Transitioning to adulthood from a gender perspective:

young care leavers after 25 years of age1

La transición a la vida adulta en perspectiva de género:

jóvenes extutelados después de los 25 años

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2023-399-565

Eduardo Martín

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8004-9776

Universidad de la Laguna

Carme Montserrat

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5062-1903

Universidad de Girona

Gemma Crous

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3177-1356

Universidad de Barcelona

Abstract

Youngsters who leave the Child Protection System (CPS) have to deal with an accelerating process transitioning to the adult life, without the support that other youngsters have. The studies that explore this topic in Spain, and which are focused on the first years of this transition –mainly between 18 and 24 years old- highlight that it is a group of people with a lack of training, and this makes it difficult to be included in the working life. However, there are no studies that analyse their situation with a perspective over the time. An online ad hoc questionnaire was designed for care leavers between 25 and 35 years of age. Using the snowball technique, a total of 81 questionnaires were collected. The main findings are signifying that care leavers who are of this age are in a better situation academically and working wise, compared to those who just left the CPS. Moreover, these care leavers have a higher satisfaction with their years at in the CPS compared to the support that they received when they left the CPS, and they explained that they suffered psychosocial complex adversities. Some gender differences were found. Girls seem to go for the maternity option and for building a family project instead of a professional one, and they mention being less satisfied with their life compared to the boys. To conclude, the situation of the care leavers improves over time, but they also had to deal with some adversities that place them in vulnerable situations with regards to social inclusion. It is necessary to place more attention on those care leavers to help them face at least their emancipation process with a guarantee of success. Moreover, it is important to do this within a gender perspective, because of the fact that lots of those girls live this process through the maternity.

Keywords: child protection, care leavers, transitioning to the adult life, social working integration, gender, satisfaction.

Resumen

Los jóvenes que abandonan el Sistema de Protección Infantil (SPI) deben enfrentarse a un proceso de transición a la vida adulta acelerado y sin los apoyos de los que disponen los jóvenes de la población general. Los estudios que abordan este tema en España, y que se centran en los primeros años -mayoritariamente entre los 18 y los 24 años- señalan que se trata de un colectivo con carencias formativas que dificultan su integración sociolaboral. No obstante, no existen estudios que analicen su situación con una mayor perspectiva temporal. En este estudio se elaboró un cuestionario ad hoc online destinado a jóvenes extutelados que se encontraran en la franja de edad de 25-35 años. Utilizando la técnica de muestreo de la bola de nieve se recogieron 81 cuestionarios. Los principales resultados parecen indicar que a nivel formativo y laboral se encuentran en mejor situación que los que acaban de abandonar el SPI, que manifiestan una mayor satisfacción con su estancia en el SPI que con el apoyo recibido a su salida, y que sufrieron adversidades psicosociales complejas. Se encontraron diferencias de género relevantes. Así, las chicas parecen optar mayoritariamente por la maternidad y por un proyecto familiar en detrimento de uno profesional, manifestándose menos satisfechas con su vida actual que los chicos. Se concluye que la situación de los jóvenes extutelados mejora con el paso del tiempo, pero también que se han tenido que enfrentar a unas adversidades que ponen seriamente en riesgo su inclusión social. Es necesario redoblar esfuerzos en la atención que se le presta a estos jóvenes para que puedan afrontar su proceso de emancipación con unas mínimas garantías de éxito. Además, debe hacerse con un enfoque de género, ya que muchas de las chicas viven este proceso marcado por la maternidad.

Palabras clave: protección infantil, extutelados, transición a la vida adulta, integración sociolaboral, género, satisfacción

Introduction

In Spain, as in most countries, the public administration has subsidiary responsibility for the care of children when the family does not cover their most basic needs, relying on the Child Protection System (CPS). When the child’s situation puts their development at serious risk, a state of neglect may be declared, whereby the public administration assumes guardianship by adopting a measure of protection and placing the child either in foster care (with either extended family or an outside family) or in a shelter or residential centre. These measures of protection are of a provisional nature, and during their execution an attempt is made to work with the families with a view to a possible reunification if the reasons that gave rise to the declaration of abandonment are overcome. In cases where reunification with the family of origin is not possible and the young person reaches legal adulthood, they are prepared for emancipation when they leave the CPS at the age of 18. According to the latest official statistics released by the Spanish Childhood Observatory (Observatorio de la Infancia, 2021), there were a total of 49,171 children and adolescents in Spain with some form of measure of protection at the end of 2020, of whom 47% were in residential care and 53% in foster care. Although for years Spain has been committed to promoting foster care, the fact is that the number of young people in residential care is still considerable. This is due, among other things, to the arrival of unaccompanied foreign adolescents, who are mostly placed in protection centres. Also according to official data, one out of every three young people in care reaches legal adulthood while in care, as it has not been possible to adopt a family alternative (reunification with their family of origin or foster care in another family) beforehand. Act 26/2015, on the modification of the child and adolescent protection system, mentions for the first time the need to support these young people after reaching legal adulthood, although the implementation of support services is very uneven throughout the county, because, among other things, the responsibilities for this area are devolved to the autonomous communities, and the pace at which they have been adapting their regional legislation and implementing actions has varied. This, along with the lack of coverage in national legislation of a child protection data collection system (UNICEF and Eurochild, 2021) also creates difficulties in the collection and publication of official data. This makes it impossible to have reliable statistics on such relevant variables as the age at which children leave the protection system (CPS), or where they go to live afterwards, among others.

