Dishonest conduct and corrective measures.

Business university student perspective1

Comportamientos deshonestos y medidas correctoras.

Perspectiva del estudiante universitario de negocios

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2023-399-566

Mercedes Marzo-Navarro

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9628-5738

Universidad de Zaragoza

Marisa Ramírez-Alesón

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9758-0149

Universidad de Zaragoza

Abstract

University life should be governed by honesty, that is, by the academic integrity of all the agents involved. However, the literature shows the existence of dishonest academic conduct on the part of the students. The first objective of this paper is to identify which forms of conduct are considered dishonest by university students and how often they are observed. Subsequently, the second objective is to identify the measures that could prevent this type of conduct and would be most suitable and effective from the students’ perspective. In order to achieve the proposed objectives, a quantitative, cross-sectional and descriptive study was carried out. Between January and March 2020, a questionnaire was sent to undergraduate students at the Faculty of Economics and Business of the University of Zaragoza. The questionnaire refers to dishonest conduct during the preparation of assignments, exams and classroom activity along with the measures to avoid them. The analysis and tests to achieve the proposed objectives are applied to the 333 valid cases. The results show that university students adequately identify dishonest conduct, albeit with different degrees of seriousness. This does not prevent them from observing that some of them, whether serious or not so serious, appear more frequently than desirable. As regards the measures, they consider it necessary to apply corrective measures, whether through training or regulation, although they show a preference for regulatory measures. These results can serve as a basis for establishing Spanish university regulations that transpose the recently approved University Coexistence Act.

Keywords: student, university, evaluation, measure, regulations, plagiarism, dishonest practices, academic integrity, evaluation, measure, regulations.

Resumen

La vida universitaria debe regirse por la honestidad, es decir, por la integridad académica de todos los agentes implicados. Sin embargo, la literatura muestra la existencia de comportamientos académicos deshonestos por parte del alumnado. El primer objetivo del trabajo es identificar qué conductas son consideradas deshonestas por parte del alumnado universitario y con qué frecuencia son observadas. Posteriormente, el segundo objetivo es identificar las medidas que podrían evitar este tipo de comportamientos y que resultarían más adecuadas y eficaces desde la perspectiva del alumnado. Para conseguir los objetivos propuestos se efectuó un estudio cuantitativo, de corte transversal y descriptivo. Entre enero y marzo de 2020 se envió un cuestionario dirigido a los estudiantes de grado de la Facultad de Economía y Empresa de la Universidad de Zaragoza. El cuestionario recoge comportamientos deshonestos durante la elaboración de los trabajos, los exámenes y la actividad en el aula y las medidas para evitarlos. Los análisis y pruebas para conseguir los objetivos propuestos se aplican a los 333 casos válidos. Los resultados muestran que los estudiantes universitarios identifican adecuadamente los comportamientos deshonestos, aunque con diferentes grados de gravedad. Esto no impide que algunos de ellos, graves o no tanto, sean observados por su parte con una frecuencia superior a la deseable. En cuanto a las medidas, consideran necesario la implantación de medidas correctivas, ya sean formativas o normativas, aunque muestran una preferencia por las normativas. Estos resultados pueden servir de base para establecer las normas propias de las universidades españolas que transpongan la recientemente aprobada Ley de Convivencia Universitaria.

Palabras clave: estudiante, universidad, evaluación, medida, normativa, plagio, prácticas deshonestas, integridad académica, evaluación, medida, normativa.

Introduction

University life should be governed by such basic values as trust, rectitude, equity, honesty and equality, among others, that encourage the academic integrity of all agents involved, particularly students and faculty. However, there is a host of evidence and research that clearly shows the existence of dishonest conduct at universities in different parts of the world (Chapman & Lindner, 2016; Vlasenko & Shirokanova, 2022), including Spain (Comas, Sureda, Casero & Morey, 2011; Foltynek, 2013; Comas & Sureda, 2016). Furthermore, this type of conduct, far from disappearing, is on the rise (Alleyne & Phillips, 2011; Malesky, Baley, John & Crow, 2016), and transforming with the rise and development of information and communication technologies (ICT) (Sithole, Mupinga, Kibirige, Manyanga & Bucklein, 2019). The use of this type of conduct is becoming simpler (Young, 2012), and its spread is becoming faster and more widespread; hence, these actions may be copied by a host of people (Eckstein, 2003). The existence of dishonest conduct among university students is concerning, more so since some research papers show the existence of a relationship between its adoption at an academic level and subsequent dishonest conduct at a professional level (Alleyne & Phillips, 2011; Guerrero-Dib, Portales & Heredia-Escorza, 2020).

This student dishonesty in an academic environment is considered a constant and paramount problem at all levels of education, which has turned it into a serious educational problem (Orosz, Dombi, Tóth-Király, Bőthe, Jagodics & Zimbardo, 2016) that not only affects the credibility of the evaluations of student learning, but also affects the institutional image of the education centre (Ramos, Gonçalves & Gonçalves, 2020). Accordingly, academic dishonesty by students should be firmly addressed as an institutional concern, instead of merely the responsibility of the students (Marsh & Campion, 2018). In other words, academic honesty should be one of the fundamental cornerstones of the university life of students, such that it fosters the correct use of information, respect for intellectual property, honest conduct and compliance with prevailing legislation.

The existence of a wide variety of definitions of the concept of academic dishonesty, along with a broad taxonomy, complicates a clear identification of the dishonest conduct to be eradicated (Ramos et al., 2020), and hence requires new studies that complete and complement the results obtained in the previous literature (Marques, Reis & Gomes, 2019).

To achieve that, the first objective sought in this paper is to try to identify the conduct considered dishonest by students in a university context, and the frequency with which it is observed. Students do not tend to have a clear awareness of all forms of conduct that are considered dishonest, and hence this lack of awareness regarding what is acceptable or not may lead them to practise it.

