviedo

Abstract

This study constructs and validates the Self-perception and Perception of Bullying in Adolescents Scale to offer an instrument to assess bullying globally, also trying to make it quick and straightforward to complete. A total of 10,795 students of Compulsory Secondary Education with an average age of 13.94 years (51.1% girls and 48.9% boys) from public (54.4%) and state-subsidised (45.5%) schools in the Principality of Asturias (Spain) participated. The total sample was randomly divided into two halves for cross-validation with an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) on the subsamples mentioned above. The results present a scale with good reliability (α = .86) and composed of 27 items and 4 factors: Behaviours involving bullying (F1), Bullying behaviours witnessed (F2), Bullying behaviours experienced (F3), and Reaction to bullying behaviours (F4). The scale obtained is invariant according to the type of school, gender, and year. The brevity, simplicity, and reliability of this scale indicate that it may be of interest both at a research or diagnostic level and, later, in professional practice and socio-psycho-educational intervention from an eminently preventive or coping approach to bullying during adolescence.

Keywords: bullying, Secondary Education, school violence, coexistence, validation of instruments.

Resumen

Este estudio construye y valida la Escala de Autopercepción y Percepción del Acoso Escolar en Adolescentes con el objetivo de ofrecer un instrumento para evaluar de manera global el acoso escolar, procurando igualmente que sea sencillo y de rápida cumplimentación. Han participado 10795 estudiantes de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria con una edad media de 13.94 años (51.1% chicas y 48.9% chicos), pertenecientes a centros públicos (54.4%) y concertados (45.5%) del Principado de Asturias (España). La muestra total se dividió aleatoriamente en dos mitades para realizar una validación cruzada con un Análisis Factorial Exploratorio (AFE) y otro Análisis Factorial Confirmatorio (AFC) sobre las citadas submuestras. Los resultados presentan una escala con buena fiabilidad (α = .86) e integrada por 27 ítems y 4 factores: Conductas que suponen acoso (F1), Conductas de acoso presenciadas (F2), Conductas de acoso sufridas (F3) y Reacción ante las conductas de acoso (F4). La escala obtenida resulta invariable según la titularidad del centro, sexo y curso. La brevedad, sencillez y confiabilidad de esta escala indican que puede resultar de interés tanto a nivel de investigación o diagnóstico como, a posteriori, en la práctica profesional y de intervención socio-psico-educativa desde un enfoque eminentemente preventivo o de afrontamiento del acoso escolar durante la adolescencia.

Palabras clave: bullying, Educación Secundaria, violencia escolar, convivencia, validación de instrumentos.

Introduction

One of the main priorities of the educational system is the socialization and inclusion of people through a set of values, norms and behaviours necessary to guarantee the respect of both human rights and the diversity and individuality of each individual (Herrera-Espinoza & Cerezo-Ochoa, 2018).

The preventative and constructive approach to conflicts that arise naturally in socio-educational contexts is one of the most effective strategies for promoting positive and peaceful coexistence in these spaces (Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2017), all the more so given the knowledge that this forms the basis of social and civic cohesion (Rebolledo, 2018). Nevertheless, the evolution of our society has triggered a naturalization of violence as a pattern of everyday interaction (Esteban & Ormart, 2019) from increasingly younger ages (Albaladejo-Blázquez et al., 2013). To this one must add the legitimization, desensitization and indifference to the observation and/or active participation in episodes of this nature (Galán, 2018).

In this respect, it is of relevance to present a conceptual approximation of the term bullying, contextualizing it in the space of a classroom or an educational centre. As such, bullying can be defined as an act of violence (of greater or lesser intensity) carried out repeatedly and intentionally, and characterised by an imbalance of power and force between the aggressor and the victim. Ultimately, it is a clear exercise of moral transgression (Ortega-Ruiz et al., 2016) and harassment against which the student is helpless (Olweus, 1998).

Thus, school bullying, the central topic of this work, is a phenomenon that generates marked concern on an educational, social, familial and personal level (Amnesty International, 2019); and that is extremely difficult to identify and, consequently, to resolve. The prevalence of this problem, as pointed out by Olweus in the eighties, is reflected in international statistics, which indicate that one in every three students between the ages of 13 and 15 years in the world suffer continuous and persistent bullying (Unicef, 2014), 9.3% have suffered traditional bullying in the last two months, and 6.9% are victims of cyberbullying (Save the Children, 2016). For their part, González-Cabrera et al. (2017) state in their study that 6.1% of Spanish students of the age of 15, suffer from school bullying on a regular basis, with the average value of the OECD being even higher (8.9%).

This situation is already affecting even Primary Education students (Wandera et al., 2017), it affects more boys than girls (Han et al., 2017; Olweus, 2009), as well as students from families with low socio-economic and educational levels (Suárez-García et al., 2020) and those whose parents show little participation in educational centres (López & Ramírez, 2020). This panorama is complemented by a review of the alarming statistics of adolescent suicides (Molano et al., 2018); anxiety and depression (Caballo et al., 2011; Pabian & Vandebosh, 2016); avoidance of school attendance (Hutzell & Payne, 2018); low self-esteem, feelings of worry and guilt (Beltrán et al., 2015); self-harm (Carballo & Gómez, 2017); inadequate academic performance (Rettew & Pawlowski, 2016); school absenteeism or outbursts; aggression (Méndez & Cerezo, 2018), etc.

Similarly, from the ways in which bullying is manifested, it is evident that we are dealing with an extremely disparate problem, which includes everything from violent acts, such as insults, to serious physical aggressions. The study of bullying requires the contemplation of three fundamental premises: a) the use of force -verbal, physical or psychological- of the bully against the victim; b) intentionality -a conscious desire to wound, threaten, frighten- and c) repetition -an aggressive act that is repeated over time and that triggers the expectation of future attacks in the victim- (Olweus, 2009). Likewise, with regard to the agents involved, in addition to the bully and the victim, the roles of bullying assistants or reinforcers, that collaborate in or incite the assault, and the defenders or strangers, that defend the victim or remain passive in the face of the assault, should be highlighted (Pöyhönen et al., 2012).

On the other hand, this bullying can take place individually or in a group, have the aim of social exclusion (not allowing the person to participate in activities, ignoring them, etc.), and take place in person or via social networks or other digital means of communication, giving rise to what is known as cyberbullying (García et al., 2020; Pabian & Vandebosch, 2016; Park et al., 2020). In addition to the indicators set out above, the latter phenomenon is further exacerbated by the anonymity of the person carrying out the bullying, and the potential large-scale exposure to an audience, which is often also unknown (Estévez et al., 2020). While it is not the object of investigation in this study, this topic is relevant to the understanding of the different possible modalities of bullying.