In recent decades, an increasing number of studies have focused on the population of young CPS care leavers, who are forced to make, in most cases, an accelerated, abrupt and often unprepared and unsupported transition to adulthood (Stein & Ward, 2020). The consequences of this uneven process can result in incomplete educational pathways, high rates of unemployment or precarious employment (Montserrat, Casas, Malo & Bertrán, 2011), housing problems, mental health problems (Mann-Feder & Goyette, 2019) and low subjective well-being (Martín, González-Navasa, Chirino & Castro, 2020), among other problems (Trull-Oliva, Janer-Hidalgo, Corbella-Molina, Soler-Masó & González-Martínez, 2022).

This increased interest on the part of researchers is perhaps due to the fact that studies focusing on the population of care leavers are, in addition to deepening the knowledge of the difficulties in the transition to adulthood of a vulnerable population, able to provide data that can be used as indicators for the evaluation of the results of the CPS. In this sense, the results of these studies make it possible to challenge public policies for the implementation of improvements in the field of well-being, equal opportunities and social action in the complex transitions to adulthood of young people with reduced opportunities and support (Dixon, Ward & Blower, 2019). Thus, this growing interest in studies on young people in care has led to improvements in policy and practice in many countries, both through the inclusion in legislation of the need for care for these young people from the age of 18, and the emergence or consolidation of support services up to the age of 21, and in some cases beyond (23 or 25 years), albeit slowly and not without difficulties (McGhee, 2017; van Breda et al., 2020).

In any case, although the responses being implemented are still far from satisfactorily covering the needs of this group, there is a general consensus in recognizing that these young people need stable supportive environments (Mendes, 2022), both while they are in the CPS and when they leave it (Comasólivas, Sala-Roca & Marzo, 2018; Courtney et al., 2020). The role of education is key in all these processes, and progress must be made in the evaluation of socio-educational action programmes. Along these lines, Melendro, Rodríguez-Bravo, Rodrigo and Díaz (2022) highlight the success of socio-educational projects for transition to adult life in the training of young people, noting that this training is closely related to their perceived autonomy and psychological well-being. Furthermore, studies such as those by Courtney et al. (2020) highlight the capacity for recovery and resilience in these young people despite the trauma and challenges they have to overcome, noting that they often remain optimistic about their future, confident in their ability to achieve their goals, and report having people to confide in and receive support from.

However, most of this research focuses on the population in the process of emancipation from the CPS or during the first years after leaving it, i.e. between 18 and 21 years of age, up to the age of 25 at most. This article deals specifically with the study of young care leavers over the age of 25, an age bracket for which few studies have been carried out. Perhaps the most noteworthy is that carried out by Brännström, Forsmana, Vinnerljunga and Almquist (2017), which used longitudinal data to examine the outcomes from a cohort of more than 14,000 individuals in the CPS in Sweden, who were followed until they were around 60 years of age. They found that evident inequalities between adults who were and were not in care in relation to their social, economic and health trajectories. However, they also noted that, despite their vulnerability, they tended to cope well as adults. Similar results were found in one of the pioneering studies in Spain (Del Valle, Bravo, Álvarez & Fernanz, 2008), where it was found that the majority of those in foster care aged 24 or older were not immersed in processes of social exclusion.

In another part of the study dedicated to young care leavers over the age of 25 (Crous, Montserrat-Mir & Matás, 2021), 13 young people were interviewed with the aim of researching the factors that help young people in their emancipation process. Both personal factors, such as the ability to overcome adversities or the perception of control and autonomy, and relational contextual factors, such as education and social support, were identified. In addition, the young people also felt that the passage of time helped them, in the sense that the label of care leaver faded away.