Given that higher education institutions seek and endeavour to eradicate dishonest student conduct, they need to firstly identify the most suitable and effective measures and tools and then implement them. It is interesting to see the students’ perspective, as one of the main agents involved, which could enhance the success of discouraging and/or corrective measures. These measures include, on the one hand, training measures, which relate to those activities leading to inform and educate through knowledge and ethical skills. On the other hand, regulatory measures based on the establishment of norms and rules to follow and the consequences and sanctions in the event of not abiding by them.

Accordingly, the second objective of this paper consists of an in-depth analysis of these measures that assist in preventing dishonest conduct and that could be more suitable and effective from the perspective of the students.

The results obtained establish, on the one hand, that university students are able to correctly identify dishonest student conduct, and assign different levels of seriousness to different types of conduct. However, and despite this, this does not mean that this conduct, whether serious or not, is observed more frequently than desirable. Furthermore, they feel it is necessary to establish measures that discourage and/or correct these types of conduct. While they feel it is necessary to introduce both training and regulatory measures, they show a preference for regulatory measures. These results are very interesting because they offer the students´ perspectives regarding an issue that directly affects them, and which turns them into the main protagonists. Observing what they consider to be dishonest conduct is key to establishing corrective measures. Furthermore, observing student opinions on the type of measures they consider to be most effective in eradicating this type of inappropriate conduct could be useful for university management as complementary information in the design of codes of conduct and corrective measures. Hence, the results of this research could be relevant for the scientific education community, the faculty, the management teams, guidance counsellors and other members of the education community, as well as for the politicians commissioned with regulating academic activities and rules.

This paper is structured in the following sections. The next section mainly reviews the concept of academic dishonesty and the conduct that could be classified as such. Subsequently, training and regulatory measures are introduced that higher education institutions could resort to in order to prevent and combat these forms of dishonest conduct. The sample and questionnaire are then indicated that serve as the basis for this paper. The following section presents and analyses the main results. Lastly, the conclusions of the work and the main limitations are then summarised.

Academic dishonesty

The literature suggests that the concept of academic dishonesty is based on three pillars related, respectively, to academic management, teaching and research, and with learning and studying (Comas, 2009). This paper focuses on the third pillar.

Academic dishonesty or fraud in the teaching-learning process amounts to a moral transgression by students in the context of their academic relations and their responsibilities vis-à-vis faculty, the other students and the institution they belong to. Over time, its definition has changed (see the recent revision by Ramos et al., 2020) and its evolution is heavily influenced by the historical and social period in which it is raised (Kibler, 1993), since it is a construct largely based on ethical-moral principles. This complicates its comprehension and the identification of the forms it adopts, as well as its consequences. Accordingly, as indicated by Muñoz-Cantero, Rebollo-Quintela & Mosteiro-García (2019, p. 1), the lack of unanimity in the definition of the concept “is down to its universality, multidimensionality, multicausality and its cultural determinants”.

Despite this, there is a certain consensus in the literature regarding two key characteristics that conceptualise and allow dishonest conduct to be identified: intentionality and the aim of obtaining an advantage.

Many authors stress the need for the existence of intentionality in the deceit for academic fraud to exist (Epstein, 2010; Von Dran, Callahan & Taylor, 2001). Von Dran et al., (2001) define academic fraud as unethical intentional conduct. Along this same line, Epstein (2010) asserts that it consists of an intentional effort to deceive, but qualifies that, if the error is committed honestly or due to a simple difference of opinion, interpretation or judgement, this would not constitute academic fraud. What’s more, several studies show that the occasions on which plagiarism is employed with an intent to deceive are a minority (Almeida, Seixas, Gama, Peixoto & Esteves, 2016), and that normally plagiarism is a result of a lack of awareness of the regulations and potential sanctions (Porto-Castro, Espiñeira-Bellón, Losada-Puente & Gerpe-Pérez, 2019), although some studies have found two groups of students – those who plagiarise deliberately and those who plagiarise through ignorance and/or a lack of information (Sarmiento-Campos, Ocampo-Gómez & Castro-Pais, 2022). Along with the intentionality of the subject of the action, the aim pursued through this conduct takes on importance. Accordingly, academic dishonesty is any (intentional) conduct in the student’s learning process that breaches the rules established and the ethical principles of educational institutions and which, moreover, grants the student an unfair or undeserved advantage over the other students (Reyneke, Shuttleworth & Visagie, 2021), which translates into a higher mark. Therefore, any deliberate act or omission that may comprise the fairness of the comparative evaluation of student performance, skills and knowledge among students will constitute academic fraud.

The types of conduct that fall under the concept of academic dishonesty are many and varied, and not all of them are viewed with the same seriousness. Sureda-Negre, Cerdá-Navarro, Calvo-Sastre & Comas-Forgas (2020), based on the revision of the literature and expert opinions, highlight a lack of consensus on how to scale the level of seriousness and the repercussions of dishonest conduct that university students may incur in, particularly in those cases that are perceived as less serious. Accordingly, of the 41 types of dishonest conduct analysed, only nine can be classified as very serious with an acceptable consensus among experts. These include copying or cheating in exams, which is universally considered to be unlawful conduct, and is also the most widespread and habitual form of academic deceit (Teixeira & Rocha, 2010).

With the aim of identifying some of these types of dishonest conduct, and based on the proposal made by Comas et al., (2011), three types of groupings are proposed: i) conduct related to exams, ii) conduct related to the preparation and presentation of academic assignments, and iii) conduct within the framework of interpersonal relations and conduct related to daily aspects of respect and coexistence.