Likewise, the axiological system of our Western society is characterised by individualism, competitivity, excessively permissive and undemanding parenting styles, and a culture of minimal effort (Criollo et al., 2020; Gómez et al., 2015), factors that, among others, help to explain the incidence of bullying in our classrooms. It is worth pointing out that both incidences of violence and of bullying can be generated or take place inside or outside the educational centre, with the average age of bullying victims being 10.9 (Ballesteros et al., 2018). These are circumstance that require the implication of the educational community (Grado & Uruñuela, 2017) and of all social agents (Carrascosa & Ortega-Barón, 2018), especially those of the Administration via the offer of resources and supporting structures (Estévez et al., 2018).

In accordance with the above, a proliferation of studies exist that reflect the opinion of the various agents mentioned, on this phenomenon (Esteban & Ormart, 2019). If only for the major repercussions that school bullying can have, it is imperative to continue to explore how it is perceived (on an evaluative level or as a mere spectator) or experienced first-hand. From this stems the need to focus on carrying out studies that give the students themselves a voice (Cava & Buelga, 2018), especially those that are enrolled in Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO), the reason being that this is the educational stage that coincides with pre-adolescence and adolescence. These are evolutionary stages of maximum physiological and socio-affective development (Garaigordobil & Machimbarrena, 2019), as well as being a period of identification and membership of a social group of reference.

For their part, with reference to the analysed content, most of the instruments used for the evaluation of school bullying focus on reviewing the indicators of this bullying (López & Ramírez, 2020; Martínez et al., 2020; Nasywa et al., 2020). Of particular interest to this study, are those that are conducted from the point of view of the observers (Caballo et al., 2012). Among the main research dimensions or factors, the scientific literature includes the following: 1) knowledge, defining characteristics of school bullying and comorbiditgies; 2) guidelines for action when a case of bullying is detected; 3) coexistence at school; 4) inclusion; 5) contexts in which these acts occurs; 6) victimization received; 7) active or passive attitude of the observers; and 8) lack of discipline and laziness on the part of the teacher (Caballo et al., 2012; Caso et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2015; Cuevas & Marmolejo, 2015; Del Rey et al., 2017; López & Ramírez, 2020).

Another of the observed aspects is that the profile of the those that completed the surveys is that of a student in the last few years of Primary Education or in Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO) (Gascón-Cánovas et al., 2016; Ortega-Ruiz et al., 2016; Vera et al., 2017). We also observe that, as yet, there are few studies that explore bullying with a single instrument, and from a first-person perspective (García et al., 2019), or even the reaction towards episodes of bullying (Sokol et al., 2016). The same applies when the sample size of the studies is reviewed, as they are, for the most part, reduced in size and limited to a single centre or institution.

Given the previous premises and arguments, it is pertinent to formulate the objectives of this study in such a way as to be consistent with the design of an instrument that evaluates this construct in an experiential and holistic way (integrating indicators of bullying and examples of bullying that have been observed), focussing on those that have experienced bullying, either as a victim, or as someone who has reacted to an external event. Another objective is to validate the scale on students of Secondary Education centres in Asturias, with the aim of having at our disposal a valid and reliable instrument with which to identify bullying situations in the school environment, both for the role of the victims and that of the witnesses. Specifically, we hope to detect in students certain risk factors that act as predictors to help with the early detection and implementation of formative and informative actions of a psychoeducational nature directed at these students (Moya, 2019). By extension, we hope that this will lead to an improvement in coexistence in a socio-educational (Ortega et al., 2012), familial and community setting (Criollo et al., 2020).

Method

Participants

10795 Compulsory Secondary Education (Educación Secundaria Obligatoria, or ESO) students from eight Asturian municipalities participated in the study. The Executive Plan for Coexistence and the Improvement of Security in Educational Centres and their Surroundings, Instruction 7/2013 of the Secretary of the State of Security (Plan Director para la Convivencia y Mejora de la Seguridad en los Centros Educativos y sus Entornos, Instrucción 7/2013 de la Secretaría de Estado de Seguridad) is being implemented in all of these education centres, and the application of the questionnaires was, in fact, done in collaboration with those in charge of this plan. According to data from the Asturian Ministry of Education and Culture, extracted from the System for the Unified Administration of Educational Centres (SAUCE), there are 23476 ESO students in these municipalities, from which it was estimated that a sample of around 2000 students would be representative. With an error margin of 3% and a confidence level of 99%, the sample should include at least 1709 questionnaires.

Specifically, the sample was distributed among public (54.4%) and semi-private (45.5%) educational centres. As far as the gender variable is concerned, 51.1% were girls and 48.9% were boys, the majority were Spanish nationals (93.2%), the mean age was 13.94 (SD=1.3) and, with regard to the academic year, 26.27% were in their first year of ESO, 27.24% in their second, 25.19% in their third, and 21.30% in their fourth.

Instrument y information gathering procedure

The instrument used (Annex I) is based on the Questionnaire for the Assessment of School Violence in Pre- and Primary School (Cuestionario de Evaluación de Violencia Escolar en Infantil y Primaria, CEVEIP). In its original version (Albaladejo-Blázquez, 2011), it consisted of 36 items divided into 4 dimensions, while in its validation (Albaladejo-Blázquez et al., 2013), this was reduced to 30 items and 3 dimensions (α = .86). The elements of both versions was taken into account, respecting the original dimensions. Specifically, each block includes: 1. Eight behaviours to indicate to what extent they are considered by students to constitute bullying; 2. Eight behaviours to define to what degree they have been witnessed by students in their educational centres; 3. The same eight behaviours to indicate the frequency with which students have been victims; 4. Three proposed actions to deal with these situations. The selection of the items was based on existing literature on the subject, and the wording was simplified after an initial pilot study carried out on one class of each year of Secondary Education, which was not included in the final study. The choice of this instrument is based on a thorough process of elaboration and validation. It has also been developed in a Spanish context, albeit with a limited sample size (195 participants). With respect to the scale employed, a Likert-type scale was used, with values from 1 (never/completely disagree) to 10 (always/totally agree), thus avoiding the tendency to give a central value.

Given that the aim was to get as many completed questionnaires as possible, the computer rooms of the educational centres were used for this purpose, and the questionnaire was carried out via the Google Forms tool (online). Throughout the process, we collaborated with the National Police, who acted as liaisons with the educational centres. The questionnaire was administered during school hours to ensure that any possible doubts could be resolved. Similarly, anonymity was guaranteed, and explicit approval to administer the survey was obtained from the Asturian Ministry of Education after a prior revision (for example, the question referring to the nationality of the student was eliminated to guarantee anonymity).

Data Analysis

First, the database was analysed to check for the absence of missing values and typical cases, and fulfilment of the assumptions for multivariate analysis was tested, with regard to the normal distribution of the items, linearity and the absence of multicollinearity (Pérez & Medrano, 2010). Then, the database was examined to detect any atypical cases or missing values that might skew posterior analyses, and the MCAR test was applied to analyse their behaviour. Subsequently, the degree of compatibility of the items was analysed with a normal curve (analysis of asymmetry and kurtosis). The assumption of linearity was evaluated by examining the scatter plot matrices, observing whether or not the points were distributed along a straight line. Finally, the bivariate inter-item correlations were calculated to determine the degree and direction of the relationships between the items. To avoid problems of multicollinearity, those that did not show an r ≥ .90 were considered to be valid (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001).