Another variable that is attracting increasing interest among CPS researchers is gender. In recent years, evidence has emerged that points to significant gender differences in the experience of being in public care. Although emotional and behavioural problems are prevalent among those in care (Martín, González-García, Del Valle & Bravo, 2018), research shows that young women and men experience these problems differently. Thus, internalized emotional problems are more frequent in young women, while externalized behavioural problems are more common in young men (Dowdy-Hazlett & Boel-Studt, 2021; Sonderman et al., 2021). In the case of the latter, the high prevalence of behavioural problems often produce antisocial behaviours that lead to problems with the justice system (Baidawi, 2020; Martín, González-Navasa & Domene-Quesada, 2021). In the case of young women, one peculiarity that has been observed among adolescent girls in care is the high number of pregnancies, which some studies attribute to the fact that these girls have a positive perception of adolescent motherhood and prioritize motherhood and finding a partner over occupational goals (Bermea, Rueda & González-Pons, 2021; Hlungwani & van Breda, 2020; Zárate, Arnau-Sabatés & Sala-Roca, 2017). Furthermore, studies analysing subjective well-being have detected lower scores among young women (Llosada-Gistau, Casas & Montserrat, 2017; González-García et al, 2022).

In the case of young care leavers, although studies from a gender perspective are scarce, results indicate that young women are generally worse off than men. Dinisman, Zeira, Sulimani-Aidan and Benbenishty (2013) identified lower subjective well-being among female care leavers compared to males. The review by Martín (2015) concluded that girls in residential care have greater difficulties in social and occupational processes, with unemployment rates much higher than those of their male counterparts. Hlungwani and van Breda (2020) described the psychosocial resilience processes that facilitate the transition of young female care leavers and identified similar processes to those of male care leavers on the one hand, while noting the presence of specific processes of resilience on the other, and in particular the acceptance of motherhood and assumption of responsibilities. Colbridge, Hassett and Sisley (2017) analysed intersections between being a woman and a care leaver, where aspects such as sexual abuse, exploitation and high risk of pregnancy are realities they face when they leave the CPS, as well as more mental health problems than young men. These authors underlined that although many female care leavers achieve competitive academic results and employment pathways, this is not as common statistically, as emotional barriers interfere, such as the development of self-confidence and pressures to conform to gender roles that do not necessarily reflect their identity, which already complex on leaving the CPS. In addition, the few studies that have focused on gender-based violence in young care leavers have found a prevalence four times higher than in the general population, and that it also tends to increase with age, so that it would continue to be present after leaving the CPS, affecting young women in particular (Dosil, Jaureguizar & Bermaras, 2021; Oyarzún, Pereda & Guilera, 2021).

As we have seen, there are hardly any studies that analyse the reality of young care leavers beyond the first years after reaching legal adulthood, and there are even fewer studies that approach this situation from a gender perspective.

Objectives

The aim of this article is to shed light on the situation of young care leavers between 25 and 35 years of age, taking into account the gender perspective, thus contributing to augmenting the few studies that cover these two areas, with the ultimate aim of proposing lines of socio-educational action. More specifically, the goals are:

- To find out the level of education they have attained, and their current employment and living situations.

- To analyse the main psychosocial problems that have affected them after leaving the CPS.

- To find out how satisfied they are with their stay in the CPS, with the support they received on leaving it, and with their current life.

Method

The methodology used in this research is quantitative, descriptive and cross-sectional, using a questionnaire as a data collection instrument. However, this study also included a part of qualitative data collection through thirteen interviews with young care leavers (see Crous et al., 2021), the results of which are discussed with those of the quantitative part described here.

Sample

This study involved 81 young people who were taken into care by the public administration, residing in Catalonia, the Canary Islands and Cantabria. These three communities were chosen for convenience, as the research team had contact with organizations that worked with care leavers, and who offered to assist in locating young people between 25 and 35 years of age. At the time of completing the questionnaire, the young people were aged between 25 and 35 (M = 29.2; SD = 3.6). Fifty of them were female (61.7%). Of the total sample, 30 (37%) were born outside Spain. Of these, 12 (40%) had Spanish nationality, and just over a third had a residence permit (36.7%) and/or work permit (33.3%). The percentage of men born outside Spain (61.3%) was significantly higher than that of women (22%), (χ2 (1) = 12.668, p < .001). The mean age of entry into the CPS was 11.8 years (SD = .97) and the mean age of exit was 17.5 (SD = 1.5).

Instrument

Due to difficulties in accessing the target population, the decision was made to develop an ad hoc questionnaire that could be disseminated online through social networks. This questionnaire, in addition to collecting reference data (gender, nationality, community of residence, legal status, age of entry and exit from the CPS), included questions on academic level achieved, current employment and housing situation, relevant problems they may have experienced after reaching the adulthood, as well as their level of satisfaction, both with their stay in the CPS and with the support received on leaving, as well as with their current life in general. For the latter question, we used the single item of the Overall Life Satisfaction Scale (OLS), which has been previously included in research on subjective well-being in young people in residential care (Llosada-Gistau et al., 2017), as well as in young care leavers upon release from the CPS (Martín et al., 2020).