The greatest consensus in the literature can be found in the first group, in unlawful conduct when taking exams which, in turn, has been the group most closely researched by different institutions and in different countries (Teixeira & Rocha, 2010). This group includes a wide range of actions and practices related to exams: obtaining details on an exam before taking it, allowing another person to replace you during an exam, taking an exam in the place of another student, allowing someone to copy you, copying another person in the course of the exam, accessing unauthorised information during an exam either through the use of traditional “crib sheets” or through technological means (mobile phone, players, etc.). This last case is where both students and faculty agree that this constitutes dishonest conduct (Blankenship & Whitley, 2000). The second group includes those academically dishonest actions and practices relating to the preparation and presentation of academic assignments. These include copying ideas or fragments of text without quoting the corresponding source in the bibliography, the total or partial plagiarism of works (from Internet portals and/or printed documents), falsifying the bibliography and resources consulted in preparing an academic assignment, the falsification of data and/or results in assignments, not complying with the part of the assignment that corresponds to a student in groupwork, the presentation of an assignment prepared by another person while claiming it is their own work, buying academic assignments, etc. This type of conduct has played a larger role as a result of the changes undergone in methodological aspects, in learning processes and in evaluation systems of undergraduate degree subjects following the introduction of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). Accordingly, the evaluation system is a central aspect of the teaching-learning process which, following the changes introduced by the EHEA, is being modified to address a skills-based focus (Sánchez Santamaría, 2011). Hence, the evaluation model does not tend to be limited to a final test, but rather this is complemented by a mark obtained through preparing specific tasks, whether individually or in a group over the course of the academic year, such as the preparation of assignments, presentations, practices or classroom participation, among others. Therefore, the type of work that lecturers demand from students may condition the performance of these types of dishonest practices by students (Espiñeira-Bellón, Mosteiro-García, Muñoz-Cantero & Porto-Castro, 2020). In this context, ICT take on great importance, since they become a resource that fosters access by students to a larger range of sources of information when preparing their academic assignments (Marzal & Calzada, 2003; Cebrián-Robles, Raposo-Rivas & Ruiz-Rey, 2020), and with greater speed, and these circumstances, along with the simplicity offered by word processors, has turned academic plagiarism among students when preparing their assignments into a habitual practice (Ercegovac & Richardson, 2004). These types of conduct are not only dishonest, but also breach copyright laws, classified as a criminal offence against intellectual property. The third group contains those forms of conduct relating to interpersonal relations and conduct related to daily aspects of respect and coexistence at higher education centres. Such conduct as damaging equipment and/or furniture at academic facilities, damaging the equipment and personal belongings of other students, damaging the work and/or material of other students, interfering in the work or exams of other students and frustrating their activity, show a lack of respect towards other students or staff, etc.

Lastly, we should point out that, although the development of new technologies and their implementation in the learning and evaluation process (particularly important during the pandemic) has been key to the smooth development of the learning-education process of students, it has also facilitated the performance of some forms of dishonest conduct described above (Cebrián-Robles, Raposo-Rivas, Cebrián-de-la-Serna & Sarmiento-Campos, 2018; Sithole et al., 2019).

Discouraging and/or corrective measures

Universities are addressing this situation by taking measures to prevent and combat these forms of dishonest conduct, albeit not always successfully. Muñoz-Cantero et al., (2019) differentiate between actions of a preventative, organisational, coercive and attitudinal nature. Adam, Anderson & Spronken-Smith (2017) indicate raising awareness, prevention, information, training, detection and a disciplinary regime as forms of action. Hence, the revision of the literature shows that there are different options that higher education institutions can resort to so as to address this challenge. In this paper, we opt to distinguish between training measures and regulatory measures.

Training measures correspond to any type of informative and educational tool or activity (offer of courses, seminars, informative brochures, etc.) that contribute to the training of students in skills and ethical knowledge that prevent them incurring in dishonest conduct (Estow, Lawrence & Adams, 2011). This focuses on the students, and is based on the assumption that students who go to university lack some of the basic skills needed to tackle higher education in an educational environment (Morris, 2010). These skills include knowledge related to the appropriate and ethical use of information (American Association of School Librarians, 2009), along with a lack of awareness of the principles and rules of integrity of university institutions. For example, students frequently lack knowledge to quote or reference bibliographic sources correctly in the assignments they prepare, which leads them to incur in plagiarism (López & Fernández, 2019). Hence, if the training is suitable, it will serve to reduce certain forms of dishonest conduct. This focus shows how the lack of training by students constitutes the root cause of the performance of unintentional dishonest practices (Cerdá-Navarro, Touza, Morey-López & Curiel, 2021), and thus the use of training measures will also have a preventive aspect, so it would be advisable to include them in the initial years of university in order to reduce the prevalence of dishonest practices in the following academic years (Cebrián-Robles, Raposo-Rivas & Ruiz-Rey, 2020).

Regulatory mechanisms also exist, which can be addressed from two complementary perspectives (Tatum & Schwartz, 2017): (i) regulations that provides for coercive measures that discourage students from participating in dishonest conduct; and (ii) codes of ethics, honour and conduct that highlight the principles, values and basics of the institution and should be guided towards the activities undertaken at such institutions. In general, these types of mechanisms include those regulatory provisions that underline the types of dishonest conduct, along with the consequences and sanctions applicable if students incur in them (Sureda-Negre, Reynes-Vives & Comas-Forgas, 2016). These provisions may be of a general nature, approved by Parliament and which are applicable to all the universities in a country, and those inherent to each individual institution, which are approved by the governing body of the university.

In Spain, the University Coexistence Act 3/2022, of 24 February (Ley 3/2022, de 24 de febrero, de Convivencia Universitaria en España), has recently been approved. The main aim of this piece of legislation is to provide universities with a common framework to resolve conflicts by employing mediation at the heart of coexistence. The mechanisms of mediation seek to resolve most conflicts of coexistence between the members of the university community, endeavouring to apply the new disciplinary regime on a supplementary and residual basis. In this way, the disciplinary regime would only be activated when the parties reject the use of the mediation procedure, when the conduct leading to the disciplinary case is expressly excluded from this procedure (such as cases of harassment and gender-based violence, university fraud or the destruction of property) or when the parties are unable to reach an agreement. This Act lays the foundations for each university to enact their own rules of coexistence.