The internal consistency and reliability of the questionnaire was established by means of Cronbach’s alpha-coefficient (Cronbach, 1951), which was also calculated for eliminated items.

Analysis of the factorial structure or construct validity was carried out via a process of cross-validation using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), randomly dividing the sample into two. The first subsample was made up of 5404 subjects (50,06% of the sample) and the second of 5391 (49,94% of the sample). For the EFA, the maximum likelihood extraction method was used (Lawley & Maxwell, 1971), since it provides estimates for the parameters that the correlation matrix has produced with the greatest observed likelihood if the sample proceeds from a multivariate normal distribution with m latent factors. This method is the most recommended for large samples (more than 300 subjects) (Ortiz & Fernández-Pera, 2018). In addition, the Promax rotation method was used, since this oblique method was considered to be more effective in the identification of a simple structure (Finch, 2006). For the CFA, a maximum likelihood estimation and a combination of absolute and relative adjustment indices were used to evaluate the goodness of fit of the proposed model. Among the absolute indices, the p-value was used, which is associated with the chi-square statistic and the value of the ratio between χ2 and the degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF), the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Among the relative indices, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Incremental Fit Index (IFI), and the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) were used. For there to be a good fit, the value of CMIN/DF should be lower than 5; that of the GFI should be above .95; The TLI, IFI and CFI values should be greater than .90, with values above .95 considered excellent; and the values of RMSEA and SRMR lower than .08.

To check whether the model stays stable when the variables gender, academic year and classification of the centre are taken into consideration, confirmatory factor analyses were carried out on the subsamples of students of public (n = 5886) and semi-private (n = 4909) schools, female (n = 5519) and male (n = 5276) genders, and the four academic years of ESO (n = 2836 in first, n = 2941 in second, n = 2719 in third and n = 2299 in fourth year). Given that the model was expected to demonstrate a good fit in all cases, multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA) was used to test its factorial invariance as a function of these variables. The analysis was carried out via the successive addition of models, each one more restrictive than the previous one: First, configural invariance (the factor structure is the same across groups) was tested (M1); then, metric or weak invariance (factor loadings are constrained to be equal) was considered (M2); after which strong invariance (factor loadings and intercepts constrained to be equal) was evaluated (M3); and finally, a strict invariance model was tested (constraining factor loadings, intercepts and residual variances to be equal) (M4). The indicator used to confirm that the models remained invariant was that the difference between the CFIs of successive levels of invariance be equal or inferior to .01, and that the difference in the RMSEA be equal or inferior to .015 (Chen, 2007). The value of χ2 was also calculated but, due to its sensitivity to the sample size, it was not taken into account. Finally, if strict invariance exists, the observed changes will be attributed to the latent variables, and not to a measurement bias (DeShon, 2004).

The AMOS 22.0 module of the statistical software package SPSS 22.0 was used for the analysis of the collected data.

Results

The initial questionnaire, made up of 27 items, demonstrated a high degree of reliability (α = .86). The percentage of missing values was between .0% and .1%, and the results obtained in the MCAR test were χ2 = 252.767, DF = 179, α = .000, from which it can be concluded that the missing data are not MCAR (missing completely at random). The EM (Expectation-Maximization) estimation therefore had to be applied, using the Missing Values Analysis module of the program SPSS, since this procedure has distinct advantages in applied contexts (Van Ginkel & Van der Ark, 2005).

The means, standard deviation and normalcy indices of the 27 items of the questionnaire are given in Table 1. It can be seen that all values were below 2 for asymmetry, and below 7 for kurtosis, with the exception of the items “I get beat up in class or at break times”, “My schoolwork is destroyed”, “I receive offensive, insulting or threatening messages via social media” and “Offensive or mocking photos and videos of me are published on the Internet to offend or laugh at me.” This indicates that these items should be excluded from the analysis. However, given the importance awarded to these items in the literature, we decided to take the risk of not eliminating them in order to avoid losing important information, as we believe the elevated asymmetry and kurtosis to be the result of a low occurrence of these behaviours.

TABLE 1. Descriptive statistics and univariate normality of the items of the original questionnaire

|

Items |

M |

SD |

Asymmetry |

Kurtosis |

|

1.Insulting someone |

6.14 |

2.63 |

-.25 |

-.84 |

|

2.Hitting someone |

7.94 |

2.76 |

-1.35 |

.68 |

|

3.Pushing someone |

6.24 |

2.71 |

-.40 |

-.84 |

|

4.Bothering someone to prevent them from doing their work |

5.80 |

2.81 |

-.21 |

-1.01 |

|

5.Taking away or hiding things from someone |

5.94 |

2.85 |

-.24 |

-1.05 |

|

6.Isolating or ignoring someone |

7.41 |

3.01 |

-1.02 |

-.27 |

|

7.Calling someone names |

6.13 |

2.91 |

-.32 |

-1.05 |

|

8.Laughing at someone |

6.68 |

2.91 |

-.57 |

-.83 |

|

9.Insulting someone in class or at break times |

4.79 |

2.81 |

.25 |

-1.07 |

|

10.Hitting someone in class or at break times |

3.50 |

2.76 |

.96 |

-.24 |

|

11.Ignoring or marginalising someone in class or at break times |

4.25 |

3.02 |

.50 |

-1.07 |

|

12.Bothering someone, not allowing them to do their work or destroying it |

3.70 |

2.86 |

.79 |

-.63 |

|

13.Taking away or hiding things from someone |

4.78 |

3.05 |

.29 |

-1.23 |

|

14.Taking videos or photos with a mobile phone to make fun of or ridicule someone |

3.10 |

2.91 |

1.21 |

.11 |

|

15.Sending offensive, insulting or threatening messages to someone via social media |

3.23 |

2.97 |

1.11 |

-.18 |

|

16.Publishing offensive or mocking photos and videos or someone on the Internet |

2.71 |

2.78 |

1.56 |

1.10 |

|

17.I am insulted in class or at break times |

2.07 |

1.99 |

2.25 |

4.68 |

|

18.I get beat up in class or at break times |

1.39 |

1.29 |

4.42 |

21.55 |

|

19.I am ignored or marginalised in class or at break times |

1.66 |

1.72 |

3.15 |

9.87 |

|

20.I am bothered and/or not allowed to do my work |

2.04 |

1.94 |

2.32 |

5.12 |

|

21.My things are taken away or hidden from me. |

2.08 |

2.01 |

2.29 |

4.89 |

|

22. My schoolwork is destroyed |

1.43 |

1.37 |

4.06 |

17.96 |

|

23.I receive offensive, insulting or threatening messages via social media |

1.39 |

1.38 |

4.32 |

19.68 |

|

24.Offensive or mocking photos and videos of me are published on the Internet to offend or laugh at me. |

1.29 |

1.20 |

5.25 |

29.83 |

|

25.Telling a teacher |

5.64 |

3.24 |

-.05 |

-1.37 |

|

26.Telling your family |

5.95 |

3.47 |

-.20 |

-1.49 |

|

27.Not doing anything |

3.34 |

2.94 |

1.03 |

-.25 |

No correlations of above .90 were observed between items, which indicates that problems of multicollinearity can be ruled out.