The questionnaire was developed by the research team, and subsequently validated by a group of young care leavers living in public housing. In the validation process, a group interview was conducted with three care leavers. At the interview, they were first presented with the questionnaire, were given time to fill it in individually and read all the questions, and then each question was discussed in the group one by one. They were asked for their opinion on whether the question was understood, whether it was coherent, whether it was relevant, and whether they had any other comments. All opinions and/or criticisms were noted down, and they were asked to propose a solution for each of them. From the data collected, the research team decided how to make the changes and how to implement the comments received. An example of an improved question is ‘Who do you live with?’ Participants asked for the addition of other options that had not been considered, such as living with a partner and the partner’s family, living with a foster family, or living with biological family.

Procedure

Once the questionnaire had been drafted, contact was made with the heads of organizations that managed residential centres and resources for young care leavers, asking them to send it to care leavers aged between 25 and 35 with whom they were in contact, and to ask them both to fill it in and to forward it to their peers in the same age range, using the snowballing technique. The link to the questionnaire was also disseminated through social networks and websites of different organizations, e.g. organizations related to adult education, or to support, or programmes for young care leavers; associations of care leavers; or civic centres and youth centres in various big cities. This non-probability sampling technique is recommended when working with samples that are difficult to locate (Cubo, Martín & Ramos, 2011).

Data analysis

Bivariate analyses were performed to find out in which variables there were significant differences between young men and women. For categorical variables we used the χ statistic2 and the corrected standardized residuals (CSR). The confidence interval used for the CSRs is .95, so that values above 1.95 and below -1.95 are considered significant. For continuous variables, Student’s t-statistic was used. Effect size was calculated using Cohen’s d for continuous variables and odds ratios (OR) for categorical variables. To describe the magnitude of the effect size, we followed the criteria proposed by Chen, Cohen and Chen (2010), which are, for Cohen’s d and ORs respectively: < .20 and < 1.68: negligible; .20 - .49 and 1.68 - 3.47: small; .50 - .79 and 3.48 - 6.7: moderate; > .80 and > 6.7: large. All analyses were conducted using SPSS v24.

Ethical aspects

This research was approved by the Research Ethics and Biosafety Committee of the University of Girona (approval code: CEBRU0004-2019). An agreement was also signed with the child protection authorities specifying the treatment of the data by the Research Team in relation to access to information, data treatment at the team site, security measures and confidentiality.

Results

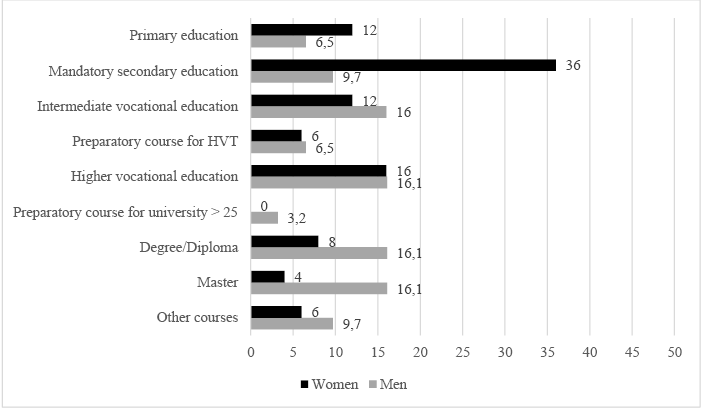

Figure 1 shows the level of education attained by the young care leavers. The differences between young men and women were statistically significant (χ2 (8) = 12.315, p = .14). The results indicated that women tend to reach lower levels than men, with the difference between the two genders being particularly large in the percentages who reached only secondary education (CSR > 1.95). Thus, almost half (48%) of the women reached secondary education at most, including those who only completed primary education, a much higher percentage than the men (16.2%). Although the corrected standardized residuals were not significant, they became more so in the percentages of those with university studies, especially in Master’s/Postgraduate studies (CSR = 1.9).

FIGURE I. Level of education attained by women and men (%)

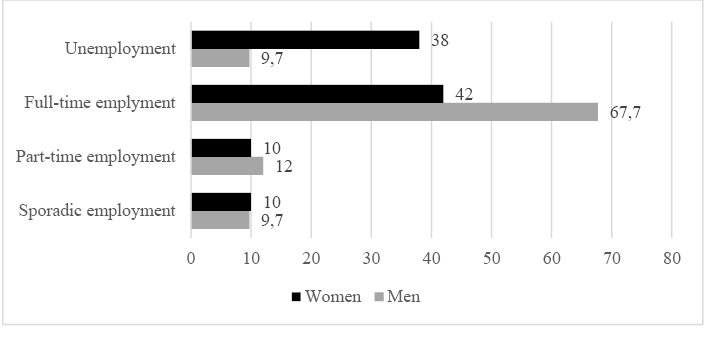

Employment status (see Figure 2) was also clearly better for young men than for women (χ2 (3) = 8.244, p < .05). The corrected standardized residuals (CSR > 1.95) showed that the percentage of men working full-time was higher than that of women, while the percentage of women who were not working was higher than that of men. Of those who were employed, the percentage of men who were employed with a contract was significantly higher (90%) than that of women (71.8%), (χ2 (1) = 3.475, p < .05), with a moderate effect size: OR = 3.536 [95%CI .888, 14.078]. The poorer employment situation of women was also reflected in the receiving of some kind of financial support. In this respect, 22% of women received some kind of allowance, while no men were recipients (χ2 (1) = 7.892, p < .01), the effect size being small: OR = 1.795 [95%CI 1.457, 2.212].