Universities tend to have their own rules approved by their governing bodies, such as rules on evaluation, general student rules and codes of ethics. Furthermore, each university centre (school, faculty, etc.) may have its own specific rules, which range from codes of ethics to specific regulations. With the entry into force of the new University Coexistence Act, these previous rules must be adapted to the new Act. Studies show that the existence of regulations that contain sanctions for the performance of proven acts against academic integrity reduce the performance of these kinds of acts by students, and furthermore, the stricter the rules, the fewer fraudulent practices take place within the institution (Ercegovac & Richardson, 2004; LoSchiavo & Shatz, 2011). However, the literature has shown that the simple existence of rules and regulations does not guarantee good conduct per se, since it is necessary for the rules to be familiar to all the system agents, and furthermore, that they are actually applied (Comas, 2009). So, if the rules are well-known, strict and applied, this discourages the performance of dishonest conduct (LoSchiavo & Shatz, 2011).

Given the variety of mechanisms to prevent dishonest conduct and having shown that none of them are ideal, universities should address this situation from a holistic manner. They could even use its training dimension, not focusing on aspects that are purely academic, to include ethical education on a cross-cutting basis, whereby this takes on an essential role in the training of all higher education professionals.

Methodology

To achieve the goal of this research, a non-experimental exploratory-descriptive study was opted for (Hernández, Fernández & Baptista, 2014). Specifically, a quantitative, cross-cutting study was employed based on information collected in a survey.

An online survey was designed (through Google Doc forms) that was anonymous (to guarantee the confidentiality of the information), which was sent to the institutional electronic mail accounts of all the students enrolled on undergraduate studies at the Faculty of Economics and Business of the University of Zaragoza, authorised by the university authorities. The fieldwork was carried out between January and March 2020.

Sample

The specific population under study was made up of 3,869 students enrolled in the academic year 2019/20 on one of the qualifications offered by the Faculty of Economics and Business of the University of Zaragoza.

The sample was made up of 333 valid questionnaires (with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5.13%). The majority of students were women (60.4%). More than half of the individuals surveyed were under the age of 22 (66.3%). The distribution by year of study was: 15.6% of those surveyed were in their first year at university, 18.4% in their second year, 26.2% in their third year and the remaining 39.9% in their fourth year.

Instrument

The questionnaire was made up of three blocks of questions.

In the first block (29 items) the student was asked, on the one hand, for a valuation on the level of appropriateness of a series of forms of conduct (on the Likert scales from 1 – totally inappropriate, to 10 – totally appropriate); and, on the other hand, on the frequency observed of said conduct in their classmates (from 0 – never, to 10 – always). Specifically, nine items were related to dishonest conduct when preparing assignments; nine items were related to conduct when taking exams; and 11 items on conduct within the framework of interpersonal relations and daily aspects of respect and social harmony.

In addition, and to analyse the reliability of the instrument employed, Cronbach’s alpha values were calculated for each dimension. Accordingly, for the block on “preparation and presentation of assignments”, the values are 0.805 (appropriateness) and 0.853 (frequency). For the “evaluation tests” dimension, the values are 0.833 (appropriateness) and 0.875 (frequency). And for the “interpersonal relations” dimension, the values are 0.602 (appropriateness) and 0.773 (frequency). Hence, the results obtained show that the instrument offers internal consistency.

The second block of questions (eight items) contains the student’s assessment of the need to introduce measures to discourage and/or prevent dishonest conduct. Specifically, four of them refer to regulatory measures and the other four to training measures (on the Likert scale from 0 – total disagreement, to 10 – total agreement).

In the same way as for the previous dimensions, and with the aim of analysing the reliability of the instrument, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated. The results obtained show a value of 0.772 for regulatory measures and 0.754 for training measures, thus backing the internal consistency of the instrument used.

The wording of most of these items was based on work proposals or previous reports (Alleyne & Phillips, 2011; Burke & Sanney, 2018; Zúñiga, Toscano & Ponce, 2015; Sureda-Negre et al., 2020, among others). Four academics2, from different fields of knowledge and universities, revised the final questionnaire and were then subjected to a pre-test by several undergraduate students with the aim of checking its comprehension and whether conduct was missing from the initial questionnaire.

Lastly, the third block contained questions on the socio-demographic characteristics of the students (sex, age) and of the subjects they are studying (academic year).