From the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) performed on the first subsample (n1 = 5404), four factors were obtained that explained 51.25% of the variance. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy gives a value of .89, which is considered to be between “commendable” and “very good” (Kaiser, 1974), and the Bartlett test of sphericity was significant (c2 = 73479.720; DF = 351; p = .000). All 27 items were maintained, since no communalities below .40, factor loadings lower than .40, or equal or superior to .40 in more than one factor, were found.

The resulting factors were named “Behaviours that are considered bullying” (F1), “Bullying behaviours witnessed” (F2), “Bullying behaviours suffered” (F3) and “Reaction to bullying behaviours” (F4), and they explain 23.13%, 14.97%, 7.97% and 5.18% of the variance, respectively. The factor saturation of each item is shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2. Factorial structure of the questionnaire

|

Items |

Factor |

|||

|

F1 |

F2 |

F3 |

F4 |

|

|

Item1 |

.806 |

|||

|

Item2 |

.786 |

|||

|

Item3 |

.783 |

|||

|

Item4 |

.739 |

|||

|

Item5 |

.729 |

|||

|

Item6 |

.715 |

|||

|

Item7 |

.672 |

|||

|

Item8 |

.661 |

|||

|

Item9 |

.784 |

|||

|

Item10 |

.784 |

|||

|

Item11 |

.759 |

|||

|

Item12 |

.755 |

|||

|

Item13 |

.730 |

|||

|

Item14 |

.700 |

|||

|

Item15 |

.674 |

|||

|

Item16 |

.643 |

|||

|

Item17 |

.730 |

|||

|

Item18 |

.726 |

|||

|

Item19 |

.707 |

|||

|

Item20 |

.693 |

|||

|

Item21 |

.647 |

|||

|

Item22 |

.634 |

|||

|

Item23 |

.629 |

|||

|

Item24 |

.608 |

|||

|

Item25 |

.791 |

|||

|

Item26 |

.759 |

|||

|

Item27 |

.504 |

|||

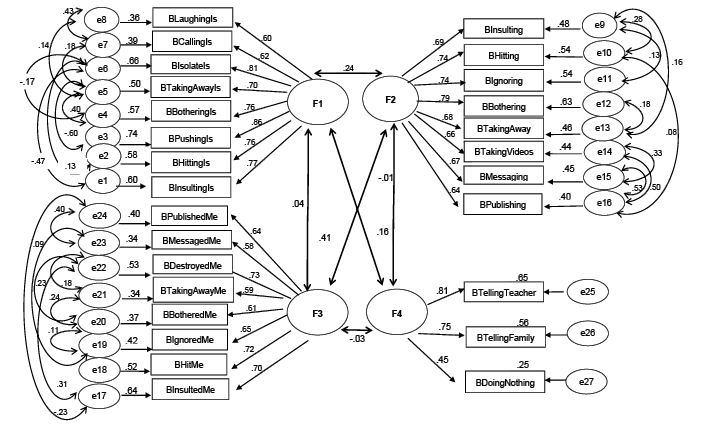

The values obtained from the confirmatory factor analysis of the second subsample (n2 = 5391) indicate an optimal fit of the model, and a significant chi-square value was obtained (χ2 = 3382.209, DF = 294, p < .000), a CMIN/DF = 11.504 (bearing in mind that this index is highly sensitive to the sample size), as well as the following values for the calculated indices: GFI = .955, RMSEA = .044, SRMR = .038, CFI = .958, IFI = .958 y TLI = .950. Figure 1 shows the parameters of the standardized solution.

FIGURE 1. Confirmatory factor analysis (Subsample 2)

The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of the entire set of items was .86, and that of the resulting factors was .91 (F1), .90 (F2), .86 (F3) and .72 (F4), values considered to be between very good and average.

The obtained results show that the factorial structure of the APAE-A Scale is invariant with regard to the variables “classification”, “gender” and “academic year” (Table 3), meeting the established criteria.

TABLE 3. Fit indices for the entire sample, classification, gender, and academic year

|

Sample |

χ2 |

DF |

GFI |

RMSEA |

SRMR |

CFI |

IFI |

TLI |

|

Overall |

6459.990 |

294 |

.957 |

.044 |

.038 |

.958 |

.958 |

.950 |

|

Public |

3665.445 |

294 |

.956 |

.044 |

.038 |

.960 |

.960 |

.952 |

|

Semi-private |

3256.911 |

294 |

.9553 |

.045 |

.039 |

.953 |

.953 |

.943 |

|

Female |

3443.668 |

294 |

.958 |

.044 |

.037 |

.958 |

.958 |

.958 |

|

Male |

3469.606 |

294 |

.956 |

.045 |

.040 |

.956 |

.956 |

.947 |

|

First year ESO |

2052.184 |

294 |

.949 |

.046 |

.042 |

.957 |

.957 |

.949 |

|

Second year ESO |

1836.848 |

294 |

.956 |

.042 |

.036 |

.958 |

.958 |

.950 |

|

Third year ESO |

1969.364 |

294 |

.946 |

.047 |

.042 |

.953 |

.953 |

.944 |

|

Fourth year ESO |

1820.253 |

294 |

.943 |

.048 |

.043 |

.952 |

.952 |

.943 |

χ2 = Chi-Squared; DF = Degrees of Freedom; GFI- The Goodness of Fit Index (p ≥ .90); RMSEA- Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (p ≤ .08); SRMR- Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (p ≤ .08); CFI- Comparative Fit Index (p ≥ .95); IFI- Incremental Fit Index (p ≥ .95); TLI- Tucker Lewis Index (p ≥ .95).

Given that the single-factor model demonstrates an optimal fit for all the subgroups, a multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA) was used to test its factorial invariance as a function of the three indicated variables. The results are shown in Table 4.