FIGURE II. Current employment status of women and men (%)

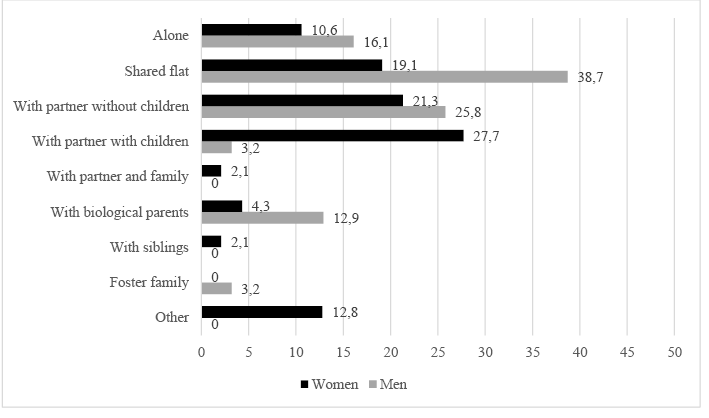

Regarding living situation (see Figure 3), significant differences were also found by gender (χ2 (8) = 18.082, p < .05). The corrected standardized residuals showed that significant differences were found between those who shared a flat with other people, which was more common among men, and those who lived with a partner and children, or in other situations, which mostly referred to living alone with a child, which was more common among women. These differences are related to the fact that women reported having significantly more children (M = .95, SD = 1.07) than men (M = .07, SD = .26), t(49.479) = -5.181, p < .001, the effect size being large in this case: d = .93.

FIGURE III. Who women and men currently live with (%)

When analysing the most relevant problems they have had since leaving the CPS (see Table 1), significant differences were only found in relation to incarceration, which occurred in one out of ten men and in none of the women. However, the effect size was small. Although no significant differences were found between men and women, it should be noted that the percentage of care leavers who have been hospitalized due to health problems was high for such a young population. The percentages of those who have had addiction problems or who have lived on the street at some point were also high, reaching around 20% of young men.

TABLE I. Relevant problems for men and women (%)

|

Men |

Women |

χ2(1) |

OR [IC95%] |

|

|

Physical health problems involving admission for more than 5 days |

16.1 |

10.9 |

.453 |

1.577 [.416, 5.983] |

|

Mental health problems that have involved admission for more than 5 days |

3.2 |

4.3 |

.062 |

.733 [.064, 8.455] |

|

Incarceration |

10.3 |

0 |

4.953* |

2.769 [2.037, 3.765] |

|

Drug and/or alcohol abuse |

16.7 |

14.6 |

.062 |

1.171 [.335, 4.092] |

|

Homelessness |

19.4 |

12.8 |

.623 |

1.640 [.476, 5.645] |

*P <.05

Finally, when analysing satisfaction, significant differences were only found in satisfaction with life now (see Table 2), which was higher in men, although with a small effect size. Although not significant, the differences indicated that satisfaction with the experience in the CPS and with the support received on leaving the CPS was higher for men, with insignificant and small effect sizes, respectively.

TABLE II. Satisfaction with the stay in the protection system, with support on exit, and with current life

|

Men M(DT) |

Women M(DT) |

t(gl) |

Cohen’s d |

|

|

Satisfaction with the CPS experience |

7.35(2.07) |

7.17(2.68) |

.332(77) |

.007 |

|

Satisfaction with the support received when leaving the CPS |

6.52(3.53) |

5.59(3.78) |

1.087(75) |

.2523 |

|

Satisfaction with current life |

7.87(1.95) |

6.9(2.33) |

1.936(78) * |

.4368 |

*p < .05

Discussion and conclusions

The aim of this study was to provide information on the situation of young people who were taken into care by the public administration when they were children and are currently aged between 25 and 35, and to do so from a gender perspective. To this end, three objectives were established. The first was to determine the level of education attained, their current employment situation and their living situation. The findings indicate that, in general, the level of education attained is higher than that of adolescents care leavers, among whom there is a greater number who have not completed compulsory education (Martín et al., 2020; Montserrat et al., 2011). This could be due to the fact that many care leavers eventually return to school, which would imply that both the academic and general situation improves, in parallel to a process of maturation and awareness of the importance of education (Courtney et al., 2020; Del Valle et al., 2008; Melendro et al., 2022). In terms of gender, significant differences have been found, with the situation of young men being better than that of women. Studies that have analysed the academic situation of young people while in care (García-Molsosa, Collet-Sabaté & Montserrat, 2021; González-García, Lázaro, Santos, Del Valle & Bravo, 2017) have found opposite results, as the situation of girls tends to be better, as is the case in the general population. This change in trend is possibly due to the fact that young women tend to prioritize their family goals over their work goals when leaving the Child Protection System (Bermea et al., 2021; Hlungwani & van Breda, 2020; Zárate et al., 2017) or because young women tend to find it more difficult to integrate into society when they reach adulthood (Colbridge et al., 2017; Martín, 2015). This would also explain the differences found in employment status, which indicate that young men have more full-time jobs with a contract than women, a considerable percentage of whom do not work. The results found when analysing living situation are marked by the fact that young female care leavers have more children than their male counterparts, which would explain why they live with them, either with a partner or alone.