Analysis of the data

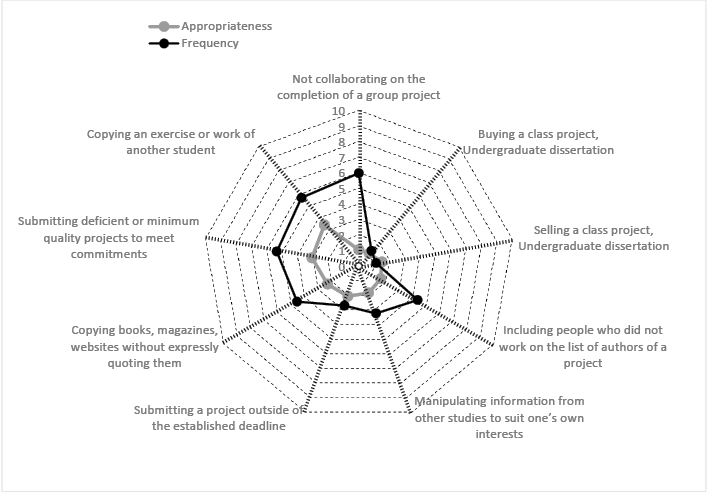

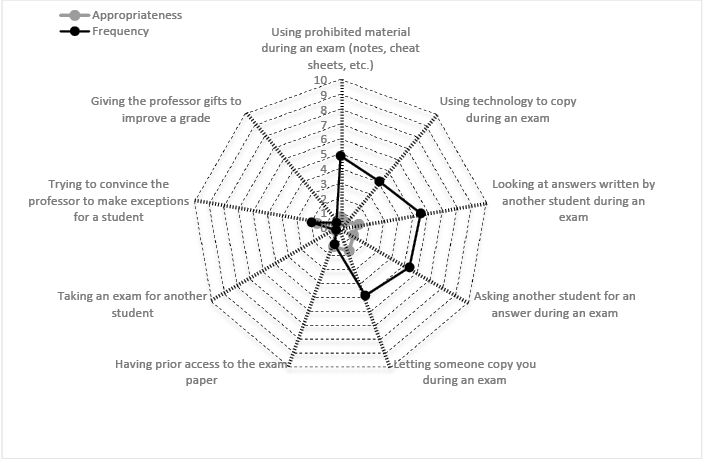

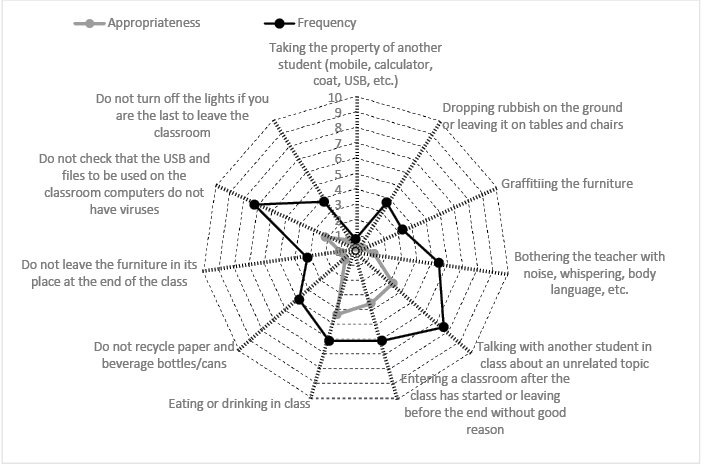

With the aim of identifying the types of conduct considered dishonest by students, a descriptive analysis was made based on the calculation of the average values obtained for each of the items in each of the blocks of conduct previously presented, and from each of the perspectives of the analysis: level of appropriateness of the conduct and frequency of occurrence observed. To facilitate the comparison between the two perspectives, the results are presented in spider graphs performed with the computer programme Excel.

Results

In light of the foregoing, the results obtained are shown in Figures I, II and III. As regards the first block (dishonest conduct in the preparation and presentation of assignments), the results show that students consider that all the types of conduct proposed in the study are inappropriate, albeit to different extents (average values from between 1.04 and 3.45). This recognition of the inappropriate nature of the conduct would lead us to expect that these forms of conduct were not observed in reality or that their frequency would be close to zero. However, this does not happen, observing frequencies between 1.12 and 5.97. For example, the lack of fair collaboration in preparing group work is considered the most inappropriate conduct but, in turn, is the most frequently observed conduct in class. A similar situation arises with such other forms of conduct as the preparation of deficient assignments to comply with the minimum requirements, the copying of bibliographic material without expressly quoting the source, and the inclusion in the authorship of people who have not worked on the assignment. The purchase/sale of assignments was the only item that stood out for its almost non-existence.

Figure II allows us to analyse the situation of dishonest conduct related to the evaluation tests. The data analysed leads us to conclude that a broad consensus exists among students on the forms of dishonest conduct. The majority of students recognise that this conduct is totally inappropriate for the new situations raised (average values of around one). The only forms of conduct that are observed with a certain frequency are those related to copying exams (with values of around half a point on the scale – five): looking at the answers of another student, asking another student questions in an exam, allowing someone to copy you and using unauthorised material, whether traditional resources or through technological means. Hence, these forms of conduct should be monitored.

FIGURE I. Inappropriate conduct in the preparation and presentation of assignments

NOTE: The black colour shows the average of appropriateness of the conduct and the grey colour the frecuency of occurrence observed.

FIGURE II. Inappropriate conduct in evaluation tests

NOTE: The black colour shows the average of appropriateness of the conduct and the grey colour the frecuency of occurrence observed.

Lastly, Figure III shows the analyses related to conduct within the framework of interpersonal relations and conduct related to daily aspects of respect and harmony. The results obtained also show in this case that students adequately differentiate between appropriate and inappropriate conduct, although they observe a certain graduality in such conduct. Accordingly, while taking property belonging to another student, throwing rubbish, painting furniture, being a nuisance in class by making a noise or murmuring are considered to be highly inappropriate (average values of between 0.24 and 1.32), the perception of the appropriateness of other conduct is more permissive (average values of between 3.21 and 4.31). These forms of conduct include eating or drinking in class, talking about matters unrelated to the class with another student, and going into or leaving the classroom once the lesson has begun without justification. Furthermore, these less appropriate forms of conduct are observed with greater frequency (average values between 6.09 and 7.57).

The differentiation between appropriate and inappropriate conduct becomes patently obvious when conduct primarily related to the environment is raised. The perception of students regarding the suitability of recycling, the orderly maintenance of classroom furniture, energy saving and checking for viruses on the USB before using shared devices is worthy of mention. However, and despite the consensus on the appropriateness of these issues, it can be observed that they are not undertaken with the frequency desired.

FIGURE III. Conduct within the framework of interpersonal relations and conduct related to daily aspects of respect and harmony.

NOTE: The black colour shows the average of apropriateness of the conduct and the grey colour the frecuency of occurrence observed.

The previous results underline that students suitably recognise and identify forms of dishonest conduct, and that, furthermore, they observe them habitually, to a greater or lesser extent, in the course of their learning activity. Hence, the need exists to propose new measures that discourage or prevent these forms of inappropriate conduct.

Table I contains the average values and the typical deviation of the discouragement and/or corrective measures analysed in the study. The results obtained show that student opinions are more geared towards the use of regulatory measures rather than training measures. Accordingly, they highlight actions designed to establish disciplinary and corrective measures to be addressed (with values of 7). Moreover, students not only consider their existence to be necessary, but that it is even more important to be made aware of them (7.81).