TABLE 4. Goodness of fit indices of each model tested for factorial invariance with respect to classification, gender and academic year

|

Model |

χ2 |

DF |

CFI |

∆CFI |

RMSEA |

∆RMSEA |

|

Classification |

||||||

|

M1 |

6922,360 |

588 |

,957 |

,032 |

||

|

M2 |

7146,164 |

611 |

,955 |

-.002 |

,031 |

-.001 |

|

M3 |

7328,654 |

621 |

,954 |

-.001 |

,032 |

.001 |

|

M4 |

7641,927 |

672 |

,952 |

-.002 |

,031 |

-.001 |

|

Gender |

||||||

|

M1 |

6913,275 |

588 |

,957 |

,032 |

||

|

M2 |

7383,566 |

611 |

,954 |

-.003 |

,032 |

.000 |

|

M3 |

7539,877 |

621 |

,953 |

-.001 |

,032 |

.000 |

|

M4 |

9663,798 |

672 |

,939 |

-.014 |

,035 |

-.003 |

|

Academic Year |

||||||

|

M1 |

7714,860 |

1176 |

,955 |

,023 |

||

|

M2 |

7994,188 |

1245 |

,954 |

-.001 |

,022 |

-.001 |

|

M3 |

8189,132 |

1275 |

,953 |

-.001 |

,022 |

.000 |

|

M4 |

9785,459 |

1428 |

,943 |

-.010 |

,023 |

.001 |

M1. Configural invariance; M2. Metric invariance; M3. Strong invariance; M4. Strict invariance; χ2 = Chi-Squared; DF = Degrees of Freedom; CFI- Comparative Fit Index, ∆CFI: Increase in CFI; RMSEA = Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation; ∆RMSEA: Increase in RMSEA.

The results of the configural invariance analysis (M1) demonstrate adequate fit indices, which indicates that the factorial structure of the scale remained invariable in all the groups compared. This model was considered to be a starting point for further analyses with greater restrictions. The results of the configural invariance analysis (M2) also show adequate fit indices, with values very similar to those obtained in M1, and that met the established criteria (ΔRMSEA< .015, ΔCFI< .01), indicating that there was no difference between the base-line model (M1) and the restrictive model M2. The fit indices also demonstrated an acceptable fit for Model 3 (M3), in which strong invariance was analysed, as none exceeded the established criteria for incremental values. In Model 4 (M4), acceptable fit indices that met the established criteria where also obtained, which demonstrates residual or strict invariance with respect to all three analysed variables.

Discussion and Conclusions

The complexity that the study of school bullying involves is equalled by the socio-educational importance of its effects (Díaz-Aguado et al., 2013; Martín, 2020). For this reason, the educational system has focussed its attention on teaching and promoting peaceful coexistence in schools, seeing this as a construct which is closely linked to bullying. Furthermore, thanks to and by means of an exercise in socialization, a series of norms, values and positive behaviours befitting a democratic, egalitarian and non-violent society, are transmitted and interiorized (García et al., 2019; López & Ramírez, 2020).

Nevertheless, it is precisely in these school environments that conflictive episodes are bred and take place, episodes characterized by abuse among equals, carried out intentionally and systematically on a psychological and/or physical level, in person or digitally (Grado & Uruñuela, 2017). As a consequence, early detection is essential to avoid the emergence of school bullying behaviours, as well as to avoid these events being hidden, becoming chronic, or being reinforced by the peer group (Garaigordobil & Machimbarrena, 2019; Sánchez & Cerezo, 2014). It is precisely in this context that the existence of instruments to compile information on this subject is fundamental (Caballo et al., 2012; Vera et al., 2017), and many assessment scales for school and cyberbullying exist on an international level.

One of the main contributions that this study makes is therefore the sample size on which the scale was validated (10795 students), which is, furthermore, representative of the general population. While it does not come close to the numbers of studies like those of González González-Cabrera et al. (2017) and Díaz-Aguado et al. (2013), with n = 27913 and n = 23100 respectively, this work by far exceed the volumes achieved in other research studies on the subject: 1217 (Thomas et al., 2019), 703 (Guimaraes et al., 2016), 600 (Harbin et al., 2017), 494 (García et al., 2020), 352 (Strout et al., 2018) o 100 (Chan & Márquez, 2020). In addition, we aimed to ensure heterogeneity in terms of the participants of the study, taking into account aspects such as the municipality of residence and the year of Secondary Education, a stage in which this phenomenon is observed with greater frequency and seriousness (Ruiz-Narezo et al., 2020).

On the other hand, the reliability of the Scale for Self-Perception and Perception of School Bullying in Adolescents (Escala de Autopercepción y Percepción del Acoso Escolar en Adolescentes, APAE-A) was verified for an educational stage different from that used in the CEVEIP (Albadalejo-Blázquez et al., 2013). This scale is made up of 27 items divided into four factors that provide valid and reliable measures of school bullying, a structure that allows it to be completed quickly and easily. This is precisely what makes it so useful for the empirical research contexts of a problem such as bullying, which is not only multifactorial, but often also camouflaged and silent. In the same sense, another one of the instrument’s strengths lies in its reliability, both on a global level (α = .86), and for each factor, with values above .90 in those factors that relate to behaviours that are considered bullying and bullying behaviours witnessed (F1 and F2), very close to .90 for bullying behaviours experienced (F3), and .72 for reactions to bullying (F4).

Likewise, its psychometric properties, together with its excellent internal consistency (reliability), suggest that it is an ideal tool for research, diagnosis and intervention in a range of related fields and disciplines, such as education, psychology and psychopedagogy, all the more so since it has been corroborated that this is a phenomenon that originates in the school environment, but is not restricted to it (Esteban & Ormart, 2019).

With regard to the factorial structure of the scale, we can corroborate that the main dimensions contemplated in other related studies have been included: a) identification of behaviours that are considered bullying (Chan & Márquez, 2020); b) observation of violent behaviours (Caballo et al., 2012; Dobarro et al., 2018); c) victimization received (Gascón-Cánovas et al., 2016; Núñez et al., 2021; Suárez-García et al., 2020) and d) reaction and actions (measures) taken when faced with situations of bullying (López & Ramírez, 2020). Nevertheless, the main potential of the present instrument when compared to other scales with similar factors (Del Rey et al., 2017; Gascón-Cánovas et al., 2016; Hutzell & Payne, 2018; Nasywa et al., 2020; Ortega-Ruiz, et al., 2016; Peraza-Balderrama et al., 2021), is its holistic approach, that is, integrating into a single test dimensions that are usually studied independently or, at best, separately: 1) bullying behaviour; 2) witnessing bullying behaviour (frequency); 3) being a victim of bullying (frequency) and 4) the reaction to violent behaviour.

The limitations of this study include its independent implementation, although this is counteracted by the representation of the population, which facilitates the extrapolation of the findings. With regard to future lines of work, we highlight an interest in complementing the results with qualitative information compiled, for example, via in-depth interviews or discussion groups set up for students. It would also be of interest to consult the collective of families and teachers on the same questions that the students were asked, to find out if they are aware of the occurrence of these conflictive episodes, as well as to obtain information about their attitudes and measures taken. On the other hand, we also advocate replicating the study in later educational stages, or even in the last years of Primary Education. Likewise, both as a limitation and as a future line of research, it would be of interest to administer other similar questionnaires, in order to analyse the concurrent validity of the scale.