The second objective was to analyse the main psychosocial problems that had affected them after leaving the CPS. The results indicate that a considerable percentage have suffered major health problems that led to hospital admission, have had problems with drug and alcohol consumption, and have even been forced into a situation of homelessness. In the latter case, an alarming result is that almost 20% of the young men have lived on the street at some point after leaving the CPS. These results corroborate the fact that the transition to adulthood for young care leavers is a complex process, fraught with risks and in many cases unfolding without the necessary support (Mann-Feder & Goyette, 2019; Martín et al., 2020; Moreno-Aponte, 2022; Stein & Ward, 2020; Trull-Oliva et al., 2022), although many young people are able to develop processes of resilience and overcome the many adversities they encounter along the way (Brännström et al., 2017; Courtney et al., 2020; Del Valle et al., 2008). The results of a qualitative study in which 13 of the young people who make up the sample of this work were interviewed (Crous et al., 2021) are along these lines, since the maturity that they achieve over time, as well as the fading of the stigma of being care leavers, are identified by the young people themselves as factors that foster their resilience.

Regarding psychosocial problems that young care leavers have to face, gender differences were found in incarceration, as all young offenders who had been sentenced to imprisonment were male. Specifically, one in ten young men in the sample had committed a jailable offence. This result is consistent with those of other studies, which point out that the population under the care of the public administration is over-represented among the population of adolescent offenders, and that it is a mostly male phenomenon (Baidawi, 2020; Martín et al., 2021), so it is logical to think that when leaving the CPS these problems with the justice system will continue, at least during the first few years.

The last objective was to find out how satisfied 25-35 year olds were with their stay in the CPS, with the support they received on leaving, and with their current life. A first relevant result is that satisfaction with the stay in the CPS is higher than with the support received on leaving, which may indicate that young people require more help in the process of transition to adult life (Comasólivas et al., 2018; Courtney et al., 2020). Overall, life satisfaction is similar to that of young people who are still in care (Llosada-Gistau et al., 2017), and higher than that of young care leavers in the first years after leaving the CPS (Martín et al., 2020), which may indicate that over time they develop processes of resilience that allow them to overcome many adversities (Brännström et al., 2017; Courtney et al., 2020; Del Valle et al., 2008), which undoubtedly leads to greater life satisfaction. However, it should also be noted that the young people in the sample undertook their transition to adulthood before the need for support was legislatively recognized, so the resources that are now available did not exist, which would explain, at least in part, such low satisfaction with the support received when leaving the CPS. A final noteworthy result is that satisfaction with their current life is higher in young men than in women, which corroborates results found in other studies (Dinisman et al., 2013; González-García et al., 2022).

Two main conclusions can be drawn from this study. The first is that, as other authors have pointed out, many young care leavers end up developing processes of resilience that help them to move forward, but not without effort and having to face multiple adversities. This process is not immediate, however, and during the first years of the transition to adulthood many of them encounter situations that seriously jeopardize their socio-occupational integration process, such as problems with drugs and/or alcohol, problems with the justice system and even homelessness. The prevalence of these problems among young care leavers is a clear indicator that they need help once they leave the CPS, especially during the first few years. And while it seems that many of them manage to overcome these problems and become resilient individuals who even emerge stronger, there may be cases that do not overcome these adversities, and end up in situations of severe social exclusion.

The second conclusion of this study applies to gender differences. The process of transition to adulthood for young women is marked in many cases by the adoption of traditional gender roles, prioritizing the creation of a family project of their own, with a partner and children, which undoubtedly leads them to put aside their educational and employment goals. Furthermore, with the problem of gender violence also present in a considerable number of cases (Dosil et al., 2021; Oyarzún et al., 2021), it is clear that the process of transition for young women’s lives is more complex and less satisfactory for them. In this sense, it seems necessary to adopt a gendered approach in the actions that are developed for young care leavers, in order to respond to the specific needs of girls.