Training measures are also considered to be necessary by those surveyed, although to a lesser extent than regulatory measures, as shown by their average values. Accordingly, students consider an active role by lecturers to be necessary in informing them of fraudulent activities, particularly those related to exams, more so than classroom conduct. As regards how to convey this type of training measure, those surveyed express a preference for cross-cutting ethical training in the different subjects rather than specific courses on ethics.

The preference for regulatory rather than training measures was also observed in university students from other countries. Ramos et al., (2020) discovered that disciplinary measures were more highly valued by Portuguese students than such other measures as compulsory ethics courses, which were considered to be ineffective. Malgwi and Rakovski (2009) observed that students from a university in the United States opted for a disciplinary strategy.

TABLE I. Regulatory and training measures. Descriptive statistics

|

MEASURE |

Average |

Typical deviation |

|

|

REGULATORY |

Corrective measures for inappropriate conduct should be established |

7.00 |

2.73 |

|

Inappropriate conduct should be sanctioned |

7.11 |

2.89 |

|

|

Students should be informed of corrective measures and the sanctions for inappropriate conduct |

7.81 |

2.33 |

|

|

Centres should provide students with a code of ethics for the centre |

5.81 |

3.10 |

|

|

TRAINING |

Training should be provided on ethics via courses and/or seminars |

5.19 |

3.26 |

|

Ethical habits should be promoted in classroom subjects |

6.48 |

2.96 |

|

|

Faculty should explain the basic rules of classroom conduct |

5.56 |

3.19 |

|

|

Faculty should clearly outline actions permitted in exams |

6.45 |

3.34 |

|

Discussion and conclusions

Higher education institutions seek to ensure academic honesty and for this to be a key value for all their members, particularly for those receiving training – their students. Regrettably, there is evidence that clearly shows that dishonest student conduct is more prevalent than could be hoped for. Furthermore, the practice of this type of conduct exceeds the purely academic ambit and can even impact the ethics of the future personal, professional and civic life of these students.

The results of the work have led us to identify student perceptions on the level of appropriateness and inappropriateness of certain types of conduct, along with the frequency of said conduct observed among other students.

In general, the results lead us to assert that students clearly identify inappropriate (dishonest) conduct and differentiate it correctly from appropriate conduct. They specifically consider those types of conduct that could be considered “illegal” as inappropriate, but are somewhat more permissive regarding other related conduct, mainly in relation to the environment, for example, recycling and energy saving.

As regards the frequency of these types of conduct observed, we should highlight that none of them were observed habitually or constantly among students, although some of them observed them more often than was to be hoped for and desirable. Specifically, among types of conduct related to the preparation of assignments, those observed more frequently (albeit in the middle range) are a lack of fair collaboration, the inclusion of authors who did not participate, the manipulation of sources of information, errors in the form and/or lack of quoting the source, the preparation of deficient assignments and the copying of assignments. The types of conduct related to exams observed the most frequently (again in the middle range) include some considered to be unlawful, such as the traditional copying in exams, specifically looking at other students’ work or asking other students for the answer, allowing themselves to be copied and copying out notes – “crib sheets” – or by using electronic means. Furthermore, when looking at the types of conduct considered by a panel of Spanish experts to be the most serious, which include pretending to be another person in an evaluation, stealing exams or tests and obtaining the exam questions before taking the exam (Sureda-Negre et al., 2020), it can be seen that these were observed in our paper with a low level of frequency, and are even practically non-existent.

The types of conduct related to the rules of coexistence in classrooms are those that are broken most frequently, mainly those aimed at being a nuisance to both lecturers and students during the course of the class (talking in class, making a noise, interrupting the class by coming in and going out, etc.). Furthermore, it is surprising that some types of conduct to foster environmental sustainability are not observed with the frequency desired, particularly those related to recycling and energy saving, when there is a clear commitment at this time to greater sustainability (2030 Horizon – Sustainable Development Goals – SDG).

These results confirm the need for universities to address the introduction of measures that enable the dishonest conduct detected to be corrected. What’s more, evidence exists that shows that the existence of academic rules can become a preventive factor of student dishonesty (Jordan, 2001). Being aware of what types of measures are more highly rated by students is important, because it fosters their introduction, and hence their effectiveness.

The results obtained show that university students prefer regulatory measures, in other words, regulatory provisions that indicate the types of dishonest conduct, their consequences and the applicable sanctions if they incur in them. This result is in line with other previous research applied in universities in other countries (Malgwi & Rakovski, 2009; Ramos et al., 2020).

Given that, as indicated by Sureda et al., (2016), the establishment of codes of conduct or academic regulations that address the matter of academic integrity are more effective when drawn up through consensus among all the members of the institution, the results of this work are useful for a greater insight into the student’s perspective.

However, although a preference exists for regulatory measures, training measures are also considered necessary by students. In this regard, according to Foltynek (2013), Spain is one of the European countries where university students receive less training on academic integrity, and hence requires more support and training on the matter (Cebrián-Robles et al., 2018). Despite the fact that the verification reports on the degrees analysed contain, among their skills, some aimed at promoting the ethical conduct of students, the results of the research would seem to show that the acquisition of certain skills could be improved and that, furthermore, these should be adapted to the knowledge and information society we find ourselves in at this time. Although ICT have democratised the access to information and knowledge, they have also fostered the emergence of new forms and tools that facilitate the performance of dishonest conduct (Cebrián-Robles et al., 2020), particularly plagiarism. However, ICT can also serve as the basis to create and use tools that allow more preventative and training strategies designed for students to be adopted. For example, training actions could be designed that focus on specific areas such as training in the use of bibliographic management software, like the open platform Zotera, among others.