Ultimately, the preventative approach and the psychopedagogical response to bullying requires a joint ecological effort (Espelage, 2014) of the various microsystems (community environment, educational centre and family) that the student is part of (Sánchez & Blanco, 2017). At the same time, this needs to be built on a prior empirical base that is rigorous, solid and reliable, and that can provide information on the specific state of the matter (Nocito, 2017). Thus, the configuration of the APAE-A Scale attempts to make a contribution in this respect, one which will result in and contribute to the design and execution of evidence-based plans and programs that contribute to personal, social, family and work integration (Salgado et al., 2014), serve as a positive response to conflict and promote a peaceful coexistence with benefits that extend to the entire educational community (Prati et al., 2017) and thereby also to society as a whole.

References

Albaladejo-Blázquez, N. (2011). Evaluación de la violencia escolar en educación infantil y primaria [Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Alicante].

Albaladejo-Blázquez, N., Ferrer-Cascales, R., Reig-Ferrer, A. y Fernández-Pascual, M. D. (2013). ¿Existe Violencia Escolar en Educación Infantil y Primaria? Una propuesta para su evaluación y gestión. Anales de Psicología, 29(3), 1060-1069. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.3.158431

Amnistía Internacional. (2019). Hacer la vista… ¡gorda!: El acoso escolar en España, un asunto de derechos humanos. Amnistía Internacional.

Ballesteros, B. (Coord.), Pérez de Viñaspre, S., Díaz, D. y Toledano, E. (2018). III Estudio sobre acoso escolar y ciberbullying según los afectados. Fundación Mutua Madrileña y Fundación ANAR.

Beltrán, M., Zych, I. y Ortega, R. (2015). El papel de las emociones y el apoyo percibido en el proceso de superación de los efectos del acoso escolar: un estudio retrospectivo. Ansiedad y Estrés, 21(2-3), 219-232.

Caballo, V. E., Arias, B., Calderero, M., Salazar, I. C. y Irurtia, M. J. (2011). Acoso escolar y ansiedad social en niños (I): análisis de su relación y desarrollo de nuevos instrumentos de evaluación. Behavioral Psychology/Psicología Conductual, (19), 501-609.

Caballo, V. E., Calderero, M., Arias, B., Salazar, I. C. y Irurtia, M. J. (2012). Desarrollo y validación de una nueva media de autoinforme para evaluar el acoso escolar (Bullying). Behavioral Psychology, 20(3), 625-647.

Carballo, J. y Gómez, J. (2017). Relación entre el bullying, autolesiones, ideación suicida e intentos autolíticos en niños y adolescentes. Revista de Estudios de Juventud, (115), 207-218.

Carrascosa, L. y Ortega-Barón, J. (2018). Apoyo social, empatía y satisfacción con la vida en los diferentes roles de agresor-víctima de acoso escolar. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology. INFAD Revista de Psicología, Monográfico 2, 1(3), 71-78. https://doi.org/10.17060/ijodaep.2018.n1.v3.1221

Caso, J., Díaz, C. y Chaparro, A. A. (2013). Aplicación de un procedimiento para la optimización de la medida de la convivencia escolar. Revista Iberoamericana de Evaluación Educativa, 6(2), 137-145.

Cava, M. J. y Buelga, S. (2018). Propiedades Psicométricas de la Escala de Victimización Escolar entre Iguales -VE-I-. Revista Evaluar, 18(1), 40-53.

Chan, J. G. y Márquez, K. N. (2020). Propiedades psicométricas, resultados y uso de la escala de violencia escolar y bullying: cómo distinguir el bullying y la violencia escolar. Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztacala, 23(3), 984-1014.

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indices to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, (14), 464-504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Cohen, J., Espelage, D. L., Twemlow, S. W., Berkowitz, M. W. y Comer, J. P. (2015). Rethinking Effective Bully and Violence Prevention Efforts: Promoting Healthy School Climates, Positive Youth Development and Preventing Bully-Victim-Bystander Behavior. International Journal of Violence and Schools, (15), 2-40.

Criollo, M. I., Moreno, R. P., Ramón, B. L. y Cango, A. E. (2020). Factores familiares, comunitarios y escolares que influyen en el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes. Polo del Conocimiento: Revista Científico-Profesional, 5(1), 622-646. https://doi.org/10.23857/pc.v5i01.1241

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of test. Psycometrika, (16), 297-334. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02310555

Cuevas, M. y Marmolejo, M. (2015). Observadores: un rol determinante en el acoso escolar. Pensamiento Psicológico, 14(1), 89-102.

Del Rey, R., Casas, J. A. y Ortega, R. (2017). Desarrollo y validación de la escala de convivencia escolar (ECE). Universitas Psychologica, 16(1), 1-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy16-1.dvec

DeShon, R. P. (2004). Measures are not invariant across groups without error variance homogeneity. Psychology Science, 46(1), 137-149.

Díaz-Aguado, M. J., Martínez, R. y Martín, J. M. (2013). El acoso entre adolescentes en España. Prevalencia, papeles adoptados por todo el grupo y características a las que atribuyen la victimización. Revista de Educación, (362), 348-379. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2011-362-164

Dobarro, A., Tuero, E., Bernardo, A. B., Herrero, F. J. y Álvarez-García, D. (2018). Un estudio innovador sobre acoso on-line en estudiantes universitarios. Revista d’Innovació Docent Universitària, (10), 131-142. https://dx.doi.org/10.1344/RIDU2018.10.12

secundarias venezolanas desde el reporte de víctimas y perpretadores. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 16(31), 15-28.

Espelage, D. (2014). Ecological theory: preventing youth bullying, aggression and victimization. Theory Into Practice, 53(4), 257-264. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2014.947216

Esteban, O. y Ormart, E. (2019). Violencia escolar y planificación educativa. Nodos y Nudos, 6(46), 13-26. https://doi.org/10.17227/nyn.vol6.num46-9685

Estévez, J. F., Cañas, E., y Estévez, E. (2020). The impact of cybervictimization on psychological adjustment in adolescence: Analyzing the role of emotional intelligence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3693. https://www.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103693

Estévez, E., Jiménez, T. I. y Moreno, D. (2018). Aggressive behavior in adolescence as a predictor of personal, family and school adjustment problems. Psicothema, 30(1), 66-73. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.294

Finch, H. (2006). Comparison of the Performance of Varimax and Promax Rotations: Factor Structure Recovery for Dichotomous Ítems. Journal of Educational Measurement, 43, 39-52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3984.2006.00003.x

Galán, J. S. (2018). Exposición a la violencia en adolescentes: desensibilización, legitimación y naturalización. Revista Diversitas, Perspectivas en Psicología, 14(1), 55-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.15332/s1794-9998.2018.0001.04

Garaigordobil, M. y Machimbarrena, J. (2019). Victimization and Perpetration of Bullying/Cyberbullying: Connections with Emotional and Behavioral Problems and Childhood Stress. Psychosocial Intervention, 28(2), 67-73. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a3