This work reiterates the need for a system of data collection that allows for an evaluation of the results of the CPS, monitoring all young people who leave it in the short, medium and long term, in order to detect their needs and design actions to be implemented, always taking into account the opinion and experience of the young people themselves. In this sense, it should be remembered that the actions developed with the young care leavers are voluntary, and require an involvement and commitment that not all young people are willing to assume, especially those with a more complex profile and emotional and behavioural problems, which undoubtedly represents a major challenge for professionals.

Before concluding, we must address the main limitations of this study, which concern the size of the sample, its representativeness and the extrapolation of its results. The population of care leavers in the 25-35 age group is difficult to locate, as they left the CPS at least seven years ago, which makes it very difficult to carry out studies with statistically representative samples, at least in countries such as ours, which do not have registers that allow for follow-ups to be carried out. Furthermore, it is likely to be less difficult to access those who are in a better situation, being practically impossible to access those who disconnected from the CPS from the beginning, or who have fallen into a situation of severe social exclusion. Moreover, the fact that responsibility for the area of child protection, and therefore in the care of foster children, are devolved to regional authorities means that in practice there are significant differences among the autonomous communities in the care provided to young people in and out of the system, so that having a sample of only three communities requires caution when generalizing the results.

But it is precisely the fact of carrying out a study with a population that is so difficult to access and with so many needs, which becomes its main strength, as it provides useful data for designing actions with a traditionally overlooked group, such as young people who leave the CPS and are forced to undertake a process of transition to adulthood without the necessary tools and support. Nevertheless, it is necessary to continue down this path, developing work with larger and more representative samples, and taking into account the gender perspective, since research has been accumulating evidence that shows that young men and women experience their emancipation with different conditioning factors, and this may mean that the attention given to care leavers should take into account the gender perspective.

References

Baidawi, S. (2020). Crossover children: Examining initial criminal justice system contact among child protection involved youth. Australian Social Work, 73(3), 280-295. https://doi.org/0312407X.2019.1686765

Bermea, A. M., Rueda, H. A., & González-Pons, K. M. (2021). Staff perspectives regarding the influence of trauma on the intimate partnering experiences of adolescent mothers in residential foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 38(3), 283-294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00678-0

Brännström, L., Forsmana, H., Vinnerljunga, B., & Almquist, Y. B. (2017). The truly disadvantaged? Midlife outcome dynamics of individuals with experiences of out-of-home care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 67, 408–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.009

Chen, H., Cohen, P., & Chen, S. (2010). How big is a big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratio in epidemiological studies. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation, 39(4), 860-864. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610911003650383

Colbridge, A., Hassett, A., & Sisley, E. (2017). “Who am I?” How Female Care Leavers Construct and Make Sense of Their Identity. SAGE Open, 7(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016684913

Comasólivas, A. C., Sala-Roca, J., & Marzó, T. E. (2018). Residential resources for the transition towards adult life for fostered youths in Catalonia. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 31, 125-137. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2018.31.10

Courtney, M. E., Okpych, N. J., Harty, J., Feng, H., Park, S., Powers, J., Nadon, M., Ditto, D. J., & Park, K. (2020). Findings from the California youth transitions to adulthood study (CalYOUTH): conditions of youth at Age 23. Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

Crous, G., Montserrat, C., Gallart-Mir, J., & Matás, M. (2021). ‘In the end you’re no longer the kid from the children’s home, you’re yourself’: Resilience in care leavers over 25. European Journal of Social Work, 24(5), 896-909. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2021.1918063

Cubo, S., Martín, B., & Ramos, J. L. (2011). Métodos de investigación y análisis de datos en ciencias sociales y de la salud. Pirámide.

Del Valle, J. F., Bravo, A., Álvarez, E., & Fernanz, A. (2008). Adult self-sufficiency and social adjustment in care leavers from children’s homes: A long term assessment. Child & Family Social Work, 13(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2007.00510.x

Dinisman, T., Zeira, A., Sulimani-Aidan, Y., & Benbenishty, R. (2013). The subjective well-being of young people aging out of care. Children and Youth Services Review, 35, 10, 1705-1711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.07.011

Dixon, J., Ward, J., & Blower, S. (2019). “They sat and actually listened to what we think about the care system”: The use of participation, consultation, peer research and co-production to raise the voices of young people in and leaving care in England. Child Care in Practice, 25(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2018.1521380

Dosil, M., Jaureguizar, J., & Bermaras, E. (2021). Dating violence in adolescents in residential care: frequency and associated factors. Child and Family Social Work, 27(2), 311-323. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12886

Dowdy-Hazlett, T., & Boel-Studt, S. (2021). Predictors of Mental Health Diagnoses Among Youth in Psychiatric Residential Care: A Retrospective Case Record Analysis. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00728-7

García-Molsosa, M., Collet-Sabé, J., & Montserrat, C. (2021). What are the factors influencing the school functioning of children in residential care: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105740

González-García, C., Águila-Otero, A., Montserrat, C., Lázaro, S., Martín, E., Del Valle, JF., & Bravo, A. (2022). Subjective well-being of adolescents in therapeutic residential care from a gender perspective. Child Indicators Research, 15(1), 249–262 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09870-9