This paper presents certain limitations that could be addressed in future research papers. While the sample focuses on a specific faculty (Economic and Business) of a Spanish university, this could be extended to other undergraduate and post-graduate studies. The procedure followed for the selection of the sample is not based on probability, in other words, it is a convenience sample. The questionnaire has been designed to see the perception of students, but it would also be useful to see the perception of faculty and university management, with the aim of identifying whether the same evidence is observed in the same way. Despite these limitations, it is considered that new evidence is offered and results provided that could prove useful to the university community. In the short term, it serves to establish the rules corresponding to universities as transposed by the recently approved University Coexistence Act. In the medium and long term, it serves to guide and improve subjects (in both content and methodology) with a view to training and instilling more ethical and appropriate conduct in students, focusing on training to eradicate those more commonly observed types of inappropriate conduct. Training in digital skills and respect for copyright and user licences will be key in the new digital society. The future Constitutional Law on the University System (LOSU) could be turned into an opportunity for this. Furthermore, the fact that the Internet is a key resource used by students in the search for information and resources makes it necessary to strive to foster a more critical spirit in students and focus studies on the use of this resource in a constructive and suitable manner.

References

Adam, L., Anderson, V., & Spronken-Smith, R. (2017). “It`s not fair”: policy dicourses and student’s understandings of plagiarism in a New Zealand university. Higher Education, 74, 17-32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0025-9

Alleyne, P., & Phillips, K. (2011). Exploring Academic Dishonesty among University Students in Barbados: An Extension to the Theory of Planned Behaviour, Journal of Academic Ethics, 9, 323-338 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-011-9144-1

Almeida, F., Seixas, A. M., Gama, P., Peixoto, P., & Esteves, D. (2016). Fraude e Plágio na Universidade. A Urgência de Uma Cultura de Integridade no Ensino Superior; Coimbra University Press. Coimbra, Portugal,

American-Association-of-School-Librarians (2009). Standards for the 21st-century learner in action. American Library Association.

Blankenship, K. L., &. Whitley, B. E. Jr (2000). Relation of general deviance to academic dishonesty, Ethics & Behavior, 10(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327019EB1001_1

Burke, D. D., & Sanney, K. J. (2018). Applying the Fraud Triangle to Higher Education: Ethical Implications. Journal of Legal Studies Education, 35, 5-43. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlse.12068

Cebrián-Robles, V., Raposo-Rivas, M., Cebrián-de-la-Serna, M., & Sarmiento-Campos, J. A. (2018). Percepción sobre el plagio académico de estudiantes universitarios españoles. Educación XX1, 21(2), 105–129. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.20062

Cebrián-Robles, V., Raposo-Rivas, M., & Ruiz-Rey, F. (2020). Conocimiento de los estudiantes universitarios sobre herramientas antiplagio y medidas preventivas. Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación, 57, 129-149. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.2020.i57.05

Cerdá-Navarro, A., Touza, C., Morey-López, M., & Curiel, E. (2021). Academic Integrity Policies Against Assessment Fraud in Postgraduate Studies: An Analysis of the Situation in Spanish Universities. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3966219 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3966219

Chapman, D. W., & Lindner, S. (2016). Degrees of integrity: the threat of corruption in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 41(2), 247-268. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.927854

Comas, R. (2009). El ciberplagio y otras formas de deshonestidad académica entre el alumnado universitario [tesis doctoral no publicada]. España: Universidad de las Islas Baleares.

Comas, R., & Sureda, J. (2016). Prevalencia y capacidad de reconocimiento del plagio académico entre el alumnado del área de economía. El profesional de la información (EPI), 25(4), 616-622. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2016.jul.11

Comas, R., Sureda, J., Casero, A., & Morey, M. (2011). La integridad académica entre el alumnado universitario español. Estudios Pedagógicos, 37(1), 207-225. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-07052011000100011

Eckstein, M. A. (2003). Combating Academic Fraud. Towards a Culture of Integrity. Paris: Unesco – International Institute for Educational Planning.

Epstein, R. (2010). Academic Fraud Today: Its Social Causes and Institutional Responses. 21 Stanford Law and Policy Review, 135–154.

Ercegovac, Z., & Richardson, J. V. (2004). Academic dishonesty, plagiarism included, in the digital age: A literature review. College & Research Libraries, 65(4), 300–318. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.65.4.301

Espiñeira-Bellón, E. M., Mosteiro-García, M. J., Muñoz-Cantero, J. M., & Porto-Castro, A. M. (2020). La honestidad académica como criterio de evaluación de los trabajos del alumnado universitario. RELIEVE, 26(1), art. 2. http://doi.org/10.7203/relieve.26.1.17097

Estow, S., Lawrence, E. K., & Adams, K. A. (2011). Practice makes perfect: Improving students’ skills in understanding and avoiding plagiarism with a themed methods course. Teaching of psychology, 38(4), 255-258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628311421323

Foltynek, T. (2013). Impact of Policies for Plagiarism in Higher Education Across Europe. Plagiarism Policies in Spain. Retrieved from http://plagiarism.cz/ippheae/files/D2-3- 09%20ES%20IPPHEAE%20MENDELU%20Survey%20SpainNarrative%20FI NAL.pdf

Guerrero-Dib, J.G., Portales, L., & Heredia-Escorza, Y. (2020). Impact of academic integrity on workplace ethical behaviour. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 16(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-020-0051-3

Hernández, R., Fernández, C., & Baptista, P. (2014). Metodología de la investigación. México: McGrawHill.

Jordan, A. E. (2001). College Student Cheating: The Role of Motivation, Perceived Norms, Attitudes, and Knowledge of Institutional Policy. Ethics & Behavior, 11(3), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327019eb1103_3

Kibler, W. L. (1993). Academic Dishonesty. NASPA Journal, 30(4), 252-267, DOI:10.1080/00220973.1993.11072323

Ley 3/2022, de 24 de febrero, de Convivencia Universitaria en España (BOE núm. 48, de 25 de febrero de 2022)

López, S., & Fernández, M. C. (2019). Social representations about plagiarism in academic writing among university students. Íkala, 24(1), 119-134. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v24n01a06

LoSchiavo, F. M., & Shatz, M. A. (2011). The impact of an honor code on cheating in online courses. Journal of Online Learning & Teaching, 7(2).