García, M., Fernández, N., Fernández, A. A. y España, C. (2019). ¿Qué se puede hacer para mejorar la convivencia en secundaria? La voz del alumnado. Revista de Sociología de la Educación-RASE-, 12(1), 63-73. https://doi.org/10.7203/RASE.12.1.13213

García, L., Quintana, C. y Rey, L. (2020). Cibervictimización y satisfacción vital en adolescentes: la inteligencia emocional como variable mediadora. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes, 7(1), 38-45. https://doi.org/10.21134/rpcna.2020.07.1.5

Gascón-Cánovas, J. J., Russo, J. R., Cózar, A. y Heredia, J. M. (2016). Adaptación cultural al español y baremación del Adolescent Peer Relations Instrument (APRI) para la detección de la victimización por acoso escolar: estudio preliminar de las propiedades psicométricas. Anales de Pediatría, (87), 9-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anpedi.2015.12.003

Gómez, O., Del Rey, R., Romera, E. M. y Ortega, R. (2015). Los estilos educativos paternos y maternos en la adolescencia y su relación con la resiliencia, el apego y la implicación en el acoso escolar. Anales de Psicología, 31(3), 449-456. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.3.180791

Gómez-Ortiz, O., Romera, E. M. y Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2017). La competencia para gestionar las emociones y la vida social y su relación con el fenómeno del acoso y la convivencia escolar. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 88(31.1), 27-38.

González-Cabrera, J. (Coord.), Balea, A., Vallina, M., Moya, A. y Laviana, F. O. (2017). Informe ejecutivo del Proyecto Ciberastur. Universidad Internacional de la Rioja (UNIR) y Consejería de Educación y Cultura del Principado de Asturias. Recuperado de https://bit.ly/3x6yW5L n

Grado, A. y Uruñuela, P. (2017). Los tipos de violencia que aparecen en la escuela. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, 480, 10-14.

Guimaraes, F., Heldt, E., Peixoto, B. N., Adamati, G., Filipetto, M. y Pinto, L. S. (2016). Construct validity and reability of Olweus bully/victim questionnaire-Brazilian version. Psicología: Reflexao e Crítica, 29(27), 1-8. http://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-016-0019-7

Han, Z., Zhang, G. y Zhang, H. (2017). School bullying in urban China: Prevalence and correlation with school climate. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(10), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14101116

Harbin, S. M., Kelley, M. L., Piscitello, J. y Walker, S. J. (2017). Multidimensional bullying victimization scale: development and validation. Journal of School Violence, 18(1), 146-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2017.1423491

Herrera-Espinoza, V. S. y Cerezo-Ochoa, V. R. (2018). Derechos Humanos y Educación. Revista Publicando, 5(14), 645-653.

Hutzell, K. L. y Payne, A. A. (2018). The relationship between bullying victimization and school avoidance: An examination of direct associations, protective influences, and aggravating factors. Journal of School Violence, 17(2), 210-226. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2017.1296771

Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39, 31-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02291575

Lawley, D. N. y Maxwell, A. E. (1971). Factor analysis as a statistical method. Butterworths.

López, L. y Ramírez, A. (2020). Acoso e inconvivencia escolar: el rol de la participación familiar en los centros educativos. Campo Abierto, 39(1), 55-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.17398/0213- 9529.3 9.1.55

Martín, T. M. (2020). La familia y la escuela, agentes primordiales para promover la convivencia escolar. Intervención psicoeducativa en la desadaptación social: IPSE-ds, (13), 11-31.

Martínez, J. P., Méndez, I., Ruíz-Esteban, C. y Cerezo, F. (2020). Validación y fiabilidad del Cuestionario sobre Acoso entre Estudiantes Universitarios (QAEU). Revista Fuentes, 22(1), 8-104. https://doi.org/10.12795/revistafuentes.2020.v22.i1.08

Méndez, I. y Cerezo, F. (2018). La repetición escolar en Educación Secundaria y factores de riesgo asociados. Educación XX1: Revista de la Facultad de Educación, 21(1), 41-62. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.20172

Molano, A., Harker, A. y Cristancho, J. C. (2018). Effects of indirect exposure to homicide events on children’s mental health: evidence form urban settings in Colombia. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, (47), 2060-2072. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0876-8

Moya, M. (2019). Educar en la empatía: el antídoto contra el bullying. Plataforma Editorial.

Nasywa, N., Tentama, F. y Mujidin, M. (2020). Testing the Validity and Reability of the Cyberbullying Scale. American Research Journal of Humanities Social Sciences (ARJHSS), 3(6), 132-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpal.2016.02.003

Nocito, G. (2017). Investigaciones sobre el acoso escolar en España: implicaciones psicoeducativas. Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía, 28(1), 104-118.

Núñez, A., Álvarez-García, D. y Pérez-Fuentes, M. C. (2021). Anxiety and self-esteem in cyber-victimization profiles of adolescents. Comunicar, 29(67), 47-59. https://doi.org/10.3916/C67-2021-04

Olweus, D. (1998). Conductas de acoso y amenaza entre escolares. Ediciones Morata.

Olweus, D. (2009). Understanding and researching bullying. Some critical issues. In S. Jimerson, S. Swearer & D. L. Espelage (Eds.). Handbook of bulluing in schools. An international perspective (pp. 9-33). Routledge.

Ortega-Ruiz, R., Del Rey, R. y Casas, J. A. (2016). Evaluar el bullying y el cyberbullying: validación española del EBIP-Q y del ECIP-Q. Psicología Educativa, (22), 71-79. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pse.2016.01.004

Ortega, R., Del Rey, R. y Sánchez, V. (2012). Nuevas dimensiones de la convivencia escolar y juvenil. Ciberconducta y relaciones en la red: Ciberconvivencia. Ministerio de Educación Cultura y Deporte.

Ortiz, M. S. y Fernández-Pera, M. (2018). Modelo de Ecuaciones Estructurales: Una guía para ciencias médicas y ciencias de la salud. Terapia Psicológica, 36(1), 47-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/s0718-48082017000300047

Pabian, S. y Vandebosch, H. (2016). Short-term longitudinal relationships between adolescents’ (cyber)bullying perpetration and bonding to school and teachers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40(2), 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415573639

Park, H.S., Gyeong, Y. S. y Sook, K. J. (2020). Damage Experiences on Cyberbullying and Moderating Effect of Implulsivity and Family Cohesion. The Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 11(3), 345-360.

Peraza-Balderrama, J. N., Valdés-Cuervo, A. A., Martínez-Ferrer, B., Reyes-Rodríguez, A. C. y Parra-Pérez, L. G. (2021). Assessment of a multidimensional school collective efficacy scale to prevent student bullying: examining dimensionality and measurement invariance. Psychosocial Intervention, 30(2), 101-111. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2021a2

Pérez, E. R. y Medrano, L. (2010). Análisis Factorial Exploratorio: Bases Conceptuales y Metodológicas. Revista Argentina de Ciencias del Comportamiento, 2(1), 58-66.