González-García, C., Lázaro, S., Santos, I., Del Valle, J. F., & Bravo, A. (2017). School functioning of a particularly vulnerable group: children and young people in residential care. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1116. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01116

Hlungwani, J., & van Breda. A. (2020). Female care leavers’ journey to young adulthood from residential care in South Africa: Gender-specific psychosocial processes of resilience. Child and Family Social Work, 25(4), 915- 923. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12776

Llosada-Gistau, J., Casas, F., & Montserrat, C. (2017). What Matters in for the Subjective Well Being of Children in Care? Child Indicators Research, 10(3), 735–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-016-9405-z

Mann-Feder, V., & Goyette, M. (Eds.) (2019). Leaving care and the transition to adulthood. Oxford University Press.

Martín, E. (2015). Niños, niñas y adolescentes en acogimiento residencial. Un análisis en función del género. Qurriculum 28, 91–105.

Martín, E., González-García, C., Del Valle, J. F., & Bravo, A. (2018). Therapeutic residential care in Spain. Population treated and therapeutic coverage. Child and Family Social Work, 23(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12374

Martín, E., González-Navasa, P., Chirino, E., & Castro, J. J. (2020). Social Inclusion and life satisfaction of care leavers. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 35, 101-111. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2020.35.08

Martín, E., González-Navasa, P., & Domene-Quesada, L. (2021). Entre dos sistemas: los jóvenes tutelados en acogimiento residencial con medidas judiciales. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 31, 55-61. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2021a5

McGhee, K. (2017). Staying Put and Continuing Care - The Implementation Challenge. Scottish Journal of Residential Child Care, 16(2), 1-19.

Melendro, M., Rodríguez Bravo, A., Rodrigo, P., & Díaz, M. J. (2022). Evaluación de las transiciones a la vida adulta de los jóvenes que egresan del sistema de protección. Pedagogía Social, Revista Interuniversitaria, 40, https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2022.40.02

Mendes, P. (2022). Ending Australia’s Status as a “Leaving Care Laggard”: The Case for a National Extended Care Framework to Lift the Outcomes for Young People Transitioning from Out-of-Home Care. Australian Social Work, 75(1), 122-132, https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2021.1910323

Montserrat, C., Casas, F., Malo, S., & Bertrán, I. (2011). Los itinerarios educativos de los jóvenes extutelados. Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad.

Moreno-Aponte, R., & Vila-Merino, E. S. (2022). Identidad narrativa en la relación educativa: promesa, solicitud y don. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 34(1), 125-138. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.26397

Observatorio de la Infancia (2021). Boletín de datos estadísticos de medidas de protección a la infancia, (número 22). Ministerio de Derechos Sociales y Agenda 2030.

Oyarzún, J., Pereda, N., & Guilera, G. (2021). The prevalence and severity of teen dating violence victimization in community and at-risk adolescents in Spain. Child and Adolescent Development, 2021 (178), 39-58. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20433

Sonderman, J. Van der Helm, G. H. P., Kuiper, C. H. Z., Roest, J. J., Van de Mheen, D., & Stams, M. (2021). Differences between boys and girls in perceived group climate in residential youth care. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105628

Stein, M., & Ward, H. (2020). Transitions from care to adulthood – persistent issues across time and place. Child & Family Social Work, 26(2), 215-221. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12802

Trull-Oliva, C., Janer-Hidalgo, Á., Corbella-Molina, L., Soler-Masó, P. y González-Martínez, J. (2022). Sobre las estrategias metodológicas de los/as educadores/as para contribuir al empoderamiento juvenil. Educación XX1, 25(1), 459-483. https://doi.org/10.5944/educXX1.30014

UNICEF & Eurochild (2021). Children in alternative care: Comparable statistics to monitor progress on deinstitutionalisation across the European Union. UNICEF & Eurochild.

Van Breda, A., Munro, E., Gilligan, R., Angheld, R., Hardere, A., Incarnato, M., Mann-Feder, V., Refaeli, T., Stohler, R., & Storø, J. (2020). Extended care: Global dialogue on policy, practice and research, Children and Youth Services Review 119, 105596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105596

Zárate, N., Arnau-Sabatés, L., & Sala-Roca, J. (2017). Factors influencing perceptions of teenage motherhood among girls in residential care. European Journal of Social Work, 21(4), 572-584. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2017.1292397

Contact Address: Eduardo Martín Cabrera, Universidad de la Laguna, Facultad de Educación, Departamento de Psicología Evolutiva y de la Educación. C/ Pedro Zerolo, s/n. Edificio Central. Apartado 456, postal code 38200, San Cristóbal de La Laguna. Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain. E-mail: edmartin@ull.edu.es

1 This work has been funded by Fundación SM through two contracts signed with the universities of Girona and La Laguna