Malesky, A. L. Jr., J Baley, John W., & Crow, R. (2016). Academic Dishonesty: Assessing the Threat of Cheating Companies to Online Education. College Teaching, 64(4), 178-183. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2015.1133558

Malgwi, C. A., & Rakovski, C.C. (2009). Combating Academic Fraud: Are Students Reticent about Uncovering the Covert?. Journal of Academy Ethics, 7(3), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-009-9081-4

Marques, T. M. G., Reis, N., & Gomes, J. (2019). A Bibliometric Study on Academic Dishonesty Research, Journal of Academy Ethics, 17(4), 169–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-019-09328-2

Marsh, J. D., & Campion, J. (2018). Academic integrity and referencing: whose responsibility is it? Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 12(1), A213–A226. https://journal.aall.org.au/index.php/jall/article/view/546

Marzal, M. Á., & Calzada, J. (2003). Un análisis de necesidades y hábitos informativos de estudiantes universitarios en Internet. Binaria: Revista de Comunicación, Cultura y Tecnología, 3. http://hdl.handle.net/10016/4632.

Morris, E. (2010). Supporting academic integrity. Approaches and resources for higher education. Academic Service.

Muñoz-Cantero, J. M., Rebollo-Quintela, N., & Mosteiro-García, Ma. J. (2019). Validación del cuestionario de atribuciones para la detección de coincidencias en trabajos académicos. Relieve: Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa, 25(1). https://doi.org/10.7203/relieve.25.1.13599

Orosz, G., Dombi, E., Tóth-Király, I., Bőthe, B., Jagodics, B., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2016). Academic cheating and time perspective: cheaters live in the present instead of the future. Learning and Individual Differences, 52, 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.10.007

Porto-Castro, A. M., Espiñeira-Bellón, E. M., Losada-Puente, L., & Gerpe-Pérez, E. M. (2019). El alumnado universitario ante políticas institucionales y de aula sobre plagio. Bordón, 71(2), 139-153. https://doi.org/10.13042/Bordon.2019.69104

Ramos, R., Gonçalves, J., & Gonçalves, S. P. (2020). The Unbearable Lightness of Academic Fraud: Portuguese Higher Education Students’ Perceptions. Education Sciences, 10(12), 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10120351

Reyneke, Y., Shuttleworth C. C., & Visagie, R. G. (2021). Pivot to online in a post-COVID-19 world: critically applying BSCS 5E to enhance plagiarism awareness of accounting students, Accounting Education, 30(1), 1-21, https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2020.1867875

Sánchez-Santamaría, J. (2011). Evaluación de los aprendizajes universitarios: una comparación sobre sus posibilidades y limitaciones en el Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior, Revista de Formación e Innovación Educativa Universitaria, 4(1), 40-54.

Sarmiento-Campos, J. A., Ocampo-Gómez, C. I., & Castro-Pais, M. D. (2022). Estudio del plagio académico mediante escalamiento multidimensional y análisis de redes. Revista de Educación, 397, 293-321. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2022-397-548

Sithole, A., Mupinga, D. M., Kibirige, J. S., Manyanga, F., & Bucklein, B. K. (2019). “Expectations, Challenges and Suggestions for Faculty Teaching Online Courses in Higher Education”. International Journal of Online Pedagogy & Course Design; 8(1), 62-77, https://doi.org/10.4018/IJOPCD.201901010

Sureda-Negre, J., Cerdá-Navarro, A., Calvo-Sastre, A., & Comas-Forgas, R. (2020). Las conductas fraudulentas del alumnado universitario español en las evaluaciones: valoración de su gravedad y propuestas de sanciones a partir de un panel de expertos. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 38(1), 201-219. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.358781

Sureda-Negre, J., Reynes-Vives, J., & Comas-Forgas, R. (2016). Reglamentación contra el fraude académico en las universidades españolas. Revista de la Educación Superior, 45(178), 31-44.

Tatum, H., & Schwartz, B. M. (2017). Honor Codes: Evidence Based Strategies for Improving Academic Integrity. Theory Into Practice, 56(2), 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2017.1308175

Teixeira, A. C., & Rocha, M. A. (2010). Cheating by economics and business undergraduate students: an exploratory international assessment. Higher Education, (59), 663-701. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9274-1

Vlasenko A., & Shirokanova A. (2022). The Role of Values in Academic Cheating at University Online. In: Alexandrov D.A. et al. (Eds.) Digital Transformation and Global Society. DTGS 2021. Communications in Computer and Information Science, 1503. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93715-7_21

Von Dran, G. M., Callahan, E. S., & Taylor, H. V. (2001). Can students’ academic integrity be improved? Attitudes and behaviours before and after implementation of an academic integrity policy, Teaching Business Ethics, 5, 35–58. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026551002367

Young, J. R. (2012). Online Classes See Cheating Go High-Tech, The Chronicle of Higher Education., http://www.chronicle.com/article/cheating-goes-high-tech/132093.

Zúñiga, L., Toscano, B., & Ponce, J. (2015). El desarrollo del comportamiento ético en estudiantes de un programa académico de pregrado en el contexto del modelo educativo Basado en Competencias. Revista Sociología Contemporánea, 2 (5), 203-214.

Contact address: Mercedes Marzo Navarro. Universidad de Zaragoza, Facultad de Economía y Empresa. C/ Gran Vía, 2, postal code 50005, Zaragoza (Spain). E-mail: mmarzo@unizar.es

1 The authors are grateful for the financial support provided by the Innovation Project from the University of Zaragoza (PIIDUZ_19_2_278), the CREVALOR (S42_20R) and COMPETE (S52_20R) research groups of the Government of Aragon (SPAIN) and FEDER (2014-2020 “Construyendo Europa desde Aragón”).

2 These academics belong to such fields as the organisation of companies, the commercialisation and research of markets, and finance and accounting. One researcher among these stands out for her high-quality research acknowledged in the field of higher education, although all of them have extensive experience in this regard.