Pöyhönen, V., Juvonen, J., y Salmivalli, C. (2012). Standing up for the victim, siding with the bully or standing by? Bystander responses in bullying situations. Social Development, 21(4), 722-741.

Prati, G., Cicognani, E. y Albanesi, C. (2017). Psychometric properties of multidimensional scale of sense of community in the school. Frontiers in Psychology, (8), e1488, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01466

Rebolledo, T. (2018). Retos formativos de la Educación Social para la intervención en contextos de diversidad. En-clave pedagógica: Revista Internacional de Investigación e Innovación Educativa, (14), 45-49.

Rettew, D. C. y Pawlowski, S. (2016). Bullying. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 25(2), 235-242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2015.12.002

Ruiz-Narezo, M., Santibáñez, R. y Laespada, M. T. (2020). Acoso escolar: adolescentes víctimas y agresores. La implicación en ciclos de violencia. Bordón. Revista de Pedagogía, 72(1), 117-132. https://doi.org/10.13042/Bordon.2020.71909

Salgado, F., Senra, L. y Lourenco, L. (2014). Effectiveness indicators of bullying intervention programs: A systematic review of the international literature. Estudios de Psicología (Campinas), 31(2), 179-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0103-166x214000200004

Sánchez, G. y Blanco, J. L. (2017). El “Buentrato”, programa de prevención del acoso escolar, otros tipos de violencia y dificultades de relación. Una experiencia de éxito con alumnos, profesores y familia. Revista de Estudios de Juventud, (115), 115-136.

Sánchez, C. y Cerezo, F. (2014). Conceptualización del bullying y pautas de intervención en educación primaria. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology: INFAD. Revista de Psicología, 6(1), 443-452.

Save the Children (2016). Yo a eso no juego. Bullying y ciberbullying. Recuperado de https://bit.ly/3zAIN5E

Secretaría de Estado de Seguridad. (2013). Instrucción 7/2013 de la Secretaría de Estado de Seguridad. https://bit.ly/3sCTwsp

Sokol, N., Bussey, K. y Rapee, R. (2016). The impact of victims´ response on teacher reactions to bullying. Teaching and Teacher Education, (55), 78-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.11.002

Strout, T. D., Vessey, J. A.; Difrazio, R. L. y Ludlow, L. H. (2018). The child adolescent bullying Scale (CABS): Psychometric evaluation of a new measure. Research in Nursering & Health, (41), 252-264. http://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21871

Suárez-García, Z., Álvarez-García, D. y Rodríguez, C. (2020). Predictores de ser víctima de acoso escolar en Educación Primaria: una revisión sistemática. Revista de Psicología y Educación, 15(1), 1-15, https://doi.org/10.23923/rpye2020.01.182

Tabachnick, B. G. y Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics. Pearson.

Thomas, H. J., Scott, J. G., Coates, J. M. y Connor, J. P. (2019). Development and validation of the bullying and cyberbullying scale for adolescents: a multidimensional measurement model. British Journal of Educational Psychology, (89), 75-94. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.1222

UNICEF. (2014). Hidden in plain sight. A statistical analysis of violence against children. UNICEF.

Van Ginkel, J. R. y Van der Ark, L. A. (2005). SPSS syntax for missing value imputation in test and questionnaire data. Applied Psychological Measurement, 29(2), 152-153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146621603260688

Vera, C. Y., Vélez, C. M. y García, H. I. (2017). Mediación del bullying escolar: Inventario de instrumentos disponibles en idioma español. Psiencia. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencia Psicológica, (9), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.5872/psiencia/9.1.31

Wandera, S. O., Clarke, K., Knight, L., Allen, E., Walakira, E., Namy, S., Naker, D. y Devries, K. (2017). Violence against children perpetrated by peers: A cross-sectional school-based survey in Uganda. Child Abuse & Neglect, (68), 65-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.006

Contact address: Antonio Urbano Contreras, Universidad de Oviedo, Facultad de Formación del Profesorado y Educación, Departamento de Ciencias de la Educación. C/ Aniceto Sela S/N, CP 33005, Oviedo, Asturias. E-mail: urbanoantonio@uniovi.es

Annex 1

Scale for Self-Perception and Perception of School Bullying in Adolescents (APAE-A)

Below, we present you with a series of statements, so that you can indicate your opinion or to what degree you agree. You can answer freely and honestly, since the questionnaire is anonymous.

1) Name of the school: 2) Year:

3) Gender: __Male __Female 4) Age:

5) How many years have you repeated up to now (0, 1, 2…)?:

6) Father’s level of studies:

__No studies __Compulsory Secondary Education __A-levels/Professional Training __University

7) Mother’s level of studies:

__No studies __Compulsory Secondary Education __A-levels/Professional Training __University

8) I live with:

__My mother and father __Only my mother __My mother and her partner

__Only with my father __My father and his partner __With my aunts and uncles, or grandparents

__Others (Who?):

9) How many brothers and sisters do you have?:

10) How many of your brothers and sisters live at home?:

11) Who works outside of home?:

__My father __Mi mother __Someone else __No-one

12) I think I will reach an educational level of:

__Compulsory Secondary Education __Professional Training (middle-grade) __University Studies

__A-levels __Professional Training (higher-grade) __None

__Other (What?):

|

To what degree do you consider the following behaviours to be school bullying? (1 means “Not at all” and 10 means “A lot”) |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Insulting someone |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Hitting someone |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Pushing someone |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Bothering someone to prevent them from doing their work |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Taking away or hiding things from someone |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Isolating or ignoring someone |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Calling someone names |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Laughing at someone |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

How often have you witnessed someone doing these things to a classmate or another student? (1 means “Never” and 10 means “Always”) |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Insulting someone in class or at break times |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Hitting someone in class or at break times |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Ignoring or marginalising someone in class or at break times |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Bothering someone, not allowing them to do their work or destroying it |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Taking away or hiding things from someone |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Taking videos or photos with the mobile phone to make fun of or ridicule someone |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Sending offensive, insulting or threatening messages to someone via social media |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Publishing offensive or mocking photos and videos of someone on the Internet |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

How often have your classmates or other students done things like this to you? (1 means “Never” and 10 means “Always”) |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

17.I am insulted in class or at break times |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

18.I get beat up in class or at break times |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

19.I am ignored or marginalised in class or at break times |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

20.I am bothered and/or not allowed to do my work |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

21.My things are taken away or hidden from me |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

22. My schoolwork is destroyed |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

23.I receive offensive, insulting or threatening messages via social media |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

24.Offensive or mocking photos and videos of me are published on the Internet to offend or laugh at me |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

When you have been in or seen situation like the previous ones, how did you react: (1 means “Never” and 10 means “Always”) |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Telling a teacher |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Telling your family |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Not doing anything |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||||||||||

1 Work funded by the University of Oviedo through the PAPI-20-EMERG-20 Project.